The Potassium-Induced Decomposition Pathway of HCOOH on Rh(111)

Abstract

1. Introduction

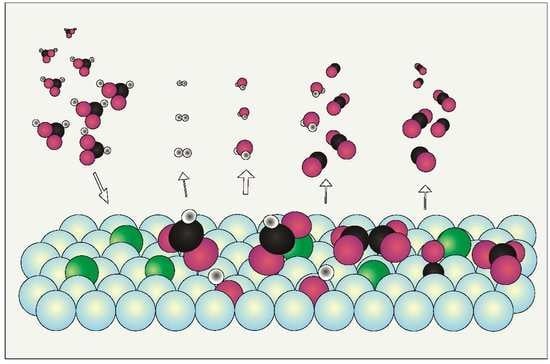

2. Results

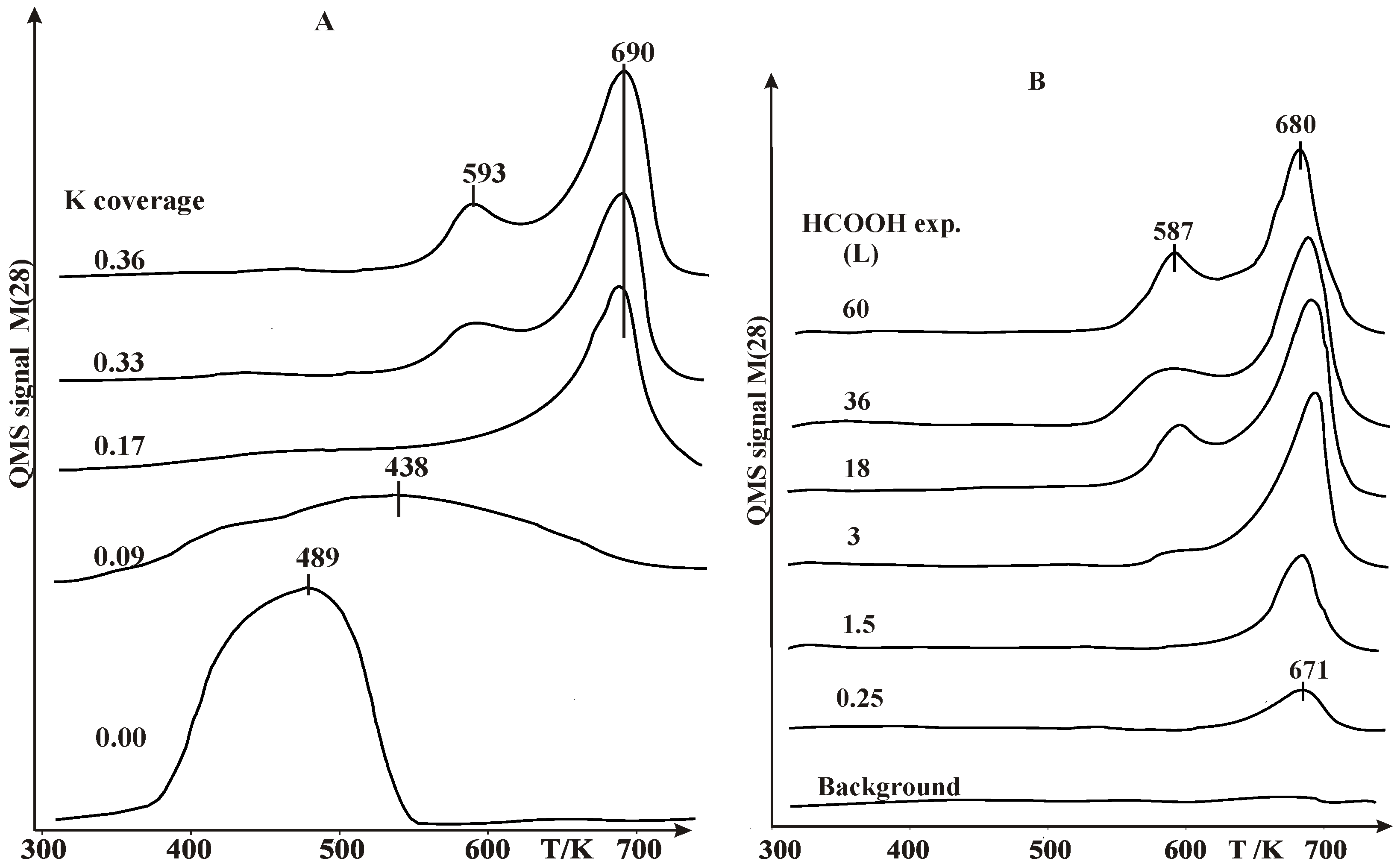

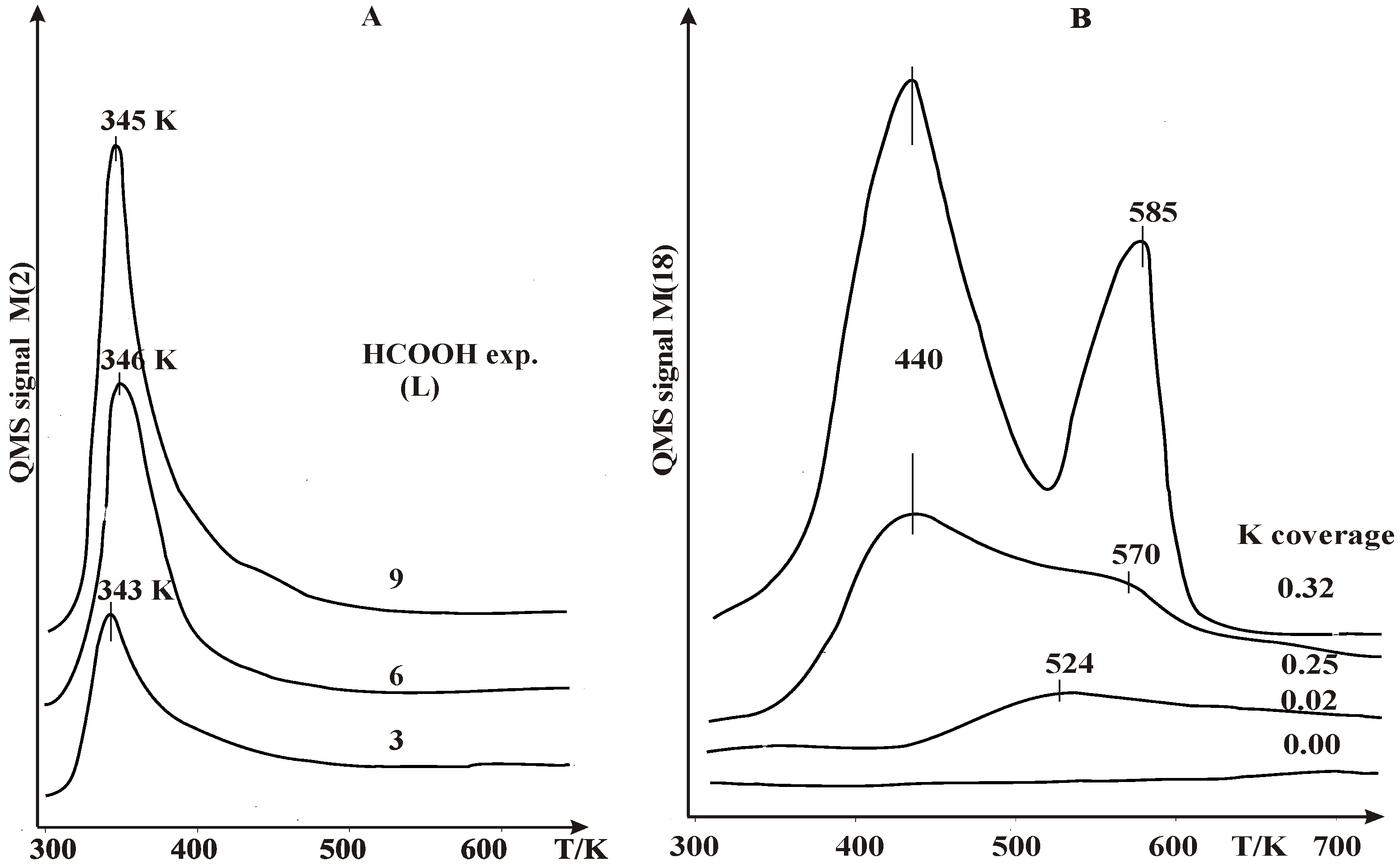

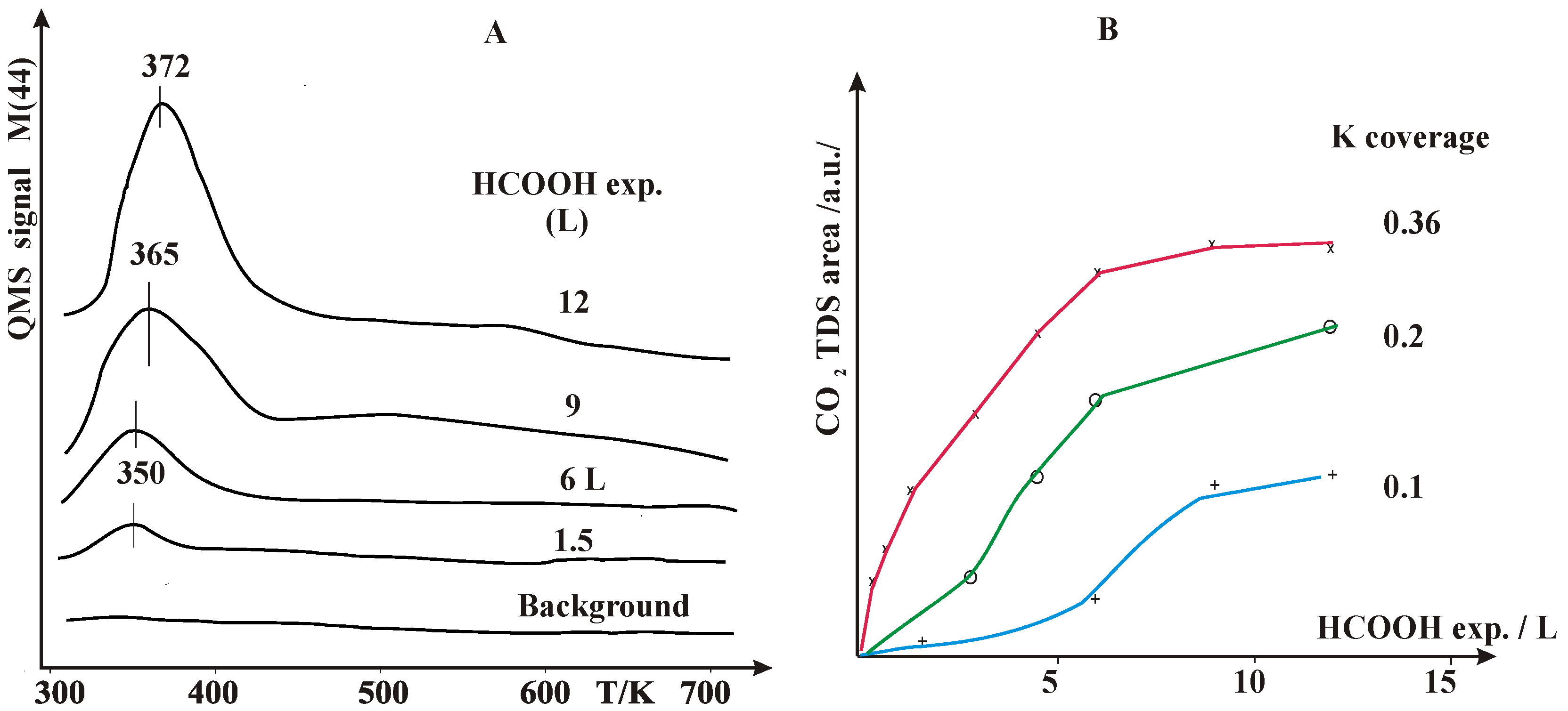

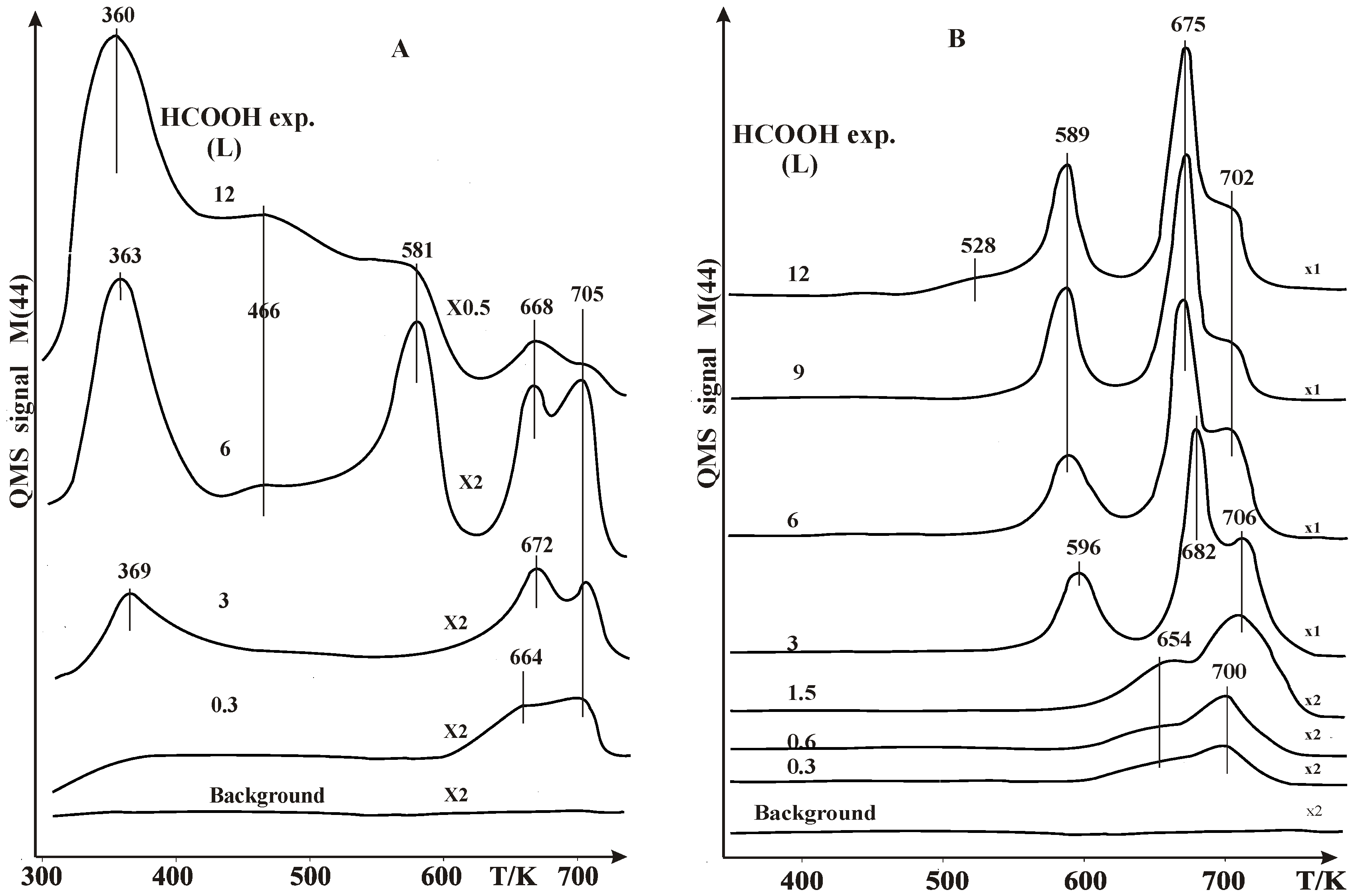

2.1. Thermal Desorption Measurements

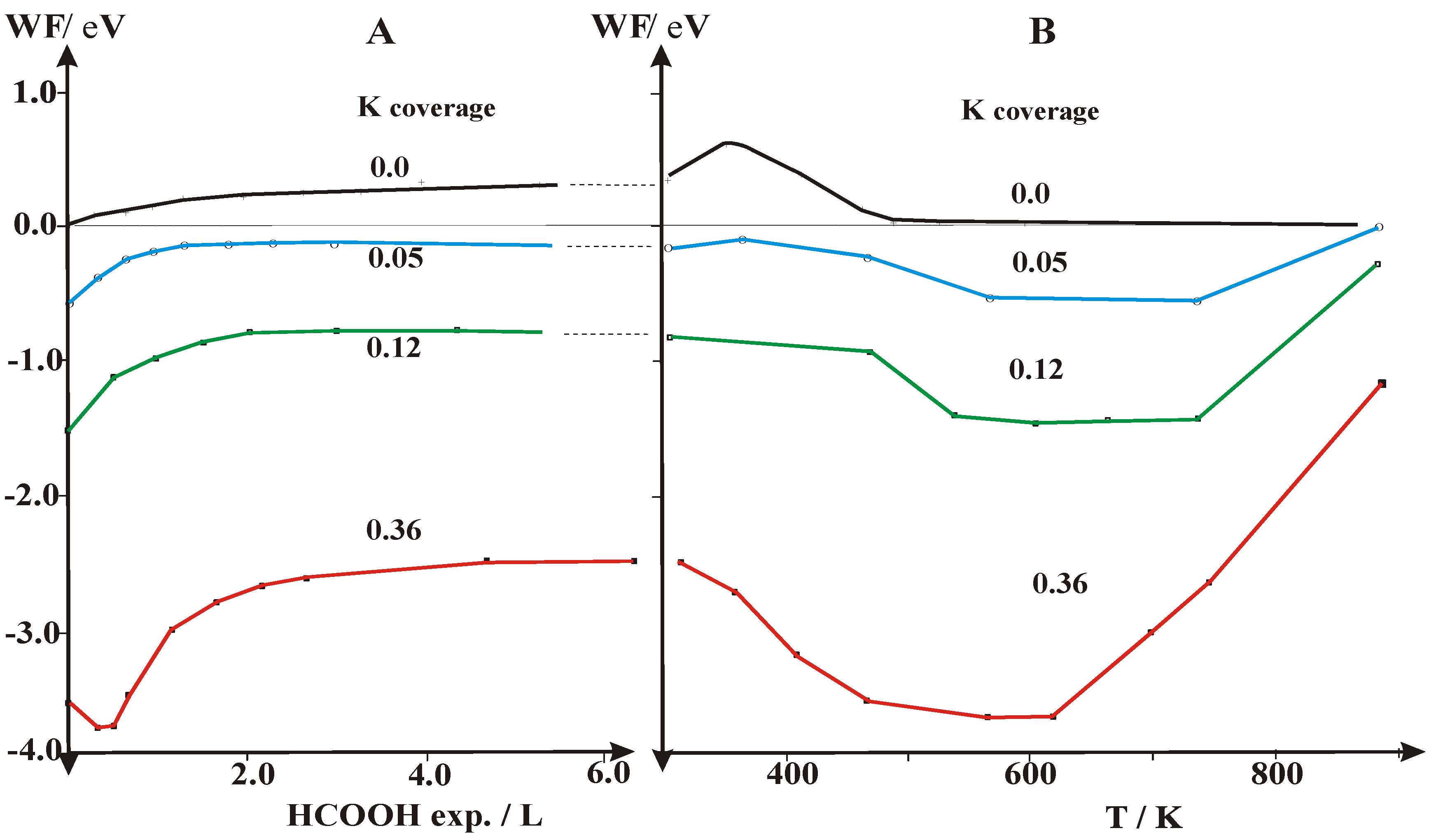

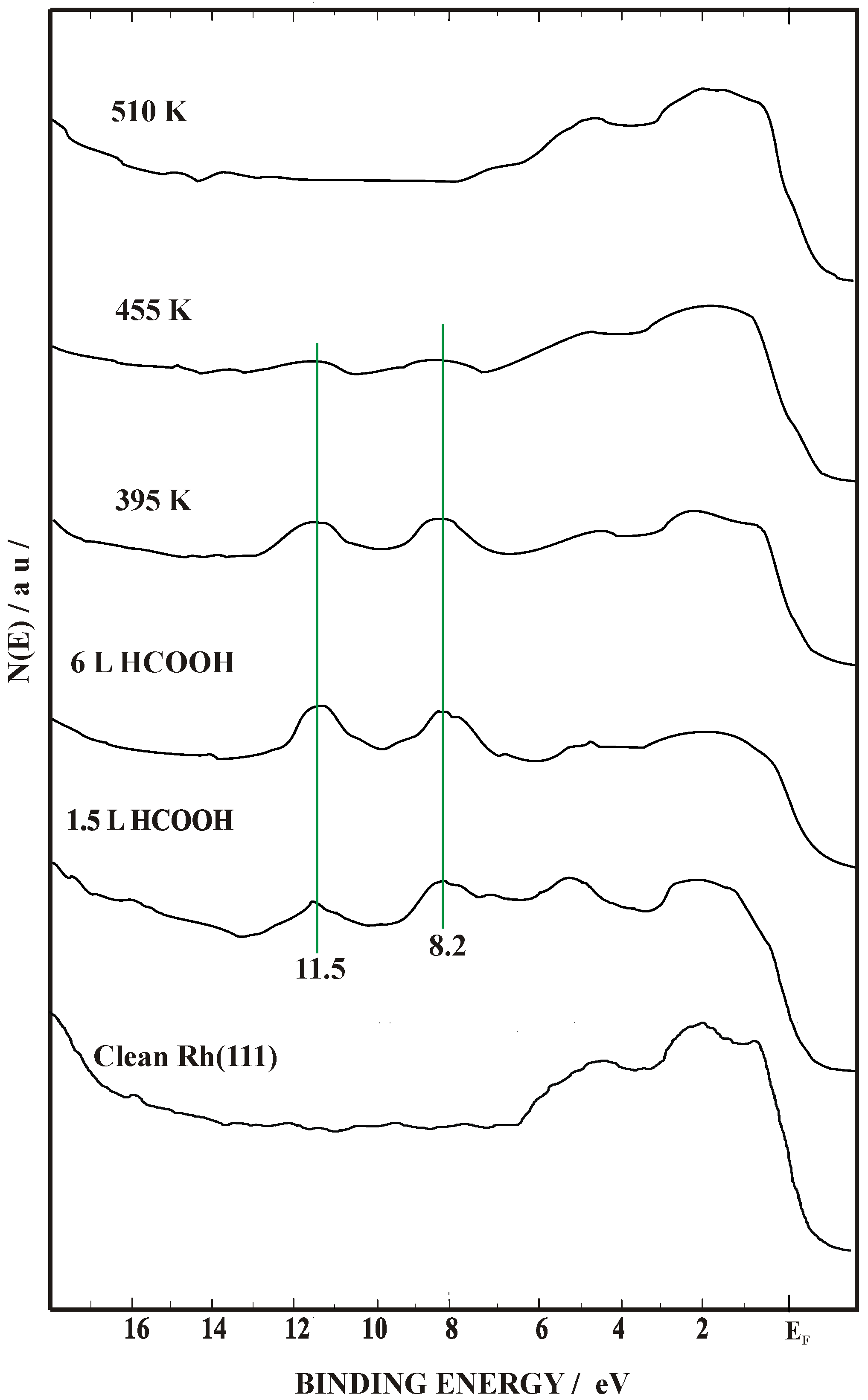

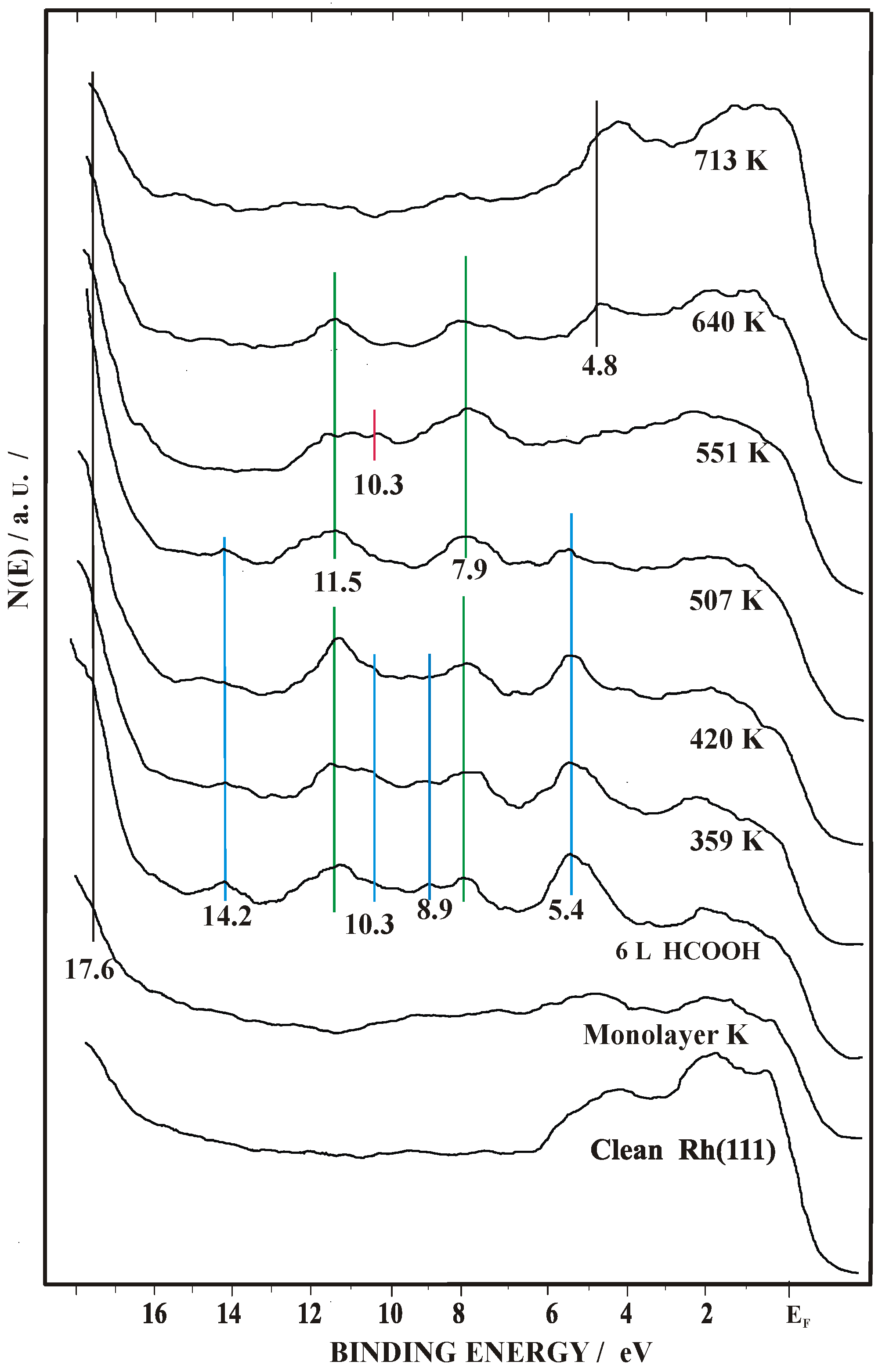

2.2. Work Function (Δϕ) and UPS Measurements

3. Discussion of Surface Reaction Mechanism

4. Experimental

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trillo, J.M.; Munuera, G.; Criado, J.M. Catalytic Decomposition of Formic Acid on Metal Oxides. Catal. Rev. 1972, 7, 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; An, X.; Kurnia, I.; Yoshida, A.; Yang, X.; Hao, X.; Abudula, A.; Fang, Y.; Guan, G. Full Spectrum Decomposition of Formic Acid over γ-Mo2N Based Catalysts: From Dehydration to Dehydrogenation. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5353–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Shen, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X. Involvement of the Unoccupied Site Changes the Kinetic Trend Significantly: A Case Study on Formic Acid Decomposition. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5153–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lolli, G.; Wolf, A.; Mleczko, L. Closing the Gap in Formic Acid Reforming. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2018, 41, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koós, Á.; Solymosi, F. Production of CO-Free H2 by Forming Acid Decomposition over Mo2C/Carbon Catalysts. Catal. Lett. 2010, 138, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthaler, S.; Von Langermann, J.; Schmidt, T. Carbon Dioxide and Formic Acid -The Couple for Environmental-Friendly Hydrogen Storage? Energy Environ. 2010, 3, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinger, J.; Huang, K.-W. Formic Acid as a Hydrogen Energy Carrier. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasi, G.; Schubert, G.; Solymosi, F. Photodecomposition of formic acid on N-doped and metal-modified TiO2: Production of CO-free H2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15396–15405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, N.; Kanega, R.; Fujita, E.; Himeda, Y. Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation and Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Catalyzed by Iridium Complexes Bearing Pyridyl-Pyrzole Ligands: Effect of an Electron-Donating Substituent on the Pyrazole Ring on the Catalytic Activity and Durability. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gracia, J.R.; Fierro-Gonzales, J.C.; Handy, B.E.; Hinojosa-Reyes, L.; De Haro Del Rio, D.A.; Lucio-Ortiz, C.J.; Valle-Cervantes, S.; Flores-Escamilla, G.A. An In Situ Infrared Study of CO2 Hydrogenation to Formic Acid by Using Rhodium Supported on Titanate Nanotubes as Catalysts. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 4206–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.; Brunner, B.; Jess, A.; Wasserscheide, P.; Albert, J. Biomass Oxidation to Formic Acid Aqueous Media Using Polyoxometalate Catalysts—Boosting FA Selectivity by in-Situ Extraction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2985–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, D.-J.; Deng, L.; Guo, Q.-X.; Fu, Y. Catalytic Air Oxidation of Biomass-Derived Carbohydrates to Formic Acid. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovács, I.; Kiss, J.; Solymosi, F. On the role of adsorbed formate in the oxidation of C1 species on clean and modified Pd(100) surfaces. Vacuum 2017, 138, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenoble, D.C.; Estadt, M.M.; Ollis, D.F. The chemistry and catalysis of the water gas shift reaction:1 The kinetics over supported metal catalysts. J. Catal. 1981, 67, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.B.; Chand, R.; Upadhyay, S.N.; Mishra, P.K. Performance of water gas shift reaction catalysts: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienemann, A.; Hindermann, R.; Brault, R.; Idriss, H. Alcohols synthesis from carbon oxides and hydrogen on palladium and rhodium catalysts. Study of active species. Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Petrol. Chem. 1986, 31, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ud Din, I.; Shaharun, M.S.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alharthi, A.I.; Naeem, A. Recent developments of heterogeneous catalytic CO2 reduction to methanol. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lo, C.S. Mechanistic and microkinetic analysis of CO2 hydrogenation on ceria. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 7987–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.; Kukovecz, Á.; Kónya, Z. Beyond Nanoparticles: The Role of Sub-nanosized Metal Species in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Catal. Lett. 2019, 149, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui-López, R.; Mota, N.; Llorente, J.; Millan, E.; Pawelec, B.; Fierro, J.L.G.; Navarro, R.M. Methanol Synthesis from CO2: A Review of Latest Developments in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Materials 2019, 12, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Tombácz, I.; Kocsis, M. Hydrogenation of CO on supported Rh catalyst. J. Catal. 1982, 75, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbo, L.; Visconti, C.G.; Lietti, L.; Szanyi, J. The effect of CO and CO2 methanation over Ru/Al2O3 catalysts: A combined steady state reactivity and transient DRIFT spectroscopy study. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 256, 11779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; Boffa, A.B.; Salmeron, M.; Bell, A.T.; Somorjai, G.A. The kinetics of CO2 hydrogenation on a Rh foil promoted by titania overlayer. Catal. Lett. 1991, 9, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Erdőhelyi, A.; Bánsági, T. Methanation of CO2 on supported rhodium catalyst. J. Catal. 1981, 68, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.A.; Worley, S.D. An infrared study of the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide on supported rhodium catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. 1985, 89, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sápi, A.; Halasi, G.; Kiss, J.; Dobó, D.G.; Juhász, K.I.; Kolcsár, V.J.; Matolin, V.; Erdőhelyi, A.; Kukovecz, Á.; Kónya, Z. In-Situ DRIFTS and NAP-XPS Exploration of the Complexity of CO2 Hydrogenation Over Size Controlled Pt Nanoparticles Supported on Mesoporous NiO. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 5553–5565. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Kwak, J.H.; Szanyi, J. Mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation on Pt/Al2O3 Catalysts. J. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6337–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hong, Y.; Shi, H.; Shi, H.; Szanyi, J. Kitetic modelling and transient DRIFTS-MS studies of CO2 methanation over Ru/Al2O3 catalysts. J. Catal. 2016, 343, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- László, B.; Baán, K.; Varga, E.; Oszkó, A.; Erdőhelyi, A.; Kónya, Z.; Kiss, J. Photo-induced reactions in the CO2-methane system on titanate nanotubes modified with Au and Rh nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 199, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukovecz, Á.; Kordás, K.; Kiss, J.; Kónya, Z. Atomic scale characterization and surface chemistry of metal modified titanate nanotubes and nanowires. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2016, 71, 473–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, P.; Macario, A.; Ferraro, M.; Antonucci, P. Supported Catalysts for CO2 Metanation: A Review. Catalysts 2017, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdőhelyi, A. Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide on Supported Rh Catalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, G.; Sápi, A.; Varga, T.; Baán, K.; Szenti, I.; Halasi, G.; Mucsi, R.; Óvári, L.; Kiss, J.; Fogarassy, Z.; et al. Ambient pressure CO2 hydrogenation over a cobalt/manganese-oxide nanostructured interface: A combined in situ and ex situ study. J. Catal. 2020, 386, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.; Sápi, A.; Tóth, M.; Kukovecz, Á.; Kónya, Z. Rh-Induced Support Transformation and Rh Incorporation in Titanate Structures and Their Influence on Catalytic Activity. Catalysts 2020, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Kiss, J. Interaction of HCOOH with Rhodium Surface Studied by Auger Electron, Electron Energy Loss and Thermal Desorption Spectroscopy. J. Catal. 1983, 88, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K.; Steinhausen, M.; Wandelt, K. Catalytic and electro-catalytic oxidation of formic acid on pure and Cu-modified Pd[111]-surface. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2008, 616, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moller, P.M.; Godowski, P.J.; Onsgaard, J. Adsorption and decomposition of formic acid on potassium-modified Cu(110). Vacuum 1999, 54, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomes, R.L.; King, D.A. Potassium-promoted synthesis of surface formate and reactions of formic acid on Co[1010]. Surf. Sci. 1996, 349, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, F.C.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Campbell, C.T. Adsorption and reaction of HCOOH on doped Cu(110): Coadoption with cesium, oxygen and Csa + Oa. Surf. Sci. 1990, 236, 282–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, T.; Minami, N.; Aruga, T.; Takagi, N.; Nishijima, M. Adsorption and Thermal Decomposition of Formic Acid on the Si(100)(2x1)-K Surface. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 7007–7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbaugh, T.L.; Karp, E.M.; Campbell, C.T. Energetics of Formic Acid Conversion to Adsorbed Formates on Pt(111) by Transient Calorimetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3964–3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zaera, F. Adsorption and thermal chemistry of formic acid on clean and oxygen-pedosed Cu(110) single-crystal surfaces revisited. Surf. Sci. 2016, 646, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Kiss, J.; Kovács, I. Adsorption of HCOOH and its reaction with preadsorbed oxygen. Surf. Sci. 1987, 192, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Kiss, J. The Effect of Boron Impurity on the Adsorption and Dissociation of CO2 on Rh Surfaces. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1984, 110, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kiss, J.; Solymosi, F. Adsorption of H2O on Clean and Boron-Contaminated Rh Surface. Surf. Sci. 1986, 177, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kiss, J.; Révész, K.; Solymosi, F. Segregation of Boron and Its Reaction with Oxygen on Rh. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1989, 37, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Kiss, J.; Kovács, I. Adsorption and Decomposition of Formic Acid on Clean and Potassium Dosed Rh(111) Surfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 1987, A5, 1108–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solymosi, F.; Kiss, J.; Kovács, I. Adsorption and Decomposition of HCOOH on Potassium Promoted Rh(111) Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Bugyi, L. Adsorption and Dissociation of CO2 on a Potassium-promoted Rh(111) Surface. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. I 1987, 83, 2015–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, J.J.; Umbach, E.; Menzel, D. The properties of K and CO + K on Ru(001) I. Adsorption, desorption, and structure. Surf. Sci. 1985, 155, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.; Révész, K.; Solymosi, F. Photoelectron Spectroscopy Studies of the Adsorption of CO2 on Potassium-Promoted Rh(111) Surface. Surf. Sci. 1988, 207, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crowell, J.E.; Somorjai, G.A. The Effect of Potassium on the Chemisorption of Carbon Monoxide on the Rh(111) Crystal Face. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1984, 19, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskinova, M.; Pirug, G.; Bonzel, H.P. Coadsorption of Potassium and CO on Pt(111). Surf. Sci. 1983, 133, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonzel, H.P. Alkali-promoted gas adsorption and surface reaction on metals. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A2 1984, 2, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, D.E.; Peebles, H.C.; White, J.M. Electron spectroscopic study of the interaction of coadsorbed CO and D2 on Rh(100) at low temperature. Surf. Sci. 1984, 136, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.; Klivényi, G.; Révész, K.; Solymosi, F. Photoelectron Spectroscopic Studies on the Dissociation of CO on Potassium-dosed Rh(111) surface. Surf. Sci. 1989, 223, 551–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thiel, P.A. The Interaction of Water with Solid Surface: Fundamental Aspects. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1987, 7, 211–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, H.-J.; Roberts, M.W. Surface Chemistry of Carbon Dioxide. Surf. Sci. Rep. 1996, 25, 225–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Berkó, A. Adsorption of CO2 on Clean and Potassium-Covered Pd(100) Surfaces. J. Catal. 1986, 101, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barteau, M.A.; Madix, R.J. A study of the relative brönsted acidities complexes on Ag(110). Surf. Sci. 1982, 120, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, B.A.; Hughes, A.E.; Avery, N.R. A spectroscopic study of the adsorption and reaction of methanol, formaldehyde and formate on clean and oxygenated Cu(110). Surf. Sci. 1985, 155, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felter, T.E.; Weinberg, W.H.; Lastushkina, G.Y.; Boronin, A.J.; Zhdan, P.A.; Boreskov, G.K. An XPS and UPS study of the kinetics of carbon monoxide oxidation over Ag(111). Surf. Sci. 1982, 118, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Roberts, C.A.; Perkins, R.T.; Wash, I.E. Revisiting formic acid decomposition on metallic power catalysts: Exploding the HCOOH decomposition volcano curve. Surf. Sci. 2016, 650, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, S.; Yan, B.; Chen, J.G.; Liu, P. CO2 hydrogenation on Pt, Pt/SiO2 and Pt/TiO2: Importance of synergy between Pt and support. J. Catal. 2016, 343, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Kovács, I. Adsorption and reaction of HCOOH on K-promoted Pd(100) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 1991, 259, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Berkó, A.; Tóth, Z. Adsorption and dissociation of CH3OH on clean and K-promoted Pd(100) surfaces. Surf. Sci. 1993, 285, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskó, J.; Bontovics, J.; Solymosi, F. FTIR study of the interaction of methanol with clean and potassium-doped Pd/SiO2. J. Catal. 1994, 146, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijapalaa, R.; Yu, F.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Mlasna, T.T. K-promoted Mo/Co- and Mo/Ni-catalysised Fischer-Tropsch synthesis of aromatic hydrocarbons with and without a Cu water gas shift catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 480, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, J.A.; Scaranto, J.; Ferrin, P.; Li, S.; Mavrikakis, M. Trends in Formic Acid Decomposition on Model Transition Metal Surfaces: Density Functional Theory study. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 4434–4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakurt, B.; Kocak, Y.; Ozensoy, E. Enhancemet of Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Selectivity of Pd(111) Single Crystal Model Catalysts Surface via Brønsted Bases. J. Phys. Chem. 2019, 123, 28777–28788. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, T.; Halmos, Z.; Seybold, K.; Pungor, E. The thermal decomposition of alkali metal formats. J. Thermal. Anal. 1975, 7, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| θK | UPS | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCOOH only at 100K | 0 | 6.2 8.9 10.5 11.9 | [43] |

| 0.1 | 6.2 9.1 10.5 12.0 | [48] | |

| 0.33 | 6.2 9.1 10.5 12.0 | [48] | |

| HCOO− | 0 | 5.3 8.9 10.2 13.2 | [43,60,61] |

| 0.1 | 5.2 8.9 10.2 14.2 | [48] | |

| 0.33 | 5.2 8.9 10.3 14.0 | [48], this work | |

| CO32− | 0.33 | 8.4 10.2 | [48,62] this work |

| CO | 0 | 8.0 10.8 | [55,56] |

| 0.1 | 8.0 10.9 | [48] | |

| 0.33 | 9.0 11.5 | [48,51], this work | |

| O | 0 | ~6 | [57] |

| 0.33 | 5.2 | [56,57], this work |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovács, I.; Kiss, J.; Kónya, Z. The Potassium-Induced Decomposition Pathway of HCOOH on Rh(111). Catalysts 2020, 10, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10060675

Kovács I, Kiss J, Kónya Z. The Potassium-Induced Decomposition Pathway of HCOOH on Rh(111). Catalysts. 2020; 10(6):675. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10060675

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovács, Imre, János Kiss, and Zoltán Kónya. 2020. "The Potassium-Induced Decomposition Pathway of HCOOH on Rh(111)" Catalysts 10, no. 6: 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10060675

APA StyleKovács, I., Kiss, J., & Kónya, Z. (2020). The Potassium-Induced Decomposition Pathway of HCOOH on Rh(111). Catalysts, 10(6), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10060675