Towards Flow Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Practical Approach to Point-of-Use Water Remediation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Defining the Problem

2.1. Organic and Bacterial Contamination

2.2. Contaminant Degradation vs. Full Mineralization

2.3. International Guidelines for Drinking Water Security

3. Choosing a Photocatalyst

3.1. Titanium Dioxide Powders

3.2. Improvements to Titanium Dioxide Powders

3.2.1. Reduction of Titanium Dioxide

3.2.2. Doping and Decorating TiO2 to Improve Its Performance

3.3. Beyond Titanium Dioxide: Other Possible Photocatalysts

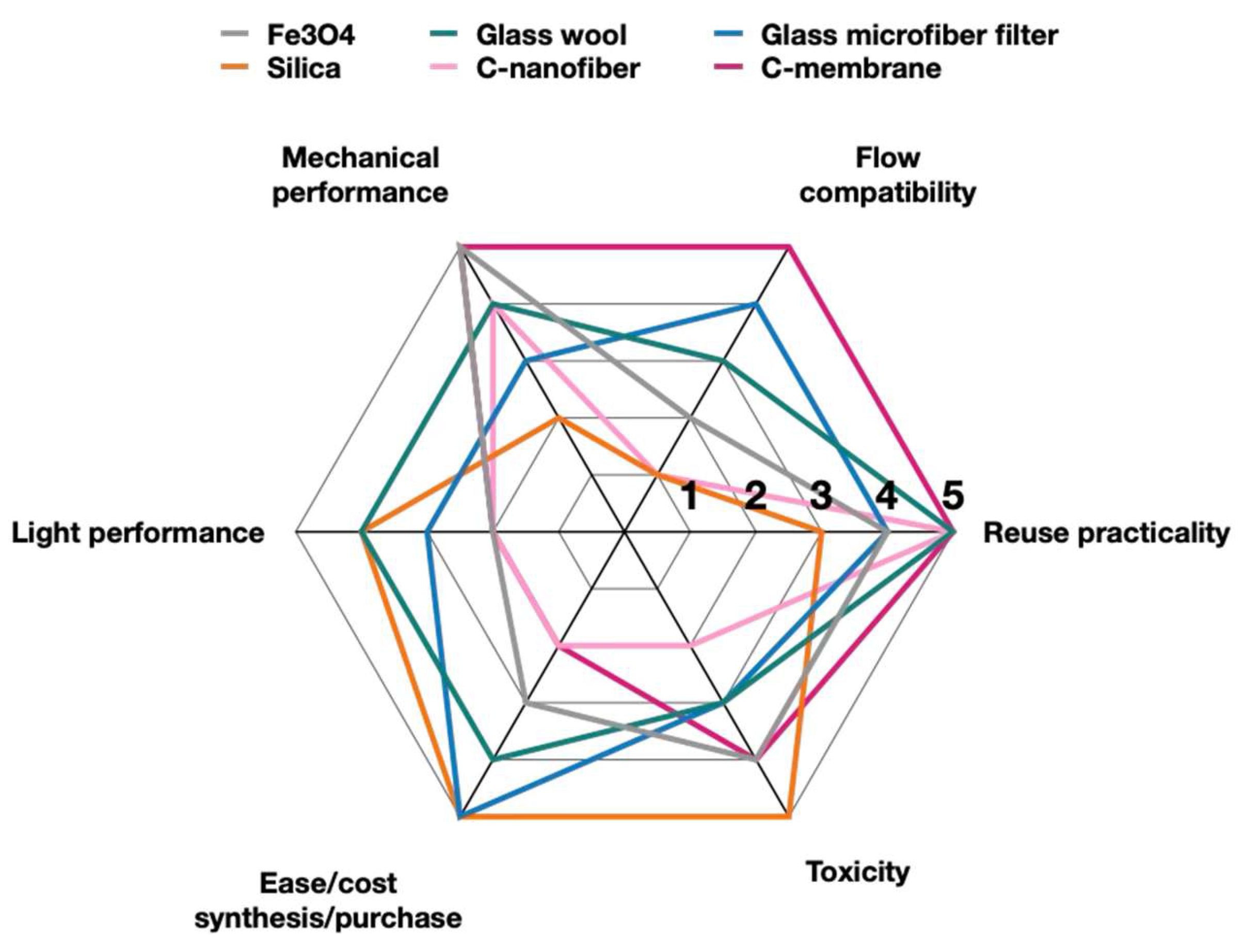

3.4. Looking for the Perfect Catalytic Couple: Different Supports

3.5. Developing Flow-Compatible Photocatalysts

4. Choosing Light and Light Sources

5. Dye Bleaching as a Quick Screening Test

5.1. Photocatalytic Dye Bleaching in the Literature

- Photolysis control: The dye solution is exposed to the same light source for a defined period (t) in the absence of the photocatalyst, to assess any direct photodegradation.

- Dark adsorption control: The dye is mixed with the photocatalyst and kept in the dark for the same duration (t) to evaluate dye adsorption on the catalyst surface.

- Thermal control: The system temperature is monitored and maintained constant—using a fan or cooling setup, for instance—to ensure that any observed dye degradation is not thermally induced.

5.2. Photocatalytic Dye Bleaching from Our Laboratory

6. Batch Photocatalytic Degradation of Drug Water Contaminants

6.1. Work Involving TiO2 and Related Catalysts

6.2. Work from Our Laboratories with TiO2 Materials

7. Batch Antibacterial Studies Using Powder Photocatalysts

7.1. Antibacterial Studies Using TiO2 in Any Form

7.2. Approaching Antibacterial Studies with TiO2 Forms Adaptable to Flow Catalysis

8. Flow Photocatalysis for the Treatment of Drug and Bacterial Contamination: A Promising Future for Point-of-Use Applications

9. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOC | Assimilable Organic Carbon |

| APTES | 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane |

| BG | Bandgap |

| CB | Conduction Band |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| lpcd | Liters Per Capita Per Day |

| MCLs | Maximum Contaminant Levels |

| PC | Photocatalyst |

| PEC | Photoelectrochemical |

| POU | Point of Use |

| PVC | Poly Vinyl Chloride |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SOCs | Synthetic Organic Compounds |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| VB | Valence Band |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Stackelberg, P.E.; Furlong, E.T.; Meyer, M.T.; Zaugg, S.D.; Henderson, A.K.; Reissman, D.B. Persistence of pharmaceutical compounds and other organic wastewater contaminants in a conventional drinking-water-treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 329, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farenhorst, A.; Li, R.; Jahan, M.; Tun, H.M.; Mi, R.; Amarakoon, I.; Kumar, A.; Khafipour, E. Bacteria in drinking water sources of a First Nation reserve in Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaimee, M.Z.; Sarjadi, M.S.; Rahman, M.L. Heavy Metals Removal from Water by Efficient Adsorbents. Water 2021, 13, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortúzar, M.; Esterhuizen, M.; Olicón-Hernández, D.R.; González-López, J.; Aranda, E. Pharmaceutical Pollution in Aquatic Environments: A Concise Review of Environmental Impacts and Bioremediation Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 869332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environment and Climate Change Canada. Canadian Environmental Sustainability Indicators: Water Quality in Canadian Rivers; Environment and Climate Change Canada: Gatineau, QC, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xiang, L.; Leung, K.S.-Y.; Elsner, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Pan, B.; Sun, H.; An, T.; Ying, G.; et al. Emerging contaminants: A One Health perspective. Innovation 2024, 5, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Drinking-Water Quality Guidelines. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/water-sanitation-and-health/water-safety-and-quality/drinking-water-quality-guidelines (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- EPA. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Comission. Drinking Water; Improving Access to Drinking Water for All. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/water/drinking-water_en (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Collier, R. Swallowing the pharmaceutical waters. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Kumar, D. Ibuprofen as an emerging organic contaminant in environment, distribution and remediation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, R. Developments in Surface Contamination and Cleaning; Kohli, R., Mittal, K.L., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 121–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, F.C.; Fish, K.E.; Boxall, J.B. Assimilable organic carbon cycling within drinking water distribution systems. Water Res. 2021, 198, 117147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, D.A.; Stewart, J.R. Microbial Indicators of Fecal Pollution: Recent Progress and Challenges in Assessing Water Quality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Yu, H.-Q. Mineralization or Polymerization: That Is the Question. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2024, 58, 11205–11208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, M.; Jones, E.R.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; van Vliet, M.T.H. Global energy consumption of water treatment technologies. Water Res. 2025, 277, 123245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazal, H.; Koumaki, E.; Hoslett, J.; Malamis, S.; Katsou, E.; Barcelo, D.; Jouhara, H. Insights into current physical, chemical and hybrid technologies used for the treatment of wastewater contaminated with pharmaceuticals. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, B.; Sabumon, P.C. A comprehensive review on biodegradation of azo dye mixtures, metabolite profiling with health implications and removal strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaei, M.; da Silva, D.R.C.; Rutajoga, N.; Currie, S.; Li, Y.; Vallieres, M.; Silvero, M.J.; Joshi, N.; Wang, B.; Scaiano, J.C. Innovative Black TiO2 Photocatalyst for Effective Water Remediation Under Visible Light Illumination Using Flow Systems. Catalysts 2024, 14, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Human Rights to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation: Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/821067?v=pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Howard, G.; Bartram, J.; Williams, A.; Overbo, A.; Fuente, D.; Geere, J.-A. Domestic Water Quantity, Service Level and Health, Geneva, Switzerland. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/ca623971-c9ee-4a72-9f60-f2a389ffb5c7/content (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Reed, B.; Reed, B. WHO Technical Note No. 9: How Much Water is Needed. Loughborough University. 2013. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17028/rd.lboro.27984446.v1 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rajaraman, T.S.; Parikh, S.P.; Gandhi, V.G. Black TiO2: A review of its properties and conflicting trends. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 389, 123918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinu, R.; Madras, G. Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Through Nanotechnology; Zang, L., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 625–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Gao, S.-P. The Stability, Electronic Structure, and Optical Property of TiO2 Polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 11385–11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New understanding of the difference of photocatalytic activity among anatase, rutile and brookite TiO2. PCCP 2014, 16, 20382–20386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dette, C.; Pérez-Osorio, M.A.; Kley, C.S.; Punke, P.; Patrick, C.E.; Jacobson, P.; Giustino, F.; Jung, S.J.; Kern, K. TiO2 Anatase with a Bandgap in the Visible Region. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 6533–6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xie, W.; Wei, Z. Synthesis of black TiO2 with efficient visible-light photocatalytic activity by ultraviolet light irradiation and low temperature annealing. Mat. Res. Bull. 2018, 98, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Suhail, M.; Alothman, Z.A.; Alwarthan, A. Recent advances in syntheses, properties and applications of TiO2 nanostructures. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 30125–30147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Marcus, M.A.; Wang, W.-C.; Oyler, N.A.; Grass, M.E.; Mao, B.; Glans, P.-A.; Yu, P.Y.; et al. Properties of Disorder-Engineered Black Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles through Hydrogenation. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, R.V.; Gummaluri, V.S.; Matham, M.V.; C, V. A review on optical bandgap engineering in TiO2 nanostructures via doping and intrinsic vacancy modulation towards visible light applications. J. Phys. D 2022, 55, 313003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, S.; Mao, S.S. Black TiO2 for solar hydrogen conversion. J. Mater. 2017, 3, 96–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G.; Yin, H.; Yang, C.; Cui, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Lin, T.; Huang, F. Black Titania for Superior Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production and Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2614–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. A new approach to prepare Ti3+ self-doped TiO2 via NaBH4 reduction and hydrochloric acid treatment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 160–161, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbatov, S.O.; Modin, E.; Puzikov, V.; Tonkaev, P.; Storozhenko, D.; Sergeev, A.; Mintcheva, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Tarasenka, N.N.; Chuvilin, A.; et al. Black Au-Decorated TiO2 Produced via Laser Ablation in Liquid. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfac. 2021, 13, 6522–6531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, P.S.; Patil, S.B.; Ganganagappa, N.; Reddy, K.R.; Raghu, A.V.; Reddy, C.V. Recent progress in metal-doped TiO2, non-metal doped/codoped TiO2 and TiO2 nanostructured hybrids for enhanced photocatalysis. Int. J. Hydr. Ener. 2020, 45, 7764–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Khan, M.M.; Ansari, M.O.; Cho, M.H. Nitrogen-doped titanium dioxide (N-doped TiO2) for visible light photocatalysis. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3000–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cao, A.; Chen, L.; Lv, K.; Wu, T.; Deng, K. One-step topological preparation of carbon doped and coated TiO2 hollow nanocubes for synergistically enhanced visible photodegradation activity. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 21431–21443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Lin, S. First-principles study on transition metal-doped anatase TiO2. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.-G.; Liu, A.-D.; Huang, M.-D.; Liao, B.; Wu, X.-L. First-Principles Band Calculations on Electronic Structures of Ag-Doped Rutile and Anatase TiO2. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2009, 26, 077106. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Du, J. First-principles study of electronic structures and optical properties of Cu, Ag, and Au-doped anatase TiO2. Phys. B Cond. Mat. 2012, 407, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delegan, N.; Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P.; El Khakani, M.A. Bandgap tailoring of in-situ nitrogen-doped TiO2 sputtered films intended for electrophotocatalytic applications under solar light. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 153510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwag, E.H.; Moon, S.Y.; Mondal, I.; Park, J.Y. Influence of carbon doping concentration on photoelectrochemical activity of TiO2 nanotube arrays under water oxidation. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2019, 9, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Wu, G.; Chen, P.; Zheng, H.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, H. Optimization of Boron Doped TiO2 as an Efficient Visible Light-Driven Photocatalyst for Organic Dye Degradation With High Reusability. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Ahmed, A.; Alam, U.; Uddin, I.; Tripathi, P.; Muneer, M. Enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of Ag-doped TiO2 nanoparticles under visible light. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2018, 212, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wen, W.; Qian, X.-Y.; Liu, J.-B.; Wu, J.-M. UV and visible light photocatalytic activity of Au/TiO2 nanoforests with Anatase/Rutile phase junctions and controlled Au locations. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rady, A.A.; Abd El-Sadek, M.; El-Sayed Breky, M.; Assaf, F. Characterization and Photocatalytic Efficiency of Palladium Doped-TiO2 Nanoparticles. Adv. Nanopart. 2013, 2, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshay, V.R.; Arun, B.; Mandal, G.; Mutta, G.R.; Chanda, A.; Vasundhara, M. Observation of Optical Band-Gap Narrowing and Enhanced Magnetic Moment in Co-Doped Sol–Gel-Derived Anatase TiO2 Nanocrystals. J. Phys.Chem. C 2018, 122, 26592–26604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Ganguly, P.; Rhatigan, S.; Kumaravel, V.; Byrne, C.; Hinder, S.J.; Bartlett, J.; Nolan, M.; Pillai, S.C. Cu-Doped TiO2: Visible Light Assisted Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Activity. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aware, D.V.; Jadhav, S.S. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic applications of Zn-doped TiO2 nanoparticles by sol–gel method. Appl. Nanosci. 2016, 6, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.D.; Kant, C.; Sharma, C.P.; Pandey, R.R.; Saini, K.K. Bandgap modification of TiO2 sol–gel films by Fe and Ni doping. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Tech. 2011, 58, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.E.; Khan, M.M.; Min, B.-K.; Cho, M.H. Microbial fuel cell assisted band gap narrowed TiO2 for visible light-induced photocatalytic activities and power generation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lima, D.Q.; Lee, I.; Zaera, F.; Chi, M.; Yin, Y. A Highly Active Titanium Dioxide Based Visible-Light Photocatalyst with Nonmetal Doping and Plasmonic Metal Decoration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 7088–7092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology: Volume 3: Environmental Toxicology; Luch, A., Ed.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Fallah, A.; Jamshidi, M. A Review of Synthesis Methods, Modifications, and Mechanisms of ZnO/TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Photodegradation of Contaminants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25457–25492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Thakur, P.R.; Sharma, G.; Naushad, M.; Rana, A.; Mola, G.T.; Stadler, F.J. Carbon nitride, metal nitrides, phosphides, chalcogenides, perovskites and carbides nanophotocatalysts for environmental applications. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 655–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Sardar, S.; Mumtaz, A. Mechanistic investigations of emerging type-II, Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic applications—A review. J. Alloys Comp. 2024, 1003, 175683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havryliuk, O.; Rathee, G.; Blair, J.; Hovorukha, V.; Tashyrev, O.; Morató, J.; Pérez, L.M.; Tzanov, T. Unveiling the Potential of CuO and Cu2O Nanoparticles against Novel Copper-Resistant Pseudomonas Strains: An In-Depth Comparison. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, J.; Sun, H.; Guo, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. In situ Growth of Cu2O/CuO Nanosheets on Cu Coating Carbon Cloths as a Binder-Free Electrode for Asymmetric Supercapacitors. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, T.; Visibile, A.; Busch, M.; He, X.; Wojtyla, S.; Rondinini, S.; Minguzzi, A.; Vertova, A. Copper Oxide-Based Photocatalysts and Photocathodes: Fundamentals and Recent Advances. Molecules 2021, 26, 7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuntithavornwat, S.; Saisawang, C.; Ratvijitvech, T.; Watthanaphanit, A.; Hunsom, M.; Kannan, A.M. Recent development of black TiO2 nanoparticles for photocatalytic H2 production: An extensive review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 55, 1559–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serov, D.A.; Gritsaeva, A.V.; Yanbaev, F.M.; Simakin, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V. Review of Antimicrobial Properties of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.; Ullah, R.; Butt, A.M.; Gohar, N.D. Strategies of making TiO2 and ZnO visible light active. J. Hazard. Mat. 2009, 170, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Karthikeyan, S.; Lee, A.F. g-C3N4-Based Nanomaterials for Visible Light-Driven Photocatalysis. Catalysts 2018, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Mohamed, A.A. Unveiling the photocatalytic potential of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4): A state-of-the-art review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25629–25662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolod, K.R.; Hernández, S.; Russo, N. Recent Advances in the BiVO4 Photocatalyst for Sun-Driven Water Oxidation: Top-Performing Photoanodes and Scale-Up Challenges. Catalysts 2017, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, A.; Khan, H.; Alzahrani, A.; Dan’azumi, S. Synthesis and characterization of tungsten trioxide (WO3) as photocatalyst against wastewater pollutants. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F.; Salim, E.; Hassan, A. Monoclinic tungsten trioxide (WO3) thin films using spraying pyrolysis: Electrical, structural and stoichiometric ratio at different molarity. Digest J. Nanomat. Biostr. 2022, 17, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.J.; Liu, G.; Moniz, S.J.A.; Bi, Y.; Beale, A.M.; Ye, J.; Tang, J. Efficient visible driven photocatalyst, silver phosphate: Performance, understanding and perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7808–7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamirat, A.G.; Rick, J.; Dubale, A.A.; Su, W.-N.; Hwang, B.-J. Using hematite for photoelectrochemical water splitting: A review of current progress and challenges. Nanoscale Horiz. 2016, 1, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, H. Cadmium sulfide nanoparticles compositing with chitosan and metal-organic framework: Enhanced photostability and increased carbon dioxide reduction. Adv. Comp. Hybrid Mater. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A.; Iervolino, G. Synthesis and Application of Innovative and Environmentally Friendly Photocatalysts: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaji, K.; Sridharan, K.; Kirubakaran, D.D.; Velusamy, J.; Emadian, S.S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Devadoss, A.; Nagarajan, S.; Das, S.; Pitchaimuthu, S. Biofunctionalized CdS Quantum Dots: A Case Study on Nanomaterial Toxicity in the Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment Process. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 19413–19424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musial, J.; Krakowiak, R.; Mlynarczyk, D.T.; Goslinski, T.; Stanisz, B.J. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Food and Personal Care Products—What Do We Know about Their Safety? Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Fu, Y. Large-Scale Synthesis of TiO2 Nanospindle by Liquid Phase Method for Photocatalytic Sewage Treatment. Ind. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, M.-J.; Grieken, R.V.; Aguado, J.; Marugán, J. Role of the support on the activity of silica-supported TiO2 photocatalysts: Structure of the TiO2/SBA-15 photocatalysts. Catal. Today 2005, 101, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, J. An efficient, stable and reusable polymer/TiO2 photocatalytic membrane for aqueous pollution treatment. J. Mat. Sci. 2021, 56, 11335–11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zeng, N.; Dan, Y.; Jiang, L. Covalent immobilization of TiO2 within macroporous polymer monolith as a facilely recyclable photocatalyst for water decontamination. Coll. Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.R.C.; Mapukata, S.; Currie, S.; Kitos, A.A.; Lanterna, A.E.; Nyokong, T.; Scaiano, J.C. Fibrous TiO2 Alternatives for Semiconductor-Based Catalysts for Photocatalytic Water Remediation Involving Organic Contaminants. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 21585–21593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Liman, R.A.D.; Ruallo, J.M.S.; Villaflores, O.B.; Ger, T.-R.; Hsiao, C.-D. Potential Toxicity of Iron Oxide Magnetic Nanoparticles: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksoud, M.I.A.A.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farrell, C.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.A.H.; Rooney, D.W.; Osman, A.I. Insight on water remediation application using magnetic nanomaterials and biosorbents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 403, 213096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Langer, A.M.; Nolan, R.P. A Risk Assessment for Exposure to Glass Wool. Reg. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1999, 30, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Elhage, A.; Wang, B.; Marina, N.; Marin, M.L.; Cruz, M.; Lanterna, A.E.; Scaiano, J.C. Glass wool: A novel support for heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6844–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Canada and Health Canada. Mineral Fibres (Man-Made Vitreous Fibres); Environment Canada and Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- De Ceglie, C.; Pal, S.; Murgolo, S.; Licciulli, A.; Mascolo, G. Investigation of Photocatalysis by Mesoporous Titanium Dioxide Supported on Glass Fibers as an Integrated Technology for Water Remediation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Janjua, T.I.; Cao, Y.; Kleitz, F.; Linden, M.; Yu, C.; Popat, A. Silica nanoparticles: A review of their safety and current strategies to overcome biological barriers. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2023, 203, 115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.; Ojha, G.P.; Acharya, J.; Park, M. Ag3PO4-TiO2-Carbon nanofiber Composite: An efficient Visible-light photocatalyst obtained from electrospinning and hydrothermal methods. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2021, 276, 119400. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, A.; Wick, P.; Koehler, A.; Schmid, K.; Som, C. Reviewing the Environmental and Human Health Knowledge Base of Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Health Persp. 2007, 115, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, V.; Bakshi, B.R.; Lee, L.J. Carbon Nanofiber Production. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 12, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, F.; Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, H.; et al. TiO2/Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B under Simulated Sunlight. ACS Appl. Nano Mat. 2019, 2, 7255–7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliwan, T.; Hu, J. Release of microplastics from polymeric ultrafiltration membrane system for drinking water treatment under different operating conditions. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Song, L.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L. Preparation of TiO2/C3N4 heterojunctions on carbon-fiber cloth as efficient filter-membrane-shaped photocatalyst for removing various pollutants from the flowing wastewater. J. Coll. Interf. Sci. 2018, 532, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Bourgonje, C.R.; Scaiano, J.C. Fiber-glass supported catalysis: Real-time, high-resolution visualization of active palladium catalytic centers during the reduction of nitro compounds. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2023, 13, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.J.; He, V.; Scaiano, J.C.; Silvero C, M.J. Photoinduced Transport and Activation of Polymer-Embedded Silver on Rice Husk Silica Nanoparticles for a Reusable Antimicrobial Surface. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.; Cajka, B.; Scaiano, J.C. Comparison of Composite Materials Designed to Optimize Heterogeneous Decatungstate Oxidative Photocatalysis. Molecules 2025, 30, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaiano, J.C.T. Photochemistry Essentials; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, M.S.; Cadet, J.; Di Mascio, P.; Ghogare, A.A.; Greer, A.; Hamblin, M.R.; Lorente, C.; Nunez, S.C.; Ribeiro, M.S.; Thomas, A.H.; et al. Type I and Type II Photosensitized Oxidation Reactions: Guidelines and Mechanistic Pathways. Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, C.S. Type I and Type II Mechanisms of Photodynamic Action. ACS Symp. Ser. 1987, 339, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Duan, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Cai, W.; Zhao, Z. Environmental Impacts and Biological Technologies Toward Sustainable Treatment of Textile Dyeing Wastewater: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, D.M.; Tudor, C.; Petrariu, R. The Textile Industry and Sustainable Development: A Holt–Winters Forecasting Investigation for the Eastern European Area. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, F.; Helman, W.P.; Ross, A.B. Quantum Yields for the Photosensitized Formation of the Lowest Electronically Excited Singlet State of Molecular Oxygen in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1993, 22, 113–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmy, A.V.; Indujalekshmi, J.; Chithra, S.; Anandakumar, V.M.; Biju, V. Elucidation of augmented visible-light photocatalysis in surface-modified coloured rutile TiO2. J. Solid State Chem. 2026, 353, 125685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Rahman, N.; Prasannan, A.; Ganiyeva, K.; Chakrabortty, S.; Sangaraju, S. Phase transition and bandgap modulation in TiO2 nanostructures for enhanced visible-light activity and environmental applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, W.; Matalkeh, M.; Al Soubaihi, R.M.; Elzatahry, A.; Saoud, K.M. Visible Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye and Pharmaceutical Wastes over Ternary NiO/Ag/TiO2 Heterojunction. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 40063–40077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simanjuntak, M.; Joni, I.M.; Faizal, F.; Gultom, N.S.; Kuo, D.-H.; Panatarani, C. Photoluminescence of oxygen vacancy-rich nano-TiO2 photocatalyst for methylene blue color degradation. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 320, 118401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Garza, A.R.; Zeghioud, H.; Benítez-Rico, A.; Romero-Nuñez, A.; Djelal, H.; Chávez-Miyauchi, T.E.; Guillén-Cervantes, J.Á. Visible LED active photocatalyst based on cerium doped titania for Rhodamine B degradation: Radical’s contribution, stability and response surface methodology optimization. Mat. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 2024, 176, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-Y.; Han, S.-D.; Liu, J.-G.; Sun, L.-Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Wei, Q.; Cui, S.-P. Controllable preparation and photocatalytic performance of hollow hierarchical porous TiO2/Ag composite microspheres. Coll. Surf. A 2023, 658, 130707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmy, A.V.; Mahesh, A.; Anandakumar, V.M.; Biju, V. Revealing the role of defect-induced trap levels in sol–gel-derived TiO2 samples and the synergistic effect of a mixed phase in photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2024, 185, 111774. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, C.H.; Fu, C.-C.; Juang, R.-S. Degradation of methylene blue and methyl orange by palladium-doped TiO2 photocatalysis for water reuse: Efficiency and degradation pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi-Maleh, H.; Kumar, B.G.; Rajendran, S.; Qin, J.; Vadivel, S.; Durgalakshmi, D.; Gracia, F.; Soto-Moscoso, M.; Orooji, Y.; Karimi, F. Tuning of metal oxides photocatalytic performance using Ag nanoparticles integration. J. Molec. Liq. 2020, 314, 113588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.-K.; Kumar, S.; Isaacs, M.A.; Lee, A.F.; Karthikeyan, S. Cobalt promoted TiO2/GO for the photocatalytic degradation of oxytetracycline and Congo Red. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 201, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Lin, Y.; Hu, Y.H. Excellent photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline over black anatase-TiO2 under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Bai, H.; Liu, J.; Hu, D.; Fan, J.; Shen, H. Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance of black TiO2/SnO2 nanoparticles. J. Alloy Comp. 2023, 960, 170672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xie, W. A Facile Approach to Prepare Black TiO2 with Oxygen Vacancy for Enhancing Photocatalytic Activity. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachmantyo, R.; Afkauni, A.A.; Reinaldo, R.; Zhang, L.; Arramel, A.; Birowosuto, M.D.; Wibowo, A.; Judawisastra, H. Fabrication of black TiO2 through microwave heating for visible light-driven photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine 6G. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 3003–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veziroglu, S.; Obermann, A.-L.; Ullrich, M.; Hussain, M.; Kamp, M.; Kienle, L.; Leißner, T.; Rubahn, H.-G.; Polonskyi, O.; Strunskus, T.; et al. Photodeposition of Au Nanoclusters for Enhanced Photocatalytic Dye Degradation over TiO2 Thin Film. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfac. 2020, 12, 14983–14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, P.C.L.; Mortari, S.R.; Vizzotto, B.S.; Chuy, G.; Santos, C.D.; Brum, L.F.W.; da Silva, W.L. Iron oxide nanocatalyst with titanium and silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity on the degradation of Rhodamine B dye. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qutub, N.; Singh, P.; Sabir, S.; Sagadevan, S.; Oh, W.-C. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of Acid Blue dye using CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalanta, F.; Widiyandari, H.; Kartikowati, C.W.; Arif, A.F.; Filardli, A.M.I.; Arutanti, O. Green-synthesized Schottky junction Ni-TiOx suboxide photocatalyst enriched with oxygen vacancies for solar-driven degradation of emerging contaminants. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2025, 77, 108446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalane, C.M.; Priyadharsini, G.M.A.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Jothi, A.I.; Simiyon, G.G. Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 doped cobalt ferrite nanoparticles via microwave method: Investigation of photocatalytic performance of congo red degradation dye. Surf. Interfac. 2021, 25, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landge, V.K.; Huang, C.-M.; Hakke, V.S.; Sonawane, S.H.; Manickam, S.; Hsieh, M.-C. Solar-Energy-Driven Cu-ZnO/TiO2 Nanocomposite Photocatalyst for the Rapid Degradation of Congo Red Azo Dye. Catalysts 2022, 12, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yu, H.; Qin, Y.; Di, Y.; Jia, H.; Li, F.; Liu, J. Hollow TiO2–SiO2 Nanospheres for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. ACS Appl. Nano Mat. 2024, 7, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Geng, C.; Tang, J. Hollow Fe3+-Doped Anatase Titanium Dioxide Nanosphere for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. ACS Appl. Nano Mat. 2023, 6, 18999–19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindelo, A.; Britton, J.; Lanterna, A.E.; Scaiano, J.C.; Nyokong, T. Decoration of glass wool with zinc (II) phthalocyanine for the photocatalytic transformation of methyl orange. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 432, 114127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yu, L.; Kousar, S.; Khalid, W.; Maqbool, Z.; Aziz, A.; Arshad, M.S.; Aadil, R.M.; Trif, M.; Riaz, S.; et al. Crocin: Functional characteristics, extraction, food applications and efficacy against brain related disorders. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubelka, P. New Contributions to the Optics of Intensely Light-Scattering Materials. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1948, 38, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohko, Y.; Iuchi, K.-I.; Niwa, C.; Tatsuma, T.; Nakashima, T.; Iguchi, T.; Kubota, Y.; Fujishima, A. 17β-Estradiol Degradation by TiO2 Photocatalysis as a Means of Reducing Estrogenic Activity. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2002, 36, 4175–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontistis, Z.; Daskalaki, V.M.; Hapeshi, E.; Drosou, C.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Xekoukoulotakis, N.P.; Mantzavinos, D. Photocatalytic (UV-A/TiO2) degradation of 17α-ethynylestradiol in environmental matrices: Experimental studies and artificial neural network modeling. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 240, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzzeka, C.; Goldoni, J.; de Paula de Oliveira, J.D.R.; Lenzi, G.G.; Bagatini, M.D.; Colpini, L.M.S. Photocatalytic action of Ag/TiO2 nanoparticles to emerging pollutants degradation: A comprehensive review. Sust. Chem. Environ. 2024, 8, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapukata, S.; Hainer, A.S.; Lanterna, A.E.; Scaiano, J.C.; Nyokong, T. Decorated titania fibers as photocatalysts for hydrogen generation and organic matter degradation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 388, 112185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutajoga, N.; Velez, V.; Scaiano, J.C. Scavenging of photogenerated holes in TiO2-based catalysts uniquely controls pollutant degradation and hydrogen formation under UVA or visible irradiation. Catal. Sci. Tech. 2025, 15, 5886–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.R.C. Unveiling the Versatility of Titanium and Iron Nanostructures: Applications Across Medicine, Environmental Remediation and Organic Reactions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, J.; Cho, J.; Mishra, Y.K. Photocatalytic TiO2 nanomaterials as potential antimicrobial and antiviral agents: Scope against blocking the SARS-CoV-2 spread. Micro Nano Eng. 2022, 14, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.B.; Haddad, Y.; Kosaristanova, L.; Smerkova, K. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: Recent progress in antimicrobial applications. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotech. 2023, 15, e1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, L.F.A.A.; Annushrie, A.; Namasivayam, S.K.R. Anti bacterial efficacy of photo catalytic active titanium di oxide (TiO2) nanoparticles synthesized via green science principles against food spoilage pathogenic bacteria. Microbe 2025, 7, 100331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S. Bactericidal Properties of Blackened Titanium Dioxide on Glass Filter: A Proof of Concept for Water Decontamination. Master’s Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Navidpour, A.H.; Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L. Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Residues from Water and Sewage Effluent Using Different TiO2 Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufner, L.; Aresté-Saló, L.; Graells, M.; Pérez-Moya, M.; Kern, F.; Rheinheimer, W. Photocatalytic degradation of paracetamol on immobilized TiO2 in a low-tech reactor by solar light for water treatment. Open Ceram. 2024, 18, 100599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.-B.; Du, M.-R.; Liu, K.-K.; Zhou, R.; Ma, R.-N.; Jiao, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Shan, C.-X. Hydrophilic ZnO Nanoparticles@Calcium Alginate Composite for Water Purification. ACS Appl. Mat. Interf. 2020, 12, 13305–13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.; Miyazaki, Y.; Sugasawa, M.; Yang, Y.; Negishi, N. Antibacterial silver-loaded TiO2 ceramic photocatalyst for water purification. J. Water Proc. Eng. 2022, 50, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovski, V.; Rybalchenko, N.; Petrik, I.; Kryvokhyzha, K.; Vasiljev, A.; Vasyliev, T. Surface Plasmon Resonance Influence on the Antibacterial Effect of a Nanostructured Gold Surface. e-J. Surf. Sci. Nanotech. 2025, 23, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Qian, W.; El-Sayed, M.A. Cancer Cell Imaging and Photothermal Therapy in the Near-Infrared Region by Using Gold Nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2115–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhode, P.N.; Awatade, S.M.; Prakash, C.; Shelare, S.D.; Marghade, D.; Gajghate, S.S.; Noor, M.M.; Dennison, M.S. An integrated AI-driven framework for maximizing the efficiency of heterostructured nanomaterials in photocatalytic hydrogen production. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Contaminant | Type | Primary Source/Use | WHO Guidelines [7] | US EPA Limits [8] | EU Limits [9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | VOC | Fuel/Gasoline, Solvents | 10 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Carbon Tetrachloride | VOC | Industrial Solvent, Refrigerant | 4 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Vinyl Chloride | VOC | Plastic Manufacturing (PVC) | 0.3 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 1,2-Dichloroethane | VOC | Vinyl Chloride Production, Solvents | 30 | 5 | 3.0 |

| p-Dichlorobenzene | VOC | Mothballs, Air Fresheners | 300 | 75 | 0.5 |

| Trichloroethylene (TCE) | VOC | Industrial Solvent, Degreaser | 70 | 5 | 10 (for tetrachloroethene and trichloroethene sum) |

| Atrazine | SOC | Herbicide (Agricultural Runoff) | 100 | 3 | 0.1 (for individual pesticides) |

| Alachlor | SOC | Herbicide (Agricultural Runoff) | 20 | 2 | 0.1 (for individual pesticides) |

| Total Trihalomethanes (TTHMs) | VOC | Chlorination Byproduct | 100 | 80 | 100 |

| Doped TiO2 | Bandgap (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pristine TiO2 | 3.2 | [27] |

| N2-doped TiO2 | 2.30 | [42] |

| C-doped TiO2 | 2.75 | [43] |

| B-doped TiO2 | 2.85 | [44] |

| Ag-doped TiO2 | 2.60 | [45] |

| Au-doped TiO2 | 2.61 | [46] |

| Pd-doped TiO2 | 3.06 | [47] |

| Co-doped TiO2 | 2.24 | [48] |

| Cu-doped TiO2 | 2.80 | [49] |

| Zn-doped TiO2 | 2.83 | [50] |

| Ni-doped TiO2 | 2.90 | [51] |

| Fe-doped TiO2 | 2.73 | [51] |

| Photo-Catalyst | BG (eV) | Limitations | Advantages | Enhancement Strategies | Applications | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | ~3.2 | Limited visible light activity | Widely studied, stable, effective under UV light | Doping, surface modification, heterojunctions | Water remediation and bacterial inactivation | [19,55,62,63] |

| ZnO | ~3.2 | Similar UV-only limitation as TiO2, photocorrosion under acidic conditions | High electron mobility, UV stability, ROS generation | Doping, surface modification, heterojunctions | Dye, pharmaceutical, pesticide degradation | [56,64] |

| g-C3N4 | ~2.7 | Low quantum efficiency, fast recombination | Visible light-active, metal-free, stable, basic sites | Bandgap engineering, heterojunctions, oxidant coupling (e.g., H2O2, persulfate) | Water splitting, CO2 reduction, organic degradation | [65,66] |

| BiVO4 | ~2.4 | Poor charge mobility, recombination | Visible light-active, solar-driven PEC applications | Doping, heterojunctions, MXene composites | Pollutant degradation, water splitting | [67] |

| WO3 | ~2.6 | Fast electron–hole recombination, limited conduction band position | Stable, Earth-abundant, visible light-active | Doping, heterojunctions, oxygen vacancy engineering | Dye and pharmaceutical degradation | [68,69] |

| Ag3PO4 | ~2.4 | Photocorrosion, poor recyclability | High quantum efficiency, strong oxidant | Doping, noble metal deposition, magnetic supports | Pollutant degradation, water oxidation | [70] |

| α-Fe2O3 | ~2.1 | Poor conductivity, recombination | Non-toxic, inexpensive, abundant | Doping, morphology control, composites (e.g., Fe2O3–g-C3N4) | Dye degradation, hydrogen production | [71] |

| Cu2O/CuO | ~2.0–2.2 | Charge recombination, photodegradation | Low-cost, visible light-active, ROS generation | Heterojunctions, graphene oxide decoration, surface engineering | Decentralized water treatment, dye and drug degradation | [59,60,61] |

| CdS | ~2.4 | Cadmium toxicity, photocorrosion | Excellent solar-driven activity | Biofunctionalization, composites to reduce Cd2+ leaching | Water splitting, pollutant degradation | [72] |

| Reuse | Toxicity | Ease/Cost | Light | Mechanical | Flow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 NPs | 4 Magnetically separable. Surface can oxidize to Fe(III) after 3–10 cycles. | 4 Can produce ROS. Oxidizes to inert and biocompatible Fe(II) [81]. | 3 Safe, eco-friendly, and low-cost [82]. | 2 Absorbs visible light. Can compete with photocatalysts. | 5 Magnetic. Easy-to-decorate surface. | 2 Not flow-compatible, unless anchored by magnets. |

| Glass wool | 5 Easily separable. Washing surface can remove active sites (5–7 cycles). | 3 Microfibers can detach and potentially be ingested (high aspect ratio) [83]. | 4 Low-cost, widely available, easy to modify [84]. | 4 Highly scattering. | 4 Easy to decorate. Silanization-compatible. Shape-adaptable to setup. | 3 High flow rate challenge. |

| Glass microfiber filter (GMF) | 4 Separable from most matrices. Small fibers can be released (5–7 cycles). | 3 Microfibers can detach and potentially be ingested. Inert [85]. | 5 Low-cost and stable under irradiation [86]. | 3 Opaque, might affect light absorbance. | 3 Can accept large loads. High abrasion risk. | 4 Highly flexible, light-weight, thermally stable [86]. |

| Silica | 3 Catalyst loss possible during recycling. Efficacy can decrease after ~3 cycles. | 5 Inert and non-toxic at bulk or nanoscale [87]. | 5 Low cost for commercial silica. | 4 Good UV scatterer. | 2 Large surface area, inert. High abrasion risk. | 1 Powder. |

| Carbon nanofibers | 5 Electrospinning TiO2, decreases catalyst loss and increases reusability to >10 cycles [88]. | 2 High aspect ratio causes pulmonary issues. Can produce harmful ROS [89]. | 2 High energy requirements (electrospinning/CVD) [90]. | 2 Broad light absorption. | 4 Withstands flow stress. Flexible; adapts to reaction setups. | 1 Powder. |

| Carbon membranes | 5 Low separation from support. May lose active sites after multiple cycles (>10 cycles) [91]. | 4 Thin films; low risk of dissolution. May release microplastics. Inert [92]. | 2 High cost—electrospinning. | 2 Broad light absorption. | 5 Withstands high pressure gradients. Resistant to abrasion. | 5 Flexible [93]. |

| PC (Specific Sample) | BG (eV) | Dye | Degradation Efficiency | PC (mg/mL) | Light Source | Irradiance W-m−2 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colored rutile TiO2 (rR3) | 2.97 | MB | 68% in 90 min | 0.6 | White LED (400–700 nm) | 150 | [103] |

| TiO2 doped with Al3+/Al2+ and S6+ ions (X4) | 1.98 | MB | 96.4% in 150 min | 0.4 | Halogen lamp, 200 W | NR | [104] |

| Ternary NiO/Ag/TiO2 composite | 2.5 | MB | 93.2% in 60 min | 1 | Halogen lamp, 400 W (λf ≥ 400 nm) | 170 | [105] |

| Oxygen vacancy-rich nano-TiO2 (T150) | 2.65 | MB | 93.8% in 180 min | 0.2 | Direct sunlight | 104.5 Klux | [106] |

| Ce-doped TiO2 (7% of Ce doping of TiO2) | 2.42 | RhB | 70% in 150 min | 1.3 | 420 nm LED (7.5 W) | 20 | [107] |

| Hollow hierarchical porous TiO-Ag composite (HHPA6 (10:0.5)) | 3.08 | MO | 98.4% in 125 min | 1.25 | 15W lamp (λmax 395 nm) | NR | [108] |

| Sol–gel-derived TiO2 (T2) | 2.97 | MB | 99% in 75 min | 0.6 | Direct sunlight | 500–800 | [109] |

| Pd-doped TiO2 (0.5% Pd-TiO2) | 3.12 | MB, MO | 99.4% in 120 min (MB); 92.6% in 120 min (MO) | 1.0 | 100 W Hg lamp | 65 | [110] |

| Ag-TiO2 | 2.78 | MO | 86% in 180 min | 1.0 | Solar simulator 1.5 G | NR | [111] |

| Co3O4/TiO2/GO (2 wt% Co3O4/TiO2/GO-1) | 3.04 | CR | 91% in 90 min | 0.25 | 300 W Xe lamp (λf > 400 nm) | 1000 | [112] |

| Black TiO2 | 1.3 | TC | 66.6% in 240 min | 0.20 | 1000 W Xe lamp (λf > 400 nm) | 400 | [113] |

| Black TiO2/SnO2 (BTS3) | 2.55 | RhB | 96.6% in 90 min | 0.62 | 150 W Xe lamp (λf > 420 nm) | NR | [114] |

| Black TiO2 | NR | RhB, MB | >90% in 120 min (RhB); 70% in 220 min (MB) | 0.5 | 800 W Xe lamp (λf > 420 nm) | NR | [115] |

| Black TiO2 | 1.5 | Rh6G | 49.2% in 240 min | 0.3 | 100 W white LED 6500K | 9000 lumen | [116] |

| Au nanocluster-decorated TiO2 thin film | NR | MB | 90% in 120 min | 1 cm wafer in 6.5 mL solution | UV lamp (λpeak 365 nm) | 45 | [117] |

| Fe2O3-TiO2 (TiNP-Fe2O3) | 2.0 | RhB | 48.4% in 120 min | 1.41 mg/mL | Visible light (no details) | 202 | [118] |

| CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite | 3.5 | AB | 84% in 90 min | 1.0 | Halogen lamp (500 W) | 9500 lum | [119] |

| Ni-TiOx | 2.68 | RhB, MO, TC | 98.2% (RhB); 99.5% (MO); 93.5% (TC) in 120 min | 0.15 | Solar simulator | 1000 | [120] |

| TiO2-doped CoFe2O4 | 2.88 | CR | 99.9% in 250 min | 0.8 | 150 W metal halide lamp; λ > 400 nm | NR | [121] |

| Cu-ZnO/TiO2 nanocomp. (CZT-2) | 2.68 | CR | 100% in 20 min | 0.5 | Direct sunlight | NR | [122] |

| TiO2-SiO2 nanospheres | NR | RhB | 100% in 110 min | 0.8 | Xe lamp (300 W, λ < 390 nm) | NR | [123] |

| Fe−TiO2 hollow nanospheres (2% Fe−TiO2) | 3.04 | RhB | 95% in 115 min | 1.0 | Hg Lamp, XPA-Photoreactor 500 W | NR | [124] |

| Dye | Conc., µM | λmax (nm) | Rate, µM/min | LED | Irradiance W/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh6G | 21.0 | 527 | (0.62) ‡ | Green | 88.3 |

| Rh6G | 21.0 | 527 | 0.21 | White | 1420 |

| AzB | 32.7 | 646 | 0.23 | Green | 88.3 |

| AzB | 32.7 | 646 | 0.61 | White | 1420 |

| CrB | 26.0 | 626 | 0.030 | Green | 88.3 |

| CrB | 26.0 | 626 | 0.36 | White | 1420 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silvero C., M.J.; Ong, J.; Frank, C.J.; Rutajoga, N.; Joshi, N.; Cajka, B.; Didarataee, S.; Hamrahjoo, M.; Scaiano, J.C. Towards Flow Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Practical Approach to Point-of-Use Water Remediation Strategies. Catalysts 2026, 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010035

Silvero C. MJ, Ong J, Frank CJ, Rutajoga N, Joshi N, Cajka B, Didarataee S, Hamrahjoo M, Scaiano JC. Towards Flow Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Practical Approach to Point-of-Use Water Remediation Strategies. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilvero C., Maria Jazmin, Julia Ong, Carly J. Frank, Nelson Rutajoga, Neeraj Joshi, Benjamin Cajka, Saba Didarataee, Mahtab Hamrahjoo, and Juan C. Scaiano. 2026. "Towards Flow Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Practical Approach to Point-of-Use Water Remediation Strategies" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010035

APA StyleSilvero C., M. J., Ong, J., Frank, C. J., Rutajoga, N., Joshi, N., Cajka, B., Didarataee, S., Hamrahjoo, M., & Scaiano, J. C. (2026). Towards Flow Heterogeneous Photocatalysis as a Practical Approach to Point-of-Use Water Remediation Strategies. Catalysts, 16(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010035