Development of a Au/TiO2/Ti Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in a Bicarbonate Medium

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Surface Characterization

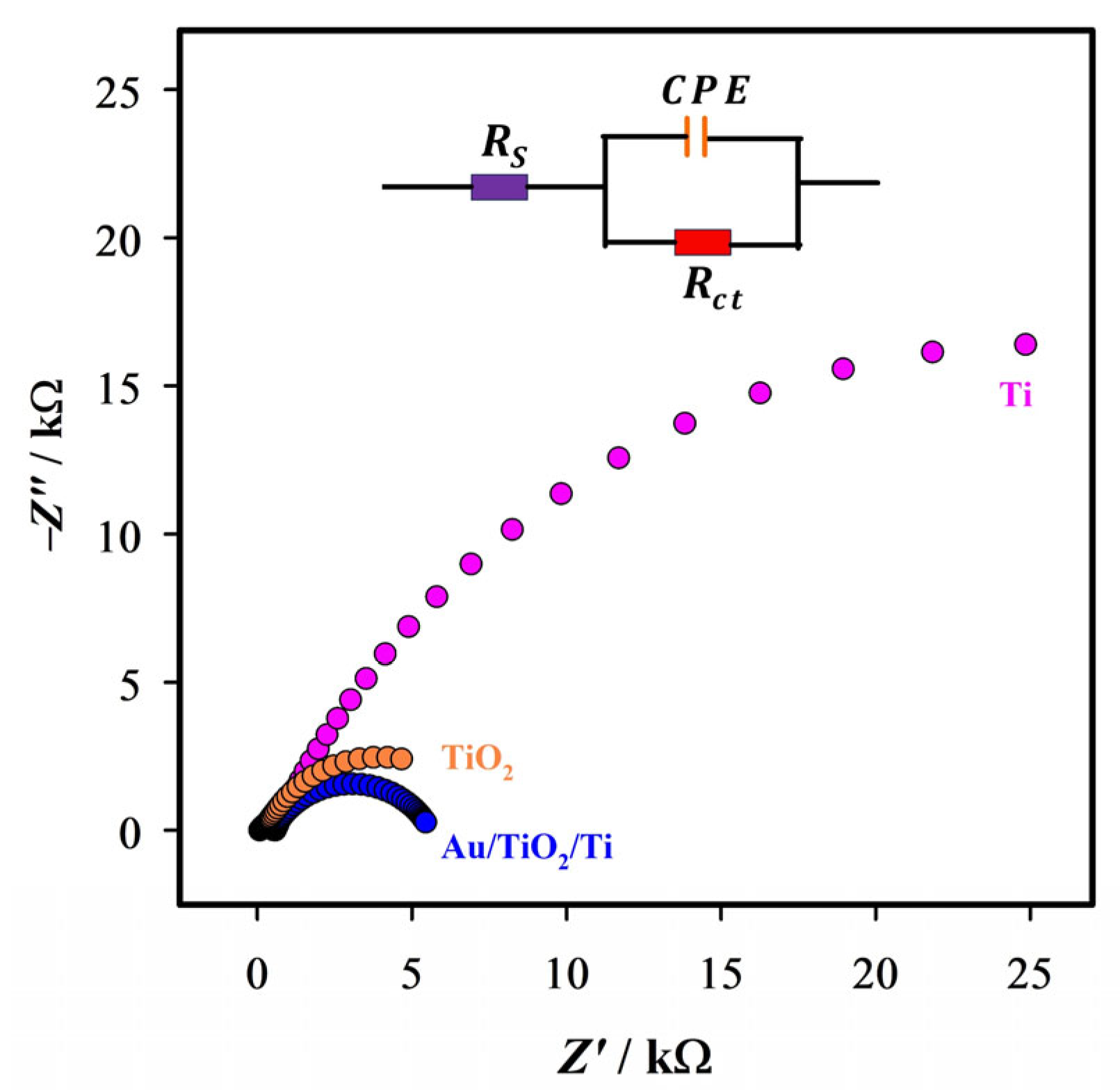

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization

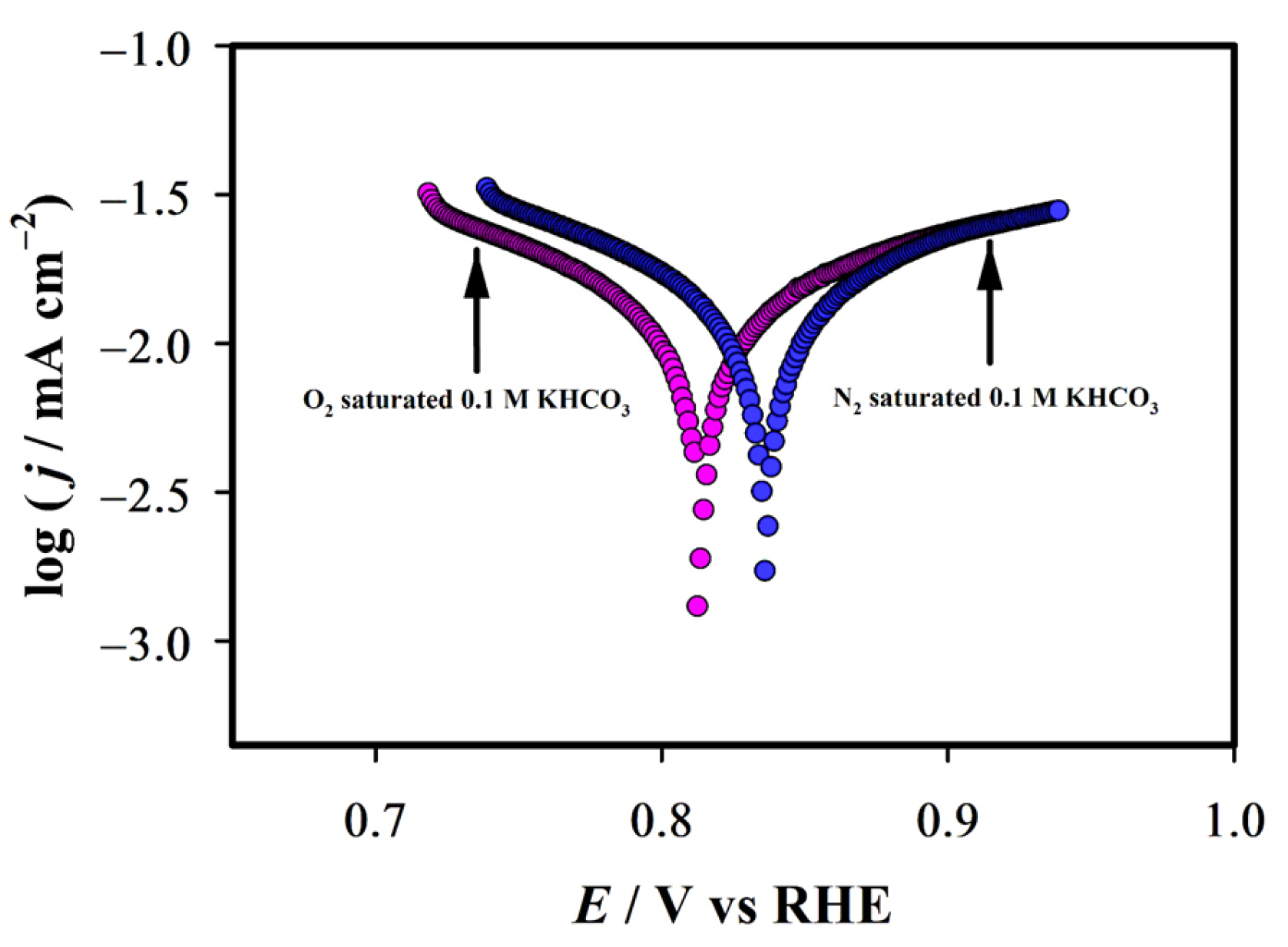

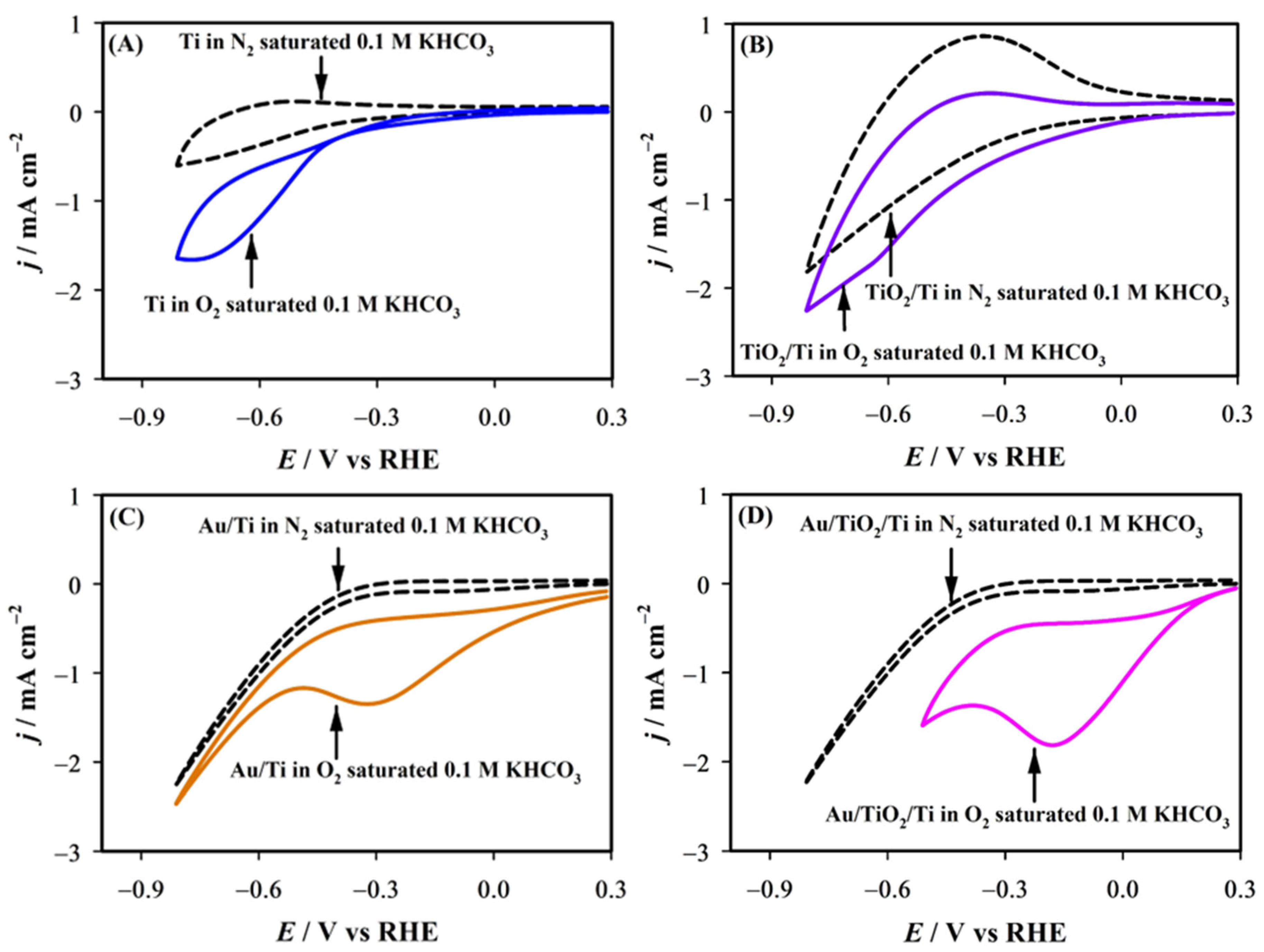

2.3. Catalytic Activity

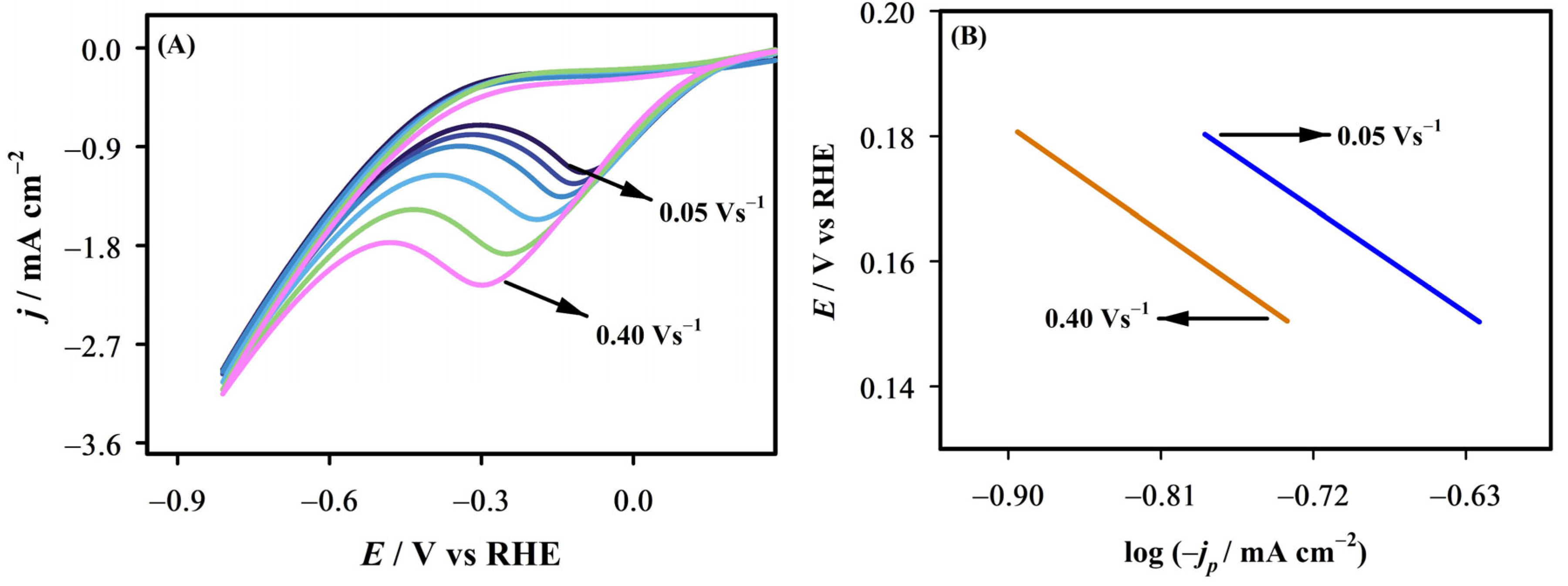

2.4. Scan Rate Effect

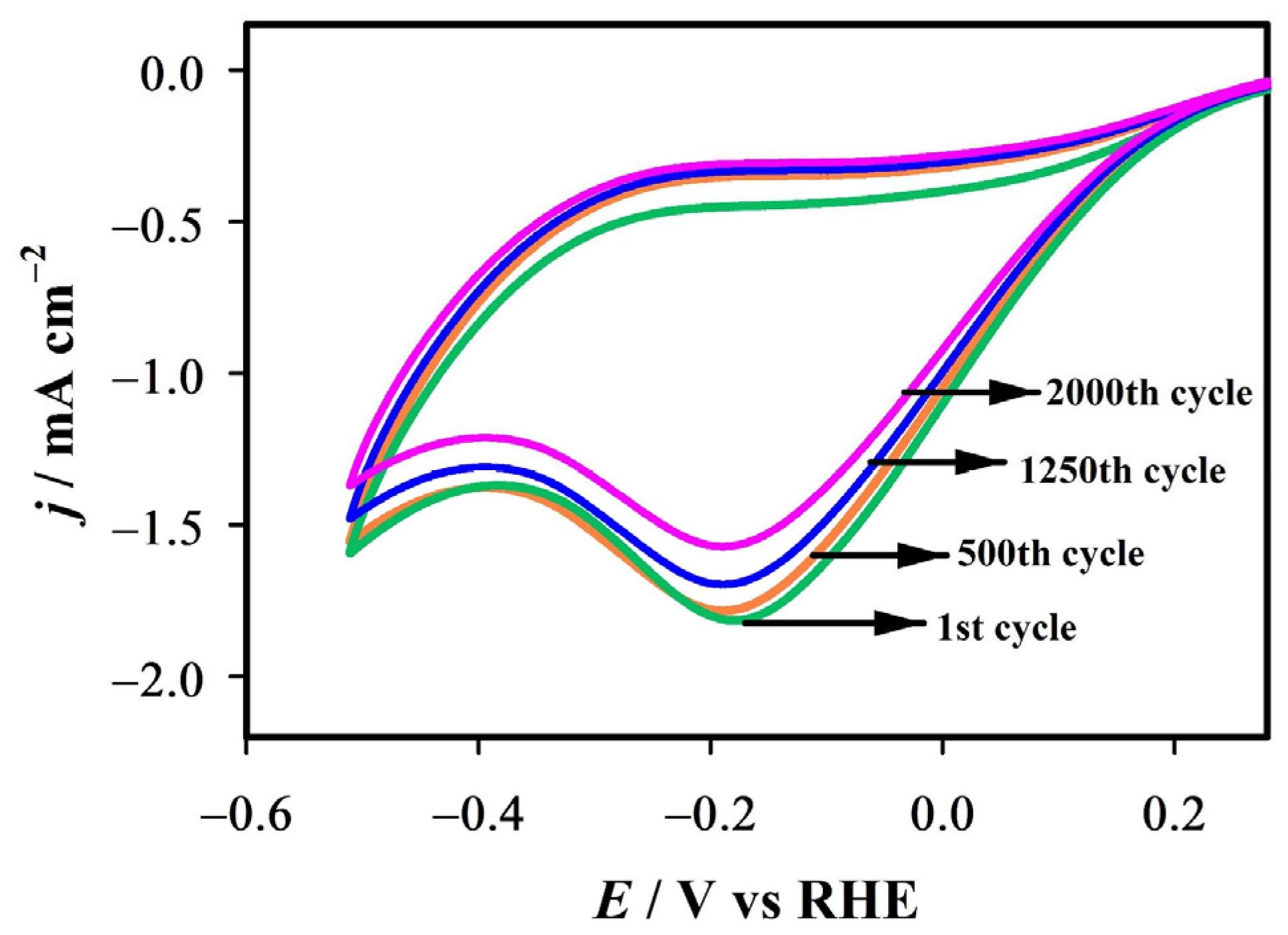

2.5. Stability Evaluation

3. Experimental

3.1. Chemicals and Instruments

3.2. Electrode Fabrication

3.2.1. Synthesis of TiO2 Layer on Ti Sheet

3.2.2. Au/Ti Electrode Fabrication

3.2.3. Au/TiO2/Ti Electrode Fabrication

3.3. Surface Properties Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pablo-Romero, P.; Pozo-Barajas, R.; Sánchez, J.; García, R.; Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A Global Assessment: Can Renewable Energy Replace Fossil Fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Khan, A.; Zhou, K. The Impact of Natural Resource Depletion on Energy Use and CO2 Emission in Belt & Road Initiative Countries: A Cross-Country Analysis. Energy 2020, 199, 117409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Usman, M. Energy Use, Energy Depletion, and Environmental Degradation: Exploitation of Natural Resources. Nat. Resour. Forum 2025, 49, 3984–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Azam, W. Natural Resource Scarcity, Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption, and Total Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Top Emitting Countries. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Cherian, J.; Sial, M.S.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Comite, U.; Zia-Ud-Din, M. Green Bond as a New Determinant of Sustainable Green Financing, Energy Efficiency Investment, and Economic Growth: A Global Perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 61324–61339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chau, K.Y.; Tran, T.K.; Sadiq, M.; Xuyen, N.T.M.; Phan, T.T.H. Enhancing Green Economic Recovery through Green Bonds Financing and Energy Efficiency Investments. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 76, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, D.; Boshell, F.; Saygin, D.; Bazilian, M.D.; Wagner, N.; Gorini, R. The Role of Renewable Energy in the Global Energy Transformation. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letchumanan, I.; Mohamad Yunus, R.; Mastar@Masdar, M.S.; Karim, N.A. Advancements in Electrocatalyst Architecture for Enhanced Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 104, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, J. Operando Characterization Techniques for Electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3748–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kou, Z.; Cai, W.; Zhou, H.; Ji, P.; Liu, B.; Radwan, A.; He, D.; Mu, S. P–Fe Bond Oxygen Reduction Catalysts toward High-Efficiency Metal–Air Batteries and Fuel Cells. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2020, 8, 9121–9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ji, S.; Zhao, S.; Chen, W.; Dong, J.; Cheong, W.C.; Shen, R.; Wen, X.; Zheng, L.; Rykov, A.I.; et al. Enhanced Oxygen Reduction with Single-Atomic-Site Iron Catalysts for a Zinc-Air Battery and Hydrogen-Air Fuel Cell. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanli, A.E.; Aytaç, A. Response to Disselkamp: Direct Peroxide/Peroxide Fuel Cell as a Novel Type Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zhao, T.; Yan, X.; Zhou, X.; Tan, P. The Dual Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Fuel Cells. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miley, G.H.; Luo, N.; Mather, J.; Burton, R.; Hawkins, G.; Gu, L.; Byrd, E.; Gimlin, R.; Shrestha, P.J.; Benavides, G.; et al. Direct NaBH4/H2O2 Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zhao, T.S.; Xu, J.B. A Bi-Functional Cathode Structure for Alkaline-Acid Direct Ethanol Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 13089–13095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Fukunishi, Y.; Yamazaki, S.I.; Fukuzumi, S. Hydrogen Peroxide as Sustainable Fuel: Electrocatalysts for Production with a Solar Cell and Decomposition with a Fuel Cell. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7334–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Miley, G.H.; Kim, K.J.; Burton, R.; Huang, X. NaBH4/H2O2 Fuel Cells for Air Independent Power Systems. J. Power Sources 2008, 185, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Meng, F.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y. Direct N2H4/H2O2 Fuel Cells Powered by Nanoporous Gold Leaves. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Wang, E.; Jiang, L.; Tang, Q.; Sun, G. Studies on Palladium Coated Titanium Foams Cathode for Mg–H2O2 Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2012, 208, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurnobi Islam, M.; Abir, A.Y.; Ahmed, J.; Faisal, M.; Algethami, J.S.; Harraz, F.A.; Hasnat, M.A. Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction Reaction at FeS2-CNT/GCE Surface in Alkaline Medium. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 941, 117568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pakhira, S. Synergistic Niobium Doped Two-Dimensional Zirconium Diselenide: An Efficient Electrocatalyst for O2 Reduction Reaction. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2024, 4, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D.; Dang, D.; Deng, Y.; et al. Oxygen-Coordinated Cr Single-Atom Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Angew. Chem.—Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202500500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Pan, Z.; Hu, S.; Kim, J.H. Cathodic Hydrogen Peroxide Electrosynthesis Using Anthraquinone Modified Carbon Nitride on Gas Diffusion Electrode. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 7972–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, W.; Lu, Z.; Sun, J. Recent Progress on Carbonaceous Material Engineering for Electrochemical Hydrogen Peroxide Generation. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2020, 26, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Xia, C.; Wang, H.F.; Tang, C. Recent Advances in Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction for On-Site Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis in Acidic Media. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 67, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Vagin, M.; Boyd, R.; Ding, P.; Leanderson, P.; Kozyatnyk, I.; Greczynski, G.; Odén, M.; Björk, E.M. Effect of Product Removal in Hydrogen Peroxide Electrosynthesis on Mesoporous Chromium(III) Oxide. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 18748–18756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y. Recent Advances in Electrosynthesis of H2O2 via Two-Electron Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 5232–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Gu, W.; Cai, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, C. Highly-Defective Fe-N-C Catalysts towards PH-Universal Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Appl. Catal. B 2020, 263, 118347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; He, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, D.; Mu, S.; Yang, H.Y. Defect and Doping Co-Engineered Non-Metal Nanocarbon ORR Electrocatalyst. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ma, N.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, D.; Cao, K.; Feng, F.; Gao, D.; Liu, R.; Li, S.; et al. Atomically Engineered Defect-Rich Palladium Metallene for High-Performance Alkaline Oxygen Reduction Electrocatalysis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2405187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, G.; Jana, R.; Saifi, S.; Kumar, R.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Datta, A.; Sinha, A.S.K.; Aijaz, A. Dual Single-Atomic Co-Mn Sites in Metal-Organic-Framework-Derived N-Doped Nanoporous Carbon for Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 19155–19167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, G.L.; Sun, C.J.; Xu, M.; Wen, W.; Wang, Q.; Gu, M.; Zhu, S.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z.; et al. Nitrogen-Coordinated Single Iron Atom Catalysts Derived from Metal Organic Frameworks for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Nano Energy 2019, 61, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Geng, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, N.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.; Lu, J. Metal-Organic Framework-Derived Fe/Fe3C Embedded in N-Doped Carbon as a Highly Efficient Oxygen Reduction Catalyst for Microbial Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 278, 118906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, N.; Xia, J.; Zhou, S.; Qian, X.; Yin, F.; He, G.; Chen, H. Metal–Organic Framework-Derived Co Single Atoms Anchored on N-Doped Hierarchically Porous Carbon as a PH-Universal ORR Electrocatalyst for Zn–Air Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2023, 11, 2291–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiido, K.; Alexeyeva, N.; Couillard, M.; Bock, C.; MacDougall, B.R.; Tammeveski, K. Graphene–TiO2 Composite Supported Pt Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 107, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.M.; Im, K.; Kim, J. A Highly Stable Tungsten-Doped TiO2-Supported Platinum Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Acidic Media. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 611, 155740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Patil, S.S.; Yu, S.; Lee, W.; Lee, K. Electrochemical Characteristic Assessments toward 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene Using Anodic TiO2 Nanotube Arrays. Electrochem. Commun 2022, 135, 107214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.-X.; Miao, J.; Wang, H.-Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, B. Electrochemical Construction of Hierarchically Ordered CdSe-Sensitized TiO2 Nanotube Arrays: Towards Versatile Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting and Photoredox Applications. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6727–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peighambardoust, N.S.; Khameneh Asl, S.; Mohammadpour, R.; Asl, S.K. Band-Gap Narrowing and Electrochemical Properties in N-Doped and Reduced Anodic TiO2 Nanotube Arrays. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 270, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hoffmann, M.R. Synthesis and Stabilization of Blue-Black TiO2 Nanotube Arrays for Electrochemical Oxidant Generation and Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11888–11894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Akalework, N.G.; Pan, C.J.; Rick, J.; Liao, Y.F.; Su, W.N.; Hwang, B.J. Interplay between Molybdenum Dopant and Oxygen Vacancies in a TiO2 Support Enhances the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6551–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, M.; Hosen, N.; Althomali, R.H.; Al-Humaidi, J.Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Hasnat, M.A. Kinetics of Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction Reaction over an Activated Glassy Carbon Electrode in an Alkaline Medium. Catalysts 2024, 14, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.N.; Anitha, V.C.; Joo, S.W. Improved Electrochemical Properties of Morphology-Controlled Titania/Titanate Nanostructures Prepared by in-Situ Hydrothermal Surface Modification of Self-Source Ti Substrate for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Loew, A.; Sun, S. Surface- and Structure-Dependent Catalytic Activity of Au Nanoparticles for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Hasan, M.M.; Shabik, M.F.; Islam, F.; Nagao, Y.; Hasnat, M.A. Electroless Deposition of Gold Nanoparticles on a Glassy Carbon Surface to Attain Methylene Blue Degradation via Oxygen Reduction Reactions. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 360, 136966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.; Pham-Cong, D.; Choi, H.S.; Jeong, S.Y.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.P.; Bae, J.S.; Cho, C.R. Bandgap-Designed TiO2/SnO2 Hollow Hierarchical Nanofibers: Synthesis, Properties, and Their Photocatalytic Mechanism. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2016, 16, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, P.; Shipochka, M.; Stefchev, P.; Raicheva, Z.; Lazarova, V.; Spassov, L. XPS Characterization of TiO2 Layers Deposited on Quartz Plates. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 100, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinh, V.D.; Broggi, A.; Di Palma, L.; Scarsella, M.; Speranza, G.; Vilardi, G.; Thang, P.N. XPS Spectra Analysis of Ti2+, Ti3+ Ions and Dye Photodegradation Evaluation of Titania-Silica Mixed Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrawati, D.; Syarif, N.; Rohendi, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Amorphous TiO2 Anode Prepared by Anodizing Method for Na-Ion Batteries. Indones. J. Fundam. Appl. Chem. 2021, 6, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Xue, D. Crystallization of Amorphous Anodized TiO2 Nanotube Arrays. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 8195–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kužel, R.; Nichtová, L.; Matěj, Z.; Hubička, Z.; Buršík, J. X-Ray Diffraction Investigations of TiO2 Thin Films and Their Thermal Stability. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2012, 1352, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, G.; Song, X.; Sun, Z. Morphology and Microstructure of As-Synthesized Anodic TiO2 Nanotube Arrays. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.L.; Rosenberger, M.R.; Schvezov, C.E.; Ares, A.E. Fabrication of TiO2 Crystalline Coatings by Combining Ti-6Al-4V Anodic Oxidation and Heat Treatments. Int. J. Biomater. 2015, 2015, 395657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarek, M.; Holdynski, M.; Roguska, A.; Kudelski, A.; Janik-Czachor, M. TiO2and Al2O3nanoporous Oxide Layers Decorated with Silver Nanoparticles—Active Substrates for SERS Measurements. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2014, 18, 3099–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi Tadi, A.; Farhadiannezhad, M.; Nezamtaheri, M.S.; Goliaei, B.; Nowrouzi, A. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles from Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad Pulp Ethanolic Extract: Their Cytotoxic, Genotoxic, Apoptotic, and Antioxidant Activities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.F.; Islam, M.T.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Nagao, Y.; Hasnat, M.A. Facile Fabrication of GCE/Nafion/Ni Composite, a Robust Platform to Detect Hydrogen Peroxide in Basic Medium via Oxidation Reaction. Talanta 2022, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.F.; Shahriar, M.H.; Rahaman, M.; Aoki, K.; Nagao, Y.; Aldalbahi, A.; Uddin, J.; Hasnat, M.A. Electrokinetics of Nitrite to Ammonia Conversion in the Neutral Medium Over A Platinum Surface. Chem. Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Ahmed, J.; Rashid, K.H.; Aoki, K.; Nagao, Y.; Faisal, M.; Algethami, J.S.; Harraz, F.A.; Hasnat, M.A. Theoretical Insights into Enhanced Electrocatalytic Arsenic Oxidation on Au-Decorated Pt Surfaces in Neutral Medium. Chem. Asian J. 2025, e00682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtarin, Z.; Rahman, M.M.; Marwani, H.M.; Hasnat, M.A. Electro-Kinetics of Conversion of NO3− into NO2− and Sensing of Nitrate Ions via Reduction Reactions at Copper Immobilized Platinum Surface in the Neutral Medium. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 346, 135994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinagawa, T.; Garcia-Esparza, A.T.; Takanabe, K. Insight on Tafel Slopes from a Microkinetic Analysis of Aqueous Electrocatalysis for Energy Conversion. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, B.H.; Begum, H.; Ibrahim, F.A.; Hamdy, M.S.; Oyshi, T.A.; Khatun, N.; Hasnat, M.A. Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction from Acetic Acid over Gold Immobilized Glassy Carbon Surface. Catalysts 2023, 13, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjaktarević, D.R.; Cvijović-Alagić, I.; Dimić, I.D.; Đokić, V.R.; Rakin, M.P. Anodization of Ti-Based Materials for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Metall. Mater. Eng. 2016, 22, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Atomic % | Atomic % Error | Weight % | Weight % Error | Net Counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | 14.8 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 86 |

| C * | 7.9 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 131 |

| Ti | 70.8 | 0.9 | 67.7 | 0.9 | 9 825 |

| Au | 6.5 | 0.7 | 25.7 | 2.9 | 440 |

| Electrodes | Rs/Ω | Rct/kΩ | CPE/µMho |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti | 571 | 36.6 | 27 |

| TiO2 | 515 | 7.55 | 145 |

| Au/TiO2/Ti | 507 | 3.80 | 25.2 |

| Electrode | Ei/V vs. RHE | Ep/V vs. RHE | jp/mA cm−2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare Ti | −0.38 | −0.78 | 1.63 |

| TiO2/Ti | - | - | - |

| Au/Ti | 0.27 | −0.32 | 1.35 |

| Au/TiO2/Ti | 0.27 | −0.18 | 1.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahaman, M.; Islam, M.F.; Ahsan, M.; Hossain, M.I.; Mohammad, F.; Oyshi, T.A.; Rashed, M.A.; Uddin, J.; Hasnat, M.A. Development of a Au/TiO2/Ti Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in a Bicarbonate Medium. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111074

Rahaman M, Islam MF, Ahsan M, Hossain MI, Mohammad F, Oyshi TA, Rashed MA, Uddin J, Hasnat MA. Development of a Au/TiO2/Ti Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in a Bicarbonate Medium. Catalysts. 2025; 15(11):1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111074

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahaman, Mostafizur, Md. Fahamidul Islam, Mohebul Ahsan, Mohammad Imran Hossain, Faruq Mohammad, Tahamida A. Oyshi, Md. Abu Rashed, Jamal Uddin, and Mohammad A. Hasnat. 2025. "Development of a Au/TiO2/Ti Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in a Bicarbonate Medium" Catalysts 15, no. 11: 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111074

APA StyleRahaman, M., Islam, M. F., Ahsan, M., Hossain, M. I., Mohammad, F., Oyshi, T. A., Rashed, M. A., Uddin, J., & Hasnat, M. A. (2025). Development of a Au/TiO2/Ti Electrocatalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction in a Bicarbonate Medium. Catalysts, 15(11), 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15111074