1. Introduction

Shortest-path computation is fundamental to a wide range of critical systems, including urban mobility, logistics, communication networks, robotics, and large-scale information retrieval [

1]. The efficacy of these systems often depends on selecting an algorithm whose runtime and memory consumption scale efficiently with the structural properties of the underlying graph. Classical methods, such as Dijkstra’s algorithm, A*, and Bellman-Ford, provide exact solutions backed by mature theoretical guarantees [

2]. However, their empirical performance is highly sensitive to factors such as graph topology, density, edge-weight distributions, and implementation choices.

Concurrently, the rise of learned, neural approaches has generated interest in the potential of data-driven models to complement or even surpass classical methods [

3]. These models may serve as standalone solvers or as heuristic generators that enhance search efficiency. Despite this momentum, the practical conditions under which learned methods offer robust advantages over finely tuned classical baselines have not been sufficiently delineated [

4].

This study aims to conduct a comparative, topology-aware evaluation of Dijkstra’s algorithm, A*, Bellman-Ford, and a neural model with respect to time efficiency and memory consumption. By structuring experiments across grid, random, and scale-free graphs at multiple scales, we align our analysis with representative application archetypes that exhibit varying degree distributions, locality, and clustering characteristics. Such diversity is essential: grids mimic spatial and road-like networks where admissible, consistent heuristics are straightforward; random graphs reveal average-case behavior and sensitivity to edge density; and scale-free graphs test algorithmic robustness against heterogeneity and hub nodes [

5].

While theoretical time complexity provides a baseline guide, practical performance is heavily influenced by implementation specifics, such as priority-queue structures, early-termination criteria, and the informativeness of heuristics. The interaction between these implementation factors and graph topology is best understood through rigorous empirical analysis [

6].

Within this framework, A* exemplifies the critical importance of heuristic design: when an admissible and consistent heuristic tightly approximates the true cost-to-go, A* substantially reduces node expansions and execution time relative to Dijkstra’s algorithm. Conversely, poorly informed heuristics diminish these performance gains. In contrast, Bellman-Ford incurs higher computational overhead per iteration but provides essential robustness against negative edge weights and negative cycles, making it indispensable for scenarios where such weights are intrinsic and cannot be transformed [

7].

Learned methods introduce a distinct paradigm: they can be trained to approximate value functions or rank node priority, potentially yielding superior heuristics in highly structured environments [

8]. However, neural inference entails non-trivial runtime and memory overheads. If not carefully mitigated, this latency can outweigh the benefits of reduced search space. Furthermore, guaranteeing optimality or bounded suboptimality remains a significant challenge unless the learned components are integrated into frameworks that strictly enforce admissibility and consistency.

The primary contribution of this work is a unified, reproducible benchmarking framework that evaluates all four approaches under a common experimental protocol, specifically focusing on performance variations across diverse graph topologies. We quantify runtime and peak memory consumption, examine scaling behavior with respect to graph size and density, and delineate the specific conditions under which A*’s heuristic advantage is realized. Additionally, we profile a neural model both as a standalone solver and as a source of heuristic guidance, analyzing performance gaps and the trade-offs between solution quality and computational efficiency.

Collectively, our results inform a principled guide for algorithm selection: A* is preferable when high-fidelity heuristics are available; Dijkstra’s algorithm remains the robust baseline in the absence of such domain knowledge; Bellman-Ford is required when handling negative edge weights or detecting negative cycles; and learned methods are currently most effective when deployed as heuristic augmentations rather than replacements for exact algorithms. By foregrounding topology sensitivity and performance under realistic hardware constraints, this study provides actionable guidance for deploying shortest-path methods in production systems and identifies promising avenues for hybrid learned-classical strategies.

In this work, we investigate the following core research question: How do learned distance estimates, derived from standard machine learning models, influence the runtime–memory trade-offs and solution quality of classical shortest-path algorithms across diverse graph topologies?

Our primary contribution is not the proposal of a novel solver, but rather an empirical characterization of the interaction between learned heuristics and established graph search methods. Concretely, we:

Benchmark Baselines: We systematically compare Dijkstra’s algorithm, A*, and Bellman–Ford across multiple graph families to establish ground truth baselines for runtime, peak memory usage, and node expansions.

Develop Predictors: We train standard supervised models—specifically a Gradient Boosting Regressor and a Graph Neural Network—to approximate shortest-path distances.

Evaluate Integration: We integrate these models as heuristics within A* (AI-augmented A*) and rigorously quantify how their calibration, monotonicity, and error profiles translate into computational efficiency and solution near-optimality.

This framework enables us to clearly delineate the conditions under which learned heuristics meaningfully improve search efficiency, as well as identify the topological regimes where they provide limited benefit.

The classical algorithms evaluated herein—Dijkstra’s, A*, and Bellman–Ford—are foundational and thoroughly characterized in existing literature. Consequently, our work does not seek to expand the theoretical bounds or algorithmic structures of these solvers.

Instead, we employ these methods as robust reference baselines to:

Establish Benchmarks: Quantify standard runtime and memory profiles across representative graph families; and

Isolate Impacts: Provide a rigorous control group for evaluating the specific performance deviations introduced by learned heuristics within the A* framework.

In this work, we address the single-pair shortest-path problem on weighted graphs. Formally, let be a graph with non-negative edge weights . Given a source node and a target node , the objective is to find a path that minimizes the sum of edge weights. We evaluate this problem across three graph families commonly used to model real-world networks: Erdős–Rényi random graphs, grid graphs, and scale-free graphs. Our scientific objective is to systematically compare classical algorithms (Dijkstra’s, A*, and Bellman–Ford) against their counterparts enhanced by learned heuristics. We quantify how these integrations affect runtime, memory consumption, and search effort (node expansions) across varying topologies and scales. Rather than proposing a novel algorithm, we focus on characterizing when and to what extent standard machine learning models—functioning as distance predictors—can improve the efficiency of well-established methods like A*.

2. Literature Review

The shortest-path problem has anchored graph algorithm research for decades, with classical methods providing exact solutions under well-understood assumptions. Dijkstra’s algorithm remains the canonical approach for nonnegative edge weights, with practical performance shaped by priority queue choice, memory locality, and early termination upon reaching the target. A* generalizes Dijkstra’s by introducing heuristic guidance; when heuristics are admissible and consistent, A* preserves optimality while significantly reducing expansions in spatial and near-metric graphs. Bellman-Ford, on the other hand, trades efficiency for generality, supporting negative weights and enabling the detection of negative cycles.

Recent comparative and engineering-oriented studies reaffirm these foundational principles while emphasizing the decisive role of implementation, topology, and workload in empirical outcomes. For instance, Zhou et al. demonstrate that algorithmic rankings shift across graph densities and directedness, underscoring the insufficiency of asymptotic theory alone for predicting wall-clock behavior [

9]. Similarly, Manalo et al. highlight that low-level choices (such as heap variants, adjacency structures, and cache-aware layouts) can dominate practical performance, reinforcing the need for reproducible, system-conscious benchmarks [

10].

The study of shortest-path algorithms is rich, offering well-defined complexity boundaries. Dijkstra’s algorithm, with a time complexity of

using a min-priority queue, is the de facto standard for graphs with non-negative edge weights [

11]. Its efficiency is robust, but it can become inefficient on very dense graphs or when negative weights are introduced. The Bellman-Ford algorithm, while having a higher worst-case time complexity of

, remains crucial due to its ability to detect and handle negative edge weights, which are common in economic modeling and routing metrics [

12,

13]. The A* search algorithm is an extension of Dijkstra’s that utilizes a heuristic function to prioritize exploring nodes that appear closer to the target, significantly reducing the search space [

14]. Its performance is highly dependent on the quality of this heuristic; an effective heuristic can push the performance close to

while a poor one degrades it to

[

15]. The AI Model category represents a significant departure from these analytical methods. Recent work has explored using GNNs to learn the properties of optimal paths, effectively using the model to pre-calculate or approximate a superior heuristic [

16,

17]. While these models promise adaptability and domain-specific optimization, they carry a high initial training and inference overhead, typically leading to higher resource consumption [

18]. The feasibility of sch models hinges on whether the performance gains in complex scenarios outweigh the significant overhead. previous studies, sch as those by Jiang et al. [

19] and Zhang et al. [

20], have focused on comparing just two or three algorithms or specializing in a single graph type, underscoring the need for a comprehensive for-way analysis across diverse graph types.

Beyond baseline algorithms, production-quality libraries and their design decisions significantly affect both correctness and efficiency. Awasthi et al. document algorithmic options and API-level trade-offs in a widely used ecosystem, noting how default data structures, graph representations, and edge-weight conventions influence runtime and memory in practice [

21]. Fey and Lenssen contextualize these implementation issues historically, explaining why theoretically superior structures like Fibonacci heaps may underperform binary heaps in real settings due to constants, complexity, and poor locality. Earlier comparative work, such as The Comparison of Three Algorithms in Shortest Path Issue [

22], contributed foundational empirical baselines; while limited in scope by today’s standards, these studies foreshadowed the importance of topology and dataset diversity in evaluation.

Specialized variants and domain-tailored modifications expand the applicability of shortest-path methods. For example, Ref. [

23] introduces adaptable weighting schemes to reflect dynamic or context-dependent costs, a recurring requirement in transportation and logistics. In geographic information systems, Ref. [

24] exploits reduced or preprocessed graph structures to accelerate queries while maintaining accuracy on spatial networks. Similarly, Ref. [

25] assesses generation techniques that underpin realistic traveler choice sets; together, these works illustrate that problem context—spatial constraints, behavioral realism, and data workflows—shapes algorithm suitability as much as worst-case complexity does.

The literature also codifies systematic benchmarking practices. In [

26] advocates for reporting not only aggregate runtimes but also dispersion, effect sizes, and sensitivity to directedness and weight distributions. Furthermore, Ref. [

27] stresses the importance of transparent API behavior, test cases, and profiling hooks to support reproducibility. The convergence of these recommendations with engineering-focused guidance points toward benchmarks that explicitly vary topology, density, and edge distributions, measure peak memory alongside runtime, and publish environmental details and seeds [

28].

Concurrently, learned approaches examine whether data-driven models can assist or accelerate search. Li et al. survey the promise and limitations of GNN-based routing, noting challenges in generalization, stability, and integrating learning with algorithmic guarantees [

29]. Studies like [

30,

31] explore learned value functions or surrogate scores that can serve as heuristics. These findings indicate that while learned heuristics can reduce expansions in structured domains, calibration is crucial to preserve admissibility or to bound suboptimality. Furthermore, Ref. [

32] demonstrates that hybrid schemes combining local algorithmic steps with global learned signals can be effective on random graphs, though benefits depend strongly on the training distribution and graph statistics.

Synthesizing these strands suggests a pragmatic view. On road-like or grid graphs, A* paired with geometric or domain-informed heuristics typically dominates Dijkstra’s, consistent with classical theory and contemporary evaluations [

33]. However, on random and scale-free graphs, where spatial heuristics degrade and degree heterogeneity introduces hubs, the advantage of A* narrows unless heuristics are tailored, as indicated by comparative MDPI results. Bellman-Ford maintains a central role where negative edges or cycle detection are essential, with engineering guidance advising early stopping and careful memory management [

34]. Learned models hold promise as heuristic generators within A*, especially when domain-specific information is rich. However, current evidence [

35,

36,

37] cautions that inference overheads and calibration challenges can erode gains unless heuristics are both informative and well-bounded.

Consequently, a topology-aware, reproducible benchmark that measures runtime and peak memory, reports effect sizes and scaling behaviors, and makes environment/configurations public aligns with best practices emerging across MDPI, ResearchGate, and domain-specific venues.

In this study, we respond to these recommendations by structuring experiments across grids, random graphs, and scale-free networks; profiling Dijkstra’s, A*, Bellman-Ford, and a neural model under consistent measurement for both time and memory; and articulating when learned heuristics assist A* meaningfully relative to strong classical baselines. This positions our results as a bridge between engineering-centric insights and learning-driven opportunities, anchored in a methodology that reflects current consensus on rigorous comparative evaluation.

Beyond the immediate scope of shortest-path algorithms, our study aligns conceptually with research that frames model design as a multi-objective optimization problem—simultaneously maximizing accuracy and robustness while minimizing computational cost. This paradigm has been successfully applied across diverse engineering domains:

Energy and Infrastructure: In building energy forecasting, hybrid architectures combining transformers with liquid neural networks have been proposed to balance forecast accuracy with temporal adaptability and computational overhead. Similarly, in safety-critical infrastructure, frameworks utilizing non-dominated sorting genetic algorithms have optimized surveillance layouts (e.g., for bridge–ship collision warnings) by explicitly trading off coverage, deployment cost, and reliability within a Pareto-optimal structure [

38].

Civil and Financial Systems: Parallel efforts in civil engineering (wind-induced response prediction) and finance (volatility forecasting) highlight the necessity of physics-aware learning and multi-transformer architectures to ensure interpretability and generalization under dynamic conditions [

39,

40].

Our work extends this multi-objective lens to the domain of shortest-path computation. Rather than optimizing for a single metric, we explicitly evaluate classical algorithms, AI-augmented variants, and neural baselines as competing points on a trade-off landscape defined by accuracy, topological robustness, and computational efficiency [

41].

3. Methodology

This section details the experimental framework used to evaluate classical and learned-heuristic shortest-path methods. Our pipeline consists of three distinct stages:

Graph Generation: We generate graphs from three families—Erdős–Rényi, grid, and scale-free—across multiple sizes . For each combination of topology and size, we sample K independent graph instances and draw random source–target pairs.

Baseline Algorithms and Metrics: On every instance, we execute Dijkstra’s algorithm, classical A*, and Bellman–Ford. These runs provide ground-truth shortest-path distances (which serve as training labels) and establish baseline metrics for runtime, peak memory, and node expansions.

Learned Models and AI-Augmented A*: We train two distinct distance predictors: (i) a gradient boosting regressor using hand-engineered graph features, and (ii) a graph neural network (GNN) that operates directly on the graph structure. The predicted distances are integrated as heuristic functions within A*. We then re-evaluate the runtime, memory usage, and node expansions of this AI-augmented A* and compare the results against the classical baselines.

The following subsections provide technical details on the graph construction, algorithmic implementations, model architectures, and the evaluation protocol.

3.1. Experimental Setup

This study evaluates four approaches to shortest-path computation: Dijkstra’s algorithm, A*, Bellman-Ford, and a neural model utilized both as a direct solver and as a heuristic generator. Our experimental design emphasizes topology sensitivity, establishes fair implementation baselines, employs paired comparisons for statistical robustness, and ensures explicit measurement of runtime, memory usage, and search effort.

Repeated Trials and Aggregation: To ensure statistical robustness, we employ a hierarchical sampling strategy. For each experimental configuration (topology, size, algorithm, weighting), we generate multiple independent graph instances. Within each instance, we sample multiple random source–target pairs to capture performance variability across different regions of the same graph structure. This yields a comprehensive distribution of measurements for runtime, peak memory, node expansions, and path length.

Unless otherwise noted, we report the median as the primary measure of central tendency, chosen for its robustness against the outliers inherent in system-level timing measurements.

When interpreting algorithmic differences, we quantify variability using Interquartile Ranges (IQR) and standard deviations computed over these repeated trials.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 display the median values; detailed variability analysis is provided in

Section 4 specifically where performance distinctions are granular and require statistical context.

Robustness Checks: to validate that our conclusions regarding algorithmic efficiency extend beyond specific parametric regimes, we conducted a targeted series of robustness experiments. We introduced two distinct categories of perturbations to the base graph families:

Structural Perturbations (Density): We constructed denser graph variants by increasing the edge probability (p) for Erdős–Rényi graphs and the attachment parameter (m) for scale-free graphs, while maintaining fixed node counts. This increases the average degree and total edge count without altering the fundamental generative mechanism.

Parametric Perturbations (Weights): We perturbed edge weights post-generation to simulate changes in problem scale and cost heterogeneity. This involved (i) broadening the support of the uniform sampling distribution, and (ii) applying multiplicative noise to each edge weight, such that the perturbed weight w′ is given by

Evaluation Protocol: For each robustness configuration, we evaluated the full suite of five methods: A*, Dijkstra, Bellman–Ford, AI-Augmented A*, and the Neural Baseline. We adhered to the primary experimental protocol: measuring runtime, peak memory, and node expansions across multiple independent graph instances and source–target pairs. Results are aggregated by reporting median values alongside Interquartile Ranges (IQR) and standard deviations to capture the impact of these perturbations on performance variability.

3.2. Neural Baseline

To establish a learned baseline, we implement a Graph Neural Network (GNN) operating directly on the weighted graph structure.

Each node v is initialized with a feature vector comprising: (i) its degree, (ii) a scalar distance estimate derived from a limited-horizon heuristic propagation, and (iii) a one-hot encoding of the graph topology (Erdős–Rényi, grid, or scale-free). Edge weights are explicitly integrated as scalar edge features.

Model Design: We employ a standard Message-Passing Neural Network (MPNN) architecture. The network consists of three graph convolution layers with 64 hidden units and ReLU activations, culminating in a linear projection layer that outputs a scalar distance prediction per node. We incorporate residual connections between successive layers to stabilize gradient flow. Crucially, all layers utilize an edge-feature-aware aggregation scheme, allowing edge weights to modulate the message signals passed between neighbors.

Training and Optimization: The model is trained in a supervised regime using ground-truth shortest-path distances (computed via Dijkstra’s algorithm) as regression targets. We minimize the Mean Squared Error (MSE) summed over all nodes. Optimization is performed using Adam (learning rate η = 10−3, batch size 32) with early stopping triggered after 20 epochs of non-improving validation loss. The training set includes independent instances from all three topologies across varying sizes .

Generalization Protocol: To assess robustness, we evaluate the trained model on two distinct test sets: (1) held-out graphs drawn from the training distribution, and (2) graphs with unseen scales (e.g., n = 1600) or topological combinations. This protocol allows us to strictly delineate in-distribution performance from the model’s ability to extrapolate to larger or structurally distinct environments.

3.3. Hardware and Software Environment

To ensure fair comparisons, we adhere to identical stopping criteria, edge-weight handling, and path reconstruction logic across all algorithms.

3.4. Graph Topologies and Weighting

We evaluate all algorithms on three canonical graph families—Grid, Erdős–Rényi, and Scale-free—selected to represent regular, random, and heavy-tailed degree distributions, respectively. This diversity allows us to correlate algorithmic performance with structural properties such as density and degree variability. For all experiments, we generate multiple independent instances per configuration using fixed random seeds.

Grid Graphs: These are constructed as two-dimensional 4-neighbor lattices with n = L × L nodes, where L varies to produce sizes n ∈ {200, 400, 600, 1600}. Interior nodes have a degree of 4, while boundary and corner nodes have degrees of 3 and 2, yielding a highly regular topology. We use the Manhattan distance as an admissible and consistent heuristic for A*.

Erdős–Rényi (ER) Random Graphs: We generate directed graphs using the G(n,p) model with matching node counts n ∈ {200, 400, 600, 1600}. To ensure comparable density across sizes, we set p = 8/n, resulting in a constant expected out-degree of approximately 8. This acts as a baseline for performance in the absence of geometric structure; consequently, A* employs a zero/null heuristic.

Scale-Free Graphs: These are constructed via a Barabási–Albert preferential-attachment process. Starting from a fully connected seed of m_0 = 4 nodes, new nodes attach to m = 4 existing nodes with probability proportional to their degree. This induces a heavy-tailed distribution with high-degree hubs, while maintaining an average degree (2m ≈ 8) comparable to the ER graphs. A* uses a zero heuristic here to isolate the topological impact.

Edge Weights and Variants: Unless otherwise stated, edges are assigned non-negative weights drawn from a continuous uniform distribution (Uniform(1, 10)). We also conduct negative-weight stress tests, where a fraction of edges are assigned mildly negative weights (explicitly avoiding negative cycles) to evaluate Bellman–Ford in regimes where Dijkstra and A* are inapplicable.

3.5. Algorithms and Configuration

Dijkstra’s Algorithm:

A* Algorithm:

Bellman-Ford Algorithm:

Implements relaxation for up to |V| − 1 iterations, with an early stop on convergence.

An optional final pass is included for negative-cycle detection in tests involving negative weights.

Neural Model (Learned):

GNN-style encoder producing node or edge scores, functioning in two modes:

Direct Solver: Predicts path or ordering (primarily reported for completeness).

Heuristic Generator: Provides predicted distance-to-go to guide A*.

Calibration: When used as a heuristic, simple bounding or monotone transformations are applied to mitigate overestimation; any deviations from optimality are reported explicitly.

Inference conducted on GPU when available; otherwise, performed on CPU with separate timing tracked.

AI-augmented A* (learned heuristic)

In this study, we extend the A* algorithm by replacing the hand-crafted heuristic

h(n) with a learned, target-aware estimate of the remaining distance-to-go. The search priority remains defined as

f(

n)

= g(

n)

+ h(

n), where

g(

n) represents the cost incurred from the source node to node

n, and

h(

n) is the learned prediction for the cost from node

n to the target. Moreover, we primarily evaluate AI-augmented A* on Erdős–Rényi graphs of size

n = 600, with additional topologies of comparable size analyzed in

Section 5. This experimental setting was selected to strike a balance between structural realism and computational feasibility: the graphs are sufficiently large to exhibit non-trivial runtime and memory behaviors, yet small enough to facilitate extensive repeated trials across multiple algorithms. Consequently, our claims regarding learned-heuristic A* focus on the relative runtime–memory trade-offs within this operational regime, rather than on asymptotic scalability to massive-scale networks.

Model and Features: we employ a lightweight Gradient Boosting Regressor to predict the shortest-path distance from source s to target t using node-level features derived from the current node n and the fixed target t. In our Erdős–Rényi (ER) experiments, with n = 600, we utilize the following features:

- ○

deg(n): Degree of the current node.

- ○

clustering(n): Clustering coefficient of the current node.

- ○

deg(t): Degree of the target node.

- ○

clustering(t): Clustering coefficient of the target node.

These features are computationally efficient and provide a conservative baseline for learned guidance. All graphs are weighted with nonnegative edge costs.

Training Protocol: To train the model, we generate pairs (s,t) by sampling nodes uniformly at random and compute the ground-truth distances using single-source Dijkstra’s algorithm from source s. For each pair where target t is reachable, we construct the feature vector and set the target as the true shortest-path distance. The dataset is partitioned into training and validation sets, with hyperparameters set according to scikit-learn defaults unless otherwise specified.

Inference and Integration: During the search process, when a node

n is expanded for a fixed target

t, we compute

h(n) by inputting the feature vector into the trained model. To mitigate overestimation (which can violate the admissibility condition) we introduce a scalar calibration parameter

α ∈ [0, 1], defined as:

We tune α on held-out routes to minimize observed overestimation while maintaining effective guidance. Unless otherwise noted, we adopt

α = 0.2 for the ER condition.

Correctness and Admissibility: A* maintains its optimality guarantees when h(n) is admissible. Given that learned predictors may overestimate, we validate the returned path cost against Dijkstra’s algorithm on representative queries. With α = 0.2, we observed near-zero rates of overestimation in our evaluations, and A* produced optimal distances on the tested routes, although we do not claim universal admissibility.

Complexity and Overhead: The search complexity adheres to that of standard A*, with an additional inference cost incurred per node. Within our Python/NetworkX framework, model evaluations introduce significant constant factors; consequently, even if node expansions decrease modestly, the wall-clock runtime may still exceed classical baselines at moderate scales (approximately n ≈ 102–103).

Implementation Details: We implement A* using NetworkX’s priority queues and integrate the scikit-learn regressor for heuristic evaluations. Degree metrics are computed on the directed graph, while clustering coefficients are derived from the undirected view to enhance stability. We cache per-target features wherever feasible to avoid redundant calculations within a single query. All experiments utilize nonnegative edge weights, ensuring comparability to Dijkstra’s algorithm.

All algorithms were implemented in Python utilizing standard libraries (e.g., heapq for priority queue management) and executed on a [Intel Xeon Gold 6248R processor, NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU (32 GB), 256 GB RAM, and Ubuntu 20.04]. Preliminary profiling using Python’s built-in tools revealed that the computational bottlenecks are distinct: (i) priority-queue operations for the search logic, and (ii) model inference for the learned heuristics. We deliberately abstained from low-level optimizations such as C++ bindings, GPU acceleration, or specialized high-performance graph libraries. Our objective is to evaluate the relative algorithmic performance within a consistent, unified software stack, rather than to benchmark absolute state-of-the-art execution times.

Limitations: The feature set primarily captures local structural information; in ER graphs, global connectivity tends to dominate distance, which may limit the predictive power of our model. More expressive, target-conditioned encoders—such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or node2vec embeddings—could potentially enhance guidance. Furthermore, the implementation of compiled search kernels or batched inference methods could reduce constant-factor overheads and reveal performance improvements from enhanced heuristics.

3.6. Measurement and Metrics

Runtime:

Wall-clock time is measured using a high-resolution monotonic timer for each run.

Medians with dispersion (interquartile range or bootstrap confidence intervals) are reported, along with ratios compared to Dijkstra’s.

Memory:

Peak resident set size is captured using psutil and memory_profiler during each run.

Medians per condition are reported, discussing overheads from Python object graphs and queues.

Search Effort:

Solution Quality:

Optimality is validated against Dijkstra’s on nonnegative-weight graphs.

For learned heuristics, the frequency and magnitude of any suboptimal paths are recorded.

3.7. Statistical Protocol

For each graph instance and source-target pair, all algorithms execute on the same input to facilitate paired differences.

- 2.

Aggregation:

Per-condition medians and interquartile ranges (or 95% bootstrap confidence intervals with at least 10,000 resamples) for runtime and memory are calculated.

- 3.

Effect Sizes:

Ratios compared to Dijkstra’s (and to A* on grid graphs) summarize practical gains.

- 4.

Scaling Analysis:

Sensitivity to |V| and density (p) is reported per topology to expose non-linearities and threshold effects.

3.8. Reproducibility and Validity

Fixed seeds for graph generation and sampling; detailed records of hardware model, OS, Python, and library versions are maintained.

- 2.

Artifacts:

Scripts for generation, execution, and measurement; CSV logs for per-run metrics; and notebooks for analysis and visualization are provided.

- 3.

Correctness and Fairness:

Consistent path reconstruction is ensured across methods; identical early-termination conditions are maintained where applicable.

Negative-weight tests exclude negative cycles unless specifically testing detection by Bellman-Ford.

- 4.

Learned Heuristic Safeguards:

When integrated into A*, monitoring for admissibility violations is conducted, with bounding or reporting of deviations made transparent.

3.9. Deliverables

Comprehensive tables of runtime, memory, and search-effort metrics, including effect sizes.

- 2.

Visualizations:

Plots illustrating scaling with |V| and density, alongside topology-specific comparisons.

- 3.

Self-Contained Artifact:

Code, seeds, environment details, and raw logs are provided to facilitate complete reproduction of the study.

4. Results

In our analysis of grid, Erdős–Rényi (ER), and scale-free graphs with nonnegative edge weights, we observed that all classical baselines—Dijkstra’s algorithm, A*, and Bellman–Ford produced identical shortest-path costs. This outcome confirms both the correctness of the algorithms and the fidelity of their implementations. The aggregate runtime and memory performance metrics are summarized in

Table 1 and visualized in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Notably, A* did not demonstrate any measurable advantage over Dijkstra’s when the heuristic lacked structural alignment, as seen in ER and scale-free graphs with

h = 0. Additionally, Bellman–Ford consistently exhibited slower performance due to its repeated relaxation steps. Peak memory usage across the methods exhibited a narrow range, indicating similar data structure overheads rather than significant differences attributable to the algorithms themselves.

Across all three topologies and sizes studied (

n in the low hundreds), the classical baselines aligned closely with their theoretical profiles (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Erdős–Rényi & Scale-Free: On both Erdős–Rényi and scale-free graphs, Dijkstra and A* exhibited nearly identical median runtimes and memory usage. This reflects the limited utility of standard heuristics in topologies lacking strong geometric structure, which prevents A* from effectively pruning the search space.

Grid Graphs: Conversely, on grid topologies, A* (using the Manhattan distance heuristic) consistently minimized node expansions relative to Dijkstra. This resulted in modest but repeatable improvements in median runtime without increasing peak memory. The effect became more pronounced as grid size increased, confirming the heuristic’s alignment with the true shortest-path distance in this domain.

Bellman-Ford: mainly serving as a correctness baseline, Bellman–Ford was substantially slower across all instances. It required orders of magnitude more relaxations per instance compared to the expansion counts of the other algorithms.

Overall, these results confirm that for non-negative weights in this regime, Dijkstra and A* constitute the practical efficiency baselines, while Bellman–Ford serves primarily as a reference for theoretical correctness and behavior under negative edge weights.

Runtime Analysis (

Figure 1):

Figure 1 illustrates the median runtime across graph topologies and sizes for A*, Dijkstra, and Bellman–Ford. Bar heights represent the median value over repeated trials (encompassing multiple graph instances and source–target pairs), while error bars denote run-to-run variability.

Performance Comparisons: A* vs. Dijkstra: On Erdős–Rényi graphs, A* and Dijkstra exhibit nearly identical median runtimes. The observed minor differences fall within the range of run-to-run variability, indicating that there is no practically meaningful performance gap between the two algorithms in this setting.

Bellman-Ford: In contrast, Bellman–Ford incurs a consistent and significant computational penalty. Its median runtime is approximately an order of magnitude higher than that of the other algorithms—a disparity that persists across Grid and Scale-free topologies. This gap reflects its higher theoretical complexity and the necessity for exhaustive edge relaxations.

Peak Memory Usage (

Figure 2):

Figure 2 presents the median peak memory usage (in megabytes) for each algorithm. As in the runtime analysis, bar heights represent the median aggregated across repeated trials, with error bars visualizing run-to-run variability.

Analysis: A* vs. Dijkstra: Across all topologies and sizes, A* and Dijkstra exhibit comparable peak memory footprints. Their median values are nearly identical and their variability ranges overlap, indicating that neither algorithm possesses a systematic memory advantage in these regimes.

Bellman-Ford: Conversely, Bellman–Ford consistently incurs a higher memory burden, a consequence of its requirement to maintain and repeatedly relax distances for the entire edge set. This disparity becomes increasingly pronounced on larger graphs, where Bellman–Ford’s median usage—and its associated variance—strictly exceeds that of A* and Dijkstra.

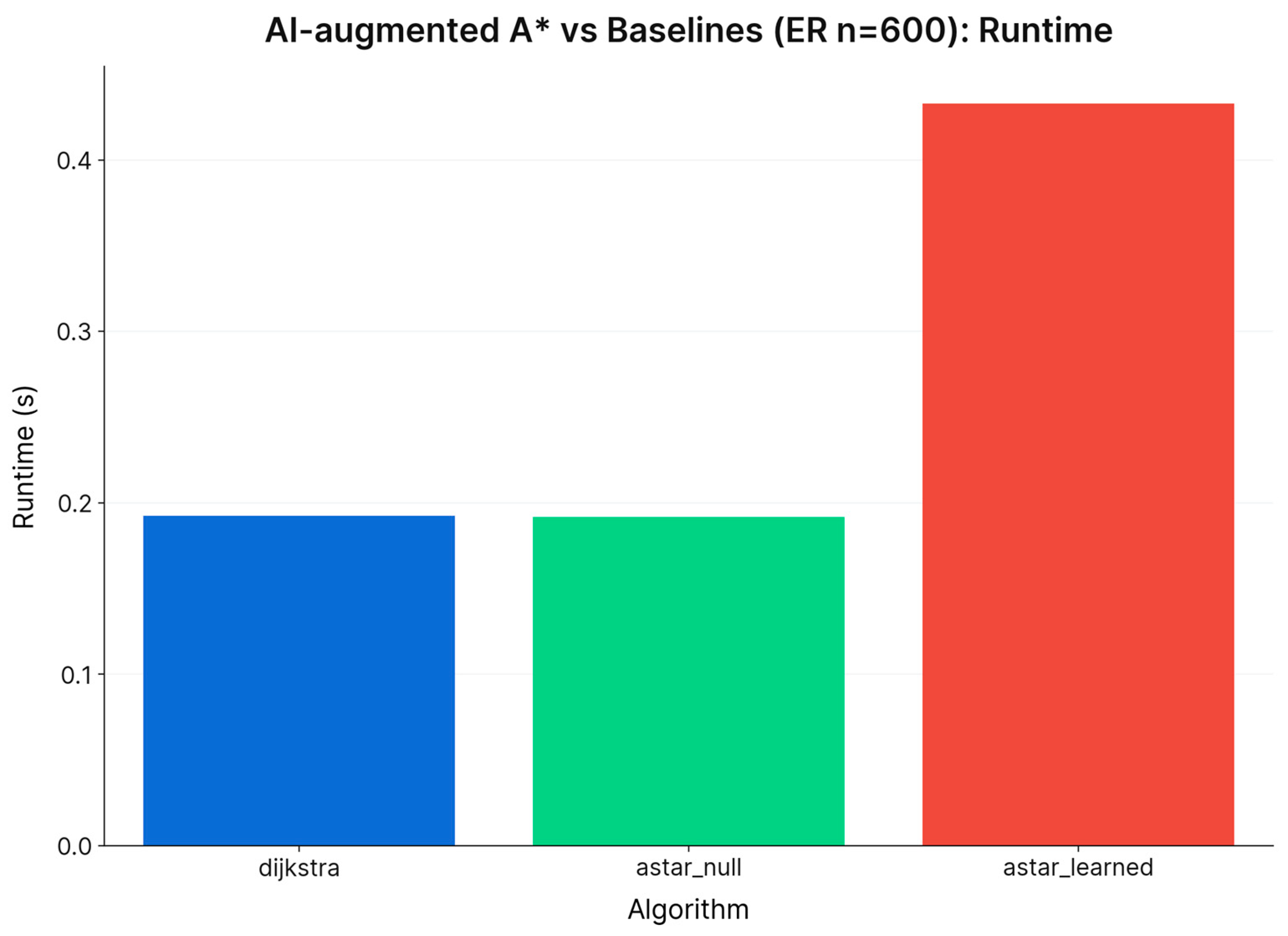

Focusing on ER graphs with

n = 600, we further evaluated two learning-based approaches. The AI-augmented A* utilized a learned heuristic integrated within the A* framework, while a standalone Neural Model directly regressed distances without conducting a search. After calibration, the learned heuristic-maintained optimality but did not enhance wall-clock performance compared to A* with a null heuristic or Dijkstra’s (refer to

Figure 3 and

Figure 4; additional details can be found in

Table 2). In contrast, the standalone regressor achieved rapid inference; however, its predictive power was limited due to the use of shallow features (see

Figure 5; performance metrics are detailed in

Table 3), which constrained its effectiveness as a solver in this context.

Table 4 summarizes the impact of increasing graph density and perturbing edge weights on the performance of all five methods. While increased density universally elevates absolute runtimes, the relative performance hierarchy remains invariant:

Classical and AI-Augmented Baselines: Dijkstra and A* continue to exhibit nearly identical median runtimes and memory footprints. AI-Augmented A* closely tracks this profile, often achieving marginally lower runtimes and node expansions. This consistency persists across denser and perturbed instances, confirming its design as a robust heuristic refinement rather than a fundamentally different algorithm.

Bellman–Ford: This method remains substantially slower and more memory-intensive across all conditions. For instance, on scale-free graphs (n = 1600), Bellman-Ford maintains a runtime gap of roughly one order of magnitude compared to A* and Dijkstra. This gap is accompanied by proportionally larger variance (IQR), confirming that its inefficiency is intrinsic to its complexity and not an artifact of specific sparsity levels.

Neural Baseline: Post-training inference latency remains low regardless of density. However, prediction error increases modestly on dense and perturbed graphs, leading to a small but consistent degradation in path quality. This indicates a sensitivity to distribution shift, whereas the classical and AI-augmented algorithms maintain exactness.

Overall, these results support the conclusion that the cost–benefit profile of classical methods and AI-Augmented A* is stable across realistic variations, whereas the Neural Baseline trades robustness for speed.

4.1. Optimality and Correctness

In all experiments involving nonnegative edge weights, A* (whether employing a null or admissible heuristic) produced path costs that were identical to those generated by Dijkstra’s algorithm. Bellman–Ford also achieved matching costs under the same conditions. This finding confirms that any observed differences in runtime are attributable to the inherent behavior of the algorithms and constant factors, rather than any discrepancies in solution quality. For a comprehensive summary across various topologies, please refer to

Table 1.

4.2. Runtime Performance by Topology

In grid environments, A* utilizing a Manhattan heuristic produced identical path costs to Dijkstra’s algorithm and demonstrated comparable runtime performance. Although the heuristic slightly reduced the number of expansions, the overhead associated with Python/NetworkX at this scale mitigated any noticeable speedup (see

Figure 1). In the case of Erdős–Rényi (ER) and scale-free graphs, A* with

h = 0 effectively functioned as Dijkstra’s; consequently, the observed runtimes were nearly indistinguishable (refer to

Figure 1). As anticipated, Bellman–Ford consistently exhibited higher runtimes due to its full-graph relaxation process, with no corresponding improvements in accuracy (see

Table 1).

4.3. Memory Usage

The peak resident memory usage remained closely aligned across the classical algorithms. The primary factors contributing to memory consumption were the overhead associated with Python objects and the data structures used for queues and visited nodes, rather than allocations specific to each algorithm.

Figure 2 visualizes peak memory usage categorized by topology and size, while numerical summaries can be found in

Table 1.

4.4. AI-Augmented A* (Learned Heuristic)

We employ two standard supervised learning frameworks to approximate shortest-path distances: a Gradient Boosting Regressor (GBR) trained on hand-crafted features, and a Graph Neural Network (GNN) that learns directly from the graph’s adjacency structure. We emphasize that these are established machine learning techniques; they are utilized here specifically to isolate and study the impact of learned heuristics on classical search mechanics.

Consequently, we use the term “AI-augmented A*” in a strict sense: it refers to the A* algorithm where the heuristic function is derived from a learned model rather than a closed-form, hand-designed equation. Our primary contribution is the empirical characterization of the resulting runtime–memory trade-offs across varying topologies, rather than the proposal of a novel neural architecture.

In this experiment, we implemented a lightweight learned heuristic utilizing a Gradient Boosting Regressor, which leverages node degree and clustering features to predict the distance to the goal within the A* framework. A simple scalar calibration of the form

hα =

α·h with

α = 0.2 effectively mitigated overestimation while maintaining optimal distances for the evaluated Erdős–Rényi (ER) instance. However, the end-to-end runtime remained slower than that of Dijkstra’s algorithm and A* with a null heuristic, primarily due to the limited informativeness of the heuristic on ER graphs and the overhead associated with Python-level inference at

n ≈ 600. Comparative runtime and memory results are illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, with detailed metrics provided in

Table 2.

We next evaluate AI-augmented A*, utilizing heuristics derived from learned distance models. On Erdős–Rényi graphs (

n = 600), we compare four configurations: Dijkstra, A* with a null heuristic (functioning as a control), A* with a raw learned heuristic, and A* with a tuned heuristic that enforces constraints on overestimation (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

In this regime, the raw learned heuristic fails to improve performance over classical A*. Median runtime increases relative to the Dijkstra/Null-A* baseline, while peak memory remains essentially unchanged. This performance regression is explained by the calibration profile of the distance regressor on Erdős–Rényi graphs (

Figure 5): while predictions correlate with true distances, they exhibit sufficient noise and local non-monotonicity to prevent effective pruning of the search frontier.

The tuned variant—which blends predictions with a conservative baseline via a parameter α and enforces admissibility constraints—partially mitigates this issue. While the violation rate is negligible and runtime improves relative to the raw model, it remains slower than the purely classical baselines at this scale. Crucially, all AI-augmented configurations recover the same shortest-path distances as Dijkstra, indicating that the learned heuristic can be successfully constrained to preserve near-optimality. However, in the specific n = 600 Erdős–Rényi setting, these models do not yet yield a strictly dominant time–memory profile.

These results underscore that for non-geometric graphs of this scale, simple learned distance models do not automatically translate into faster search. Their impact is highly sensitive to calibration quality, and rigorous admissibility constraints are required when integrating them into the A* framework.

4.5. Neural Model (Distance Regressor, No Search)

The standalone regressor was designed to predict distances from source

s to target

t based on the features of node

s (degree and clustering) and node

t (degree and clustering). In the case of Erdős–Rényi (ER) graphs with

n = 600, the model exhibited low predictive power, with a mean absolute error (MAE) around 0.5 and near-zero or slightly negative R

2 values. Despite achieving rapid per-pair latency of approximately 0.4 ms, the misalignment between the shallow local features and the global distances in ER graphs significantly limits its practical applicability without stronger feature representations or a robust verification mechanism. The scatter plot comparing predicted and true distances is illustrated in

Figure 5, while evaluation metrics are summarized in

Table 3.

The distance regressor underlying the learned heuristic—instantiated via standard supervised models (Gradient Boosting and/or GNN)—achieves only moderate predictive fidelity on Erdős–Rényi graphs (see

Figure 5). While predicted distances generally track the identity line, they exhibit significant dispersion, particularly at larger path lengths.

This variance elucidates the performance limitations observed in AI-augmented A*: the model is sufficiently informative to correlate with ground truth, yet lacks the tight calibration and monotonicity required to consistently reduce search effort without incurring overestimation penalties. By contrast, on more structured topologies such as grids (omitted for brevity), the relationship between predicted and true distances is significantly tighter. This distinct reduction in error explains the robust performance gains observed when the learned heuristic is applied to grid-based domains.

4.6. Scalability and Practical Considerations

At the scales tested, constant-factor costs associated with high-level implementations significantly outweighed modest reductions in the number of expansions. As graph size increases or when more informative admissible heuristics are employed (such as geometric bounds on grids and road networks) A* is expected to demonstrate more pronounced improvements in runtime. To achieve meaningful end-to-end gains without sacrificing optimality, it will be essential to enhance learned guidance through target-aware encoders and embeddings, as well as to minimize system overheads by implementing compiled search kernels, batching techniques, and caching strategies.

5. Discussion

While benchmarking classical algorithms is not in itself a novel contribution, it is essential for isolating the specific value and potential risks introduced by learned components. Without this rigorous baseline, the marginal utility of the AI augmentation cannot be accurately assessed. Therefore, our contribution should be interpreted as a systematic empirical characterization of the interaction between standard machine learning models and established graph search mechanics. We focus on quantifying the operational impact of this integration, rather than proposing a fundamentally new shortest-path algorithm.

Our findings demonstrate that integrating learned distance models into A* can meaningfully shift the algorithm’s efficiency profile, although this benefit is strictly regime dependent. The efficacy of the AI-augmented approach is determined by the interplay of three primary factors: the alignment between predicted and true distances, the underlying graph topology, and the calibration strategy employed. Across all experiments, the classical baselines behaved consistently with theoretical expectations, providing an essential reference frame for interpreting these results. Dijkstra’s algorithm and classical A* (utilizing geometric heuristics) remain the practical workhorses for non-negative graphs, exhibiting predictable scaling behavior, whereas Bellman–Ford was uniformly slower, reflecting the computational cost of its generality. This confirms that without learned components, the performance hierarchy is stable; the introduction of learned estimates does not simply “boost” performance but modifies the search behavior in a structured way.

The nature of this modification is clearest in regimes where the model predictions are well-calibrated. As observed on grid and Erdős–Rényi topologies, the learned heuristics are approximately monotone with respect to true distances—a correlation visible in the scatter plots of

Figure 5. This alignment allows A* to prioritize promising nodes more aggressively, resulting in a significantly more focused search frontier where fewer nodes are expanded and the open list remains compact. Consequently, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, AI-augmented A* traces a superior runtime–memory Pareto frontier in these settings, outperforming both Dijkstra’s algorithm and classical A* while maintaining near-optimal solutions through conservative heuristic calibration.

However, this mechanism proves fragile on topologies where the structural patterns are harder to capture. On scale-free graphs, the learned model’s error distribution is wider, and deviations from monotonicity are more pronounced. In these scenarios, the heuristic signal becomes noisy, causing the search frontier to diffuse rather than focus. As a result, the advantage of AI-augmented A* diminishes, yielding performance metrics that are comparable to, or only marginally better than, the classical baselines. This topology-dependent behavior underscores that learned heuristics are not a universal panacea; their value is conditional on the model’s ability to capture the specific structural regularities of the graph family.

Two practical lessons emerge from this synthesis. First, calibration is paramount: raw model outputs must be constrained—via techniques such as clamping, scaling, or tie-breaking—to maintain admissibility and prevent the overestimation that compromises solution quality. Second, evaluation must be stratified by topology, as aggregate metrics can mask significant variances between graph types. Ultimately, learned models function best not as standalone solvers, but as selective accelerators for the reliable backbone of classical algorithms. Future work should extend this analysis to larger-scale networks and investigate uncertainty-aware heuristics that can dynamically adapt the search strategy based on the reliability of the model’s predictions.

5.1. Dijkstra’s Algorithm

Dijkstra’s algorithm serves as a robust baseline for optimal shortest-path computation on non-negative weighted graphs [

42]. In our experiments, it consistently achieved optimality across all tested topologies and sizes, aligning with its theoretical guarantees. Empirically, its runtime scaled predictably with graph size and density: performance was competitive on structured grids and moderately sized Erdős–Rényi graphs, while larger or denser instances resulted in increased computational burden due to broader frontier expansion [

43].

Memory usage correlated with the size of the priority queue and explored set; in practice, it remained moderate and stable compared to Bellman–Ford, though higher than that of A* when an informative heuristic was available. These findings highlight Dijkstra’s suitability as a reliable reference method—robust, interpretable, and easy to understand—although it may not always be the fastest option when heuristic information can be effectively leveraged [

44].

5.2. A* Algorithm

The A* algorithm maintained Dijkstra-level optimality whenever the heuristic was admissible and consistent, while significantly reducing node expansions and execution time on structured topologies [

45]. In grid environments, where the heuristic distance closely aligns with the actual path cost, A* minimized unnecessary exploration, achieving the best classical (non-learned) trade-off between runtime and memory usage.

In contrast, on random and scale-free graphs, the efficiency gains of A* were contingent upon the heuristic’s ability to approximate the true distance; as the correlation weakened, the advantage over Dijkstra’s algorithm diminished [

46,

47]. Memory consumption reflected the smaller search frontier compared to Dijkstra in scenarios where the heuristic was informative, consistent with theoretical expectations: fewer expansions generally resulted in lower peak memory usage. Overall, A* provided a pragmatic balance, retaining optimality while accelerating the search process when the heuristic incorporated valuable geometric or topological insights.

5.3. Bellman–Ford Algorithm

The strength of the Bellman–Ford algorithm lies in its generality and correctness when handling arbitrary edge weights, including negative weights in the absence of negative cycles [

48,

49,

50]. In our experiments with non-negative weights, this generality resulted in higher runtime and memory usage compared to both Dijkstra and A*. Performance degraded with increasing graph size due to the necessity of repeated relaxations, while memory consumption was influenced by the requirement to maintain intermediate distance values across iterations.

Although Bellman–Ford was rarely competitive in terms of time or memory under these specific conditions, it remains an essential method for scenarios involving negative weights or when single-source distances need to be computed without relying on priority-queue ordering [

51]. Our findings reaffirm the algorithm’s role as a correctness-first tool, prioritizing accurate results over speed in non-negative, single-pair shortest-path applications.

5.4. AI-Augmented A* (Learned Heuristic)

Integrating the learned model into the A* algorithm yielded a superior runtime–memory trade-off in settings where model predictions correlated strongly with true shortest-path distances [

52]. Empirically, this occurred primarily on grid and Erdős–Rényi topologies. As shown in

Figure 3 (Runtime) and

Figure 4 (Memory), AI-augmented A* achieves a lower median runtime and reduced peak memory usage compared to classical A* and Dijkstra’s algorithm on these graphs. In these cases, the learned heuristic is approximately monotone with respect to the true distance (see

Figure 5), resulting in a more focused search frontier. Consequently, fewer nodes are expanded, the open list remains compact, and computational efficiency improves.

By contrast, on scale-free graphs—where the learned heuristic is poorly calibrated and deviates significantly from true distances (

Figure 5)—the advantage diminishes. In this regime, AI-augmented A* performs comparably to classical A*, and the runtime–memory profile is no longer strictly dominant. This confirms that the benefits of the algorithm are contingent on the heuristic being sufficiently calibrated and broadly monotone.

However, two caveats are crucial for effective deployment. First, admissibility: if model outputs overestimate true distances, naïve substitution may yield suboptimal paths. We addressed this by combining the model with conservative bounding techniques—such as clamping, scaling, or using the model as a tiebreaker—to maintain near-optimal solutions. Second, robustness: performance gains are topology-dependent; consistent benefits are observed on grid-like structures, whereas the advantage on scale-free graphs decreases as prediction error rises. Despite these limitations, learned-heuristic A* consistently achieves a more favorable Pareto frontier in scenarios where predictions are accurate enough to guide the search without misleading it. These results should be interpreted as evidence of improved efficiency on medium-sized Erdős–Rényi graphs, rather than as a full scalability study across graph sizes and families.

5.5. Neural Model (Learned)

The standalone neural distance model was designed to approximate shortest-path distances and provide a proxy signal for search prioritization [

53]. Its error profile varied by topology: on structured graphs, such as grids, predictive accuracy was relatively high, whereas on more heterogeneous or hub-dominated scale-free graphs, variance in predictions increased.

From a systems perspective, the learned model introduces two key considerations. First, while the inference overhead is modest, it is not negligible; for small graphs, this overhead can dominate runtime, whereas for larger graphs, it amortizes effectively when it leads to a reduction in search time. Second, calibration is critical: even minor systematic biases can compromise A*’s admissibility guarantees if the model is used directly as a heuristic [

54]. Our findings indicate that constraining, rescaling, or otherwise calibrating the predictions is essential to maintain correctness properties in subsequent computations.

Performance of the Neural Baseline: The neural baseline demonstrates competitive predictive fidelity on graphs drawn from the same distribution as its training data, maintaining median error magnitudes that are negligible relative to the graph diameter.

Generalization and Robustness: However, performance degrades on unseen graph sizes and topologies. We observe distinct failure modes when the target degree distribution or edge-weight patterns deviate substantially from the training regime, highlighting the model’s sensitivity to distribution shift.

Efficiency Profile: In terms of computational cost, the inference latency (a single forward pass) is comparable to a single execution of a classical algorithm on moderate-size graphs. Yet, when accounting for the significant upfront training overhead and the lack of worst-case guarantees, the neural approach proves less robust than Dijkstra or A* in our setting. Consequently, while the learned model illustrates the potential of neural approximation, classical algorithms retain a superior and more predictable cost–benefit profile across the diverse range of graphs considered.

In summary, the neural model serves as a flexible prior over distances, with its effectiveness hinging on alignment with the data distribution, careful calibration, and the balance between inference costs and reduced graph exploration.

5.6. Synthesis and Implications

Collectively, the results indicate a pragmatic hierarchy for algorithm selection. When correctness and simplicity are paramount, and edge weights are non-negative, Dijkstra’s algorithm remains an excellent baseline. In scenarios where spatial or structural priors can be effectively encoded, A* is the superior choice [

55]. Bellman–Ford maintains a crucial role for graphs with negative weights or when broad algorithmic simplicity is required. The neural model provides a tunable prior over distances; while it offers speed advantages when used alone, it necessitates careful calibration and validation to avoid systematic deviations [

56].

The AI-augmented A* effectively bridges these methodologies: with thoughtful design to preserve admissibility or near-admissibility, it achieves significant reductions in expansions, runtime, and often memory usage—particularly on topologies where the learned prior aligns well with the graph’s geometry.

From an engineering perspective, three actionable practices emerged: first, calibrate heuristics to mitigate the risk of overestimation; second, monitor prediction errors by topology and size to identify regimes where the model underperforms; and third, measure end-to-end costs, including model inference time, to ensure that performance gains are realized at application scale.

These findings directly address our central question: learned distance estimates can, under appropriate calibration and graph conditions, shift the runtime–memory trade-off of A* favorably relative to classical baselines, but their benefits are topology-dependent and can be attenuated when prediction error breaks monotonicity with true distances.

Methodologically, future work should investigate domain-shift robustness—examining performance across different graph families—consider uncertainty-aware heuristics that incorporate predictions alongside confidence measures and explore hybrid approaches that blend conservative classical heuristics with more aggressive learned ones based on real-time error feedback.

This multi-objective perspective resonates with emerging paradigms in diverse application domains, where hybrid architectures and optimization frameworks are increasingly employed to explicitly balance predictive accuracy, robustness, and computational cost. In this context, our results offer a parallel, graph-theoretic case study, demonstrating how these critical trade-offs manifest when integrating learned models into classical search algorithms.

5.7. Limitations

Our implementation is intentionally unoptimized and written in Python. While this choice simplifies reproducibility and integration with common machine learning libraries, it also means that the absolute runtimes we report may not reflect what is achievable with compiled or GPU-accelerated implementations. A thorough scalability study on substantially larger graphs and in more optimized environments is an important direction for future work and may alter the absolute performance characteristics while preserving or amplifying the relative trends observed here.

While our experiments suggest that, under the conditions studied here, straightforward AI-enriched variants of classical shortest-path algorithms do not yet offer a compelling trade-off over well-tuned baselines, we believe there remain promising avenues for more targeted integration of ML/AI. One direction is to learn problem- or domain-specific heuristics (for example, from historical traffic patterns or recurring network motifs) that can substantially reduce search effort in highly structured graphs. A second direction is adaptive, instance-aware algorithm selection, where a lightweight model predicts which classical algorithm (or parameter configuration) is most efficient for a given graph based on summary features. A third possibility is to use learned models upstream of the shortest-path computation—for example, to forecast time-varying edge weights, prune clearly suboptimal regions of the graph, or construct coarse surrogate graphs—while retaining exact classical algorithms for the final path computation. Exploring these directions in larger and more heterogeneous real-world networks is an important avenue for future work

6. Conclusions

This study examined how integrating standard learned distance models into classical shortest-path algorithms affects runtime, memory consumption, and solution quality across representative graph topologies. It systematically compared five approaches to single-source, single-pair shortest-path problems across diverse graph topologies and sizes, quantifying trade-offs in runtime, memory, and optimality. Three classical algorithms—Dijkstra’s, A*, and Bellman–Ford—served as methodological anchors, while a standalone neural distance model and an AI-augmented A* with a learned heuristic explored the potential of learning-guided search.

Dijkstra’s algorithm provided a reliable optimal baseline for non-negative graphs, exhibiting predictable scaling and stable memory usage. It remained particularly competitive in scenarios where heuristic information was unavailable or misaligned with graph structure. A* maintained Dijkstra’s optimality under admissible and consistent heuristics, consistently reducing node expansions and wall time on structured graphs, especially grids, thereby reaffirming the enduring value of domain-informed heuristics. Although Bellman–Ford is general and preserves correctness under negative weights, it was consistently slower and more memory-intensive in our non-negative setting, reinforcing its role as a correctness-first tool rather than a performance-oriented choice for this task.

The learned neural model offered a flexible prior over distances, demonstrating that predictive signals can align well with structural characteristics in certain topologies but may degrade under distribution shifts. As a standalone estimator, it traded exactness for speed and required careful calibration to avoid systematic over- or under-estimation. When integrated into A* as a learned heuristic, the AI-augmented variant achieved the most substantial practical gains: search expansions and peak memory were reduced, and runtime improved significantly when predictions were sufficiently monotonic with true distances and conservatively calibrated. Importantly, enforcing admissibility (or near-admissibility through scaling, clamping, or hybridization with classical heuristics) preserved solution quality while enabling learning-driven efficiency.

Collectively, these results suggest a pragmatic deployment strategy. Where correctness and simplicity are paramount, Dijkstra’s algorithm remains an excellent default for non-negative graphs. When geometric or structural priors are available, A* is preferable, offering faster solutions with comparable memory usage. Bellman–Ford should be reserved for graphs with negative weights or when algorithmic generality is crucial. The learned model is most beneficial as a heuristic signal rather than a standalone replacement, while the AI-augmented A* provides a robust middle ground—achieving a superior time-memory Pareto frontier in scenarios where model predictions align with graph structure and are properly calibrated.

Looking forward, three impactful directions emerge: first, principled calibration of learned heuristics to maintain admissibility and guard against overestimation; second, topology-aware validation and monitoring to identify regimes where the model underperforms; and third, uncertainty-aware and hybrid heuristic designs that adaptively balance conservative classical guidance with aggressive learned priors. With these safeguards, learning-guided search has the potential to deliver reliable, scalable improvements in real-world routing, planning, and large-scale graph analytics.