The Role of Plasma-Emitted Photons in Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Splitting over TiO2 Nanotube-Based Electrodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

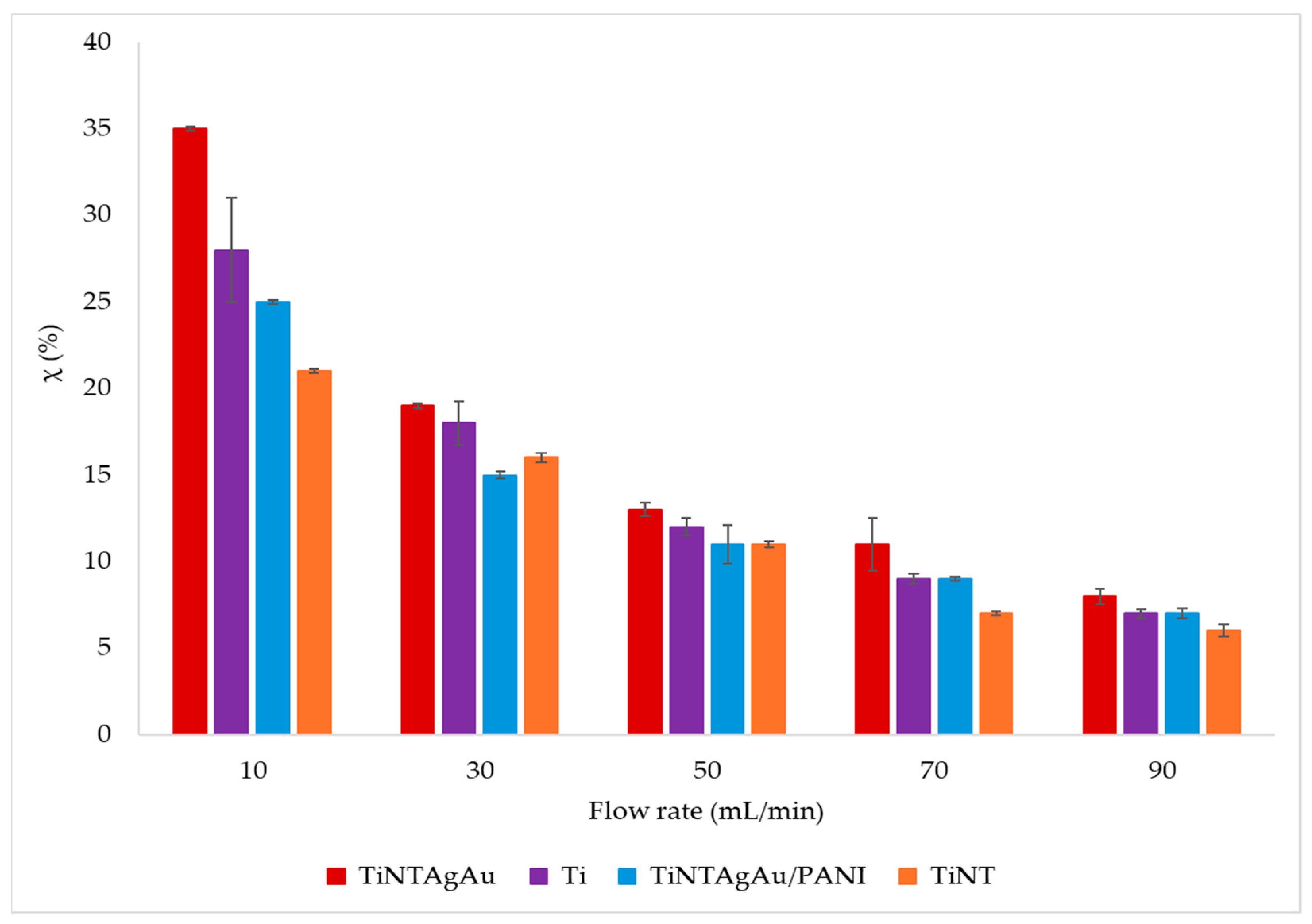

2.1. Role of the Flow Rate and Applied Voltage

2.2. Specific Energy Input (SEI) and Energy Efficiency (η)

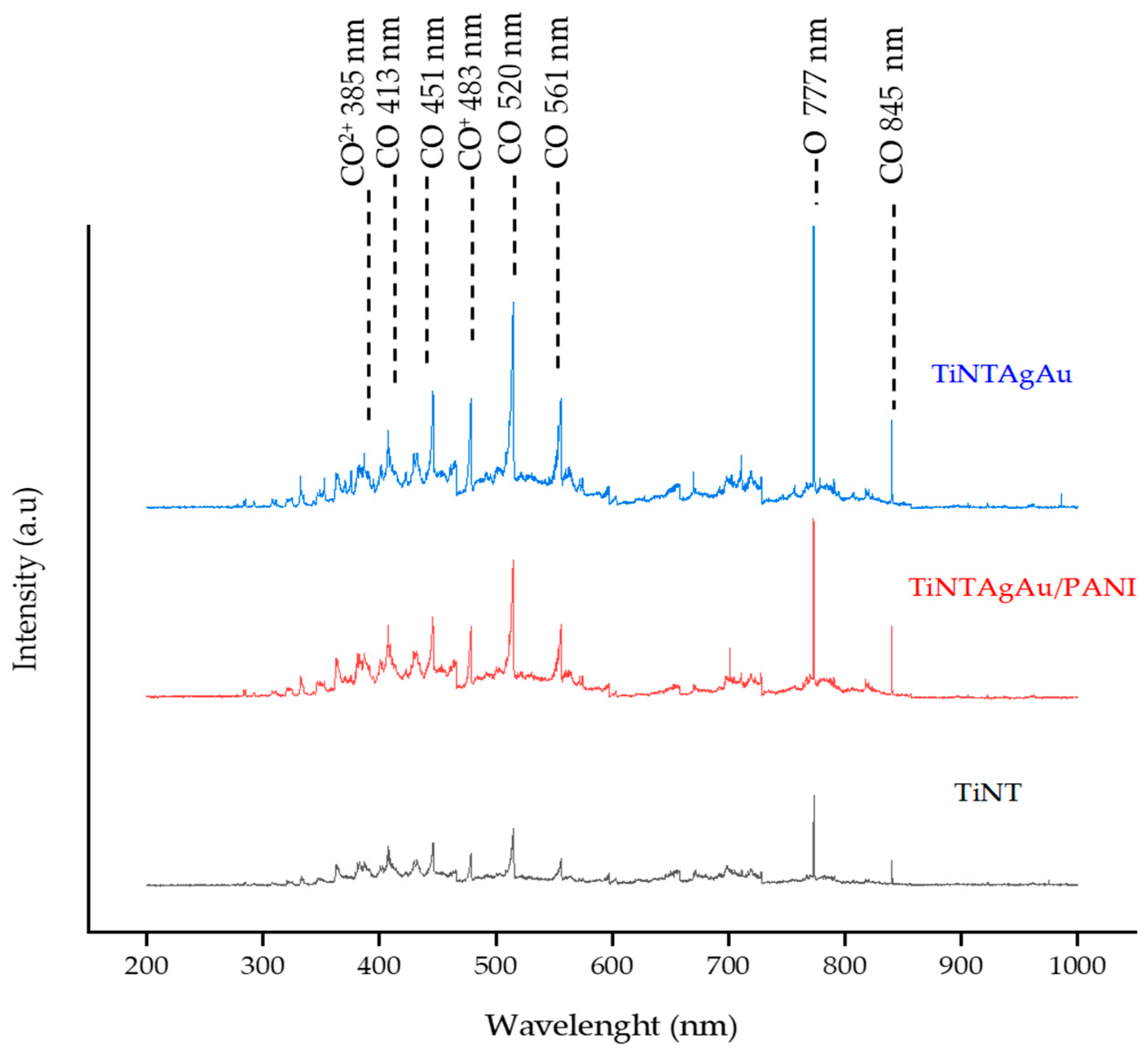

2.3. OES Spectra

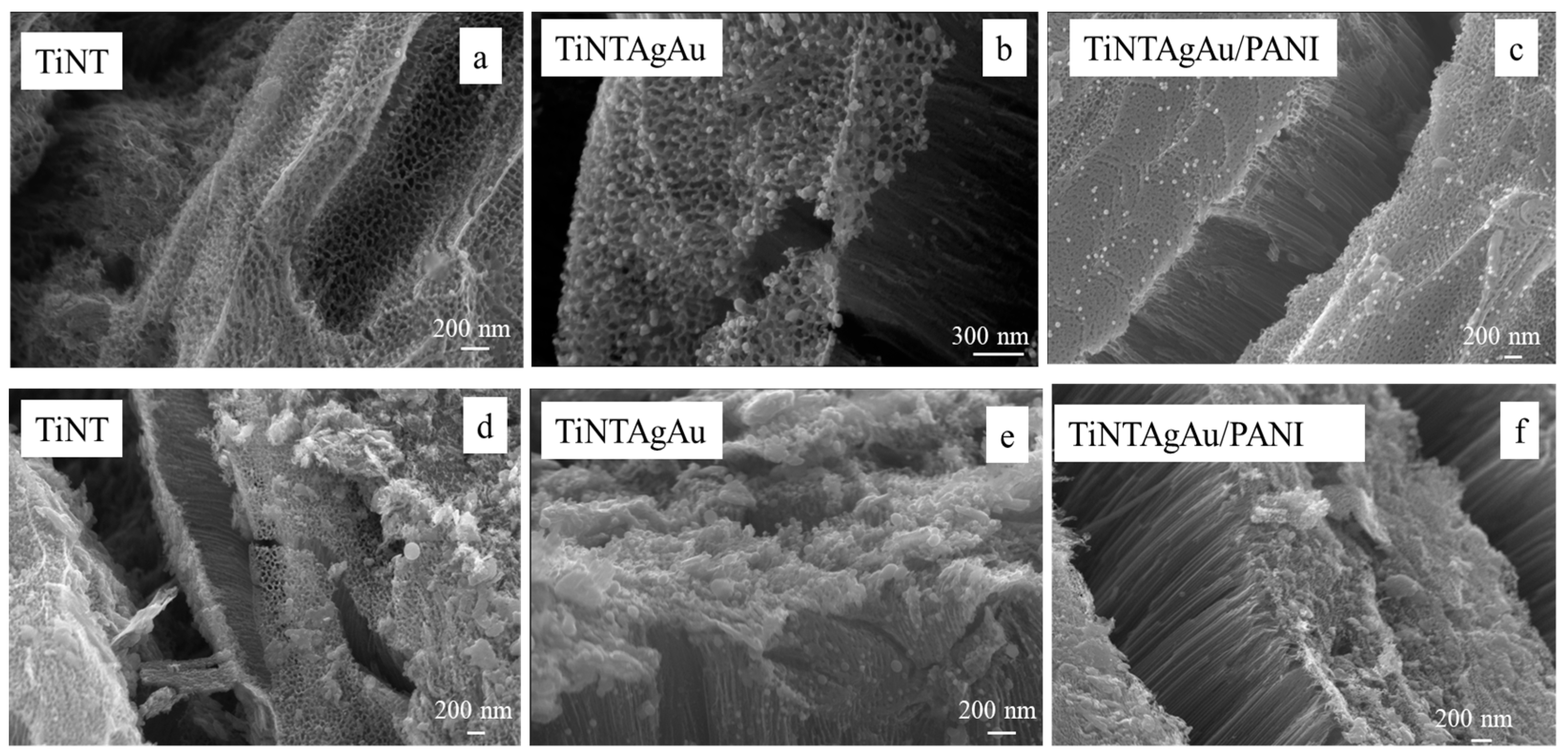

2.4. SEM

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reactor Configuration

4.2. Synthesis of Catalysts Used as Ground Electrode

4.2.1. TiO2 Nanotube Array Synthesis

4.2.2. AuAg Nanoparticles

4.2.3. Polyaniline Coating

4.3. Plasma Performance for CO2 Splitting

4.4. SEM and OES

4.5. UV-Vis and XPS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| pDBD | Planar Dielectric Barrier Discharge |

| SEI | Specific Energy Input |

| NTs | Nanotubes |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| LSPR | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| si-LSPR | self-induced Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| Vpp | Voltage peak to peaks |

| OES | Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

References

- Appolloni, A.; Centi, G.; Yang, N. Promoting carbon circularity for a sustainable and resilience fashion industry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 39, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. The chemical engineering aspects of CO2 capture, combined with its utilisation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2023, 39, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for an electrified chemical production. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, G.; Centi, G.; Perathoner, S.; Lanzafame, P. Green synthesis and sustainable processing routes. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 47, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Centi, G.; Hessel, V.; Rebrov, E. Challenges in unconventional catalysis. Catal. Today 2023, 420, 114180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Centi, G. Plasma Technology for CO2 Conversion: A Personal Perspective on Prospects and Gaps. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Centi, G.; Hessel, V.; Rebrov, E. Perspectives and Emerging Trends in Plasma Catalysis: Facing the Challenge of Chemical Production Electrification. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e202401938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma technology. A novel solution for CO2 conversion? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5805–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Tejada, J.; Escriba-Gelonch, M.; Vertongen, R.; Bogaerts, A.; Hessel, V. CO2 conversion to CO via plasma and electrolysis: A techno-economic and energy cost analysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 5833–5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.C. Plasma Technology: An Emerging Technology for Energy Storage. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A. Plasma technology for the electrification of chemical reactions. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2025, 2, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.; Centi, G.; Perathoner, S.; Genovese, C. CO2 utilisation with plasma technologies. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 46, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, N.; Shang, K.; Mizuno, A.; Wu, Y. Evaluation of discharge uniformity and area in surface dielectric barrier discharge at atmospheric pressure. Vacuum 2016, 123, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollegott, K.; Wirth, P.; Oberste-Beulmann, C.; Awakowicz, P.; Muhler, M. Fundamental Properties and Applications of Dielectric Barrier Discharges in Plasma-Catalytic Processes at Atmospheric Pressure. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2020, 92, 1542–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’T Veer, K.; Van Alphen, S.; Remy, A.; Gorbanev, Y.; De Geyter, N.; Snyders, R.; Reniers, F.; Bogaerts, A. Spatially and temporally non-uniform plasmas: Microdischarges from the perspective of molecules in a packed bed plasma reactor. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 174002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Zhang, Y.R.; Van Laer, K.; Wang, W. Burning questions of plasma catalysis: Answers by modeling. Catal. Today 2019, 337, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Turnhout, J.; Rouwenhorst, K.; Lefferts, L.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma catalysis: What is needed to create synergy? EES Catal. 2025, 3, 669–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. Numerical Simulation of Surface Dielectric Barrier Discharge With Functionally Graded Material. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 874887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogelheide, F.; Offerhaus, B.; Bibinov, N.; Krajinski, P.; Schücke, L.; Schulze, J.; Stapelmann, K.; Awakowicz, P. Characterisation of volume and surface dielectric barrier discharges in N2–O2 mixtures using optical emission spectroscopy. Plasma Process. Polym. 2020, 17, 1900126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloviev, V.R.; Selivonin, I.V.; Moralev, I.A. Breakdown voltage for surface dielectric barrier discharge ignition in atmospheric air. Phys. Plasmas 2017, 24, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.N.; Kim, I.T.; Cho, G. Discharge characteristics and plasma erosion of various dielectric materials in the dielectric barrier discharges. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzec, D.; Freund, F.; Bäuml, C.; Penzkofer, P.; Nettesheim, S. Hybrid Dielectric Barrier Discharge Reactor: Characterization for Ozone Production. Plasma 2024, 7, 585–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allabakshi, S.M.; Srikar, P.S.N.S.R.; Gangwar, R.K.; Maliyekkal, S.M. Feasibility of surface dielectric barrier discharge in wastewater treatment: Spectroscopic modeling, diagnostic, and dye mineralization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 296, 121344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, D.; Wu, Y. Enduring and stable surface dielectric barrier discharge (SDBD) plasma using fluorinated multi-layered polyimide. Polymers 2018, 10, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portugal, S.; Choudhury, B.; Cardenas, D. Advances on aerodynamic actuation induced by surface dielectric barrier discharges. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 923103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, F.P.; Giorgianni, G.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Gallucci, F.; Abate, S. Unlocking the impact of electrode porosity on CO2 splitting efficiency in porous DBD plasma reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pasquale, L.; Tavella, F.; Longo, V.; Favaro, M.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Ampelli, C.; Genovese, C. The Role of Substrate Surface Geometry in the Photo-Electrochemical Behaviour of Supported TiO2 Nanotube Arrays: A Study Using Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). Molecules 2023, 28, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passalacqua, R.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G. Use of modified anodization procedures to prepare advanced TiO2 nanostructured catalytic electrodes and thin film materials. Catal. Today 2015, 251, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.; Mazare, A.; Schmuki, P.; Iglic, A. Influence of anodization parameters on morphology of TiO2 nanostructured surfaces. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2016, 7, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, F.P.; De Luca, F.; Passalacqua, R.; Centi, G.; Giorgianni, G.; Perathoner, S.; Abate, S. Electrocatalytic production of glycolic acid via oxalic acid reduction on titania debris supported on a TiO2 nanotube array. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 68, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramo, F.P.; De Luca, F.; Chiodoni, A.; Centi, G.; Giorgianni, G.; Italiano, C.; Perathoner, S.; Abate, S. Nanostructure-performance relationships in titania-only electrodes for the selective electrocatalytic hydrogenation of oxalic acid. J. Catal. 2024, 429, 115277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, F.; Passalacqua, R.; Abramo, F.P.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Abate, S. g-C3N4 decorated TiO2 nanotube ordered thin films as cathodic electrodes for the selective reduction of oxalic acid. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 84, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.L.C.; de Oliveira, T.G.; Gusmão, S.B.S.; Ferreira, O.P.; Vasconcelos, T.L.; Guerra, Y.; Milani, R.; Peña-Garcia, R.; Viana, B.C. Study of Structural and Optical Properties of Titanate Nanotubes with Erbium under Heat Treatment in Different Atmospheres. Materials 2023, 16, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hedhili, M.N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P. Plasmonic gold nanocrystals coupled with photonic crystal seamlessly on TiO2 nanotube photoelectrodes for efficient visible light photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.; Qiu, S.; Xu, D.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, B. Direct evidence and enhancement of surface plasmon resonance effect on Ag-loaded TiO2 nanotube arrays for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Cao, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, H. LSPR effect enabled Ag-TiO2 nanotube arrays for high sensitivity and selectivity detection of acetone under visible light. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1003, 175533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincho, J.; Mazierski, P.; Klimczuk, T.; Martins, R.C.; Gomes, J.; Zaleska-Medynska, A. TiO2 nanotubes modification by photodeposition with noble metals: Characterization, optimization, photocatalytic activity, and by-products analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, H.-J.; Lin, J.-S.; Yang, J.-L.; Zhang, F.-L.; Lin, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Jin, S.; Li, J.-F. Plasmonic photocatalysis: Mechanism, applications and perspectives. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2023, 42, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavero, C. Plasmon-induced hot-electron generation at nanoparticle/metal-oxide interfaces for photovoltaic and photocatalytic devices. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Wei, W.D. Surface plasmon-mediated photothermal chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 20735–20749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Yoon, S. Effect of Nanoparticle Size on Plasmon-Driven Reaction Efficiency. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 4163–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, M.S.; Wang, J.; Johnston-Peck, A.C.; Oldenburg, A.L.; Tracy, J.B. Synthesis of Au(core)/Ag(shell) nanoparticles and their conversion to AuAg alloy nanoparticles. Small 2011, 7, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbruggen, S.W.; Keulemans, M.; Filippousi, M.; Flahaut, D.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Lacombe, S.; Martens, J.A.; Lenaerts, S. Plasmonic gold-silver alloy on TiO2 photocatalysts with tunable visible light activity. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 156–157, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.; De Pasquale, L.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Genovese, C. Synergistic effects of light and plasma catalysis on Au-modified TiO2 nanotube arrays for enhanced non-oxidative coupling of methane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 3725–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyts, E.C.; Ostrikov, K.; Sunkara, M.K.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma Catalysis: Synergistic Effects at the Nanoscale. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 13408–13446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, M.; Wang, X.; Chong, B.; Ou, H.; Lin, B.; Yang, G. Efficient reduction of CO2 to C2 hydrocarbons by tandem nonthermal plasma and photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 342, 123423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoder, T.; Prokop, D.; Bajon, C.; Dap, S.; Loffhagen, D.; Becker, M.M.; Navrátil, Z.; Naudé, N. Barrier discharges in CO2—Optical emission spectra analysis and E/N determination from intensity ratio. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2025, 34, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A. Microplasma emission spectroscopy of stable isotope ratios in carbon dioxide. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2022, 31, 055009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunda, D.; Li, S.; Cherkasov, N.; Rishard, M.Z.M.; Chaffee, A.L.; Rebrov, E.V. Effect of temperature on the CO2 splitting rate in a DBD microreactor. React. Chem. Eng. 2023, 8, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Huang, Q.; Devid, E.J.; Schuler, E.; Shiju, N.R.; Rothenberg, G.; van Rooij, G.; Yang, R.; Liu, K.; Kleyn, A.W. Tuning of conversion and optical emission by electron temperature in an inductively coupled CO2 plasma. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 19338–19347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, H.; Khani, M.; Rad, S.A.R.; Shokri, B. CO2 conversion in a dielectric barrier discharge plasma by argon dilution over MgO/HKUST-1 catalyst using response surface methodology. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindon, M.A.; Scime, E.E. CO2 dissociation using the Versatile atmospheric dielectric barrier discharge experiment (VADER). Front. Phys. 2014, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A.; Berglund, M. Microplasma emission spectroscopy of carbon dioxide using the carbon monoxide Ångström system. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 063301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Van Laer, K.; Neyts, E.C.; Bogaerts, A. Can plasma be formed in catalyst pores? A modeling investigation. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 185, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Neyts, E.C.; Bogaerts, A. Enhancement of plasma generation in catalyst pores with different shapes. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.R.; Bogaerts, A. Formation of microdischarges inside a mesoporous catalyst in dielectric barrier discharge plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2017, 26, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.Y.; Song, H.C.; Gwag, E.H.; Nedrygailov, I.I.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.J.; Doh, W.H.; Park, J.Y. Plasmonic hot carrier-driven oxygen evolution reaction on Au nanoparticles/TiO2 nanotube arrays. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 22180–22188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, H.; Han, H.; Fu, Y.; Ma, C.; Yu, Z.; Dong, X. Black TiO2 nanotube arrays fabricated by electrochemical self-doping and their photoelectrochemical performance. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 18992–19000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.K.; Huang, W.; El-Sayed, M.A. On the universal scaling behavior of the distance decay of plasmon coupling in metal nanoparticle pairs: A plasmon ruler equation. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 2080–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Rebrov, E.V. Microreactors for gold nanoparticles synthesis: From faraday to flow. Processes 2014, 2, 466–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuithschick, M.; Birnbaum, A.; Witte, S.; Sztucki, M.; Vainio, U.; Pinna, N.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F.; Kraehnert, R.; Polte, J. Turkevich in New Robes: Key Questions Answered for the Most Common Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 7052–7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaerts, N.; Vanrompay, H.; Nuti, S.; Lenaerts, S.; Bals, S.; Verbruggen, S.W. Unraveling Structural Information of Turkevich Synthesized Plasmonic Gold–Silver Bimetallic Nanoparticles. Small 2019, 15, 1902791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaraju, D.; Kutiang, F.D.A.; Lim, Y.C.; Goh, P.S. Recent progress of Ag/TiO2 photocatalyst for wastewater treatment: Doping, co-doping, and green materials functionalization. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 27, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoeckx, R.; Zeng, Y.X.; Tu, X.; Bogaerts, A. Plasma-based dry reforming: Improving the conversion and energy efficiency in a dielectric barrier discharge. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 29799–29808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Gallon, H.J.; Twigg, M.V.; Gorry, P.A.; Whitehead, J.C. Dry reforming of methane over a Ni/Al2O3 catalyst in a coaxial dielectric barrier discharge reactor. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2011, 44, 274007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, A.; Dufour, T.; Arnoult, G.; De Keyzer, P.; Bogaerts, A.; Reniers, F. CO2-CH4 conversion and syngas formation at atmospheric pressure using a multi-electrode dielectric barrier discharge. J. CO2 Util. 2015, 9, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Tan, L.H.; Yang, M.; Pan, M.; Lv, Y.; Tang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H. Highly controlled core/shell structures: Tunable conductive polymer shells on gold nanoparticles and nanochains. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 3286–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Ahmad, G.; Najeeb, J.; Wu, W.; Irfan, A.; Azam, M.; Nisar, J.; Farooqi, Z.H. Stabilization of silver nanoparticles in crosslinked polymer colloids through chelation for catalytic degradation of p-nitroaniline in aqueous medium. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 763, 138263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundwal, A.; Kumar, H.; Binoj, B.J.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, G.; Kumari, R.; Dhayal, A.; Yadav, A.; Singh, D.; Kumar, P. Developments in conducting polymer-, metal oxide-, and carbon nanotube-based composite electrode materials for supercapacitors: A review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9406–9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Campbell, L.; Te, P. Polyaniline-Coated Surface-Modified Ag/PANI Nanostructures for Antibacterial and Colorimetric Melamine Sensing in Milk Samples. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24010–24015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Kumar, T. Ag/Cu doped polyaniline hybrid nanocomposite-based novel gas sensor for enhanced ammonia gas sensing performance at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25093–25107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou-Fermeli, N.; Lagopati, N.; Gatou, M.A.; Pavlatou, E.A. Biocompatible PANI-Encapsulated Chemically Modified Nano-TiO2 Particles for Visible-Light Photocatalytic Applications. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranka, P.; Sethi, V.; Contractor, A.Q. Characterizing the oxidation level of polyaniline (PANI) at the interface of PANI/TiO2 nanoparticles under white light illumination. Thin Solid Films 2016, 615, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wan, M. Polyaniline/TiO2 composite nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 6748–6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourali, N.; Lai, K.; Gregory, J.; Gong, Y.; Hessel, V.; Rebrov, E.V. Study of plasma parameters and gas heating in the voltage range of nondischarge to full-discharge in a methane-fed dielectric barrier discharge. Plasma Process. Polym. 2023, 20, 2200086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; Song, Y.; Zheng, R.; Chen, L.; Su, B. Hot Electrons Induced by Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance in Ag/g-C3N4 Schottky Junction for Photothermal Catalytic CO2 Reduction. Polymers 2024, 16, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Z. Plasmonic-assisted Electrocatalysis for CO2 Reduction Reaction. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202300805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Anodization & Calcination | PANI Coating | Au–Ag Deposition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | — | — | — |

| TiNT | 50 V, 1 h → Calcination 450 °C, 3 h | — | — |

| TiNTAgAu | 50 V, 1 h → Calcination 450 °C, 3 h | — | Photodeposition (Turkevich-adapted method) |

| TiNTAgAu/PANI | 50 V, 1 h → Calcination 450 °C, 3 h | In situ polymerization (~14 nm over Au–Ag NPs) | Photodeposition (Turkevich-adapted method) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Demoro, P.; Pourali, N.; Abramo, F.P.; Vantomme, C.; Rebrov, E.; Centi, G.; Perathoner, S.; Verbruggen, S.; Bogaerts, A.; Abate, S. The Role of Plasma-Emitted Photons in Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Splitting over TiO2 Nanotube-Based Electrodes. Catalysts 2026, 16, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020137

Demoro P, Pourali N, Abramo FP, Vantomme C, Rebrov E, Centi G, Perathoner S, Verbruggen S, Bogaerts A, Abate S. The Role of Plasma-Emitted Photons in Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Splitting over TiO2 Nanotube-Based Electrodes. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020137

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemoro, Palmarita, Nima Pourali, Francesco Pio Abramo, Christine Vantomme, Evgeny Rebrov, Gabriele Centi, Siglinda Perathoner, Sammy Verbruggen, Annemie Bogaerts, and Salvatore Abate. 2026. "The Role of Plasma-Emitted Photons in Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Splitting over TiO2 Nanotube-Based Electrodes" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020137

APA StyleDemoro, P., Pourali, N., Abramo, F. P., Vantomme, C., Rebrov, E., Centi, G., Perathoner, S., Verbruggen, S., Bogaerts, A., & Abate, S. (2026). The Role of Plasma-Emitted Photons in Plasma-Catalytic CO2 Splitting over TiO2 Nanotube-Based Electrodes. Catalysts, 16(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020137