Enhancing 1,5-Pentanediamine Productivity in Corynebacterium glutamicum with Improved Lysine and Glucose Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Construction of a PDA-Producing Strain via Strengthening the Lysine Synthesis Pathway

2.2. Design and Optimization of a PDA-Responsive Dynamic Regulatory Switch

2.3. Enhancing Precursor Lysine Production Using PDRS

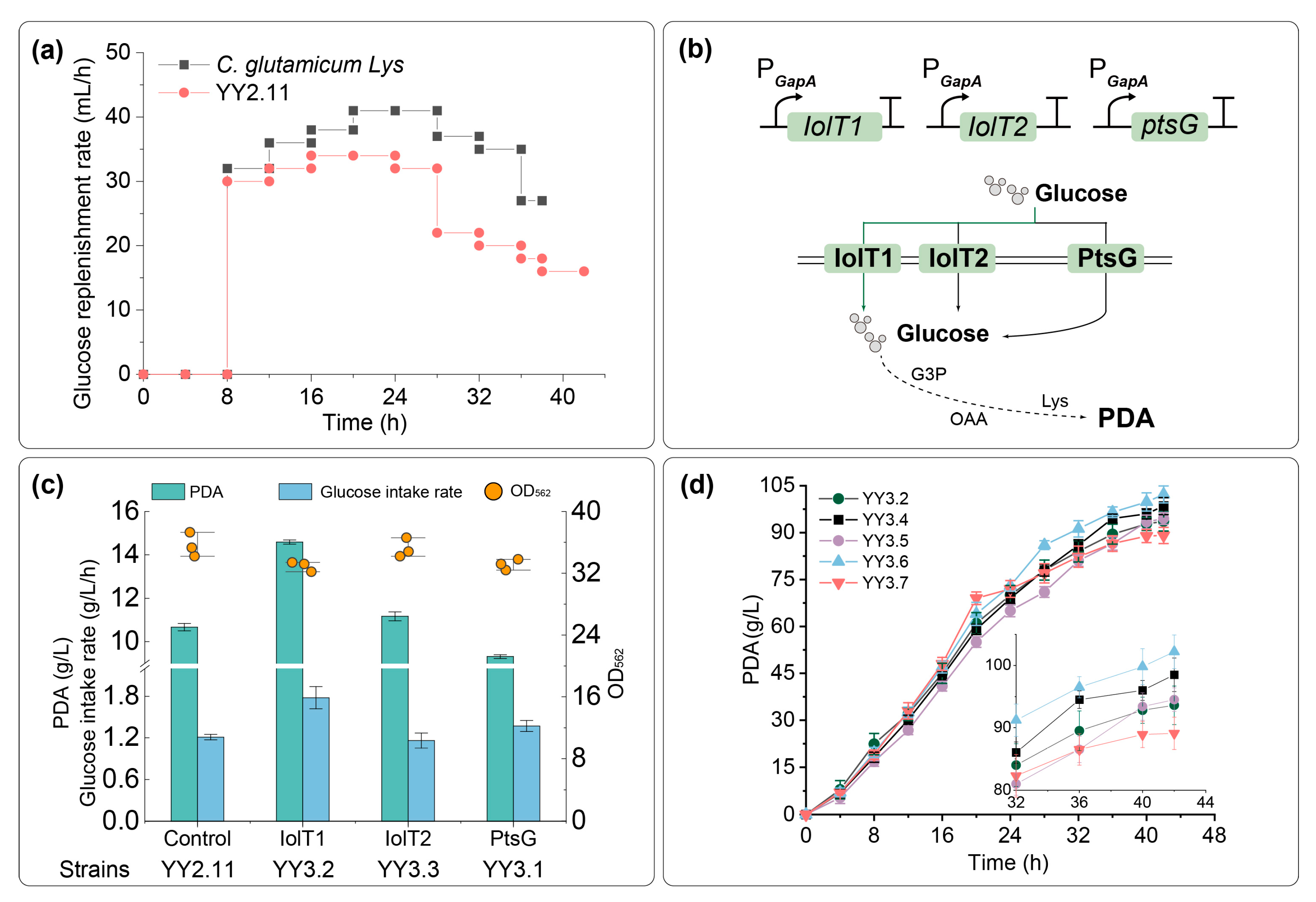

2.4. Increasing Glucose Uptake with PDRS

2.5. Fermentation Optimization for PDA Production

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains and Plasmids

4.2. Medium Composition

4.3. Culture Conditions

4.4. Quantitative PCR Analysis

4.5. Measurement of Fluorescence Intensity

4.6. Analytical Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buschke, N.; Becker, J.; Schafer, R.; Kiefer, P.; Biedendieck, R.; Wittmann, C. Systems metabolic engineering of xylose-utilizing Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of 1,5-diaminopentane. Biotechnol. J. 2013, 8, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.G.; Xia, X.X.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of cadaverine: A five carbon diamine. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 108, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, T.R.; Song, H.S.; Lee, S.M.; Park, S.L.; Lee, H.S.; Cho, J.Y.; Bhatia, S.K.; Gurav, R.; et al. Improvement of cadaverine production in whole cell system with baker’s yeast for cofactor regeneration. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 44, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, T.; Xu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. A novel co-production of cadaverine and succinic acid based on a thermal switch system in recombinant Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, D.; Yoo, S.M.; Chung, H.; Park, H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using synthetic small regulatory RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, R.; Wang, D.; Xiao, K.; Lin, F.; Kang, Y.Q.; Xia, X.; Zhou, X.; Hu, G. Combining directed evolution with high cell permeability for high-level cadaverine production in engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, e2300642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Han, Y.; Xu, S.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, K. Engineering RuBisCO-based shunt for improved cadaverine production in Escherichia coli. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 398, 130529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Hsu, K.-M.; Ting, W.-W.; Huang, S.-F.; Lin, H.-Y.; Li, S.-F.; Chang, J.-S.; Ng, I.S. Efficient biotransformation of L-lysine into cadaverine by strengthening pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent proteins in Escherichia coli with cold shock treatment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 161, 107659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Ye, L.; Yu, H. Enhanced thermal and alkaline stability of L-lysine decarboxylase CadA by combining directed evolution and computation-guided virtual screening. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Ma, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, P. Engineered production of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate in Escherichia coli BL21. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 52, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.Y.; Zhang, A.; Ma, D.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.Q. Enhancing pH stability of lysine decarboxylase via rational engineering and its application in cadaverine industrial production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 186, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, N.; Lu, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhang, A.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. Chitin biopolymer mediates self-sufficient biocatalyst of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and L-lysine decarboxylase. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 132030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Pu, Z.J.; Kang, H.; Mi, J.L.; Liu, S.M.; Qi, H.S.; Zhang, L. Zwitterionic peptides encircling-assisted enhanced catalytic performance of lysine decarboxylase for cadaverine biotransformation and mechanism analyses. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 251, 117447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zheng, T.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Q.; Chen, J.; Wu, F.; Chen, G.Q. Engineered Halomonas spp. for production of L-lysine and cadaverine. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 349, 126865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.B.; Choi, J.I. Production of cadaverine in recombinant Corynebacterium glutamicum overexpressing lysine decarboxylase (ldcc) and response regulator dr1558. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.; Yoo, S.M.; Yang, D.; Lee, S.Y. Broad-spectrum gene repression using scaffold engineering of synthetic sRNAs. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Ng, I.S. A direct enzymatic evaluation platform (DEEP) to fine-tuning pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent proteins for cadaverine production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.G.; Zhang, A.L.; Lu, X.D.; He, F.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Li, G.L.; Chen, K.Q.; Ouyang, P.K. An environmentally friendly strategy for cadaverine bio-production: In situ utilization of CO2 self-released from L-lysine decarboxylation for pH control. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 37, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; He, F.; Xu, S.; Chen, K.; Ouyang, P. Ameliorating end-product inhibition to improve cadaverine production in engineered Escherichia coli and its application in the synthesis of bio-based diisocyanates. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2021, 6, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T.; Baritugo, K.-A.; Hyun, S.M.; Khang, T.U.; Sohn, Y.J.; Kang, K.H.; Jo, S.Y.; Song, B.K.; Park, K.; Kim, I.-K.; et al. Development of metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum for enhanced production of cadaverine and its use for the synthesis of bio-polyamide 510. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 8, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kind, S.; Neubauer, S.; Becker, J.; Yamamoto, M.; Volkert, M.; Abendroth, G.; Zelder, O.; Wittmann, C. From zero to hero—Production of bio-based nylon from renewable resources using engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab. Eng. 2014, 25, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, J.; Liu, S.; Qi, H.; Huang, J.; Lan, X.; Zhang, L. Cellular engineering and biocatalysis strategies toward sustainable cadaverine production: State of the art and perspectives. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ji, X.; Ma, Z.; Lezyk, M.; Xue, Y.; Zhao, H. Green chemical and biological synthesis of cadaverine: Recent development and challenges. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 23922–23942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wu, Y.; Feng, T.; Shen, J.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chou, H.H.; Luo, X.; Keasling, J.D. Dynamic upregulation of the rate-limiting enzyme for valerolactam biosynthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Metab. Eng. 2023, 77, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itou, H.; Okada, U.; Suzuki, H.; Yao, M.; Wachi, M.; Watanabe, N.; Tanaka, I. The CGL2612 protein from Corynebacterium glutamicum is a drug resistance-related transcriptional repressor: Structural and functional analysis of a newly identified transcription factor from genomic DNA analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38711–38719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Zhai, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.-S.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Z. Fine-tuning multi-gene clusters via well-characterized gene expression regulatory elements: Case study of the arginine synthesis pathway in C. glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021, 10, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Joo, J.C.; Lee, E.; Hyun, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; Park, S.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Park, K. Characterization of a whole-cell biotransformation using a constitutive lysine decarboxylase from Escherichia coli for the high-level production of cadaverine from industrial grade L-lysine. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 185, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.J.; Kim, E.-J.; Lee, J.K. Physiological polyamines: Simple primordial stress molecules. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, A.E. Toxicity of polyamines and their metabolic products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 1782–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, J.; Gao, C. Engineering microorganisms to produce bio-based monomers: Progress and challenges. Fermentation 2023, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Qi, M.; Gao, C.; Ye, C.; Hu, G.; Song, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Engineering microbial cell viability for enhancing chemical production by second codon engineering. Metab. Eng. 2022, 73, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Luo, Q.; Guo, L.; Gao, C.; Xu, N.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Improving lysine production through construction of an Escherichia coli enzyme-constrained model. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; Gao, C. Metabolic engineering of plasmid-free Escherichia coli for enhanced glutarate biosynthesis from glucose. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 163077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Liang, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, X. An integrated cofactor and co-substrate recycling pathway for the biosynthesis of 1,5-pentanediol. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the high-level production of valerolactam, a nylon-5 monomer. Metab. Eng. 2023, 79, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qiao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Cheng, J.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, C.; et al. De novo designed protein guiding targeted protein degradation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komera, I.; Gao, C.; Guo, L.; Hu, G.; Chen, X.; Liu, L. Bifunctional optogenetic switch for improving shikimic acid production in E. coli. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Zhou, P.; Jiao, X.; Yao, Z.; Ye, L.; Yu, H. Fermentative production of Vitamin E tocotrienols in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under cold-shock-triggered temperature control. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Xie, W.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, L.; Yu, H. Development of a temperature-responsive yeast cell factory using engineered Gal4 as a protein switch. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018, 115, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Tang, W.; Guo, L.; Hu, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Improving succinate production by engineering oxygen-dependent dynamic pathway regulation in Escherichia coli. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf 2021, 2, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; He, Y.; Zhou, S.; Deng, Y. Dynamic regulation and cofactor engineering of Escherichia coli to enhance production of glycolate from corn stover hydrolysate. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 398, 130531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Song, W.; Ye, C.; Ding, Q.; Wei, W.; Hu, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L. Bifunctional optogenetic switch powered NADPH availability for improving L-Valine production in Escherichia coli. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 15103–15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, P.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, G.; Wu, J.; Gao, C.; et al. Systems metabolic engineering of Klebsiella pneumoniae for high-level 1,3-propanediol production. Metab. Eng. 2026, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Gao, C.; Song, L.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Song, W.; Wei, W.; Liu, L. Fine-tuning pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthesis in Escherichia coli for cadaverine production in minimal culture media. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Wen, T. Development of a lysine biosensor for the dynamic regulation of cadaverine biosynthesis in E. coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 2025, 24, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Gao, C.; Song, W.; Wei, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Chen, X. Reprogramming metabolic flux in Escherichia coli to enhance chondroitin production. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Song, W.; Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Gao, C. Engineering Escherichia coli asymmetry distribution-based synthetic consortium for shikimate production. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 3230–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Liu, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, J.; Song, W.; Hu, G.; Wei, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; et al. Designing autonomous biological switches to rewire carbon flux for chemical production in Escherichia coli. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 14492–14504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Deng, A.; Liu, S.; Cui, D.; Qiu, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J.; Shang, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A novel tool for microbial genome editing using the restriction-modification system. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, L.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Feng, Q.; Liu, L.; Zheng, G.; Yan, Y.; Sun, X.; Yuan, Q. Targeting metabolic driving and intermediate influx in lysine catabolism for high-level glutarate production. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.T.; Baritugo, K.A.; Oh, Y.H.; Hyun, S.M.; Khang, T.U.; Kang, K.H.; Jung, S.H.; Song, B.K.; Park, K.; Kim, I.K.; et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the high-level production of cadaverine that can be used for the synthesis of biopolyamide 510. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5296–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, J.-H.; Bhatia, S.K.; Seo, H.-M.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.K.; Yang, Y.-H.; Park, K. Application of diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate (DEEMM) derivatization for monitoring of lysine decarboxylase activity. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 115, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganism | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g Glucose) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli KARL4 | 55.58 | 0.380 | 1.74 | [4] |

| E. coli NT1005 | 58.7 | 0.396 | 1.48 | [19] |

| E. coli L18 | 64.03 | 0.230 | 1.33 | [44] |

| E. coli RSo1102 | 84.1 | 0.370 | 1.62 | [7] |

| C. glutamicum CSS | 103.8 | 0.303 | 1.47 | [51] |

| C. glutamicum GH30HaLDC | 125 | 0.341 | 1.79 | [20] |

| C. glutamicum YY | 105.5 | 0.36 | 2.93 | This study |

| Strains | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| E. coli JM109 | General cloning host |

| C. glutamicum Lys | L-lysine producing strain, CCTCC 2023742 |

| YY1 | C. glutamicum Lys, Ncgl1469::Ptrc-EcLdcC |

| YY1-aspB | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-aspB |

| YY1-lysC | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-lysC |

| YY1-ddh | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-ddh |

| YY1-lysA | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-lysA |

| YY1.1 | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-aspB, PgapA-lysC, PgapA-ddh, PgapA-lysA |

| YY1.2 | YY1, cgl0066::PgapA-aspB, PgapA-lysC, PgapA-lysA |

| YY2.1 | YY1.2, ΔcgmR, Ptac-cgmA |

| YY2.2 | YY2.1, S1 |

| YY2.3 | YY2.1, S1-Ptuf |

| YY2.4 | YY2.1, S1-PH36 |

| YY2.5 | YY2.1, S1-Ptac |

| YY2.6 | YY2.1, S1-Psod |

| YY2.7 | YY2.1, S1-PH30 |

| YY2.8 | YY2.1, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| YY2.9 | YY2.1, Psod-R180-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| YY2.10 | YY2.1, Psod-R1800-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| YY2.8-ddh | YY2.1, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-ddh |

| YY2.11 | YY2.1, lysE::Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-ddh |

| YY3.1 | YY2.11, cgl0818::PgapA-ptsG |

| YY3.2 | YY2.11, cgl0818::PgapA-IolT1 |

| YY3.3 | YY2.11, cgl0818::PgapA-IolT2 |

| YY3.4 | YY2.11, pCES208-PcgmA-IolT1 |

| YY3.5 | YY2.11, S1-IolT1 |

| YY3.6 | YY2.11, S1-Psod-IolT1 |

| YY3.7 | YY2.11, S1-Psod-R760-IolT1 |

| Plasmids | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| pK18mobsacB | Vector for selection of double crossover in C. glutamicum, Kanr |

| pK18-Ptrc-EcLdcC | pK18mobsacB with Ncgl1469 deletion replaced by Ptrc-EcLdcC constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-aspB | pK18mobsacB with cgl0066 deletion replaced by PgapA-aspB constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-lysC | pK18mobsacB with cgl0066 deletion replaced by PgapA-lysC constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-ddh | pK18mobsacB with cgl0066 deletion replaced by PgapA-ddh constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-lysA | pK18mobsacB with cgl0066 deletion replaced by PgapA-lysA constructs |

| pK18-ΔcgmR | pK18mobsacB with cgmR deletion constructs |

| pK18-Ptac-cgmA | pK18mobsacB with PcgmA deletion replaced by Ptac constructs |

| pCES208 | E. coli−C. glutamicum shuttle vector; Kmr |

| S1 | pCES208, Ptrc-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Ptuf | pCES208, Ptuf-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-PH36 | pCES208, PH36-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Ptac | pCES208, Ptac-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Psod | pCES208, Psod-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-PH30 | pCES208, PH30-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Psod-R760 | pCES208, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Psod-R180 | pCES208, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| S1-Psod-R1800 | pCES208, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-sfgfp |

| pK18-ΔlysE | pK18mobsacB with lysE deletion constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-ptsG | pK18mobsacB with cgl0818 deletion replaced by PgapA-ptsG constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-IolT1 | pK18mobsacB with cgl0818 deletion replaced by PgapA-IolT1 constructs |

| pK18-PgapA-IolT2 | pK18mobsacB with cgl0818 deletion replaced by PgapA-IolT2 constructs |

| S1-IolT1 | pCES208, Ptrc-cgmR, PcgmA-IolT1 |

| S1-Psod-IolT1 | pCES208, Psod-cgmR, PcgmA-IolT1 |

| S1-Psod-R760-IolT1 | pCES208, Psod-R760-cgmR, PcgmA-IolT1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Song, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. Enhancing 1,5-Pentanediamine Productivity in Corynebacterium glutamicum with Improved Lysine and Glucose Metabolism. Catalysts 2026, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010030

Gao C, Song L, Liu J, Liu L. Enhancing 1,5-Pentanediamine Productivity in Corynebacterium glutamicum with Improved Lysine and Glucose Metabolism. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Cong, Longfei Song, Jia Liu, and Liming Liu. 2026. "Enhancing 1,5-Pentanediamine Productivity in Corynebacterium glutamicum with Improved Lysine and Glucose Metabolism" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010030

APA StyleGao, C., Song, L., Liu, J., & Liu, L. (2026). Enhancing 1,5-Pentanediamine Productivity in Corynebacterium glutamicum with Improved Lysine and Glucose Metabolism. Catalysts, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010030