Methanol Oxidation over Pd-Doped Co- and/or Ag-Based Catalysts: Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO)

Abstract

1. Introduction

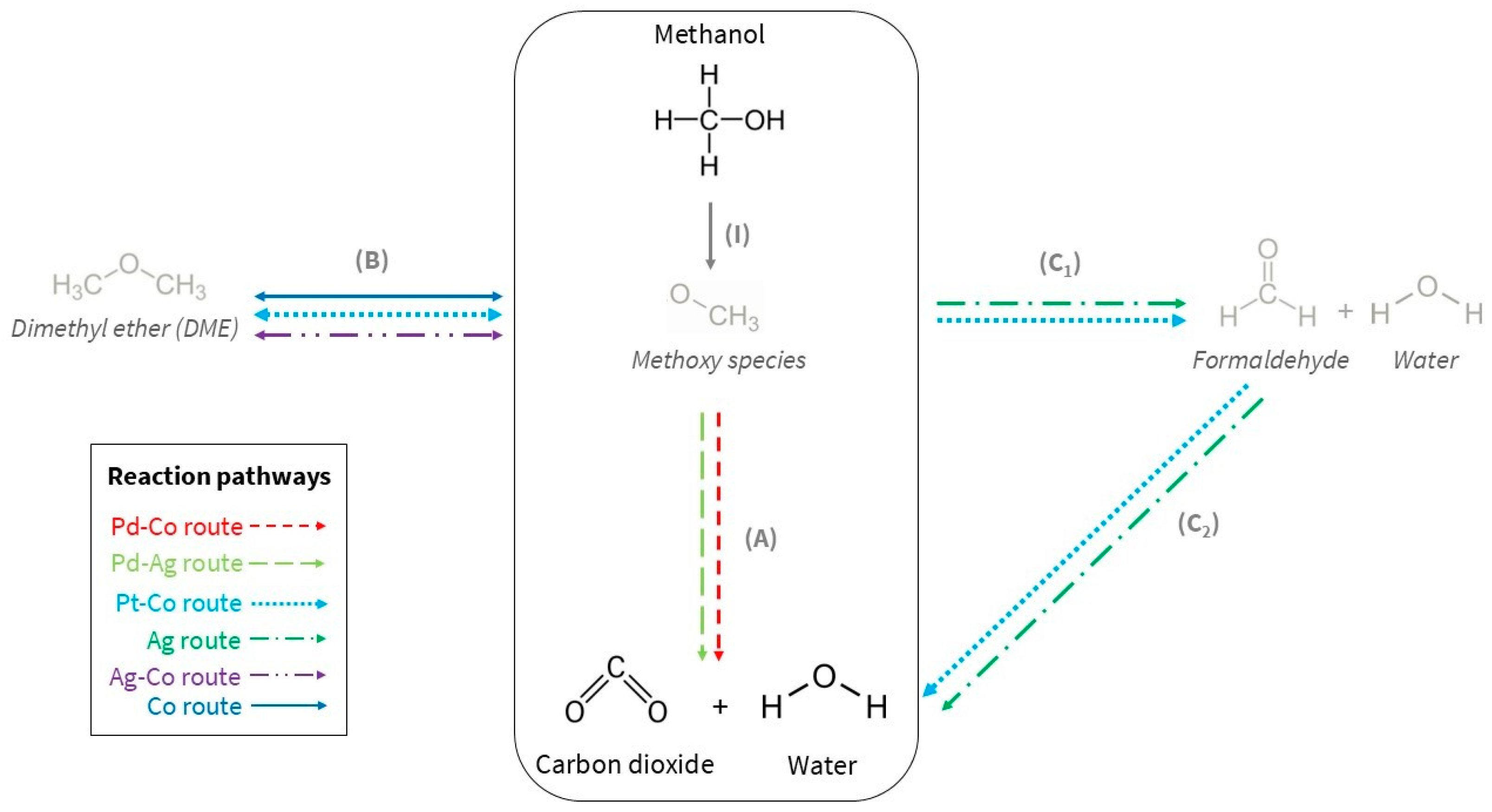

2. Results

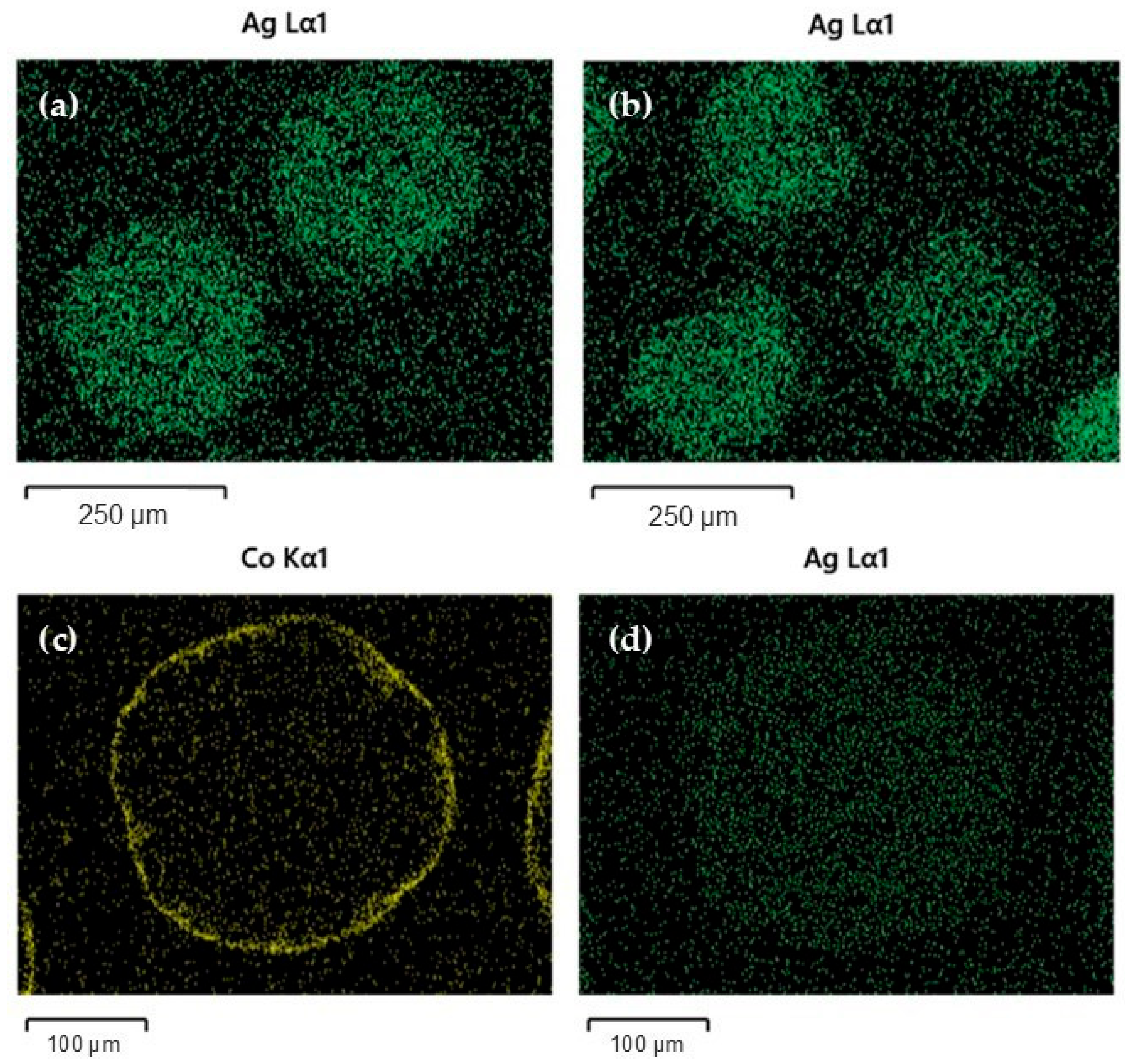

2.1. Textural and Structural Properties of Fresh Catalysts

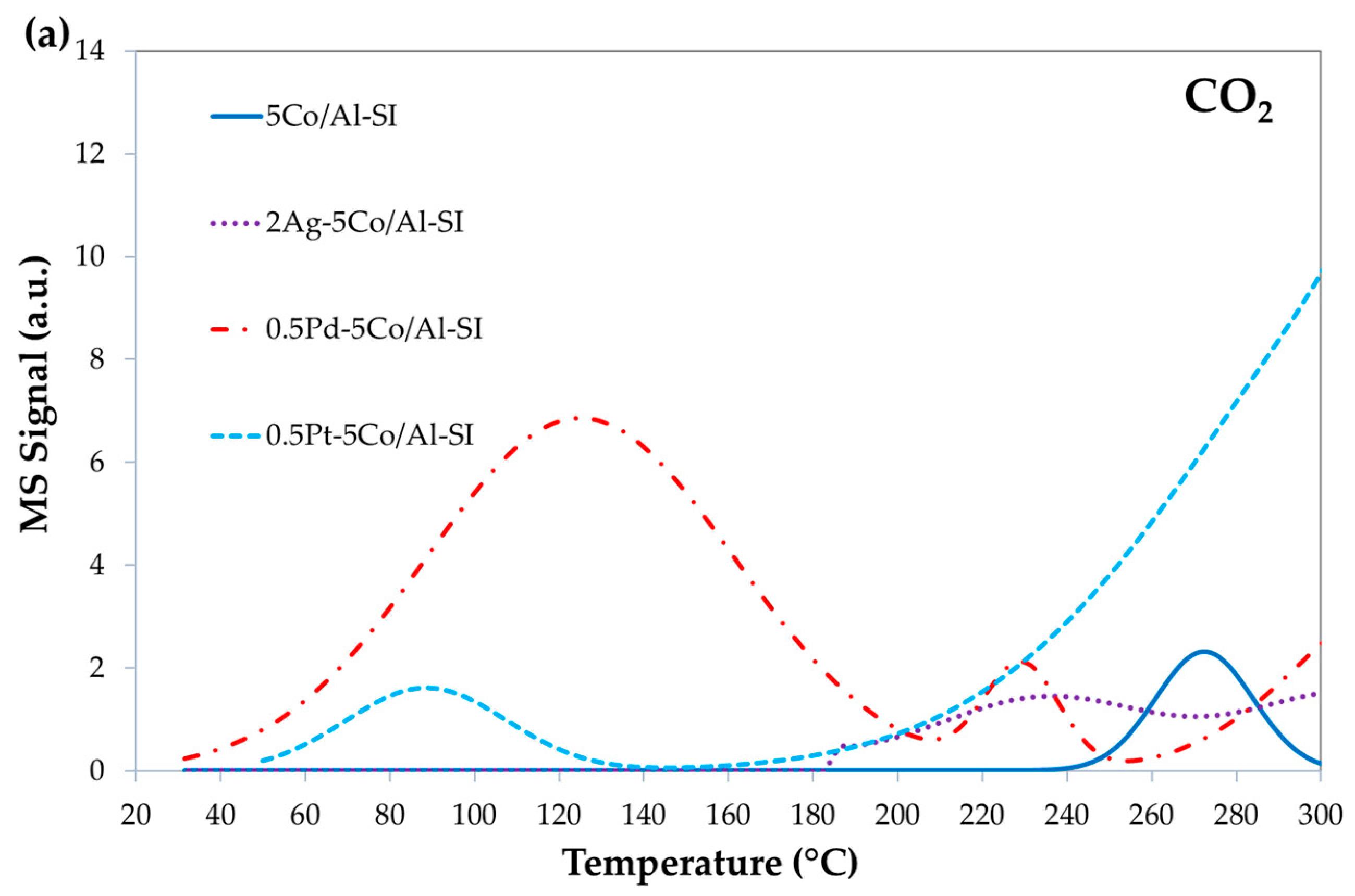

2.2. Reducibility of Fresh Catalysts

2.3. Methanol Oxidation Reaction

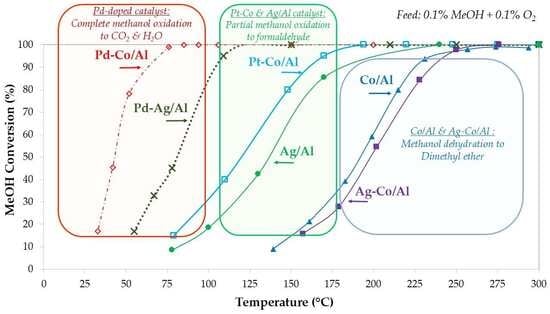

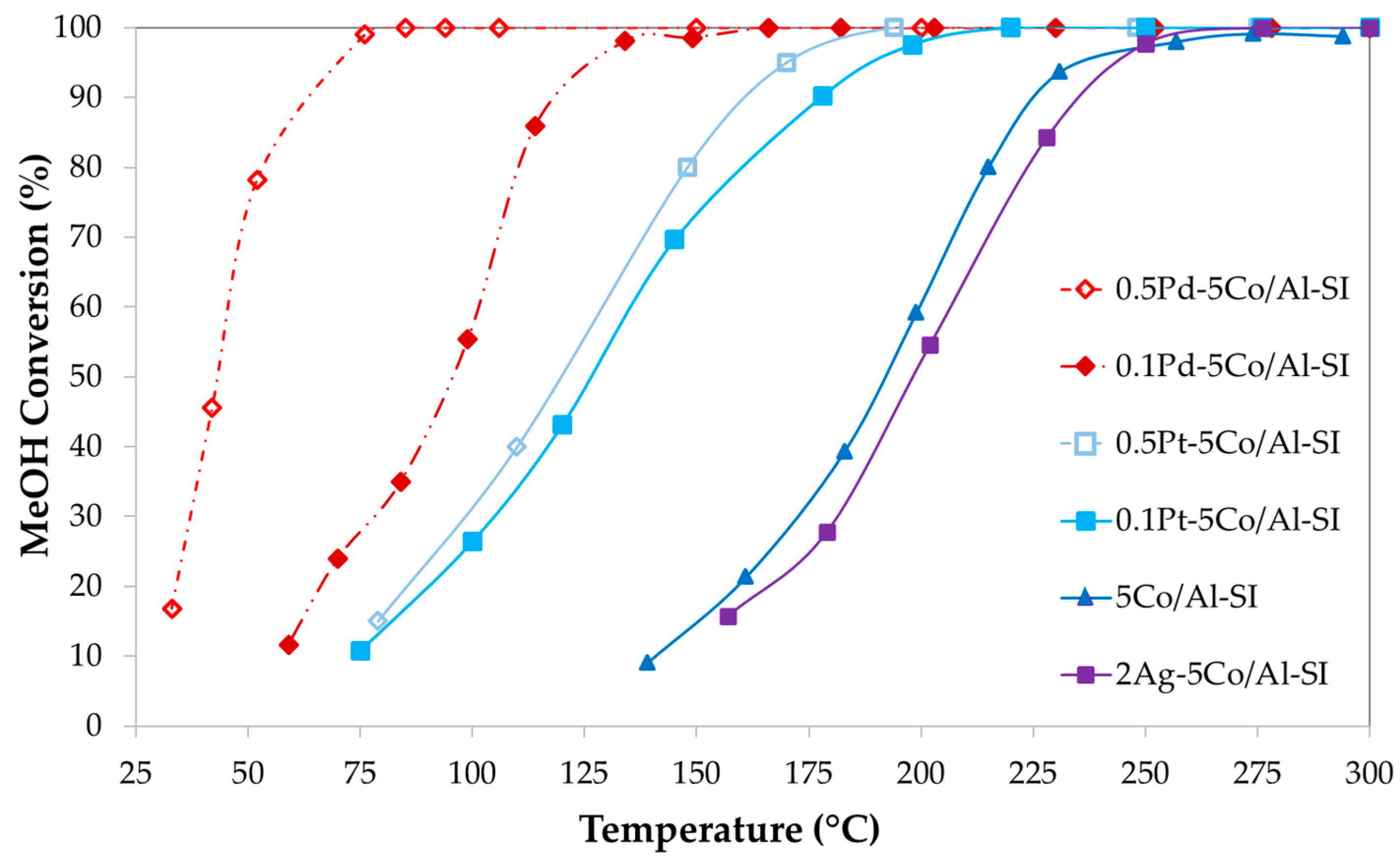

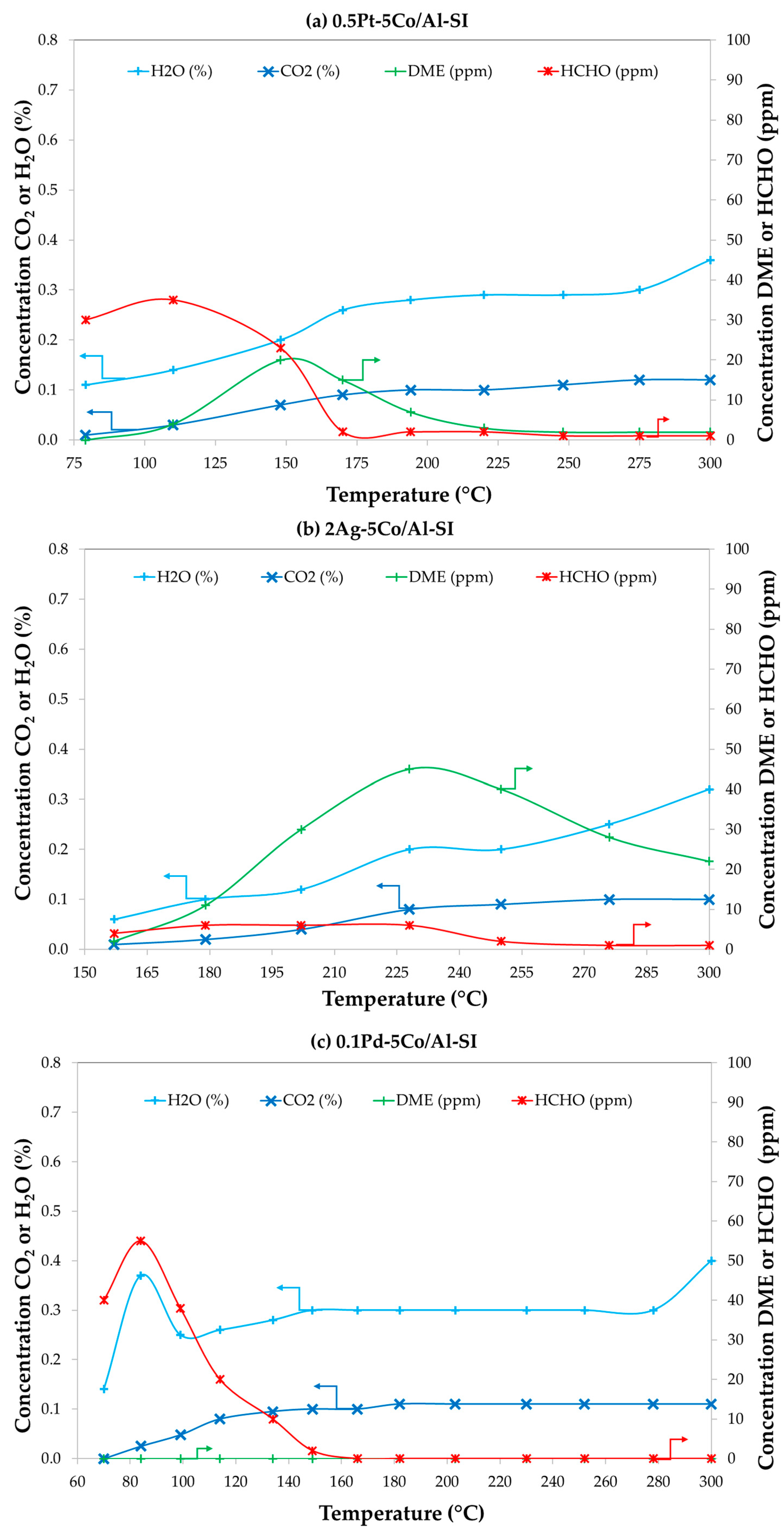

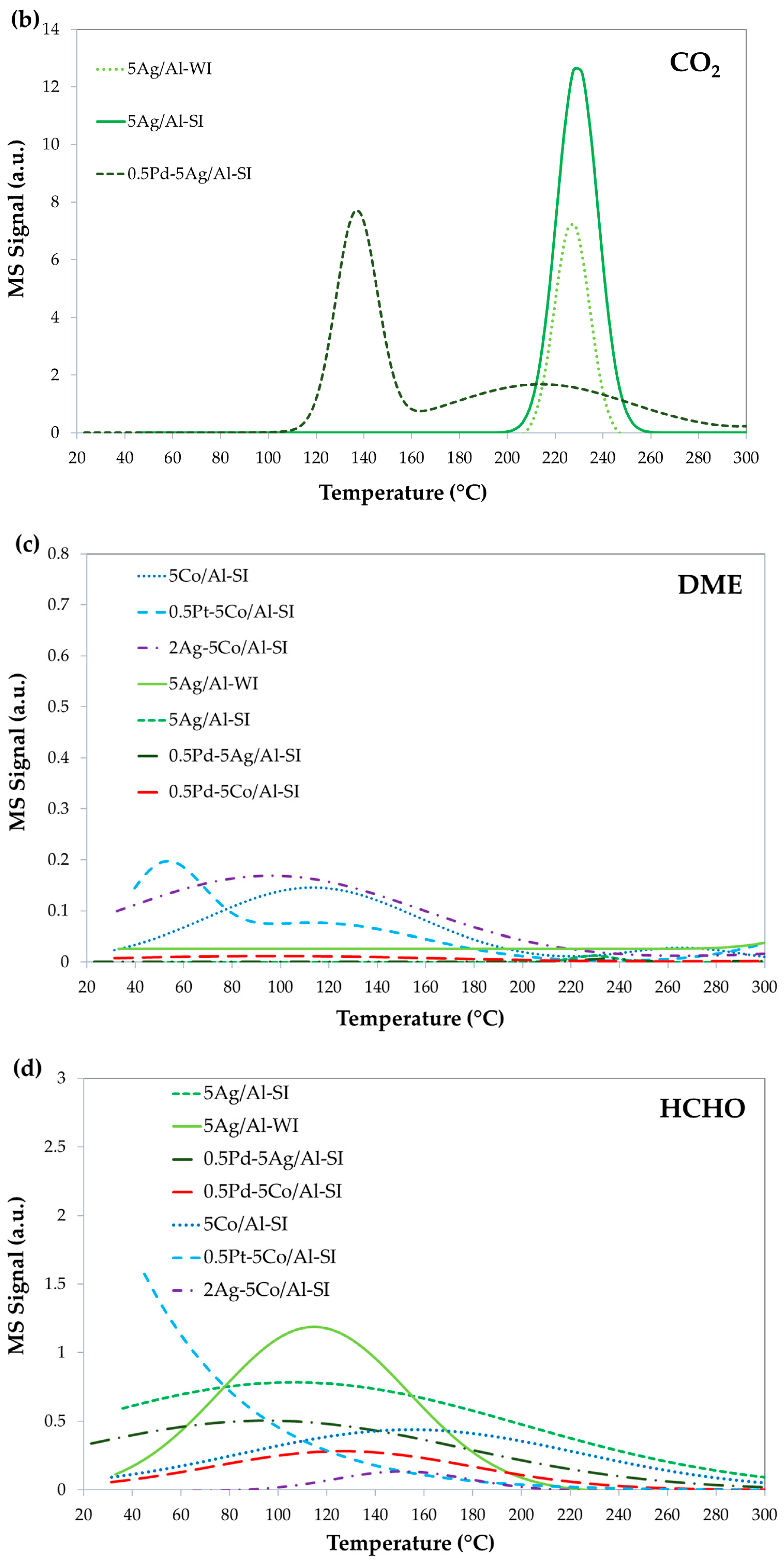

2.3.1. Effect of Noble and Transition Metals on Co-Based Catalysts

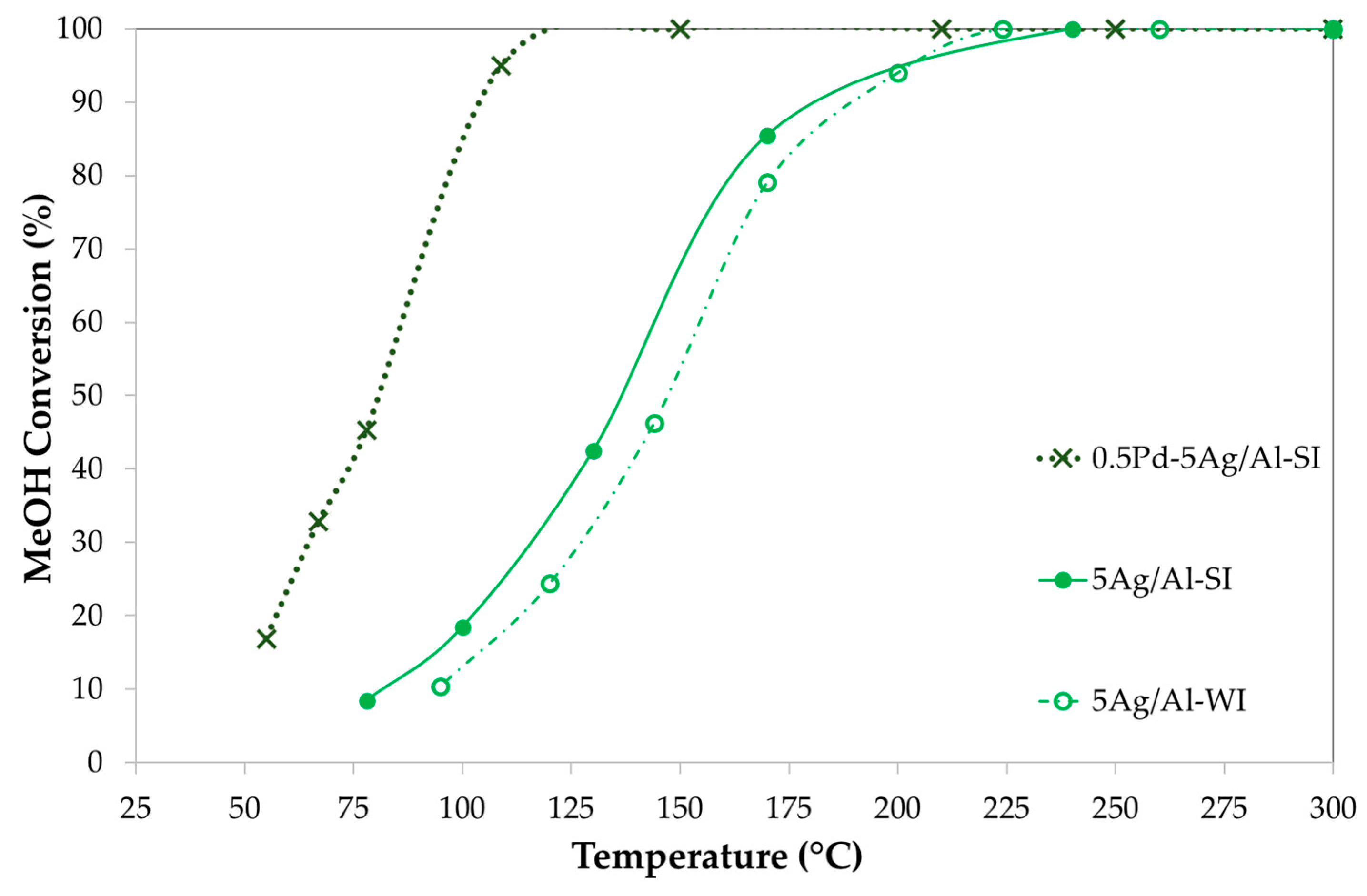

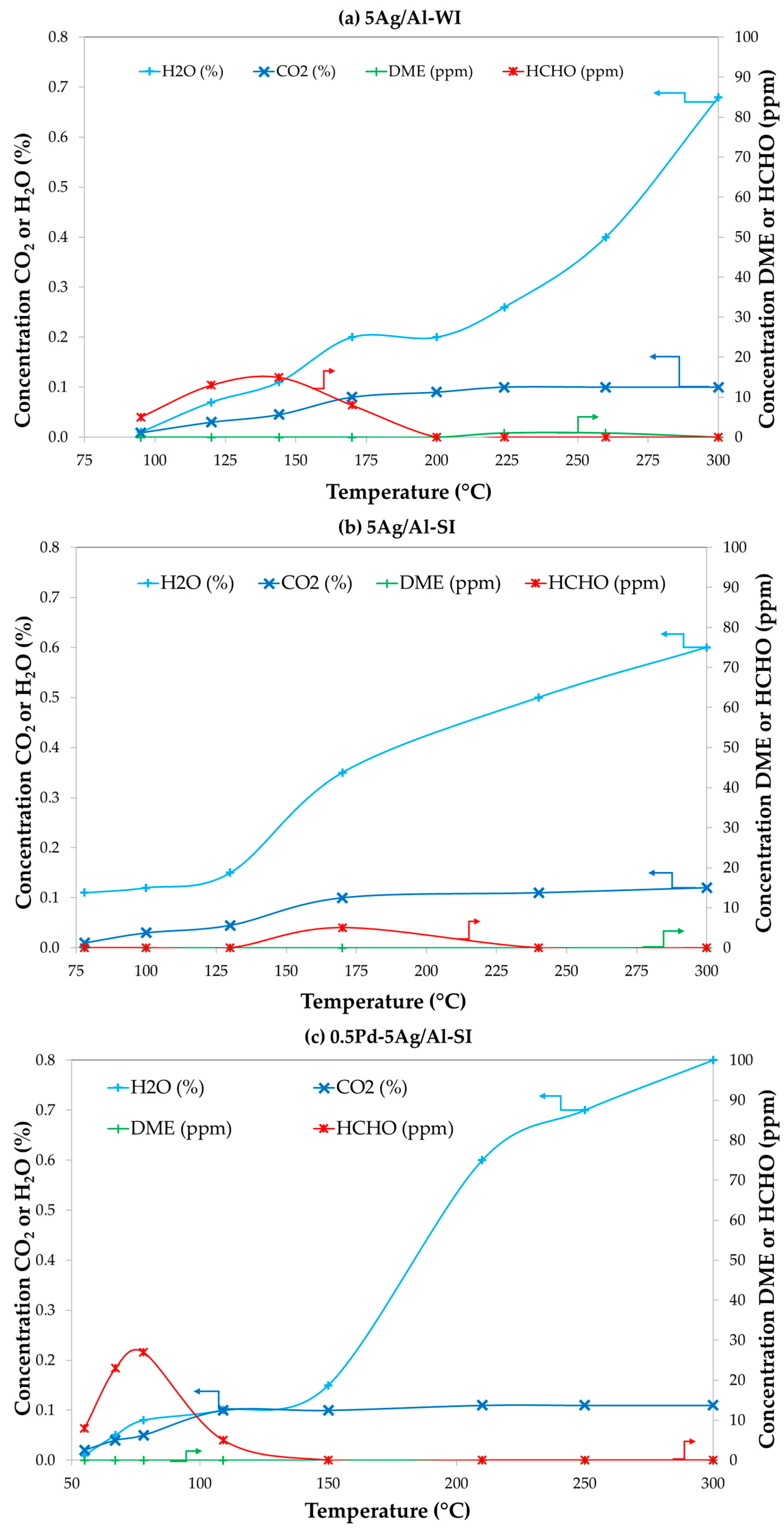

2.3.2. Effect of Synthesis Method and Pd-Doping on Ag-Based Catalysts

2.4. Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO) and Catalysts Stability with Time-on-Stream

2.4.1. Effect of CO and/or H2O on Optimum 0.5Pd-5Co/Al-SI Catalyst Activity

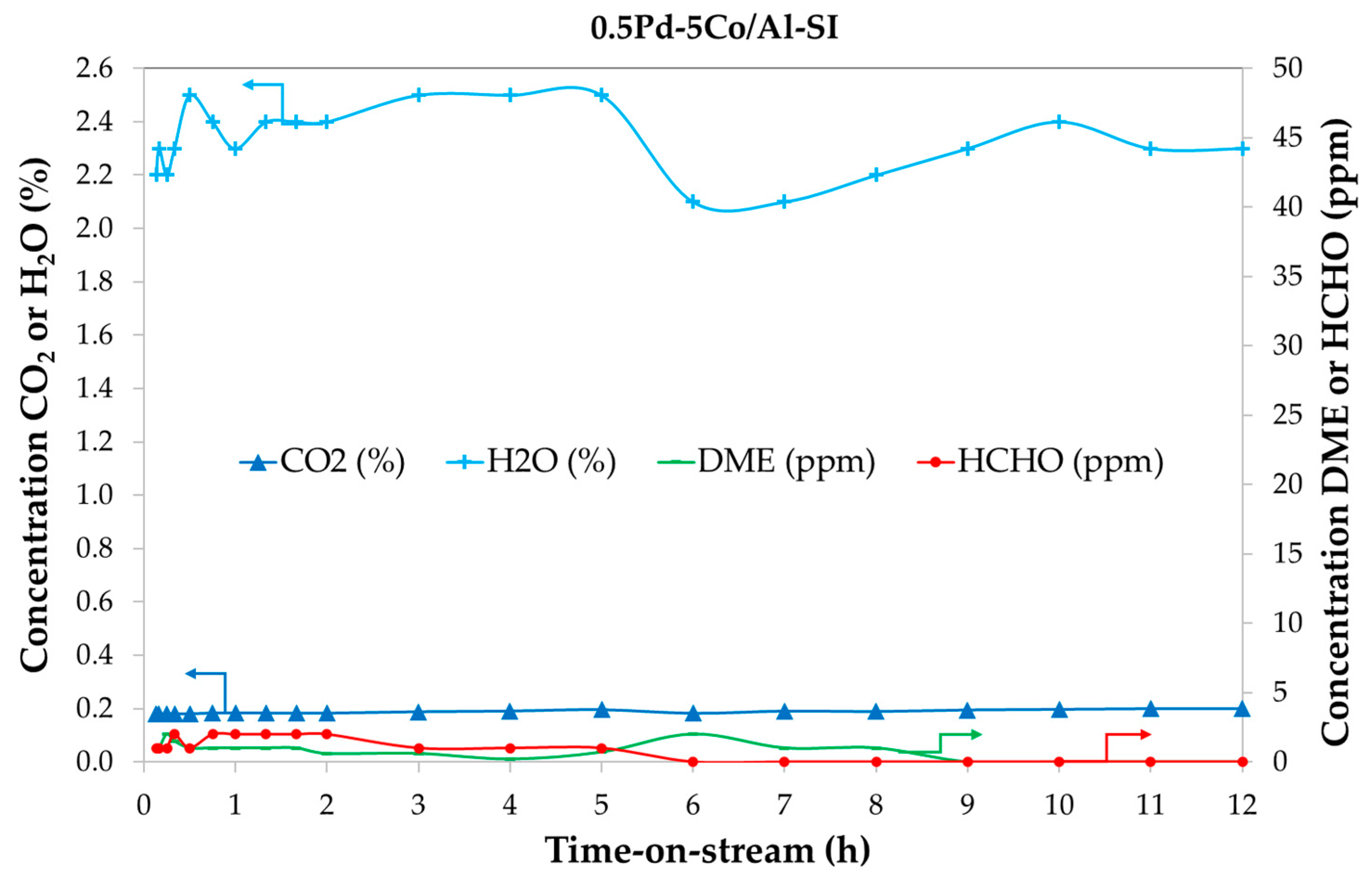

2.4.2. Catalyst Stability with Time-on-Stream

2.5. Physicochemical Characteristics of Used Catalysts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Catalyst Preparation

4.2. Catalyst Characterization

4.3. Performance Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MeOH | Methanol |

| STP | Standard temperature and pressure |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| MOR | Methanol oxidation reaction |

| WI | Wet impregnation |

| DI | Dry impregnation |

| SI | Spray impregnation |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ICP-AES | Inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy |

| TPD-CH3OH | Temperature-programmed desorption of methanol |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| TPR-H2 | Temperature-programmed reduction with H2 |

| GHSV | Gas hour space velocity |

| DME | Dimethyl ether |

| TOS | Time-on-stream |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| MS | Mass spectrometer |

| RT | Room temperature |

| O2-TPD | Oxygen temperature-programmed desorption |

References

- Ott, J.; Gronemann, V.; Pontzen, F.; Fiedler, E.; Grossmann, G.; Kersebohm, D.B.; Weiss, G.; Witte, C. Methanol. In ULLMANN’S Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, G.A. Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2636–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalena, F.; Senatore, A.; Basile, M.; Knani, S.; Basile, A.; Iulianelli, A. Advances in Methanol Production and Utilization, with Particular Emphasis toward Hydrogen Generation via Membrane Reactor Technology. Membranes 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonzio, G.; Zondervan, E. Carbon Dioxide to Methanol: A Green Alternative to Fueling the Future. Comp. Methanol Sci. 2025, 4, 595–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Abatzoglou, N.S.; Achouri, I.E. Methanol to Formaldehyde: An Overview of Surface Studies and Performance of an Iron Molybdate Catalyst. Catalysts 2021, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Cui, M. Synthesis of acetic acid via methanol hydrocarboxylation with CO2 and H2. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufarrij, F.; Navarri, P.; Khojasteh, Y. Development and comparative eco-techno-economic analysis of two carbon capture and utilization pathways for polyethylene production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, G.R.K.; Panahi, M.; Yasari, E.; Rafiee, A.; Ali Fanaei, M.; Alae, H. Plantwide Simulation and Operation of a Methanol to Propylene (MTP) Process. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 153, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, L.; Cheng, W.K. Methanol as an Alternative Transportation Fuel in the US: Options for Sustainable and/or Energy-Secure Transportation, Report, Prepared by the Sloan Automotive Laboratory Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge MA 02139. 2010. Available online: https://afdc.energy.gov/files/pdfs/mit_methanol_white_paper.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2010).

- Çelebi, Y.; Aydın, H. An overview on the light alcohol fuels in diesel engines. Fuel 2019, 236, 890–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wright, L.A. Comparative Review of Alternative Fuels for the Maritime Sector: Economic, Technology, and Policy Challenges for Clean Energy Implementation. World 2021, 2, 456–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D.; Spinthiropoulos, K.; Ragazou, K.; Giovou, A.; Tsanaktsidis, C. Methanol, a Plugin Marine Fuel for Green House Gas Reduction—A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddey, S.; Badwal, S.P.S.; Kulkarni, A.; Munnings, C. Comprehensive review of direct carbon fuel cell technology. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 360–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Turner, J.W.G.; Sileghem, L.; Vancoillie, J. Methanol as a fuel for internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 70, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, X.; Liu, Z. The effect of methanol production and application in internal combustion engines on emissions in the context of carbon neutrality: A review. Fuel 2022, 320, 123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, J.S.; Golovoy, A.; Labana, S.S. Effect of Methanol on Exhaust Composition of a Fuel Containing Toluene, n-Heptane, and Isooctane. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1970, 20, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ai, C.; Dang, F.; Xu, H.; Wan, J.; Guan, W.; Albilali, R.; He, C. Simultaneously Promoted Water Resistance and CO2 Selectivity in Methanol Oxidation Over Pd/CoOOH: Synergy of Co−OH and the Pd−Olatt−Co Interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 18414–18425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aguilar-Rios, G.; Wang, R. Inhibition of carbon monoxide on methanol oxidation over g-alumina supported Ag, Pd and Ag–Pd catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 147, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Tang, S. Microscopic oxidation reaction mechanism of methanol in H2O/CO2 impurities: A ReaxFF molecular dynamics study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 26058–26071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, O.; Ito, K. Catalytic oxidation of unburned methanol with presence of engine exhaust components from a methanol-fueled engine. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1988, 53, 3454–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cai, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wei, K. Complete methanol oxidation in carbon monoxide streams over Pd/CeO2 catalysts: Correlation between activity and properties. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 136, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoli, M.; Vindigni, F.; Tabakova, T.; Lamberti, C.; Dimitrov, D.; Ivanov, K.; Agostini, G. Structure-reactivity relationship in Co3O4 promoted Au/CeO2 catalysts for the CH3OH oxidation reaction revealed by in situ FTIR and operando EXAFS studies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2083–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippits, M.J. Catalytic Behavior of Cu, Ag and Au Nanoparticles. A Comparison. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiteit Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16220 (accessed on 7 December 2010).

- Zafeiratos, S.; Dintzer, T.; Teschner, D.; Blume, R.; Hävecker, M.; Knop-Gericke, A.; Schlögl, R. Methanol oxidation over model cobalt catalysts: Influence of the cobalt oxidation state on the reactivity. J. Catal. 2010, 269, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustov, A.L.; Tkachenko, O.P.; Kustov, L.M.; Romanovsky, B.V. Lanthanum cobaltite perovskite supported onto mesoporous zirconium dioxide: Nature of active sites of VOC oxidation. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 1053–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M. Effects of Support on Performance of Methanol Oxidation over Palladium-Only Catalysts. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2020, 231, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoveña-Uribe, A.; Ledesma-Durán, A.; Torres-Enriquez, J.; Santamaría-Holek, I. Theoretical Insights into Methanol Electro-Oxidation on NiPd Nanoelectrocatalysts: Investigating the Carbonate–Palladium Oxide Pathway and the Role of Water and OH Adsorption. Catalysts 2025, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Fernandes, R.; Patel, R.; Spreitzer, M.; Patel, N.H. A review of cobalt-based catalysts for sustainable energy and environmental applications. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2023, 661, 119254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatok, M.; Sensoy, M.G.; Vovk, E.I.; Ustunel, H.; Toffoli, D.; Ozensoy, E. Formaldehyde Selectivity in Methanol Partial Oxidation on Silver: Effect of Reactive Oxygen Species, Surface Reconstruction, and Stability of Intermediates. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6200–6209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglio, M.; Bezzo, F.; Gavriilidis, A.; Cao, E.; Al-Rifai, N.; Galvanin, F. Identification of kinetic models of methanol oxidation on silver in the presence of uncertain catalyst behavior. AIChE J. 2019, 65, 16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłonska, M.; Nocun, M.; Bidzinska, E. Silver–Alumina Catalysts for Low-Temperature Methanol Incineration. Catal. Lett. 2016, 146, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykaki, M.; Pachatouridou, E.; Iliopoulou, E.; Carabineiro, S.A.C.; Konsolakis, M. Impact of the synthesis parameters on the solid-state properties and the CO oxidation performance of ceria nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darda, S.; Pachatouridou, E.; Lappas, A.; Iliopoulou, E. Effect of Preparation Method of Co-Ce Catalysts on CH4 Combustion. Catalysts 2019, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarmazya, S.S.; Panagiotopoulou, P.; Kambolis, A.; Papadopoulou, C.; Kondarides, D.I. Methanol dehydration to dimethylether over Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 145, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chen, Q. On the promoting effect of the addition of CexZr1-xO2 to palladium based alumina catalysts for methanol deep oxidation. Mater. Res. Bull. 2015, 62, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Mu, W.; Li, X.; Li, Z. Methanol total oxidation as model reaction for the effects of different Pd content on Pd-Pt/CeO2-Al2O3-TiO2 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2017, 429, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordi, E.M.; Falconer, J.L. Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds on Al2O3, Pd/Al2O3, and PdO/Al2O3 Catalysts. J. Catal. 1996, 162, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska, M.; Król, A.; Kukulska-Zając, E.; Tarach, K.; Girman, V.; Chmielarz, L.; Góra-Marek, K. Zeolites Y modified with palladium as effective catalysts for low-temperature methanol incineration. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166–167, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, T.F.; Abraham, M.A.; Silver, R.G. Mixture Effects and Methanol Oxidation Kinetics over a Palladium Monolith Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1994, 33, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulou, E.F.; Pachatouridou, E.; Lappas, A.A. Novel Nanostructured Pd/Co-Alumina Materials for the Catalytic Oxidation of Atmospheric Pollutants. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M. Porous Co3O4 column as a high-performance Lithium anode material. J. Porous Mater. 2021, 28, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylet, A.; Marecot, P.; Duprez, D.; Castellazzi, P.; Groppi, G.; Forzatti, P. In situ Raman and in situ XRD analysis of PdO reduction and Pd0 oxidation supported on γ-Al2O3 catalyst under different atmospheres. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 4607–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keijzer, P.H.; van den Reijen, J.E.; Keijzer, C.J.; de Jong, K.P.; de Jongh, P.E. Influence of atmosphere, interparticle distance and support on the stability of silver on a-alumina for ethylene epoxidation. J. Catal. 2022, 405, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kahnt, M.; van Valen, Y.; Bergh, T.; Blomberg, S.; Lyubomirskiy, M.; Schroer, C.G.; Venvik, H.J.; Sheppard, T.L. Restructuring of Ag catalysts for methanol to formaldehyde conversion studied using in situ X-ray ptychography and electron microscopy. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanerika, R.; Shozi, M.L.; Friedrich, H.B. Synthesis and Characterization of Ag/Al2O3 Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of 1--Octyne and the Preferential Hydrogenation of 1-Octyne vs 1-Octene. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 4026–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousji, R.; Ksibi, Z.; Ghorbel, A.; Fontaine, C. Ag-Based Catalysts in Different Supports: Activity for Formaldehyde Oxidation. Adv. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2022, 12, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldur, C.; Balikci, F. Catalytic oxidation of CO over Ag-Co/alumina catalysts. Chem. Eng. Comm. 2003, 190, 986998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordi, E.M.; Falconer, J.L. Oxidation of volatile organic compounds on a Ag/A12O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1997, 151, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, O.O.; Maity, S. Temperature programme reduction (TPR) studies of cobalt phases in γ-alumina supported cobalt catalysts. J. Pet. Technol. Altern. Fuels 2016, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deori, K.; Deka, S. Morphology oriented surfactant dependent CoO and reaction time dependent Co3O4 nanocrystals from single synthesis method and their optical and magnetic properties. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2013, 15, 8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natile, M.M.; Glisenti, A. Study of Surface Reactivity of Cobalt Oxides: Interaction with Methanol. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 3090–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Seiler, M.; Hunger, M. Role of Surface Methoxy Species in the Conversion of Methanol to Dimethyl Ether on Acidic Zeolites Investigated by in Situ Stopped-Flow MAS NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 12553–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.L. The Scherrer Formula for I-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | Metal Content (wt.%) | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) | Co3O4 Crystallite Size (nm) (ii) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co | Ag | Pd | Pt | |||||

| γ-Al2O3 | - | - | - | - | 238 | 0.61 | 10.3 | - |

| 5Co/Al-SI (i) | 5.50 | - | - | - | 203 | 0.56 | 11.1 | 37 |

| 0.1Pd-5Co/Al-SI | 5.40 | - | 0.12 | - | 208 | 0.58 | 10.8 | 32 |

| 0.5Pd-5Co/Al-SI (i) | 5.46 | - | 0.58 | - | 210 | 0.57 | 10.8 | 30 |

| 0.1Pt-5Co/Al-SI | 5.40 | - | - | 0.17 | 203 | 0.56 | 10.8 | 35 |

| 0.5Pt-5Co/Al-SI | 5.40 | - | - | 0.60 | 203 | 0.56 | 10.7 | 32 |

| 2Ag-5Co/Al-SI | 5.10 | 1.80 | - | - | 204 | 0.56 | 10.7 | 38 |

| 5Ag/Al-WI | - | 5.90 | - | - | 203 | 0.58 | 10.0 | - |

| 5Ag/Al-SI | - | 5.48 | - | - | 200 | 0.57 | 11.4 | - |

| 0.5Pd-5Ag/Al-SI | - | 5.47 | 0.47 | - | 210 | 0.56 | 10.6 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pachatouridou, E.; Lappas, A.; Iliopoulou, E. Methanol Oxidation over Pd-Doped Co- and/or Ag-Based Catalysts: Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO). Catalysts 2025, 15, 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121129

Pachatouridou E, Lappas A, Iliopoulou E. Methanol Oxidation over Pd-Doped Co- and/or Ag-Based Catalysts: Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO). Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121129

Chicago/Turabian StylePachatouridou, Eleni, Angelos Lappas, and Eleni Iliopoulou. 2025. "Methanol Oxidation over Pd-Doped Co- and/or Ag-Based Catalysts: Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO)" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121129

APA StylePachatouridou, E., Lappas, A., & Iliopoulou, E. (2025). Methanol Oxidation over Pd-Doped Co- and/or Ag-Based Catalysts: Effect of Impurities (H2O and CO). Catalysts, 15(12), 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121129