Performance and Mechanism of Fe80P13C7 Metal Glass in Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Degradation Properties of Fe80P13C7 MG

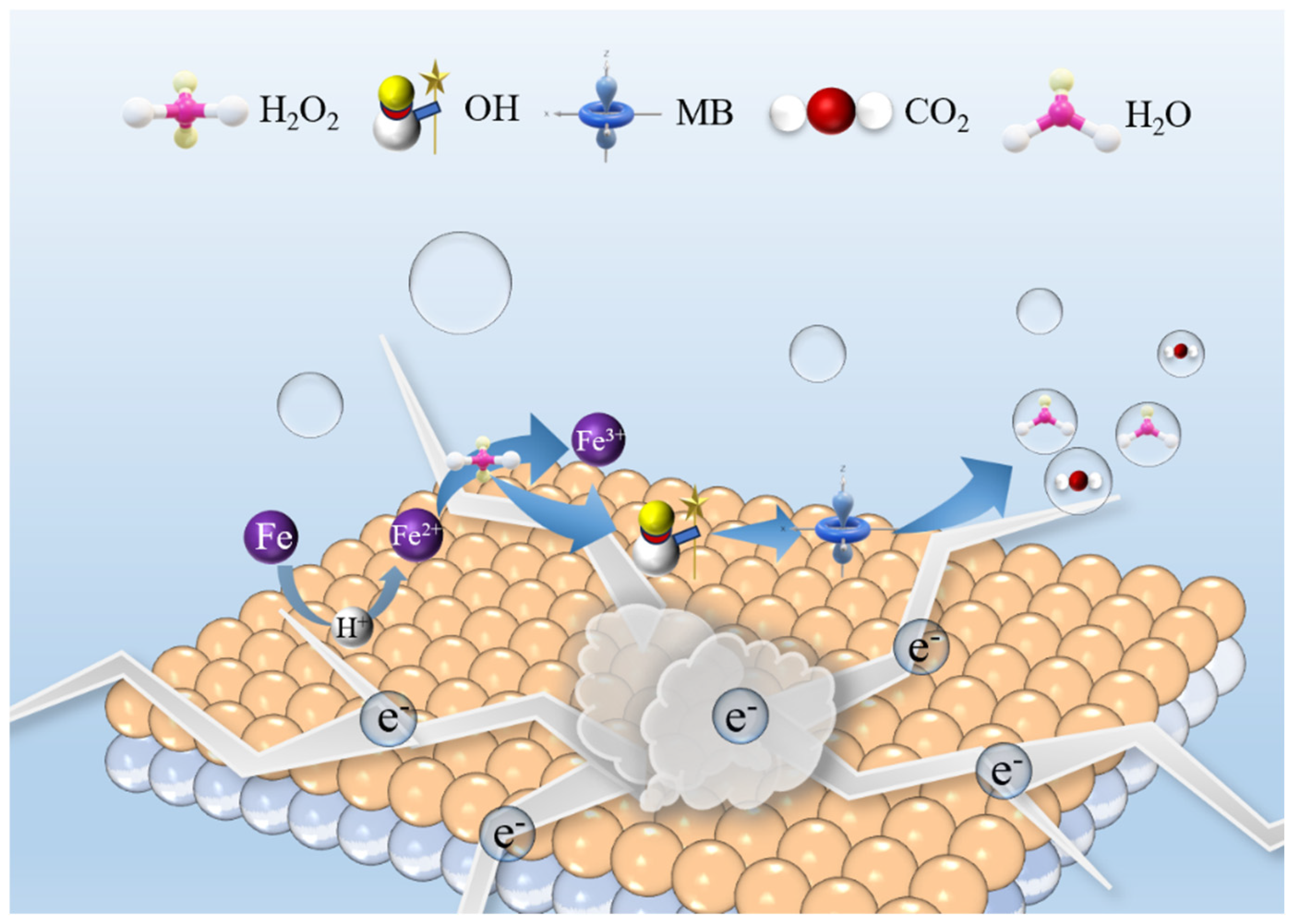

2.2. Mechanism Analysis of Fe80P13C7 Catalytic Degradation of MB

2.3. Limitations and Future Perspectives

3. Experimental Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of Fe80P13C7 MG

3.2. Degradation Experiment

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Fe80P13C7 exhibits excellent and stable catalytic performance in Fenton-like reactions. Its degradation rate not only surpasses that of FeSiB MG and commercial ZVI powder in benchmark experiments but also demonstrates significant advantages when compared with catalysts reported in recent literature, highlighting its potential as an efficient catalyst.

- (2)

- Fe80P13C7 possesses outstanding cyclic stability; after ten consecutive degradation cycles, its efficiency remains above 90% of the initial value. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis reveals that this stability is attributed to a unique surface “self-renewal” behavior. Specifically, cracks and corrosion features formed during the reaction effectively shed the passivation layer from the surface, continuously exposing high-activity fresh interfaces.

- (3)

- Mechanistic analysis establishes that the reaction is predominantly governed by a closed cycle involving Fe2+/Fe3+ species within the material itself. This cycle ensures continuous activation of H2O2 and generates a substantial amount of •OH radicals, thereby driving rapid and complete mineralization of pollutants.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Cheng, S.; Cao, N.; Geng, C.; He, C.; Shi, Q.; Xu, C.; Ni, J.; DuChanois, R.M.; Elimelech, M.; et al. Actinia-like multifunctional nanocoagulant for single-step removal of water contaminants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, V.; Karthika, T.S.; Mansiya, C.; Alagar, M. An over review on recently developed techniques, mechanisms and intermediate involved in the advanced azo dye degradation for industrial applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1224, 129195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.C.; Jia, Z.; Lyu, F.; Liang, S.X.; Lu, J. A review of catalytic performance of metallic glasses in wastewater treatment: Recent progress and prospects. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 105, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.J.; Jia, D.X.; Yang, M.; Yu, Y.; Lin, G.C.; Zhang, X.L. A Detailed Insight into the Effects of Morphologies of Cerium Oxide on Fenton-like Reactions for Different Applications. ChemPhysChem 2023, 24, e202300211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Xu, W.; Dong, C.; Bai, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Y. Metal sulfides as excellent co-catalysts for H2O2 decomposition in advanced oxidation processes. Chem 2018, 4, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Liu, H. The use of zero-valent iron for groundwater remediation and wastewater treatment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 267, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qian, J.; Yu, A.; Pan, B. Singlet oxygen mediated iron-based fenton-like catalysis under nanoconfinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6659–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Liang, S.X.; Xi, X.W.; Jia, Z.; Xie, S.K.; Lin, H.C.; Hu, J.P.; Zhang, L.C. Excellent performance of Fe78Si9B13 metallic glass for activating peroxymonosulfate in degradation of naphthol green B. Metals 2017, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Lin, H.; Zhang, L. Ultrafast activation efficiency of three peroxides by Fe78Si9B13 metallic glass under photo-enhanced catalytic oxidation: A comparative study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 221, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liang, S.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, L. Chemically dealloyed Fe-based metallic glass with void channels-like architecture for highly enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation in catalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 785, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.C.; Wu, G.; Luan, J.H.; Jiao, Z.B.; Wang, A.; Liang, S.X.; et al. Attractive in situ self-reconstructed hierarchical gradient structure of metallic glass for high efficiency and remarkable stability in catalytic performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, W. Effects of Ni substitution for Fe on magnetic properties of Fe80− xNixP13C7 (x = 0–30) glassy ribbons. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 463, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Wang, Q.; Di, S.; Yun, L.; Zhou, J.; Shen, B. Enhanced dye degradation capability and reusability of Fe-based amorphous ribbons by surface activation. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 53, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassoued, A.; Li, J. Preparation, characterization and application of Fe72Cu1Co5Si9B13 metallic glass catalyst in degradation of azo dyes. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 21727–21741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Chen, Q.; Ji, L.; Peng, X.; Huang, G. Synergistic effect of various elements in Fe41Co7Cr15Mo14C15B6Y2 amorphous alloy hollow ball on catalytic degradation of methylene blue. J. Rare Earths 2022, 40, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.A.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, T.; Pan, Y. Heterogeneously structured FeCuBP amorphous–nanocrystalline alloy with excellent dye degradation efficiency. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xiao, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, D.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Aierken, A.; Chen, X.; Gao, C.; et al. Design and optimization of diatomic catalysts with synergistic effects for enhanced OER and ORR performance: Insights from a TM1TM2N8@BPN electrocatalyst. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1031, 180961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Weng, Z.; Ren, D.; Tong, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, R.; Shi, H. Dualatom catalysts beyond single-atom limitations: Mn/Co synergistic sites on crystalline g-C3N4 boosting photocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1030, 180874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Herzing, A.A.; Li, X.Q.; Kiely, C.J.; Zhang, W.X. Structural evolution of pd-doped nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) in aqueous media and implications for particle aging and reactivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4288–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F. Biomimetic degradation of perfluorinated acids by vitamin B12 with nano-zero-valent iron/nickel bimetal: Effects of their self-structure and coexisting substances. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Vargas, H.O.; Rodriguez, O.G.; Qiu, S.; Yang, J.; Lefebvre, O. The synergistic effect of nickel-iron-foam and tripolyphosphate for enhancing the electrofenton process at circum-neutral pH. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Xiao, B.; Feng, L.R.; Zhou, S.S.; Chen, Z.G.; Liu, C.B.; Chen, F.; Wu, Z.Y.; Xu, N.; Oh, W.C.; et al. Graphene oxide enhances the fenton-like photocatalytic activity of nickel ferrite for degradation of dyes under visible light irradiation. Carbon 2013, 64, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaner, M.B.; Hilton, S.T. Recent advances in 3D printing for continuous flow chemistry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2024, 47, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dory, H.; Petit, E.; El-Sayegh, S.; Badouric, L.; Castro, V.; Bechelany, M.; Voiry, D.; Miele, P.; Lajaunie, L.; Salameh, C. Monolith Catalyst Design by Combining 3D Printing and Atomic Layer Deposition: Toward Green Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 24, 202401546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Arwish, S.; Rensonnet, A.; Elamin, K.; Abdurrokhman, I.; Wojnarowska, Z.; Rosenwinkel, M.; Malherbe, C.; Schoenhoff, M.; Zehbe, K.; et al. 3D Printable Polymer Electrolytes for Ionic Conduction based on Protic Ionic Liquids. ChenPhysChem 2025, 26, 202400849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Xue, L.; Liu, H.; Zhou, J.; Mo, J.; Shen, B. A novel thermal-tuning Fe-based amorphous alloy for automatically recycled methylene blue degradation. Mater. Des. 2019, 161, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wang, Q.; Fan, X.; Miao, F.; Yang, W.; Shen, B. Effect of Co addition on catalytic activity of FePCCu amorphous alloy for methylene blue degradation. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 6126–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Peng, S.; Zhou, S.; Zeng, D. Excellent degradation performance of the Fe78Si11B9P2 metallic glass in azo dye treatment. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 145, 109546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, R.; Zong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. Enhanced degradation of azo dye by nanoporous-copper-decorated Mg–Cu–Y metallic glass powder through dealloying pretreatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 305, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qin, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Li, H.; Fu, H.; Zhang, H. Cu-based metallic glass with robust activity and sustainability for wastewater treatment. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 10855–10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, X.; Zou, L.; Yao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Shen, Q.; Lavernia, E.J.; Zhang, L. Fabrication and mechanical behavior of bulk nanoporous Cu via chemical de-alloying of Cu–Al alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 660, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, Q.; Duan, D.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Amorphous NiB alloy decorated by Cu as the anode catalyst for a direct borohydride fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 10971–10981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Wu, H.; Song, G.; Jing, J.; Meng, N.; Wang, W. High-efficiency degradation of carbamazepine by the synergistic electro-activation and bimetals (FeCo@NC) catalytic-activation of peroxymonosulfate. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 338, 123064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. Degradation of cephalosporin C using MOF-derived Fe-Co bimetal in carbon cages as electro-fenton catalyst at natural pH. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 323, 124388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfatah, A.M.; Fawzy, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; El Khouly, M.E. Green synthesis of nano-zero-valent iron using ricinus communis seeds extract: Characterization and application in the treatment of methylene blue-polluted water. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25397–25411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Ding, J.; Guo, K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Bao, Z.; He, Y.; Ren, Q. CoNi alloy nanoparticles embedded in metalorganic framework-derived carbon for the highly efficient separation of xenon and krypton via a charge-transfer effect. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Yan, Y.; Lai, S.; He, J.; Liu, Z.; Gao, B.; Javanbakht, M.; Peng, X.; Chu, P.K. Ni3+-enriched nickel-based electrocatalysts for superior electrocatalytic water oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qiu, L.; Zhu, Q.; Liang, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, J.; Shen, J. Insight into efficient degradation of 3,5-dichlorosalicylic acid by Fe-Si-B amorphous ribbon under neutral condition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 294, 120258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, M.; Shao, L.; Ge, Y.; Lin, P.; Chu, C.; Shen, B. Effects of structural relaxation on thedye degradation ability of FePC amorphous alloys. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 525, 119671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qi, Z.G.; Feng, Y.; Liu, H.Z.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, L.C.; Wang, W.M. Insight into fast catalytic degradation of neutral reactive red 195 solution by FePC glassy alloy: Fe release and OH generation. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 364, 120058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Ge, C.; Zhang, Y. B-all milling-assisted preparation of N-doped biochar loaded with ferrous sulfide as persulfate activator for phenol degradation: Multiple active sites-triggered radical/non-radical mechanism. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 316, 121639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Yan, W.-Y.; Yu, H.-B.; Liu, L. Three-Dimensional Hierarchical Porous Structures of Metallic Glass/Copper Composite Catalysts by 3D Printing for Efficient Wastewater Treatments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 7227–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, S.X.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.C. Fe-Based Metallic Glasses and Dyes in Fenton-Like Processes: Understanding Their Intrinsic Correlation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Yi, S.; Choi, J. Excellent dye degradation performance of FeSiBP amorphous alloys by Fenton-like process. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 105, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.C.; Ma, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, W. High MB Solution Degradation Efficiency of FeSiBZr Amorphous Ribbon with Surface Tunnels. Materials 2020, 13, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Zhang, K.; Guo, F.; Kuang, T. Performance and Mechanism of Fe80P13C7 Metal Glass in Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121158

Ma L, Zhang K, Guo F, Kuang T. Performance and Mechanism of Fe80P13C7 Metal Glass in Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121158

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Li, Kun Zhang, Feilong Guo, and Tiejun Kuang. 2025. "Performance and Mechanism of Fe80P13C7 Metal Glass in Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121158

APA StyleMa, L., Zhang, K., Guo, F., & Kuang, T. (2025). Performance and Mechanism of Fe80P13C7 Metal Glass in Catalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Catalysts, 15(12), 1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121158