TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Hybrid Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Crystal Violet Dye and Toxic Volatile Butyraldehyde

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

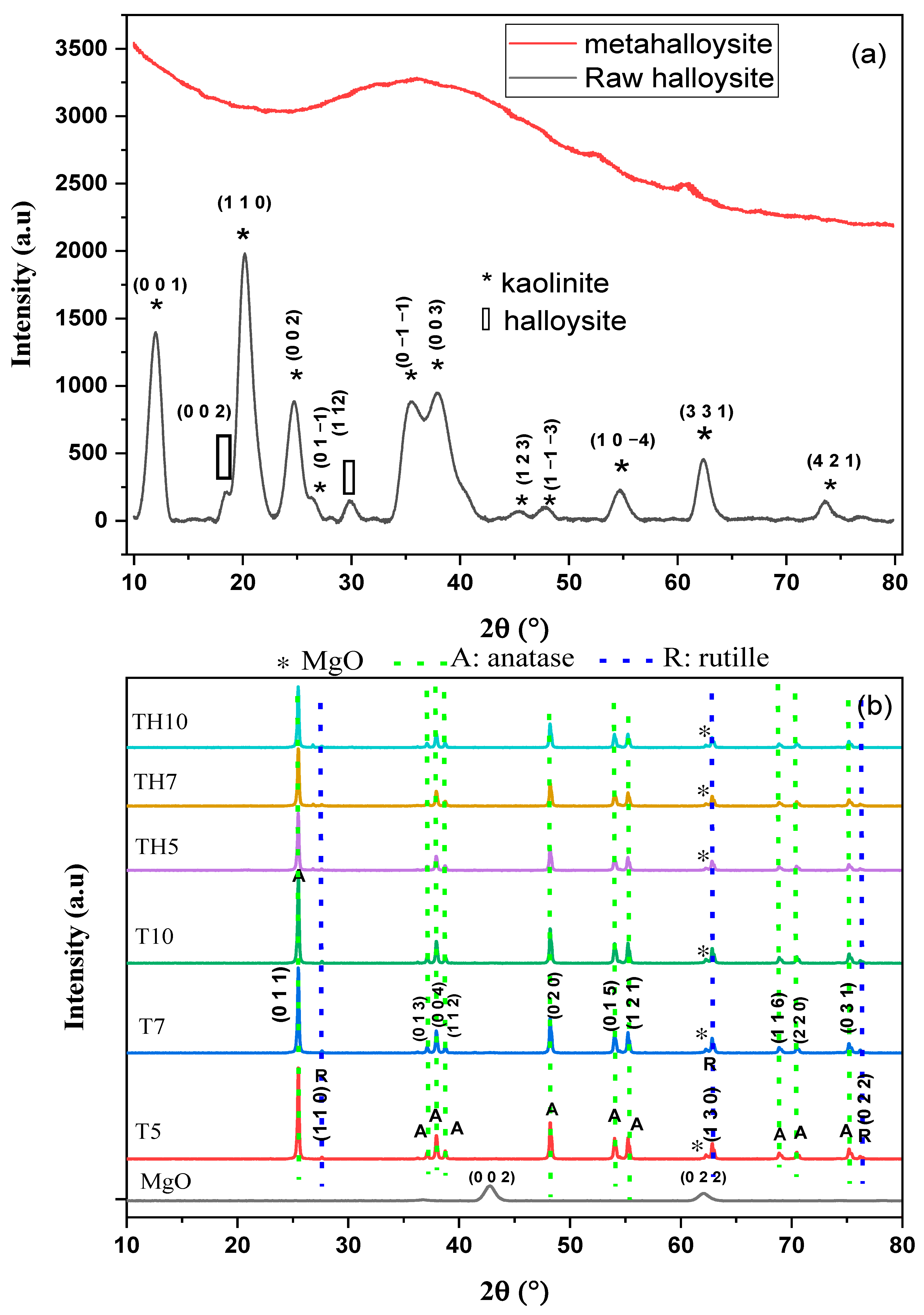

2.1. XRD Spectrum

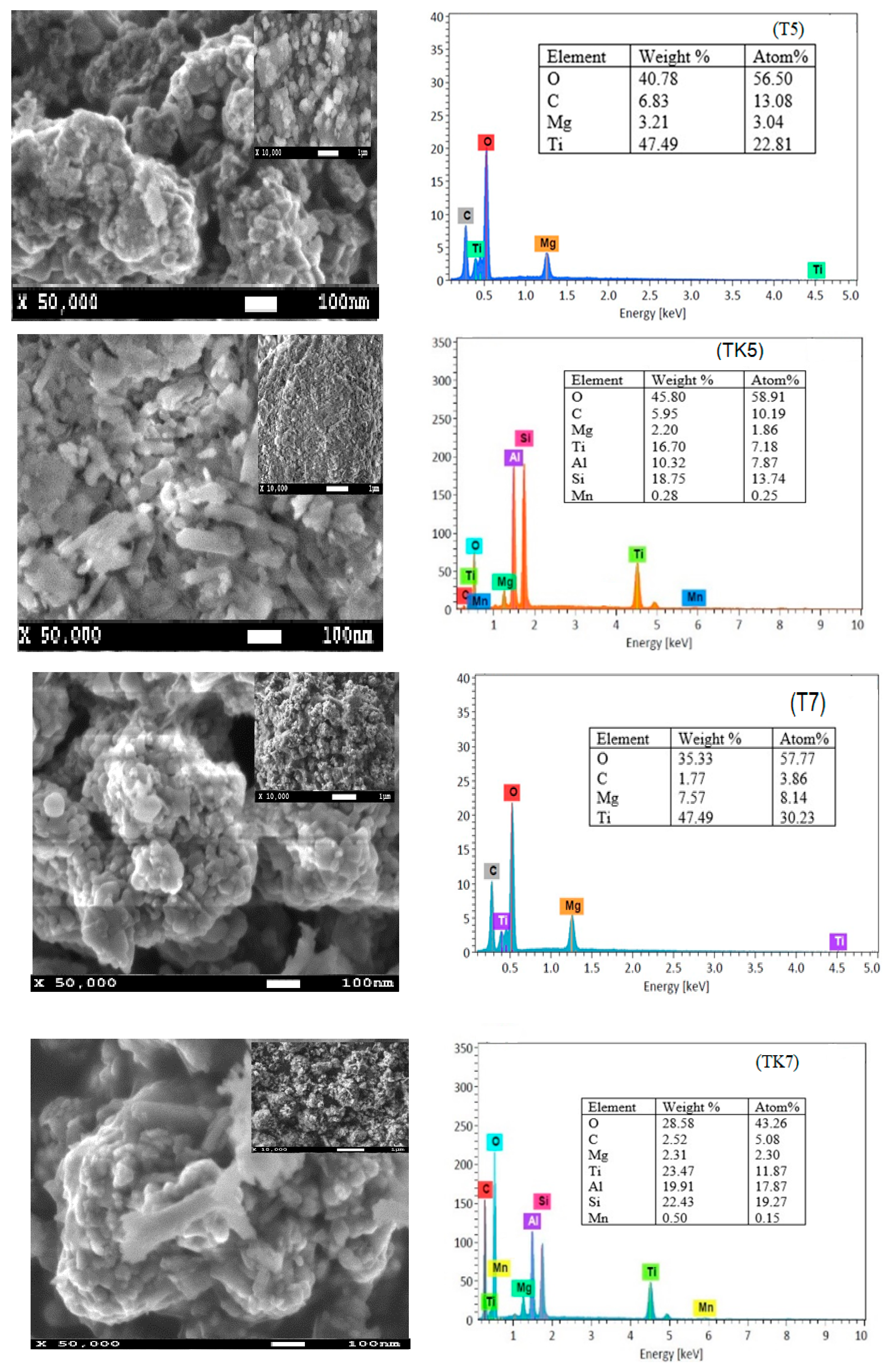

2.2. SEM and EDX Analysis

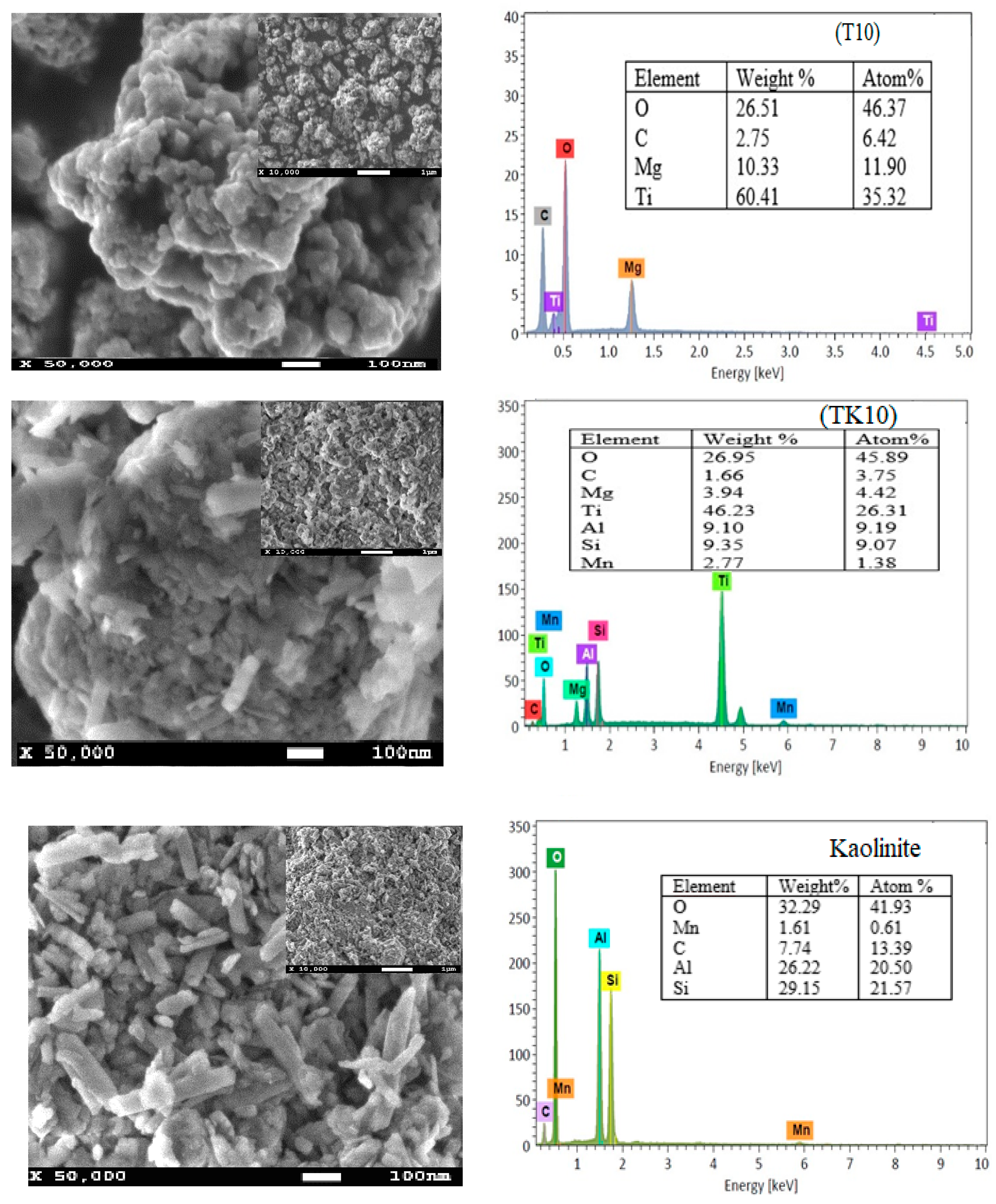

2.3. BET Analysis

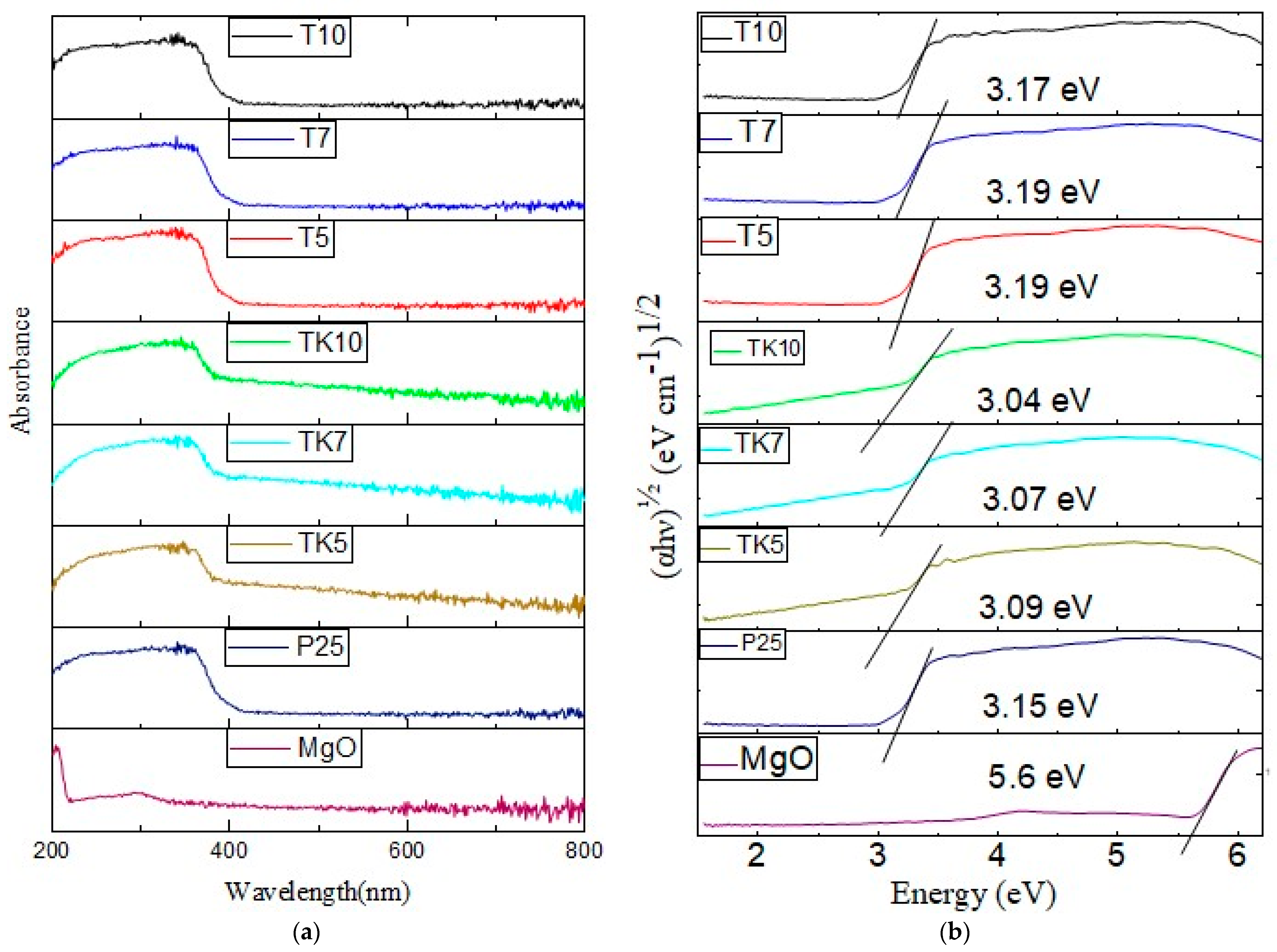

2.4. DRS UV–Vis Spectra

2.5. Infrared Spectrum (ATR)

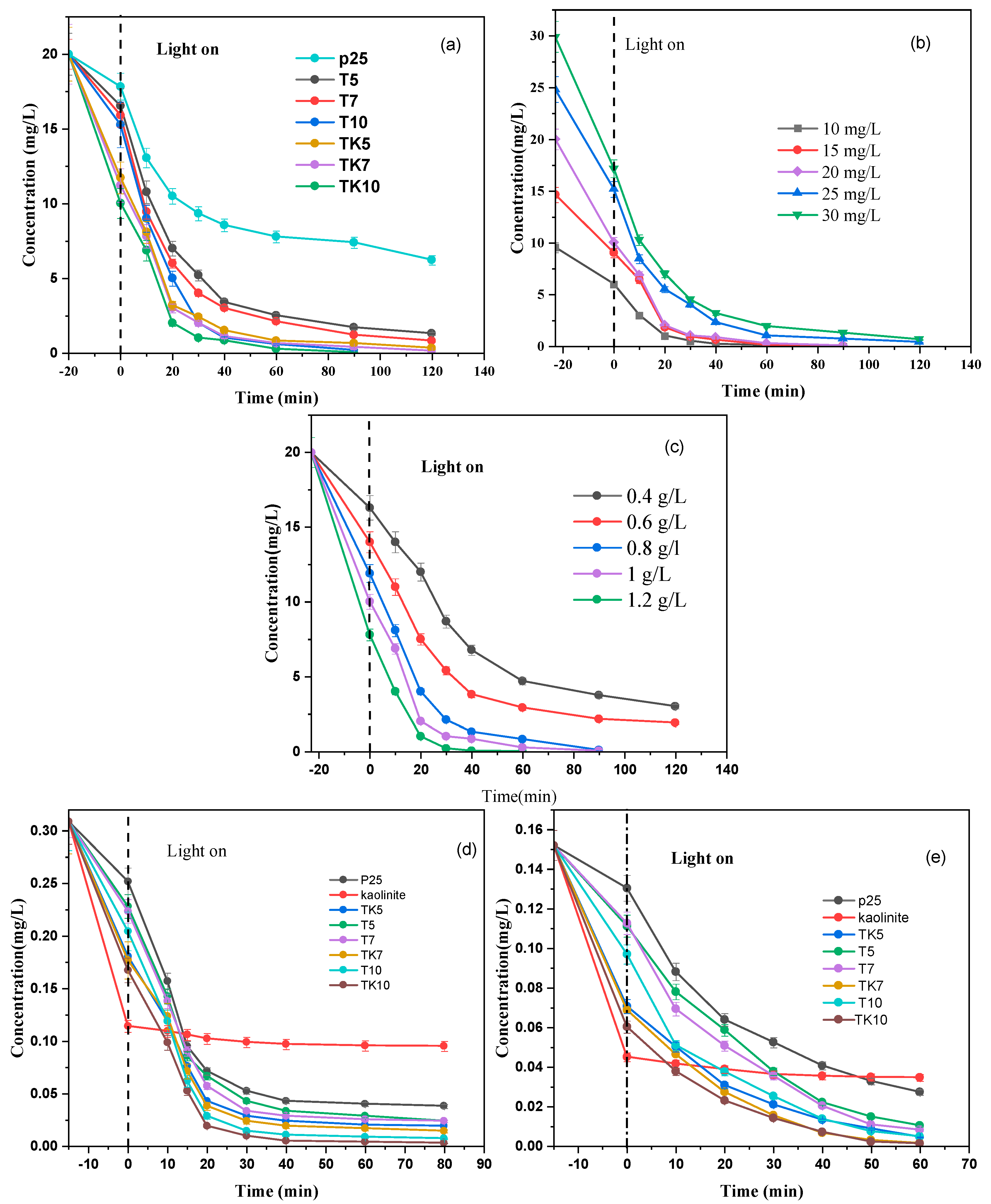

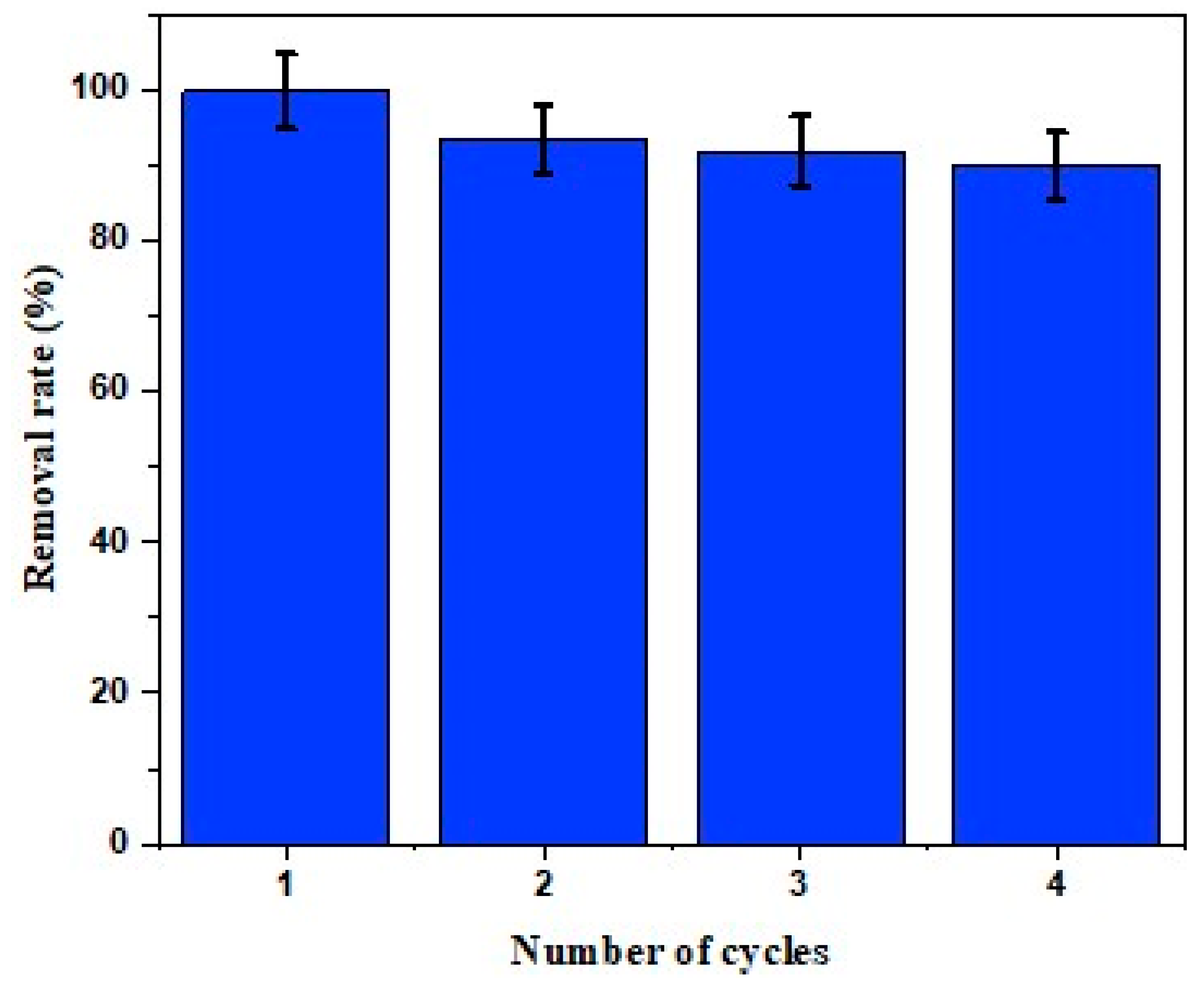

2.6. Photocatalytic Experiments

2.7. Effect of Dye Concentration

2.8. Influence of Photocatalyst Amount

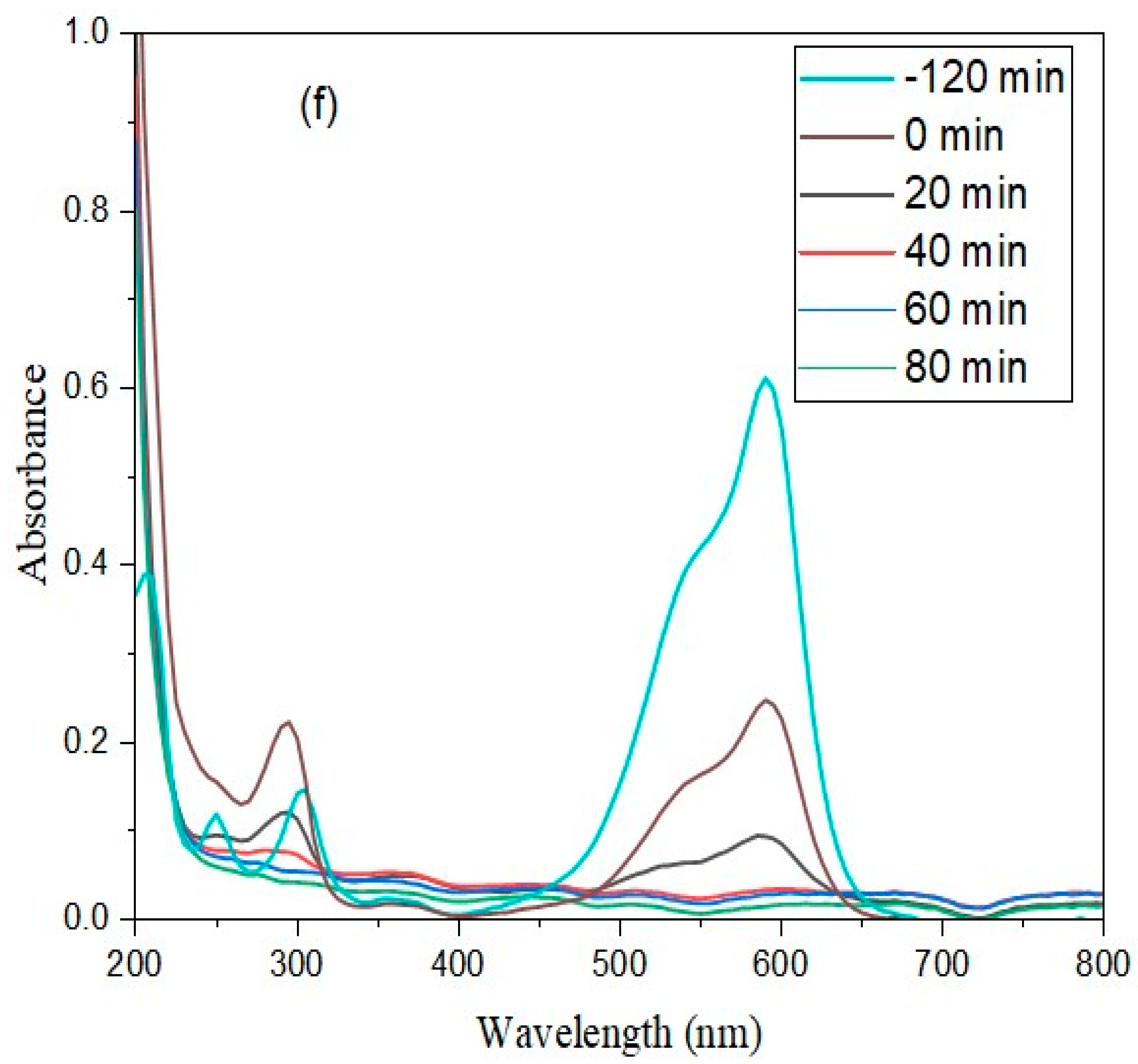

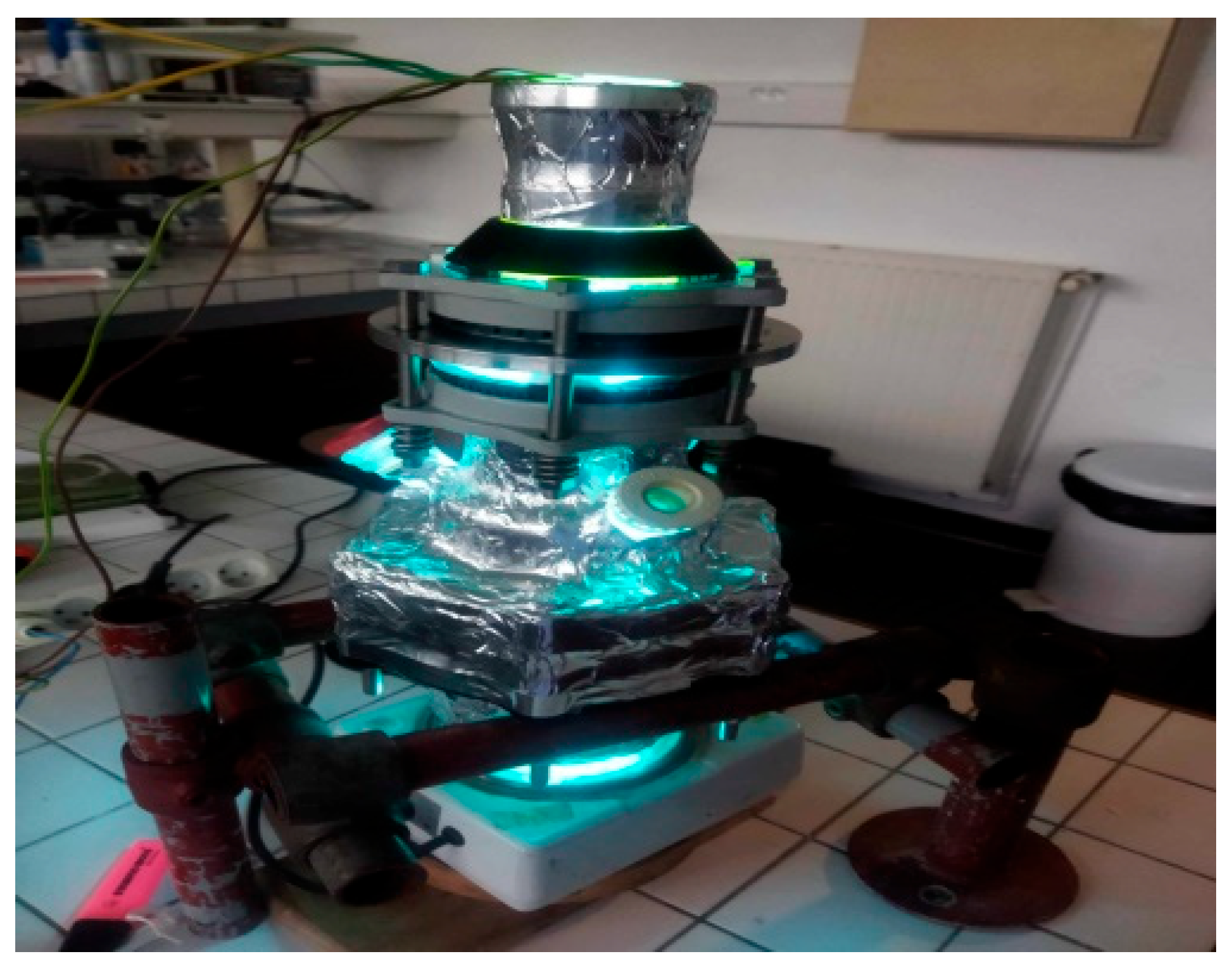

2.9. Air Treatment

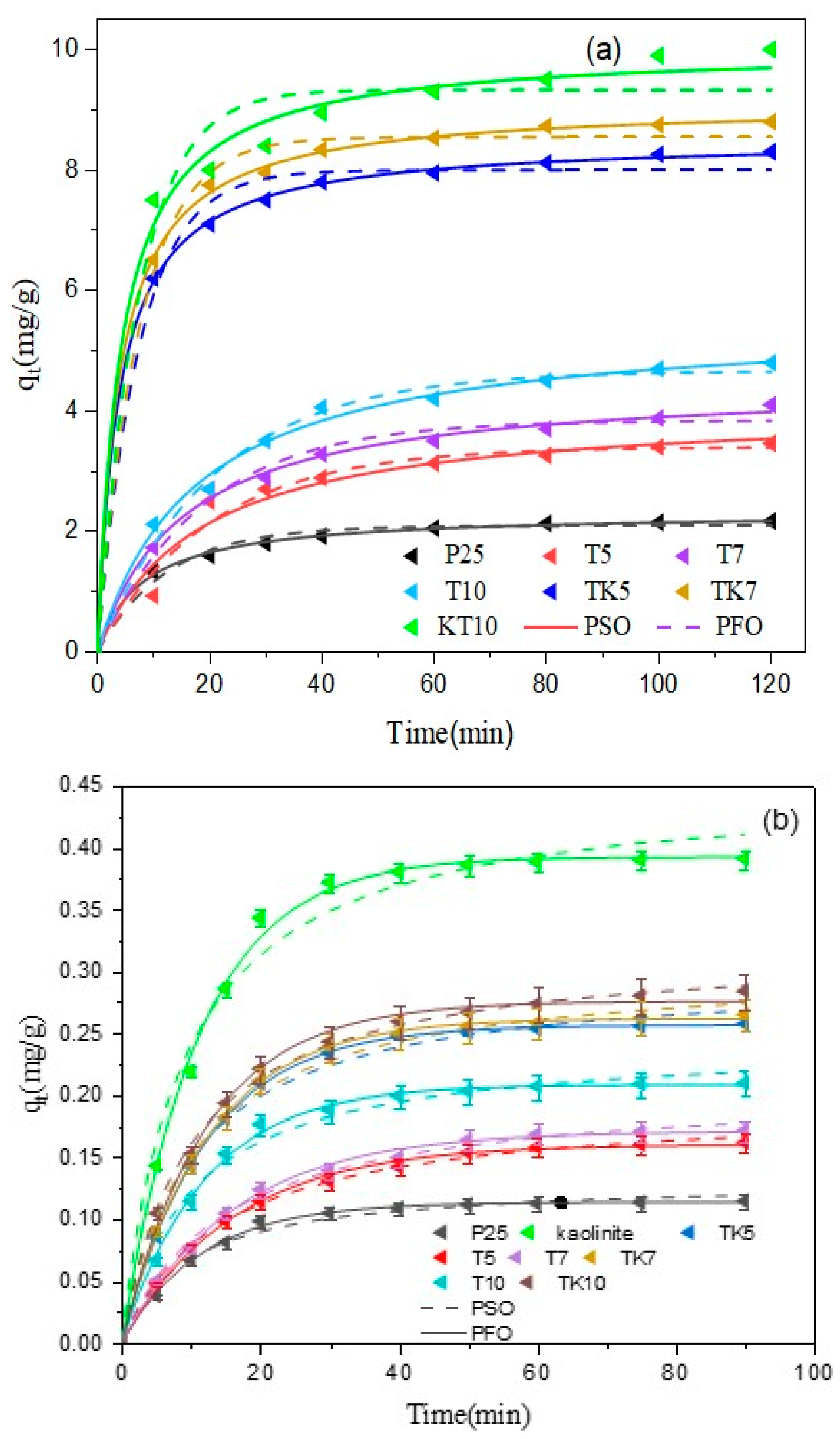

2.10. Adsorption Study

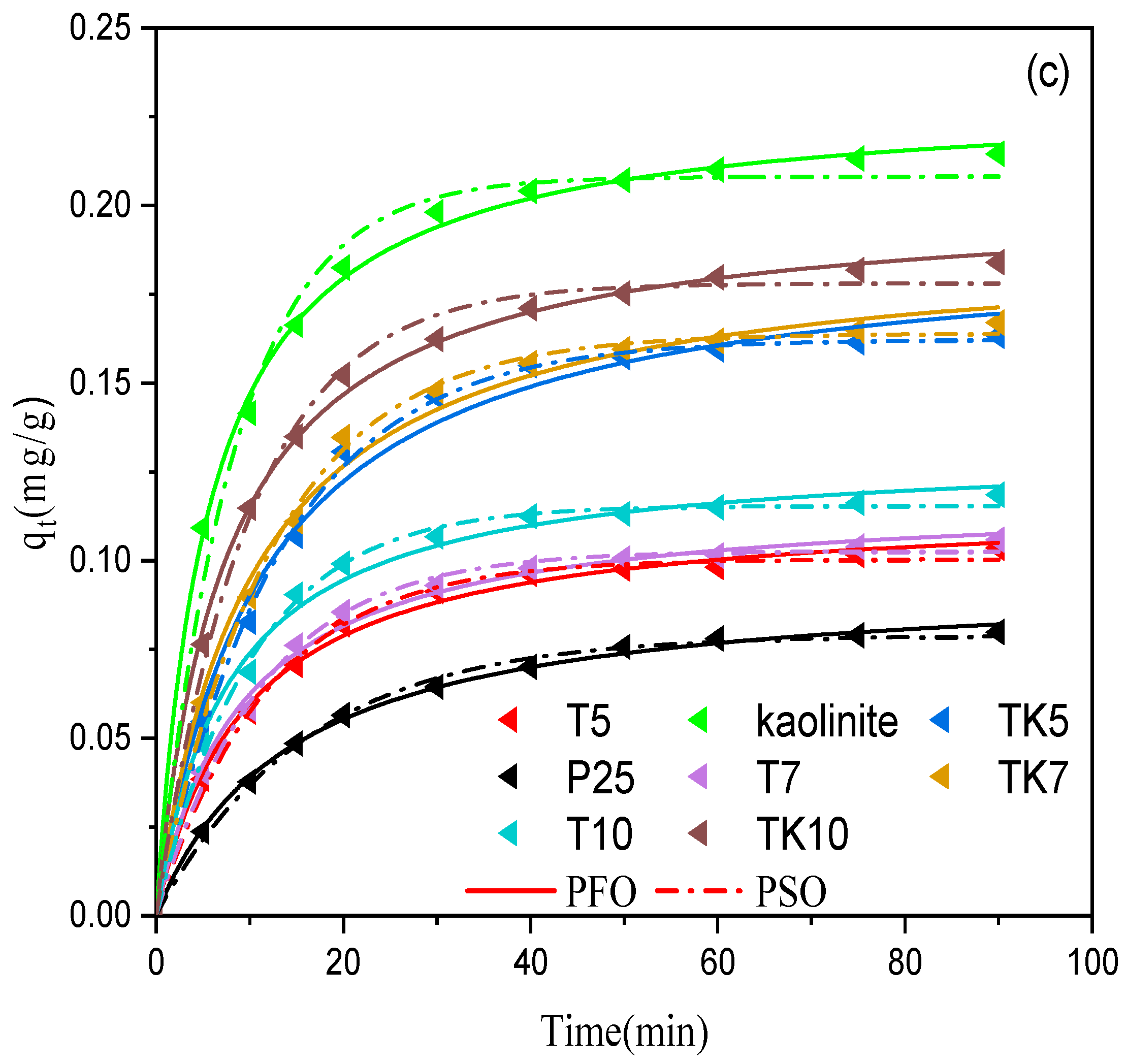

Adsorption Kinetics

- is higher, K increasing, so the value of 1 + K ≈ K

- is lower, K ≪ 1, to be a result, the denominator 1 + K ≈ 1

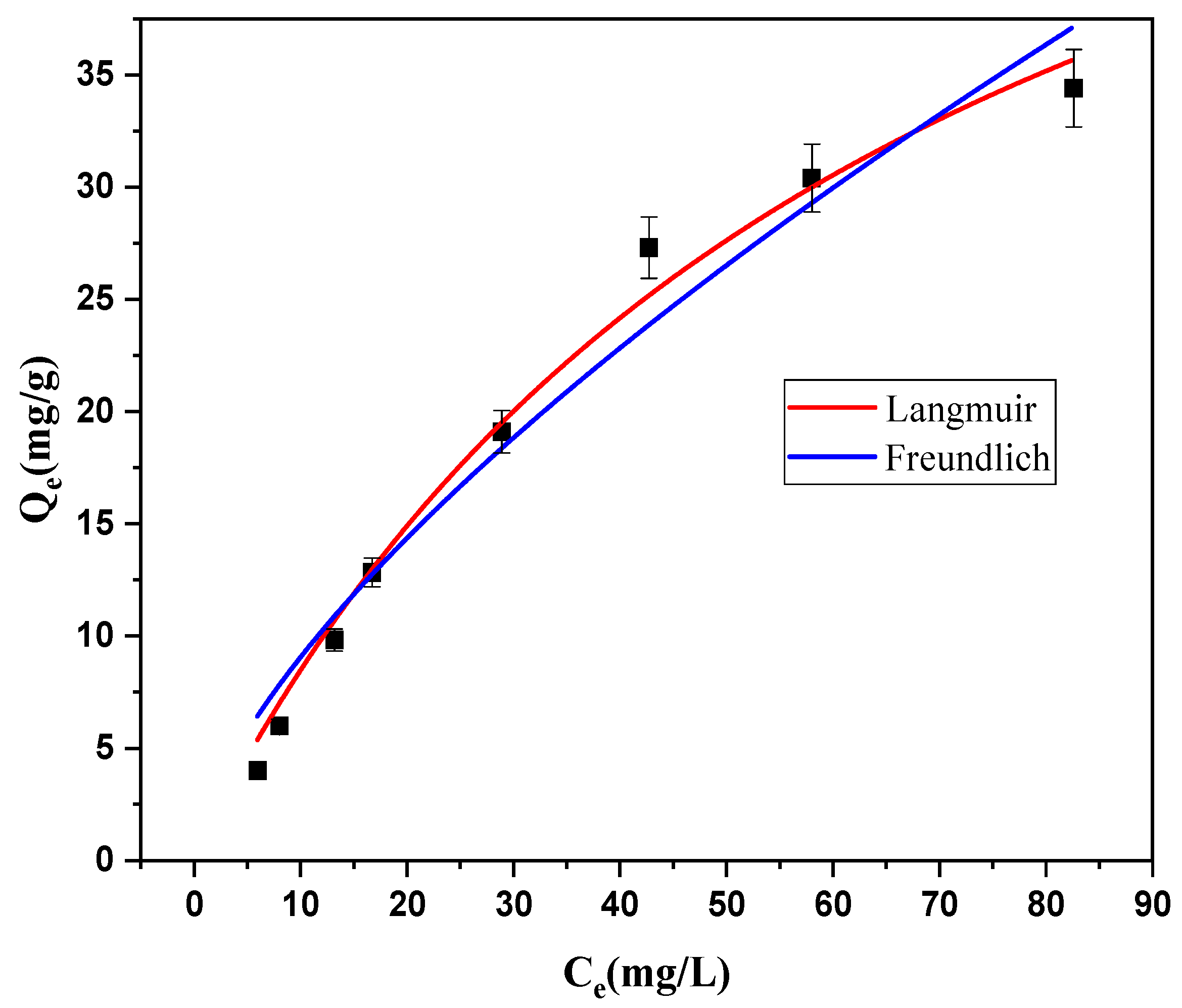

2.11. Adsorption Isotherms

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Nanocomposites

3.3. Characterization of TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Composite

3.4. Adsorption Kinetic Experiment

3.5. Evaluation of the Photoactivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Damgaard, A.; Riber, C.; Fruergaard, T.; Hulgaard, T.; Christensen, T.H. Life-cycle-assessment of the historical development of air pollution control and energy recovery in waste incineration. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winchester, J.W.; Nifong, G.D. Water pollution in lake michigan by trace elements from pollution aerosol fallout. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1971, 1, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, C.; Sumana, G. Highly effective adsorption of crystal violet dye from contaminated water using graphene oxide intercalated montmorillonite nanocomposite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 166, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.I.; Rasli, A.M.; Awan, U.; Ma, J.; Ali, G.; Faridullah; Alam, A.; Sajjad, F.; Zaman, K. Environment and air pollution: Health services bequeath to grotesque menace. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 3467–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela, R.; Suárez, S.; Rasmussen, S.; Canela, M.; Ávila, P.; Sánchez, B. Photocatalysis for continuous air purification in wastewater treatment plants: From lab to reality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5040–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Bharagava, R.N. Exposure to crystal violet. its toxic, genotoxic and carcinogenic effects on environment and its degradation and detoxification for environmental safety. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 237, 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabryanty, R.; Valencia, C.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Putro, J.N.; Santoso, S.P.; Kurniawan, A.; Ju, Y.H.; Ismadji, S. Removal of crystal violet dye by adsorption using bentonite—Alginate composite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5677–5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, D.H.; Li, K. Photocatalytic oxidation of butyraldehyde over titania in air: By-product identification and reaction pathways. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2003, 190, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkrob, I.A.; Sauer, M.C. Hole scavenging and photo-stimulated recombination of electron-hole pairs in aqueous TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 12497–12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassby, D.; Budarz, J.F.; Wiesner, M. Impact of aggregate size and structure on the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6934–6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Kwon, H.H.; Lim, T.H.; Hong, S.A.; Lee, H.I. Development of nickel catalyst supported on MgO-TiO2 composite oxide for DIR-MCFC. Catal. Today 2004, 93–95, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.M.; Sorensen, C.M.; Klabunde, K.J. MgO-TiO2 mixed oxide nanoparticles: Comparison of flame synthesis versus aerogel method; Characterization. and photocatalytic activities. J. Mater. Res. 2013, 28, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Lee, B.K. Surfactant-aided sol-gel synthesis of TiO2–MgO nanocomposite and their photocatalytic azo dye degradation activity. J. Compos. Mater. 2020, 54, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihoubi, N.; Ferhat, S.; Nedjhioui, M.; Zenati, B.; Lekmine, S.; Boudraa, R.; Ola, M.S.; Zhang, J.; Amrane, A.; Tahraoui, H. A Novel Halophilic Bacterium for Sustainable Pollution Control: From Pesticides to Industrial Effluents. Water 2025, 17, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolde, G.S.; Kuo, D.; Abdullah, H. Solar-light-driven ternary MgO/TiO2/g-C3N4 heterojunction photocatalyst with surface defects for dinitrobenzene pollutant reduction. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikal, D.; Kallingal, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo and Anthraquinone dye using TiO2/MgO nanocomposite immobilized Chitosan hydrogels. Environ. Technol. 2019, 42, 2278–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Mehta, A.; Sharma, M.; Basu, S. Enhanced heterogeneous photodegradation of VOC and dye using microwave synthesized TiO2/Clay nanocomposites: A comparison study of different type of clays. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulis, D.; Komarneni, S.; Panagiotaras, D.; Stathatos, E.; Toli, D.; Christoforidis, K.C.; Fernández-garcía, M.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Sato, T.; et al. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental Halloysite—TiO2 nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 132–133, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanik, B. Applied Clay Science Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over clay-TiO2 nanocomposites: A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 141, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulis, D.; Komarneni, S.; Nikolopoulou, A.; Tsolis-Katagas, P.; Panagiotaras, D.; Kacandes, H.G.; Zhang, P.; Yin, S.; Sato, T.; Katsuki, H. Palygorskite- and Halloysite-TiO2 nanocomposites: Synthesis and photocatalytic activity. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 50, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, J.; Feng, S.; Yang, Z.; Ding, S. Low-temperature synthesis of heterogeneous crystalline TiO2-halloysite nanotubes and their visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2013, 1, 8045–8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Wang, D.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Feng, P.; Ou, X.; Qiang, Y.; Garcia, H.; Niu, J. A comparative photocatalytic study of TiO2 loaded on three natural clays with different morphologies. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 183, 105352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashery, S.E.A.; Ibrahim, I.; Gomaa, H.; El-Bouraie, M.M.; Moneam, I.A.; Fekry, S.S.; Mohamed, G.G. Comparative Study of the Photocatalytic Degradation of Crystal Violet Using Ferromagnetic Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles and MgO-Bentonite Nanocomposite. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloyi, J.; Ntho, T.; Moma, J. Synthesis and application of pillared clay heterogeneous catalysts for wastewater treatment: A review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 5197–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, P.; Qin, A.; Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liao, L.; Zhang, K.; Qin, Y. One-Step Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped TiO2 Heterojunctions and Their Visible Light Catalytic Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, K.; Baishnisha, A.; Balakumar, V.; Perumal, N.K.; Meenakshi, C.; Kannan, R.S. Photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline under visible light using TiO2@sulfur doped carbon nitride nanocomposite synthesized via in-situ method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.D.; Tran, T.P.A.; Vu, T.H.; Dao, T.P.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Vasseghian, Y.; Joo, S.W. Integrating 3D-printed Mo2CTx-UiO-66@rGQDs nanocatalysts with semiconducting BiVO4 to improve interfacial charge transfer and photocatalytic degradation of atrazine. Appl. Catal. B 2025, 365, 124924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, E.; Poursalehi, R.; Delavari, H. Ternary Bi2O3/(BiO)2CO3/g-C3N4 multi-heterojunction nanoflakes for highly efficient photocatalytic degradation of dyes and xanthates under visible light. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2025, 10, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chen, J.; Hong, X.; Cui, J.; Li, L. One-Pot Synthesis of TiO2/Hectorite Composite and Its Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.M.; Alenezi, J.F.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yasin, A.S.; Hashem, A.F.M.; Abdal-hay, A. Synthesis of TiO2@ZnO heterojunction for dye photodegradation and wastewater treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 886, 161169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewnet, A.; Abebe, M.; Asaithambi, P.; Alemayehu, E. Visible-Light-Driven g-C3N4/TiO2 Based Heterojunction Nanocomposites for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes in Wastewater: A Review. Air Soil Water Res. 2022, 15, 11786221221117266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkacem, S.; Boudeghdegh, K.; Zehani, F.; Hamidouche, M.; Belhocine, Y. Preparation, microstructure studies and mechanical properties of glazes ceramic sanitary ware based on kaolin. Sci. Sinter. 2021, 53, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoussi, H.; Osmani, H.; Courtois, C.; Bourahli, M.E.H. Mineralogical and chemical characterization of DD3 kaolin from the east of Algeria. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2016, 55, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrini, L.; Toja, R.M.; Conconi, M.S.; Requejo, F.G.; Rendtorff, N.M. Halloysite nanotube and its firing products: Structural characterization of halloysite. metahalloysite, spinel type silicoaluminate and mullite. J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenom. 2019, 234, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, A.M.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Mojiri, A.; Sonne, C.; Cho, J.; Rezania, S.; Vasseghian, Y. Photocatalytic removal of ceftriaxone from wastewater using TiO2/MgO under ultraviolet radiation. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 115915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Zheng, P. Adsorption and photodegradation of methylene blue on TiO2-halloysite adsorbents. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 2051–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrane, B.; Ouedraogo, E.; Mamen, B.; Djaknoun, S.; Mesrati, N. Experimental study of the thermo-mechanical behaviour of alumina-silicate refractory materials based on a mixture of Algerian kaolinitic clays. Ceram. Int. 2011, 37, 3217–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talat-Mehrabad, J.; Khosravi, M.; Modirshahla, N.; Behnajady, M.A. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of co-doped Ag–, Mg–TiO2-P25 by photodeposition and impregnation methods. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 10451–10461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheloui, M.; Boumchedda, K.; Naitbouda, A. Study, with Different Characterization Techniques, of the Formation of Cordierite from both Natural and Activated Algerian DD3 Kaolin. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 2020, 79, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwubiko, V.; Matsushita, Y.; Elshehy, E.A.; El-Khouly, M.E. Facile synthesis of TiO2-carbon composite doped nitrogen for efficient photodegradation of noxious methylene blue dye. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 34298–34310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, A.; Muzakki, A.; Saleh, R. Effect of nanographene platelets on adsorption and sonophotocatalytic performances of TiO2/CuO composite for removal of organic pollutants. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 99, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.N.; Engole, M.; Imran, S.M.; Jeon, S.J.; Kim, H.T. Sol-gel synthesis of photoactive kaolinite-titania: Effect of the preparation method and their photocatalytic properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 331, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, C.; Juang, R. Structure and thermal stability of toxic chromium (VI) species doped onto TiO2 powders through heat treatment. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, P.; Sharma, S.K.; Toor, A.P. Techno-economic evaluation of anatase and p25 TiO2 for treatment basic yellow 28 dye solution through heterogeneous photocatalysis. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, J.; Hadapangoda, C.C.; Jayasekera, W.G. TiO2/MgO composite photocatalyst: The role of MgO in photoinduced charge carrier separation. Appl. Catal. B 2004, 50, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, K.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z. TiO2 nanoparticles assembled on kaolinites with different morphologies for efficient photocatalytic performance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutlákova, K.M.; Tokarský, J.; Kovář, P.; Vojtěšková, S.; Kovářová, A.; Smetana, B.; Kukutschová, J.; Čapková, P.; Matějka, V. Preparation and characterization of photoactive composite kaolinite/TiO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 188, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjltaief, H.B.; Galvez, M.E.; Zina, M.B.; Da Costa, P. TiO2/clay as a heterogeneous catalyst in photocatalytic/photochemical oxidation of anionic reactive blue 19. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, A.M.; Amer, M.W.; Al-aqarbeh, M.M. TiO2-kaolinite nanocomposite prepared from the Jordanian Kaolin clay: Adsorption and thermodynamic of Pb (II) and Cd (II) ions in aqueous solution. Chem. Int. 2020, 6, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Hennemann, B.; Zanatta, N.; Foletto, E.L. Photocatalytic Efficiency of TiO2 Supported on Raw Red Clay Disks to Discolour Reactive Red 141. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shi, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y. Applied Clay Science Synthesis and characterization of kaolinite/TiO2 nano-photocatalysts. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 53, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Fang, P.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dai, Y. Effective removal of high-chroma crystal violet over TiO2-based nanosheet by adsorption-photocatalytic degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 204–205, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, O.; Matarangolo, M.; Vaiano, V.; Libralato, G.; Guida, M.; Lofrano, G.; Carotenuto, M. Crystal violet and toxicity removal by adsorption and simultaneous photocatalysis in a continuous flow micro-reactor. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Nazim, M.; Shin, H.S. Rapid photocatalytic degradation of crystal violet dye over ZnO flower nanomaterials. Mater. Lett. 2013, 96, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardikar, H.S.; Bhanvase, B.A.; Rathod, A.P.; Sonawane, S.H. Sonochemical synthesis, characterization and sorption study of Kaolin-Chitosan-TiO2 ternary nanocomposite: Advantage over conventional method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 217, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. A Review on the Factors Affecting the Photocatalytic Degradation of Hazardous Materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. Int. J. 2017, 1, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendi, K.; Bouzidi, N.; Boudraa, R.; Saidani, A.; Manseri, A.; Quesada, D.E.; Hai, T.N.; Bollinger, J.C.; Salvestrini, S.; Kebir, M.; et al. Testing of kaolinite/TiO2 nanocomposites for methylene blue removal: Photodegradation and mechanism. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2025, 22, 1493–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, S.; Zhuang, P.; Jia, D.; Evrendilek, F.; Zhong, S.; Ninomiya, Y.; Yang, Z.; He, Y.; et al. Dynamic, synergistic, and optimal emissions and kinetics of volatiles during co-pyrolysis of soil remediation plants with kaolin/modified kaolin. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Gao, B.; Ok, Y.S.; Dong, L. Integrated adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using carbon-based nanocomposites: A critical review. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibanova, D.; Sleiman, M.; Cervini-Silva, J.; Destaillats, H. Adsorption and photocatalytic oxidation of formaldehyde on a clay-TiO2 composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 211–212, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, S. Kinetic models of sorption: A theoretical analysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 276, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.S.; Mckay, G. Sorption of dye from aqueous solution by peat. Chem. Eng. J. 1998, 70, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarchuk, T.; Bououdina, M.; Al-Najar, B.; Bitra, R.B. Green and ecofriendly materials for the remediation of inorganic and organic pollutants in water. In A New Generation Material Graphene: Applications in Water Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 69–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudraa, R.; Talantikite-Touati, D.; Souici, A.; Djermoune, A.; Saidani, A.; Fendi, K.; Amrane, A.; Bollinger, J.-C.; Tran, H.N.; Hadadi, A.; et al. Optical and photocatalytic studies of TiO2-Bi2O3-CuO supported on natural zeolite for degrading Safranin-O dye in water and wastewater. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 443, 114845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debord, J.; Chu, K.H.; Harel, M.; Salvestrini, S.; Bollinger, J.-C. Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Evolution of a Sleeping Beauty: The Freundlich Isotherm. Langmuir 2023, 8, 3062–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, H.; Stadie, N.P. Langmuir’s Theory of Adsorption: A Centennial Review. Langmuir 2019, 35, 5409–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhemkhem, A.; Rida, K. Improvement adsorption capacity of methylene blue onto modified Tamazert kaolin. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, S.; Deligeer, W.; Asuha, S. Modification of acid-activated kaolinite with TiO2 and its use for the removal of azo dyes. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 114, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, N.; Zhang, H.; Shang, R.; Xing, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, J. Fabrication of ZSM-5 zeolite supported TiO2-NiO heterojunction photocatalyst and research on its photocatalytic performance. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 309, 122895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohong, N.; Baratau, J.T.L.; Wibowo, D.; Mustapa, F.; Zulfan, A.; Maulidiyah, M.; Nurdin, M. Thermal activation and loading of Clay/TiO2/CTAB composite: Physicochemical characterization and adsorption-photodegradation of methyl orange. Adv. Environ. Technol. 2025, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanani, J.; Buazar, F.; Nikpour, Y. Promoted Photocatalytic Activity of Green Titanium Oxide-Clay Nanocomposite Toward Polychlorinated Biphenyl Degradation in Actual Samples. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekena, F.T.; Kuo, D.H. 10 nm sized visible light TiO2 photocatalyst in the presence of MgO for degradation of methylene blue. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 116, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, B.T.T.; Ha, T.L.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Le, H.N.; Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Ha-Thuc, C.N. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of montmorillonite/TiO2 nanocomposites for rhodamine B degradation under UVC irradiation. Clays Clay Miner. 2024, 72, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napruszewska, B.D.; Duraczyńska, D.; Kryściak-Czerwenka, J.; Nowak, P.; Serwicka, E.M. Clay Minerals/TiO2 Composites—Characterization and Application in Photocatalytic Degradation of Water Pollutants. Molecules 2024, 29, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djellabi, R.; Ghorab, M.F. Solar photocatalytic decolourization of Crystal violet using supported TiO2: Effect of some parameters and comparative efficiency. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 53, 3649–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T10 | T7 | T5 | TK10 | TK7 | TK5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area (m2/g) | 12.7 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 33.1 | 33 | 33.9 |

| Pore size (nm) | 16.8 | 19.6 | 19.8 | 18.2 | 17.9 | 17.9 |

| Pore volume (cm3/g) | 0.032 | 0.052 | 0.043 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 |

| PFO Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k2 (g/mg × Min) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k1 (Min−1) |

| T5 | 0.968 | 4.068 | 0.013 | 0.970 | 3.400 | 0.0497 |

| T7 | 0.996 | 4.488 | 0.014 | 0.986 | 3.839 | 0.0534 |

| T10 | 0.994 | 5.508 | 0.010 | 0.982 | 4.663 | 0.0481 |

| TK5 | 0.982 | 8.524 | 0.030 | 0.992 | 7.995 | 0.1353 |

| TK7 | 0.999 | 9.107 | 0.028 | 0.998 | 8.545 | 0.1336 |

| TK10 | 0.999 | 10.028 | 0.024 | 0.965 | 9.330 | 0.136 |

| P25 | 0.990 | 0.317 | 0.053 | 0.981 | 2.090 | 0.0812 |

| PSO Model | PFO Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k2 (g/mg × Min) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k1 (Min−1) |

| T5 | 0.998 | 0.193 | 0.357 | 0.996 | 0.16 | 0.0623 |

| T7 | 0.995 | 0.206 | 0.329 | 0.985 | 0.17 | 0.0618 |

| T10 | 0.984 | 0.242 | 0.418 | 0.997 | 0.208 | 0.0835 |

| TK5 | 0.997 | 0.297 | 0.338 | 0.999 | 0.256 | 0.0823 |

| TK7 | 0.992 | 0.308 | 0.325 | 0.999 | 0.261 | 0.0811 |

| TK10 | 0.997 | 0.319 | 0.314 | 0.994 | 0.173 | 0.0111 |

| P25 | 0.984 | 0.130 | 0.831 | 0.997 | 0.113 | 0.0875 |

| Kaolinite | 0.98 | 0.450 | 0.251 | 0.996 | 0.392 | 0.0894 |

| PSO Model | PFO Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k2 (g/mg × Min) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | k1 (Min−1) |

| T5 | 0.995 | 0.115 | 0.910 | 0.994 | 0.100 | 0.0845 |

| T7 | 0.994 | 0.118 | 0.942 | 0.982 | 0.102 | 0.0880 |

| T10 | 0.991 | 0.131 | 0.977 | 0.996 | 0.115 | 0.0972 |

| TK5 | 0.988 | 0.190 | 0.467 | 0.993 | 0.162 | 0.0754 |

| TK7 | 0.992 | 0.190 | 0.517 | 0.995 | 0.163 | 0.0806 |

| TK10 | 0.997 | 0.201 | 0.656 | 0.998 | 0.178 | 0.0994 |

| P25 | 0.997 | 0.095 | 0.726 | 0.993 | 0.078 | 0.0623 |

| Kaolinite | 0.998 | 0.230 | 0.754 | 0.991 | 0.208 | 0.118 |

| Isotherm | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qm (mg/g) | 64.77 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.014 | |

| R2 | 0.998 | |

| Freundlich | KF (mg/g) | 1.895 |

| nF | 0.673 | |

| R2 | 0.960 |

| Nanocomposite | Organic Pollutant | Catalyst Amount (g/L) | Co (mg/L) | Degradation Rate (%) | Reaction Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay/TiO2/CTAB | methyl orange | 0.5 | 25 | 87.84 | 150 min | [70] |

| Clay/TiO2 | safranin | 3 | 8 | 98.3 | 120 min | [71] |

| TiO2/MgO montmorillonite/TiO2 Laponite/TiO2 TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite | methylene blue rhodamine B humic acid Escherichia coli violet crystal | 2 0.1 1 5 1 1 | 10 10 10 1.3 × 109 20 | 99.7 91.5 92 | 2 h 210 min 120 min 120 min 90 min | [72] [73] [74] |

| TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite | violet crystal | 1 | 20 | 99.3 | 90 min | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fendi, K.; Bouzidi, N.; Boudraa, R.; Saidani, A.; Manseri, A.; Kebir, M.; Bollinger, J.-C.; Al-Farraj, E.S.; Alghamdi, M.A.; Abou El-Reash, Y.G.; et al. TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Hybrid Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Crystal Violet Dye and Toxic Volatile Butyraldehyde. Catalysts 2026, 16, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020160

Fendi K, Bouzidi N, Boudraa R, Saidani A, Manseri A, Kebir M, Bollinger J-C, Al-Farraj ES, Alghamdi MA, Abou El-Reash YG, et al. TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Hybrid Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Crystal Violet Dye and Toxic Volatile Butyraldehyde. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020160

Chicago/Turabian StyleFendi, Karim, Nedjima Bouzidi, Reguia Boudraa, Amira Saidani, Amar Manseri, Mohammed Kebir, Jean-Claude Bollinger, Eida S. Al-Farraj, Mashael A. Alghamdi, Yasmeen G. Abou El-Reash, and et al. 2026. "TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Hybrid Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Crystal Violet Dye and Toxic Volatile Butyraldehyde" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020160

APA StyleFendi, K., Bouzidi, N., Boudraa, R., Saidani, A., Manseri, A., Kebir, M., Bollinger, J.-C., Al-Farraj, E. S., Alghamdi, M. A., Abou El-Reash, Y. G., & Mouni, L. (2026). TiO2–MgO/Kaolinite Hybrid Catalysts: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity for the Degradation of Crystal Violet Dye and Toxic Volatile Butyraldehyde. Catalysts, 16(2), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020160