Punishment, Cooperation, and Cheater Detection in “Noisy” Social Exchange

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The experiment

2.1. Method

Participants

Experimental procedure

3. Results

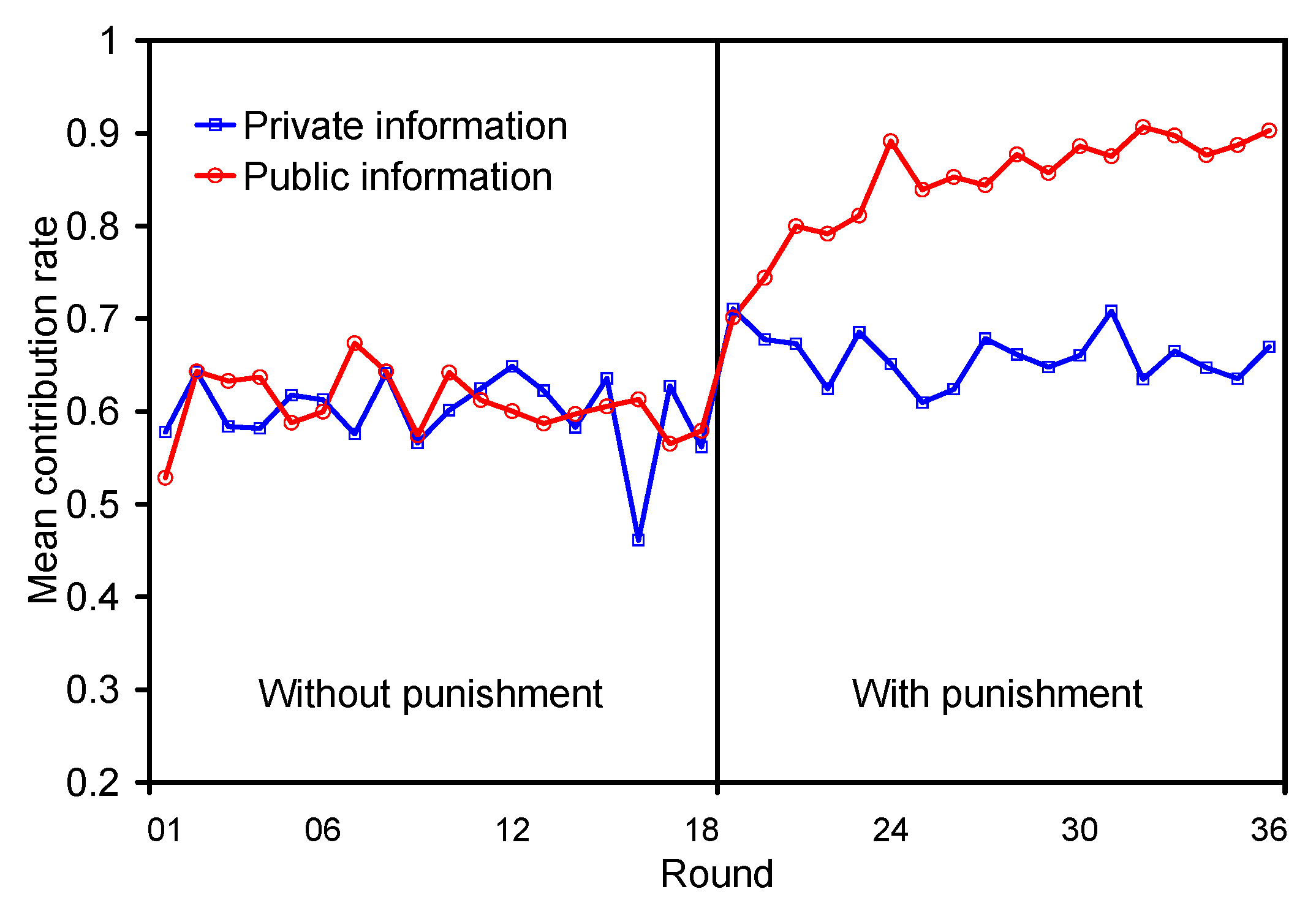

Contribution rates

Punishment behavior

Who was more likely to punish or to be punished?

Punishment and deviation from group contribution

Effect of punishment on lagged contributions

Endowment effect

Collective efficiency

4. Discussion and implications

Acknowledgements

- 1.Indeed, a common practice among the Anbara, an Aboriginal tribe where food-sharing norms are strongly enforced, is eating during food collection so that the greater part of a person’s take is in an advanced state of digestion by the time he or she returns to camp [8].

- 2.Although negative payoffs were possible, we assumed that they would be a very unlikely occurrence, given that it was not possible to lose money in the first stage of the game (See subsequent paragraphs). Had any of the participants asked, we would have assured them privately that they would not be asked to pay out any money. However, none of the participants asked, and nobody ended up with a negative payoff.

- 3.Unless otherwise stated, reported p-values are one-tailed.

- 4.The Z score, here and in all WRS tests in the paper, includes a continuity correction of 0.5.

- 5.SDs, treating individuals as the unit of analysis, are 15.55 for the PUBLIC condition and 11.31 for the PRIVATE condition. Treating groups as the unit of analysis yields 5.6 and 3.47, respectively.

- 6.The most cooperative members contributed, on average, 75% of their endowments in the first stage of the game in the PUBLIC condition and 74% in the PRIVATE condition. The contribution averages for the least cooperative members were 44% and 45%, respectively.

- 7.A similar effect of punishment on the re-distribution of wealth was reported by Visser [30].

- 8.No statistical tests are provided to establish the differences in the likelihood of punishing others, the likelihood of being punished, or the number of MUs used for punishing others in the PRIVATE condition because these differences either did not exist or were in the opposite direction from the (significant) differences found in the PUBLIC condition. The difference in the number of punishment MUs received, while in the predicted direction, was not significant (U=181.5, (==18), Z=0.61, p=.271).

- 9.The dependent variable is ().

- 10.The analysis was done at the group level. For each group we computed the average contribution rate of its members for each endowment level, separately for the no-punishment and punishment stages. A matched observation consists of these two averages.

- 11.The maximal possible joint payoff for a group is simply twice the sum of group members’ endowments. This happens when all group members contribute their entire endowment, and no MUs are used for punishment.

- 12.SDs are based on 18 time-averaged group efficiency scores.

- 13.The overall use of punishment in our experiment was lower than that observed in other public goods experiments (e.g., [17]). This perhaps can be explained by the fact that the endowments in the present experiment were fairly low (an average of 5 MUs per round as compared with 20 MUs in most other experiments), making punishment a very potent weapon, which subjects might be reluctant to use. Nevertheless, in the PUBLIC condition punishment was highly effective, increasing cooperation to the same level as in other experiments. Clearly the relative severity of punishment and the fact that it was cautiously used did not hinder its effectiveness. In the PRIVATE condition participants still expended on punishment about 60% of what they did in the PUBLIC condition - a substantial proportion - with a small, arguably negligible, effect on cooperation. The severity of punishment, thus, seems an unlikely explanation for its differential effect in the two conditions. This, however, is essentially an empirical matter that could be studied in future experiments.

- 14.This research used the Wason selection task which presents subjects with a conditional rule of the form “If P, then Q” and four two-sided cards, each of which has a P or a Q on one side and a not P or a not Q on the other. The subjects’ task is to select the cards that must be turned over to determine whether the rule has been violated. Numerous studies have found that most people fail to make the logically correct selections in this abstract context [46], but performance is greatly improved in a cheater detection context [44]. Whether these findings prove the existence of a special cheater detection module is highly controversial, however [47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

References

- Cashdan, E.A. Coping with Risk: Reciprocity Among the Basarwa of Northern Botswana. Man 1985, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B.; Bird, D.W.; Smith, E.A.; Kushnick, G.C. Risk and Reciprocity in Meriam Food Sharing. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2002, 23, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesa, K.; O’Connella, J.; Jones, N.B. Hadza Meat Sharing. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2001, 22, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Significance of Storage in Hunting Societies. Man 1983, 18, 517–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, A.J.; Kaplan, H.S. Viewpoint: The Economics of Hunter-Gatherer Societies and the Evolution of Human Characteristics. Can. J. Economics 2006, 39, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbink, K.; Irlenbusch, B.; Renner, E. Group Size and Social Ties in Microfinance Institutions. Econ. Inq. 2007, 44, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F.; Genicot, G.; Ray, D. Informal Insurance in Social Networks. J. Econ. Theory 2008, 143, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiatt, L. Traditional Attitudes to Land Resources. In Aboriginal Sites: Rites and Resource Development; Berndt, R.M., Ed.; University of Western Australia Press: Perth, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, R.; Gintis, H.; Bowles, S.; Richerson, P. The Evolution of Altruistic Punishment. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3531–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U. The Nature of Human Altruism. Nature 2003, 425, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.; West, S.A. Cooperation and Punishment, Especially in Humans. Am. Nat. 2004, 164, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gintis, H. Strong Reciprocity and Human Sociality. J. Theor. Biol. 2000, 206, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gintis, H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Altruism: Gene-Culture Coevolution, and the Internalization of Norms. J. Theor. Biol. 2003, 220, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigmund, K.; Hauert, C.; Nowak, M.A. Reward and Punishment. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10757–10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J.; Boyd, R. Why People Punish Defectors: Weak Conformist Transmission can Stabilize Costly Enforcement of Norms in Cooperative Dilemmas. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 208, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.; Richerson, P. Punishment Allows the Evolution of Cooperation (or Anything Else) in Sizable Groups. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1992, 13, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. Altruistic Punishment in Humans. Nature 2002, 415, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurerk, O.; Irlenbusch, B.; Rockenbach, B. The Competitive Advantage of Sanctioning Institutions. Science 2006, 312, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockenbach, B.; Milinski, M. The Efficient Interaction of Indirect Reciprocity and Costly Punishment. Nature 2006, 444, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawes, R.M.; Thaler, R.H. Anomalies: Cooperation. J. Econ. Psychol. 1988, 2, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledyard, J.O. Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research. In Handbook of Experimental Economics; Kagel, J., Roth, A., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1995; pp. 111–195. [Google Scholar]

- Levati, V.; Sutter, M.; van der Heijden, E. Leading by Example in a Public Goods Experiment with Heterogeneity and Incomplete Information. J. Conflict Resolut. 2007, 51, 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, J.C. Real Wealth and Experimental Cooperation: Experiments in the Field Lab. Journal of Development Economics 2003, 70, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, T.L.; Kroll, S.; Shogren, J.F. The Impact of Endowment Heterogeneity and Origin on Public Good Contributions: Evidence from the Lab. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2005, 57, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Suleiman, R. Incremental Contribution in Step-Level Public Goods Games with Asymmetric Players. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. 1993, 55, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K.; Steisel, V.; Kay, A. The Effects of Resource Distribution, Voice, and Decision Framing on the Provision of Public Goods. J. Conflict Resolut. 1992, 36, 665–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Mestelman, S.; Moir, R.; Muller, R.A. Heterogeneity and the Voluntary Provision of Public Goods. Exp. Econ. 1999, 2, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.; Grodzka, M. The Influence of Endowment Asymmetry and Information Level on the Contribution to a Public Step Good. J. Econ. Psychol. 1992, 35, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.; Wilke, H.; Wilke, M.; Metman, L. What Information Do We Use in Social Dilemmas? Environmental Uncertainty and the Employment of Coordination Rules. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Welfare Implications of Peer Punishment in Unequal Societies. Working Papers in Economics 218; Go¨teborg University, Department of Economics, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreber, A.; Rand, D.G.; Fudenberg, D.; Nowak, M.A. Winners Don’t Punish. Nature 2008, 452, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E.; Walker, J.; Gardner, R. Covenants With and Without a Sword: Self-Governance is Possible. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1992, 86, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T. The Provision of a Sanctioning System as a Public Good. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U.; Gächter, S. Strong Reciprocity, Human Cooperation, and the Enforcement of Social Norms. Hum. Nature 2002, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gintis, H.; Bowles, S.; Boyd, R.; Fehr, E. Explaining Altruistic Behavior in Humans. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, S.; Gintis, H. The Evolution of Strong Reciprocity: Cooperation in Heterogeneous Populations. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2004, 65, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlbacher, S.; Kirchler, E. Origin of Endowments in Public Good games: The Impact of Effort on Contributions. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 2009, 2, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, R.; Erev, I.; Zinger, E.; Tzach, M. Tip Policy, Visibility and Quality of Service in Cafes. Tourism Econ. 2004, 10, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.R.; Beach, L.R. Man as an Intuitive Statistician. Psychol. Bull. 1967, 68, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, T.; Tanida, S.; Mashima, R.; Shimoma, E.; Kanazawa, S. You Can Judge a Book by its Cover: Evidence that Cheaters May Look Different From Cooperators. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplaetse, J.; Vanneste, S.; Braeckman, J. You Can Judge a Book by its Cover: the Sequel: A Kernel of Truth in Predictive Cheating Detection. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2007, 28, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetchenhauer, D.; Groothuis, T.; Pradel, J. Not Only States But Traits – Humans Can Identify Permanent Altruistic Dispositions in 20 s. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmides, L. The Logic of Social Exchange: Has Natural Selection Shaped How Humans Reason? Studies with the Wason Selection Task. Cognition 1989, 31, 187–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooby, J.; Cosmides, L. The Psychological Foundations of Culture. In The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture; Barkow, J., Tooby, J., Cosmides, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, 1992; chapter 1; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wason, P.C. Reasoning About a Rule. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1968, 20, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperber, D.; Cara, F.; Girotto, V. Relevance Theory Explains the Selection Task. Cognition 1995, 57, 31–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, D.; Girotto, V. Use or Misuse of the Selection Task? Rejoinder to Fiddick, Cosmides, and Tooby. Cognition 2002, 85, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J. Why We Are So Good at Catching Cheaters. Cognition 2000, 75, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddick, L.; Cosmides, L.; Tooby, J. No Interpretation Without Representation: the Role of Domain-Specific Representations and Inferences in the Wason Selection Task. Cognition 2000, 77, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atran, S. A Cheater-Detection Module? Dubious Interpretations of the Wason Selection Task and Logic. Evolution Cognition 2001, 7, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, C.P. Why Are We Good at Detecting Cheaters? A Reply to Fodor. Cognition 2002, 83, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiddick, L.; Erlich, N. Giving It All Away: Altruism and Answers to the Wason Selection Task. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Bornstein, G.; Weisel, O. Punishment, Cooperation, and Cheater Detection in “Noisy” Social Exchange. Games 2010, 1, 18-33. https://doi.org/10.3390/g1010018

Bornstein G, Weisel O. Punishment, Cooperation, and Cheater Detection in “Noisy” Social Exchange. Games. 2010; 1(1):18-33. https://doi.org/10.3390/g1010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleBornstein, Gary, and Ori Weisel. 2010. "Punishment, Cooperation, and Cheater Detection in “Noisy” Social Exchange" Games 1, no. 1: 18-33. https://doi.org/10.3390/g1010018

APA StyleBornstein, G., & Weisel, O. (2010). Punishment, Cooperation, and Cheater Detection in “Noisy” Social Exchange. Games, 1(1), 18-33. https://doi.org/10.3390/g1010018