The Etching of Al-Doped Co3O4 with NaOH to Enhance Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

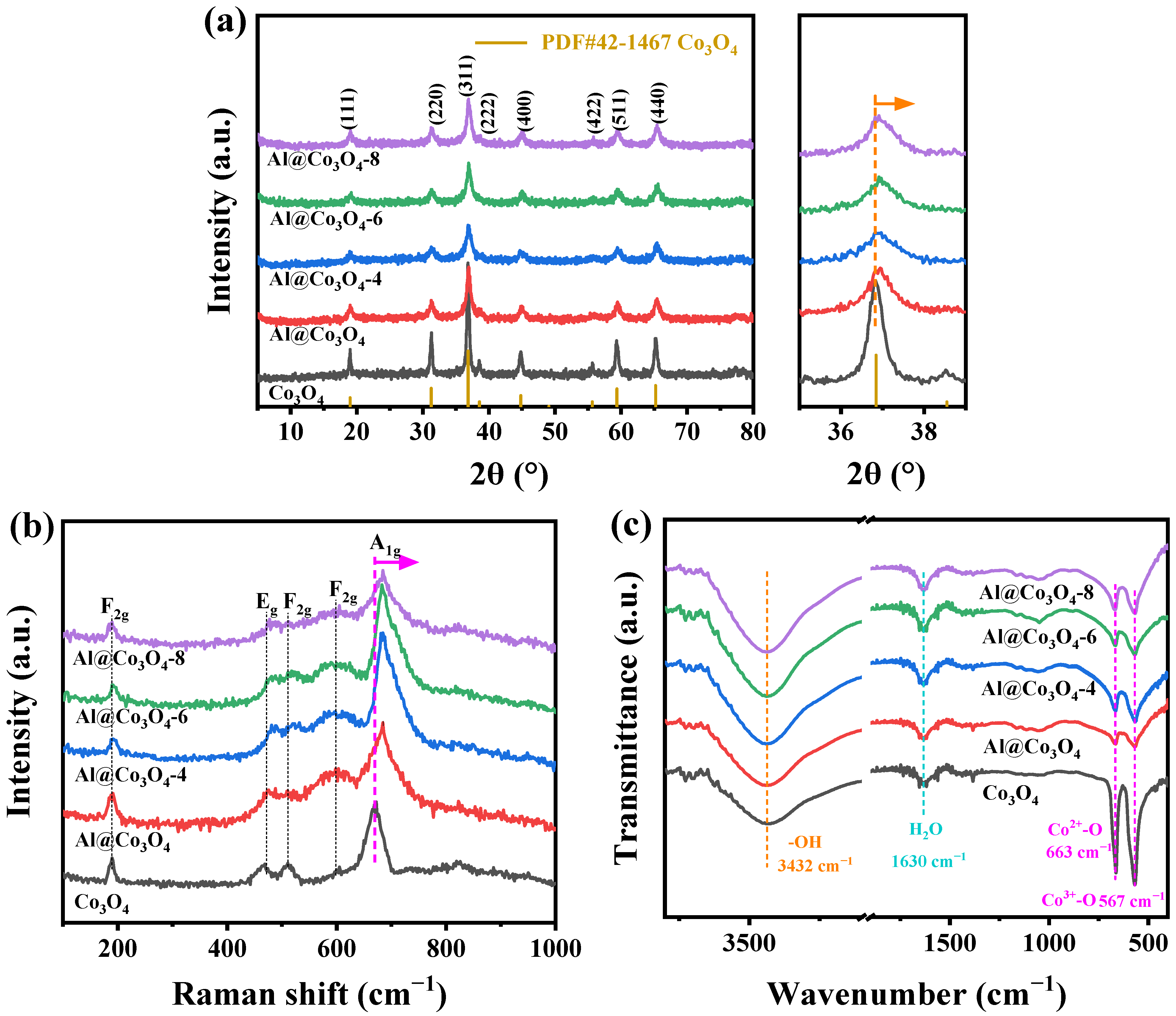

2.1. Characterization of Physical Structure

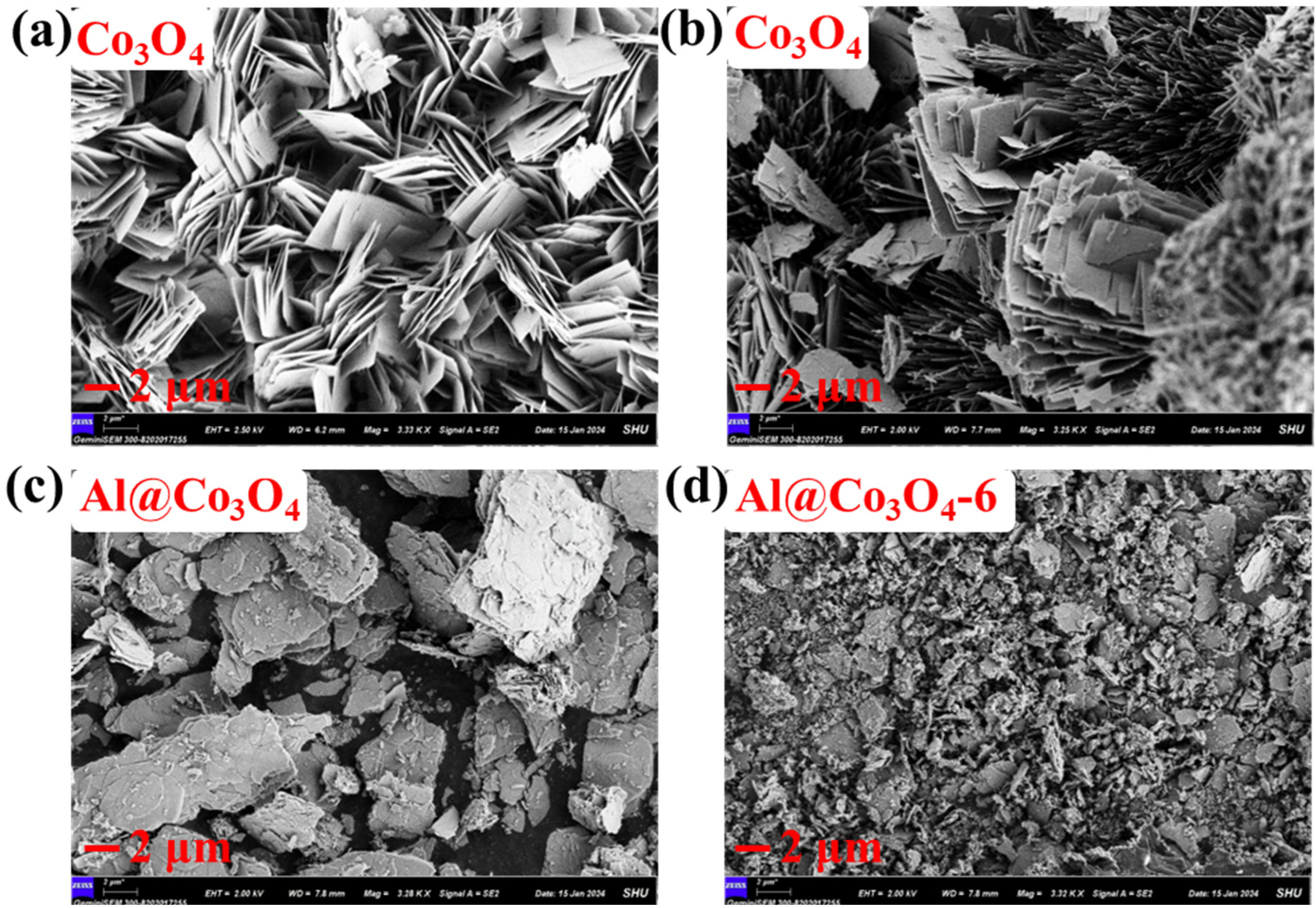

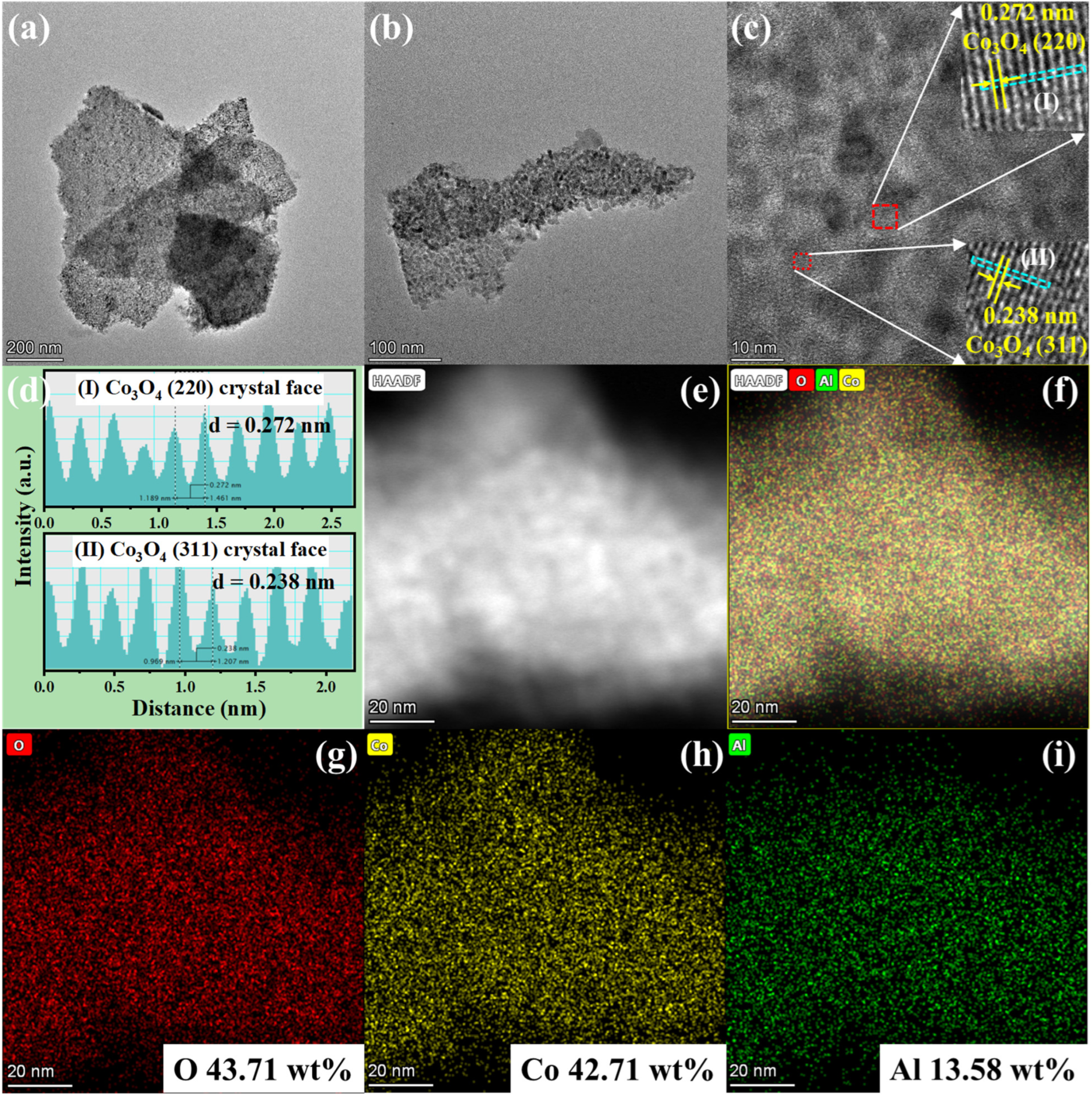

2.2. Morphology and Texture Structure

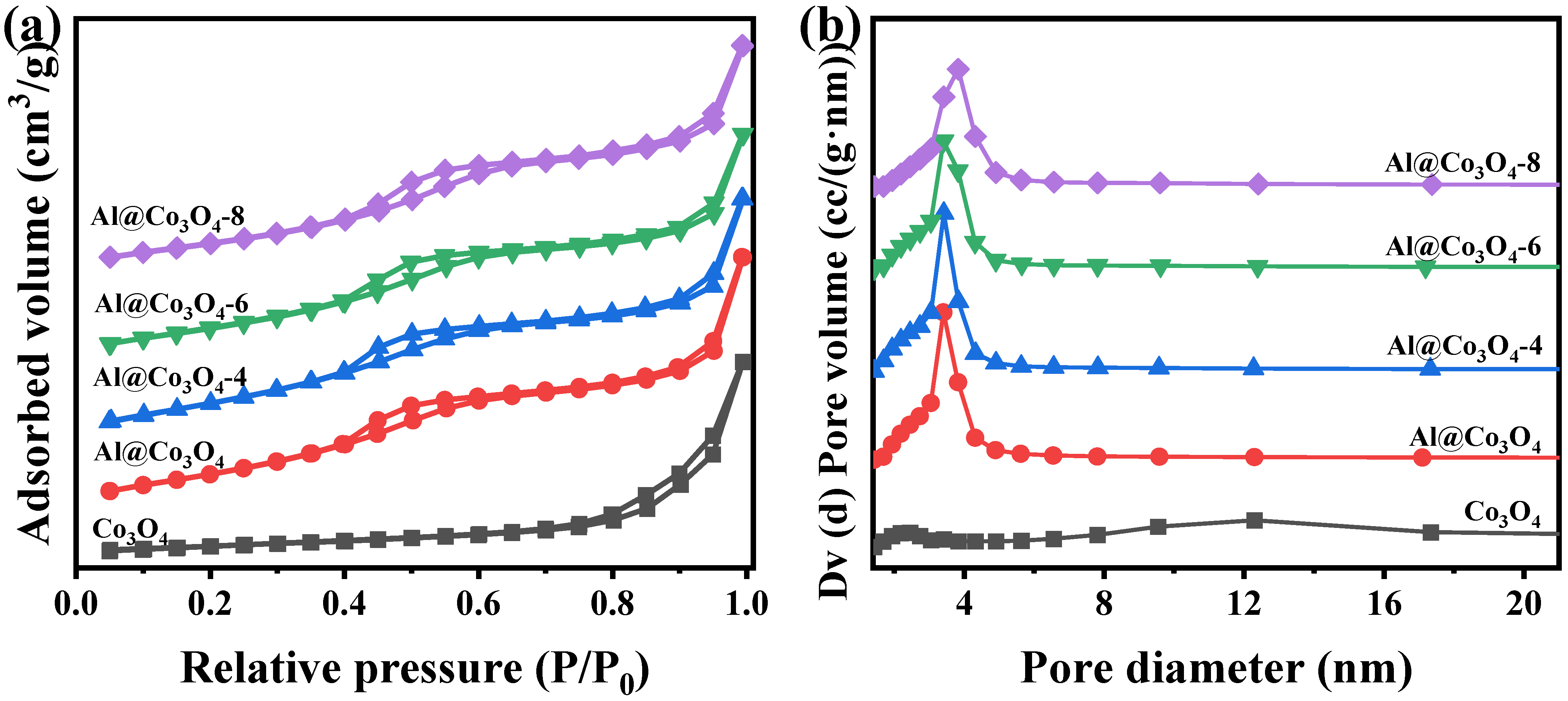

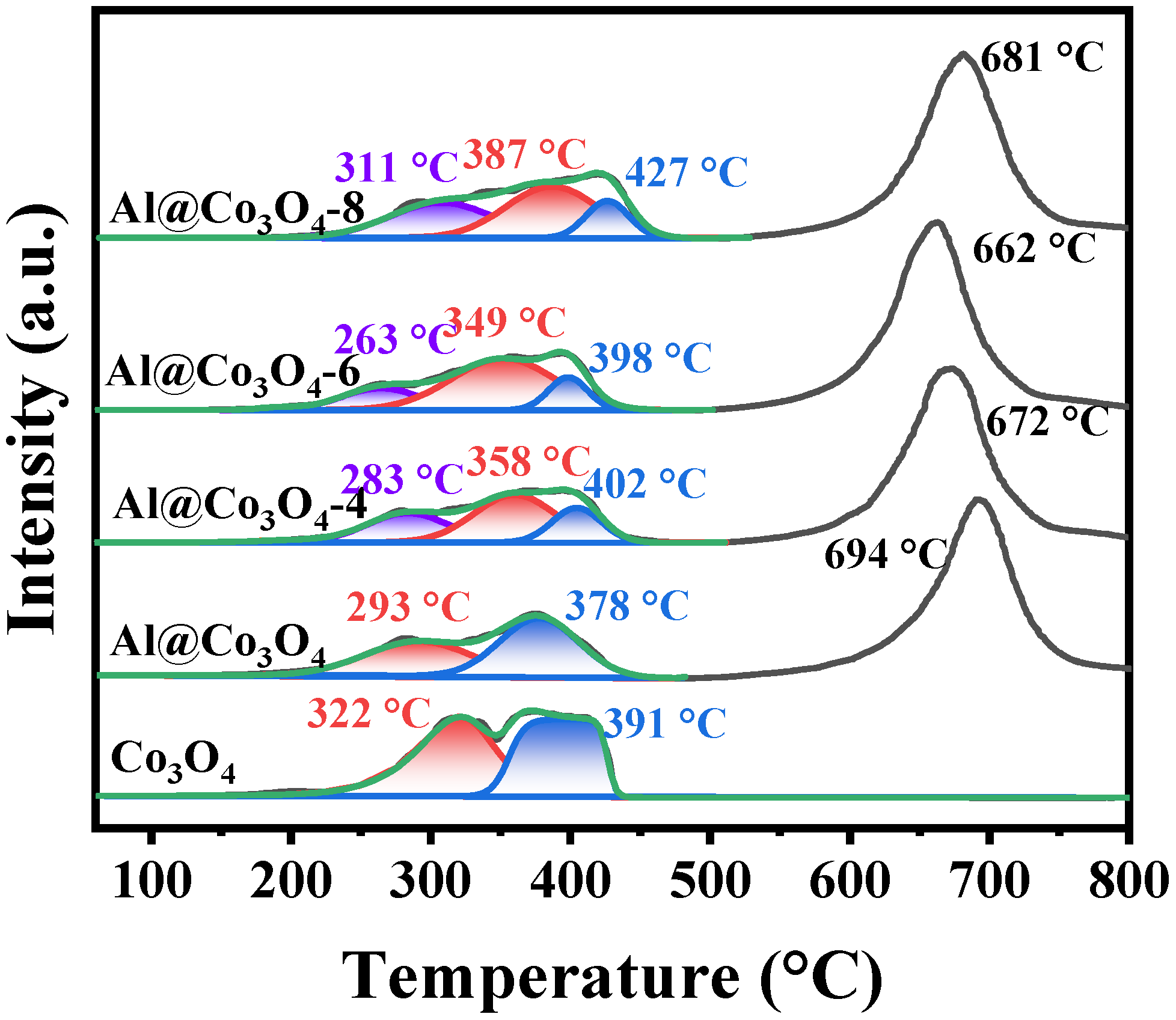

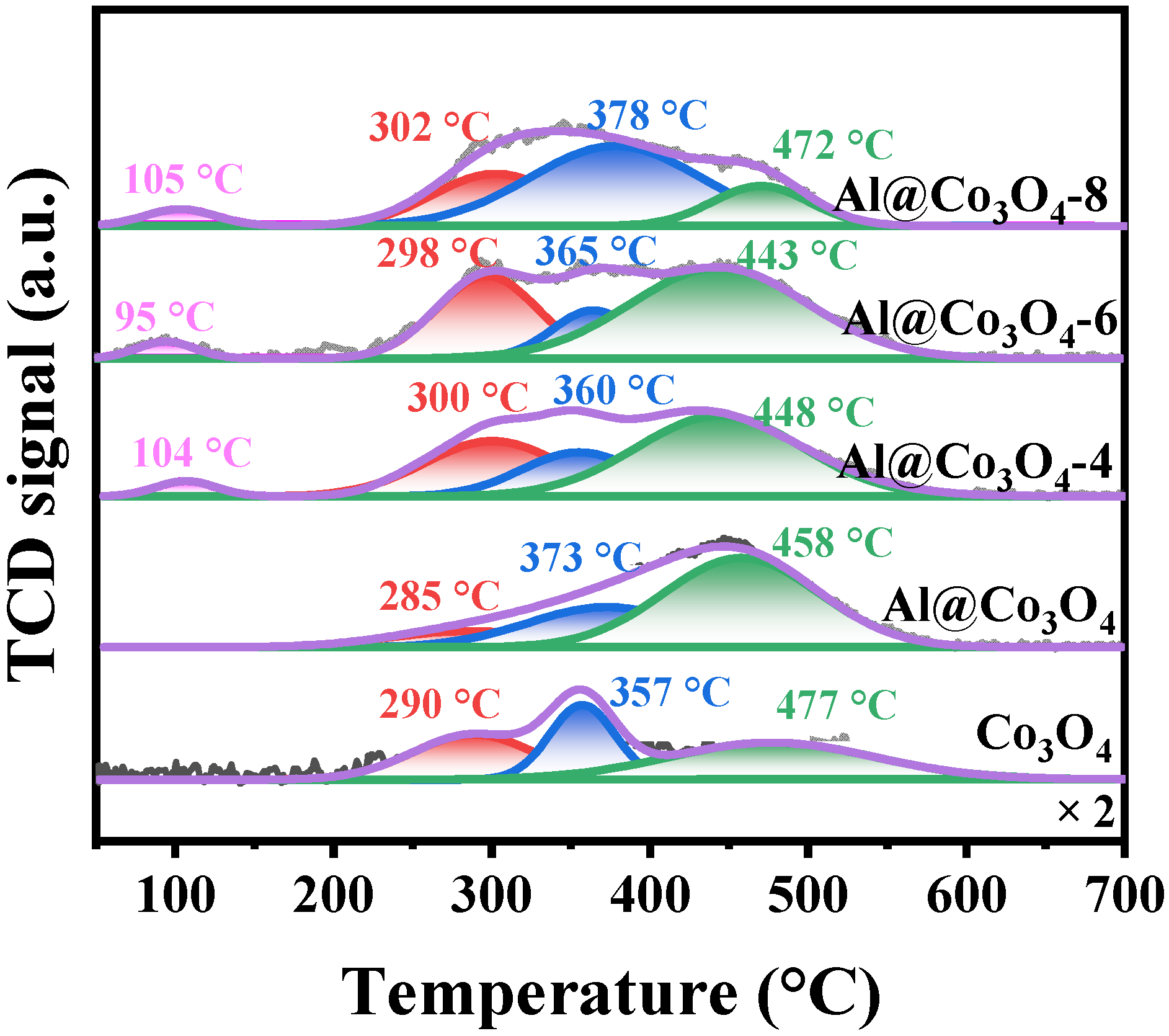

2.3. Pore Structure and Chemical Properties

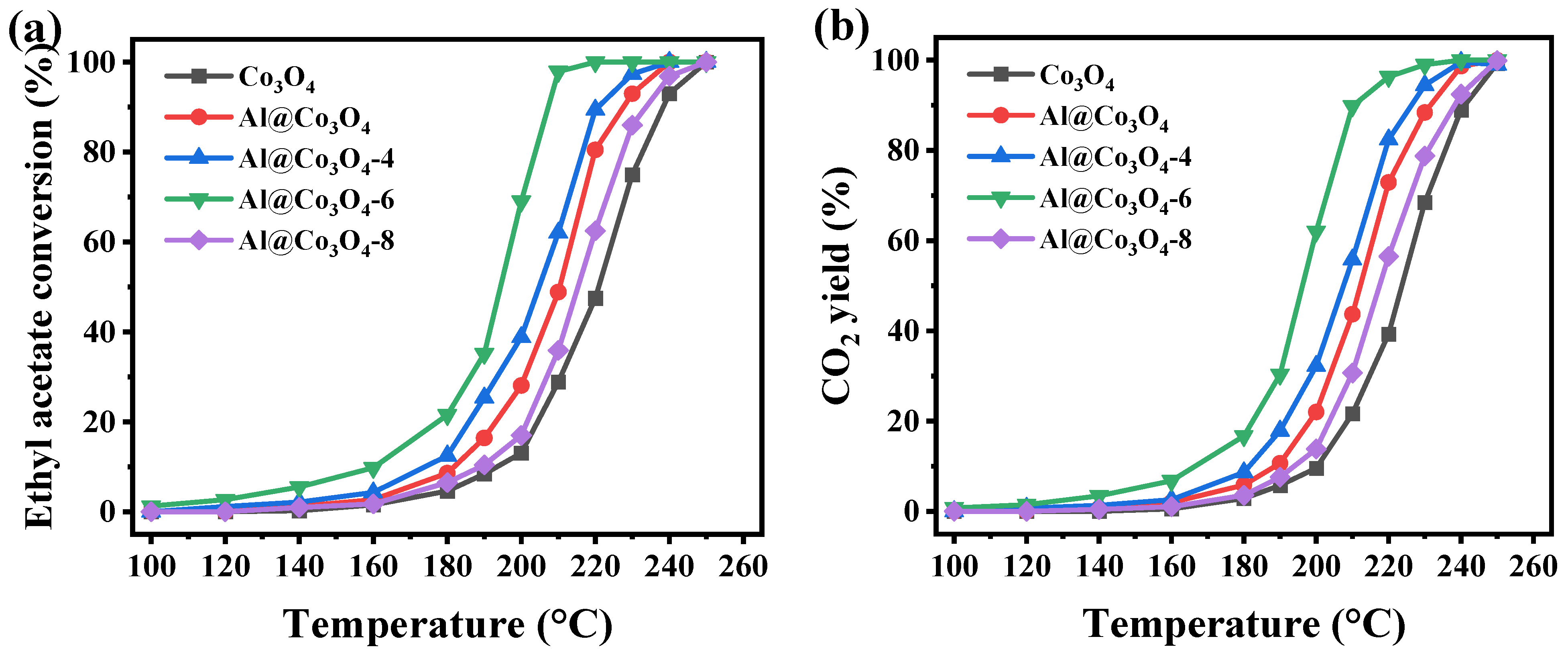

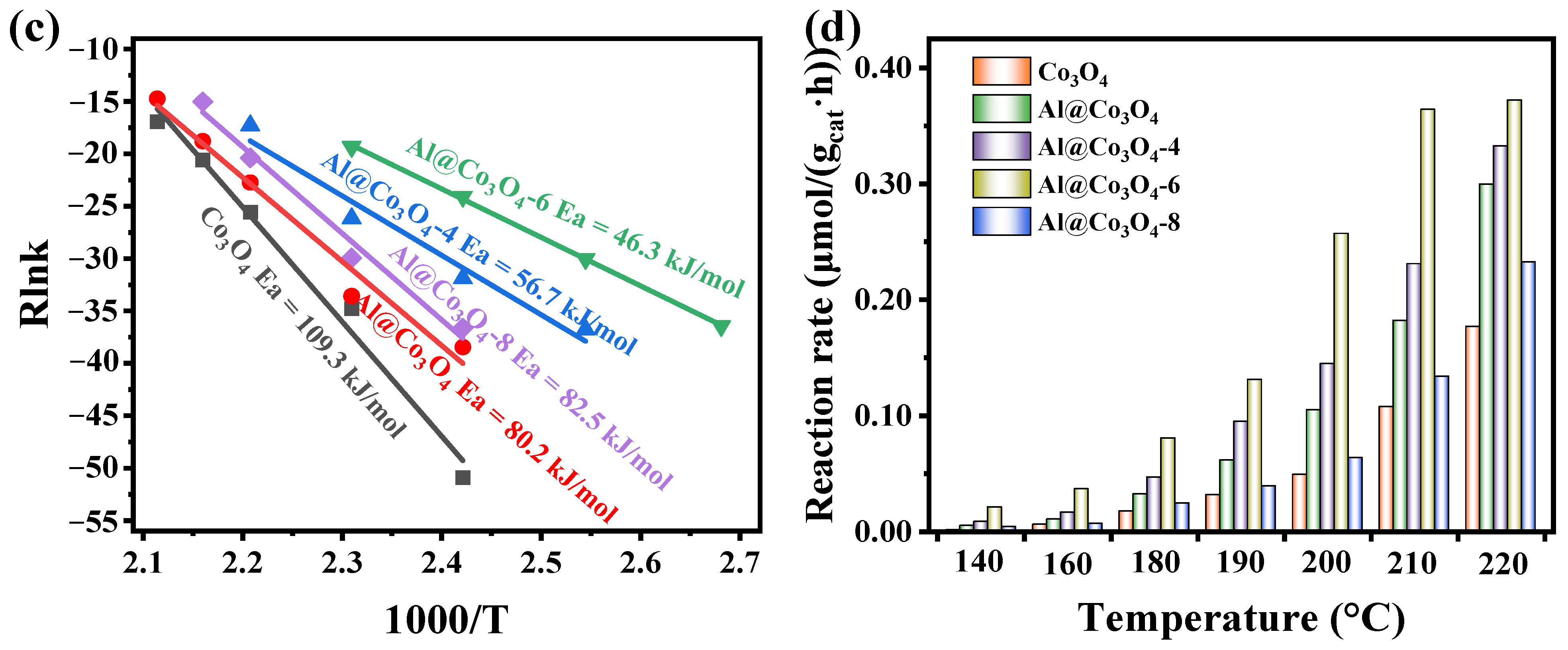

2.4. Catalytic Performance

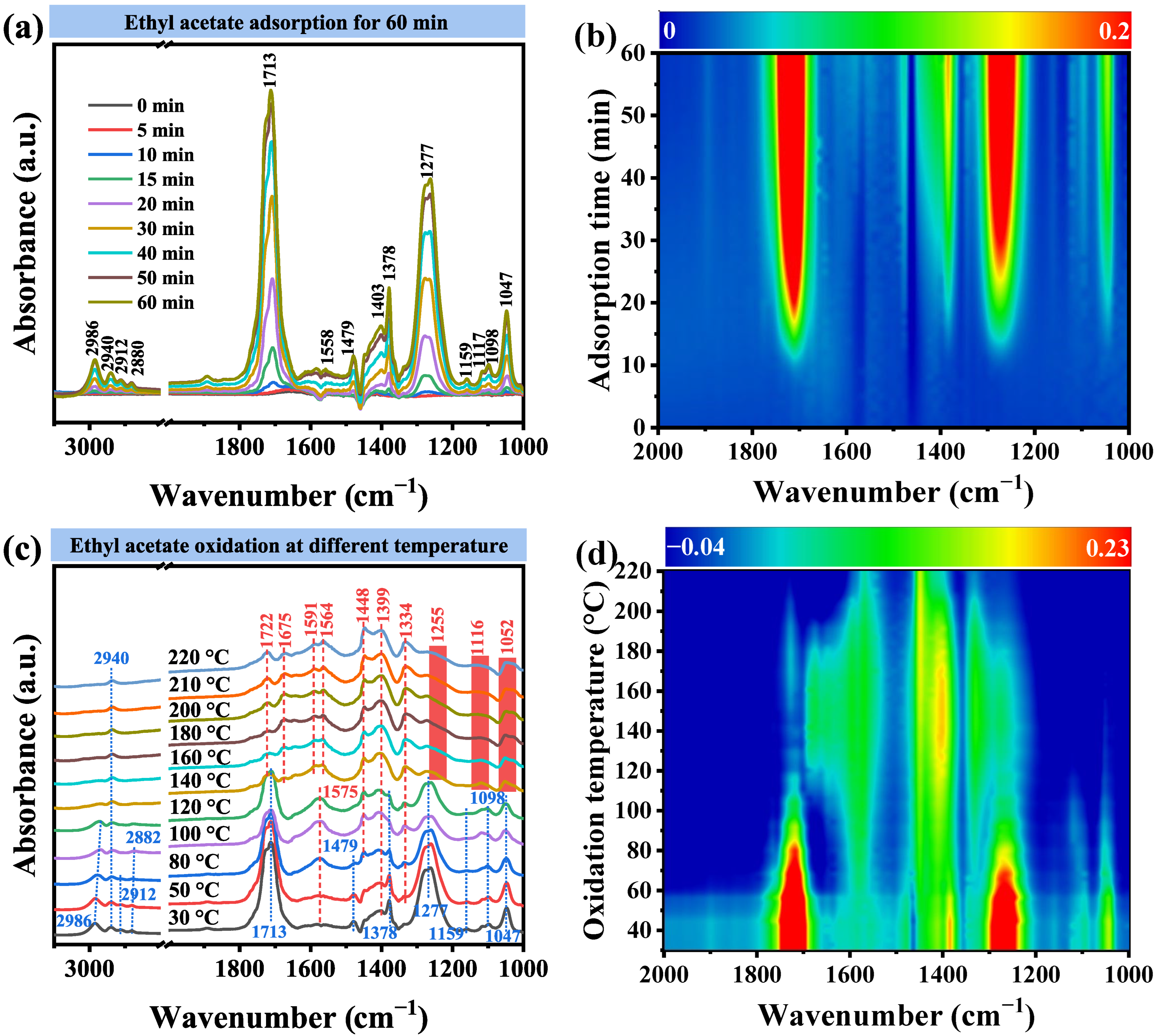

2.5. Catalytic Mechanism and Ethyl Acetate Degradation Pathway

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Chemistry

3.2. Catalysts Synthesis

3.2.1. Preparation of Co3O4

3.2.2. Synthesis of Al-Doped Co3O4 (Al@Co3O4)

3.2.3. Synthesis of NaOH-Etched Al@Co3O4

3.3. Catalysts Characterization

3.4. Catalytic Performance Test

3.5. Athyl Acetate Degradation Intermediates Detection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, G. Revealing the nonlinear responses of PM2.5 and O3 to VOC and NOx emissions from various sources in Shandong, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.K.; Feng, X.B.; Huang, J.H.; Wei, J.F.; Wang, H.M.; Du, Q.X.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.C.; Liu, B.L.; Huang, Y.D.; et al. Unveiling the Influence Mechanism of Impurity Gases on Cl-Containing Byproducts Formation during VOC Catalytic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15526–15537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.J.; Li, S.; Hu, H.Y.; Gao, L.X.; Huang, Y.D.; Pu, F.G.; Yao, H. Enhanced VOCs adsorption mechanism on biochar synthesized by one-step molten salt thermal treatment: Experimental and DFT insights. J. Environ. Manag. 2026, 397, 128310. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.W.; Liu, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Yao, Z.T. Unveiling adsorption mechanism of low-concentration VOCs on waste circuit board-derived porous carbon: A combined experimental and molecular simulation study. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 385, 136447. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.H.; Wei, J.F.; Tian, F.Y.; Bi, F.K.; Rao, R.Z.; Wang, Y.X.; Tao, H.C.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.D. Nitrogen-induced TiO2 electric field polarization for efficient photodegradation of high-concentration ethyl acetate: Mechanisms and reaction pathways. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 41, 102292. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Chu, P.Q.; Hou, Z.Q.; Wu, L.K.; Liu, Y.X.; Deng, J.G.; Dai, H.X. Single-atom catalysts in the photothermal catalysis: Fundamentals, mechanisms, and applications in VOCs oxidation. Chem. Syth. 2025, 5, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Guo, M.Z.; Lu, Z.H.; Bi, F.K.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.D. Study on the difference in catalytic performance and chlorine-resistance of Universitetet i Oslo-derived M@ZrO2 (M = Pd, Pt) catalysts for o-Xylene degradation. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 49, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, J.N.; Buren, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.J.; Ma, S.T.; Wei, J.F.; Bi, F.K.; Zhang, X.D. Electron beam irradiation defective UiO-66 supported noble metal catalysts for binary VOCs removal: Insight into the synergistic degradation mechanism of mutual promotion. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 380, 135236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Y.; Li, Y.T.; Tang, Z.Y.; Yuan, D.K.; Lin, F.W. Strong Metal–Support Interactions in Catalytic Oxidation of VOCs: Mechanistic Insights, Support Engineering Strategies, and Emerging Catalyst Design Paradigms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 19644–19666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Hu, H.T.; Wei, J.F.; Qiao, R.; Bi, F.K.; Zhang, X.D. Recent progress of cerium-based catalysts for the catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds: A review. Fuel 2025, 399, 135603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.H.; Wu, S.P.; Yuan, C.Y.; Huang, Z.; Shen, W.; Xu, H.L. Development of Highly Active and Stable SmMnO3 Perovskite Catalysts for Catalytic Combustion. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Xiao, J.; Li, N.J.; Xu, Q.F.; Li, H.; Chen, D.Y.; Lu, J.M. Surface engineering of ternary mixed transition metal oxides for highly efficient catalytic oxidation of low concentration VOCs. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 334, 126000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Bai, B.Y.; Zhu, X.F.; Guo, J.J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.J.; Peng, Y.; Si, W.Z.; Ji, S.F.; Li, J.H. Insights into effects of grain boundary engineering in composite metal oxide catalysts for improving catalytic performance. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 653, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.L.; Zhao, T.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Zhu, B.; Yu, T.G.; Liu, W.T.; Zhao, M.Q.; Cui, B. Co3O4-Based Catalysts for the Low-Temperature Catalytic Oxidation of VOCs. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Fang, W.J.; Yao, X.; Zou, G.C.; Shangguan, W.F. Low-temperature catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde over Co3O4 catalysts prepared using various precipitants. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.M.; Feng, Z.T.; Mo, S.P.; Huang, C.L.; Li, S.J.; Zhang, W.X.; Chen, L.M.; Fu, M.L.; Wu, J.L.; Ye, D.Q. 1D-Co3O4, 2D-Co3O4, 3D-Co3O4 for catalytic oxidation of toluene. Catal. Today 2019, 332, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Bai, B.Y.; Zhou, B.; Ji, S.F. Co3O4 nanoparticles with different morphologies for catalytic removal of ethyl acetate. Catal. Commun. 2021, 156, 106320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Xiao, M.; You, J.K.; Liu, G.; Wang, L.Z. Defect Engineering in Photocatalysts and Photoelectrodes: From Small to Big. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.L.; Hu, Z.Y.; Jia, H.P.; Chen, J.; Lu, C.Z. Constructing CuO/Co3O4 Catalysts with Abundant Oxygen Vacancies to Achieve the Efficient Catalytic Oxidation of Ethyl Acetate. Catalysts 2025, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.Y. Tuning ozone decomposition intermediates on δ-MnO2 to improve its moisture-resistance in ozone catalytic oxidation of toluene. Appl. Catal. B 2025, 378, 125526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Seo, C.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Sun, K.; Schwank, J.W. Indium-doped Co3O4 nanorods for catalytic oxidation of CO and C3H6 towards diesel exhaust. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 222, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.K.; Wei, J.F.; Zhuo, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.F.; Gao, B.; Liu, N.; Xu, J.C.; Liu, B.L.; Huang, Y.D.; Zhang, X.D. Insight into the Synergistic Effect of Binary Nonmetallic Codoped Co3O4 Catalysts for Efficient Ethyl Acetate Degradation under Humid Conditions. JACS Au 2025, 5, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cu, M.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.G.; Ma, Y.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.B.; Zhu, L.; Qiao, S.; Wei, J.P.; et al. Unveiling the mechanism of alkali etched CuMn2O4-δ spinel catalysis enhance for acetone catalytic Oxidation: The roles of Metal-Oxygen bond and oxygen defect site. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 345, 127339. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, J.G.; Wang, W.X.; Xie, L.L.; Li, X.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhu, Z.G. MOF-derived Al3+-doped Co3O4 nanocomposites for highly n-butanol gas sensing performance at low operating temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 978, 173341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.H.; Sun, S.Q.; Xie, D.H.; Dai, S.T.; Shao, W.; Zhang, Q.D.; Qin, C.L.; Liang, G.M.; Li, X.Y. Engineering defective Co3O4 containing both metal doping and vacancy in octahedral cobalt site as high performance catalyst for methane oxidation. Mol. Catal. 2024, 553, 113768. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, J.; Awan, M.Q.; Mazhar, M.E.; Ashiq, M.N. Effect of substitution of Co2+ ions on the structural and electrical properties of nanosized magnesium aluminate. Phys. B 2011, 406, 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.L.; Zou, M.L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.G.; Wang, X.S.; Yang, L.X.; Zhou, L.; Zou, J.P.; Luo, X.B.; et al. Monoatomic oxygen fueled by oxygen vacancies governs the photothermocatalytic deep oxidation of toluene on Na-doped Co3O4. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 317, 121769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, J.; Puthirath, A.B.; Sahoo, M.R.; Nayak, S.K.; Costin, G.; Vajtai, R.; Sharifi, T.; Ajayan, P.M. Tuning the Electrocatalytic Activity of Co3O4 through Discrete Elemental Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 39706–39714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.W.; Ma, X.Y.; Yang, X.Q.; Xiao, M.L.; Sun, H.; Ma, L.J.; Yu, X.L.; Ge, M.F. Metal organic framework-templated fabrication of exposed surface defect-enriched Co3O4 catalysts for efficient toluene oxidation. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2021, 603, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Li, T.T.; Zheng, Y.Q. Co3O4 nanosheet arrays treated by defect engineering for enhanced electrocatalytic water oxidation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.W.; Liu, Y.P.; Hao, R.; Tian, W.W.; Yuan, Z.Y. Urchin-like Al-Doped Co3O4 Nanospheres Rich in Surface Oxygen Vacancies Enable Efficient Ammonia Electrosynthesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 17502–17508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, C.S.; Sukumar, M.; Ravi, V.; Anitha, G.; Rajabathar, J.R.; Katubi, K.M.; Alsaiari, N.S.; Abualnaja, K.M.; Rajkumar, R.; Kamalakannan, M.; et al. Effect of Zinc Doping on Structural, Optical, Magnetic, and Catalytic Behavior of Co3O4 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Microwave-Assisted Combustion Method. J. Clust. Sci. 2023, 34, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Q.; Jie, B.R.; Zhai, Y.X.; Zeng, Y.J.; Kang, J.Y.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, X.D. Performance and mechanism of efficient activation of peroxymonosulfate by Co-Mn-ZIF derived layered double hydroxide for the degradation of enrofloxacin. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 394, 123723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.H.; Guo, X.F.; Wang, C.; Jia, L.H.; Zhao, Z.L.; Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Q.F. Ultra-responsive and selective ethanol and acetone sensor based on Ce-doped Co3O4 microspheres assembled by submicron spheres with multilayer core-shell structure. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 666, 131301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradov, M.B.; Mammadyarova, S.J.; Eyvazova, G.M.; Balayeva, O.O.; Hasanova, I.; Aliyeva, G.; Melikova, S.Z.; Abdullayev, M.I. The effect of Cu doping on structural, optical properties and photocatalytic activity of Co3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by sonochemical method. Opt. Mater. 2023, 142, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.W.; Zhou, X.Y.; Wu, W.B.; Zhu, C.F.; Weng, H.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, X.F.; Ye, B.J.; Han, R.D. Vacancy defects in epitaxial La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 thin films probed by a slow positron beam. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2004, 37, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, X.F.; Yoko, A.; Zhou, Y.; Jee, W.; Mayoral, A.; Liu, T.F.; Guan, J.C.; Lu, Y.; Keal, T.W.; Buckeridge, J.; et al. Surface-Driven Electron Localization and Defect Heterogeneity in Ceria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 33888–33902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Huang, J.H.; Ding, S.S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Wei, J.F.; Zhou, D.X.; Chu, H.X.; Bi, F.K.; Zhang, X.D. Catalytic oxidation of binary VOCs over MnO2 with different crystal structures: Mechanisms of promotion and inhibition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 382, 135895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Wang, Y.X.; Chen, J.N.; Hu, H.T.; Wei, J.F.; Bi, F.K.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.D. A Study on the Photothermal Catalytic Performance of Pt@MnO2 for O-Xylene Oxidation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bi, F.K.; Wei, J.F.; Gao, B.; Qiao, R.; Xu, J.C.; Liu, N.; Zhang, X.D. Boosting the Photothermal Oxidation of Multicomponent VOCs in Humid Conditions: Synergistic Mechanism of Mn and K in Different Oxygen Activation Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11341–11352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Y.; Hu, J.L.; Hou, J.C.; Wang, J.C.; Bao, W.R.; Chang, L.P. Study on the synthesis of CeO2-Co3O4 catalyst by flame spray pyrolysis method and its catalytic oxidation performance for ethane. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2025, 53, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Lyu, S.; Liu, C.C.; Zhao, Y.X.; Li, J.L. The Effect of Al2O3 Pore Diameter on the Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis Performance of Co/Al2O3 Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 3689–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.J.; Zheng, Y.B.; Feng, X.S.; Lin, D.F.; Qian, Q.R.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, Q.H.; Zhang, X.H. Controllable P Doping of the LaCoO3 Catalyst for Efficient Propane Oxidation: Optimized Surface Co Distribution and Enhanced Oxygen Vacancies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23789–23799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Shi, X.J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, M.J.; Zhu, D.D.; Ho, W.; Cao, J.J.; Lee, S. Catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde on ultrathin Co3O4 nanosheets at room temperature: Effect of enhanced active sites exposure on reaction path. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 319, 121902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, S.; Yu, H.Q.; Wang, X.X.; Liu, S.C.; Feng, Y.; Song, Z.X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.J. Regulating surface properties of Co3O4@MnO2 catalysts through Co3O4-MnO2 interfacial effects for efficient toluene catalytic oxidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 352, 128221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, P.F.; Zhang, X.; Xia, D.T.; Zhao, P.; Meng, J.; Feng, N.J.; Wan, H.; Guan, G.F. Tuning the water resistance of Co3O4 catalysts via Ce incorporation for enhanced catalytic oxidation of toluene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 692, 162721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Cao, J.; Tian, S.H.; Zhang, X.X.; Yang, Y.D.; Gong, Z.A.; Yao, X.J. Supported Co3O4 catalyst on modified UiO-66 by Ce4+ for completely catalytic oxidation of toluene. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 1425–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.Y.; Li, W.C.; Yan, J.X.; Wang, X.J.; Ren, E.B.; Shi, Z.F.; Li, J.; Ding, X.G.; Mo, S.P.; Mo, D.Q. Strong Metal-Support Interaction in Pd/CeO2 Promotes the Catalytic Activity of Ethyl Acetate Oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsolakis, M.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Marnellos, G.E.; Asad, M.F.; Soares, O.S.G.P.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Figueiredo, J.L. Effect of cobalt loading on the solid state properties and ethyl acetate oxidation performance of cobalt-cerium mixed oxides. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2017, 496, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.C.; Gao, L.J.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.H.; Mo, L.Y.; Zhang, X.D. Effect of CuO species and oxygen vacancies over CuO/CeO2 catalysts on low-temperature oxidation of ethyl acetate. J. Rare Earths 2023, 41, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.D.; Feng, X.B.; Yang, R.; Li, L.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Chen, C.W.; He, C. Engineering CoCexZr1−x/Ni foam monolithic catalysts for ethyl acetate efficient destruction. Fuel 2022, 317, 123574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.P.; Meng, Q.J.; Chen, M.L.; Luo, X.Q.; Dai, Q.G.; Lu, H.F.; Wu, Z.B.; Weng, X.L. Selective Ru Adsorption on SnO2/CeO2 Mixed Oxides for Efficient Destruction of Multicomponent Volatile Organic Compounds: From Laboratory to Practical Possibility. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 9762–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.L.; Shi, Y.J.; Kong, F.Z.; Zhou, R.X. Low-temperature VOCs oxidation performance of Pt/zeolites catalysts with hierarchical pore structure. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 124, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, F.K.; Wang, Y.X.; He, J.Y.; Qu, H.Y.; Li, H.X.; Liu, B.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.D. Mn-MOFs with Different Morphologies Derived MnOx Catalysts for Efficient CO Catalytic Oxidation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Chen, T.Y.; Zhao, S.Q.; Wu, P.; Chong, Y.N.; Li, A.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, G.X.; Jin, X.J.; Qiu, Y.C.; et al. Engineering Cobalt Oxide with Coexisting Cobalt Defects and Oxygen Vacancies for Enhanced Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 4906–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Wang, Y.X.; Cao, M.K.; He, Z.Q.; Qiao, R.; Bi, F.K.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.D. Preparation of CeXMn1−XO2 Catalysts with Strong Mn-Ce Synergistic Effect for Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene. Materials 2025, 18, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.T.; Deng, H.; Lu, Y.Z.; Ma, J.Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.B.; He, H. Synergistic Catalytic Oxidation of Typical Volatile Organic Compound Mixtures on Mn-Based Catalysts: Significant Promotion Effect and Reaction Mechanism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Z.B. A novel hybrid Bi2MoO6-MnO2 catalysts with the superior plasma induced pseudo photocatalytic-catalytic performance for ethyl acetate degradation. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 254, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.D.; Yang, R.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Chen, C.W.; Liu, Q.Y.; Albilali, R.; He, C. Fabricating M/Al2O3/Cordierite (M = Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni and Cu) Monolithic Catalysts for Ethyl Acetate Efficient Oxidation: Unveiling the Role of Water Vapor and Reaction Mechanism. Fuel 2021, 303, 121244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, L.K.; Wang, Z.W.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.X.; Dai, H.X.; Wang, Z.H.; Deng, J.G. Photothermal synergistic catalytic oxidation of ethyl acetate over MOFs-derived mesoporous N-TiO2 supported Pd catalysts. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 322, 122075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.P.; Zhao, X.; Huang, L.L.; Zhou, J.J.; Li, S.D.; Peng, R.S.; Tu, Z.H.; Liao, L.; Xie, Q.L.; Chen, Y.F.; et al. Uncovering the Role of Unsaturated Coordination Defects in Manganese Oxides for Concentrated Solar-Heating Photothermal OVOCs Oxidation: Experimental and DFT Explorations. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 342, 123435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, H. Reduced Graphene Oxide as An Effective Promoter to The Layered Manganese Oxide-Supported Ag Catalysts for The Oxidation of Ethyl Acetate and Carbon Monoxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Innocenti, G.; Ferbinteanu, M.; Ramos-Fernandez, E.V.; Sepulveda-Escribano, A.; Wu, H.; Cavani, F.; Rothenberg, G.; Shiju, N.R. Understanding the Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethyl Lactate to Ethyl Pyruvate over Vanadia/Titania. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 3737–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.D.; Yang, R.; He, C.; Jiang, Z.Y.; Shi, J.W.; Albilali, R.; Fayaz, K.; Liu, B.J. Pd-Based Catalysts Promoted by Hierarchical Porous Al2O3 and ZnO Microsphere Supports/Coatings for Ethyl Acetate Highly Active and Stable Destruction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 132281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, M.; Wu, S.; Lan, L.; Zhao, X. Novel Photoactivation and Solar-Light-Driven Thermocatalysis on ε-MnO2 Nanosheets Lead to Highly Efficient Catalytic Abatement of Ethyl Acetate without Acetaldehyde as Unfavorable By-Product. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 14195–14206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.M.; Liu, Y.X.; Deng, J.G.; Jing, L.; Hou, Z.Q.; Wang, Z.W.; Lu, W.; Yu, X.H.; Dai, H.X. Catalytic Performance and Reaction Mechanisms of Ethyl Acetate Oxidation over the Au–Pd/TiO2 Catalysts. Catalysts 2023, 13, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Han, Q.Z.; Shi, W.B.; Zhang, C.; Li, E.W.; Zhu, T.Y. Catalytic oxidation of ethyl acetate over Ru–Cu bimetallic catalysts: Further insights into reaction mechanism via in situ FTIR and DFT studies. J. Catal. 2019, 369, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.C.; Xu, J.; Gao, L.J.; Zang, S.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Wang, L.H.; Mo, L.Y. CuO/CeO2 Catalysts Prepared by Modified Impregnation Method for Ethyl Acetate Oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mo, S.; Ding, X.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, M.; Xie, Q.; Ye, D. Hollow Cavity Engineering of MOFs-Derived Hierarchical MnOx Structure for Highly Efficient Photothermal Degradation of Ethyl Acetate under Light Irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.L.; Liu, P.X.; Wang, Z.H.; Tang, H.R.; He, Y.; Zhu, Y.Q. Efficient Catalytic Ozonation of Ethyl Acetate over Cu-Mn Catalysts: Further Insights into the Reaction Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Y.F.; Song, C.F.; Liu, Q.L.; Ji, N.; Ma, D.G.; Lu, X.B. Novel monolithic catalysts derived from in-situ decoration of Co3O4 and hierarchical Co3O4@MnOx on Ni foam for VOC oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 265, 118552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalysts | Crystal Size (nm) a | Lattice Parameters (Å) b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | ||

| Co3O4 | 20.8 | 8.08372 | 8.08372 | 8.08372 |

| Al@Co3O4 | 14.6 | 8.07201 | 8.07201 | 8.07201 |

| Al@Co3O4-4 | 12.5 | 8.06814 | 8.06814 | 8.06814 |

| Al@Co3O4-6 | 12.4 | 8.06140 | 8.06140 | 8.06140 |

| Al@Co3O4-8 | 13.2 | 8.06884 | 8.06884 | 8.06884 |

| Catalysts | SBET (m2/g) a | V (cm3/g) b | D (nm) c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co3O4 | 43.6 | 0.278 | 1.4–3.8, 6.5–17.3 |

| Al@Co3O4 | 184.2 | 0.348 | 1.4–6.5 |

| Al@Co3O4-4 | 201.5 | 0.388 | 1.4–6.5 |

| Al@Co3O4-6 | 205.4 | 0.370 | 1.4–6.5 |

| Al@Co3O4-8 | 169.8 | 0.350 | 1.4–6.5 |

| Catalysts | T10 (°C) | T50 (°C) | T90 (°C) | Reaction Activation Energy (Ea, kJ/mol) | Reaction Rate at 200 °C (r, μmol/(gcat·h)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co3O4 | 193 | 221 | 238 | 109.3 | 0.049 |

| Al@Co3O4 | 181 | 210 | 227 | 80.2 | 0.104 |

| Al@Co3O4-4 | 173 | 205 | 220 | 56.7 | 0.144 |

| Al@Co3O4-6 | 160 | 194 | 207 | 46.3 | 0.257 |

| Al@Co3O4-8 | 190 | 215 | 233 | 82.5 | 0.063 |

| Catalysts | Preparation Method | Ethyl Acetate Concentration (ppm) | Reaction Flow (mL/(g·h)) | Catalytic Performance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co3O4 | - | 1000 | 60,000 | T90 = 250 °C | [19] |

| Co3O4-15Cu | Impregnation method | 1000 | 60,000 | T90 = 226 °C | [19] |

| NR-Co3O4 | Hydrothermal method | 1000 | 30,000 | T100 = 260 °C | [17] |

| CeO2-NC | Hydrothermal method | 1000 | 60,000 | T90 = 229 °C | [48] |

| 20Co/CeO2 | Impregnation method | 466.7 | 60,000 | T100 = 260 °C | [49] |

| CuO/CeO2 | Ball milling method | 1000 | 60,000 | T100 = 220 °C | [50] |

| CoCe0.75Zr0.25-NF | Sol–gel method | 1000 | 60,000 | T90 = 227 °C | [51] |

| Ru/Sn-Ce-(5.8) | Wet impregnation method | 500 | 10,000 | T100 = 250 °C | [52] |

| Pt/S-1 | Ethylene glycol method | 1000 | 22,500 | T90 = 238 °C | [53] |

| Al@Co3O4-6 | Hydrothermal method | 1000 | 30,000 | T90 = 207 °C | This work |

| Position (cm−1) | Assignment | Characteristic of | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~2986, ~2940, ~2912, ~2880 | C–H stretching modes | -CH3 | [57,58] |

| ~1713 | C=O vibration of ester carbonyl | Ethyl acetate | [59,60] |

| ~1558, ~1403 | Asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibration of COO- | Acetate acid | [61,62] |

| ~1479, ~1378, ~1098, ~1047 | Adsorbed EA molecules | Ethyl acetate | [57,63] |

| ~1277 | C–O vibration of ethyl acetate | Ethyl acetate | [59] |

| ~1156 | C–O vibration of vinyl acetate | Vinyl acetate | [64] |

| Position (cm−1) | Assignment | Characteristic of | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~1722 | C=O stretching vibration of acetaldehyde | Acetaldehyde | [61,65] |

| ~1675 | C=C stretching vibration of ethylene | ethylene | [64] |

| ~1591, ~1564 | Antisymmetric stretching vibrations of COO- | Formate and acetic acid species | [51,66] |

| ~1448, ~1399 | Symmetric stretching vibration of COO- | Formate and acetic acid species | [51,67] |

| ~1334 | O–H deformation vibration of ethanol | Ethanol | [59,63,68] |

| ~1255 | C–O stretching vibration of the acetate species | Acetate acid | [69] |

| ~1116, ~1052 | C–O stretching vibration of ethanol | Ethanol | [70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, J.; Liu, S.; Li, D.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, F.; Zhang, X. The Etching of Al-Doped Co3O4 with NaOH to Enhance Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation. Catalysts 2026, 16, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020158

Wei J, Liu S, Li D, Yu H, Wang Y, Bi F, Zhang X. The Etching of Al-Doped Co3O4 with NaOH to Enhance Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020158

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Jiafeng, Shuchen Liu, Dongqi Li, Haiyang Yu, Yuxin Wang, Fukun Bi, and Xiaodong Zhang. 2026. "The Etching of Al-Doped Co3O4 with NaOH to Enhance Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020158

APA StyleWei, J., Liu, S., Li, D., Yu, H., Wang, Y., Bi, F., & Zhang, X. (2026). The Etching of Al-Doped Co3O4 with NaOH to Enhance Ethyl Acetate Catalytic Degradation. Catalysts, 16(2), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020158