Sustainable Carbon–Carbon Composites from Biomass-Derived Pitch: Optimizing Structural, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties via Catalyst Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

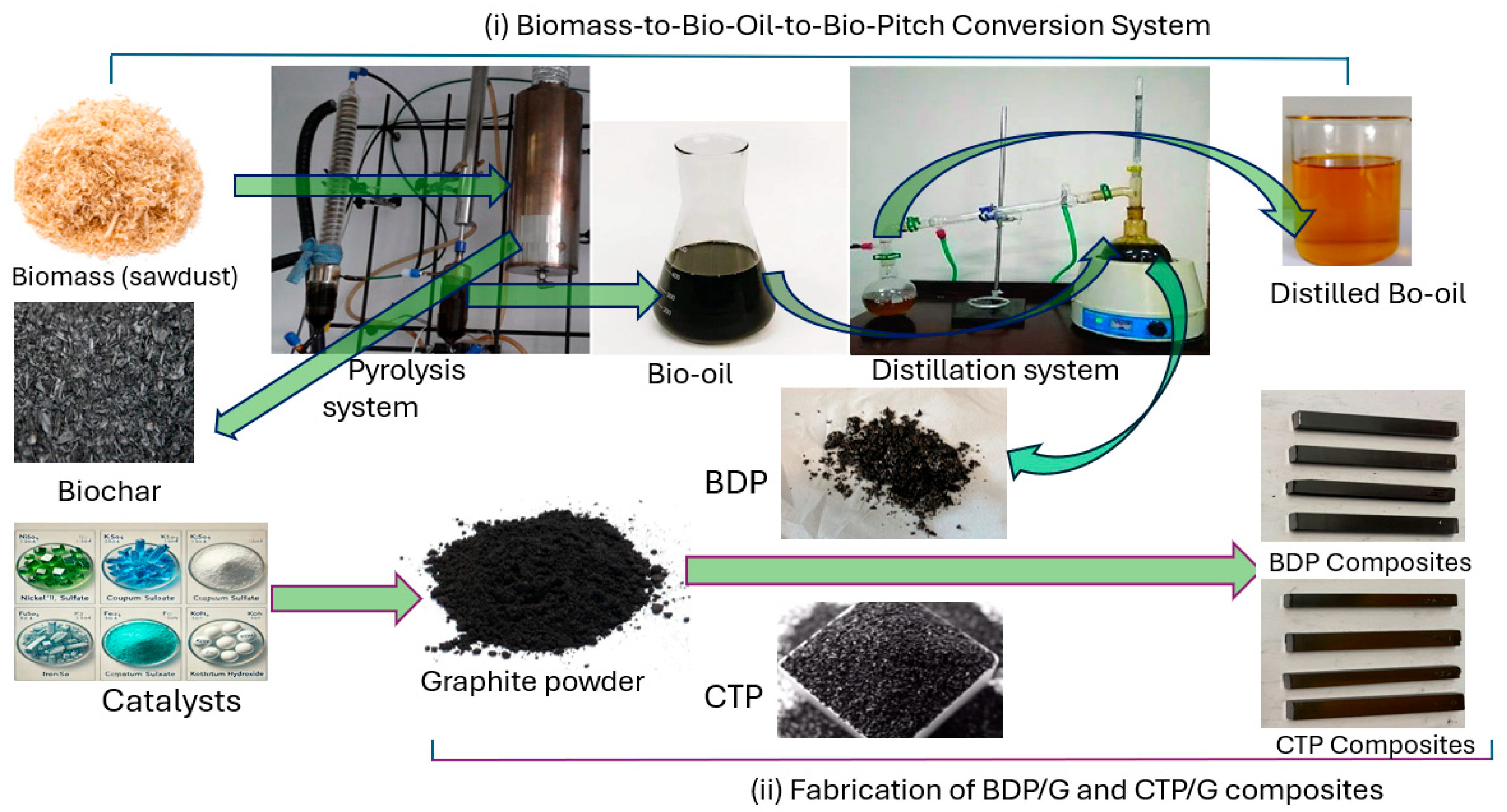

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Composition and Surface Wettability Analysis of BDP and CTP

2.2. Thermal Stability and pH Analysis of BDP and CTP

2.3. Carbon-Carbon Composites Based on BDP and CTP

2.3.1. Microstructure of the Graphitized Composites

2.3.2. Physical Properties of Graphitized Carbon-Carbon Composites

2.3.3. Electrical Properties of the Carbon-Carbon Composites

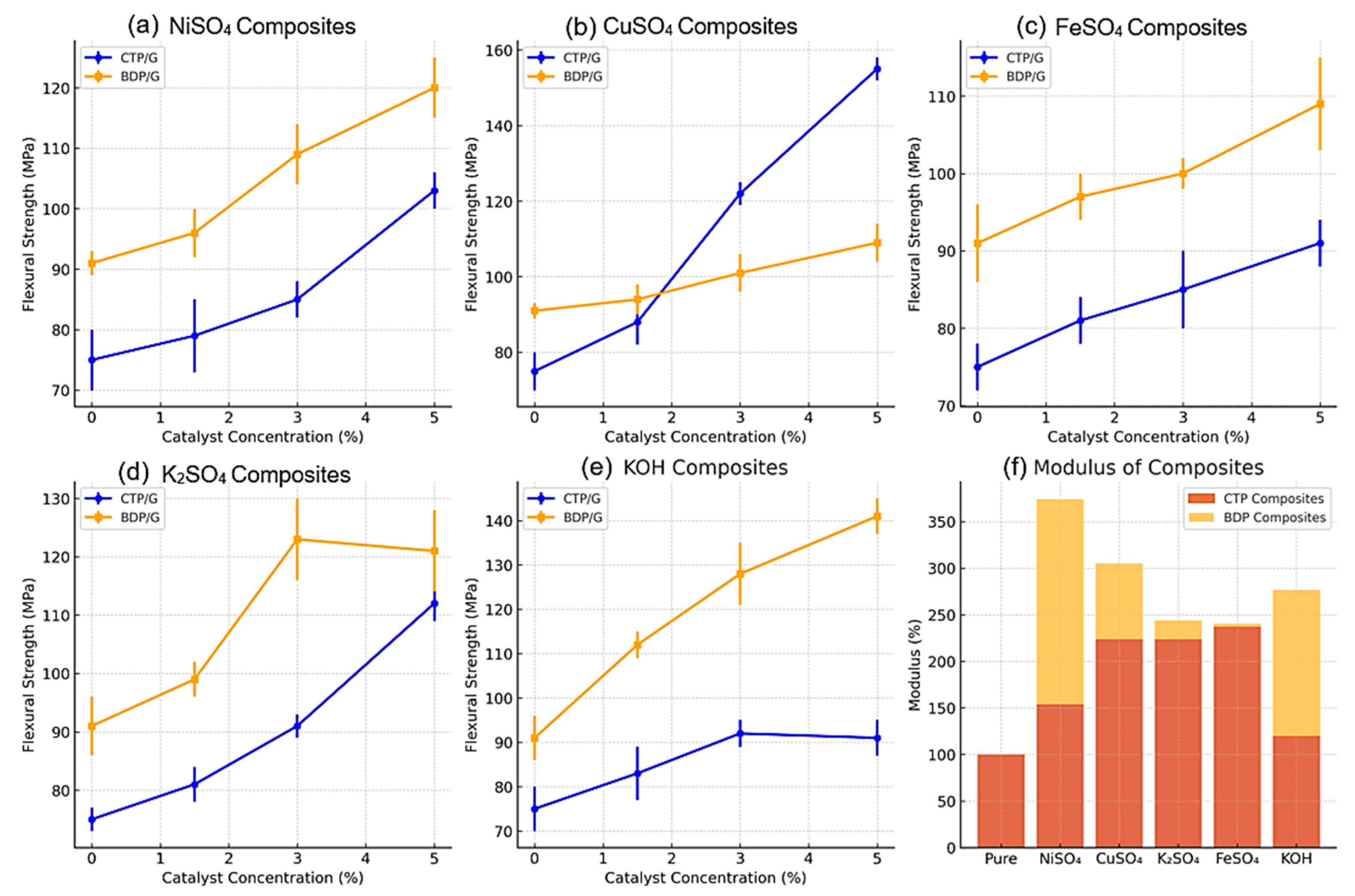

2.3.4. Mechanical Properties Enhancement with Different Catalysts

2.3.5. The Role of Catalysts in Enhancing Carbon-Carbon Composites

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Production and Characterization of Bio-Oil

3.3. Synthesis and Characterization of BDP

3.4. Synthesis and Characterization of Carbon-Carbon Composites

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, X.; Picard, D.; Mollaabbasi, R.; Ollevier, T.; Alamdari, H. Synthesis and Characterization of Bio-pitch from Bio-oil. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11772–11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Mollaabbasi, R.; Picard, D.; Ziegler, D.; Alamdari, H. Physical and Chemical Characterization of Bio-pitch as a Potential Binder for Anode. In Light Metals; Chesonis, C., Ed.; The Minerals, Metals & Materials Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1229–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinh, A.R.; Luengo, C.A. Mass balance of biocarbon electrodes obtained by experimental bench production. In Developments in Thermochemical Biomass Conversion; Bridgwater, A.V., Boocock, D.G.B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lis, T.; Korzec, N.; Frohs, W.; Tomala, J.; Frączek-Szczypta, A.; Błażewicz, S. Wood-derived tar as a carbon binder precursor for carbon and graphite technology. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2016, 36, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hussein, A.; Lauzon-Gauthier, J.; Ollevier, T.; Alamdari, H. Biochar as an Additive to Modify Biopitch Binder for Carbon Anodes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 12406–12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ōya, A.; Marsh, H. Phenomena of Catalytic Graphitization. J. Mater. Sci. 1982, 17, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hussein, A.; Li, D.; Huang, X.; Mollaabbasi, R.; Picard, D.; Ollevier, T.; Alamdari, H. Properties of Bio-pitch and Its Wettability on Coke. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 15366–15374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, A.R.; Luengo, C.A. Preparing and Characterizing Electrode Grade Carbons from Eucalyptus Pyrolysis Products. In Advances in Thermochemical Biomass Conversion; Bridgwater, A.V., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 1230–1240. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, A.R.; Rocha, J.D.; Luengo, C.A. Preparing and Characterizing Biocarbon Electrodes. Fuel Process. Technol. 2000, 67, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kocaefe, D.; Kocaefe, Y.; Sarkar, D.; Bhattacharyay, D.; Morais, B.; Chabot, J. Coke-Pitch Interactions During Anode Preparation. Fuel 2014, 117, 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.; Picard, D.; Alamdari, H. Biopitch as a Binder for Carbon Anodes: Impact on Carbon Anode Properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 4681–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataluna, R.; Shah, Z.; Venturi, V.; Caetano, N.R.; da Silva, B.P.; Azevedo, C.M.N.; Oliveira, L.P. Production Process of Di-Amyl Ether and Its Use as an Additive in the Formulation of Aviation Fuels. Fuel 2018, 228, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamási, K.; Kollár, M.S. Effect of Different Sulfur Content in Natural Rubber Mixture on Their Thermo-Mechanical and Surface Properties. Int. J. Eng. Res. Sci. 2018, 4, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.; Babadagli, T. Wettability Alteration: A Comprehensive Review of Materials/Methods and Testing the Selected Ones on Heavy-Oil Containing Oil-Wet Systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 220, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, Z.; Veses, R.C.; Silva, R.D. A Comparative Study and Analysis of Two Types of Bio-Oil Samples Obtained from Freshwater Algae and Microbial-Treated Algae. Mod. Chem. Appl. 2016, 4, 1000185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Coal-Tar Pitch. High Temperature. In Summary Risk Assessment Report—Environment; EU Coal-Tar Pitch: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Z.; Cataluña Veses, R.; da Silva, R. Using GC-MS to Analyze Bio-Oil Produced from Pyrolysis of Agricultural Wastes: Discarded Soybean Frying Oil, Coffee, and Eucalyptus Sawdust in the Presence of 5% Hydrogen and Argon. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2016, 7, 1000300. [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorf, R.J.; Tokarsky, E. High-Performance Carbon Fibers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1975, 15, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Fuertes, A.B. The Production of Carbon Materials by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Cellulose. Carbon 2009, 47, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Kocaefe, D.; Kocaefe, Y.; Huang, X.; Bhattacharyay, D.; Coulombe, P. Study of the Wettability of Coke by Different Pitches and Their Blends. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 9210–9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanyuk, O.; Varga, M.; Tulic, S.; Izak, T.; Jiricek, P.; Kromka, A.; Skakalova, V.; Rezek, B. Study of Ni-catalyzed graphitization process of diamond by in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 6629–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Garay, J.; Liu, G.; Balandin, A.A.; Abbaschian, R. Growth of Large-Area Graphene Films from Metal-Carbon Melts. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 108, 094321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanada, S.; Nagai, M.; Ito, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Ogura, M.; Takeuchi, D.; Yamasaki, S.; Inokuma, T.; Tokuda, N. Fabrication of Graphene on Atomically Flat Diamond (111) Surfaces Using Nickel as a Catalyst. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2017, 75, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chang, Q.H.; Guo, G.L.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.Q.; Wang, T.; Ling, B.; Yang, H.F. Synthesis of High-Quality Graphene Films on Nickel Foils by Rapid Thermal Chemical Vapor Deposition. Carbon 2012, 50, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunk, M.A.; Shah, Z.; Wander, P.R. Use of Montmorillonite Clay for Adsorption of Malachite Green Dye. Periódico Tchê Química 2019, 16, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsheer, K.; Rout, C.S. Conducting polymers: A comprehensive review on recent advances in synthesis, properties and applications. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 5659–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Cataluña Veses, R.; Aguilhera, R.A.; Silva, R.D. Bio-oil production from pyrolysis of coffee and eucalyptus sawdust in the presence of 5% hydrogen. Int. J. Eng. Res. Sci. 2016, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.M.; He, R.; Jiang, M.P.; Kim, P.; Pfeiffer, L.N.; Pinczuk, A. Multilayer Graphene Grown by Precipitation upon Cooling of Nickel on Diamond. Carbon 2011, 49, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.O.; Quadri, R.O.; Lawal, O.S.; Emojevu, E.O. Physicochemical characterization, valorization of lignocellulosic waste (Kola nut seed shell) via pyrolysis, and ultrasonication of its crude bio-oil for biofuel production. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 7, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, M.; Khattak, M.A.K.; Khan, A.; Khan, M.S.; Ahmad, M.; Shah, Z.; Bibi, S. Physico-Chemical Investigations on the Catalytic Production of Biofuel from Algal Biomass. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 96, S31–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, A.O.; Quadri, R.O.; Lawal, O.S.; Malomo, D.; Emojevu, E.O.; Omonije, O.O.; Odeniyi, O.K.; Fadahunsi, M.O.; Yelwa, M.J.; Aasa, S.A.; et al. Advanced Techniques in Upgrading Crude Bio-Oil to Biofuel; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 321–353. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Z.; Saberian, M.; Hodgeman, D.; Kinloch, I.; Vallés, C. Effect of Sulfur on Wood Tar Biopitch as a Sustainable Replacement for Coal Tar Pitch Binders. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 2567–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkasabi, Y.; Mullen, C.A.; Strahan, G.D.; Wyatt, V.T. Biobased Tar Pitch Produced from Biomass Pyrolysis Oils. Fuel 2022, 318, 123300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Shen, J.; Chang, H.; Li, R.; Du, J.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Q. Reducing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons content in coal tar pitch by potassium permanganate oxidation and solvent extraction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Veses, R.C.; Vaghetti, J.C.; Amorim, V.D.; Silva, R.D. Preparation of Jet Engine Range Fuel from Biomass Pyrolysis Oil Through Hydrogenation and Its Comparison with Aviation Kerosene. Int. J. Green Energy 2019, 16, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhakarmy, M.; Kemp, A.; Biswas, B.; Kafle, S.; Adhikari, S. A Comparative Analysis of Bio-Oil Collected Using an Electrostatic Precipitator from the Pyrolysis of Douglas Fir, Eucalyptus, and Poplar Biomass. Energies 2024, 17, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veses, R.C.; Shah, Z.; Kuamoto, P.M.; Caramão, E.B.; Machado, M.E. Bio-Oil Production by Thermal Cracking in the Presence of Hydrogen. J. Fundam. Renew. Energy Appl. 2015, 6, 1000194. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Z.; Renato, C.V.; Marco, A.C.; Rosangela, D.S. Separation of Phenol from Bio-oil Produced from Pyrolysis of Agricultural Wastes. Mod. Chem. Appl. 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataluña, R.; Shah, Z.; Pelisson, L.; Caetano, N.R.; Silva, R.D.; Azevedo, C. Biodiesel Glycerides from the Soybean Ethylic Route Incomplete Conversion on the Diesel Engines Combustion Process. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2017, 28, 2447–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Cataluña Veses, R.; Silva, R.D. GC-MS and FTIR Analysis of Bio-oil Obtained from Freshwater Algae (Spirogyra) Collected from Freshwater. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Res. 2016, 2, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Wang, X. FTIR Analysis of the Functional Group Composition of Coal Tar Residue Extracts and Extractive Residues. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Veses, R.C.; Brum, J.; Klunk, M.A.; Rocha, L.A.O.; Missaggia, A.B.; Caetano, N.R. Sewage Sludge Bio-Oil Development and Characterization. Inventions 2020, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeban, S.; Veses, R.C.; Ullah, I.; Yaseen, M.; Aguilhera, R.A.; Jamal, S.; Silva, R. Analysis of Bio-Oil Obtained from Pyrolysis of Scenedesmus and Spirogyra Mixture Algal Biomass. J. Ongoing Chem. Res. 2016, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Klunk, M.A.; Dasgupta, S.; Das, M.; Shah, Z. System of Adsorption of CO2 in Coalbed. S. Braz. J. Chem. 2018, 26, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, A.P.; Lorenzini, G.; Shah, Z.; Klunk, M.A.; de Carvalho Lima, J.E.; Rocha, L.A.O.; Caetano, N.R. Hierarchical Criticality Analysis of Clean Technologies Applied to a Coal-Fired Power Plant. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2020, 15, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, N.R.; Lorenzini, G.; Lhamby, A.R.; Shah, Z.; Klunk, M.A.; Rocha, L.A.O. Modelling Safety Distance from Industrial Turbulent Non-Premixed Gaseous Jet Flames. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 5, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Klunk, M.A.; Dasgupta, S.; Das, M.; Wander, P.R.; Shah, Z. Estudo Da Adsorção Dos Corantes Violeta Cristal E Verde Malaquita Em Material Zeolítico. Periódico Tchê Química 2019, 16, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, S.L.P.; Shah, Z.; Cataluña Veses, R.; Leite, A.J.B. Processo de Obtenção de Biocarvão e de Bio-óleo Cru, Processo de Obtenção de Carvão Ativado Magnético, Carvão Ativado Magnético e Seu Uso, Uso do Bio-óleo Cru ou da Fração de Destilado de Bio-óleo e Uso do Biocarvão. UFRGS Pat. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Yu, M.; Zhou, J. Coal Tar Pitch-Based Porous Carbon Loaded MoS2 and Its Application in Supercapacitors. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 12045–12056. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, T. Highly Graphitized Coal Tar Pitch-Derived Porous Carbon as High-Performance Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400189. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Wu, J.; Ren, L.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y. Supercapacitor Performances of Coal Tar Pitch-Based Spherical Activated Carbons. J. Carbon Res. 2023, 12, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Yang, F.; Zhao, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, P. Preparation and Characterization of High-Performance Coal Tar Pitch-Based Carbon Fibers. Carbon Lett. 2023, 34, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shah, Z.; Nisar, M.; Ullah, I.; Yaseen, M.; Adeoye, A.O.; Zhang, S.; Shah, S.A.; Ullah, H. Sustainable Carbon–Carbon Composites from Biomass-Derived Pitch: Optimizing Structural, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties via Catalyst Engineering. Catalysts 2026, 16, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010074

Shah Z, Nisar M, Ullah I, Yaseen M, Adeoye AO, Zhang S, Shah SA, Ullah H. Sustainable Carbon–Carbon Composites from Biomass-Derived Pitch: Optimizing Structural, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties via Catalyst Engineering. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Zeban, Muhammad Nisar, Inam Ullah, Muhammad Yaseen, Abiodun Oluwatosin Adeoye, Shaowei Zhang, Sayyar Ali Shah, and Habib Ullah. 2026. "Sustainable Carbon–Carbon Composites from Biomass-Derived Pitch: Optimizing Structural, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties via Catalyst Engineering" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010074

APA StyleShah, Z., Nisar, M., Ullah, I., Yaseen, M., Adeoye, A. O., Zhang, S., Shah, S. A., & Ullah, H. (2026). Sustainable Carbon–Carbon Composites from Biomass-Derived Pitch: Optimizing Structural, Electrical, and Mechanical Properties via Catalyst Engineering. Catalysts, 16(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010074