The Green Preparation of ZrO2-Modified WO3-SiO2 Composite from Rice Husk and Its Excellent Oxidative Desulfurization Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

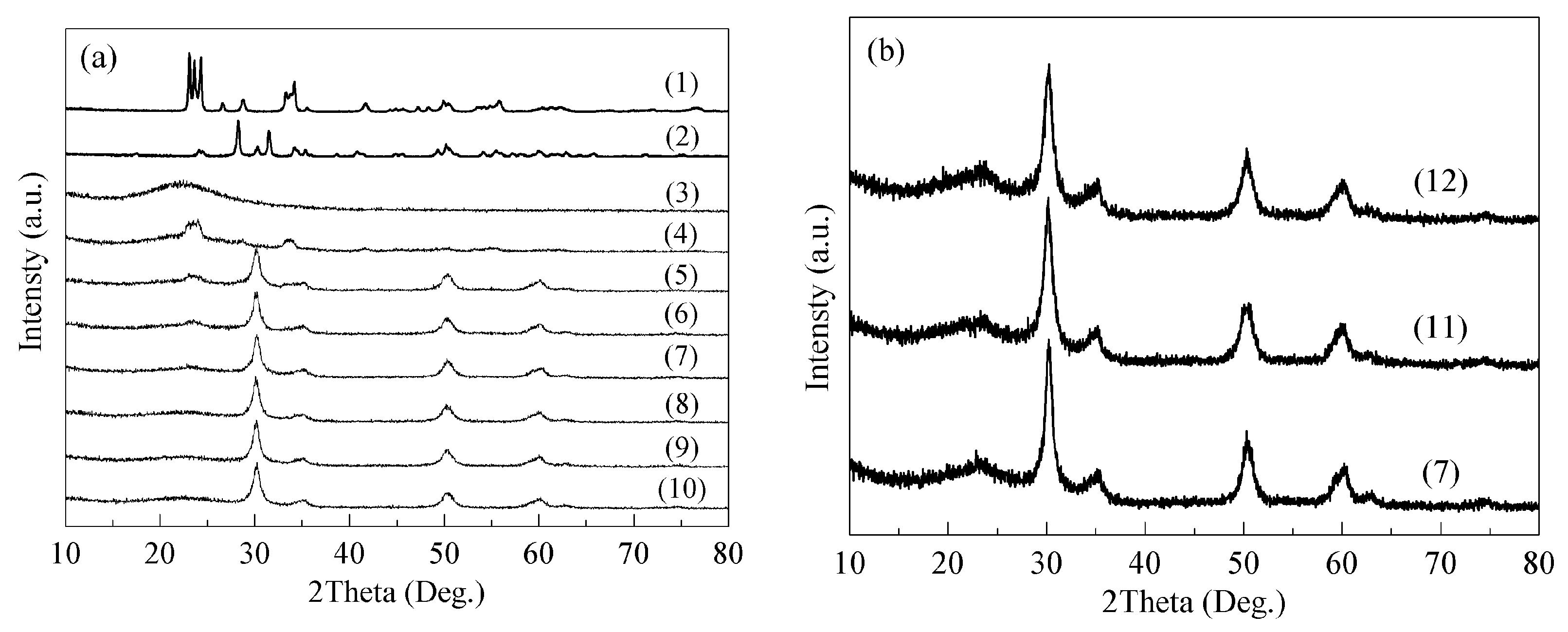

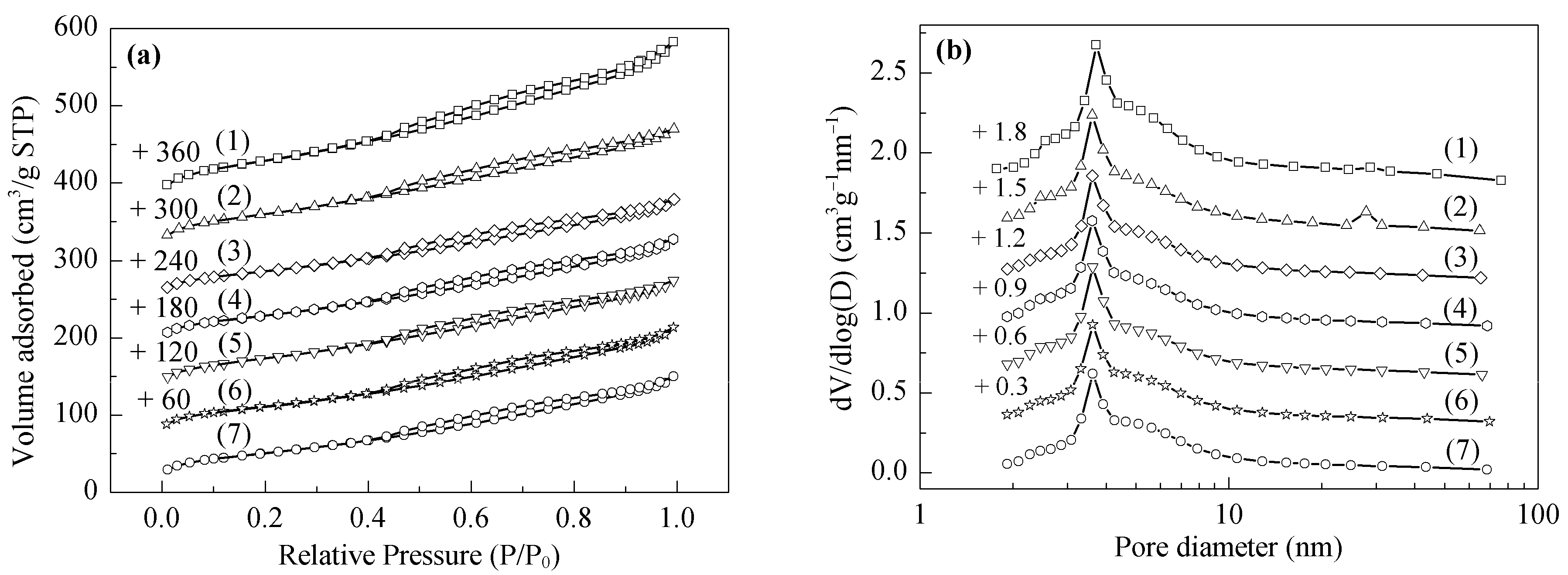

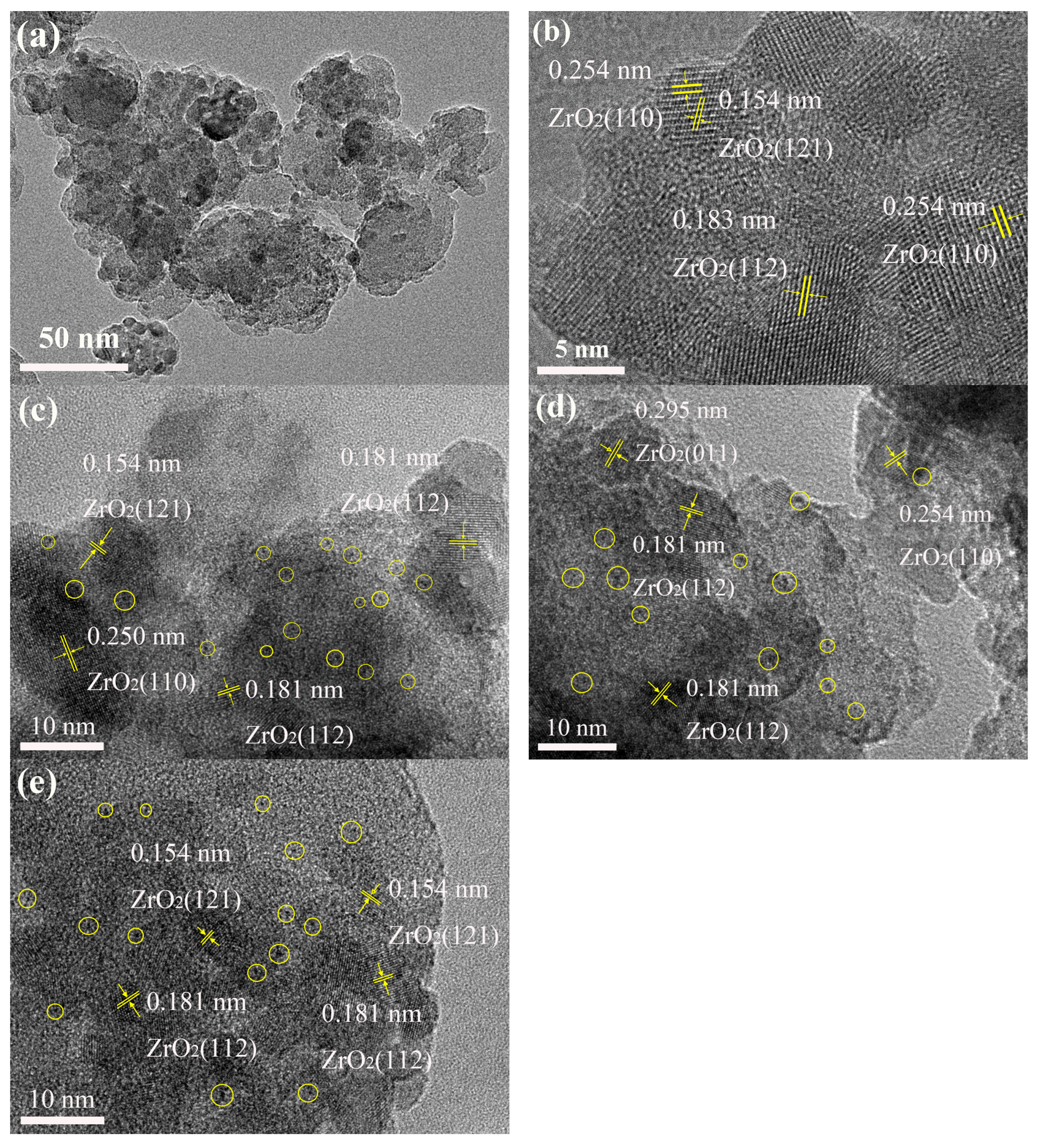

2.1. Structural Characterizations

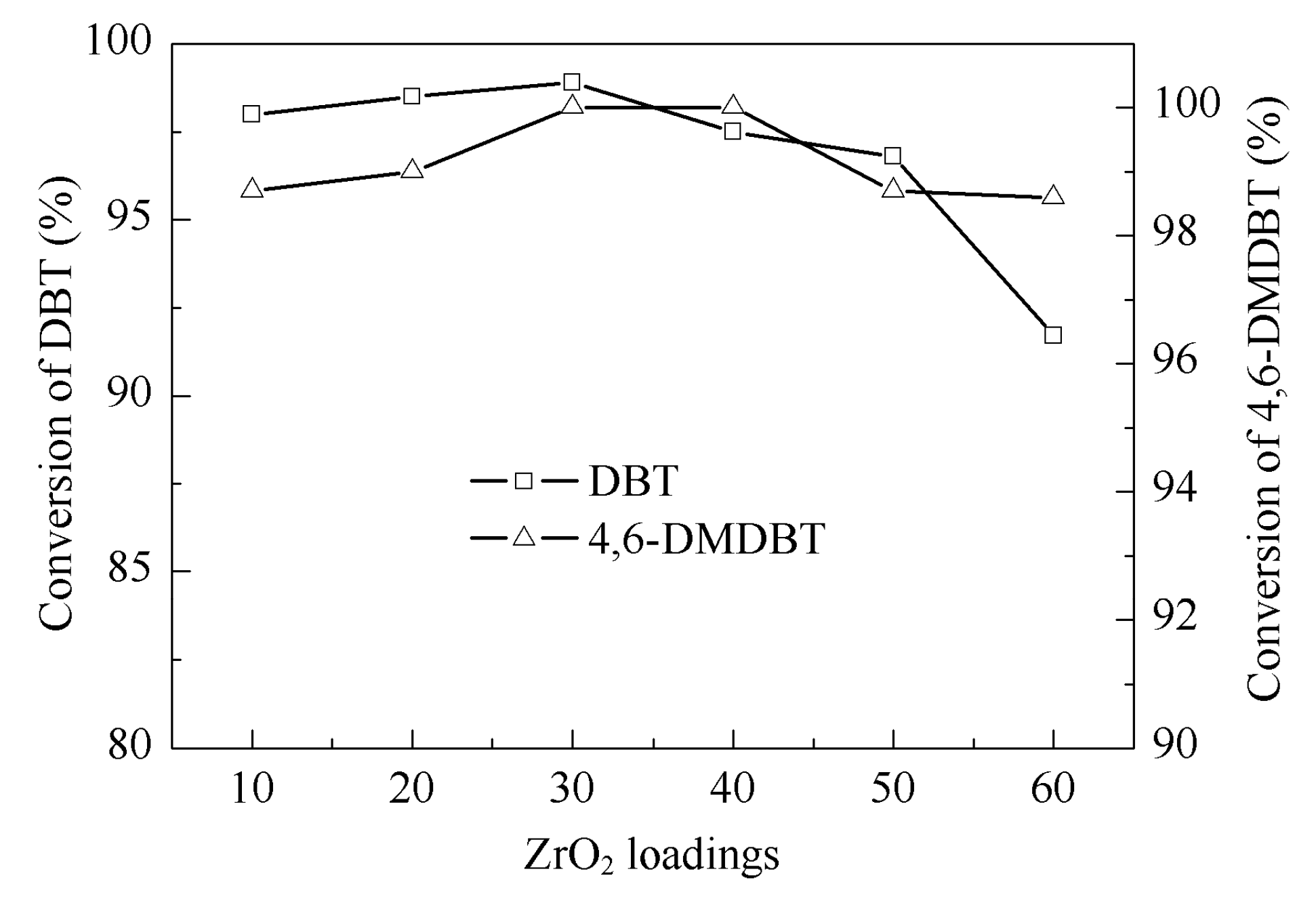

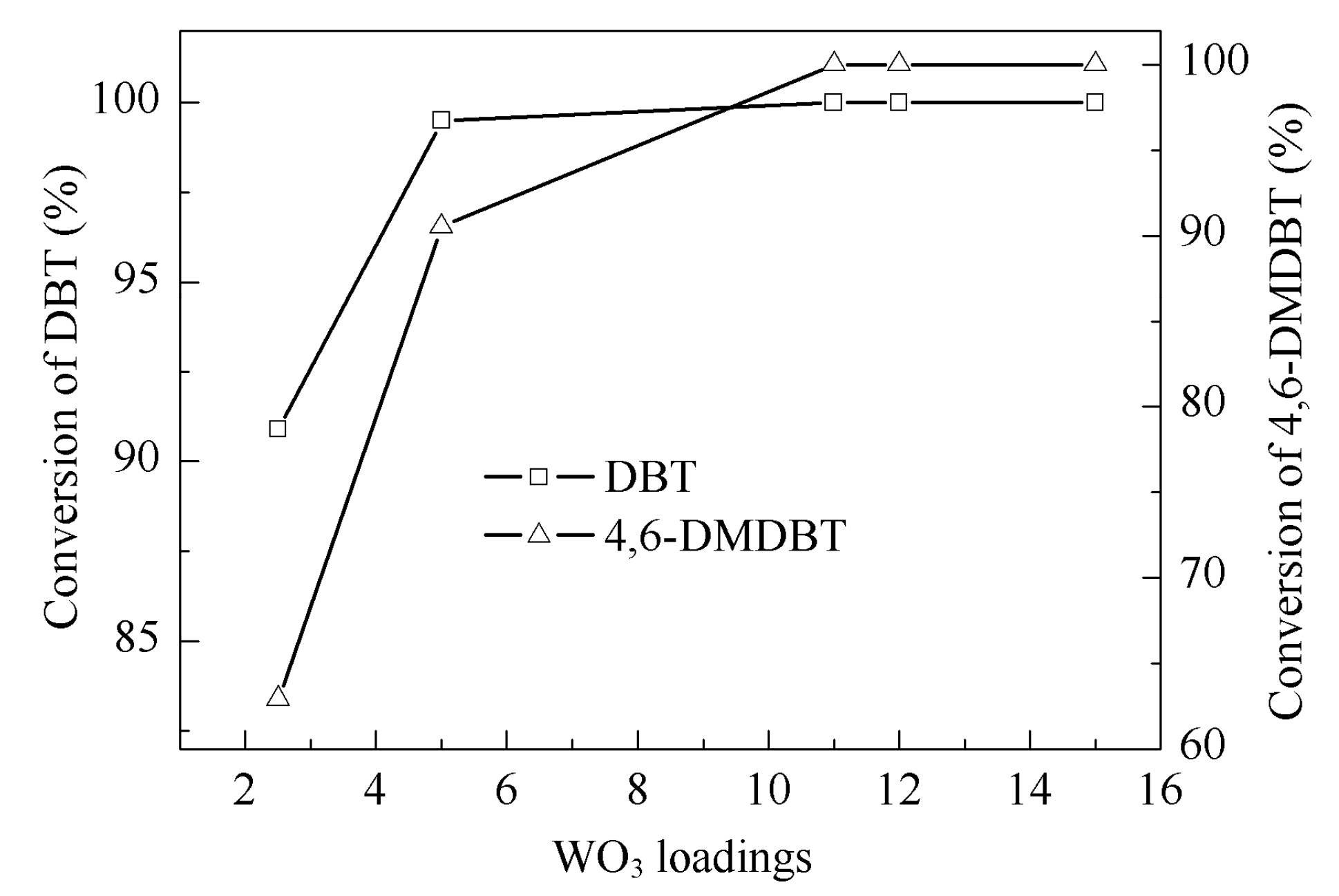

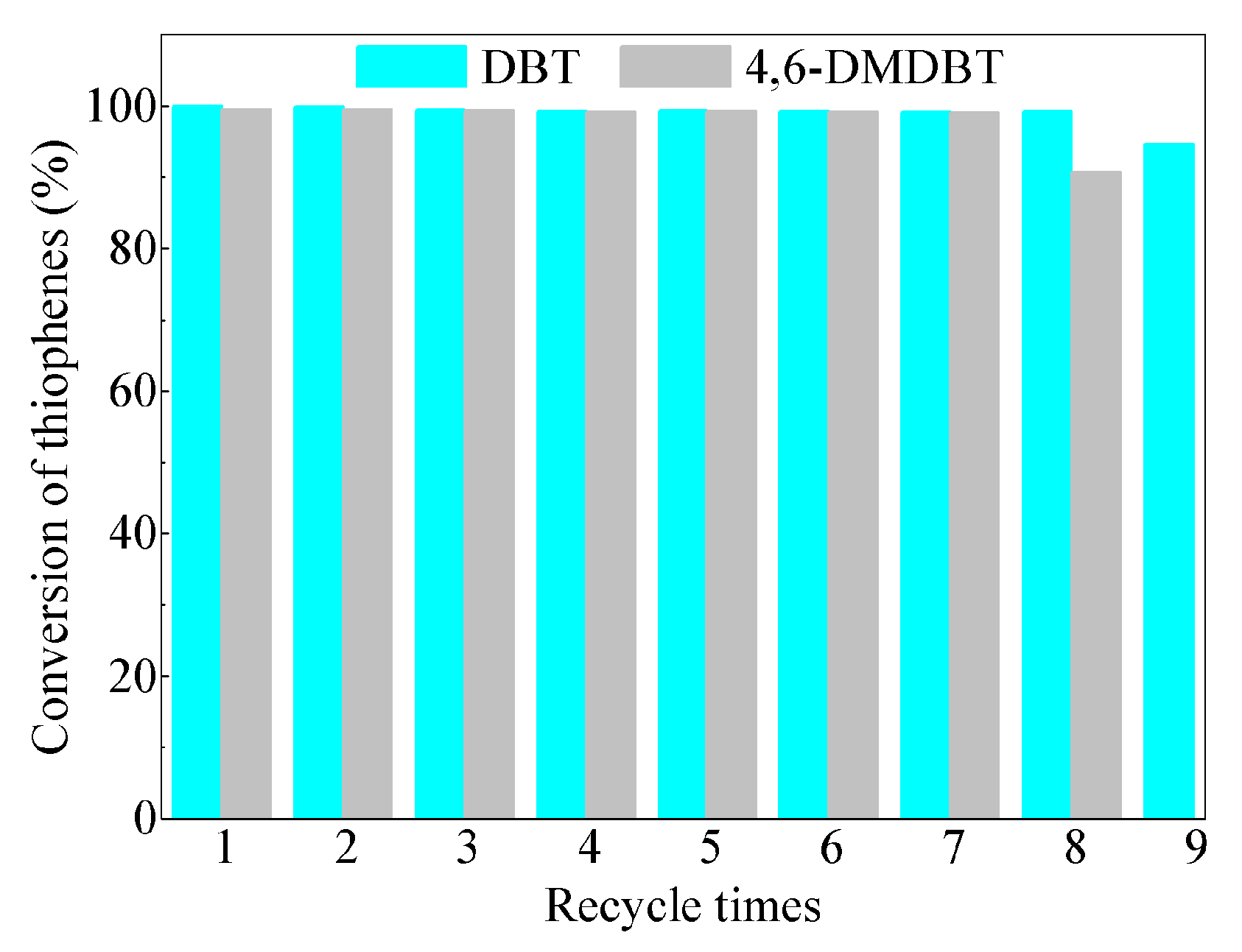

2.2. Catalytic Activity

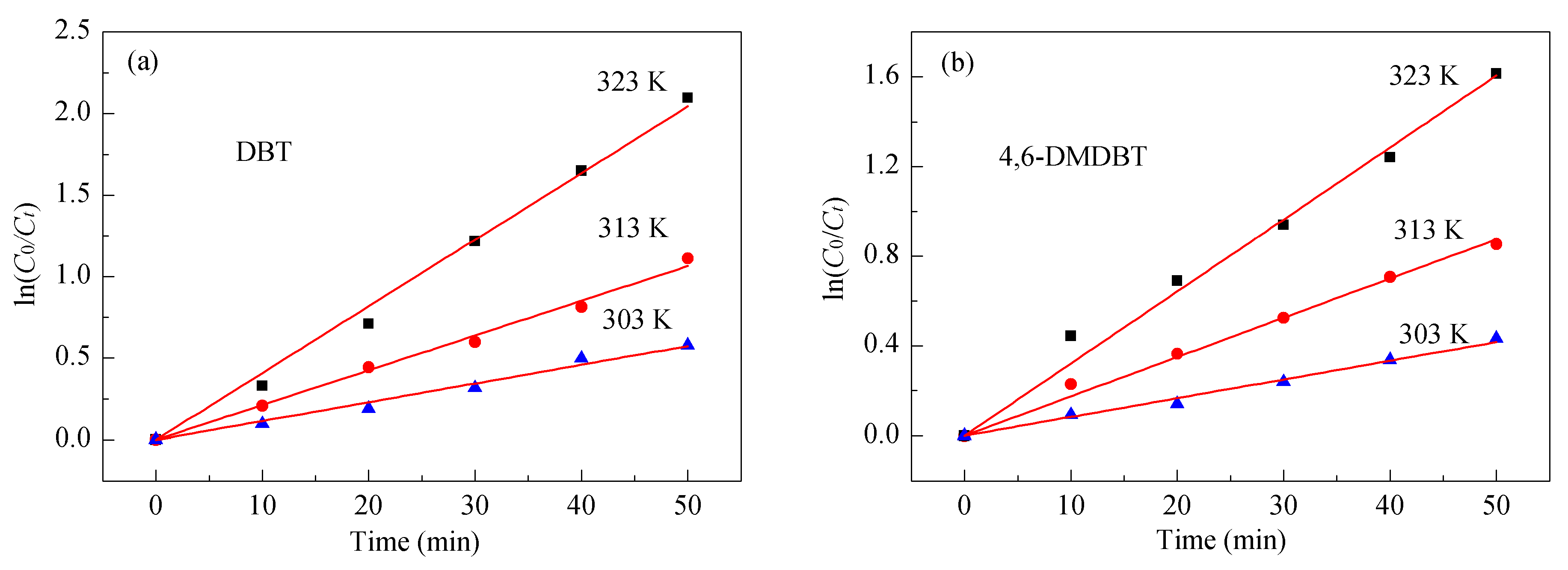

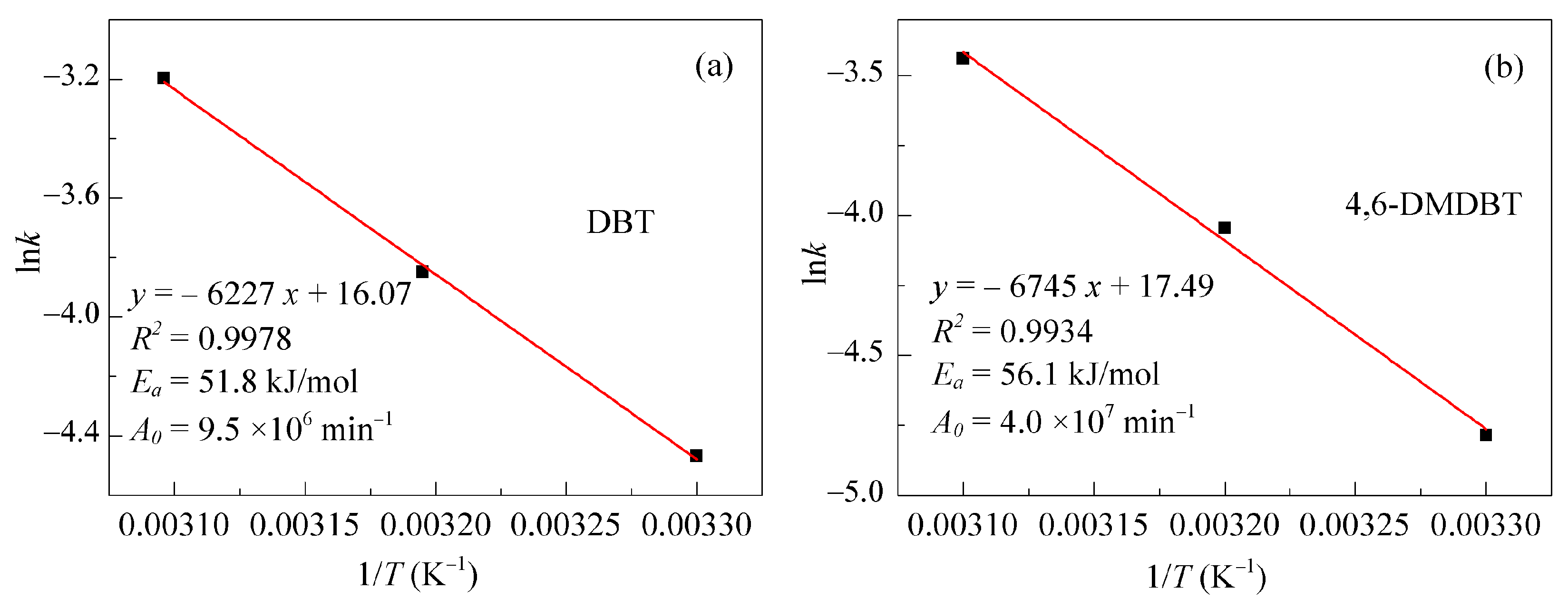

2.3. Kinetics of the ODS Reaction

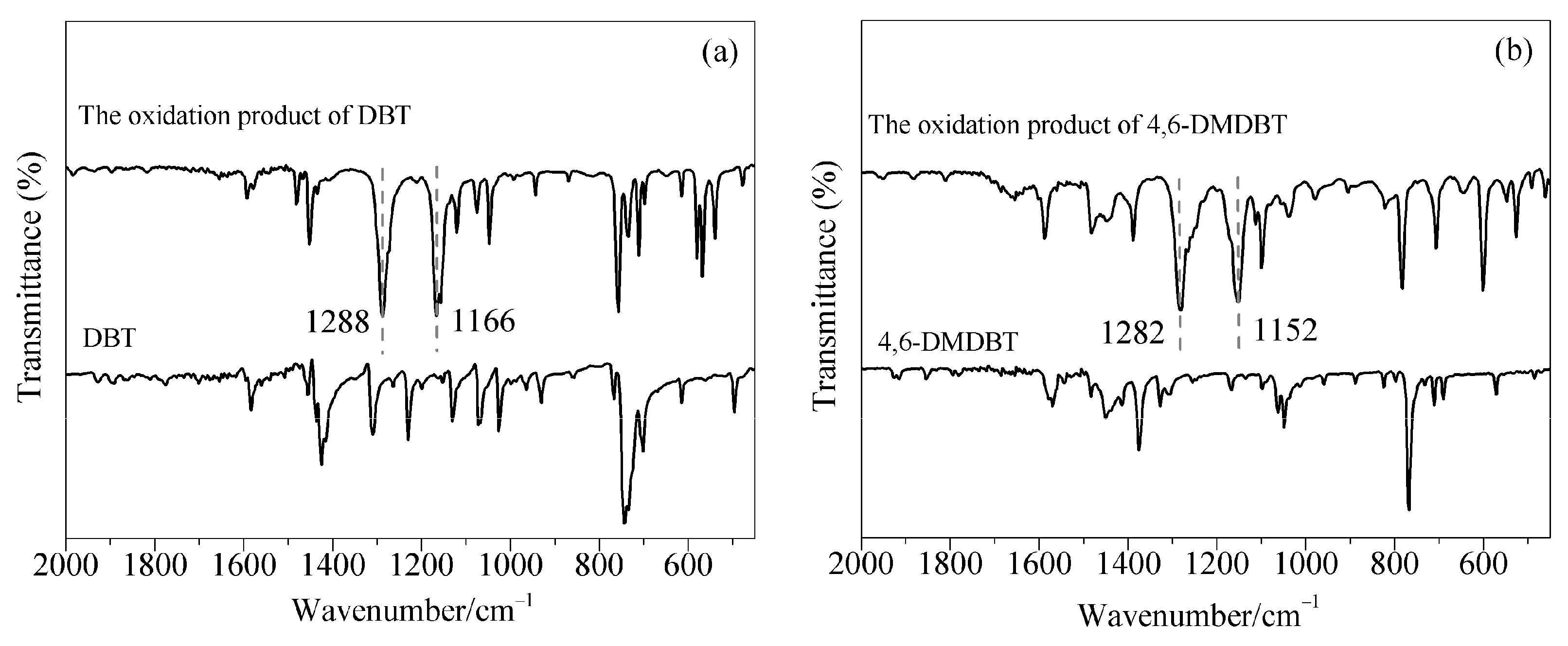

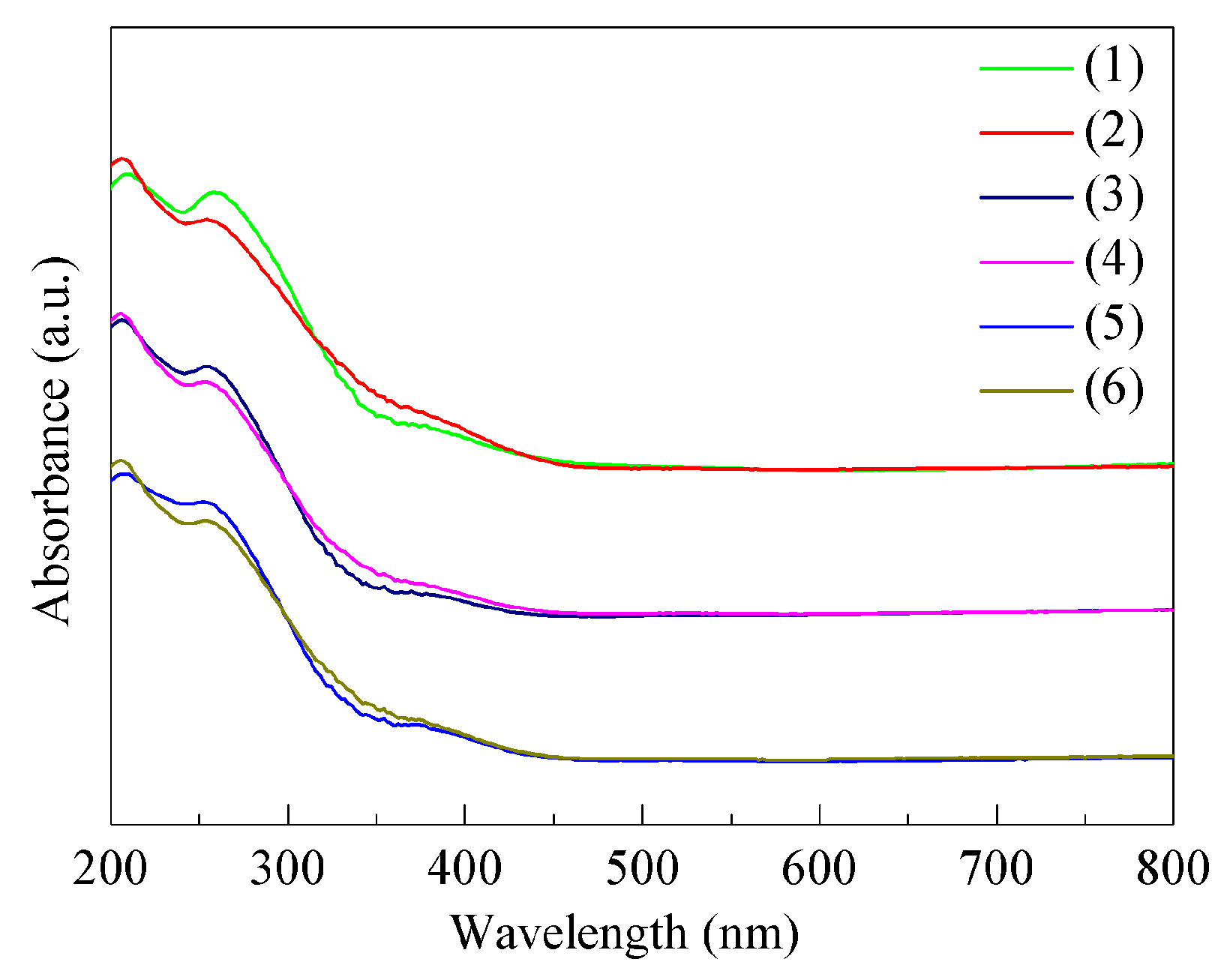

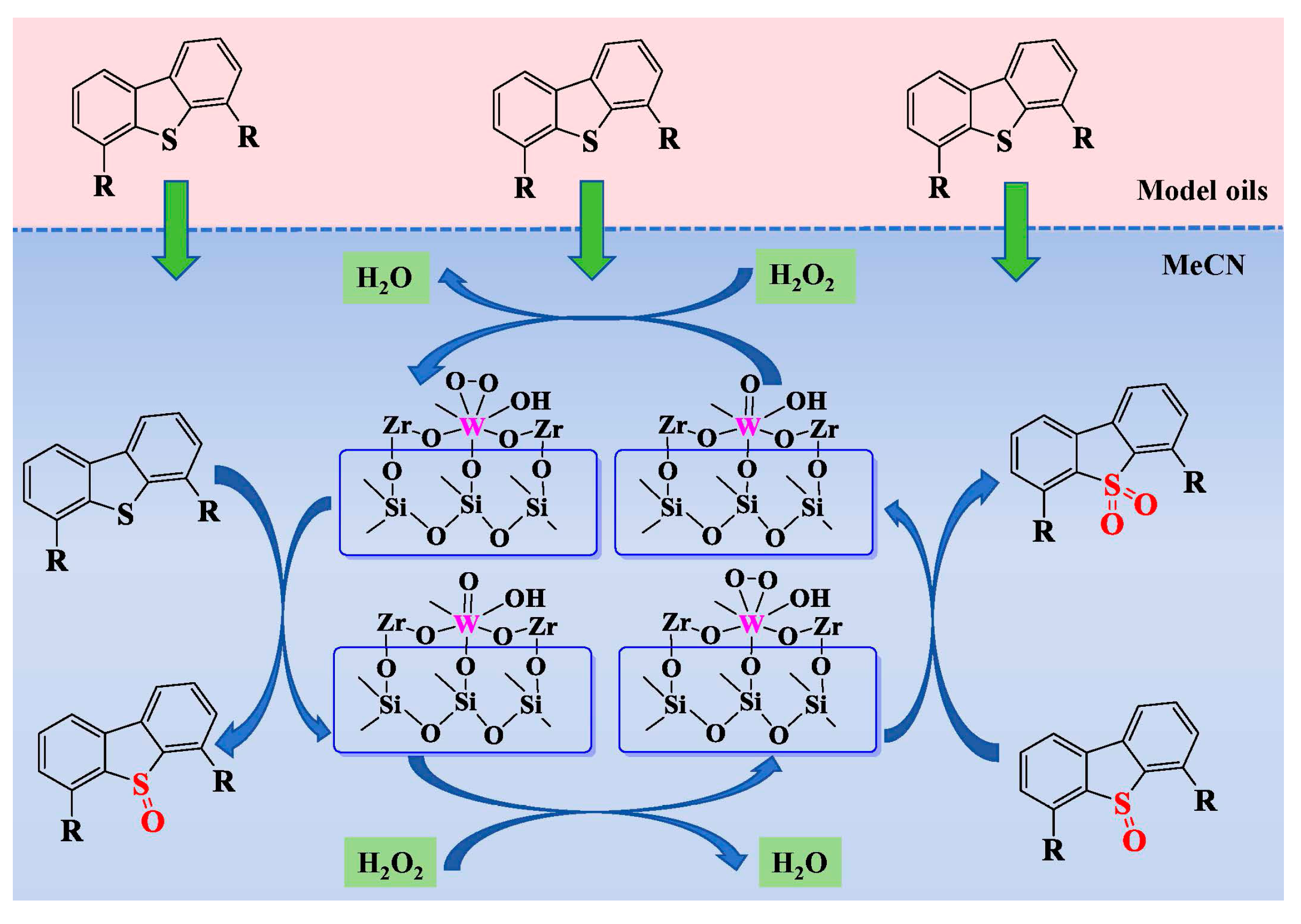

2.4. Reaction Mechanism of the ODS Process

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of WO3/ZrO2-SiO2-RH Samples

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Catalytic Activity and Recycling Tests

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X. Research progress of functional materials for conversion of agricultural biomass wastes. Huanjing Kexue 2024, 45, 4332–4351. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Qian, Q.; Luo, Y.; Cui, M.; Chen, Y.; Yang, D.P.; Chen, Q. Visible light-assisted efficient degradation of dye pollutants with biomass-supported TiO2 hybrids. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2018, 82, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, B.; Basumatary, B.; Wary, N.; Basumatary, U.R.; Basumatary, J.; Rokhum, S.L.; Azam, M.; Min, K.M.; Basumatary, S. Agricultural waste-based heterogeneous catalyst for the production of biodiesel: A ranking study via the VIKOR method. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 7208754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, A.; Zha, F.; Liu, T.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y. Environmentally friendly biological activated carbon derived from sugarcane waste as a promising carbon source for efficient and robust rechargeable zinc-air battery. Catalysts 2024, 14, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, J.A.; Bautista, L.F.; Morales, G.; Iglesias, J.; Sánchez-Vázquez, R. Biodiesel production from crude palm oil using sulfonic acid-modified mesostructured catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 161, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldiehy, K.S.H.; Daimary, N.; Borah, D.; Sarmah, D.; Bora, U.; Mandal, M.; Deka, D. Towards biodiesel sustainability: Waste sweet potato leaves as a green heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production using microalgal oil and waste cooking oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, F.; Farooq, M.; Naeem, A.; Humayun, M.; Saeed, T.; Khan, I.W.; Abid, G. Catalytic conversion of agricultural waste biomass into valued chemical using bifunctional heterogeneous catalyst: A sustainable approach. Catal. Commun 2022, 171, 106516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, D.; Tago, T.; Masuda, T.; Abimanyu, H. Conversion of cacao pod husks by pyrolysis and catalytic reaction to produce useful chemicals. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 66, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.L.; Seo, J.S.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J.W. Activated carbon with hierarchical micro-mesoporous structure obtained from rice husk and its application for lithium-sulfur batteries. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4144–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unglaube, F.; Atia, H.; Bartling, S.; Carsten, R.; Kreyenschulte, C.R.; Mejía, E. Hydrogenation of epoxides to anti-markovnikov alcohols over a nickel heterogenous catalyst prepared from biomass (rice) waste. Helv. Chim. Acta 2023, 106, e202200167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics Announces Grain Production Data for 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202312/t20231211_1945417.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Peralta, Y.M.; Molina, R.; Moreno, S. Rice HUSK silica: A review from conventional uses to new catalysts for advanced oxidation processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 370, 122735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. A new method of utilizing rice husk: Consecutively preparing d-xylose, organosolv lignin, ethanol and amorphous superfine silica. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 291, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, K.; Morales, L.F.; Tarazona, N.A.; Aguado, R.; Saldarriaga, F.J. Use of biochar from rice husk pyrolysis: Part A: Recovery as an adsorbent in the removal of emerging compounds. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7625–7637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, M.U.; Hadi, B.A.; Idris, B.; Abduljalil, M.M. Preparation of high surface area activated carbon from native rice husk. Lond. J. Eng. Res. 2021, 21, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, L.A.; Liaquat, R.; Aman, M.; Kanan, M.; Saleem, M.; khoja, A.H.; Bahadar, A.; Khan, W.U.H. Investigation of novel transition metal loaded hydrochar catalyst synthesized from waste biomass (rice husk) and its application in biodiesel production using waste cooking oil (WCO). Sustainability 2024, 16, 7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Cheng, F.; Lin, J.; Yang, J.; Jiang, K.; Wen, Z.; Sun, J. High surface area C/SiO2 composites from rice husks as a high-performance anode for lithium ion batteries. Powder Technol. 2017, 311, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, S.; Restiawaty, E.; Pasymi, P.; Bindar, Y. An appropriate acid leaching sequence in rice husk ash extraction to enhance the produced green silica quality for sustainable industrial silica gel purpose. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 122, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.S.; Devi, K.R.S.; Karthik, K.; Sugunan, S. Modified rice husk silica from biowaste: An efficient catalyst for transesterification of diethyl malonate and benzyl alcohol. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 4809–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiye, M.A.; Hafida, W.; Kong, F.; Zhou, C. A review of the use of rice husk silica as a sustainable alternative to traditional silica sources in various applications. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, e14451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyosef, H.A.; Uhlig, H.; Muenster, T.; Kloess, G.; Einicke, W.D.; Glaeser, R.; Enke, D. Biogenic silica from rice husk ash-sustainable sources for the synthesis of value added silica. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014, 37, 667–672. [Google Scholar]

- Gebretatios, A.G.; Pillantakath, A.R.K.K.; Witoon, T.; Lim, J.W.; Banat, F.; Cheng, C.K. Rice husk waste into various template-engineered mesoporous silica materials for different applications: A comprehensive review on recent developments. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.W.; Hsiao, T.J.; Chung, S.W.; Lo, J.J. Nickel supported on rice husk ash-activity and selectivity in CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. A 1997, 164, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva Priya, A.; Sunaja Devi, K.R. Designing biomass rice husk silica as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of biofuel additive n-butyl levulinate. BioEnergy Res. 2020, 13, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, F.; Iqbal, A. The liquid phase oxidation of styrene with tungsten modified silica as a catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, P.P.; Li, S.F.Y. Efficient removal of rhodamine B using a rice hull-based silica supported iron catalyst by fenton-like process. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 229, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, R.J.; Appaturi, J.N.; Pulingam, T.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Al-dhayan, D.M. In-situ incorporation of ruthenium/copper nanoparticles in mesoporous silica derived from rice husk ash for catalytic acetylation of glycerol. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unglaube, F.; Kreyenschulte, C.R.; Mejía, E. Development and application of efficient Ag-based hydrogenation catalysts prepared from rice husk waste. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 2583–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, X.; Cheng, H.; Li, Q.; Li, H. The utilization of rice husk as both the silicon source and mesoporous template for the green preparation of mesoporous TiO2/SiO2 and its excellent catalytic performance in oxidative desulfurization. Molecules 2024, 29, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Li, H. The green preparation of mesoporous WO3/SiO2 and its application in oxidative desulfurization. Catalysts 2024, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, P. Tungsten oxides, tungsten bronzes and tungsten bronze-type structures. Key Eng. Mater. 1992, 68, 293–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, P.; Liao, S.; Si, H.; Chen, S.; Fan, G.; Wang, Z. Morphology-controllable hydrothermal synthesis of zirconia with the assistance of a rosin-based surfactant. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Y. Synthesis of DL-tartaric acid from maleic anhydride over SiO2-modified WO3-ZrO2 catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Park, D.S.; Choi, Y.; Baek, J.; Park, J.R.; Yi, J. Preparation and characterization of mesoporous Zr-WOx/SiO2 catalysts for the esterification of 1-butanol with acetic acid. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10021–10028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Xu, B.; Xu, B.; Guo, J.; Li, S. Improved acidity of mesoporous ZrO2-WO3 through NH3-air subsection-calcination treatment. Quim. Nova 2024, 47, e-20240029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.D.; Valverde, J.L.; CanÄizares, P.; Rodriguez, L. Partial oxidation of methane to formaldehyde over W/SiO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 1999, 184, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunyaratchatanon, C.; Luengnaruemitchai, A.; Chaisuwan, T.; Chollacoop, N.; Chen, S.Y.; Yoshimura, Y. Synthesis and characterization of Zr incorporation into highly ordered mesostructured SBA-15 material and its performance for CO2 adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 253, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Chang, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Han, J.; Ge, Q. Enhancing tungsten oxide/SBA-15 catalysts for hydrolysis of cellobiose through doping ZrO2. Appl. Catal. A 2016, 523, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.L.; Alvarez-Amparán, M.A.; Cedeño-Caero, L. Performance of WOx-VOx based catalysts for ODS of dibenzothiophene compounds. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 95, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, A.; Xu, J.; Wen, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Preparation of WO3/CNT catalysts in presence of ionic liquid [C16mim]Cl and catalytic efficiency in oxidative desulfurization. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 3403–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Medgaarden, E.I.; Knowles, W.V.; Kim, T.; Wong, M.S.; Zhou, W.; Kiely, C.J.; Wachs, I.E. New insights into the nature of the acidic catalytic active sites present in ZrO2-supported tungsten oxide catalysts. J. Catal. 2008, 256, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liao, W.; Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Fu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, L. Aerobic oxidative desulfurization by nanoporous tungsten oxide with oxygen defects. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Jácome, M.A.; Angeles-Chavez, C.; Lόpez-Salinas, E.; Navarrete, J.; Toribio, P.; Toledo, J.A. Migration and oxidation of tungsten species at the origin of acidity and catalytic activity on WO3-ZrO2 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 2007, 318, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.R.; Wang, Y.F.; Duan, G.Y.; Fan, Y.Q.; Xu, B.H. Adjustment of W−O−Zr boundaries boosts efficient nitrilation of dimethyl adipate with ammonia on WOx/ZrO2 catalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 3633–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, T.; Zhao, J.; Li, J. Direct synthesis of homogeneous Zr-doped SBA-15 mesoporous silica via masking zirconium sulfate. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 257, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenares-Zerpa, J.; Gajardo, J.; Peixoto, A.F.; Silva, D.S.A.; Silva, J.A.; Gispert-Guirado, F.; Llorca, J.; Urquieta-Gonzalez, E.A.; Santos, J.B.O.; Chimentao, R.J. High zirconium loads in Zr-SBA-15 mesoporous materials prepared by direct-synthesis and pH-adjusting approaches. J. Solid State Chem. 2022, 312, 123296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimirad, R.; Naseri, N.; Akhavan, O.; Moshfegh, A.Z. Hydrophilicity variation of WO3 thin films with annealing temperature. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2007, 40, 1134–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpak, A.P.; Korduban, A.M.; Medvedskij, M.N.; Kandyba, V.O. XPS studies of active elements surface of gas sensors based on WO3−x nanoparticles. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2007, 156, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Y. Boosting oxidative adsorptive desulfurization of fuel oil by constructing a mesoporous coupled desulfurizer with bimetal of MoO3 and WO3. J. Porous Mater. 2025, 32, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecilia, J.A.; García-Sancho, C.; Mérida-Robles, J.M.; Santamaría Gonzalez, J.; Moreno-Tost, R.; Moreno-Torres, P. WO3 supported on Zr doped mesoporous SBA-15 silica for glycerol dehydration to acrolein. Appl. Catal. A 2016, 516, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, N.; Wang, J.A.; Chen, L.; Valenzuela, M.A.; Noreña, L.E.; Rojas, E.; onzález, J.; He, M.; Peng, J.; Zhou, X. Achieving ultra-low-sulfur model diesel through defective keggin-type heteropolyoxometalate Catalysts. Inorganics 2024, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.M.; Wang, J.A.; Flores, S.O.; Chen, L.; Arellano, U.; Noreña, L.E.; González, J.; Navarrete, J. Ultrasound-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of V2O5/Zr-SBA-15 catalysts for production of ultralow sulfur fuel. Catalysts 2021, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Guo, J.; Wang, D.; He, M.; Xun, S.; Gu, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, H. Preparation of highly dispersed WO3/few layer g-C3N4 and its enhancement of catalytic oxidative desulfurization activity. Colloids Surf. A 2019, 572, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foraita, S.; Liu, Y.; Haller, G.L.; Baráth, E.; Zhao, C.; Lercher, J.A. Controlling hydrodeoxygenation of stearic acid to n-heptadecane and n-octadecane by adjusting the chemical properties of Ni/SiO2–ZrO2 catalyst. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socrates, G. Sulphur and selenium compounds. In Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2001; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, S.; Xu, Q. Preparation of WO3-SBA-15 mesoporous molecular sieve and its performance as an oxidative desulfurization catalyst. Transit. Met. Chem. 2009, 34, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Xiang, J.; Wang, J.; Ding, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, W.; Li, H. Structure and catalytic oxidative desulfurization properties of SBA-15 supported silicotungstic acid ionic liquid. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jeong, H.J.; Sivaranjani, K.; Song, B.J.; Park, S.B.; Li, D.; Lee, C.W.; Jin, M.; Kim, J.M. Highly ordered mesoporous WO3 with excellent catalytic performance and reusability for deep oxidative desulfurization. Nano 2015, 10, 1550075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, S.; Hou, C.; Li, H.; He, M.; Ma, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, W.; Li, H. Synthesis of WO3/mesoporous ZrO2 catalyst as a high-efficiency catalyst for catalytic oxidation of dibenzothiophene in diesel. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 15927–15938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.X.; Zhai, S.R.; Zhang, W.; Zhai, B.; An, Q.D. Recyclable HPW/PEHA/ZrSBA-15 toward efficient oxidative desulfurization of DBT with hydrogen peroxide. Catal. Commun. 2015, 72, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Munir, M.; Intisar, A.; Waseem, A. Facile synthesis of a novel Ni-WO3@g-C3N4 nanocomposite for efficient oxidative desulfurization of both model and real fuel. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 15809–15820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wu, T. Magnetic WO3/Fe3O4 as catalyst for deep oxidative desulfurization of model oil. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2019, 240, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aty, D.M.A.; Alkahlawy, A.A.; Soliman, F.S. Eco-friendly catalyst in ultrasonic-assisted oxidative desulfurization of dibenzothiophene compound. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 320, 129414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, W.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Park, J.S.; Lee, J.; Li, Z.; Kim, K.Y.; Jin, M. Efficient and reusable ordered mesoporous WOx/SnO2 catalyst for oxidative desulfurization of dibenzothiophene. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27453–27460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Jhung, S.H. Room-temperature oxidative desulfurization with tungsten oxide supported on NU-1000 metal–organic framework. Fuel 2025, 393, 135043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A.; Kamble, P.D.; Basu, J.K.; Sengupta, S. Kinetic study and optimization of oxidative desulfurization of benzothiophene using mesoporous titanium silicate-1 catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, N.; Sengupta, S.; Basu, J.K. Optimization of oxidative desulfurization of thiophene using Cu/titanium silicate-1 by box-behnken design. Fuel 2011, 90, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, G.; Kang, L.; Zhu, M.; Dai, B. A novel [Bmim]PW/HMS catalyst with high catalytic performance for the oxidative desulfurization process. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasuriyan, S.; Mohd Zaid, H.F.; Majid, M.F.; Ramli, R.M.; Jumbri, K.; Lim, J.W.; Mohamad, M.; Show, P.L.; Yuliarto, B. Oxidative extractive desulfurization system for fuel oil using acidic eutectic-based ionic liquid. Processes 2021, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Chao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Du, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z. Catalytic kinetics of oxidative desulfurization with surfactant-type polyoxometalate-based ionic liquids. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 106, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.; Omidkhah, M.; Darian, J.T. Facilitated and selective oxidation of thiophenic sulfur compounds using MoOx/Al2O3-H2O2 system under ultrasonic irradiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 23, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Verduzco, L.F.; Reyes, J.A.D.L.; Torres-García, E. Solvent effect in homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions to remove dibenzothiophene by an oxidation-extraction scheme. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 5353–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komintarachat, C.; Trakarnpruk, W. Oxidative desulfurization using polyoxometalates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te, M.; Fairbridge, C.; Ring, Z. Oxidation reactivities of dibenzothiophenes in polyoxometalate/H2O2 and formic acid/H2O2 systems. Appl. Catal. A 2001, 219, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Yang, Z.; Shi, G.; Huang, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Song, R. Synthesis of amorphous titanium isophthalic acid catalyst with hierarchical porosity for efficient oxidative desulfurization of model feed with minimum oxidant. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, M.; Shi, F.; Ding, R.; Wang, R.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Lv, B. Amorphous Cr2WO6-modified WO3 nanowires with a large specific surface area and rich lewis acid sites: A highly efficient catalyst for oxidative desulfurization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 38140–38152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment of RH | Preparation Method | Catalyst | Application | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid leaching + Calcination | Incipient-wetness impregnation | Ni/SiO2-RH | CO2 methanation | [23] |

| Acid leaching + Calcination | Four different impregnation methods | CeO2-Sm2O3/SiO2-RH | Esterification | [24] |

| Acid leaching + NaOH extraction | Sol–gel | WO3-SiO2-RH | Selective oxidation | [25] |

| Acid leaching + NaOH extraction | Sol–gel | Fe(OH)3-SiO2-RH | Fenton-like degradation | [26] |

| Acid leaching + Calcination + NaOH extraction | Sol–gel | RuO2-CuO-MCM-41 | Acetylation | [27] |

| Ball milling | Excessive impregnation | Ag/silica-carbon | Hydrogenation | [28] |

| Sample | SBET (m2/g) | Vmeso (cm3/g) | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure WO3 | 0.1 | 0.01 | not detected |

| SiO2-RH | 294.4 | 0.39 | 3.62 |

| 30ZS-RH | 216.8 | 0.25 | 3.62 |

| 11WS-RH | 250.5 | 0.36 | 3.71 |

| 2.5W/30ZS-RH | 204.3 | 0.25 | 3.62 |

| 5W/30ZS-RH | 193.7 | 0.23 | 3.61 |

| 11W/30ZS-RH | 177.9 | 0.24 | 3.61 |

| 12W/30ZS-RH | 172.0 | 0.23 | 3.62 |

| 15W/30ZS-RH | 168.0 | 0.21 | 3.62 |

| 11W/30ZS-RHr a | 182.2 | 0.23 | 3.62 |

| 11W/30ZS-RHr b | 181.4 | 0.22 | 3.62 |

| Samples | ZrO2 Loading (wt.%) a | WO3 Loading (wt.%) a | ZrO2 Loading (wt.%) b | WO3 Loading (wt.%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30ZS-RH | 29.6 | – | 37.2 | – |

| 11W/30ZS-RH | 29.9 | 10.5 | 38.0 | 12.4 |

| 11W/30ZS-RHr c | 31.1 | 6.8 | – | – |

| 11W/30ZS-RHr d | 31.2 | 7.3 | – | – |

| Run | T (K) | H2O2/S Molar Ratio | Catalyst/Oil (g/L) | t (min) | XDBT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 313 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 92.3 |

| 2 | 323 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 97.3 |

| 3 | 333 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 99.5 |

| 4 | 343 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 99.8 |

| 5 | 353 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 100.0 |

| 6 | 333 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 81.8 |

| 7 | 333 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 91.8 |

| 8 | 333 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 100.0 |

| 9 | 333 | 18.0 | 8.0 | 60 | 100.0 |

| 10 | 333 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 60 | 70.2 |

| 11 | 333 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 60 | 87.9 |

| 12 | 333 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 60 | 99.3 |

| 13 | 333 | 6.0 | 12.0 | 60 | 100.0 |

| 14 | 333 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 5 | 75.8 |

| 15 | 333 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 15 | 93.1 |

| 16 | 333 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 30 | 98.8 |

| 17 | 333 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| Run | T (K) | H2O2/S Molar Ratio | Catalyst/Oil (g/L) | t (min) | X4,6-DMDBT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 313 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 78.8 |

| 2 | 323 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 97.2 |

| 3 | 333 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 343 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 5 | 353 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 6 | 333 | 2.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 69.9 |

| 7 | 333 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 91.1 |

| 8 | 333 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 9 | 333 | 18.0 | 10.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 10 | 333 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 120 | 74.5 |

| 11 | 333 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 120 | 88.6 |

| 12 | 333 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 120 | 96.7 |

| 13 | 333 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 120 | 99.0 |

| 14 | 333 | 6.0 | 15.0 | 120 | 100.0 |

| 15 | 333 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 78.1 |

| 16 | 333 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 30 | 92.3 |

| 17 | 333 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 60 | 99.1 |

| 18 | 333 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 90 | 100.0 |

| Run | Sample | Oxidant | XDBT (%) | X4,6-DMDBT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | 60.5 | 49.8 |

| 2 | – | H2O2 | 58.9 | 46.1 |

| 3 | WO3 | H2O2 | 68.3 | 57.3 |

| 4 | 30ZS-RH | H2O2 | 65.4 | 54.0 |

| 5 | 11WS-RH | H2O2 | 99.8 | 99.8 |

| 6 | 11W/30ZS-RH | – | 62.2 | 50.9 |

| 7 | 11W/30ZS-RH | H2O2 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 8 | 11%WO3/SiO2-gel | H2O2 | 70.0 | 61.5 |

| 9 | 11%WO3/30%ZrO2-SiO2-gel | H2O2 | 84.3 | 81.0 |

| Sample | T (K) | Cyclic Number | XDBT a (%) | X4,6-DMDBT a (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3-SBA-15 | 333 | 3 | 91.3 | – | [56] |

| HSiW-IL/SBA-15 | 333 | 8 | 96.4 | – | [57] |

| Mesoporous WO3/KIT-6 | 323 | 5 | 100 | – | [58] |

| WO3/few layer g-C3N4 | 323 | 6 | 100 | – | [53] |

| 700-C16-WO3/ZrO2 | 323 | 10 | 94 | – | [59] |

| HPW/PEHA/Zr/SBA-15 | 333 | 6 | 95 | – | [60] |

| Ni-WO3@g-C3N4 | 313 | 5 | 90.4 | – | [61] |

| 35%WO3/Fe3O4 | 373 | 5 | 90.4 | – | [62] |

| 10%WO3@activated carbon | 333 | 4 | 97.7 | – | [63] |

| 20 wt%WOx/meso-SnO2 | 323 | 6 | 100 | – | [64] |

| W(5.0)@NU-1000 | 298 | 6 | 99.0 | – | [65] |

| 11W/30ZS-RH | 333 | 8 | 99.2 | 99.0 b | This work |

| Model Compound | T (K) | k (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBT | 303 | 0.0114 | 0.9974 |

| DBT | 313 | 0.0212 | 0.9976 |

| DBT | 323 | 0.0407 | 0.9933 |

| 4,6-DMDBT | 303 | 0.0084 | 0.9968 |

| 4,6-DMDBT | 313 | 0.0175 | 0.9970 |

| 4,6-DMDBT | 323 | 0.0321 | 0.9958 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, F.; Liu, X. The Green Preparation of ZrO2-Modified WO3-SiO2 Composite from Rice Husk and Its Excellent Oxidative Desulfurization Performance. Catalysts 2025, 15, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100996

Li H, Xiang X, Zhang Y, Cheng H, Chen Q, Li X, Wu F, Liu X. The Green Preparation of ZrO2-Modified WO3-SiO2 Composite from Rice Husk and Its Excellent Oxidative Desulfurization Performance. Catalysts. 2025; 15(10):996. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100996

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hao, Xiaorong Xiang, Yinhai Zhang, Huiqing Cheng, Qian Chen, Xiang Li, Feng Wu, and Xiaoxue Liu. 2025. "The Green Preparation of ZrO2-Modified WO3-SiO2 Composite from Rice Husk and Its Excellent Oxidative Desulfurization Performance" Catalysts 15, no. 10: 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100996

APA StyleLi, H., Xiang, X., Zhang, Y., Cheng, H., Chen, Q., Li, X., Wu, F., & Liu, X. (2025). The Green Preparation of ZrO2-Modified WO3-SiO2 Composite from Rice Husk and Its Excellent Oxidative Desulfurization Performance. Catalysts, 15(10), 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100996