Endogenous Game Choice and Giving Behavior in Distribution Games

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Experimental Design, Implementation, and Hypotheses

3.1. Experimental Design

3.2. Experimental Implementation

3.3. Hypotheses

3.4. Survey Design and Implementation

4. Analysis and Results

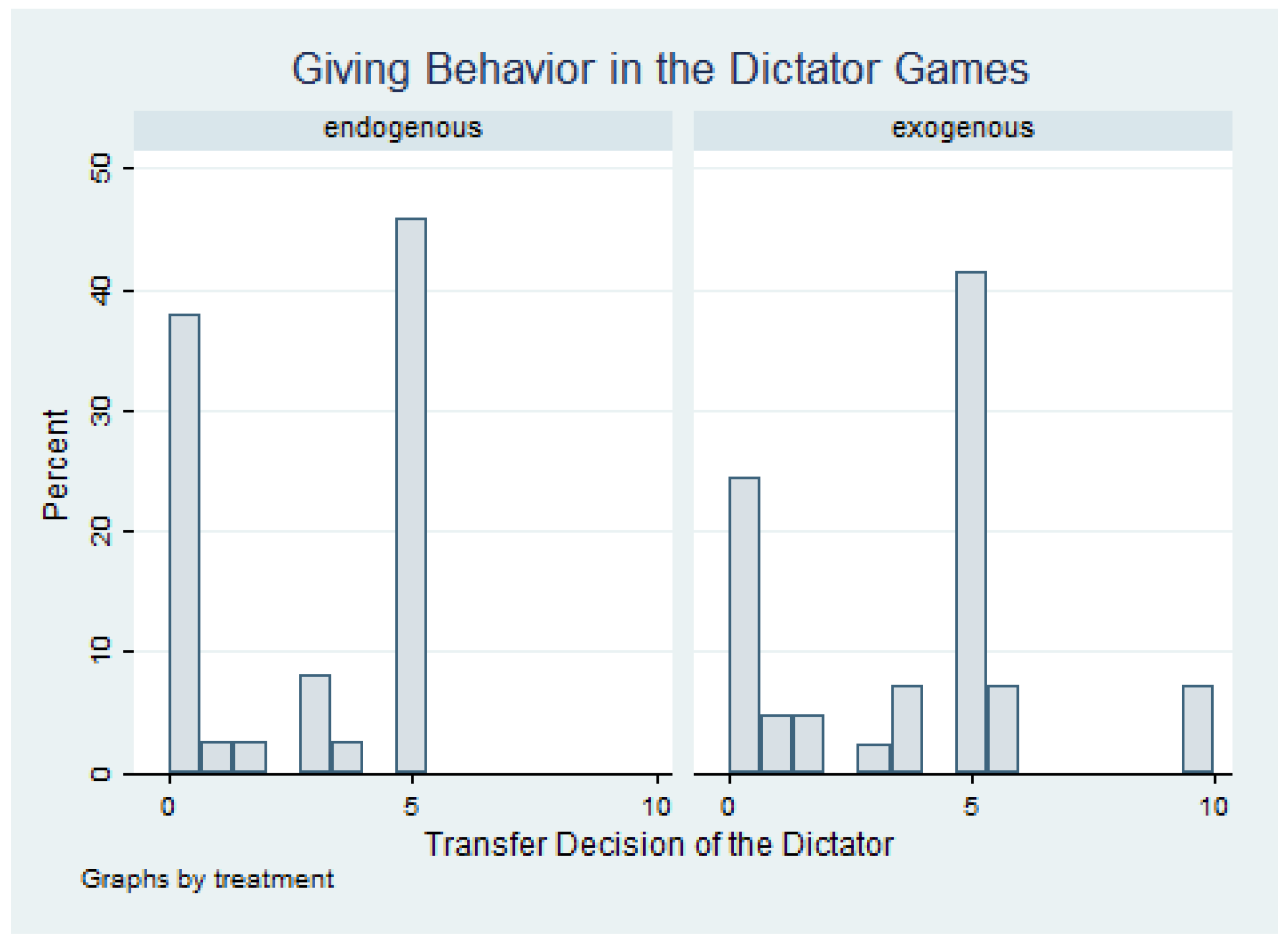

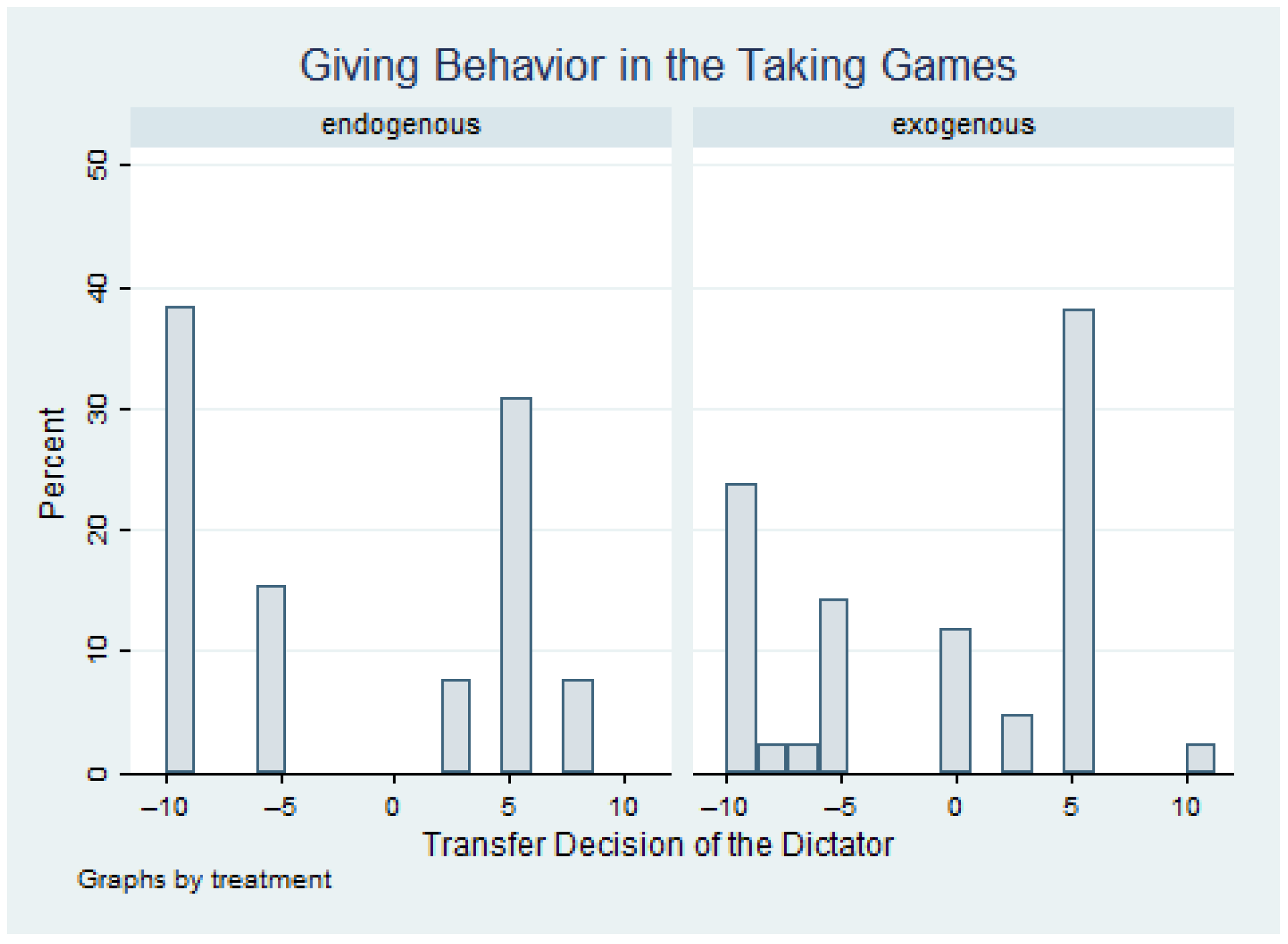

4.1. Main Experimental Results

4.1.1. Statistical Tests

4.1.2. Regression Analyses

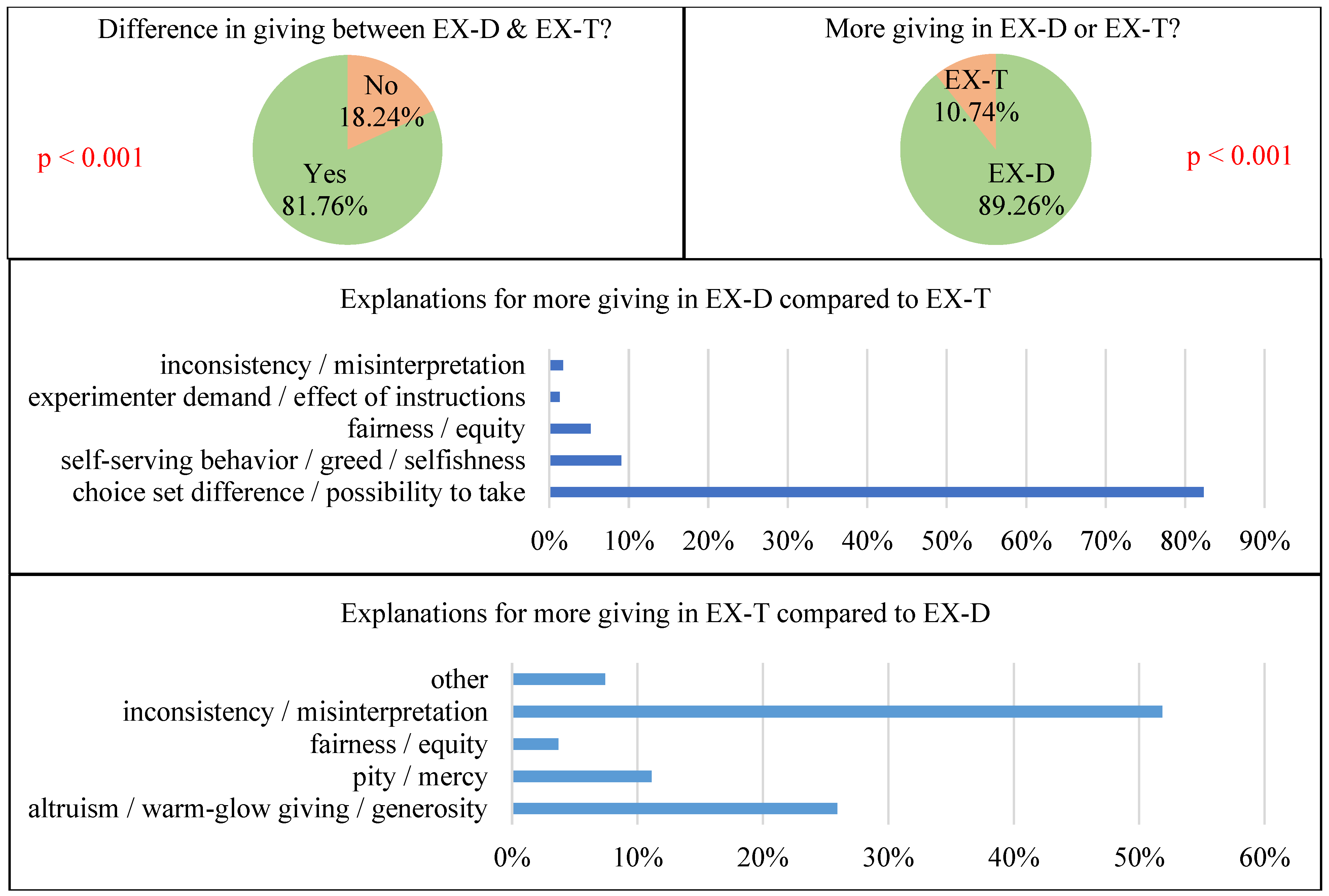

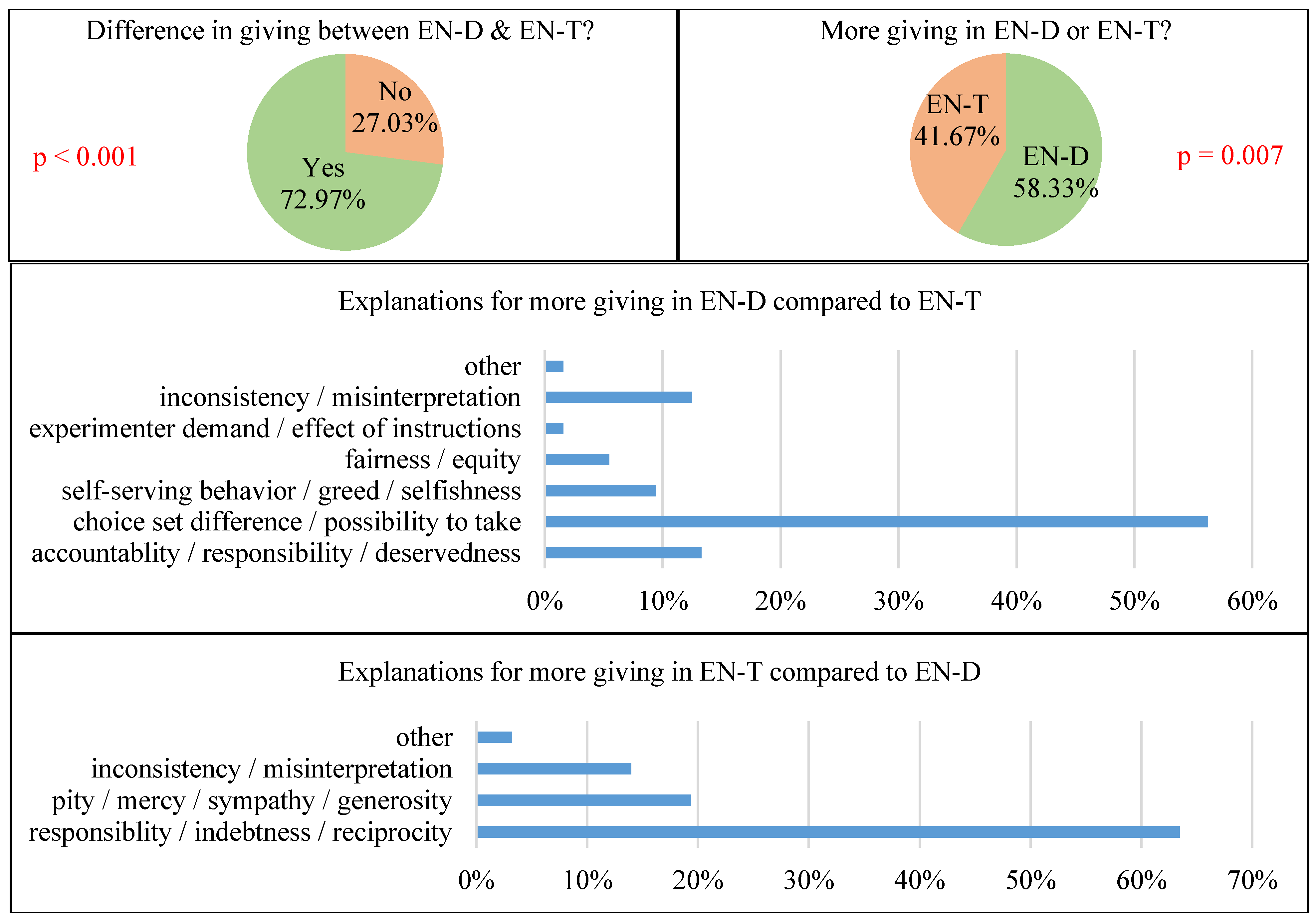

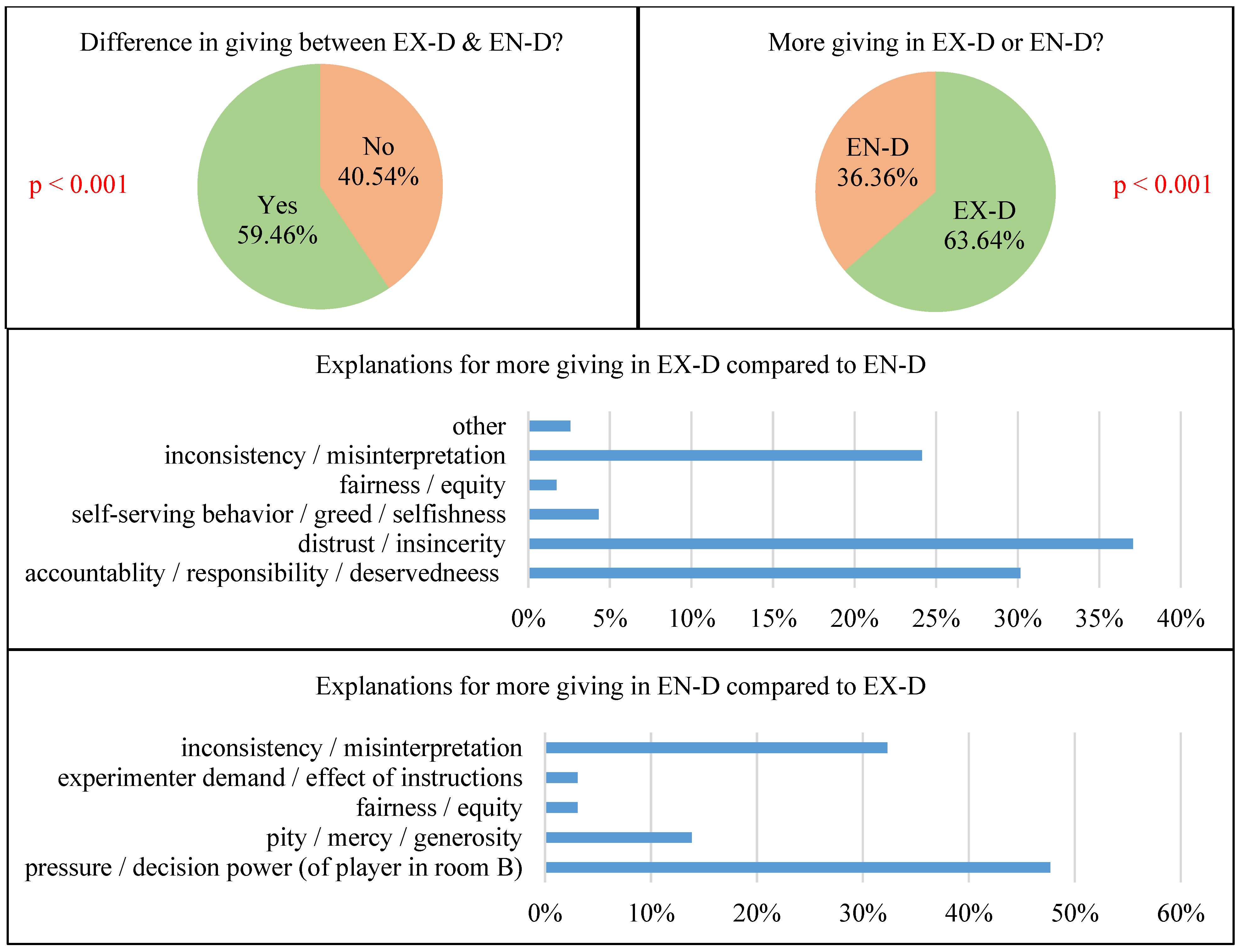

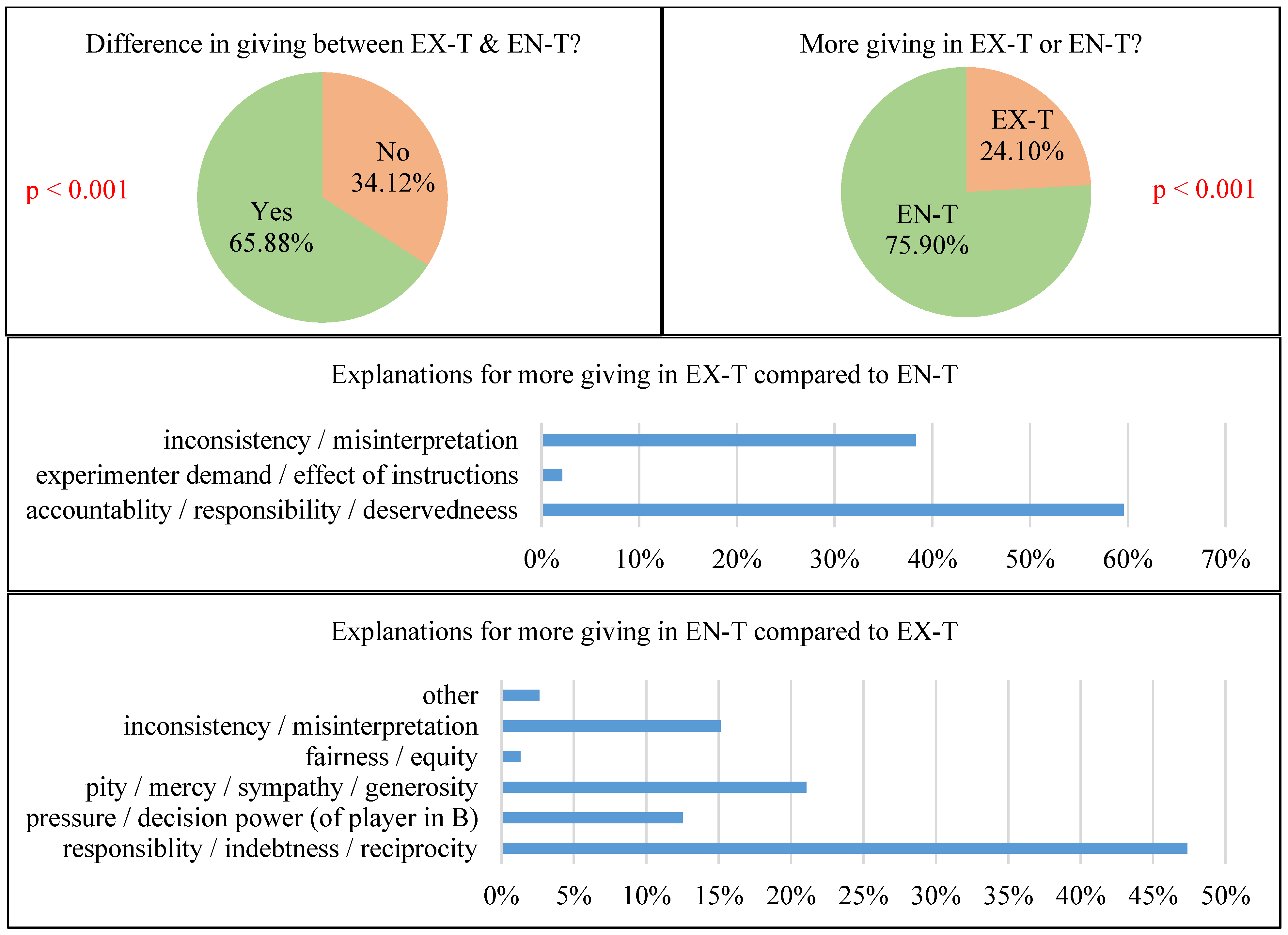

4.2. Results from the Online Survey

“Choice of Treatment 3-2 shows that the participant in Room B trusts the participant in Room A. The participant in Room A tends to transfer more money so as not to waste this trust”.

“… because B-participants might not have chosen Treatment 3-2, but they did. With this in mind, A-participants may be more sympathetic and generous to them, and A-participants may also feel somewhat responsible for sharing money”.

“… because in Treatment 2, the experimenter determined the path of the experiment. A-participants chose to transfer more money in Treatment 3-2 as B-participants made a sacrifice by putting themselves in a completely vulnerable situation”.

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Experimental Instructions and Survey

- You and the person you are paired with each have been allocated 10 TRY.

- Additionally, the person you are paired with has been provisionally allocated an additional 10 TRY. You have not been allocated this additional 10 TRY.

- EX-D: [The person you are paired with will decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to you. The choice of that person can be anywhere from 0 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.]

- EX-T: [The person you are paired with will decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to you. That person can also transfer a negative amount (i.e., can take up to 10 TRY from you). Thus, the choice of that person can be anywhere from −10 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.]

- As a result, your take-home earnings from this experiment will be the summation of your initial 10 TRY allocation and the amount the person you are paired with decided to transfer to you in this exercise. Likewise, the earnings of that person will be their initial 10 TRY allocation added to the amount left to them from this choice exercise.

- You and the person you are paired with each have been allocated 10 TRY.

- Additionally, you have been provisionally allocated an additional 10 TRY. The person you are paired with has not been allocated this additional 10 TRY.

- EX-D: [The only thing you need to do is to decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to the person you are paired with. Your choice can be anywhere from 0 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.]

- EX-T: [The only thing you need to do is to decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to the person you are paired with. You can also transfer a negative amount (i.e., you can take up to 10 TRY from the person you are paired with). Thus, your transfer choice can be anywhere from −10 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.]

- As a result, your take-home earnings from this experiment will be the summation of your initial 10 TRY allocation and the amount left to you from this choice exercise. Likewise, the earnings of the person you are paired with will be their initial 10 TRY allocation added to the amount you decided to transfer them in this exercise.

- You and the person you are paired with each have been allocated 10 TRY.

- Additionally, the person you are paired with has been provisionally allocated an additional 10 TRY. You have not been allocated this additional 10 TRY.

- The only thing you need to do is to decide which of the following experiments you want to continue with:

- ○

- Experiment 1: In this experiment, the person you are paired with will decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to you. The choice of that person can be anywhere from 0 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.

- ○

- Experiment 2: In this experiment, as well, the person you are paired with will decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to you. However, different from Experiment 1, in this experiment that person can also transfer a negative amount (i.e., can take up to 10 TRY from you). Thus, the choice of that person can be anywhere from −10 TRY to 10 TRY, in 1 TRY increments.

- As a result, your take-home earnings from this experiment will be the summation of your initial 10 TRY allocation and the amount that the person you are paired with decided to transfer you in this exercise. Likewise, the earnings of that person will be their initial 10 TRY allocation added to the amount left to them from this choice exercise.

- In front of you, there are two envelopes with “Experiment 1” or “Experiment 2” written on. Inside these envelopes there are the related experimental instructions to be given to the person you are paired with. You will have five minutes to come to a decision on which experiment you want to continue with. After five minutes, you need to give the envelope of the experiment you have chosen to the experimenter.

- There will not be any other decision you need to take throughout the experiment. You do not need to mark anything with pen to make a choice; it is enough to hand in the envelope of the chosen experiment.

- You and the person you are paired with each have been allocated 10 TRY.

- Additionally, you have been provisionally allocated an additional 10 TRY. The person you are paired with has not been allocated this additional 10 TRY.

- The person you are paired with is presented with two different experiments to choose from. In both of these experiments you are expected to decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to the person you are paired with. In one of them (Experiment 1) your choice of transfer can be any integer from 0 TRY to 10 TRY. In the other one, however, you can also transfer a negative amount (i.e., you can take up to 10 TRY from the person you are paired with, so your choice of transfer can be any integer from −10 TRY to 10 TRY).

- EN-D: [The person you are paired with has chosen the experiment without the possibility of negative transfers (Experiment 1). In this case, the only thing you need to do is to decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to the person you are paired with. Thus, your choice can be any integer from 0 TRY to 10 TRY]

- EN-T: [The person you are paired with has chosen the experiment with the possibility of negative transfers (Experiment 2). In this case, the only thing you need to do is to decide what portion, if any, of this 10 TRY to transfer to the person you are paired with. You can also transfer a negative amount (i.e., you can take up to 10 TRY from the person you are paired with). Thus, your choice can be any integer from−10 TRY to 10 TRY.]

- As a result, your take-home earnings from this experiment will be the summation of your initial 10 TRY allocation and the amount left to you from this choice exercise. Likewise, the earnings of the person you are paired with will be their initial 10 TRY allocation added to the amount you decided to transfer to them in this exercise.

- In TREATMENT 1, if the transfer choice of a person in Room A is 0, what will be the earnings of this person and his matched person in Room B from the experiment?The earnings of the decision maker in Room A: ____TRYThe earnings of the person in Room B whom the decision maker in Room A matched with: ____TRY

- In TREATMENT 2, if the transfer choice of a person in Room A is −10, what will be the earnings of this person and his matched person in Room B from the experiment?The earnings of the decision maker in Room A: ____TRYThe earnings of the person in Room B whom the decision maker in Room A matched with: ____TRY

- In TREATMENT 3, participation in TREATMENT 1 or TREATMENT 2 is determined by the participant in Room B.True ____False ____

- In TREATMENT 1, a person in Room A may choose to transfer an amount from 10 TRY given to the person he matched with in Room B to himself.True ____False ____

- In what interval can the transfer choice of the person in Room A be in TREATMENT 3-2?Any integer between ____TRY and ____TRY

- Each participant participated in all three treatments.True ____False ____

- Our current question is about the decisions taken by the participants in Room A who participated in TREATMENT 1 or TREATMENT 2. Do you think there is a difference between TREATMENT 1 and TREATMENT 2 in terms of the average amount that Room A participants chose to transfer to the matched person in Room B?No Difference ____There is a Difference ____

- If there is a difference, in which treatment do you think the participants in Room A chose to transfer more money to the matched person in Room B? In TREATMENT 1 or in TREATMENT 2?They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 1 ____They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 2 ____

- Can you briefly explain why you think that way?___________

- Our current question is about the decisions taken by the participants in Room A who participated in TREATMENT 3-1 or TREATMENT 3-2. Do you think there is a difference between TREATMENT 3-1 and TREATMENT 3-2 in terms of the average amount that Room A participants chose to transfer to the matched person in Room B?No Difference ____There is a Difference ____

- If there is a difference, in which treatment do you think the participants in Room A chose to transfer more money to the matched person in Room B? In TREATMENT 3-1 or in TREATMENT 3-2?They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 3-1 ____They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 3-2 ____

- Can you briefly explain why you think that way?____________

- Our current question is about the decisions taken by the participants in Room B who participated in TREATMENT 3. Do you think there is a difference between the frequency of choosing TREATMENT 3-1 and TREATMENT 3-2 in TREATMENT 3 (by the participants in Room B)?No Difference ____There is a Difference ____

- If there is a difference, do you think TREATMENT 3-1 or TREATMENT 3-2 was chosen more often?TREATMENT 3-1 was chosen more often ____TREATMENT 3-2 was chosen more often ____

- Can you briefly explain why you think that way?_______________

- Our current question is about the decisions taken by the participants in Room A who participated in TREATMENT 1 or TREATMENT 3. Do you think there is a difference between TREATMENT 1 and TREATMENT 3-1 in terms of the average amount that Room A participants chose to transfer to the matched person in Room B?No Difference ____There is a Difference ____

- If there is a difference, in which treatment do you think the participants in Room A chose to transfer more money to the matched person in Room B? In TREATMENT 1 or in TREATMENT 3-1?They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 1 ____They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 3-1 ____

- Can you briefly explain why you think that way?____________

- Our current question is about the decisions taken by the participants in Room A who participated in TREATMENT 2 or TREATMENT 3. Do you think there is a difference between TREATMENT 2 and TREATMENT 3-2 in terms of the average amount that Room A participants chose to transfer to the matched person in Room B?No Difference ____There is a Difference ____

- If there is a difference, in which treatment do you think the participants in Room A chose to transfer more money to the matched person in Room B? In TREATMENT 2 or in TREATMENT 3-2?They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 2 ___They chose to transfer more money in TREATMENT 3-2 ____

- Can you briefly explain why you think that way?____________

- Gender: Male___ Female ___

- Age: _____

- Department: ________

- Grade: _________

- Have you taken a course on Game Theory, Experimental Economics, Behavioral Economics (e.g., ECON 204, ECON439, ECON 444)?Yes ____ No ____

- Between December 2019 and March 2020, as mentioned in the survey, Res. See. Have you participated in one of the Decision Making Experiments conducted by Elif Tosun?Yes ____ No ____

Appendix B. Additional Analyses

| Dependent Variable: Zerogiving | Dependent Variable: Fivegiving | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Endogenous | 1.382 ** | 1.929 ** | 0.113 | 0.0124 |

| (0.021) | (0.011) | (0.812) | (0.983) | |

| Male | 1.035 * | 1.321 ** | 0.226 | 0.0911 |

| (0.066) | (0.047) | (0.590) | (0.852) | |

| Endogenous x Male | −1.382 * | −1.822 ** | −0.0328 | 0.124 |

| (0.051) | (0.032) | (0.956) | (0.858) | |

| Constant | −1.465 *** | 247.0 | −0.366 | −54.44 |

| (0.004) | (0.120) | (0.286) | (0.693) | |

| N | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.068 | 0.166 | 0.005 | 0.077 |

| p-Value | 0.0892 | 0.2584 | 0.9038 | 0.8378 |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dependent Variable: Zerogiving | Dependent Variable: Fivegiving | Dependent Variable: Minustengiving | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Endogenous | (Omitted) | (Omitted) | −0.381 | −0.994 | −0.0584 | 0.915 |

| (0.446) | (0.193) | (0.914) | (0.248) | |||

| Male | 0.476 | 6.272 | −0.671 | −0.912 * | −0.0152 | 0.473 |

| (0.351) | (0.265) | (0.108) | (0.083) | (0.972) | (0.421) | |

| Endogenous x Male | (Omitted) | (Omitted) | 0.428 | 0.574 | 0.780 | 0.143 |

| (0.638) | (0.613) | (0.382) | (0.897) | |||

| Constant | −1.405 *** | 1284.2 | −0.0502 | 379.9 * | −0.706 ** | −202.0 |

| (0.000) | (0.223) | (0.841) | (0.093) | (0.010) | (0.467) | |

| N | 42 | 27 | 55 | 54 | 55 | 54 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.029 | 0.452 | 0.041 | 0.269 | 0.019 | 0.218 |

| p-Value | 0.3483 | 0.2303 | 0.3948 | 0.1181 | 0.7492 | 0.4111 |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Dependent Variable: Passive Dummy | ||

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Male | −0.0107 | −0.0286 |

| (0.978) | (0.953) | |

| Constant | −0.623 ** | −237.7 |

| (0.011) | (0.302) | |

| N | 49 | 47 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.000 | 0.133 |

| p-Value | 0.6873 | 0.6873 |

| Controls | No | Yes |

| 1 | It is fair to say that Eichenberger and Oberholzer-Gee [55] tested the taste for fairness earlier by comparing the standard dictator game with their “gangster game”, where the player can take money from an anonymous student. However, in this game, the player has no chance of giving any money, so overall it is a different game and not a dictator game with a taking option. Nevertheless, this experiment produced some striking results, where the property rights were clearly assigned via a pre-experimental test yet the gangsters took more than three-quarters of the earned endowment of the better-graded students, pointing at why the game is named as such. |

| 2 | Brosig et al. [26] also used taking games as a part of their experiments, but this was not the focus of their paper. |

| 3 | Examples abound. For instance, if one does not want to haggle, then one may choose to buy goods from outlets where there are fixed prices and no room for bargaining. If one does not want to compete, then one may choose to work under a per-piece-payment contract rather than under a rank-order tournament contract. If one is not good at saying “no”, then one may choose not to receive calls from donation campaigns. Our setup is not designed to accommodate a specific real-life instance, but the question that we tackle in this paper is inspired from such examples. |

| 4 | At the time we ran our experiments, 10 TRY was approximately equal to USD 2. |

| 5 | Thus, in both games, the payoff to the dictator was 20 TRY minus the allocation amount, and the payoff to the receiver was 10 TRY plus the allocation amount, where the allocation amount differed between the games as explained. |

| 6 | Throughout this paper, the dictator and taking games played due to the endogenous selection of the receiver are referred to as EN-D and EN-T, respectively. |

| 7 | In particular, the receivers also had the instructions given to the dictators at hand. |

| 8 | Needless to say, no theoretical model with standard preferences would predict that an agent would choose the taking game. |

| 9 | For another use of this phrase, see Regner and Matthey [56]. |

| 10 | We refer to the rationalization in psychology, meaning the defense mechanisms in which apparent logical reasons are given to justify behavior that is motivated by unconscious instinctual impulses. |

| 11 | We chose to conduct a standalone survey rather than asking open-ended questions to the participants of the experiment because we expected the answers to the latter to be biased and subject to rationalization/justification biases. |

| 12 | We used Levene’s robust test statistic for the equality of variances between groups. |

| 13 | Running tobit regressions instead of OLS does not qualitatively change the results. |

| 14 | Two subjects chose not to report their gender. |

| 15 | In reporting these results, we omitted one pair because the subject in the dictator role in this pair clearly did not understand the instructions, leaving us with 133 pairs. The subject was a dictator in the EX-T treatment, but he did not understand what to do in the experiment even after we answered all of his questions about the instructions. When we were collecting the envelopes, his decision form was still not ready, and we had to explain what he had to do one more time. Finally, all of our results are robust to the inclusion of this pair. |

| 16 | This is the only situation where we found unequal variances between the compared samples, and using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test as a robustness check did not change our result (i.e., (i) p = 0.006 and (ii) p = 0.0425). |

| 17 | We would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting that we have a look at the proportion of positive offers and the mean positive offer across treatments. |

| 18 | Using binomial tests did not change our result (i.e., p < 0.0005). |

| 19 | Using the Mann–Whitney test as a robustness check yielded the same conclusion, but with a significance level of 10% instead of the conventional 5% (i.e., p = 0.0509). |

| 20 | Using the Mann–Whitney test did not change our result (i.e., p = 0.7372). |

| 21 | The Endogenous variable is present only in specifications (1) and (2), since only those specifications use the pooled data. |

| 22 | Note that the number of observations is not 78 due to the missing values in the gender variable, as explained earlier. |

| 23 | For the results without the gender effects, one can refer to the statistical tests section, where we provide the overall differences between treatments without controlling for any other variable. |

| 24 | The gender differences in mean giving calculated from Table 5 and Table 6 directly matched with the corresponding coefficients presented in column 3 of Table 3 and Table 4, respectively, since we did not have the controls in that specification while having the interaction term necessary to differentiate the effects of gender in the exogenous and endogenous treatments. |

| 25 | This difference directly corresponds to the Male coefficient in column 3 of Table 3 (−1.78), meaning that male dictators give 1.78 TRY less on average compared to female dictators in EX-D. |

| 26 | This difference can be found from the sum of the Male and Endogenous x Male coefficients in column 3 of Table 3. |

| 27 | This is the reason why its coefficient is 2.352 in column 3 of Table 3; it is the differential treatment effect for males because the coefficient corresponds to the difference between the treatment effects for men (−0.244) and for women (−2.595). |

| 28 | While interpreting these results, it should be noted that each explanation from the survey participants can fall into multiple categories, so the sum of these percentages does not add up to 100. Moreover, we combined similar keywords/explanations into a single category for the ease of both categorizing and reading the results, but this does not imply that each explanation that falls into a specific category includes all of the keywords written in the heading of that category. |

References

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.; Thaler, R. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. J. Bus. 1986, 59, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R.; Horowitz, J.; Savin, N.E.; Sefton, M. Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. Strategy and equity: An ERC-analysis of the Güth-van Damme game. J. Math. Psychol. 1998, 62, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A theory of fairness competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.K. Modeling altruism and spitefulness in experiments. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 1998, 1, 593–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Miller, J. Giving according to GARP: An experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism. Econometrica 2002, 70, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkes, H.R.; Joyner, C.A.; Pezzo, M.V.; Nash, J.G.; Siegel-Jacobs, K.; Stone, E. The psychology of windfall gains. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1994, 59, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Shachat, K.; Smith, V.L. Preferences, property rights, and anonymity in bargaining games. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 7, 346–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A.; Hole, A.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B. The pluralism of fairness ideals: An experimental approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, T. Mental accounting and other-regarding behavior: Evidence from the lab. J. Econ. Psychol. 2001, 22, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, T.; Frykblom, P.; Shogren, J.F. Hardnose the dictator. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.; Cherry, T. Examining the role of fairness in high stakes allocation decisions. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 65, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxoby, R.; Spraggon, J. Mine and yours: Property rights in dictator games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 65, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larney, A.; Rotella, A.; Barclay, P. Stake size effects in ultimatum game and dictator game offers: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2019, 151, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, C.; Grossman, P. Altruism in anonymous dictator games. Games Econ. Behav. 1996, 16, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, J.; Weber, R.A.; Kuang, J.X. Exploiting the moral wiggle room: Experiments demonstrating an illusory preference for fairness. Econ. Theory 2007, 33, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Smith, V.L. Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 653–660. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnet, I.; Frey, B. The sound of silence in prisoner’s dilemma and dictator games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1999, 38, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, F. Requests and social distance in dictator games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branas-Garza, P. Poverty in dictator games: Awakening solidarity. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, F.; Branas-Garza, P.; Miller, L.M. Mora distance in dictator games? Judgement Decis. Mak. 2008, 3, 344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S.; Eckel, C. The economic value of status. J. Socio-Econ. 1998, 27, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaugh, W. The prestige motive for making charitable transfers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Brosig, J.; Riechmann, T.; Weimann, J. Selfish in the end? An investigation of consistency and stability of individual behavior. FEMM Work. Pap. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Sadiraj, K.; Sadiraj, V. Trust, Fear, Reciprocity and Altruism; University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA; Mimeo: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- List, J. On the interpretation of giving in dictator games. J. Political Econ. 2007, 115, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardsley, N. Dictator game giving: Altruism or artefact? Exp. Econ. 2008, 11, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A.W.; Nielsen, H.U.; Sørensen, E.Ø.; Tungodden, B.; Tyran, J.-R. Give and take in dictator games. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2013, 118, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, M.M.; Navarro-Martinez, D. On the external validity of social preference games: A systematic lab-field study. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Navarro-Martinez, D. Bridging the gap between the lab and the field: Dictator games and donations. Barc. GSE Work. Pap. 2021. Available online: https://beta.u-strasbg.fr/WP/2016/2016-37.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Lambert, E.A.; Tisserand, J.C. Does the obligation to bargain make you fit the mould? An experimental analysis. BETA Work. Pap. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.L.; Wilson, B.J. Equilibrium play in voluntary ultimatum games: Beneficence cannot be extorted. Games Econ. Behav. 2018, 109, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Zwick, R. Anonymity versus punishment in ultimatum bargaining. Games Econ. Behav. 1995, 10, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Bernheim, B.D. Social image and the 50–50 norm: A theoretical and experimental analysis of audience effects. Econometrica 2009, 77, 1607–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, S.D.; List, J. What do laboratory experiments measuring social preferences reveal about the real world? J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, A.; Pointner, S. The external validity of giving in the dictator game: A field experiment using the misdirected letter technique. Exp. Econ. 2013, 16, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, J. From the lab to the field: Envelopes, dictators and manners. Exp. Econ. 2014, 17, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholzer-Gee, F.; Eichenberger, R. Fairness in extended dictator game experiments. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2008, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, T.; Riechmann, T.; Weimann, J. Game or frame? Incentives in modified dictator games. FEMM Work. Pap. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenok, O.; Millner, E.L.; Razzolini, L. Taking aversion. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 150, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lara, I.; Moreno-Garrido, L. Self-interest and fairness: Self-serving choices of justice principles. Exp. Econ. 2012, 15, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regner, T. Reciprocity under moral wiggle room: Is it a preference or a constraint? Exp. Econ. 2018, 21, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konow, J. Fair Shares: Accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.D.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Swann, W.B. A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. J. Res. Personal. 2003, 37, 504–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Munn, P. Siblings and the development of prosocial behavior. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1986, 9, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. Dictator games: A meta study. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.M.; Jeon, J.Y.; Saha, B. Gender differences in the giving and taking variants of the dictator game. South. Econ. J. 2017, 84, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J.; Vesterlund, L. Which is the fair sex? Gender differences in altruism. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Deck, C. When are women more generous than men? Econ. Inq. 2006, 44, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. On the nature of pessimism in taking and giving games. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2015, 54, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M.; Mollerstrom, J.; Munkhammar, S. Gender differences in social framing effects. Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, M. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 1281–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger, R.; Oberholzer-Gee, F. Rational moralists: The role of fairness in democratic economic politics. Public Choice 1998, 94, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regner, T.; Matthey, A. Actions and the Self: I Give, Therefore I am? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 684078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | Min | Max | Proportion of Positive Offers | Mean Positive Offer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX-D | 41 | 3.756 | 2.835 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0.756 | 4.968 |

| EX-T | 42 | −1.167 | 6.484 | 0 | −10 | 10 | 0.452 | 5.053 |

| EN-D | 37 | 2.729 | 2.341 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0.622 | 4.391 |

| EN-T | 13 | −2.231 | 7.270 | −5 | −10 | 8 | 0.461 | 5 |

| Dependent Variable: Dictator Decision | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled | Exogenous Treatment | Endogenous Treatment | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Take | −5.098 *** | −5.216 *** | −5.127 *** | −5.514 *** | −5.043 *** | −4.498 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.009) | |

| Endogenous | −1.139 | −1.035 | ||||

| (0.197) | (0.286) | |||||

| Male | −0.702 | −0.493 | −0.806 | −0.252 | −0.528 | −0.908 |

| (0.411) | (0.588) | (0.484) | (0.842) | (0.674) | (0.509) | |

| Byear | −0.022 | 0.162 | −0.354 | |||

| (0.908) | (0.524) | (0.242) | ||||

| Sibling | 0.816 | 0.913 | 0.537 | |||

| (0.115) | (0.141) | (0.645) | ||||

| Income | 1.235 ** | 1.085 | 0.851 | |||

| (0.018) | (0.144) | (0.280) | ||||

| Extravert | 0.088 | 0.285 | −0.155 | |||

| (0.593) | (0.230) | (0.544) | ||||

| Agree | −0.005 | 0.028 | −0.144 | |||

| (0.979) | (0.934) | (0.601) | ||||

| Consc | 0.098 | −0.192 | 0.400 * | |||

| (0.559) | (0.450) | (0.089) | ||||

| Stable | 0.196 | 0.173 | 0.170 | |||

| (0.195) | (0.405) | (0.486) | ||||

| Open | −0.264 | −0.624 ** | 0.312 | |||

| (0.225) | (0.035) | (0.372) | ||||

| Econ | −1.531 | −2.126 | 0.978 | |||

| (0.205) | (0.151) | (0.697) | ||||

| Monday | −1.091 | −1.088 | 0.000 | |||

| (0.365) | (0.405) | (.) | ||||

| Constant | 4.217 *** | 42.92 | 4.287 *** | −317.6 | 2.974 *** | 700.0 |

| (0.000) | (0.908) | (0.000) | (0.531) | (0.005) | (0.248) | |

| N | 132 | 131 | 83 | 83 | 49 | 48 |

| R2 | 0.207 | 0.290 | 0.202 | 0.333 | 0.220 | 0.370 |

| adj. R2 | 0.189 | 0.211 | 0.182 | 0.218 | 0.186 | 0.178 |

| prob(F-stat) | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.0033 | 0.0686 |

| Dependent Variable: Dictator Decision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Endogenous | −1.137 * | −1.520 ** | −2.595 *** | −3.212 *** |

| (0.062) | (0.026) | (0.008) | (0.004) | |

| Male | −0.635 | −0.370 | −1.780 ** | −1.670 * |

| (0.307) | (0.574) | (0.039) | (0.070) | |

| Endogenous x Male | 2.352 * | 2.556 ** | ||

| (0.056) | (0.047) | |||

| Byear | 0.219 | 0.201 | ||

| (0.112) | (0.135) | |||

| Sibling | 0.993 ** | 0.840 ** | ||

| (0.017) | (0.041) | |||

| Income | 0.443 | 0.291 | ||

| (0.242) | (0.438) | |||

| Extravert | −0.047 | −0.056 | ||

| (0.687) | (0.626) | |||

| Agree | −0.162 | −0.226 | ||

| (0.285) | (0.137) | |||

| Consc | 0.141 | 0.116 | ||

| (0.261) | (0.348) | |||

| Stable | −0.017 | −0.057 | ||

| (0.878) | (0.599) | |||

| Open | 0.018 | 0.036 | ||

| (0.918) | (0.833) | |||

| Econ | −0.362 | −0.021 | ||

| (0.682) | (0.981) | |||

| Monday | −1.661 * | −1.775 * | ||

| (0.082) | (0.058) | |||

| Constant | 4.174 *** | −434.4 | 4.929 *** | −396.9 |

| (0.000) | (0.114) | (0.000) | (0.140) | |

| N | 77 | 77 | 77 | 77 |

| R2 | 0.056 | 0.240 | 0.102 | 0.286 |

| adj. R2 | 0.030 | 0.097 | 0.065 | 0.139 |

| p-value | 0.1188 | 0.0919 | 0.0476 | 0.0415 |

| Dependent Variable: Dictator Decision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Endogenous | −1.141 | −3.058 | 0.200 | −1.610 |

| (0.596) | (0.247) | (0.939) | (0.618) | |

| Male | −0.795 | −0.540 | 0.0824 | 0.400 |

| (0.673) | (0.797) | (0.969) | (0.870) | |

| Endogenous x Male | −4.082 | −3.713 | ||

| (0.376) | (0.439) | |||

| Byear | −0.502 | −0.536 | ||

| (0.303) | (0.276) | |||

| Sibling | 0.118 | 0.123 | ||

| (0.914) | (0.911) | |||

| Income | 2.846 ** | 2.672 * | ||

| (0.035) | (0.051) | |||

| Extravert | 0.338 | 0.331 | ||

| (0.397) | (0.409) | |||

| Agree | 0.282 | 0.221 | ||

| (0.569) | (0.661) | |||

| Consc | −0.032 | 0.012 | ||

| (0.934) | (0.975) | |||

| Stable | 0.279 | 0.301 | ||

| (0.435) | (0.404) | |||

| Open | −0.315 | −0.346 | ||

| (0.496) | (0.459) | |||

| Econ | −2.596 | −2.743 | ||

| (0.383) | (0.360) | |||

| Monday | −0.685 | −0.434 | ||

| (0.789) | (0.867) | |||

| Constant | −0.845 | 991.8 | −1.200 | 1059.3 |

| (0.514) | (0.309) | (0.377) | (0.282) | |

| N | 55 | 54 | 55 | 54 |

| R2 | 0.008 | 0.250 | 0.023 | 0.261 |

| adj. R2 | −0.030 | 0.030 | −0.034 | 0.021 |

| p-value | 0.8077 | 0.3583 | 0.7475 | 0.3969 |

| Treatment | Gender | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX-D | Female | 14 | 4.928 | 2.731 | 5 | 0.0554 |

| Male | 27 | 3.148 | 2.741 | 5 | ||

| EN-D | Female | 15 | 2.333 | 2.469 | 1 | 0.4785 |

| Male | 21 | 2.904 | 2.278 | 3 |

| Treatment | Gender | N | Mean | Standard Deviation | Median | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX-T | Female | 25 | −1.2 | 6.621 | 0 | 0.9684 |

| Male | 17 | −1.117 | 6.480 | 0 | ||

| EN-T | Female | 9 | −1 | 7.416 | 2 | 0.3829 |

| Male | 4 | −5 | 7.071 | −7.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karagözoğlu, E.; Tosun, E. Endogenous Game Choice and Giving Behavior in Distribution Games. Games 2022, 13, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/g13060074

Karagözoğlu E, Tosun E. Endogenous Game Choice and Giving Behavior in Distribution Games. Games. 2022; 13(6):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/g13060074

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaragözoğlu, Emin, and Elif Tosun. 2022. "Endogenous Game Choice and Giving Behavior in Distribution Games" Games 13, no. 6: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/g13060074

APA StyleKaragözoğlu, E., & Tosun, E. (2022). Endogenous Game Choice and Giving Behavior in Distribution Games. Games, 13(6), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/g13060074