1. Introduction

Rapid industrial expansion in recent years has resulted in environmental contamination, which has had a substantial influence on human health and the long-term development of the environment. As a result, many physicochemical and biological methods for environmental protection and pollutant removal have been developed [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The biological methods have certain limitations because they require long operation times and exhibit sensitivity to experimental conditions, failure to treat wastewater containing a high concentration of dyes, etc. Similarly, physicochemical techniques such as adsorption, precipitation, coagulation, etc., are ineffective due to secondary pollution caused by the use of chemicals. Alternatively, advanced oxidation processes are regarded as promising techniques for the treatment of dye-contaminated wastewater. In comparison to other chemical techniques, advanced oxidation processes are more effective at removing organic pollutants. Among advanced oxidation processes, nonselective photocatalytic oxidation process employing heterogeneous photocatalysts, with its low energy consumption and environmentally friendly nature, is recognized as a promising method for decomposing harmful pollutants to final non-toxic products [

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, photocatalytic reactions occur at room temperature, and solar irradiation can activate the photocatalyst.

Semiconductors such as TiO

2, ZnO, Fe

2O

3, CdS, etc. have been used and extensively investigated as photocatalysts in the degradation of numerous organic pollutants due to a good combination of their electronic structure, light absorption properties, and charge transport characteristics [

11,

12,

13,

14]. In recent years, MgO [

14,

15,

16,

17] and MgAl

2O

4 [

18,

19,

20] have been recognized to be efficient for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants, because MgO and MgAl

2O

4 have high concentrations of surface vacancies and other defects [

21,

22,

23]. Active centers of heterogeneous photocatalytic reactions were closely related to surface vacancies, which determine the electron transfer between reactants and photocatalysts [

24,

25].

Currently, MgO and MgAl2O4 photocatalysts are synthesized in powder form, which restricts their practical applications due to the high cost of photocatalyst separation and recovery from suspension. Moreover, photocatalyst particles easily form agglomerates that are not suitable for use in flow systems. Photocatalytic materials supported on a stable substrate can solve this problem. In this work, we have shown that the plasma electrolytic oxidation process (PEO) of AZ31 magnesium alloy in aluminate electrolyte can be used for the formation of photocatalytic active coatings that contain both MgO and MgAl2O4 phases. Furthermore, the addition of ZnO particles to electrolyte enhances the photocatalytic activity of formed heterogeneous catalyst.

PEO is a cost-effective, energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly electrochemical process that produces a stable oxide coating on the surface of lightweight metals or metal alloys (aluminum, magnesium, zirconium, titanium, and so on) [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The PEO process is coupled with the plasma formation, as evidenced by the presence of micro-discharges on the metal surface. Due to the elevated local temperature (~10

4 K) and pressure (~10

2 MPa), a number of processes, including chemical, electrochemical, thermodynamic, and plasma–chemical reactions, take place at the micro-discharge locations. The structure, content, and morphology of the resulting oxide coatings are altered by these processes. The oxide coatings created by the PEO technique often have constituent species originating from both metal and electrolyte in both crystalline and amorphous phases.

2. Results

2.1. Structural and Photocatalytic Properties of MgAl Coating

Time variation of voltage during anodiation of AZ31 magnesium alloy in 5 g/L NaAlO

2 is shown in

Figure 1a. A linear increase in anodization voltage characterizes the rather uniform growth of the compact barrier oxide film at constant current density [

30]. This is followed by a visible deviation from linearity in the voltage versus time graph, beginning with the breakdown voltage. As the anodization voltage approached the breakdown voltage, a large number of visible sparks appeared, uniformly dispersed over the surface. An SEM micrograph of the surface coating formed after 10 min is shown in

Figure 1b. A number of discharge channels and regions resulting from the rapid cooling of molten material were present on the surface. An SEM micrograph of a polished cross section of the MgAl coating in

Figure 1c shows that a relatively dense layer, about 22 μm thick, was formed after 10 min of processing. The main elements of the coating were Mg, Al, and O (

Figure 1d).

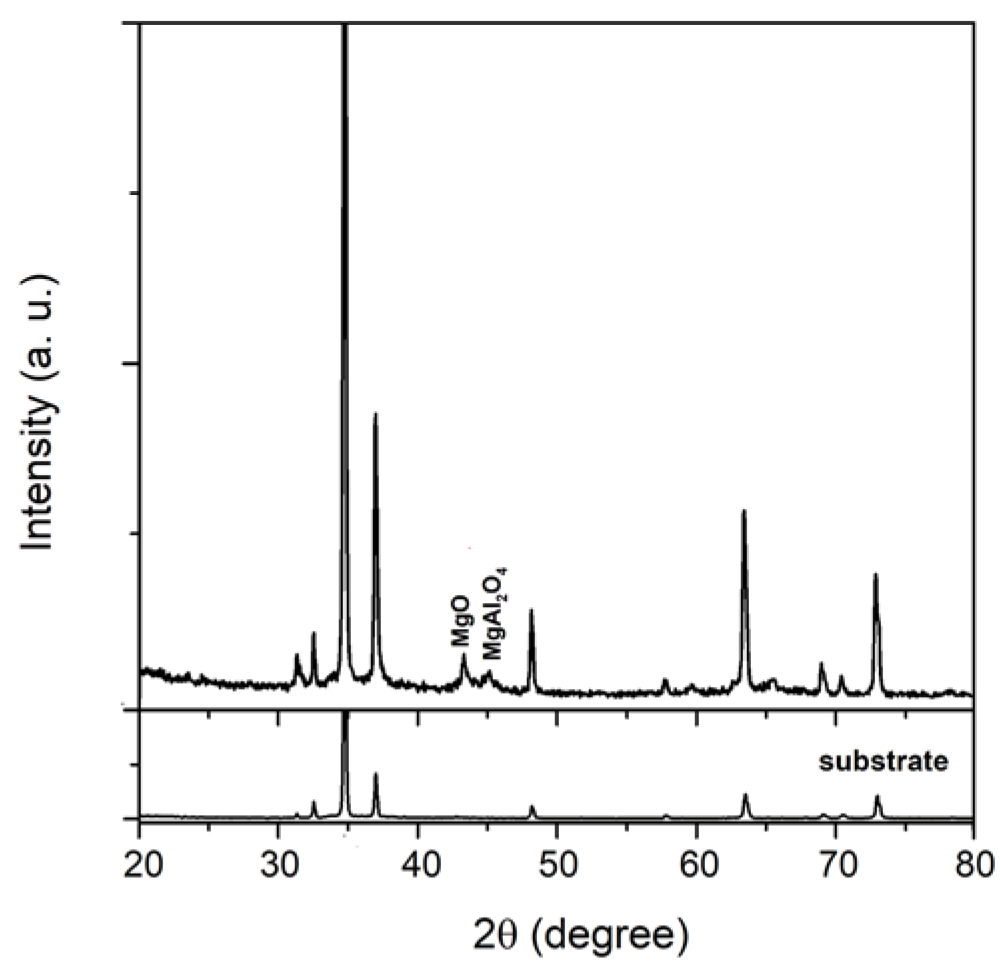

The XRD pattern of the MgAl coating is shown in

Figure 2. The coating was partially crystallized, and two weak peaks at 2θ angle at about 43.3° and 45.1° can be detected, corresponding to the (200) reflection of MgO (JCPDS card No. 79-0612) and (400) reflection of MgAl

2O

4 (JCPDS card No. 77-0435). Due to X-ray penetration through the porous oxide layer and reflection off the substrate, the diffraction peaks from the substrate were significant. MgO and MgAl

2O

4 phases can form as a result of an interaction between the AZ31 substrate and the electrolyte. MgO is formed by the reaction of outward migration of Mg

2+ ions from the substrate to the micro-discharge channels and inward migration of O

2− ions from the electrolyte to the micro-discharge channels by the following reaction [

31]:

NaAlO

2 is dissolved in distilled water (

) and reacts with Mg

2+ according to the following reaction [

32]:

The photodegradation of methyl orange (MO) using the formed MgAl coating as a photocatalyst after five consecutive runs is presented in

Figure 3a. C

0 is the initial concentration of MO, while C is the concentration after time t. After each run, the sample was rinsed with water, dried, and reused in the next photocatalytic run. The results reveal that the PA of the coating remained practically unaltered after multiple successive runs, indicating that there was no significant attrition of photocatalyst from the support or catalyst poisoning. The efficiency of MgAl coating in MO degradation was much higher than that of TiO

2 [

33], MgO [

34], ZrO

2 [

35], and Nb

2O

5 [

36] coatings formed by PEO on titanium, AZ31 magnesium alloy, zirconium, and niobium substrate, respectively (

Figure 3b).

The light-harvesting performance of MgAl coating was investigated using DRS, and the result is given in

Figure 3c. A broad absorption band in the mid-UV region is observed and can be attributed to the large bandgap of MgO [

14] and MgAl

2O

4 [

37]. Although this absorption band of MgAl coating is detrimental for photocatalytic applications using the sunlight as an energy source for the photoreaction, the high concentration of different types of oxygen vacancies and other defects generated in MgAl during the PEO processing results in good PA of MgAl coating. The PL emission spectrum of the MgAl coating excited with 265 nm radiation is shown in

Figure 3d. Three dominant PL bands can be observed in the spectrum. The UV emission band centered at around 325 nm can be attributed to F

+ centers in MgO, whereas the band in the range from 360 nm to 600 nm can be attributed to structural defects in the coatings such as Mg vacancies and interstitials [

14,

38]. The band with a maximum centered at about 720 nm can be associated with F

+ centers in MgAl

2O

4 [

39].

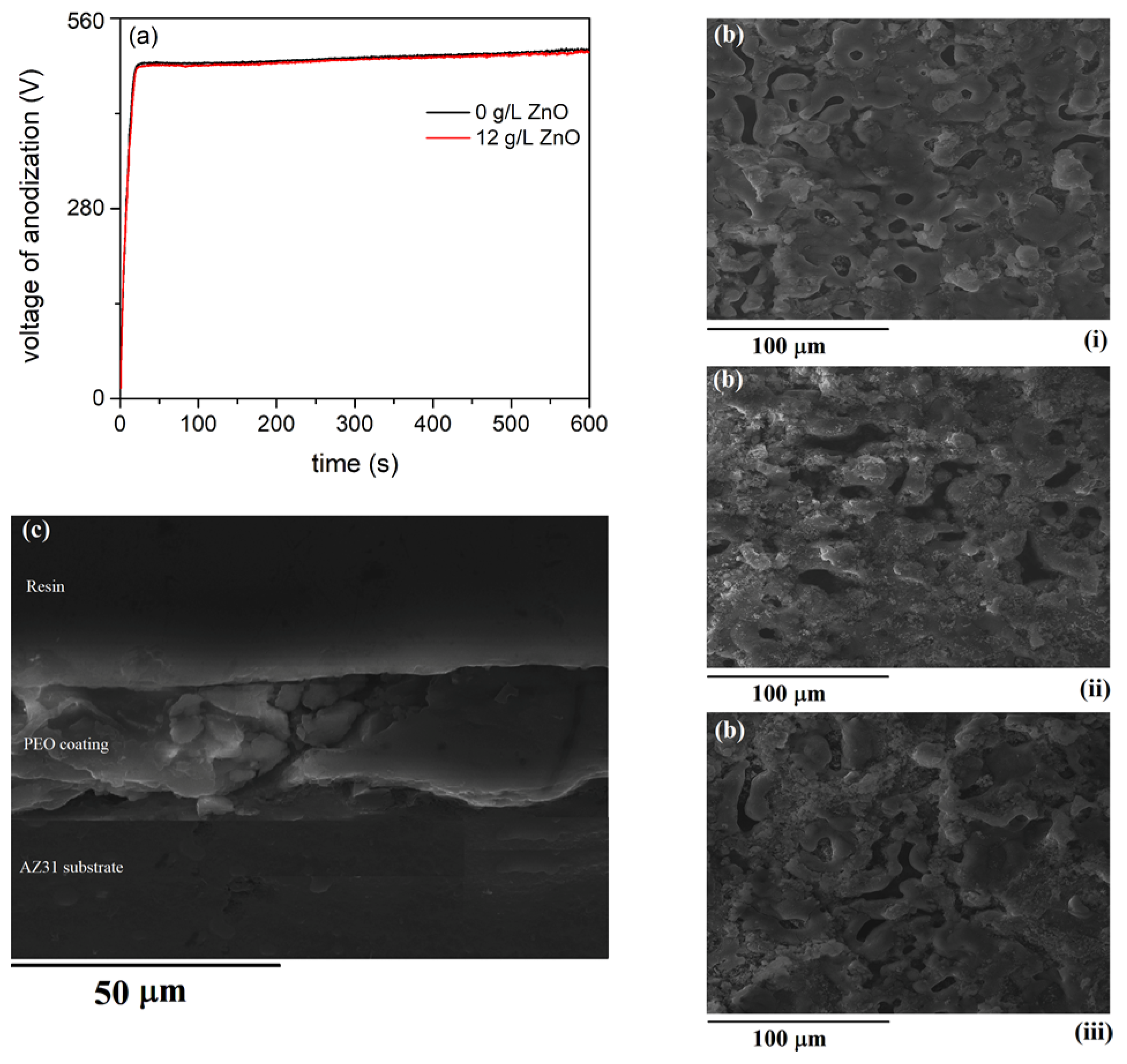

2.2. Structural and Photocatalytic Properties of MgAl/ZnO Coatings

The addition of ZnO particles to the aluminate electrolyte has no significant effect on the voltage-time characteristic of the PEO process, the morphology, and the thickness of the formed coatings (

Figure 4).

Table 1 shows the elemental composition of the coatings in

Figure 4b as determined by integrated EDS analysis (the relative errors are less than 2%). The main elements found in the coatings were Mg, O, Al, and Zn. The content of Zn in formed coatings increased as the concentration of ZnO particles in aluminate electrolyte increased. The elemental distribution on the surface of the coating formed in aluminate electrolyte with the addition of 12 g/L ZnO (

Figure 5) shows that all elements were distributed rather uniformly.

Figure 6 shows the XRD patterns of coatings formed in aluminate electrolyte with the addition of various concentrations of ZnO particles, as well as the XRD pattern of pure ZnO powder (JCPDS Card No. 89-1397).

The diffraction maxima of ZnO can be seen along with the diffraction maxima arising from MgO and MgAl

2O

4. These results indicate that ZnO particles were incorporated into the coatings. Namely, the melting point of ZnO particles was roughly 1975 °C, which is substantially lower than the plasma electron temperature inside the micro-discharge channels [

40]. Molten ZnO particles could produce mixed-oxide coatings inside the discharge channels by reacting with other electrolyte and substrate components.

MgAl/ZnO coatings had significantly higher PA than MgAl coatings (

Figure 7a). The highest PA was observed for MgAl/ZnO coating formed in aluminate electrolyte with the addition of 12 g/L of ZnO particles. After 8 h of irradiation, the initial pH value of MO aqueous solution of 6.2 increased to 6.9 for the sample PEO processed in electrolyte with 12 g/L ZnO. This was expected, because at very high values of MO conversion (97%), the pH value of the initial solution approaches the value of pure water. The incorporation of ZnO particles into MgAl coatings had a considerable impact on the absorption and PL properties of the coatings. When compared to MgAl (

Figure 7b), the DRS of MgAl/ZnO coatings shifted to higher wavelengths and exhibited a band edge at around 385 nm (~3.2 eV), which was due to photo excitation from the valence band to the conduction band of ZnO in coatings [

41].

PL emission spectra of MgAl/ZnO coatings are shown in

Figure 7c. The overall PL of MgAl/ZnO coatings is a sum of PL originating from MgAl coatings and ZnO. The sharp near-ultraviolet emission band centered at about 380 nm is attributed to the radiative recombination of free excitons in ZnO [

42]. Further, ZnO particles showed a broad green emission band centered at about 510 nm, which originated from oxygen vacancy and zinc vacancy-related defects [

43]. This PL is superimposed in the range from 400 nm to 600 nm on the PL of the MgAl. The PL intensity of each of these PL bands increased as the concentration of ZnO incorporated into MgAl coatings increased.

3. Discussion

Many active oxygen species are produced by photogenerated electrons and holes on photocatalytic solid surfaces, including superoxide anion radical (

•O

2−), hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), singlet oxygen (

1O

2), and hydroxyl radical (

•OH), which are involved in oxidative and reductive reactions [

44].

•OH radicals are primarily responsible for the decomposition of organic pollutants [

45]. Electrons are excited from the valence bands to the conduction bands of MgO and MgAl

2O

4 when MgAl coatings are irradiated, leaving photo-generated holes in the valence bands of MgO and MgAl

2O

4. The holes react with water molecules or hydroxyl groups to form

•OH, which undergo an oxidation process with the MO to convert it into CO

2 and H

2O [

46,

47]. In the case of ZnO particles modified with MgAl coatings, a similar process occurs when ZnO particles are subjected to UV irradiation [

48], resulting in an increase in

•OH radicals and hence an increase in PA of MgAl/ZnO compared to MgAl.

PL measurements on the surface of the MgAl coating and MgAl/ZnO coating generated in aluminate electrolyte with addition of 12 g/L ZnO particles were used to test the production of

•OH radicals (

Figure 8a). The intensity of PL is related to the amount of

•OH radicals generated [

49]. The PL intensity of both MgAl and MgAl/ZnO samples increased with illumination time, while the MgAl/ZnO coating had a greater PL intensity at 425 nm emission than MgAl. This result was expected, because

•OH radicals in MgAl/ZnO coating produce not only MgO and MgAl

2O

4, but also ZnO, the most active photocatalyst.

The role of holes (h

+) in photocatalytic degradation of MO was investigated using 1 mM of triethanolamine (TEOA) as a radical scavenger. The test was performed with the most active photocatalyst (MgAl/ZnO coating formed in aluminate electrolyte with addition of 12 g/L ZnO) under the same conditions of photocatalytic degradation. After irradiation, the photocatalytic degradation of MO with the addition of TEOA was only slightly reduced;

Figure 8b. This result indicates that holes (h

+) had no significant contribution to the photocatalytic degradation of MO and that

•OH radicals played a main role in the MO photodegradation [

50].

The stability of MgAl/ZnO photocatalyst was investigated using MgAl/ZnO coating produced in aluminate electrolyte with addition of 12 g/L ZnO, as shown in

Figure 9a, demonstrating the excellent stability of MgAl/ZnO photocatalyst. Furthermore, after five runs, the morphology (

Figure 9b), compositions (

Figure 9c), and optical absorption (

Figure 9d) did not change, indicating that the MgAl/ZnO coatings formed by PEO are dependable and efficient photocatalysts.

4. Materials and Methods

PEO coatings were formed on rectangular samples of AZ31 magnesium alloy (96% Mg, 3% Al, 1% Zn, Alfa Aesar) with dimensions of 25 mm × 10 mm × 0.81 mm. The samples were ultrasonically cleaned with acetone and dried in a warm air stream. Following that, the samples were covered with insulating resin, leaving only the 15 mm × 10 mm active surface exposed to the electrolyte.

Figure 10 depicts a schematic diagram of the PEO experimental setup. The electrolytic cell was a double-walled glass cell with water cooling. To ensure the homogeneous distribution of particles in the electrolytic cell, the electrolyte was stirred with a magnetic stirrer. Anode samples of AZ31 magnesium alloy were used and placed in the center of the electrolytic cell, surrounded by a tubular stainless-steel cathode.

PEO coatings were formed in an aluminate electrolyte (5 g/L NaAlO2) with the addition of ZnO particles in concentrations ranging from 4 g/L to 12 g/L. PEO was performed for 10 min at a constant current density of 150 mA/cm2. The electrolyte temperature was kept at (20 ± 1) °C. After the PEO process was completed, the samples were rinsed with distilled water and air dried.

A scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL 840A, Tokyo, Japan) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford, UK) was used to examine the morphology and elemental composition of the PEO coatings. The phase composition of the PEO coatings was tested by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer, Tokyo, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation with 2θ ranging from 25° to 75° (0.05° step and a rate of 2°/min) and working at 40 kV and 40 mA with Bragg–Brentano geometry. UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS, Shimadzu UV-3600 spectrophotometer, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an integrating sphere) was used to evaluate the light absorption ability of the PEO coatings by scanning over a range of 200 nm to 600 nm. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the PEO coatings were collected with a Horiba Jobin-Yvon spectrofluorometer (Edison, NJ, USA) equipped with a 450 W xenon lamp as the excitation light source. The emission PL spectra were measured with an excitation wavelength of 265 nm over a wavelength range of 300 nm to 775 nm.

The photoactivity (PA) of PEO coatings was determined using the degradation of methyl orange (MO). MO was chosen as the model compound for azo dyes. The tests were carried out at 20 °C in a 6.8 cm diameter open cylindrical thermostatic Pyrex glass reactor. The samples (15 mm × 10 mm) were placed 5 mm above the reactor bottom on the steel wire holder. The solution (10 cm3) was mixed with a rotating magnet placed beneath the holder (500 rpm). The initial MO concentration was 8 mg/L. As a light source, a solar radiation simulator lamp (Solimed BH Quarzlampen, Leipzig, Germany) with a power consumption of 300 W was placed 25 cm above the top surface of the test solution. PA was calculated by measuring the MO decomposition after an appropriate light exposure time. A spectrophotometer (UV-Vis Thermo Electron Nicolet Evolution 500, UK) was used to measure the MO concentration using the maximum MO absorption peak at 464 nm.

Prior to the PA measurements, the adsorption of MO was tested in the dark in the presence of PEO coatings. The concentration of MO remained nearly constant after 60 min, indicating that adsorption of MO was negligible. In addition, MO was tested for photolysis in the absence of a photocatalyst using simulated solar light. There was no difference in MO concentration after 12 h of irradiation, indicating that the MO degradation was caused solely by the presence of the photocatalyst.

In order to detect the formation of free hydroxyl radicals (

•OH) on the illuminated PEO coatings, PL measurements were performed using terephthalic acid, which is known to react with

•OH radicals and produces highly fluorescent 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid that exhibits a PL peak at 425 nm [

45]. The experiment was carried out at room temperature. The PEO coatings were placed in a Pyrex glass reactor containing 10 mL of 5 × 10

−4 mol/L terephthalic acid diluted in a 2 × 10

−3 mol/L NaOH aqueous solution. The same lamp used for PA measurements was used as the light source. On a Horiba Jobin-Yvon Fluorolog FL3-22 spectrofluorometer, PL spectra of reaction solution were measured using an excitation wavelength of 315 nm.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the PEO process of AZ31 magnesium alloy in aluminate electrolyte without and with ZnO particle addition is a cost-effective and efficient approach for producing MgAl and MgAl/ZnO photocatalysts. After 8 h of irradiation, the PA of the MgAl coating was around 58%. When MgAl coatings were combined with ZnO particles, their PA increased. The PA for MgAl/ZnO coatings formed in aluminate electrolyte with the addition of ZnO particles in concentrations of 4 g/L, 8 g/L, and 12 g/L, were around 69%, 86%, and 97%, respectively. After multiple successive cycles, the PA, morphology, compositions, and optical absorption of the formed photocatalysts did not change, suggesting their chemical and physical stability, which is an important prerequisite for potential applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S.; validation, S.S., investigation, S.S., N.R. and R.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., N.R. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (Grants 451-03-9/2021-14/200162 and 451-03-9/2021-14/200026) and by the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 823942 (FUNCOAT).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge dr Nenad Tadić for his admirable work in preparation samples for SEM/EDS measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rekhate, C.V.; Srivastava, J.K. Recent advances in ozone-based advanced oxidation processes for treatment of wastewater-A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, F.; Saravanakumar, K.; Maheskumar, V.; Njaramba, L.K.; Yoon, Y.; Park, C.M. Application of perovskite oxides and their composites for degrading organic pollutants from wastewater using advanced oxidation processes: Review of the recent progress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Qiu, W.; Peng, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, D.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J. A Review on additives-assisted ultrasound for organic pollutants degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorayyaei, S.; Raji, F. Rahbar-Kelishami, A.; Ashrafizadeh, S.N. Combination of electrocoagulation and adsorption processes to remove methyl orange from aqueous solution. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, R.; Purchase, D.; Saratale, G.D.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Hussain, C.M.; Mulla, S.I.; Bharagava, R.N. Degradation mechanism and toxicity reduction of methyl orange dye by a newly isolated bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa MZ520730. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 43, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, K.-W.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Xia, M.; Gerson, A.R. Decolorization of synthetic Methyl Orange wastewater by electrocoagulation with periodic reversal of electrodes and optimization by RSM. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2014, 92, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramutshatsha-Makhwedzha, D.; Mavhungu, A.; Moropeng, M.L.; Mbaya, R. Activated carbon derived from waste orange and lemon peels for the adsorption of methyl orange and methylene blue dyes from wastewater. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Khan, F.S.A.; Mubarak, N.M.; Khalid, M.; Tan, Y.H.; Mazari, S.A.; Karri, R.R.; Abdullah, E.C. Emerging pollutants and their removal using visible-light responsive photocatalysis-A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, J.; Shangguan, W. A review on photocatalysis in antibiotic wastewater: Pollutant degradation and hydrogen production. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 1440–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, Z.H.; Graimed, B.H. Recent developments in industrial organic degradation via semiconductor heterojunctions and the parameters affecting the photocatalytic process: A review study. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 47, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetchakun, K.; Wetchakun, N.; Sakulsermsuk, S. An overview of solar/visible light-driven heterogeneous photocatalysis for water purification: TiO2- and ZnO-based photocatalysts used in suspension photoreactors. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, R.; Masudy-Panah, S.; Tanhaei, M.; Farahani, M.H.D.A.; Jiangyong, H. A review on the synthesis of the various types of anatase TiO2 facets and their applications for photocatalysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Chun, D.-M. α-Fe2O3 as a photocatalytic material: A review. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 498, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageshwari, K.; Mali, S.S.; Sathyamoorthy, R.; Patil, P.S. Template-free synthesis of MgO nanoparticles for effective photocatalytic applications. Powder Technol. 2013, 249, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supin, K.K.; Saji, A.; Chanda, A.; Vasundhara, M. Effects of calcinations temperatures on structural, optical and magnetic properties of MgO nanoflakes and its photocatalytic applications. Opt. Mater. 2022, 132, 112777. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, S.; Moussavi, G.; Giannakis, S. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin under UVA-LED, using S,N-doped MgO nanoparticles: Synthesis, parametrization and mechanistic interpretation. J. Mol. Liq. 2012, 324, 114831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Velavan, R.; Batoo, K.M.; Raslanc, E.H. Microstructure, optical and photocatalytic properties of MgO nanoparticles. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.Y.; Ahmed, I.S.; Samir, I. A novel synthetic route for magnesium aluminate (MgAl2O4) nanoparticles using sol–gel auto combustion method and their photocatalytic properties. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 131, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, F.; Zhao, Y.; Liua, Y.; Hao, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhao, D. Solution combustion synthesis and visible light-induced photocatalytic activity of mixed amorphous and crystalline MgAl2O4 nanopowders. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 173, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmasi, M.Z.; Kazemeini, M.; Sadjadi, S.; Nematollahi, R. Spinel MgAl2O4 nanospheres coupled with modified graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets as an efficient Z-scheme photocatalyst for photodegradation of organic contaminants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 585, 152615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Zhao, X.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Li, C.; Liu, K.; Du, X.; Li, W.; Feng, J.; et al. Superior selective adsorption of MgO with abundant oxygen vacancies to removal and recycle reactive dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Ghosh, P.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Kadam, R.M.; Arya, A. Defects induced changes in the electronic structures of MgO and their correlation with the optical properties: A special case of electron–hole recombination from the conduction band. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 96398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.A.; Murphy, S.T.; Grimes, R.W.; Bacorisen, D.; Smith, R.; Uberuaga, B.P.; Sickafus, K.E. Defect processes in MgAl2O4 spinel. Solid State Sci. 2008, 10, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; He, J.; Lin, Z.; Huang, F.; Liu, C.; Wang, M. Vacancy engineering in nanostructured semiconductors for enhancing photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 17143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.; Zhang, J.-W.; Wu, Y.-W.; Pan, L.; Shi, C.; Zou, J.-J. Role of vacancies in photocatalysis: A review of recent progress. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 3599–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R.; Perić, M. Investigation of plasma electrolytic oxidation on valve metals by means of molecular spectroscopy-a review. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 25759–25789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseem, M.; Fatimah, S.; Nashrah, N.; Ko, Y.G. Recent progress in surface modification of metals coated by plasma electrolytic oxidation: Principle, structure, and performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 117, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, S.; Menezes, P.V.; Maccione, R.; Jacob, T.; Menezes, P.L. Plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) process—Processing, properties, and applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darband, G.B.; Aliofkhazraei, M.; Hamghalam, P.; Valizade, N. Plasma electrolytic oxidation of magnesium and its alloys: Mechanism, properties and applications. J. Magnes. Alloys 2017, 5, 74–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R.; Radić-Perić, J.; Perić, M. Characterization of plasma electrolytic oxidation of magnesium alloy AZ31 in alkaline solution containing fluoride. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 273, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshid, S.; Kharaziha, M. Micro and nano-enabled approaches to improve the performance of plasma electrolytic oxidation coated magnesium alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2021, 9, 1487–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampatirao, H.; Radhakrishnapillai, S.; Dondapati, S.; Parfenov, E.; Nagumothu, R. Developments in plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) coatings for biodegradable magnesium alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Radić, N.; Grbić, B.; Maletić, S.; Stefanov, P.; Pačevski, A.; Vasilić, R. Structural, photoluminescent and photocatalytic properties of TiO2:Eu3+ coatings formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 370, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Tadić, N.; Radić, N.; Grbić, B.; Vasilić, R. MgO/ZnO coatings formed on magnesium alloy AZ31 by plasma electrolytic oxidation: Structural, photoluminescence and photocatalytic investigation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 310, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Vasilić, R.; Radić, N.; Grbić, B. Zirconia films formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation: Photoluminescent and photocatalytic properties. Opt. Mater. 2015, 40, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Tadić, N.; Radić, N.; Stefanov, P.; Grbić, B.; Vasilić, R. Anodic luminescence, structural, photoluminescent, and photocatalytic properties of anodic oxide films grown on niobium in phosphoric acid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadeeshwaran, C.; Madhan, K.; Murugaraj, R. Size effect and order–disorder phase transition in MgAl2O4: Synthesized by co-precipitation method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 18923–18934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jintakosol, T.; Singjai, P. Effect of annealing treatment on luminescence property of MgO nanowires. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2009, 9, 1288–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Ghosh, P.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Kadam, R.M.; Arya, A. An insight into the various defects-induced emission in MgAl2O4 and their tunability with phase behavior: Combined experimental and theoretical approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 4016–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovović, J.; Stojadinović, S.; Šišović, N.M.; Konjević, N. Spectroscopic study of plasma during electrolytic oxidation of magnesium- and aluminium-alloy. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 2012, 113, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeeta, M.; Karthik, K.V.; Ravishankar, R.; Anantharaju, K.S.; Nagabhushana, H.; Jeetendra, K.; Vidya, Y.S.; Renuka, L. Synthesis of ZnO, MgO and ZnO/MgO by solution combustion method: Characterization and photocatalytic studies. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 11791–11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpo, M.; Kubokawa, Y. Photoluminescence of zinc oxide powder as a probe of electron-hole surface processes. J. Phys. Chem. 1984, 88, 5556–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojadinović, S.; Tadić, N.; Radić, N.; Stojadinović, B.; Grbić, B.; Vasilić, R. Synthesis and characterization of Al2O3/ZnO coatings formed by plasma electrolytic oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 276, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosaka, Y.; Nosaka, A.Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11302–11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedanekar, R.S.; Shaikh, S.K.; Rajpure, K.Y. Thin film photocatalysis for environmental remediation: A status review. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2020, 20, 931–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Li, B.; Mu, H.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Li, F. Deep insight into the photocatalytic activity and electronic structure of amorphous earth-abundant MgAl2O4. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, A.; Ramakrishnappa, T.; Archana, S.; Reddy Yadav, L.S.; Shilpa, B.M.; Nagaraju, G.; Jayanna, B.K. Green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Phyllanthus emblica for Evans blue degradation and antibacterial activity. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanakousar, F.M.; Vidyasagar, C.C.; Jimenez-Perez, V.M.; Prakash, K. Recent progress on visible-light-driven metal and non-metal doped ZnO nanostructures for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 140, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Fujishima, A.; Watanabe, T.; Hashimoto, K. Detection of active oxidative species in TiO2 photocatalysis using the fluorescence technique. Electrochem. Commun. 2000, 2, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Fazal, T.; Iqbal, I.; Alaud Din, A.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, A.; Razzaq, A.; Zulfiqar, A.; Saif Ur Rehman, M.; Park, Y.-K. Integrated adsorptive and photocatalytic degradation of pharmaceutical micropollutant, ciprofloxacin employing biochar-ZnO composite photocatalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 115, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).