Abstract

This paper examines the idea that adherence to social rules is in part driven by moral emotions and the ability to recognize the emotions of others. Moral emotions like shame and guilt produce negative feelings when social rules are transgressed. The ability to recognize and understand the emotions of others is known as affective theory of mind (ToM). ToM is necessary for people to understand how others are affected by the violations of social rules. Using a laboratory experiment, individuals participated in a rule-following task designed to capture the propensity to follow costly social rules and completed psychometric measures of guilt, shame, and ToM. The results show that individuals who feel more shame and have higher ToM are more likely to follow the rules. The results from this experiment suggest that both shame and ToM are important in understanding rule-following.

JEL Classification:

C70; C90; D60; D91

1. Introduction

Everyday life is filled with social norms that influence individual decision making. Social norms have been found to be important in understanding a wide range of human behavior including: Cooperation in collective action problems [1], helping behavior in the workplace [2], worker lateness [3], and tipping [4]. Theoretical models of social norm adherence often posit that an individual’s utility is directly influenced by norms [5,6,7,8,9]. Crucial to these models is the assumption that when faced with the same decision problem, individual actions can differ depending on individual differences in the propensity to follow social norms. Recent research, has shown that rule-following behavior is an important factor in understanding social norms [8]. This difference in propensity to follow rules can explain why some individuals choose to follow norms while others do not [8,9]. However, less is known about why individuals differ in the propensity to follow individual costly rules.

This paper adds to the literature by proposing and testing two potential sources explaining individual differences in rule-following. The first potential explanation for individual heterogeneity in rule-following could be due to differences in the intensity that people feel moral emotions. Two powerful moral emotions are guilt and shame. Both guilt and shame are negative affective states that may activate in individuals when they transgress social rules. To avoid these negative feelings, people choose actions that are consistent with socially acceptable behavior. The second potential explanation is awareness of how transgressing rules may affect others. The ability to understand others emotions, thoughts, and beliefs is known as theory of mind (ToM). Higher ToM may make individuals more likely to recognize how others would feel about their actions [10]. This recognition could lead higher ToM types to be more likely to follow rules.

In this paper, I ask: How do differences in both the propensity to feel moral emotions and the ability to recognize the emotions of others impact whether individuals follow costly rules? Using psychometric measures of individual propensities to feel shame, guilt, and ToM, I examine how subject differences in these moral emotions influence behavior in a costly rule-following task. Results show that guilt was not predictive of behavior; however, both shame and ToM were. Individuals who reported feeling higher levels of shame and ToM were significantly more likely to follow the rules.

2. Prior Literature

Guilt and shame are negative emotions that humans often experience. Shame and guilt are typically used as synonyms in both everyday life and academic research. However, researchers have argued that there exists key differences between the two affective states [11,12,13,14,15]. One approach has centered on the distinction between the self and behavior [11,13]. Individuals experiencing guilt often focus on a specific behavior (“I did something bad”), but when experiencing shame focus on their individual self (“I am a bad person”). A separate approach attempts to distinguish guilt and shame based on whether a transgression is observed by others or not. This public versus private distinction suggests that guilt is activated when a transgression is private whereas shame is activated when others are aware of the transgression [11,13]. Recent research suggests that these different distinctions are complementary [15,16]. Cohen et al. [15], Wolf et al. [16] present evidence that shame tends to be strongly related to situations that are public and that when experiencing shame people tend to make negative judgments about their self. Similarly, guilt appears to be strongly correlated with situations that are private and when experiencing guilt people tend to make negative judgments about their behavior.

Feelings of guilt and shame are likely to be activated when a person violates a rule or norm. Individuals may attempt to avoid actions that may make them feel guilt or shame. Game theoretic models using psychological game theory have attempted to capture feelings of guilt by proposing that people may be guilt averse [17,18]. Individuals try to avoid decisions that they believe will make them feel guilty. The above discussion suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Higher levels of rule-following will be associated with a higher propensity to feel shame.

Hypothesis 2.

Higher levels of rule-following will be associated with a higher propensity to feel guilt.

In order to measure guilt and shame, this paper uses the guilt and shame proneness scale (GASP) [15]. The scale has been used in a number of studies to measure individual differences in the propensity to feel guilt and shame. Howell et al. [19] used the GASP and found that individuals who had higher guilt proneness were more likely to report a general willingness to apologize to others. No correlation was found for shame proneness as measured by the GASP. Bracht and Regner [20] find that individuals who scored higher in guilt proneness where more pro-social in the mini-trust game. Jordan et al. [21] found that guilt proneness was not related to self-forgiveness, but positively related with forgiving others. In addition, shame proneness was negatively related to forgiving oneself and others. While Carpenter et al. [22] found that guilt-proneness was positively associated with forgiving oneself while shame-proneness was negatively associated with self-forgiveness. These findings may be a potential reason why shame avoidance may be powerful in public settings as people who feel great shame are less likely to forgive themselves for transgressions. Ent and Baumeister [23] found that people higher in guilt proneness, as measured by the GASP, valued harm avoidance more than obedience to authority and were more likely to disobey the experimenter to alleviate suffering of another individual. Arli et al. [24] find that people who feel higher guilt and shame are less likely to report that they engage in unethical consumer behavior.

While individual differences in the propensity to feel moral emotions may influence behavior, in game theoretic situations it is also important to predict the behavior of others. The ability of understand what others will do in game theoretic situations depends crucially on the ability to recognize the others utility function and their beliefs. This ability is known as ToM and typically after the age of five children are often described as having ToM [25,26]. ToM is often described as a discrete phenomenon where a person either possesses it or has a deficit. However, research has shown even in non-clinical adult populations there can be substantial variation in ToM ability [25,26,27]. One issue in prior research on individual differences in ToM is that measures of ToM often exhibit ceiling effects making it difficult to observe any heterogeneity in ToM ability [27]. However, more advanced ToM measures designed for adult populations show substantial variation in ToM [25,27]. For example, individuals on the autism spectrum often exhibit lower ToM ability [25], females typically manifest slightly higher ToM ability compared to males [28], and there is wide variation in ToM in non-clinical populations [25,26,27].

Previous research has suggest that ToM helps individuals recognize gains from cooperation and predict the behavior of others [10,29,30]. Research on children and adolescents has found differences in judgments about the social appropriateness of actions between those with and without autism [31]. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI), Berthoz et al. [32] found increased activation in areas in the brain thought to be responsible for ToM when subjects read stories about norm violations. Higher ToM ability may make individuals more likely to recognize how others would feel about their actions [10]. This recognition could lead individuals to empathize with others. Prior research has shown that greater empathy is associated with increases in following prosocial norms [33,34]. Taken together, prior research suggests that people who have higher ToM ability may to be less likely to transgress norms. This suggests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Higher levels of rule-following will be associated with higher affective ToM ability.

To measure affective ToM ability, this paper uses the reading the mind in the eyes test (RMET) [25]. The RMET has been used in numerous studies to measure individual differences in advanced ToM ability in the adult population. Researchers examining the relationship between RMET and individual behavior have examined trading markets [35,36], incentives [26], and strategic sophistication [37].

3. Experimental Design

From a large public United States university, a total of 329 students (62% female and 59% native English speaker) participated in an experiment. Recruitment for participants took place by randomly inviting students from a large subject pool. There were a total of 14 experimental sessions and no subject participated in more than one session. Upon arriving to the session, students were randomly assigned to a computer terminal. To facilitate data collection, the experiment was programmed and conducted with the software z-Tree [38]. Each session took approximately twenty-five minutes to complete with each subject received a $7 show up payment for their participation. This $7 was in addition to any potential earnings in the experiment. Including the show up payment subjects took home an average of $10.77.

3.1. Rule-Following Measure

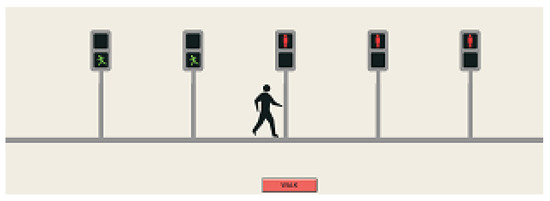

In part one of the experiment each subject participated in the rule-following task. The rule- following task was designed to capture individual sensitivity to social norms or rule-following [8]. In the task, each subject had the ability to control a figure that walked from the left to the right side of the screen. As the figure moved across the screen, the figure stopped at a traffic light automatically. In the task, there were a total of five traffic lights. At any time, subjects were aware that they could begin walking again by pressing the walk button. The traffic light was red but after five seconds the light would turn green. Similar to Ridinger [9], subjects started the rule-following task with $7 and were told that for each second they spent on the task they would loose $0.07.1 If subjects did not wait at any lights, then it would take total of 24 s to reach the end of the screen. In that case, subjects that did not wait at any lights would loose at least $1.68. Subjects who chose to wait the entire five seconds at each light lost $3.43. Following Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8], subjects were told “The rule is to wait at each stop light until it turns green.” A screenshot of the rule-following task can be seen in Figure 1.2

Figure 1.

Example of Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8] rule-following task.

In essence, the rule-following task presents an opportunity where a person could follow a rule but adherence to that rule is costly. Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8] compared conditions in the rule-following task when subjects were given the rule to wait and when subjects were not given the rule. The results showed that the stated rule significantly increases rule-following behavior. The time that subjects took to complete the task can be viewed as a measure of an individuals sensitivity to following rules or social norms. This measure has been shown to predict behavior in a number of experimental games [8,9].3 Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8] suggest as well that it may be important to control for differences in culture as the appropriateness of a given rule or norm may differ across cultures.

3.2. Affective ToM Measure

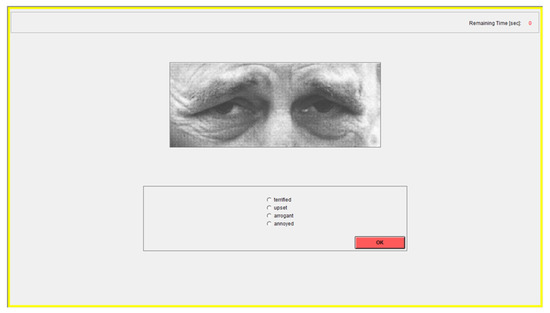

In part II, subjects completed the RMET [25]. The RMET is a measure of affective ToM and consists of a series of 36 individual pictures of the area around a person’s eyes. Each photograph is accompanied by four words (see Figure 2). Subjects chose the word that best describes what the person is thinking or feeling. Each question was answered without feedback. Subjects were provided with a printed handout of word definitions for all the words used in the task. The RMET has been shown to be a consistent measure of affective ToM ability and used in wide range of studies [25,26,28,39,40]. Performance on the RMET has been shown to vary due to age [41], gender [28], intelligence [42], and culture [43]. Prior work has show that controlling for these factors is important when using the RMET measure [26].

Figure 2.

Example of reading the mind in the eyes test (RMET) question

3.3. Questionnaire

In part III, subjects completed a questionnaire which included demographic questions, the cognitive reflection task, and the GASP scale. The demographic questions included gender, age, and whether the person was a native English speaker. To control for differences in cognitive ability, subjects completed the cognitive reflection task (CRT) [44]. The GASP scale was designed to measure feelings of guilt and shame [15].

The GASP consists of a series of statements where individuals indicate on a seven point likert scale the likelihood that they would react in the way described.4 The four statements in the guilt negative-behavior-evaulation (guilt-NBE) sub-scale attempt to measure the degree in which individuals feel guilty about private transgressions. An example of one of the guilt-NBE statements is “After realizing you have received too much change at a store, you decide to keep it because the salesclerk doesn’t notice. What is the likelihood that you would feel uncomfortable about keeping the money?” The four statements in the shame negative-self-evaluation (shame-NSE) sub-scale are designed to assess how much individuals feel shame about public transgressions. An example of one of the shame-NSE statements is “You give a bad presentation at work. Afterwards your boss tells your coworkers it was your fault that your company lost the contract. What is the likelihood that you would feel incompetent?” This public versus private distinction is an important difference between whether someone is experiencing feelings of guilt or shame. While guilt and shame may be different moral emotions, they are nevertheless very similar and the two sub-scales have been shown to be highly correlated [15].5

The GASP scale also includes two additional sub-scales that measure shame withdraw and guilt repair. The shame-withdraw sub-scale measures the propensity to avoid future interactions after a shame inducing event. The guilt repair sub-scale measures the likelihood that a person would take future actions to change their behavior after experiencing guilt. Both guilt-NBE and shame-NSE measure feelings about a transgression and anticipation of those negative feelings may influence rule-following. In contrast, both shame-withdraw and guilt-repair measure future actions after a transgression has occurred. It is less clear that these measures are capturing the anticipated feelings of guilt and shame that theoretically could influence rule-following. For completeness, all sub-scales were included and regressions for the shame-withdraw and guilt-repair sub-scales are included in the Appendix A (See Table A3).

3.4. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the name and description for each variable used in the subsequent analysis. Table 2 presents the summary statistics for the psychometric scales and demographic information. Both Shame-NSE and Guilt-NBE were generated by adding subjects scores from the respective GASP sub-scale. Larger numbers indicated greater shame and guilt proneness. The RMET is equal to the number of questions where subjects selected the correct word that best describes what the person in the image was thinking or feeling.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

Table 2.

Summary statistics.

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients for the dependent variables used in subsequent analysis. As found in prior work, both Shame-NSE and Guilt-NBE are highly correlated [15]. Scores on the RMET are positively and significantly correlated with Shame-NSE but not with Guilt-NBE. While positive, in contrast to prior studies [28], females did not score significantly higher on RMET in this study.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients.

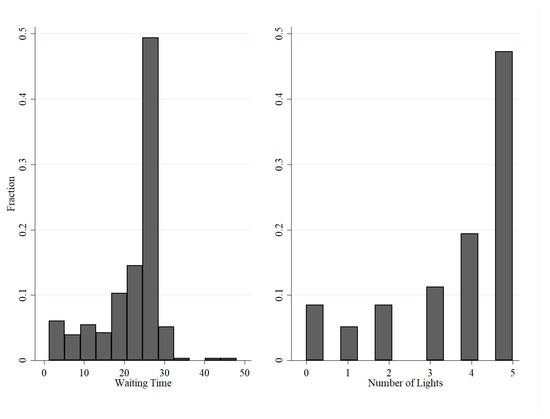

Waiting Time is equal to the total time that subjects waited at each light. Prior research has used waiting time as the measure of the propensity to follow rules [8,9]. The use of waiting time allows for a direct comparison to prior studies using the rule-following task. One potential drawback of the waiting time measure is that it may be influenced by reaction times and these reaction times may introduce noise unrelated to rule-following behavior. To control for this, analysis is also conducted using the variable Number of Lights. Number of Lights is equal to the number of lights that subjects waited at until the light turned green. In essence, the variable measures the number of times subjects followed the rule. Figure 3 shows plots histograms for both the Waiting Time and Number of Lights measures. The distribution of the waiting time measure is similar to prior studies [8,9].

Figure 3.

Histogram of behavior in the rule-following task. Note: Waiting Time is measured as the total number of seconds that a subject waited at each of the five lights. Number of Lights is equal to the number of lights subjects waited at until the light turned green.

4. Results

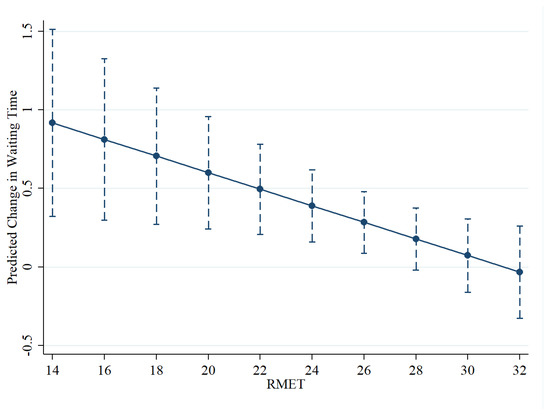

Table 4 presents regression results using ordinary least squares to predict Waiting Time in the rule-following by measures of Shame-NSE, Guilt-NBE, and ToM. The regressions in columns (1) to (3) show that both task in shame and RMET are correlated with waiting time in the rule-following task. The longer subjects waited the more money they lost, but were told that the rule was to wait until the light turned green. Higher scores in shame significantly increased the amount of time subjects waited at the light. Guilt was not significantly correlated with rule-following. The RMET measure is positive and significant at the 5% level. This suggests that affective theory of mind may be related to rule-following. The regressions in columns (4) to (6) are similar to the regressions in columns (1) to (3) except they include additional control variables. The results show that the estimated coefficients for Shame-NSE, Guilt-NBE, and RMET on predicting Waiting Time in the rule-following task are similar even when controlling for demographic information and CRT scores. Since Shame-NSE and RMET scores are positively correlated, it is possible that their effects on rule-following are not independent. Columns (7) and (8) show the results of regressions with both measures. When included in the same regression, the coefficients for both Shame-NSE and RMET remain positive and significant. Column (8) includes an interaction between shame and ToM. This interaction is significant at the 5% level and negative. This suggests at higher levels of shame and ToM, increases have diminishing marginal returns on rule-following. Due to the interaction variable between Shame-NSE and RMET in column (8), the estimated marginal effect of a unit change in Shame-NSE on predicting Waiting Time can differ depending on the value of the RMET. Figure 4 plots the marginal effects of a unit change in Shame-NSE on predicting Waiting Time across a range of RMET scores. The figure shows that increases in shame at lower levels of ToM have a greater marginal increase in Waiting Time compared to when RMET scores are high. This suggests ToM and Shame may be substitutes in increasing rule-following behavior. Taken together, these results suggest that higher feelings of shame and ToM are correlated with greater rule-following adherence.

Table 4.

Predicting waiting time by shame, guilt, and theory of mind (ToM): Regression results.

Figure 4.

Marginal effects of change in shame negative-self-evaluation (shame-NSE) on waiting time at different RMET scores. Note: This figure uses the regression results from column (8) in Table 3 which included the interaction variable Shame-NSE X RMET. Marginal effects of a unit change of Shame-NSE on Waiting time was calculated by taking the derivative with respect to Shame-NSE and estimating this effect at different RMET Scores. Dashed lines indicate 95% Confidence Intervals.

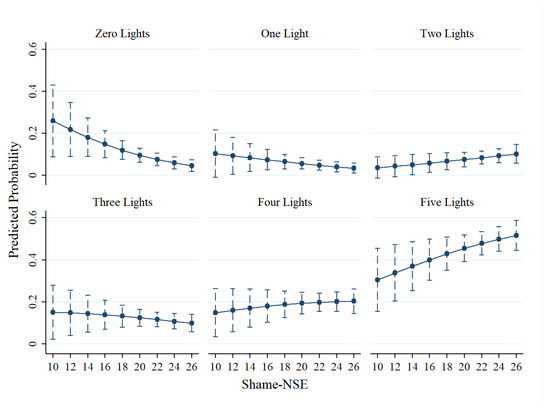

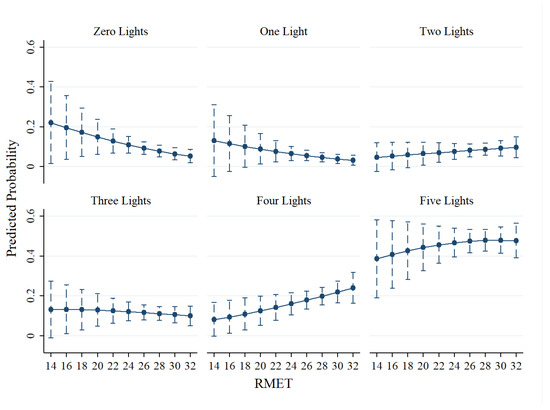

An alternative measure of behavior in the rule-following task is to use the number of times subjects waited at the light for the entire five seconds. To analyze this dependent variable, multinomial logit regressions were conducted (See Table A4, Table A5, Table A6).6 Table 5 presents the marginal effects of a unit change in Shame-NSE, Guilt-NBE, and RMET on the Number of Lights variable. An increase in one standard deviation for Shame-NSE is associated with a 4.79 percentage point decrease in the probability a subject would choose to wait at zero lights. While an increase in one standard deviation for Shame-NSE is associated with a 4.79 percentage point increase in the probability a subject would wait at all five lights. A similar pattern can be seen in Figure 5 which plots the predicted probability for each choice of lights at different levels of shame. Taken together, higher levels of shame are associated with a reduction in choosing to wait at zero or one light and an increase in perfect rule-following behavior. Measures of Guilt-NBE were not significant at predicting any choice in the number of lights. An increase in one standard deviation for RMET was associated with a 2.69 percentage point decrease in the probability a subject chose to wait at zero lights. A similar pattern can be seen in Figure 6 which plots the predicted probability for each choice of lights at different levels of the RMET. Taken together, higher ToM is associated with a decrease in subjects choosing to never wait at any light or only waiting at a single light. The results support Hypotheses 1 and 3 but Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

Table 5.

Predicting number of lights by shame, guilt, and ToM: Marginal effects.

Figure 5.

Predicted probability of number of lights by shame-NSE score. Note: This figure uses the multinomial logit regression results from Table A4. Dashed lines indicate 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 6.

Predicted probability of number of lights by RMET score with 95% confidence intervals. Note: This figure uses the multinomial logit regression results from Table A6. Dashed lines indicate 95% Confidence Intervals.

5. Conclusions

Social norms are thought to have a strong influence on human behavior [1,2,3,4]. Attempts to theoretically model adherence to social norms have often assumed that an individual’s utility is directly influenced by norms [5,6,7,8]. The propensity to follow social norms is an important part of the theoretical models, however, less is known about what individual differences may influence this propensity.

This paper tested the idea that moral emotions and the ability to recognize the emotions of others may be important determinants in explaining social norm adherence. The results show a significant correlation between shame proneness in rule-following. Differences in guilt were not found to influence behavior. As predicted, variations in affective ToM appeared were associated with rule adherence. Suggesting that the ability to understand the affective states of others may be an important factor in understanding individual differences in costly rule-following.

While shame was predictive of rule-following behavior, guilt was not significant. Prior research has argued that shame is more likely to be activated in public situations whereas guilt is more likely to be activated in private situations [11,13,15]. In the rule-following task, the decisions of individuals of whether or not to wait at the light are not observable to the other subjects. However, the actions that the individuals make are observable to the experimenter. If subjects think of their actions as observable to the experimenter, then shame may be a stronger influence on behavior. While both guilt and shame may have been activated in the rule-following task, it is possible that the effect of shame was stronger than guilt due to subjects viewing their behavior in the task as public. While the current study is unable to shed light on whether the public versus private distinction influenced behavior in this experiment, this question is a potential avenue for future research in studying the role of guilt and shame in influencing rule-following behavior.

While this study is correlational, it adds to our understanding of why individuals differ in the propensity to follow rules. The propensity to feel moral emotions and the ability to understand others’ emotions differs among individuals in the adult population. These differences may lead to variations in rule-following and adherence to social norms. Social norms are highly context specific with different settings leading to different behavior [5]. As a result, future research should investigate whether shame and ToM influence social norm adherence and rule-following in environments not examined in this study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Experimental Instructions and Additional Analysis

In part 1 of the experiment, subjects first completed the rule-following task. Figure A1 and Figure A2 show screenshots of the instructions viewed by subjects in the experiment. Table A1 and Table A2 provide the instructions and full scale items for the GASP scale. Table A3 reports results from Ordinary Least Squares regressions for the shame-withdraw and guilt-repair subscales. Table A4, Table A5, Table A6 present multinomial logit regressions predicting the number of lights subjects chose to wait the full five seconds. For each regression, the base variable is choosing to wait at zero lights. The reported coefficients are relative risk ratios with robust standard errors in parentheses.

Figure A1.

Experimental Instructions.

Figure A2.

Experimental Instructions: Rule-following Task.

Table A1.

Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale.

Table A1.

Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale.

| Instructions | Below, please read about situations that people are likely to encounter in day-to-day life, followed by common reactions to those situations. As you read each scenario, try to imagine yourself in that situation. Then indicate the likelihood that you would react in the way described. |

| Sub-scale | Item |

| Guilt-Negative- Behavior-Evaluation | (1) After realizing you have received too much change at a store, you decide to keep it because the sales clerk doesn’t notice. What is the likelihood that you would feel uncomfortable about keeping the money? |

| Guilt-Repair | (2) You are privately informed that you are the only one in your group that did not make the honor society because you skipped too many days of school. What is the likelihood that this would lead you to become more responsible about attending school? |

| Shame-Negative- Self-Evaluation | (3) You rip an article out of a journal in the library and take it with you. Your teacher discovers what you did and tells the librarian and your entire class. What is the likelihood that this would make you would feel like a bad person? |

| Shame-Withdraw | (4) After making a big mistake on an important project at work in which people were depending on you, your boss criticizes you in front of your coworkers. What is the likelihood that you would feign sickness and leave work? |

| Guilt-Repair | (5) You reveal a friend’s secret, though your friend never finds out. What is the likelihood that your failure to keep the secret would lead you to exert extra effort to keep secrets in the future? |

| Shame-Negative- Self-Evaluation | (6) You give a bad presentation at work. Afterwards your boss tells your coworkers it was your fault that your company lost the contract. What is the likelihood that you would feel incompetent? |

| Shame-Withdraw | (7) A friend tells you that you boast a great deal. What is the likelihood that you would stop spending time with that friend? |

| Shame-Withdraw | (8) Your home is very messy and unexpected guests knock on your door and invite themselves in. What is the likelihood that you would avoid the guests until they leave? |

For each scenario, participants answered using a seven-point likert scale: (1) Very Unlikely (2) Unlikely (3) Slightly Unlikely (4) About 50% Likely (5) Slightly Likely (6) Likely (7) Very Likely. Scores for each subscale were calculated by adding the scores for the four questions. Each subscale has a minimum value of 4 and maximum value of 28.

Table A2.

Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale: Continued.

Table A2.

Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale: Continued.

| Instructions | Below, please read about situations that people are likely to encounter in day-to-day life, followed by common reactions to those situations. As you read each scenario, try to imagine yourself in that situation. Then indicate the likelihood that you would react in the way described. |

| Sub-scale | Item |

| Guilt-Negative- Behavior-Evaluation | (9) You secretly commit a felony. What is the likelihood that you would feel remorse about breaking the law? |

| Shame-Negative- Self-Evaluation | (10) You successfully exaggerate your damages in a lawsuit. Months later, your lies are discovered and you are charged with perjury. What is the likelihood that you would think you are a despicable human being? |

| Guilt-Repair | (11) You strongly defend a point of view in a discussion, and though nobody was aware of it, you realize that you were wrong. What is the likelihood that this would make you think more carefully before you speak? |

| Shame-Withdraw | (12) You take office supplies home for personal use and are caught by your boss. What is the likelihood that this would lead you to quit your job? |

| Shame-Negative- Self-Evaluation | (13) You make a mistake at work and find out a coworker is blamed for the error. Later, your coworker confronts you about your mistake. What is the likelihood that you would feel like a coward? |

| Guilt-Negative- Behavior-Evaluation | (14) At a coworker’s housewarming party, you spill red wine on their new cream-colored carpet. You cover the stain with a chair so that nobody notices your mess. What is the likelihood that you would feel that the way you acted was pathetic? |

| Guilt-Repair | (15) While discussing a heated subject with friends, you suddenly realize you are shouting though nobody seems to notice. What is the likelihood that you would try to act more considerately toward your friends? |

| Guilt-Negative- Behavior-Evaluation | (16) You lie to people but they never find out about it. What is the likelihood that you would feel terrible about the lies you told? |

For each scenario, participants answered using a seven-point likert scale: (1) Very Unlikely (2) Unlikely (3) Slightly Unlikely (4) About 50% Likely (5) Slightly Likely (6) Likely (7) Very Likely. Scores for each subscale were calculated by adding the scores for the four questions. Each subscale has a minimum value of 4 and maximum value of 28.

Table A3.

Predicting Rule-following by Shame-Withdraw and Guilt-Repair: Regression Results.

Table A3.

Predicting Rule-following by Shame-Withdraw and Guilt-Repair: Regression Results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waiting Time | Waiting Time | Lights Waited | Lights Waited | |

| Shame-Withdraw | −0.12 | −0.03 | ||

| (0.09) | (0.02) | |||

| Guilt-Repair | 0.12 | 0.03 | ||

| (0.11) | (0.02) | |||

| Female | 3.74 | 3.34 | 0.66 | 0.58 |

| (0.89) | (0.89) | (0.12) | (0.20) | |

| Age | −0.15 | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.06) | (0.06) | |

| Native English | −1.47 | −1.09 | −0.20 | −0.12 |

| Speaker | (0.86) | (0.84) | (0.18) | (0.18) |

| CRT | −0.60 | −0.60 | −0.11 | −0.10 |

| (0.39) | (0.39) | (0.21) | (0.09) | |

| Intercept | 26.11 | 21.20 | 4.94 | 3.56 |

| (6.00) | (6.32) | (1.32) | (1.25) | |

| N | 329 | 329 | 329 | 329 |

| 0.07 | 0.07 | |||

| Pseudo- | 0.06 | 0.06 |

Regressions are Ordinary Least Squares with standard errors in parentheses. See Table 1 for variable descriptions. , .

Table A4.

Predicting Number of Lights by Shame: Multinomial Logit Regression.

Table A4.

Predicting Number of Lights by Shame: Multinomial Logit Regression.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Two | Three | Four | Five | |

| Light | Lights | Lights | Lights | Lights | |

| Shame-NBE | 1.04 | 1.19 | 1.09 | 1.15 | 1.16 |

| (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | |

| Female | 1.81 | 1.73 | 2.47 | 3.17 | 3.07 |

| (1.24) | (1.03) | (1.38) | (1.64) | (1.44) | |

| Age | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| (0.18) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.13) | (0.11) | |

| Native English Speaker | 2.70 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.81 | 0.96 |

| (2.05) | (0.58) | (0.64) | (0.39) | (0.43) | |

| CRT | 1.32 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| (0.38) | (0.23) | (0.17) | (0.18) | (0.16) | |

| N | 329 | ||||

| pseudo- | 0.04 |

Results are Multinomial Logit Regressions with robust standard errors in parentheses. Reported coefficients are relative risk ratios. Each estimated coefficient is relative to the base variable of waiting at zero lights. See Table 1 for variable descriptions. , .

Table A5.

Predicting Number of Lights by ToM: Multinomial Logit Regression.

Table A5.

Predicting Number of Lights by ToM: Multinomial Logit Regression.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Two | Three | Four | Five | |

| Light | Lights | Lights | Lights | Lights | |

| Guilt-NBE | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| (0.06) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | |

| Female | 1.96 | 2.18 | 2.66 | 3.84 | 3.68 |

| (1.34) | (1.28) | (1.49) | (1.97) | (1.71) | |

| Age | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| (0.18) | (0.15) | (0.15) | (0.13) | (0.11) | |

| Native English Speaker | 2.74 | 1.10 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 1.03 |

| (2.08) | (0.61) | (0.66) | (0.41) | (0.45) | |

| CRT | 1.36 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| (0.39) | (0.24) | (0.18) | (0.18) | (0.17) | |

| N | 329 | ||||

| pseudo- | 0.03 |

Results are Multinomial Logit Regressions with robust standard errors in parentheses. Reported coefficients are relative risk ratios. Each estimated coefficient is relative to the base variable of waiting at zero lights. See Table 1 for variable descriptions. , .

Table A6.

Predicting Number of Lights by ToM: Multinomial Logit Regression.

Table A6.

Predicting Number of Lights by ToM: Multinomial Logit Regression.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Two | Three | Four | Five | |

| Light | Lights | Lights | Lights | Lights | |

| RMET | 1.00 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.16 | 1.11 |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.07) | (0.07) | (0.06) | |

| Female | 2.04 | 2.19 | 2.83 | 3.71 | 3.82 |

| (1.37) | (1.28) | (1.55) | (1.89) | (1.75) | |

| Age | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| (0.17) | (0.15) | (0.14) | (0.12) | (0.11) | |

| Native English Speaker | 2.74 | 0.87 | 1.08 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| (2.10) | (0.50) | (0.58) | (0.32) | (0.37) | |

| CRT | 1.37 | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.83 |

| (0.40) | (0.23) | (0.17) | (0.17) | (0.16) | |

| N | 329 | ||||

| pseudo- | 0.04 |

Results are Multinomial Logit Regressions with robust standard errors in parentheses. Reported coefficients are relative risk ratios. Each estimated coefficient is relative to the base variable of waiting at zero lights. See Table 1 for variable descriptions. , , .

References

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Patil, S.V. Challenging the norm of self-interest: Minminor influence and transitions to helping norms in work units. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G. Influence of group lateness on individual lateness: A cross-level examination. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, O.H. The social norm of tipping: A review. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Perez, R. Aversion to norm-breaking: A model. Games Econ. Behav. 2008, 64, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.B.; Leider, S. Norms and contracting. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough, E.O.; Vostroknutov, A. Norms make preferences social. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2016, 14, 608–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridinger, G. Ownership, punishment, and norms in a real-effort bargaining experiment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2018, 155, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, T.; Fehr, E. The neuroeconomics of mind reading and empathy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H.B. Shame and Guilt in Neurosis; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Tagney, J.P.; Miller, R.S.; Flicker, L.; Barlow, D.H. Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A thoretical model. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagney, J.P.; Stuewig, J.; Mashek, D.J. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, T.R.; Panter, S.T.; Insko, C.A. Introduction the gasp scale: A new measure of guilt and shame proness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 947–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.T.; Cohen, T.R.; Panter, A.; Insko, C.A. Shame proneness and guilt proneness: Toward the further understanding of reactions to public and private transgressions. Self Identity 2010, 9, 337–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battigalli, P.; Dufwenberg, M. Dynamic psychological games. J. Econ. Theory 2009, 144, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Dufwenberg, M. Promises and partnership. Econometrica 2006, 74, 1579–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A.J.; Turowski, J.B.; Buro, K. Guilt, empathy, and apology. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracht, J.; Regner, T. Moral emotions and partnership. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Flynn, F.J.; Cohen, T.R. Forgive them for i have sinned: The relationship between guilt and forgiveness of others’ transgressions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.P.; Tignor, S.M.; Tsang, J.-A.; Willett, A. Dispositional self-forgiveness, guilt- and shame- proneness, and the roles of motivational tendencies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 98, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ent, M.R.; Baumeister, R.F. Individual differences in guilt proness affect how people respond to moral tradeoffs beetween harm avoidance and obedience to authority. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 74, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Leo, C.; Tjiptono, F. Investigating the impact of guilt and shame proneness on consumer ethics: A cross national study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “reading the mind in the eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with asperger syndrome or high-functiong austism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridinger, G.; McBride, M. Money affects theory of mind differently by gender. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodell-Feder, D.; Lincoln, S.H.; Coulson, J.P.; Hooker, C.I. Using fiction to assess mental state understanding: A new task for assessing theory of mind in adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkl, R.A.; Peterson, E.; Baker, C.A.; Miller, S.; Pulos, S. Meta-analysis reveals adult female superiority in “reading the mind in the eyes test”. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2013, 15, 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ridinger, G.; McBride, M. Theory of Mind Ability and Cooperation. Working Paper. Available online: https://economics.ucr.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/McBride-paper-for-1-31-18-seminar.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- McCabe, K.A.; Smith, V.L.; LePore, M. Intentionality detection and “mindreading”: Why does game form matter? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovel, K.A.; Pearson, D.A.; Tunali-Kotoski, B.; Ortegon, J.; Gibbs, M.C. Judgments of social appropriateness by children and adolescents with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 41, 367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz, S.; Armony, J.; Blair, R.J.R.; Dolan, R. An fmri study of intentional and unintentional (embarrassing) violations of social norms. Brain 2002, 125, 1696–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, D.; Griffith, J.; Durkin, K.; Maass, A. Empathy, group norms, and children’s ethnic attitudes. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 26, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nook, E.C.; Ong, D.C.; Morelli, S.A.; Mitchell, J.P.; Zaki, J. Prosocial conformity: Prosocial norms generalize across behavior and empathy. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruguier, A.J.; Quartz, S.R.; Bossaerts, P.L. Exploring the nature of “trading intuition”. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1703–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, B.D.; O’Doherty, J.P.; Ray, D.; Bossaerts, P.; Camerer, C. In the mind of the market: Theory of mind biases value computation during financial bubles. Neuron 2013, 80, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georganas, S.; Healy, P.J.; Weber, R.A. On the persistence of strategic sophistication. J. Econ. Theory 2015, 159, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. z-tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, O.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Hill, J. The cambridge mindreading (cam) face-voice battery: Testing complex emotion recognition in adults with and without asperger syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralva, T.; Kipps, C.M.; Hodges, J.R.; Clark, L.; Bekinschtein, T.; Roca, M.; Calcagno, M.L.; Manes, F. The relationship between affaffect decision-making and theory of mind in the frontal variant of fronto-temporal dementia. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Phillips, L.H.; Ruffman, T.; Bailey, P.E. A meta-analytic review of age differences in theory of mind. Psychol. Aging 2013, 28, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.A.; Peterson, E.; Pulos, S.; Kirkl, R.A. Eyes and iq: A meta-analysis of the relationship between intelligence and “reading the mind in the eyes”. Intelligence 2014, 44, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; Rule, N.O.; Franklin, R.G.; Wang, E. Cross-cultural reading the mind in the eyes: An fmri investigation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010, 22, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, S. Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | In Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8], subjects started €8 and were told they would lose €0.08 per second. |

| 2. | Screenshots of the instructions given to subjects in the experiment can be found in the Appendix A (See Figure A1 and Figure A2.) |

| 3. | As discussed in Kimbrough and Vostroknutov [8] and Ridinger [9], an alternative interpretation is that behavior in the task is capturing the experimenter demand effect. If subjects are choosing to earn less money in the experiment due to the experimenter demand effect, then that individual difference in following the experimenter demands is a difference in rule-following behavior. |

| 4. | |

| 5. | Cohen et al. [15] have shown that both sub-scales are reliable. For the data collected in this paper, Cronbach alpha measures for the guilt and shame subscale are 0.65 and 0.61, respectively. As noted in Cohen et al. [15], scenario-based measures typically have lower alphas and as such the GASP sub-scales of 0.60 are considered reliable. |

| 6. | Since the Number of Lights variable is ordered an alternative specification is to use standard ordered logit models. However, Brant tests show that the proportional odds assumption of the ordered logit models are violated. The multinomial logit results reported in the paper are similar to results using generalized ordered logit models which relax the proportional odds assumption. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).