Binding Contracts, Non-Binding Promises and Social Feedback in the Intertemporal Common-Pool Resource Game

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Findings

3. The Intertemporal CPR Game

Hypotheses

4. Experiment 1: Binding Contracts and Non-Binding Promises

4.1. Procedure

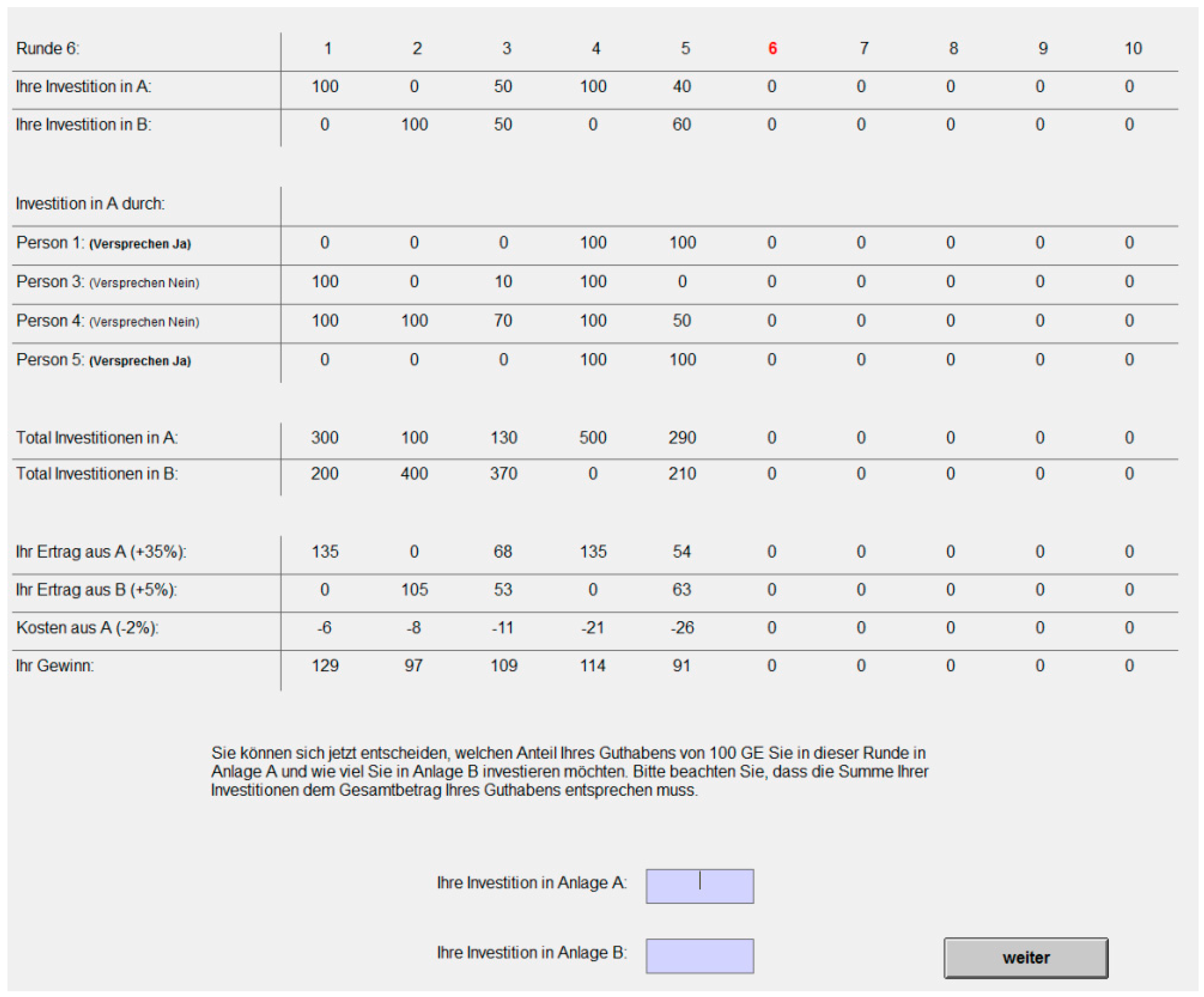

- In the no regulation condition, no further instructions were given to subjects;

- In the contract condition, subjects had to decide whether or not they wanted to sign a contract which, if signed unanimously, would authorize the computer to invest their whole endowment in Asset B in every round. Furthermore, they were made aware of two facts. They were told that if the contract was not signed by all subjects, they would be able to choose the amount they wanted to invest in Asset A or Asset B. They were also told that their decision to sign the contract or not would be displayed next to their number on the screen and would be visible to the other subjects in their group. The latter design feature allows for a better comparison of the contract condition and the promise condition, which is described next;

- In the promise condition, subjects had to decide whether or not they wanted to promise to invest their total endowment in Asset B in every round. Moreover, they were made aware of two facts. They were told that, irrespective of their decision, they would be able to choose the amount they wanted to invest in Asset A or Asset B. They were also told that their decision to make a promise or not would be displayed next to their number on the screen and would be visible to the other subjects in their group (see Figure A1 in the Appendix A).

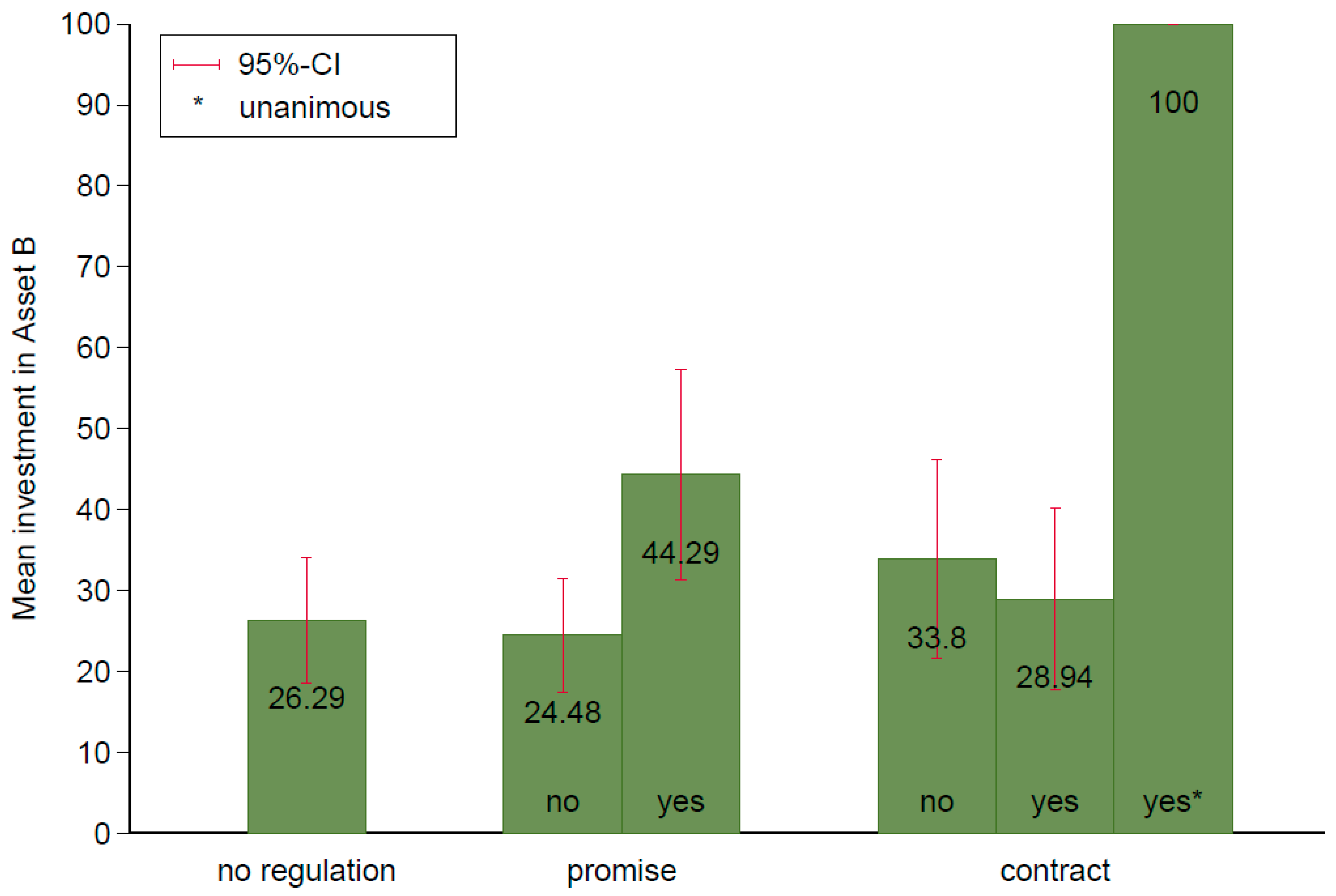

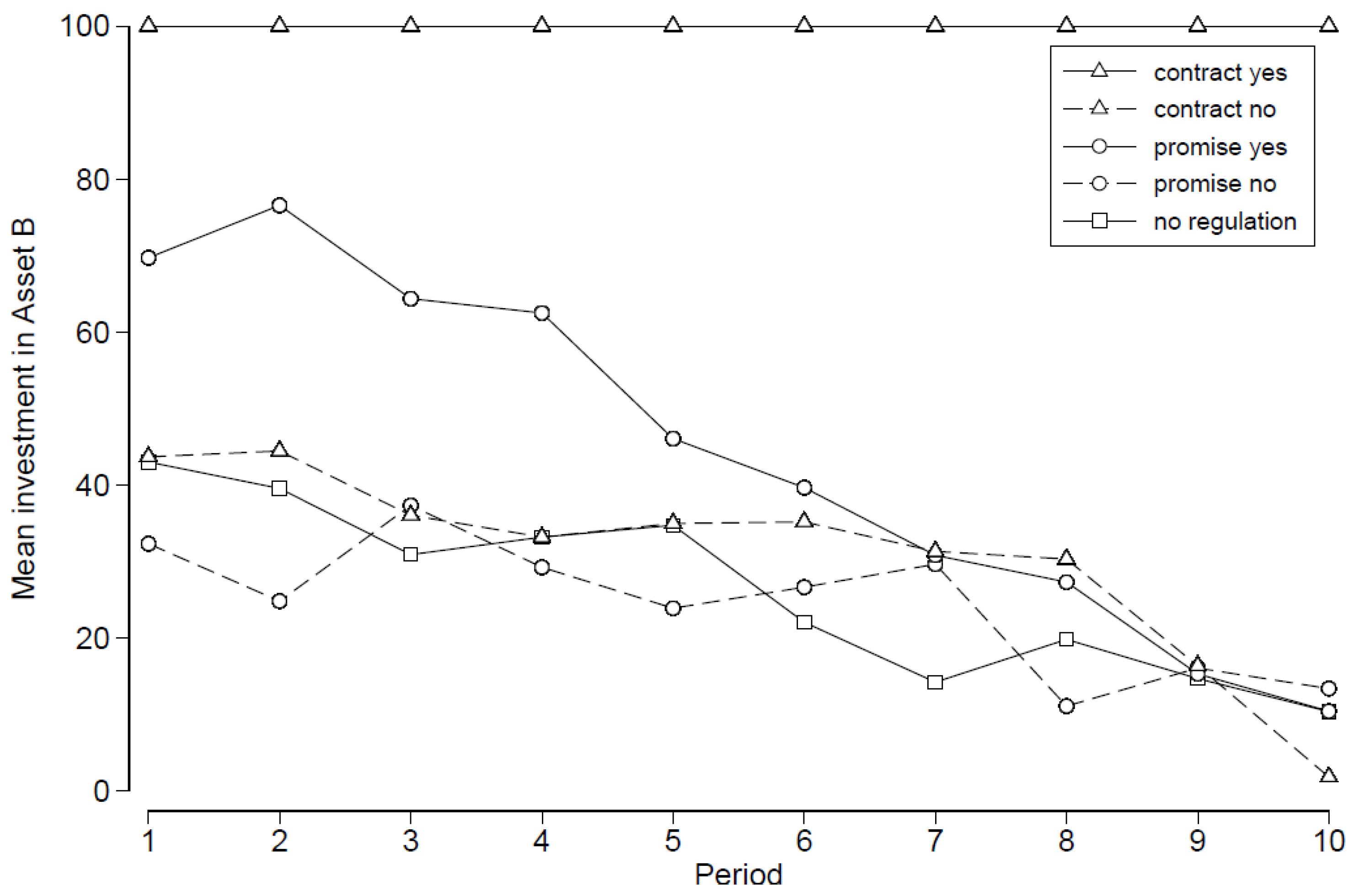

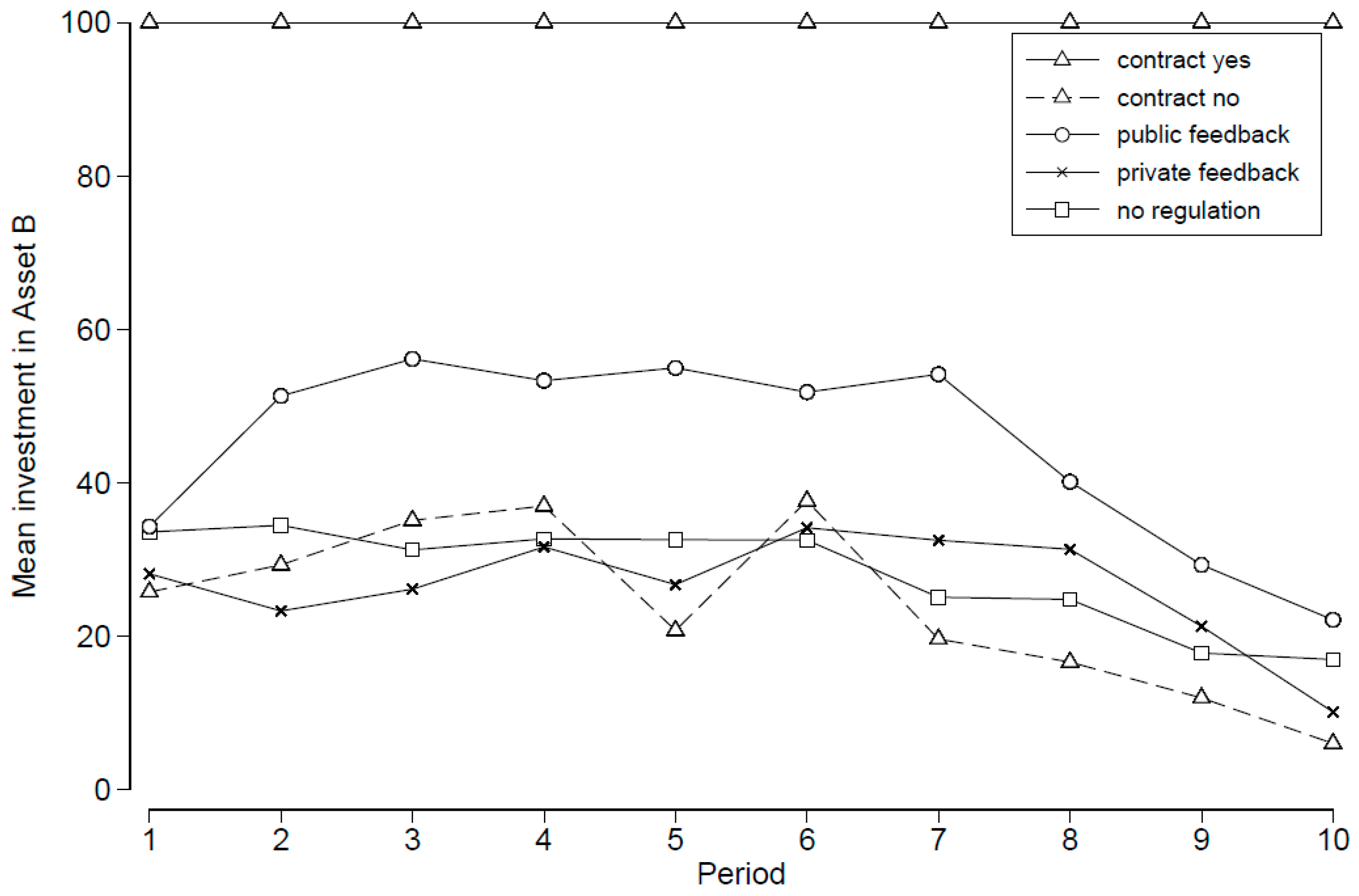

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. Experiment 2: Private and Public Social Feedback

5.1. Procedure

- In the no regulation condition, no further instructions were given to subjects;

- In the contract condition, subjects were given the same instructions as in the contract condition in the first experiment;

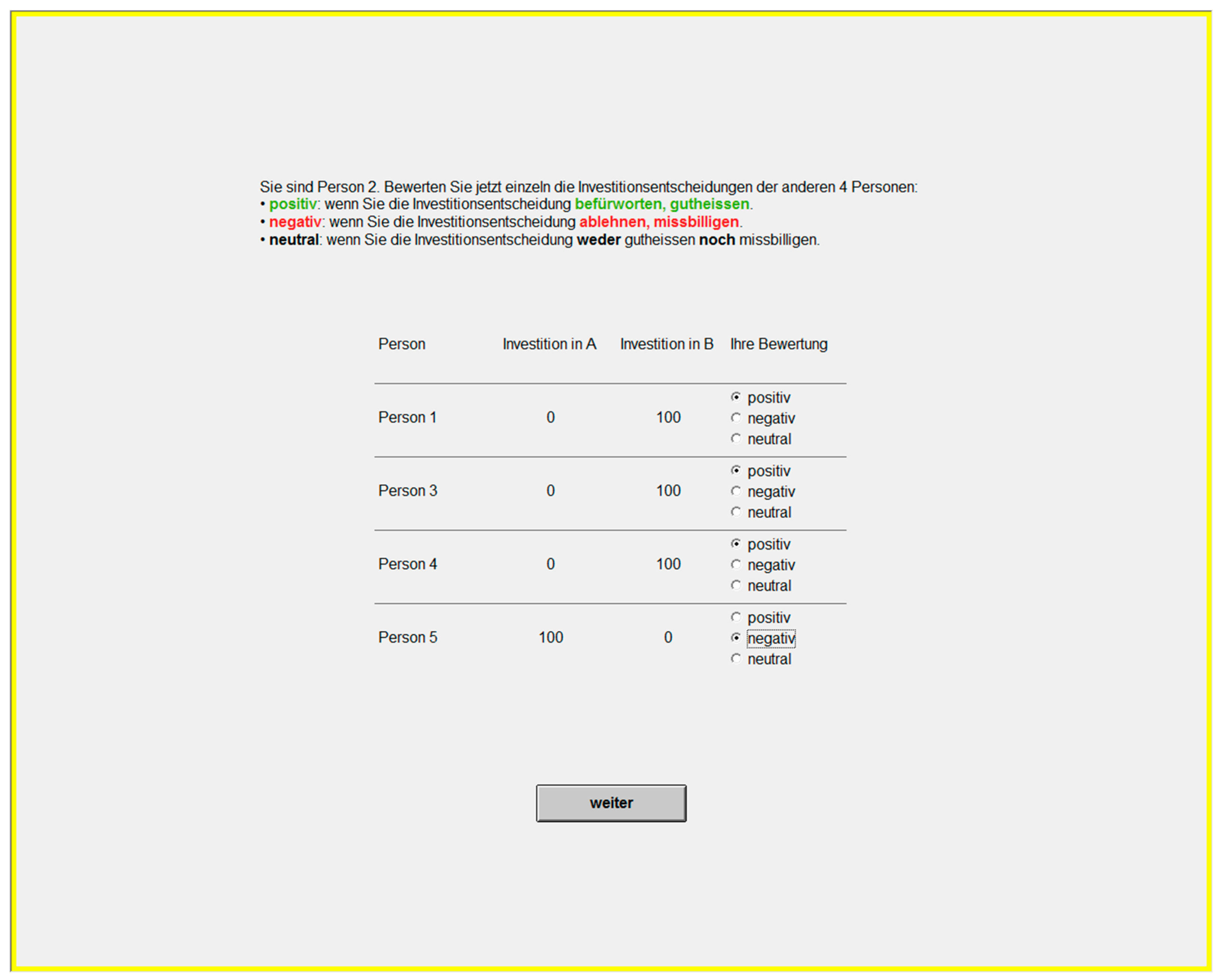

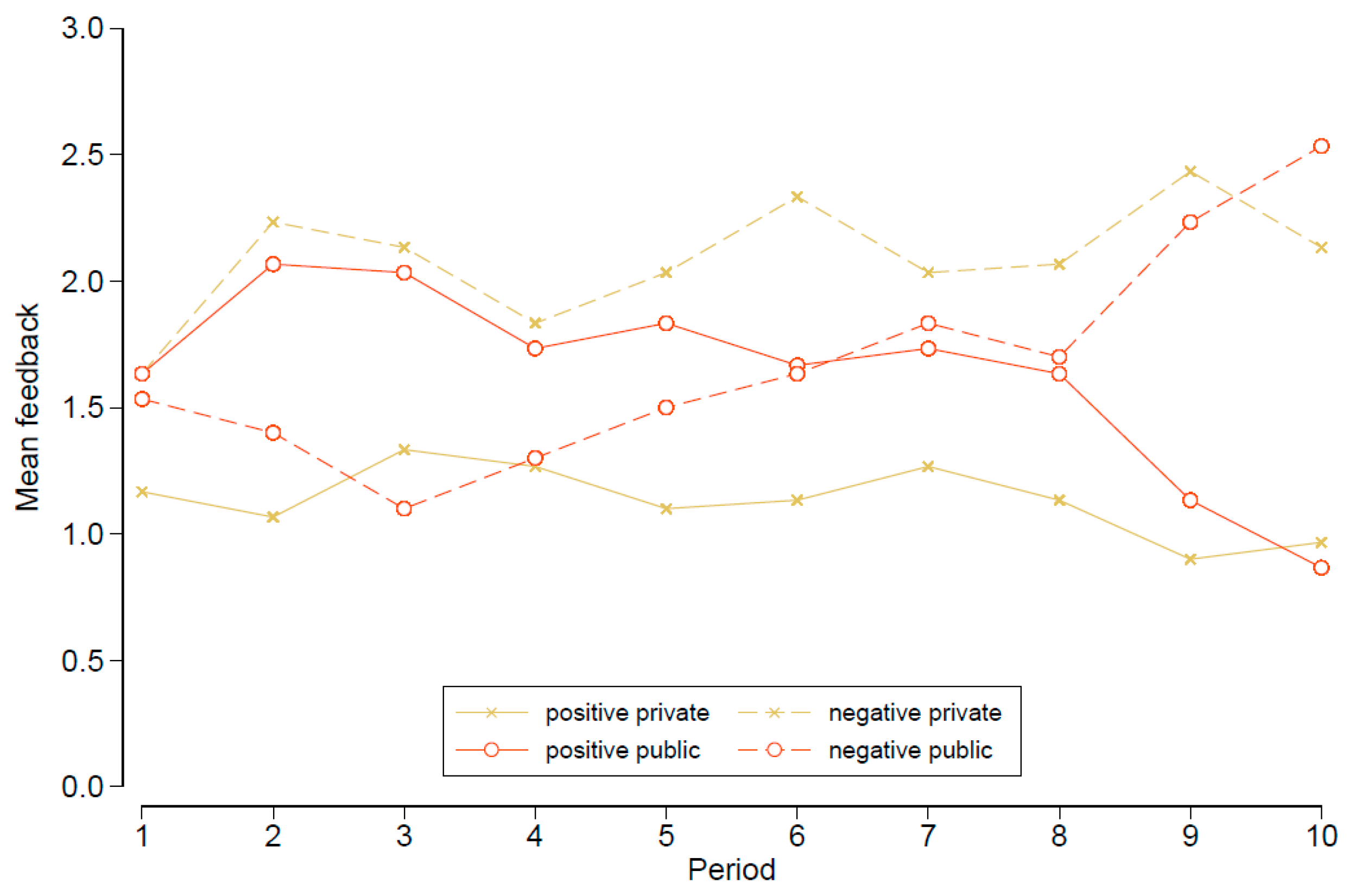

- In the private feedback condition, subjects were informed that after each round they would have the possibility to rate the other four subjects’ investment decisions. They were told that the ratings could be positive, negative or neutral and would express approval, disapproval or indifference (see Figure A2 in the Appendix A). Moreover, they were made aware that they would neither know which of the other subjects submitted a rating nor would the other subjects learn how they had been rated;

- In the public feedback condition, subjects received the same instructions as in the private feedback condition, but with one exception. Subjects were made aware of the fact that their score (i.e., number of positive minus number of negative ratings) would be displayed next to their number on the screen and would be visible to the other subjects in their group (see Figure A3 in the Appendix A).

5.2. Results

6. General Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Experimental Instructions

| Ex. 1: All 5 | Ex. 2: Only you | Ex. 3: All 5 | Ex. 4: Only you | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| invest in A | invest in A | invest in B | invest in B | |

| Your investment in A | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Your investment in B | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Total investment in A | 500 | 100 | 0 | 400 |

| Total investment in B | 0 | 400 | 500 | 100 |

| Your gain from A (+35%) | 135 | 135 | 0 | 0 |

| Your gain from B (+5%) | 0 | 0 | 105 | 105 |

| Costs from A (−2%) | −10 | −2 | 0 | −8 |

| Your profit | 125 | 133 | 105 | 97 |

| Ex. 1: All 5 invest in A (your average profit = 80). | ||||||||||

| Round | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Your investment in A | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Your investment in B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total investment in A | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Total investment in B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your gain from A (+35%) | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| Your gain from B (+5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Costs from A (−2%) | −10 | −20 | −30 | −40 | −50 | −60 | −70 | −80 | −90 | −100 |

| Your profit | 125 | 115 | 105 | 95 | 85 | 75 | 65 | 55 | 45 | 35 |

| Ex. 2: Only you invest in A (your average profit = 124) | ||||||||||

| Round | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Your investment in A | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Your investment in B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total investment in A | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total investment in B | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Your gain from A (+35%) | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| Your gain from B (+5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Costs from A (−2%) | −2 | −4 | −6 | −8 | −10 | −12 | −14 | −16 | −18 | −20 |

| Your profit | 133 | 131 | 129 | 127 | 125 | 123 | 121 | 119 | 117 | 115 |

| Ex. 3: All 5 invest in B (your average profit = 105) | ||||||||||

| Round | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Your investment in A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your investment in B | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total investment in A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total investment in B | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Your gain from A (+35%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your gain from B (+5%) | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Costs from A (−2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your profit | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Ex. 4: Only you invest in B (your average profit = 61) | ||||||||||

| Round | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Your investment in A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your investment in B | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total investment in A | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Total investment in B | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Your gain from A (+35%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Your gain from B (+5%) | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Costs from A (−2%) | −8 | −16 | −24 | −32 | −40 | −48 | −56 | −64 | −72 | −80 |

| Your profit | 97 | 89 | 81 | 73 | 65 | 57 | 49 | 41 | 33 | 25 |

References

- Mintz, A. Non-adaptive group behavior. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1951, 46, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Christensen, V.; Gunette, S.; Pitcher, T.J.; Sumaila, U.R.; Walters, C.J.; Watson, R.; Zeller, D. Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature 2002, 418, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- List, J.A. (Ed.) Using Experimental Methods in Environmental and Resource Economics; Edward Elgar: Chaltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. The value-added of laboratory experiments for the study of institutions and common-pool resources. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 61, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Walker, J.M.; Gardner, R. Covenants with and without a sword: Self-governance is possible. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1992, 86, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.M.; Gardner, R.; Ostrom, E. Rent dissipation in a limited-access common-pool resource: Experimental evidence. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1990, 19, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, A.; Gardner, R.; Walker, J.M. An experimental study of time-independent and time-dependent externalities in the commons. Games Econ. Behav. 1997, 19, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, R.C.; Edney, J.J. The commons dilemma: A simulation testing the effects of resource visibility and territorial division. Hum. Ecol. 1978, 6, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edney, J.J.; Harper, C.S. The commons dilemma: A review of contributions from psychology. Environ. Manag. 1978, 2, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A. Experiments with n-person social traps II: Tragedy of the commons. J. Confl. Resolut. 1988, 32, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinski, M.; Sommerfeld, R.D.; Krambeck, H.-J.; Reed, F.A.; Marotzke, J. The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürerk, Ö.; Irlenbusch, B.; Rockenbach, B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science 2006, 312, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, P. Rewards and Punishments as Selective Incentives for Collective Action: Theoretical Investigations. Am. J. Sociol. 1980, 85, 1356–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R. An Evolutionary Approach to Norms. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1986, 80, 1095–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 2002, 415, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.A.; Holahan, R.; Lee, A.; Ostrom, E. Lab experiments for the study of social-ecological systems. Science 2010, 328, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochet, O.; Page, T.; Putterman, L. Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussair, C.; Tucker, S. Combining monetary and social sanctions to promote cooperation. Econ. Inq. 2005, 43, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclet, D.; Noussair, C.; Tucker, S.; Villeval, M.-C. Monetary and Nonmonetary Punishment in the Voluntary Contributions Mechanism. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S.; Fehr, E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 2001, 71, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, N. Altruismus, Moralität und Vertrauen. Anal. Krit. 1992, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Snijders, C. Trust and Commitments; Thela Thesis: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Charness, G.; Dufwenberg, M. Promises and Partnership. Econometrica 2006, 74, 1579–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosler, H.-J.; Gutscher, H. Kooperation durch Selbstverpflichtung im Allmende-Dilemma. In Umweltsoziologie, Sonderheft 36 der Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie; Diekmann, A., Jaeger, C.C., Eds.; Westdeutscher Verlag: Opladen, Germany, 1996; pp. 308–323. [Google Scholar]

- Vieth, M. Commitments and Reciprocity in Trust Situations. Experimental Studies on Obligation, Indignation, and Self-Consistency; ICS-Dissertation: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M. Promises, Threats and Fairness. Econ. J. 2004, 114, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Fehr, E. Collective action as a social exchange. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1999, 39, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, M.; Telle, K. The impact of social approval and framing on cooperation in public good situations. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1625–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M. Anticipated verbal feedback induces altruistic behavior. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2008, 29, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, E.; Houser, D. Avoiding the sharp tongue: Anticipated written messages promote fair economic exchange. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, R.; Vorsatz, M. On approval and disapproval: Theory and experiments. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugar, S. Nonmonetary sanctions and rewards in an experimental coordination game. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2010, 73, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. the constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A.S.; Green, D.P.; Larimer, C.W. social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2008, 102, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snijders, T.A.B.; Bosker, R.J. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willer, R. Groups Reward individual sacrifice: The status solution to the collective action problem. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrler, S.; Przepiorka, W. Charitable giving as a signal of trustworthiness: Disentangling the signaling benefits of altruistic acts. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2013, 34, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, D.; Przepiorka, W. Natural and strategic generosity as signals of trustworthiness. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Signaling can increase consumers’ willingness to pay for green products. Theoretical model and experimental evidence. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, W.; Horne, C. How can consumer trust in energy utilities be increased? The effectiveness of prosocial, pro-environmental, and service-oriented investments as signals of trustworthiness. Organ. Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B.; Willer, R. Beyond altruism: Sociological foundations of cooperation and prosocial behavior. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Przepiorka, W. Punitive preferences, monetary incentives and tacit coordination in the punishment of defectors promote cooperation in humans. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P.E.; Marwell, G.; Teixeira, R. A Theory of the critical mass. i. interdependence, group heterogeneity, and the production of collective action. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 522–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton-Chellew, M.N.; May, R.M.; West, S.A. Combined inequality in wealth and risk leads to disaster in the climate change game. Clim. Chang. 2013, 120, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, E.; Riedl, A. Enforcement of contribution norms in public good games with heterogeneous populations. Games Econ. Behav. 2013, 77, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, A.; Dannenberg, A.; Kallis, G.; Löschel, A. Inequality, communication, and the avoidance of disastrous climate change in a public goods game. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11825–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, A.; Heckman, J.J. Lab experiments are a major source of knowledge in the social sciences. Science 2009, 326, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassarri, D.; Abascal, M. Field experiments across the social sciences. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2017, 43, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Both the first and the second experiment were programmed and conducted with the software z-Tree [36]. |

| 2 | In fact, seven sessions were conducted. Since not enough subjects showed up in Session 1, the missing treatment condition was tested in Session 7 where ten subjects were randomized on two treatments. The analysis is based on the pooled session 1 and 7 data. However, Session 7 data not generated by subjects in the missing treatment is excluded from the analysis. |

| 3 | The set of scenarios chosen for illustration was balanced, in the sense that it did not prime subjects on a particular behavior (see instructions in the Appendix A). |

| 4 | Note that in the contract condition there is no difference between investments of subjects who had signed a contract and those who had not. Therefore, the analysis is based on the pooled data disregarding whether or not subjects had initially signed the contract. |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | Coef | SE | Coef | SE | |

| Main Effects | ||||||

| no regulation (ref.) | 28.370 *** | 3.836 | 28.085 *** | 3.918 | 33.872 *** | 4.056 |

| promise no | −1.808 | 4.966 | −2.516 | 5.289 | −5.777 | 4.473 |

| promise yes | 18.004 * | 7.633 | 19.991 * | 7.970 | 18.440 * | 6.489 |

| contract no | 4.475 | 5.159 | 4.519 | 5.343 | 3.741 | 4.127 |

| period | −4.160 *** | 0.588 | −3.591 *** | 0.819 | −2.378 ** | 0.680 |

| Interactions with Period | ||||||

| promise no | 1.416 | 1.127 | 1.620 | 1.191 | ||

| promise yes | −3.975 * | 1.552 | −4.260 ** | 1.351 | ||

| contract no | −0.088 | 0.812 | −0.749 | 0.829 | ||

| Conditional Cooperation | ||||||

| others’ A (lag 1) | −0.080 ** | 0.027 | ||||

| N1 (decisions) | 1600 | 1600 | 1440 | |||

| N2 (groups) | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||

| adj. R2 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.16 | |||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | Coef | SE | Coef | SE | |

| Main Effects | ||||||

| no regulation (ref.) | 33.843 *** | 3.430 | 32.535 *** | 3.424 | 36.689 *** | 2.923 |

| contract no | −4.192 | 6.789 | −4.192 | 6.793 | −2.947 | 5.744 |

| priv. feedback | −1.639 | 6.448 | −1.639 | 6.452 | −0.956 | 5.131 |

| publ. feedback | 16.578 *** | 2.344 | 23.771 *** | 3.024 | 17.427 *** | 2.811 |

| period (lin.) | −1.240 | 0.731 | −1.343 | 0.722 | −0.953 | 0.746 |

| period (quad.) | −0.590 ** | 0.168 | −0.430 * | 0.173 | −0.404 * | 0.173 |

| Interaction with Publ. Feedback | ||||||

| period (lin.) | 0.567 | 1.409 | −1.129 | 1.474 | ||

| period (quad.) | −0.880 ** | 0.271 | −0.304 | 0.266 | ||

| Conditional Cooperation | ||||||

| others’ A (lag 1) | −0.061 * | 0.023 | ||||

| N1(decisions) | 1650 | 1650 | 1485 | |||

| N2(groups) | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||

| adj. R2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przepiorka, W.; Diekmann, A. Binding Contracts, Non-Binding Promises and Social Feedback in the Intertemporal Common-Pool Resource Game. Games 2020, 11, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11010005

Przepiorka W, Diekmann A. Binding Contracts, Non-Binding Promises and Social Feedback in the Intertemporal Common-Pool Resource Game. Games. 2020; 11(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11010005

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzepiorka, Wojtek, and Andreas Diekmann. 2020. "Binding Contracts, Non-Binding Promises and Social Feedback in the Intertemporal Common-Pool Resource Game" Games 11, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11010005

APA StylePrzepiorka, W., & Diekmann, A. (2020). Binding Contracts, Non-Binding Promises and Social Feedback in the Intertemporal Common-Pool Resource Game. Games, 11(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11010005