1. Introduction

The development and application of nanocomposites (NCs) composed of metal-based nanomaterials embedded within polymer matrices have attracted significant attention in recent years [

1,

2]. The performance of nanoparticles (NPs) in various applications is strongly influenced by their size, shape and surface area-to-volume ratio. Incorporating these NPs into polymer matrices can further enhance their functionality, stability and processability. Metal oxide-polymer nanocomposites, in particular, have been widely studied due to the synergistic properties arising from the association of both components. Consequently, these NCs show great potential for a broad range of applications, including catalysis, electronics, photonics, biotechnology, nanomedicine and wastewater treatment [

3,

4].

Numerous organic and inorganic contaminants frequently enter water supplies, rendering the water unsafe for human consumption [

5]. These pollutants include chromophore-containing dyes with auxochromes, toxic pharmaceuticals, heavy metals and rare-earth elements, many of which, despite their technological significance, pose serious risks to ecological systems, animals, plants and human health. For instance, Khalili et al. employed a ZnO–CdO NC to adsorb methylene blue (MB) from aqueous solutions [

6]. Their study emphasized that even trace concentrations of dye compounds can adversely affect aquatic ecosystems. The results demonstrated that the nanocomposite efficiently and rapidly removed color pollutants from water, highlighting its potential for environmental remediation [

6,

7]. Munawar et al. employed a ternary metal oxide nanocomposite, NiO–CdO–ZnO, for the photocatalytic removal of cationic dyes, demonstrating remarkable degradation efficiency [

8].

Synthetic dyes are widely used across various industries, including food, textiles, personal care products, pharmaceutical formulations, packaging materials, printing and coating applications, such as inks, paints, lacquers, soaps and industrial lubricants [

9]. However, the discharge of dye-laden domestic and industrial effluents into water bodies poses a significant environmental threat, as these pollutants often enter freshwater systems and ultimately flow into the ocean. Notably, even at very low concentrations, these chemical compounds and their derivatives can exhibit mutagenic or carcinogenic effects in humans. Consequently, they represent a serious health hazard not only to human populations but also to aquatic ecosystems.

In industrial effluents, particularly those originating from the textile industry, approximately 2% of the strongly colored and non-biodegradable dyes used are typically lost during processing. As a result, dye concentrations in wastewater are estimated to range between 10 and 25 mg/L. Even small quantities of these dyes released into the environment can pose significant ecological and health risks, demonstrating the importance of their detection and removal. Consequently, numerous chemical, physical and biological methods have been investigated for the treatment of hazardous substances in wastewater streams [

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], including chemical oxidation processes, advanced oxidation techniques, membrane-based filtration systems, coagulation–flocculation methods, and electrochemical treatment approaches [

19], biodegradation pathways, fluorometric analysis and adsorption-based removal technologies, all of which contribute to the effective management of dye-polluted wastewater [

25]. However, photocatalytic degradation has become recognized as a fast, efficient and cost-effective method for dye removal, making it a highly practical approach for wastewater treatment [

4,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

The antibacterial properties of ZnO NPs and NCs against various pathogenic bacteria have attracted significant interest [

11,

12,

15,

21]. In green synthesis approaches, plant extracts from several species have proven effective in synthesizing ZnO NPs in an eco-friendly and sustainable manner [

1,

2,

12,

21,

34,

35,

36]. Given increasing environmental concerns, it has become imperative to develop greener methods for nanoparticle synthesis. Utilizing natural substances such as vitamins, phytochemicals, eco-friendly polymers, and microorganisms as reducing and stabilizing agents offers a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical synthesis. The plant species and the nature of the extract significantly influence the size and morphology of the resulting nanoparticles. Moreover, the enhanced bioactivity of green-synthesized NPs is attributed to synergistic interactions between the bioactive molecules present in the plant extracts and the nanomaterial precursors [

1,

2,

36]. Spinach (

Spinacia oleracea), for example, is well known for its anti-inflammatory properties. Owing to its rich content of biologically active phytochemicals, it effectively scavenges free radicals and reactive oxygen species. In addition to its antioxidant capacity, spinach has demonstrated antimicrobial, anticancer, antiulcer, antidiabetic, and antithrombotic activities [

2].

The widespread use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections has contributed to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains. Beyond the overuse of these drugs, the adaptive nature of pathogenic bacteria, enabling them to survive in diverse environmental conditions, further complicates treatment strategies.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is a widely studied material, particularly for its applications in water-based systems aimed at the degradation of organic pollutants. Its popularity arises from several key properties, including its relatively small band gap, environmental safety, low production cost, and rapid catalytic activation [

3,

4,

37,

38,

39,

40]. ZnO is generally regarded as a wide band gap semiconductor with a band gap of approximately 3.2–3.4 eV, which lies in the ultraviolet (UV) range [

37,

38,

39,

40]. However, ZnO NPs typically show a reduction in band gap compared to bulk ZnO, due to factors such as particle size, doping or surface modification [

4,

13,

22]. When synthesized at the nanoscale, ZnO may exhibit band gaps in the range of approximately 2.5–3.0 eV, although some nanoparticles can retain values close to that of bulk ZnO (~3.3 eV), depending on defects, oxygen vacancies, quantum confinement effects or interactions with other materials (e.g., CuO, SnO

2, Ag, polymers, etc.) [

37,

39,

40]. This reduction enables ZnO nanoparticles to absorb visible light in addition to UV radiation. The photocatalytic performance of ZnO (and other materials) under visible light irradiation can be further enhanced through the incorporation of suitable additives or dopants, which has proven to be an effective strategy for tailoring and improving its photocatalytic activity [

27,

29,

31,

32,

41,

42,

43,

44].

Copper(II) oxide (CuO) is a p-type semiconductor commonly employed to enhance the photocatalytic efficiency of wide band gap materials such as ZnO, TiO

2, and SnO

2 [

45,

46]. The CuO/ZnO mixed metal oxide nanomaterial exhibits superior photocatalytic performance compared to either pure ZnO or CuO alone [

3,

4,

30]. This improvement is attributed to the reduced recombination rate of photogenerated electron–hole pairs within the coupled system, resulting in enhanced photocatalytic activity. Coupling semiconductors with compatible band structures, such as ZnO and CuO, not only facilitates charge separation but also extends the photoresponse of ZnO into the visible light region, thereby enabling photocatalytic activity under solar irradiation. Several studies have reported the successful synthesis of CuO/ZnO nanomaterials using environmentally friendly, green methods [

3,

20,

27,

46,

47].

Among the various synthesis methods, the visible-light-induced hydrothermal growth technique stands out as a promising and well-established approach for producing nanostructured composites [

3,

4,

26,

47,

48]. This method offers several advantages, including mild synthesis temperatures, precise control over composition and tunable particle size. Compared to other techniques, hydrothermal synthesis provides superior nucleation control, requires simple equipment, enables catalyst-free growth and allows for one-step synthesis. Additionally, materials produced by this method typically exhibit low aggregation, the ability to form amorphous phases, generate fewer hazardous by-products and often do not require post-treatment [

3,

4].

Alginate is a water-soluble polymer extracted from algae, composed of linear copolymers of two monomers: α-L-guluronic acid (G) and β-D-mannuronic acid (M) [

7,

14]. These monomer units arrange into homopolymeric M-blocks and G-blocks, or heteropolymeric alternating MG-blocks, connected by 1→4 glycosidic linkages. The sequence and distribution of these blocks along the polymer chain significantly influence the physical and chemical properties of alginate. One of its key characteristics is the ability to form gels through selective binding with divalent cations such as Ca

2+, Ba

2+, Zn

2+ and Cu

2+ [

7,

47].

Marine polysaccharides such as chitosan, alginate, hyaluronic acid and their derivatives have been widely utilized in biomedical applications due to their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and low cost [

49,

50,

51]. Among these, alginate stands out for its unique ability to help maintain homeostasis, making it particularly valuable in medical and therapeutic contexts [

52,

53].

This paper focuses on the development of ZnO/CuO/Alg hydrogel beads by encapsulating ZnO and CuO NPs within an alginate biopolymer matrix. The use of alginate NC beads enhances pollutant removal efficiency. Encapsulation of NPs in alginate not only improves their dispersion and immobilization but also increases the effective surface area of the nanocomposite, thereby particularly benefiting antibacterial activity [

7,

47]. To characterize the synthesized materials, various techniques were employed, including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (SEM-EDX), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and ultraviolet–visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy for band gap analysis and photoluminescence (PL) for photochemical analysis.

MB was selected as the model pollutant because it is one of the most widely used cationic dyes in photocatalytic studies and represents a persistent organic contaminant in wastewater [

7,

30,

32,

33,

54,

55]. It is also highly stable under visible light and cannot be degraded efficiently by photolysis alone, making it a suitable benchmark dye for evaluating photocatalyst performance [

55].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

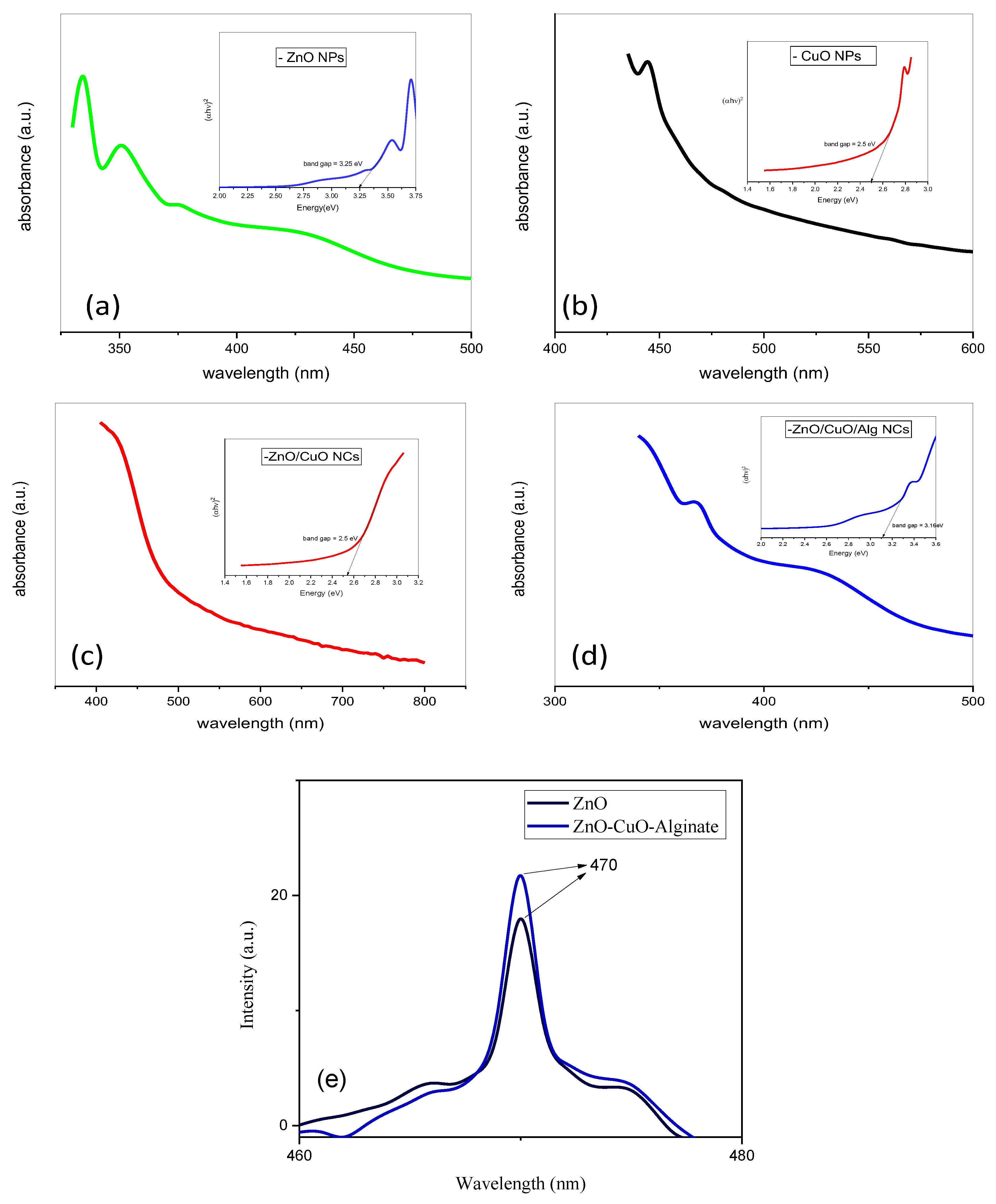

Herein, we present a simple and eco-friendly method for synthesizing ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs using plant extracts as both reducing and capping agents. The optical properties of the synthesized samples were analyzed using UV-vis spectroscopy. The absorption spectra of ZnO NPs, CuO NPs, ZnO/CuO NCs and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs are presented in

Figure 1a–d.

Samples (a), (b), (c), and (d) exhibit prominent absorption peaks at approximately 350–400 nm, 457 nm, 397 nm and 392 nm, respectively. The peaks at 397 nm and 457 nm correspond to the intrinsic band gap transitions related to the conduction band. The band gap energies were calculated from the absorption edges using Tauc’s equation, allowing evaluation of the electronic properties of the nanomaterials:

where α represents the absorption coefficient, hν denotes the photon energy, and A is a constant related to the effective mass of electrons. Based on the Tauc plots derived from

Figure 1a–d, the calculated band gap energies (E

g) for the samples were 3.26 eV, 2.52 eV, 3.16 eV and 2.50 eV, respectively. These calculated values represent the apparent optical band gaps derived from the overall absorption behavior of the samples rather than the intrinsic E

g of individual semiconductor phases. In the ZnO/CuO composite and ZnO/CuO/Alg systems, the observed E

g reflects the influence of interfacial charge transfer and band alignment between ZnO and CuO. ZnO, a wide band gap n-type semiconductor (~3.2–3.4 eV), has conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) edges located at approximately −4.19 eV and −7.45 eV (vs. vacuum), respectively, whereas CuO, a p-type semiconductor with a narrower band gap (~1.2–1.9 eV), possesses CB and VB positions near −4.5 eV and −5.7 eV. The difference in their band edge positions facilitates interfacial electron–hole separation and allows new optical transitions across the heterojunction interface, resulting in a reduced apparent E

g for the composite. This favorable band alignment promotes visible-light absorption and enhances the photocatalytic efficiency of the material.

Figure 1e shows the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of ZnO and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites, both exhibiting an emission peak at around 470 nm at ambient temperature. The optical characteristics of oxide nanostructures are strongly influenced by defect density and oxygen vacancies [

37]. The comparatively lower PL intensity observed for the ZnO/CuO/Alg sample suggests a reduction in electron–hole recombination, which can be attributed to efficient charge separation within the ZnO–CuO heterojunction. Additionally, the use of plant-based precursors may contribute to the lower emission efficiency compared to chemically synthesized counterparts.

2.2. Powder X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

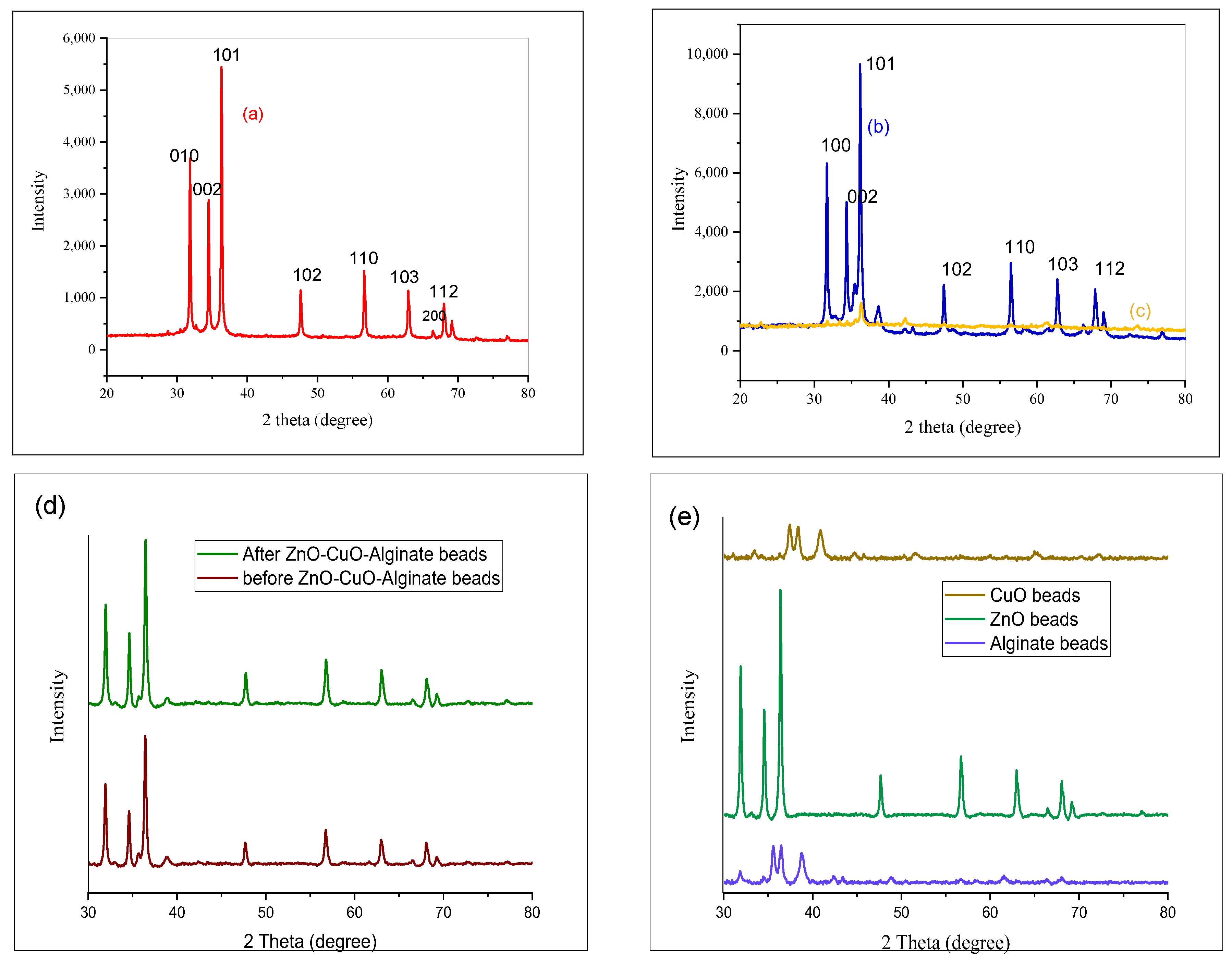

Figure 2a–c displays the PXRD patterns of ZnO, ZnO/CuO NC and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs. For sample (a), the calculated lattice constants were a = 3.249 and c = 5.203, consistent with the hexagonal crystal system of pure ZnO. No impurity-related diffraction peaks were observed. The strong reflection peaks at 2θ = 31°, 34.44°, 36.26°, 47°, and 26° correspond to the (010), (002), (011), (110), and (112) planes, respectively, confirming good crystallinity and preferred orientations, in agreement with ICSD reference No. 980185827.

The PXRD pattern of sample (b) (ZnO/CuO NCs) exhibits peaks at 2θ = 31°, 34°, 36°, 56°, 68° attributed to the (010), (002), (011), (110), and (112) planes of the polycrystalline hexagonal ZnO/CuO (ICSD No. 980186303). Sample (c) the ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs, displays peaks at 2θ = 22°, 33°, 36°, 61°, 73° corresponding to the (002)(011), (110) and (112) planes, respectively, also matching ICSD No. 980186303.

Particle size of the samples are determined by the Debye–Scherrer equation, which relies on the broadening of X-ray diffraction peaks:

where λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.5406 Å), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak measured in radians, θ is the Bragg angle corresponding to the peak position, D is the particle size in nanometers, and k is the shape factor (normally 0.9).

The diffraction peaks corresponding to the (002), (011), and (112) planes were used to calculate the crystallite sizes using the Debye–Scherrer equation. The results are summarized in

Table 1. The calculated average crystallite sizes for samples (a), (b), and (c) were 47.6 nm, 20.0 nm, and 17.81 nm, respectively.

Defects in the synthesized nanomaterials were assessed by calculating the dislocation density (δ), which is given by:

where D is the crystallite size (in nm).

The dislocation densities for samples (a), (b), and (c) were calculated to be 4.18 × 10−4, 4.938 × 10−4, 3.15 × 10−4 nm−2, respectively. These results suggest that sample (c) possesses fewer crystallographic defects than samples (a) and (b), which may be attributed to its surface charge characteristics and improved structural stability.

To further evaluate the stability and synergistic behavior of the composites,

Figure 2e compares the structural integrity of alginate-only, ZnO/Alginate, CuO/Alginate, and ZnO/CuO/Alginate hydrogel beads after repeated photocatalytic use. The single-metal alginate beads (ZnO/Alg and CuO/Alg) exhibited partial deformation and reduced stability, whereas the ternary ZnO/CuO/Alg system maintained its shape and crystallinity, indicating improved mechanical and structural robustness.

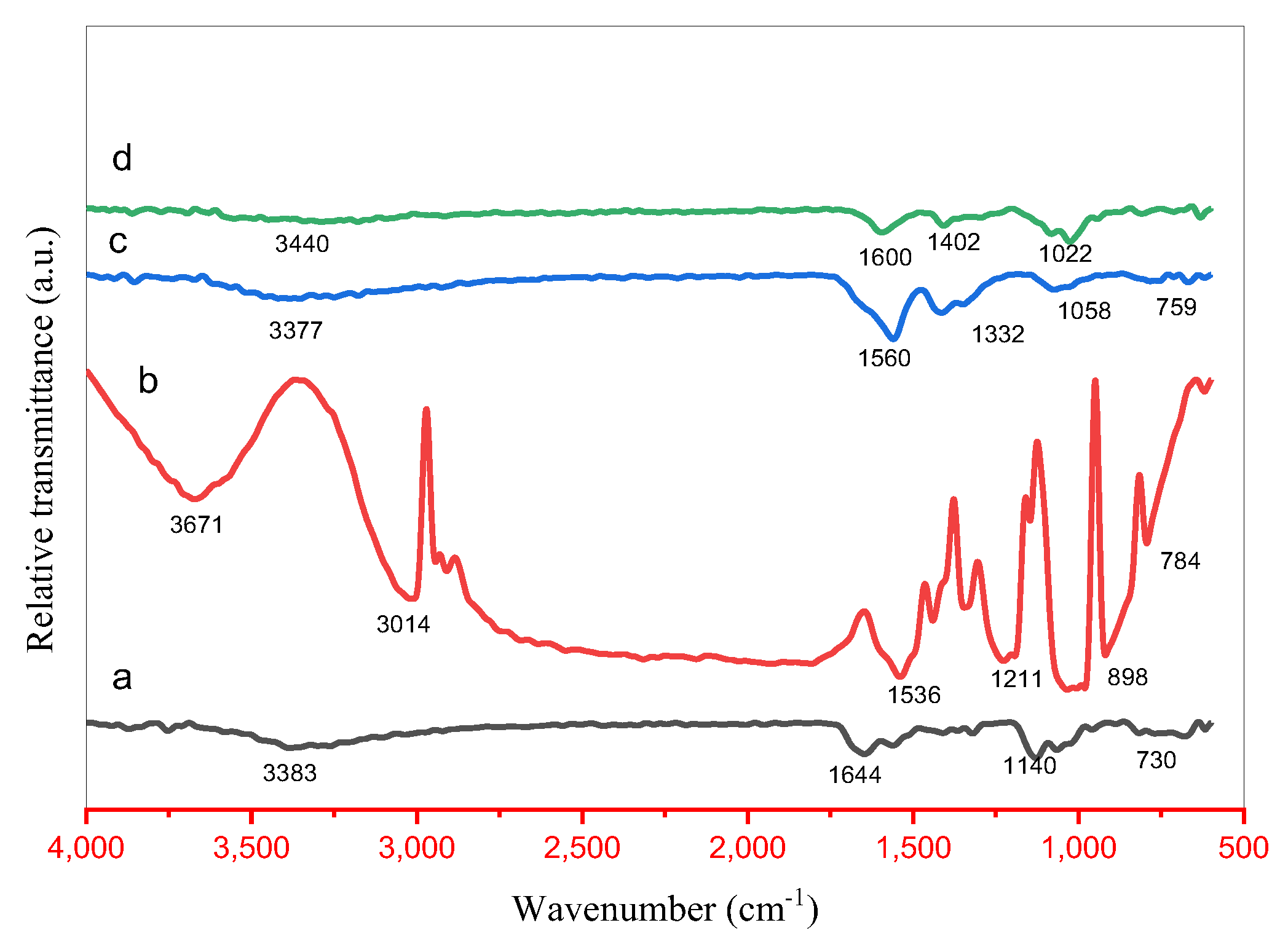

2.3. FTIR Analysis

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify the functional groups present in the synthesized samples, with spectra recorded in the range of 4000–500 cm

−1 (

Figure 3a–d). The observed absorption bands arise from phytochemical constituents and precursor-derived species, which serve as capping and stabilizing agents for the nanomaterials. Characteristic peaks correspond to functional groups such as phenolic –OH, amine (–NH), ether (C–O–C), carboxylic acid (C=O and –OH), and hydroxyl (–OH) moieties, indicating the successful incorporation of bioactive plant extract components onto the nanoparticle surfaces.

Distinct absorption bands were observed at 3671, 3440, 3383, 3377, 3693, 3391, and 3014 cm−1, corresponding to O–H stretching vibrations of phenolic groups and C–H stretching modes. Additional peaks at 1644, 1600, and 1560 cm−1 are attributed to C=C stretching and N=O bending vibrations of secondary amines. Absorption bands at 1402, 1332, 1211, and 1140 cm−1 indicate C–O stretching vibrations of ethers and carboxylic acids. The characteristic peaks at 1022, 896, 759, and 730 cm−1 are assigned to metal–oxygen stretching modes, specifically Zn–O–Zn and Cu–O bonds, confirming the successful formation of metal oxide phases in the nanocomposites.

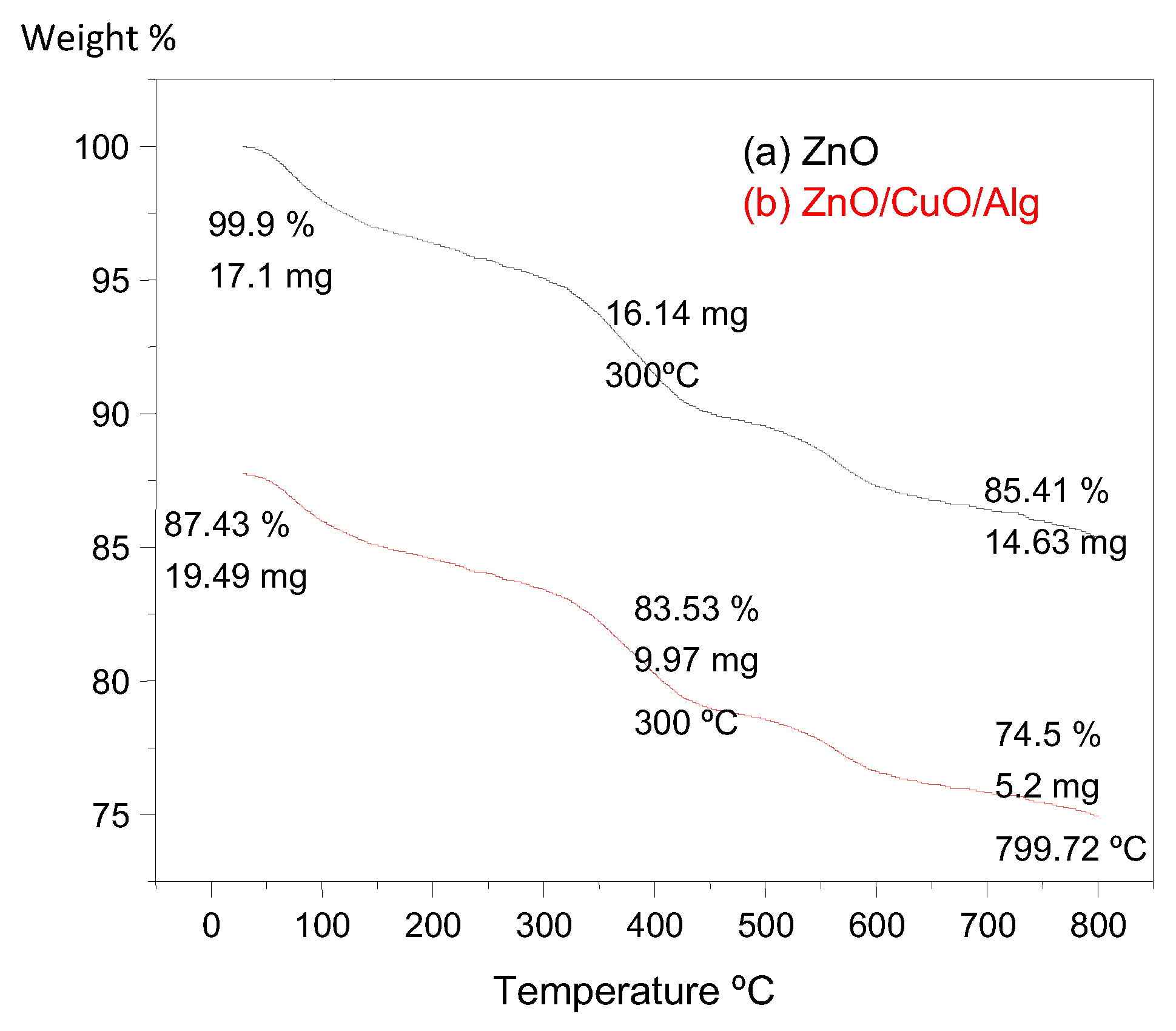

2.4. TGA

TGA was conducted to evaluate the thermal stability and quantify the organic content in the synthesized NPs and NCs. The TGA curves for ZnO and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs are presented in

Figure 4.

For ZnO, a minor weight loss of approximately 5% was observed up to 800 °C, primarily due to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water molecules. Both samples exhibited an initial weight loss around 290 °C, attributed to dehydration processes. A more significant weight loss at higher temperatures corresponds to the thermal decomposition and combustion of organic molecules derived from the plant extract, which are bound to the particle surfaces.

The initial mass of ZnO was 17.13 mg, which decreased to 14.6 mg after heating to 800 °C, indicating a total weight loss of about 14.49%. In contrast, the ZnO/CuO/Alg exhibited a more pronounced weight loss: starting at 19.49 mg and reducing to 5.28 mg at 796 °C, resulting in a total loss of approximately 72.91%. This greater reduction is attributable to the higher organic content, especially from the alginate biopolymer and phytochemicals incorporated during synthesis [

7,

47].

2.5. SEM-EDX Analysis

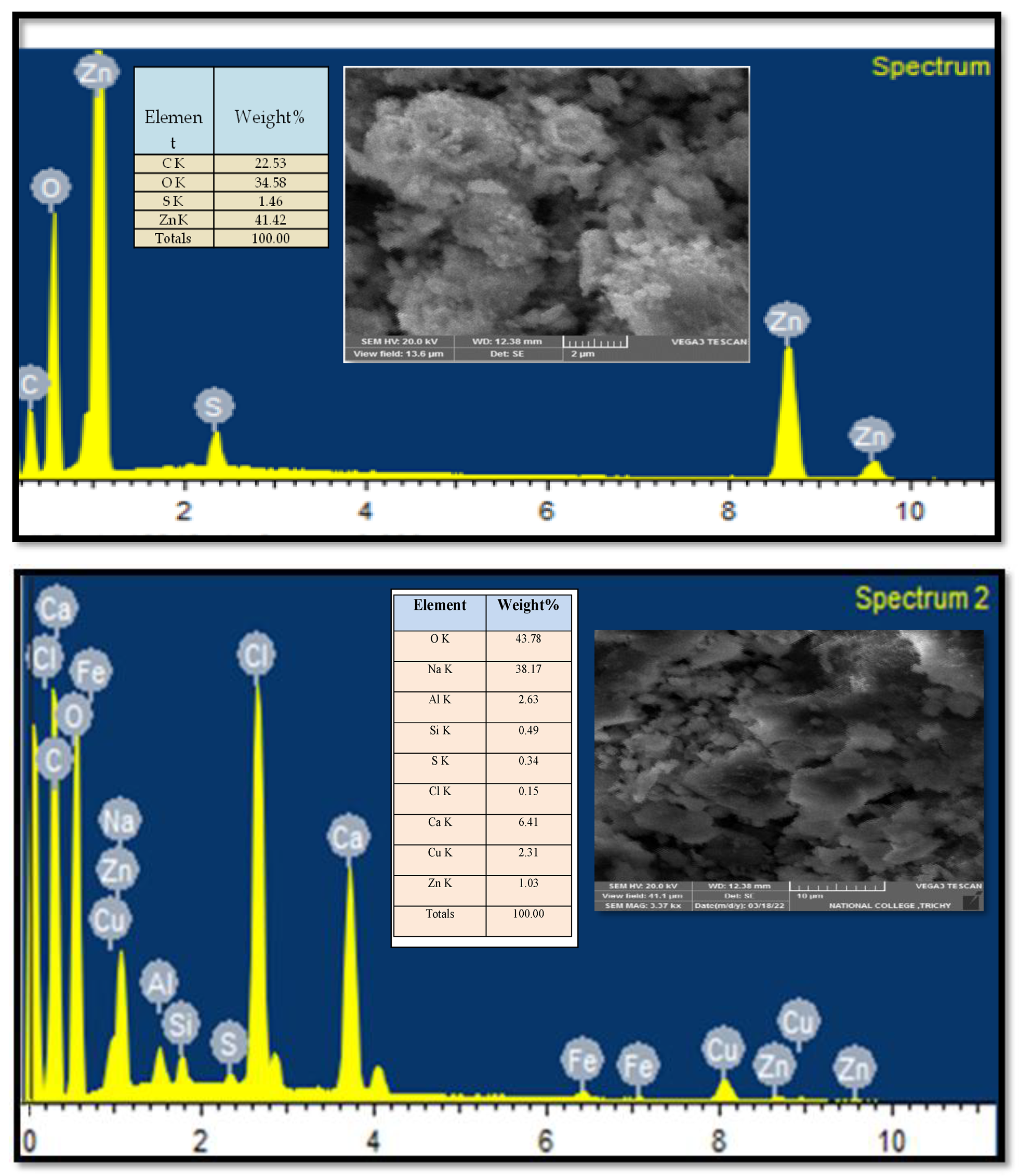

As shown in

Figure 5 the ZnO NPs (top image) exhibit an uneven, irregular morphology. In contrast, the ZnO/CuO/Alg NC displays a more uniform distribution of particles with a notably larger surface area. Such morphology and dispersion are advantageous, as they enhance the catalytic activity of these materials compared to less homogenous counterparts. The micrographs reveal a mostly monodispersed particle population, with average sizes ranging from 18 to 21 nm. Additionally, larger aggregates formed by clusters of smaller particles are also evident.

2.6. TEM Analysis

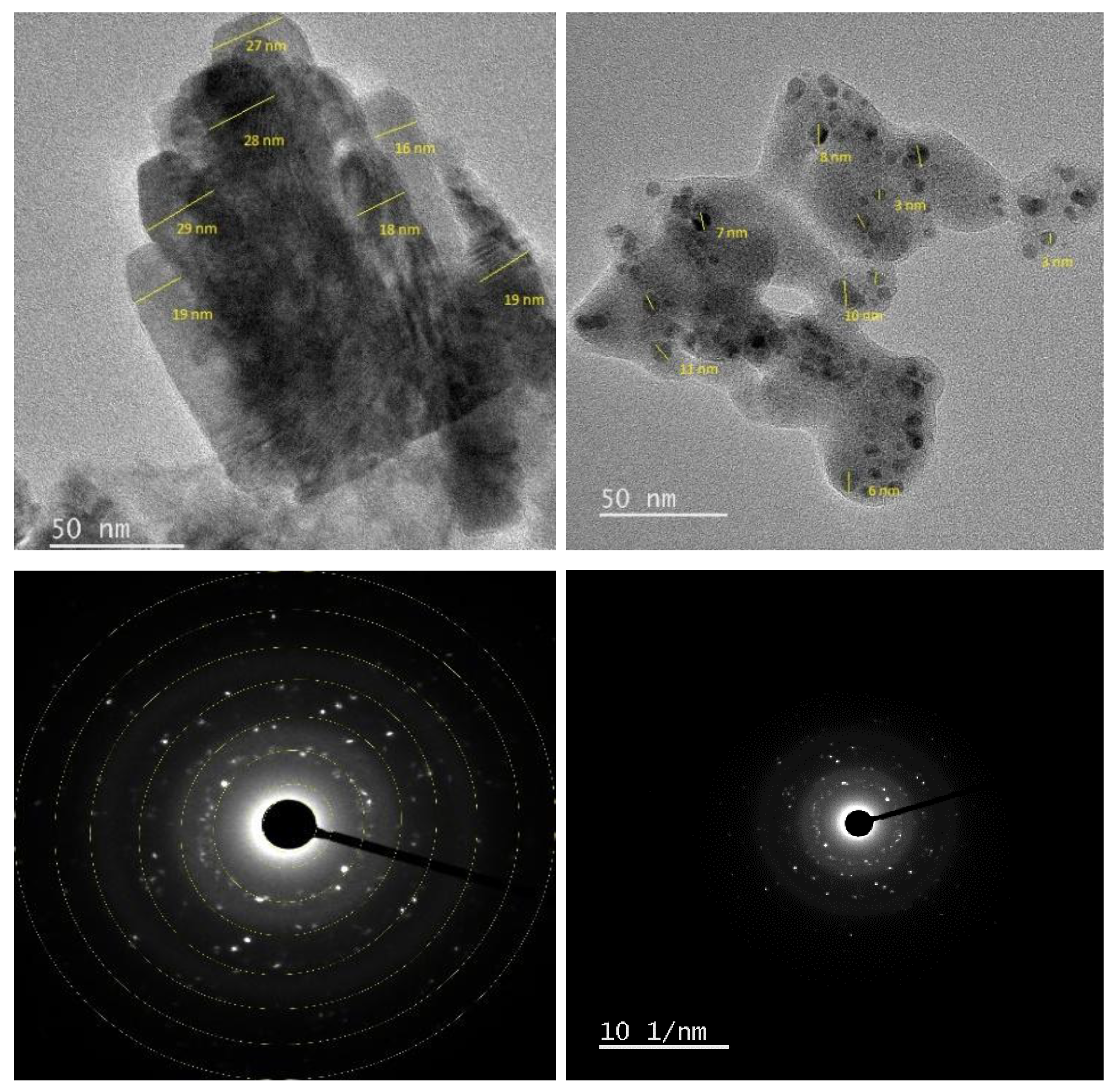

The size and shape of the synthesized adsorbents were examined using TEM. As shown in

Figure 6, the images reveal a matrix composed of spherical to ellipsoidal particles, most of which measure less than 20 nm. The particle size distribution curve indicates sizes ranging from 1 to 50 nm, with the majority clustered between 1 and 14 nm (

Figure 6). While most particles are well-dispersed, some localized aggregation is evident, suggesting an overall stable dispersion of the nanomaterials.

Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) analysis further confirmed the structural features of the functionalized nanocomposites, with the pattern displaying distinct diffraction rings and bright spots characteristic of polycrystalline materials.

2.7. Photocatalysis and Degradation of MB

2.7.1. Effect of Catalyst Loading

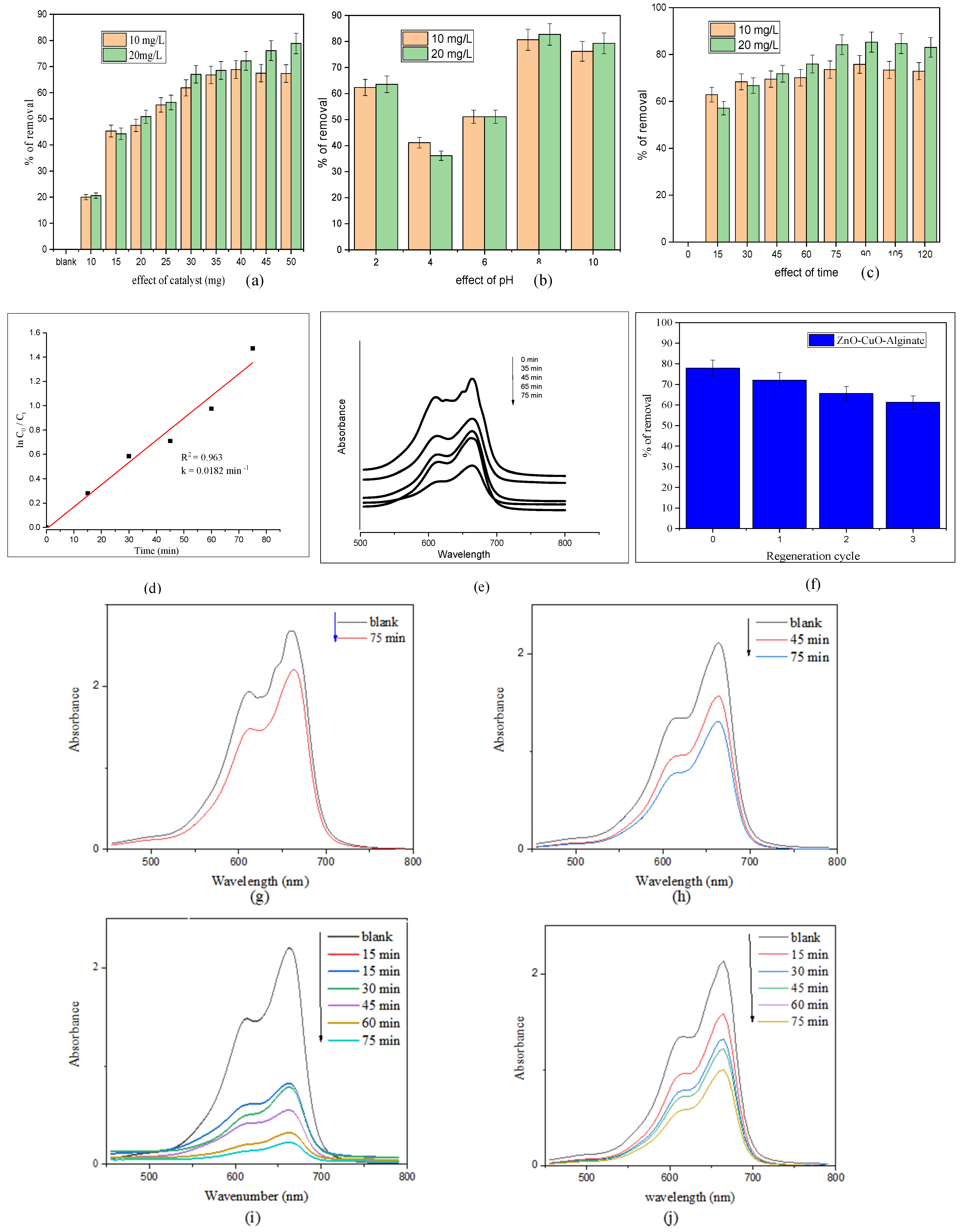

The effect of catalyst loading on the removal of MB dye was investigated by varying the catalyst amount from 10 mg to 60 mg, using dye solutions of 10 and 20 mg/L at pH 8 under sunlight irradiation for 75 min. As depicted in

Figure 7a, the dye degradation efficiency increased with catalyst dosage from 10 mg to 50 mg. Beyond 50 mg, the degradation rate plateaued, indicating that further increases in catalyst amount did not significantly improve the removal efficiency.

2.7.2. Effect of pH

pH plays a crucial role in influencing the reaction pathways involved in dye degradation. It also regulates the formation of hydroxyl radicals, which are key reactive species responsible for breaking down the dye molecules. The percentage of dye removal progressively increased as the pH was raised from 2 to 8, with the highest degradation of MB observed at pH 8 (

Figure 7b). This enhancement is attributed to the higher concentration of hydroxyl ions at alkaline pH, which react with photogenerated holes to generate more hydroxyl radicals, thereby accelerating the dye decolorization process.

2.7.3. Effect of Time

Figure 7c illustrates the removal efficiency of methylene blue at both dye concentrations over time. The results clearly demonstrate the enhanced photocatalytic degradation performance of the ZnO/CuO/Alg hydrogel beads under sunlight irradiation, confirming their effectiveness for pollutant removal from water.

2.7.4. Kinetics of MB Removal

The role of different catalysts in the degradation of MB was investigated. The degradation process is commonly described by a pseudo-first-order kinetic model, which has been widely applied to various organic pollutants [

7], as expressed by the following equation:

where C

0 is the initial concentration of MB in water and C

t is the concentration at time t. Using a catalyst loading of 50 mg with different MB doses, plots of ln(C

0/C

t) versus time were generated for 20 ppm MB solutions, as shown in

Figure 7d. The linearity of these plots, with good correlation coefficients (R

2) around 0.96, confirms that MB degradation follows a pseudo-first-order kinetic model. The value of the rate constant k (0.0182 min

−1) was calculated from the slope of the linear fits (

Figure 7d) [

54].

Figure 7e presents the percentage degradation of MB at various concentrations. The nanocomposite hydrogel beads (NCs) exhibited the highest degradation efficiency, achieving 77.86% removal in 75 min at pH 8. The degradation rate was faster at the lower dye concentration (20 ppm) and slower at the higher concentration (40 ppm), likely due to the effect of initial dye concentration on the photocatalytic process.

Figure 7f demonstrates the reusability of the ZnO/CuO/Alg hydrogel beads over multiple degradation cycles. Although a slight decrease in activity was observed after three cycles, attributed to the gradual surface dissolution of the alginate matrix, the composite retained significant photocatalytic efficiency, confirming its good operational stability and the beneficial synergistic interaction between ZnO and CuO within the biopolymer network.

Table 2 compares the present study’s results with other reported studies on zinc oxide-based nanocomposites irradiated with sunlight for MB degradation, highlighting the improved performance of the synthesized ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposite beads [

13].

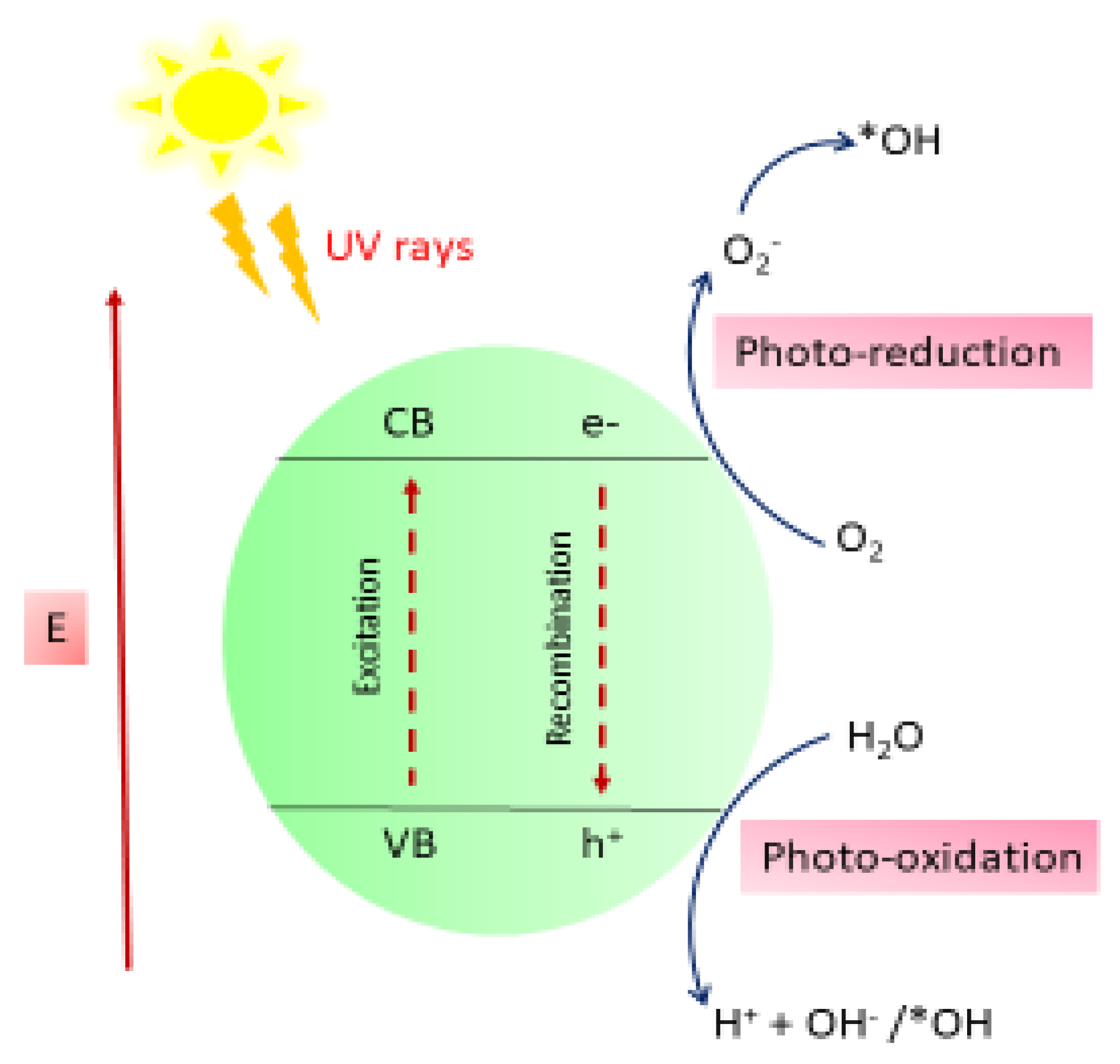

2.7.5. Photocatalytic Reaction Mechanism

The degradation of MB onto the ZnO nanocomposite (NC) hydrogel beads constitutes the initial stage of the photocatalytic process. This adsorption facilitates the sensitization of ZnO by dye molecules. Upon exposure to sunlight, electrons (e

−) in the valence band (VB) of the dye-sensitized ZnO NC hydrogel beads are excited to the conduction band (CB), leaving behind corresponding holes (h

+) in the VB. The photogenerated electrons can directly reduce dye molecules or react with electron acceptors such as oxygen (O

2) adsorbed on the ZnO surface or dissolved in water, leading to the formation of superoxide radical anions (O

2−). Concurrently, the photogenerated holes oxidize water molecules or hydroxide ions (OH

−), producing highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH). These hydroxyl radicals, along with other reactive oxygen species such as peroxide radicals, play a crucial role in the heterogeneous photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants like dyes [

14,

56]. The overall photochemical reactions occurring at the semiconductor surface, which lead to the degradation of the dye or pollutant, are summarized in

Scheme 1 and

Scheme 2:

The generated hydroxyl radicals (·OH), which are powerful oxidizing agents with a standard redox potential of +2.8 V, effectively oxidize most MB dye molecules. Even organic substrates that are less reactive toward hydroxyl radicals are degraded through the photocatalytic activity of ZnO NC hydrogel beads, leading to significant pollutant removal rates [

14,

27,

32,

33,

57].

To evaluate and compare the photocatalytic activity of different systems, control experiments were performed as shown in

Figure 7g–j. In the absence of a catalyst (

Figure 7g), only a negligible change in the MB absorbance peak at ~664 nm was observed after 75 min of visible-light irradiation, confirming that self-photolysis of MB is insignificant. Upon addition of the ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposite (

Figure 7h), a gradual decrease in absorbance occurred, indicating active photocatalytic degradation of MB. The ZnO/Alg (

Figure 7i) and CuO/Alg (

Figure 7j) hydrogel beads exhibited faster degradation of MB compared with the ZnO/CuO/Alg composite, with ZnO/Alg (

Figure 7i) showing the best results. This may be related to differences in surface exposure, dye adsorption capacity, or light scattering within the beads. Nonetheless, all catalyst-containing systems showed pronounced photocatalytic activity compared with the blank sample, confirming the efficiency of the alginate-based materials for dye removal. Siddiqui et al. demonstrated that ZnO/Alg bionanocomposite beads have superior photocatalytic degradation efficiency for MB due to optimized adsorption and exposure of active sites [

7]. Bekru et al. noted that composites like ZnO/CuO can exhibit different photocatalytic properties linked to variations in light absorption, electron–hole separation, and surface availability, potentially making single-component beads like ZnO/Alg more efficient under specific conditions [

30].

Although the ZnO/Alg and CuO/Alg hydrogel beads exhibited somewhat faster degradation of MB under the tested conditions, the ZnO/CuO/Alg composite demonstrated good structural integrity and reusability, as confirmed by XRD and repeated use experiments (

Figure 2d,e and

Figure 7f). The formation of the ZnO–CuO heterojunction within the alginate matrix also contributes to enhanced visible-light absorption and stable charge separation, as supported by UV–Vis and PL analyses. These results suggest that, while the single-metal systems may show higher initial activity, the ternary composite offers a more durable and environmentally friendly catalyst design suitable for repeated photocatalytic applications.

2.8. Antibacterial Properties

Figure 8 shows the antibacterial activity of ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites (NCs) tested against

Staphylococcus aureus, a spherical Gram-positive bacterium. The zones of inhibition (ZOIs) for

Staphylococcus aureus treated with samples (1), (2), and (3) are presented, respectively.

Staphylococcus aureus exhibited exponential growth after 24 h of incubation on nutrient agar medium (NAM). The samples showed similar inhibition trends, where increasing the concentration of nanomaterials enhanced the inhibition of

Staphylococcus aureus relative to the control (dicloxacillin) as shown in

Figure 8a. The main antibacterial activity arises from ZnO/CuO nanoparticles, which generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), release Zn

2+ and Cu

2+ ions, and interact physically with bacterial cell walls, leading to membrane disruption and leakage of intracellular components [

58]. The alginate matrix primarily functions as a stabilizing and supporting scaffold, improving nanoparticle dispersion and enabling a more controlled release of metal ions, rather than contributing significantly to antibacterial action [

58].

In

Figure 8a,c, the ZOIs for ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs at the same concentration were measured as 12 mm, 18 mm, 20 mm and 25 mm for the control, respectively. The same procedure was followed for

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a cylindrical Gram-negative bacterium.

Figure 8b,d show ZOIs of 21 mm, 15 mm, 14 mm and 30 mm, respectively.

The percentage of inhibition for bacterial cultures is shown in

Figure 8e: for

Staphylococcus aureus, ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/CuO/Alg exhibited 23.76%, 53% and 65.39%, respectively; while for

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the values were 50.24%, 26.97% and 23.65%, respectively. The antibacterial activity of ZnO, ZnO/CuO and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs at the same concentration (1.00 µg/mL) in methanol solvent is summarized in

Table 3.

Table 4 provides a comparison of the antibacterial activity of these nanomaterials with other reported materials.

3. Experimental Details

3.1. Materials

Zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(CH

3COO)

2·2H

2O), copper acetate dihydrate (Cu(CH

3COO)

2·2H

2O), sodium alginate ((C

6H

7NaO

6)

n), calcium chloride (CaCl

2), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were procured from Merck (Mumbai, India). In the experiments, 0.1 M solutions of NaOH and HCl were prepared and used for pH adjustment. MB dye (physicochemical properties listed in

Table 5) and ethanol (CH

3CH

2OH) were obtained from HIMEDIA (Mumbai, India). All experiments utilized deionized water (DI) with a resistivity greater than 6 MΩ·cm. Pure cultures of Gram-positive

Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative

Pseudomonas pneumoniae were sourced from the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. V.Y.T. PG Autonomous College, Durg (C.G.).

3.2. Green Synthesis of ZnO NPs

To prepare the plant extract, 12–15 g of spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves were boiled in 100 mL of double-distilled water for 1–2 h. The resulting extract was filtered, collected in a clean flask and stored at 8–10 °C until further use. For nanoparticle synthesis, zinc acetate was dissolved in 100 mL of distilled water to prepare a 0.1 M solution. Under constant stirring, the spinach extract was added to the zinc acetate solution in a 9:1 volume ratio. To induce precipitation and maintain the pH at 9, 1 M NaOH was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was continuously stirred at 60–70 °C for 3–4 h, during which a white precipitate formed. The precipitate was then filtered, thoroughly washed with double-distilled water and 1% ethanol solution, dried at 80 °C, and finally calcined at 400 °C to obtain ZnO NPs.

3.3. Green Synthesis of CuO NPs

Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) leaves were thoroughly cleaned, cut into small pieces, dried and then boiled in 100 mL of distilled water. The resulting extract was filtered using standard filter paper and collected for further use. Following a similar procedure as described previously, the plant extract was mixed with a 0.1 M copper acetate solution in an 8:2 volume ratio under continuous stirring at a constant temperature of 60 °C for 2 h. During the reaction, a black precipitate formed, which was subsequently washed with distilled water and ethanol, then dried at 80 °C.

3.4. Preparation of ZnO/CuO NCs

ZnO/CuO NCs were synthesized by mixing zinc acetate and copper acetate solutions in a 1:1 molar ratio. The resulting precipitate was collected, dried at 90 °C for 12 h, and then calcined in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 2 h.

3.5. Preparation of Calcium Functionalized ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs Hydrogel Beads

To prepare the alginate (Alg) NC beads, 2.0 g of sodium alginate powder was dissolved in 75 mL of double-distilled water and vigorously stirred until a thick, homogeneous solution was obtained. This solution was then thoroughly mixed with 2.5 g of ZnO/CuO NCs. The resulting mixture was introduced dropwise into a 2% CaCl

2 solution using a syringe to form gel beads. These beads were left to cure overnight to ensure complete gelation and structural stabilization. After curing, the beads were stored in an aqueous solution for future use and were repeatedly rinsed with double-distilled water to remove any residual impurities. The preparation procedure is illustrated in

Scheme 3.

3.6. Characterization Techniques

Absorbance measurements were carried out using a Systronics UV-vis spectrophotometer-117 (Cary 50 Scan, Varian, Durg, India) equipped with a 1 cm quartz cuvette (0.1 mL). The pH of the solutions was measured using a digital pH meter (Systronics Model-112, Durg, India). Photoluminescence (PL) analysis of ZnO and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites were carried out at IIT Bhilai. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to study ZnO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites at DST-SAIF, Cochin, India. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was used to examine the surface morphology and elemental composition of ZnO and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites at RashtrasantTukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University, Nagpur. Detailed morphological features and particle shapes were investigated using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images of ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites, obtained with a JEOL JEM-2100 instrument at Cochin, India. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) of ZnO nanoparticles and ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites was also performed at Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University, Nagpur.

3.7. Photocatalytic Degradation

Following characterization, the synthesized NC hydrogel beads were employed as catalysts for the photocatalytic degradation of MB dye. A 20 ppm MB stock solution was prepared (λmax = 664 nm), and dye solutions of varying concentrations were subsequently prepared. The pH of each solution was adjusted to the optimal value for degradation. An appropriate amount of catalyst was added to each solution to optimize photocatalytic performance. Prior to sunlight exposure, the mixtures were agitated for 15 min at room temperature using an orbital shaker to establish adsorption–desorption equilibrium. At predetermined time intervals, aliquots were withdrawn from the reaction mixture, and the residual dye concentration was measured using UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

3.8. Antibacterial Assessment

For the assessment of antibacterial activity, ZnO NPs and NCs were prepared as 10 mg/mL suspensions in methanol, which served as a negative control and exhibited no inhibitory effect on microbial growth. To ensure proper homogenization, the suspensions were vortexed thoroughly after mixing with the solvent. Antibacterial efficacy was evaluated using the well diffusion assay on nutrient agar medium (NAM).

Under sterile conditions, nutrient agar was poured into Petri dishes and allowed to solidify for 1 h. Fresh overnight cultures of Pseudomonas pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus (adjusted to 100 mg/mL) were evenly spread over the solidified agar surface using a sterile spreader. The plates were incubated for 15–20 min to allow absorption of the bacterial cultures. Subsequently, wells of 7–8 mm diameter were aseptically punched into the agar, and 1 mg/mL of ZnO NPs and NC samples were introduced into the wells.

The plates were kept at room temperature for 30 min to allow diffusion of the samples, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h to promote bacterial growth. After incubation, antibacterial activity was evaluated by measuring the zones of inhibition (ZOI) around the wells, indicating suppression of microbial proliferation.

4. Conclusions

In this work, ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) and ZnO/CuO/Alginate nanocomposites (NCs) were successfully synthesized through a green, sustainable and non-toxic approach employing Spinacia oleracea (spinach) and Coriandrum sativum (coriander) leaf extracts as natural reducing and capping agents. This bio-mediated route eliminates hazardous reagents and provides an efficient, environmentally benign strategy for metal oxide nanomaterial fabrication.

Comprehensive characterization confirmed the successful formation and stabilization of the nanostructures. UV–Vis spectra displayed strong absorption bands at 350–400 nm, 457 nm, 397 nm, and 392 nm for ZnO, CuO, ZnO/CuO, and ZnO/CuO/Alg NCs, respectively, corresponding to band gap energies of 3.26 eV, 2.52 eV, 3.16 eV, and 2.50 eV. The PL emission peak at ~470 nm exhibited relatively lower intensity, which may be ascribed to the presence of plant-derived organic moieties that introduce mild surface defects. XRD analysis confirmed a hexagonal wurtzite phase for ZnO and a polycrystalline structure for the composites, with average crystallite sizes of 47.6 nm (ZnO), 20.0 nm (ZnO/CuO), and 17.81 nm (ZnO/CuO/Alg). The corresponding dislocation densities were calculated as 4.18 × 10−4, 4.94 × 10−4, and 3.15 × 10−4 nm−2, indicating improved structural integrity and reduced lattice defects in the alginate-incorporated nanocomposite.

FTIR spectra revealed characteristic absorption bands of Zn–O, Cu–O, O–H, C=O, and C–O groups, confirming the effective capping and stabilization of the nanoparticles by phytochemical constituents. TGA demonstrated that the ZnO/CuO/Alg NC exhibited a total mass loss of 72.91% up to 800 °C, significantly higher than the 14.49% recorded for ZnO, due to the greater presence of organic biopolymers. SEM and TEM micrographs showed nearly spherical, monodispersed particles with sizes ranging from 18 to 21 nm, while EDX verified their compositional purity.

The photocatalytic activity of the ZnO/CuO/Alg hydrogel beads under solar irradiation exhibited superior performance in the degradation of MB. The optimized conditions (50 mg catalyst, pH 8, 75 min exposure) resulted in a maximum degradation efficiency of 77.86%, following pseudo-first-order kinetics with a rate constant (k) of 0.0182 min−1 and a high correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.96, confirming excellent model conformity. Enhanced photocatalytic efficiency is attributed to synergistic effects between ZnO and CuO, efficient charge carrier separation, and increased surface reactivity imparted by alginate.

Antibacterial investigations revealed significant inhibition zones against Staphylococcus aureus (20 mm) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14 mm) at 1.00 µg/mL concentration, with inhibition efficiencies of 65.39% and 23.65%, respectively. These results validate the multifunctional nature of the synthesized nanocomposites, combining effective antimicrobial and photocatalytic properties.

In summary, the green-synthesized ZnO/CuO/Alg nanocomposites exhibit enhanced optical, structural, photocatalytic, and antibacterial performance. Their strong correlation with kinetic modeling (R2 = 0.96), excellent solar-driven dye degradation efficiency, and eco-friendly synthesis route underscore their potential for large-scale applications in wastewater treatment, antibacterial coatings, and sustainable environmental remediation technologies.