Abstract

We construct a dynamic bilateral monopoly game to analyze the bargaining between a foreign manufacturer and a domestic retailer regarding the wholesale price and explain the foreign upstream firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiative and its economic impacts on the domestic market. Under free trade, the foreign upstream firm’s CSR initiative realizes improvements in consumer surplus and social welfare in the home country. A “win–win–win” strategy exists, as the foreign manufacturer has more of an incentive to implement CSR when the government implements a strategic trade policy. The consumer-friendly action implemented by the foreign upstream firm leads to adequate consumer welfare and social welfare, which mitigates the government’s political hostility. With the high bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm and the low weight of the consumer-friendly upstream firm, the government should set a higher tariff rate for the foreign upstream firm to extract rent and enhance social welfare.

JEL Classification:

F13; L11; L81; M14

1. Introduction

With the tide of globalization, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is frequently observed in firms’ transnational management. For example Wang [1] points out that foreign firms will actively undertake consumer-friendly CSR. One typical example is the Ford Car company in the automotive industry. As Henry Ford said: “There is one rule for the industrialist and that is: Make the best quality of goods possible at the lowest cost possible, paying the highest wages possible”. Stakeholder interests have always been a research focus for managers and academics.

Carroll (1979) [2] proposed a three-dimensional conceptual model to address the major concerns of academics and managers in CSR. One of them is the reaction to consumerism and economic responsibilities. The feasibility and desirability of CSR has been a primary focus ever since Porter and Kramer [3] provided a systematic dissection of corporate social responsibility and its linkage to firms’ competitiveness. Why should firms advance the CSR concern? This question has aroused considerable attention among entrepreneurs and economists. Carroll and Shabana [4] argued that firms will implement CSR as long as it enhances their profits or corporate financial performance. Modern international enterprises tend to separate vertical supply chains, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (TSMC) and Intel Corporation (Santa Clara, CA, USA). TSMC is a professional chips supplier in the upstream, while Intel is a downstream CPU seller. The market structure of vertical supply chain separation has also become the focus of scholars’ research [5,6,7,8]. In Taiwan, TSMC is a benchmark company that undertakes a lot of CSR. Based on common observations and ongoing research, we attempt to supplement the existing CSR literature by constructing a simple bilateral monopolistic framework that is capable of explaining foreign upstream firms’ CSR initiatives and their economic impacts on the domestic market.

Without considering international trade, Goering [9] first examined a bilateral monopolistic market in a two-stage game with unilateral CSR initiatives. The results showed that, given that an upstream manufacturer engages in CSR activities, a two-part tariff scheme fully coordinates the marketing channel and allows for the upstream firm to achieve its joint objective, but the upstream firm has to suffer from profit loss, which indicates that CSR is not feasible according to the definition given by Carroll and Shabana [4]. Goering [10] further demonstrated that, using the two-part CSR contract, the manufacturer can completely control the downstream retailer and earn full monopoly profits without vertical integration. Brand and Grothe [11] noted that, in a vertical structure where the upstream and downstream firm both implement CSR initiatives, all firms and consumers will be better off. Ouchida [12], in a linear bilateral monopoly model, examined the endogenous and cooperative choice of CSR level on the market and welfare and solved the double marginalization problem. Fanti and Buccella [13] showed that only the downstream firm is always incentivized to adopt CSR if it has decreasing returns to the input.

In a global economy context, Wang et al. [14] extended the third-country model with tariffs, showing a “win–win–win” solution for foreign exporters’ consumer-friendly behavior. Chang et al. [15] found similar results in an import-competing duopolistic framework: a dominant strategy exists when firms’ payoffs, consumer surplus and social welfare are at their maximum levels. Fanti and Buccella [16] set up a strategic trade policy model in which two national champions compete in a third country and both governments can tax or subsidize the production of its local champion. However, the CSR literature on the vertical market structure with international trade is still insufficient.

In our analysis, we construct a stylized distribution channel model in a global economy context, where a domestic retailer makes price-setting decisions, given the linear wholesale price, bargained with a foreign manufacturer. Here, the bilateral monopoly is used to depict a common picture in the real world when a brand-new product enters the domestic market. The foreign upstream firm may behave like a consumer-friendly manufacturer in order to win consumers’ hearts and gain more bargaining power on the wholesale price. For example, China is a large importer of high semiconductor chip products from foreign upstream firms. Due to the high product differentiation, a specialized kind of chip, when imported into China, may monopolize the upstream market. For the convenience of sales promotion, the downstream firm is more likely to be a domestic one, sophisticated enough to understand the preference of domestic customers.

Our main results show that CSR can act as a quid pro quo device for the foreign monopolist and lead to tremendous improvements in consumer and social welfare. The quid pro quo role of CSR indicates that the foreign firm can tangibly mitigate a government’s political hostility and benefit from engaging in CSR practices. For the benchmark, we first investigate a case of free trade. This conveys that the foreign upstream firm’s consumer-friendly behavior realizes higher consumer welfare and social welfare. However, consumer-friendly initiatives are always costly for the firm. An increase in a firm’s emphasis on CSR reduces its own profit, which does not seem to be practicable for a privately beneficial solution. Hence, the driving force for the CSR initiative can be interpreted as “the warm glow” or some altruistic tendency, because there are no extra gainful profits. We also show that upstream firms’ emphasis on CSR directly impacts the wholesale pass-through rate, and the wholesale pass-through rate actually becomes larger if the upstream firm is consumer-friendly. Furthermore, we consider the inclusion of government intervention and provide some evidence as to why a foreign exporting firm has an incentive to care about consumers’ well-being in our theoretical analysis: when a foreign upstream firm faced with trade policies implements a consumer-oriented CSR, there is a strong chance of a “win–win–win” solution, where the firm’s profitability, consumer surplus and social welfare are all improved. In accordance with Porter and Kramer [3], we show that CSR can become a source of tremendous social progress under appropriate circumstances.

The contribution of our framework is that we point out that the bargaining power of the wholesale price of goods and consumer-friendly initiatives taken by a foreign upstream firm lead to an adequate consumer surplus and social welfare, which can mitigate the government’s political hostility.

2. Basic Model

There is one foreign manufacturer (upstream firm ) exporting to the home country through one domestic retailer (downstream firm ). The retail demand function is given by , . , and denote the market size, demand quantity and market price, respectively.

Firstly, we consider the case of free trade, with the foreign consumer-friendly manufacturer as a benchmark. Then, a scenario including the government’s strategic trade policies will be more elaborately examined.

Stemming from the framework of Bresnahan and Reiss [17] and Gaudin [18], the linear wholesale price depends on upstream–downstream bargaining. We follow the setting of Horn and Wolinsky [19] by considering the Nash-bargaining solution of this problem. The parameter denotes the exogenous bargaining power of the manufacturer, and the retailer has the remaining bargaining power.

The downstream firm’s profit is , and denotes the wholesale price of goods. Under free trade, the upstream firm’s profit can be expressed by . Additionally, when the upstream firm is faced with a trade policy, the profit is . Here, represents the manufacturer’s marginal production and transportation costs. Since either tariffs or subsidies are levied ad valorem, denotes the import tariff rate (subsidy) and whether this is positive (negative), as in the classical setting used in Spengler [20] and in Brander and Spencer [21]. In our analysis, we adopt a generally accepted setting of consumer-oriented CSR, which is defined as initiatives to care about consumers’ well-being: If an upstream firm implements CSR, its objective function becomes . Here, represents a firm’s emphasis on its end-customers. In particular, means that the upstream firm has no concerns about consumer well-being. The theoretical modeling of CSR under imperfect competition has become increasingly popular (The case of endogenous is worth consideration in the literature on CSR under oligopoly. Kopel and Brand [22] examine socially responsible firms and the endogenous choice of strategic incentives).

Now, we focus on welfare analysis. According to the specification of linear demand function, the consumer welfare is calculated by . Under free trade, social welfare is defined as . If a home country implements a strategic trade policy, social welfare is , involving a fraction of government revenue.

The game structure of the modelling is as follows:

- The government decides the optimal tariff with respect to .

- The manufacturer and retailer bargain on the linear wholesale price .

- The retailer sets the selling price for consumers.

3. CSR Firm without Government Intervention

To begin with, we consider the case of free trade with a foreign, consumer-friendly manufacturer and begin this sub-section by considering a bilateral monopoly with a foreign upstream firm that is trying to be friendly with domestic consumers and implements such a strategy via its local dealer. This framework allows us to focus on a common situation around the world, where trade takes place due to product differentiation (for instance, a brand-new electronics design) rather than because of any comparative advantage.

The game is solved by backwards induction. In the second stage, the retailer sets the selling price for domestic consumers.

The first-order condition for a retailer’s profit maximization is therefore:

with the second-order condition:

By solving the first-order condition, we obtain the selling price: .

Plugging this equation into , we move onto the first stage: wholesale price bargaining between the manufacturer and retailer.

leading to first- and second-order conditions:

We assume to ensure that the output of the firms is always non-negative. Equation (6) is the second-order condition, which is satisfied if . The second-order condition guarantees that bargaining can obtain the maximum value of the objective function.

From Equation (5), the equilibrium wholesale price is thus obtained as follows:

We solve the sub-game’s perfect Nash equilibrium:

Then, the firms’ profits are shown as follows:

To ensure that the price and the firms’ profits are always non-negative, hereafter, we assume that .

Following Bulow and Pfleiderer [23] and Gaudin [18], the pass-through rates are calculated to cover the main interests in a double marginalization problem. It is shown that an upstream firm’s emphasis on CSR directly impacts the wholesale pass-through rate.

Notice that , , which reflects that the wholesale pass-through rate actually becomes larger if the upstream firm is consumer-friendly. The impact of a cost shock for the manufacturer seems magnified by the inclusion of a firm’s consumer-oriented CSR.

Since we mainly focus on domestic welfare, consumer surplus and social welfare are of vital importance to explain the impact of an upstream firm’s CSR initiatives.

Proposition 1.

Under free trade, consumer-friendly behavior is always costly for the upstream firm. An increase in a firm’s emphasis on CSR reduces its own profit, which does not seem practicable for a privately beneficial solution.

Proof.

Notice that . □

The economic intuition behind this proposition is as follows: Holding CSR initiatives, the manufacturer is not willing to hurt its end-customers by setting a high wholesale price. With an increasing , the consumer-friendly upstream firm emphasizes its end-customers’ welfare, and the wholesale price lowers through bargaining, i.e., , leading to a higher output for consumers. The firm has to suffer some loss of profit, which does not seem practicable for a privately beneficial solution. According to Proposition 1, the consumer-friendly manufacturer probably undertakes CSR initiatives to obtain “the warm glow” or due to some altruistic tendency, because there are no extra gainful profits.

In addition, the consumer-friendly initiative may substitute a government’s additional antitrust enforcement, since the monopoly manufacturer voluntarily sets a lower wholesale price. For example, when and the upstream firm’s emphasis on CSR satisfies , the equilibrium wholesale price is equal to marginal cost , reflecting that the government’s role in antitrust goals may become unnecessary.

Proposition 2.

Under free trade, a foreign upstream firm’s CSR initiative realizes improvements in consumer surplus and social welfare in the home country.

Proof.

and . □

As mentioned, a foreign upstream firm’s CSR initiative contributes to increased consumer welfare and social welfare. In accordance with Porter and Kramer [3], it is shown under free trade that corporate social responsibility can become a source of tremendous social progress, which is a great challenge for responsible firms.

4. CSR Firm with Strategic Trade Policy

We next consider the case of a global economy with a government’s strategic trade policy. An open economy scenario is crucial to consider when a foreign manufacturer enters the domestic market and the government in the home country sets a strategic trade policy in view of domestic welfare. The stage 3 results are similar to the free-trade setting.

With a strategic trade policy, the foreign upstream firm’s profit is now a function of , unit tariff rate. Considering wholesale price bargaining in the second stage,

we obtain first- and second-order conditions:

The equilibrium wholesale price is thus obtained as follows:

Moving back to the first stage, we introduce an endogenous welfare-maximizing trade policy. In this part, we refer to more of the literature on international trades, such as Brander and Spencer [21], among others. The government will decide a value according to social welfare maximization.

with first- and second-order conditions:

Equation (22) is the second-order condition, which is satisfied if . The second-order condition guarantees that the strategic trade policy can obtain the maximum value for the government.

We obtain the equilibrium tariff rate (subsidy):

Proposition 3.

Under a strategic trade policy, an import tariff is employed if the bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm is large.

According to the strategic trade policy theorem, on the one hand, an import tariff imposed on the foreign upstream firm raises the wholesale price and decreases the output of the downstream firm and the consumer surplus. On the other hand, the import tariff will extract the rent of the foreign upstream firm, improve the trade terms and increase the tariff revenue. If the bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm is relatively large, a positive import tariff is needed to extract the rent of the foreign upstream and enhance social welfare. It is easy to see that ; the import tariff is increasing in the bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm.

With an increasing , the consumer-friendly upstream firm emphasizes its end-customers’ welfare, and the wholesale price is lowered through bargaining, i.e., , leading to a lower tariff rate for the foreign upstream firm.

We solve the sub-game perfect Nash equilibrium:

The firms’ profits are obtained by:

We also calculate the wholesale and retail pass-through and compare them with those in the case of free trade.

Since , a CSR initiative also increases the wholesale pass-through in the case with strategic trade policy, leading to a more sensitive response to a potential cost shock. Comparing Equations (13) and (30), we find , depending on whether the government places an import tariff or subsidy.

In this scenario, the consumer surplus and social welfare are as follows:

When we compare social welfare in these two cases, shows that the home country has an incentive to set a strategic trade policy.

Proposition 4.

Circumstances with a “win–win–win” situation exist due to a firm’s consumer-friendly behavior. A foreign upstream firm has more incentive to implement CSR when a government implements a strategic trade policy.

Proof.

and , which suffices to prove that CSR initiatives improve both consumer and social welfare. □

Not surprisingly, higher CSR initiatives will lead to a higher consumer surplus. This result is consistent with those of Wang et al. [14] and Chang et al. [15]; however, their mechanisms are different. According to Wang et al. [14] and Chang et al. [15], higher CSR initiatives make the firms more aggressive and move the reaction function outward, leading to a higher output in the firms. In our framework, a higher CSR initiative will lead to lower wholesale prices, expand the downstream output and improve both consumer and social welfare.

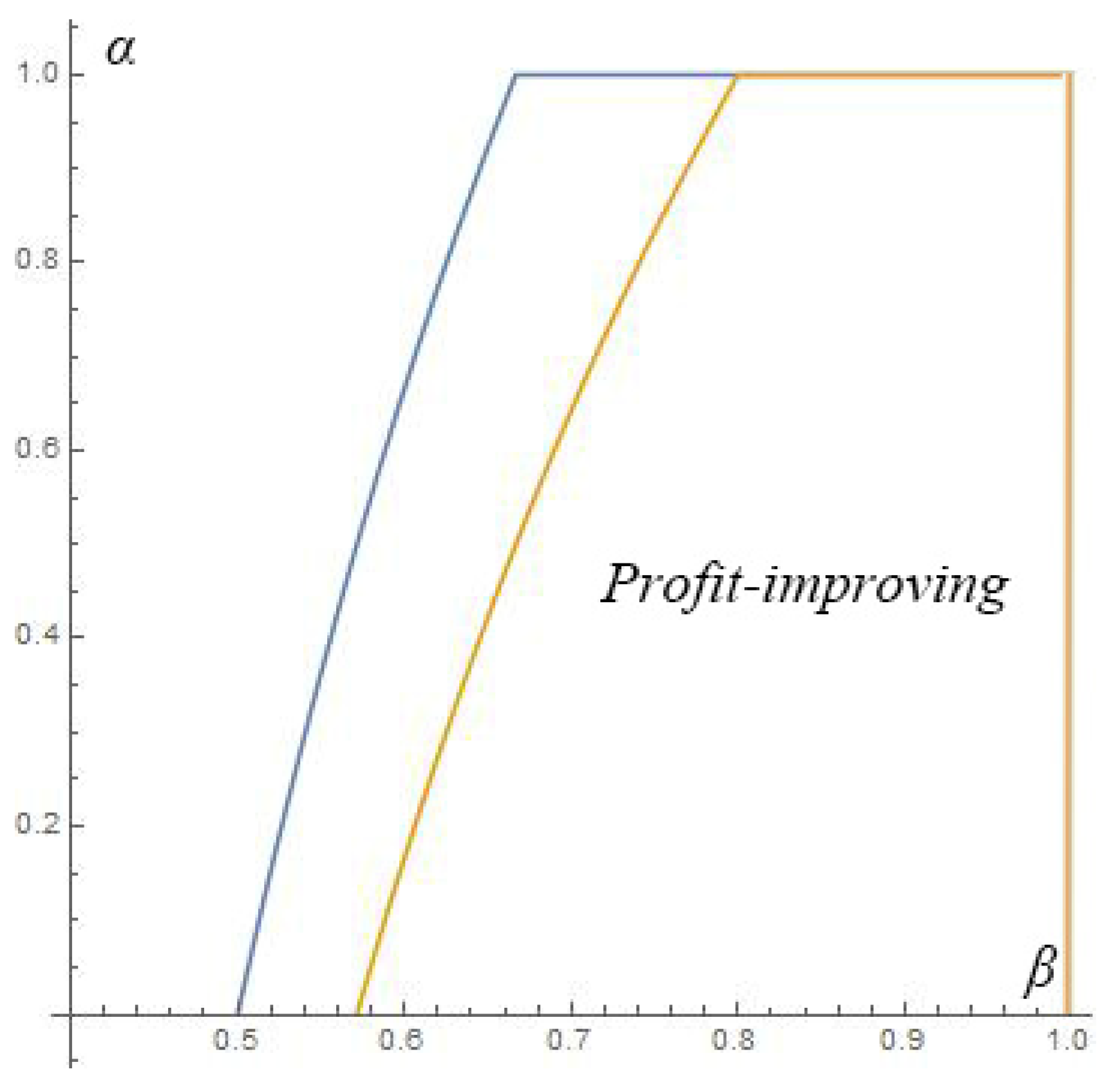

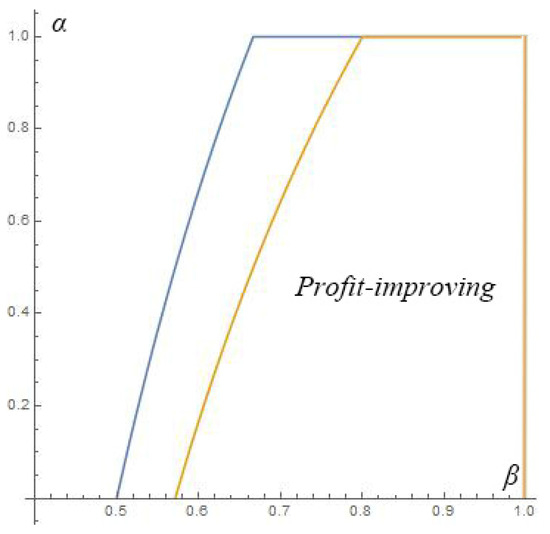

From the perspective of the upstream firm’s profit, it is shown in Figure 1 that , if . The improvement of a firm’s own profit depends on the firm’s bargaining power and emphasis on consumer welfare.

Figure 1.

The region of privately beneficial CSR in the global economy.

Proposition 4 implies that CSR initiatives can benefit the consumer-friendly foreign firm’s profitability, consumer surplus and social welfare at the same time, realizing a “win–win–win” situation. Additionally, the upstream firm enjoying a greater status in terms of wholesale-price bargains may have more of an incentive to implement CSR, as it enhances the firm’s own profits. Especially, if , as long as lies in , the profitability of the consumer-friendly firm will be improved by its CSR initiatives.

In this paper, we aim to find foreign manufacturers’ motivation to care about consumer well-being. In Figure 1, even though the initial process of undertaking CSR can be costly, in the future, perhaps due to the reputation accumulated by persistent consumer-friendly behaviors, it is helpful for the firm to win more bargaining power, which probably raises profits. Referring to the definition in Carroll and Shabana [4], this proposition may provide a theoretical rationale for a foreign firm’s CSR initiatives and connect consumer-oriented CSR with competitiveness.

Proposition 5.

The consumer-friendly action implemented by the foreign upstream firm leads to adequate consumer welfare and social welfare, which mitigates the government’s political hostility.

Proof.

We find that, if , which substantially reflects an increase in a firm’s emphasis on CSR, the government tends to lower the trade barrier and provide more subsidies. □

Our result is complementary to that of Chang et al. [15], stating that a higher foreign upstream firm’s CSR initiative will reduce the trade barriers of the local government. Since it is shown that a foreign upstream firm’s CSR initiative is beneficial for both consumer and social welfare in the home country, the government may support more consumer-friendly foreign firms by applying a moderate trade policy. Proposition 5 provides a theoretical logic for the somewhat puzzling experimental findings of a correlation between CSR initiatives and tariff aggressiveness, such as that of Laguir et al. [24].

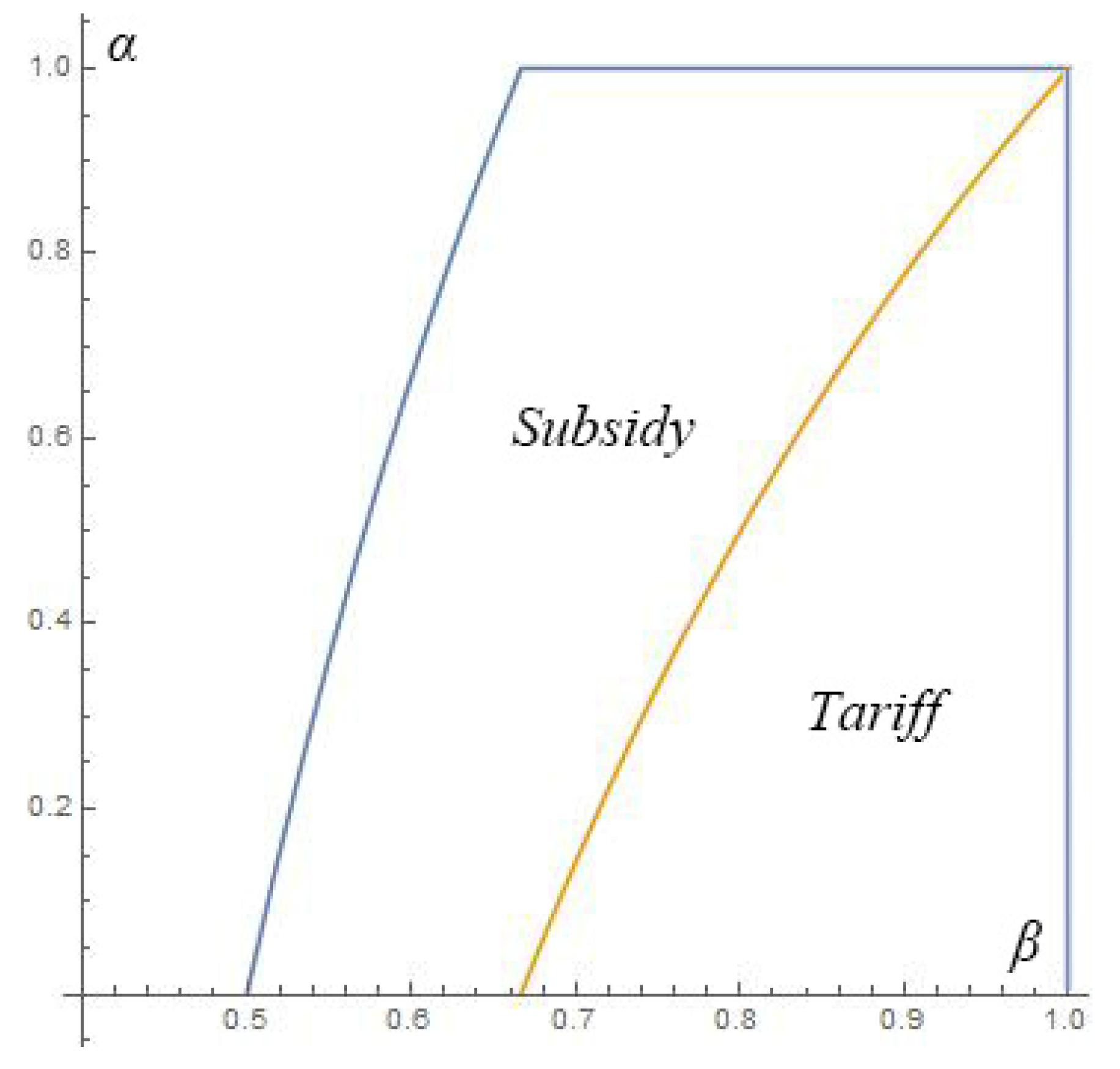

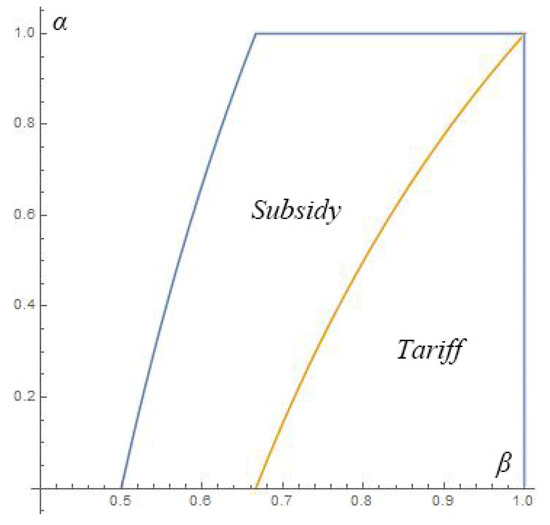

Intuitively, the extent of a strategic trade policy depends on an upstream firm’s bargaining power and its CSR initiative, which can be seen in Figure 2. Considering the situation when , we find that the home country should implement import subsidies according to social welfare maximization. When the upstream firm enjoys a high level of bargaining power but its emphasis on CSR is insufficient, explicitly, , then : the optimal strategic policy is import tariffs. As grows larger and is observed by the government, the home country will gradually lower the import tariff rate and further begin to provide import subsidies after reaching a critical value of . Note that, especially when , there will be no government role, as . In particular, if the profit-maximizing foreign upstream firm’s bargaining power is , without consumer-oriented concerns, a strategic trade policy becomes unnecessary, and the invisible hand will lead to an optimal situation from the perspective of social welfare.

Figure 2.

Strategic trade policy.

5. Conclusions

This paper investigates the impact of a foreign manufacturer’s consumer-oriented corporate social responsibility in a bilateral monopoly with wholesale price bargaining and provides some crucial welfare implications. Firstly, in the case of free trade, a consumer-friendly initiative is often costly for the upstream firm. An increase in the firm’s emphasis on consumer welfare reduces its own profit, which does not seem to be practicable for a privately beneficial solution. We find that a foreign firm’s consumer-friendly behavior achieves a higher consumer surplus and social welfare, contributing to tremendous social progress. Secondly, when we extend this model in the global economy context with the home country’s strategic trade policy, great possibilities for a “win–win–win” solution are shown, where a firm’s profitability, consumer surplus and social welfare are all improved. The foreign upstream firm may have more of an incentive to implement CSR as a quid pro quo device. Specifically, the consumer-friendly initiative taken by a foreign upstream firm leads to an adequate consumer surplus and social welfare, which can mitigate the government’s political hostility.

The policy implication of our framework shows that if the bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm is relatively large, a positive import tariff is needed to extract the rent of the foreign upstream and enhance social welfare. With the high bargaining power of the foreign upstream firm and the low weight of the consumer-friendly upstream firm, the government should set a high tariff rate for the foreign upstream firm to extract rent and enhance social welfare.

Our model in this paper provides a theoretical rationale for the somewhat puzzling experimental findings on CSR initiatives. The welfare analysis reflects some important policy implications for the government when cultivating consumer-friendly manufacturers. The limitations of this paper are that we assume a simple bilateral monopoly; in the real world, there could be many downstream firms that compete in the final market and the third-country market. In a future study, we may examine CSR-initiative firms and trade liberalization policy in a third-country model, in which there is cross ownership between exporters or a portion of the exporting firms’ equities owned by domestic investors, and see how CSR firms affect the strategic trade policy adopted by the importing country For example, Buccella and Fanti [25] show that the implementation of a strategic trade policy in the form of a tax (subsidy) when goods are differentiated (complements) is Pareto-superior to free trade within precise ranges of firms’ cross-ownership. Lee et al. [26] prove that when the portion of the exporting firm’s equities owned by domestic investors is symmetric, the optimal trade policy may be an import subsidy, and the importing country will provide a higher subsidy on the exporting firm, with a lower cost of production).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-S.C., C.-S.T. and C.C.; Methodology, S.-S.C. and C.-S.T.; Software, C.C.; Formal analysis, C.-S.T.; Writing—original draft, S.-S.C., C.-S.T. and C.C.; Writing—review and editing, S.-S.C. and C.-S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.C. R&D Policy Involving Consumer-friendly Strategy: Cooperative and Non-Cooperative R&D. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2016, 16, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Caroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, J. “Globalization” and Vertical Structure. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Corts, K.S. The Strategic Effects of Vertical Market Structure: Common Agency and Divisionalization in the US Motion Picture Industry. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2001, 10, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T.; Hosken, D.S. The Economic Effects of the Marathon-Ashl and Joint Venture: The Importance of Industry Supply Shocks and Vertical Market Structure. J. Ind. Econ. 2007, 55, 419–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.F.S. Vertical Product Differentiation, Managerial Delegation and Social Welfare in a Vertically-Related Market. Math. Soc. Sci. 2021, 113, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, G.E. Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Channel Coordination. Res. Econ. 2012, 66, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, G.E. The Profit-maximizing Case for Corporate Social Responsibility in a Bilateral Monopoly. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2014, 35, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.; Grothe, M. Social Responsibility in a Bilateral Monopoly. J. Econ. 2015, 115, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchida, Y. Cooperative choice of corporate social responsibility in a bilateral monopoly model. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, L.; Buccella, D. Social Responsibility in a Bilateral Monopoly with Downstream Convex Technology. J. Ind. Compet. Trade 2020, 20, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.F.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhao, L. Tariff Policy and Welfare in an International Duopoly with Consumer-friendly Initiative. Bull. Econ. Res. 2012, 64, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.M.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang LF, S.; Wu, S.J. Corporate Social Responsibility and International Competition: A Welfare Analysis. Rev. Int. Econ. 2014, 22, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, L.; Buccella, D. Strategic Trade Policy with Socially Concerned Firms. Int. Rev. Econ. 2020, 67, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan, T.F.; Reiss, P.C. Dealer and Manufacturer Margins. RAND J. Econ. 1985, 16, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, G. Pass-through, Vertical Contracts, and Bargains. Econ. Lett. 2016, 139, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, H.; Wolinsky, A. Bilateral Monopolies and Incentives for Merger. RAND J. Econ. 1988, 19, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, J.J. Vertical Integration and Antitrust Policy. J. Political Econ. 1950, 79, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, J.A.; Spencer, B.J. Tariff Protection and Imperfect Competition. In Monopolistic Competition and International Trade; Kierzkowski, H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kopel, M.; Brand, B. Socially Responsible Firms and Endogenous Choice of Strategic Incentives. Econ. Model. 2011, 29, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulow, J.I.; Pfleiderer, P. A Note on the Effect of Cost Changes on Prices. J. Political Econ. 1983, 91, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguir, I.; Staglianò, R.; Elbaz, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility affect Corporate Tax Aggressiveness? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccella, D.; Fanti, L. Strategic Trade Policy with Interlocking Cross-Ownership. J. Econ. 2021, 134, 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Wang, L.F.S. Foreign Ownership and Optimal Discriminatory Tariffs under Oligopolistic Competition. Econ. Internazionale 2021, 74, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).