Electrochemical Activity of Original and Infiltrated Fe-Doped Ba(Ce,Zr,Y)O3-Based Electrodes to Be Used for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

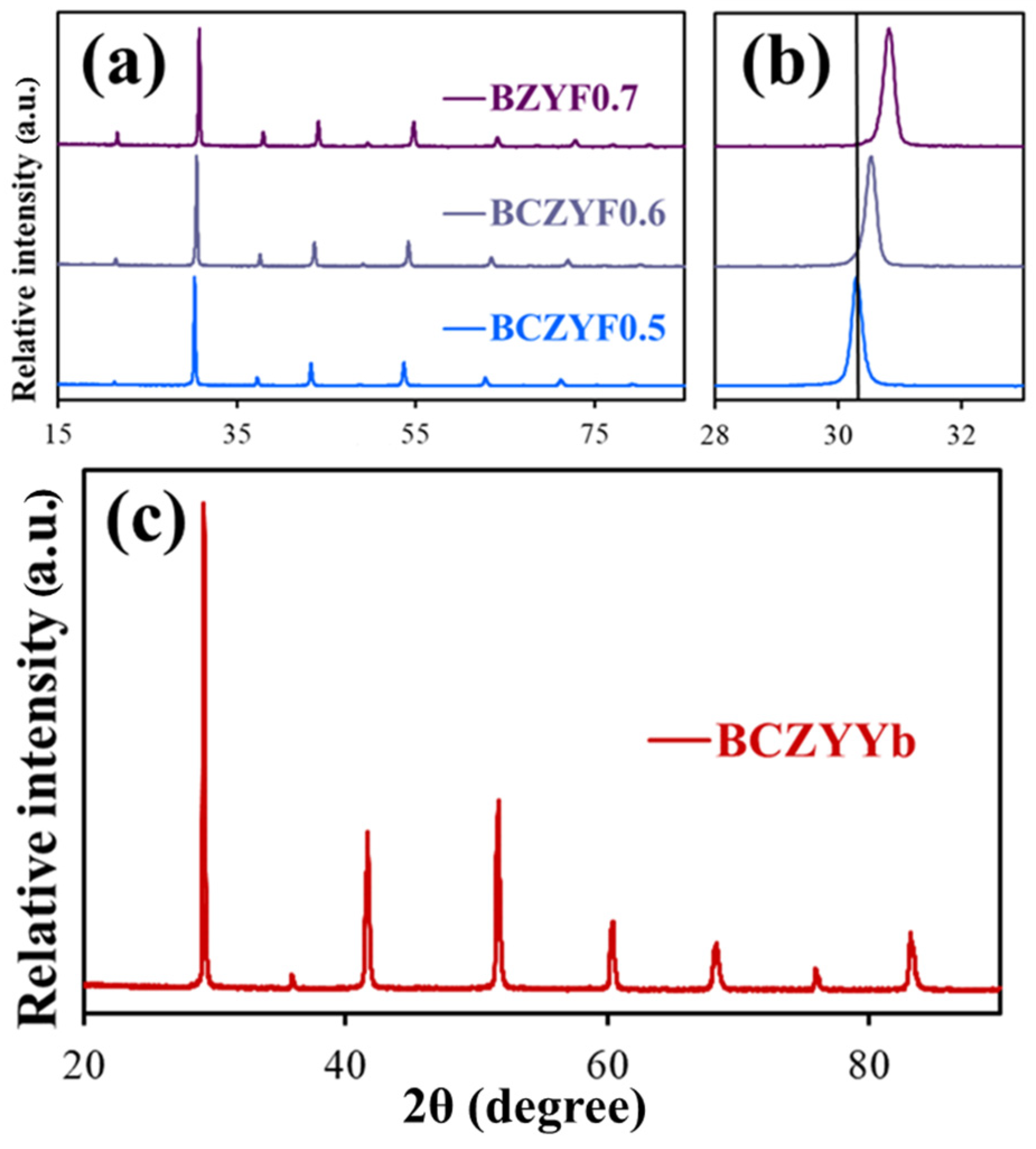

2.1. Quality of the Prepared Materials

2.2. Performance of the BaFexCe0.7−xZr0.2Y0.1O3−δ-Based Electrodes on Symmetrically Designed Cells

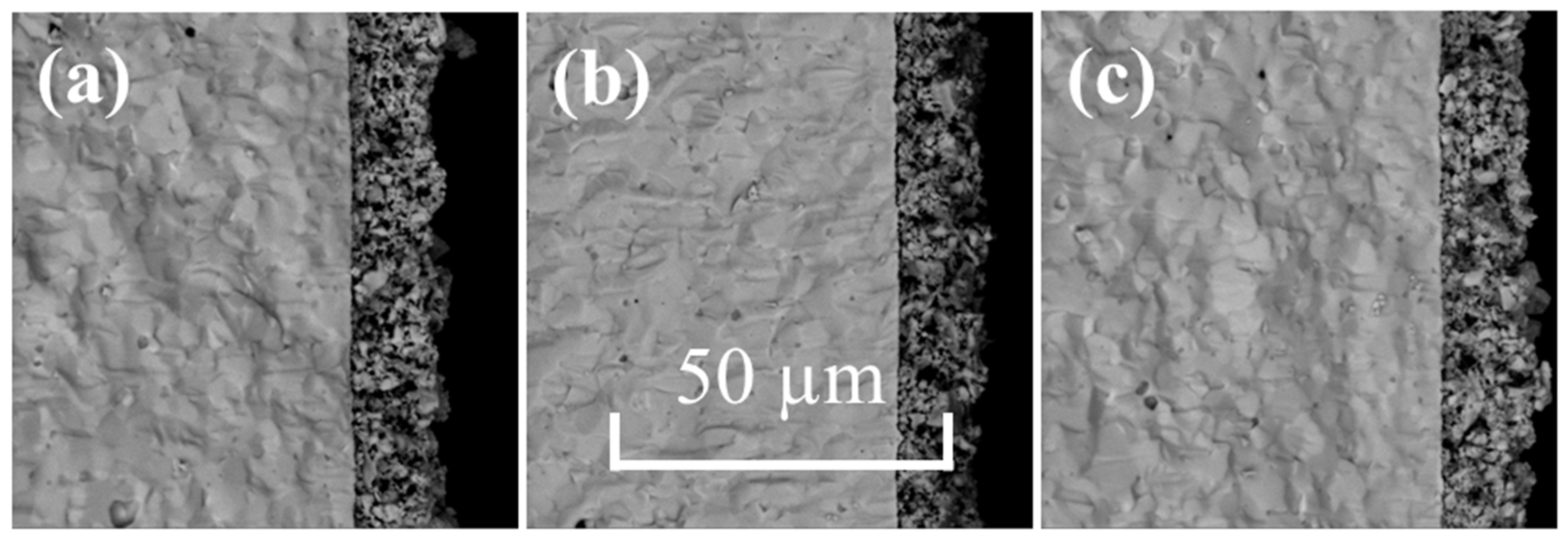

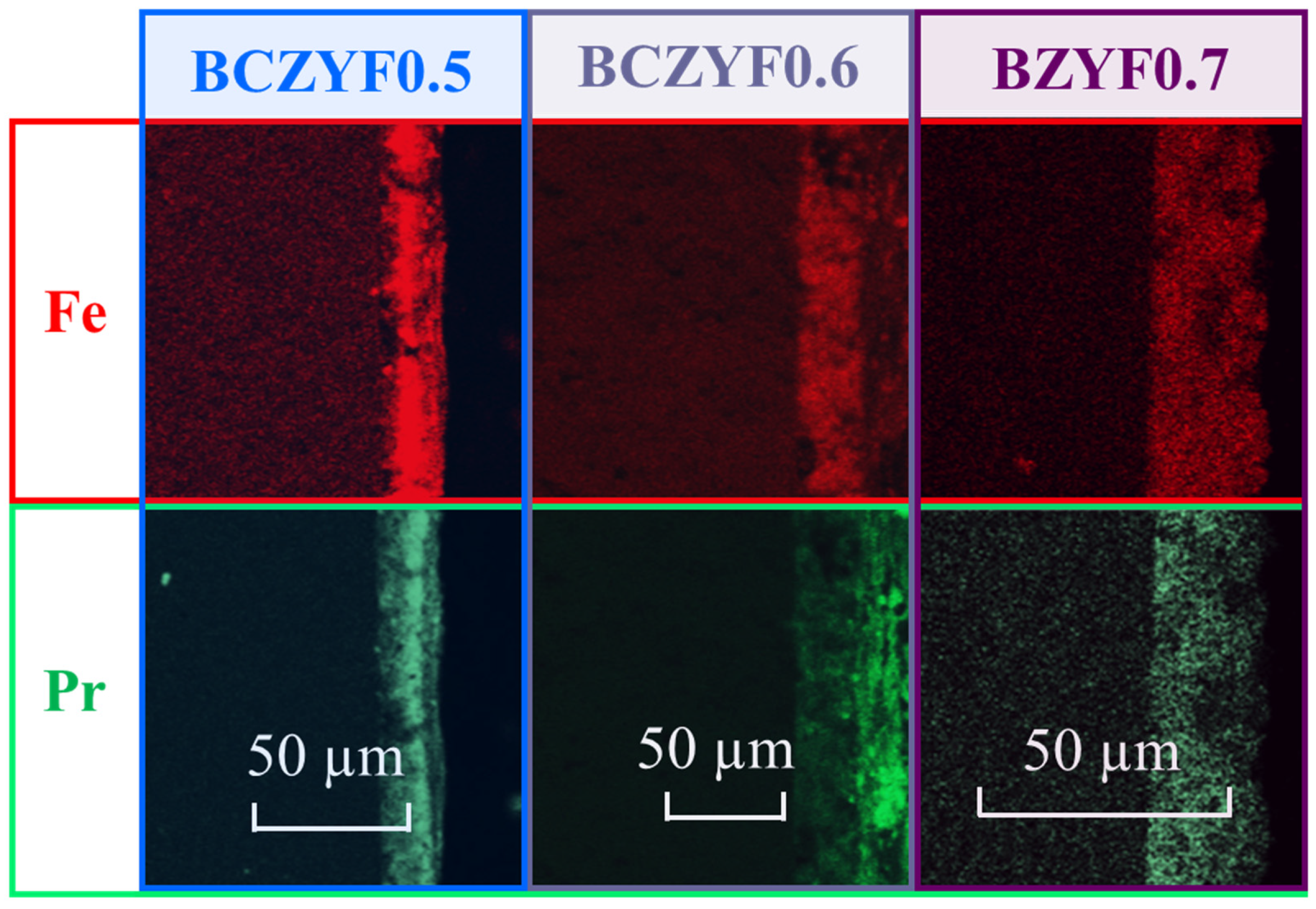

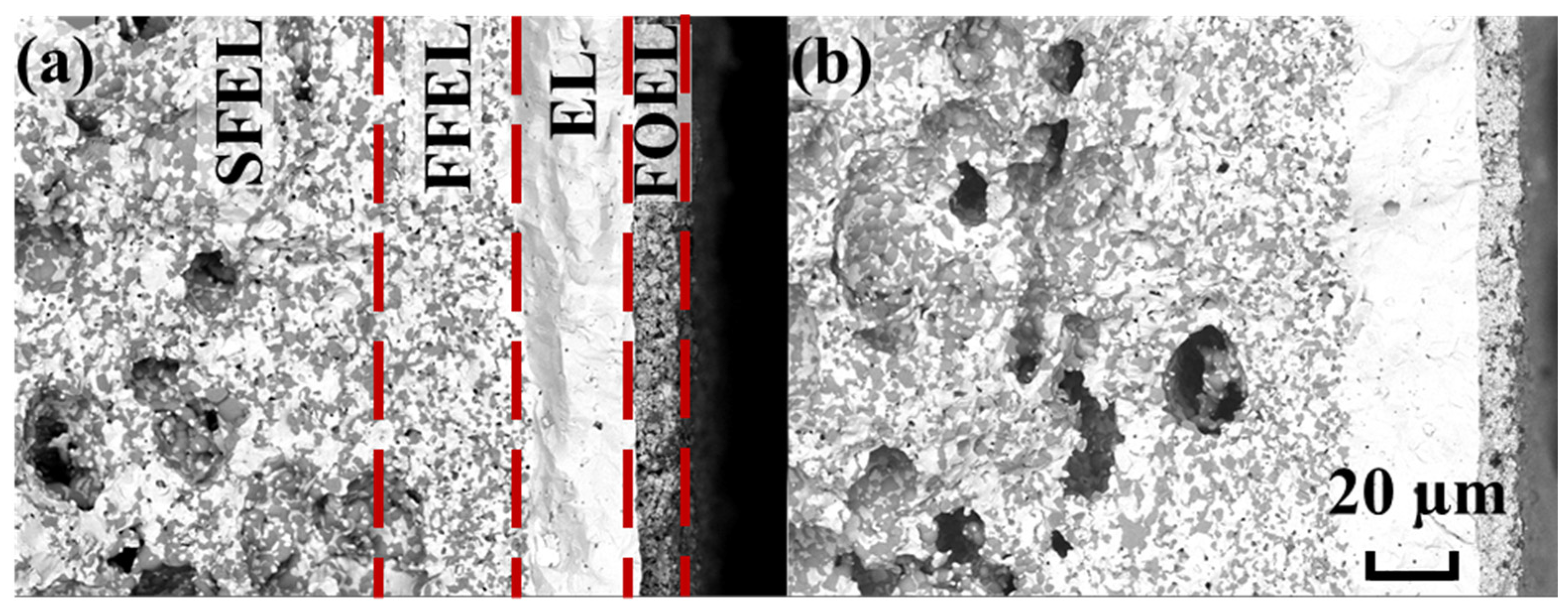

2.2.1. Microstructural Analysis

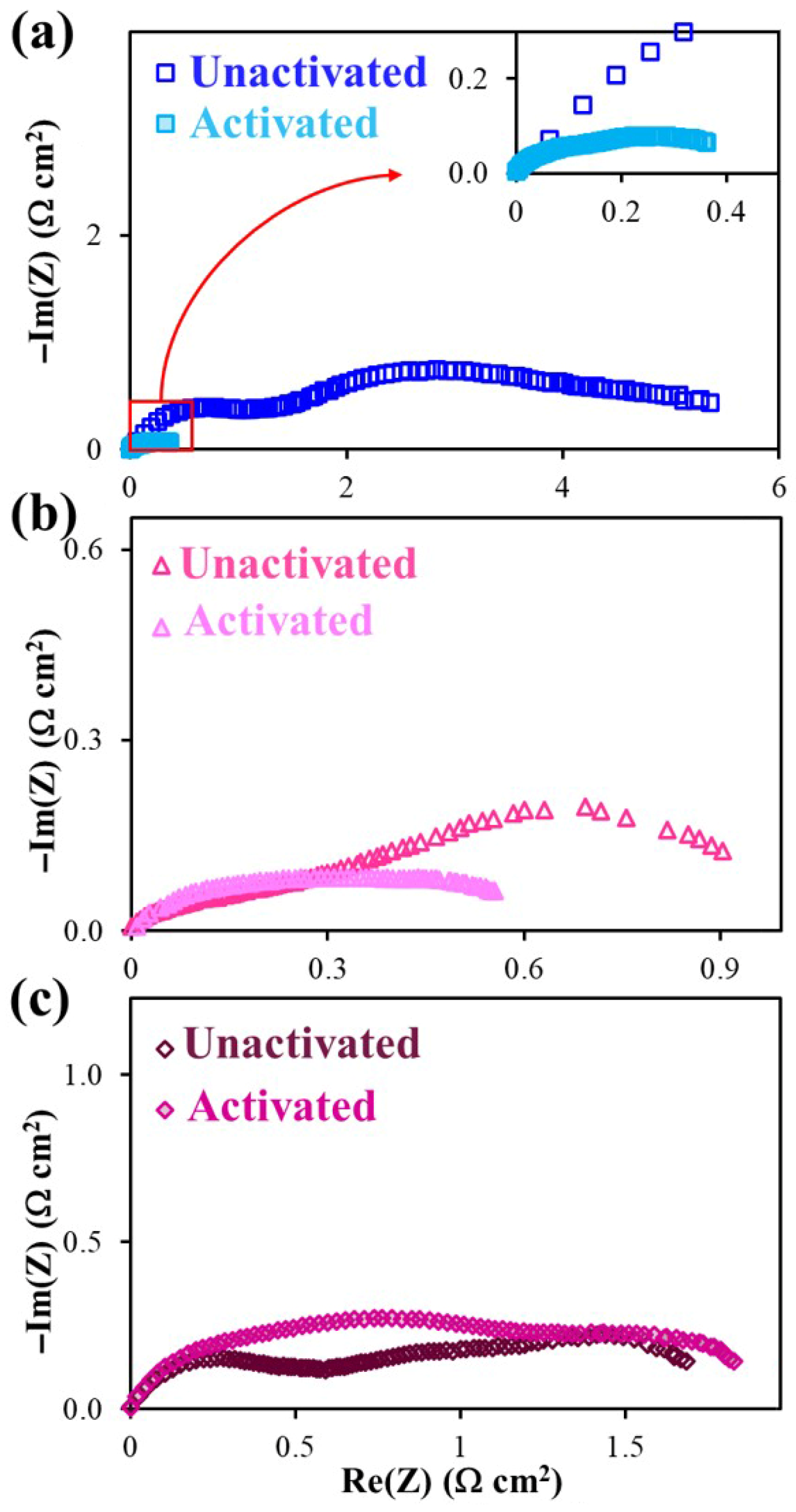

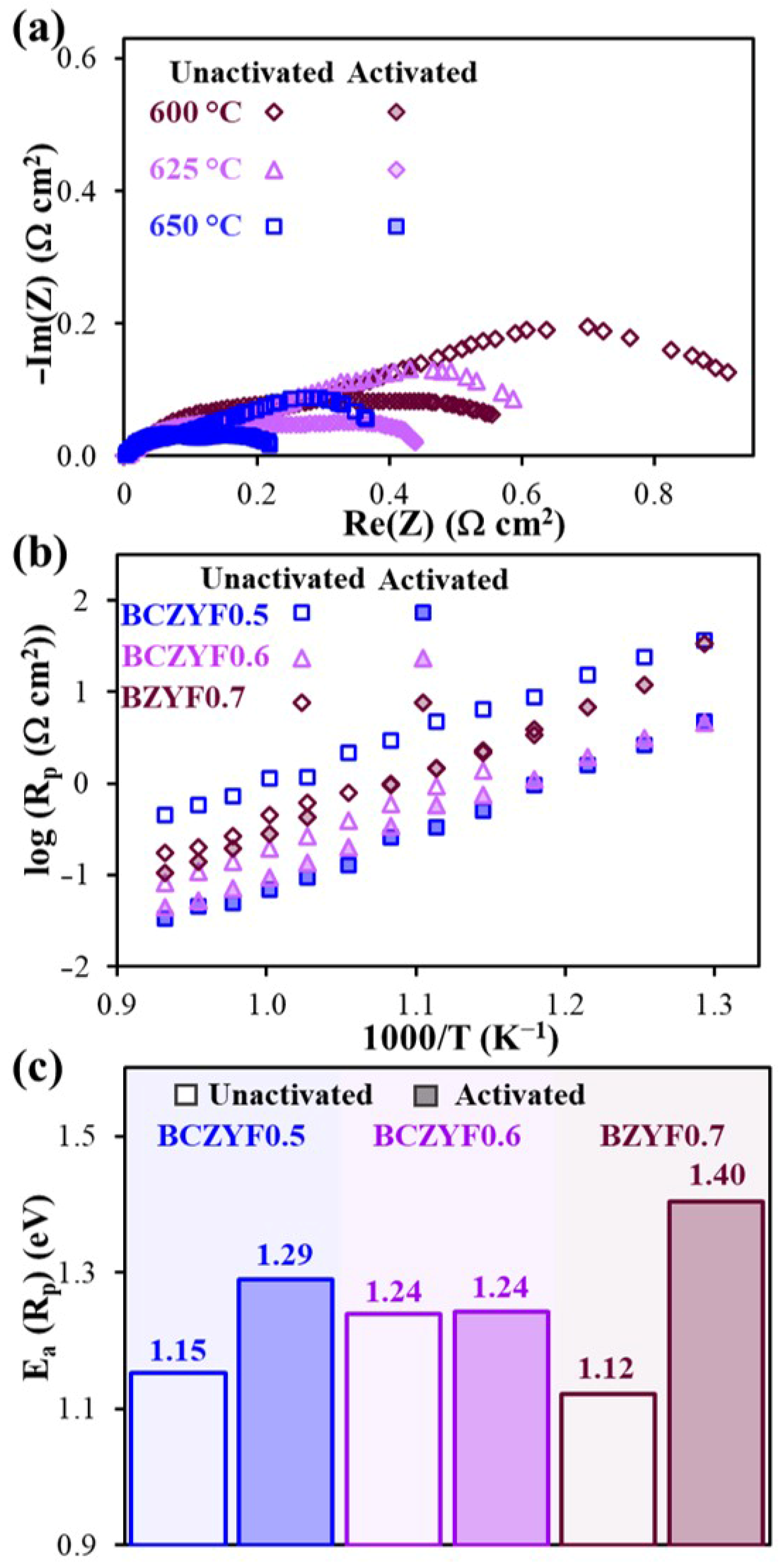

2.2.2. Polarization Characteristics

2.3. Characterization of a Protonic Ceramic Electrolysis Cell with BCZYF0.6-Based Cathode

2.3.1. Microstructural Analysis

2.3.2. Voltammetric Characteristics

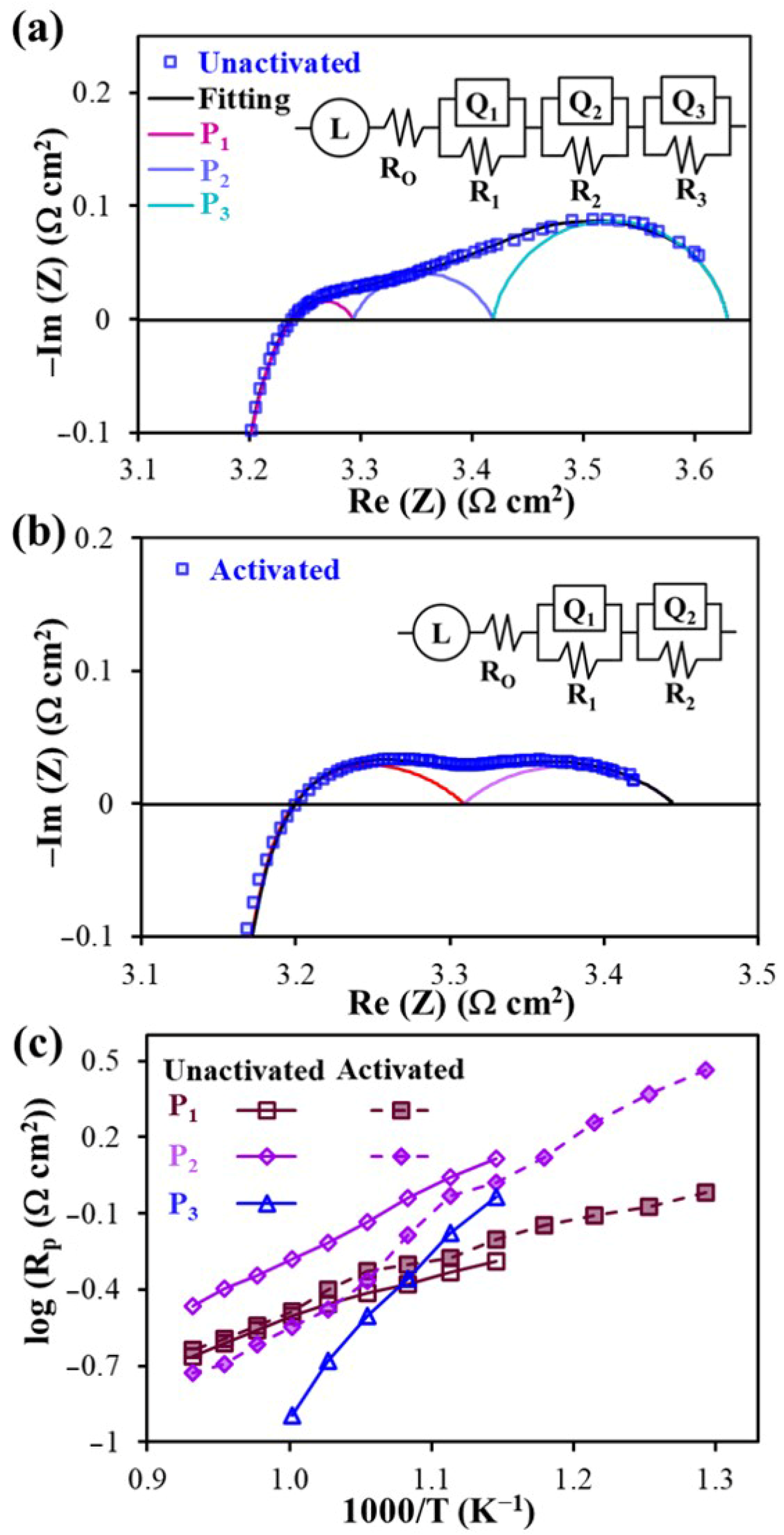

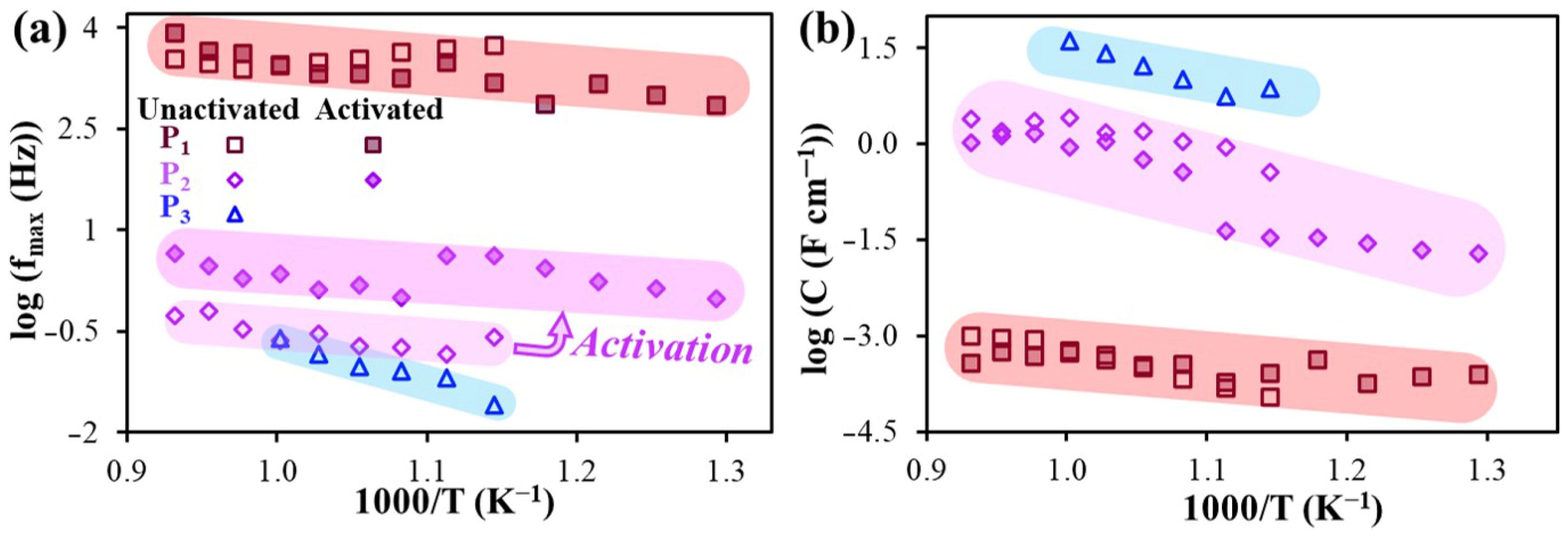

2.3.3. Polarization Characteristics of the Air Electrode

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Powders and Production of Ceramic Materials

3.2. Fabrication of the Electrochemical Cells

3.3. Characterization of Materials

3.4. Electrochemical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Kupecki, J.; Niemczyk, A.; Jagielski, S.; Kluczowski, R.; Kosiorek, M.; Machaj, K. Boosting solid oxide electrolyzer performance by fine tuning the microstructure of electrodes—Preliminary study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, T.-Z.; Salem, M.; Kamarol, M.; Das, H.S.; Nazari, M.A.; Prabaharan, N. A comprehensive study of renewable energy sources: Classifications, challenges and suggestions. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; He, Z.; Wu, W.; Zhao, P. Energy, exergy and ecology performance prediction of a novel SOFC-AMTEC-TEG power system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N.N.M.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Samat, A.A.; Osman, N.; Somalu, M.R. A review on cathode materials for conventional and proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 894, 162458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunyushkina, L.A. Solid oxide fuel cells with a thin film electrolyte: A review on manufacturing technologies and electrochemical characteristics. Electrochem. Mater. Technol. 2022, 1, 20221006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, M. A review on the preparation of thin-film YSZ electrolyte of SOFCs by magnetron sputtering technology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasta, G.; Bhakar, U.; Suthar, D.; Himanshu; Lamba, R.; Dhaka, M.S. Impact of ethyl cellulose variation on microstructural and electrochemical properties of spin coated YSZ electrolyte thin films for SOFCs: Slurry composition evolution. Ceram. Int. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, E.P.; Osinkin, D.A.; Bogdanovich, N.M. On a variation of the kinetics of hydrogen oxidation on Ni–BaCe(Y,Gd)O3 anode for proton ceramic fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 22638–22645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.; Qu, G.; Yang, W.; Gao, J.; Yousaf, M.; Mushtaq, N.; Wang, X.; Dong, W.; Wang, B.; Xia, C. Fast ionic conduction and rectification effect of NaCo0.5Fe0.5O2-CeO2 nanoscale heterostructure for LT-SOFC electrolyte application. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 924, 166565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Syafkeena, M.A.; Zainor, M.L.; Hassan, O.H.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Tseng, C.-J.; Osman, N. Review on the preparation of electrolyte thin films based on cerate-zirconate oxides for electrochemical analysis of anode-supported proton ceramic fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 918, 165434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojaver, P.; Chitsaz, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Khalilarya, S. Comprehensive comparison of SOFCs with proton-conducting electrolyte and oxygen ion-conducting electrolyte: Thermoeconomic analysis and multi-objective optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 205, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatnagar, M.K.; Vishnoi, M. Comparative study and analysis between Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC) and Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 2270–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasyanova, A.V.; Zvonareva, I.A.; Tarasova, N.A.; Bi, L.; Medvedev, D.A.; Shao, Z. Electrolyte materials for protonic ceramic electrochemical cells: Main limitations and potential solutions. Mater. Rep. Energy 2022, 100158, In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Ran, R.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Perovskite-based nanocomposites as high-performance air electrodes for protonic ceramic cells. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.L.R.M.; Samat, A.A.; Jais, A.A.; Somalu, M.R.; Muchtar, A.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Wan Isahak, W.N.R. Review on zirconate-cerate-based electrolytes for proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cell. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 6605–6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Lim, N. Performance and stability of proton conducting solid oxide fuel cells based on yttrium-doped barium cerate-zirconate thin-film electrolyte. J. Power Sources 2013, 229, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, F.J.A.; Nasani, N.; Reddy, G.S.; Munirathnam, N.R.; Fagg, D.P. A review on sintering technology of proton conducting BaCeO3-BaZrO3 perovskite oxide materials for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 438, 226991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Guan, R.; Wang, M.; He, T. Enhanced sintering and electrical properties of proton-conducting electrolytes through Cu doping in BaZr0.5Ce0.3Y0.2O3. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 11793–11804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Abdalla, A.M.; Jamain, S.N.B.; Zaini, J.H.; Azad, A.K. A review on proton conducting electrolytes for clean energy and intermediate temperature-solid oxide fuel cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.H. Recent progress in design and fabrication of SOFC cathodes for efficient catalytic oxygen reduction. Catal. Today 2022. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.S.; de Souza, T.M. Novel materials for solid oxide fuel cell technologies: A literature review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 26020–26036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.; Bogdanovich, N.; Kolchugin, A.; Ermakova, L.; Khrustov, A.; Farlenkov, A.; Bronin, D. Methods to increase electrochemical activity of lanthanum nickelate-ferrite electrodes for intermediate and low temperature SOFCs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 35923–35937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ding, J.; Xia, Y.; Miao, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W. Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8-xFe0.2NbxO3−δ (x ≤ 0.1) as cathode materials for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells with an electron-blocking interlayer. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 10215–10223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhuang, J.-W.; Lee, K.-R.; Lee, S.-W.; Wang, B.; Xia, C.; Hung, I.M.; Tseng, C.-J. A triple (e−/O2−/H+) conducting perovskite BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3−δ for low temperature solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 9767–9774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosato, R.; Cordaro, G.; Stucchi, D.; Cristiani, C.; Dotelli, G. Cobalt based layered perovskites as cathode material for intermediate temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: A brief review. J. Power Sources 2015, 298, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikalova, E.; Bogdanovich, N.; Kolchugin, A.; Shubin, K.; Ermakova, L.; Eremeev, N.; Farlenkov, A.; Khrustov, A.; Filonova, E.; Sadykov, V. Development of composite LaNi0.6Fe0.4O3−δ-based air electrodes for solid oxide fuel cells with a thin-film bilayer electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16947–16964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Guo, R.; Jing, X.; Li, P.; Yuan, J.; Wu, Y. Degradation mechanism and modeling study on reversible solid oxide cell in dual-mode—A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Chai, J. A free-cobalt barium ferrite cathode with improved resistance against CO2 and water vapor for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 13490–13501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Xu, X.; Teng, Y.; Lv, H.; Jin, Z.; Wang, D.; Peng, R.; Liu, W. A novel BaFe0.8Zn0.1Bi0.1O3−δ cathode for proton conducting solid oxide fuel cells. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 25453–25459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhashini, P.V.C.K.; Rajesh, K.V.D. Manufacturing method of BSCF cathode for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cell-A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 2357–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Lü, Z.; Jiang, S.P.; Shen, Y.; Su, W.; Chen, K. Ag decorated (Ba,Sr)(Co,Fe)O3 cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells prepared by electroless silver deposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Robson, M.J.; Seong, A.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Belotti, A.; Liu, J.; et al. Rational design of perovskite ferrites as high-performance proton-conducting fuel cell cathodes. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutina, L.R.; Lyagaeva, J.G.; Farlenkov, A.S.; Vylkov, A.I.; Vdovin, G.K.; Murashkina, A.A.; Demin, A.K.; Medvedev, D.A. Doped (Nd,Ba)FeO3 oxides as potential electrodes for symmetrically designed protonic ceramic electrochemical cells. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Lei, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Peng, S. Tuning oxygen vacancy of the Ba0.95La0.05FeO3−δ perovskite toward enhanced cathode activity for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35449–35457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Li, Z.; Zang, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, Z.; Zheng, Q. BaZr0.1Fe0.9−xNixO3−δ cubic perovskite oxides for protonic ceramic fuel cell cathodes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 9395–9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porotnikova, N.M.; Osinkin, D.A. Recent advances in heteroatom substitution Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6–δ oxide as a more promising electrode material for symmetrical solid-state electrochemical devices: A review. Electrochem. Mater. Technol. 2022, 1, 20221003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinkin, D.A. Precursor of Pr2NiO4+δ as a highly effective catalyst for the simultaneous promotion of oxygen reduction and hydrogen oxidation reactions in solid oxide electrochemical devices. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 24546–24554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onrubia-Calvo, J.A.; Pereda-Ayo, B.; Bermejo-López, A.; Caravaca, A.; Vernoux, P.; González-Velasco, J.R. Pd-doped or Pd impregnated 30% La0.7Sr0.3CoO3/Al2O3 catalysts for NOx storage and reduction. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 259, 118052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osinkin, D.A.; Beresnev, S.M.; Bogdanovich, N.M. Influence of Pr6O11 on oxygen electroreduction kinetics and electrochemical performance of Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6-δ based cathode. J. Power Sources 2018, 392, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, J. Study on Ce and Y co-doped BaFeO3−δ cubic perovskite as free-cobalt cathode for proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23868–23878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon Radii. Available online: http://abulafia.mt.ic.ac.uk/shannon/ptable.php (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Lyagaeva, J.; Medvedev, D.; Filonova, E.; Demin, A.; Tsiakaras, P. Textured BaCe0.5Zr0.3Ln0.2O3−δ (Ln=Yb, Y, Gd, Sm, Nd and La) ceramics obtained by the aid of solid-state reactive sintering method. Scr. Mater. 2015, 109, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ImageJ Wiki. Available online: https://imagej.net/ (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Tarutina, L.R.; Vdovin, G.K.; Lyagaeva, J.G.; Medvedev, D.A. BaCe0.7–xZr0.2Y0.1FexO3−δ derived from proton-conducting electrolytes: A way of designing chemically compatible cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 831, 154895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Wu, K.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, J. Low thermal expansion material Bi0.5Ba0.5FeO3−δ in application for proton-conducting ceramic fuel cells cathode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 21127–21135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Cai, L.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, M.; Yang, W. Structure and electrochemical properties of cobalt-free perovskite cathode materials for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 279, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Fan, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, M.; Sun, Z.; Ni, M. Zr doped BaFeO3−δ as a robust electrode for symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 32164–32169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, M.; Song, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Long, W.; Zhang, L. Cobalt–free perovskite cathode BaFe0.9Nb0.1O3 for intermediate–temperature solid oxide fuel cell. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 872, 159701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hou, N.; Gan, T.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. Enhanced oxygen reduction reaction activity of BaCe0.2Fe0.8O3−δ cathode for proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells via Pr-doping. J. Power Sources 2021, 495, 229776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.; Li, G.; Ren, R.; Xu, C.; Qiao, J.; Sun, W.; Sun, K.; Wang, Z. Pr-Doping Motivating the Phase Transformation of the BaFeO3−δ Perovskite as a High-Performance Solid Oxide Fuel Cell Cathode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S. Limitations of charge-transfer models for mixed-conducting oxygen electrodes. Solid State Ion. 2000, 135, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutin, A.P.; Vdovin, G.K.; Medvedev, D.A.; Yaremchenko, A.A. Fluorine-containing oxygen electrodes of the nickelate family for proton-conducting electrochemical cells. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 337, 135808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutin, A.P.; Lyagaeva, J.G.; Medvedev, D.A.; Bi, L.; Yaremchenko, A.A. Recent advances in layered Ln2 NiO4+δ nickelates: Fundamentals and prospects of their applications in protonic ceramic fuel and electrolysis cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 154–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cai, H.; Jin, F.; Sun, N.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Han, X.; Wang, S.; Su, X.; Long, W.; et al. Assessment of cobalt–free ferrite–based perovskite Ln0.5Sr0.5Fe0.9Mo0.1O3−δ (Ln = lanthanide) as cathodes for IT-SOFCs. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 2682–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belotti, A.; Wang, Y.; Curcio, A.; Liu, J.; Quattrocchi, E.; Pepe, S.; Ciucci, F. The influence of A-site deficiency on the electrochemical properties of (Ba0.95La0.05)1−xFeO3−δ as an intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cell cathode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Ma, Z.; Chen, H.; Ou, X.; Zhao, L.; Khan, M.; Ling, Y. Investigation of Fe-substituted in BaZr0.8Y0.2O3−δ proton conducting oxides as cathode materials for protonic ceramics fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 814, 152220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvonareva, I.; Fu, X.-Z.; Medvedev, D.; Shao, Z. Electrochemistry and energy conversion features of protonic ceramic cells with mixed ionic-electronic electrolytes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 439–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Qiu, R.; Lian, W.; Lei, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, F. Review: Measurement of partial electrical conductivities and transport numbers of mixed ionic-electronic conducting oxides. J. Power Sources 2022, 528, 231201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Tirumalarao, D.; Das, S.; Dixit, V.; Sruthy, S.P.; Vijayan, V.; Jaiswal-Nagar, D. Effect of pH variation on citrate nitrate sol-gels obtained from auto-combustion method: Synthesis, calculations and characterisations of extremely dense BaZrO3 ceramic. Open Ceram. 2022, 12, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZView® For Windows—Scribner Associates. Available online: http://www.scribner.com/software/68-general-electrochemistr376-zview-for-windows/ (accessed on 17 October 2022).

| Electrode Materials | Electrolyte Materials | Rp (Ω°cm2) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 °C | 700 °C | |||

| BaFe0.5Ce0.2Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ | BaCe0.5Zr0.3Y0.1Yb0.1O3−δ | 6.54 | 1.16 | This work |

| BaFe0.5Ce0.2Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ_Pr | 0.50 | 0.09 | ||

| BaFe0.6Ce0.1Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ | 1.40 | 0.27 | ||

| BaFe0.6Ce0.1Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ_Pr | 0.75 | 0.13 | ||

| BaFe0.7Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ | 2.20 | 0.62 | ||

| BaFe0.7Zr0.2Y0.1O3−δ_Pr | 2.32 | 0.43 | ||

| Bi0.5Ba0.5FeO3−δ | BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2O3−δ | 1.01 | 0.19 | [45] |

| BaCe0.05Fe0.95O3−δ | Sm0.2Ce0.8O1.9 | 0.19 | 0.05 | [46] |

| BaFe0.9Zr0.1O3−δ | La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O3−δ | 0.14 | 0.02 | [47] |

| BaFe0.9Nb0.1O3−δ | GDC | – | 0.10 | [48] |

| BaCe0.2Fe0.8O3−δ | BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.2O3−δ | 0.33 | 0.09 | [49] |

| BaCe0.2Fe0.7Pr0.1O3−δ | 0.25 | 0.07 | ||

| BaCe0.2Fe0.6Pr0.2O3−δ | 0.23 | 0.20 | ||

| BaCe0.2Fe0.5Pr0.3O3−δ | 0.51 | 0.14 | ||

| BaFe0.95Pr0.05O3−δ | Ce0.9Gd0.1O2−δ | 0.42 | 0.10 | [50] |

| BaFe0.9Pr0.1O3−δ | 0.68 | 0.14 | ||

| BaFe0.85Pr0.15O3−δ | 0.82 | 0.17 | ||

| BaFe0.8Pr0.2O3−δ | 1.68 | 0.32 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarutina, L.R.; Kasyanova, A.V.; Starostin, G.N.; Vdovin, G.K.; Medvedev, D.A. Electrochemical Activity of Original and Infiltrated Fe-Doped Ba(Ce,Zr,Y)O3-Based Electrodes to Be Used for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12111421

Tarutina LR, Kasyanova AV, Starostin GN, Vdovin GK, Medvedev DA. Electrochemical Activity of Original and Infiltrated Fe-Doped Ba(Ce,Zr,Y)O3-Based Electrodes to Be Used for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells. Catalysts. 2022; 12(11):1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12111421

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarutina, Liana R., Anna V. Kasyanova, George N. Starostin, Gennady K. Vdovin, and Dmitry A. Medvedev. 2022. "Electrochemical Activity of Original and Infiltrated Fe-Doped Ba(Ce,Zr,Y)O3-Based Electrodes to Be Used for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells" Catalysts 12, no. 11: 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12111421

APA StyleTarutina, L. R., Kasyanova, A. V., Starostin, G. N., Vdovin, G. K., & Medvedev, D. A. (2022). Electrochemical Activity of Original and Infiltrated Fe-Doped Ba(Ce,Zr,Y)O3-Based Electrodes to Be Used for Protonic Ceramic Fuel Cells. Catalysts, 12(11), 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal12111421