Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Corresponding Amides in Air with Rh(I)-N-Heterocyclic Complex Catalysts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

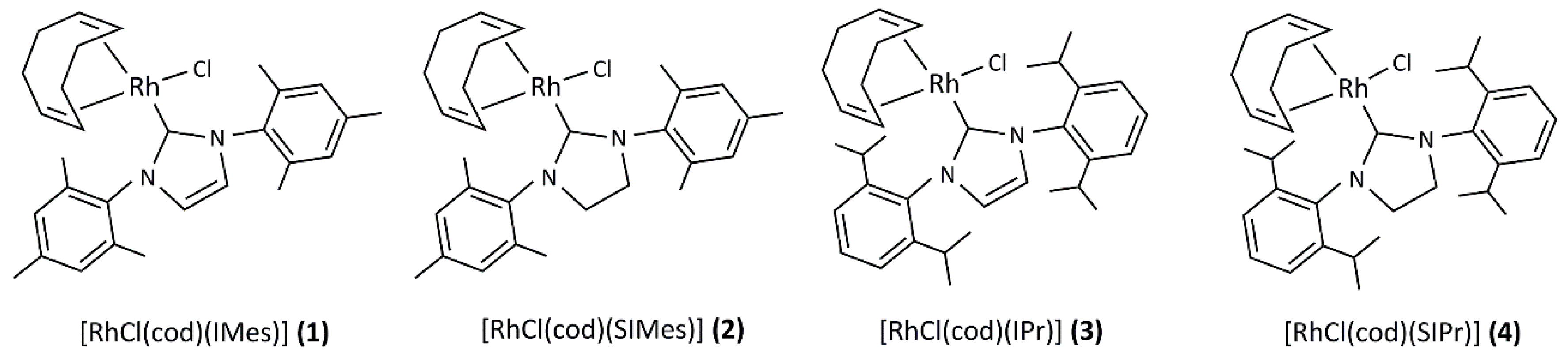

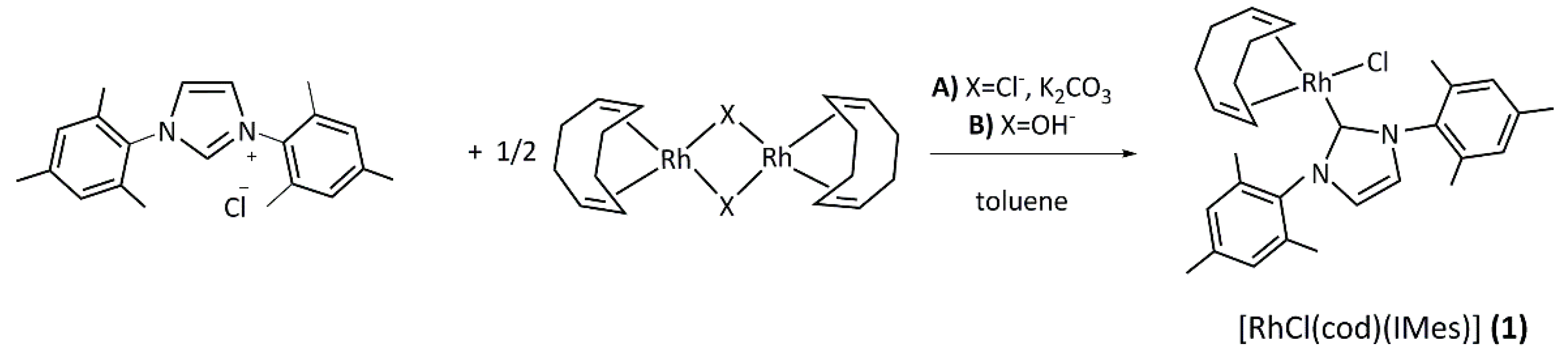

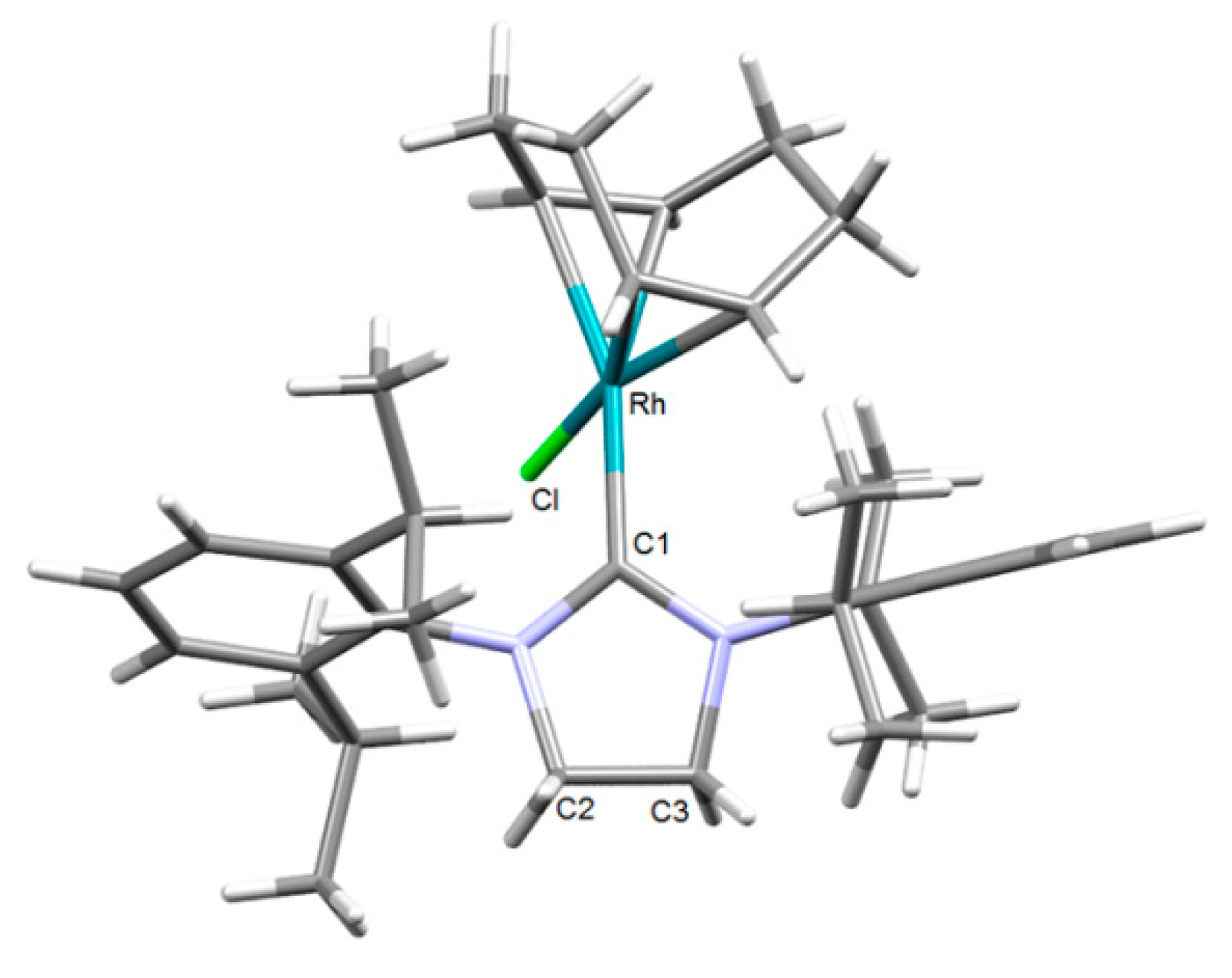

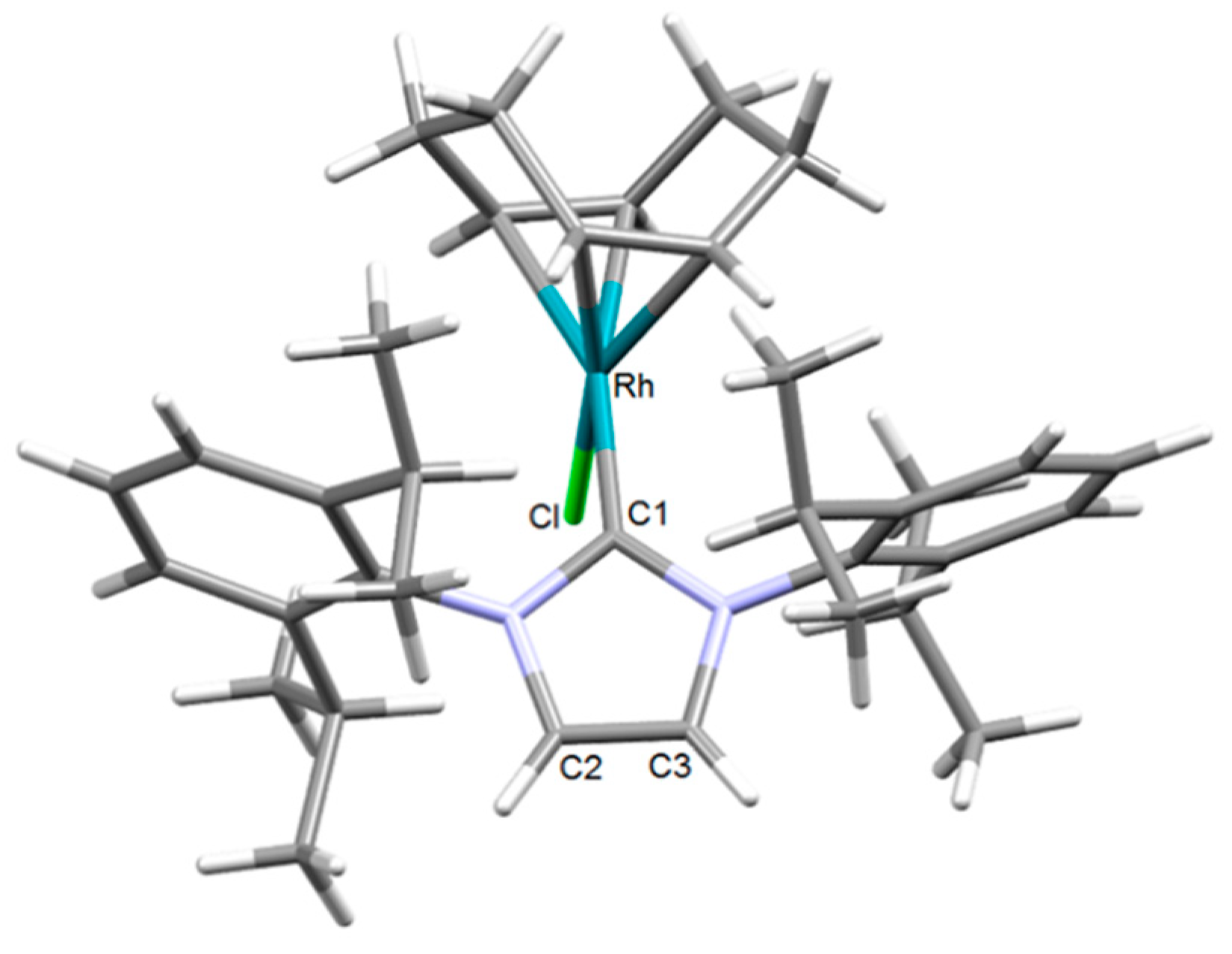

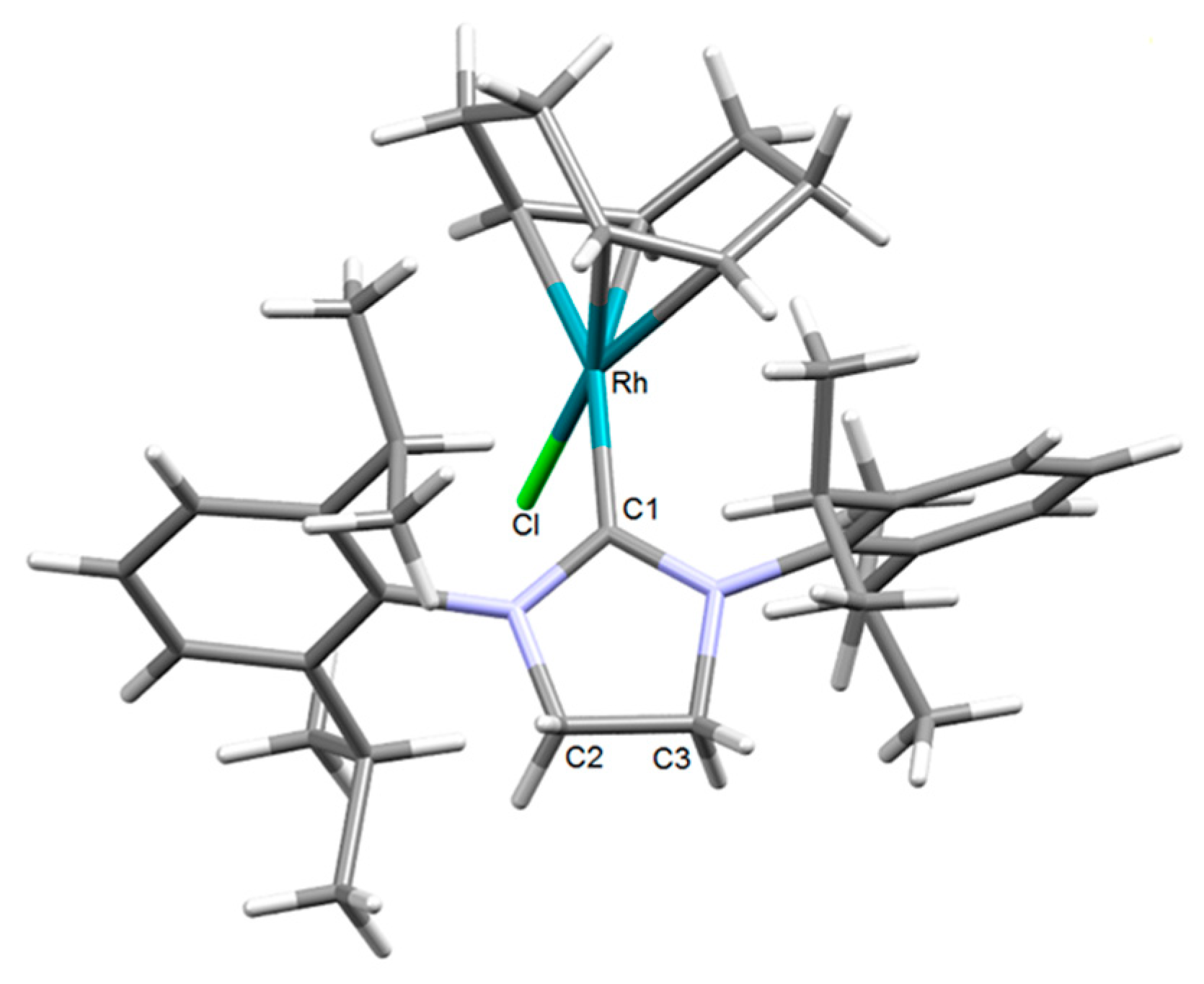

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of the [RhCl(cod)(NHC)] Complexes 1–4

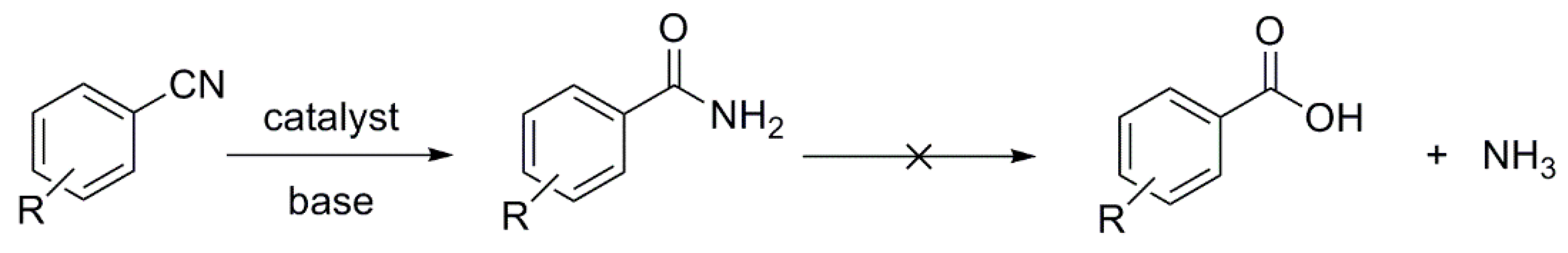

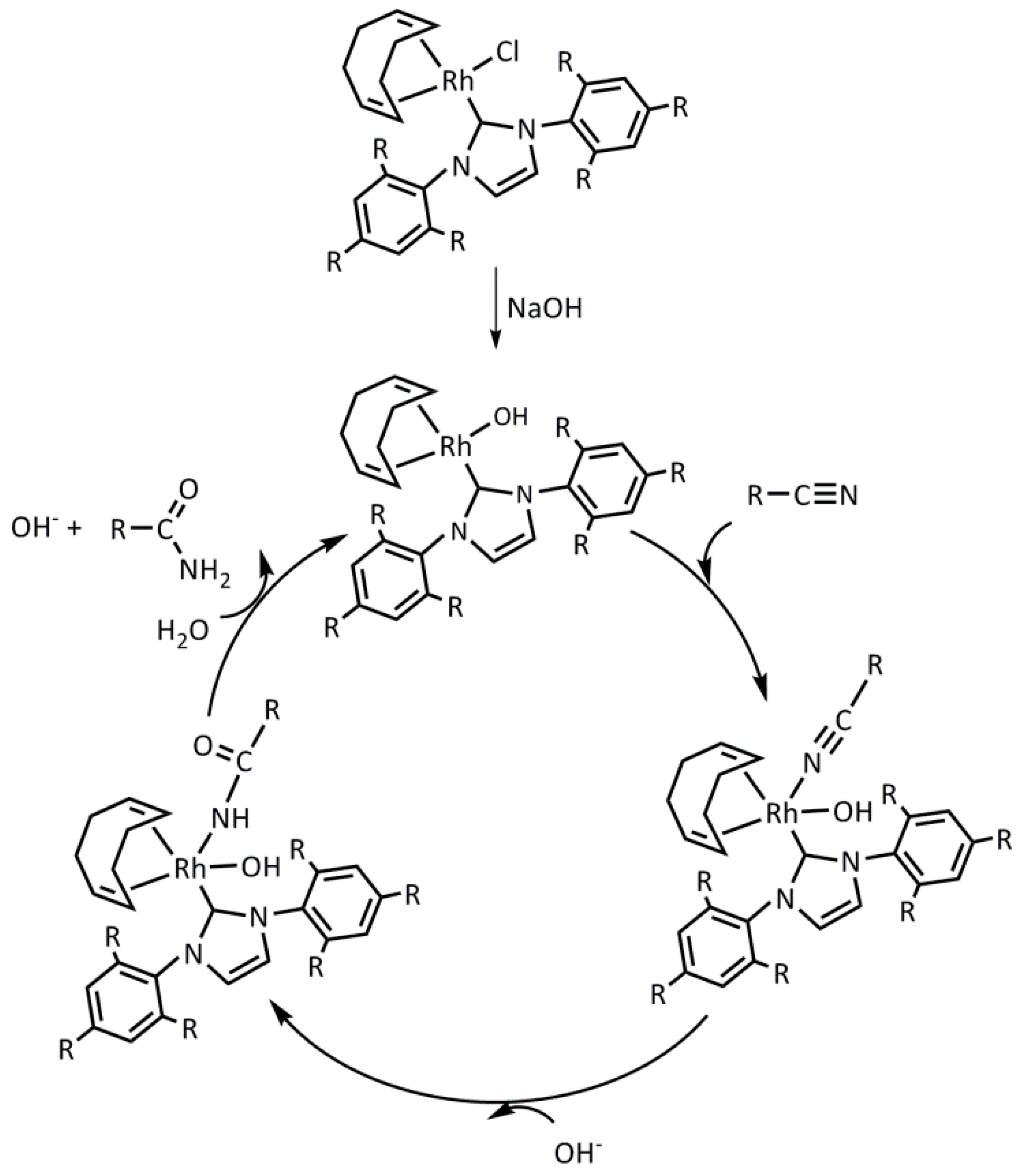

2.2. Hydration of Aromatic Nitriles Catalyzed by the [RhCl(cod)(NHC)] Complexes 1–4

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of [RhCl(cod)(NHC)] Complexes

3.3. General Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, T.J.; Knapp, S.M.M.; Tyler, D.R. Frontiers in catalytic nitrile hydration: Nitrile and cyanohydrin hydration catalyzed by homogeneous organometallic complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 949–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.L.; Williams, J.M.J. Metal-catalysed approaches to amide bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3405–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Xu, J.H. Biocatalysis in development of green pharmaceutical processes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi Miraki, M.; Arefi, M.; Salamatmanesh, A.; Yazdani, E.; Heydari, A. Magnetic Nanoparticle-Supported Cu–NHC Complex as an Efficient and Recoverable Catalyst for Nitrile Hydration. Catal. Lett. 2018, 148, 3378–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, R.B.N.; Varma, R.S. A facile one-pot synthesis of ruthenium hydroxide nanoparticles on magnetic silica: Aqueous hydration of nitriles to amides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6220–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.Y.; Bae, H.S.; Park, S.; Park, S.; Park, K.H. Silver Nanoparticle Catalyzed Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Amides in Water Under Neutral Conditions. Catal. Lett. 2011, 141, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Matsushita, M.; Mizuno, N. Efficient Hydration of Nitriles to Amides in Water, Catalyzed by Ruthenium Hydroxide Supported on Alumina. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakouraj, M.M.; Baharami, K. Selective conversion of nitriles to amides by Amberlyst A-26 supported hydroperoxide. Indian J. Chem. 1999, 38B, 974–975. [Google Scholar]

- Hussian, M.A.; Kim, J.W. Environmentally Friendly Synthesis of Amide by Metal-catalyzed Nitrile Hydration in Aqueous Medium. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2015, 26, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsuoka, A.; Isogawa, T.; Morioka, Y.; Knappett, B.R.; Wheatley, A.E.H.; Saito, S.; Naka, H. Hydration of nitriles to amides by a chitin-supported ruthenium catalyst. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 12152–12160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Mendivil, E.; García-Álvarez, R.; Vidal, C.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Exploring Rhodium(I) Complexes [RhCl(COD)(PR3)] (COD = 1,5-Cyclooctadiene) as Catalysts for Nitrile Hydration Reactions in Water: The Aminophosphines Make the Difference. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 1901–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, M.K.; van Duin, K.; van Dijk, T.; de Pater, J.J.M.; Deelman, B.J.; Nieger, M.; Ehlers, A.W.; Slootweg, J.C.; Lammertsma, K. Iminophosphanes: Synthesis, Rhodium Complexes, and Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Hydration of Nitriles. Organometallics 2017, 36, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Frost, B.J. Aqueous and biphasic nitrile hydration catalyzed by a recyclable Ru(II) complex under atmospheric conditions. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyog-Nagy, E.; Udvardy, A.; Joó, F.; Kathó, Á. Efficient and selective hydration of nitriles to amides in aqueous systems with Ru(II)-phosphaurotropine catalysts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 3615–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.; Horváth, H.; Sola, E.; Kathó, Á.; Joó, F. Water-Soluble Triisopropylphosphine Complexes of Ruthenium(II): Synthesis, Equilibria, and Acetonitrile Hydration. Organometallics 2009, 28, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Sarbajna, A.; Dutta, I.; Pandey, P.; Bera, J.K. Hemilability-Driven Water Activation: A Ni(II) Catalyst for Base-Free Hydration of Nitriles to Amides. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 7761–7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, M.L.; Cadierno, V.; Esteruelas, M.A.; Gimeno, J.; Herrero, J.; Izquierdo, S.; Oñate, E. Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Amides Promoted by an Os–NHC Catalyst: Formation and X-ray Characterization of κ2-Amidate Intermediates. Organometallics 2012, 31, 6861–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Suárez, A.; Oonishi, Y.; Meiries, S.; Nolan, S.P. [{Au(NHC)}2(μ-OH)][BF4]: Silver-Free and Acid-Free Catalysts for Water-Inclusive Gold-Mediated Organic Transformations. Organometallics 2013, 32, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaper, L.A.; Hock, S.J.; Herrmann, W.A.; Kühn, F.E. Synthesis and Application of Water-Soluble NHC Transition-Metal Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riener, K.; Haslinger, S.; Raba, A.; Högerl, M.P.; Cokoja, M.; Herrmann, W.A.; Kühn, F.E. Chemistry of Iron N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes: Syntheses, Structures, Reactivities, and Catalytic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5215–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.; Ivry, E.; Diesendruck, C.E.; Lemcoff, N.G. Water in N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Assisted Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4607–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, S.; Udvardy, A.; Czégéni, C.E.; Joó, F. Poly-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes with applications in aqueous media. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 400, 213038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, S.J.; Schaper, L.A.; Herrmann, W.A.; Kühn, F.E. Group 7 transition metal complexes with N-heterocyclic carbenes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5073–5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukushkin, V.Y.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Additions to Metal-Activated Organonitriles. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1771–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukushkin, V.Y.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Metal-mediated and metal-catalyzed hydrolysis of nitriles. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2005, 358, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, R.S.; Marion, N.; Nolan, S.P. Gold Activation of Nitriles: Catalytic Hydration to Amides. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 8695–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francos, J.; Elorriaga, D.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. The chemistry of Group 8 metal complexes with phosphinous acids and related POH ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 387, 199–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadierno, V. Synthetic Applications of the Parkins Nitrile Hydration Catalyst [PtH(PMe2O)2H(PMe2OH)]: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2015, 5, 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, R.; Crochet, P.; Cadierno, V. Metal-catalyzed amide bond forming reactions in an environmentally friendly aqueous medium: Nitrile hydrations and beyond. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dai, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, M.; Pan, Y. Efficient and selective nitrile hydration reactions in water catalyzed by an unexpected dimethylsulfinyl anion generated in situ from CsOH and DMSO. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2136–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, T.E.; Gómez-Herrera, A.; Songis, O.; Sneddon, D.; Révolte, A.; Nahra, F.; Cazin, C.S.J. Selective NaOH-catalysed hydration of aromatic nitriles to amides. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2865–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midya, G.C.; Kapat, A.; Maiti, S.; Dash, J. Transition-Metal-Free Hydration of Nitriles Using Potassium tert-Butoxide under Anhydrous Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 4148–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshiki, T.; Yamashita, H.; Sawada, K.; Utsunomiya, M.; Takahashi, K.; Takai, K. Dramatic Rate Acceleration by a Diphenyl-2-pyridylphosphine Ligand in the Hydration of Nitriles Catalyzed by Ru(acac)2 Complexes. Organometallics 2005, 24, 6287–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounkham, W.L.; Weeden, J.A.; Frost, B.J. Aqueous-Phase Nitrile Hydration Catalyzed by an In Situ Generated Air-Stable Ruthenium Catalyst. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 10013–10020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djoman, M.C.K.B.; Ajjou, A.N. The hydration of nitriles catalyzed by water-soluble rhodium complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 4845–4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Endo, K.; Saito, S. RhI-Catalyzed Hydration of Organonitriles under Ambient Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3607–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, P.; Sinha, A.; Rahaman, S.M.W.; Dinda, S.; Bera, J.K. Bifunctional Water Activation for Catalytic Hydration of Organonitriles. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3790–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Gonzalez, S. (Ed.) N-Heterocyclic Carbenes: From Laboratory Curiosities to Efficient Synthetic Tools; Catalysis Series; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cazin, C.S.J. (Ed.) N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Transition Metal Catalysis and Organocatalysis; Catalysis by Metal Complexes; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, S.P. (Ed.) N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Effective Tools for Organometallic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, H.V. The Organometallic Chemistry of N-heterocyclic Carbenes; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, M.J.; Lappert, M.F.; Pye, P.L.; Terreros, P. Carbene complexes. Part 18. Synthetic routes to electron-rich olefin-derived monocarbenerhodium(I) neutral and cationic complexes and their chemical and physical properties. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 2355–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, W.A.; Köcher, C.; Gooßen, L.J.; Artus, G.R.J. Heterocyclic Carbenes: A High-Yielding Synthesis of Novel, Functionalized N-Heterocyclic Carbenes in Liquid Ammonia. Chem. Eur. J. 1996, 2, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, B.J.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Nolan, S.P. Well-defined NHC-rhodium hydroxide complexes as alkene hydrosilylation and dehydrogenative silylation catalysts. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, H.; Çetinkaya, B. N-heterocyclic carbene complexes of Rh(I) and electronic effects on catalysts for 1,2-addition of phenylboronic acid to aldehydes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 25, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Y.; Patrick, B.O.; James, B.R. New Rhodium(I) Carbene Complexes from Carbene Transfer Reactions. Organometallics 2006, 25, 2359–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittermann, A.; Baskakov, D.; Herrmann, W.A. Carbene Complexes Made Easily: Decomposition of Reissert Compounds and Further Synthetic Approaches. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5107–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savka, R.; Plenio, H. Facile synthesis of [(NHC)MX(cod)] and [(NHC)MCl(CO)2] (M = Rh, Ir; X = Cl, I) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, B.; Ma, J.A.; Dang, Y. Mechanistic understanding of [Rh(NHC)]-catalyzed intramolecular [5 + 2] cycloadditions of vinyloxiranes and vinylcyclopropanes with alkynes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4295–4303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Chang, S.; Lee, H.Y. Anhydrous Hydration of Nitriles to Amides using Aldoximes as the Water Source. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5598–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.Y. Anhydrous Hydration of Nitriles to Amides: P-Carbomethoxybenzamide. Org. Synth. 2014, 89, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Denk, K.; Sirsch, P.; Herrmann, W.A. The first metal complexes of bis(diisopropylamino)carbene: Synthesis, structure and ligand properties. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 649, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Plenio, H. Synthesis of (NHC)Rh(cod)Cl and (NHC)RhCl(CO)2 complexes—Translation of the Rh- into the Ir-scale for the electronic properties of NHC ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Park, S.Y.; Park, J.H.; Jung, I.G.; Choi, S.Y.; Chung, Y.K.; Lee, B.Y. Rhodium N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Catalyzed [4 + 2] and [5 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.P.; Ritter, T.; Grubbs, R.H. Synthesis of N-Heterocylic Carbene-Containing Metal Complexes from 2-(Pentafluorophenyl)imidazolidines. Organometallics 2007, 26, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülcemal, S. Symmetric and dissymmetric N-heterocyclic carbene rhodium(I) complexes: A comparative study of their catalytic activities in transfer hydrogenation reaction. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2012, 26, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly III, R.A.; Clavier, H.; Giudice, S.; Scott, N.M.; Stevens, E.D.; Bordner, J.; Samardjiev, I.; Hoff, C.D.; Cavallo, L.; Nolan, S.P. Determination of N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Steric and Electronic Parameters using the [(NHC)Ir(CO)2Cl] System. Organometallics 2008, 27, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, K.; Papp, G.; Kathó, Á.; Joó, F.; Horváth, H. Strong Solvent Effects on Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones with [Ir(cod)(NHC)(PR3)] Catalysts in 2-Propanol-Water Mixtures. Catalysts 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M. Catalytic Properties of N-heterocyclic Transition Metal Carbene Complexes. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, G.; Crabtree, R.H.; Heintz, R.M.; Forster, D.; Morris, D.E. Di-μ-Chloro-Bis(η4-1,5-Cyclooctadiene)-Dirhodium(I). In Inorganic Syntheses; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 28, pp. 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fandos, R.; Hernández, C.; Otero, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Ruiz, M.J.; García Fierro, J.L.; Terreros, P. Rhodium and Iridium Hydroxide Complexes [M(μ-OH)(COD)]2 (M = Rh, Ir) as Versatile Precursors of Homo and Early−Late Heterobimetallic Compounds. X-ray Crystal Structures of Cp*Ta(μ3-O)4[Rh(COD)]4 (Cp* = η5-C5Me5) and [Ir(2-O-3-CN-4,6-Me2-C5HN)(COD)]2. Organometallics 1999, 18, 2718–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigle, D.J.; Decuir, T.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Darensbourg, D.J. 1,3,5-Triaz-7-Phosphatricyclo[3.3.1.13,7]Decane and Derivatives. Inorg. Synth. 1998, 32, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Joó, F.; Kovács, J.; Kathó, Á.; Bényei, A.C.; Decuir, T.; Darensbourg, D.J.; Miedaner, A.; Dubois, D.L. (Meta-Sulfonatophenyl) Diphenylphosphine, Sodium Salt and its Complexes with Rhodium(I), Ruthenium(II), Iridium(I). In Inorganic Syntheses; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burla, M.C.; Caliandro, R.; Camalli, M.; Carrozzini, B.; Cascarano, G.L.; De Caro, L.; Giacovazzo, C.; Polidori, G.; Siliqi, D.; Spagna, R. IL MILIONE: A suite of computer programs for crystal structure solution of proteins. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrip, S.P. publCIF: Software for editing, validating and formatting crystallographic information files. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2010, 43, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; Streek, J.V.D.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APEX3 v2017.3-0; Bruker AXS Inc.: Billerica, MA, USA, 2017.

- Brunjes, A.S.; Bogart, M.J.P. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria for Commercially Important Systems of Organic Solvents: The Binary Systems Ethanol-n-Butanol, Acetone-Water and Isopropanol-Water. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1943, 35, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [RhCl(cod)(IPr)] (3) [54] | [RhCl(cod)(SIPr)] (4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh–Ccarbene | 2.056(4) | 2.052(1) | 2.043(3) | 2.053(1) |

| Rh–Cl | 2.3467(12) | 2.3713(12) | 2.3721(11) | 2.3466(10) |

| C2–C3 | - | - | 1.501(7) | 1.487(7) |

| C2=C3 | 1.328(6) | 1.324(5) | - | - |

| Ccarbene–Rh–Cl | 85.61(11) | 88.26(11) | 86.92(9) | 84.32(10) |

| [RhCl(cod)(IPr)]_benzene_3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh–Ccarbene | 2.050(4) | 2.031(4) | 2.032(4) | 2.051(4) |

| Rh–Cl | 2.3752(11) | 2.3726(10) | 2.3706(10) | 2.3775(10) |

| C2=C3 | 1.330(6) | 1.338(6) | 1.339(6) | 1.333(6) |

| Ccarbene–Rh–Cl | 89.01(11) | 88.33(11) | 87.76(11) | 89.43(10) |

| [RhCl(cod)(SIPr)]_benzene_4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh–Ccarbene | 2.028(7) | 2.034(7) | 2.046(7) | 2.044(7) |

| Rh–Cl | 2.3800(17) | 2.3746(17) | 2.3797(18) | 2.3781(4) |

| C2–C3 | 1.515(11) | 1.505(11) | 1.497(11) | 1.524(10) |

| Ccarbene–Rh–Cl | 87.40(19) | 86.03(19) | 88.80(18) | 88.08(19) |

| Entry | Base | Conversion (%) | TOF a (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 0(3 b) | 0(4 b) |

| 2 | tBuOK | 52 | 69 |

| 3 | KOH | 52 | 69 |

| 4 | K2CO3 | 56 | 75 |

| 5 | NaOH | 59 | 79 |

| Entry | Catalyst (mol%) | Base a | Phosphine | T °C | t (min) | Conversion (%) b | TOF c (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | NaOH | - | 40 | 120 | 48 (0) | 24 |

| 2 | 1 | NaOH | - | 50 | 120 | 72 (1) | 36 |

| 3 | 1 | NaOH | - | 60 | 120 | 82 (1) | 41 |

| 4 | 1 | NaOH | - | 70 | 120 | 91 (3) | 45 |

| 5 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 120 | 98 (6) | 49 |

| 6 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 10 | 46 (1) | 276 |

| 7 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 20 | 63 (1) | 189 |

| 8 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 30 | 74 (2) | 148 |

| 9 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 60 | 86 (3) | 86 |

| 10 | 1 | NaOH | - | 80 | 90 | 94 (5) | 63 |

| 11 | 5 | - | - | reflux | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 5 | - | - | reflux | 120 | 18 | 2 |

| 13 | 5 | - | - | reflux | 180 | 26 | 2 |

| 14 | 5 | NaOH | - | reflux | 10 | 96 | 115 |

| 15 | 5 | NaOH | - | reflux | 20 | 97 | 58 |

| 16 | 5 | NaOH | - | reflux | 60 | >99 | 20 |

| 17 | 5 | - | 0.05 mmol PTA | reflux | 60 | 17 | 3 |

| 18 | 5 | - | 0.15 mmol PTA | reflux | 60 | 70 | 14 |

| 19 | 5 | - | 0.25 mmol PTA | reflux | 60 | 78 | 16 |

| 20 | 5 | - | 0.05 mmol mtppms | reflux | 60 | 75 | 15 |

| 21 | 5 | - | 0.15 mmol mtppms | reflux | 60 | 76 | 15 |

| 22 | 5 | - | 0.25 mmol mtppms | reflux | 60 | 94 | 19 |

| Entry | Catalyst | Conversion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | ||

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 18 | 26 |

| 2 | 1 + NaOH | >99 | - | - |

| 3 | 1 + PTA | 70 | 71 | 77 |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 5 | 2 + NaOH | 99 | >99 | - |

| 6 | 2 + PTA | 69 | 78 | 88 |

| 7 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | 3 + NaOH | 66 | 86 | 93 |

| 9 | 3 + PTA | 54 | 61 | 64 |

| 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 11 | 4 + NaOH | 94 | 98 | - |

| 12 | 4 + PTA | 1 | 47 | 53 |

| Entry | Nitrile | t(h) | 1 + NaOH | NaOH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion (%) | TOF b(h−1) | Conversion c (%) | |||

| 1 | benzonitrile | 1 | 93 | 93 | 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 98 | 49 | 6 | |

| 3 | 4-chlorobenzonitrile | 1 | 88 | 88 | 4 |

| 4 | 2 | 94 | 47 | 6 | |

| 5 | 4-methylbenzonitrile | 1 | 70 | 70 | 1 |

| 6 | 2 | 84 | 42 | 2 | |

| 7 | 4-chlorophenyl-acetonitrile | 1 | 58 | 58 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 | 62 | 31 | 2 | |

| Entry | Substrate | Phosphine | Conversion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | |||

| 1 | 2-pyridinecarbonitrile | - | 6 | 8 | 9 |

| 2 | 2-pyridinecarbonitrile | PTA | 8 | 10 | 11 |

| 3 | 3-pyridinecarbonitrile | - | 88 | 96 | 96 |

| 4 | 3-pyridinecarbonitrile | PTA | > 99 | - | - |

| 5 | 4-pyridinecarbonitrile | - | > 99 | - | - |

| 6 | 4-pyridinecarbonitrile | PTA | > 99 | - | - |

| 7 a | 4-pyridinecarbonitrile | - | 90 | > 99 | - |

| Entry | 1 (mol%) b | t (h) | Conversion (%) | TOF (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 17 | 73 | 4.3 |

| 2 | 1 | 22 | 79 | 3.6 |

| 3 | 1 | 40 | 94 | 2.4 |

| 4 | 2 | 17 | 84 | 2.5 |

| 5 | 2 | 22 | 85 | 1.9 |

| 6 | 2.5 | 17 | 94 | 2.2 |

| 7 | 2.5 | 19 | 96 | 2.0 |

| 8 | 2.5 | 24 | 99 | 1.7 |

| 9 c | 1 | 17 | 34 | 2.0 |

| 10 c | 1 | 34 | 60 | 1.8 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czégéni, C.E.; De, S.; Udvardy, A.; Derzsi, N.J.; Papp, G.; Papp, G.; Joó, F. Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Corresponding Amides in Air with Rh(I)-N-Heterocyclic Complex Catalysts. Catalysts 2020, 10, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10010125

Czégéni CE, De S, Udvardy A, Derzsi NJ, Papp G, Papp G, Joó F. Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Corresponding Amides in Air with Rh(I)-N-Heterocyclic Complex Catalysts. Catalysts. 2020; 10(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzégéni, Csilla Enikő, Sourav De, Antal Udvardy, Nóra Judit Derzsi, Gergely Papp, Gábor Papp, and Ferenc Joó. 2020. "Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Corresponding Amides in Air with Rh(I)-N-Heterocyclic Complex Catalysts" Catalysts 10, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10010125

APA StyleCzégéni, C. E., De, S., Udvardy, A., Derzsi, N. J., Papp, G., Papp, G., & Joó, F. (2020). Selective Hydration of Nitriles to Corresponding Amides in Air with Rh(I)-N-Heterocyclic Complex Catalysts. Catalysts, 10(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10010125