1. Introduction

The energy crisis is becoming one of the biggest issues faced by society, directly impacting human life currently and in the near future. Fuel cell technology has great potential as a future power source for a wide variety of energy applications including electric vehicles and mobile electronics [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Among the different types of fuel cells, direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) are possible alternative power sources for portable electronic devices, mobile drones, and robots [

7,

8,

9]. It is well known that a methanol electro-oxidation occurs in the anode and that an oxygen reaction occurs in the cathode in DMFC systems as follows [

10]:

It is well known that the performance of an electrode catalyst is highly affected by the active metals and support materials used [

5,

6,

11,

12,

13,

14]. For Pt-based active metals, Pt or bimetallic Pt-M nanoparticles should be highly dispersed on support materials without any aggregation in order to utilize their large active surface [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In addition, because the characteristics of the support materials can have a significant influence on both the activity and stability of the supported Pt catalysts under harsh electrochemical reaction conditions, it is necessary that the support materials have advantageous properties such as high electrical conductivity, inertness under harsh conditions, and favorable morphology for the efficient diffusion of reactants and products [

21,

22].

In the past decades, extensive studies have been conducted on carbon-supported Pt catalysts for anodic methanol electro-oxidation [

23,

24,

25]. Conventional carbon materials (e.g., carbon black Vulcan XC-72) are generally used as supports in electrochemistry, and the resulting Pt/C catalysts exhibit excellent performance for anodic methanol electro-oxidation under ambient temperature conditions [

26,

27]. Although conventional carbons have beneficial features for fabricating Pt/C catalysts that can be used in practical fuel cell systems, several obstacles remain to be overcome, such as resistance to CO poisoning, stability related to carbon corrosion during long-term operation, and limited conductivity for facile electron transfer [

6,

24,

28]. Thus, it is still challenging to find and apply support materials for Pt-based electrocatalysts that have excellent characteristics such as high mechanical stability and outstanding electrical conductivity.

Titanium nitride (TiN) is an extremely hard ceramic material. Because TiN has an intrinsically low friction coefficient, it is often applied as a coating for alloys, steel, carbide, and other materials in order to improve their surface properties. It is also thermally stable and inert in most chemical environments. In addition, it has an extra electron that is not involved in the formation of covalent bonds between Ti and N, which has a significant effect on the conductive characteristics of TiN. Owing to its outstanding characteristics (namely, chemical and thermal stability with high electronic conductivity) TiN has been extensively investigated as an electrode material for supercapacitor or fuel cell applications [

29,

30]. It is well known that Pt-supported TiN catalysts show not only enhanced CO tolerance but also remarkable stability to electrochemical corrosion during long-term operation for both the anodic methanol oxidation reaction and cathodic oxygen reduction reaction [

6,

24,

28,

31]. It has also been reported that TiN-supported Pt catalysts exhibit excellent support stability and that unique interactions between Pt and the TiN support occur, resulting in enhanced catalytic activity for methanol electro-oxidation [

32]. Although there have been extensive investigations related to the synthesis and application of TiN as a support material, there are limited studies related to the use of nanostructured TiN materials for catalytic applications. Since TiN nanostructures can provide more opportunities to enhance catalytic activity in various applications, it is still desirable to investigate various nanostructured TiN materials.

It is well known that hollow nanostructures exhibit beneficial characteristics in catalytic reactions and are considered efficient catalyst models that can enhance catalytic performance by improving reaction kinetics [

33,

34,

35]. Hollow nanostructures with a porous shell layer possess a large surface area per unit mass. The nanoscale shell layer not only provides a short diffusion pathway but also allows reactant molecules to easily access the active site. In addition, once the overall dimension of the hollow nanostructure is in the submicron range, the hollow particles can be easily dispersed in liquid solvent, minimizing the diffusion resistance between the reactant molecules and the surface. These favorable diffusion and dispersion characteristics are beneficial for heterogeneous catalysis. In addition, hollow shell layers with nanoscale dimensions can be easily functionalized. In particular, both the inner and outer surfaces can be selectively functionalized with different active sites, resulting in the ability to induce either confined catalysis or cascade reactions. Hollow TiO

2 nanostructures have been successfully applied as photocatalysts for photocatalytic organic decomposition and hydrogen production [

36,

37]. Moon et al. also synthesized hollow TiN nanostructures and demonstrated a superior performance in supercapacitor applications compared to a solid TiN counterpart [

38]. Based on previous studies and our hypothesis, it is believed that hollow TiN materials with excellent conductivity will be good candidates for conductive scaffolds in electrocatalytic reactions.

In this work, we synthesize a hollow TiN nanostructure that is used as a support material of a Pt-supported catalyst for methanol electro-oxidation. The hollow TiN nanostructure was synthesized by preparing a hollow anatase TiO2 nanostructure, followed by conversion to a hollow TiN counterpart by ammonia nitridation at different temperatures. As the nitridation temperature increased, the TiN crystallinity of the resulting hollow samples continuously increased. The prepared hollow TiN samples exhibited advantageous characteristics, such as uniform particle dimensions, finely controlled crystallinity, and enhanced electrochemical conductivity. When the Pt nanoparticles were deposited on TiN-800 (prepared by ammonia nitridation at 800 °C), the resulting Pt/H-TiN-800 sample exhibited excellent electrochemical performance for methanol electro-oxidation. In this paper, we discuss the physicochemical characteristics and electrochemical performance of hollow TiN samples and their corresponding Pt catalysts.

2. Results and Discussion

Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the procedure for preparing hollow TiN nanostructure samples and Pt/hollow TiN catalysts, as well as corresponding TEM images for each step. To synthesize the hollow TiN nanostructure, pre-synthesized hollow anatase TiO

2 was charged on nitridation using ammonia flow. Hollow anatase TiO

2 was synthesized by a template-assisted sol–gel method, followed by sequential chemical treatments and calcination [

36]. Uniform silica particles were synthesized using the well-known Stober method [

39]. The monodisperse silica particles were approximately 180 nm in size (

Figure 1b). The silica was charged to the TiO

2 coating and the SiO

2@TiO

2 core-shell nanostructure was successfully synthesized by the sol–gel coating of the TiO

2 precursor (Titanium (IV) n-butoxide), as shown in

Figure 1c. NaOH treatment was performed to form a hollow nanostructure. Because the dissolution rate of silica is much faster than that of TiO

2 in an aqueous NaOH solution, the silica core was preferentially dissolved, resulting in a hollow TiO

2 nanostructure. As shown in

Figure 1d, well-defined hollow TiO

2 spheres were formed after NaOH etching. Because NaOH-treated hollow TiO

2 has many Na

+ ions in its shell matrix, they can be exchanged with H

+ ions by simple acid treatment, as previously reported [

36]. A simple acid treatment of the NaOH-etched TiO

2 with a diluted HCl solution was found to convert sodium titanate into protonated titanate, helping not only to preserve the pure titania phase but also to allow for precise control of the TiO

2 crystallinity [

36,

37]. Thus, hollow anatase TiO

2 can be easily obtained by calcining acid-treated hollow TiO

2 at 800 °C. To synthesize hollow TiN, the hollow anatase TiO

2 was heat-treated under an ammonia environment at different temperatures. Although hollow anatase TiO

2 was treated under ammonia conditions, the structural integrity of the resulting hollow TiN was well maintained, as shown in

Figure 1e. After the deposition of colloidal Pt nanoparticles on the surface of the hollow TiN sample, it could be used as an electrocatalyst for methanol electro-oxidation.

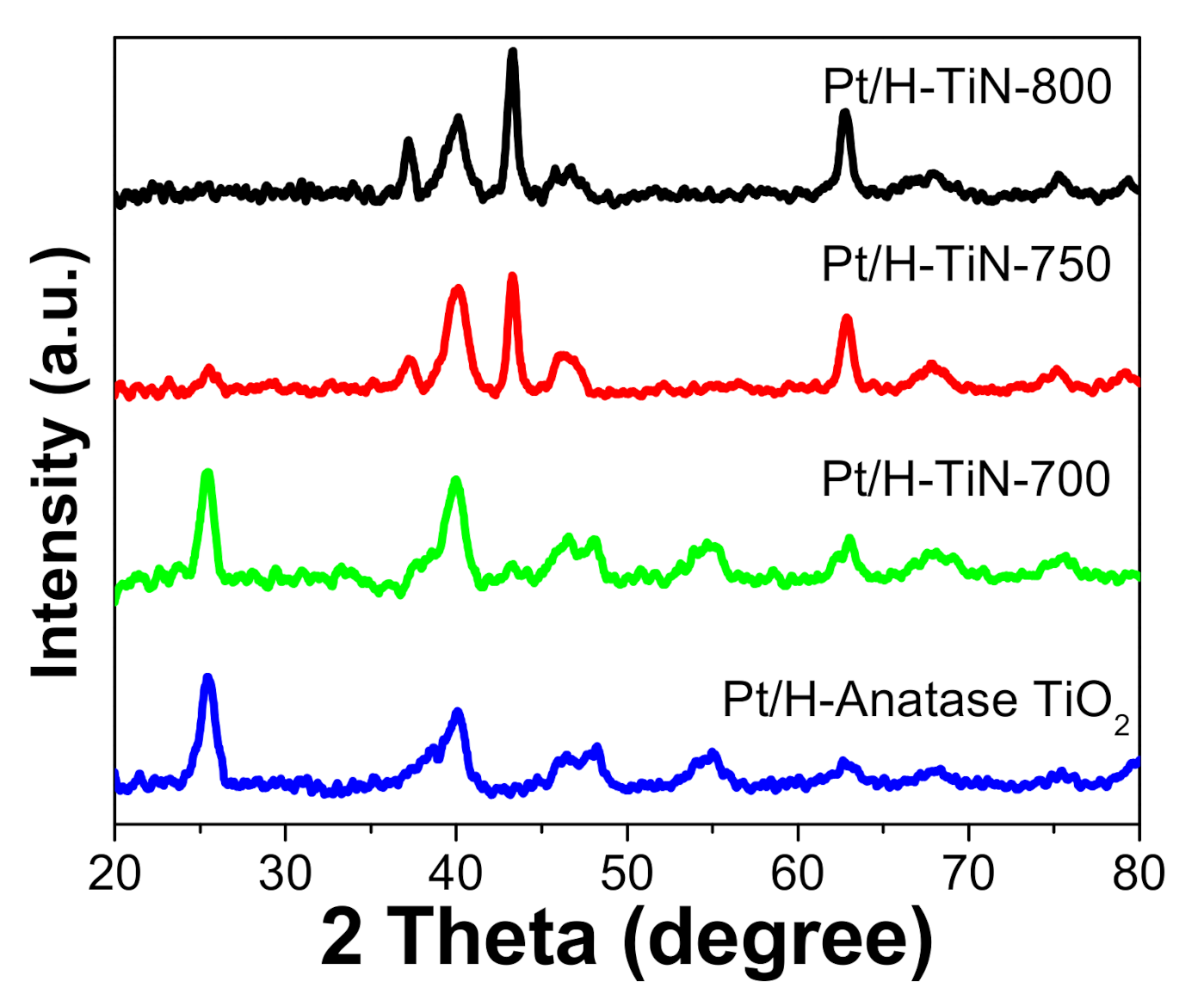

The crystalline characteristics of the pre-synthesized hollow TiO

2 and hollow TiN samples were investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in

Figure 2, the NaOH-etched H-TiO

2 exhibited amorphous characteristics. It is well known that TiO

2 materials synthesized by sol–gel reactions generally exhibit amorphous characteristics [

36,

40]. After HCl treatment followed by calcination at 800 °C, the hollow anatase TiO

2 sample (H-anatase TiO

2) showed typical diffraction peaks of the anatase phase at 2

θ = 25.4°, 37.8°, 48.1°, 54.0°, 55.1°, and 62.7° that were attributed to the (101), (004), (200), (105), (211), and (204) planes, respectively. When ammonia treatment was carried out at a high temperature, new diffraction peaks appeared. When ammonia nitridation was carried out at 700 °C (H-TIN-700), the sample exhibited mainly anatase diffraction peaks with minor peaks at 2

θ = 36.8°, 42.6°, 61.9°, and 74° related to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) planes of TiN, respectively. As the ammonia nitridation temperature increased, the peaks related to the TiN phase intensified and the peaks related to anatase decreased significantly. The XRD pattern of H-TIN-750 comprised a major TiN phase with a minor anatase phase. When an even higher temperature was used during nitridation (800 °C: H-TiN-800), the sample showed sharp peaks related to pure TiN. This indicates that all the anatase crystals were converted to pure TiN by ammonia nitridation at high temperatures. Although there is a chance for the anatase phase to be converted to the rutile phase during ammonia nitridation (as reported by Moon et al.), phase transformation from anatase TiO

2 to the TiN phase mainly occurred in our work. It seems that the phase transformation from anatase TiO

2 to TiN preferentially occurs rather than that from anatase TiO

2 to its rutile counterpart in this work [

38]. The average crystalline sizes of the samples were calculated using the Scherrer formula. The average anatase grain sizes were estimated to be approximately 10.7, 9.8, 7.7, and 0 nm for H-anatase TiO

2, H-TiN-700, H-TiN-750, and H-TiN-800, respectively. The TiN grain size exhibited a different trend. The average TiN crystalline sizes were estimated to be approximately 0, 14.2, 15.7 and 16.7 nm for H-anatase TiO

2, H-TiN-700, H-TiN-750, and H-TiN-800, respectively. This indicates that anatase TiO

2 was continuously converted to the TiN phase as the nitridation temperature increased.

We also investigated the textural properties of hollow anatase TiO

2 and hollow TiN samples. As shown in

Figure 3, both H-anatase TiO

2 and H-TiN samples exhibited a well-developed hysteresis loop in the range of P/P

0 = 0.4–0.8. This indicates that both samples had well-developed mesoporous structures. As previously reported, mesoporous characteristics should originate from inter-grain mesopores resulting from the crystallization of the amorphous TiO

2 shell to the formation of crystallized grains during calcination [

40,

41]. Both H-anatase TiO

2 and H-TiN samples showed similar N

2 adsorption values at low relative pressures (P/P

0 = 0–0.2), indicating a similar surface area. The calculated values of the BET surface area for H-anatase TiO

2, H-TiN-700, H-TiN-750, and H-TiN-800 were 66, 64, 70, and 71 m

2/g, respectively. The H-anatase TiO

2 sample exhibited distinct distribution peaks within the mesopore range (1–15 nm) in the BJH pore size distribution, indicating the existence of mesoporosity in the TiO

2 shell layer. After ammonia nitridation, although the TiN samples showed slightly shifted distribution peaks in the mesopore range (1–20 nm), they also exhibited similar mesopores. Based on the N

2 adsorption results, it can be concluded that the textural properties of the samples were not significantly changed through ammonia nitridation.

After the deposition of colloidal Pt nanoparticles on either H-anatase TiO

2 or H-TiN supports, the crystalline properties of the Pt-deposited catalysts were also investigated. As shown in

Figure 4, Pt/H-anatase TiO

2 showed diffraction peaks related to its anatase phase, which are identical to the peaks observed in the H-anatase TiO

2 support in

Figure 2. In addition, distinct peaks related to fcc Pt were observed at 2

θ = 39.7°, 46.2° and 67.4°, attributed to the Pt (111), Pt (200), and Pt (220) planes, respectively. Pt/TiN-700 also exhibited identical diffraction peaks for both anatase TiO

2 and TiN, compared with the mother TiN support and it had distinct peaks related to Pt nanoparticles. The Pt/TiN-750 and Pt/TiN-800 samples also exhibited similar trends. The average crystallite size of the supported Pt particles was estimated using the Scherrer equation based on the Pt (220) diffraction peaks since the Pt (220) peak was isolated from the other peaks [

5]. The estimated Pt particle sizes in Pt/H-anatase TiO

2, Pt/H-TiN-700, Pt/H-TiN-750, and Pt/H-TiN-800 were 2.7, 2.7, 2.8, and 2.7 nm, respectively. In addition, the surface areas of Pt were calculated from the crystallite size obtained by the Scherrer equation using the following equation:

where d is the average crystallite size (nm), ρ is the density of Pt (21.4 g/cm

3), and S is the surface area of Pt crystallite (m

2/g

Pt). The surface areas of Pt crystallite on Pt/H-anatase TiO

2, Pt/H-TiN-700, Pt/H-TiN-750, and Pt/H-TiN-800 were estimated to be 103, 103, 100, and 103 m

2/g

Pt, respectively. Based on the XRD results, we can conclude that the chemical characteristics of the support materials were well maintained even after colloidal Pt deposition. In addition, all the catalysts showed comparable Pt dispersions with similar particle sizes.

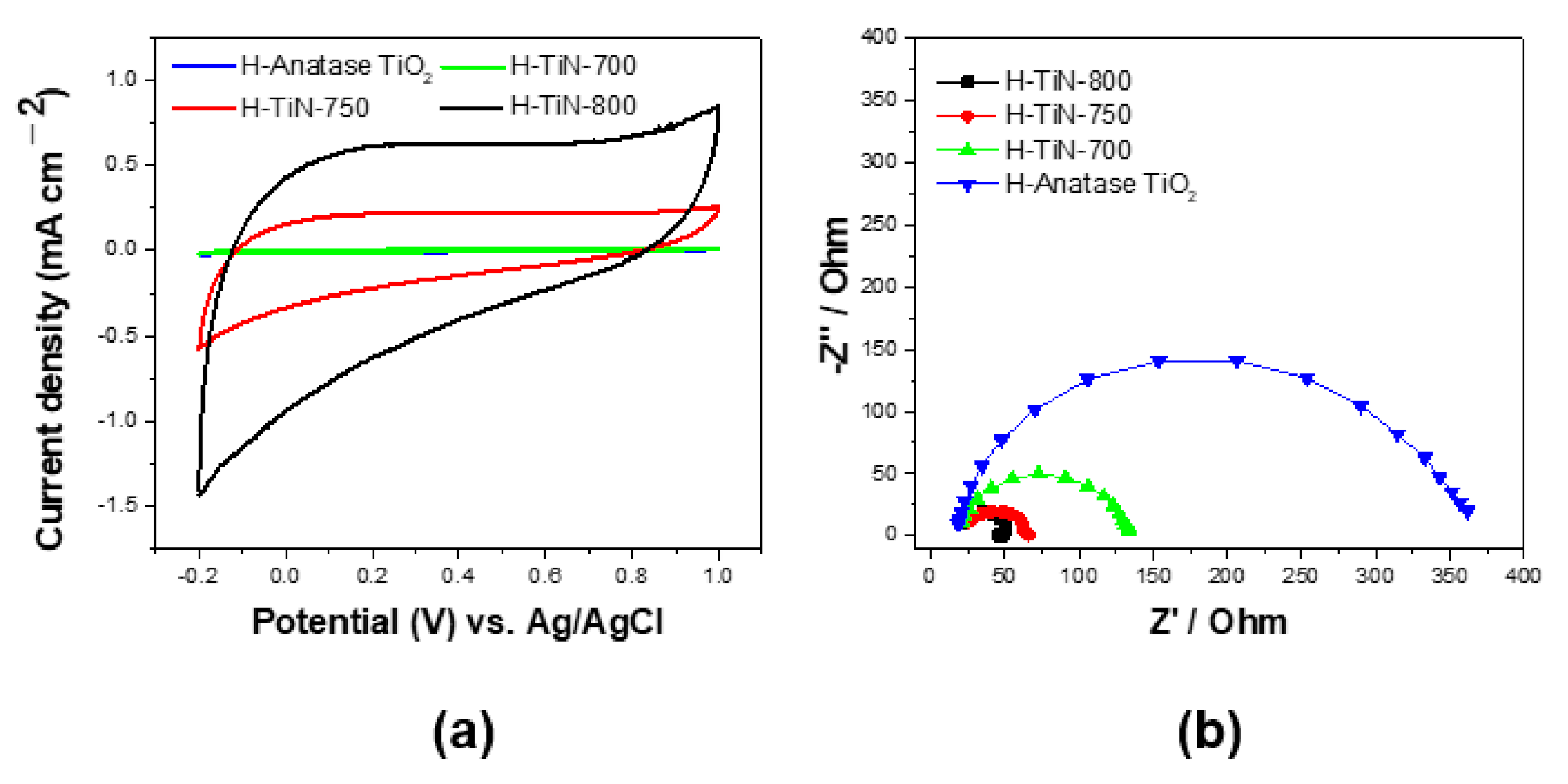

To investigate the electrochemical characteristics of both the hollow anatase TiO

2 and H-TiN samples, electrochemical measurements were conducted.

Figure 5 shows the cyclic voltammograms (CVs) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots of H-anatase TiO

2, H-TiN-700, H-TiN-750, and H-TiN-800. As shown in

Figure 5a, all samples display quasi-rectangular CV patterns without any obvious oxidation/reduction peaks. This indicates that all samples exhibit electric double-layer capacitance in this potential region. The H-TiN-800 sample exhibited the best capacitive properties among the samples. The relative order of the capacitance was as follows: H-anatase TiO

2 ≤ H-TiN-700 < H-TiN-750 < H-TiN-800. It should be noted that the electrochemical characteristics of the TiN samples were significantly enhanced as the TiN crystallinity increased. Continuous CV experiments were also carried out using H-TiN-800 and H-anatase TiO

2 in order to evaluate the stability of the support materials. The CV results of H-TiN-800 exhibited negligible variation between the first and hundredth cycles, even though there was a minor change in the anodic scan in the potential range of −0.1–0.8 V (

Figure S1, Supporting information). This indicates that the H-TiN-800 sample was sufficiently stable under the harsh electrochemical conditions.

The electrochemical properties were further confirmed using the EIS results, as shown in

Figure 5b. The EIS Nyquist plots of all samples exhibited typical semi-circular shapes. It is generally accepted that an EIS Nyquist plot with a small radius indicates a low resistance and good conductance. The smaller arc indicates low charge transfer impedance at the electrode-electrolyte interface. Of the four samples employed as catalyst supports in this work, H-TiN-800 exhibited the smallest arc radius, suggesting that it has the best conductive characteristics. As shown in

Figure 4, H-TiN-800 has the highest TiN crystallinity and must have the most conductive TiN framework. Thus, it has the smallest arc among the samples employed. The relative arc size is in the order: H-anatase TiO

2 > H-TiN-700 > H-TiN-750 >H-TiN-800. It indicates that the relative conductivity increases in the order: H-anatase TiO

2 < H-TiN-700 < H-TiN-750 < H-TiN-800. This trend was consistent with the CV measurements. The improved electrochemical performance can be attributed to the intrinsic electronic properties of the TiN samples, such as their low electronic resistance. It is well known that TiN can offer an electronically conducting framework and allow fast charge transfer, inducing rapid electrochemical redox reactions. Furthermore, the TiN structure displayed better capacitance than its TiO

2 counterpart [

38]. In this work, we synthesized hollow anatase TiO

2 and converted it to hollow TiN by ammonia nitridation at different temperatures. As the nitridation temperature increased, the TiN crystallinity of the resulting H-TiN sample was enhanced. Thus, the electrochemical properties of the resulting TiN samples can be significantly improved, which is desirable in electrochemical devices.

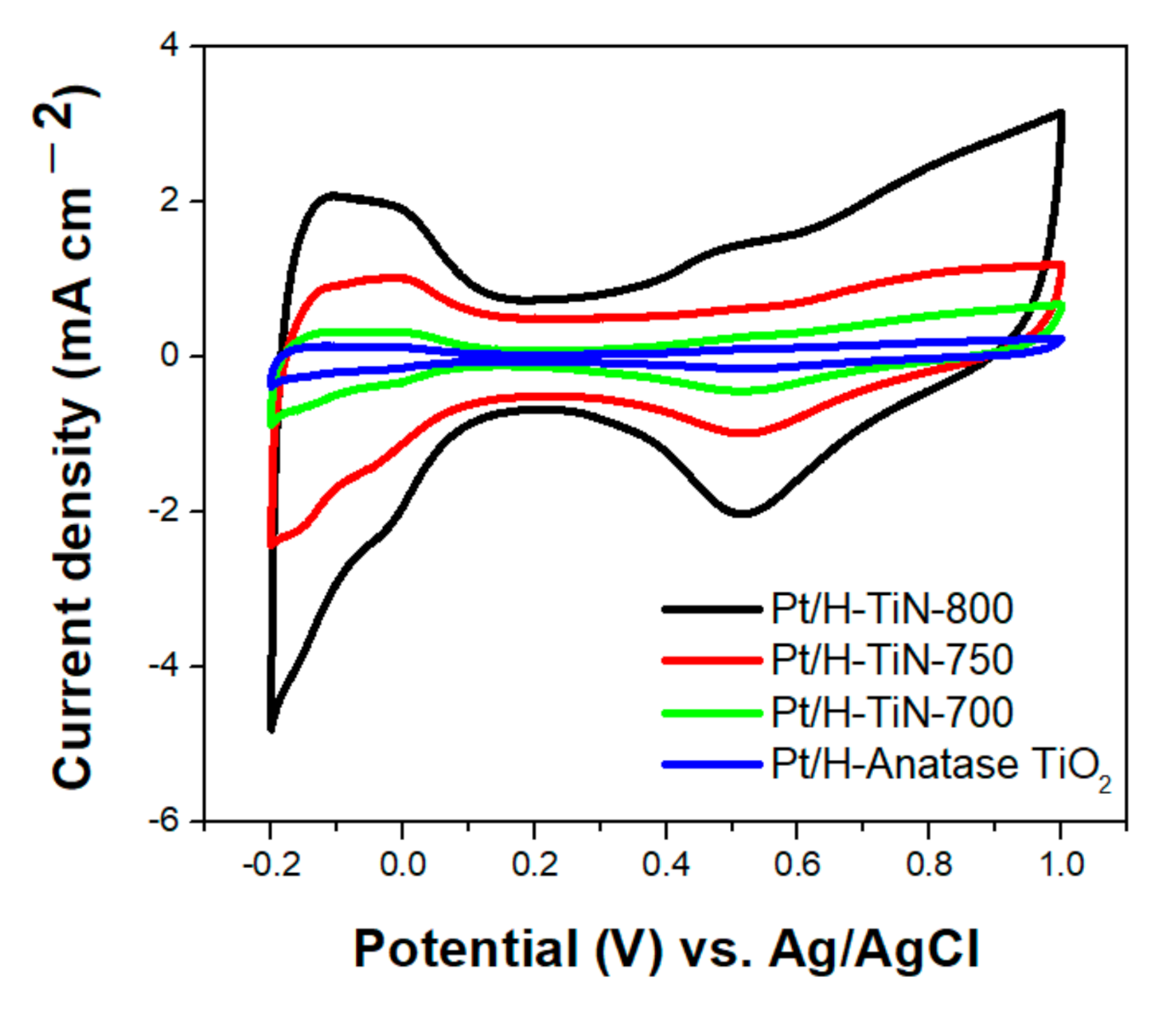

The electrochemical active surface area (ECAS) and electrochemical characteristics of both the Pt/H-anatase-TiO

2 and Pt/H-TiN catalysts were investigated.

Figure 6 shows the CV curves of the prepared Pt catalysts in an acidic electrolyte (0.5 M H

2SO

4), which were used to estimate the ECAS using the Coulombic charge for H

+ ion adsorption–desorption. The CV curves of the Pt/H-TiN catalysts showed a typical H

+ ion adsorption/desorption region, a double-layer charging region, a Pt pre-oxidation region, and a Pt reduction region. The peak area for the H

+ ion desorption current was used to estimate the ECAS values, which were calculated from the integrated charge after correction for the contribution of the double-layer charging current using the following equation:

where

SECSA, QH, and

WPt are the ECSA value (m

2/g

Pt), total charge for H

+ ion desorption (μC), and Pt loading on the electrode (mg/cm

2), respectively. The value 210 is the charge density (μC/cm

2Pt) required to oxidize a monolayer of H

+ ions on the clean Pt surface. The ECSA values for Pt/H-anatase TiO

2, Pt/H-TiN-700, Pt/H-TiN-750, and Pt/H-TiN-800 were 6.7, 16.7, 29.7, and 82.6 m

2/g

Pt, respectively.

Similar to the CV results for the support materials, the CV current densities and ECAS values of the corresponding Pt catalysts were improved as the TiN crystallinity was enhanced with increasing nitridation temperature. As shown in

Figure 6, the Pt/H-TiN-800 sample showed the largest H

+ ion adsorption–desorption region, resulting in the largest ECAS value. As confirmed by the BET and XRD results (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), both surface area values obtained for each support material were similar, and the Pt crystallite sizes of all supported Pt catalysts were similar. This indicates that the Pt dispersion should be almost identical physically since the same amount of Pt is loaded on each support material having a similar surface area by an identical synthetic method. Thus, variations in the CV results of the supported Pt catalysts should be highly influenced by the characteristics of the support materials. As the TiN crystallinity increased, the electrochemical performance of the corresponding Pt catalysts was significantly enhanced, owing to the advantageous characteristics of the TiN support such as low resistance and high electrical conductivity. Thus, the H-TiN-800 support with the pure TiN phase and highest crystallinity should be the most conductive, resulting in the corresponding Pt/H-TiN-800 exhibiting the most distinct H

+ ion adsorption/desorption current and the most enhanced electrochemical characteristics.

To evaluate the electrocatalytic activity of the prepared Pt catalysts, CV was performed in a H

2SO

4 solution in the presence of a methanol solution.

Figure 7 shows the CVs of the prepared Pt catalysts in a 0.5 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte containing 2 M CH

3OH. The methanol electro-oxidation current changed negligibly between −0.2 and 0.2 V. The current dramatically increased after 0.2 V, and the maximum peak current was observed at approximately 0.68–0.7 V. After 0.7 V, the current decreased since the number of Pt active sites was reduced owing to the formation of the Pt oxide surface. Above 0.85 V, the current increased again, indicating that methanol oxidation proceeded on the Pt-oxide surface. In the cathodic cycle, the active sites were recovered, resulting in the appearance of a methanol oxidation current peak. We evaluated the catalytic activity of the prepared Pt catalysts by comparing the maximum peak currents during the anodic scan. The relative maximum peak current density was in the order: Pt/H-anatase TiO

2 < Pt/H-TiN-700 < Pt/H-TiN-750 < Pt/H-TiN-800. It should be noted that Pt/H-TiN-800 had the highest current density among the Pt catalysts employed in this study. This indicates that Pt/H-TiN-800 had the highest catalytic activity for methanol electro-oxidation.

It is well known that electrocatalytic activity is significantly influenced by the intrinsic characteristics of either the supported Pt catalysts or support materials [

5,

6,

24,

28,

31]. Because Pt catalysts supported on different support (containing an identical amount of Pt loaded on the support and with a similar metal dispersion) were used on the working electrode, it can be concluded that the variation in catalytic activity can be explained by the different intrinsic characteristics of the support materials used. As previously mentioned, the higher the TiN crystallinity, the more electrically conductive the support will be [

6,

28,

31,

38]. The H-TiN-800 sample exhibited a high crystallinity of the pure TiN structure. This not only facilitated electron transfer but also reduced electrical resistance during electrochemical reactions. Thus, the Pt/H-TiN-800 catalysts can undergo active electrochemical reactions without severe resistance to electron transfer. However, because of the larger electron transfer resistance of Pt/H-anatase TiO

2, due to the semiconducting characteristics of the TiO

2 support, it is believed that slow electron transfer determines the overall reaction rate.

To investigate how ammonia nitridation at higher temperatures influences the characteristics of the TiN support and the corresponding Pt catalysts, we also prepared hollow TiN nanostructures by ammonia nitridation at 900 °C (H-TiN-900) and synthesized the corresponding Pt catalyst (Pt/H-TiN-900). As shown in

Figure S2, H-TiN-900 exhibited a smaller surface area value (35 m

2/g) as well as poorer CV results. This indicates that ammonia nitridation at 900 °C induces a decrease in surface area due to the excessive growth of TiN crystallites, even though it might improve the electrical conductivity. The smaller surface area of H-TiN-900 can induce a lower Pt dispersion in the resulting Pt/H-TiN-900 catalyst. As a result, Pt/H-TiN-900 has a smaller ECAS value (40 m

2/g

Pt), resulting in poorer performance than the Pt/H-TiN-800 catalysts. Because ammonia nitridation at 800 °C produces an electrically conductive TiN phase with a large surface, it can be concluded that 800 °C is the optimal temperature.

In addition, the electron that is not involved in the formation of covalent bonds creates electron-abundant environments in TiN. This can be transferred to the supported Pt nanoparticles and cause Pt to exist in a more reduced state. As shown in

Figure 8, the Pt 4f XPS peaks of Pt/H-TiN-800 showed more negative values of binding energy (70.98 and 74.21 eV for Pt 4f

7/2 and Pt 4f

5/2, respectively) than those of Pt/H-anatase TiO

2 (71.11 and 74.34 eV for Pt 4f

7/2 and Pt 4f

5/2, respectively). This indicates that Pt/H-TiN-800 has a more active metallic Pt surface than Pt/H-anatase TiO

2. Because methanol electro-oxidation occurs easily on the surface of metallic Pt, Pt/H-TiN-800 exhibits outstanding activity.