ZSM-5 Nanocatalyst from Rice Husk: Synthesis, DFT Analysis, and Au/Pt Modification for Isopropanol Conversion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

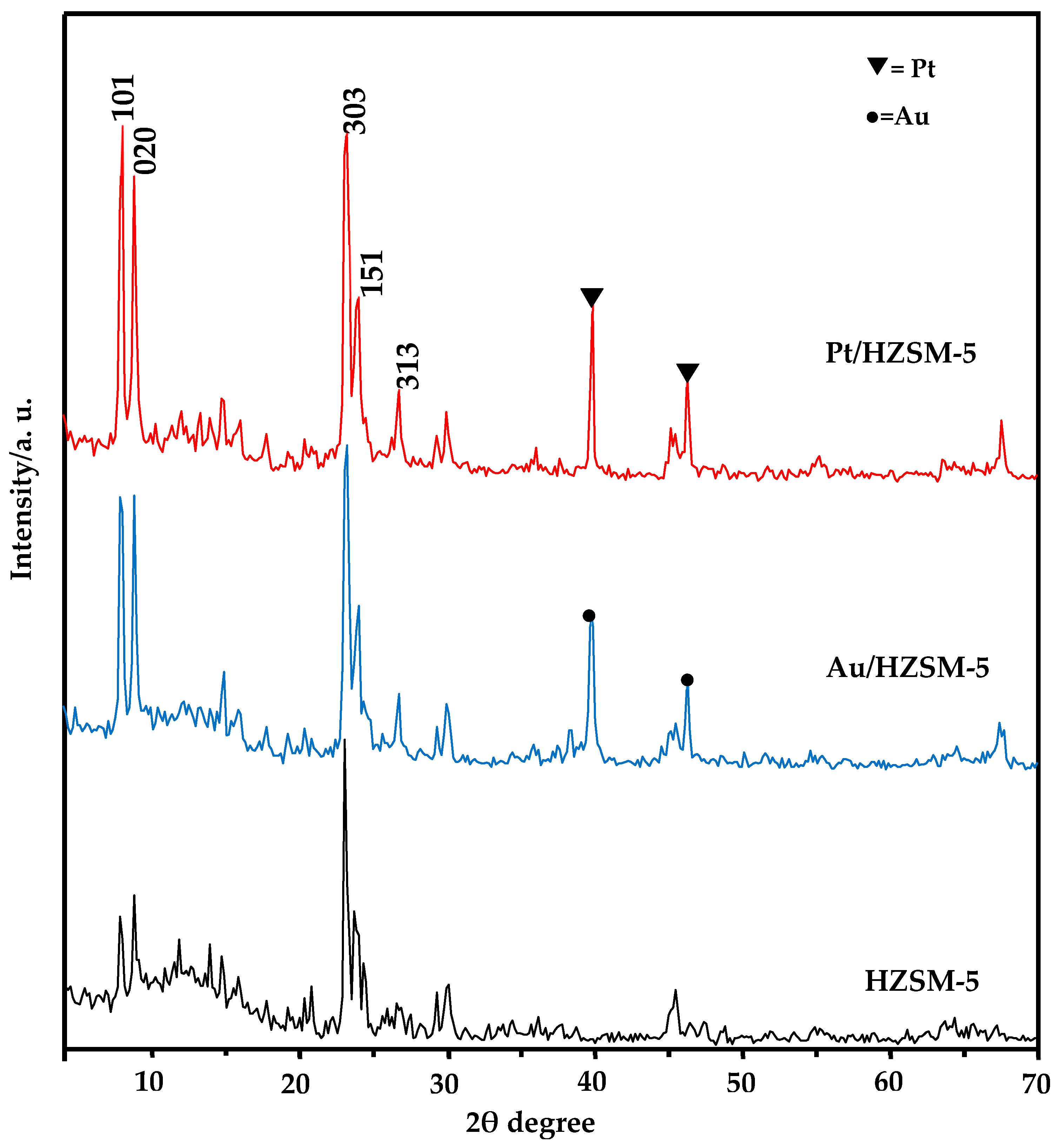

2.1. XRD Investigation

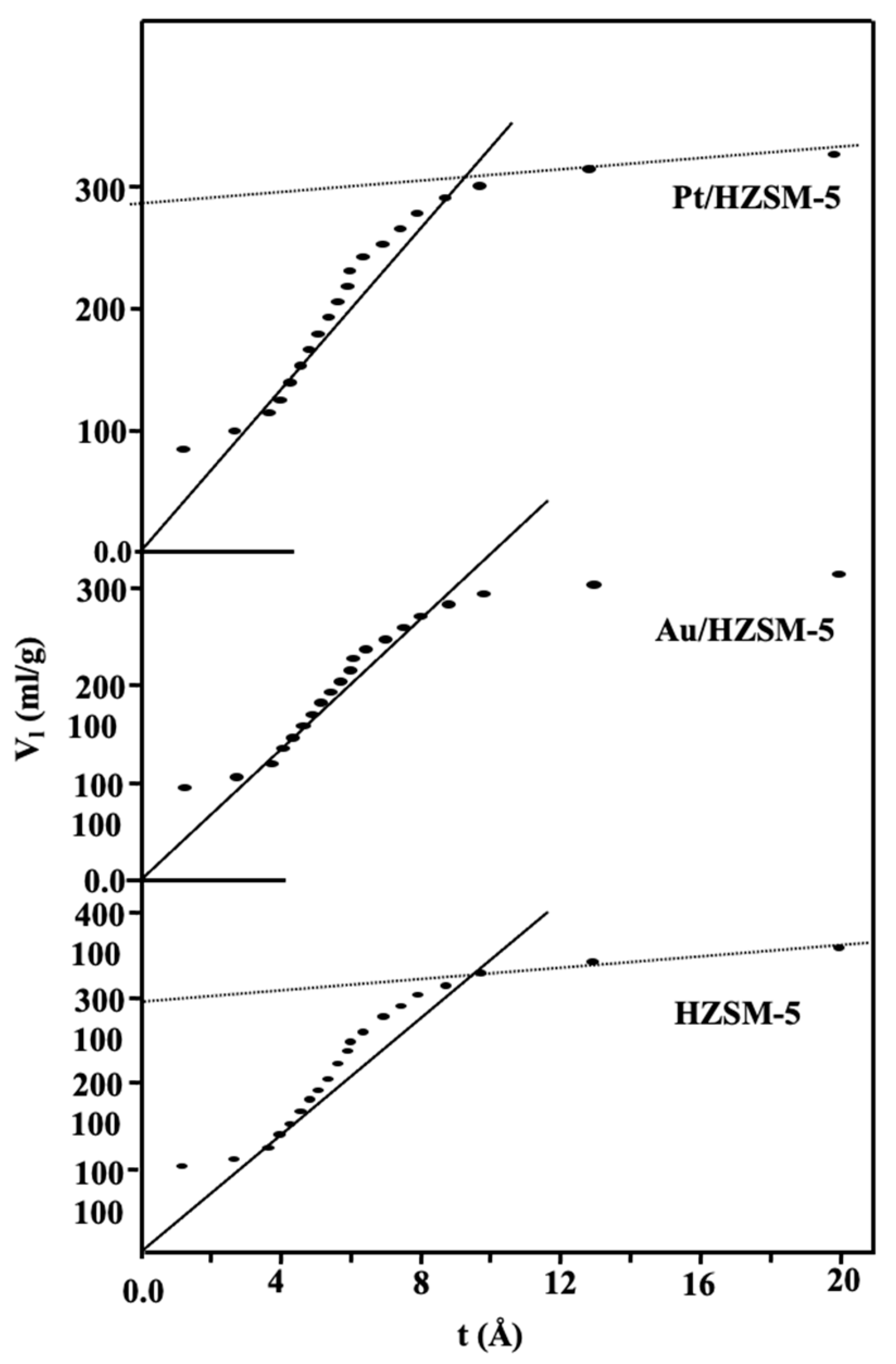

2.2. Surface Texture

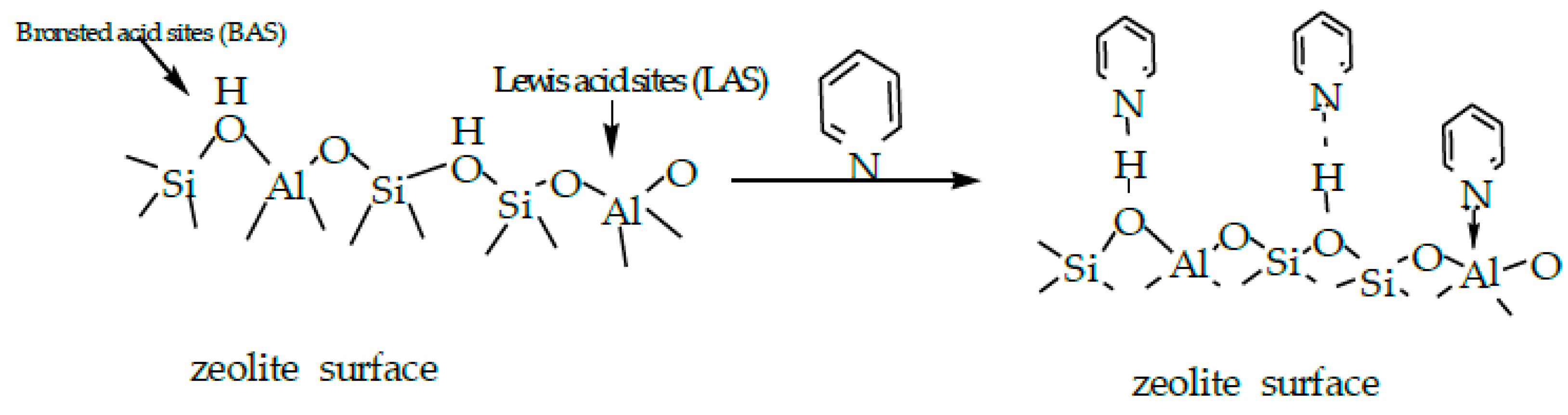

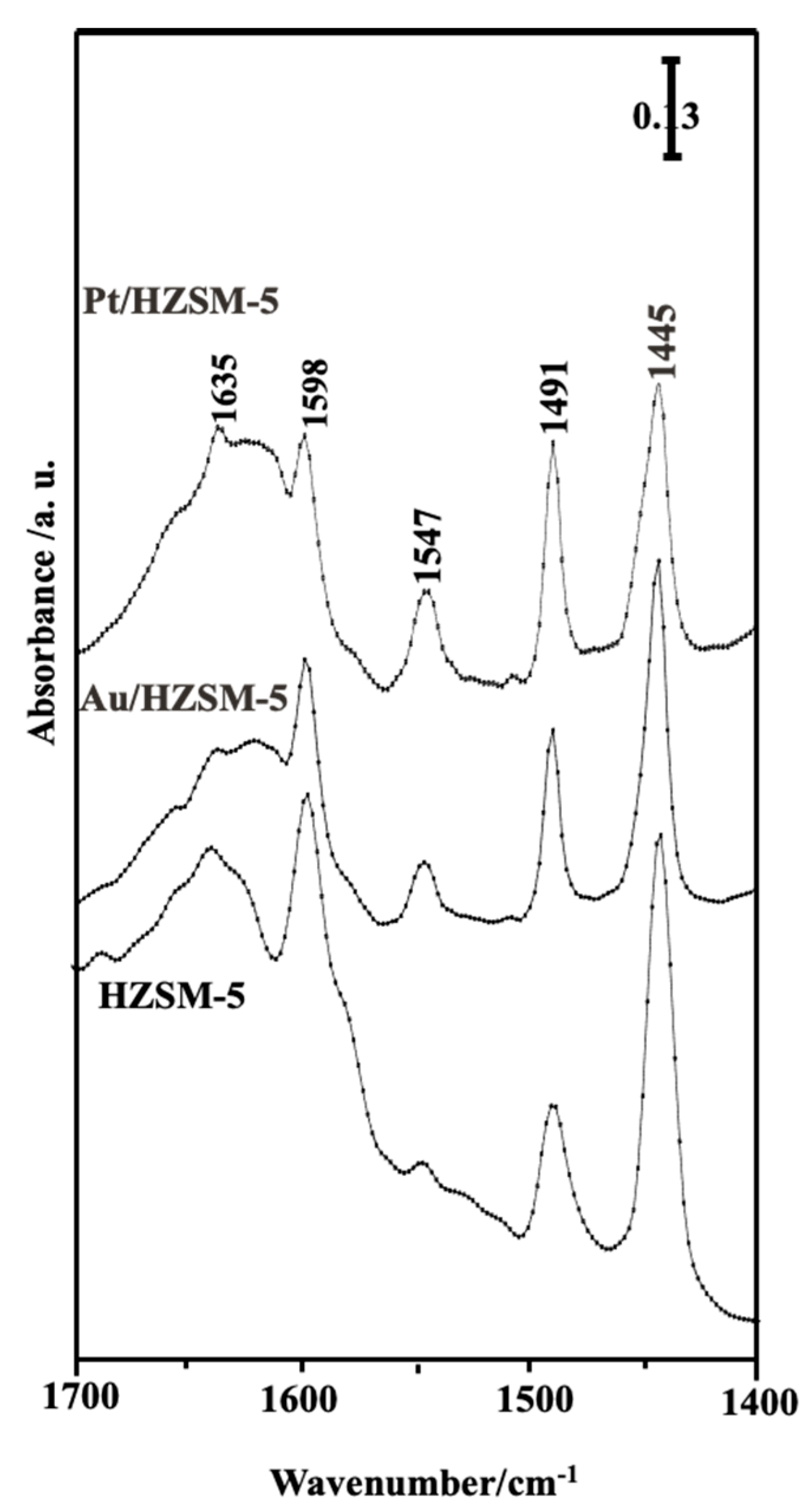

2.3. In Situ FT-IR Spectra of Pyridine Adsorption

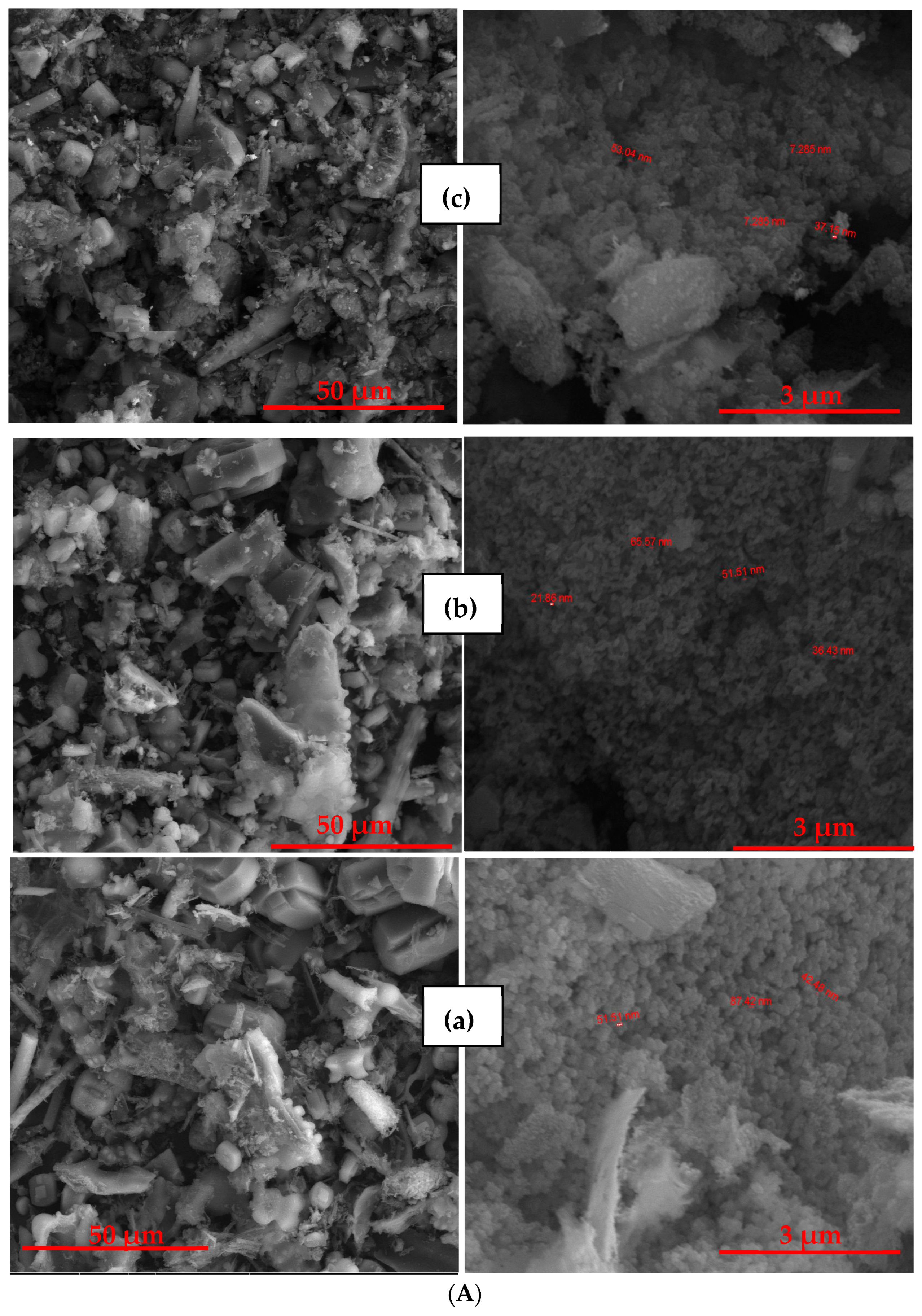

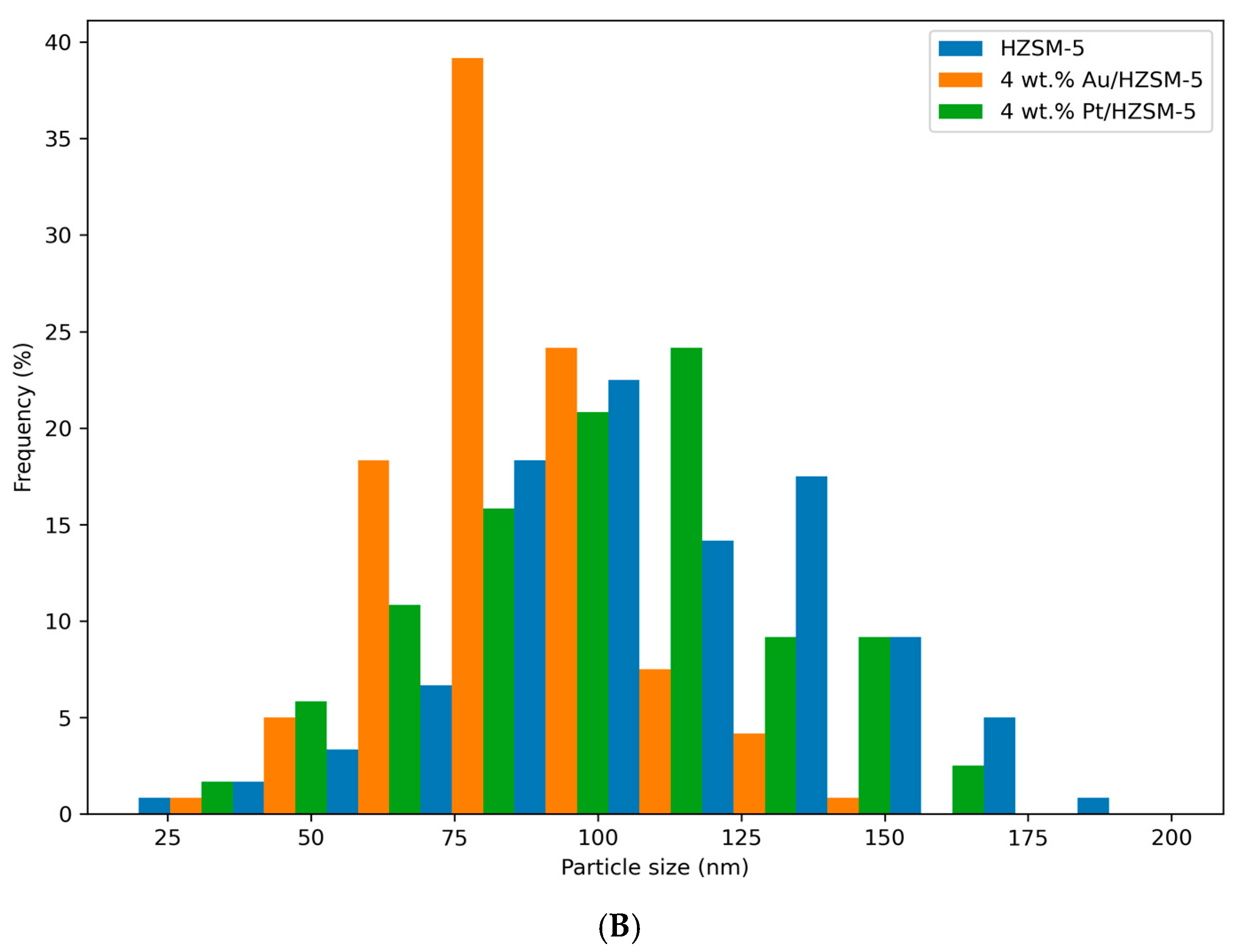

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

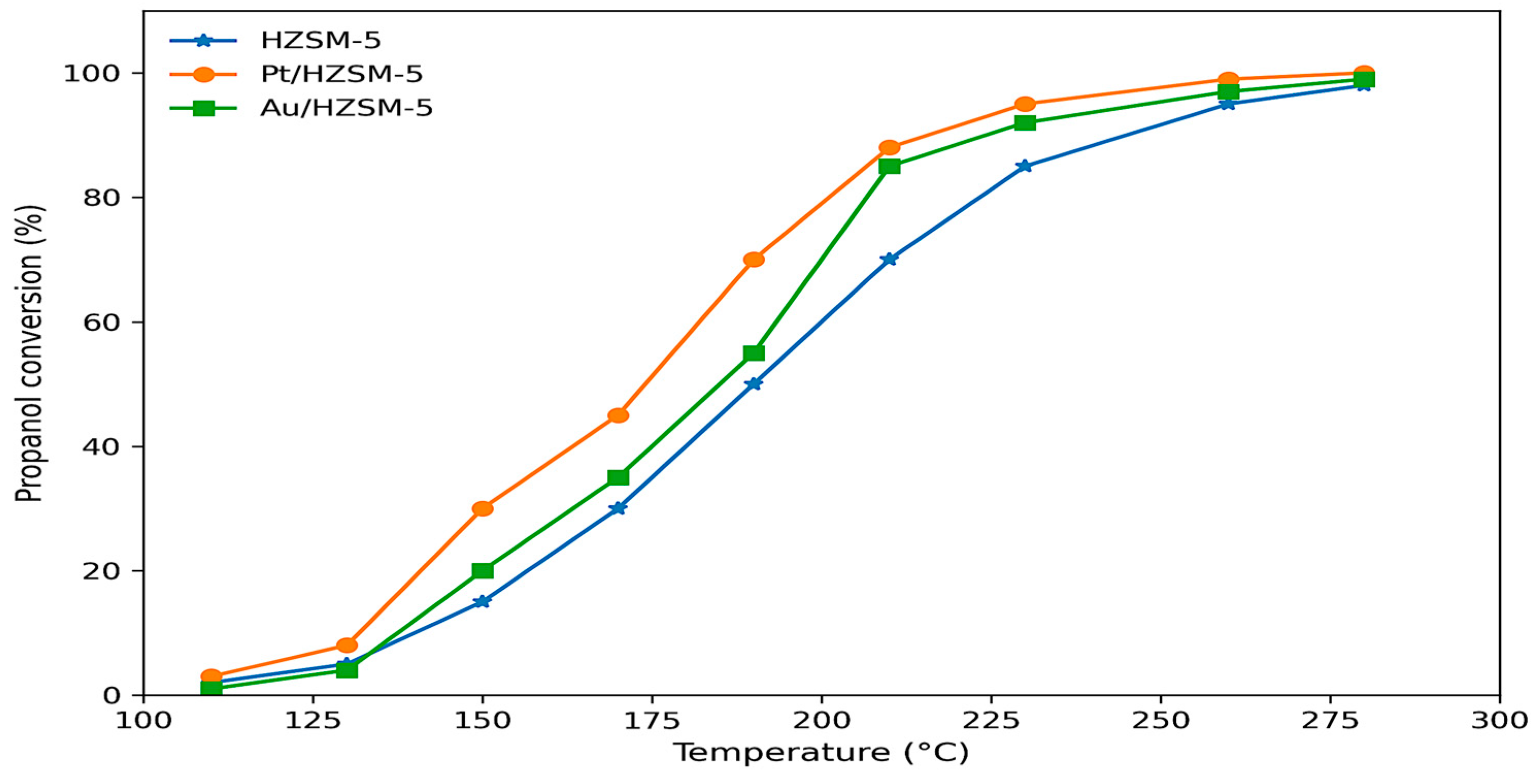

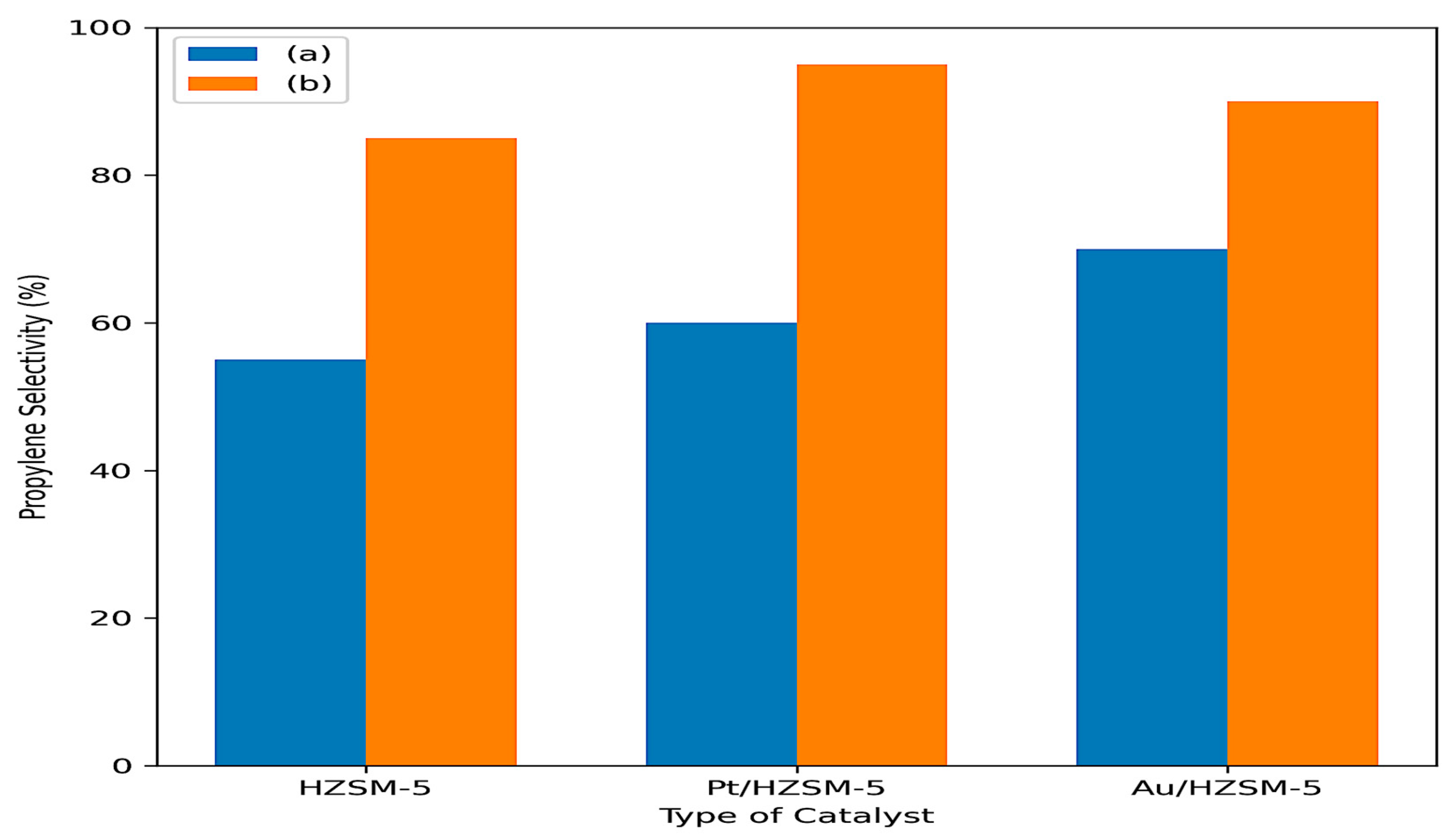

2.5. Catalytic Properties of Isopropanol

2.5.1. Catalytic Conversion

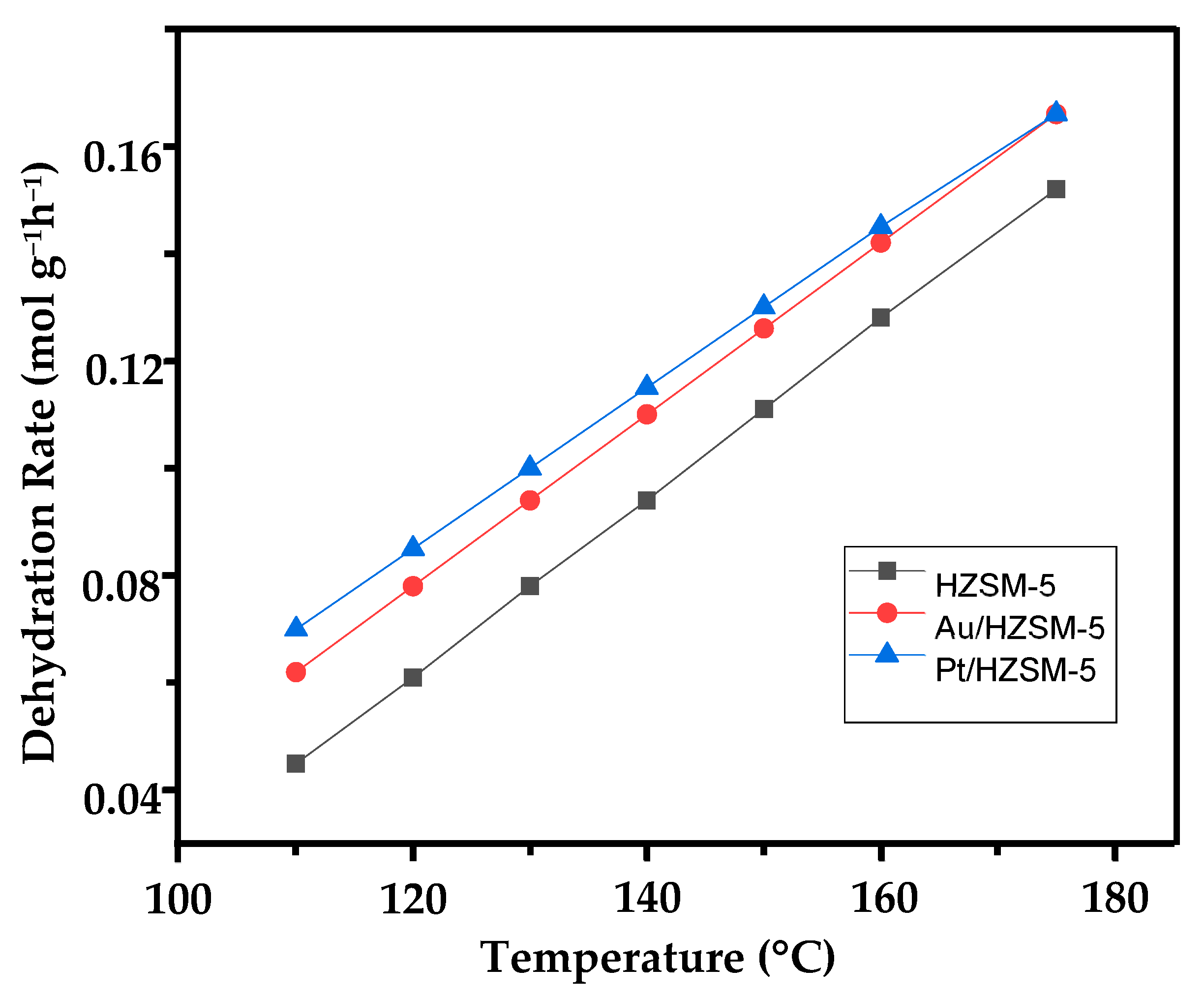

2.5.2. Activation Energy

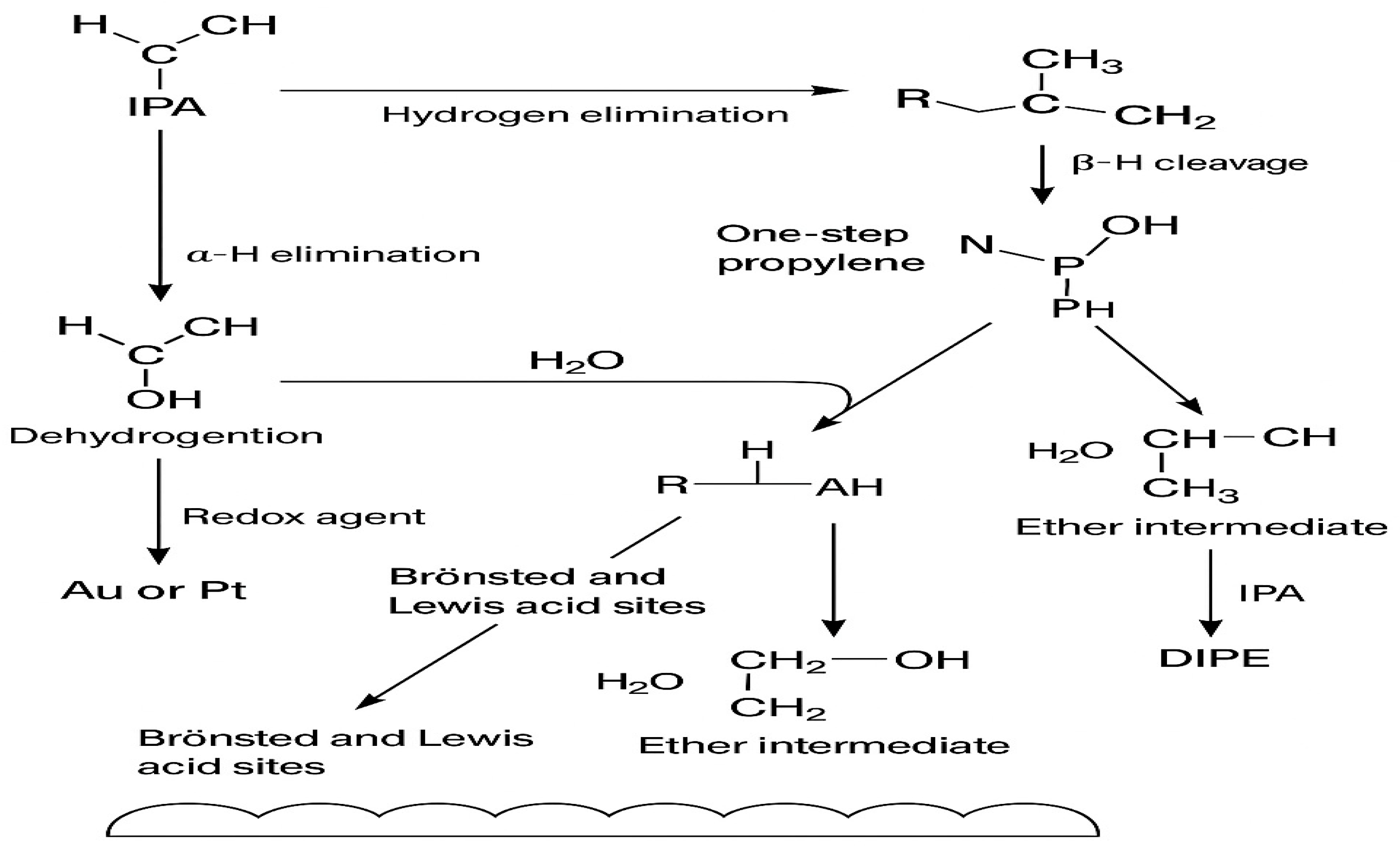

2.6. Reaction Mechanism

2.7. Estimation of the Reaction Rate Constants and Turnover Frequencies (TOFs)

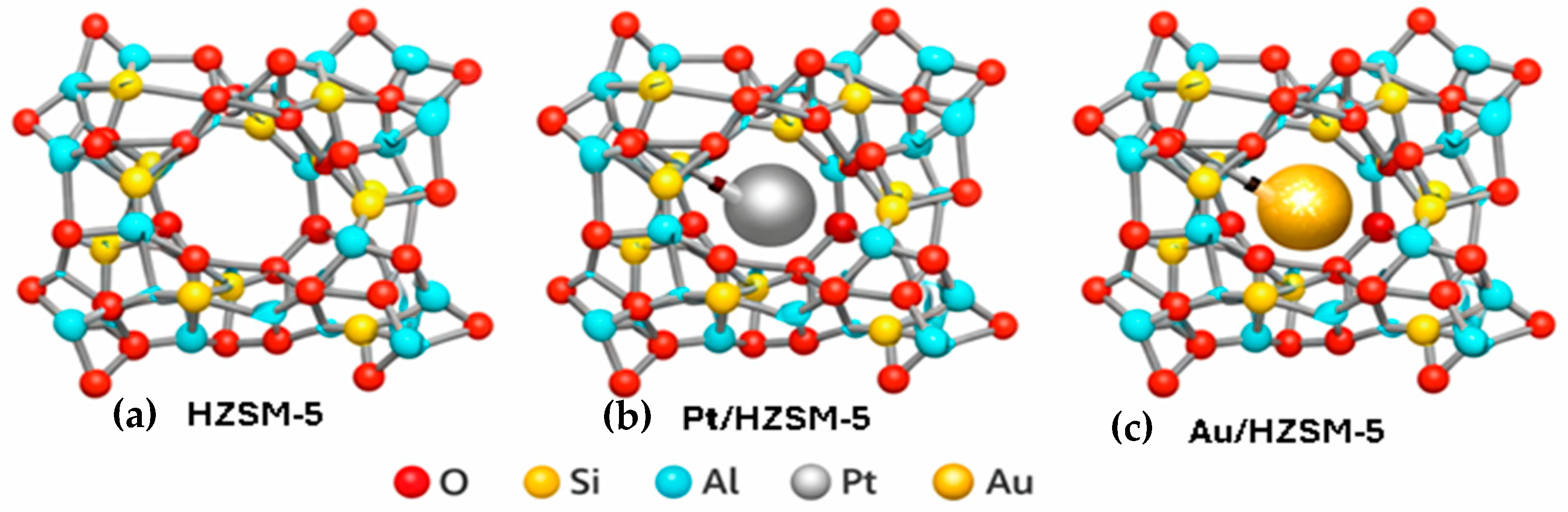

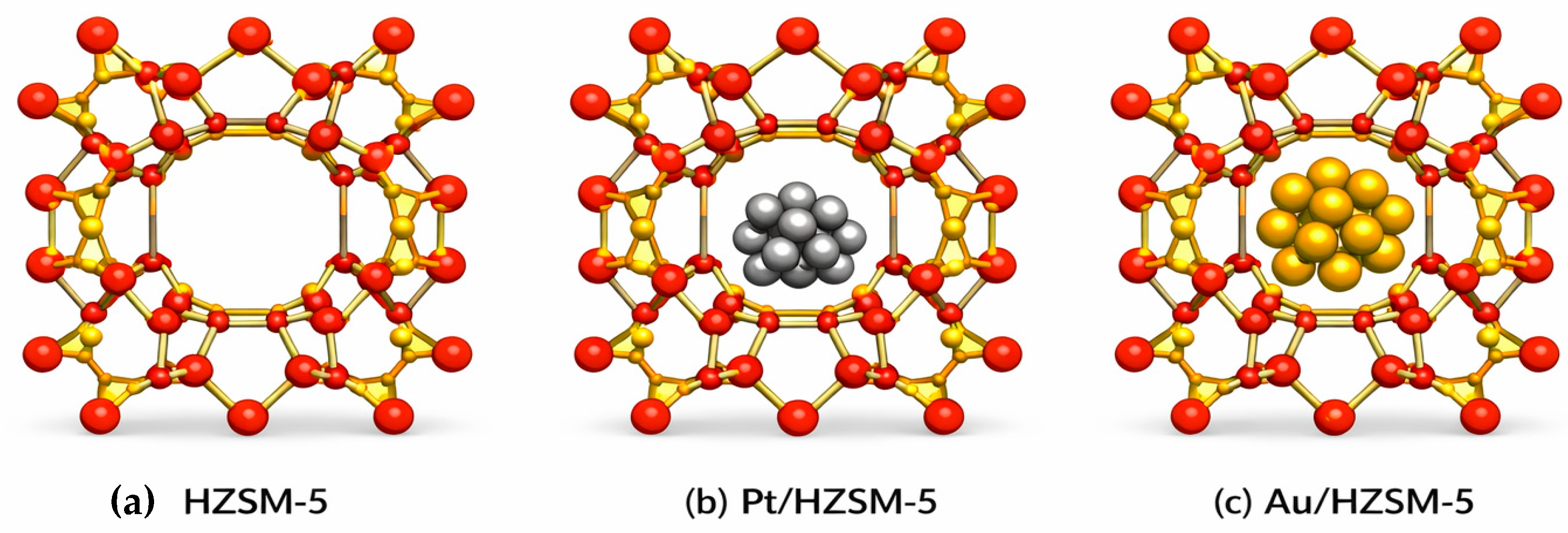

2.8. Computational Study

2.8.1. Energetical Studies

2.8.2. Template Interactions

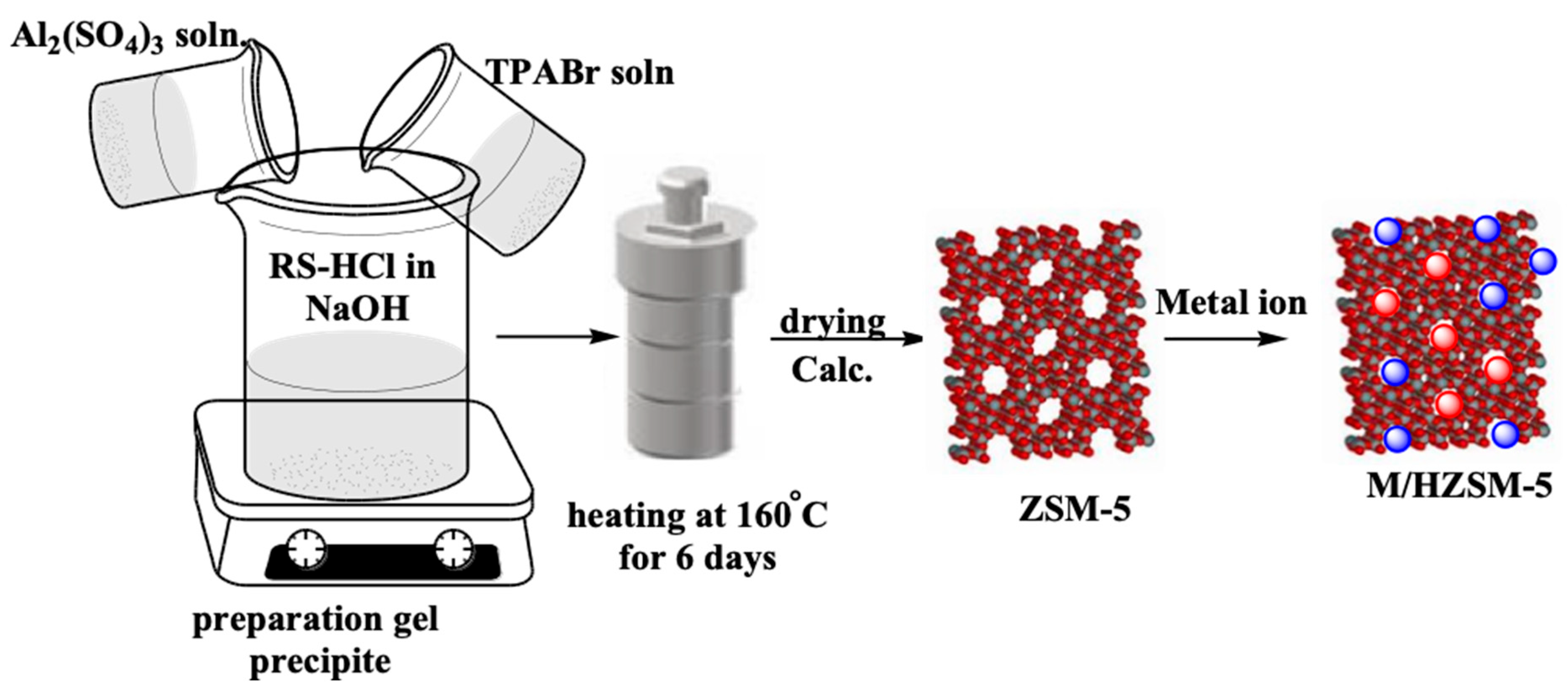

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

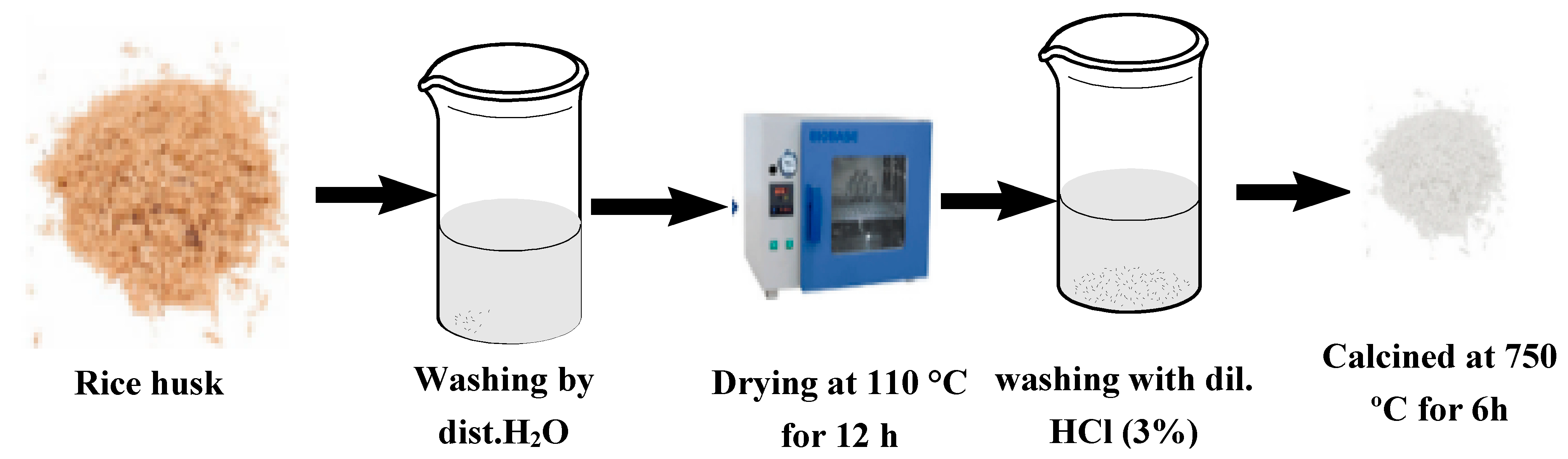

3.1.1. Silica Extraction from Rice Straw

3.1.2. Hydrothermal Preparation of ZSM-5

3.1.3. The HZSM-5 Preparation

3.1.4. The Au/HZSM-5 and Pt/HZSM-5 Preparation Method

3.2. Characterization Techniques

3.3. Models and Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phung, T.K.; Pham, T.L.M.; Vu, K.B.; Busca, G. (Bio)Propylene production processes: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murat, M.; Tišler, Z.; Šimek, J.; Hidalgo-Herrador, J.M. Highly active catalysts for the dehydration of isopropanol. Catalysts 2020, 10, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, L.; Bosman, C.E.; Louw, J.; Petersen, A.; Ghods, N.N.; Görgens, J.F. Biobased propylene and acrylonitrile production in a sugarcane biorefinery: Identification of preferred production routes via techno-economic and environmental assessments. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 190, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, J.-L.; Postole, G.; Silvester, L.; Auroux, A. Catalytic Dehydration of Isopropanol to Propylene. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, K.; Zhuang, L.; Yang, P.; Nie, H. Structure-performance relationship between zeolites properties and hydrocracking performance of tetralin over NiMo/Al2O3-Y catalysts: A machine-learning-assisted study. Fuel 2025, 390, 134652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallette, A.J.; Seo, S.; Rimer, J.D. Synthesis strategies and design principles for nanosized and hierarchical zeolites. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-H.; Sun, M.-H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Xie, Z.; Su, B.-L. Hierarchically structured zeolites: From design to application. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11194–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ning, W.; Wang, Q.; Wei, X.; Li, X.; Pan, M. Hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite using amino acid as template: Avoiding phase separation and fabricating an ultra-small mesoporous structure. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 355, 112578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Pan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Ma, J.; Shan, W.; He, H. Adsorptive removal of toluene and dichloromethane from humid exhaust on MFI, BEA and FAU zeolites: An experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124986–124996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Peyrovi, M.H.; Parsafard, N. n-Heptane isomerization activities of Pt catalyst supported on micro/mesoporous composites. BMC Chem. 2021, 15, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, N.; Yan, X.; Fan, B.; Li, R. Influence of Acidity of Mesoporous ZSM-5-Supported Pt on Naphthalene Hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhao, R.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q. Highly dispersed platinum clusters anchored on hollow ZSM-5 zeolite for deep hydrogenation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Fuel 2022, 326, 125021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, N.; Comparot, J.-D.; Le Valant, A.; Pinard, L. In situ FTIR spectroscopy to unravel the bifunctional nature of aromatics hydrogenation synergy on zeolite/metal catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bahy, Z.M.; Mohamed, M.M.; Zidan, F.I.; Thabet, M.S. Photo-degradation of acid green dye over Co–ZSM-5 catalysts prepared by incipient wetness impregnation technique. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Kokotailo, G.T.; Gorte, R.J.; Farneth, W.E. Adsorption and reaction of 2-propen-1-ol in H-ZSM-5. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 2063–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, M.C.; Gorte, R.J. Adsorption of 2-propanol and propene on H-ZSM-5: Evidence for stable carbenium ion formation. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.; Abdrassilova, A.; Ávila, M.; Alonso-Doncel, M.; Cueto, J.; Gómez-Pozuelo, G.; Briones, L.; Botas, J.; Serrano, D.; Peral, A.; et al. Tailoring the preparation of USY zeolite with uniform mesoporosity for improved catalytic activity in phenol/isopropanol alkylation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2025, 392, 113629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.; Zhu, M.; Shao, Y.; Shao, S.; Wu, Q.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Kita, H. Preparation and catalytic performance of the supported TS-1 zeolites for IPA oxidation. J. Solid State Chem. 2025, 349, 125449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airi, A.; Signorile, M.; Bonino, F.; Quagliotto, P.; Bordiga, S.; Martens, J.A.; Crocellà, V. Insights on a Hierarchical MFI Zeolite: A Combined Spectroscopic and Catalytic Approach for Exploring the Multilevel Porous System Down to the Active Sites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 49114–49127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, M.; Zhang, R.; Song, X.; Li, W.; Jiang, J.; Xie, J.; Li, X.; Cai, L.; Sun, X.; et al. Spatial isolation effect improves the acidity and redox capacity of ZSM-5 encapsulating Pt catalyst to achieve efficient toluene oxidation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 694, 134173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, C.; Wang, X.; Xing, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M. Low-content Pt loading on a post-treatment-free zeolite for efficient catalytic combustion of toluene. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 363, 112832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, Q.; Yang, T.; Bao, Y.C.; Liu, J. Preparation and characterization of ZSM-5 molecular sieve using coal gangue as a raw material via solvent-free method: Adsorption performance tests for heavy metal ions and methylene blue. Chemosphere 2023, 341, 139741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshoaibi, A.; Islam, S. Heating influence on atomic site structural changes of Mesoporous Au supported Anatase nanocomposite for photocatalytic progression. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2022, 104, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnejad, S.; Provis, J.L.; van Deventer, J.S. Reduction of gold(III) chloride to gold(0) on silicate surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 389, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinga, J.; Chena, J.; Ruic, Z.; Liua, Y.; Lva, P.; Liua, X.; Lib, H.; Ji, H. Synchronous pore structure and surface hydroxyl groups amelioration as an efficient route for promoting HCHO oxidation over Pt/ZSM-5. Catal. Today 2018, 316, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Peffer, L.A.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Pore size determination in modified micro- and mesoporous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size dis-tribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Tian, Y.; Gong, S.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Z.; Xia, Y.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, C. Effects of Crystallite Sizes of Pt/HZSM-5 Zeolite Catalysts on the Hydrodeoxygenation of Guaiacol. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zholobenko, V.; Freitas, C.; Jendrlin, M.; Bazin, P.; Travert, A.; Thibault-Starzyk, F. Probing the acid sites of zeolites with pyridine: Quantitative AGIR measurements of the molar absorption coefficients. J. Catal. 2020, 385, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Yan, M.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y.; Xu, D.; Cao, J.-P. Synergy between Lewis acidic metal sites and silanols in Sn- and Ti-Beta for conversion of butenes by DRIFTS. J. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 1009, 123067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, W.; Ma, X.; Lai, H.; Zhang, X. Understanding contributions of zeolite surface hydroxyl groups over Au/USY in selective oxidation of aromatic alcohols. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 151036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, N.X.P.; Ngo, T.P.; Tran, V.T.; Luong, N.T.; Le, P.N.; Cao, V.C. Enhanced Hydrothermal Stability and Propylene Selectivity of Electron Beam Irradiation-Induced Hierarchical Fluid Catalytic Cracking Additives. Catalysts 2025, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, J.; Beato, P.; Lundegaard, L.F.; Skibsted, J. Distribution of Aluminum over the Tetrahedral Sites in ZSM-5 Zeolites and Their Evolution after Steam Treatment. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 15595–15613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehla, S.; Kukade, S.; Kumar, P.; Rao, P.; Sriganesh, G.; Ravishankar, R. Fine tuning H-transfer and β-scission reactions in VGO FCC using metal promoted dual functional ZSM-5. Fuel 2019, 242, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behravesh, E.; Kumar, N.; Balme, Q.; Roine, J.; Salonen, J.; Schukarev, A.; Mikkola, J.-P.; Peurla, M.; Aho, A.; Eränen, K.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of Au nano particles supported catalysts for partial oxidation of ethanol: Influence of solution pH, Au nanoparticle size, support structure and acidity. J. Catal. 2017, 353, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, A.; Wolski, L.; Ziolek, M. Lights and Shadows of Gold Introduction into Beta Zeolite. Molecules 2020, 25, 5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Bian, Y.; Dai, W. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites in zeolites: A combined probe-assisted 1H MAS NMR and NH3-TPD investigation. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 43, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tututi-Ríos, E.; González, H.; Gutiérrez-Alejandre, A.; Rico, J.L. Conversion of fructose over mesoporous Sn-KIT-6-PrSO3H catalysts: Impact of the Brønsted/Lewis acid sites molar ratio on the main reaction pathways. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 370, 113051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Q.; Liu, S.-Y.; Zhang, H.-K.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Ren, J. Effect of metal precursor solvent on n-dodecane isomerization of Pt/ZSM-22. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2018, 46, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.; Pant, K.K.; John, M.; Kumar, K.; Pai, S.M.; Newalkar, B.L. Hydroisomerization of n-hexadecane over Pt/ZSM-22 framework: Effect of divalent cation exchange. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 404–405, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Bai, D.; Zeyaodong, P.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Liang, C. Hydroisomerization of n-hexadecane over Pt/ZSM-48 catalysts: Effects of metal-acid balance and crystal morphology. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 330, 111637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batova, T.I.; Stashenko, A.N.; Obukhova, T.K.; Snatenkova, Y.M.; Khramov, E.V.; Sadovnikov, A.A.; Golubev, K.B.; Kolesnichenko, N.V. Oxidative carbonylation of methane into acetic acid: Effect of metal (Zn, Cu, La, and Mg) doping on Rh/ZSM-5 activity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 366, 112953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Shen, Z.; Peng, B.; Gu, M.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, B.; Zhang, Y. Selective chemical conversion of sugars in aqueous solutions without alkali to lactic acid over a Zn-Sn-beta lewis acid-base catalyst. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Long, J.; Wei, S.; Gao, Y.; Yang, D.; Dai, Y.; Yang, Y. Non-oxidative propane dehydrogenation over Co/Ti-ZSM-5 catalysts: Ti species-tuned Co state and surface acidity. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 341, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Hassan, A.I. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanomaterials for Application in Cost-Effective Electrochemical Devices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Cueto, J.; Alonso-Doncel, M.d.M.; Kubů, M.; Čejka, J.; Serrano, D.P.; García-Muñoz, R.A. Propane dehydrogenation over Pt and Ga-containing MFI zeolites with modified acidity and textural properties. Catal. Today 2024, 427, 114437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmani, Y.; Bouzekri, O.; Lamhasni, T.; Aadnan, I.; Abouarnadasse, S.; Lima, E.C. Catalytic oxidation of isopropanol: A critical review. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 426, 127331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auepattana-Aumrung, C.; Márquez, V.; Wannakao, S.; Jongsomjit, B.; Panpranot, J.; Praserthdam, P. Role of Al in Na-ZSM-5 zeolite structure on catalyst stability in butene cracking reaction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, V.K.; Apesteguía, C.R.; Di Cosimo, J.I. Acid–base properties and active site requirements for elimination reactions on alkali-promoted MgO catalysts. Catal. Today 2000, 63, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doheim, M.M.; Hanafy, S.A.; El-Shobaky, G.A. Catalytic conversion of ethanol and isopropanol over the Mn2O3/Al2O3 system doped with Na2O. Mater. Lett. 2002, 55, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Molla, S.A.; Hammed, M.N.; El-Shobaky, G.A. Catalytic conversion of isopropanol over NiO/MgO system doped with Li2O. Mater. Lett. 2004, 58, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.E.-A.A.; El-Wahab, M.M.A.; Goda, M.N. Selective synthesis of acetone from isopropyl alcohol over active and stable CuO–NiO nanocomposites at relatively low-temperature. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Wachs, I.E. Isopropanol oxidation by pure metal oxide catalysts: Number of active surface sites and turnover frequencies. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2002, 237, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmier, K.; Chizallet, C.; Cadran, N.; Maury, S.; Abboud, J.; Lamic-Humblot, A.-F.; Marceau, E.; Lauron-Pernot, H. Mechanistic investigation of isopropanol conversion on alumina catalysts: Location of active sites for alkene/ether production. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4423–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, F.P.; Dry, M.E.; Möller, K.P. Single stage synthesis of diisopropyl ether—An alternative octane enhancer for lead-free petrol. Catal. Today 1999, 49, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmier, K.; Chizallet, C.; Maury, S.; Cadran, N.; Abboud, J.; Lamic-Humblot, A.; Marceau, E.; Lauron-Pernot, H. Isopropanol Dehydration on Amorphous Silica–Alumina: Synergy of Brønsted and Lewis Acidities at Pseudo-Bridging Silanols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.; Pawelec, B.; Quintana, J.; Olivas, A. Effect of the acidity of alumina over Pt, Pd, and Pt–Pd (1:1) based catalysts for 2-propanol dehydration reactions. Fuel 2013, 105, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. Inorganic solid acids and their use in acid-catalyzed hydrocarbon reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 559–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckhuysen, B.M.; Yu, J. Recent advances in zeolite chemistry and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7022–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H. Heterogeneous Basic Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 537–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, V.; Corma, A.; Iglesias, M.; Rincón, J.; Sánchez, F. Hybrid organic—Inorganic catalysts: A cooperative effect between support, and palladium and nickel salen complexes on catalytic hydrogenation of imines. J. Catal. 2004, 224, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisnet, M.; Magnoux, P. Organic chemistry of coke formation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 212, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.O.; Thabet, M.S.; El-Nasser, K.S.; Hassan, A.M.; Salama, T.M. Synthesis of nanosized ZSM-5 zeolite from rice straw using lignin as a template: Surface-modified zeolite with quaternary ammonium cation for removal of chromium from aqueous solution. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 160, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Linsen, B.G.; Osinga, T.J. Studies on pore systems in catalysts VI. The universal t curve. J. Catal. 1965, 4, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlocher, C.; McCusker, L. Database of Zeolite Structures. Framework Type MEL (Material: ZSM-11, ZSM-5). Available online: https://www.iza-structure.org/databases/ (accessed on 13 April 2013).

- Johnson, A.G.; Gill, P.M.W.; Pople, J.A. The performance of a family of density functional methods. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.S.; Stephen Binkley, J.S.; Pople, J.A.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. 22. Small split-valence basis sets for second-row elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104(10), 2797–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WPietro, W.J.; Francl, M.M.; Hehre, W.J.; DeFrees, D.J.; Pople, J.A.; Binkley, J.S. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. 24. Supplemented small split-valence basis sets for second-row elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francl, M.M.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J.; Binkley, J.S.; Gordon, M.S.; DeFrees, D.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Molnar, L.F.; Jung, Y.; Kussmann, J.; Ochsenfeld, C.; Brown, S.T.; Gilbert, A.T.B.; Slipchenko, L.V.; Levchenko, S.V.; O’Neill, D.P.; et al. Advances in methods and algorithms in a modern quantum chemistry program package. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 317–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | SBET (m2/g) | St (m2/g) | Vp Total (cm3/g) | r− (Å) | Sμ (m2/g) | Sext (m2/g) | Swid (m2/g) | Vpμ (cm3/g) | (cm3/g) | Average Crystal Size (nm) | Intensity % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 | 567 | 542 | 0.227 | 23.26 | 495 | 52 | 72 | 0.261 | 0.067 | 56 | 100 |

| Au/HZSM-5 | 528 | 526 | 0.267 | 22.11 | 481 | 62 | 47 | 0.215 | 0.052 | 50 | 77 |

| Pt/HZSM-5 | 534 | 516 | 0.286 | 22.74 | 481 | 35 | 53 | 0.218 | 0.063 | 50 | 81 |

| Catalyst | Brønsted Acid Sites (μmol·g−1) | Lewis Acid Sites (μmol·g−1) | BAS/LAS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 | 43 | 78 | 0.55 | In this work |

| Au/HZSM-5 | 51 | 54 | 0.94 | |

| Pt/HZSM-5 | 63 | 50 | 1.26 | |

| Pt/ZSM-22 | 83 | 74 | 1.12 | 39 |

| Pt/ZSM-22 | 46 | 14 | 3.29 | 40 |

| Pt/ZSM-48 | 127 | 25 | 5.08 | 41 |

| Zn/Rh/ZSM-5 | 165 | 348 | 0.5 | 42 |

| Temperature (°C) | Solid Catalyst | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 | 4% Au/HZSM-5 | 4% Pt/HZSM-5 | |||||||

| Sp | Sa | So | Sp | Sa | So | Sp | Sa | So | |

| 100 | 55 | 45.8 | 0.2 | 68.4 | 31.4 | 0.2 | 55 | 44.8 | 0.2 |

| 110 | 58 | 42.8 | 0.2 | 82.0 | 17.6 | 0.4 | 65 | 34.5 | 0.5 |

| 120 | 66 | 33.7 | 0.3 | 88.5 | 10.9 | 0.6 | 83 | 16.3 | 0.7 |

| 130 | 73 | 26.7 | 0.3 | 92.0 | 7.2 | 0.8 | 89 | 10.0 | 1.0 |

| 140 | 75 | 24.4 | 0.6 | 94.0 | 5.1 | 0.9 | 94 | 4.8 | 1.2 |

| 175 | 89 | 10 | 1.0 | 98.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 98 | 0.9 | 1.5 |

| 200 | 98 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 97.6 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 96.5 | 0.1 | 3.4 |

| 225 | 96 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 93.4 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 87.1 | 0.1 | 12.8 |

| 275 | 70 | 0.5 | 29.5 | 65.2 | 0.4 | 34.4 | 68.0 | 0.1 | 31.9 |

| Catalyst Samples | Dehydration Rate (mol g−1 h−1) | Rate Constants (h−1) | TOF (h−1) × 103 | ∆E kJ/mol | ln A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dehydration Rate | Dehydrogenation Rate (Acetone) | Oligomerization Rate | |||||

| HZSM-5 | 0.152 | 0.017 | 0.0017 | 0.89 | 3.5 | 140.12 | 35.82 |

| Au/HZSM-5 | 0.166 | 0.0087 | 0.0015 | 0.98 | 3.3 | 137.45 | 36.24 |

| Pt/HZSM-5 | 0.166 | 0.0082 | 0.0020 | 0.98 | 2.6 | 120.7 | 30.87 |

| CODE | E | Eele | Estb | Eint | Eels | Etor | Enb | Esol | Estr | Evdw | PA | VSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HZSM-5 | −21.269 | −98.47 | −0.275 | −3.906 | −222.946 | 8.302 | −222.946 | 68.813 | 12.062 | 4.530 | 545.360 | 472.281 |

| Au/HZSM-5 | −38.633 | −118.39 | −0.086 | −10.862 | −326.846 | 5.231 | −326.846 | −15.599 | 22.372 | 54.550 | 498.430 | 447.535 |

| Pt/HZSM-5 | −40.4675 | −119.375 | −4.939 | −49.765 | −418.974 | 3.484 | −388.974 | −53.103 | 89.12 | 0.4006 | 460.123 | 523.885 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alenezy, E.K.; El-Molla, S.A.; El-Nasser, K.S.; Sabri, Y.; Ali, I.O. ZSM-5 Nanocatalyst from Rice Husk: Synthesis, DFT Analysis, and Au/Pt Modification for Isopropanol Conversion. Catalysts 2026, 16, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010110

Alenezy EK, El-Molla SA, El-Nasser KS, Sabri Y, Ali IO. ZSM-5 Nanocatalyst from Rice Husk: Synthesis, DFT Analysis, and Au/Pt Modification for Isopropanol Conversion. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezy, Ebtsam K., Sahar A. El-Molla, Karam S. El-Nasser, Ylias Sabri, and Ibraheem O. Ali. 2026. "ZSM-5 Nanocatalyst from Rice Husk: Synthesis, DFT Analysis, and Au/Pt Modification for Isopropanol Conversion" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010110

APA StyleAlenezy, E. K., El-Molla, S. A., El-Nasser, K. S., Sabri, Y., & Ali, I. O. (2026). ZSM-5 Nanocatalyst from Rice Husk: Synthesis, DFT Analysis, and Au/Pt Modification for Isopropanol Conversion. Catalysts, 16(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010110