Interface-Engineered Zn@TiO2 and Ti@ZnO Nanocomposites for Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Levofloxacin

Abstract

1. Introduction

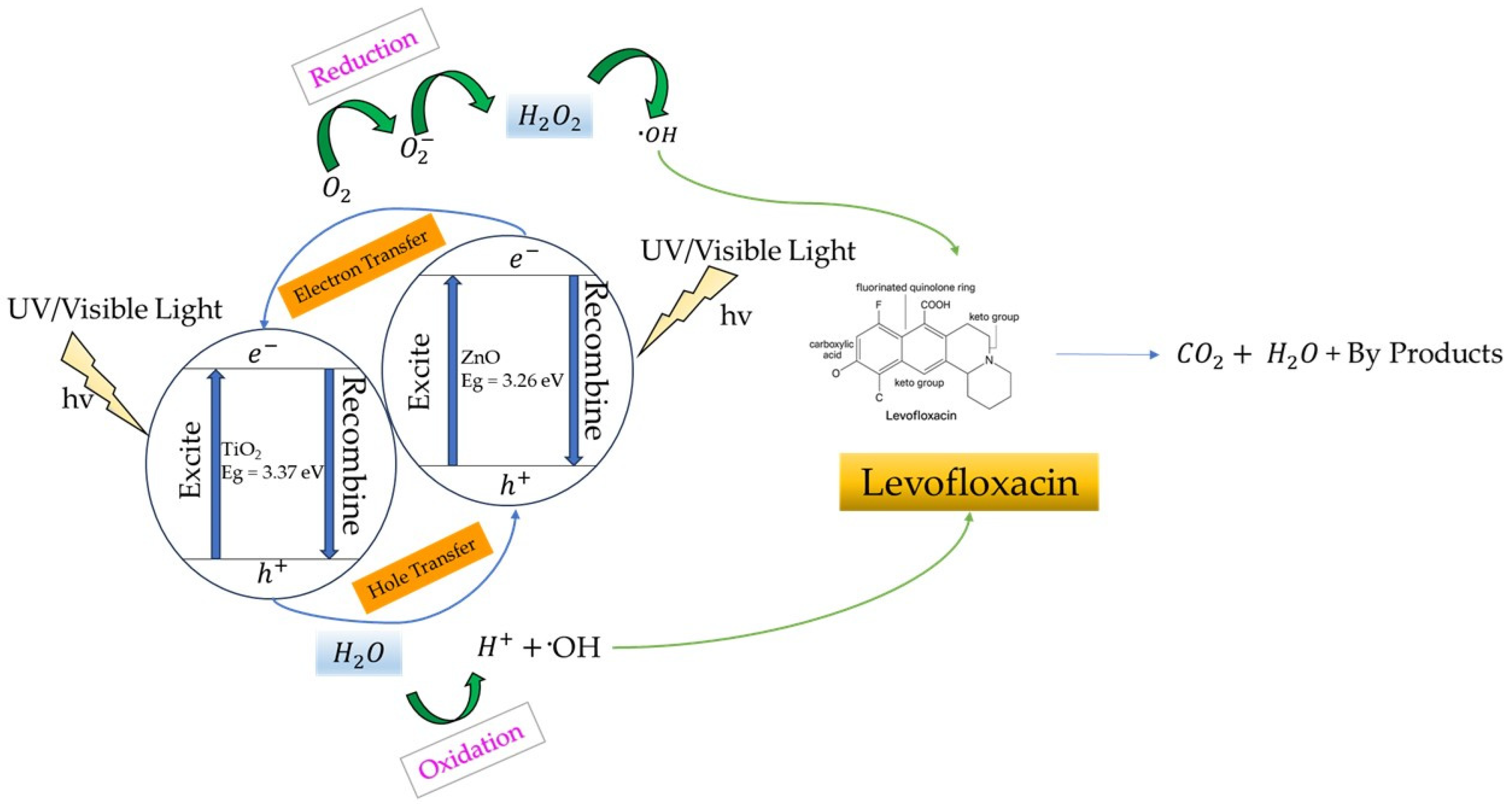

2. Results

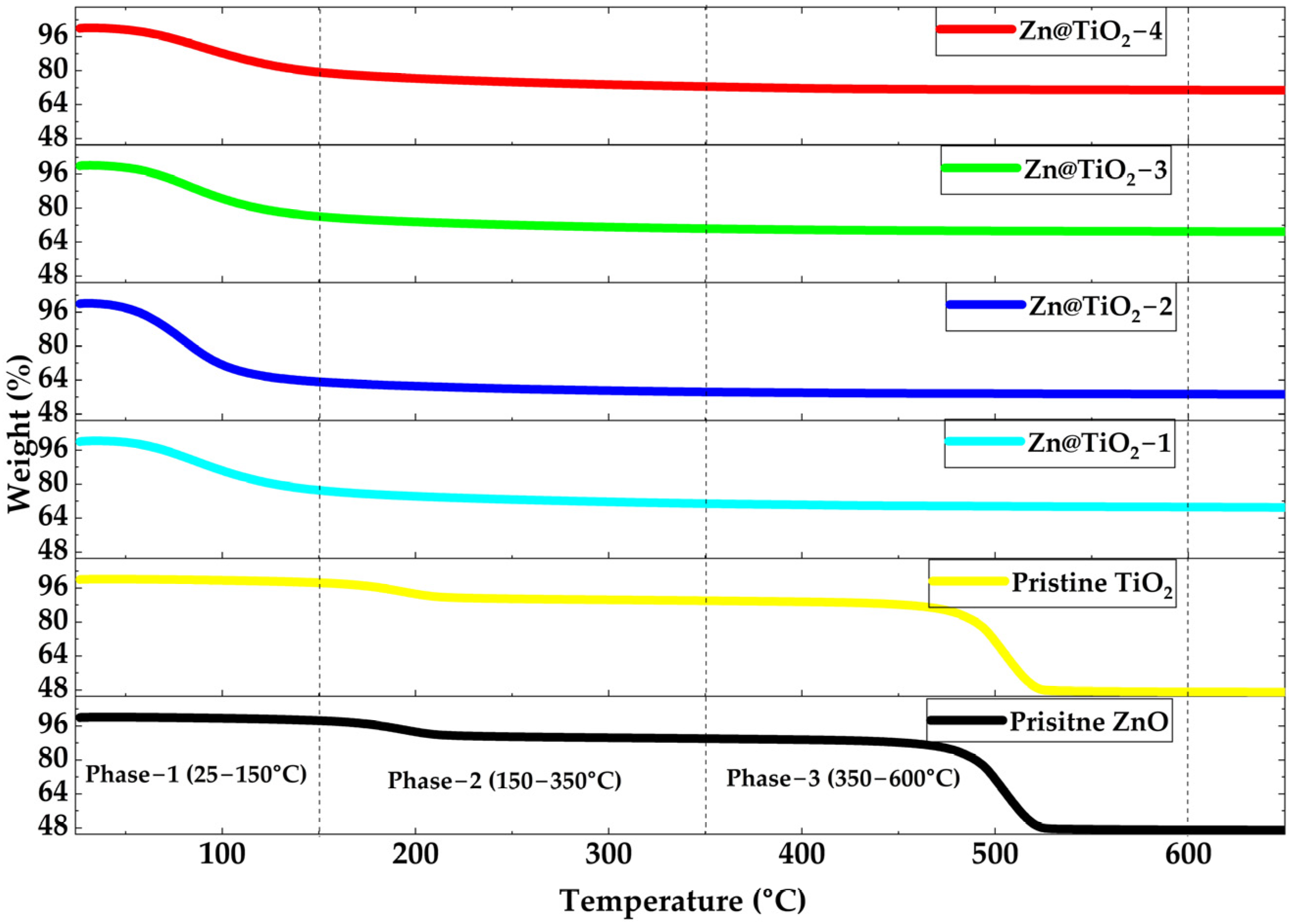

2.1. Thermal Analysis

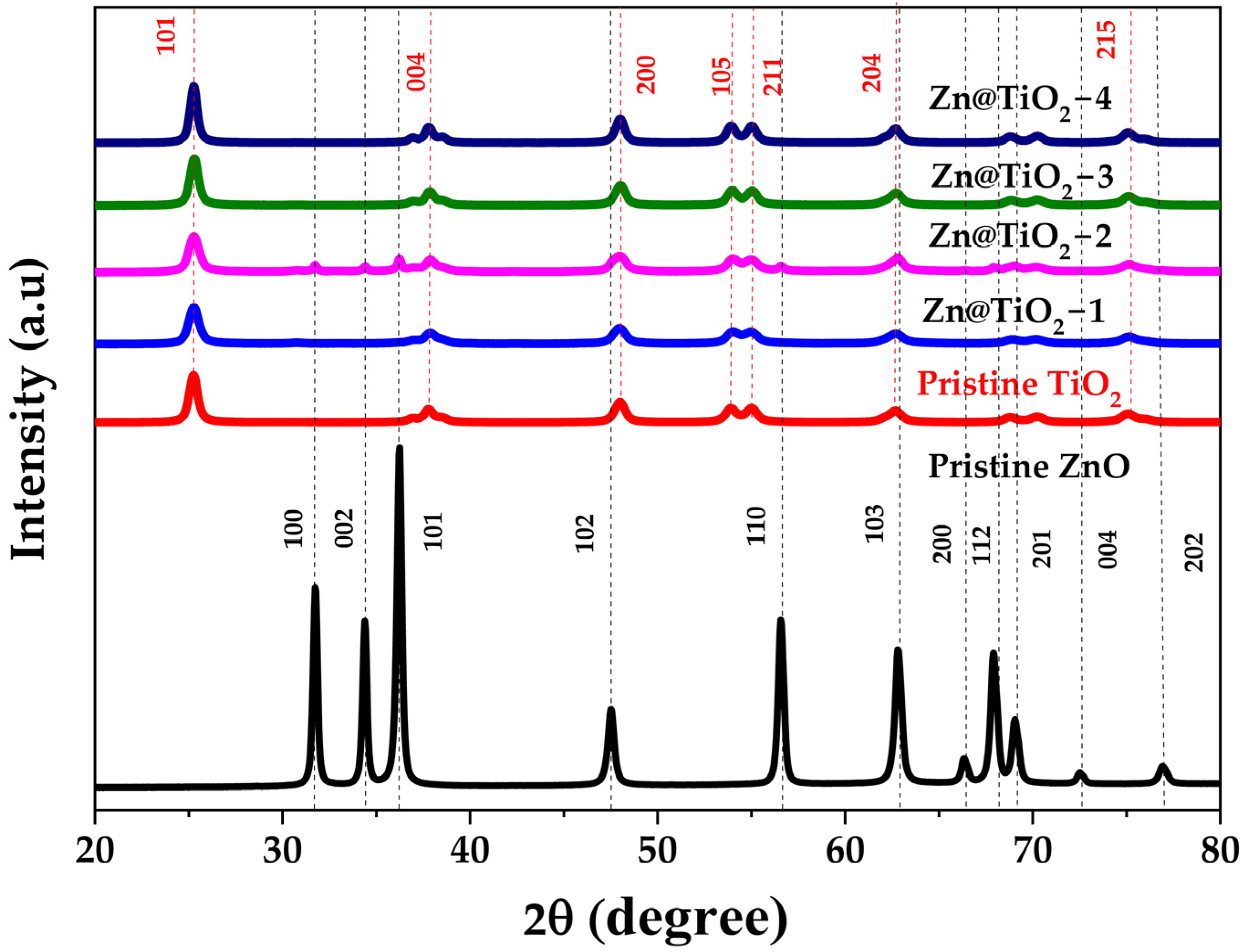

2.2. X-Ray Diffractometry (XRD)

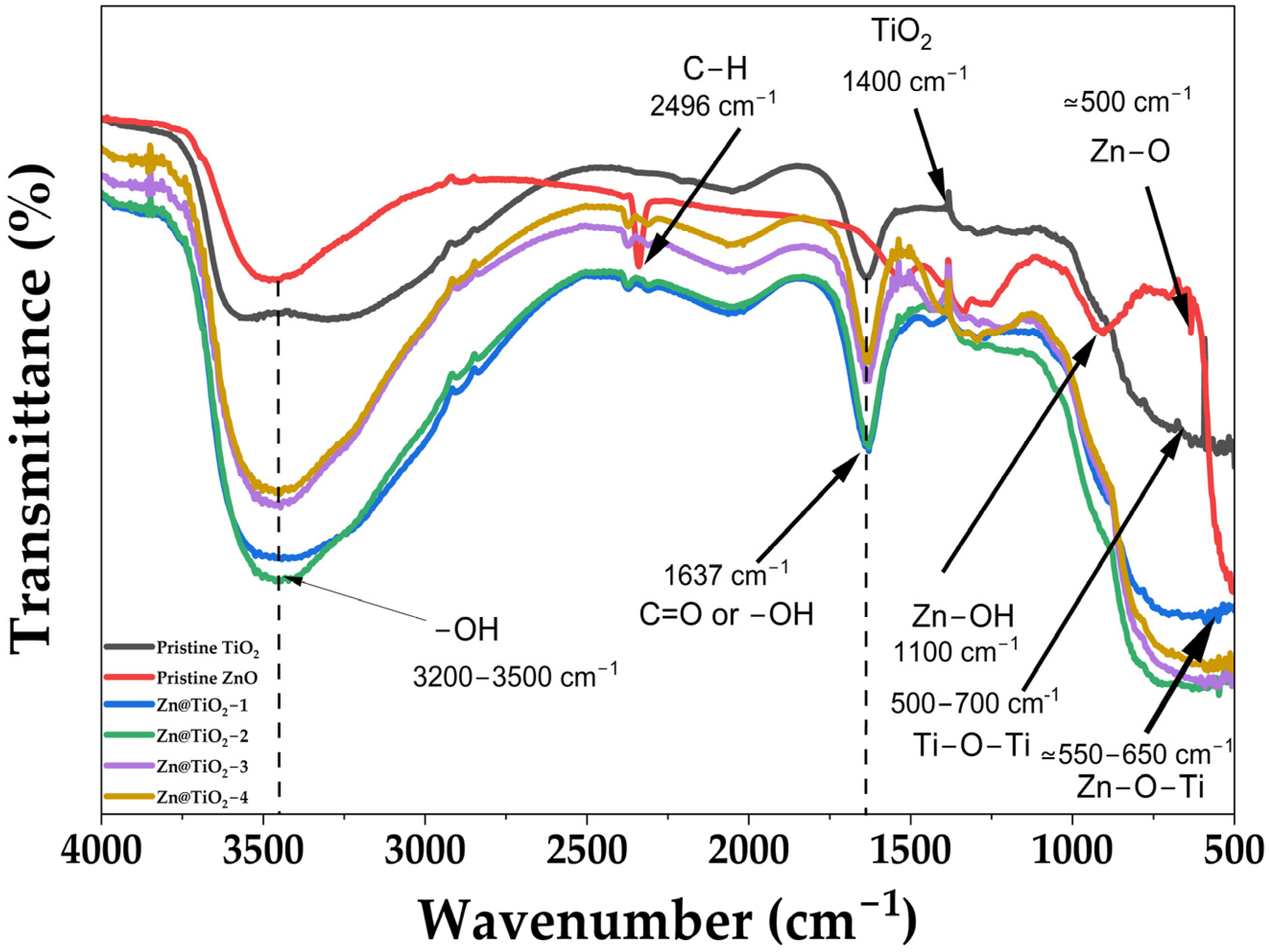

2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Sizer

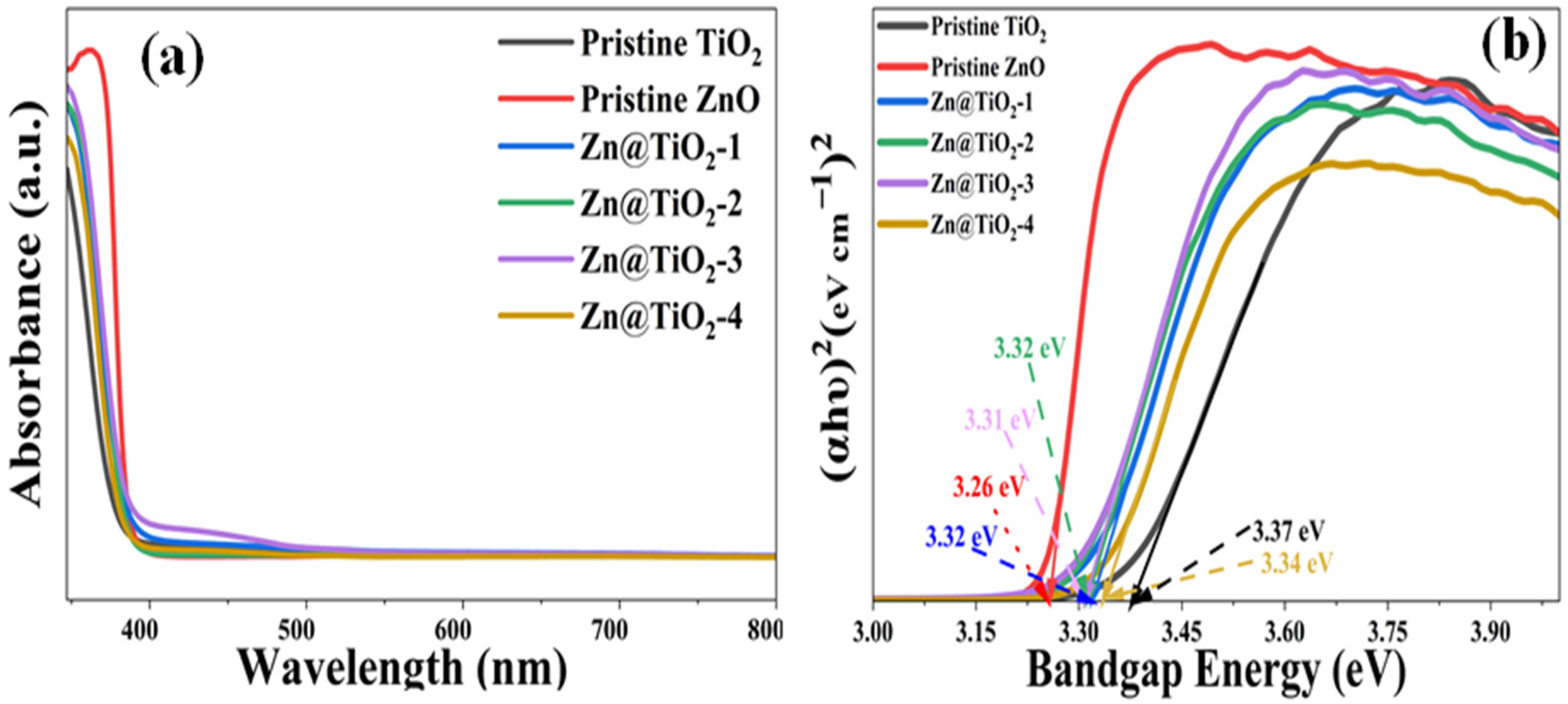

2.5. UV-Vis Measurement

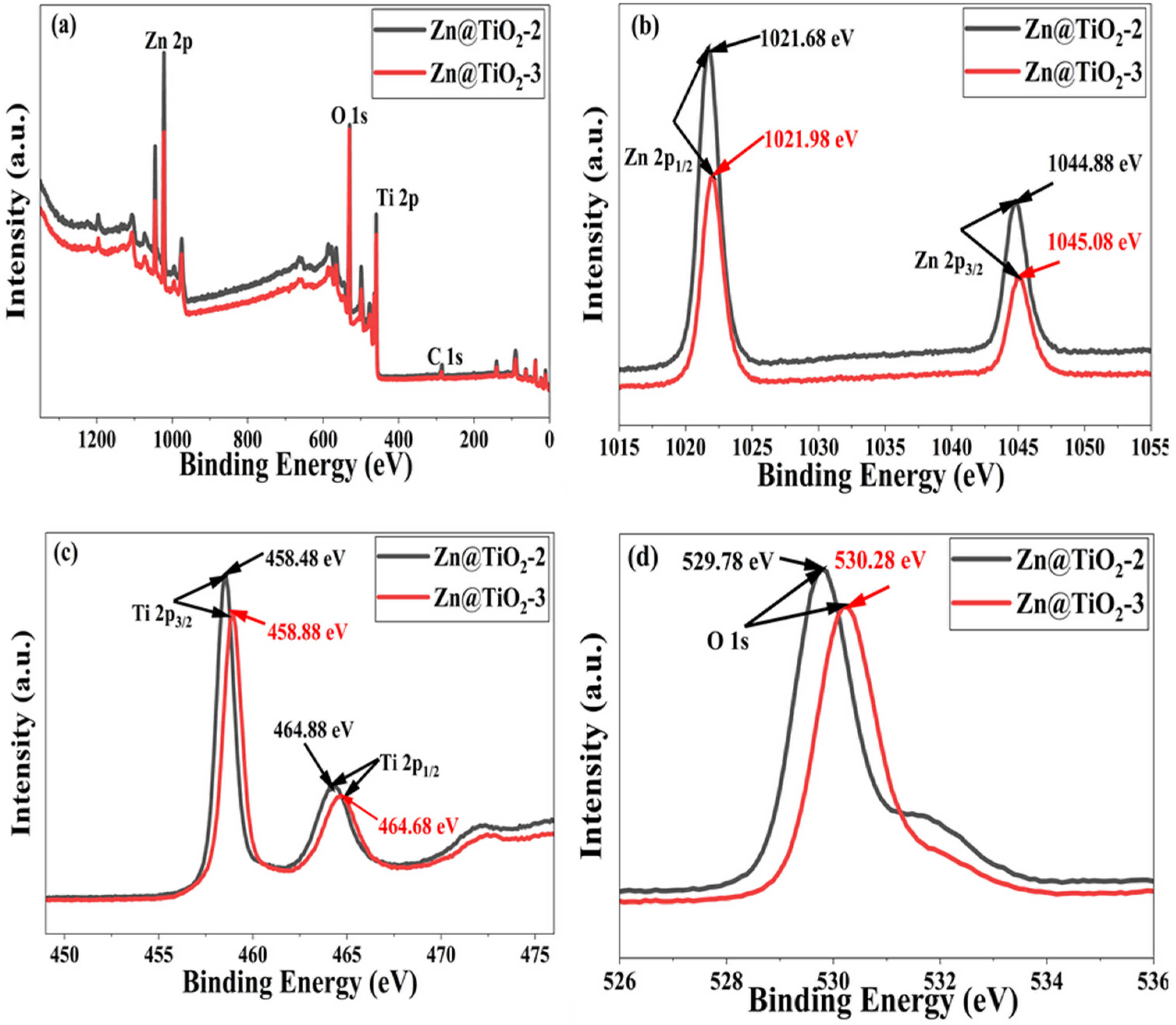

2.6. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

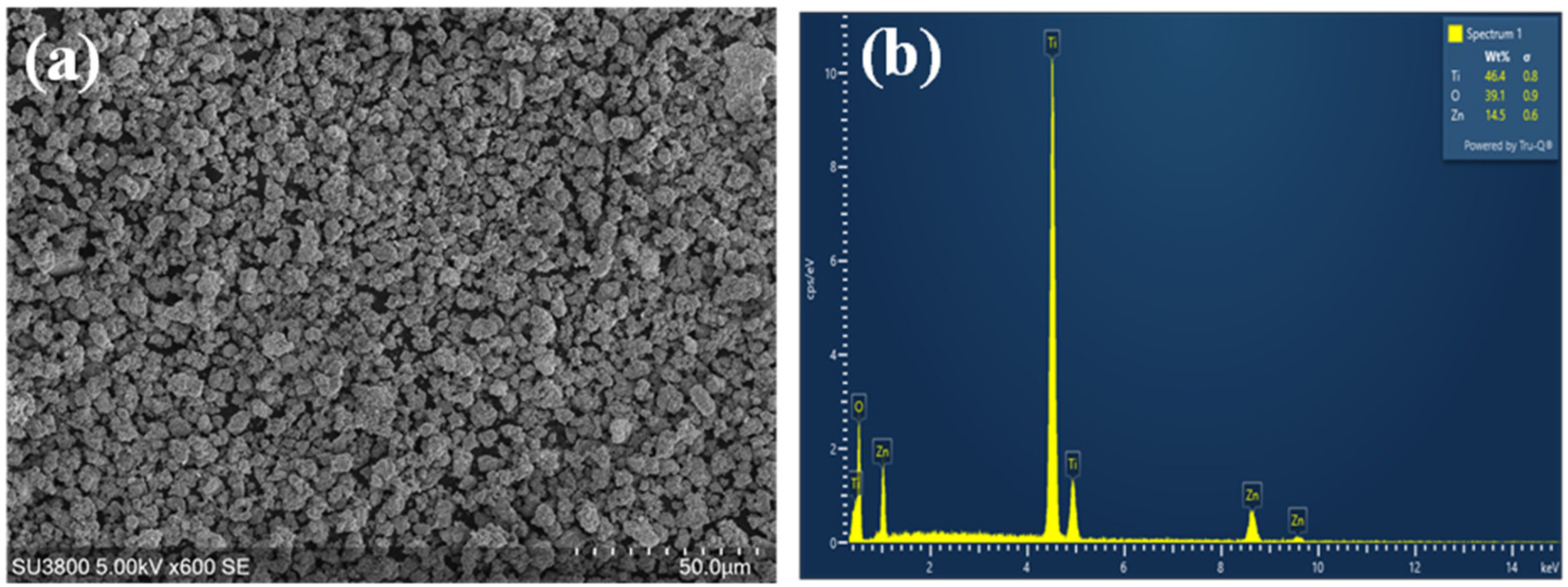

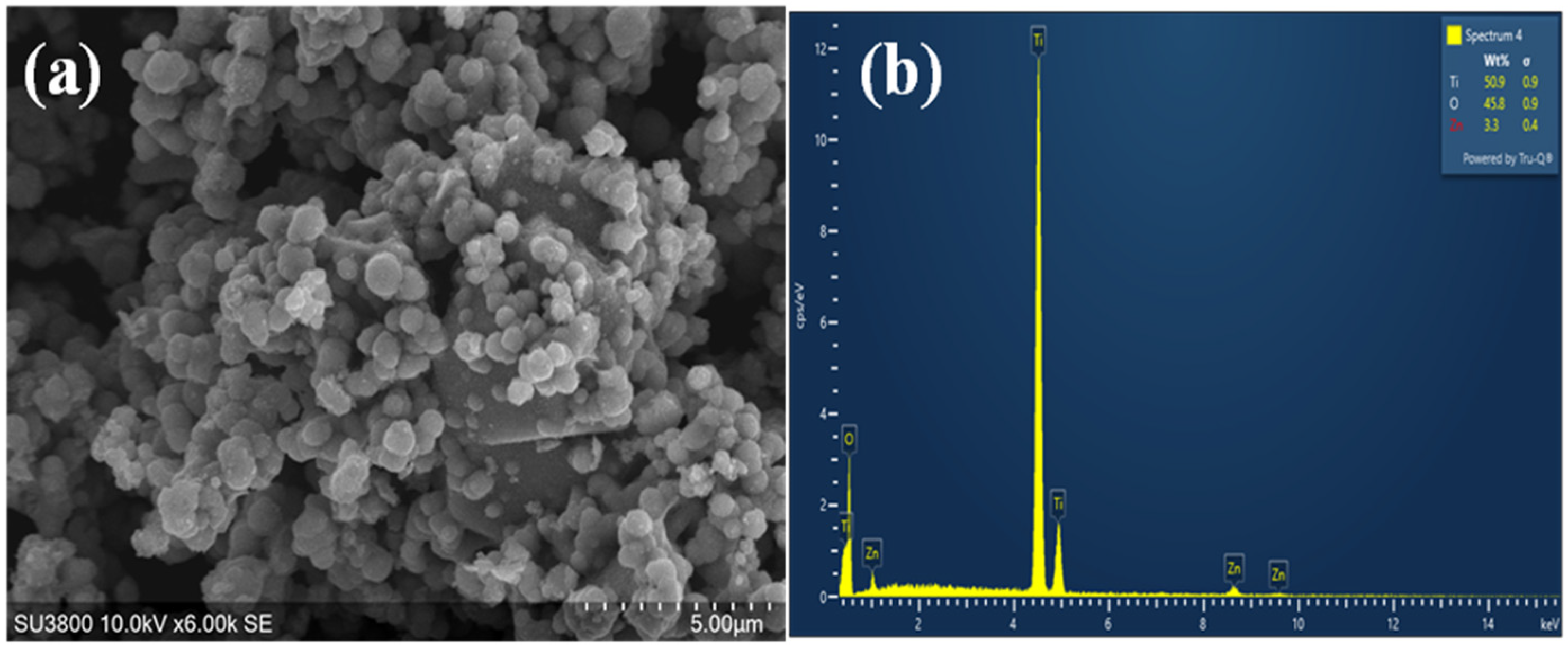

2.7. Structural and Morphological Characterization of Nanoparticles

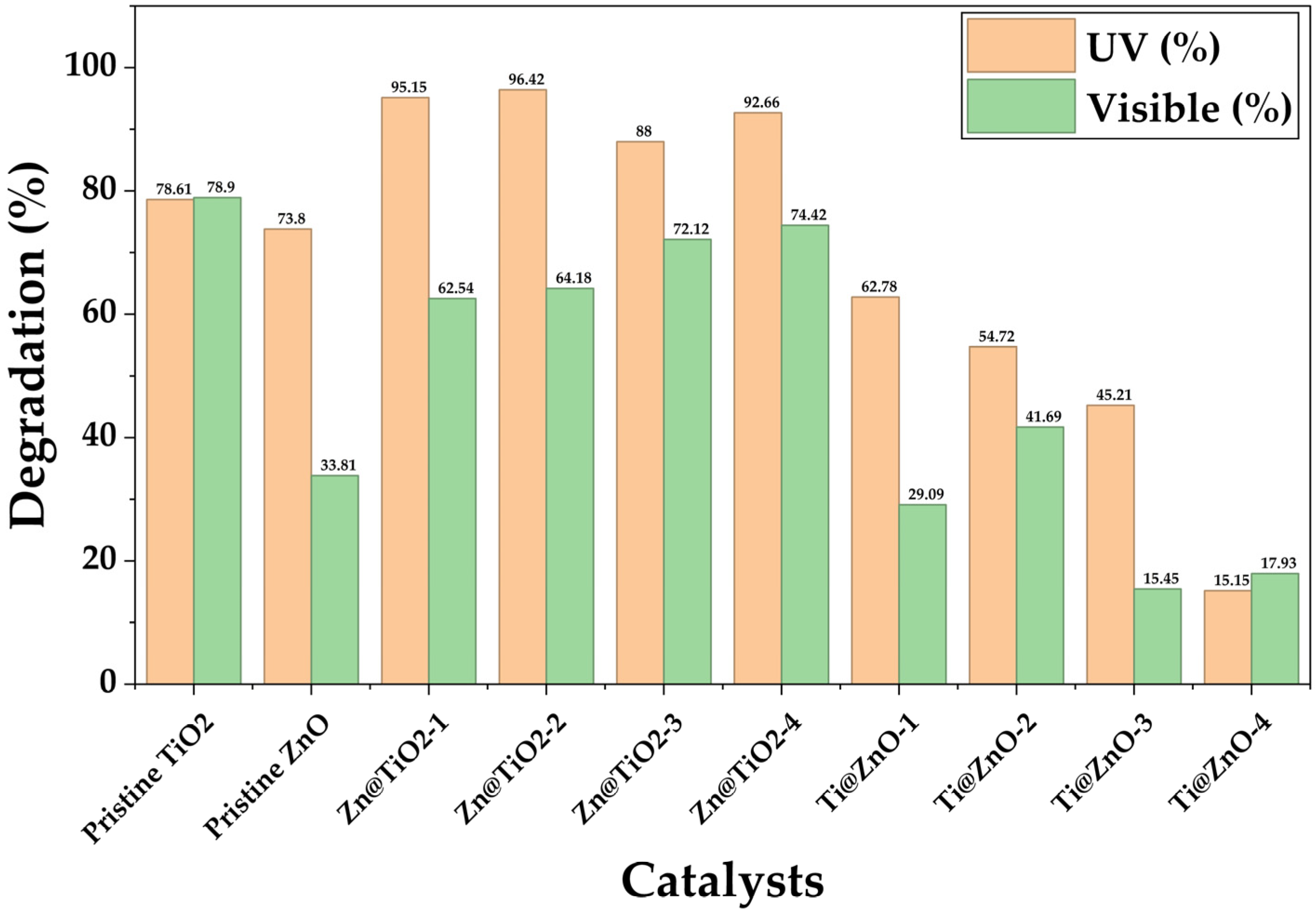

2.8. Photocatalytic Degradation

3. Discussion

3.1. Thermal Analysis

3.2. X-Ray Diffractometry (XRD)

3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

3.4. Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Sizer

3.5. UV-Vis Measurement

3.6. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

3.7. Structural and Morphological Characterization of Nanoparticles

3.8. Photocatalytic Degradation

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

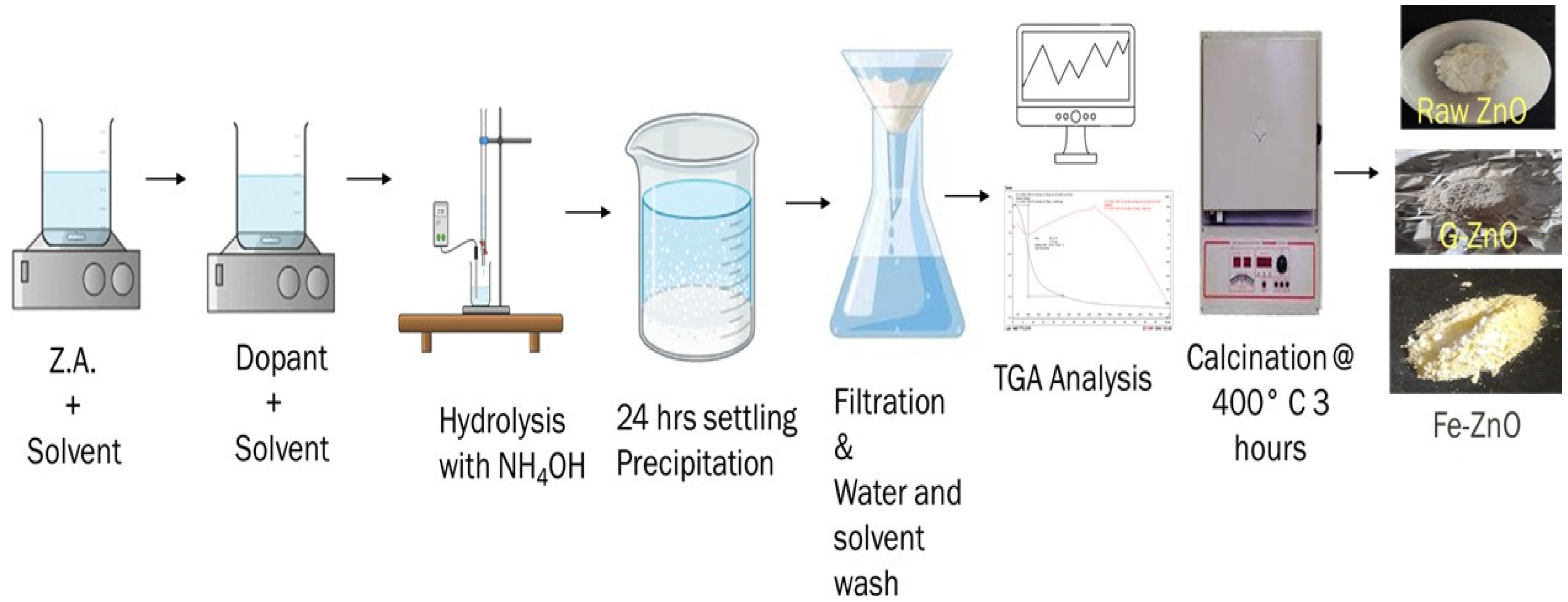

4.2. Method

4.2.1. Synthesis of TiO2 (Titanium Dioxide) Photocatalyst

4.2.2. Synthesis of ZnO (Zinc Oxide) Photocatalyst

4.2.3. Synthesis of TiO2-ZnO Nanocomposites

4.2.4. Levofloxacin Sample Preparation

4.2.5. Photocatalytic Activity

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dutta, D.; Arya, S.; Kumar, S. Industrial Wastewater Treatment: Current Trends, Bottlenecks, and Best Practices. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Liang, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, C. Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye. Water 2025, 17, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ruan, H.; Duan, P.; Shao, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y. Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics Using Nanomaterials: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Nanomaterials 2025, 16, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zeng, Y.; He, D.; Pan, X. Application of Iron-Based Materials in Heterogeneous Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 407, 127191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čizmić, M.; Ljubas, D.; Rožman, M.; Ašperger, D.; Ćurković, L.; Babić, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Azithromycin by Nanostructured TiO2 Film: Kinetics, Degradation Products, and Toxicity. Materials 2019, 12, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Li, W.; Wang, P.; Cheng, G.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, X. One-step Polymerization of Hydrophilic Ionic Liquid Imprinted Polymer in Water for Selective Separation and Detection of Levofloxacin from Environmental Matrices. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantzi, I.; Rico, A.; Mylona, K.; Pergantis, S.A.; Tsapakis, M. Fish Farming, Metals and Antibiotics in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea: Is There a Threat to Sediment Wildlife? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddemann, T.; Haupt, D.; Sievers, M.; Kunz, U. Elektrochemische Reaktoren Für Die Wasserbehandlung. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2019, 91, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ani, I.J.; Akpan, U.G.; Olutoye, M.A.; Hameed, B.H. Photocatalytic Degradation of Pollutants in Petroleum Refinery Wastewater by TiO2- and ZnO-Based Photocatalysts: Recent Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 930–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Haque, M.J.; Kabir, M.H.; Kaiyum, M.A.; Rahman, M.S. Nano Synthesis of ZnO–TiO2 Composites by Sol-Gel Method and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial, Optical and Photocatalytic Activities. Results Mater. 2021, 11, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, G.K.; Rajput, J.K.; Pathak, T.K.; Kumar, V.; Purohit, L.P. Synthesis of ZnO:TiO2 Nanocomposites for Photocatalyst Application in Visible Light. Vacuum 2019, 160, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H.T.; Truong, H.B.; Nguyen, T.C. ZnO/TiO2 Photocatalytic Nanocomposite for Dye and Bacteria Removal in Wastewater. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 085003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridevi, K.P.; Prasad, L.G.; Sangeetha, B.; Sivakumar, S. Structural and Optical Study of ZnO-TiO2 Nanocomposites. J. Ovonic Res. 2022, 18, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharma, H.N.C.; Jaafar, J.; Widiastuti, N.; Matsuyama, H.; Rajabsadeh, S.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Jafri, N.N.M.; Suhaimin, N.S.; Nasir, A.M.; et al. A Review of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2)-Based Photocatalyst for Oilfield-Produced Water Treatment. Membranes 2022, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Lin, T.-S. Enhancement of Visible-Light Photocatalytic Efficiency of TiO2 Nanopowder by Anatase/Rutile Dual Phase Formation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Ji, J.; Tang, C.; Yu, S.; Zou, W.; Dong, L. Pt Deposites on TiO2 for Photocatalytic H2 Evolution: Pt Is Not Only the Cocatalyst, but Also the Defect Repair Agent. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, R.; Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P. Photocatalytic Reduction of Acetophenone in Membrane Reactors under UV and Visible Light Using TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 Catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 274, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavorato, C.; Argurio, P.; Mastropietro, T.F.; Pirri, G.; Poerio, T.; Molinari, R. Pd/TiO2 Doped Faujasite Photocatalysts for Acetophenone Transfer Hydrogenation in a Photocatalytic Membrane Reactor. J. Catal. 2017, 353, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Wijenayaka, L.A.; Siriwardana, K.; Dahanayake, D.; Nalin De Silva, K.M. Gold Nanoparticle Decorated Titania for Sustainable Environmental Remediation: Green Synthesis, Enhanced Surface Adsorption and Synergistic Photocatalysis. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 29594–29602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Cao, S.W.; Wang, Z.; Shahjamali, M.M.; Loo, S.C.J.; Barber, J.; Xue, C. Mesoporous Plasmonic Au-TiO2 Nanocomposites for Efficient Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Water Reduction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 17853–17861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelakanta Reddy, I.; Jayashree, N.; Manjunath, V.; Kim, D.; Shim, J. Photoelectrochemical Studies on Metal-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanostructures under Visible-Light Illumination. Catalysts 2020, 10, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre-Sánchez, M.; Lavorato, C.; Puche, M.; Fornés, V.; Molinari, R.; Garcia, H. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation by Using Dye-Sensitized Graphene Oxide as a Photocatalyst. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16774–16783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulska, E.; Breczko, J.; Basa, A.; Dubis, A.T. Rare-Earth Metals-Doped Nickel Aluminate Spinels for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, R.; Jamali-Sheini, F.; Cheraghizade, M.; Khosravi-Gandomani, S.; Sáaedi, A.; Huang, N.M.; Basirun, W.J.; Azarang, M. Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Strontium-Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Mater Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 32, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithira, P.R.; Theresa John, T. Correlation among Oxygen Vacancy and Doping Concentration in Controlling the Properties of Cobalt Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 496, 165928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isai, K.A.; Shrivastava, V.S. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Using ZnO and 2%Fe–ZnO Semiconductor Nanomaterials Synthesized by Sol–Gel Method: A Comparative Study. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Raza, Z.A. Arsenic Removal Approaches: A Focus on Chitosan Biosorption to Conserve the Water Sources. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 1196–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Jia, Z.; Lu, H.-B.; Habibi, D.; Zhang, L.-C. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Degradation of Mordant Black 11 with ZnO Nanoparticles under UV–Vis Light. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güy, N.; Çakar, S.; Özacar, M. Comparison of Palladium/Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts Prepared by Different Palladium Doping Methods for Congo Red Degradation. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2016, 466, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.; Yang, B.; Wu, M.; Xu, J.; Fu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Guo, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C. Synthesis of Ag/ZnO Nanorods Array with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 182, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Abou-Gamra, Z.M.; ALshakhanbeh, M.A.; Medien, H. Control Synthesis of Metallic Gold Nanoparticles Homogeneously Distributed on Hexagonal ZnO Nanoparticles for Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 12, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.B.; Patil, K.R.; Pardeshi, S.K. Ecofriendly Synthesis and Solar Photocatalytic Activity of S-Doped ZnO. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byzynski, G.; Melo, C.; Volanti, D.P.; Ferrer, M.M.; Gouveia, A.F.; Ribeiro, C.; Andrés, J.; Longo, E. The Interplay between Morphology and Photocatalytic Activity in ZnO and N-Doped ZnO Crystals. Mater. Des. 2017, 120, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Men, Y. Synthesis and High Photocatalytic Activity of Eu-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 10375–10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, W.; Faisal, S.M.; Owais, M.; Bahnemann, D.; Muneer, M. Facile Fabrication of Highly Efficient Modified ZnO Photocatalyst with Enhanced Photocatalytic, Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 78335–78350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanakousar, F.M.; Vidyasagar, C.C.; Jiménez-Pérez, V.M.; Prakash, K. Recent Progress on Visible-Light-Driven Metal and Non-Metal Doped ZnO Nanostructures for Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 140, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dontsova, T.A.; Yanushevska, O.I.; Nahirniak, S.V.; Kutuzova, A.S.; Krymets, G.V.; Smertenko, P.S. Characterization of Commercial TiO2P90 Modified with ZnO by the Impregnation Method. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 9378490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, X. Zn–ZnO@TiO2 Nanocomposite: A Direct Electrode for Nonenzymatic Biosensors. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 7138–7149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, F.; Gorji, P.; Mobarakeh, M.S.; Mozaffari, H.R.; Masaeli, R.; Safaei, M. Optimized Synthesis of Xanthan Gum/ZnO/TiO2 Nanocomposite with High Antifungal Activity against Pathogenic Candida Albicans. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 7255181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, A.; Ringwal, S.; Pandey, M.; Taha Yassin, M. Plant-Mediated Z-Scheme ZnO/TiO2-NCs for Antibacterial Potential and Dye Degradation: Experimental and DFT Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Saion, E.; Al-Hada, N.; Soltani, N. A Simple Up-Scalable Thermal Treatment Method for Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles. Metals 2015, 5, 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathumba, P.; Bilibana, M.P.; Olatunde, O.C.; Onwudiwe, D.C. X-Ray Diffraction Profile Analysis of Green Synthesized ZnO and TiO2 Nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 075011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fu, X.; Han, Y.; Chang, E.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Qi, X. Preparation, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2/ZnO Nanocomposites. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 321459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Rajamani, A.K.; Masilamani, C.; Chinnappan, I.; Ramamoorthy, U.; Kaviyarasu, K. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Doped TiO2 Nanocomposites for Their Potential Photocatalytic and Antimicrobial Applications. Catalysts 2023, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuste, M.; Escobar-Galindo, R.; Benito, N.; Palacio, C.; Martínez, O.; Albella, J.M.; Sánchez, O. Effect of the Incorporation of Titanium on the Optical Properties of ZnO Thin Films: From Doping to Mixed Oxide Formation. Coatings 2019, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, Y.S.; Yuliati, L. Activity Enhancement of P25 Titanium Dioxide by Zinc Oxide for Photocatalytic Phenol Degradation. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2021, 16, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanakrishnan, H.; Mani, N.; Jayaram, A.; Suruttaiyaudiyar, P.; Chellamuthu, M.; Shimomura, M. Engineering of Mono-Dispersed Mesoporous TiO2 over 1-D Nanorods for Water Purification under Visible Light Irradiation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 18768–18777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abassi, K.; Ben Ali, A.; Ben Chaabane, T.; Younas, M.; Pecoraro, C.M.; Altalhi, T.; Mezni, A.; Bellardita, M. Investigating the Photocatalytic Activity of Hybrid ZnO@TiO2 Nanocomposites towards Dyes Degradation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 344, 131172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintcheva, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kulinich, S.A. Hybrid TiO2-ZnO Nanomaterials Prepared Using Laser Ablation in Liquid. Materials 2020, 13, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Bakar Mohamad, A.; Takriff, M.S.; Sopian, K. The Effect of Process Parameters on the Size of ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized via the Sol–Gel Technique. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 550, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, D.; Vara Lakshmi, B.; Sunandana, C.S. Two-Step Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2012, 407, 4537–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, A.; Veselinović, L.; Škapin, S.D.; Marković, S.; Uskoković, D. Controlled Mechanochemically Assisted Synthesis of ZnO Nanopowders in the Presence of Oxalic Acid. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 3716–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | Zn@TiO2 NPs | Average Grain Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pristine ZnO | 63.52 |

| 2 | Pristine TiO2 | 29.10 |

| 3 | Zn@TiO2-1 | 28.01 |

| 4 | Zn@TiO2-2 | 37.29 |

| 5 | Zn@TiO2-3 | 23.51 |

| 6 | Zn@TiO2-4 | 11.41 |

| Sr. No | Characteristics Band | Molecular Vibration | Wavenumber (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≡Ti-O-Ti≡ | Bending | 600–800 |

| 2 | TiO2 | Lattice Vibration | 1400 |

| 3 | ≡Ti-O-Ti≡ | Stretching | 550 |

| 4 | Zn-O | Stretching | 500 |

| 5 | Zn-O-Ti | Stretching | 650 |

| 6 | -OH | Bending | 1637 |

| 7 | -OH | Stretching | 3200 |

| 8 | C-H | Stretching | 2496 |

| 9 | C=O | Stretching | 1300–1600 |

| Sr. No | Sample Name | Particle Size (nm) | Zeta Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pristine ZnO | 2605.0 | −5.47 |

| 2 | Pristine TiO2 | 831.3 | −6.89 |

| 3 | Zn@TiO2-1 | 1301.0 | −10.90 |

| 4 | Zn@TiO2-2 | 1287.0 | −8.75 |

| 5 | Zn@TiO2-3 | 3070.0 | −13.10 |

| 6 | Zn@TiO2-4 | 1361.0 | −13.30 |

| 7 | Ti@ZnO-1 | 311.70 | −9.56 |

| 8 | Ti@ZnO-2 | 372.20 | −6.15 |

| 9 | Ti@ZnO-3 | 319.80 | −6.20 |

| 10 | Ti@ZnO-4 | 1294.00 | −5.11 |

| Sr. No. | Peaks | TiO2 (Anatase) | TiO2 (Rutile) | ZnO (Wurtzite) | Cubic ZnTiO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.28 | √ | |||

| 2 | 32.73 | √ | |||

| 3 | 35.25 | √ | |||

| 4 | 36.25 | √ | |||

| 5 | 37.8 | √ | |||

| 6 | 38.58 | √ | |||

| 7 | 48.05 | √ | |||

| 8 | 54.32 | √ | |||

| 9 | 55.06 | ||||

| 10 | 56.6 | √ | |||

| 11 | 56.79 | √ | |||

| 12 | 62.86 | √ | |||

| 13 | 63.40 | √ | |||

| 14 | 67.96 | √ | |||

| 15 | 68.72 | √ | |||

| 16 | 69.07 | √ | |||

| 17 | 69.79 | √ | |||

| 18 | 70.91 | √ | |||

| 19 | 75.03 | √ | |||

| 20 | 78.82 | √ |

| Photocatalysts | Zinc Acetate Dihydrate (gm) | Titanium Iso Propoxide (mL) | Solvent (mL) | Oxalic Acid (gm) | ZnO NPs | TiO2 NPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine ZnO | 1.75 | - | 50 | 3.25 | - | - |

| Zn@TiO2-1 | 1.40 | - | 50 | 2.60 | - | 1 |

| Zn@TiO2-2 | 1.05 | - | 50 | 1.95 | - | 2 |

| Zn@TiO2-3 | 0.70 | - | 50 | 1.30 | - | 3 |

| Zn@TiO2-4 | 0.35 | - | 50 | 0.65 | - | 4 |

| Pristine TiO2 | - | 5 | 50 | - | - | - |

| Ti@ZnO-1 | - | 4 | 50 | - | 1 | - |

| Ti@ZnO-2 | - | 3 | 50 | - | 2 | - |

| Ti@ZnO-3 | - | 2 | 50 | - | 3 | - |

| Ti@ZnO-4 | - | 1 | 50 | - | 4 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Raval, I.; Shukla, A.; Gandhi, V.G.; Dang, K.D.; Nair, N.G.; Nguyen, V.-H. Interface-Engineered Zn@TiO2 and Ti@ZnO Nanocomposites for Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Levofloxacin. Catalysts 2026, 16, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010109

Raval I, Shukla A, Gandhi VG, Dang KD, Nair NG, Nguyen V-H. Interface-Engineered Zn@TiO2 and Ti@ZnO Nanocomposites for Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Levofloxacin. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaval, Ishita, Atindra Shukla, Vimal G. Gandhi, Khoa Dang Dang, Niraj G. Nair, and Van-Huy Nguyen. 2026. "Interface-Engineered Zn@TiO2 and Ti@ZnO Nanocomposites for Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Levofloxacin" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010109

APA StyleRaval, I., Shukla, A., Gandhi, V. G., Dang, K. D., Nair, N. G., & Nguyen, V.-H. (2026). Interface-Engineered Zn@TiO2 and Ti@ZnO Nanocomposites for Advanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Levofloxacin. Catalysts, 16(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010109