Recent Advances and Techno-Economic Prospects of Silicon Carbide-Based Photoelectrodes for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Generation

Abstract

1. Introduction

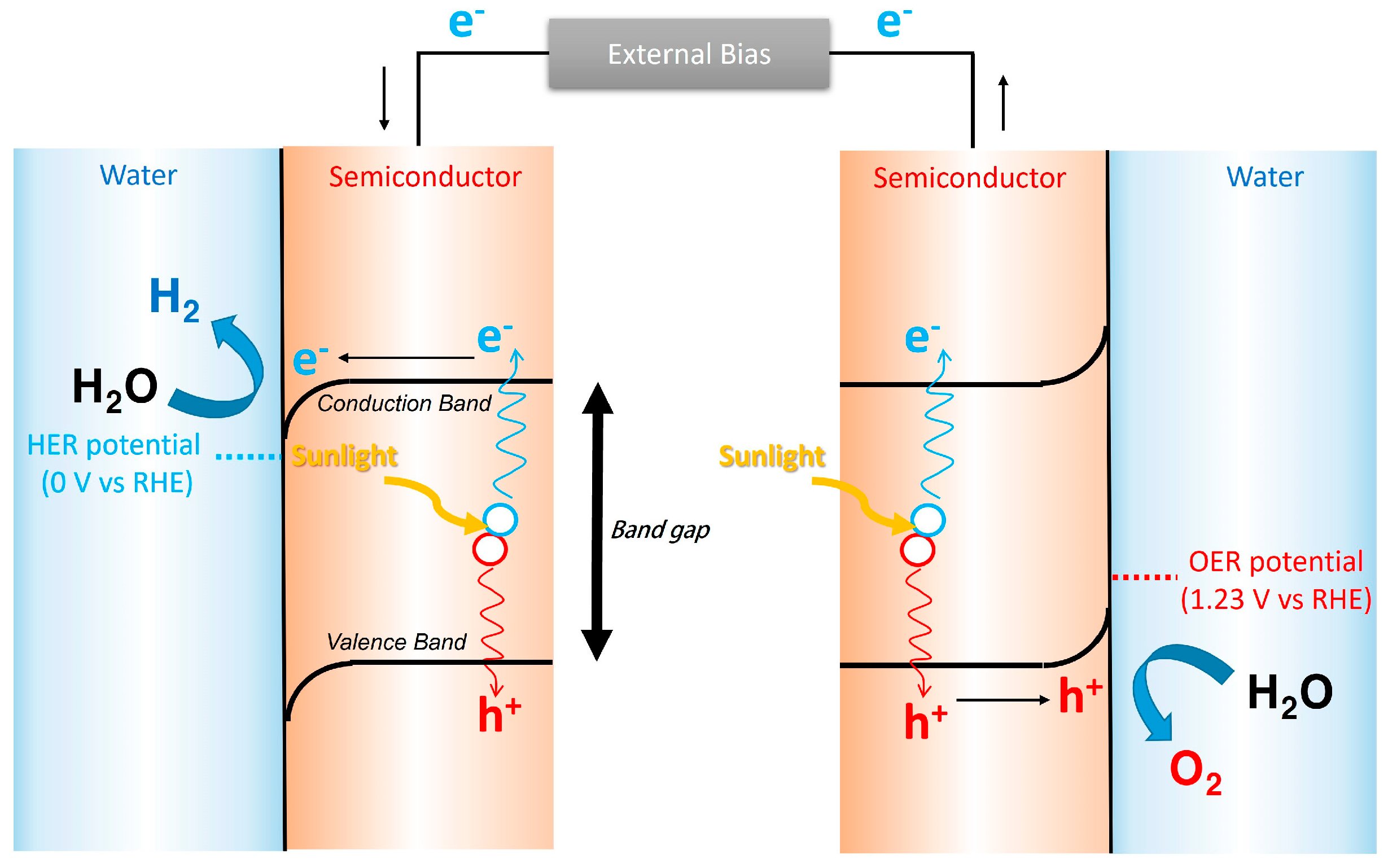

2. Fundamental PEC Principles

- (1)

- Photon absorption by the semiconductor (hv ≥ Eg), leading to exciton generation.

- (2)

- Charge separation and migration of photoinduced electrons and holes to the semiconductor–electrolyte interface.

- (3)

- Surface redox reactions at the photoanode and photocathode.

- (4)

- Optimization of electrolyte properties, including pH, concentration, and thickness, to balance ionic transport and optical transparency.

- (1)

- Overall reaction—2H2O(I) → 2H2(g) + O2(g)—Overall water splitting reaction requiring ≥ 1.23 eV per e−

- (2)

- Photoanode (oxidation)—2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e−—Oxygen evolution reaction (OER) driven by photogenerated holes (h+)

- (3)

- Photocathode (reduction)—4H+ + 4e− → 2H2—Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) driven by photogenerated electrons

- (4)

- Intermediate step 1—H2O + h+ → •OH + H+—Formation of hydroxyl radicals as reaction intermediates

- (5)

- Intermediate step 2—2•OH → H2O2—Recombination of hydroxyl radicals leading to H2O2 formation

- (6)

- Side reaction (undesired)—H2O2 + 2h+ → O2 + 2H+—Oxidation of hydrogen peroxide causing reduced Faradaic efficiency

- (7)

- Surface oxidation (SiC)—SiC + 2h+ + 2OH− → SiO2 + C + H2O—Possible surface oxidation under strong anodic bias

- (8)

- Recombination—e− + h+ → heat or luminescence—Non-productive recombination reducing PEC efficiency

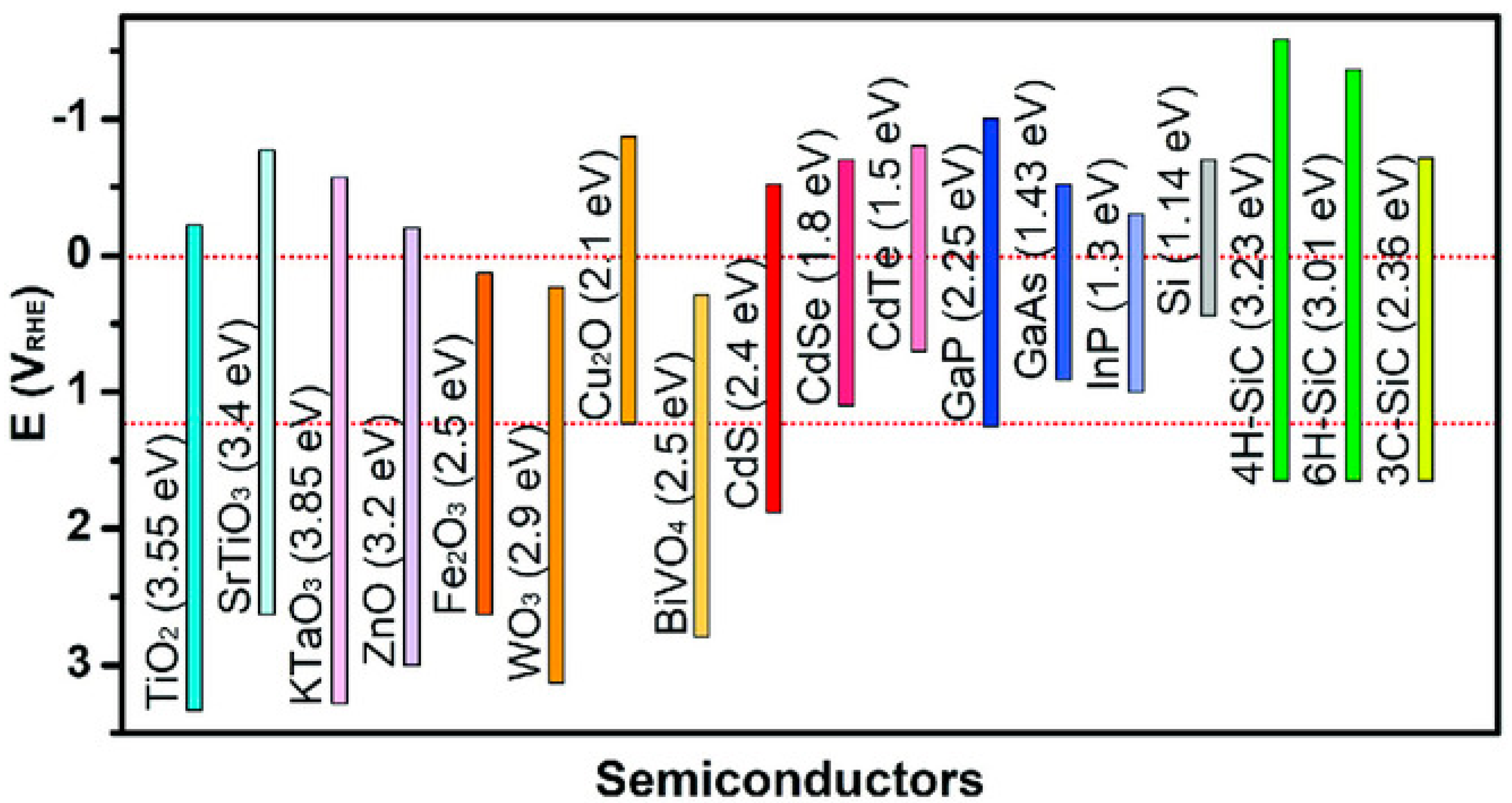

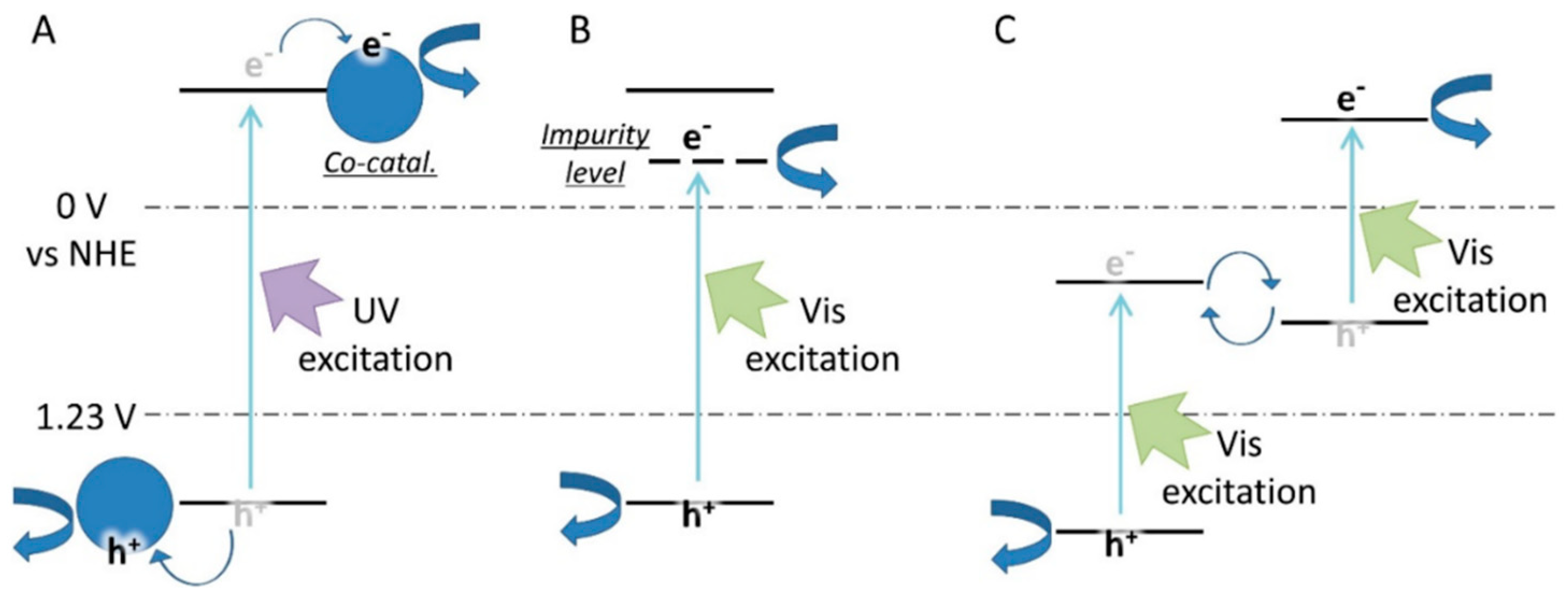

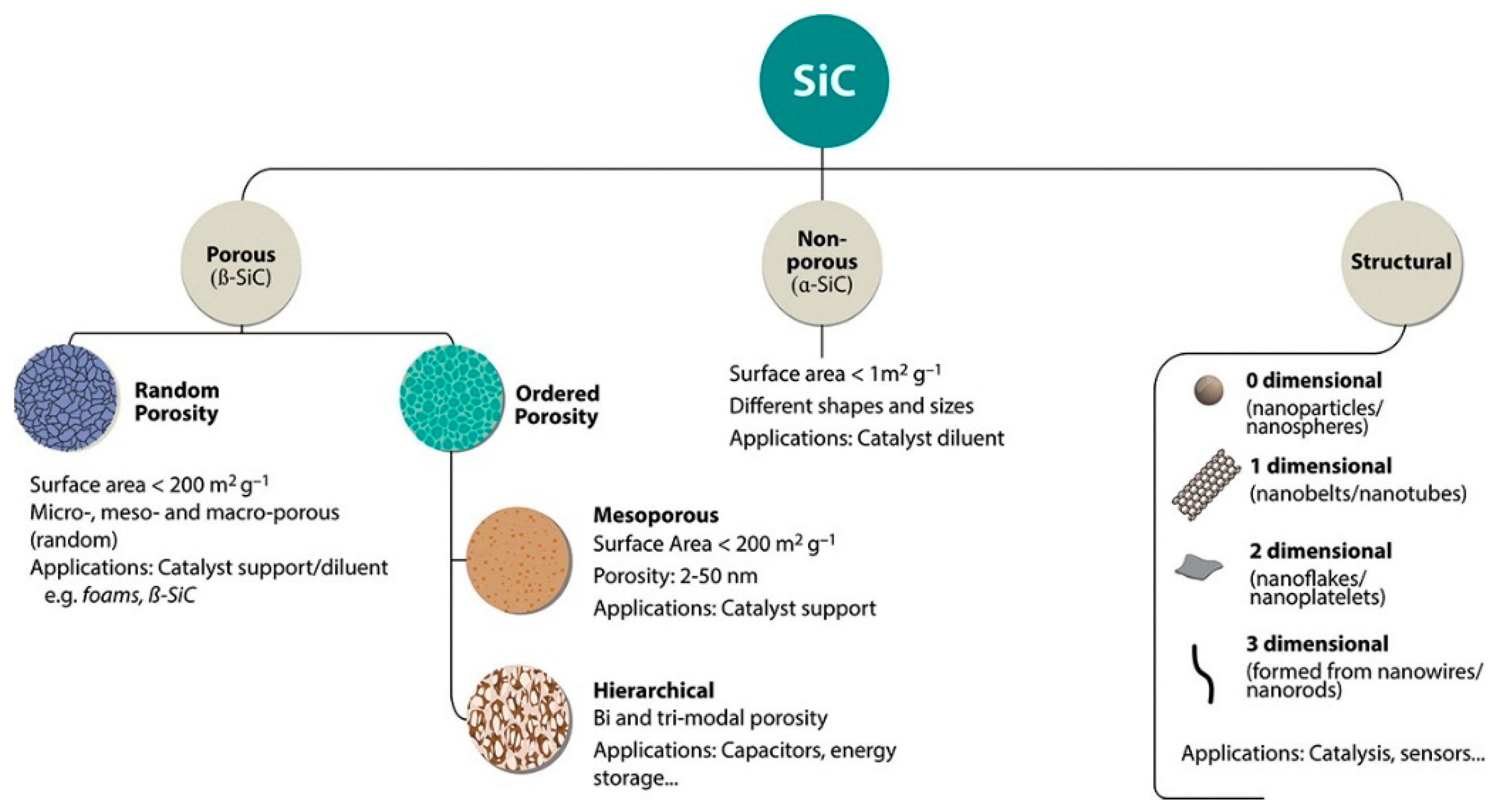

3. Silicon Carbide PEC Water Splitting

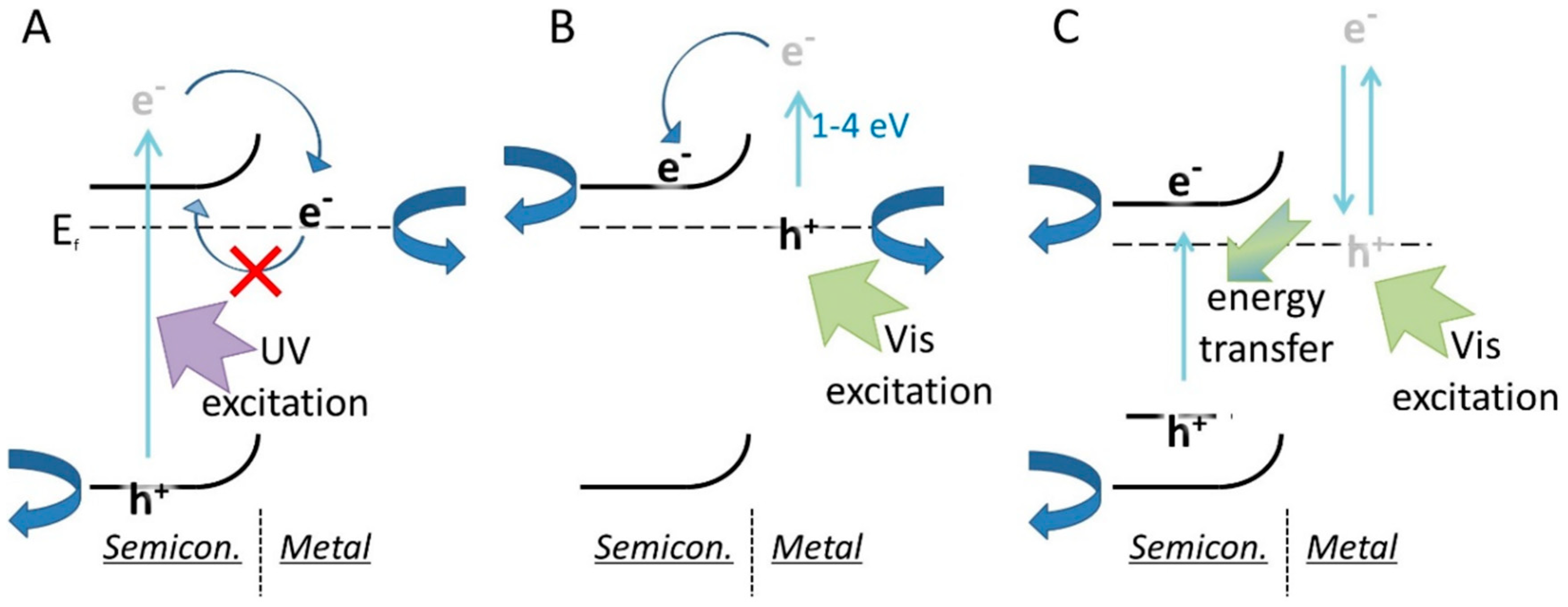

4. Co-Catalysts and Metallic Modifications

5. Data-Driven Technoeconomic Assessment of SiC-Based PEC Systems

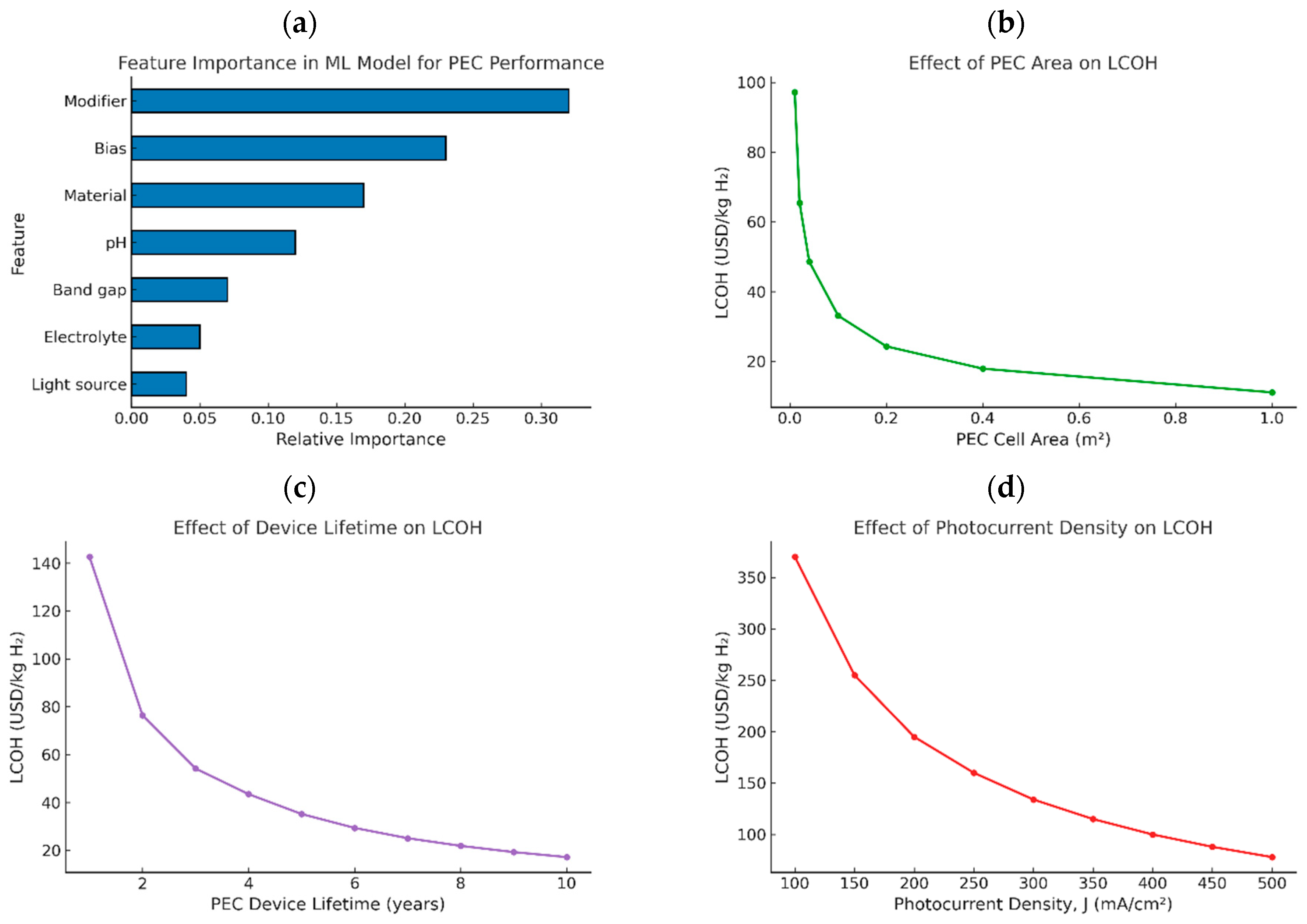

5.1. Machine Learning for Photocurrent Prediction

5.2. Baseline Technoeconomic Estimation

5.3. Scenario-Based Analysis of LCOH

5.4. Implications and Future Work

6. Outlooks

6.1. Materials and Structural Design

6.2. Performance and Stability Challenges

6.3. Scalability and System Integration

6.4. Data-Driven and AI-Assisted Optimization

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, L.; Li, Z.; Shang, X. Recent surficial modification strategies on BiVO4 based photoanodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting enhancement. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy 2024, 55, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Gao, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, L.; Yu, X.; Chi, S.; Liu, H.; Tian, G.; Zhao, X. Ni/N co-doped NH2-MIL-88(Fe) derived porous carbon as an efficient electrocatalyst for methanol and water co-electrolysis. Renew. Energy 2025, 244, 122661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Younis, M.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, L.; Peng, X.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Lei, L.; Hou, Y. Rational design on photoelectrodes and devices to boost photoelectrochemical performance of solar-driven water splitting: A mini review. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Fertig, D.; Kaiser, B.; Jaegermann, W.; Blug, M.; Hoch, S.; Busse, J. Preparation and characterization of GaP semiconductor electrodes for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Energy Procedia 2012, 22, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volokh, M.; Shalom, M. Polymeric carbon nitride as a platform for photoelectrochemical water-splitting cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2023, 1521, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, H.; Hua, J.; Tian, H. Recent advances in dye-sensitized photoelectrochemical cells for water splitting. EnergyChem 2019, 1, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. Stable photoelectrochemical salt-water splitting using the n-ZnSein-Ag8SnS6 photoanodes with the nanoscale surface state capacitances. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 87, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulfin, B.; Carmo, M.; van de Krol, R.; Mougin, J.; Ayers, K.; Gross, K.; Marina, O.; Roberts, G.; Stechel, E.; Xiang, C. Advanced water splitting technologies development: Best practices and protocols. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1149688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Guidat, M.; Nusshör, M.; Renz, A.; Möller, K.; Flieg, M.; Lörch, D.; Kölbach, M.; May, M. Photoelectrochemical Schlenk cell functionalization of multi-junction water-splitting photoelectrodes. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, M. Key Strategies on Cu2O Photocathodes toward Practical Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussupov, K.; Beisenkhanov, N.; Bakranova, D.; Keinbai, S.; Turakhun, A.; Sultan, A. Low-Temperature Synthesis of α-SiC Nanocrystals. Phys. Solid State 2019, 61, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakranova, D.; Kukushkin, S.; Nussupov, K.; Osipov, A.; Beisenkhanov, N. Epitaxial Silicon Carbide Films Grown by New Method of Replacement of Atoms on the Surface of High-resistivity (111) Oriented Silicon. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 43, 01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.X.; Sun, J.W. A Review of Recent Progress on Silicon Carbide for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Solar RRL 2020, 4, 2000111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Mu, X.; Cui, A.; Shan, G. Cu ions intercalated GO/Cu2O photocathode-enabled promotion on charge separation and transfer for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 969, 172432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Peng, Y.; Li, C.; Hou, Z. The co-decorated TiO2 nanorod array photoanodes by CdS/CdSe to promote photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 32055–32068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yan, L.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Z. TiO2/CeO2 core/shell heterojunction nanoarrays for highly efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12276–12283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitov, B.; Kurbanbekov, S.; Bakranova, D.; Abdyldayeva, N.; Bakranov, N. Study of the Photoelectrochemical Properties of 1D ZnO Based Nanocomposites. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Low, P.J.; Sun, H. Photocatalytic overall water splitting endowed by modulation of internal and external energy fields. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 17292–17327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Jin, T.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chi, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Fang, D.; Wang, J. Construction of a dual Z-scheme Cu|Cu2O/TiO2/CuO photocatalyst composite film with magnetic field enhanced photocatalytic activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 122019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Liu, Z.; Kato, M. Durable and efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting using TiO2 and 3C-SiC single crystals in a tandem structure. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Fan, G.Z.; Fu, H.W.; Li, Z.S.; Zou, Z.G. Tandem photoelectrochemical cells for solar water splitting. Adv. Phys.-X 2018, 3, 1487267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, M.; Sfaelou, S.; Dracopoulos, V.; Lianos, P. Platinum-free photoelectrochemical water splitting. Catal. Commun. 2014, 43, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, W.; Meng, L.; Tian, W.; Li, L. Recent Progress on Semiconductor Heterojunction-Based Photoanodes for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Small Sci. 2022, 2, 2100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakranova, D.; Seitov, B.; Bakranov, N. Preparation and Photocatalytic/Photoelectrochemical Investigation of 2D ZnO/CdS Nanocomposites. Chemengineering 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kuang, Y. Particle-Based Photoelectrodes for PEC Water Splitting: Concepts and Perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, S.; Lim, H.; Talib, Z.; Pandikumar, A.; Huang, N. Aerosol-assisted chemical vapor deposition of metal oxide thin films for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 2115–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yan, X.; Gu, Y.; Chen, X.; Bai, Z.; Kang, Z.; Long, F.; Zhang, Y. Large-scale patterned ZnO nanorod arrays for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 339, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Wang, A.; Wei, Y.; Pei, M.; Cao, R.; Gu, Z.; Yuan, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, K.; et al. Large-Area Printing of Ferroelectric Surface and Super-Domain for Solar Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 211118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, S.; Wu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, P.; Hou, M.; Liu, H.; Jiang, L.; Chen, X.; et al. SiC Substrate/Pt Nanoparticle/Graphene Nanosheet Composite Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 8958–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nariki, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Tanaka, K. Production of ultra fine sic powder from sic bulk by arc-plasma irradiation under different atmospheres and its application to photocatalysts. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 3101–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X. Synthesis and Characterization of N-Doped SiC Powder with Enhanced Photocatalytic and Photoelectrochemical Performance. Catalysts 2020, 10, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, F.; Wang, L.; Yang, W.; He, X.; Hou, H. Fabrication of CdS-decorated mesoporous SiC hollow nanofibers for efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tovar, R.; Fernández-Domene, R.; Montañés, M.; Sanz-Marco, A.; Garcia-Antón, J. ZnO/ZnS heterostructures for hydrogen production by photoelectrochemical water splitting. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 30425–30435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenova, T.; Zos’ko, N.; Pyatnov, M.; Aleksandrovsky, A.; Maksimov, N.; Zhizhaev, A.; Taran, O. Synthesis and Activation of TiO2 Photonic Crystal Structures for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. J. Sib. Fed. Univ.-Chem. 2024, 17, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Z. Strategies of Anode Materials Design towards Improved Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting Efficiency. Coatings 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyale, P.; Dongale, T.; Sutar, S.; Mullani, N.; Dhodamani, A.; Takale, P.; Gunjakar, J.; Parale, V.; Park, H.; Delekar, S. Boosting the photoelectrochemical performance of ZnO nanorods with Co-doped Zn-ZIFs metal-organic frameworks for water splitting studies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 61, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Ke, Z.; Ma, T.; Page, A. Defect Engineering for Photocatalysis: From Ternary to Perovskite Oxynitrides. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, S. Defect engineering of nanostructures: Insights into photoelectrochemical water splitting. Mater. Today 2022, 52, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ding, R.; Fu, Q.; Bi, L.; Zhou, X.; Yan, W.; Xia, W.; Luo, Z. A highly efficient MoOx/Fe2O3 photoanode with rich vacancies for photoelectrochemical O2 evolution from water splitting. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Kan, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y. Solution chemistry quasi-epitaxial growth of atomic CaTiO3 perovskite layers to stabilize and passivate TiO2 photoelectrodes for efficient water splitting. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, G.; Matsuda, A. Synthesis of Plasmonic Photocatalysts for Water Splitting. Catalysts 2019, 9, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, F.; Tahir, M. Photoelectrochemical water splitting with engineering aspects for hydrogen production: Recent advances, strategies and challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.Y.; Zhang, L.H.; Tong, X.; Liu, M.Z. Temperature Effect on Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting: A Model Study Based on BiVO4 Photoanodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 61227–61236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Shan, P.; Qin, H.; Guo, F.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Magnetic-field-induced activation of S-scheme heterojunction with core-shell structure for boosted photothermal-assisted photocatalytic H2 production. Fuel 2024, 373, 132394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting of CaBi6O10 decorated with Cu2O and NiOOH for improved photogenerated carriers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 13276–13283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Lougou, B.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, J.; Huang, X. Combined heat and mass transfer analysis of solar reactor integrating porous reacting media for water and carbon dioxide splitting. Sol. Energy 2022, 242, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Introduction and preliminary testing of a 5 m3/h hydrogen production facility by Iodine-Sulfur thermochemical process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25117–25129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Nagasawa, H.; Kanezashi, M.; Tsuru, T. SiC mesoporous membranes for sulfuric acid decomposition at high temperatures in the iodine-sulfur process. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41883–41890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Konietzky, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Experimental study on the dynamic mechanical behaviors of silicon carbide ceramic after thermal shock. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 24, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jin, Z.; Bai, L.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X. A catalyst-free amorphous silicon-based tandem thin film photocathode with high photovoltage for solar water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 15583–15590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakranov, N.; Kuli, Z.; Mukash, Z.; Bakranova, D. SiC-based heterostructures and tandem PEC cells for efficient hydrogen production. Results Eng. 2025, 275, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yin, X.; Li, X. Effect of Substrates on the Characteristics of Silicon Carbide Deposited from Methyltrichlorosilane. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 295–297, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Cheng, L.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y. Oxidation protective multilayer CVD SiC coatings modified by a graphitic b-c interlayer for 3D C/SiC composite. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2006, 13, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cheng, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, G. Dielectric properties of the SiC fiber-reinforced SiC matrix composites with the CVD SiC interphases. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 491, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmik, J. β-SiC growth on Si by reactive-ion molecular beam epitaxy. Acta Phys. Slovaca 2000, 50, 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Fissel, A. Molecular beam epitaxy of semiconductor nanostructures based on SiC. Silicon Carbide Relat. Mater. 2005, 483, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas, E.; Boudinov, H.; Maltez, R. Ion beam synthesis of SiC on Si toward the radiation damage free limit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B—BEAM Interact. Mater. At. 2019, 445, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashchenko, A.; Kukushkin, S.; Osipov, A. Nanoindentation of Nano-SiC/Si Hybrid Crystals and AlN, AlGaN, GaN, Ga2O3 Thin Films on Nano-SiC/Si. Mech. Solids 2024, 59, 605–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouravleuv, A.; Kazakin, A.; Nashchekina, Y.; Nashchekin, A.; Ubyyvovk, E.; Astrahanceva, V.; Osipov, A.; Svyatec, G.; Kukushkin, S. Top-Down Formation of Biocompatible SiC Nanotubes. Semiconductors 2024, 58, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukushkin, S.; Markov, L.; Osipov, A.; Svyatets, G.; Chernyakov, A.; Pavlov, S. Thermal Conductivity of Hybrid SiC/Si Substrates for the Growth of LED Heterostructures. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2023, 49, S327–S329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, D.; Pan, N.; Yuan, W. Heterogeneous nucleation of CdS to enhance visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of SiC/CdS composite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 012102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Gao, L.; Li, Y. SiC nanowire film grown on the surface of graphite paper and its electrochemical performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 605, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Luna, L.; DelaCruz, S.; Ortaboy, S.; Rossi, F.; Salviati, G.; Carraro, C.; Maboudian, R. Hierarchical cobalt oxide-functionalized silicon carbide nanowire array for efficient and robust oxygen evolution electro-catalysis. Mater. Today Energy 2018, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, S.; Velisoju, V.; Tavares, F.; Dikhtiarenko, A.; Gascon, J.; Castaño, P. Silicon carbide in catalysis: From inert bed filler to catalytic support and multifunctional material. Catal. Rev.-Sci. Eng. 2023, 65, 174–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jian, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Sun, J. Nanoporous 6H-SiC Photoanodes with a Conformal Coating of Ni-FeOOH Nanorods for Zero-Onset-Potential Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 7038–7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Jokubavicius, V.; Syväjärvi, M.; Yakimova, R.; Sun, J. Nanoporous Cubic Silicon Carbide Photoanodes for Enhanced Solar Water Splitting. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 5502–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Jiang, F.; Lu, X.; Ma, Y.; Fu, D.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, F.; Chen, S. Carbon-based hole storage engineering toward ultralow onset potential and high photocurrent density of integrated SiC photoanodes. Carbon 2023, 202, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Ping, Y.; Galli, G. Modelling heterogeneous interfaces for solar water splitting. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M.; Orlov, A. Developing new understanding of photoelectrochemical water splitting via “in-situ” techniques: A review on recent progress. Green Energy Environ. 2017, 2, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandjou, F.; Haussener, S. Modeling the Photostability of Solar Water-Splitting Devices and Stabilization Strategies. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 43095–43108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monny, S.; Wang, Z.; Konarova, M.; Wang, L. Bismuth based photoelectrodes for solar water splitting. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 61, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, X. Interaction between water molecules and 3C-SiC nanocrystal surface. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 2014, 57, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, I.; Memming, R.; Meissner, D. Electrochemical properties of silicon carbide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Chen, J.J.; Wang, M.M.; Liu, Z.X.; Ding, L.J.; Li, Y. Enhanced photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical activities of SnO2/SiC nanowire heterostructure photocatalysts. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 658, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Liao, X.; Ding, L.; Chen, J. The flexible SiC nanowire paper electrode as highly efficient photocathodes for photoelectrocatalytic water splitting. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 806, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, X.; Du, Z.; Yan, W.; Li, J.; Mujear, A.; Shao, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Fabrication and performance of 3C-SiC photocathode materials for water splitting. Prog. Nat. Sci.-Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Zang, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhao, X.; Fan, H.; Qiu, Y. One-dimensional Au/SiC heterojunction nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical performances: Kinetics and mechanism insights. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 267, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shang, H.; Shi, Y.; Yakimova, R.; Syväjärvi, M.; Zhang, L.; Sun, J. Atomically manipulated proton transfer energizes water oxidation on silicon carbide photoanodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 24358–24366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y. Preparation of carbon dots/TiO2 electrodes and their photoelectrochemical activities for water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 12122–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xu, S.; Chen, C.; Wang, K.; Zhou, S.; Hu, F.; Wang, L.; Gao, F.; Chen, S. Heterojunction nanochannel arrays based on SiC Core-TiO2/ shell for efficiently enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 19924–19935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T.; Kato, M.; Ichimura, M.; Hatayama, T. SiC photoelectrodes for a self-driven water-splitting cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 053902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Jiang, F.; Gao, F.; Wang, L.; Teng, J.; Fu, D.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Chen, S. Single-Crystal Integrated Photoanodes Based on 4H-SiC Nanohole Arrays for Boosting Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 20469–20478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Shi, Y.; Ekeroth, S.; Keraudy, J.; Syväjärvi, M.; Yakimova, R.; Helmersson, U.; Sun, J. A nanostructured NiO/cubic SiC p-n heterojunction photoanode for enhanced solar water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 4721–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.X.; Heuser, S.; Tong, X.L.; Yang, N.J.; Guo, X.Y.; Jiang, X. Epitaxial Cubic Silicon Carbide Photocathodes for Visible-Light-Driven Water Splitting. Chemistry 2020, 26, 3586–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Yasuda, T.; Miyake, K.; Ichimura, M.; Hatayama, T. Epitaxial p-type SIC as a self-driven photocathode for water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 4845–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolasek, M.; Kemeny, M.; Chymo, F.; Ondrejka, P.; Huran, J. Amorphous silicon PEC-PV hybrid structure for photo-electrochemical water splitting. J. Electr. Eng.-Elektrotechnicky Cas. 2019, 70, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, Y.; Li, M.; Wei, W.; Huang, B. Stable Si-based pentagonal monolayers: High carrier mobilities and applications in photocatalytic water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 24055–24063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T.; Kato, M.; Ichimura, M.; Hatayama, T. Solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency of water photolysis with epitaxially grown p-type SiC. Mater. Sci. Forum 2013, 740–742, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Kaiser, B.; Jaegermann, W. Novel photoelectrochemical behaviors of p-SiC films on Si for solar water splitting. J. Power Sources 2014, 253, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Guan, S.; Zhou, B.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Melvin, G.; Ortiz-Medina, J.; Wang, M.; Ogata, H.; et al. Plasma-induced N doping and carbon vacancies in a self-supporting 3C-SiC photoanode for efficient photoelectrochemical water oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 19201–19211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Wen, W.; Wang, H.; Dimitrijev, S.; Zhang, S. Enhanced photoelectroctatlytic performance of etched 3C-SiC thin film for water splitting under visible light. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 54441–54446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Wang, W.; Han, Z.; Ivanov, I.; Liang, H.; Darakchieva, V.; Sun, J. Manipulating Electron Structure through Dual-Interface Engineering of 3C-SiC Photoanode for Enhanced Solar Water Splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 14815–14823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa, R.; Fraga, M.; Santos, L.; Massi, M.; Maciel, H. Nanostructured thin films based on TiO2 and/or SiC for use in photoelectrochemical cells: A review of the material characteristics, synthesis and recent applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 29, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Ran, G.; Zhou, W.; Ye, C.; Feng, Q.; Li, N. Investigation of Surface Morphology of 6H-SiC Irradiated with He+ and H2+ Ions. Materials 2018, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, N.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Guo, L.; Yuan, W.; Chen, X. Hexagonal SiC with spatially separated active sites on polar and nonpolar facets achieving enhanced hydrogen production from photocatalytic water reduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 4787–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Yang, C.; Rao, W. Hydrogen generation due to water splitting on Si—Terminated 4H-Sic(0001) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 2018, 668, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Yue, Q.; Tang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Du, P. A highly efficient photoelectrochemical cell using cobalt phosphide-modified nanoporous hematite photoanode for solar-driven water splitting. J. Catal. 2018, 366, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Shi, Y.; Syväjärvi, M.; Yakimova, R.; Sun, J. Cubic SiC Photoanode Coupling with Ni:FeOOH Oxygen-Evolution Cocatalyst for Sustainable Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. Sol. RRL 2020, 4, 1900364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digdaya, I.; Rodriguez, P.; Ma, M.; Adhyaksa, G.; Garnett, E.; Smets, A.; Smith, W. Engineering the kinetics and interfacial energetics of Ni/Ni-Mo catalyzed amorphous silicon carbide photocathodes in alkaline media. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 6842–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Lv, S.; Huo, L. A Simple Highly Efficient Catalyst with NiOX-loaded Reed-based SiC/CNOs for Hydrogen Production by Photocatalytic Water-splitting. Chemistryselect 2024, 9, e202303612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Liu, Z.X.; Ding, L.J.; Chen, J.J. Facile fabrication and efficient photoelectrochemical water-splitting activity of electrodeposited nickel/SiC nanowires composite electrode. Catal. Commun. 2017, 96, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, M.; Kurniawan, M.; Knauer, A.; Rumiche, F.; Bund, A.; Guerra, J. Localized surface states influence in the photoelectrocatalytic performance of Al doped a-SiC:H based photocathodes. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 143, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, T.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhu, L.; Wang, E.; Hou, X.; Chou, K.; et al. Boosting of water splitting using the chemical energy simultaneously harvested from light, kinetic energy and electrical energy using N doped 4H-SiC nanohole arrays. Nano Energy 2022, 104, 107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, X.; Ning, F.; Wang, H.; Pan, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yin, Z.; Tang, N. Au@Pt decorated polyaniline/TiO2 with synergy of p-n heterojunction and surface plasmon resonance for boosted photoelectrochemical water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Pan, Z.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, W.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Muzi, C.; Zhang, Y. Synergistic promotion of photoelectrochemical water splitting efficiency of TiO2 nanorods using metal-semiconducting nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 420, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Guo, Z.; Song, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, Z. Improved photoelectrochemical response of CuWO4/BiOI p-n heterojunction embedded with plasmonic Ag nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 370, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linic, S.; Christopher, P.; Ingram, D. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S.; Haris, M.; Ajmal, R.; Latif, H.; Abbas, Q.; Alshahrani, T.; Al-Anazy, M.; Yousef, E.; Younas, M.; Sabah, A. High system kinetics of photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting using plasmonic nanocomposites of BiVO4. Mater. Lett. 2024, 360, 135932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yae, S.; Onaka, A.; Abe, M.; Fukumuro, N.; Ogawa, S.; Yoshida, N.; Nonomura, S.; Nakato, Y.; Matsuda, H. Hydrogen production using metal nanoparticle modified silicon thin film photoelectrode. In Proceedings of the Solar Hydrogen and Nanotechnology II, San Diego, CA, USA, 28–30 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, G.; Zhao, J.; Hicks, E.; Schatz, G.; Van Duyne, R. Plasmonic properties of copper nanoparticles fabricated by nanosphere lithography. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1947–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, U.; Chavez, S.; Linic, S. Controlling energy flow in multimetallic nanostructures for plasmonic catalysis. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linic, S.; Christopher, P.; Xin, H.; Marimuthu, A. Catalytic and Photocatalytic Transformations on Metal Nanoparticles with Targeted Geometric and Plasmonic Properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Cho, H.; Jung, J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.; Yeo, J.; Han, S.; Ko, S. ZnO/CuO/M (M = Ag, Au) Hierarchical Nanostructure by Successive Photoreduction Process for Solar Hydrogen Generation. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bing, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, X. Novel Z-scheme visible-light-driven Ag3PO4/Ag/SiC photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4652–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, T.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Xu, J. Catalytic decomposition of sulfuric acid on composite oxides and Pt/SiC. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Tang, Y.; Huang, L. Plasmonic Au activates anchored Pt-Si bond in Au-Pt-SiC promoting photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 915, 165450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Pan, J.; Fu, J.; Shen, W.; Liu, H.; Cai, C.; Zhang, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y. Constructing 0D/1D/2D Z-scheme heterojunctions of Ag nanodots/SiC nanofibers/g-C3N4 nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic water splitting. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 2262–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Privitera, S.; Milazzo, R.; Bongiorno, C.; Di Franco, S.; La Via, F.; Song, X.; Shi, Y.; Lanza, M.; Lombardo, S. Photo-electrochemical water splitting in silicon based photocathodes enhanced by plasmonic/catalytic nanostructures. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. Funct. Solid-State Mater. 2017, 225, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akikusa, J.; Khan, S. Photoelectrolysis of water to hydrogen in p-SiC/Pt and p-SiC/n-TiO2 cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2002, 27, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, A.; Kudo, A.; Numata, Y.; Ikegami, M.; Miyasaka, T.; Ichikawa, N.; Kato, M.; Hashimoto, H.; Inoue, H.; Ishitani, O.; et al. Solar Water Splitting Utilizing a SiC Photocathode, a BiVO4 Photoanode, and a Perovskite Solar Cell. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4420–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Longden, T.; Catchpole, K.; Beck, F. Comparative techno-economic analysis of different PV-assisted direct solar hydrogen generation systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4486–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Sinaga, L.; Schwarze, M.; Schomäcker, R.; van de Krol, R.; Abdi, F. Techno-Economic Assessment of Sustainable H2 Production and Hydrogenation of Chemicals in a Coupled Photoelectrochemical Device. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 13783–13797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattry, A.; Johnson, H.; Chatzikiriakou, D.; Haussener, S. Probabilistic Techno-Economic Assessment of Medium-Scale Photoelectrochemical Fuel Generation Plants. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 12058–12077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, J.; Gemechu, E.; Kumar, A. The development of techno-economic assessment models for hydrogen production via photocatalytic water splitting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 279, 116750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, B.; Can, E.; Yildirim, R. Analysis of photoelectrochemical water splitting using machine learning. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 19633–19654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOE H2A Analysis. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/program-areas/systems-analysis/h2a-analysis (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Grimm, A.; de Jong, W.; Kramer, G. Renewable hydrogen production: A techno-economic comparison of photoelectrochemical cells and photovoltaic-electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 22545–22555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidewind, J. How Much Technological Progress is Needed to Make Solar Hydrogen Cost-Competitive? Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, A.; Dias, P.; Lopes, T.; Mendes, A. The route for commercial photoelectrochemical water splitting: A review of large-area devices and key upscaling challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2388–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butson, J.; Sharma, A.; Tournet, J.; Wang, Y.; Tatavarti, R.; Zhao, C.; Jagadish, C.; Tan, H.; Karuturi, S. Unlocking Ultra-High Performance in Immersed Solar Water Splitting with Optimised Energetics. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dihan, M.; Rahman, T.; Khan, M.; Banhi, T.; Sadaf, S.; Reza, M.; Afroze, S.; Islam, S.; Islam, M. Photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical H2 generation for sustainable future: Performance improvement, techno-economic analysis, and life cycle assessment for shaping the reality. Fuel 2025, 392, 134356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Krol, R. A Faster Path to Solar Water Splitting. Matter 2020, 3, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | Electrode Material/Type/Band Gap | Light Source/Electrolyte | Bias | Photocurrent Density | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2SO4 electrolyte | |||||

| 1 | 6H–SiC and 3C–SiC s/n-type/6H–SiC has a band gap of 3.0 eV, and 3C–SiC has a band gap of 2.3 eV | Monochromatic light of 410 nm wavelength (30 mW cm−2)/0.5 M Na2SO4 solution at pH 6.8 | Onset potential of 0 V vs. RHE for the Si-face, and photocurrent measurements reaching a maximum at 0.4 V | The Si-face of 6H–SiC produced a photocurrent density of 1.01 mA/cm2 at 0.4 V | [77] |

| 2 | 4H-SiC nanohole arrays/n-type 4H-SiC/2.61 eV | AM1.5G (100 mW/cm2)/0.5 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution (pH ~6.8) | 1.23 V vs. RHE | 3.20 mA/cm2 | [79] |

| 3 | SiC core–TiO2 shell nanoarrays/type-II heterojunction/2.3–3.2 eV | 100 mW/cm2/1 M Na2SO4 solution buffered to pH 6.8 | 1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl | 3.62 mA/cm2 | [80] |

| 4 | 4H-SiC nanohole arrays integrated onto a SiC wafer substrate/n-type 4H-SiC/2.61 eV for the SiC nanohole arrays, 2.65 eV for the original 4H-SiC | 350 W Xe, AM 1.5 G, 100 mW/cm2/ 0.5 M Na2SO4 aqueous solution (pH 6.8) | 0.016 V vs. RHE 1.23 V RHE | 3.20 mA/cm2 at 1.23 V vs. RHE | [81] |

| 5 | SiC@g-C3N4 core–shell NW/n-type/3C-SiC—2.4 eV, g-C3N4—2.6 eV | 300 W Xe (includes UV and visible light)/0.1 M Na2SO4 solution | −0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl | −0.62 mA cm−2 at −0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl | [75] |

| 6 | 3C-SiC/n-type/2.36 eV | AM1.5G (100 mW/cm2)/1 M NaOH solution | 0 V vs. RHE | 10 mA/cm2 | [76] |

| 7 | Nanoporous 3C-SiC photoanodes/n-type/2.36 eV | AM 1.5G 100 mW/cm2/1.0 M NaOH solution | 1.23 V vs. RHE | 2.30 mA/cm2 | [66] |

| 8 | 3C-SiC/n-type/2.36 eV (cubic SiC) | AM 1.5G (100 mW/cm2)/1.0 M NaOH solution | 0 V vs. RHE (onset potential ~0.40 V RHE) | 0.5 mA/cm2 at 1.0 V RHE (for NiO/3C-SiC) | [83] |

| 9 | Epitaxial 3C-SiC/p-type/2.5 eV | A 150 W Xe lamp with a UV filter (λ > 420 nm)/0.5 M H2SO4 | 1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl | 20 mA/cm2 | [84] |

| 10 | Epitaxially grown 4H-, 6H-, and 3C-SiC/p-type/2.3 eV (3C-SiC), 2.9 eV (6H-SiC), 3.2 eV (4H-SiC) | 1 W/cm2/1 M H2SO4 | Self-driven | 3C-SiC 20 mA/cm2 | [85] |

| 11 | a-SiC based/from 2.0 eV (PEC1) to 1.7 eV (PEC3) | AM 1.5 spectrum, 1000 W/m2/1 M H2SO4 with pH 3 | 0 V vs. RHE for PEC3 | 50 µA/cm2 | [86] |

| 12 | SnO2/SiC nanowire/n-type/SiC 2.4 eV, SnO2 3.6 eV | A 300 W Xe/1.0 M H2SO4 | 0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl | 62.0 mA/cm2, 6.9 times higher than pristine SiC NW | [74] |

| SiC Polytype | Bandgap (eV) | Carrier Concentration (cm−3) | Carrier Mobility (cm2V−1s−1) | Typical Photocurrent Density (mA cm−2) | Optimal Electrolyte (pH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3C-SiC | 2.08–2.38 | 1 × 1017–1 × 1018 | 800–1000 | 1.5–2.5 | Neutral or weakly alkaline |

| 4H-SiC | 3.26 | 1 × 1016–1 × 1017 | 900–1200 | 2.0–3.2 | Alkaline (pH ≈ 13) |

| 6H-SiC | 3.02 | 5 × 1015–1 × 1017 | 500–700 | 1.0–2.0 | Neutral |

| 15R-SiC (α-SiC) | 3.10 | 1 × 1016–1 × 1018 | 400–600 | 1.0–1.8 | Neutral to weakly alkaline |

| p-SiC (pentagonal) | 2.35 | ~1 × 1017 | up to 2500 | 2.5–4.0 | Neutral (pH ≈ 7) |

| a-SiC (amorphous) | 1.4–2.0 | 1 × 1018–1 × 1020 | 10–50 | 0.3–1.0 | Acidic (pH ≈ 4–6) |

| № | Electrode Material/Type/Band Gap | Light Source/Electrolyte | Bias | Photocurrent Density | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SiC WR with Ni NP/2.36 eV | 300 W Xe/1 M KOH aqueous solution | 1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl | −32.4 mA/cm2, significantly higher compared to pristine SiC NW (−3 mA/cm2) | [101] |

| 2 | a-SiC, Ni/Ni-Mo catalysts/2 eV | AM1.5 450W Xe (100 mW/cm2)/1 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution (pH 14) | 0 V vs. RHE | −14 mA/cm2 | [99] |

| 3 | (a-SiC(Al))/p-type | AM 1.5 at 1000 W/m2/1 mol/L sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution with pH 0 | −2 V | −17 mA/cm2 at −1.75 V for the 600 °C annealed sample, while the 700 °C sample achieved about −1 mA/cm2 | [102] |

| 4 | Nanostructured NiO and 3C-SiC/p–n heterojunction/ 3C-SiC 2.36 eV, NiO 3.52 eV | AM1.5G, 100 mW/cm2/1.0 M NaOH solution | 0.55 V RHE, with onset potential at 0.20 VRHE | 1.01 mA/cm2 at 0.55 VRHE /IPCE 31% under 410 nm LEDs at 1.0 mW/cm2 | [82] |

| 5 | Nanoporous 6H-silicon carbide (6H-SiC) with a conformal coating of Ni-FeOOH nanorods as a water oxidation cocatalyst/n-type/3.02 eV | AM1.5G illumination at 100 mW/cm2/1.0 M NaOH solution | 1 V_RHE | 0.684 mA/cm2/IPCE 25% at 410 nm and 12% at 450 nm | [65] |

| 6 | N-doped 4H-SiC/n-type/1.416 eV | 300 W Xe lamp with an AM1.5, 100 mW/cm2 | 1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl | 6.50 mA/cm2 at 1.4 V (vs Ag/AgCl), 50.1% enhancement over non-piezoelectric conditions | [103] |

| 7 | Nanoporous 3C-SiC photoanode + Ni:FeOOH OER cocatalyst/Transition-metal oxyhydroxide/2.36 eV | AM 1.5G (100 mW cm−2)/1.0 M NaOH | 1.23 V vs. RHE | 2.30 mA cm−2 | [66] |

| 8 | Nanoporous 6H-SiC photoanode + Ni–FeOOH coating/Transition-metal oxyhydroxide/3.0–3.2 eV | AM 1.5G (100 mW cm−2)/alkaline | Onset ≈ 0 V vs. RHE 1.0 V vs. RHE | 0.684 mA cm−2 @1.0 V vs. RHE | [65] |

| 9 | 3C-SiC photoanode with Ni(OH)2/Co3O Conversely, acidic environments dual-interface modifier/Transition-metal hydroxide and oxide | AM 1.5G/alkaline | 1.23 V vs. RHE | 1.68 mA cm−2 | [92] |

| № | Electrode Material/Type/Band Gap | Light Source/Electrolyte | Bias | Photocurrent Density | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | n-type 3C-SiC with Au or Pt nanoparticles deposited on the surfaces/2.3 eV | AM 1.5G (1 kW/m2)/1 M KOH | Reduced from −1.64 V vs. SCE to −1.40 V and −0.76 V after incorporation Au and Pt, respectively | 38 mA/cm2 with Pt | [118] |

| 2 | Au nanoparticles (NPs) decorated on SiC NW/3C-SiC having a bandgap of 2.3 eV and 6H-SiC having a bandgap of 3.3 eV | 300 W Xe/0.5 M Na2SO4 | 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl | The apparent quantum efficiency 2.12% at 365 nm | [77] |

| 3 | p-SiC with Pt metal islets/3.0 eV | 50 mW/cm2 Xe/0.5 M H2SO4 | 0.135 mA/cm2 was obtained for the p-SiC/Pt system. The self-driven p-SiC/n-TiO2 system showed a maximum photocurrent density of 0.05 mA/cm2 | [119] | |

| 4 | Pt-loaded SiC photocathode/2.4–2.5 eV | AM 1.5G/borate buffer solution (pH 9.1) | −0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl | 0.62 mA cm−2 | [120] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakranova, D.; Serikkanov, A.; Kapsalamova, F.; Rakhimzhanov, M.; Mukash, Z.; Bakranov, N. Recent Advances and Techno-Economic Prospects of Silicon Carbide-Based Photoelectrodes for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Generation. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121159

Bakranova D, Serikkanov A, Kapsalamova F, Rakhimzhanov M, Mukash Z, Bakranov N. Recent Advances and Techno-Economic Prospects of Silicon Carbide-Based Photoelectrodes for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Generation. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121159

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakranova, Dina, Abay Serikkanov, Farida Kapsalamova, Murat Rakhimzhanov, Zhanar Mukash, and Nurlan Bakranov. 2025. "Recent Advances and Techno-Economic Prospects of Silicon Carbide-Based Photoelectrodes for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Generation" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121159

APA StyleBakranova, D., Serikkanov, A., Kapsalamova, F., Rakhimzhanov, M., Mukash, Z., & Bakranov, N. (2025). Recent Advances and Techno-Economic Prospects of Silicon Carbide-Based Photoelectrodes for Solar-Driven Hydrogen Generation. Catalysts, 15(12), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121159