Favoritism and Fairness in Teams

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design and Hypotheses

3. Results

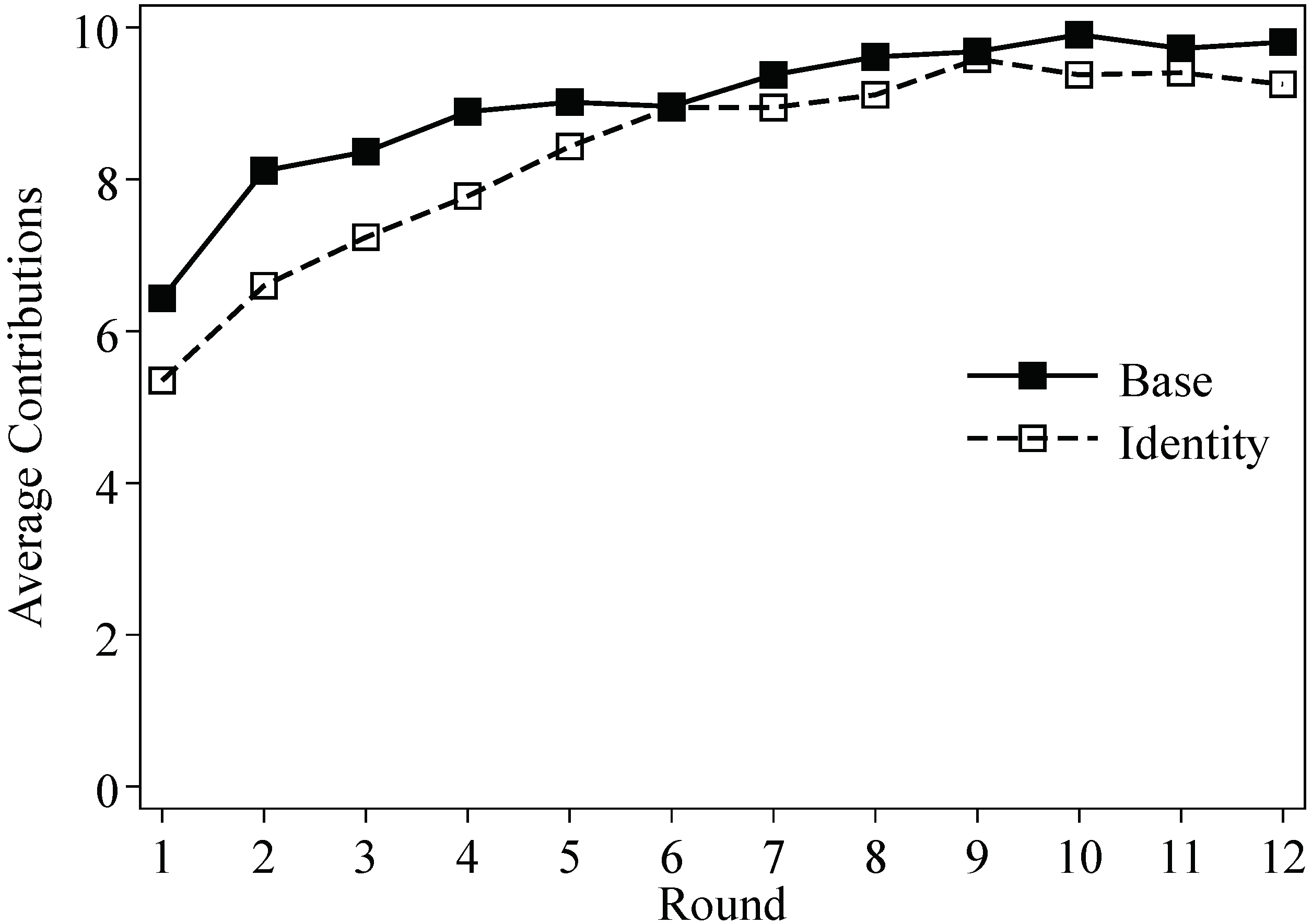

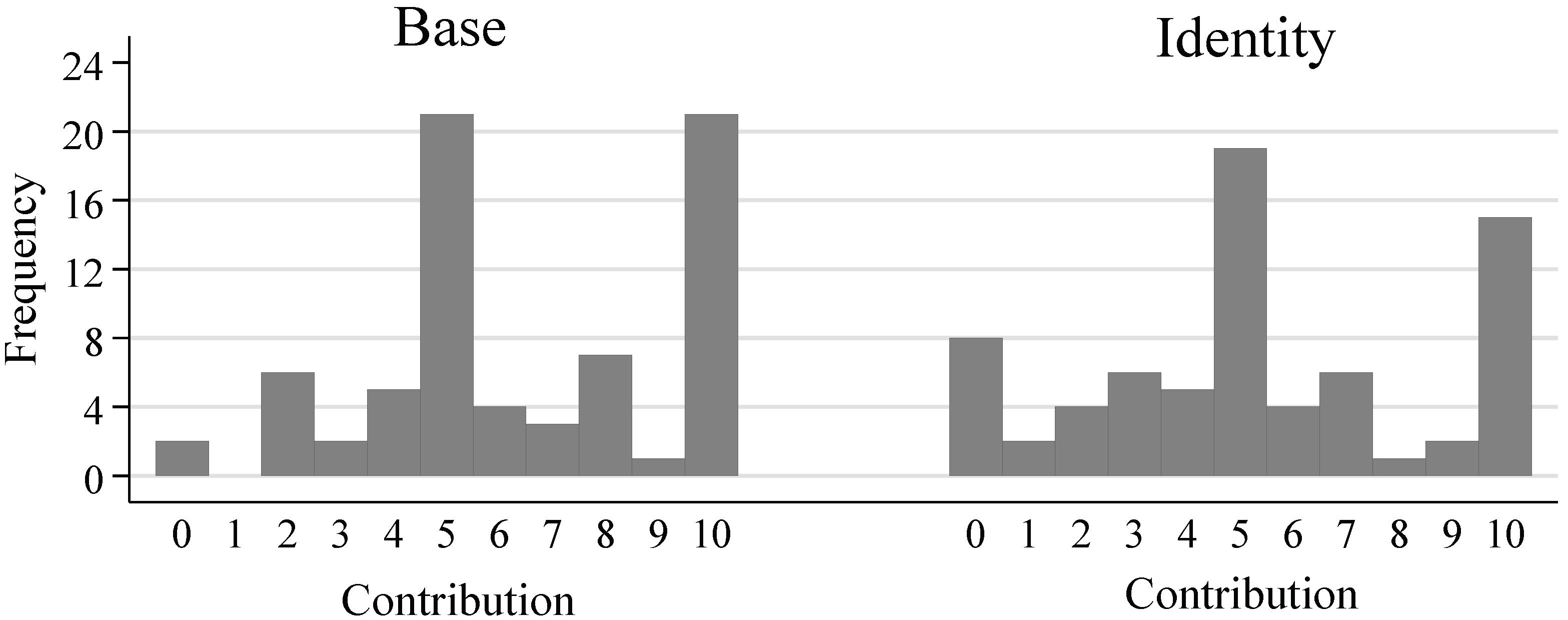

3.1. Contribution Decisions

3.2. Allocation Decisions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

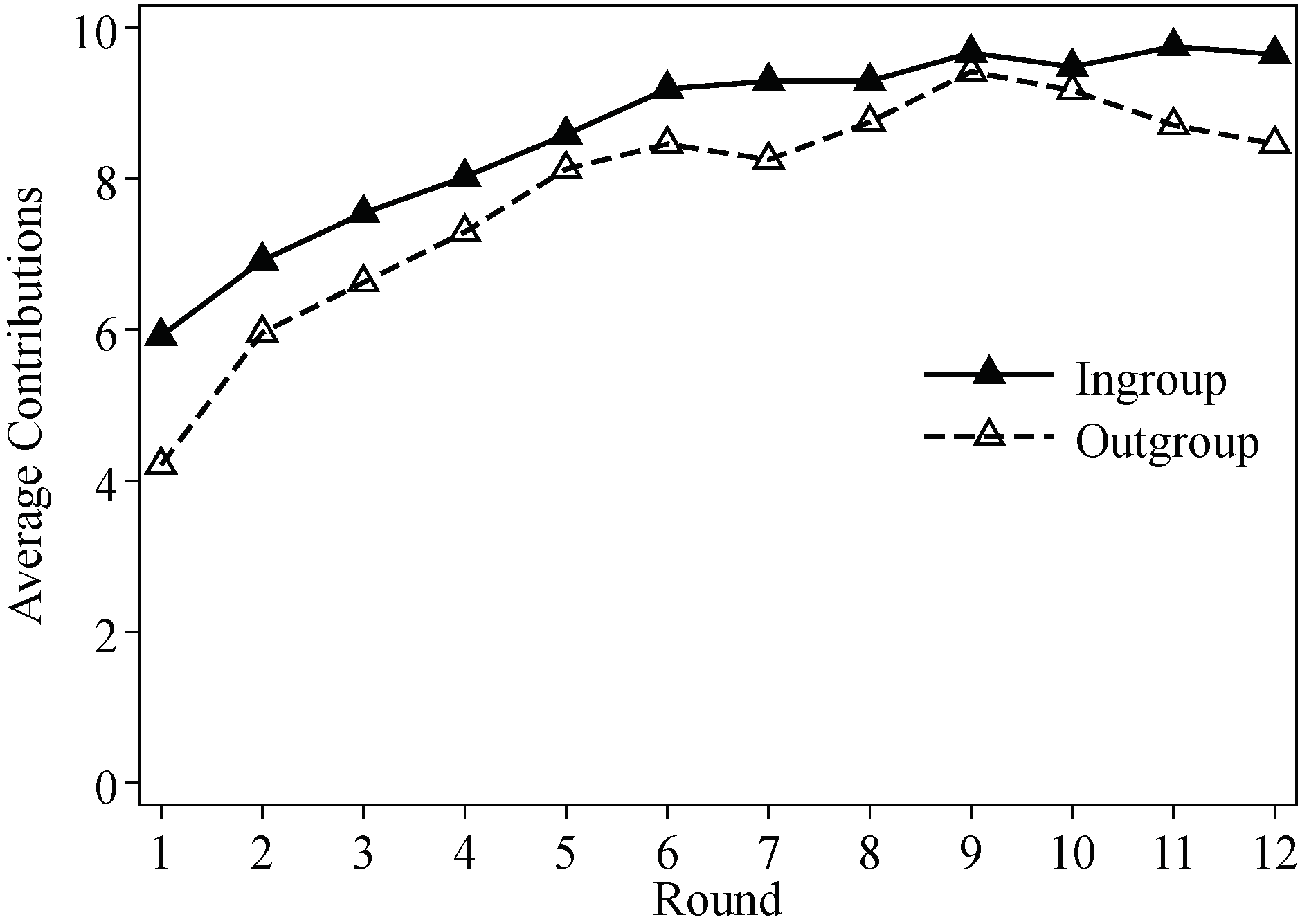

Appendix A. Experiment Instructions

Appendix A.1. Part 1

Appendix A.2. Part 2

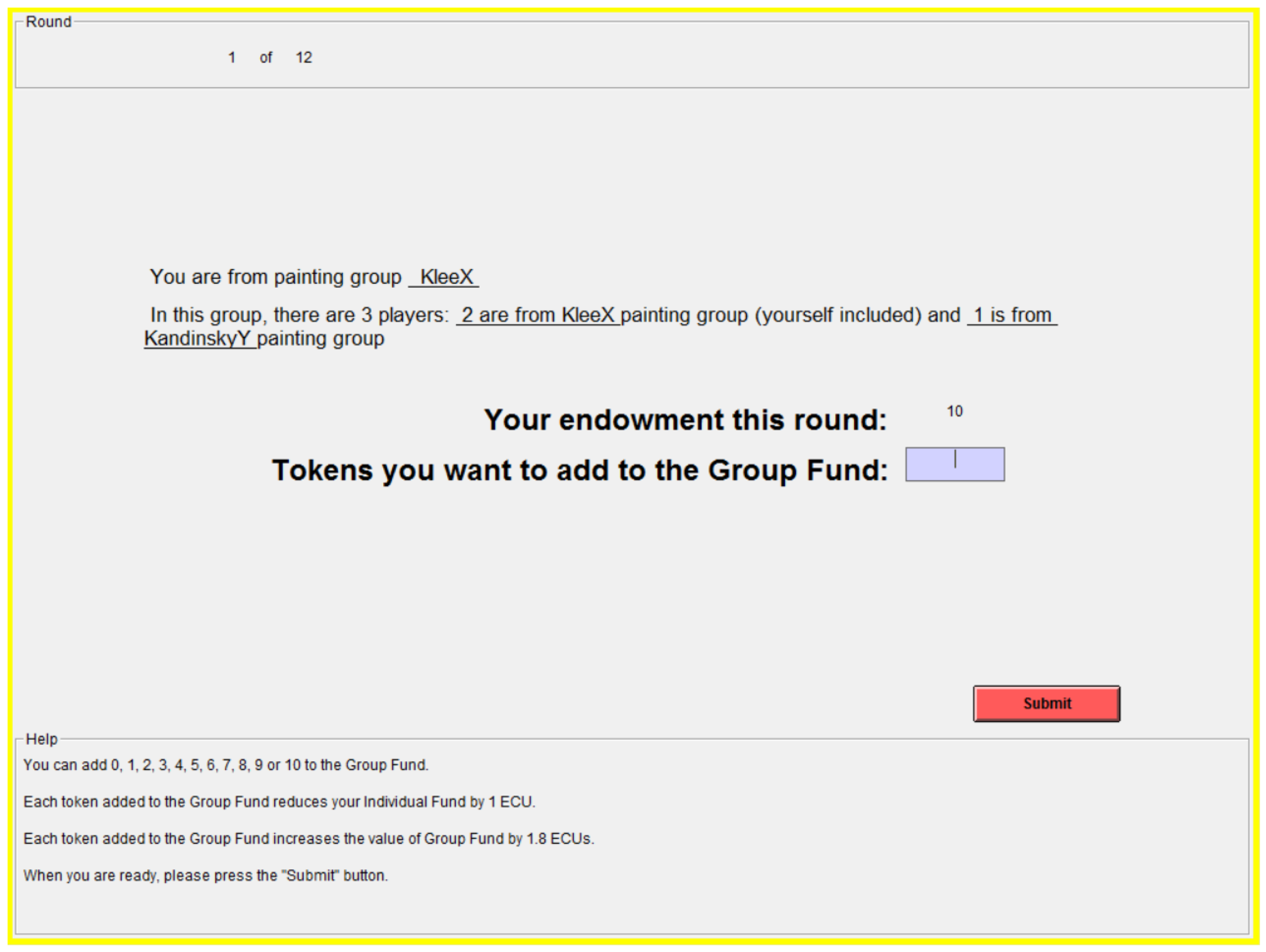

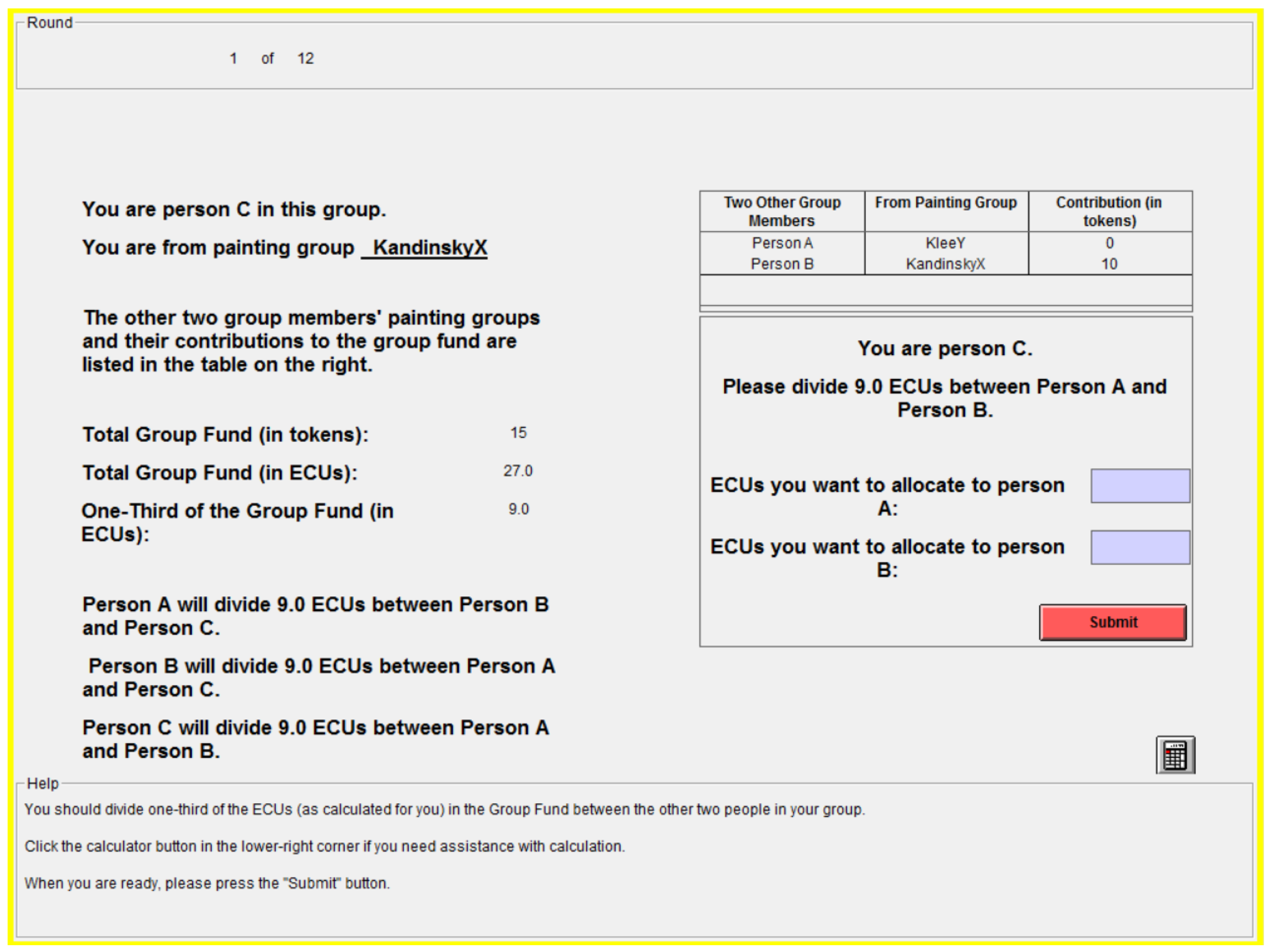

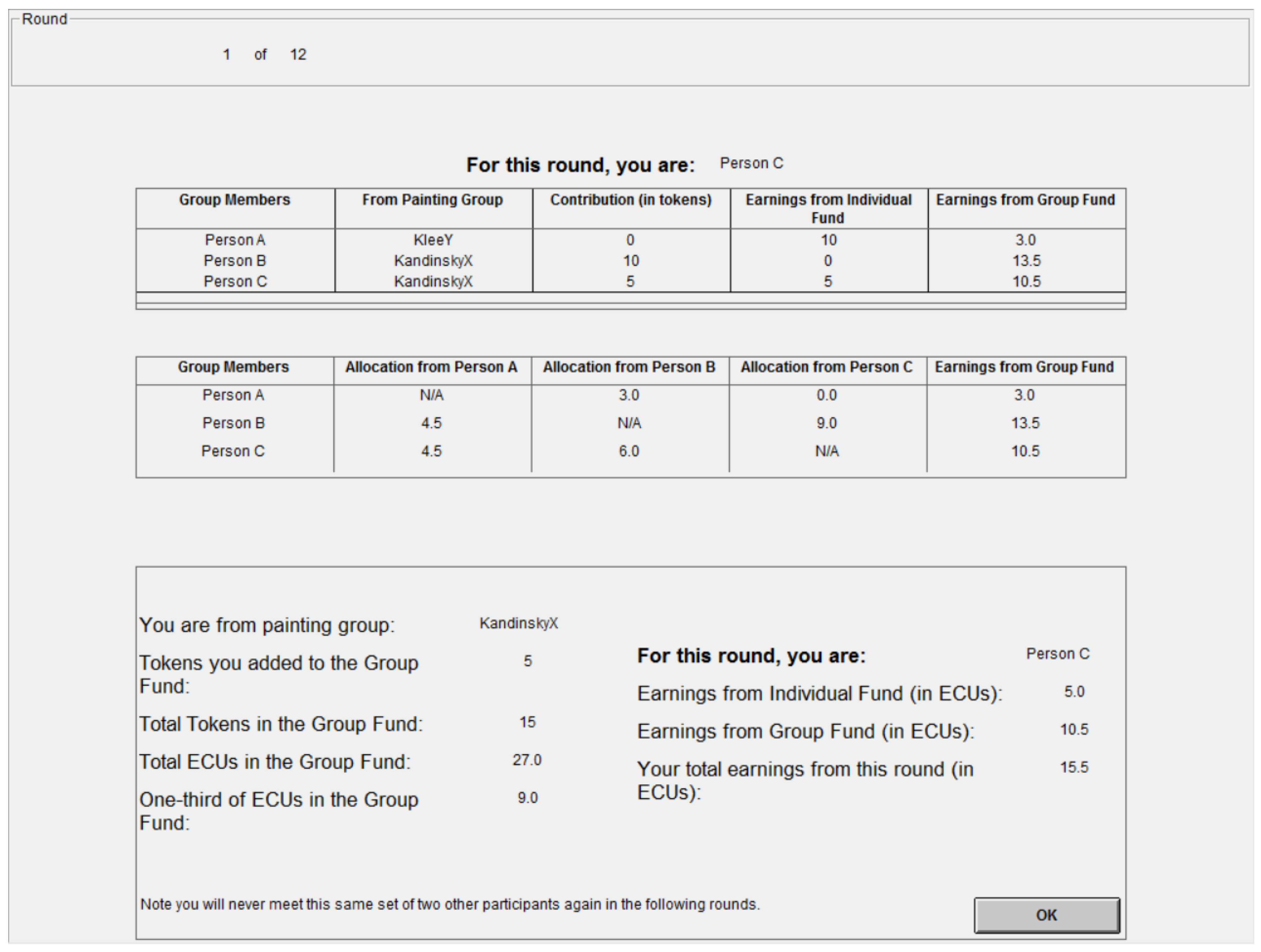

Appendix A.3. Screenshots

References

- Tajfel, H.; Billig, M.G.; Bundy, R.P.; Flament, C. Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 1, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, S. Group Identity and Social Preferences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 2005, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, H.; Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. Group Affiliation and Altruistic Norm Enforcement. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves Heap, S.P.; Zizzo, D.J. The Value of Groups. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 295–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Rigotti, L.; Rustichini, A. Individual Behavior and Group Membership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 1340–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, T. Discrimination in the laboratory: A meta-analysis of economics experiments. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 90, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.; Herrmann, B.; Kontoleon, A.; Newton, J. Is It A Norm To Favour Your Own Group? Exp. Econ. 2015, 18, 491–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity In Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Selten, R. The equity principle in economic behavior. In Decision Theory and Social Ethics; Gottinger, H., Leinfellner, W., Eds.; Issues in Social Choice; D. Reidel: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen, A.W.; Hole, A.D.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B. The Pluralism of Fairness Ideals: An Experimental Approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Falvey, R.; Luckraz, S. Fair Share and Social Efficiency: A Mechanism in Which Peers Decide on the Payoff Division. 2018. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2812658 (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Konow, J. Fair Shares: Accountability and Cognitive Dissonance in Allocation Decisions. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, A. Voluntary Contributions and Collective Redistribution. Am. Econ. J. Microecon. 2016, 8, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A.W.; Konow, J.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B. Just Luck: An Experimental Study of Risk-Taking and Fairness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 1398–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goette, L.; Huffman, D.; Meier, S. The Impact of Group Membership on Cooperation and Norm Enforcement: Evidence Using Random Assignment to Real Social Groups. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity, and Competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M. Equity, Equality, and Need: What Determines Which Value Will be Used as the Basis of Distributive Justice? J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, B.; Dorr, N.; Charlton, K.; Hume, D. Status differences and in-group bias: A meta-analytic examination of the effects of status stability, status legitimacy, and group permeability. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 520–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebe, U.; Naumann, E.; Tutic, A. Sozialer Status und prosoziales Handeln: Ein Quasi-Experiment im Krankenhaus. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 2017, 69, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetzel, F.; Sausgruber, R. Cognitive Ability and In-group Bias: An Experimental Study. J. Public Econ. in press. [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. Z-Tree: Zurich Toolbox For Ready-made Economic Experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B. Subject Pool Recruitment Procedures: Organizing Experiments with ORSEE. J. Econ. Sci. Assoc. 2015, 1, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, S.G.; Hanushek, E.A.; Kain, J.F. Teachers, Schools, and Academic Achievement. Econometrica 2005, 73, 417–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, J.; Salamanca, N.; Hamermesh, D.S. Endophilia or Exophobia: Beyond Discrimination. Econ. J. 2016, 126, 1503–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Miano, A.; Stantcheva, S. Immigration and Redistribution; NBER Working Paper 24733; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naumann, E.; Stoetzer, L.F. Immigration and support for redistribution: Survey experiments in three European countries. West Eur. Polit. 2018, 41, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | A large body of experimental literature has shown that the induced identities in the laboratory can have profound impacts on human behavior, including distributive behavior (Chen and Li, 2009) [2], punishment behavior (Bernhard, Fehr and Fischbacher, 2006 [3]), trusting behavior (Hargreaves Heap and Zizzo, 2009 [4]), cooperation in the Prisoner’s Dilemma and aggression in the Battles of Sexes (Charness, Rigotti and Rustichini, 2007 [5]), to name just a few. They typically find people tend to favor ingroups at the cost of outgroups, though the strength of ingroup favoritism varies in specific studies. See Lane (2016) [6] for a recent meta analysis. |

| 2. | In addition to experimental evidence, various theories have been put forward to discuss the conditions under which one norm is a more appropriate basis of distributive justice than the other. See economic models of outcome-based fairness and inequality aversion (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999 [16]; Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000 [17]) and discussions by social psychologists (e.g., Deutsch, 1975 [18]). |

| 3. | This line of research predominantly uses the other-other allocation task, varying social status or other social identities of allocators and recipients, to detect ingroup bias. However, status or identities may not be a strong enough cause for ingroup bias in the presence of self-interest motivation, that is, when players are allocating between themselves and other individuals (Liebe et al., 2017 [20]). |

| 4. | The matching of the three-person group was pre-determined by the computer software, and the software also randomizes the display of players’ contribution decisions on the screen in each round. In this way, players were not be able to track whom they had been previously paired with. |

| 5. | All the paintings were shown on the computer screen as well as in printed form. The five pairs of paintings are: 1A Gebirgsbidung, 1924, by Klee; 1B Subdued Glow, 1928, by Kandinsky; 2A Dreamy Improvisation, 1913, by Kandinsky; 2B Warning of the Ships, 1917, by Klee; 3A Dry-Cool Garden, 1921, by Klee; 3B Landscape with Red Splashes I, 1913, by Kandinsky; 4A Gentle Ascent, 1934, by Kandinsky; 4B Hoffmannesque Tale, 1921, by Klee; 5A Development in Brown, 1933, by Kandinsky; 5B The Vase, 1938, by Klee. |

| 6. | Our procedure differed from [2] in two ways. First, instead of a binary choice, we gave players four options: strongly prefer A, weakly prefer A, weakly prefer B, or strongly prefer B. Second, to ensure each painting group has an equal number, players were notified that their group assignment was based on their painting preferences relative to other players’ preferences in the room. So players were not necessarily placed in the group for which they had expressed stronger preferences, but selecting a greater number of painting by a given artist and indicating “strongly prefer” the paintings from that artist increased the probability of being in that group. |

| 7. | Painting number 6 is Monument in Fertile Country, 1929, by Klee, and Painting number 7 is Start, 1928, by Kandinsky. |

| 8. | The 12 copies of the paintings were also on their desk for the reference during the chat. A participant was neither required to contribute to the discussion nor to give answers that conformed any decision reached by the group. |

| 9. | In Dong et al. (2018) [11], the game is preceded by ten rounds of another game in which players alway received equal shares of the group profit. There, the average contribution reached almost zero in round ten. In their study, the two-stage mechanism helped to restore the contribution to the average of 8.0 in the next ten rounds. Using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of equality of distribution for last round contribution decisions, we find that the contribution level in our Base treatment is not significantly different from theirs (). |

| 10. | In the paper, we take sessions’ average contribution as independent observations when conducting ranksum tests, and we report two-sided p-values. |

| 11. | In the paper, we take sessions’ average contribution for the ingroups and outgroups as independent observations when conducting signed-rank tests, and we report two-sided p-values. |

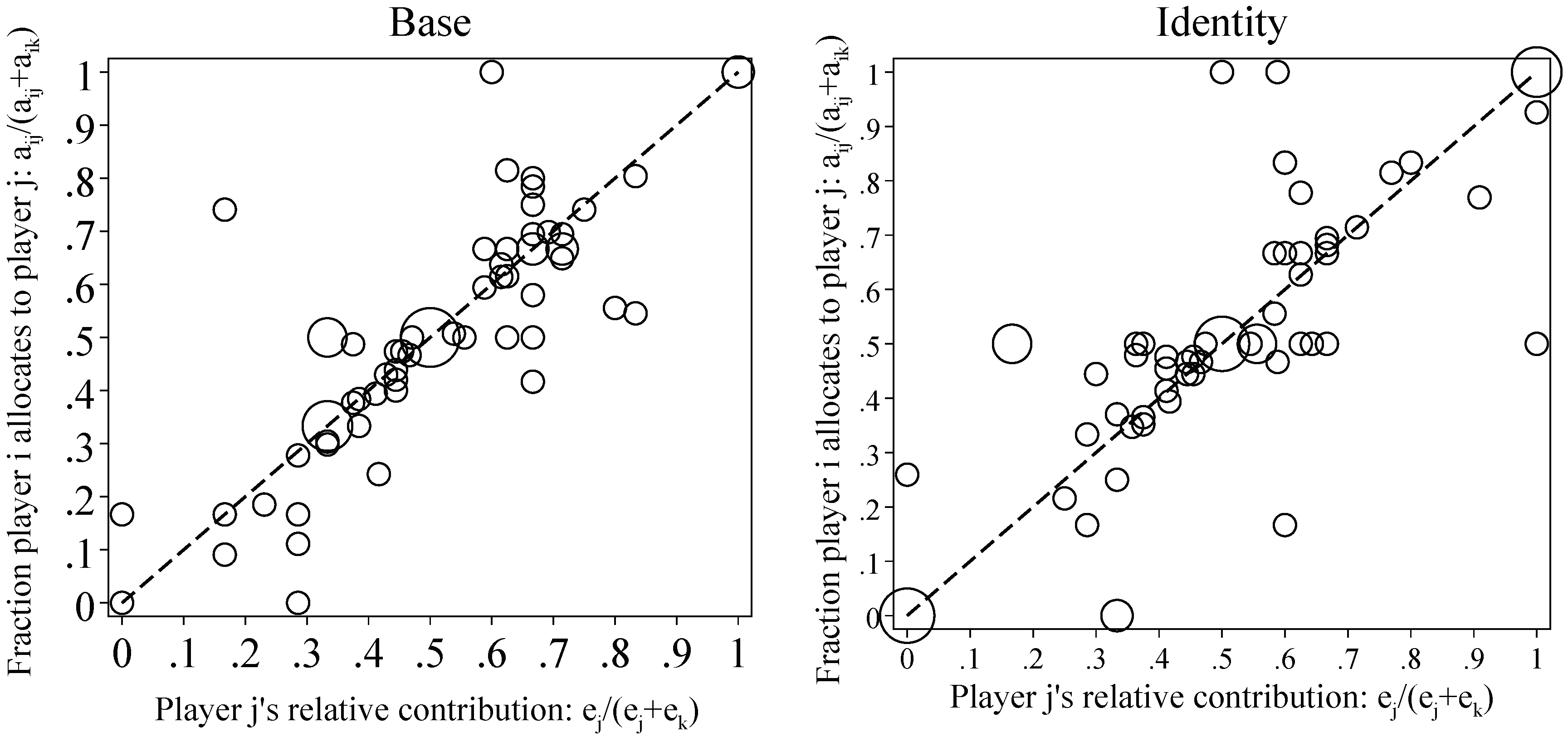

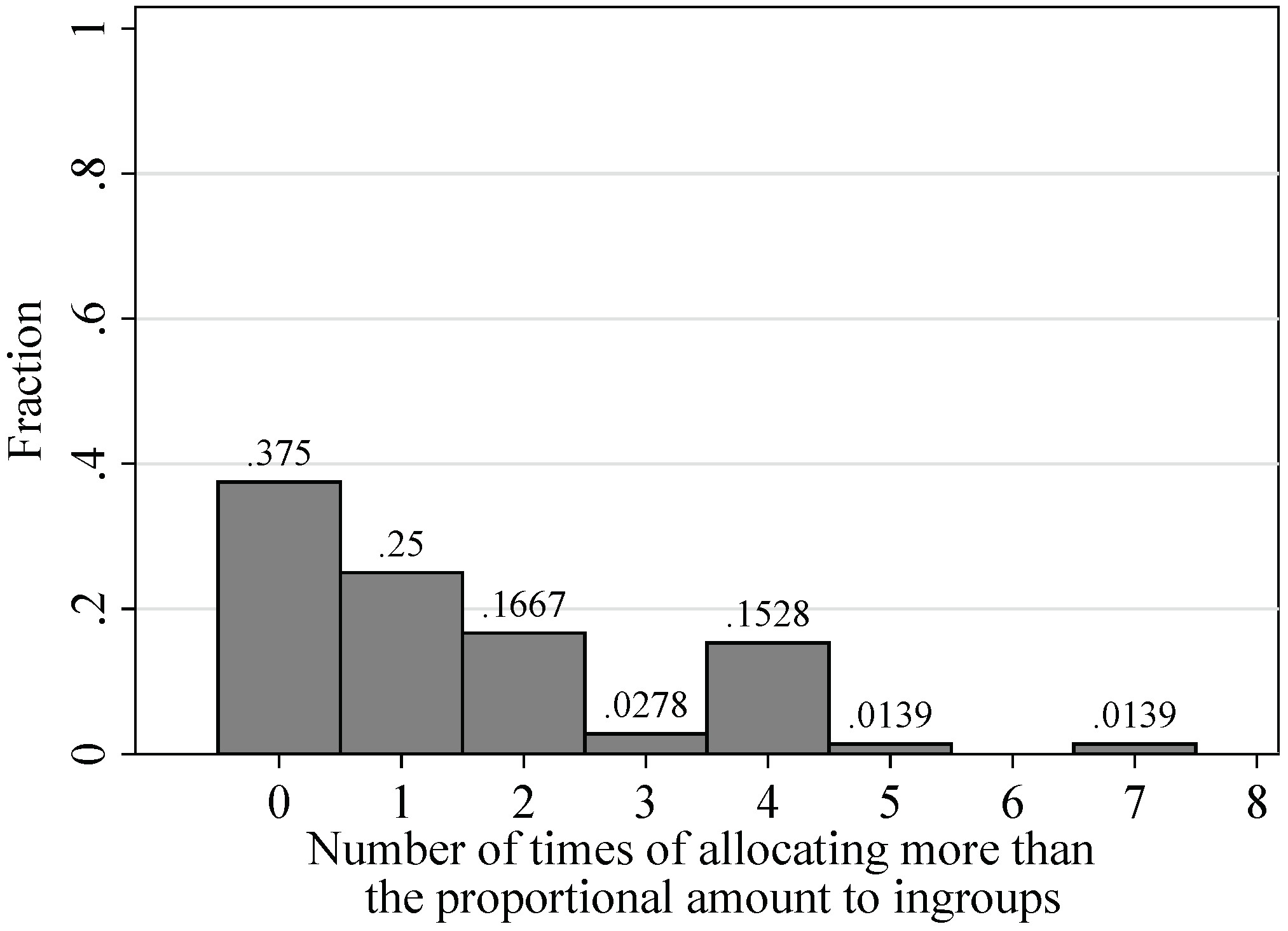

| 12. | Because our software only allows the input with a resolution of 0.1 and may not always be a fraction of ten, we define that player i allocates proportionally if . |

| 13. | In Figure 4, we demonstrate using the first round’s data because observations in later rounds are overwhelmingly full contribution and equal allocation. |

| 14. | A power analysis shows that to achieve the 80 percent power and 5 percent significance level for at least one of the ingroup dummy and interaction term (that is, ingroup dummy in the regression using all rounds), the required sample size is 4221. This means our study might be underpowered to detect the treatment difference in allocation decisions. Alternatively, it means that the effect is probably negligible to make any economic significance. |

| 15. | Unsurprisingly, the outgroups’ allocation decisions also strongly adhere to the proportional rule. |

| Round | Base | Identity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prop | Equal | P&E | Other | Prop | Equal | P&E | Other | |

| 1 | 46 | 14 | 7 | 20 | 42 | 20 | 6 | 18 |

| 2 | 51 | 22 | 18 | 17 | 52 | 26 | 18 | 14 |

| 3 | 49 | 23 | 18 | 19 | 51 | 26 | 21 | 17 |

| 4 | 59 | 29 | 26 | 11 | 53 | 29 | 21 | 15 |

| 5 | 59 | 29 | 28 | 13 | 53 | 32 | 24 | 15 |

| 6 | 56 | 32 | 31 | 16 | 53 | 36 | 33 | 16 |

| 7 | 61 | 40 | 40 | 11 | 60 | 35 | 35 | 12 |

| 8 | 65 | 50 | 49 | 6 | 59 | 44 | 44 | 13 |

| 9 | 68 | 51 | 50 | 4 | 51 | 45 | 42 | 19 |

| 10 | 68 | 61 | 61 | 4 | 58 | 43 | 42 | 14 |

| 11 | 67 | 60 | 60 | 5 | 58 | 38 | 37 | 14 |

| 12 | 67 | 62 | 62 | 5 | 61 | 44 | 43 | 11 |

| Dep. Variable: | Fraction Player i Allocate to Player j | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | All Rounds | |

| : Player j’s relative contribution | 0.877 *** | 0.971 *** |

| (0.064) | (0.040) | |

| : Player i and j are ingroups | 0.001 | 0.085 |

| (0.056) | (0.052) | |

| : j’s relative contribution × Ingroups | 0.037 | −0.078 |

| (0.080) | (0.063) | |

| : Intercept | 0.061 | 0.006 |

| (0.030) | (0.020) | |

| #Cluster | 6 | 12 |

| #Observations | 120 | 1440 |

| 3.68 | 0.55 | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Huang, L. Favoritism and Fairness in Teams. Games 2018, 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030065

Dong L, Huang L. Favoritism and Fairness in Teams. Games. 2018; 9(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Lu, and Lingbo Huang. 2018. "Favoritism and Fairness in Teams" Games 9, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030065

APA StyleDong, L., & Huang, L. (2018). Favoritism and Fairness in Teams. Games, 9(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030065