Microwave Synthesis of Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni)-Supported Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

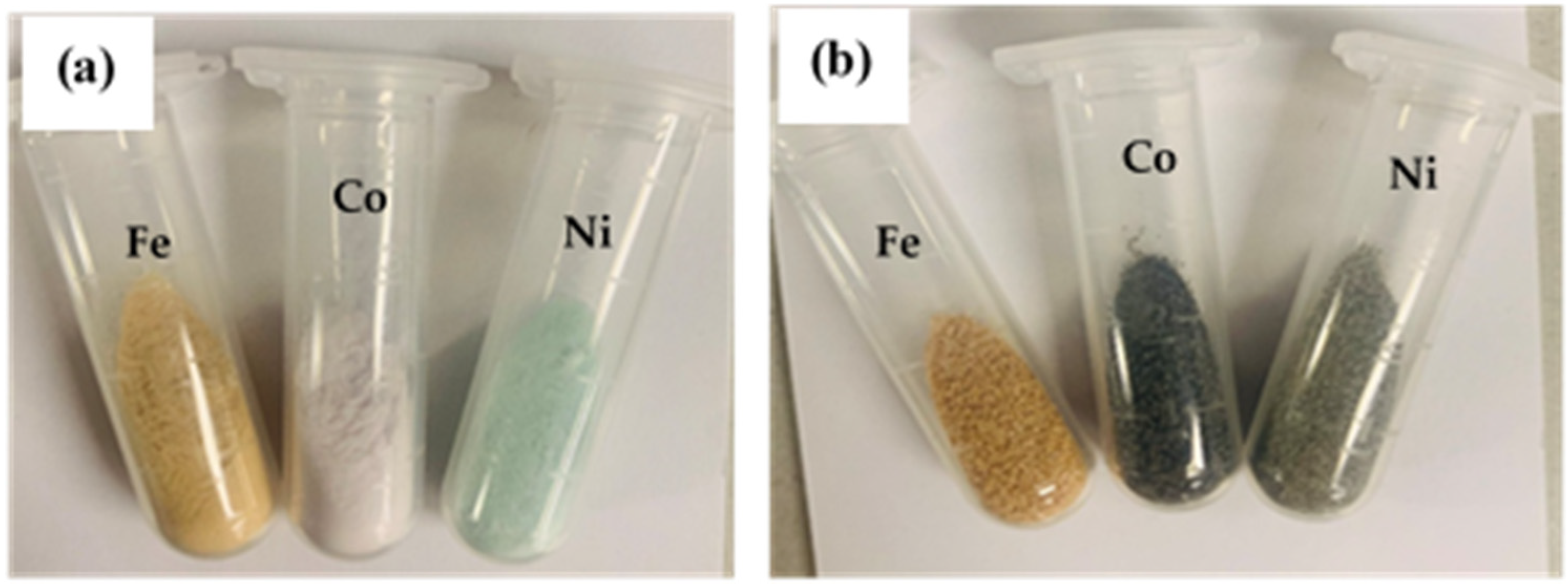

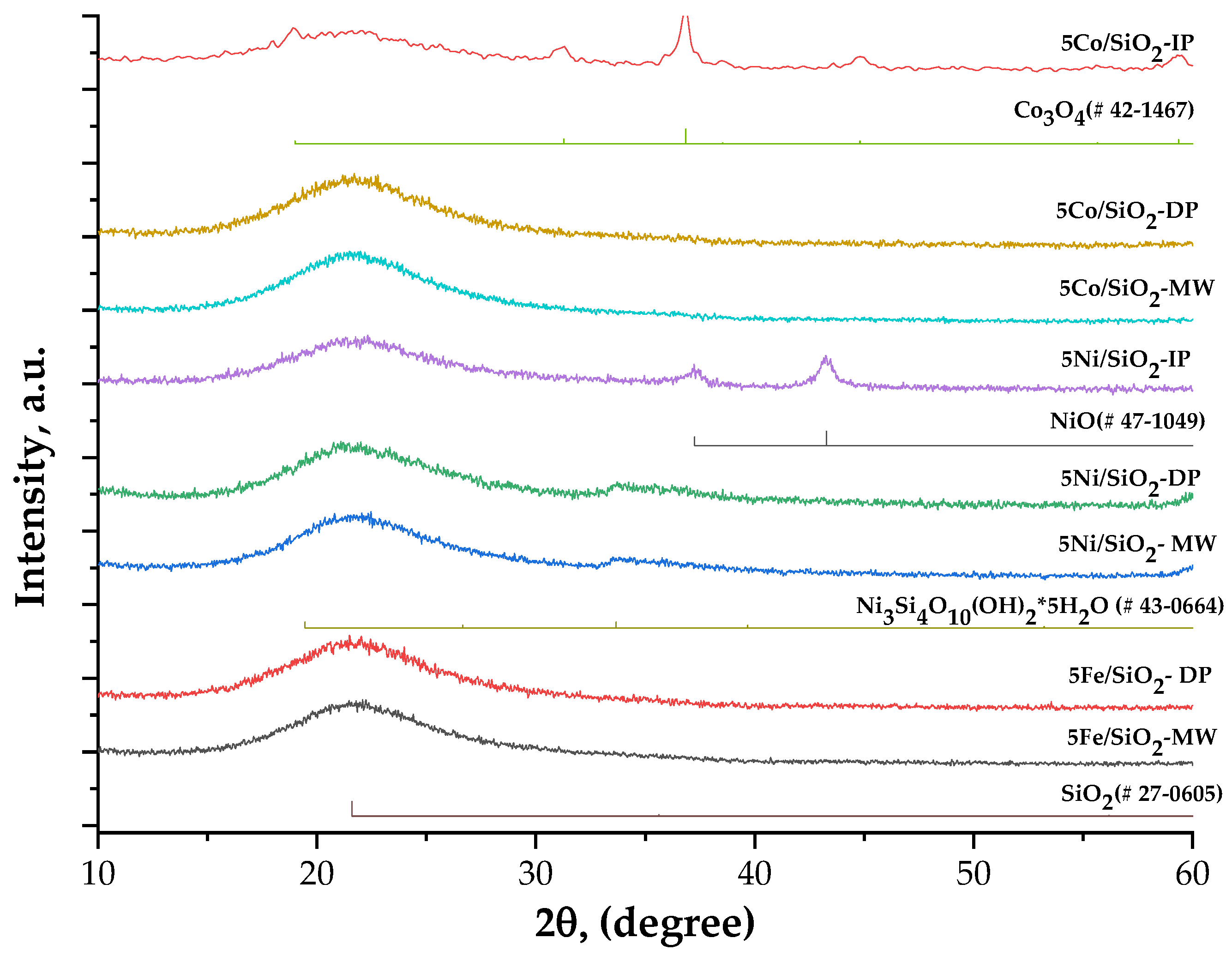

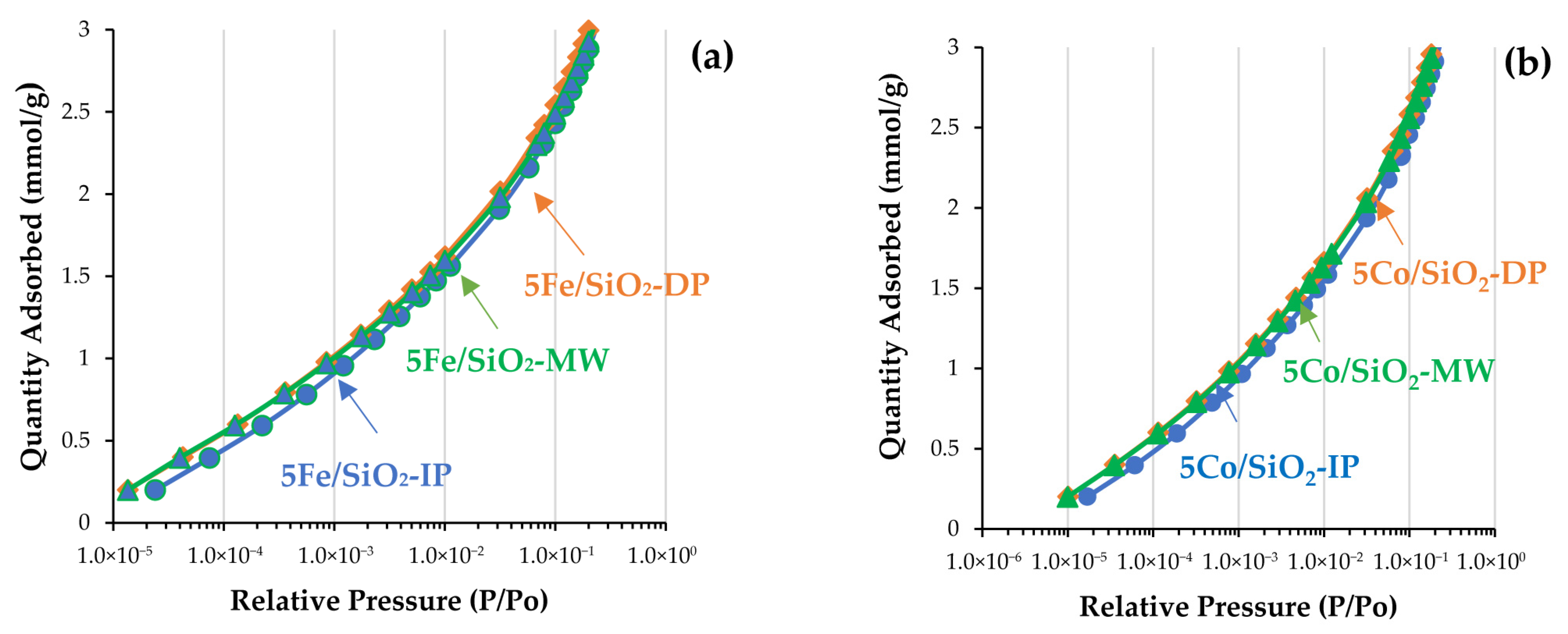

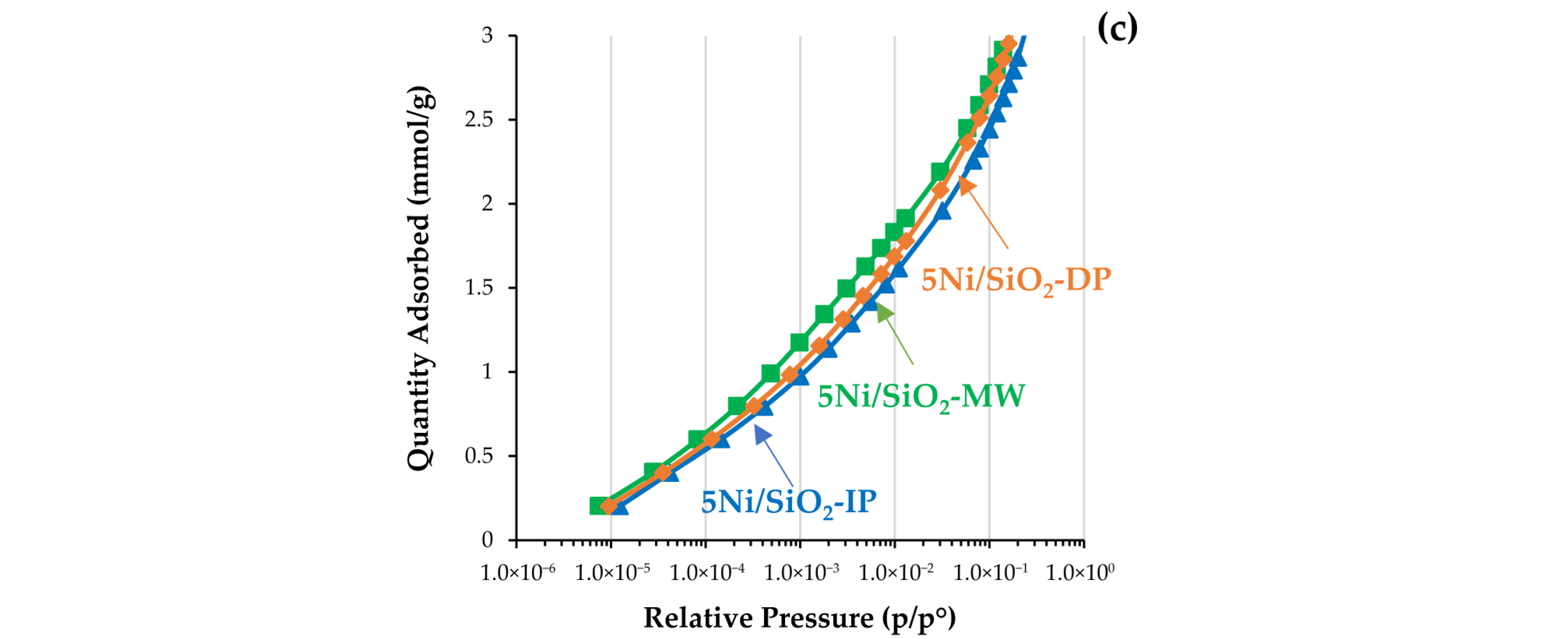

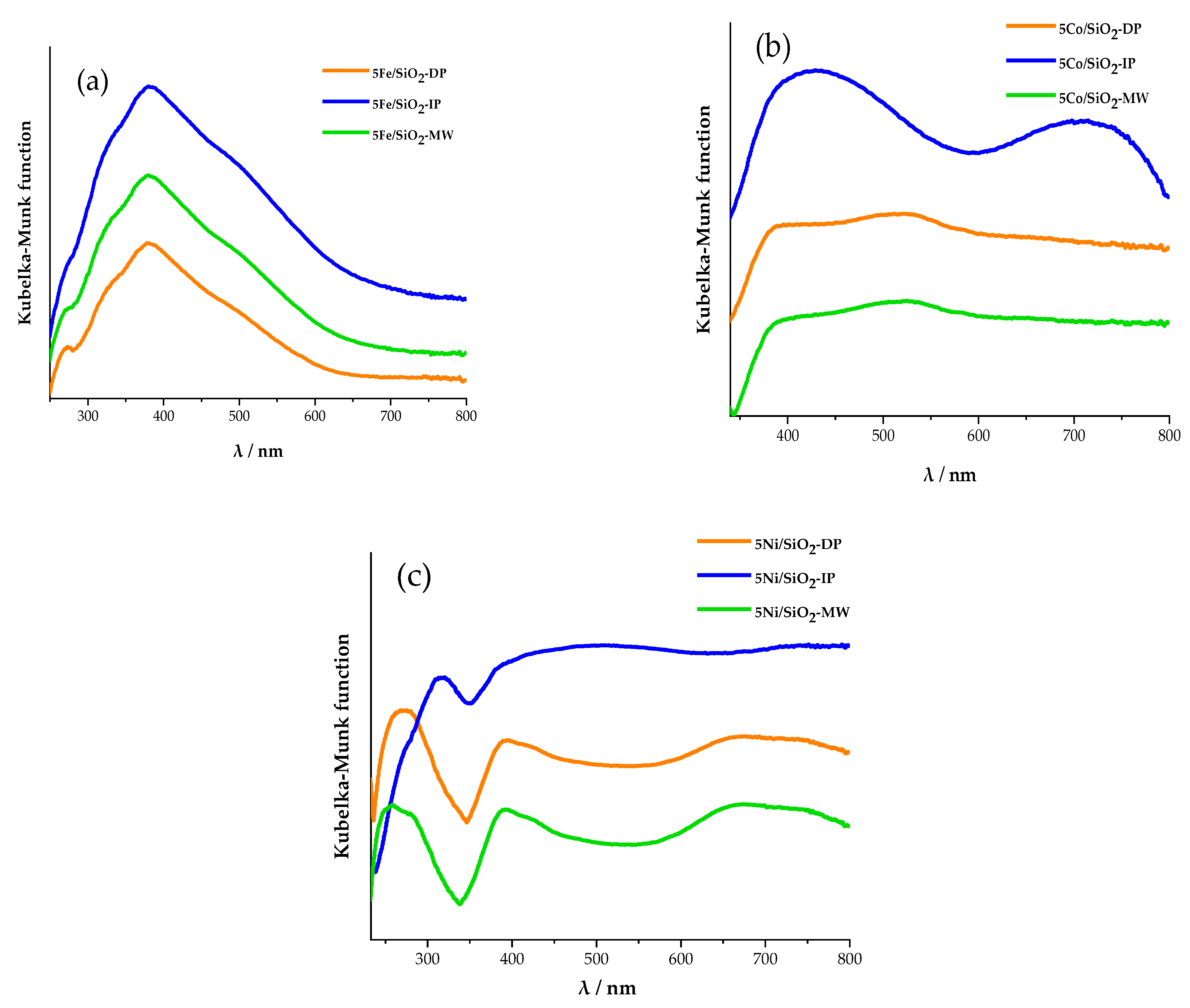

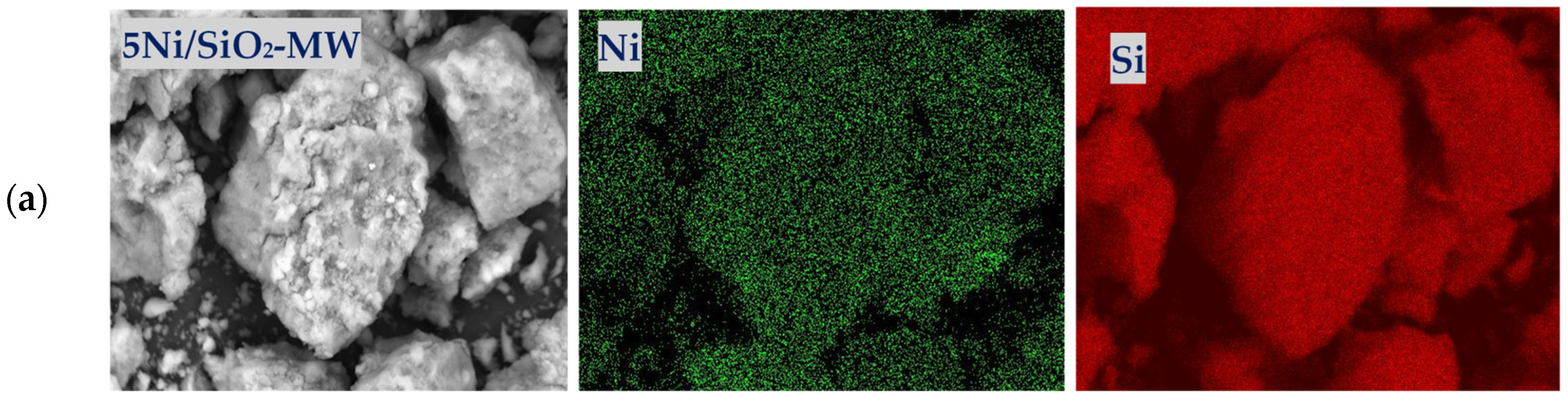

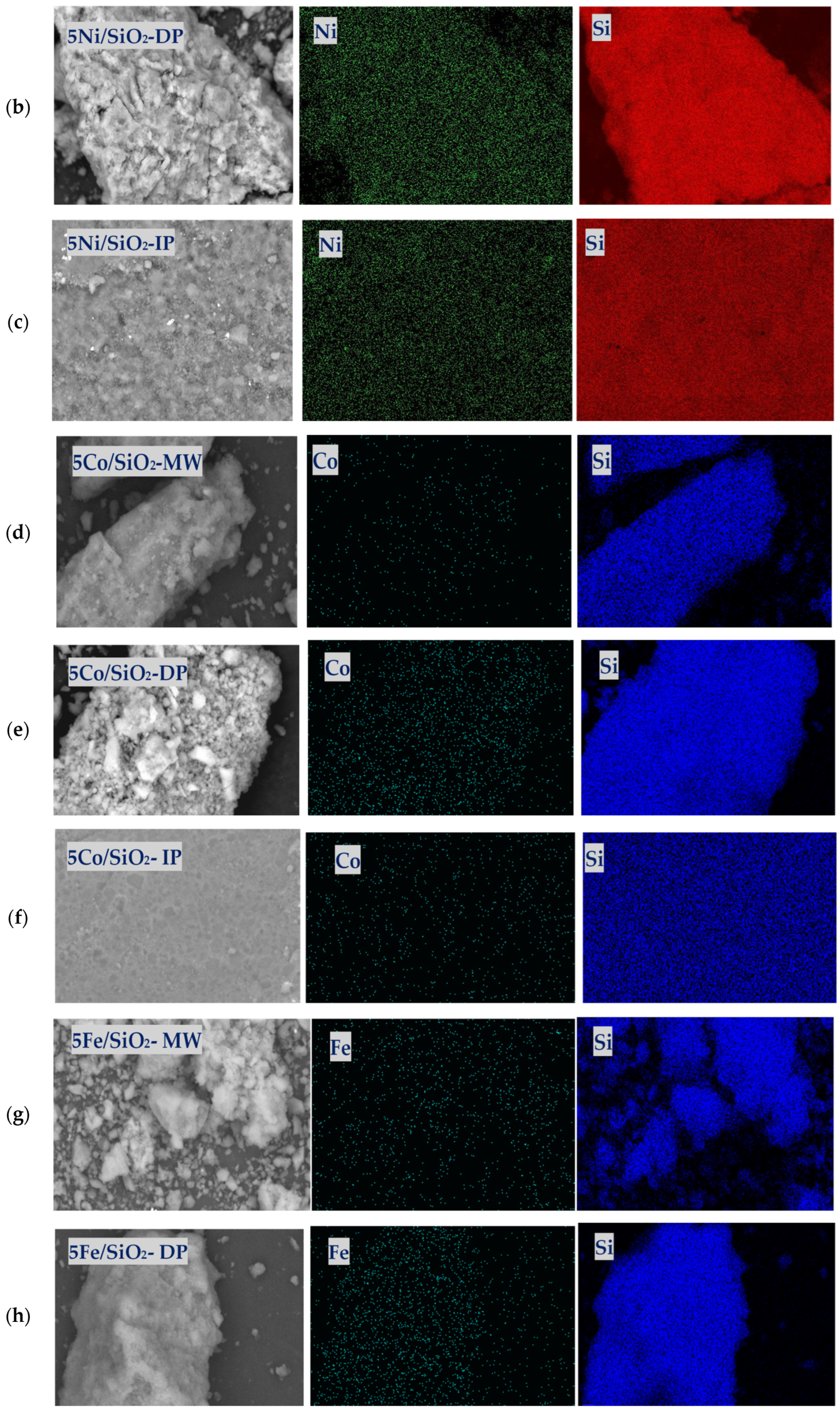

2.1. Physicochemical Properties of the Catalysts

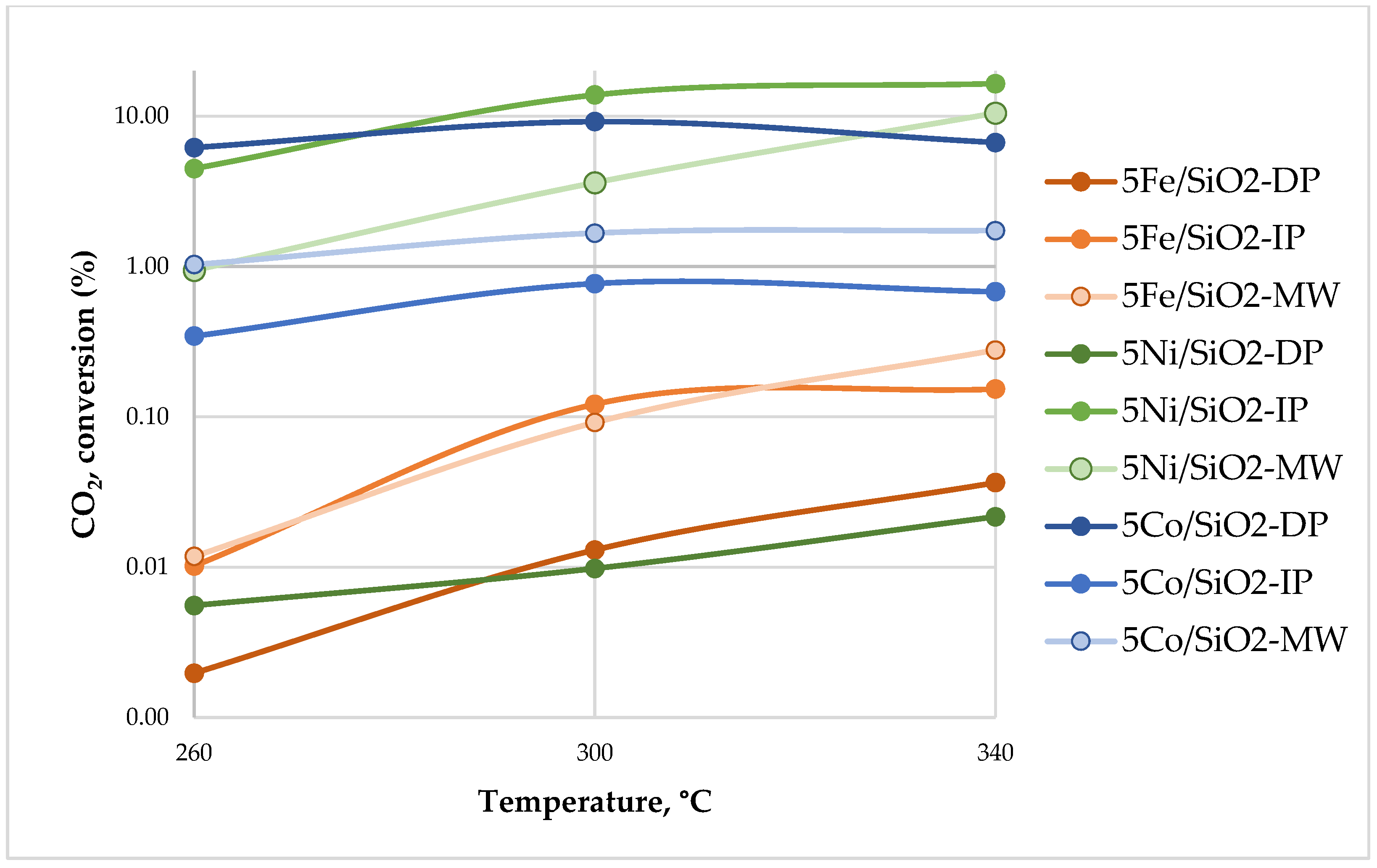

2.2. Catalytic Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

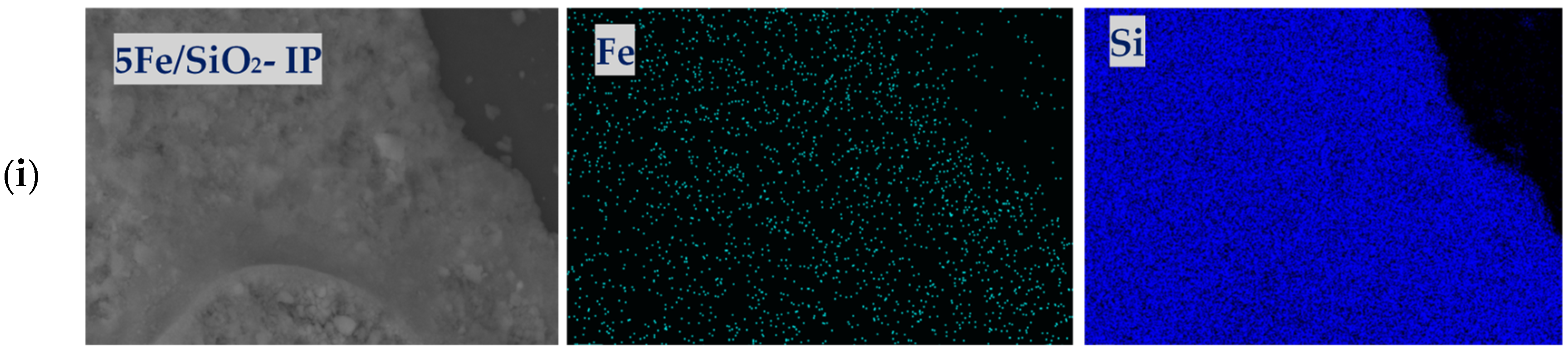

- (i)

- DPU method: The reactor for sample synthesis was a 250 mL round-bottomed flask placed in a water bath with a thermocouple between the walls of the bath and the reactor. A magnetic stirrer was placed into the reactor for the uniform stirring of the suspension, and simultaneously an aqueous solution of metal nitrate precursor at the required concentration (1 M) and the required volume of distilled water were introduced. Then we introduced a calcined SiO2 carrier and stirred the suspension for 15 min. After that, a weight of urea was added to the obtained suspension, and the suspension was heated to 92 °C, then thermostated under constant stirring for 9 h. Then the suspension was cooled, the precipitate was separated from the mother liquor by centrifugation, and the sample was dried under a vacuum on a rotary evaporator at 40 °C for 2 h. The dry sample was additionally calcined in an air atmosphere at 300 °C for 3 h. The catalysts were denoted as 5Fe/SiO2-DP, 5Co/SiO2-DP, and 5Ni/SiO2-DP, respectively [29,31].

- (ii)

- MW method: For microwave synthesis, the Multiwave Pro (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria) microwave oven equipped with four autoclave-type beakers was used in the preparation of catalysts. A magnetic stirrer was placed in each beaker, then the SiO2 carrier was added, and an equal amount of the prepared solution was introduced, as in the DPU method (i). Next, the beakers were sealed and placed in a microwave reactor. The process of hydrothermal synthesis was carried out under the following conditions: temperature—92 °C (measured in each beaker by an IR sensor), pressure—9 bar, time of synthesis—5 h, and microwave radiation power—100 W. Upon completion of the process, the resulting suspension was washed three times with distilled water, centrifuged and dried under a vacuum for 3 h. Dry samples were additionally calcined in an air atmosphere at a temperature of 300 °C for 3 h. The catalysts were denoted as 5Fe/SiO2-MW, 5Co/SiO2-MW, and 5Ni/SiO2-MW, respectively [31].

- (iii)

- IP method: For comparison, samples were synthesized by the carrier impregnation method. The pre-vacuumed SiO2 carrier (2 g) was impregnated for 2 h with aqueous solutions of nitrates of the corresponding salts (Fe(NO3)3, Co(NO3)2, and Ni(NO3)2), with periodic shaking for uniform distribution, then the samples were dried in an oven at 110 °C and calcined at 300 °C in air for 3 h. The calcined catalysts obtained by the IP method were designated 5Fe/SiO2-IP, 5Co/SiO2-IP, and 5Ni/SiO2-IP, respectively.

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Catalyst Activity Test

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Fan, S.; Wang, S.; Dong, M.; Qin, Z.F.; Bin Fan, W.; Wang, J.G. Research progresses in the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to certain hydrocarbon products. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2021, 49, 1609–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Dokania, A.; Ramirez, A.; Gascon, J. Advances in the Design of Heterogeneous Catalysts and Thermocatalytic Processes for CO2 Utilization. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 14147–14185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A.; Bansode, A.; Urakawa, A.; Bavykina, A.V.; Wezendonk, T.A.; Makkee, M.; Gascon, J.; Kapteijn, F. Challenges in the Greener Production of Formates/Formic Acid, Methanol, and DME by Heterogeneously Catalyzed CO2 Hydrogenation Processe. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 9804–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.J.; Cui, X.J.; Deng, T.S.; Qin, Z.F.; Bin Fan, W. Solvent effect on the activity of Ru-Co3O4 catalyst for liquid-phase hydrogenation of CO2 into methane. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2021, 49, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Feng, L.; Yu, Z.; Xu, D.; Liu, K.; Song, X.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Q.; Wang, G.; Ding, M. Effects of preparation methods on the performance of InZr/SAPO-34 composite catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to light olefins. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2024, 52, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Monai, M.; Kramer, G.J.; Weckhuysen, B.M. The renaissance of the Sabatier reaction and its applications on Earth and in space. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.W.; Zhou, Z.H.; He, L.N. Efficient, selective and sustainable catalysis of carbon dioxide. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3707–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.; Najari, S.; Fazlollahi, F.; Nikoo, M.K.; Sefidkon, F.; Klemeš, J.J.; Baxter, L.L. Mechanisms and kinetics of CO2 hydrogenation to value-added products: A detailed review on current status and future trends. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1292–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mei, S.; Yuan, K.; Wang, D.J.; Liu, H.C.; Yan, C.H.; Zhang, Y.W. Low-Temperature CO2 Methanation over CeO2-Supported Ru Single Atoms, Nanoclusters, and Nanoparticles Competitively Tuned by Strong Metal-Support Interactions and H-Spillover Effect. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6203–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelovic, A.; Ruiz, P. Mechanistic study of low temperature CO2 methanation over Rh/TiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2013, 301, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.H.; Kovarik, L.; Szanyi, J. Heterogeneous catalysis on atomically dispersed supported metals: CO2 reduction on multifunctional Pd catalysts. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parastaev, A.; Muravev, V.; Huertas Osta, E.; van Hoof, A.J.F.; Kimpel, T.F.; Kosinov, N.; Hensen, E.J.M. Boosting CO2 hydrogenation via size-dependent metal–support interactions in cobalt/ceria-based catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, V.I.; Koklin, A.E.; Kustov, A.L.; Pokusaeva, Y.A.; Bogdan, T.V.; Kustov, L.M. Carbon Dioxide Reduction with Hydrogen on Fe, Co Supported Alumina and Carbon Catalysts under Supercritical Conditions. Molecules 2021, 26, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, C.; Monai, M.; Sterk, E.B.; Palle, J.; Melcherts, A.E.M.; Zijlstra, B.; Groeneveld, E.; Berben, P.H.; Boereboom, J.M.; Hensen, E.J.M.; et al. Understanding carbon dioxide activation and carbon–carbon coupling over nickel. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smit, E.; Weckhuysen, B.M. The renaissance of iron-based Fischer–Tropsch synthesis: On the multifaceted catalyst deactivation behavior. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 2758–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kustov, A.L.; Aymaletdinov, T.R.; Shesterkina, A.A.; Kalmykov, K.B.; Pribytkov, P.V.; Mishin, I.V.; Dunaev, S.F.; Kustov, L.M. Methane dry reforming: Influence of the SiO2 and Al2O3 supports on the catalytic properties of Ni catalysts. Mendeleev Commun. 2024, 34, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, B.; Abd Ghani, N.A.; Vo, D.V.N. Recent advances in dry reforming of methane over Ni-based catalysts. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 162, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, L.; Chen, M.; Lv, C.; Wen, X.; Cui, Y.; Wu, C.E.; Yang, B.; Miao, Z.; Hu, X. Recent Progresses in the Design and Fabrication of Highly Efficient Ni-Based Catalysts with Advanced Catalytic Activity and Enhanced Anti-coke Performance Toward CO2 Reforming of Methane. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 581923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebrahtu, C.; Abate, S.; Perathoner, S.; Chen, S.; Centi, G. CO2 methanation over Ni catalysts based on ternary and quaternary mixed oxide: A comparison and analysis of the structure-activity relationships. Catal. Today 2018, 304, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evdokimenko, N.; Yermekova, Z.; Roslyakov, S.; Tkachenko, O.; Kapustin, G.; Bindiug, D.; Kustov, A.; Mukasyan, A.S. Sponge-like CoNi Catalysts Synthesized by Combustion of Reactive Solutions: Stability and Performance for CO2 Hydrogenation. Mater. 2022, 15, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacariza, M.C.; Graça, I.; Bebiano, S.S.; Lopes, J.M.; Henriques, C. Micro- and mesoporous supports for CO2 methanation catalysts: A comparison between SBA-15, MCM-41 and USY zeolite. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 175, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati-Niasari, M.; Shakouri-Arani, M.; Davar, F. Flexible ligand synthesis, characterization and catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane with host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)/guest (Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes of tetrahydro-salophen) nanocomposite materials. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2008, 116, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, F.; Salavati-Niasari, M.; Mahdi, M.A.; Meshkani, F. Multidisciplinary green approaches (ultrasonic, co-precipitation, hydrothermal, and microwave) for fabrication and characterization of Erbium-promoted Ni-Al2O3 catalyst for CO2 methanation. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkar, S.; Tezkratt, S.; Sellam, D.; Ikkour, K.; Parkhomenko, K.; Martinez-Martin, A.; Roger, A.C. Dry Reforming of Methane over Ni–Al2O3 and Ni–SiO2 Catalysts: Role of Preparation Methods. Catal. Lett. 2020, 150, 2180–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strekalova, A.A.; Shesterkina, A.A.; Kustov, A.L.; Kustov, L.M. Recent Studies on the Application of Microwave-Assisted Method for the Preparation of Heterogeneous Catalysts and Catalytic Hydrogenation Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustov, L.M.; Kostyukhin, E.M.; Korneeva, E.Y.; Kustov, A.L. Microwave synthesis of nanosized iron-containing oxide particles and their physicochemical properties. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Liu, Q.; He, Y.; Liang, P. Rapid construction of nickel phyllosilicate with ultrathin layers and high performance for CO2 methanation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 668, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, D.; Chen, C.; Jiang, L.; Takehira, K. Ni/Al2O3-ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 methanation: The role of γ-(Al, Zr)2O3 formation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 459, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shesterkina, A.A.; Vikanova, K.V.; Zhuravleva, V.S.; Kustov, A.L.; Davshan, N.A.; Mishin, I.V.; Strekalova, A.A.; Kustov, L.M. A novel catalyst based on nickel phyllosilicate for the selective hydrogenation of unsaturated compounds. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Kawi, S. Preparation, characterization and catalytic application of phyllosilicate: A review. Catal. Today 2020, 339, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shesterkina, A.; Vikanova, K.; Kostyukhin, E.; Strekalova, A.; Shuvalova, E.; Kapustin, G.; Salmi, T. Microwave Synthesis of Copper Phyllosilicates as Effective Catalysts for Hydrogenation of C≡C Bonds. Molecules 2022, 27, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Hu, L.; Hill, J.M. Comparison of reducibility and stability of alumina-supported Ni catalysts prepared by impregnation and co-precipitation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2006, 301, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Xia, X.; Cui, J.; Yan, W.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Efficient tuning of surface nickel species of the Ni-phyllosilicate catalyst for the hydrogenation of maleic anhydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 9779–9787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Shen, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Z. Preparation, characterization and activities of the nano-sized Ni/SBA-15 catalyst for producing COx-free hydrogen from ammonia. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2008, 337, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbino, G.; Tammaro, O.; Padua, A.; Basco, A.; Scognamiglio, S.; Sisti, M.; Arletti, R.; Marocco, A.; Pansini, M.; Landi, G.; et al. Unveiling the role of Ni nanometric particles in ultra-stable hierarchically porous Y zeolite to drive methane steam reforming and CO2 hydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 103, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, H.S.; Ramesh, A.; Sreedhar, I.; Da Cost, P.; Singh, S.A. Impact of oxygen vacancies on the catalytic activity of Ni/Co3O4 for CO2 methanation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 136, 1152–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

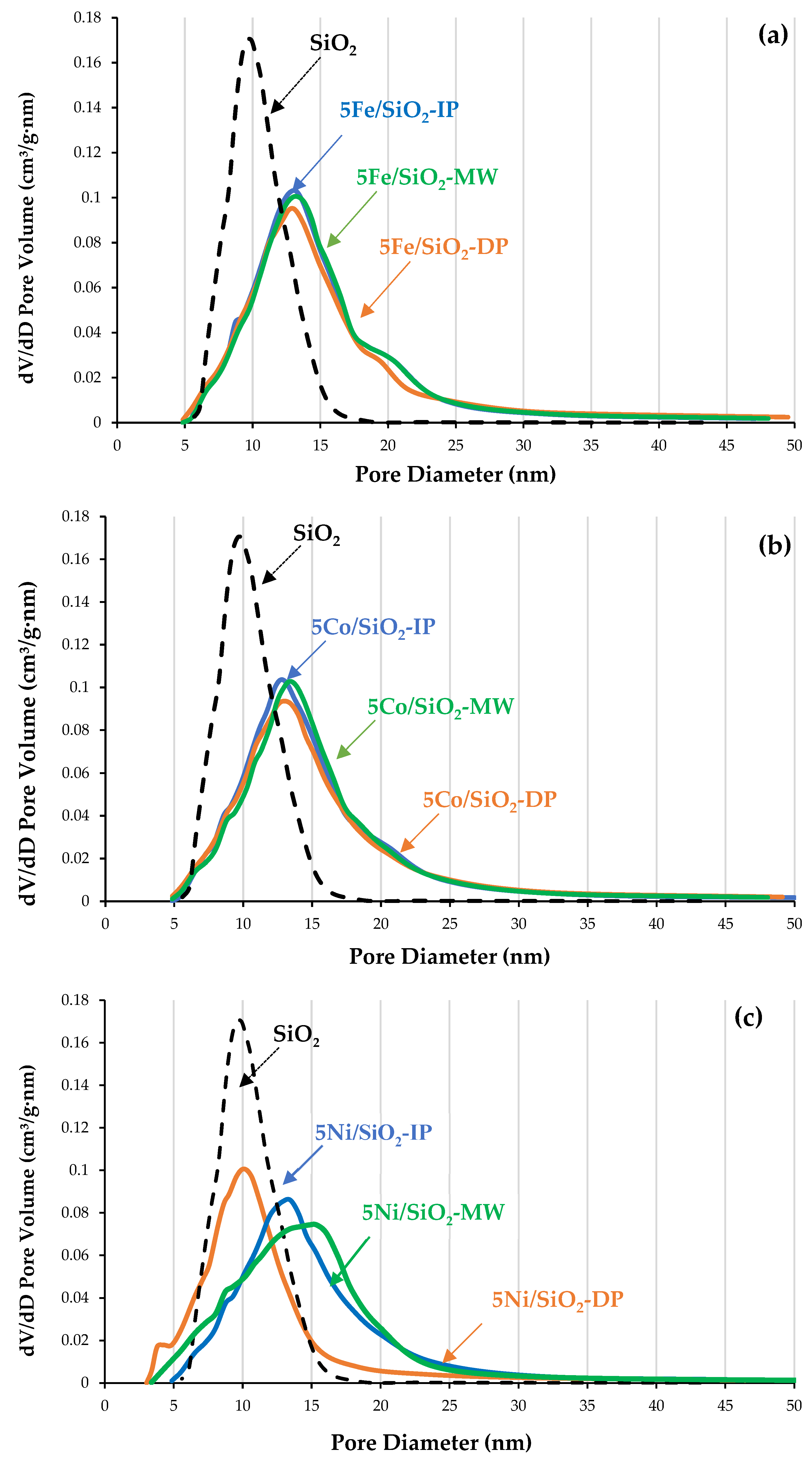

| Sample | XRD | SBET, m2/g | Vtot, cm3/g | Vmeso, cm3/g | Dpor, Micro/Meso, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5Ni/SiO2-IP | NiO | 218 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 1–2/5–35 |

| 5Ni/SiO2-DP | Ni3Si4O10(OH)2 | 281 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 1–2/3–30 |

| 5Ni/SiO2-MW | Ni3Si4O10(OH)2 | 256 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 1–2/3–30 |

| 5Fe/SiO2-IP | Fe2O3 | 234 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1–2/5–35 |

| 5Fe/SiO2-DP | - | 243 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 1–2/5–40 |

| 5Fe/SiO2-MW | - | 237 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1–2/5–40 |

| 5Co/SiO2-IP | Co3O4 | 237 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1–2/5–40 |

| 5Co/SiO2-DP | - | 246 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1–2/5–40 |

| 5Co/SiO2-MW | - | 244 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 1–2/5–40 |

| SiO2 | - | 244 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 1–2/6–18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Strekalova, A.A.; Shesterkina, A.A.; Beresnev, K.A.; Pribytkov, P.V.; Kapustin, G.I.; Mishin, I.V.; Kustov, L.M.; Kustov, A.L. Microwave Synthesis of Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni)-Supported Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts 2026, 16, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010111

Strekalova AA, Shesterkina AA, Beresnev KA, Pribytkov PV, Kapustin GI, Mishin IV, Kustov LM, Kustov AL. Microwave Synthesis of Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni)-Supported Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010111

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrekalova, Anna A., Anastasiya A. Shesterkina, Kirill A. Beresnev, Petr V. Pribytkov, Gennadiy I. Kapustin, Igor V. Mishin, Leonid M. Kustov, and Alexander L. Kustov. 2026. "Microwave Synthesis of Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni)-Supported Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010111

APA StyleStrekalova, A. A., Shesterkina, A. A., Beresnev, K. A., Pribytkov, P. V., Kapustin, G. I., Mishin, I. V., Kustov, L. M., & Kustov, A. L. (2026). Microwave Synthesis of Transition Metal (Fe, Co, Ni)-Supported Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation. Catalysts, 16(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010111