Scalable Electro-Oxidation Engineering of Raney Nickel Toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

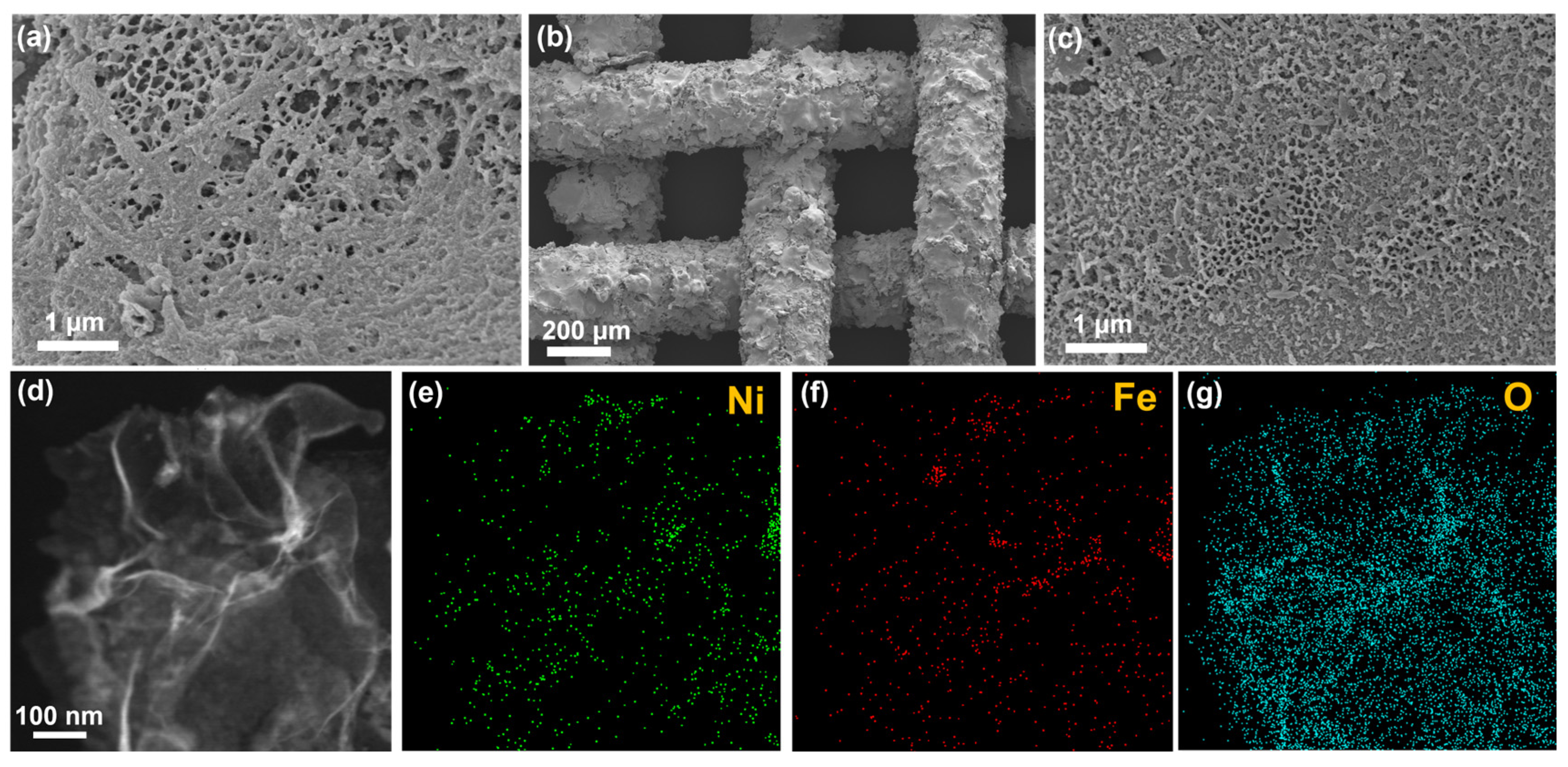

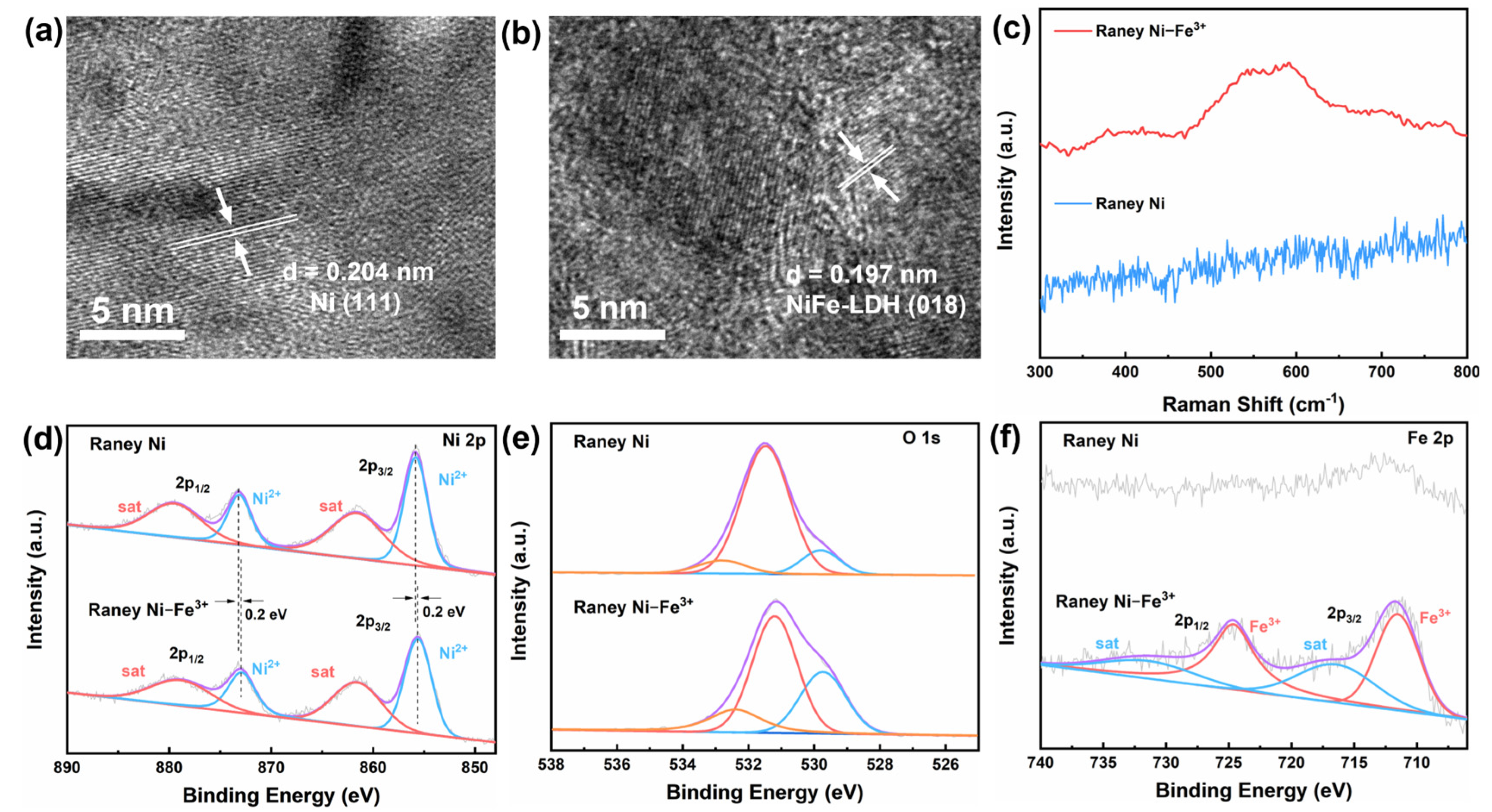

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Preparation of the Raney Ni–Fe3+ and Raney Ni–NaOH

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Electrochemical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Qin, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Meng, X. Engineering active and robust alloy-based electrocatalyst by rapid Joule-heating toward ampere-level hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Yang, J.; Xu, F.; Weng, B. Recent Advancements on Spin Engineering Strategies for Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reactions. Small 2024, 5, e2401057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.Z.X.; Lin, S.; Liu, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, H. Corrosion engineering for electrode fabrication toward alkaline water electrolysis. Chem. Synth. 2025, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Zhong, Q.; Ji, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, R.; Tang, J.; et al. Sustainable and cost-efficient hydrogen production using platinum clusters at minimal loading. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Pang, D.; Wang, C.; Fu, Z.; Liu, N.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Jia, B.; Guo, Z.; Fan, X.; et al. Vacancy and Dopant Co-Constructed Active Microregion in Ru-MoO3-x/Mo2AlB2 for Enhanced Acidic Hydrogen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202504084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Song, C.; Li, X.; Jia, Q.; Wu, P.; Lou, Z.; Ma, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, L. Defect-rich FeCoNiMnRu high-entropy alloys with activated interfacial water for boosting alkaline water/seawater hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Q.; Wang, S.; Yan, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, X.; Li, T.; Li, H.; Zhuang, Z.; et al. 10,000-h-stable intermittent alkaline seawater electrolysis. Nature 2025, 639, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Kang, M.; Huang, K.; Xu, H.G.; Wu, Y.X.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, H.; Fang, S.R.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Stable Ni(II) sites in Prussian blue analogue for selective, ampere-level ethylene glycol electrooxidation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.F.; Li, Z.Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.C.; Xi, G.Q.; Zhao, X.J.; Zhang, C.X.; Liao, W.G.; Ho, J.C. Defect-Engineered Multi-Intermetallic Heterostructures as Multisite Electrocatalysts for Efficient Water Splitting. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2502244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, G. Amorphous MnRuOx Containing Microcrystalline for Enhanced Acidic Oxygen-Evolution Activity and Stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 136, e202405641–e202405648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wan, W.; Erni, R.; Pan, L.; Patzke, G.R. Operando Spectroscopic Monitoring of Metal Chalcogenides for Overall Water Splitting: New Views of Active Species and Sites. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202400048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Shi, X.; Bao, Y.; Chen, Y. Construction of triple heterogeneous interfaces optimizing electronic structure with B-doped amorphous CoP deposited on crystalline Cu2S/Ni3S2 nanosheets to enhance water electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 16592–16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Meng, X.; Xia, J.; Zhang, G. Constructing Ru-O–TM bridge in NiFe–LDH enables high current hydrazine-assisted H2 production. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2401694–2401704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, J.Q.; Ju, M.; Chen, Y.P.; Yuan, H.F.; Li, S.M.; Li, J.L.; Guo, D.X.; Hong, M.; Yang, S.H. Combustion growth of NiFe layered double hydroxide for efficient and durable oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 28526–28536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Q.; Sun, W.; Sun, K.; Shen, Y.; An, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Zou, X. Nanostructured intermetallics: From rational synthesis to energy electrocatalysis. Chem. Synth. 2023, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gong, Y.; Zi, X.; Gan, L.; Pensa, E.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, K.; Fu, J.; et al. Coupling nano and atomic electric field confinement for robust alkaline oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202405438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Fu, R.; Ge, J.; Yang, W.; Hong, X.; Sun, C.; Liao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Iron Molybdenum Sulfide-Supported Ultrafine Ru Nanoclusters for Robust Sulfion Degradation-Assisted Hydrogen Production. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2315326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Song, S.Z.; Wu, W.T.; Deng, Z.F.; Tang, C. Bridging laboratory electrocatalysts with industrially relevant alkaline water electrolyzers. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303451–2303463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, M.; Jia, F.; Huang, J.; Amini, A.; Song, S.; Yi, H.; Cheng, C. Noble-Metal-Free oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts working at high current densities over 1000 mA cm−2: From fundamental understanding to design principles. Energy Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-W.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.-X.; Zhu, Q.-X.; Xu, Y.-X.; Lu, Z.-Q.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Z.-P.; Xu, G.-Y. From laboratory to industrial scale: Nickel-based catalysts for hydrogen evolution under highcurrent-density alkaline electrolysis. Rare Met. 2025, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elrahim, A.G.; Ali, M.A.; Chun, D.-M. Enhanced oxygen evolution using sulfate-intercalated amorphous FeNiS@FeS layered double hydroxide nanoflowers for advanced water-splitting performance. J. Power Sources 2025, 635, 236472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Tang, J.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Xia, C. Recent Developments in Single-Atom Engineering Ir/Ru-Based Catalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Acidic Media. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, e04414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhong, J.; Yan, S.; Zou, Z. Reagent-adaptive active site switching on the IrOx/Ni(OH)2 catalyst. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Weiser, G.; Klingenhof, M.; Koketsu, T.; Liu, S.; Pi, Y.; Henkelman, G.; Shi, X.; Li, J.; et al. Ru Single Atoms and Sulfur Anions Dual-Doped NiFe Layered Double Hydroxides for High-Current-Density Alkaline Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2500554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, M.; Wang, F.; Lei, W.; Qiang, H.; Xia, M. Research progress on non-precious-metal-based transition metal alkaline OER electrocatalysts. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 120378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.-J.; Ran, N.; Zhou, W.; An, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, W.; Zhou, M.; Lin, W.-F.; Liu, J.; Guo, L. Synergistic Atomic Environment Optimization of Nickel-Iron Dual Sites by Co Doping and Cr Vacancy for Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Huang, X.; Han, S.; Xie, C.; Yang, F.; Wu, X.; Ye, S.; Huang, L.; Zheng, L.; Yang, X.; et al. Asymmetric Fe–O–Ni Pair Sites in Two-Step Dealloyed Prussian Blue Analogue Nanocubes Enrich Linear-Adsorbed Intermediates for Efficient Oxygen Evolution. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 33230–33245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Ren, X.; Rong, Z. Raney Ni as a Versatile Catalyst for Biomass Conversion. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 10508–10536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, F.; Chen, C.; Shen, J.; Wei, Z.; Dong, W.; Peng, Y.; Fan, R.; Shen, M.; Olu, P.-Y. Dynamic and interconnected influence of dissolved iron on the performance of alkaline water electrolysis. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 9913–9919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Lin, Y.X.; Fang, P.; Wang, M.S.; Zhu, M.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, J.S.; Hu, J.G.; Xu, X.Y. Orderly nanodendritic nickel substitute for Raney nickel catalyst improving Alkali Water Electrolyzer. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2307035–2307045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, C.; Wang, J.; Danlos, Y.; Liu, T.; Deng, C.; Chen, C.; Liao, H.; Kyriakou, V. Novel Fe-Modulating Raney-Ni Electrodes toward High-Efficient and Durable AEM Water Electrolyzer. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2501634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Xiao, H.; Liu, G. Raney nickel induced interface modulation of active NiFe-hydroxide as efficient and robust electrocatalyst towards oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2024, 683, 119858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Lv, J.; Lu, X.; Shen, W. Multiscale Design for Neutral-Electrolyte H2O2 Electrosynthesis: Catalysts, Electrodes, Devices, and Hybrid Processes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e11806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-I.; Wang, E.-C.; Kim, H.-A. Fabrication of highly porous Raney Ni electrocatalyst using hot-dip galvanizing. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 165, 150894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Duan, D.; Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Peng, B.; An, P.; Zhang, J.; et al. The rapid self-reconstruction of Fe-modified Ni hydroxysulfide for efficient and stable large-current-density water/seawater oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 4647–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yang, G.; Dong, C.; He, M. Unraveling the Dynamic Reconstruction of Active Co(IV)-O Sites on Ultrathin Amorphous Cobalt-Iron Hydroxide Nanosheets for Efficient Oxygen-Evolving. Small 2024, 20, 2404205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Shao, M.; An, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, S.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Fast electrosynthesis of Fe-containing layered double hydroxide arrays toward highly efficient electrocatalytic oxidation reactions. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 6624–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Hong, D.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.; Lee, H.M.; Cho, E. Highly porous Ni–P electrode synthesized by an ultrafast electrodeposition process for efficient overall water electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 12069–12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xue, S.X.; Tang, C.J.; Gao, H.F.; Gao, D.Y. FeCoNi(OH)x/Ni mesh electrode boosting oxygen evolution reaction for high-performance alkaline water electrolysis. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2023, 129, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S. Growing Nanocrystalline Ru on Amorphous/Crystalline Heterostructure for Efficient and Durable Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts 2025, 15, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Ye, Z.; Hu, H.; Lei, L.; You, F.; Yao, J.; Yang, H.; Jiang, X. Magnetic field-assisted microbial corrosion construction iron sulfides incorporated nickel-iron hydroxide towards efficient oxygen evolution. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2024, 43, 100200–100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, Z.C.; Yang, H.; Jian, R.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xia, P.; Liu, W.; Fontaine, O.; Zhu, Y.C.; Li, L.M.; et al. Superfast hydrous-molten salt erosion to fabricate large-size self-supported electrodes for industrial-level current OER. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148887–148902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.S.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X. Mesocrystalline Zn-doped Fe3O4 hollow submicrospheres: Formation mechanism and enhanced photo-Fenton catalytic performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8900–8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, J.; Wölfel, J.P.; Weiss, M.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, S.; Marschall, R. Medium-and high-entropy spinel ferrite nanoparticles via low-temperature synthesis for the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lin, S. Tailoring atomically local electric field of NiFe layered double hydroxides with Ag dopants to boost oxygen evolution kinetics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 668, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Tong, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Lin, S. Intentional Replacement Acceleration Layer Strategy Achieves Superior Water/Seawater Electrolysis at Industrial-Level Current Densities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2502055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, J.; Shen, Y.; Jiao, W.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Zou, X. Room temperature, fast fabrication of square meter-sized oxygen evolution electrode toward industrial alkaline electrolyzer. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 316, 121605–121613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, D.; Tan, X.; Feng, W.; Fu, J.; Wei, T.; Cao, M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Microenvironment reconstitution of highly active Ni single atoms on oxygen-incorporated Mo2C for water splitting. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.L.; Tan, J.L.; Jin, Z.Y.; Gu, C.Y.; Lv, Q.X.; Dong, Y.W.; Lv, R.Q.; Dong, B.; Chai, Y.M. In Situ Electrochemical Rapid Induction of Highly Active gamma-NiOOH Species for Industrial Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer. Small 2024, 20, e2310064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Yi, Y.; Song, Y.; Guan, D.; Xu, M.; Ran, R.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. The BaCe0.16Y0.04Fe0.8O3-δ nanocomposite: A new high-performance cobalt-free triple-conducting cathode for protonic ceramic fuel cells operating at reduced temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 5381–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Shi, J.; Huang, T.; Xie, M.Y.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Xian, M.H.; Huang, G.F.; Wan, H.; Hu, W.; Huang, W.Q. Cation-Induced Deep Reconstruction and Self-Optimization of NiFe Phosphide Precatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution and Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314172–2314186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Du, Z.; Lai, X.; Lan, J.; Liu, X.; Liao, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, H. Synergistically modulating the electronic structure of Cr-doped FeNi LDH nanoarrays by O-vacancy and coupling of MXene for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Yu, Z.R.; Zhang, Y.; Barras, A.; Addad, A.; Roussel, P.; Tang, L.C.; Naushad, M.; Szunerits, S.; Boukherroub, R. Construction of desert rose flower-shaped NiFe LDH-Ni3S2 heterostructures via seawater corrosion engineering for efficient water-urea splitting and seawater utilization. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 19578–19590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Qian, J.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Lv, C.; Li, L.; Bandaru, S.; Gao, J. Self-Reconstructed Spinel with Enhanced SO42− Adsorption and Highly Exposed Co3+ From Heterostructure Boosts Activity and Stability at High Current Density for Overall Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2419978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Liu, C.; Fang, Z.T.; Xu, L.; Lu, C.L.; Hou, W.H. Ultrafast room-temperature synthesis of self-supported NiFe-layered double hydroxide aslLarge-current-density oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Small 2022, 18, 2104354–2104363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysea, N.B.; Gómez, M.J.; Humana, T.E.; Lacconi, G.I.; Correa Perelmuter, G.; Diaz, L.; Franceschini, E.A. Alkaline seawater as an electrolyte for hydrogen production: A feasibility and performance study. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1032, 181110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demnitz, M.; van der Schaaf, J.; de Groot, M.T. Alkaline Water Electrolysis Beyond 3 A/cm2 Using Catalyst Coated Diaphragms. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 014504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; He, X.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Z.; Sun, S.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y. Fabrication of a hierarchical NiTe@NiFe–LDH core-shell array for high-efficiency alkaline seawater oxidation. Iscience 2024, 27, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Wei, L.; Wang, H.; Lin, C.; Su, J.; Guo, L. Synergistic yttrium doping accelerates surface reconstruction and optimizes d-band centers in NiFe–LDH for superior oxygen evolution catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 37435–37447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Wang, H.; Qi, C.; Peng, X.; Pan, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Ye, L.; Xiao, Q.; Luo, W. Regulating Pt electronic properties on NiFe layered double hydroxide interface for highly efficient alkaline water splitting. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2024, 342, 123352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Park, S.K. Metal-organic framework-derived hollow CoSx nanoarray coupled with NiFe layered double hydroxides as efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Small 2022, 18, 2200586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; He, R.; Pan, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Lattice distortion induced Ce-doped NiFe–LDH for efficient oxygen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Tan, L.; Liu, X.; Wen, Y.; Hou, W.; Zhan, T. Electrodeposition of NiFe-layered double hydroxide layer on sulfur-modified nickel molybdate nanorods for highly efficient seawater splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 613, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, F.; Sun, S.; Wei, K.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; An, J.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J. Phase regulation of Ni (OH)2 nanosheets induced by W doping as self-supporting electrodes for boosted water electrolysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tao, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, G.; Zhao, K.; Cai, R.; Tao, K.; Zhang, C.; Sun, M.; Hu, J. Atomically targeting NiFe LDH to create multivacancies for OER catalysis with a small organic anchor. Nano Energy 2021, 81, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Xin, L.; Liu, D.; Hou, W.; Zhan, T. Partial sulfidation strategy to NiFe–LDH@FeNi2S4 heterostructure enable high-performance water/seawater oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tong, L.; Huang, Q.; Ma, J.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Xi, H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, S. Scalable Electro-Oxidation Engineering of Raney Nickel Toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts 2026, 16, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010008

Ma Y, Zhang X, Tong L, Huang Q, Ma J, Gao H, Zhang J, Xi H, Liu Y, Lin S. Scalable Electro-Oxidation Engineering of Raney Nickel Toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yutian, Xu Zhang, Li Tong, Quanbin Huang, Junhu Ma, Hongfu Gao, Juan Zhang, Hailong Xi, Yipu Liu, and Shiwei Lin. 2026. "Scalable Electro-Oxidation Engineering of Raney Nickel Toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010008

APA StyleMa, Y., Zhang, X., Tong, L., Huang, Q., Ma, J., Gao, H., Zhang, J., Xi, H., Liu, Y., & Lin, S. (2026). Scalable Electro-Oxidation Engineering of Raney Nickel Toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Catalysts, 16(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010008