Tannic Acid-Induced Morphological and Electronic Tuning of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

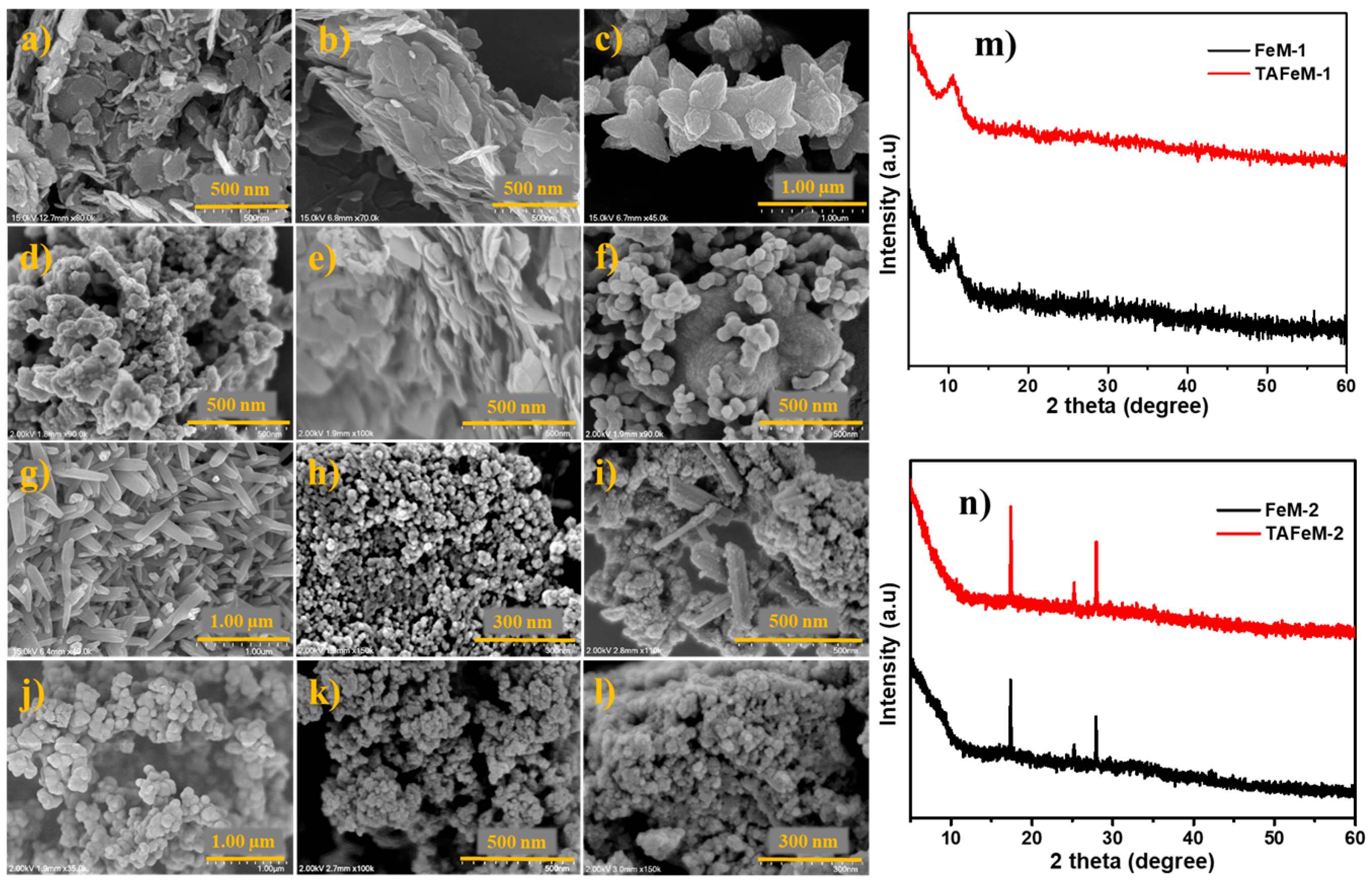

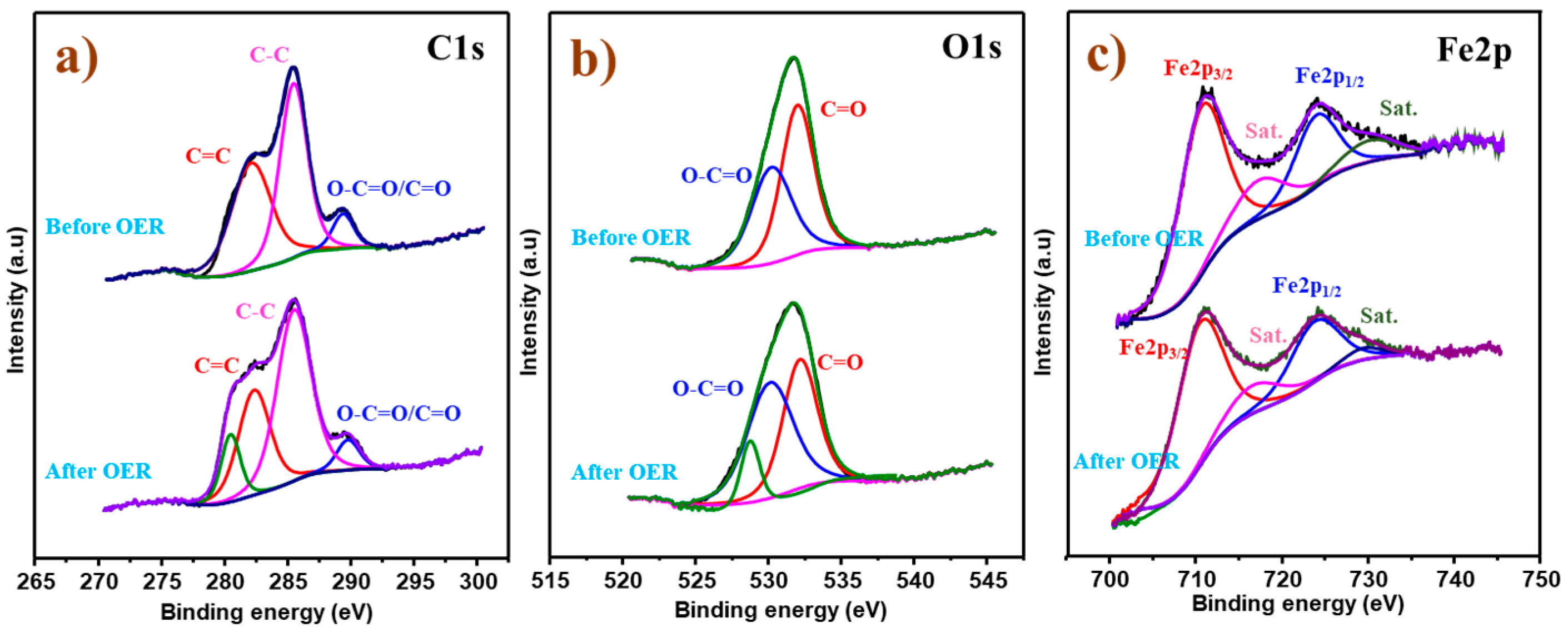

2.1. Structure and Morphology Elucidation

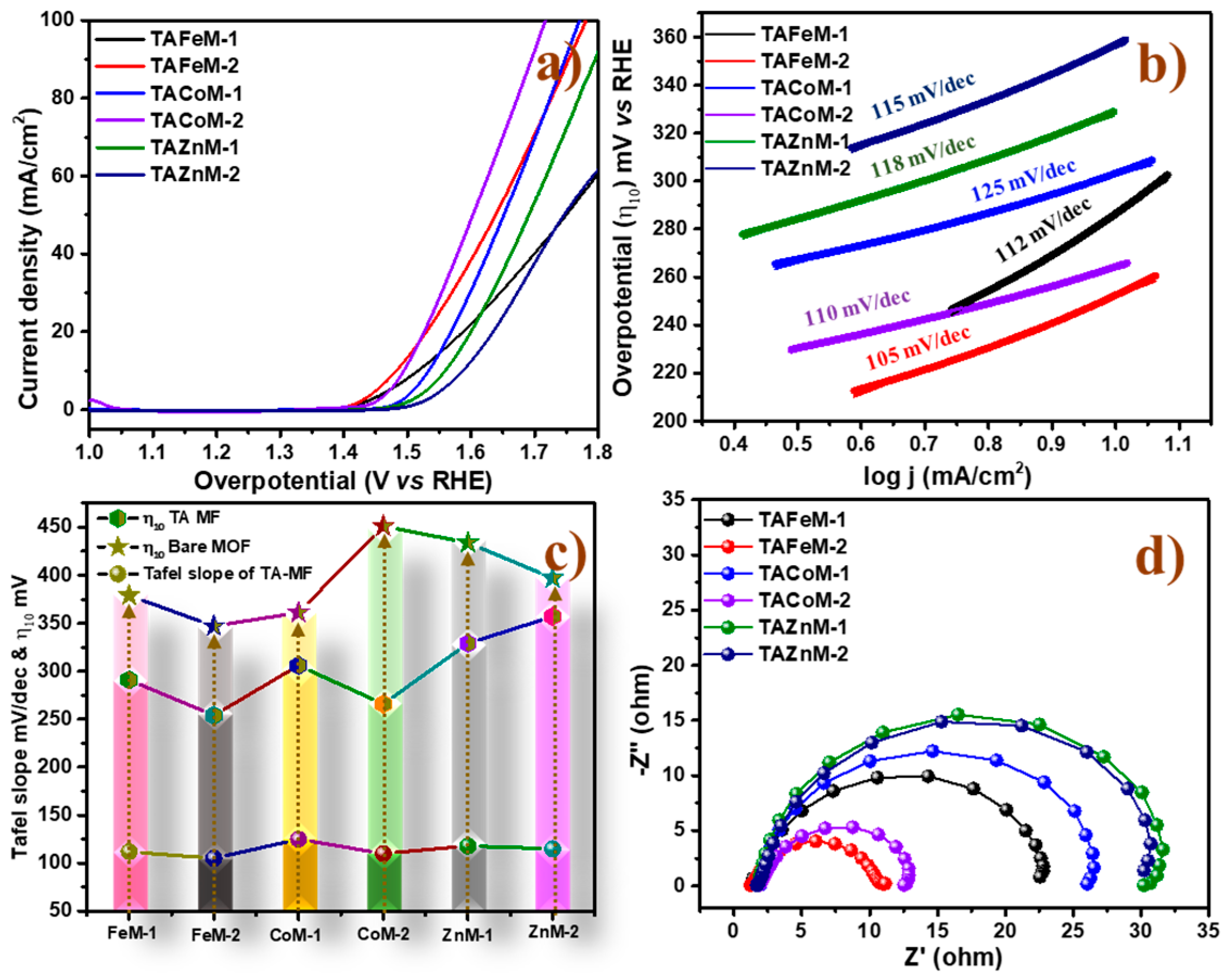

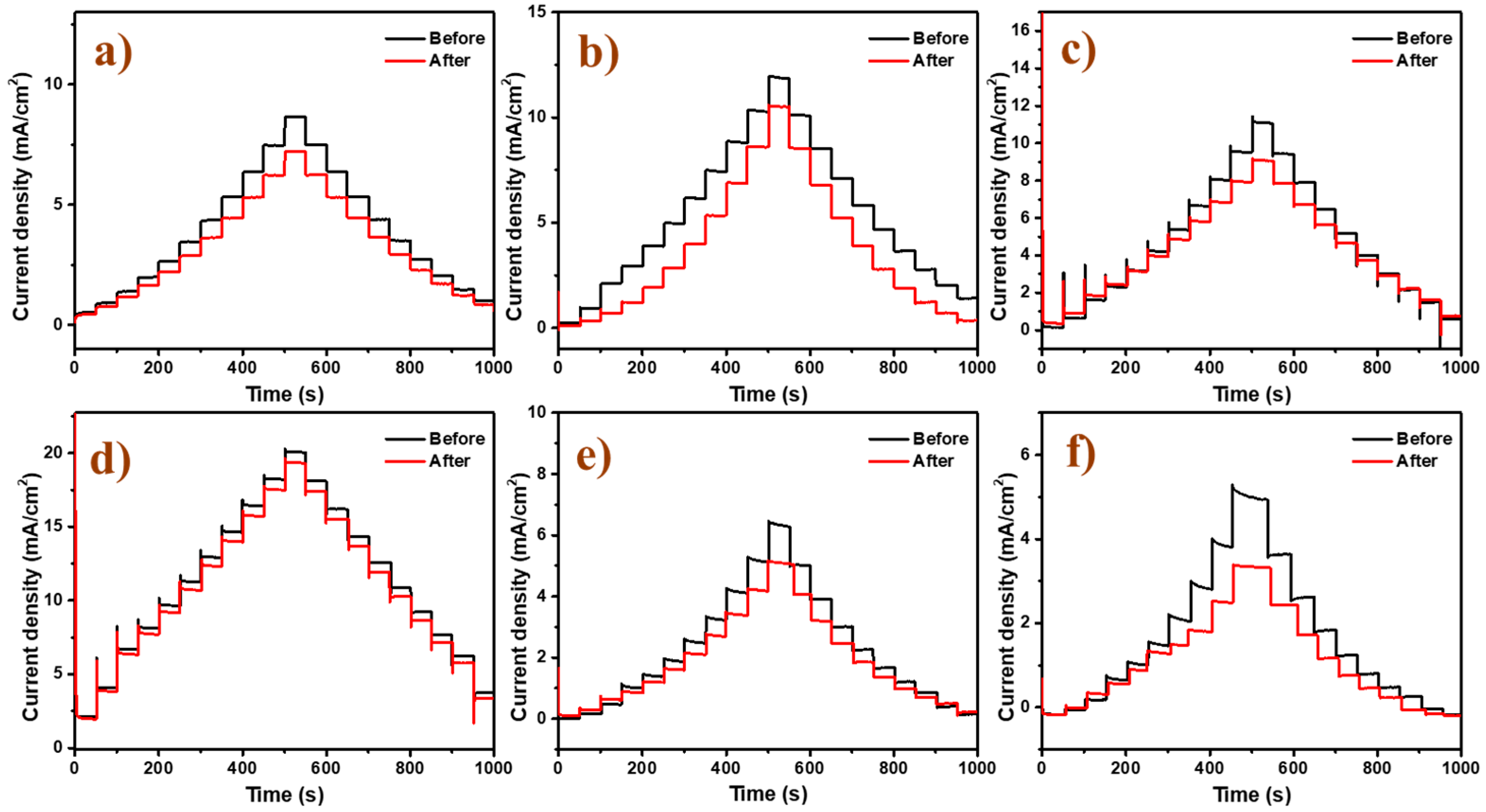

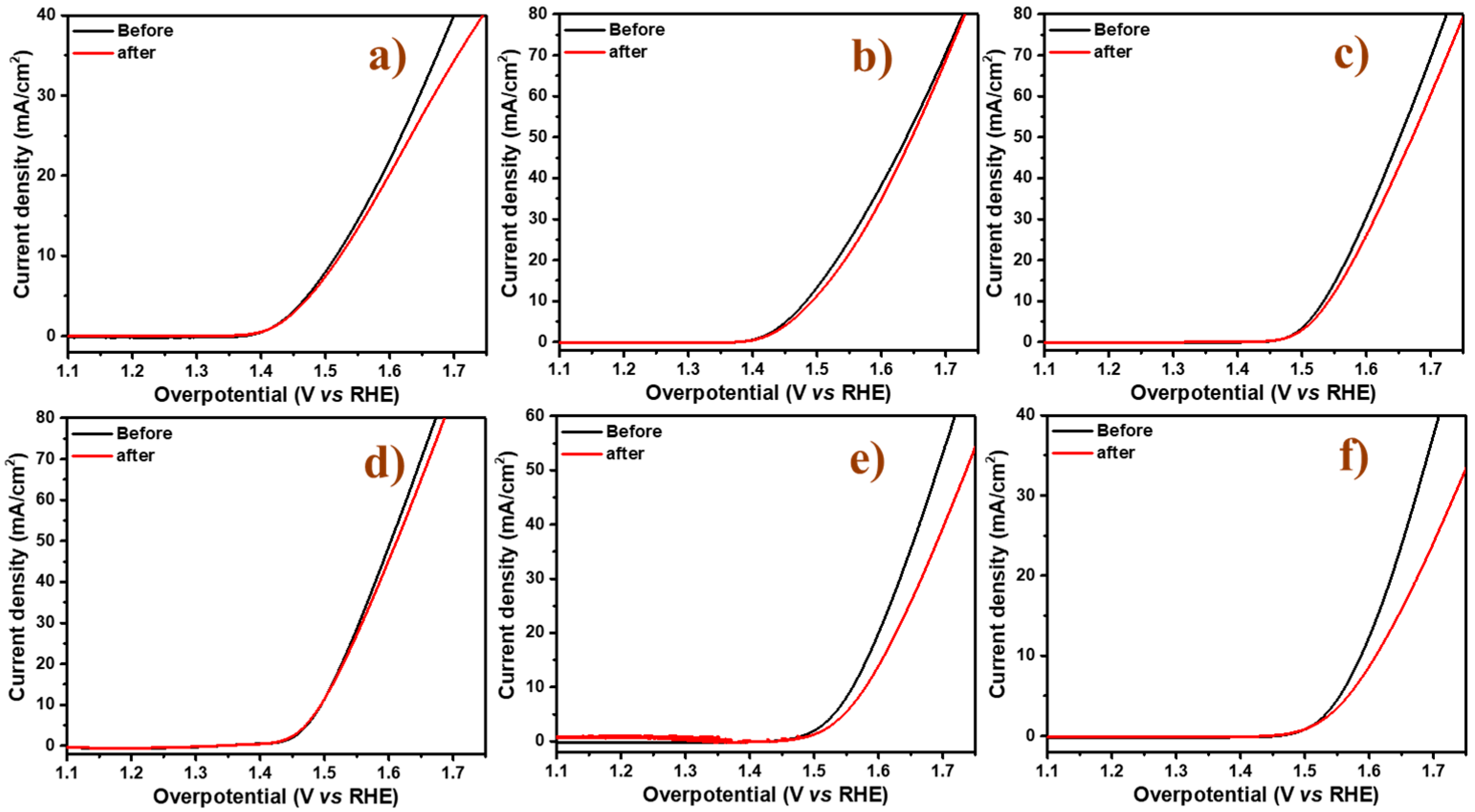

2.2. Electrocatalytic Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of MOF and Surface Tuning by TA

3.2. Physico-Chemical and Electrochemical Characterizations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Z.; Dai, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, X.; Mu, W.; Guo, R.; Liu, X.; You, J. The role of strain in oxygen evolution reaction. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 93, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, C.; Huang, X.; Arandiyan, H.; Shao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Advances in Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysts via Direct Oxygen–Oxygen Radical Coupling Pathway. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2416362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Jones, M.; Lyu, C.; Loh, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X. Challenges and progress in oxygen evolution reaction catalyst development for seawater electrolysis for hydrogen production. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 6416–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.; Chung, D.Y. Activity–Stability Relationships in Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Li, K.; Huang, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, B.; Yi, L.; Jones, T.W. Cost-effective and durable electrocatalysts for Co-electrolysis of CO2 conversion and glycerol upgrading. Nano Energy 2022, 92, 106751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xuan, H.; Wang, J.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Cheng, L. Nanoporous nonprecious multi-metal alloys as multisite electrocatalysts for efficient overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kitiphatpiboon, N.; Feng, C.; Abudula, A.; Ma, Y.; Guan, G. Recent progress in transition-metal-oxide-based electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction in natural seawater splitting: A critical review. EScience 2023, 3, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Min, K.; Lee, H.; Kwon, H.; Shim, S.E.; Baeck, S.-H. Enhanced electrocatalytic performance of double-shell structured NixFe2-xP/NiFe2O4 for oxygen evolution reaction and anion exchange membrane water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.C.; Jin, M.; Zou, Y.; Wang, S.; Nie, Y.; Yao, D.; Tang, Y.J. Cathodic electrodeposition activation of NiFe-based metal–organic frameworks for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Rare Met. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Liu, X.; Ibragimov, A.B.; Gao, J. Recent strategies to improve the electroactivity of metal–organic frameworks for advanced electrocatalysis. Inf. Funct. Mater. 2024, 1, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Q. Metal-Organic Framework Composites for Catalysis. Matter 2019, 1, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Kathiresan, M.; Yun, K. Metal-organic and porous organic framework in electrocatalytic water splitting. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 126, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yang, Y.; Rushlow, J.; Huo, J.; Liu, Z.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Yin, R.; Wang, M.; Liang, R.; Wang, K.-Y.; et al. Development of the design and synthesis of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)—From large scale attempts, functional oriented modifications, to artificial intelligence (AI) predictions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 367–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Pang, H. Advances in electrochemistry of intrinsic conductive metal-organic frameworks and their composites: Mechanisms, synthesis and applications. Nano Energy 2024, 122, 109333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y. Progress of pristine metal-organic frameworks for electrocatalytic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 230, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.J.; Forgan, R.S. Postsynthetic Modification of Zirconium Metal-Organic Frameworks. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4310–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oar-Arteta, L.; Wezendonk, T.; Sun, X.; Kapteijn, F.; Gascon, J. Metal organic frameworks as precursors for the manufacture of advanced catalytic materials. Mater. Chem. Front. 2017, 1, 1709–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Pang, H. Enhanced active sites and stability in nano-MOFs for electrochemical energy storage through dual regulation by tannic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202311075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Dai, R.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z. Enhancing stability of tannic acid-FeIII nanofiltration membrane for water treatment: Intercoordination by metal–organic framework. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 17266–17277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Tian, X.; Ye, J.; Wang, L.; Akaniro, I.R.; Pan, J.; Dai, J. Constructing a highly permeable bioinspired rigid-flexible coupled membrane with a high content of spindle-type MOF: Efficient adsorption separation of water-soluble pollutants. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 20202–20214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazhayil, A.; Vazhayal, L.; Thomas, J.; Thomas, N. A comprehensive review on the recent developments in transition metal-based electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Han, H.; Lee, K.; Kang, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, S.H.; Jeon, H.; Ryu, J.H.; Chung, C.-Y.; Kim, K.M. Unraveling the mechanism of enhanced oxygen evolution reaction using NiOx@Fe3O4 decorated on surface-modified carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 17596–17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, S.; Lionet, Z.; Shigemitsu, H.; Toyao, T.; Kim, T.-H.; Horiuchi, Y.; Lee, S.W.; Matsuoka, M. Design of Fe-MOF-bpdc deposited with cobalt oxide (CoOx) nanoparticles for enhanced visible-light-promoted water oxidation reaction. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2020, 46, 2003–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.G.; Delgado-García, R.; Sanchez-Sanchez, M. Semiamorphous Fe-BDC: The missing link between the highly-demanded iron carboxylate MOF catalysts. Catal. Today 2022, 390, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.K.N.; Ho, H.L.; Nguyen, H.V.; Tran, B.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Bui, P.Q.T.; Bach, L.G. Photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B in aqueous phase by bimetallic metal-organic framework M/Fe-MOF (M = Co, Cu, and Mg). Open Chem. 2022, 20, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shi, J.; Jin, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, W. Facile synthesis of MIL-100 (Fe) under HF-free conditions and its application in the acetalization of aldehydes with diols. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 259, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Chen, W.; Xu, H.; Ding, M.; Lin, T.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L. Insights into the novel application of Fe-MOFs in ultrasound-assisted heterogeneous Fenton system: Efficiency, kinetics and mechanism. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Z.; Cao, Y.; Shen, L.; Au, C.; Jiang, L. Enhanced catalytic activity over MIL-100 (Fe) with coordinatively unsaturated Fe2+/Fe3+ sites for selective oxidation of H2S to sulfur. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Pei, C.; Ma, Y.; Park, H.S.; Wang, M. Boosting the Oxygen Evolution Reaction by Controllably Constructing FeNi3/C Nanorods. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Yan, S.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Ji, X. Favorable Amorphous–Crystalline Iron Oxyhydroxide Phase Boundaries for Boosted Alkaline Water Oxidation. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4911–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Choi, D.; Ramu, A.G.; Theerthagiri, J.; Choi, M.Y.; Yun, K. Hybridized bimetallic Ni–Fe and Ni–Co spinels infused N-doped porous carbon as bifunctional electrocatalysts for efficient overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qi, Q.; Mei, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, S. Rationally reconstructed metal–organic frameworks as robust oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Fang, D.; Fu, Y.; Gao, D.; Cheng, C.; Li, J. Partially amorphous NiFe layered double hydroxides enabling highly-efficiency oxygen evolution reaction at high current density. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 678, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, Z.; Yu, J.; Kong, A.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Peng, B.; Wang, G.; Yu, F.; Li, Y. Si doped Fe-MOF as efficient bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 81, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Hu, Z. V2O3/FeOOH with rich heterogeneous interfaces on Ni foam for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Catal. Commun. 2022, 162, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, N.; Han, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhai, C.; Chen, H.; Han, J.; Fang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, Z. Nanoporous RuO2 characterized by RuO(OH)2 surface phase as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting in alkaline solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 881, 114955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandekar, R.V.; Patil, S.S.; Sutar, R.B.; Jamadar, A.S.; Dongale, T.D.; Deshpande, N.G.; Yadav, J.B. Scalable Co-MOF thin films for OER: Achieving low overpotential and enhanced catalytic activity via surface reconstruction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 111, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Li, W.; Lei, Y.; He, X.; Chen, H.; Du, X.; Fang, W.; Wang, D.; Zhao, L. Interfacial engineering of ZIF-67 derived CoSe/Co(OH)2 catalysts for efficient overall water splitting. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 236, 109823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Ji, S.; Tian, X.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R. Ultrastable NiFeOOH/NiFe/Ni electrocatalysts prepared by in-situ electro-oxidation for oxygen evolution reaction at large current density. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 564, 150440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, X. ZIF-67-derived N-enriched porous carbon doped with Co, Fe and CoS for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, Z.; Deepak, D.; Kadadevar, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Nair, M.G.; Roy, S.S.; Das, A.; Mohapatra, S.R. Unveiling the synergy of MXene supported ZIF-8 hybrid catalyst for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 512, 132401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Kim, D.; Piao, Y. Metal-organic frameworks-derived novel nanostructured electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Carbon Energy 2021, 3, 66–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gopi, S.; Durai, M.; Yun, K. Tannic Acid-Induced Morphological and Electronic Tuning of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution. Catalysts 2025, 15, 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100991

Gopi S, Durai M, Yun K. Tannic Acid-Induced Morphological and Electronic Tuning of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution. Catalysts. 2025; 15(10):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100991

Chicago/Turabian StyleGopi, Sivalingam, Mani Durai, and Kyusik Yun. 2025. "Tannic Acid-Induced Morphological and Electronic Tuning of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution" Catalysts 15, no. 10: 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100991

APA StyleGopi, S., Durai, M., & Yun, K. (2025). Tannic Acid-Induced Morphological and Electronic Tuning of Metal–Organic Frameworks Toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution. Catalysts, 15(10), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15100991