Synergistic Remediation of Cr(VI) and P-Nitrophenol Co-Contaminated Soil Using Metal-/Non-Metal-Doped nZVI Catalysts with High Dispersion in the Presence of Persulfate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

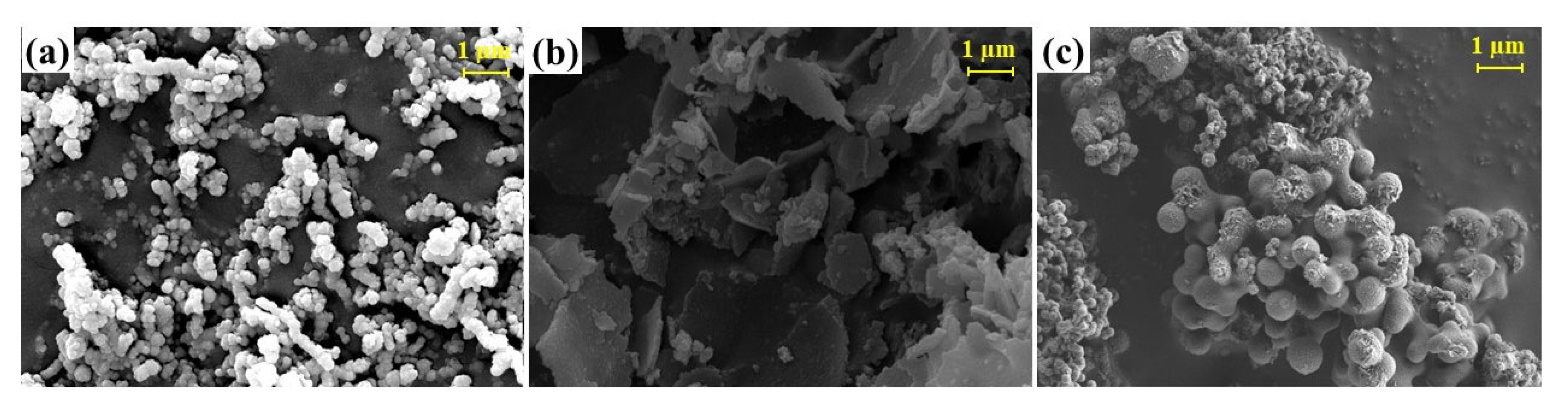

2.1. Characterization of nFe0, MMT-nFe0/Cu0 and CMS@S-nFe0

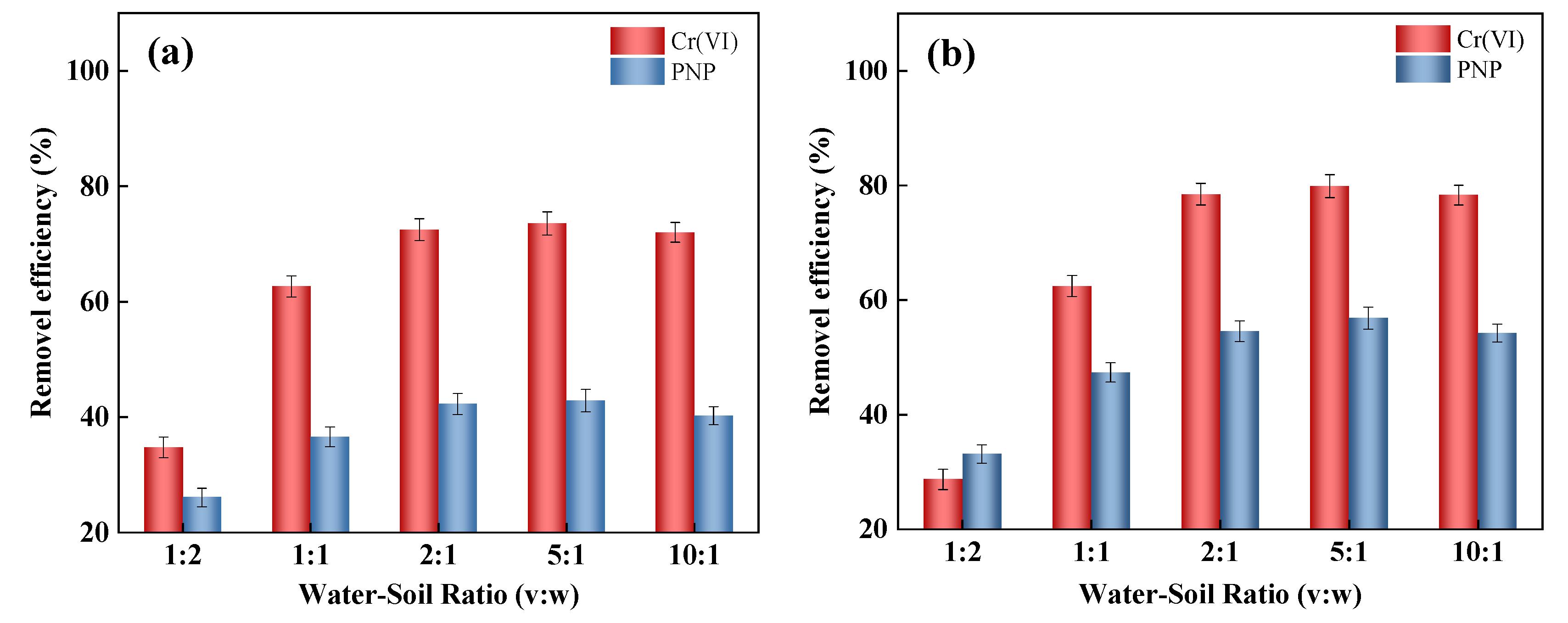

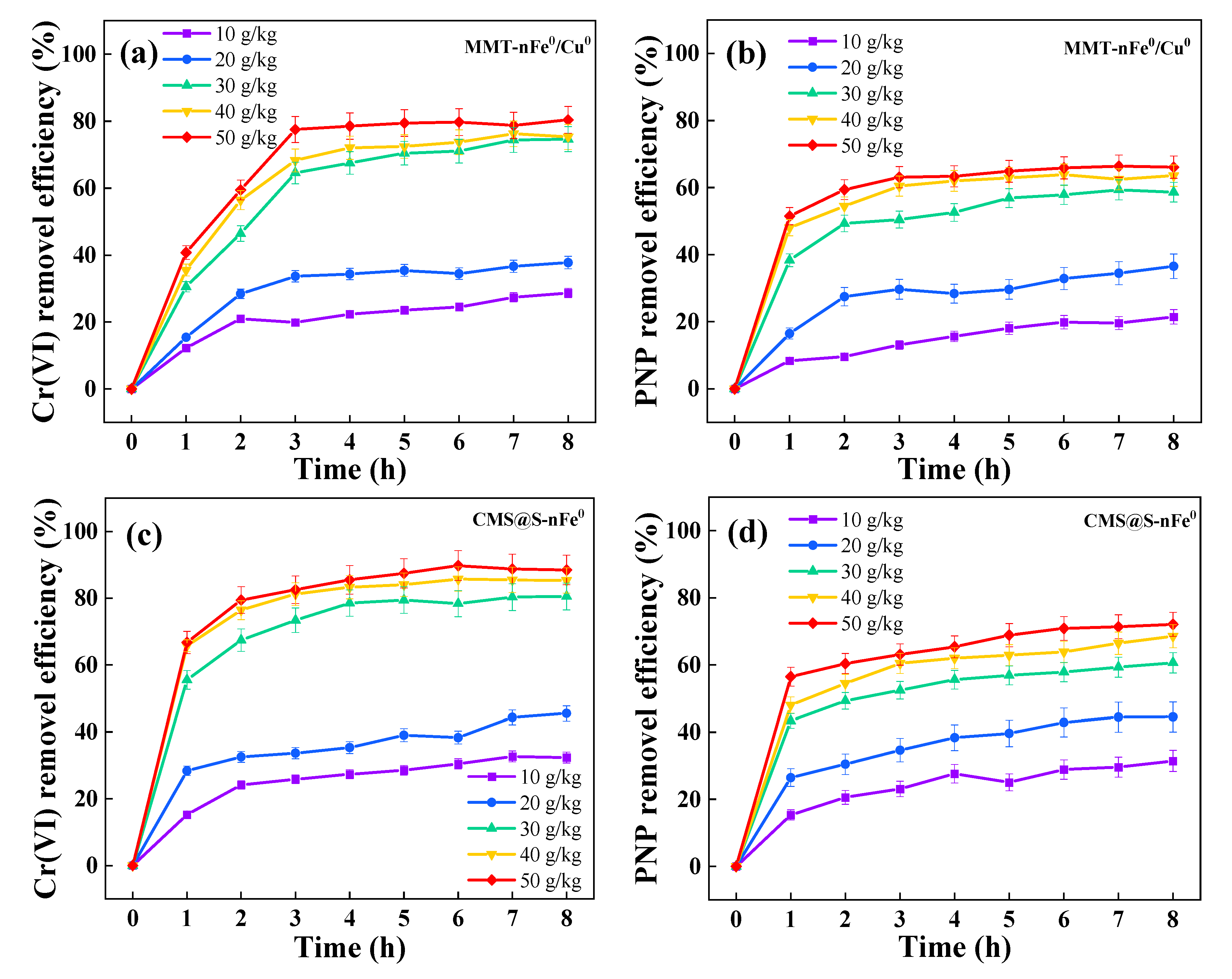

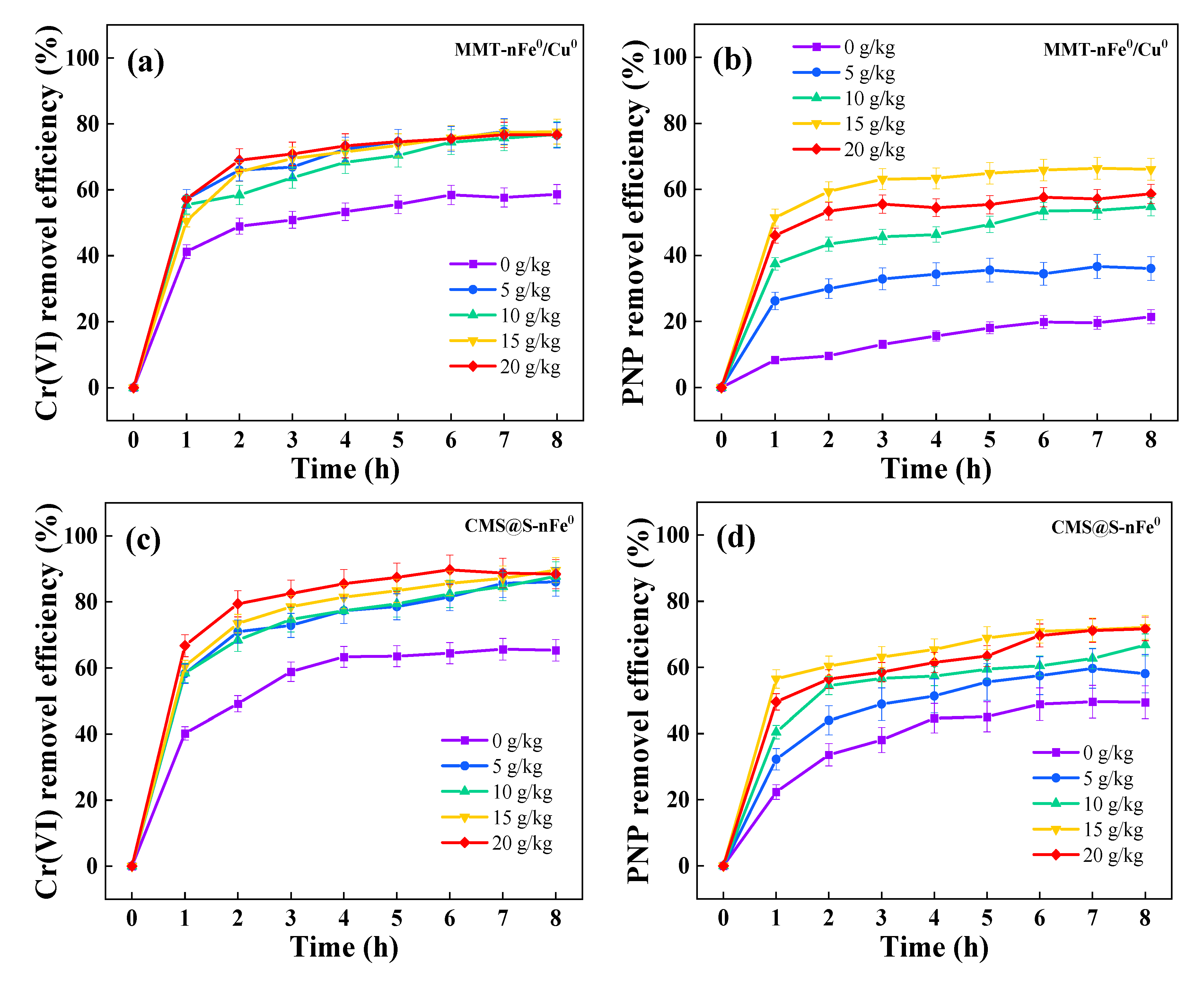

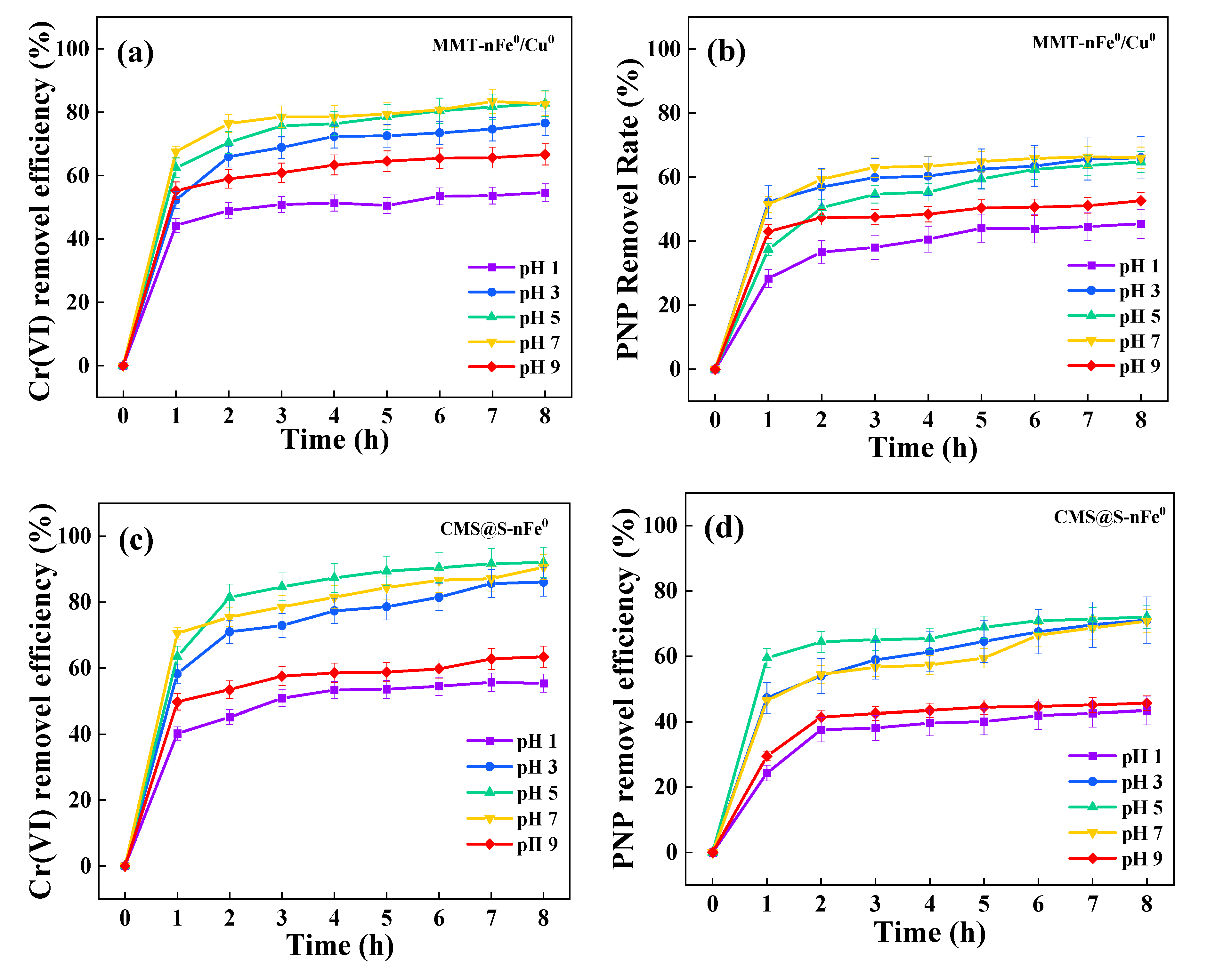

2.2. Effects of Parameters

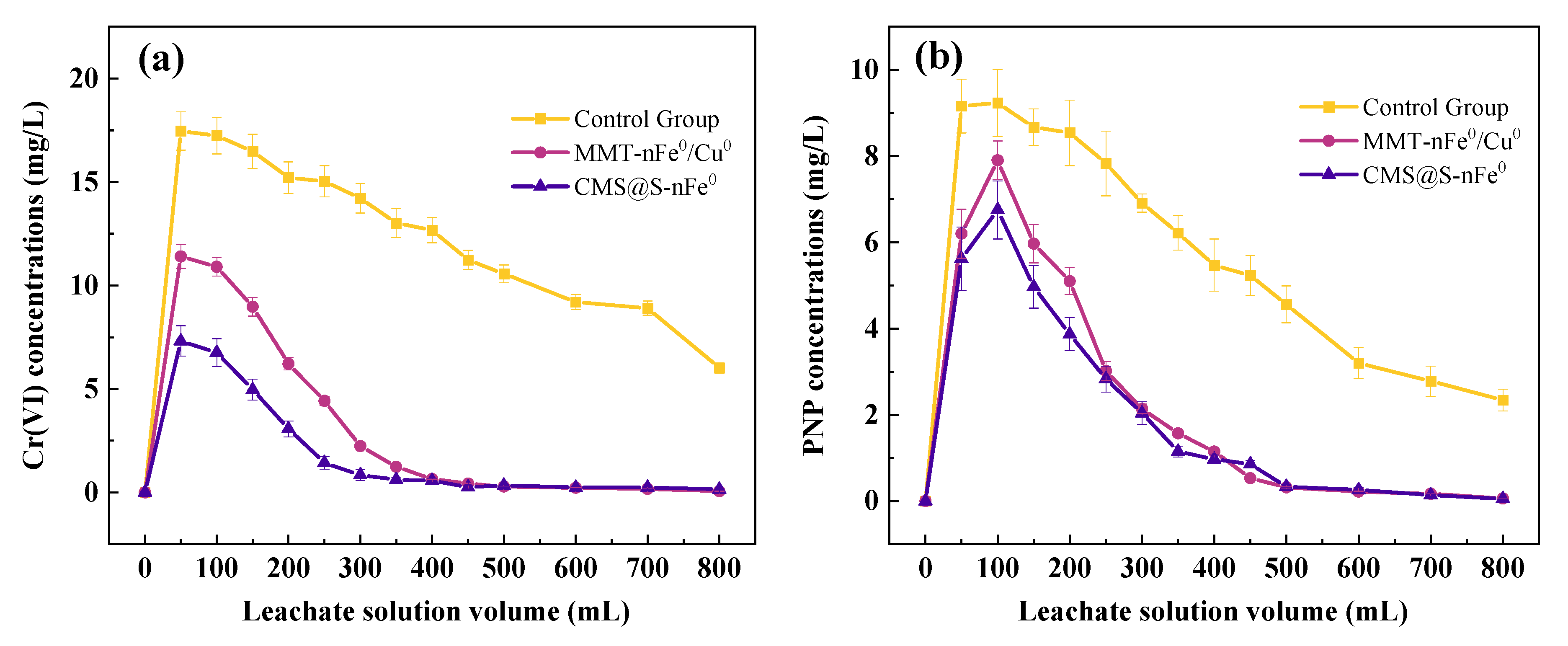

2.3. Degradation Performance in Soil Column

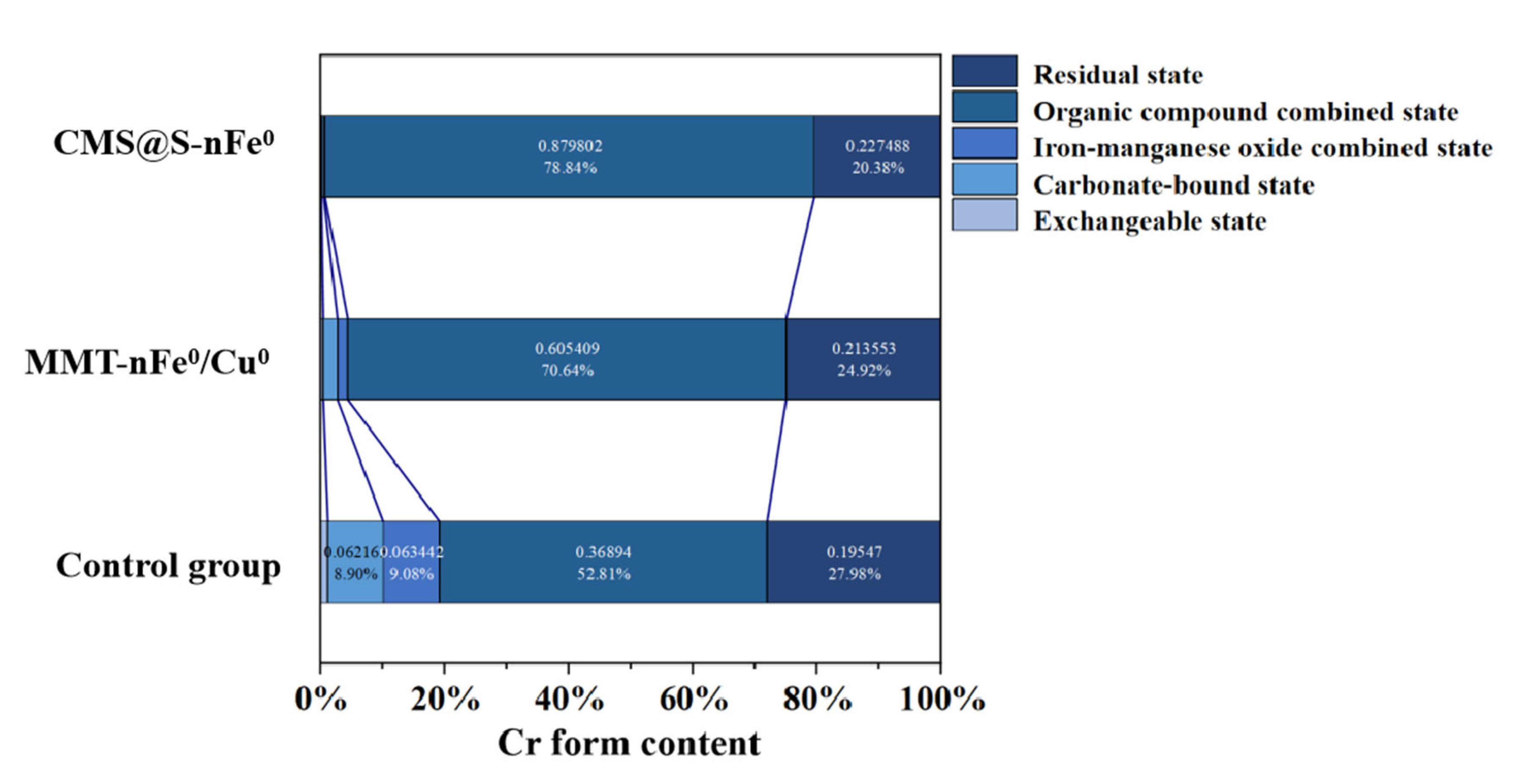

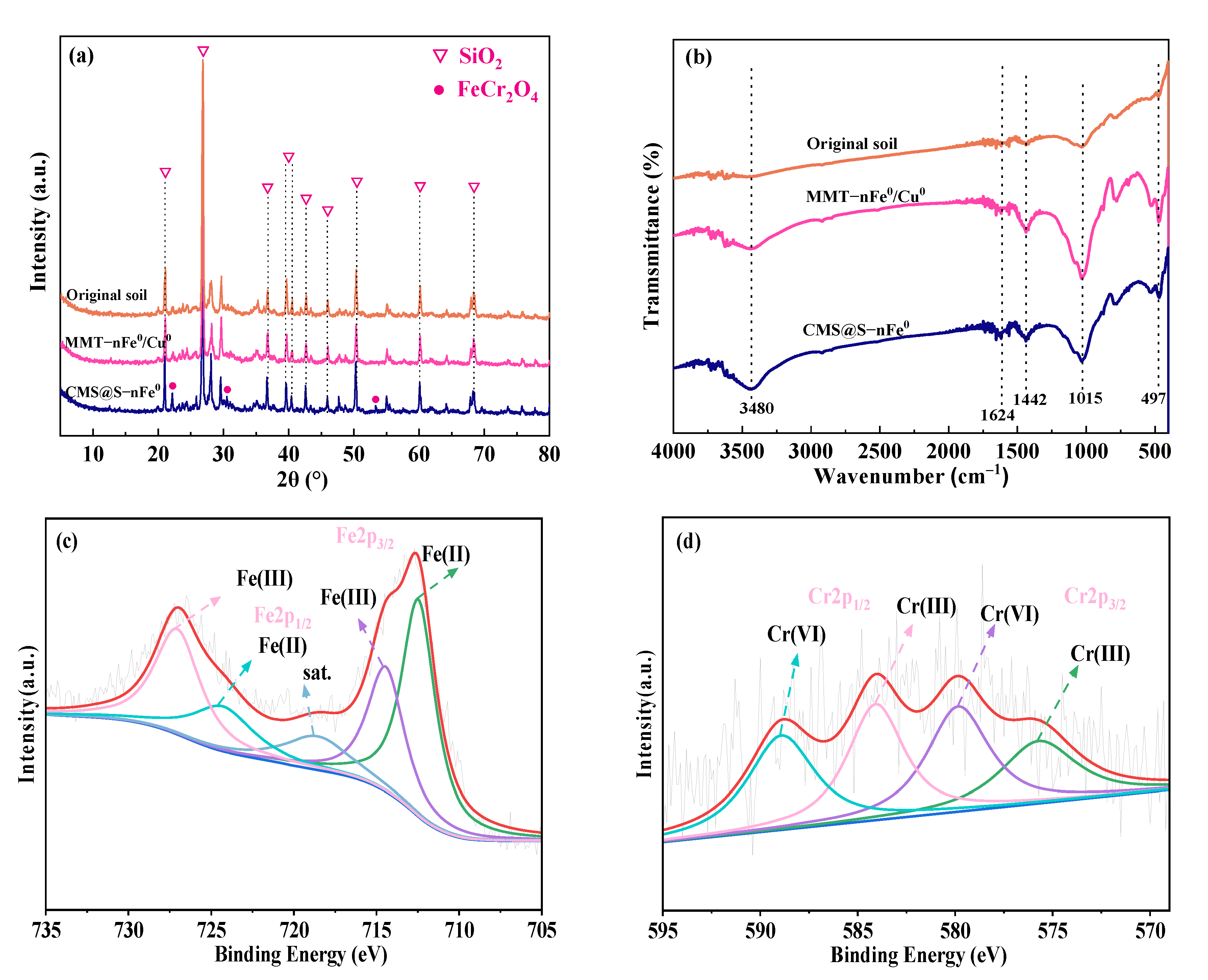

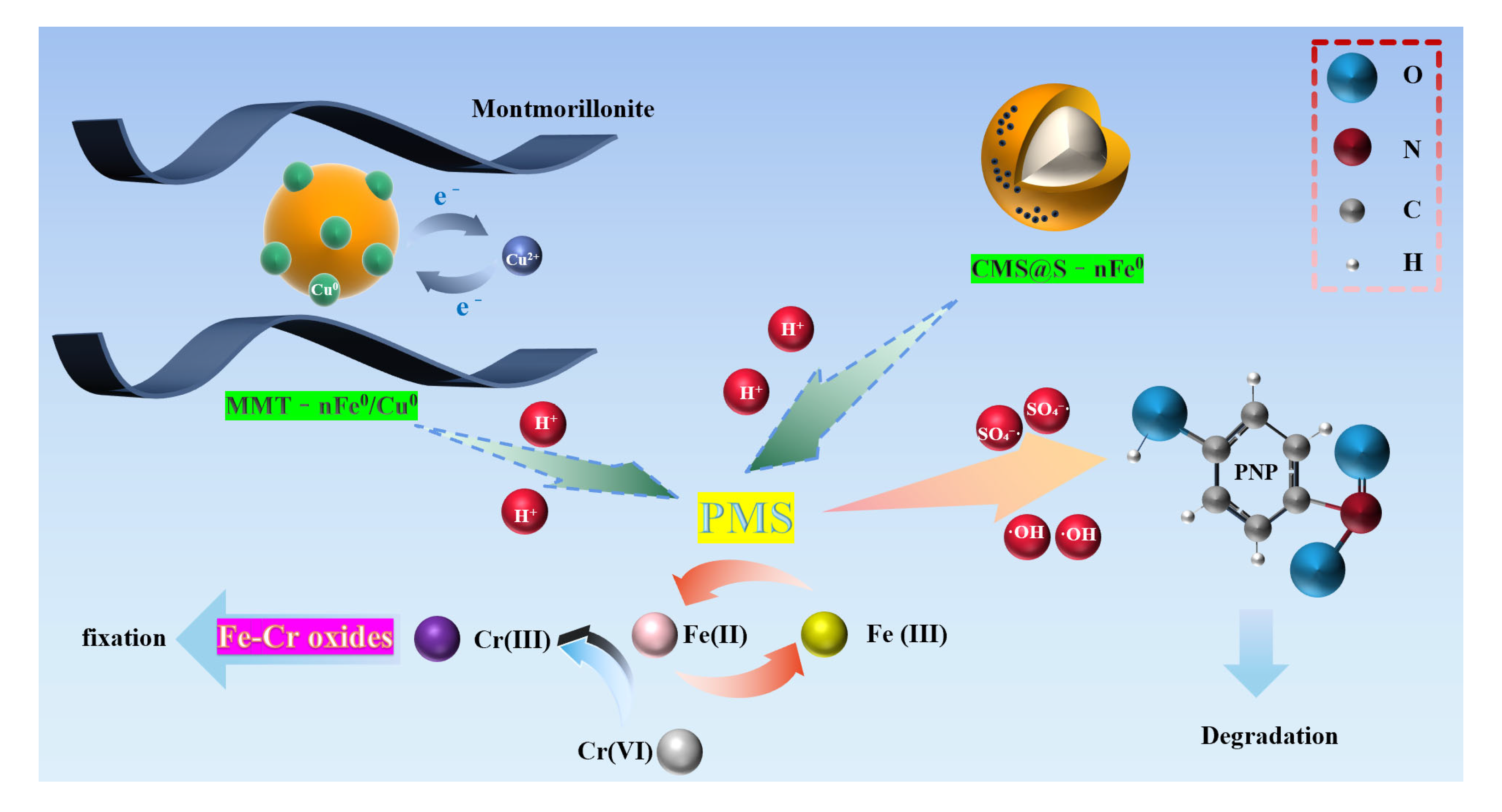

2.4. Remediation Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical and Reagents

3.2. Preparation of MMT-nFe0/Cu0 and CMS@S-nFe0

3.3. Soil Preparation

3.4. Batch Experiments

3.5. Soil Column Leaching Experiment

3.6. Characterization

3.7. Analytic Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, W.; Fu, F.; Cheng, Z.; Tang, B.; Wu, S. Studies on the Optimum Conditions Using Acid-Washed Zero-Valent Iron/Aluminum Mixtures in Permeable Reactive Barriers for the Removal of Different Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 302, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-C.; Ko, C.-H.; Tsai, M.-J.; Wang, Y.-N.; Chung, C.-Y. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil by Jatropha Curcas. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1969–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.; Pazos, M.; Figueiredo, H.; Tavares, T.; Sanromán, M.A. Desorption Kinetics of Phenanthrene and Lead from Historically Contaminated Soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 167, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Luan, Y.; Dai, W. Adsorption Behavior of Organic Pollutants on Microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yuan, Z.; Sun, S.; Xie, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhai, Y.; Zuo, R.; Bi, E.; Tao, Y.; Song, Q. Remediation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Contaminated Soil by Using Activated Persulfate with Carbonylated Activated Carbon Supported Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron. Catalysts 2024, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, W.-Y.; Guo, S.-F.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.-H.; Lu, X.-X.; Chen, F.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; Zhang, D.-E. Assembly of Anthracene-Based Donor-Acceptor Conjugated Organic Polymers for Efficient Photocatalytic Aqueous Cr(VI) Reduction and Organic Pollution Degradation under Visible Light. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 310, 123004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Huang, S.; Li, P. Exclusion of the Main Role of Oxygen Vacancy in Cu-Mn-O/N-Doped Carbon Catalysts for Activating Peroxymonosulfate to Degrade p-Nitrophenol (PNP) and Reducing PNP in Water by NaBH4. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhu, F.; Liang, W.; Hu, G.; Deng, X.; Xue, Y.; Guan, J. Simultaneous Removal of P-Nitrophenol and Cr(VI) Using Biochar Supported Green Synthetic Nano Zero Valent Iron-Copper: Mechanistic Insights and Toxicity Evaluation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 167, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xue, L.; Shi, H.; Chen, W.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, K. Simultaneous Degradation of P-Nitrophenol and Reduction of Cr(VI) in One Step Using Microwave Atmospheric Pressure Plasma. Water Res. 2022, 212, 118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Guo, A.; Xian, L.; Wang, Y.; Long, Y.; Fan, G. Facile Fabrication of Surface Vulcanized Co-Fe Spinel Oxide Nanoparticles toward Efficient 4-Nitrophenol Destruction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 128433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Cheng, Z.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Tang, B. Fe/Al Bimetallic Particles for the Fast and Highly Efficient Removal of Cr(VI) over a Wide pH Range: Performance and Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 298, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fan, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Lan, Y. Synthesis of Microscale Zinc–Copper Bimetallic Particles and Their Performance Toward p-Nitrophenol Removal: Characterization, Mineralization, and Response Surface Methodology. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2020, 37, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Elliott, D.W.; Zhang, W. Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles for Abatement of Environmental Pollutants: Materials and Engineering Aspects. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2006, 31, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zheng, D.; Ren, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xin, J. Zero-Valent Aluminum for Reductive Removal of Aqueous Pollutants over a Wide pH Range: Performance and Mechanism Especially at Near-Neutral pH. Water Res. 2017, 123, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yi, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, Z.; Tsang, E.P. Excellently Reactive Ni/Fe Bimetallic Catalyst Supported by Biochar for the Remediation of Decabromodiphenyl Contaminated Soil: Reactivity, Mechanism, Pathways and Reducing Secondary Risks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 320, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Liu, H.; Ning, X.; Zhao, D.; Fan, X. Screening for the Action Mechanisms of Fe and Ni in the Reduction of Cr(VI) by Fe/Ni Nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Zhang, B.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Xu, C. Enhanced Sequestration of Cr(VI) by Copper Doped Sulfidated Zerovalent Iron (SZVI-Cu): Characterization, Performance, and Mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Li, J.; Xiong, Z.; Lai, B. Enhanced Reactivity of Microscale Fe/Cu Bimetallic Particles (MFe/Cu) with Persulfate (PS) for p-Nitrophenol (PNP) Removal in Aqueous Solution. Chemosphere 2017, 172, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, W.; Bai, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhang, W. Selective Nitrate Reduction to Dinitrogen by Electrocatalysis on Nanoscale Iron Encapsulated in Mesoporous Carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Hussain, B.; Iqbal, N.; Salam, M.; Raza, M.M.; Pu, S. Navigating Soil Microbiota Shifts to Organic Pollutants: Insights into the Roles of nZVI-Biochar in Soil Ecosystem Restoration. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 212, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Lin, N.; Yu, L.; Du, B.; Zhang, X. Enhanced Removal of Cr(VI) from Aqueous Solution by Stabilized Nanoscale Zero Valent Iron and Copper Bimetal Intercalated Montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 606, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, W.; Yu, L.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, H. Synthesis of Carbon Microsphere-Supported Nano-Zero-Valent Iron Sulfide for Enhanced Removal of Cr(VI) and p-Nitrophenol Complex Contamination in Peroxymonosulfate System. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.F.A.; Jalil, A.A.; Hassan, N.S.; Hitam, C.N.C.; Rahman, A.F.A.; Fauzi, A.A. Enhanced Visible-Light Driven Multi-Photoredox Cr(VI) and p-Cresol by Si and Zr Interplay in Fibrous Silica-Zirconia. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 401, 123277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Bingham, P.A.; Tanaka, M.; Li, W.; Kubuki, S. BiOBr/MoS2 Catalyst as Heterogenous Peroxymonosulfate Activator toward Organic Pollutant Removal: Energy Band Alignment and Mechanism Insight. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 594, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Lin, N.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Oxygen-Deficient Engineering for Perovskite Oxides in the Application of AOPs: Regulation, Detection, and Reduction Mechanism. Catalysts 2023, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Cui, T.; et al. Electron Transfer Enhancing Fe(II)/Fe(III) Cycle by Sulfur and Biochar in Magnetic FeS@biochar to Active Peroxymonosulfate for 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Nengzi, L.; Zhang, X.; Gou, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, G.; Cheng, Q.; Cheng, X. Catalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin by Magnetic CuS/Fe2O3/Mn2O3 Nanocomposite Activated Peroxymonosulfate: Influence Factors, Degradation Pathways and Reaction Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ji, G.; Li, A. Degradation of Antibiotic Pollutants by Persulfate Activated with Various Carbon Materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ke, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Cai, Y.; He, L. Systemic Assessment of Fenpropathrin and 3-Phenoxybenzoic Acid in Soil: Adsorption, Desorption, and Effects on Soil Enzyme and Microbial Community. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 212, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bi, F.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, N. The Promoting Effect of H2O on Rod-like MnCeOx Derived from MOFs for Toluene Oxidation: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Investigation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 297, 120393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Hu, P.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, W. Removal of Cadmium(II) from Aqueous Solutions by a Novel Sulfide-Modified Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron Supported on Kaolinite: Treatment Efficiency, Kinetics and Mechanisms. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 602, 154353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; She, D.; Ju, X.; Cao, T.; Xia, Y. Revealing Soil Hydraulic Parameters via X–Ray Tomography Depends on the Relationship between Soil Pore Structure and Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 60, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xiang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Du, R.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F. Improving Surface Soil Moisture Content Estimation of Winter Oilseed Rape by Integrating Multimodal Remote Sensing Information and Structural Characteristics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, S.M.Z.; Iqbal, J. Estimation of Soil Moisture Using Multispectral and FTIR Techniques. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2015, 18, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, R.; Wei, X.; Peng, S. Cobalt Oxide/Polypyrrole Derived Co/NC to Activate Peroxymonosulfate for Benzothiazole Degradation: Enhanced Conversion Efficiency of PMS to Free Radicals. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Lei, H. Degradation of P-Nitrophenol through Microwave-Assisted Heterogeneous Activation of Peroxymonosulfate by Manganese Ferrite. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 287, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wei, X.; Yin, H.; Zhu, M.; Luo, H.; Dang, Z. Synergistic Removal of Cr(VI) by S-nZVI and Organic Acids: The Enhanced Electron Selectivity and pH-Dependent Promotion Mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Kawase, Y. Effect of Solution PH on Removal of Anionic Surfactant Sodium Dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS) from Model Wastewater Using Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron (nZVI). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Sheng, Y. New Insights into the Degradation of Chloramphenicol and Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics by Peroxymonosulfate Activated with FeS: Performance and Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sut-Lohmann, M.; Ramezany, S.; Kästner, F.; Raab, T.; Heinrich, M.; Grimm, M. Using Modified Tessier Sequential Extraction to Specify Potentially Toxic Metals at a Former Sewage Farm. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Yu, D.; Yang, J.; Zhao, T.; Yu, D.; Li, L.; Wang, D. A Novel Sequential Extraction Method for the Measurement of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) Species Distribution in Soil: New Insights into the Chromium Speciation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 135864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Yadav, S. Investigations of Metal Leaching from Mobile Phone Parts Using TCLP and WET Methods. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wang, C. Adsorption and Dechlorination of 2,4-Dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP) on a Multi-Functional Organo-Smectite Templated Zero-Valent Iron Composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 191, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Li, Z.; Hu, B.; Wang, L.; Wu, M. Unravelling the Role of Strong Metal-Support Interactions in Boosting the Activity toward Hydrogen Evolution Reaction on Ir Nanoparticle/N-Doped Carbon Nanosheet Catalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 22448–22456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Chu, S.; Yang, B.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Yan, X.; Galvita, V.V.; et al. Efficient Removal and Transformation of Cr(VI) from Alkaline Wastewater to Form a Ferrochromium Spinel Multiphase via a Modified Ferrite Process. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Du, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ye, H.; Chen, S.; Zhang, T.C. Efficient Reduction of Cr(VI) and Recovery of Fe from Chromite Ore Processing Residue by Waste Biomass. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Ye, J.; Dong, S.; Zeng, Z.; Tang, D.; Wang, X.; Chen, S. New Insights into the Mechanism for Fe Coordination Promoting Photocatalytic Reduction of Cr(VI) by Graphitic Carbon Nitride: The Boosted Transformation of Cr(V) to Cr(III). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 679, 161142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.-X.; Yan, L.; Zhou, X.-H.; Huang, S.-T.; Liang, J.-Y.; Zhang, W.-X.; Guo, Z.-W.; Guo, P.-R.; Qian, W.; Kong, L.-J.; et al. Simultaneous Adsorption of Cr(VI) and Phenol by Biochar-Based Iron Oxide Composites in Water: Performance, Kinetics and Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X.; Xie, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Tian, J.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Electron Transfer Enhancing Fe2+/Fe3+ Cycle by Persistent Free Radicals (PFRs) Contained Biochars to Active H2O2 for PNP Degradation. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 107344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Li, J.; Shao, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Adsorption of Copper(II) on Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in the Absence and Presence of Humic or Fulvic Acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 178, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Cui, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Li, X. Reductive Immobilization of Cr(VI) during Fe(II)-Induced Vivianite Organo-Mineral Dissolution and Recrystallization: Kinetic and Mechanistic Investigations. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, B.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zeng, K.; Zhang, L.; Sun, H.; Ai, Z. Phosphorylated Zerovalent Iron Boosts Active Hydrogen Species Generation from Water Dissociation for Superior Hg(II) Reduction. Water Res. 2025, 283, 123787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, K.J.; Kaplan, D.I.; Wietsma, T.W. Zero-Valent Iron for the in Situ Remediation of Selected Metals in Groundwater. J. Hazard. Mater. 1995, 42, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Lu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Cr(VI) Removal by nZVI: Influencing Parameters and Modification. Catalysts 2022, 12, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhao, D.; Wu, C.; Xie, R. Sulfidized Nanoscale Zerovalent Iron Supported by Oyster Powder for Efficient Removal of Cr (VI): Characterization, Performance, and Mechanisms. Materials 2022, 15, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X. Synergistic Remediation of Cr(VI) and P-Nitrophenol Co-Contaminated Soil Using Metal-/Non-Metal-Doped nZVI Catalysts with High Dispersion in the Presence of Persulfate. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111077

Wang Y, Xu S, Yang Y, Gao Y, Lu L, Jiang H, Zhang X. Synergistic Remediation of Cr(VI) and P-Nitrophenol Co-Contaminated Soil Using Metal-/Non-Metal-Doped nZVI Catalysts with High Dispersion in the Presence of Persulfate. Catalysts. 2025; 15(11):1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111077

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yin, Siqi Xu, Yixin Yang, Yule Gao, Linlang Lu, Hu Jiang, and Xiaodong Zhang. 2025. "Synergistic Remediation of Cr(VI) and P-Nitrophenol Co-Contaminated Soil Using Metal-/Non-Metal-Doped nZVI Catalysts with High Dispersion in the Presence of Persulfate" Catalysts 15, no. 11: 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111077

APA StyleWang, Y., Xu, S., Yang, Y., Gao, Y., Lu, L., Jiang, H., & Zhang, X. (2025). Synergistic Remediation of Cr(VI) and P-Nitrophenol Co-Contaminated Soil Using Metal-/Non-Metal-Doped nZVI Catalysts with High Dispersion in the Presence of Persulfate. Catalysts, 15(11), 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111077