1. Introduction

Worldwide, in 2023, there were approximately 900 million olive trees covering a total area of 10 million hectares [

1]. The world’s olive oil production is mainly concentrated in Europe, with the Iberian Peninsula being a leader region—olive oil production in this region is estimated to reach 1485 tons in the 2024/25 crop year (there is no full report on this campaign yet) [

1]. In this way, the olive oil industry is economically very important for Mediterranean countries; however, it is observed that all these producing countries are considerably affected by the high pollution resulting from the production of olive oil. The process generates large amounts of solid and liquid waste (the last one, called olive oil mill wastewater—OMW), raising serious disposal problems for the producers. This occurs because of the high values of the chemical oxygen demand (COD—60–185 g·L

−1) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD—14–75 g·L

−1) present in the OMW [

2]—these wide ranges are explained by the different compositions that OMW can present, which depend on many factors, like the olive species itself, the land, the local clime and the olive oil production process. Actually, the pollution from this stream was estimated to cause approximately 200 times more impact than that from urban wastewater due to its specific chemical composition [

3]. The composition of OMW is highly variable and suggests that several substances can be present, depending on several factors (e.g., the surface of cultivation and the age of the olive tree) [

4]. In general, the OMW effluent is composed of water (80–95 wt.% [

2,

5,

6,

7]), sugars (up to 20–30 g·L

−1), polyphenols (up to 8 g·L

−1) and fatty acids (5–10 g·L

−1) [

2]. In this way, the uncontrolled disposal of OMW represents a social, economic, and environmental problem, which must be addressed.

In recent decades, several processes have been explored to reduce the OMW pollutant load. From this perspective, the possibility of waste treatment and valorization has been considered, namely through the steam reforming reaction process of the OMW (OMWSR) [

8,

9,

10]. This process would eliminate the pollutant load present in the effluent while simultaneously producing H

2. The OMWSR reaction (Equation (1)) consists of the sum of two independent reactions: the thermal decomposition of high-molecular-weight molecules in the presence of steam (Equation (2)) and the water–gas shift (WGS–Equation (3)) reaction. The reaction enthalpy for each equation was taken from a previous work [

11] and depends on the OMW composition.

| | (kJ·mol−1) | |

| Varies | (1) |

| Varies | (2) |

| −41 | (3) |

This process can have side reactions, namely the following: Equation (4)—carbon monoxide methanation, Equation (5)—dry steam reforming of methane, Equation (6)—steam reforming of methane, and Equation (7)—cracking of the oxygenated molecules. Among the proposed reactions, Equations (4) and (7) are the most probable, as confirmed in previous studies [

8,

10].

| | (kJ·mol−1) | |

| −206 | (4) |

| 247 | (5) |

| 165 | (6) |

| Varies | (7) |

Also, the formation of coke very often occurs in steam reforming processes (leading to pore blockage and active site coverage, thereby reducing the catalyst performance and accelerating its deactivation), particularly through the following reactions: Equation (7)—cracking of the oxygenated molecules, Equation (8)—cracking of hydrocarbons, Equation (9)—Boudouard reaction, Equation (10)—methane cracking, Equation (11)—carbon monoxide reduction, and Equation (12)—carbon dioxide reduction.

| | (kJ·mol−1) | |

| Varies | (8) |

| −172 | (9) |

| 74 | (10) |

| −131 | (11) |

| −90 | (12) |

Compared to conventional steam reforming feedstocks like ethanol or glycerol [

12,

13], OMW not only represents a low-cost and sustainable feedstock but also offers higher hydrogen yield potential per oxygenated molecule due to its rich and diverse organic composition.

The only authors who experimentally studied the OMWSR reaction were Tosti et al. [

2,

3,

14], Casanovas et al. [

15] and Alique et al. [

16], apart from Rocha et al. [

8,

9,

10]. Tosti et al. used a commercial Pt-based catalyst [

2] and developed new noble-metal-based catalysts (with Pd, Rh and Pt supported on Al

2O

3 coated with CeO

2–ZrO

2) to compare them with a commercial material [

14]. On the other hand, Casanovas et al. [

15] prepared several catalytic honeycombs loaded with noble metals (Pt, Pd, Rh or Ru) or Ni over La-stabilized CeO

2. It is important to highlight that the studies of Tosti et al. [

2,

3,

14] were performed in a membrane reactor (MR) with the separation of H

2, while the work of Casanovas et al. [

2] was performed in a traditional reactor (TR) at high temperatures (≥600 °C). More recently, it was found by Rocha et al. [

8,

9,

10] that commercial Rh-based catalysts and a prepared catalyst loaded with Ni and Ru presented high catalytic performance (in terms of the H

2 yield—maximum of 9 mol

H2·mol

OMW−1), H

2 selectivity, stability and total organic carbon (TOC) conversion. Nevertheless, until now, no studies have been found in the literature related to the effect of the preparation methods on the performance of the Ni-based catalysts. In particular, none of these previous studies focused on developing new Ni-based materials to improve the economic viability of the reaction under investigation. Moreover, limited attention was paid to carbon production on the catalysts, and the range of pressures explored was narrow, typically restricted to atmospheric pressure.

The present work aims to evaluate the performance of a TR at various pressures for the OMWSR process, using two types of catalysts: one commercial (material that presented the best catalytic performance in a previous scientific work [

10] acting as a reference sample)—Rh/Al

2O

3—and five new samples prepared in the laboratory—a series of Ni-Ru/Ce-SiO

2 catalysts. The prepared catalysts were also doped with Ce, since it was observed that the addition of this promoter improved the stability of the materials [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The main novelty of this work is the utilization of a series of Ni-Ru/Ce-SiO

2 catalysts prepared with different methods (namely, with different calcination programs and different impregnation steps) that have never been applied in the OMWSR reaction, and the study of the effect of the pressure and oxidative regeneration treatments on this process. To evaluate the performance of the catalysts, the results were analyzed in terms of the H

2 yield, H

2 selectivity, TOC conversion and stability of the catalysts. It was expected to obtain a TOC conversion close to 100% and an H

2 yield higher than 9 mol

H2·mol

OMW−1 (considering previous studies by the research group) [

8,

10].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Gases

Nitrogen (≥99.999%—used as the carrier gas in the catalytic experimental tests and the makeup gas for the gas chromatograph (GC Agilent 7820A—Santa Clara, CA, USA), respectively), reconstituted air (≥99.999%—used as the oxidant agent during the catalyst regeneration program of the catalyst), argon (≥99.999%—the makeup gas for the GC) and hydrogen (≥99.999%—for the GC and catalyst activation) were supplied by Linde (Dublin, Ireland).

All the components present in the synthetic OMW effluent (vanillic, gallic, cinnamic, 4-hydroxybenzoic and syringic acids, L-arabinose and D-galactose) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Waltham, MA, USA), except the veratric and protocatechuic acids, obtained from Acros Organics, and tyrosol, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). An aqueous solution of HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥37 wt.%) and an aqueous solution of HNO3 (JMGS, Odivelas, Portugal, ≥65 wt.%) were used in the ICP-OES technique analyses.

3.2. Catalysts and OMW Preparation

One commercial catalyst—Rh/Al2O3 promoted with an alkaline earth metal, manufactured by Johnson Matthey (herein called by Rh)—and five prepared catalysts—Ni-Ru-based catalysts supported on SiO2 and doped with CeO2 (herein called Ni-Ru/Cex, with x varying from 1 to 5)—were used in this work. All the precursors of the metals and the support were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

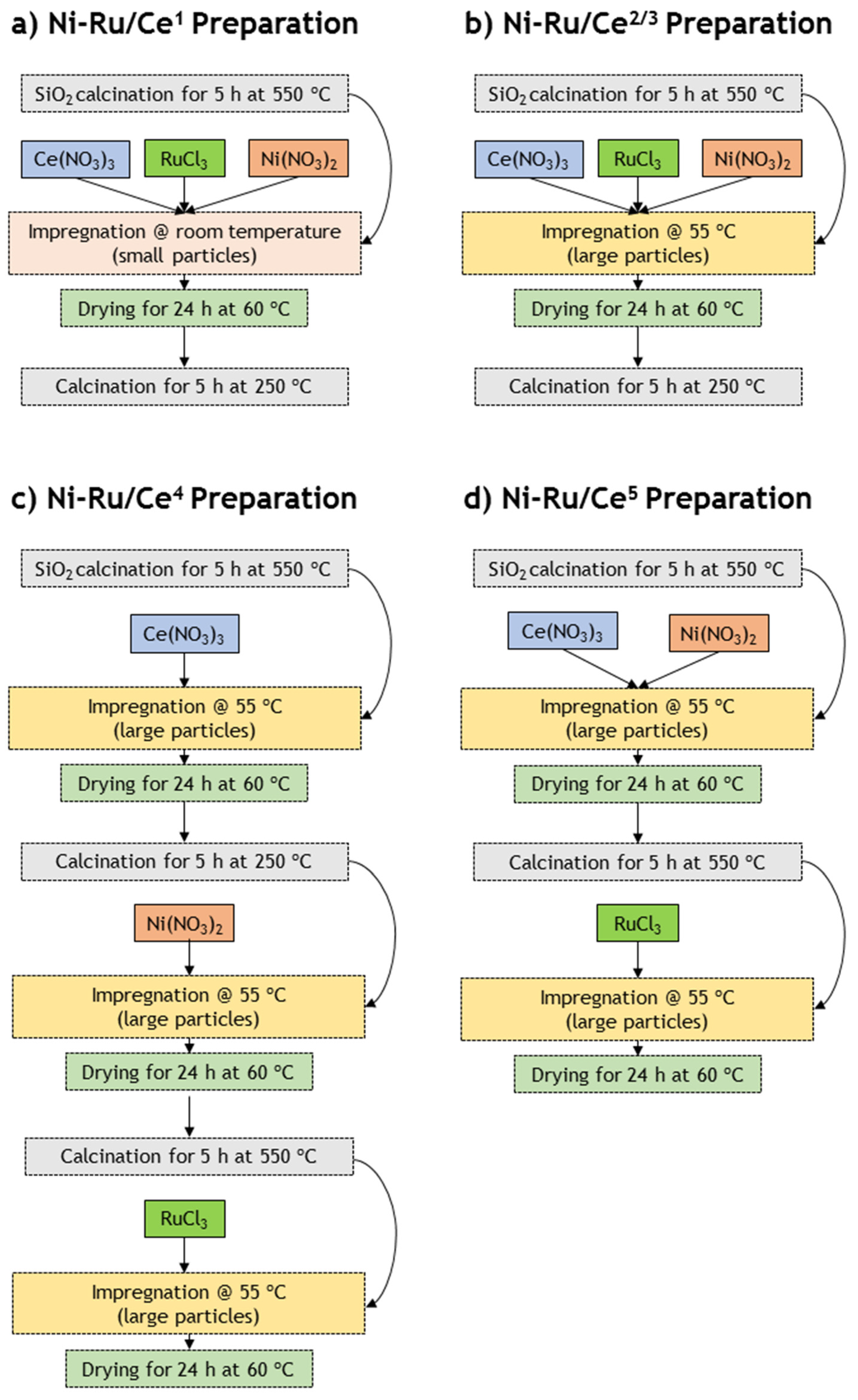

A series of Ni-Ru/Ce catalysts were synthesized using different preparation methods using SiO

2 as support and CeO

2 as promoter—see

Table 5. First, before the metal loading, SiO

2 was calcined during 5 h at 500 °C (heating rate of 5 °C·min

−1) to activate the support, as mentioned in previous works [

49,

50]. Then, in order to prepare the Ni-Ru/Ce

1 (

Figure 6a) and Ni-Ru/Ce

2 (

Figure 6b) samples (see the methodology in

Figure 6 and

Table 5), the activated support was impregnated (wet impregnation) with an aqueous solution of Ni(NO

3)

2·6H

2O, RuCl

3·H

2O and Ce(NO

3)

3·6H

2O dissolved simultaneously in water, with the aim of achieving a final Ni content of 10 wt.%, Ru content of 1 wt.% and Ce content of 0.3 wt.%. The Ni-Ru/Ce

3 (

Figure 6b) sample was prepared using the same procedure (cf.

Figure 6 and

Table 5), however with the aim of achieving a final Ce content of 3 wt.%. These three catalysts were dried at 60 °C (during 24 h) and calcined at 250 °C (during 5 h—heating rate of 5 °C·min

−1) in the final preparation procedures. The calcination temperature of these catalysts was chosen considering the TGA results obtained in a previous work [

8]; particularly, it was possible to verify that at high temperatures (>270 °C), the catalyst decomposed due to the volatilization of Ru, as also verified in other studies [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55].

The preparation of the Ni-Ru/Ce

4 (

Figure 6c) and Ni-Ru/Ce

5 (

Figure 6d) samples followed a distinct preparation method (see

Figure 6 and

Table 5). In the production of the Ni-Ru/Ce

4 catalyst, the activated support was, firstly, impregnated (wet impregnation) only with an aqueous solution of Ce(NO

3)

3·6H

2O dissolved in water; then, the sample was dried at 60 °C (during 24 h) and calcined at 250 °C (during 5 h—heating rate of 5 °C·min

−1)—higher temperatures are not required to form CeO

2 [

56,

57]. At that point, the sample was impregnated again (wet impregnation) with an aqueous solution of Ni(NO

3)

2·6H

2O, dried again at 60 °C (during 24 h) and calcined at 550 °C (during 5 h, 5 °C·min

−1). Lastly, the sample was impregnated (wet impregnation) with an aqueous solution of RuCl

3·H

2O and, finally, only dried at 60 °C (during 24 h) to avoid Ru evaporation. To produce the Ni-Ru/Ce

5 catalyst, the activated support was, firstly, impregnated with an aqueous solution of Ce(NO

3)

3·6H

2O and Ni(NO

3)

2·6H

2O dissolved simultaneously in water, dried at 60 °C (24 h) and calcined at 550 °C (during 5 h, 5 °C·min

−1). Then, the sample was impregnated with an aqueous solution of RuCl

3·H

2O and only dried at 60 °C (during 24 h).

In addition, the aqueous solution prepared for the production of the Ni-Ru/Ce

1 catalyst was stirred at a lower temperature (room temperature) than the other aqueous solutions considered in this work (stirred at 55 °C)—see

Table 5. The calcination treatments applied for all the materials were performed with the purpose of removing volatile species (e.g., H

2O and NO

32−) and promoting the formation of metal oxides (e.g., NiO). The calcination temperatures used in the treatment of these catalysts was similar to the ones selected for identical materials prepared in previous works [

58,

59,

60]. The size of the support particles (SiO

2—between 210 and 500 or 1410 and 3360 μm) was controlled before the impregnation of the metals, using a sieve.

The selected metal loadings were based on previous studies that employed similar compositions [

8,

61]. A relatively low Ru content (1 wt.%) was chosen due to its high cost, while still being sufficient to promote catalytic activity. The Ni loading of 10 wt.% is commonly used in the literature to ensure adequate active phase dispersion, and the Ce content was varied (0.3–3 wt.%) to evaluate its effect on the catalyst performance. Summing up, and considering the description of the preparation methods utilized (see

Figure 6), it was possible to observe that the preparation parameters studied in this work were the particles size, temperature of the impregnation, content of Ce, order of the metal’s impregnation and calcination programs. It is important to emphasize that careful control of the stirring temperature during catalyst preparation is very important to control the morphology of the material, which in turn influences the catalyst’s efficiency and longevity in steam reforming reactions.

The synthetic OMW was composed of a mixture of six different phenolic acids and two sugars typically present in real OMW streams (see

Table 6). The concentrations of the components were adjusted according to several reports in the literature, namely they were based on the compositions defined with OMW real streams [

4,

62,

63,

64,

65]. The compounds were dissolved in distilled water and then the solution was submitted to ultrasound (Sonorex Super RK255H from Bandelin Electronic GmbH & Co. KG [Berlin, Germany]) for 15 min to ensure full dissolution (the steam to carbon feed ratio was equal to 694).

3.3. OMW and Catalysts Characterization

The total organic carbon (TOC) was determined by catalytic oxidation at 698 °C (method 5310 D [

66]) with a TC/TOC analyzer (Shimadzu TOC-L apparatus equipped with an auto-sampler, which was operated at a maximum coefficient of variation ≤ 2%). A TOC of 972 ppm was observed for the initial effluent of OMW used in this research work.

In situ temperature-programmed reduction (TPR-H

2), in a custom-built facility, of all the Ni-Ru/Ce catalysts (around 1 g) was carried out after thermal treatment at 150 °C for 1.5 h under N

2 flow (100 mL

N∙min

−1) to remove the water. Thereafter, the sample was cooled down to room temperature and then heated up to 820 °C (10 °C∙min

−1) under a flow rate of 10 mL

N∙min

−1 of H

2 diluted with 90 mL

N∙min

−1 of N

2 (10 vol.% H

2 in N

2). For the in situ temperature-programmed desorption (TPD-CO

2) of the Ni-Ru/Ce samples, the fresh catalysts (around 200 mg) were first reduced (see in

Section 3.4 the activation program applied in this work, based on the TPR-H

2 results). Then, the methodology was analogous to the one reported elsewhere [

67]: the catalysts were fully saturated with CO

2 at room temperature for 1 h under CO

2 flow (30 mL

N∙min

−1). The setup was flushed with N

2 for 30 min and the catalyst was heated up to 820 °C at 10 °C∙min

−1 (under a flow of 30 mL

N∙min

−1 of pure N

2).

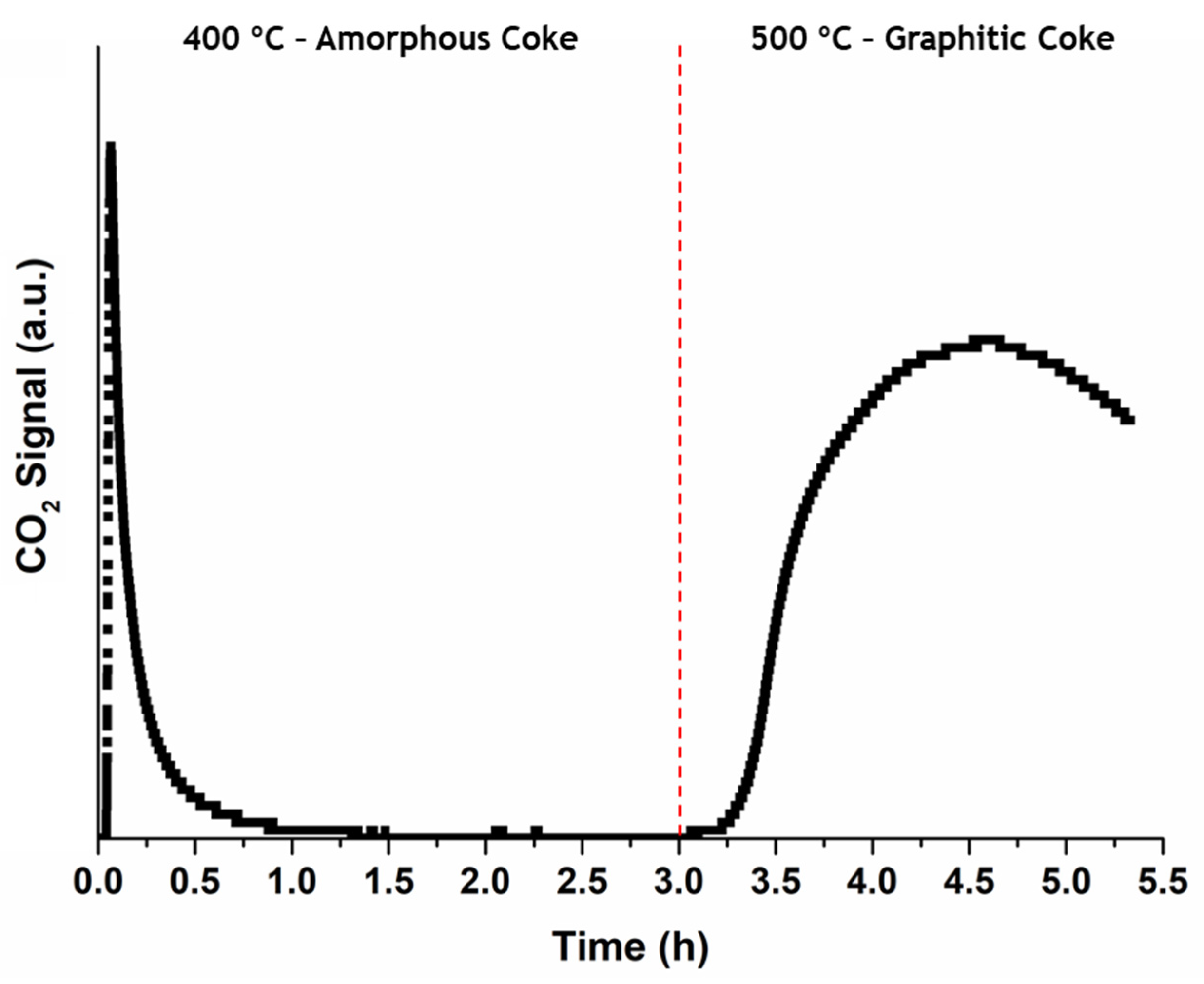

For the in situ temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) analyses/oxidative regeneration of the catalysts, the samples of spent catalysts were treated with a flow of 25 mL

N∙min

−1 of reconstituted air (20 vol.% O

2/N

2 stream; similar to air composition, thus cheaper in industrial practice) diluted in 75 mL

N∙min

−1 of N

2, first at 400 °C and then at 500 °C—the duration of this program at both temperatures was object of study in this work. Air was diluted in nitrogen during the TPO to avoid the temperature gradients observed in previous works [

43]. The amount of carbon gasified in the form of CO

2 and CO was measured with an online infrared-based analyzer (Servomex, model 4210). The CO and CO

2 outlet concentrations obtained in the TPR-H

2 runs were also monitored with this analyzer.

The metal contents of the Ni-Ru/Ce catalysts were determined by inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) using an iCAP 7000 spectrophotometer from Thermo Scientific. Prior to the analysis, the samples were digested in a mixture of HCl and HNO3 (10:1) at 250 °C using a Start D Microwave Digestion System from Milestone. Then, 10 mg of each sample was digested and then diluted with ultrapure water until reaching 50 mL. Any possible support residues remaining after digestion were eliminated by filtration.

3.4. Catalytic Experiments and Performance Indicators

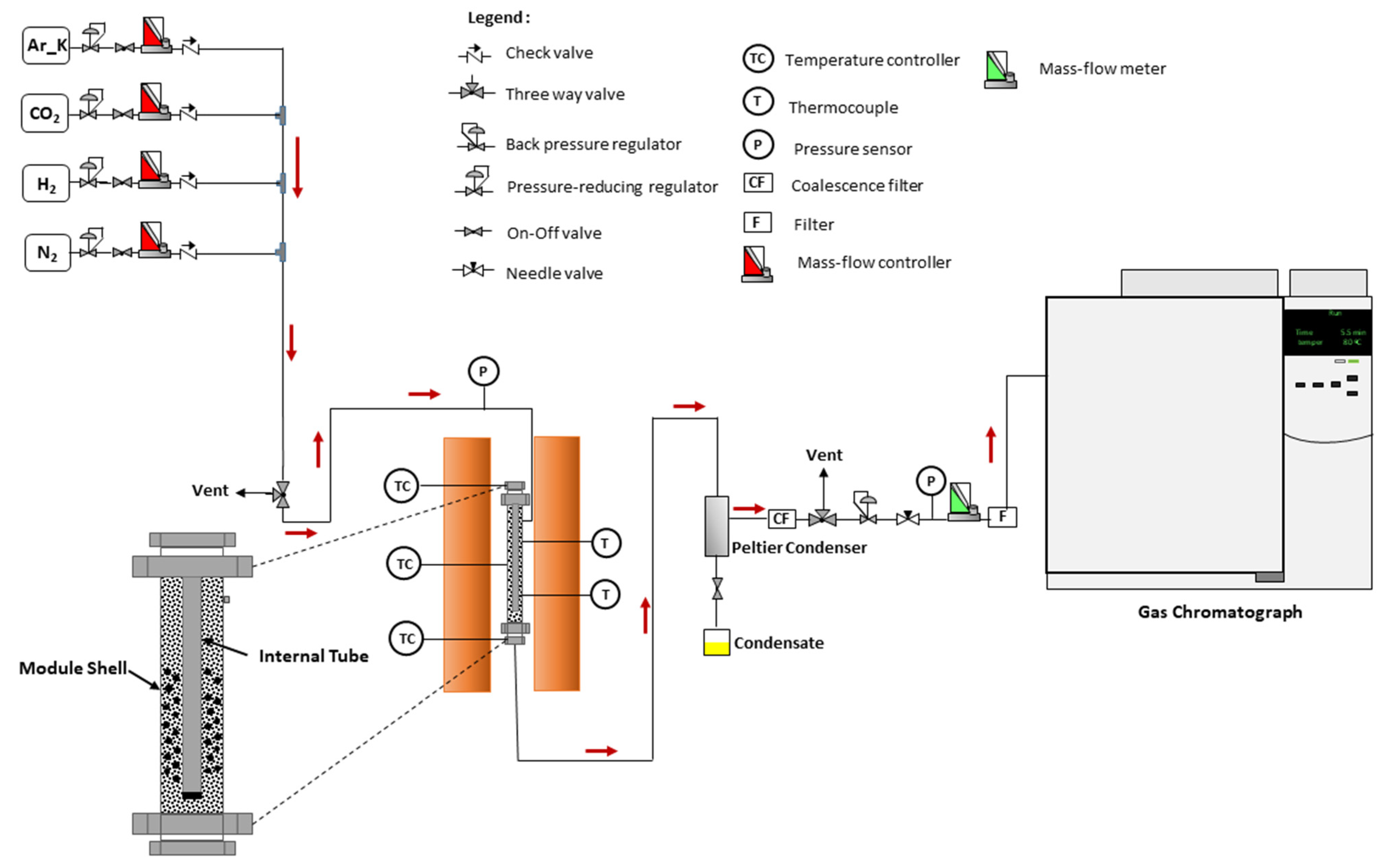

The experimental tests were performed in a custom-built stainless-steel module that consists of two concentric tubes with different diameters: a stainless-steel module shell with 32 cm of length and 4 cm i.d. and a stainless-steel tube closed at both ends with 30 cm of length and 12.7 mm o.d. The packed-bed with the catalyst and inert is localized between these 2 tubes (reaction medium with 12 cm of length) and, in this way, the feed stream flows through the annular section during the reaction (see the detail in

Figure 7)—this configuration was considered since it is expected to use the best material in multifunctional reactors (namely in a membrane reactor). At the bottom and upper parts of the module, a layer of SiC smooths the flow of the reaction mixture. The module was placed inside a tubular oven (model Split from Termolab, Fornos Eléctricos, Lda., Águeda, Portugal) equipped with a 3-zone PID temperature controller (model MR13 from Shimaden, Nerima City, Japan). The thermocouples used to evaluate and control the oven temperature were placed in the same radial position in the oven and very close to the column wall. In addition, a thermocouple recorded the temperature inside the module (inside the reaction medium). N

2 was fed into the reactor using a mass flow controller (model F201 from Bronkhorst-High Tech, Ruurlo, The Netherlands), while the OMW solution was fed by an HPLC pump (Eldex, 1LMP) and forced to pass through an evaporation/mixing zone at 400 °C before entering the reactor. The pressure in the system was measured by means of two pressure transducers (model PMP 4010 from Druck) placed before and after the packed-bed unit. The liquid phase produced during the course of the reaction was condensed in a home-assembled Peltier cold trap located after the reactor (cf.

Figure 7). The tube and fittings between the module outlet and the first Peltier condenser were kept at 150 °C to avoid condensation. A system of two Peltier-based cold traps, a coalescence filter and a filter were used between the reactor and the analysis system to retain all the condensable species.

A gas chromatograph (GC-Agilent 7820A) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD using N2 as makeup gas) and a flame ionization detector (FID—with a methanizer and using He as makeup gas) was used to analyze the gaseous products. The chromatograph is also equipped with two columns (Plot Q (30 m × 0.32 mm) and Plot 5A (30 m × 0.32 mm)). The H2 was analyzed by TCD with Ar as a carrier gas to achieve a better response owing to the higher difference in thermal conductivity.

An oxidative regeneration program was considered in the catalytic experiments because it was previously observed that this treatment (promoting the coke deposits’ gasification) for several catalysts used in the OMWSR process allowed the recovery of the catalytic performance [

9,

43].

The catalysts were crushed, sieved (350–600 μm) and mixed with inert silicon carbide particles with the same particle size. Using this range of particle sizes, it is possible to neglect the gas–solid wall effects and the pressure drop in the reactor. Before the OMW steam reforming catalytic tests (also before the TPD-CO

2 analyses), the catalysts were activated (@ 400 °C during 2 h under a 10% H

2/N

2 stream—total flow rate of 100 mL

NPT·min

−1), taking into account the results of the TPR-H

2 analyses (see more details in

Section 2.1.1).

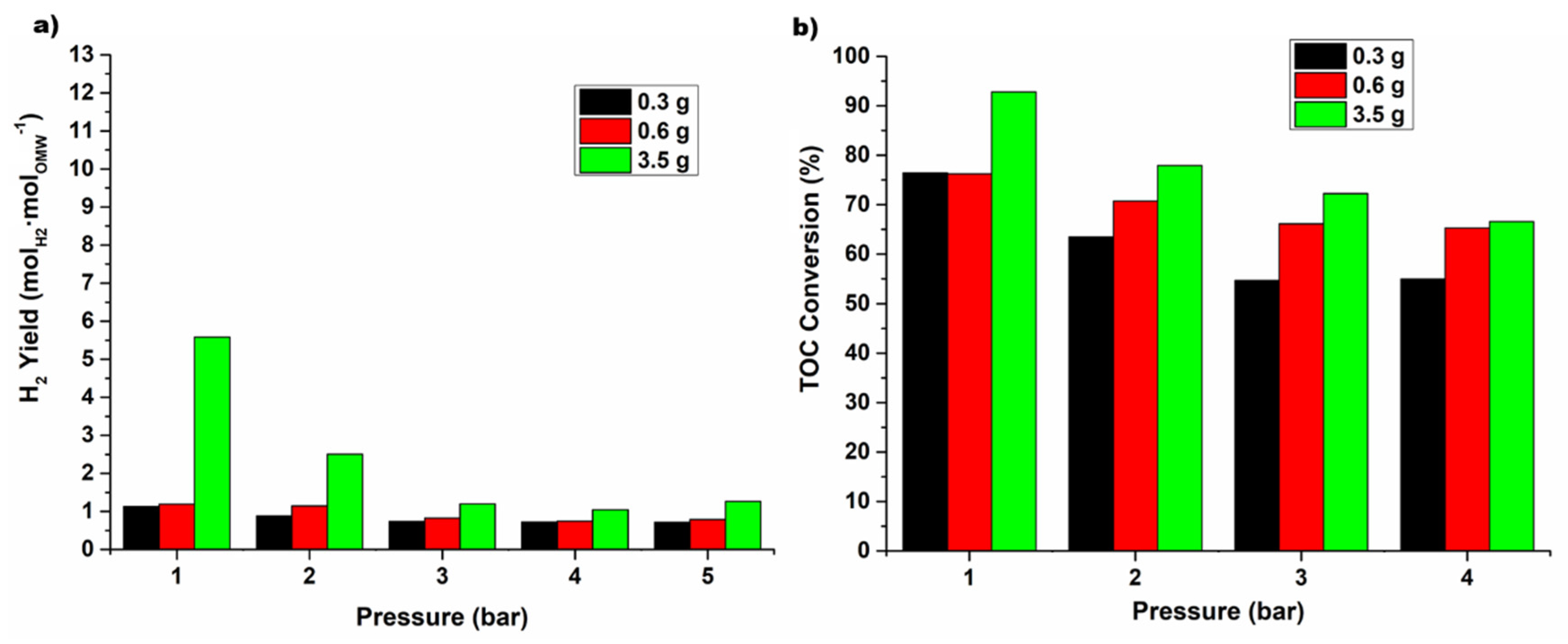

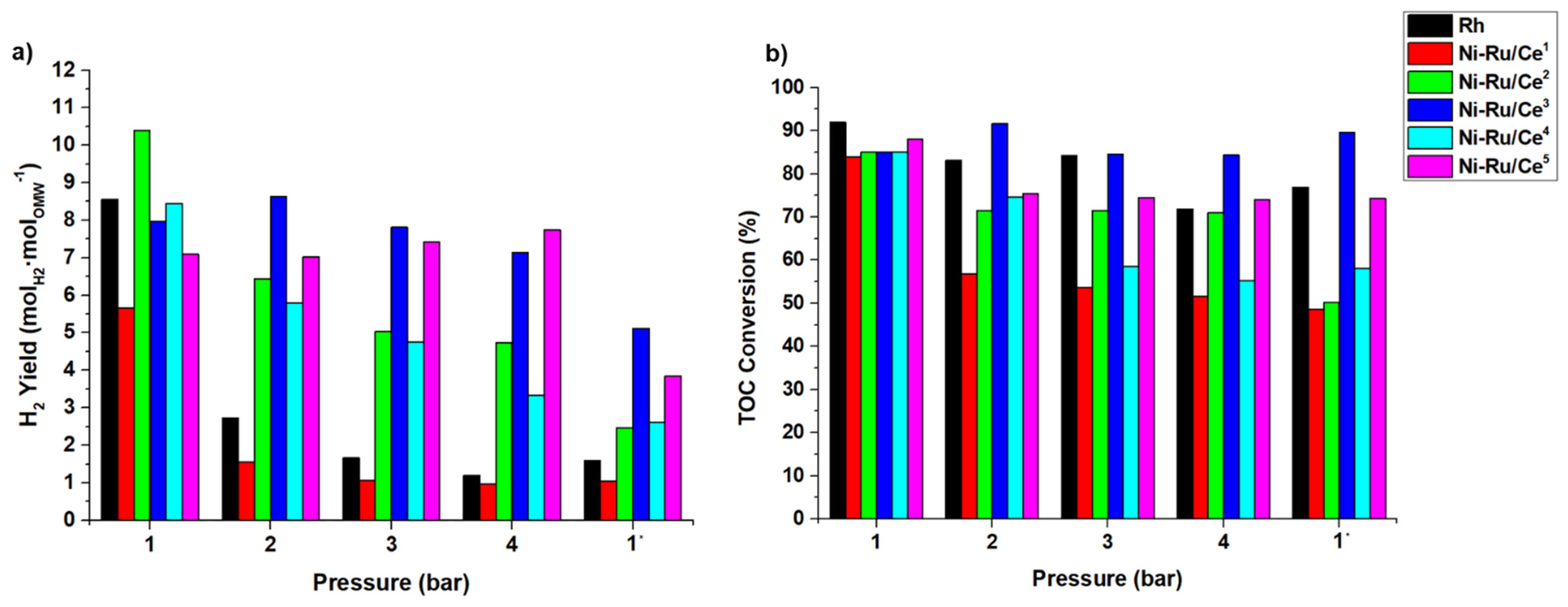

The operating conditions used in this work are shown in

Table 7. The blank tests, herein called

Exp. 0, in which the packed-bed reactor was filled only with inert SiC, was carried out for all the operation conditions studied in this work. In addition, two other different experimental runs were carried out. For the Rh-based catalyst, preliminary experimental tests (

Exp. 1) were carried out with different catalyst masses, from 0.3 to 3.5 g, to see the effect of the quantity of catalyst on the OMW conversion and H

2 production and to define the catalyst mass for the

Exp. 2. In

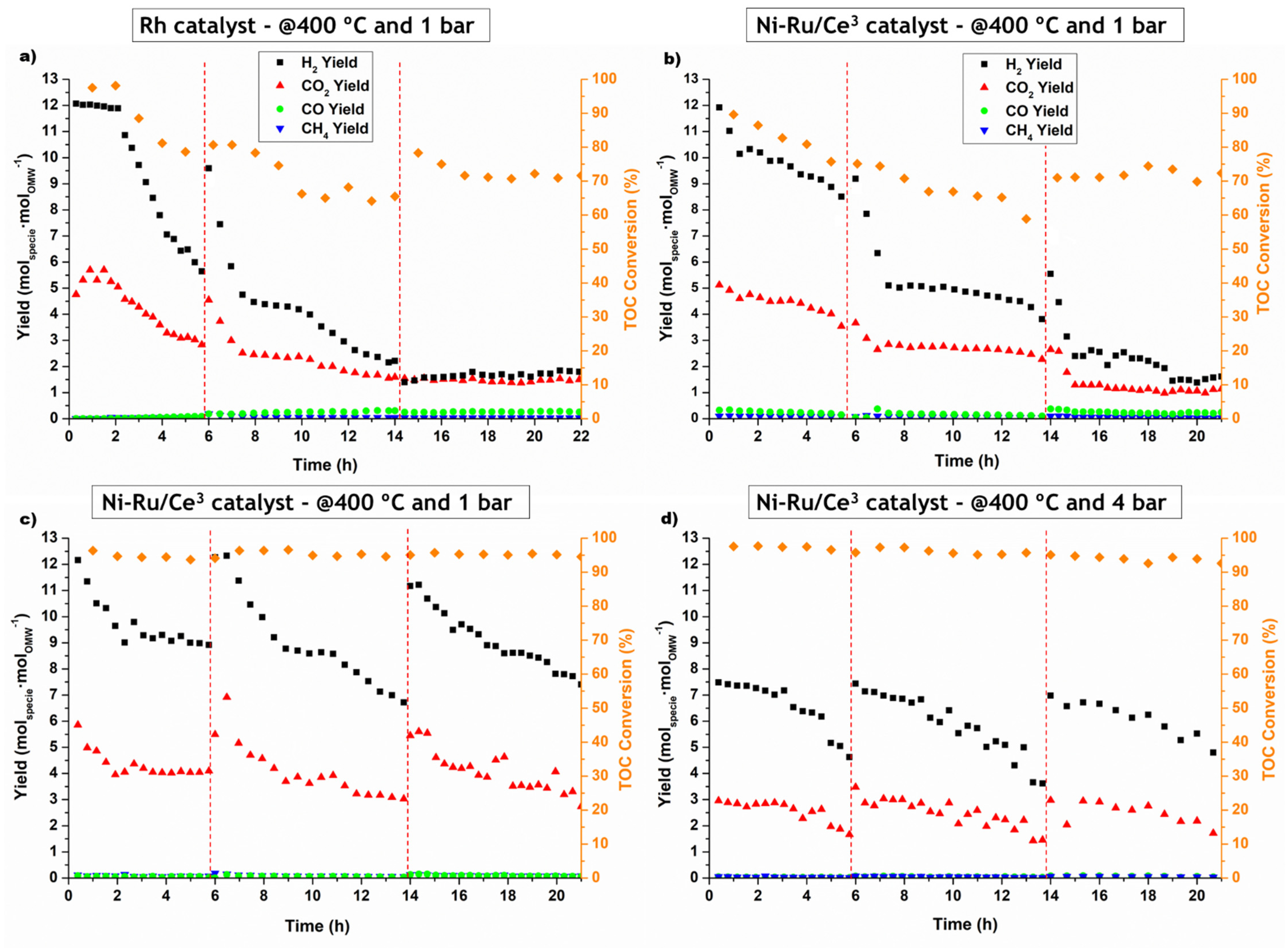

Exp. 2, a high quantity of catalysts was used (7 g) and, besides that, oxidative regeneration was always performed before changing the system pressure. Finally, in

Exp. 3, stability tests were performed during 24 h with the two catalysts with better performance in

Exp. 2. The catalyst oxidative regeneration was employed in

Exps. 2 and

3, since it was verified in a previous work that this treatment allowed almost complete recovery of the catalytic performance [

9]. In this work, the occurrence of two different combustion peaks was observed during the oxidative regeneration of the spent samples, below and above 500 °C, which were connected to the oxidation of amorphous and graphitic carbon deposits, respectively. In this work, for the in situ oxidative regeneration program used in

Exps. 2 and

3, the sample of spent catalyst was treated with a flow rate of 25 m

LN·min

−1 of reconstituted air (20 vol.% O

2 in N

2) diluted with 75 m

LN·min

−1 of N

2, first at 400 °C and then at 500 °C. The coke produced during the experimental tests of the

Exp. 3 runs was fully oxidized (the concentration of CO

2 measured at the reactor outlet was equal to zero at the end of the program). After this procedure, the catalyst was exposed to a reducing atmosphere (H

2), as described in this section.

Samples of the condensable phase were collected during all the experimental tests and analyzed in terms of the TOC. The system was always flushed with N2 (100 mLNPT·min−1) for 20 min between the treatment programs and before and after the catalytic tests in all the experimental runs.

In all the experimental runs, the OMW was fed into the evaporation system at a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL·min−1. Then, the vaporized OMW was carried into the reactor by the carrier gas (25 mLNPT·min−1 of N2).

The conversion of OMW during the reaction was analyzed by the TOC conversion—Equation (13):

where the subscripts “inlet” and “outlet” stand for the feed and outlet condensate streams, respectively. The yield of the reaction products was calculated by Equation (14), where

is the molar flow rate of component

i (H

2, CO

2, CO and CH

4) at the outlet stream and

is the molar flow rate of compounds present in the OMW flowing into the system.

4. Conclusions

Among the synthesized catalysts, Ni-Ru/Ce3 showed the best results upon a comparison of the performance of a series of Ni-Ru/Ce-SiO2 catalysts prepared by different methods. The Ni-Ru/Ce3 was prepared through a straightforward and reproducible method. All the catalysts tested in Exp. 2 presented deactivation over the experimental campaign, especially at 1 bar.

In the stability tests, it was confirmed that the catalysts suffer from pronounced deactivation at 1 bar when oxidative regeneration with a fixed time was employed. However, after total oxidative regeneration, complete recovery of the catalytic performance was observed in the stability tests at 1 and 4 bar and the stability of the catalyst increased.

Moreover, with complete oxidation of the coke, it was observed that the TOC conversion remains stable at approximately 95% over 24 h time-on-stream for both pressures and the H2 yield observed was always between 12 and 6.5 molH2·molOMW−1 and 7 and 3.5 molH2·molOMW−1 at 1 and 4 bar, respectively. With this study, it was concluded that this type of catalyst was significantly deactivated due mostly to the coke produced.

For future work, testing the best material with real OMW effluents and considering new oxidative regeneration program strategies are proposed.