A Comparative Review of Quantum Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)

2.1. CVD Key Types

- 1.

- Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

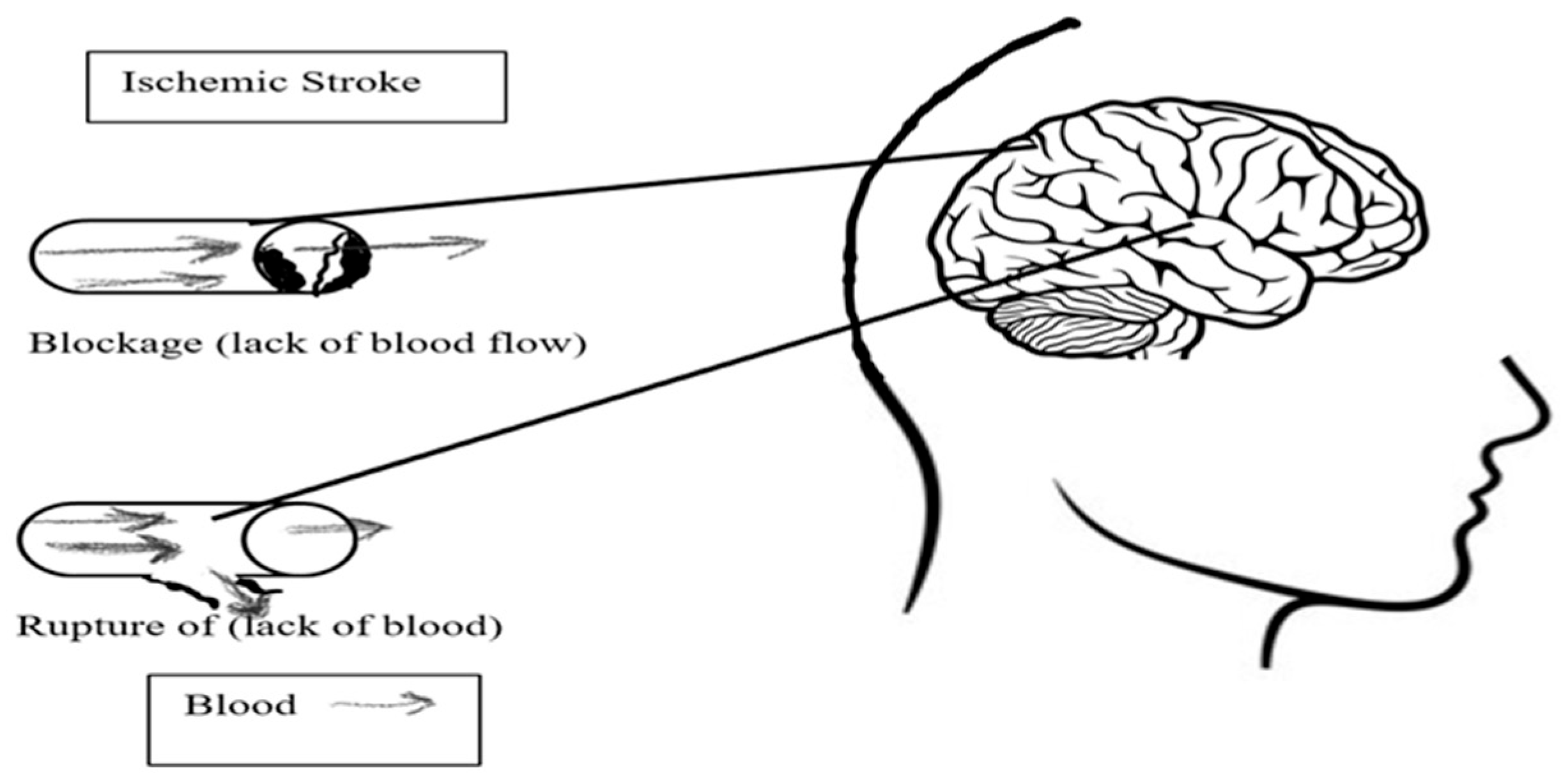

- 2.

- Cerebrovascular Disease

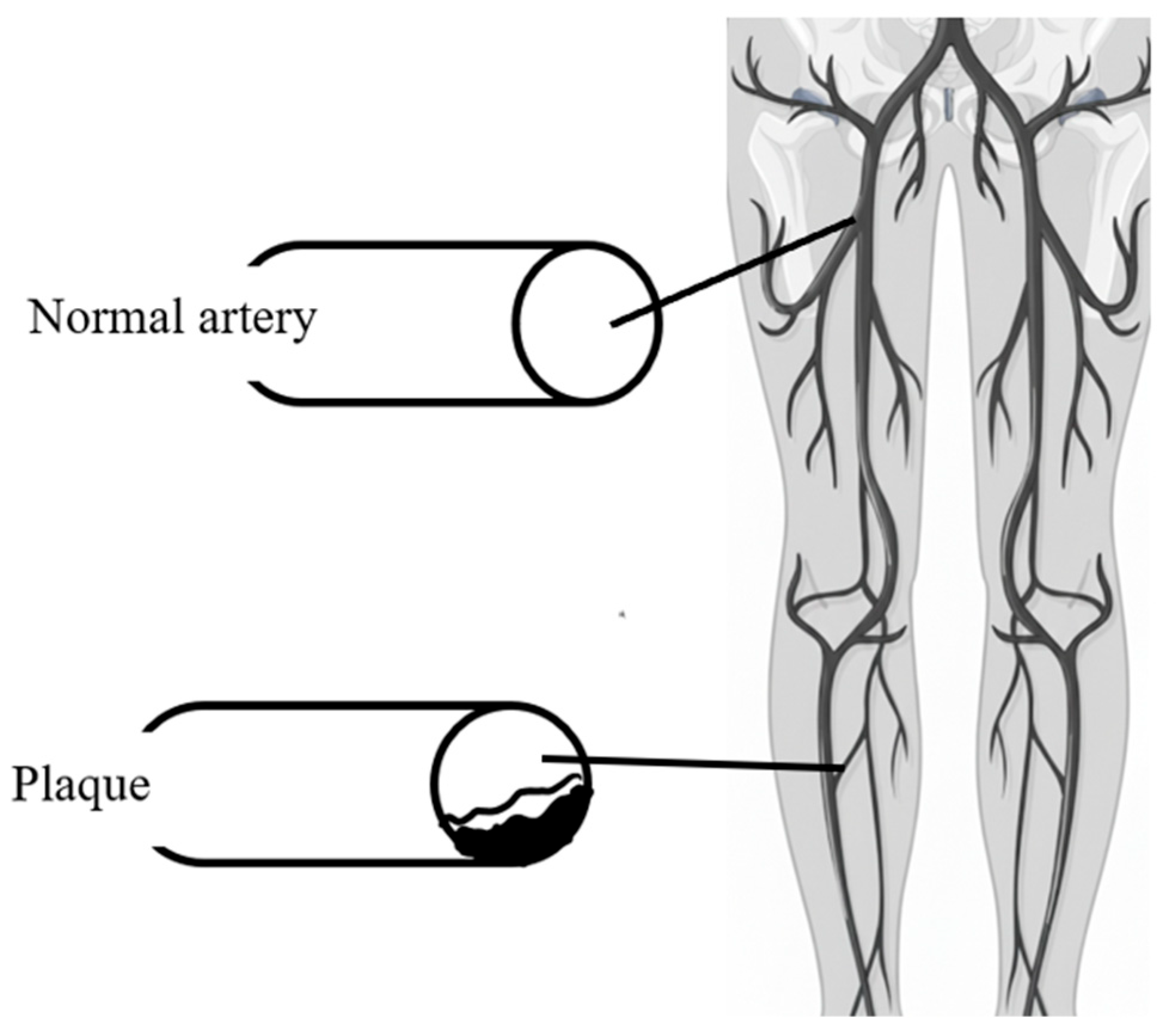

- 3.

- Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD)

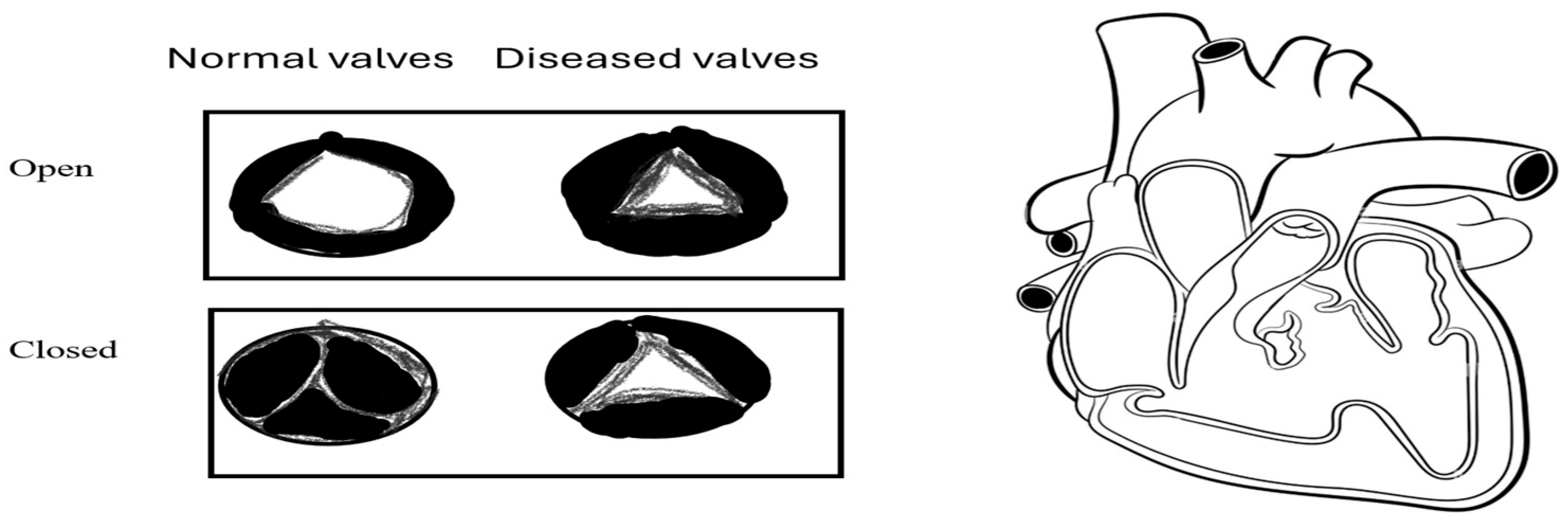

- 4.

- Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD)

- 5.

- Congenital Heart Disease (CHD)

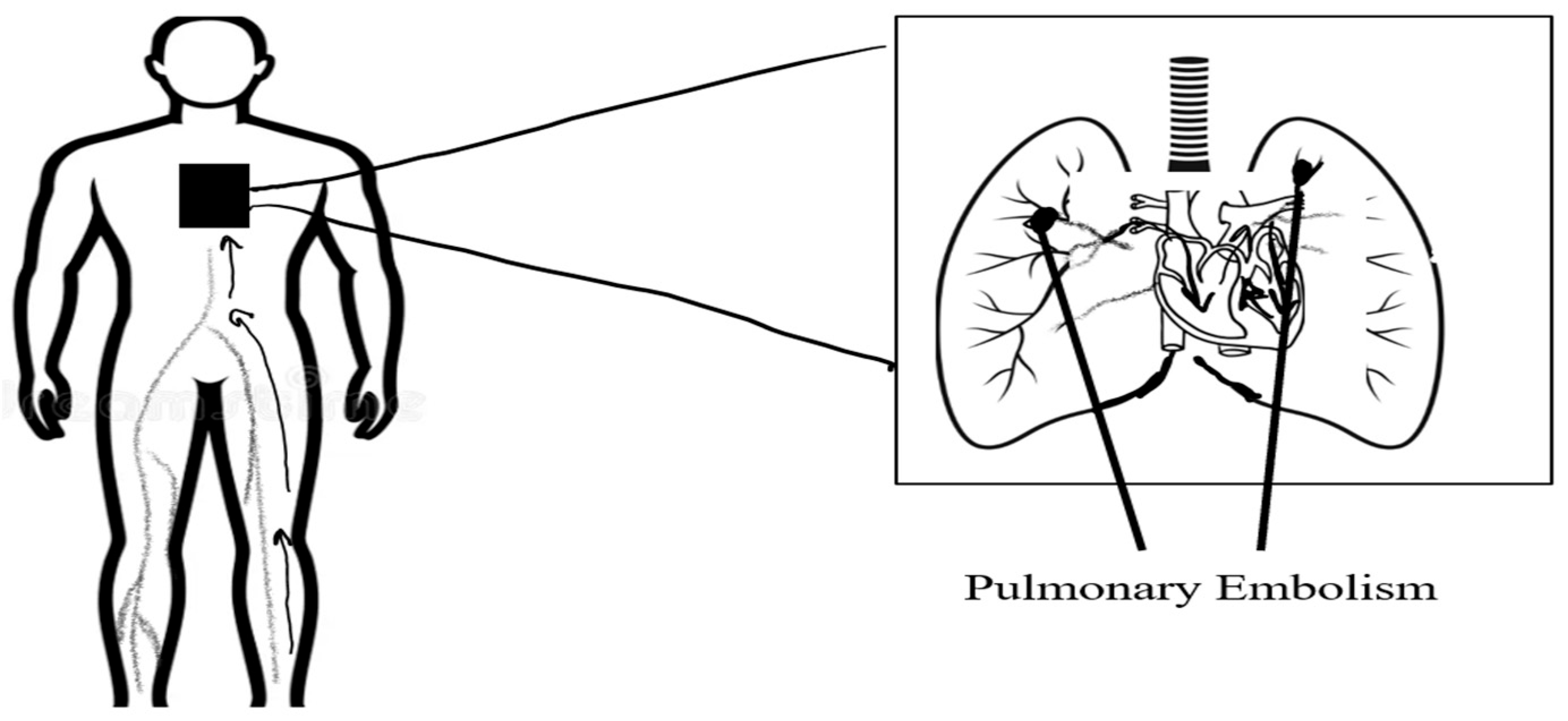

- 6.

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

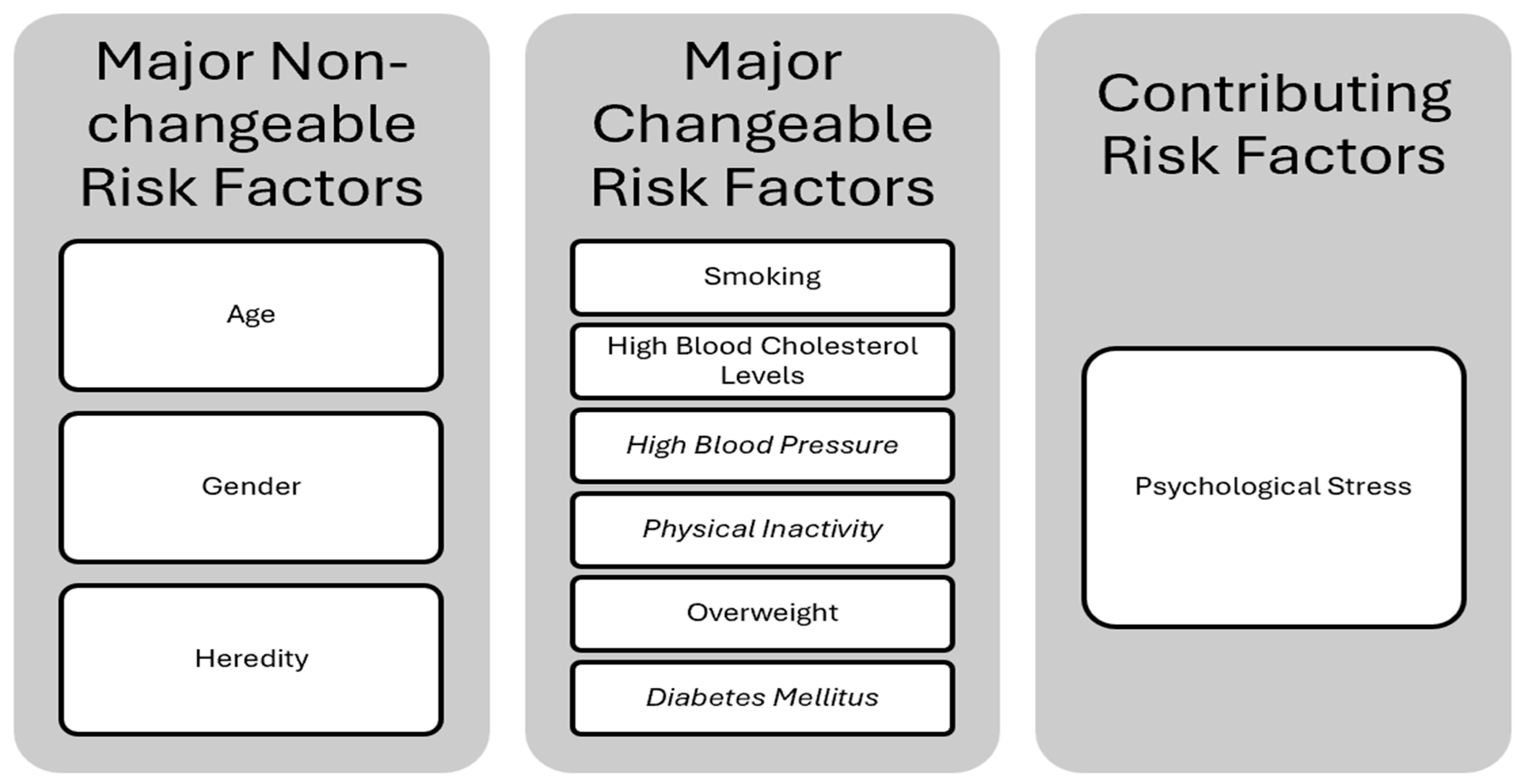

2.2. CVD Risk Factors

2.2.1. Major Non-Changeable Risk Factors

Age

Gender

Heredity (Family History and Race)

2.2.2. Major Changeable Risk Factors

Smoking

High Blood Cholesterol Levels (Hypercholesterolemia)

High Blood Pressure (Arterial Hypertension)

Physical Inactivity

Overweight (Obesity)

Diabetes Mellitus

2.2.3. Contributing Risk Factors

Psychological Stress

3. Quantum Computing (QC)

3.1. Principles of Quantum Computing

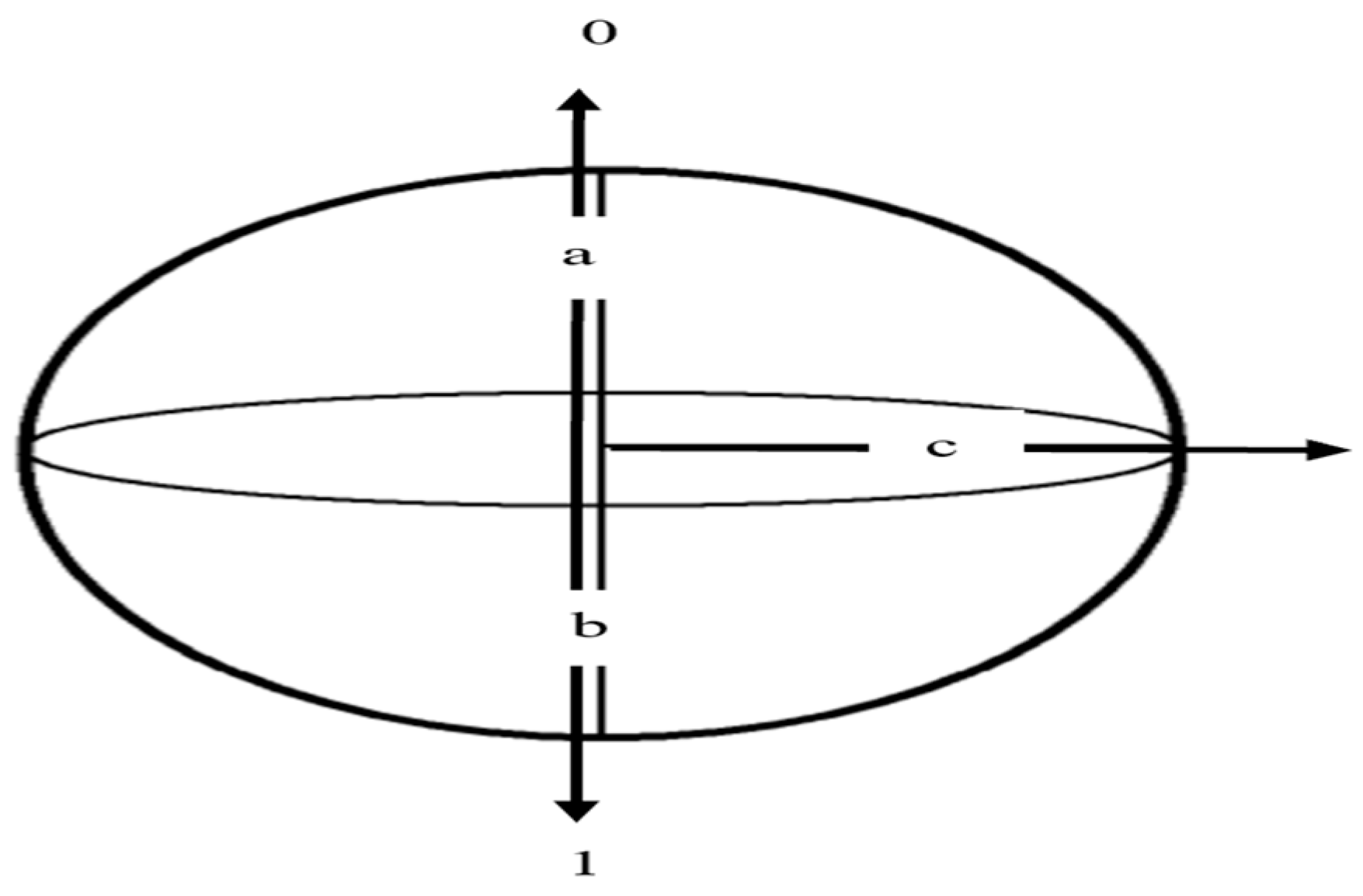

3.1.1. Qubits and Quantum States

3.1.2. Superposition

3.1.3. Entanglement

3.1.4. Quantum Gates

- Preserves the inner product as a guarantee that the total probability of all possible outcomes remains normalized to one;

- Is reversible, since every unitary operation has an inverse equal to its conjugate transpose;

- Is represented by a unitary matrix allowing for precise mathematical characterization and physical implementation.

3.1.5. Measurement

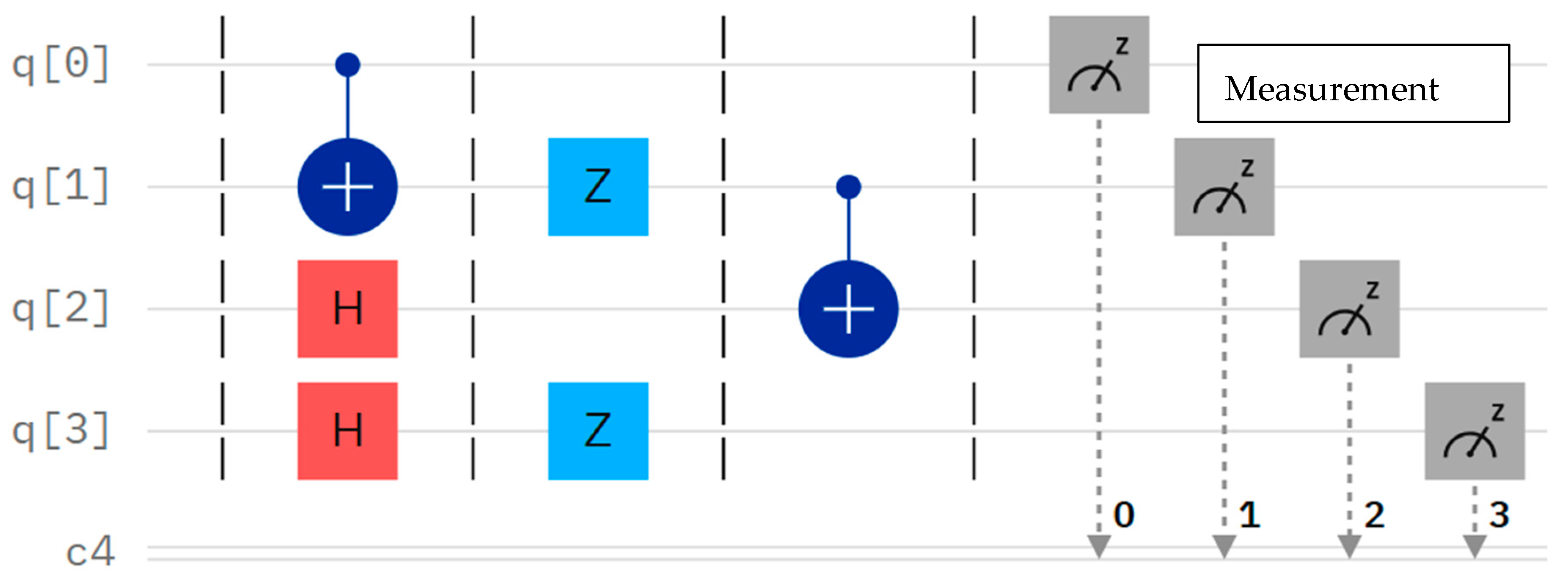

3.1.6. Quantum Circuits

), which is crucial for inducing entanglement. Finally, a measurement operation is performed on the first qubit (q0), collapsing its quantum state to extract the classical information [24,26].

), which is crucial for inducing entanglement. Finally, a measurement operation is performed on the first qubit (q0), collapsing its quantum state to extract the classical information [24,26].3.2. Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs)

3.3. Challenges in QC

3.3.1. Quantum Decoherence and Noise

3.3.2. Quantum Error Correction

3.3.3. Hardware Scalability

4. State of the Art

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Dataset

5.2. Classical Machine Learning (ML) Methods

5.3. Quantum Neural Network (QNN) Methods

5.4. Evaluation Metrics

5.4.1. Accuracy

5.4.2. Sensitivity (Recall)

5.4.3. Precision

5.4.4. F1-Score

6. Results and Comparative Performance Analysis

6.1. Performance of Classical Machine Learning Models

6.1.1. Traditional Classifiers

- Random Forest (RF) and Decision Tree (DT)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs)

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- Logistic Regression (LR)

- Naive Bayes

6.1.2. Deep Learning

- Deep Learning (DL)

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

- ○

- General ANN

- Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

6.2. Performance of Quantum Neural Network (QNN) Models

6.2.1. Deep Quantum Learning

- QNN in Quantum Deep Learning (DL): This model achieved the highest performance across all reviewed studies, reporting a perfect 98% across accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and F1-Score in [50]. This result is highly significant, as it shows that a multi-layered quantum approach can achieve near-perfect classification, exceeding classical accuracy. Additionally, it showed high promise, with accuracy ranging from 91.7% to 96.4% in early comparative work [46].

6.2.2. Quantum Machine Learning

- Quantum Neural Network

6.2.3. Hybridization Techniques

6.3. Analysis Summary

7. Significance of This Work

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Nedkoff, L.; Briffa, T.; Zemedikun, D.; Herrington, S.; Wright, F.L. Global Trends in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Clin. Ther. 2023, 45, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmi, N.A.A.; Aksoy, M.S. A review of big data analytic in healthcare. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. (TURCOMAT) 2021, 12, 4542–4548. [Google Scholar]

- Raihan, U.R.; Ahmad, H.F.; Rafique, W.; Qayyum, A.; Qadir, J.; Anwar, Z. Quantum computing for healthcare: A review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Quantum Computing and Communications; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- lvin Rajkomar, M.D.; Dean, J.; KohaneMachine, I. Learning in Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziano, J.M.; Braunwald, E.; Zipes, D.P.; Libby, P. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 6th ed.; W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. About Coronary Artery Disease (CAD). 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/coronary-artery-disease.html (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- John, A.; Moawad, M.D. FACS—Written by Sy Kraft—Updated on. In What to Know About Cerebrovascular Disease; Healthline Media UK Ltd.: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/184601 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Moawad, J.A. What to Know About Cerebrovascular Disease. Medical News Today. 2023. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/184601#types (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Centers for Disease Control and About Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD); CDC Heart Disease. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/peripheral-arterial-disease.html (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Jennings, D.; Lillis, C. What Are the Jones Criteria for Rheumatic Heart Disease? Healthline Media UK Ltd.: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/rheumatic-heart-disease-jones-criteria (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Seitler, S.; Zuhair, M.; Shamsi, A.; Bray, J.J.H.; Wojtaszewska, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Ahmad, M.; Fairley, J.; Providencia, R.; Akhtar, A. Cardiac imaging in rheumatic heart disease and future developments. Eur. Heart J. Open 2023, 3, oeac060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zühlke, L.; Black, G.C.; Choy, M.K.; Li, N.; Keavney, B.D. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oen-Hsiao, J.; Brazier, Y. Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Defects; Healthline Media UK Ltd.: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/181142 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Peracaula, M.; Sebastian, L.; Francisco, I.; Vilaplana, M.B.; Rodríguez-Chiaradía, D.A.; Tura-Ceide, O. Decoding Pulmonary Embolism: Pathophysiology. Diagn. Treat. Biomed. 2024, 12, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Raskob, G.E.; Angchaisuksiri, P.; Blanco, A.N.; Büller, H.; Gallus, A.; Hunt, B.J.; Hylek, E.M.; Kakkar, T.L.; Konstantinides, S.V.; McCumber, M. Thrombosis: A Major Contributor to Global Disease Burden. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2024, 40, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. Pulmonary Embolism. Patient Educ. Ser. 2018, 197, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chenzbraun, A. Heart Disease; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henein, M.Y.; Vancheri, S.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, F. The Impact of Mental Stress on Cardiovascular Health—Part II. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, P.; Srivastava, S.; Xu, X.; Mehta, J.L. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Cardiovascular Disease. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2020, 14, 1179546820927404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, S.A.; Dave, S.; Patel, K.C.; Raval, M.N. Application of quantum artificial intelligence in healthcare. In Quantum Computing for Healthcare Data, Revolutionizing the Future of Medicine; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; Chapter 6; pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Qurban, A.M.; Al Ahmad, M.; Pecht, M. Quantum Computing: Navigating the Future of Computation, Challenges, and Technological Breakthroughs. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 627–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.A.; Munir, A. Latif Quantum computing: Circuits, Algorithms, and Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 22296–22314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurczak, C. Investing in the Quantum Future: State of Play and Way Forward for Quantum Venture Capital. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, 10th Anniversary ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marella, S.T.; Parisa, H.S.K. Introduction to Quantum Computing; Intechopen: Leicester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, P.J.; Eidenbenz, S.; Pakin, S.; Adedoyin, A.; Ambrosiano, J.; Anisimov, P.; Casper, W.; Chennupati, G.; Coffrin, C.; Djidjev, H.; et al. Quantum algorithm implementations for beginners. ACM Trans. Quantum Comput. 2022, 3, 1–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhov, A.A.; Ventura, D. Quantum Neural Networks. In Future Directions for Intelligent Systems and Information Sciences: The Future; Physica-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 213–235. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Z. Evaluation and Implementation of Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering, Shanghai, China, 10–12 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, M.; Das, T.; Sutradhar, S.; Das, M.; Deb, S. An Analytical Review of Quantum Neural Network Models and Relevant Research. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 10–12 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, E.; Choi, J.; Kim, J. An elementary review on basic principles and developments of qubits for quantum computing. Nano Converg. 2024, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Eddins, A.; Anand, S.; Wei, K.X.; van den Berg, E.; Rosenblatt, S.; Nayfeh, H.; Wu, Y.; Zaletel, M.; Temme, K. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 2023, 618, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeter-Aydeniz, K.; Parks, Z.; Thekkiniyedath, A.N.; Gustafson, E.; Kemper, A.F.; Pooser, R.C.; Meurice, Y. Measuring qubit stability in a gate-based NISQ hardware processor. Quantum Inf. Process. 2023, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, A.; Kanchanadevi, K.; Mohan, V.C.; Krishna, P.H.; Govardhan, E. Quantum Generative adversarial Network and Quantum Neural Network for image classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), Gobichettipalayam, India, 7–9 April 2022; pp. 473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Senokosov, A.; Sedykh, A.; Sagingalieva, A.; Kyriacou, B.; Melnikov, A. Quantum machine learning for image classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.09224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Jimma, B.L.; Mihretie, T.B. Machine learning algorithms for heart disease diagnosis: A systematic review. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2025, 50, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janosim, A.; Steinbrunn, W.; Pfisterer, M.; Detrano, R. Heart Disease; University of California: Irvine, CA, USA, 1989; Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/45/heart+disease (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Jindal, H.; Agrawal, S.; Khera, R.; Jain, R.; Nagrath, P. Heart disease prediction using machine learning algorithms. In IOP Conference Series Materials Science and Engineering ICCRDA 2020; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Rajpura, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnu, K.; Reddy, V.; Elamvazuthi, I.; Paramasivam, S. Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Machine Learning Classifiers with Attribute Evaluators. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, R.; Khamparia, A.; Shabaz, M.; Dhiman, G.; Pande, S.; Singh, P. Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 8387680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ed-daoudy, A.; Maalmi, H.; El Ouaazizi, A. A scalable and real-time system for disease prediction using big data processing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 30405–30434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadli, K.M.; Almagrabi, A.O. Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 74, 5871–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, R.P.R.; Polepakaa, S.; Manasaa, V.; Palakurthya, D.; Annapoornab, E. Investigations on cardiovascular diseases and predicting using machine learning algorithms. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2386381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, N.; Hasan, M.A.; Nasution, F.B. Predicting Heart Disease Using Machine Learning: An Evaluation of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, and KNN Models on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset. IT J. Res. Dev. 2025, 9, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, H.; Hellstern, G. Early heart disease prediction using hybrid quantum classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.08882. [Google Scholar]

- Hanif, H.; Hellstern, G.; Murugappan, M. Heart Disease Detection using Quantum Computing and Partitioned Random Forest Methods. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.08882. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulsalam, G.; Meshoul, S.; Shaiba, H. Explainable Heart Disease Prediction Using Ensemble-Quantum Machine. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2023, 36, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubai, S.; Alqahtani, A.; Binbusayyis, A. Heart Failure Detection Using Instance Quantum Circuit Approach and Traditional Predictive Analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALAjmi, N.A.; Shoaib, M. Optimization Strategies in Quantum Machine Learning: A Performance Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, D.; Chhillar, R.S.; Alhussein, M.; Dalal, S.; Aurangzeb, K.; Lilhore, U.K. Enhanced cardiovascular disease prediction through self-improved Aquila optimized feature selection in quantum neural network & LSTM model. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1414637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, A.; Kashif, M.; Marchisio, A.; Shafique, M. Quantum neural networks: A comparative analysis and noise robustness evaluation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobescu, P.; Marina, V.; Anghel, C.; Anghele, A.D. Evaluating Binary Classifiers for Cardiovascular Disease Prediction: Enhancing Early Diagnostic Capabilities. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, K.; Kavihta, R.B.; Govrdhan, A. Applications of data mining techniques in healthcare and prediction of heart attacks. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2010, 2, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

| Ref. | Study | Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity (Recall) | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [39] | Heart Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms | Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbors and Random Forest Classifiers | 87.5% | NA | NA | NA |

| [39] | Heart Disease Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms | K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs) | 88.52% | NA | NA | NA |

| [40] | Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Machine Learning Classifiers with Attribute Evaluators | Naive Bayes | 84.15% | 84.2% | 84.3% | 84.1% |

| [40] | Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Machine Learning Classifiers with Attribute Evaluators | Logistic Regression | 83.17% | 83.2% | 83.2% | 83.1% |

| [40] | Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Machine Learning Classifiers with Attribute Evaluators | Sequential Minimal Optimization | 83.83% | 83.8% | 83. % | 83.8% |

| [40] | Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Machine Learning Classifiers with Attribute Evaluators | K-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs) | 78.87% | 78.9% | 78.9% | 78.8% |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | Logistic Regression | 83.3% | 86.3% | NA | NA |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | K-Nearest Neighbors | 84.8% | 85% | NA | NA |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 83.2% | 78.2% | NA | NA |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | Random Forest | 80.3% | 78.2% | NA | NA |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | Decision Tree | 82.3% | 78.5% | NA | NA |

| [41] | Prediction of Heart Disease Using a Combination of Machine Learning and Deep Learning | Deep Learning (Feature Selection and Outlier Detection) | 94.2% | 82.3% | NA | NA |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Naive Bayes | 84.09% | 82.00% | 89.13% | 85.42% |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 85.23% | 83.33% | 88.89% | 86.02% |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Multi-Layer Perceptron | 80.68% | 83.72% | 78.26% | 80.90% |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Decision Tree | 82.95% | 80.39% | 89.13% | 84.54% |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Logistic Regression | 86.36% | 86.96% | 86.96% | 86.96% |

| [42] | A Scalable and Real-Time System for Disease Prediction Using Big Data Processing | Random Forest | 87.50% | 86.67% | 88.64% | 87.64% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 83.15% | 87.25% | 83.18% | 85.17% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | ANN: Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | 82.61% | 85.29% | 83.65% | 84.47% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | ANN: Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | 80.98% | 82.35% | 83.17% | 82.76% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Gaussian Process (GP) | 80.43% | 85.29% | 80.56% | 82.86% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Logistic Regression: LR | 80.43% | 83.33% | 81.73% | 82.52% |

| [43] | Feature-Limited Prediction on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Hybrid: Ensemble Model | 83.15% | 86% | 83.97% | 84.95% |

| [44] | Investigations on Cardiovascular Diseases and Predicting Using Machine Learning Algorithms | K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) | 66.7% | 91.7% | 88.8% | 90.2% |

| [44] | Investigations on Cardiovascular Diseases and Predicting Using Machine Learning Algorithms | Support Vector Machine (SVM, Linear Kernel) | 74.2% | 85% | 74% | 79.1% |

| [44] | Investigations on Cardiovascular Diseases and Predicting Using Machine Learning Algorithms | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | 70% | 84.2% | 77.0% | 80.4% |

| [44] | Investigations on Cardiovascular Diseases and Predicting Using Machine Learning Algorithms | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 83.61% | 97% | 76% | 85.2% |

| [45] | Predicting Heart Disease Using Machine Learning: An Evaluation of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, and KNN Models on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Random Forest (RF) | 89.7% | NA | NA | NA |

| [45] | Predicting Heart Disease Using Machine Learning: An Evaluation of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, and KNN Models on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 87.0% | NA | NA | NA |

| [45] | Predicting Heart Disease Using Machine Learning: An Evaluation of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM, and KNN Models on the UCI Heart Disease Dataset | Logistic Regression (LR) | 84.2% | NA | NA | NA |

| Ref. | Study | Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity (Recall) | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | Early Heart Disease Prediction Using Hybrid Quantum Classification | QNN in Quantum Deep Learning (DL) Model | 91.7~96.4% | NA | NA | NA |

| [47] | Heart Disease Detection using Quantum Computing and Partitioned Random Forest Methods | Hybrid Quantum–Classical Neural Network (HQNN) | 96.43% | NA | NA | NA |

| [48] | Explainable Heart Disease Prediction Using Ensemble Quantum Machine Learning Approach | QNN in Quantum Machine Learning (QML) | 86.84% | 86% | 88% | 87% |

| [49] | Heart Failure Detection Using Instance Quantum Circuit Approach and Traditional Predictive Analysis | QNN in Quantum Machine Learning (QML) | 84% | 84% | 83% | 84% |

| [49] | Heart Failure Detection Using Instance Quantum Circuit Approach and Traditional Predictive Analysis | QNN in Quantum Deep Learning (DL) Model | 98% | 98% | 98% | 98% |

| [50] | Optimization Strategies in Quantum Machine Learning: A Performance Analysis | QNN with COBYLA Optimizer | 92% | 89% | 97% | 93% |

| [50] | Optimization Strategies in Quantum Machine Learning: A Performance Analysis | QNN with L-BFGS-B Optimizer | 89% | 86% | 94% | 90% |

| [50] | Optimization Strategies in Quantum Machine Learning: A Performance Analysis | QNN with ADAM Optimizer | 52% | 53% | 97% | 68% |

| [51] | Enhanced Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Through Self-Improved Aquila Optimized Feature Selection in Quantum Neural Network and LSTM Model | Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) | 90.79% | 93.28% | 92.58% | 92.93% |

| [51] | Enhanced Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Through Self-Improved Aquila Optimized Feature Selection in Quantum Neural Network and LSTM Model | Quantum Neural Networks (QNN) with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks | 95.5% | 95.87% | 96% | 96.94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

AL Ajmi, N.A.; Shoaib, M. A Comparative Review of Quantum Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction. Computers 2026, 15, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020102

AL Ajmi NA, Shoaib M. A Comparative Review of Quantum Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction. Computers. 2026; 15(2):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020102

Chicago/Turabian StyleAL Ajmi, Nouf Ali, and Muhammad Shoaib. 2026. "A Comparative Review of Quantum Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction" Computers 15, no. 2: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020102

APA StyleAL Ajmi, N. A., & Shoaib, M. (2026). A Comparative Review of Quantum Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction. Computers, 15(2), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020102