The Effects of Social Exclusion and Group Heterogeneity on the Provision of Public Goods

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Does Exclusion Reduce Pro-Sociality?

1.2. Does Inequality Affect Public Goods Provision?

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Stage One: Prisoner’s Dilemma Games

2.2. Stage Two: Public Goods Game

3. Experimental Protocol

4. Results

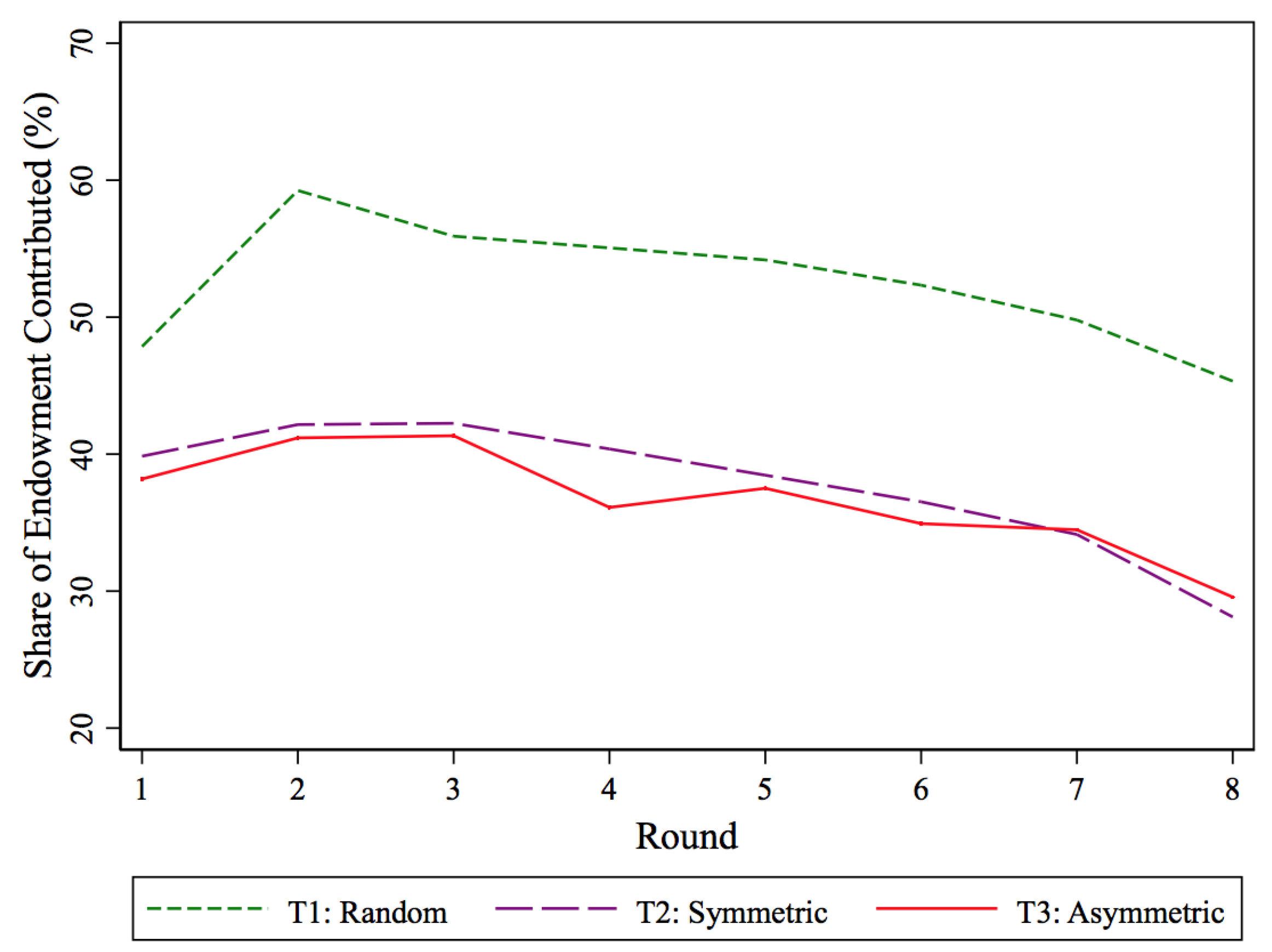

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

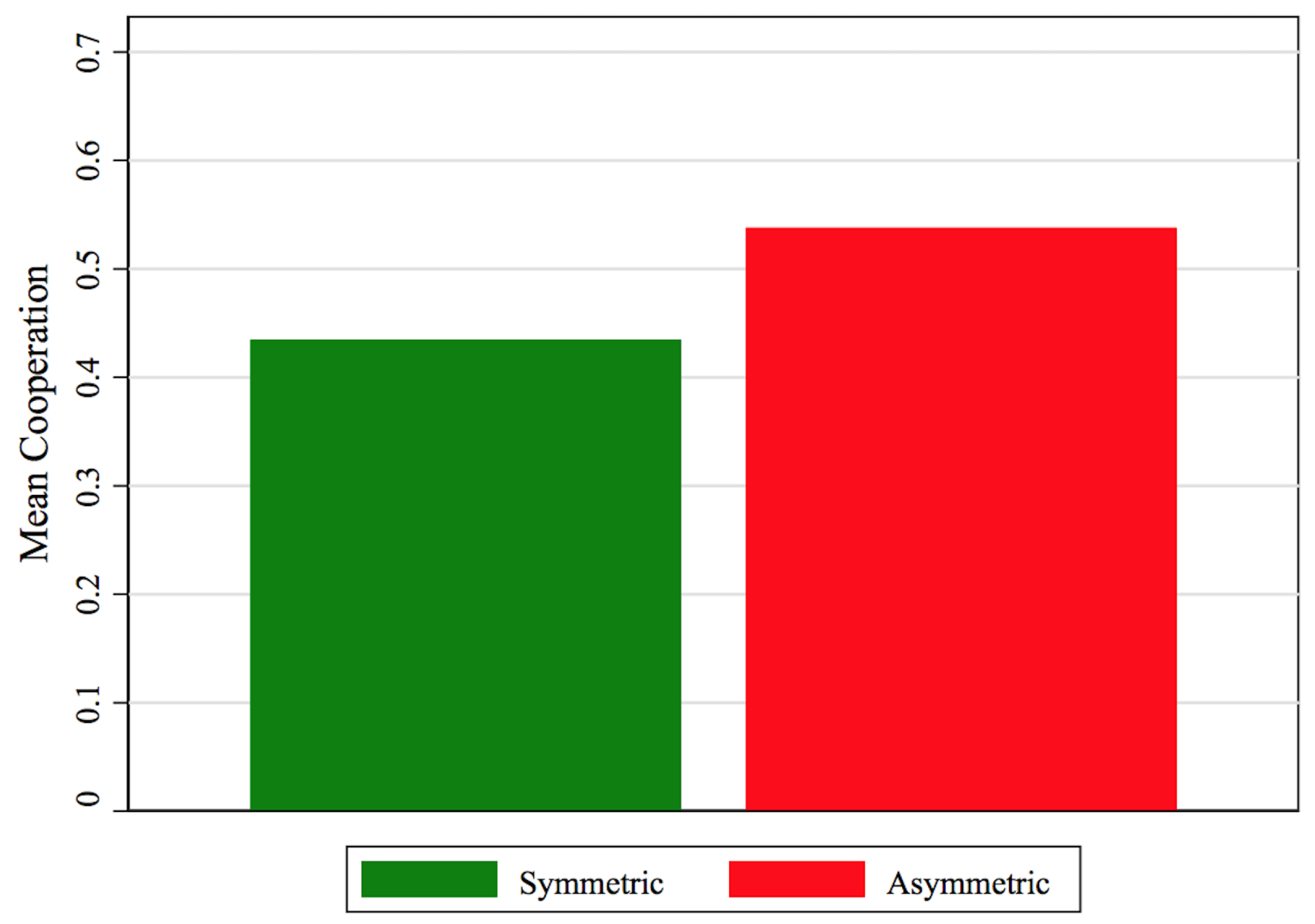

4.2. The Effects of Asymmetries in Personal Agency on Cooperation

4.3. The Effects of Wealth and the Origins of Inequality

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2: Symmetric | −14.40 *** | −15.63 *** | −4.13 | |

| (4.03) | (4.16) | (9.80) | ||

| T3: Asymmetric | −11.11 *** | −12.11 *** | −20.37 ** | |

| (3.74) | (3.93) | (10.01) | ||

| Endowment | −0.44 *** | −0.47 *** | −0.41 * | |

| (0.16) | (0.17) | (0.24) | ||

| Round | −1.24 *** | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** | |

| (0.31) | (0.35) | (0.35) | ||

| Group Endowment | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 | |

| (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.07) | ||

| Don’t trust strangers | −6.73 * | −7.91 ** | −8.15 ** | |

| (3.84) | (3.95) | (3.90) | ||

| Female | −6.19 ** | −5.70 * | −5.95 * | |

| (3.11) | (3.25) | (3.21) | ||

| White | 11.15 * | 11.39 | 9.63 | |

| (6.68) | (7.10) | (7.24) | ||

| Coloured | 8.61 * | 8.74 * | 7.84 | |

| (4.63) | (4.83) | (4.89) | ||

| Indian/Asian | −3.54 | −4.51 | −4.79 | |

| (7.90) | (8.35) | (8.24) | ||

| Registered for Game Theory | −10.77 ** | −9.89 ** | −11.02 ** | |

| (4.50) | (4.67) | (4.62) | ||

| Endowment in T2 | - | - | −0.48 | |

| (0.31) | ||||

| Endowment in T3 | - | - | 0.31 | |

| (0.35) | ||||

| Constant | 75.08 *** | 82.75 *** | 82.48 *** | |

| (8.63) | (8.84) | (9.33) | ||

| Observations | 2096 | 1834 | 1834 | |

| R-squared | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Variables | OLS (1) | OLS (2) | Group Fixed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socially Excluded | −15.04 *** | −23.08 ** | −18.22 * |

| (4.79) | (10.53) | (10.66) | |

| Endowment | −0.62 *** | −0.67 *** | −0.63 *** |

| (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.16) | |

| Endowment and socially excluded | - | 0.38 | 0.53 |

| (0.45) | (0.37) | ||

| Round | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** |

| (0.35) | (0.35) | (0.35) | |

| Don’t trust strangers | −7.85 ** | −8.09 ** | −10.68 *** |

| (3.92) | (3.93) | (3.17) | |

| Female | −5.60 * | −5.59 * | 1.03 |

| (3.26) | (3.25) | (2.51) | |

| White | 12.58 * | 12.19 * | 12.75 ** |

| (7.27) | (7.29) | (5.24) | |

| Coloured | 9.63 * | 8.65 * | 0.01 |

| (4.93) | (5.15) | (4.10) | |

| Indian/Asian | −4.01 | −4.08 | −10.75 * |

| (8.31) | (8.35) | (6.35) | |

| Registered for Game Theory | −11.17 ** | −11.37 ** | −10.72 *** |

| (4.62) | (4.65) | (3.47) | |

| Constant | 71.50 *** | 72.04 *** | 74.50 *** |

| (13.03) | (12.93) | (7.67) | |

| Observations | 1834 | 1834 | 1834 |

| R-squared | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| Decision | Variables | T1: Random | T2: Symmetric | T3: Asymmetric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | Fifteen tokens | −2.19 | −8.72 | - |

| (8.06) | (10.36) | |||

| CC | Thirty tokens | −4.38 | −17.20 * | −3.32 |

| (7.85) | (10.08) | (8.88) | ||

| DC | Forty tokens | −4.53 | −35.01 *** | −1.92 |

| (8.41) | (10.60) | (11.12) | ||

| Round | −2.09 *** | −2.17 *** | −1.79 *** | |

| (0.65) | (0.54) | (0.62) | ||

| Group endowment | −0.27 ** | 0.04 | −0.08 | |

| (0.11) | (0.15) | (0.14) | ||

| Don’t trust strangers | −2.16 | −10.53 | −15.10 ** | |

| (6.32) | (8.96) | (7.29) | ||

| Female | 4.24 | −7.28 | −10.12 * | |

| (5.35) | (6.95) | (6.01) | ||

| White | 11.94 | −14.42 | 11.69 | |

| (10.64) | (10.75) | (10.40) | ||

| Coloured | 5.94 | 20.24 * | −0.31 | |

| (7.45) | (10.58) | (10.07) | ||

| Indian/Asian | −23.25 *** | 24.71 | −14.78 | |

| (8.17) | (17.43) | (16.73) | ||

| Registered for Game Theory | −2.38 | −22.09 ** | −10.65 | |

| (10.95) | (8.82) | (7.48) | ||

| Constant | 100.46 *** | 57.15 *** | 66.96 *** | |

| (17.66) | (18.60) | (14.45) | ||

| Observations | 651 | 574 | 609 | |

| R-squared | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

References

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rispel, L.C.; Molomo, B.; Dumela, S. South African Case Study on Social Exclusion; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, J.B.; Leider, S. Procedural fairness and the cost of control. J. Law Econ. Organ. 2016, 32, 685–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Folger, R. Referent cognitions and task decision autonomy: Beyond equity theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Reactions to procedural injustice in payment distributions: Do the means justify the ends? J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, E.; Stallen, P.J.; Vermunt, R.; Steensma, H. Evaluating noise in social context: The effect of procedural unfairness on noise annoyance judgments. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2007, 122, 3483–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folger, R.; Martin, C. Relative deprivation and referent cognitions: Distributive and procedural justice effects. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Does Strategy Fairness Make Inequality more Acceptable? Technical Report; School of Economics, University of East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelo, N.; Croson, R.T.; Li, S.X. Identity and social exclusion: An experiment with Hispanic immigrants in the US. Exp. Econ. 2017, 20, 460–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, P.; Abrams, D.; Christian, J. The social psychology of exclusion. In Multidisciplinary Handbook of Social Exclusion Research; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007; pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; Tice, D.M.; Stucke, T.S. If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabin, M. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 1281–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Güroğlu, B.; van den Bos, W.; Crone, E.A. Fairness considerations: Increasing understanding of intentionality during adolescence. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2009, 104, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, M. Outcomes versus intentions: On the nature of fair behavior and its development with age. J. Econ. Psychol. 2007, 28, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridinger, G. Intentions Versus Outcomes: Cooperation and Fairness in a Sequential Prisoner’s Dilemma with Nature. 2016. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2841833 (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Falk, A.; Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. On the nature of fair behavior. Econ. Inq. 2003, 41, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.; Thaler, R.H. Anomalies: Ultimatums, dictators and manners. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V.L. Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, R.; Horowitz, J.L.; Savin, N.E.; Sefton, M. Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R.H. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. J. Bus. 1986, 59, S285–S300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Weber, R.A.; Kuang, J.X. Exploiting moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory 2007, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, R.; Vorsatz, M. What behaviors are disapproved? Experimental evidence from five dictator games. Games 2012, 3, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, P.J.; Knack, S. Trust and growth. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, J.; Dhaene, G. Inter-ethnic trust and reciprocity: Results of an experiment with small businessmen. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2004, 20, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. Social distance and social decisions. Econometrica 1997, 65, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, S.; Keefer, P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 1251–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varughese, G.; Ostrom, E. The contested role of heterogeneity in collective action: Some evidence from community forestry in Nepal. World Dev. 2001, 29, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C. Foundations of Social Theory; Belknap: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Messick, D.M.; Brewer, M.B. Solving Social Dilemmas; A Review. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; La Ferrara, E. Participation in Heterogeneous Communities. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 847–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P. Analytics of the institutions of informal cooperation in rural development. World Dev. 1993, 21, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, P. Irrigation and cooperation: An empirical analysis of 48 irrigation communities in South India. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2000, 48, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton-Johnson, J. Determinants of collective action on the local commons: A model with evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2000, 62, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Drazen, A. Why are Stabilizations Delayed? Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 1170–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Fellner, G.; Iida, Y.; Kröger, S.; Seki, E. Heterogeneous Productivity in Voluntary Public Good Provision: An Experimental Analysis; IZA Discussion Paper No. 5556; Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.; Isaac, R.M.; Schatzberg, J.W.; Walker, J.M. Heterogenous demand for public goods: Behavior in the voluntary contributions mechanism. Public Choice 1995, 85, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.R.; Mellor, J.M.; Milyo, J. Inequality and public good provision: An experimental analysis. J. Soc.-Econ. 2008, 37, 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, J.C. Real wealth and experimental cooperation: Experiments in the field lab. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 70, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U.; Schudy, S.; Teyssier, S. Heterogeneous Reactions to Heterogeneity in Returns from Public Goods. Soc. Choice Welf. 2014, 43, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, A.; Burns, J.; Visser, M. Income Inequality, Reciprocity and Public Good Provision: An Experimental Analysis. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2007, 75, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, T.L.; Kroll, S.; Shogren, J.F. The Impact of Endowment Heterogeneity and Origin on Public Good Contributions: Evidence From the Lab. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 57, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, S.; Cherry, T.L.; Shogren, J.F. The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on contributions in best-shot public good games. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledyard, J. Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zelmer, J. Linear Public Goods Experiments: A Meta-Analysis. Exp. Econ. 2003, 6, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A. Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: A selective survey of the literature. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 47–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwell, G.; Ames, R. Experiments on the Provision of Public Goods. I. Resources, Interest, Group Size, and the Free-Rider Problem. Am. J. Sociol. 1979, 84, 1135–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Visser, M. Income Inequality and the Provision of Public Goods: When the Real World Mimics the Lab. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/ybaptzz4 (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- Georgantzıs, N.; Proestakis, A. Accounting for Real Wealth in Heterogeneous-Endowment Public Good Games; ThE Papers 10/20; Department of Economic Theory and Economic History of the University of Granada: Granada, Spain, 2011; Volume 10, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Heap, S.P.H.; Ramalingam, A.; Stoddard, B.V. Endowment inequality in public goods games: A re-examination. Econ. Lett. 2016, 146, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, S.P.H.; Ramalingam, A.; Ramalingam, S.; Stoddard, B.V. Doggedness or disengagement? An experiment on the effect of inequality in endowment on behaviour in team competitions. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 120, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laver, M. Private Desires, Political Action: An Invitation to the Politics of Rational Choice; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Theory of Social Interactions. Source J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 1063–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | As we are interested in social exclusion primarily in the form of limitations to social participation and decision-making power, we will use “social exclusion” and “ability to exercise personal agency” interchangeably throughout. |

| 2. | In our experiment, being socially excluded means having one’s personal agency removed. In turn, this leaves the individual vulnerable to the actions of the other player, whose dominant strategy should be to defect, thereby generating material inequalities in the endowments in the subsequent public goods game. Individuals who find themselves in the position of having their agency removed, and subsequently being on the receiving end of disadvantageous inequality, may perceive the process that generated the endowments in the public goods game as being unfair. This is akin to procedural unfairness. |

| 3. | Exclusion is identified based on the identity of the participants in the study. The logic behind the identity-based identification strategy assumes that Hispanic Americans born in the Untied States experience more social inclusion than those born outside of America [11]. |

| 4. | |

| 5. | |

| 6. | The design of experiments in this field vary substantially in several features. In some cases, the endowments allocated to participants at the onset of the game are varied [43,44], the value of the public good to different individuals (the marginal per capita returns) is altered [38,42,49] or different show up fees for participation are awarded [40]. These are likely to be some of the contributing factors to the variety of results. |

| 7. | The term “asymmetric game” is sometimes used in the literature to describe a Prisoner’s Dilemma in which all possible payoffs are unequal. The game presented here differs crucially from this in that the asymmetry is in strategies and not in payoffs. The asymmetric strategy Prisoner’s Dilemma game is sometimes termed a Prisoner’s Non-Dilemma [15]. However, in some instances, a Prisoner’s Non-Dilemma refers to Prisoner’s Dilemma game in which the dominant strategy is also the socially optimal strategy [54]. Unfortunately, plurality in terminology cannot be avoided in achieving meaningful and concise descriptions of the games in this experiment. It is, therefore, important that the games described in this paper are read as asymmetric (symmetric) strategy Prisoner’s Dilemma games, even when this is not made explicit in-text. |

| 8. | The payoffs, for the entire experiment, are denoted in Experimental Currency Tokens with one token equal to half a South African rand, which is equivalent to roughly 0.1 United States dollars. The players were unaware of the conversion rate until the experimental session concluded, therefore these values cannot be used to assess salience or dominance. As the players were not aware of the South African rand equivalent of each token, the text will refer to payoffs exclusively in terms of Experimental Currency Units. |

| 9. | The sequential play of the Prisoner’s Dilemma game makes it possible that the symmetric game had an impact on the decisions made in the subsequent asymmetric game. Budget constraints made it impossible for us to test order effects with sufficient sample size. While order effects might exist, so long as the order effects operate in the same way across our different treatments, which we have no reason to question, the order of play does not undermine our final results. |

| 10. | As Treatment One had no prior play, the announcement to players of the game to be selected, thus the treatment the session would be allocated to, was only made in Treatment Two and Treatment Three. |

| 11. | The hourly student tutoring rate is approximately one hundred rand per hour. |

| 12. | Seating randomisation was done manually and participants observed this. All other randomisation in the experiment was computerised (which participants were also informed of) and implemented automatically as the experiment progressed. |

| 13. | Players were made aware of the asymmetries in strategies in the asymmetric game at the beginning of this game. |

| 14. | No other context was provided and references to words such as “contributions”, “public” or “private” were deliberately avoided. Two examples were used to ensure the participants understood the structure of the game. Both examples were constructed such that the mechanism of the VCM was identical to that of the experiment, while paying due consideration to the possibility of anchoring players to the choices described in the examples. In both examples, groups of four fixed players allocated shares of their endowments to Account A or Account B and all earned identical income from Account B. Both examples had homogeneous endowments of twenty tokens for each player. The choice of twenty tokens as the homogeneous endowment was made deliberately as an endowment of twenty tokens is not possible in the experiment. In Example One, all four players contributed their entire endowment to Account B while, in Example Two, all group members contributed zero tokens to the public account. Following the examples, the independence of each player’s contribution to those made by their fellow group members as well as the endowment heterogeneity in the experiment were reiterated to the participants. |

| 15. | The random stranger matching of the groups in the public goods game precludes behaviour motives such as retribution or reciprocity. |

| 16. | Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire online before arriving for the session. This pre-session questionnaire elicited perceptions of the general trustworthiness of people using the common trust question; “In general, would you say that most people can be trusted?” In addition, participants were asked to indicate, from a limited list, the economics courses for which they had enrolled for at the university. Participants who failed to complete the questionnaire online completed the questionnaire immediately before the session started. This data is used as controls in all regressions presented in the paper as well as an addition control for whether a participant completed the questionnaire online or at beginning of the session. |

| 17. | The total number of participants across rows in the table does not sum to the total number of participants in the sample as each row represents pairwise comparisons of the treatments and not all three treatments together. |

| 18. | South Africa has its own unique history of the social, economic and political exclusion of particular groups. While this is an important topic, we did not design this experiment to focus on real-world experiences of exclusion of our subjects. We did not prime identity in the experiment, nor did we deliberately recruit according to identity group markers, and so do not wish to make too much of the differential response of individuals from different race groups. However, given the importance of identity in the South African setting, in all of our analysis, we control for race in order to deal with any potential confounds in our treatment variables of interest. We do not specifically report them in the regressions in the paper, but do report them in the set of regressions reported in Appendix A. |

| 19. | The results remain robust to the inclusion of round one data. |

| 20. | See Table A1 for an expanded list of reported key explanatory variables. |

| 21. | Student t-test for differences in mean endowment between socially included and excluded participants in Treatment Three are based on the number of participants as endowments are earned once and consistent across the rounds of play. |

| 22. | The appropriateness of the fixed effects model, as opposed to a random effects alternative, is supported by Hausman test with Chi-squared statistic of 39.27 and p = 0.00. |

| 23. | See Table A2 for expanded list of key co-variates. |

| 24. | The combination of decisions in the Prisoners’ Dilemma which would lead to each player’s endowment are shown in the column headed "Decision" in Table 6. |

| 25. | Additional key controls are reported in Table A3. |

| Outcome | Symmetric Payoffs | Asymmetric Payoffs |

|---|---|---|

| DD | 15;15 | - |

| CD | 10;40 | - |

| DC | 40;10 | 40;10 |

| CC | 30;30 | 30;30 |

| Treatment: Endowment Origin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | All | T2: Symmetric | T1: Random | |

| Age in years | 22.57 | 23.02 | 21.88 | ** |

| Female | 0.376 | 0.375 | 0.37 | |

| Black African | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.61 | * |

| Coloured | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.19 | * |

| Indian/Asian | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | |

| White | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.09 | ** |

| Don’t trust strangers | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.61 | |

| Game Theory Course | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.09 | * |

| Participants | 292 | 88 | 108 | |

| Variables | All | T3: Asymmetric | T1: Random | |

| Age in years | 22.57 | 22.94 | 21.89 | * |

| Female | 0.376 | 0.44 | 0.37 | |

| Black African | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.61 | |

| Coloured | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.19 | |

| Indian/Asian | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | |

| White | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 | * |

| Don’t trust strangers | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.61 | |

| Game Theory Course | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.09 | *** |

| Participants | 292 | 96 | 108 | |

| Variables | All | T3: Aymmetric | T2: Symmetric | |

| Age in years | 22.57 | 22.94 | 23.023 | |

| Female | 0.376 | 0.44 | 0.38 | |

| Black African | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.73 | |

| Coloured | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.09 | *** |

| Indian/Asian | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| White | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Don’t trust strangers | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.66 | |

| Game Theory Course | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.18 | |

| Participants | 292 | 96 | 88 | |

| Treatment: Endowment Origin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | All | T1: Random | T2: Symmetric |

| Sum of group endowments | 101.44 | 101.67 | 91.36 |

| Gini Coefficient | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Endowment | 25.36 | 25.42 | 22.84 |

| Observations | 292 | 108 | 88 |

| All | T1: Random | T3: Asymmetric | |

| Sum of group endowments | 101.44 | 101.67 | 110.42 |

| Gini Coefficient | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| Endowment | 25.36 | 25.42 | 27.60 |

| Observations | 292 | 108 | 96 |

| All | T2: Symmetric | T3: Asymmetric | |

| Sum of group endowments | 101.44 | 91.36 | 110.42 |

| Gini Coefficient | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.17 *** |

| Endowment | 25.36 | 22.84 | 27.60 *** |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2: Symmetric | −14.40 *** | −15.63 *** | −4.13 |

| (4.03) | (4.16) | (9.80) | |

| T3: Asymmetric | −11.11 *** | −12.11 *** | −20.37 ** |

| (3.74) | (3.93) | (10.01) | |

| Endowment | −0.44 *** | −0.47 *** | −0.41 * |

| (0.16) | (0.17) | (0.24) | |

| Round | −1.24 *** | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** |

| (0.31) | (0.35) | (0.35) | |

| Group Endowment | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.06 |

| (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.07) | |

| Don’t trust strangers | −6.73 * | −7.91 ** | −8.15 ** |

| (3.84) | (3.95) | (3.90) | |

| Endowment in Symmetric (T2) | - | - | −0.48 |

| (0.31) | |||

| Endowment in Asymmetric (T3) | - | - | 0.31 |

| (0.35) | |||

| Constant | 75.08 *** | 82.75 *** | 82.48 *** |

| (8.63) | (8.84) | (9.33) | |

| Observations | 2096 | 1834 | 1834 |

| R-squared | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Socially Included | Socially Excluded | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment One: Random | |||

| Endowment | 25.42 | - | |

| Observations | 756 | 0 | |

| Participants | 108 | 0 | |

| Treatment Two: Symmetric | |||

| Endowment | 22.84 | - | |

| Observations | 616 | 0 | |

| Participants | 88 | 0 | |

| Treatment Three: Asymmetric | |||

| Endowment | 34.79 | 20.42 | *** |

| Observations | 336 | 336 | |

| Participants | 48 | 48 | |

| Variables | OLS (1) | OLS (2) | Group Fixed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socially Excluded | −15.04 *** | −23.08 ** | −18.22 * |

| (4.79) | (10.53) | (10.66) | |

| Endowment | −0.62 *** | −0.67 *** | −0.63 *** |

| (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.16) | |

| Endowment and socially excluded | - | 0.38 | 0.53 |

| (0.45) | (0.37) | ||

| Don’t trust strangers | −7.85 ** | −8.09 ** | −10.68 *** |

| (3.92) | (3.93) | (3.17) | |

| Round | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** | −2.01 *** |

| (0.35) | (0.35) | (0.35) | |

| Constant | 71.50 *** | 72.04 *** | 74.50 *** |

| (13.03) | (12.93) | (7.67) | |

| Observations | 1834 | 1834 | 1834 |

| R-squared | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| Decision | Variables | T1: Random | T2: Symmetric | T3: Asymmetric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD | Fifteen token endowment | −2.19 | −8.72 | - |

| (8.06) | (10.36) | |||

| CC | Thirty token endowment | −4.38 | −17.20 * | −3.32 |

| (7.85) | (10.08) | (8.88) | ||

| DC | Forty token endowment | −4.53 | −35.01 *** | −1.92 |

| (8.41) | (10.60) | (11.12) | ||

| Don’t trust strangers | −2.16 | −10.53 | −15.10 ** | |

| (6.32) | (8.96) | (7.29) | ||

| Round | −2.09 *** | −2.17 *** | −1.79 *** | |

| (0.65) | (0.54) | (0.62) | ||

| Observations | 651 | 574 | 609 | |

| R-squared | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Njozela, L.; Burns, J.; Langer, A. The Effects of Social Exclusion and Group Heterogeneity on the Provision of Public Goods. Games 2018, 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030055

Njozela L, Burns J, Langer A. The Effects of Social Exclusion and Group Heterogeneity on the Provision of Public Goods. Games. 2018; 9(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleNjozela, Lindokuhle, Justine Burns, and Arnim Langer. 2018. "The Effects of Social Exclusion and Group Heterogeneity on the Provision of Public Goods" Games 9, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030055

APA StyleNjozela, L., Burns, J., & Langer, A. (2018). The Effects of Social Exclusion and Group Heterogeneity on the Provision of Public Goods. Games, 9(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030055