A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

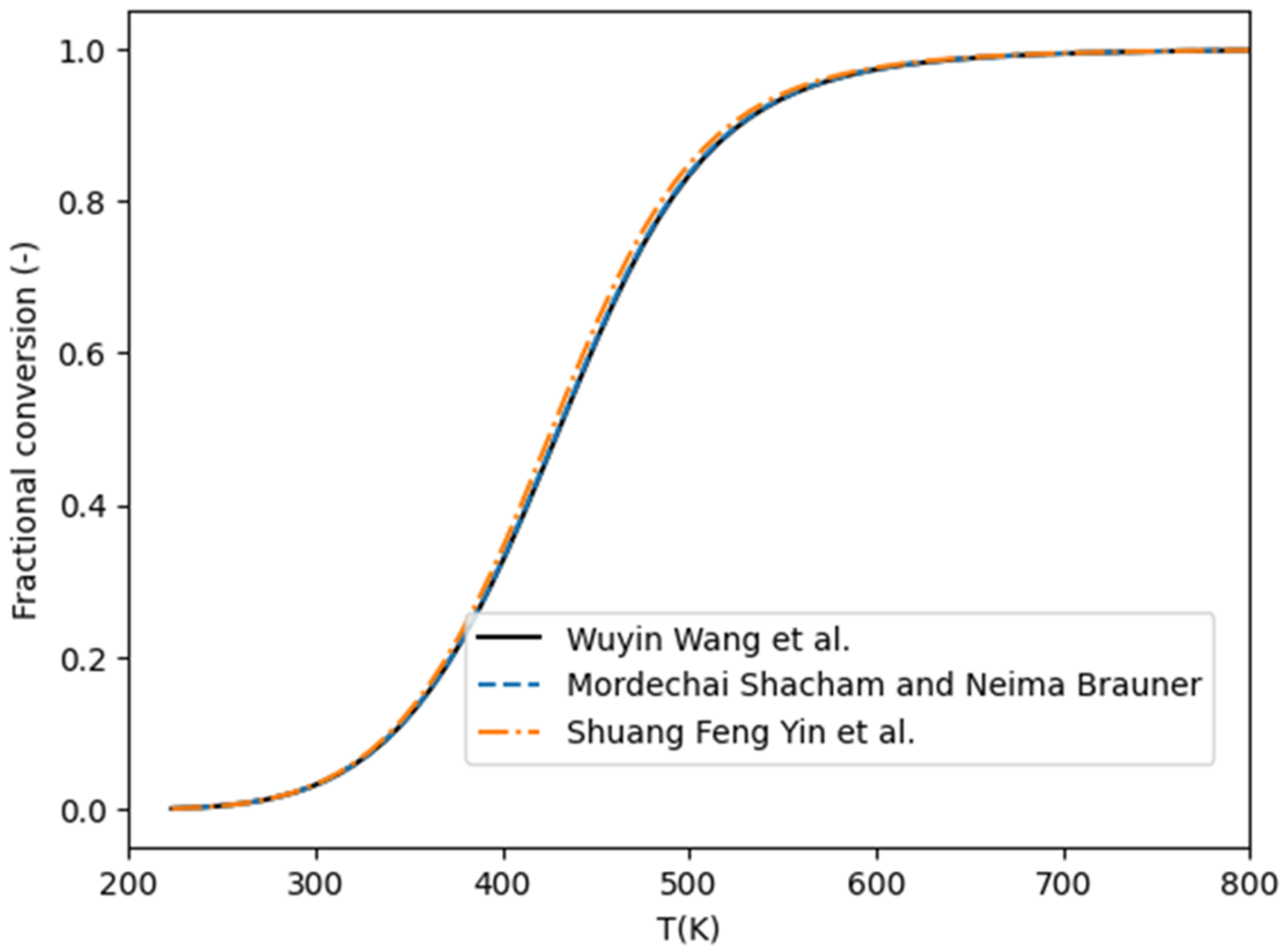

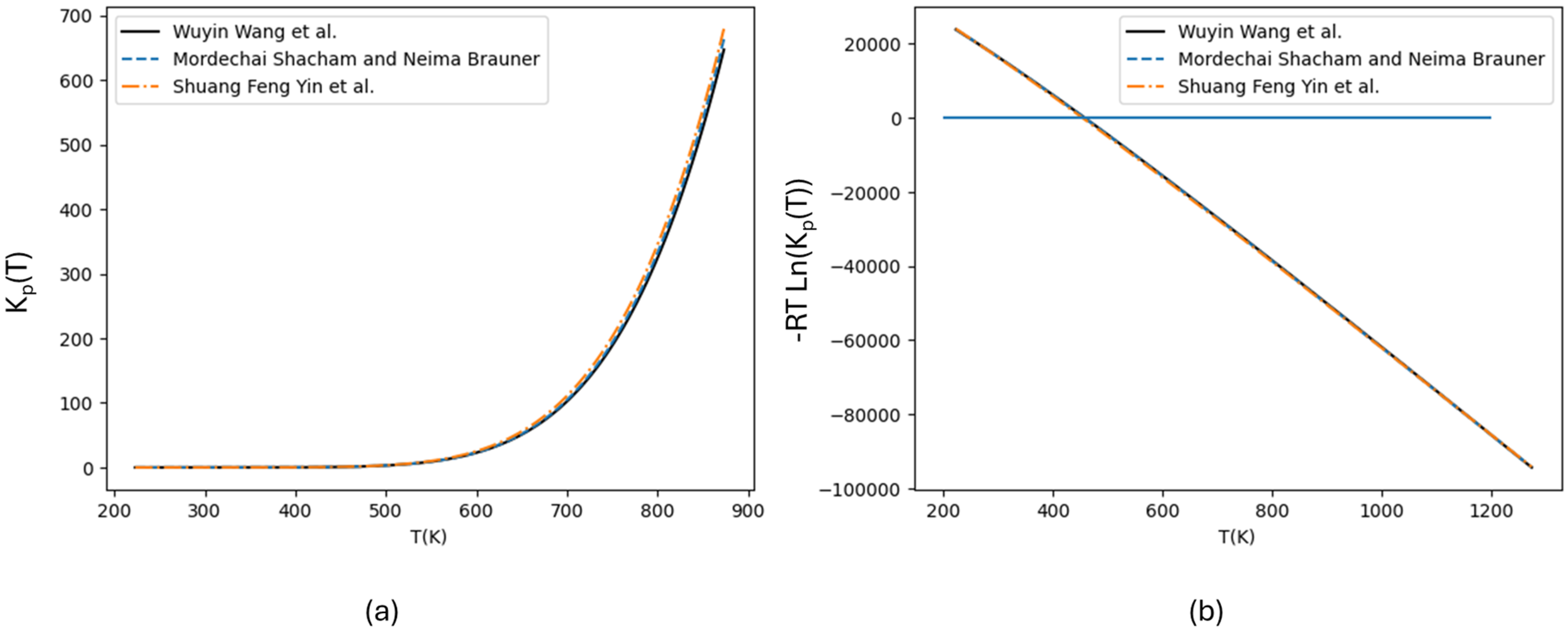

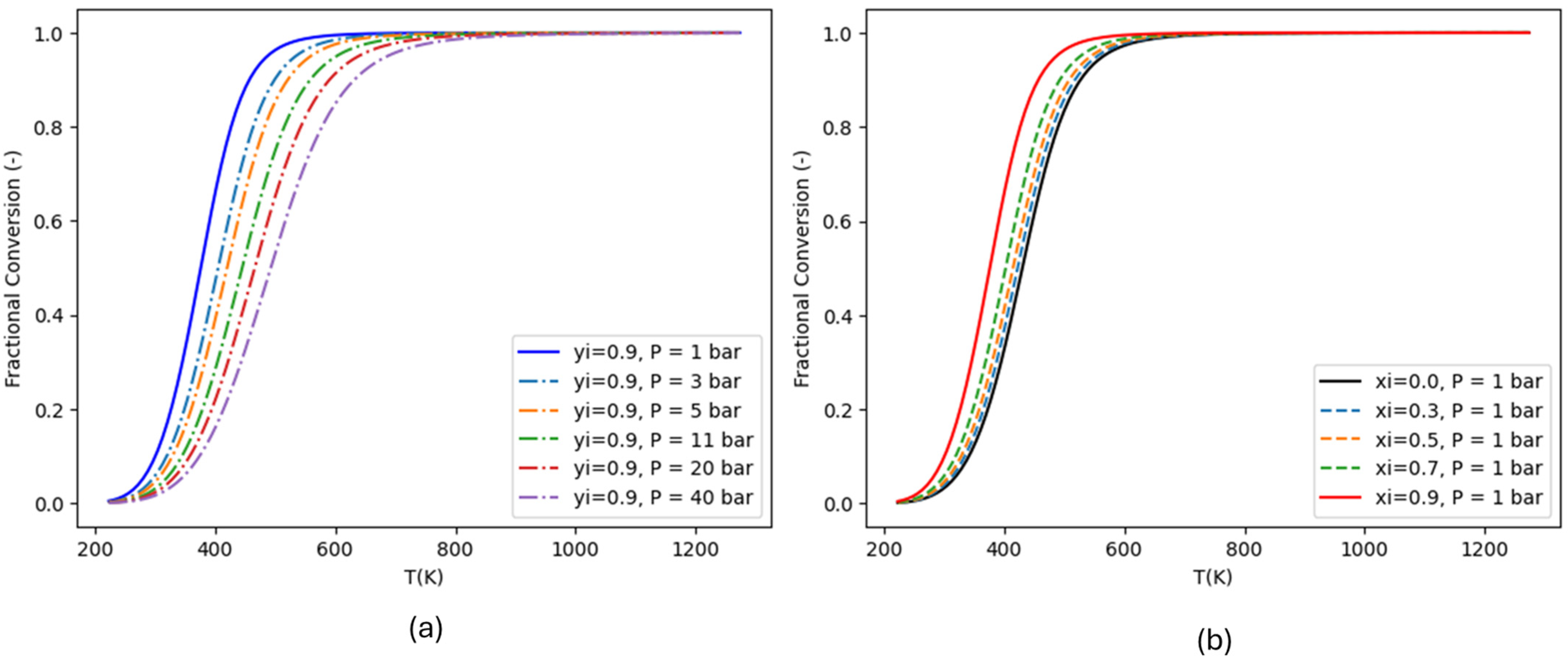

2. Thermodynamics

3. Catalysts

3.1. Ru–Based Catalysts

3.2. Metal Loadings and Synthesis Methods

3.3. Support Effect

3.4. Promoters and Basicity Effects

3.5. Transition Metal-Based Catalysts as Alternatives to Ruthenium

3.5.1. Ni-Based Catalysts

3.5.2. Co–Based Catalysts

| Catalyst | Metals (%) | Catalyst Preparation | WHSV (NmLNH3 gCat−1 h−1) | WHSV (NmLNH3 gMe−1 h−1) | NH3 (%) | T (°C) | Conv (%) | P (bar) | Productivity (mmolNH3 gRu−1 min−1) | H2 Production (mmolH2 gRu−1min−1) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru/Al2O3 | 0.5 | Acetone-assisted WI 1 | - | - | 100 | 580 | - | 1 | - | - | [42] |

| Ru/La (50%)-Al2O3 | 0.7 | WI | 2300 | 328,571 | 10 | 500 | 99 | 1 | 242 | 363 | [59] |

| Ru/Al2O3 | 4.7 | Ethanol-assisted WI | 30,000 | 526,315 | 100 | 500 | 85 | 1 | 380 | 570 | [41] |

| (4.5%) Na-Ru/AC | 2 | WI | 2000 | 100,000 | 10 | 500 | 99 | 1 | 74 | 110 | [15] |

| Ru/MgO (111) | 3 | Ru3(CO)12-I/D 2 | 30,000 | 1,000,000 | 100 | 425 | 99 | 1 | 744 | 1104 | [14] |

| Ru@13X | 4.8 | IE 3 | 15,000 | 312,500 | 100 | 450 | 52.5 | 1 | 122 | 183 | [49] |

| 0.8 | 15,000 | 1,875,000 | 26.5 | 369 | 554 | ||||||

| 4.8 | 30,000 | 625,000 | 38.5 | 179 | 268 | ||||||

| 0.25 | 30,000 | 12,000,000 | 8.1 | 723 | 1084 | ||||||

| Ru/Al2O3 | 8.5 | C 4-WI | 286 | 3361 | 100 | 500 | 99.7 | 1 | 2492 | 3738 | [65] |

| 98.5 | 5 | 2462 | 3693 | ||||||||

| 97.2 | 10 | 2429 | 3644 | ||||||||

| 500 | 99.7 | 1 | 2492 | 3738 | |||||||

| 450 | 99.5 | 2487 | 3730 | ||||||||

| 400 | 99.1 | 2477 | 3715 | ||||||||

| Ru/C12A7: e− | 2.2 | CVD 5 | 15,000 | 681,818 | 100 | 400 | 70 | 1 | 355 | 532 | [37] |

| Ru/C12A7: O2− | 2 | 750,000 | 41.5 | 231 | 347 | ||||||

| Ru-K/C | 2.7 | 555,556 | 56 | 231 | 347 | ||||||

| Ru/C12A7: e− | 2.2 | 681,818 | 460 | 99 | 502 | 753 | |||||

| Ru/C12A7: O2− | 2 | 750,000 | 80 | 446 | 669 | ||||||

| Ru-K/C | 2.7 | 555,556 | 78 | 322 | 483 | ||||||

| Ru/CNFs | 3.2 | WI | 6500 | 203,125 | 100 | 500 | 99 | 1 | 150 | 224 | [44] |

| Ru/CNTs | 3.2 | 203,125 | 75 | 113 | 170 | ||||||

| Ru/CNFs | 7.9 | 82,278 | 450 | 90 | 55 | 83 | |||||

| Ru/CNFs | 3.2 | 203,125 | 70 | 106 | 159 | ||||||

| Ru/Al2O3 [Ru(NO)(NO3)] | 4 | WI | 12,000 | 300,000 | 10 | 450 | 90 | 1 | 201 | 301 | [48] |

| Ru/Al2O3 [Ru(acac)3] | 4.5 | 266,667 | 85 | 169 | 253 | ||||||

| Ru/Mg-Al/Monolith | 0.025 | NH3-assisted precipitation | 9 | 35,687 | 100 | 625 | 98 | 1 | 26 | 39 | [66] |

| Ru/Ma-Al/Foam | 0.030 | NH3-assisted precipitation | 16 | 52,766 | 93 | 36 | 54 | ||||

| Ru/Al2O3 | 0.5 | C-WI | 21 | 5130 | 100 | 4 | 6 | ||||

| Ru/CaO | 3 | Acetone assisted-WI | 9000 | 30,000 | 100 | 450 | 20 | 1 | 45 | 67 | [61] |

| Ru-5%K/CaO | 60 | 134 | 201 | ||||||||

| Ru-10%K/CaO | 90 | 201 | 301 | ||||||||

| Ru-10%K/CaO | 500 | 98 | 1 | 219 | 328 | ||||||

| 80 | 10 | 178 | 268 | ||||||||

| 65 | 20 | 145 | 217 | ||||||||

| 60 | 40 | 134 | 201 | ||||||||

| Ru/La0.8Sr0.2AlO3 | 2.55 | I 6 | 30,000 | 1,176,471 | 100 | 500 | 71.6 | 1 | 626 | 940 | [67] |

| Ru/Ba-ZrO2 | 3 | I | 3000 | 100,000 | 100 | 447 | 100 | 1 | 74 | 112 | [62] |

| Ru-Ba/ZrO2 | 10 | 7 | 11 | ||||||||

| Ru/MgO | 5 | DP 7 | 36,000 | 720,000 | 100 | 475 | 71 | 1 | 380 | 570 | [68] |

| K-Ru/MgO | 100 | 535 | 803 | ||||||||

| Ru/MgO | 4.7 | DP | 30,000 | 638,298 | 100 | 450 | 80.6 | 1 | 383 | 574 | [69] |

| Ru/K2SiO3 | 3.2 | Ethanol-assisted I | 30,000 | 937,500 | 100 | 450 | 60.5 | 1 | 423 | 635 | [70] |

| Ru/Na2SiO3 | 3.5 | 857,143 | 53.5 | 331 | 497 | ||||||

| Ru/Li2SiO3 | 3.4 | 882,353 | 31.2 | 203 | 304 | ||||||

| Ru/SiO2 | 3.6 | 833,333 | 17 | 108 | 162 | ||||||

| Ru/MgO | 3 | DP | 15,000 | 500,000 | 100 | 400 | 60 | 1 | 223 | 335 | [52] |

| CP 8 | 62 | 231 | 346 | ||||||||

| WI | 17 | 63 | 95 | ||||||||

| DP | 500 | 99 | 368 | 552 | |||||||

| CP | 99 | 368 | 552 | ||||||||

| WI | 90 | 335 | 502 | ||||||||

| Ru/SiC | 1 a | Rotovapor-assisted WI | 60,000 | 6,000,000 | 5 | 350 | 60 | 1 | 134 | 201 | [50] |

| 1 b | 6,000,000 | 40 | 89 | 134 | |||||||

| 2.5 a | 2,400,000 | 99 | 88 | 133 | |||||||

| 2.5 b | 2,400,000 | 80 | 71 | 107 | |||||||

| 4.4 a | 1,363,636 | 90 | 46 | 68 | |||||||

| 4.4 b | 1,363,636 | 90 | 46 | 68 | |||||||

| Ru/Y2O3 | 5 | KOH-assisted precipitation | 30,000 | 600,000 | 100 | 500 | 99 | 1 | 442 | 513 | [71] |

| 2 | 1,500,000 | 90 | 483 | 725 | |||||||

| Ru/SiO2 | 2 | 1,500,000 | 10 | 34 | 51 | ||||||

| Ru/CeO2 | 2 | WI | 13,800 | 690,000 | 44 | 450 | 99 | 1 | 223 | 335 | [64] |

| Ru/CeO2 | 1.6 | WI | 15,000 | 937,500 | 100 | 475 | 92 | 1 | 641 | 962 | [46] |

| 1.8 | 833,333 | 86 | 533 | 799 | |||||||

| Cs-Ru/MgO | 2.8 | PR 9 (EG) | 30,000 | 1,071,429 | 100 | 500 | 98 | 1 | 781 | 1171 | [63] |

| K-Ru/MgO | 2.8 | 96 | 765 | 1147 | |||||||

| Ru/CeO2 | 1 | PR (EG) | 22,000 | 2,200,000 | 100 | 450 | 99 | 1 | 1620 | 2429 | [57] |

| WI | 30 | 491 | 736 | ||||||||

| Ru/MgO | 1 | PR (EG) | 75 | 1227 | 1840 | ||||||

| Ru/Al2O3 | 1.1 | 30 | 426 | 669 | |||||||

| Ru-Cs/MgO-MIL101 | 3.1 | Organic solvent-assisted I | 15,000 | 483,871 | 100 | 400 | 98 | 1 | 353 | 529 | [45] |

| Ru-Cs/MIL | 3 | 500,000 | 78 | 290 | 435 | ||||||

| Ru/MgO-MIL | 6.3 | 238,095 | 58 | 103 | 154 | ||||||

| Ru@MIL-101 | 3.4 | 441,176 | 56 | 184 | 276 | ||||||

| Ru/CNTs | 7 | WI | 5200 | 74,286 | 100 | 450 | 50 | 1 | 28 | 41 | [72] |

| Ru/AX–21 | 30 | 17 | 25 |

3.5.3. Fe-Based Catalysts

3.5.4. Mo-Based Catalysts

3.6. Structured Catalysts

4. Kinetic Models

5. Reactors

5.1. Packed–Bed Reactors (PBR)

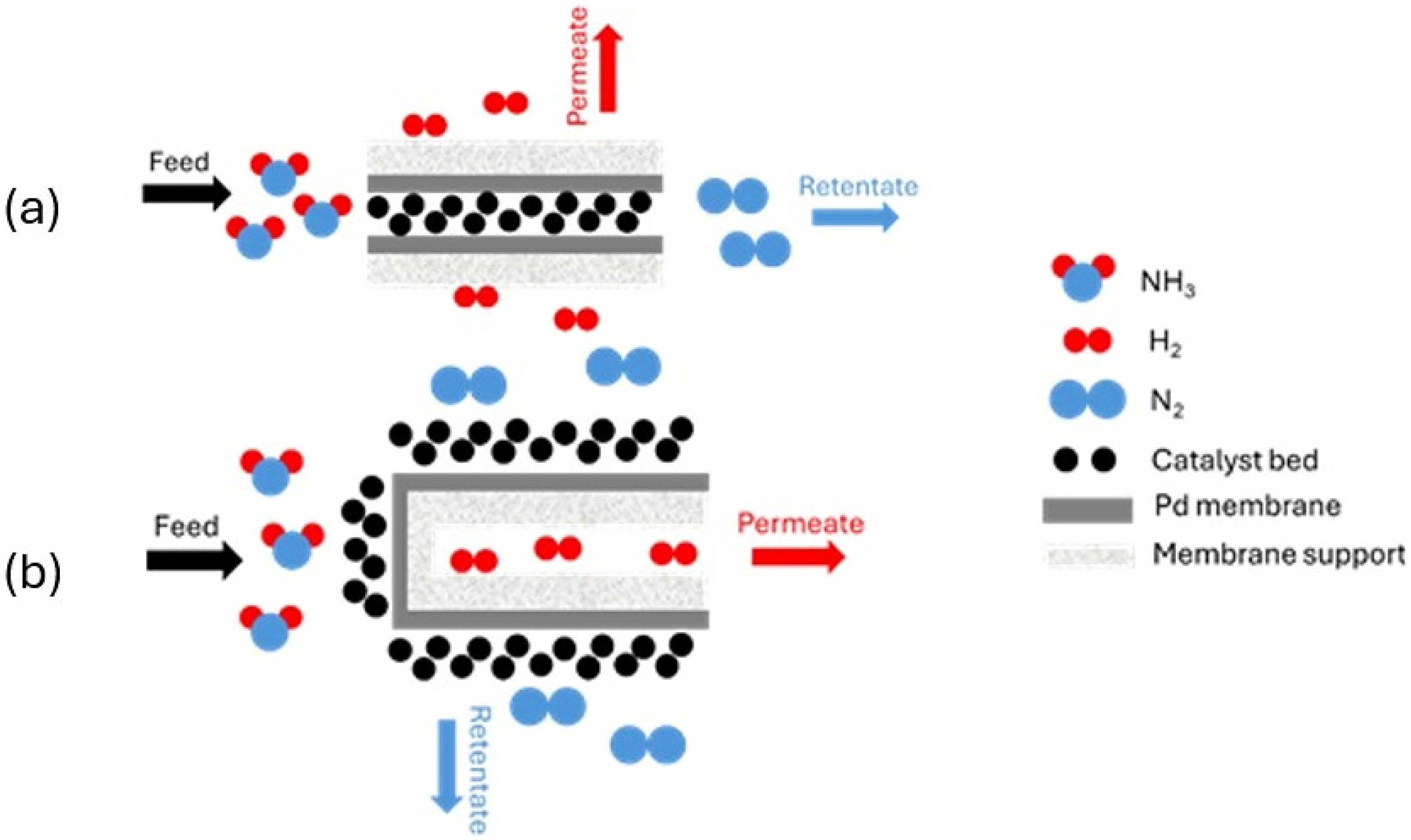

5.2. Packed–Bed Membrane Reactors (PBMR)

- Internal: The membrane is deposited internally, and the catalyst is positioned within the support. The gas to be separated flows from inside to outside (Figure 5a).

- External: The membrane is deposited externally to the support. The catalyst is positioned externally, and the gas to be separated flows from outside to inside (Figure 5b).

- Pressure differences, i.e., a disparity in total or partial pressure across the membrane;

- Concentration differences, when the hydrogen concentration varies significantly between the two sides;

- Electrical or ionic gradients, relevant in membranes where ionic transport is involved.

- Sweep Gas Introduction: An inert gas (e.g., argon or nitrogen) or water vapor is introduced on the permeate side to dilute hydrogen and reduce its partial pressure. While effective, this method introduces an additional separation step downstream, partially offsetting the advantages of membrane integration [100].

- Vacuum Pumping: Applying a vacuum on the permeate side efficiently lowers the hydrogen partial pressure without introducing contaminants. This approach is particularly suitable for industrial applications, offering high hydrogen purity and simplifying downstream processing [101].

- HRF based on the produced hydrogen. Used by Cerrillo et al. [11], this definition considers only the amount of hydrogen generated during the reaction.

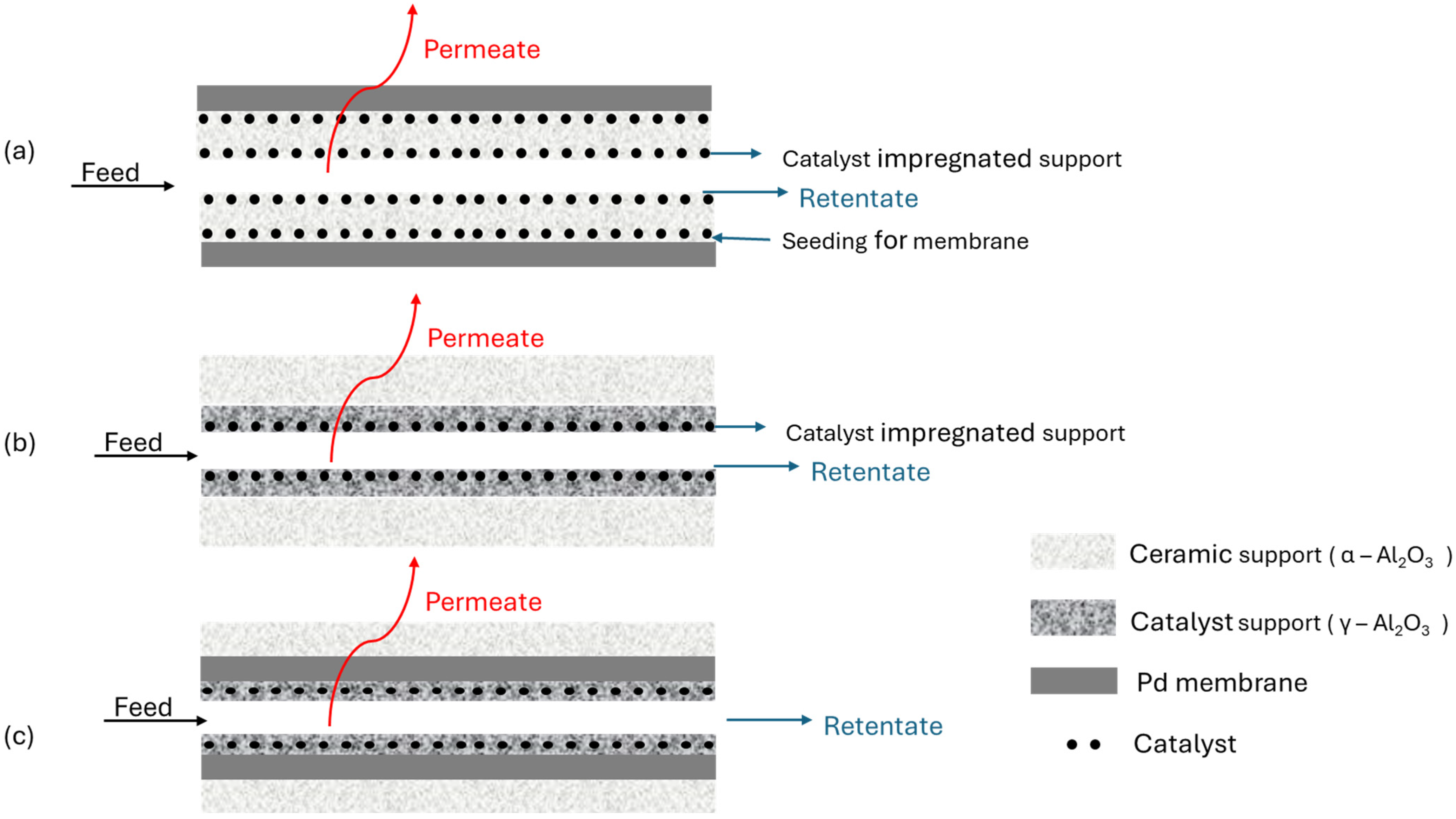

5.3. Catalytic Membrane Reactors (CMR)

| Reactor Type | PBMR | PBMR-CMR | CMR | PBMR | CMR | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

| Catalyst | Ba-CoCe | Ru/AC | Ru/(La)Al2O3 | Ru/γAl2O3 | Ru/α-Al2O3 + Pd/0.45% Ru/YSZ | Pd/Ru/YSZ | Ru/γ-Al2O3/αAl2O3/SiO2-ZrO2 | 3%Ru/1%Y/12%K/Al2O3 | Ru/SiO2 | Ru/γAl2O3 | ||||||

| Cat. Preparation 1 | CP | IW | - | Com. | IW | UI | WI | WI | WI + NaBH4 | |||||||

| Act. Metal (wt. %) | 41.7 | 2 | 0.65 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.45 | 3 | 4.1 | 2 | ||||||

| 100% | 10% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 50% | 100% | ||||||||

|

WHSVNH3 () | 600 | 3000 | 2000 | 1200 | 8520 | 120 | 360 | 1071 | - | - | 600 | 4000 | 600 | - | ||

|

WHSVNH3, () | - | - | 100,000 | 184,615 | 426,000 | 6000 | 720 | 214,286 | 234,267 | - | - | 20,000 | 133,333 | 14,634 | 682 | |

| Membrane Comp 2 | Pd-Au | Pd | Pd/Pd | Pd-Ag | Pd | Pd | Ru/Pd | SiO2-ZrO2 | MFI | Pd-Ag | CMS | Pd | Pd | |||

| Membrane Support 3 | PSS | PSS | Ta | IYA | AYSZ | YSZ | YSZ | YSZ | αAl2O3 | HF | - | - | - | αAl2O3 | ||

| Membrane (μm) | 8 | 40 | 1.5 | 4.6 | 4.61 | 4.85 | 2.63 | 6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 8 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 200 | 2 | |

| Driving Force 4 | V | V | Ar | H2O, N2 | V | V | None | NH3 | None | V | V | None | V | V | ||

| Sweep gas conf. 5 | - | - | CoC | CC | - | - | - | CoC | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| T (°C) | 485 | 485 | 370 | 425 | 472 | 400 | 520 | 400 | 400 | 450 | 500 | 450 | 450 | 375 | ||

| P (bar) | 4 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 1 | |||

| Conversion | 99% | 99% | 100% | 99% | 99% | 99% | 98% | 99% | 98% | 78% | 99% | 98.6 | 95.45 | 99.55 | 99 | 99 |

| HRF | 80% | - | 27% | 85% | 96.3% | 93.5% | 66% | 98% | 87.5% | 72% | - | 93.3 | 91.4 | 94.4 | 60 | - |

| PP H2 6 | 1.475 ** | - | 29.7 | 451.8 | 54.4 | 6.25 | 56.49 | 60 * | 189 * | - | - | 13.681 | 10.01 | 10.35 | 6.463 | - |

| Reactor conf. 7 | A | A | B | C | A | A | A | D | E | D | A | A | F | |||

| Ref | [11] | [58] | [110] | [109] | [120] | [121] | [90,116] | [114] | [115] | [112] | [10] | [118] | ||||

5.4. Micro–Reactors (μR)

5.5. Ion–Electron Conducting Membrane Reactors (IECMR) or Mixed Proton–Electron Conducting Membrane Reactors (MPECMR)

5.6. New Frontiers: Plasma Reactors and Photo-Electrocatalytic Systems

6. Economic Feasibility

- Heavy-duty trucks (on-board production);

- Hydrogen refueling stations;

- Ammonia import terminals (large-scale H2 generation).

7. Industrial Overview and Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Xiao, H.; Owen-Jones, M.; David, W.I.F.; Bowen, P.J. Ammonia for Power. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 69, 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Park, J.; Lee, H.; Byun, M.; Yoon, C.W.; Lim, H. Assessment of the Economic Potential: COx-Free Hydrogen Production from Renewables via Ammonia Decomposition for Small-Sized H2 Refueling Stations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.C.; Wang, W.W.; Si, R.; Ma, C.; Jia, C.J. Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Decomposition of NH3 Using Promoted MgO-Supported Ruthenium Catalysts. Sci. China Chem. 2019, 62, 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Dong, B.; Li, M.; Ji, Y.; Han, F. Comprehensive Life Cycle Cost Analysis of Ammonia-Based Hydrogen Transportation Scenarios for Offshore Wind Energy Utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 429, 139616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D. Ammonia Fired Gas Turbines: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Energy 2024, 290, 130275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.C.; Boundy, R.G. Transport Energy Data Book; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2022; ISBN 1800553684. [Google Scholar]

- Ajanovic, A.; Sayer, M.; Haas, R. The Economics and the Environmental Benignity of Different Colors of Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24136–24154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabeyoglu, A.; Evans, B. Conditioning System for Ammonia-Fired Power Plants. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual NH3 Fuel Association Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 1 October 2012; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, N.; Oshima, A.; Suga, E.; Sato, T. Kinetic Enhancement of Ammonia Decomposition as a Chemical Hydrogen Carrier in Palladium Membrane Reactor. Catal. Today 2014, 236, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrillo, J.L.; Morlanés, N.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Realpe, N.; Ramírez, A.; Katikaneni, S.P.; Paglieri, S.N.; Lee, K.; Harale, A.; Solami, B.; et al. High Purity, Self-Sustained, Pressurized Hydrogen Production from Ammonia in a Catalytic Membrane Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, K.; Chiang, P.H.; Jimenez, J.D.; Lauterbach, J.A. Material Discovery and High Throughput Exploration of Ru Based Catalysts for Low Temperature Ammonia Decomposition. Materials 2020, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.C.; Jiang, C.H.; Liu, F.J.; Cheng, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsueh, K.L. Preparation of Ru-Cs Catalyst and Its Application on Hydrogen Production by Ammonia Decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wu, S.; Ayvali, T.; Zheng, J.; Fellowes, J.; Ho, P.L.; Leung, K.C.; Large, A.; Held, G.; Kato, R.; et al. Dispersed Surface Ru Ensembles on MgO(111) for Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, F.R.; Guerrero-Ruiz, A.; Rodríguez-Ramos, I. Role of B5-Type Sites in Ru Catalysts Used for the NH3 Decomposition Reaction. Top. Catal. 2009, 52, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Li, K.; Sioud, S.; Cha, D.; Amad, M.H.; Hedhili, M.N.; Al-Talla, Z.A. Synthesis of Ru Nanoparticles Confined in Magnesium Oxide-Modified Mesoporous Alumina and Their Enhanced Catalytic Performance during Ammonia Decomposition. Catal. Commun. 2012, 26, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Devaguptapu, S.V.; Sviripa, A.; Lund, C.R.F.; Wu, G. Low-Temperature Ammonia Decomposition Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 226, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerke, A.; Christensen, C.H.; Nørskov, J.K.; Vegge, T. Ammonia for Hydrogen Storage: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Cao, T.; Sha, H.; Zhang, C.; Song, H.; Da, Z. Ammonia as Hydrogen Carrier: Advances in Ammonia Decomposition Catalysts for Promising Hydrogen Production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingreen, N.S. Ammonia Transport. EcoSal Plus 2004, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, D.; Giorgianni, G.; Italiano, C.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G.; Abate, S. Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition in Membrane and Packed Bed Reactors Using Diluted NH3 Streams. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Yan, J.; Song, W.; Ali, A.M.; Zhang, H. Advances in the Development of Ammonia Decomposition to CO -Free Hydrogen: Catalyst Materials and Activity Optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; He, W.; Guo, B.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H. A Comprehensive Review of Ammonia Decomposition for Hydrogen Production. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 13825–13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, A.S.; Ramli, R.M.; Hasnain, S.M.W.U.; Farooqi, A.S.; Sharaf Addin, A.H.; Abdullah, B.; Arslan, M.T.; Farooqi, S.A. A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition over Ni-Based Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Guan, J.; Liu, Y.; Shi, D.; Wu, Q.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Research Progress of Ruthenium-Based Catalysts for Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 1019–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Song, W.; Yan, J.; Qi, X.; Yang, J.; Wen, J.; Zhang, H. Ammonia Energy: Synthesis and Utilization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 8003–8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lei, K.; Mi, Y.; Fang, W. Recent Progress on Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition: Technical Roadmap and Catalytic Mechanism. Molecules 2023, 28, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Lee, J.; Jeong, H.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, B.S. Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition to Produce Hydrogen: A Mini-Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucentini, I.; Garcia, X.; Vendrell, X.; Llorca, J. Review of the Decomposition of Ammonia to Generate Hydrogen. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 18560–18611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, R.; Lu, R.; Leng, G.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, F.; Yu, Q. A Review on Numerical Simulation of Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition. Energies 2023, 16, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, D.; Bicer, Y. A Review of Hydrogen Production from Onboard Ammonia Decomposition: Maritime Applications of Concentrated Solar Energy and Boil-Off Gas Recovery. Fuel 2023, 352, 128900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojelade, O.A.; Zaman, S.F. Ammonia Decomposition for Hydrogen Production: A Thermodynamic Study. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacham, M.; Brauner, N. A Hundred Years of Chemical Equilibrium Calculations—The Case of Ammonia Synthesis. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 13, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.F.; Xu, B.Q.; Zhu, W.X.; Ng, C.F.; Zhou, X.P.; Au, C.T. Carbon Nanotubes-Supported Ru Catalyst for the Generation of CO x-Free Hydrogen from Ammonia. Catal. Today 2004, 93–95, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Padban, N.; Ye, Z.; Andersson, A.; Bjerle, I. Ammonia Decomposition in Hot Gas Cleaning. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 4175–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.-F.; Zhang, Q.-H.; Xu, B.-Q.; Zhu, W.-X.; Ng, C.-F.; Au, C.-T. Investigation on the Catalysis of COx-Free Hydrogen Generation from Ammonia. J. Catal. 2004, 224, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, F.; Toda, Y.; Kanie, Y.; Kitano, M.; Inoue, Y.; Yokoyama, T.; Hara, M.; Hosono, H. Ammonia Decomposition by Ruthenium Nanoparticles Loaded on Inorganic Electride C12A7:E-. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3124–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.E.; Torrente-Murciano, L. H2 Production via Ammonia Decomposition Using Non-Noble Metal Catalysts: A Review. Top. Catal. 2016, 59, 1438–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.; Muroyama, H.; Matsui, T.; Eguchi, K. Ammonia Decomposition over Nickel Catalysts Supported on Alkaline Earth Metal Aluminate for H2 Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 26979–26988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Karim, A.M.; Arya, A.; Vlachos, D.G. Assessment of Overall Rate Expressions and Multiscale, Microkinetic Model Uniqueness via Experimental Data Injection: Ammonia Decomposition on Ru/γ-Al 2O 3 for Hydrogen Production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 5255–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Li, W. NH3 Decomposition Kinetics on Supported Ru Clusters: Morphology and Particle Size Effect. Catal. Lett. 2007, 119, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, J.C.; Thomas, F.S.; Seebauer, E.G.; Masel, R.I. A Priori Catalytic Activity Correlations: The Difficult Case of Hydrogen Production from Ammonia. Catal. Lett. 2004, 96, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehenics, A. Bachelor Thesis Chemical Engineering Ammonia Decomposition over Ruthenium Catalysts. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, X.; Zhou, J.; Qian, G.; Li, P.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D. Carbon Nanofiber-Supported Ru Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution by Ammonia Decomposition. Cuihua Xuebao/Chinese J. Catal. 2010, 31, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Gong, Q.; Luo, J.; Lin, R.; Xin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Peng, Q.; et al. Sub-Nm Ruthenium Cluster as an Efficient and Robust Catalyst for Decomposition and Synthesis of Ammonia: Break the “Size Shackles”. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 4774–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, S.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Z. Cerium Oxide-Based Catalyst for Low-Temperature and Efficient Ammonia Decomposition for Hydrogen Production Research. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 68, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, R.L.; Aspera, S.M.; Sison Escaño, M.C.; Nakanishi, H.; Kasai, H. First Principles Study of Methane Decomposition on B5 Step-Edge Type Site of Ru Surface. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 184001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.M.; Prasad, V.; Mpourmpakis, G.; Lonergan, W.W.; Frenkel, A.I.; Chen, J.G.; Vlachos, D.G. Correlating Particle Size and Shape of Supported Ru/γ-Al 2 O 3 Catalysts with NH 3 Decomposition Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12230–12239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, K.C.; Hong, S.; Li, G.; Xing, Y.; Ng, B.K.Y.; Ho, P.-L.; Ye, D.; Zhao, P.; Tan, E.; Safonova, O.; et al. Confined Ru Sites in a 13X Zeolite for Ultrahigh H 2 Production from NH 3 Decomposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 14548–14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzón, M.; Romero, A.; de Lucas Consuegra, A.; de la Osa, A.R.; Sánchez, P. Hydrogen Production by Ammonia Decomposition over Ruthenium Supported on SiC Catalyst. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 94, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganley, J.C.; Seebauer, E.G.; Masel, R.I. Development of a Microreactor for the Production of Hydrogen from Ammonia. J. Power Sources 2004, 137, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, T.; Nakamura, I.; Hashiguchi, Y.; Kanazawa, S.; Takahashi, A. Effect of Catalyst Preparation Method on Ammonia Decomposition Reaction over Ru/MgO Catalyst. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 93, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, K.; Ren, H.; Zhou, C.; Luo, Y.; Lin, L.; Au, C.; Jiang, L. Ru-Based Catalysts for Ammonia Decomposition: A Mini-Review. Energy and Fuels 2021, 35, 11693–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, L.; Divins, N.J.; Vendrell, X.; Serrano, I.; Llorca, J. Hydrogen Production in Microreactors. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128173848. [Google Scholar]

- Verdoliva, V.; Saviano, M.; De Luca, S. Zeolites as Acid/Basic Solid Catalysts: Recent Synthetic Developments. Catalysts 2019, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G. Acidity and Basicity in Zeolites: A Fundamental Approach. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 254, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.C.; Fu, X.P.; Wang, W.W.; Wang, X.; Wu, K.; Si, R.; Ma, C.; Jia, C.J.; Yan, C.H. Ceria-Supported Ruthenium Clusters Transforming from Isolated Single Atoms for Hydrogen Production via Decomposition of Ammonia. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 268, 118424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, F.R.; Ma, Y.H.; Rodríguez-Ramos, I.; Guerrero-Ruiz, A. High Purity Hydrogen Production by Low Temperature Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition in a Multifunctional Membrane Reactor. Catal. Commun. 2008, 9, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.B.; Kim, H.Y.; Jeon, M.; Lee, D.H.; Park, H.S.; Choi, S.H.; Nam, S.W.; Jang, S.C.; Park, J.H.; Lee, K.Y.; et al. Enhanced Ammonia Dehydrogenation over Ru/La(x)-Al2O3 (x = 0–50 Mol%): Structural and Electronic Effects of La Doping. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aika, K.; Ohya, A.; Ozaki, A.; Inoue, Y.; Yasumori, I. Support and Promoter Effect of Ruthenium Catalyst. II. Ruthenium/Alkaline Earth Catalyst for Activation of Dinitrogen. J. Catal. 1985, 92, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas, S.; Morlanés, N.; Katikaneni, S.P.; Harale, A.; Solami, B.; Gascon, J. High pressure ammonia decomposition on Ru–K/CaO catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 5027–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Shen, X.; Cai, Z. ScienceDirect Ruthenium Catalyst Supported on Ba Modified ZrO 2 for Ammonia Decomposition to CO x -Free Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7300–7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Ge, Q.; Li, W. Highly Efficient Ru/MgO Catalysts for NH3 Decomposition: Synthesis, Characterization and Promoter Effect. Catal. Commun. 2006, 7, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucentini, I.; Casanovas, A.; Llorca, J. Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition for Hydrogen Production on Ni, Ru and Ni[Sbnd]Ru Supported on CeO2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 12693–12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, A.; Vecchione, L.; Del Prete, Z. Ammonia Decomposition over Commercial Ru/Al2O3 Catalyst: An Experimental Evaluation at Different Operative Pressures and Temperatures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.Y.; Im, H.B.; Song, D.; Jung, U. Ammonia Decomposition over Ru-Coated Metal-Structured Catalysts for COx-Free Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Wu, K.; Zhou, C.; Yao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, L.; Jiang, L. Electronic Metal-Support Interaction Enhanced Ammonia Decomposition Efficiency of Perovskite Oxide Supported Ruthenium. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 257, 117719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Liu, L.; Yu, P.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; He, T.; Wu, G.; Chen, P. Mesoporous Ru/MgO Prepared by a Deposition-Precipitation Method as Highly Active Catalyst for Producing COx-Free Hydrogen from Ammonia Decomposition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 211, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Feng, J.; He, T.; Chen, P. Highly Efficient Ru/MgO Catalyst with Surface-Enriched Basic Sites for Production of Hydrogen from Ammonia Decomposition. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiqiang, F.; Ziqing, W.; Dexing, L.; Jianxin, L.; Lingzhi, Y.; Qin, W.; Zhong, W. Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition to CO x -Free Hydrogen over Ruthenium Catalyst Supported on Alkali Silicates. Fuel 2022, 326, 125094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Liu, L.; Ju, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; He, T.; Chen, P. Highly Dispersed Ruthenium Nanoparticles on Y2O3 as Superior Catalyst for Ammonia Decomposition. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.B. Kinetics of Ammonia Synthesis and Decomposition on Heterogeneous Catalysts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Torrente-Murciano, L.; Hill, A.K.; Bell, T.E. Ammonia Decomposition over Cobalt/Carbon Catalysts—Effect of Carbon Support and Electron Donating Promoter on Activity. Catal. Today 2017, 286, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlanés, N.; Sayas, S.; Shterk, G.; Katikaneni, S.P.; Harale, A.; Solami, B.; Gascon, J. Development of a Ba-CoCe Catalyst for the Efficient and Stable Decomposition of Ammonia. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 3014–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.Z.; Gu, Y.Q.; He, X.X.; Wei, S.; Jin, Z.; Jia, C.J.; Song, Q.S. Iron-Based Composite Nanostructure Catalysts Used to Produce COx-Free Hydrogen from Ammonia. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chu, W.; Ding, C.; Xi, X.; Jiang, R.; Yan, J. Embedded MoN@C Nanocomposites as an Advanced Catalyst for Ammonia Decomposition to COx-Free Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30630–30638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podila, S.; Zaman, S.F.; Driss, H.; Al-Zahrani, A.A.; Daous, M.A.; Petrov, L.A. High Performance of Bulk Mo2N and Co3Mo3N Catalysts for Hydrogen Production from Ammonia: Role of Citric Acid to Mo Molar Ratio in Preparation of High Surface Area Nitride Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 8006–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dou, B.; Bin, F. Enhancing Ammonia Decomposition for Hydrogen Production via Optimization of Interface Effects and Acidic Site in Supported Cobalt-Nickel Alloy Catalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 360, 131144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wen, K.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.; Johannessen, B.; Zhang, S. High-Entropy Alloys in Catalysis: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W. Recent Progress in High-Entropy Alloys. Ann. Chim. Sci. des Mater. 2006, 31, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Yao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Wang, G.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Hu, L.; Wang, C. Highly Efficient Decomposition of Ammonia Using High-Entropy Alloy Catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, W.M.; Lednor, P.W. Monolithic Ceramics and Heterogeneous Catalysts: Honeycombs and Foams. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1996, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, A.; Moulijn, J.A. Catalysis Reviews: Science and Engineering Monoliths in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Catal. Rev. 2015, 36, 179–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, S.; Friedrich, H.B. Monoliths: A Review of the Basics, Preparation Methods and Their Relevance to Oxidation. Catalysts 2017, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašić, V.; Jović, F. State-of-the-Art in the Monolithic Catalysts/Reactors. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2006, 311, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranshahi, D.; Golrokh, A.; Pourazadi, E.; Saeidi, S.; Gallucci, F. Progress in Spherical Packed-Bed Reactors: Opportunities for Refineries and Chemical Industries. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2018, 132, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V. Optimal Design and Operation of Ammonia Decomposition Reactors. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 5360–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, S.; Cha, J.Y.; Shin, B.J.; Mun, J.H.; Yoon, H.C.; Mazari, S.A.; Moon, J.H. Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of Hydrogen Production through Ammonia Decomposition. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.P.; Way, J.D. Catalytic Decomposition of Ammonia in a Membrane Reactor. J. Memb. Sci. 1994, 96, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitar, R.; Shah, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wikoff, H.; Way, J.D.; Wolden, C.A. Compact Ammonia Reforming at Low Temperature Using Catalytic Membrane Reactors. J. Memb. Sci. 2022, 644, 120147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, F.; Fernandez, E.; Corengia, P.; van Sint Annaland, M. Recent Advances on Membranes and Membrane Reactors for Hydrogen Production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 92, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcida, M.F.; Curto, D.; Martín, M. Design and Optimization of CO2 Hydrogenation Multibed Reactors. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 181, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A.; Conte, F.; Rossetti, I. Process Intensification for Ammonia Synthesis in Multibed Reactors with Fe-Wustite and Ru/C Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abashar, M.E.E. Multi-Stage Membrane Reactors for Hydrogen Production by Ammonia Decomposition. Int. J. Petrochemistry Res. 2018, 2, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, B.; Deng, Z.; Han, P.; Yan, N.; Pan, Z.; Chan, S.H. The Modelling of a Multi-Tubular Packed-Bed Reactor for Ammonia Cracking and SOFC Waste Heat Utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 504, 159062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arratibel Plazaola, A.; Pacheco Tanaka, D.A.; Van Sint Annaland, M.; Gallucci, F. Recent Advances in Pd-Based Membranes for Membrane Reactors. Molecules 2017, 22, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, M.; Capocelli, M.; Giannattasio, A. Membrane Reactor for One-Step DME Synthesis Process: Industrial Plant Simulation and Optimization. J. CO2 Util. 2017, 22, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, S.; Liu, S.; Serra, J.M.; Basile, A.; Diniz da Costa, J.C. Perovskite Membrane Reactors: Fundamentals and Applications for Oxygen Production, Syngas Production and Hydrogen Processing. In Membranes for Clean and Renewable Power Applications; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Sawston, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780857095459. [Google Scholar]

- Naquash, A.; Qyyum, M.A.; Chaniago, Y.D.; Riaz, A.; Yehia, F.; Lim, H.; Lee, M. Separation and Purification of Syngas-Derived Hydrogen: A Comparative Evaluation of Membrane- and Cryogenic-Assisted Approaches. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, M.; Hayakawa, R.; Makino, Y.; Oumi, Y.; Uemiya, S.; Asanuma, M. CO2 Methanation Combined with NH3 Decomposition by in Situ H2 Separation Using a Pd Membrane Reactor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 10154–10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongis, M.; Di Marcoberardino, G.; Baiguini, M.; Gallucci, F.; Binotti, M. Optimization of Small-Scale Hydrogen Production with Membrane Reactors. Membranes 2023, 13, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiuta, S.; Everson, R.C.; Neomagus, H.W.J.P.; Van Der Gryp, P.; Bessarabov, D.G. Reactor Technology Options for Distributed Hydrogen Generation via Ammonia Decomposition: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 14968–14991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Barreiro, M.M.; Maroño, M. Hydrogen Enrichment and Separation from Synthesis Gas by the Use of a Membrane Reactor. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, S132–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Xiong, G. Efficient Production of Hydrogen from Natural Gas Steam Reforming in Palladium Membrane Reactor. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 81, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, T.; Perera, S.P.; Thomas, W.J. An Experimental and Theoretical Investigation of a Catalytic Membrane Reactor for the Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Methanol. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2001, 56, 2047–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkary, H.; Farsi, M.; Rahimpour, M.R. Supporting the Propane Dehydrogenation Reactors by Hydrogen Permselective Membrane Modules to Produce Ultra-Pure Hydrogen and Increasing Propane Conversion: Process Modeling and Optimization. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7364–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmeyer, R.; Höllein, V.; Daub, K. Membrane Reactors for Hydrogenation and Dehydrogenation Processes Based on Supported Palladium. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2001, 173, 135–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgianni, G.; Cozza, D.; Dalena, F.; Giglio, E.; Abate, S. Direct Synthesis of H2O2 on Pd/Al2O3 Contactors: Understanding the Effect of Pd Particle Size and Calcination through Kinetic Analysis. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 84, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Lee, E.H.; Byun, S.; Seo, D.W.; Hwang, H.J.; Yoon, H.C.; Kim, H.; Ryi, S.K. Highly Selective Pd Composite Membrane on Porous Metal Support for High-Purity Hydrogen Production through Effective Ammonia Decomposition. Energy 2022, 260, 125209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Cha, J.; Oh, H.T.; Lee, T.; Lee, S.H.; Park, M.G.; Jeong, H.; Kim, Y.; Sohn, H.; Nam, S.W.; et al. A Catalytic Composite Membrane Reactor System for Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Using Steam as a Sweep Gas. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 614, 118483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryi, S.K.; Xu, N.; Li, A.; Lim, C.J.; Grace, J.R. Electroless Pd Membrane Deposition on Alumina Modified Porous Hastelloy Substrate with EDTA-Free Bath. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 2328–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Dong, Q.; McCullough, K.; Lauterbach, J.; Li, S.; Yu, M. Novel Hollow Fiber Membrane Reactor for High Purity H2 Generation from Thermal Catalytic NH3 Decomposition. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 629, 119281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, S.; Barbera, K.; Centi, G.; Giorgianni, G.; Perathoner, S. Role of Size and Pretreatment of Pd Particles on Their Behaviour in the Direct Synthesis of H2O2. J. Energy Chem. 2016, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liguori, S.; Fuerst, T.F.; Way, J.D.; Wolden, C.A. Efficient Ammonia Decomposition in a Catalytic Membrane Reactor To Enable Hydrogen Storage and Utilization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5975–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kanezashi, M.; Lee, H.R.; Maeda, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Tsuru, T. Preparation of a Novel Bimodal Catalytic Membrane Reactor and Its Application to Ammonia Decomposition for CO X-Free Hydrogen Production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 12105–12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitar, R.; Shah, J.; Way, J.D.; Wolden, C.A. Efficient Generation of H2/NH3Fuel Mixtures for Clean Combustion. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 9357–9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Kim, S.S.; Li, A.; Grace, J.R.; Lim, C.J.; Boyd, T. Novel Electroless Plating of Ruthenium for Fabrication of Palladium-Ruthenium Composite Membrane on PSS Substrate and Its Characterization. J. Membr. Sci. Res. 2015, 1, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Kikuchi, Y.; Furusawa, T.; Sato, T. Tube-Wall Catalytic Membrane Reactor for Hydrogen Production by Low-Temperature Ammonia Decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 20257–20265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, S.K.; Keeling, M.K.; Davidson, A.P.; Hatlevik, O.; Way, J.D. Palladium-Ruthenium Membranes for Hydrogen Separation Fabricated by Electroless Co-Deposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 6484–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechetto, V.; Di Felice, L.; Medrano, J.A.; Makhloufi, C.; Zuniga, J.; Gallucci, F. H2 Production via Ammonia Decomposition in a Catalytic Membrane Reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 216, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, S.T.B.; Law, J.O.; Patki, N.S.; Wolden, C.A.; Way, J.D. Glass Frit Sealing Method for Macroscopic Defects in Pd-Based Composite Membranes with Application in Catalytic Membrane Reactors. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 172, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kockmann, N. Pressure Loss and Transfer Rates in Microstructured Devices with Chemical Reactions. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2008, 31, 1188–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdlovu, N.V.; Lin, K.S.; Yeh, H.P.; François, M.; Hussain, A.; Badshah, S.M. Autothermal Reforming of Methanol in a Microreactor Using Porous Alumina Supported CuO/ZnO with CeO2 Sol Catalysts Washcoat. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 119, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Song, W.; Xu, D. Compact Steam-Methane Reforming for the Production of Hydrogen in Continuous Flow Microreactor Systems. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15600–15614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostad, H.B.; Riis, T.U.; Ellestad, O.H. Catalytic Cracking of Naphthenes and Naphtheno-Aromatics in Fixed Bed Micro Reactors. Appl. Catal. 1990, 63, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimu, A.; Jaenicke, S.; Alhooshani, K. Heterogeneous Catalysis in Continuous Flow Microreactors: A Review of Methods and Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 327, 792–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.R.; Mhadeshwar, A.B.; Vlachos, D.G. Microreactor Modeling for Hydrogen Production from Ammonia Decomposition on Ruthenium. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2004, 43, 2986–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Fulton, M.; Bertola, V. Kinetic Assessment of H2 Production from NH3 Decomposition over CoCeAlO Catalyst in a Microreactor: Experiments and CFD Modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 411, 128595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Caravella, A. Pd-Based Membranes: Overview and Perspectives. Membranes 2019, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Nott, J.; Prinke, J.; Goodrich, S.; Massicotte, F.; Rebeiz, K.; Nesbit, S.; Flanagan, T.B.; Craft, A. Evidence for Hydrogen-Assisted Recovery of Cold-Worked Palladium: Hydrogen Solubility and Mechanical Properties Studies. AIMS Energy 2017, 5, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, M.R.; Samimi, F.; Babapoor, A.; Tohidian, T.; Mohebi, S. Palladium Membranes Applications in Reaction Systems for Hydrogen Separation and Purification: A Review. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2017, 121, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, S.S.; Somalu, M.R.; Loh, K.S.; Liu, S.; Zhou, W.; Sunarso, J. Perovskite-Based Proton Conducting Membranes for Hydrogen Separation: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 15281–15305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Agarwal, M. Advances in Materials Process and Separation Mechanism of the Membrane towards Hydrogen Separation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 27062–27087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Meng, B.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Meng, X.; Sunarso, J.; Tan, X.; Liu, S. Single-Step Synthesized Dual-Layer Hollow Fiber Membrane Reactor for on-Site Hydrogen Production through Ammonia Decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7423–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, C.; Zhu, S.; Yu, F.; Dai, B.; Yang, D. A Review of Recent Advances of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma in Catalysis. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Sun, S.; Guo, H. Plasma-Assisted Ammonia Decomposition over Fe–Ni Alloy Catalysts for COx-Free Hydrogen. AIChE J. 2019, 65, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, G.; Zhang, H.; Liao, C.; Yang, C.; Zhao, F.; Lei, G.; Zheng, G.; Mao, X.; Zhang, K. Plasma-Promoted Ammonia Decomposition over Supported Ruthenium Catalysts for COx-Free H2 Production. ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202202370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryjak, M.; Gancarz, I.; Smolinska, K. Plasma Nanostructuring of Porous Polymer Membranes. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 161, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampelli, C.; Tavella, F.; Giusi, D.; Ronsisvalle, A.M.; Perathoner, S.; Centi, G. Electrode and Cell Design for CO2 Reduction: A Viewpoint. Catal. Today 2023, 421, 114217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Electrocatalysis: Prospects and Role to Enable an E-Chemistry Future. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202400259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tan, K.C.; Guo, J.; He, T.; Chen, P. Hydrogen Production via Photocatalytic Ammonia Decomposition. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 9076–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Duan, X.; Zou, P.; Jeerh, G.; Sun, B.; Chen, S.; Humphreys, J.; Walker, M.; Xie, K.; et al. An Efficient Symmetric Electrolyzer Based On Bifunctional Perovskite Catalyst for Ammonia Electrolysis. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, A.; Okemoto, A.; Nishino, Y.; Kitagawa, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Taniya, K.; Ichihashi, Y.; Nishiyama, S. Mechanistic Study of Reaction Mechanism on Ammonia Photodecomposition over Ni/TiO2 Photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 206, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Aziz, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of Hydrogen Transportation Infrastructure Using Ammonia and Methanol. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 15737–15747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, T.; Rogers, M. Low Pressure Storage of Natural Gas for Vehicular Applications. SAE Tech. Pap. 2000, 1, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulky, L.; Srivastava, S.; Lakshmi, T.; Sandadi, E.R.; Gour, S.; Thomas, N.A.; Shanmuga Priya, S.; Sudhakar, K. An Overview of Hydrogen Storage Technologies—Key Challenges and Opportunities. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 325, 129710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, R.; Affonso Nóbrega, P.H.; Achard, P.; Beauger, C. Economical Assessment Comparison for Hydrogen Reconversion from Ammonia Using Thermal Decomposition and Electrolysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 188, 113784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Su, J.; Breunig, H. Benchmarking Plasma and Electrolysis Decomposition Technologies for Ammonia to Power Generation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 288, 117166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadou, E.S.; Heracleous, E.; Vasalos, I.A.; Lemonidou, A.A. Ru-Based Catalysts for Glycerol Hydrogenolysis-Effect of Support and Metal Precursor. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 92, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michałek, T.; Hessel, V.; Wojnicki, M. Production, Recycling and Economy of Palladium: A Critical Review. Materials 2024, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metal | % d-Character | Metal | % d-Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ru | 50 | Cr | 39 |

| Ni | 40 | Pd | 46 |

| Rh | 50 | Cu | 36 |

| Co | 39.5 | Te | 0 |

| Ir | 49 | Se | 0 |

| Fe | 39.7 | Pb | 0 |

| Pt | 44 |

| Catalyst | Metals (%) | Cat. Prep. | WHSV (NmLNH3 gCat−1 h−1) | WHSV (NmLNH3 gMe−1 h−1) | NH3 (%) | T(°C) | Conv (%) | P (bar) | Productivity (mmolNH3 gRu−1min−1) | H2 Production (mmolH2 gRu−1 min−1) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/Ba–Al–O | 20 | I 1 | 6000 | 30,000 | 100 | 550 | 90.3 | 1 | 20 | 30 | [39] |

| Ni/Sr–Al–O | 78.8 | 18 | 26 | ||||||||

| Ni/Ca–Al–O | 62.2 | 14 | 21 | ||||||||

| Ni/Mg–Al–O | 38.8 | 9 | 13 | ||||||||

| Ni/CeO2 | 10 | WI 2 | 13,800 | 138,000 | 44 | 450 | 62 | 1 | 28 | 42 | [64] |

| Ni/Al2O3 | 30 | 14 | 20 | ||||||||

| Co/AX–21 | 7 | WI | 5200 | 74,286 | 100 | 450 | 25 | 1 | 14 | 21 | [73] |

| Co/CNT | 10 | 6 | 8 | ||||||||

| Co-Cs/AX–21 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| CoCe | 41.7 | CP 3 | 9000 | 21,583 | 100 | 450 | 65 | 1 | 10 | 16 | [74] |

| 30.2 | 29,801 | 45 | 10 | 15 | |||||||

| 17.9 | 50,279 | 30 | 11 | 17 | |||||||

| 0.5% Ba–CoCe | 41.7 | 21,583 | 80 | 13 | 19 | ||||||

| 1% Ba–CoCe | 21,583 | 30 | 5 | 7 | |||||||

| MoN@C | 25.9 | HT 4 | 15,000 | 57,915 | 100 | 625 | 100 | 1 | 52 | 79 | [76] |

| Mo@C | 21 | 71,429 | 90 | 58 | 87 | ||||||

| MoN | 94.6 | AC 5 | 6000 | 6383 | 100 | 550 | 87 | 1 | 4 | 6 | [77] |

| 3% Co MoN | 83 | AC | 7229 | 87 | 5 | 8 | |||||

| Fe3O4 | 72 * | ST 6 | 24,000 | 33,333 | 100 | 600 | 45 | 1 | 11 | 17 | [75] |

| Fe3O4@TiO2 | ST | 80 | 20 | 30 | |||||||

| Fe3O4@CeO2 | K-C C 7 | 88 | 22 | 33 |

| Catalyst | Load (%) | Eapp (kJ mol−1) | T (°C) | K0,app | α | β | γ | RDS | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru/Al2O3 | 8.5 | 117 | 1.5 × 10−9 mol m−3 s−1 | - | 0.27 | - | N2 Desorb | [65] | |

| Ru/C12A7: e− | 2.2 | 22.1 | 600 | - | 0.9 | - | 0.04 | N2 Desorb | [37] |

| Ru/C12A7:O2− | 2 | 24.6 | - | 0.4 | - | 0.14 | |||

| Ru-K/C | 2.7 | 41.8 | 0.58 | - | 0.15 | ||||

| Ru-10%K/CaO | 3 | 111 | 350 | 8584.8 mol gcat−1s−1 | 0.5 | - | −1.2 | N2 Desorb/N–H cleavage | [61] |

| Ni/Ba–Al–O | 20 | 76.5 | 450 | - | 0.47 | - | −0.32 | H2 Desorb | [39] |

| Ni/Sr–Al–O | 81.1 | - | 0.58 | - | −0.38 | ||||

| Ni/Ca–Al–O | 87.2 | - | 0.70 | - | −0.42 | ||||

| Ni/Mg–Al–O | 89.3 | - | 0.39 | - | −0.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maccarrone, D.; Italiano, C.; Giorgianni, G.; Centi, G.; Perathoner, S.; Vita, A.; Abate, S. A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition. Catalysts 2025, 15, 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15090811

Maccarrone D, Italiano C, Giorgianni G, Centi G, Perathoner S, Vita A, Abate S. A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition. Catalysts. 2025; 15(9):811. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15090811

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaccarrone, Domenico, Cristina Italiano, Gianfranco Giorgianni, Gabriele Centi, Siglinda Perathoner, Antonio Vita, and Salvatore Abate. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition" Catalysts 15, no. 9: 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15090811

APA StyleMaccarrone, D., Italiano, C., Giorgianni, G., Centi, G., Perathoner, S., Vita, A., & Abate, S. (2025). A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production via Catalytic Ammonia Decomposition. Catalysts, 15(9), 811. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15090811