Fluorine-Substituted Covalent Organic Framework/Anodized TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

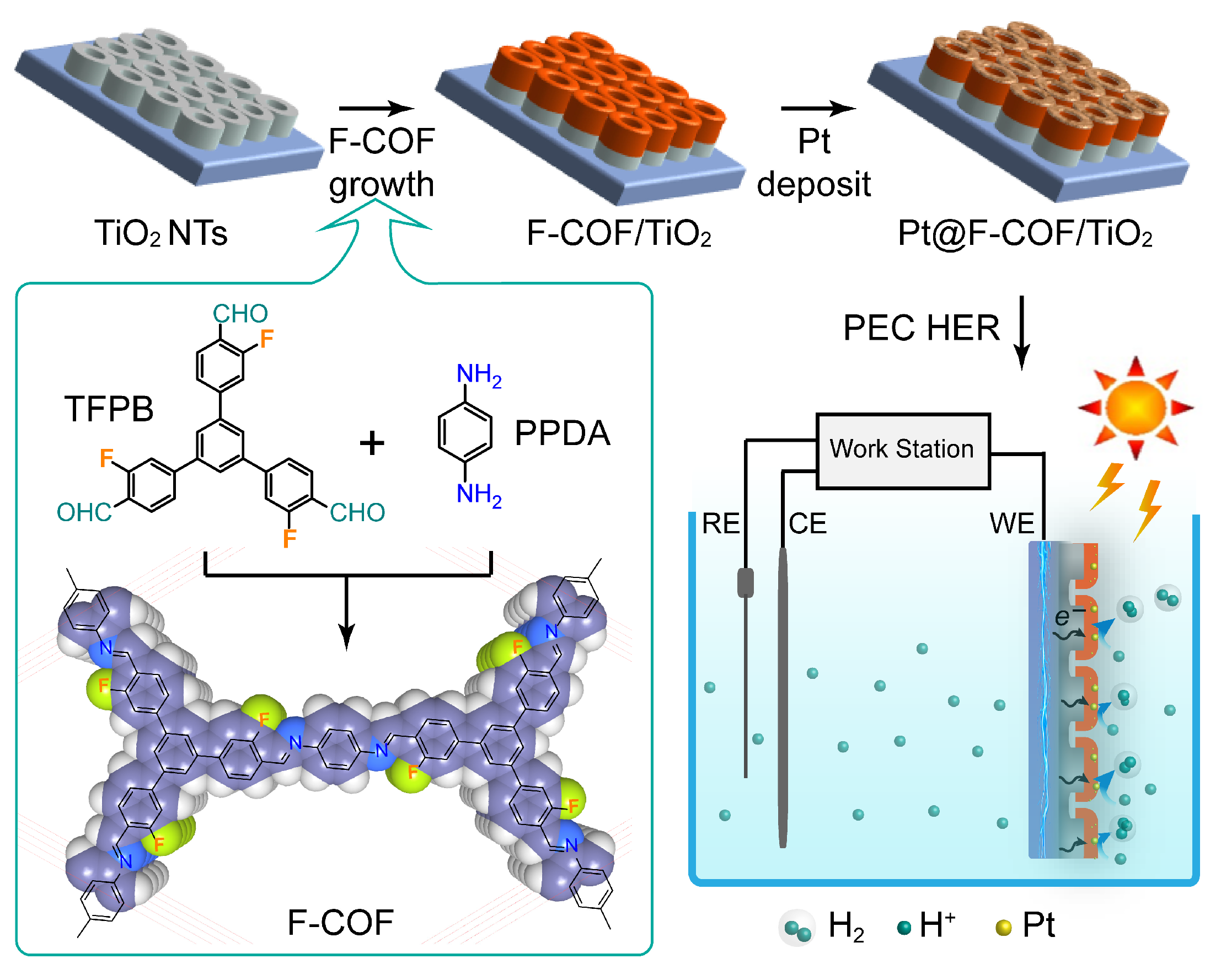

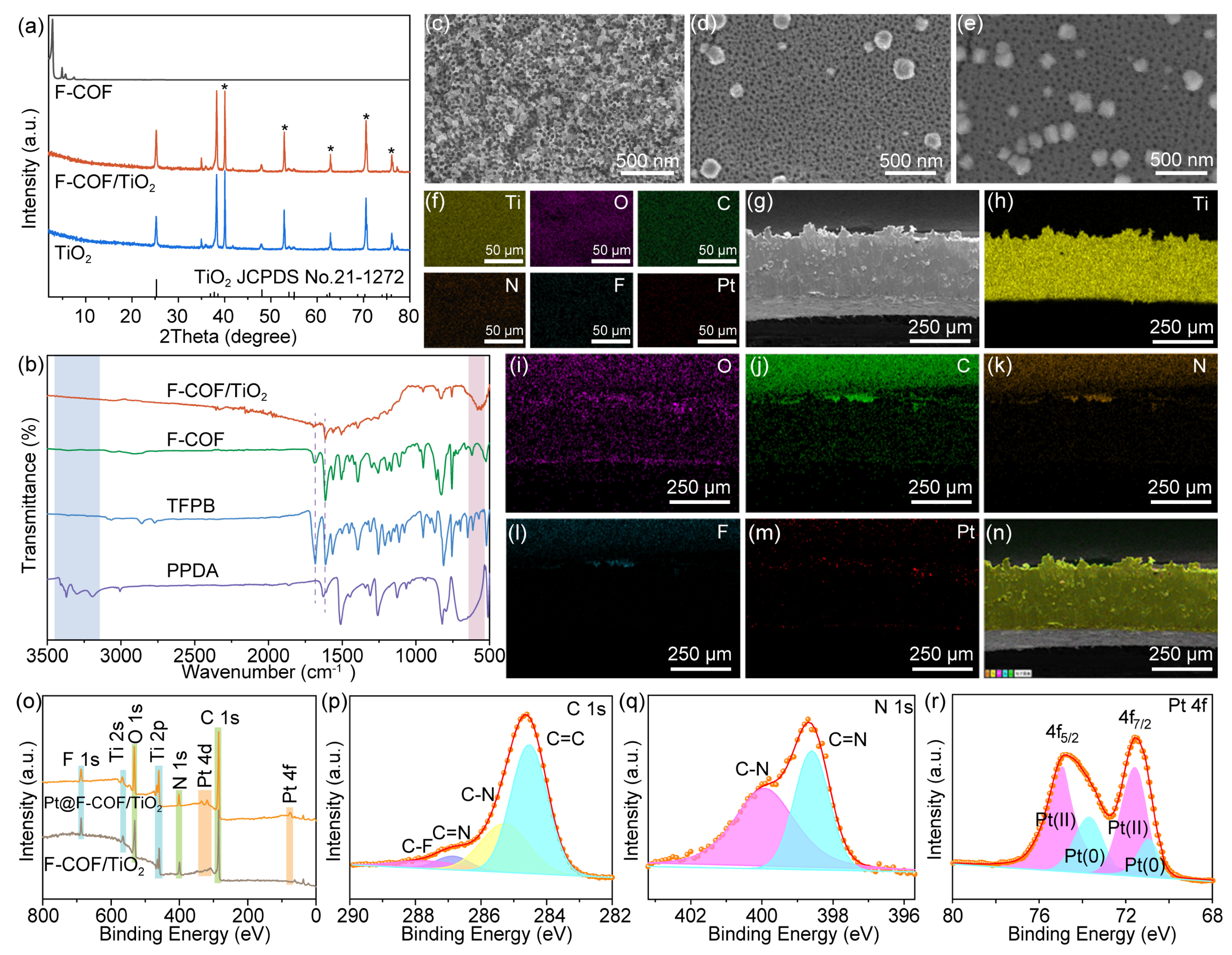

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

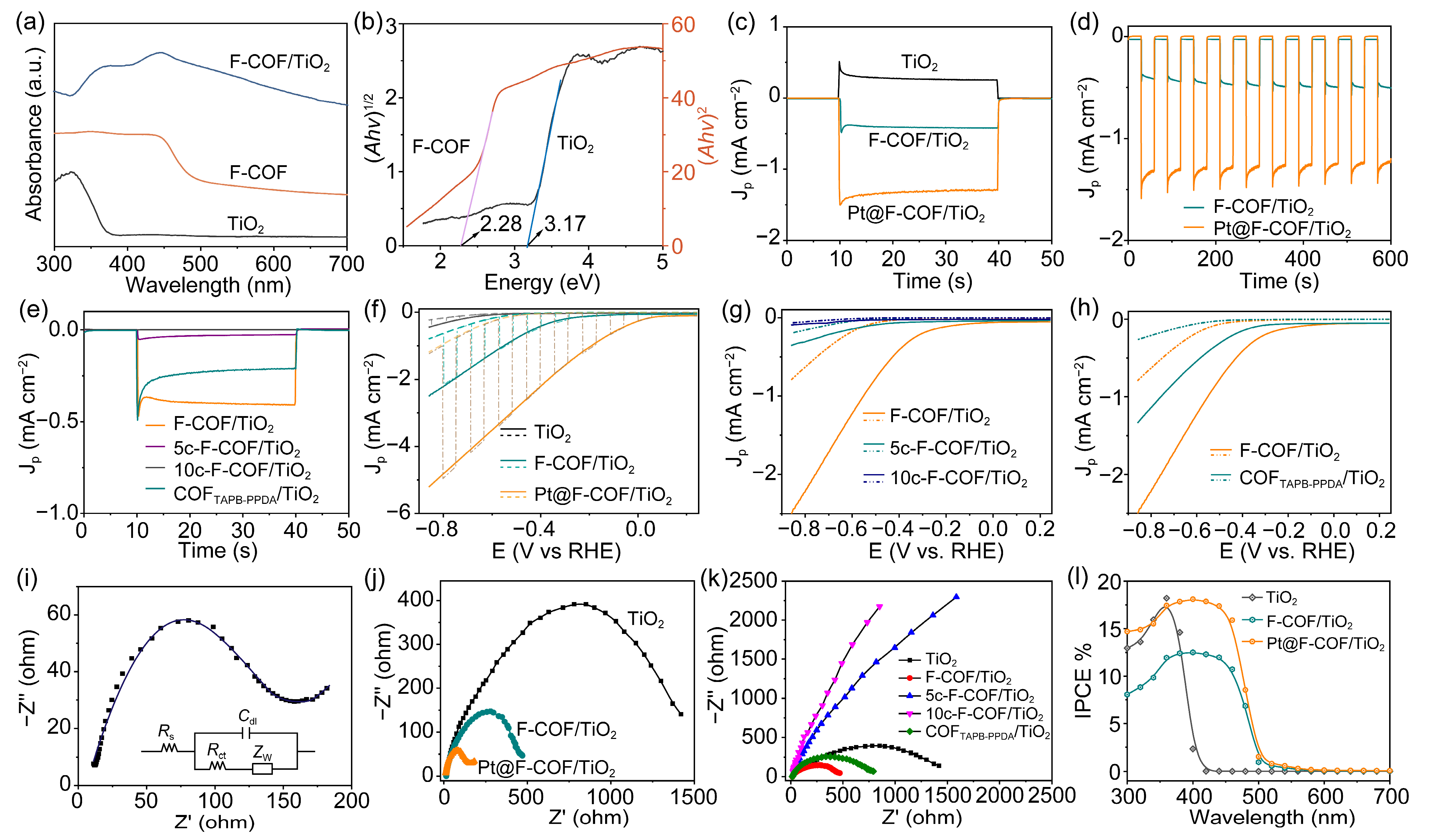

2.2. General Photoelectrochemical Performance

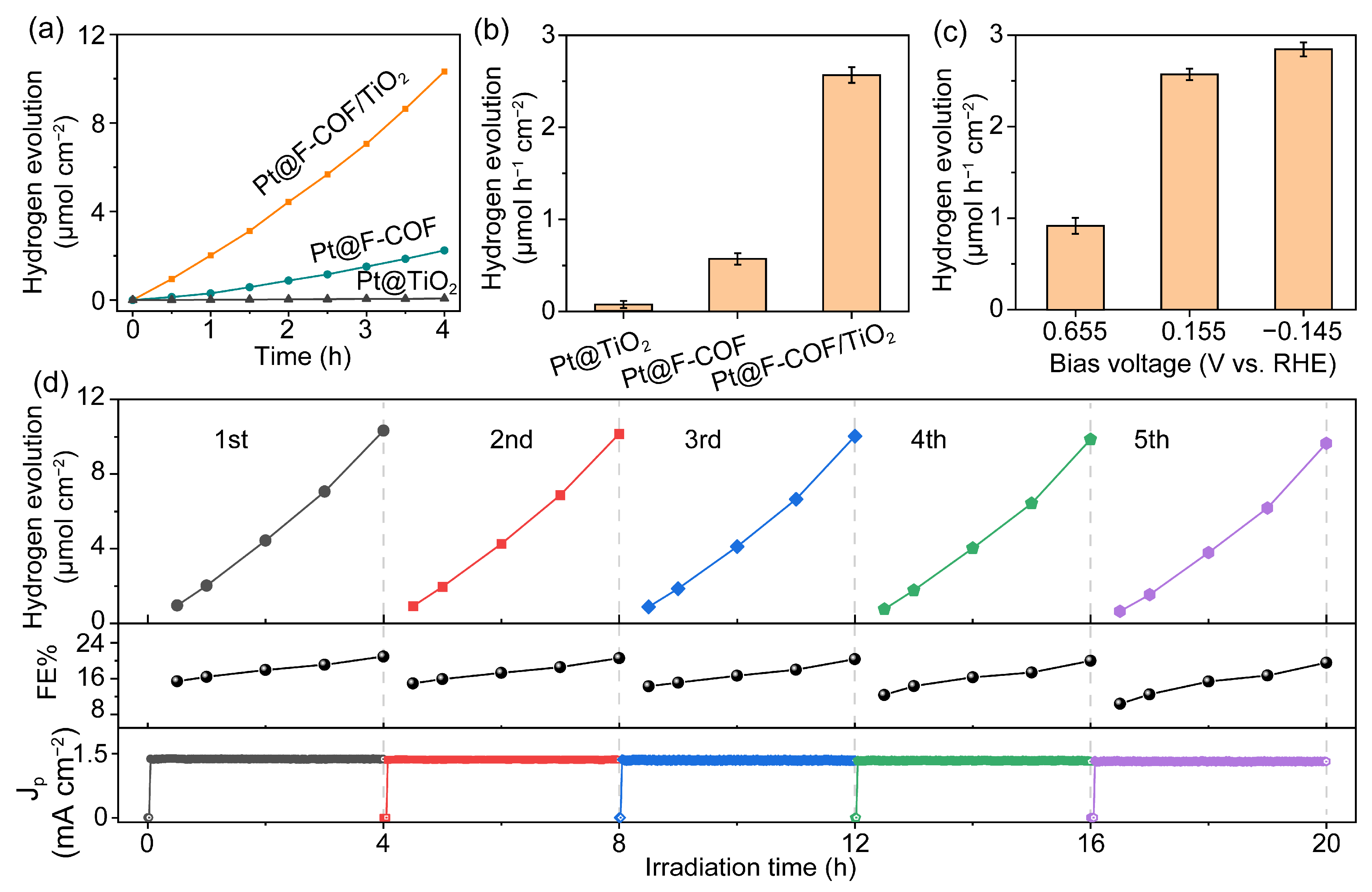

2.3. Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution

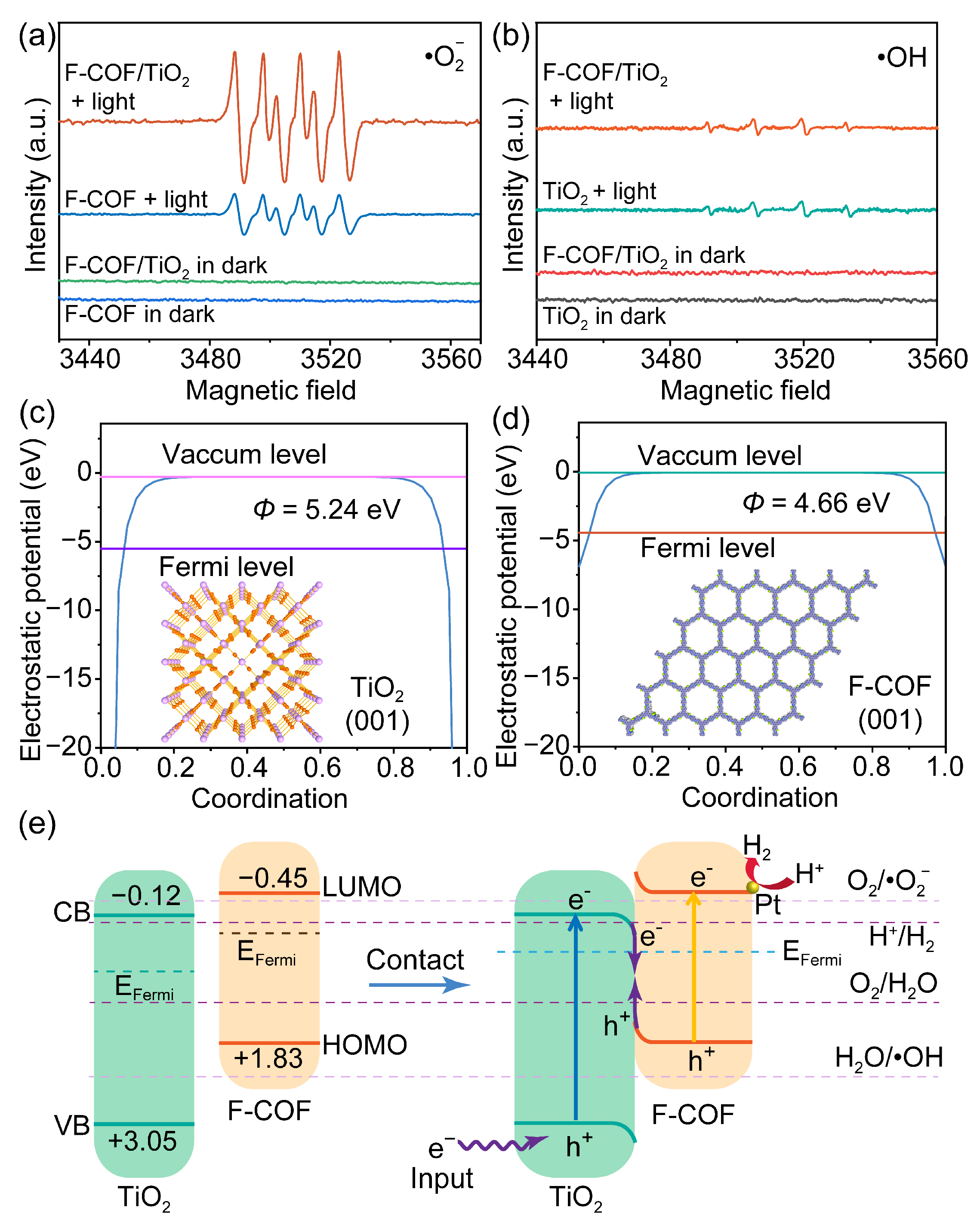

2.4. Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of F-COF Powders

3.2. Synthesis of F-COF Films on Anodized TiO2 Substrates

3.3. Fabrication of Pt@F-COF/TiO2 Electrodes

3.4. General Methods

3.5. Modeling Methods

3.6. Photoelectrochemical Performance and Hydrogen Evolution

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, P.; Navid, I.A.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, P.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, B.; Sun, K.; Mi, Z. Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting. Nature 2023, 613, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisatomi, T.; Domen, K. Reaction systems for solar hydrogen production via water splitting with particulate semiconductor photocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yi, P.; Huang, M.; Zhang, L. Coupled amorphous NiFeP/cystalline Ni3S2 nanosheets enables accelerated reaction kinetics for high current density seawater electrolysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 352, 124028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xue, L.; Fu, X.; Long, J. Recent advancements in photoelectrochemical water splitting for hydrogen production. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, F.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Li, G. A novel approach for achieving high-efficiency photoelectrochemical water oxidation in InGaN nanorods grown on Si system: MXene nanosheets as multifunctional interfacial modifier. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Meena, B.; Subramanyam, P.; Suryakala, D.; Subrahmanyam, C. Recent trends in photoelectrochemical water splitting: The role of cocatalysts. NPG Asia Mater. 2022, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.M.; Rosei, F. Quantum dots-based photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution from water splitting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.J.; Ye, Z.; Tang, S.; Navid, I.A.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Pan, Y.; Mi, Z. Concentrated solar light photoelectrochemical water splitting for stable and high-yield hydrogen production. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2309548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, K.R.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, P.; Navid, I.A.; Batista, V.S.; Mi, Z. Pt nanoclusters on GaN nanowires for solar-assisted seawater hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Du, Z.; He, F.; Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Tang, K. Cobalt carbonate hydroxide assisted formation of self-supported CoNi-based metal–organic framework nanostrips as efficient electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 15566–15573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El ouardi, M.; El Idrissi, A.; Arab, M.; Zbair, M.; Haspel, H.; Saadi, M.; Ait Ahsaine, H. Review of photoelectrochemical water splitting: From quantitative approaches to effect of sacrificial agents, oxygen vacancies, thermal and magnetic field on (photo)electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 1044–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Fei, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Fabrication of NiFe-MOF/cobalt carbonate hydroxide hydrate heterostructure for a high-performance electrocatalyst of oxygen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 917, 165511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, S.; Hou, D.; Wang, W.; Li, G. Functionalized UiO-66 induces shallow electron traps in heterojunctions with InN for enhanced photocathodic water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 685, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Liang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Li, G. Core–shell InN/PM6 Z-scheme heterojunction photoanodes for efficient and stable photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 25671–25682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, C.; Pi, Y.; Fang, Q.; Liu, J. Hollow covalent organic framework (COF) nanoreactors for sustainable photo/electrochemical catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 523, 216240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, D. Photocatalysis with covalent organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 3182–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z. 2D covalent organic frameworks as photocatalysts for solar energy utilization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2200108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Deng, W.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Bi, J.; Yu, Y. Exciton dipole orientation and dynamic reactivity synergistically enable overall water splitting in covalent organic frameworks. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 5830–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Bi, R.; Peng, Z.; Song, A.; Zhang, R.; He, H.; Qi, J.; Gong, J.; Niu, C.; et al. Reducing the exciton binding energy of covalent organic framework through π-bridges to enhance photocatalysis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.E.; Das, P.; Thomas, A. Two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks: Structural insights across different length scales and their impact on photocatalytic efficiency. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 3138–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Deng, Q.; Deng, W. Rational design of covalent organic frameworks as photocatalysts for water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Huang, C.; Hao, L.; Liang, G.; Zhang, P.; Yue, Q.; Li, X. Ground-state charge transfer in single-molecule junctions covalent organic frameworks for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Xie, S.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Shi, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X. Dual–acceptor engineering in pyrene-based covalent organic frameworks for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2402395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Kato, S.; Zajaczkowska, H.; Marszalek, T.; Blom, P.W.M.; Ie, Y. Effects of fluorine substitution in quinoidal oligothiophenes for use as organic semiconductors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 3580–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Li, R. Recent advances and perspectives for solar-driven water splitting using particulate photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 3561–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Tan, H.; Ye, N.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Luo, M.; Guo, S. Fluorination of covalent organic framework reinforcing the confinement of Pd nanoclusters enhances hydrogen peroxide photosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 19877–19884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Shan, M.; Wang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Song, J.; Li, Z. Fluorine-substituted donor-acceptor covalent organic frameworks for efficient photocatalyst hydrogen evolution. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 5368–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lu, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Yan, H. A highly fluorine-functionalized 2D covalent organic framework for promoting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 537, 148082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Xi, X.; Zhang, J. Functional groups-dependent Tp-based COF/MgIn2S4 S-scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Shen, R.; Huang, C.; Huang, K.; Liang, G.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. 2D/2D hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks/covalent organic frameworks S-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202414229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Liang, G.; Hao, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. In situ synthesis of chemically bonded 2D/2D covalent organic frameworks/O-Vacancy WO3 Z-scheme heterostructure for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-P.; Tang, H.-L.; Dong, H.; Gao, M.-Y.; Li, C.-C.; Sun, X.-J.; Wei, J.-Z.; Qu, Y.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhang, F.-M. Covalent-organic framework based Z-scheme heterostructured noble-metal-free photocatalysts for visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 4334–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Wang, R.; Shao, P.-P.; Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Zang, S.-Q.; Mak, T.C.W. Prefabricated covalent organic framework nanosheets with double vacancies: Anchoring cu for highly efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 25094–25100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Sun, C.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Sun, H. Copper-surface-mediated synthesis of sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic framework photocathodes for photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202402930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, B.; Shang, H. A heterostructure photoelectrode based on two-dimensional covalent organic framework film decorated TiO2 nanotube arrays for enhanced photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Molecules 2023, 28, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; He, T.; Zhong, L.; Liu, X.; Zhen, W.; Xue, C.; Li, S.; Jiang, D.; Liu, B. 2,4,6-Triphenyl-1,3,5-triazine based covalent organic frameworks for photoelectrochemical H2 evolution. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2002191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Rodriguez-Camargo, A.; Xia, M.; Mucke, D.; Guntermann, R.; Liu, Y.; Grunenberg, L.; Jimenez-Solano, A.; Emmerling, S.T.; Duppel, V.; et al. Covalent organic framework nanoplates enable solution-processed crystalline nanofilms for photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 10291–10300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Lv, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, G.-Y. Covalent organic frameworks meet titanium oxide. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 19443–19469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.T.; Croxall, M.P.; Lu, C.; Goh, M.C. TiO2–NGQD composite photocatalysts with switchable photocurrent response. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, J. Boosting exciton dissociation and charge transfer in fluorine-substituted covalent organic frameworks with biomimetic electron pumps for remarkable photocatalytic extraction of uranium. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 3503–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.E.; Hong, S.-P.; Choi, S.; Kim, C.; Ji, S.G.; Park, I.J.; Lee, S.A.; Yang, J.W.; Lee, T.H.; Sohn, W.; et al. Boosting unassisted alkaline solar water splitting using silicon photocathode with TiO2 nanorods decorated by edge-rich MOS2 nanoplates. Small 2021, 17, 2103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, T.P.; Piraviperumal, M.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Govindasamy, M. TiO2 hole transport layer incorporated in a thermally evaporated Sb2Se3 photoelectrode exhibiting low onset potential for photoelectrochemical applications. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 16936–16948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Liu, C.; Gong, L.; Wang, M. Boosting the performance of a silicon photocathode for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production by immobilization of a cobalt tetraazamacrocyclic catalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Cai, H.; Sun, F.; Jiang, F. Efficient carrier transfer route via the bridge of C60 particle to TiO2 nanoball based coverage layer enables stable and efficient cadmium free gese photocathode for solar hydrogen evolution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2021, 297, 120437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Miao, H.; Shi, G.; Wong, P.K. A high-performance TiO2 protective layer derived from non-high vacuum technology for a Si-based photocathode to enhance photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 16605–16616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.S.; Murugan, C.; Pandikumar, A. Uplifting the charge carrier separation and migration in Co-doped CuBi2O4/TiO2 p-n heterojunction photocathode for enhanced photoelectrocatalytic water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Q.; Tóth, P.S.; Vass, Á.; Rajeshwar, K.; Janáky, C. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution on macroscopic electrodes of exfoliated snse flakes. Appl. Catal. A 2023, 661, 119233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Liu, S.; Wu, L.; Tang, D.; Xue, J.; Wang, J.; Ji, H.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. Bias distribution and regulation in photoelectrochemical overall water-splitting cells. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Du, A.; Irani, R.; Van De Krol, R.; Abdi, F.F.; Ng, Y.H. Low-bias photoelectrochemical water splitting via mediating trap states and small polaron hopping. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.S.; Hsiao, K.-C.; Wu, M.-C.; Yun, Y.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Yong, K. Spatial separation of cocatalysts on z-scheme organic/inorganic heterostructure hollow spheres for enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution and in-depth analysis of the charge-transfer mechanism. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2200172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; He, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Fang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, D.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. In situ photodeposition of platinum clusters on a covalent organic framework for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Moniz, S.J.A.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T.; Tang, J. Photoelectrochemical devices for solar water splitting – materials and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4645–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, P.; Qi, H.; Sun, B. Fluorine-Substituted Covalent Organic Framework/Anodized TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts 2026, 16, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010108

Niu Y, Liu F, Li P, Qi H, Sun B. Fluorine-Substituted Covalent Organic Framework/Anodized TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Yuanyuan, Feng Liu, Ping Li, Hongbin Qi, and Bing Sun. 2026. "Fluorine-Substituted Covalent Organic Framework/Anodized TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010108

APA StyleNiu, Y., Liu, F., Li, P., Qi, H., & Sun, B. (2026). Fluorine-Substituted Covalent Organic Framework/Anodized TiO2 Z-Scheme Heterojunction for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Evolution. Catalysts, 16(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010108