Enhancing Cybersecurity Readiness in Non-Profit Organizations Through Collaborative Research and Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. NPO Cybersecurity Readiness Background

2.1. Existing Research Landscape

- Practitioner-Oriented Resources: Organizations such as the Nonprofit Technology Enterprise Network (NTEN) [20], TechSoup, and the National Council of Nonprofits [14] publish cybersecurity guides and toolkits. These resources offer checklists and templates but typically lack empirical validation or comparative analysis.

- Incident Reports and Threat Intelligence: Cybersecurity breach databases, vendor-generated threat reports, and media coverage document cyberattacks targeting NPOs [4]. These sources focus on incident response rather than proactive readiness assessment, offering limited guidance for prevention.

- Corporate and Enterprise Security Research: The academic cybersecurity literature predominantly examines large organizations with dedicated IT departments. While frameworks such as NIST’s [21] or ISO 27001 [22] offer valuable guidance, their application to resource-constrained NPOs requires significant adaptation that the existing literature does not address.

- NPO Technology Research: Studies examining technology adoption in the NPO sector tend to focus on digital fundraising, social media, and donor management systems. Cybersecurity readiness, when mentioned, is typically treated as a secondary concern.

2.2. Lack of Synthesized, Actionable Reviews

2.3. Specific Knowledge Gaps in Current Literature

- Limited Sub-Sector and Geographic Analysis: There is little research examining how readiness varies by NPO sub-sector or geographic location (urban vs. rural) [11,24]. Specifically, while rural Pennsylvania NPOs face “severe financial strain” [11], this region serves as a critical microcosm for the broader urban–rural digital divide. Validating our framework within this diverse demographic allows us to test the “Geographic & Resource Disparities” gap empirically.

- Impact of High Turnover: Research has not adequately explored how high staff turnover [23] and subsequent “knowledge loss” impact the sustainability of security practices.

- Lack of Scalable Frameworks: Research on adapting existing frameworks (like NIST) for small NPOs with limited technical expertise is scarce.

- Absence of Practical Quantification: There is little academic guidance on practical, effective cyber-risk assessment models for this sector, which often defaults to vague “high-medium-low” estimates.

2.4. Justification for This Systematic Review

3. Systematic Literature Review Mapping Methodology

- Objectives and research questions;

- Search strategy;

- Search criteria;

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria;

- Search and selection procedure;

- Data extraction and synthesis;

- Important characteristics of selected primary studies.

3.1. Objectives and Research Questions

- RQ1. What are the top cybersecurity risks for NPOs, how do these risks impact their services, and what are the methods to identify and fix these issues?

- RQ2. What affordable cybersecurity practices, especially in employee training, can NPOs with limited resources adopt? How do knowledge gaps differ across NPO sectors?

- RQ3. What factors influence cybersecurity readiness in NPOs, like location (urban vs. rural), budgets, and IT skills? How do things like cyber insurance and third-party agreements affect their security?

- RQ4: How can NPOs assess their cybersecurity preparedness and resilience?

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Search Criteria

- Cybersecurity;

- NPOs;

- What practices we implement;

- How we assess readiness.

3.4. Search Filter Criteria

- It was published within the last five years (post-COVID-19).

- It is an article or a journal article.

- It is within the domain of computer science, engineering, library and information science, mathematics, and statistics.

- It is written in English.

- It is peer-reviewed.

- It is a full text.

3.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- IC1: It is written in English.

- IC2: It is relevant and applicable to NPOs.

- IC3: It is within the scope of the research questions.

- IC4: It belongs to a group of recognized research studies.

- IC5: It is a technical report, journal, or a conference paper.

- EC1: The paper does not meet all the inclusion criteria.

- EC2: The paper does not address cybersecurity readiness.

- EC3: The paper’s focus is not primarily on or applicable to NPOs.

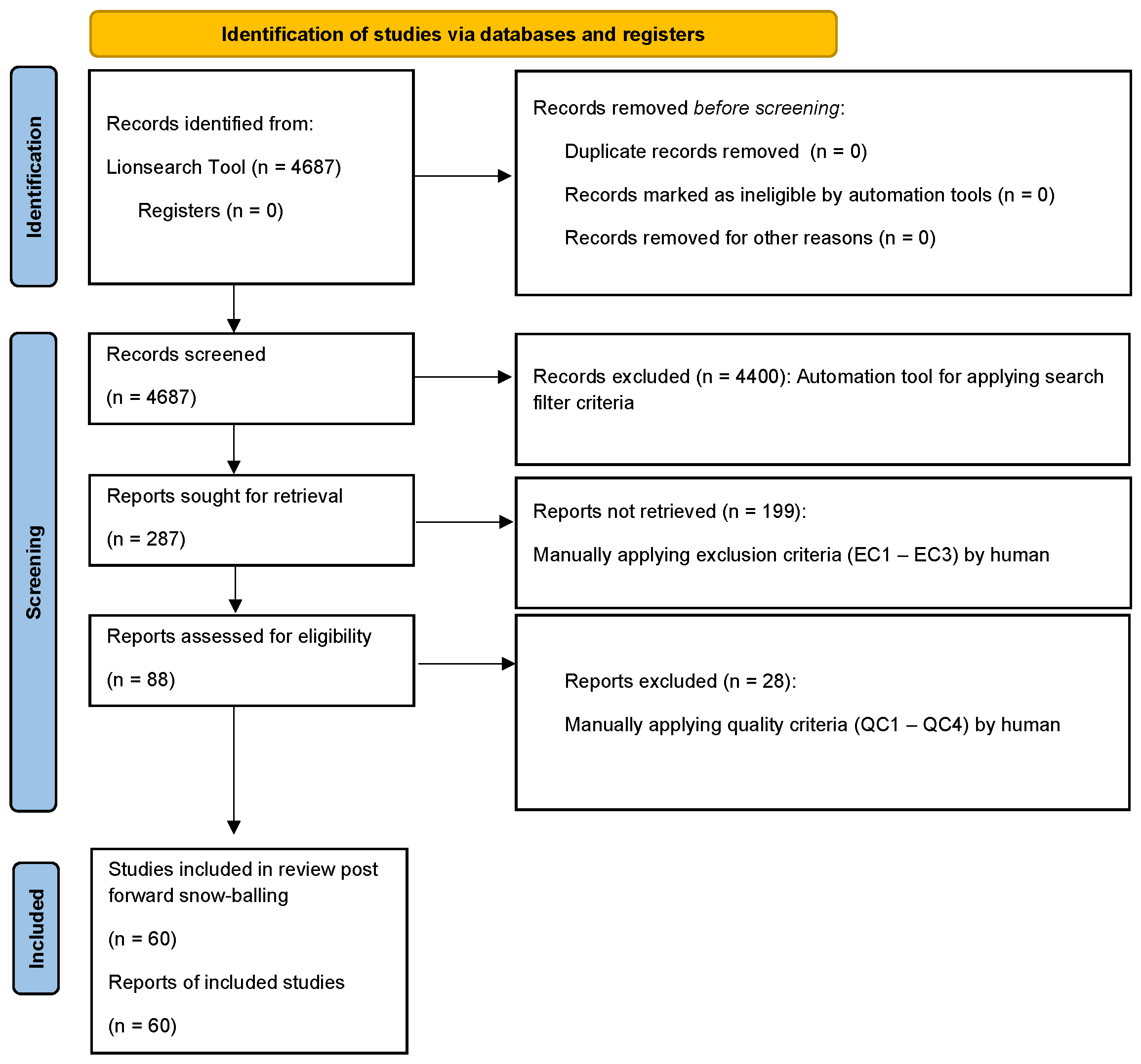

3.6. Search and Selection Procedure

- QC1: Is the study’s focus on cybersecurity issues unique to NPOs? (1 or 0);

- QC2: Does the research offer useful information or suggestions that are pertinent to NPOs? (1 or 0);

- QC3: Are the research findings backed up by definite facts or evidence? (1 or 0);

- QC4: Does the study make sense given NPOs’ resource constraints? (1 or 0).

4. Findings

4.1. Visualization Rationale and Reading Guide

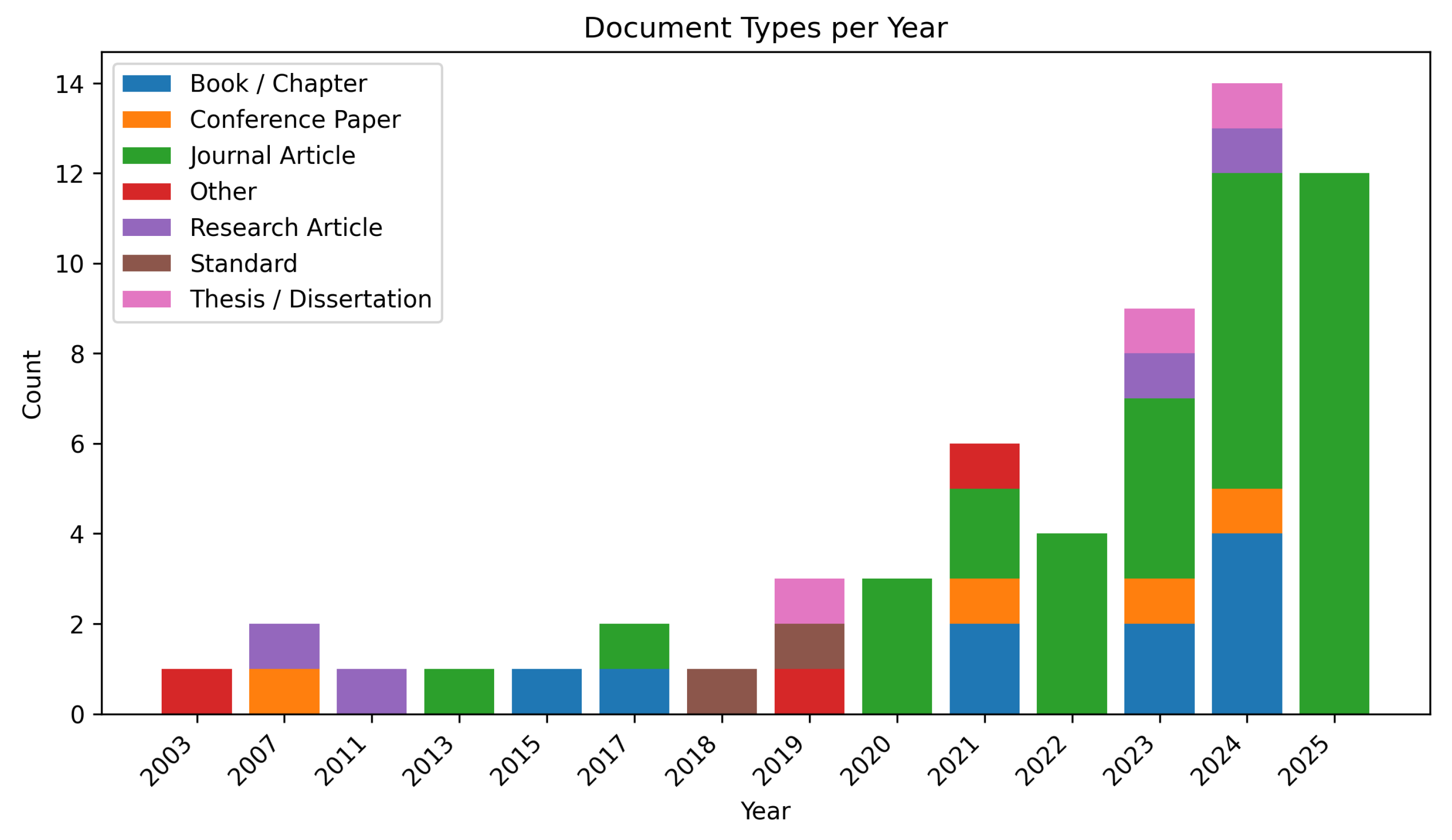

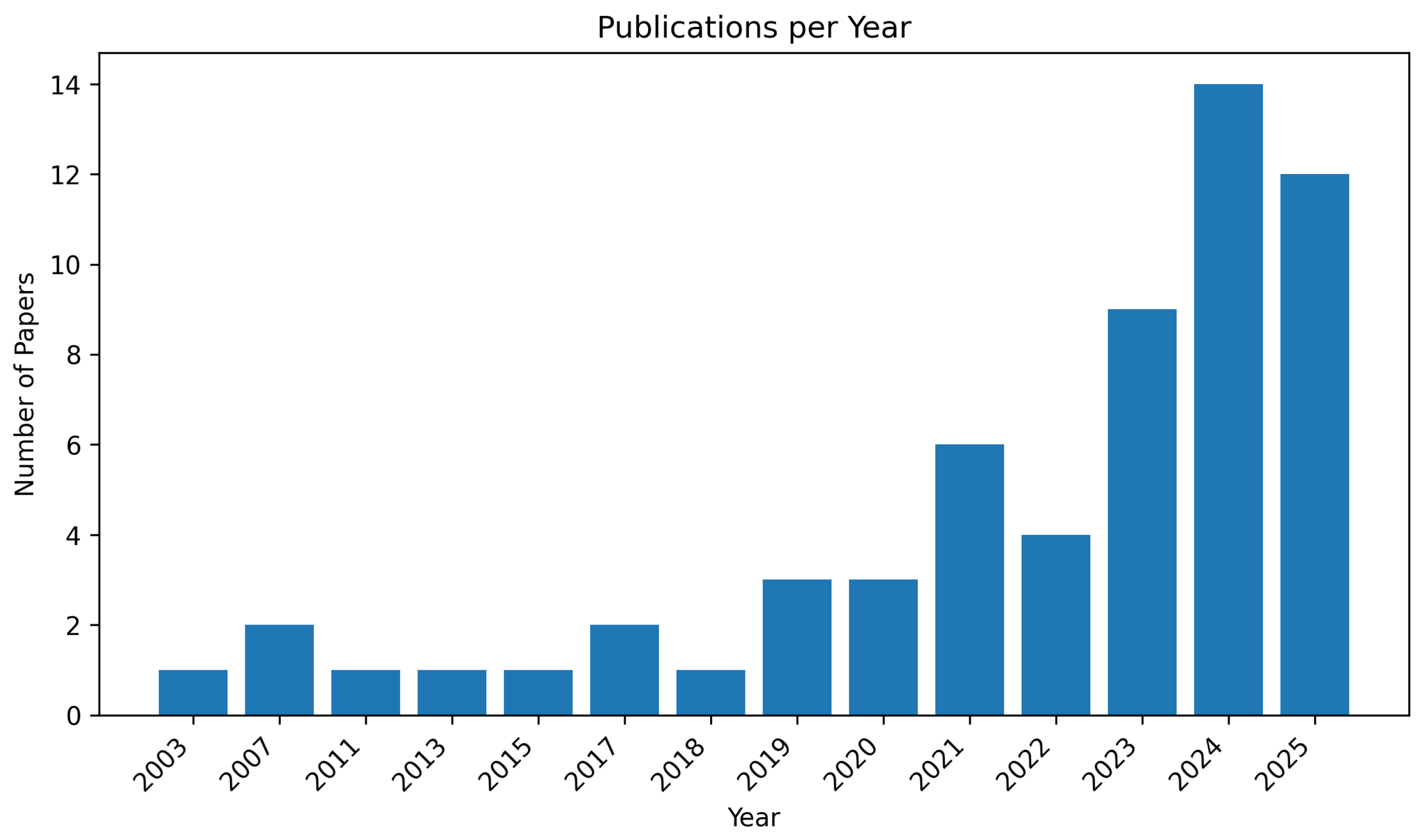

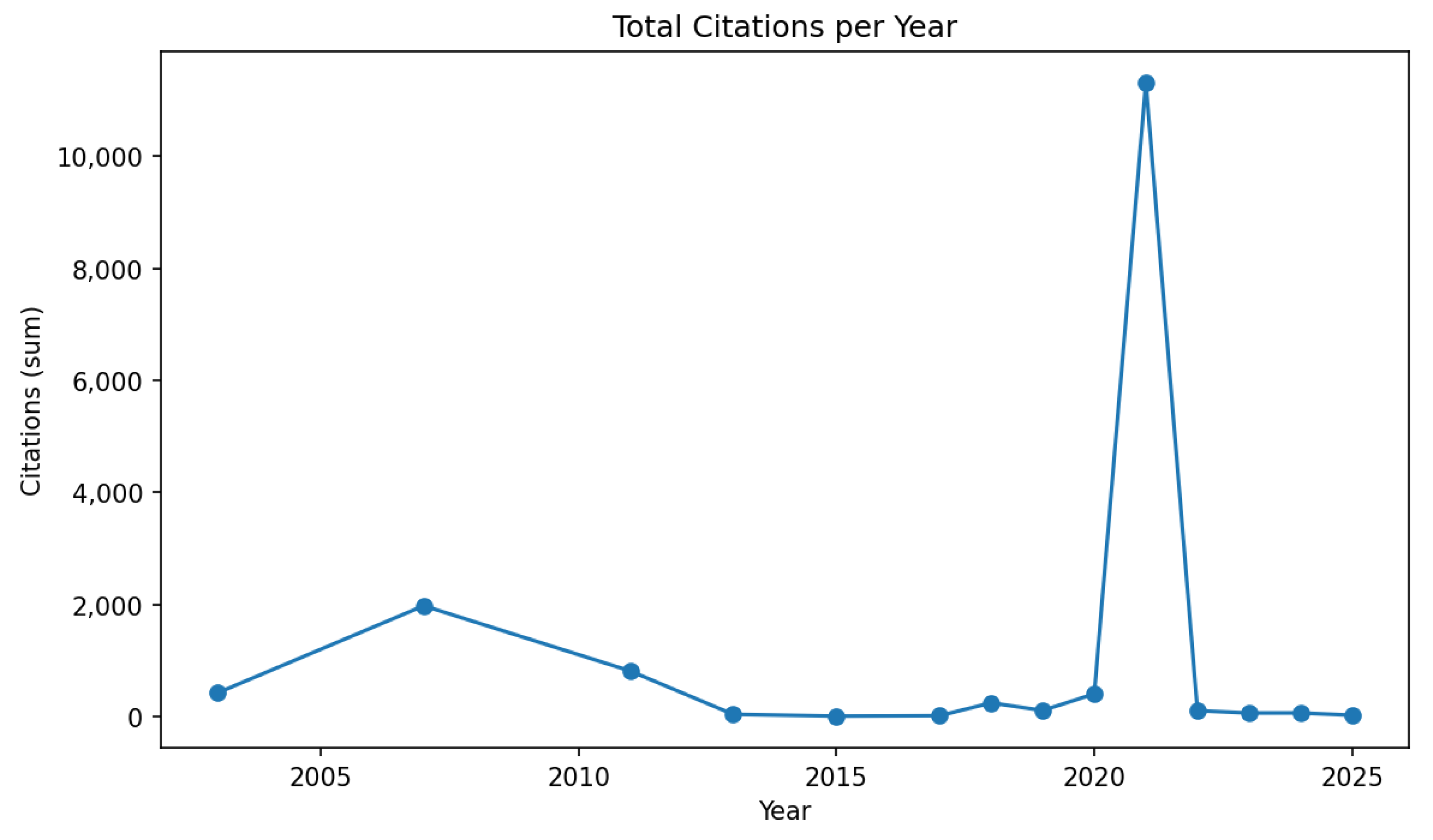

- Temporal coverage. We first plotted the number of publications per year from 2003 to 2025 and the total citations per year for the same period. Together, these two figures are presented in this section. The figures let us distinguish between volume-driven growth in NPO cybersecurity scholarship and influence-driven scholarship (i.e., papers that the field actually cites).

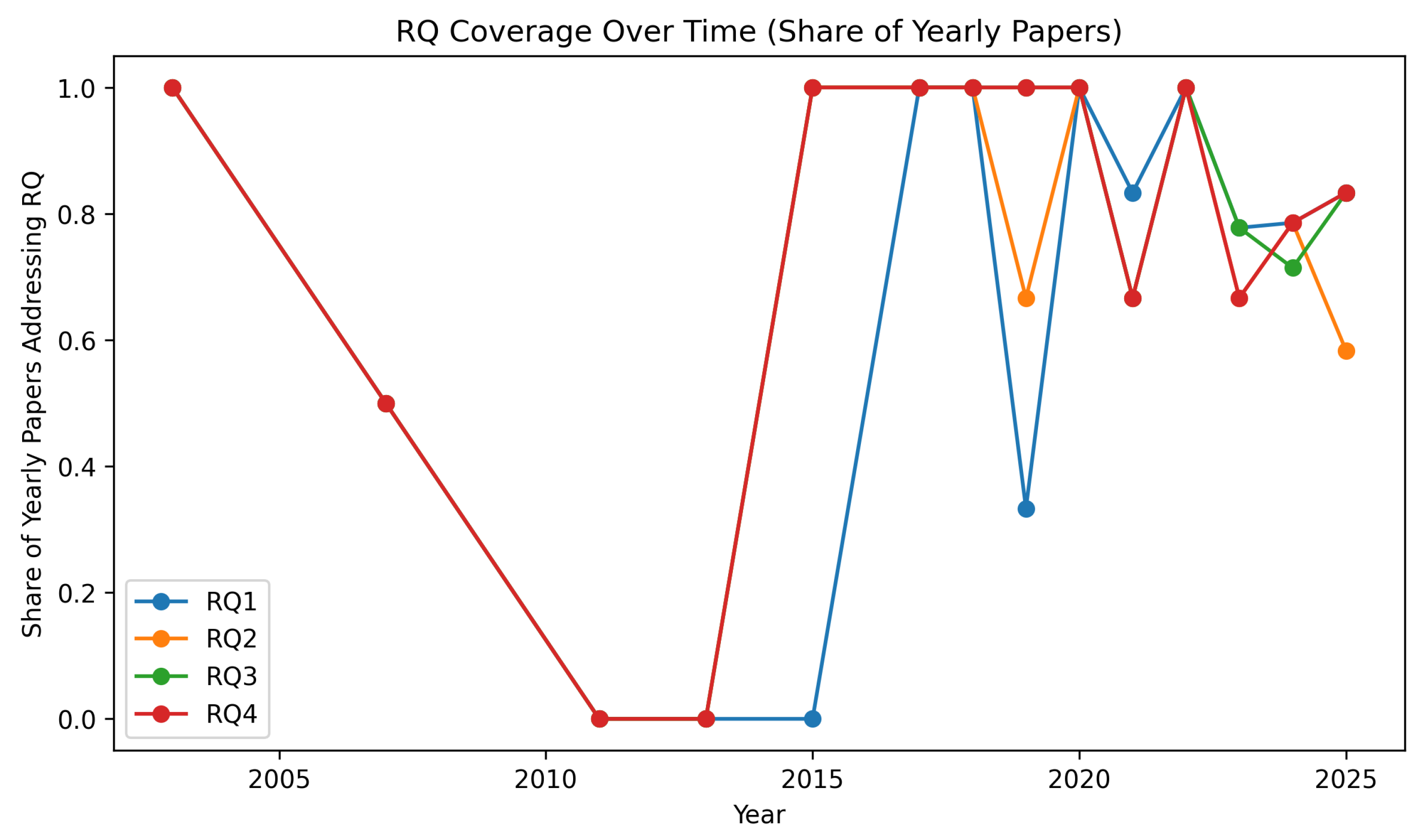

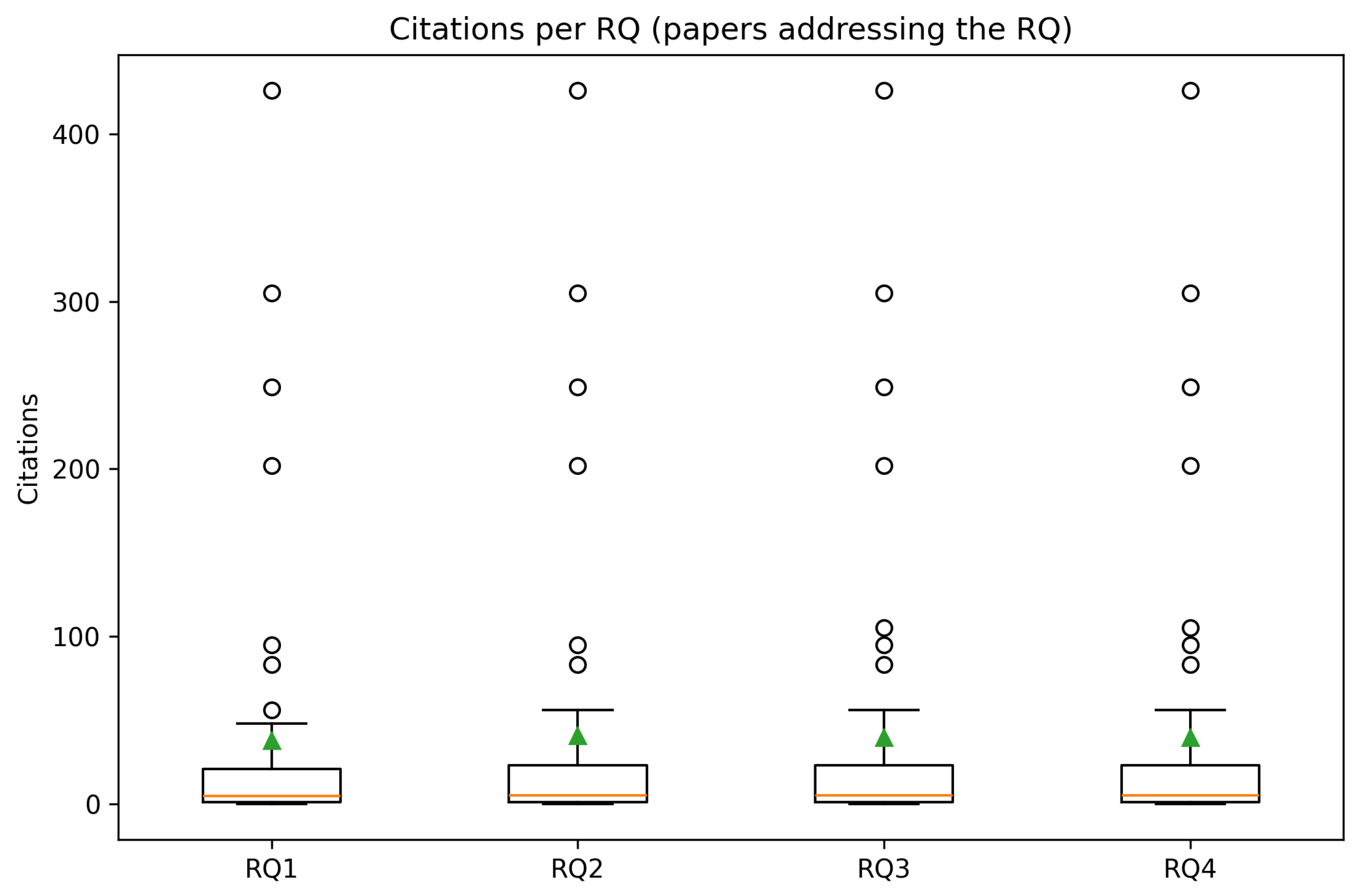

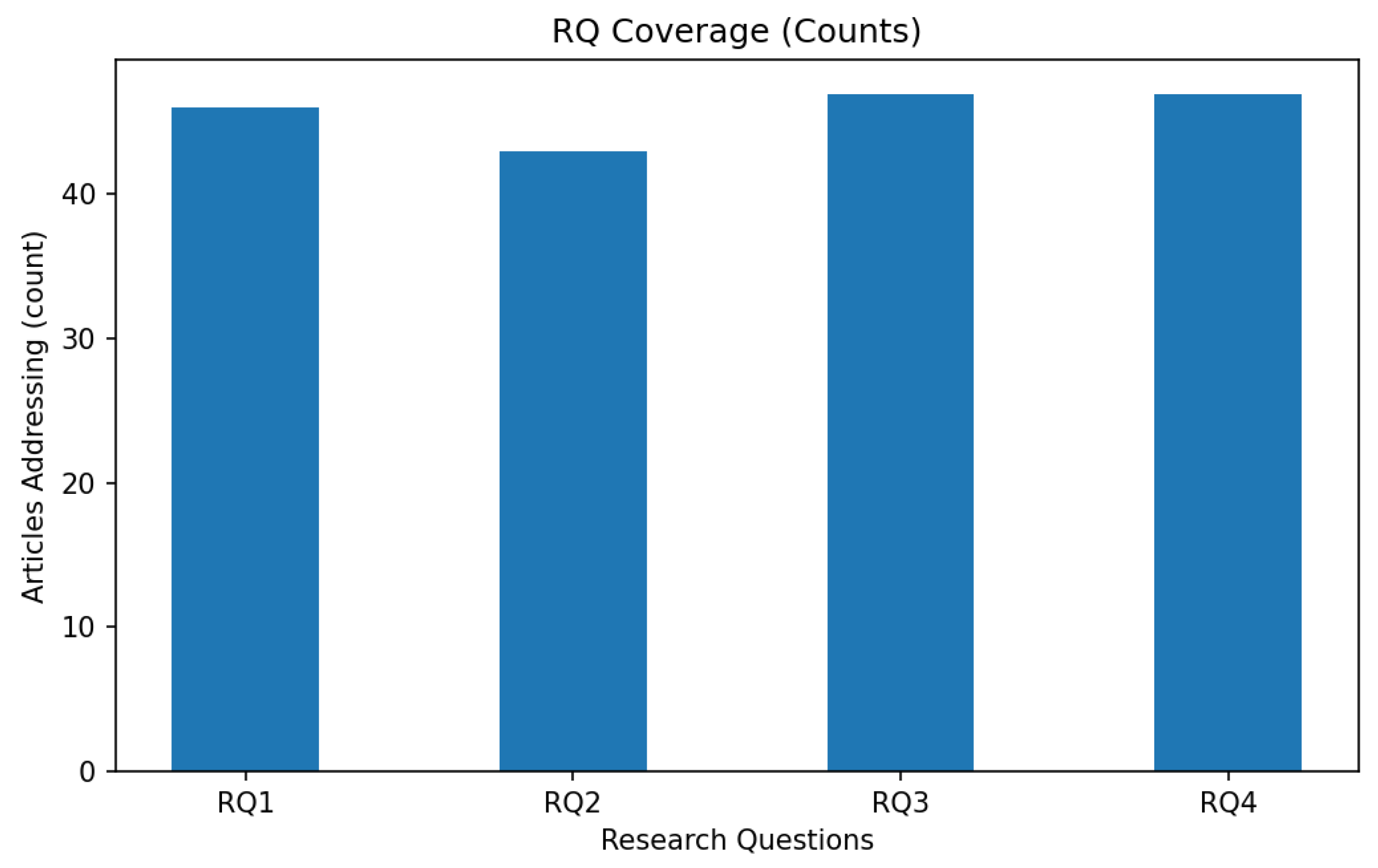

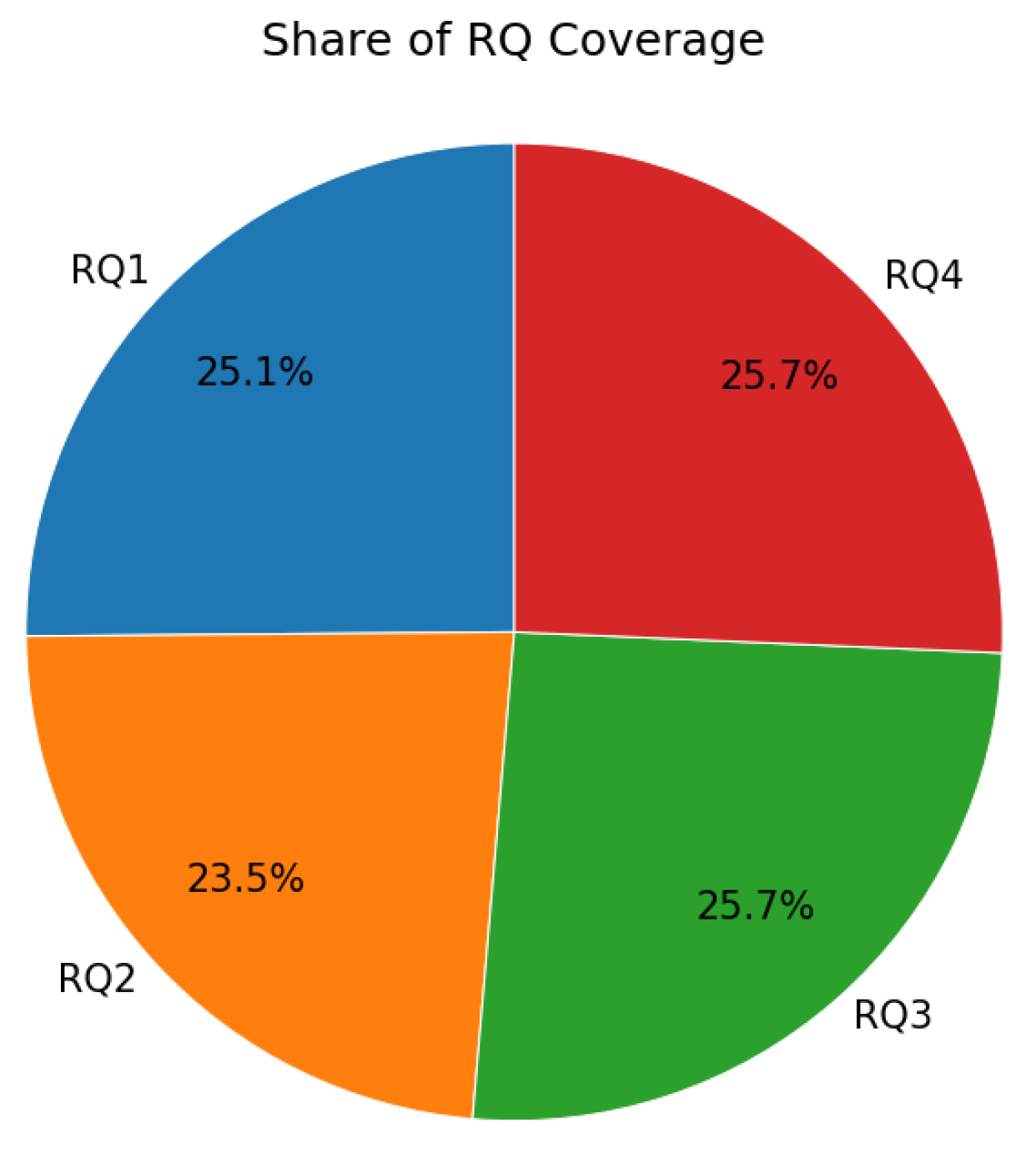

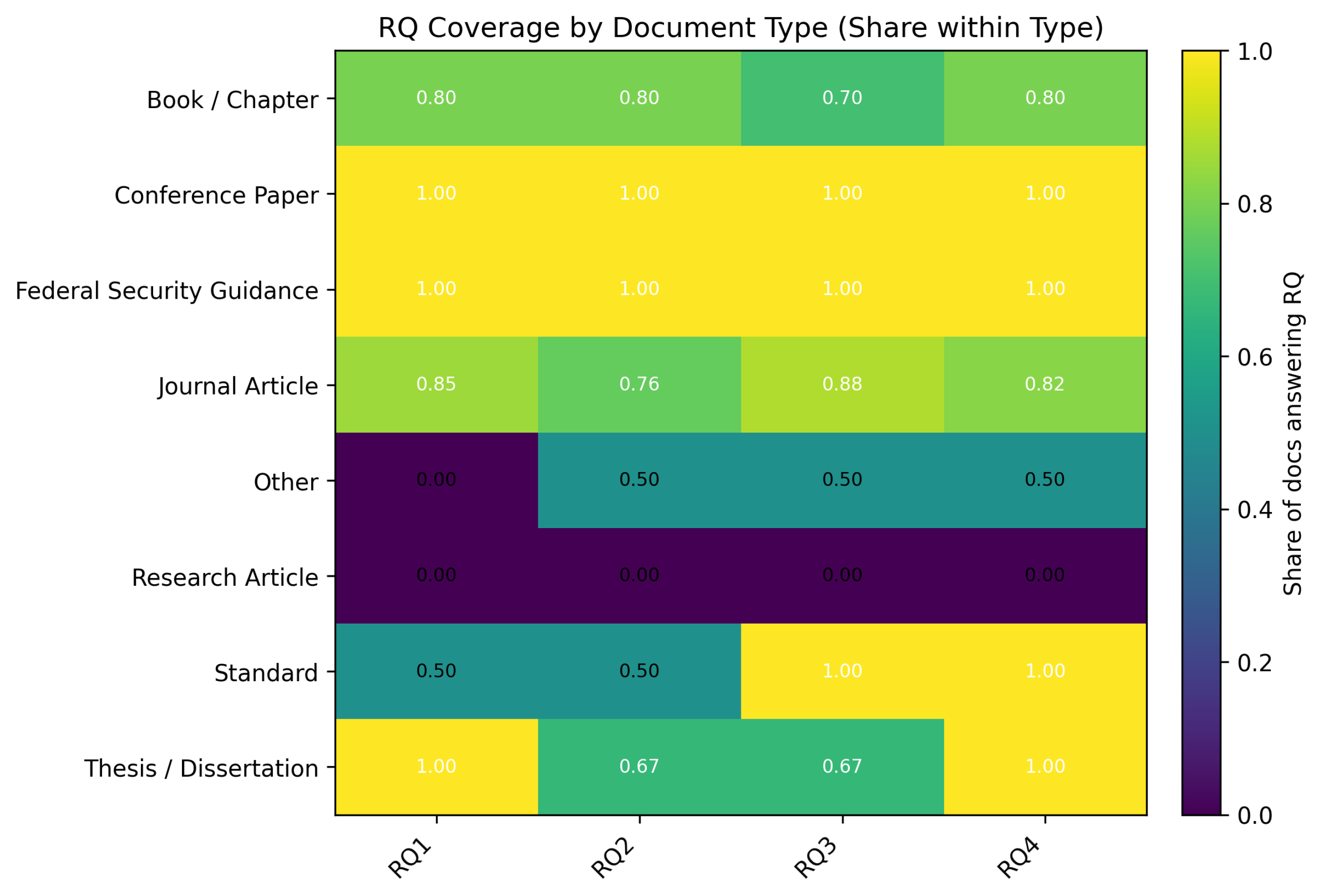

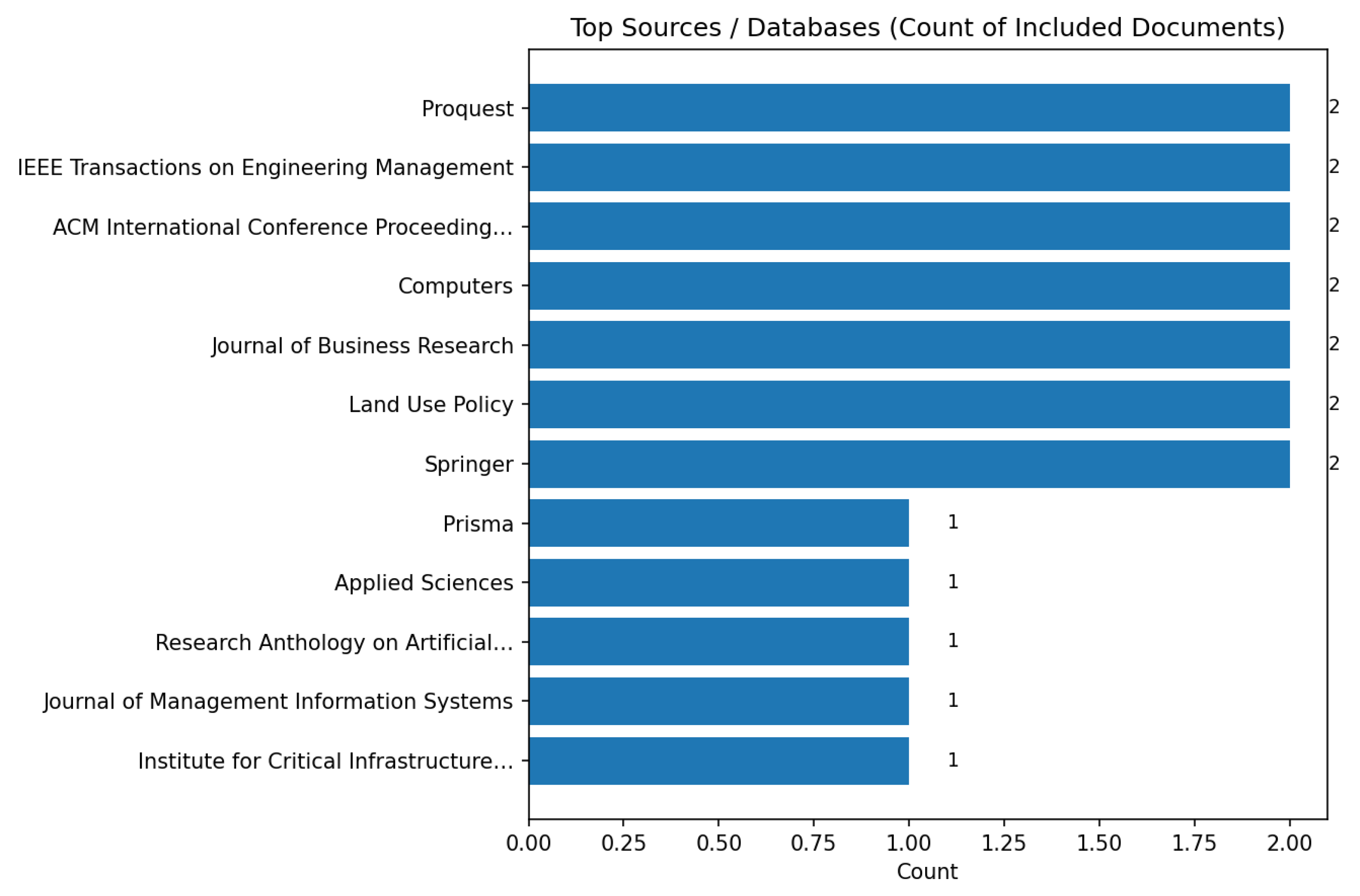

- Alignment with research questions. Because our protocol was driven by four research questions (RQ1–RQ4), we needed to test whether the 60 papers actually “landed” on those questions. We therefore built (a) a simple count of how many articles address each RQ shown in Section 4.2; (b) a share-of-corpus view showing the same information as percentages shown in Section 4.2; and (c) a document-type vs. RQ heatmap shown in Section 4.3 to detect whether, for example, guidance documents systematically answer different questions than empirical papers.

- Source/database provenance. Because the NPO cybersecurity literature is fragmented across computer science, information systems, public administration, and policy outlets, we wanted to know where the included studies came from. The paired panel in Section 4.5 shows both the long-tail reality (a few venues supply most of the studies) and the near-field view after removing the two large aggregators.

- Quality/attention signals. Citation counts for small and young corpora are noisy, so instead of using citation counts to rank papers, we summarized the distributions of citations for papers that answered each research question (Section 4.4). This is especially useful because some research questions (notably RQ1) sit closer to operational security practice and are more likely to be cited soon after publication, while others (RQ4) lag.

- RQ coverage over time. Finally, we asked whether the field “moves” in unison or whether attention drifts between questions over time. We normalized share of yearly papers so that we can see that 2023 is a clear inflection point in which more than one RQ is being answered in the same year.

- Document-type growth. To connect the SLR narrative (that NPOs increasingly rely on fast, web-available guidance) to the actual corpus we found, we plotted stacked counts of document types per year. This confirms that the spike in 2024 is not only more papers, but also more journal articles and more federal/quasi-federal guidance.

4.2. RQ1: Top Cybersecurity Risks for NPOs

What Are the Top Cybersecurity Risks for NPOs, How Do These Risks Impact Their Services, and What Are the Methods to Identify and Fix These Issues?

Where the Visualizations Fit for RQ1

4.3. RQ2: Affordable Cybersecurity Practices and Training

What Affordable Cybersecurity Practices, Especially in Employee Training, Can Nonprofits with Limited Resources Adopt? How Do Knowledge Gaps Differ Across Nonprofit Sectors?

Where the Visualizations Fit for RQ2

- Conference papers and guidance as integrators. Both categories exhibit uniformly high coverage (1.00) across RQ1–RQ4, indicating that comprehensive treatments of risks, practices, readiness, and assessment are available in these outlets. For guidance, note the smaller absolute count—coverage is high within type, not necessarily in volume.

- Journal articles as depth providers with a slight RQ2 dip. Journal articles show ∼0.85 (RQ1), 0.76 (RQ2), 0.88 (RQ3), and 0.82 (RQ4). This matches intuition: deeper methodological/governance questions tend to appear in journals, while affordable-practice (RQ2) content is a touch more dispersed across conferences/theses.

- Type-specific emphases. Books/chapters are balanced but lighter on RQ3 (0.70). Standards lean strongly toward RQ3–RQ4 (1.00 each) versus RQ1–RQ2 (0.50/0.50). Theses/dissertations are strongest on RQ1 and RQ4 (1.00) but lower on RQ2–RQ3 (0.67). Research article items in this corpus show 0.00 across cells, and “Other” exhibits partial coverage (0.50 on RQ2–RQ4). Together, these patterns explain why RQ2 appears more sector-sensitive: evidence for affordable practices and training is concentrated in venues that emphasize implementation and short-cycle evaluation.

4.4. RQ3: Factors Influencing Cybersecurity Readiness

What Factors Influence Cybersecurity Readiness in NPOs, Like Location (Urban vs. Rural), Budgets, and IT Skills? How Do Things Like Cyber Insurance and Third-Party Agreements Affect Their Security?

Where the Visualizations Fit for RQ3

4.5. RQ4: Assessing Cybersecurity Preparedness and Resilience

How Can NPOs Assess Their Cybersecurity Preparedness and Resilience?

Where the Visualizations Fit for RQ4

- The Top sources/databases plot (Figure 10), which in our updated corpus shows a highly fragmented landscape with no single dominant aggregator; most venues contribute 1–2 papers each (e.g., ProQuest, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, ACM ICPS, Computers, Journal of Business Research, Land Use Policy, Springer). This matters because assessment tooling for NPOs is often published across heterogeneous outlets rather than within one centralized repository.

- The RQ coverage by document type heatmap (already added as Figure 6) showed that federal standards and guidance are present but thinly coded. This dispersion across sources strengthens the case for our pipeline’s consolidation step (ontology + control graph), which maps disparate guidance back to NIST/CIS so NPO teams can act on it.

4.6. Positioning of Visualizations’ Limitations and Biases

4.7. Envisioned Analysis to Assess Cybersecurity Readiness

4.7.1. Design Principles

- Evidence-grounded: Map every output to explicit sources (survey responses, documents, or guidance) with provenance so that recommendations are auditable.

- Low-friction + low-cost: Favor brief instruments, automation, and defaults already present in common SaaS stacks (per RQ2).

- Action over inspection: Convert findings into short, sequenced sprints with acceptance criteria (assess → decide → implement → rehearse), reflecting RQ4.

- Uncertainty-aware: Report confidence and data coverage; avoid over-claiming for partial or noisy inputs (citation/recency cautions in Figure 3).

4.7.2. Pipeline Overview

- Instrument and sampling. We adapt the MIT Cybersecurity Clinic survey (17 items) [75] and extend it with micro-indicators surfaced by the SLR (e.g., MFA coverage on mission SaaS; backup and restore drills; vendor offboarding cadence; DMARC enforcement). Items are grouped by NIST CSF 2.0 functions (Identify; Protect; Detect; Respond; Recover) and CIS IG1 sub-controls to enable consistent scoring across organizations and time.

- Data intake, normalization, and privacy. Responses are captured via a lightweight web form. Free text is automatically redacted for PII using deterministic regex + dictionary screening; organizations approve redactions before storage. All responses are normalized to a typed schema (org_profile, control_claims, incidents, vendors) for downstream analysis.

- Sector ontology and control graph. We define a minimalist ontology that links risks (phishing, BEC, ransomware), assets (email, donor CRM, file sharing), and controls (MFA, backups, least privilege). Nodes are aligned to NIST CSF 2.0 categories/subcategories and CIS IG1 safeguards; edges encode risk→control mitigations and control→evidence claims. This “control graph” is populated from our SLR coding so that each edge carries literature-backed rationales.

- Information extraction (hybrid). Open-ended answers and policy snippets are parsed with a hybrid approach: (i) rules for high-precision cues (e.g., “% of accounts with MFA”) and (ii) a compact NER/sequence-labeling model (e.g., bert-base fine-tuned on a small, SLR-derived annotation set) to detect entities such as tool names, configurations, and process verbs (“tested restore”, “quarterly review”). Low-confidence extractions are surfaced for one-click human confirmation (active learning loop).

- Readiness scoring with uncertainty. Each subcategory receives a score usingwhere claim reflects self-report, evidence reflects corroboration (e.g., screenshot/log snippet), and rehearsal rewards drills (tabletops/restore tests). We propagate confidence intervals from extraction quality and evidence presence. A small number of must-have IG1 safeguards (MFA on email, tested backups, patch/auto-update) gate the overall maturity band.

- Risk- and cost-aware prioritization. Gaps are ranked by a multi-criteria function:with sector-aware weights (health/education vs. small rural NPOs), reflecting RQ3’s context. Defaults target “high impact, low effort” wins first (MFA, password manager, update cadence, DMARC).

- Recommendations and 90-day action plans. For each top-k gap, the system generates a sprint card with control objective (NIST/CIS reference), exact steps in common SaaS suites, owner, due date, acceptance test, and rollback. Where appropriate, we attach templated scripts/policies and a one-page board brief.

- Evaluation and learning. We assess the following to visualize trends at the function/subcategory level: (a) inter-rater reliability on extractions, (b) face validity via expert review, (c) back-testing on known incidents (do recommended controls align with documented failure points?), and (d) outcome tracking to re-administer at 90/180 days to measure deltas. Models are periodically re-tuned as the corpus grows, with drift monitors for vocabulary and control adoption.

- Deliverables and UX. Outputs include a readiness dashboard (scores, confidence, trend lines), a ranked backlog with sprint cards, and a “board view” summarizing 5–7 indicators (MFA coverage, restore success, open vendor tokens, aged accounts, and phishing-report rate). All artifacts carry provenance links back to the underlying answers/evidence and the relevant literature edges in the control graph.

- Ethics and governance. We implement explicit consent, data minimization, and role-based access to organizational data; only aggregate, de-identified benchmarks are shared publicly. The ontology, annotation guidelines, and scoring rubric are open-sourced to enable replication and third-party audits.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Oro, G.C. The Role and Relevance of Resilience in the Nonprofit Sector: A systematic review of the literature. J. Public Nonprofit Aff. 2025, 11, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesenhahn, E. Nonprofit Organizations: State and Regional Employment Trends. 2025. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2025/article/nonprofit-organizations-state-and-regional-employment-trends.htm (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Faulk, L.; Kim, M.; Derrick-Mills, T.; Boris, E.; Tomasko, L.; Hakizimana, N.; Chen, T.; Kim, M.; Nath, L. Nonprofit Trends and Impacts 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/nonprofit-trends-and-impacts-2021 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Niyonzigira, F. Exploring Nonprofit Organizations’ Successful Compliance Strategies Against Cyber Threats: A Qualitative Study Inquiry. Ph.D. Thesis, Capella University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, A. Cyber-Poor, Target-Rich: The Crucial Role of Cybersecurity in Nonprofit Organizations. 2024. Available online: https://cyberpeaceinstitute.org/news/cyber-poor-target-rich-the-crucial-role-of-cybersecurity-in-nonprofit-organizations/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ferrari, A. Nonprofit Cybersecurity: NIST CSF 2.0 as Exemplar of the ZERO. Master’s Thesis, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OSIbeyond. Why Non-Profits and Associations Are Targets for Cyber Attacks. 2024. Available online: https://www.osibeyond.com/blog/why-non-profits-and-associations-are-targets-for-cyber-attacks/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- The Modern Nonprofit. Nonprofits Are Prime Targets for Cyberattacks—Is Your Organization at Risk? 2025. Available online: https://themodernnonprofit.com/nonprofits-are-prime-targets-for-cyberattacks-is-your-organization-at-risk/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Identity Theft Resource Center. 2023 Annual Data Breach Report Reveals Record Number of Compromises. 2024. Available online: https://www.idtheftcenter.org/post/2023-annual-data-breach-report-reveals-record-number-of-compromises-72-percent-increase-over-previous-high/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Archive, N.R.N. Card and Mobile Payment Industry News. 2021; Issue 1209. Available online: https://nilsonreport.com/content_promo.php?id_promo=16 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Snow, R.; Leach, E.; Tomko, M. The Status of Rural Pennsylvania Nonprofits. 2013. Available online: https://www.rural.pa.gov/getfile.cfm?file=Resources/PDFs/research-report/status_rural_of_nonprofits_2013.pdf&view=true (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- CISRA. Nationwide Cybersecurity Review. 2022. Available online: https://www.cisecurity.org/insights/white-papers/2022-nationwide-cybersecurity-review (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- World, T.E. Tax Exempt World. 2022. Available online: https://www.taxexemptworld.com/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- National Council of Nonprofits. What is a Nonprofit? 2022. Available online: https://www.councilofnonprofits.org/what-is-a-nonprofit (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Omega Systems. Bolstering Nonprofit Cybersecurity & Resilience in Today’s Threat Landscape. 2023. Available online: https://omegasystemscorp.com/insights/blog/bolstering-nonprofit-cybersecurity-resilience-in-todays-threat-landscape/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Global Cyber Alliance. GCA Cybersecurity Toolkit for Mission-Based Organizations. 2025. Available online: https://globalcyberalliance.org/work/gca-cybersecurity-toolkit/gca-cybersecurity-toolkit-for-mission-based-organizations/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Community IT Innovators. Cybersecurity Readiness for Nonprofits: A Practical Playbook. 2024. Available online: https://communityit.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Cybersecurity-Readiness-Playbook-Final-compressed.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jameil, A.K.; Al-Raweshidy, H. Enhancing offloading with cybersecurity in edge computing for digital twin-driven patient monitoring. IET Wirel. Sens. Syst. 2024, 14, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuthan, K.; Gupta, B.B.; Raman, R. Bridging cybersecurity with digital twin technology: A thematic analysis. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A. Cybersecurity for Nonprofits: A Guide. 2020. Available online: https://word.nten.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Cybersecurity-for-Nonprofits_-February-2020.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- NIST. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity Version 1.1. 2018. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.04162018.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- ISO/IEC 27001. Information Security Management. 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/isoiec-27001-information-security.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- HR, N. 2021 Nonprofit Talent Retention Practices Survey. 2021. Available online: https://www.nonprofithr.com/2021talentretentionsurvey/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- McAfee. Cloud Adoption and Risk Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.mcafee.com/enterprise/en-us/forms/gated-form-thanks.html?docID=3804edf6-fe75-427e-a4fd-4eee7d189265 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Schryen, G.; Sperling, M. Literature reviews in operations research: A new taxonomy and a meta review. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 157, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapati, S.; Ahn, M.; Reddick, C. Evolution of cybersecurity concerns: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, Gdańsk, Poland, 11–14 July 2023; pp. 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- ISACA. COBIT 2019 Framework: Introduction and Methodology. 2018. Available online: https://www.isaca.org/resources/cobit (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Dunđer, I.; Seljan, S.; Odak, M. Information Security Awareness in the University Environment: A Focus on Undergraduates. TEM J. 2025, 14, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haastrecht, M.; Sarhan, I.; Shojaifar, A.; Baumgartner, L.; Mallouli, W.; Spruit, M. A threat-based cybersecurity risk assessment approach addressing SME needs. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna, Austria, 17–20 August 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, S.; Green, K.Y.; Johnson, C.; Cooper, J.; Gilstrap, C. An extended TOE framework for cybersecurity-adoption decisions. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 47, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.R.; Allen, R.A.; Samuel, A.; Abdullah, A.; Thomas, R.J. Antecedents of cybersecurity implementation: A study of the cyber-preparedness of UK Social Enterprises. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 69, 3826–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanova, A.; Lace, N. Conceptual Model of the Company’s Cyber Resilience Elements. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2025, 23, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan, B.Y.; Spruit, M. Cybersecurity Standardisation for SMEs: The Stakeholders’ Perspectives and a Research Agenda. Res. Anthol. Artif. Intell. Appl. Secur. 2021, 1252–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Paramita, A.S.; Prabowo, H.; Ramadhan, A.; Sensuse, D.I. Data Governance Model For Nation-Wide Non-Profit Organization. J. Appl. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2023, 5, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawindaran, N.; Jayal, A.; Prakash, E. Exploration of the impact of cybersecurity awareness on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Wales using intelligent software to combat cybercrime. Computers 2022, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQahtan, N.; AlOlayan, A.; AlAjaji, A.; Almaslukh, A. HoneyLite: A Lightweight Honeypot Security Solution for SMEs. Sensors 2025, 25, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, S.; Scott, J. Cybersecurity in non-profit and non-governmental Organizations. Inst. Crit. Infrastruct. Technol. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Stan-Mierzwa/publication/314096686_Cybersecurity_in_Non-Profit_and_Non-Governmental_Organizations/links/58b5672f92851ca13e52a312/Cybersecurity-in-Non-Profit-and-Non-Governmental-Organizations.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Carey-Smith, M.; Nelson, K.; May, L. Improving information security management in nonprofit organisations with action research. In Proceedings of the 5th Australian Information Security Management Conference, Perth, Australia, 5–6 December 2007; pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.L.; Wright, R.T.; Durcikova, A.; Karumbaiah, S. Improving phishing reporting using security gamification. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2022, 39, 793–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawindaran, N.; Jayal, A.; Prakash, E. Machine learning cybersecurity adoption in small and medium enterprises in developed countries. Computers 2021, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, A.A.; Quach, P.; Panwar, M.; Collier, Z.A.; Keisler, J.M.; Marchese, D.; Linkov, I. Multicriteria decision framework for cybersecurity risk assessment and management. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Hash, J. Building an information technology security awareness and training program. NIST Spec. Publ. 2003, 800, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haastrecht, M.; Yigit Ozkan, B.; Brinkhuis, M.; Spruit, M. Respite for SMEs: A systematic review of socio-technical cybersecurity metrics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Tikadar, S.; Dutta, P.K.; Sagayam, M. Lightweight Digital Trust Architectures in the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT); IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rawindaran, N.; Jayal, A.; Prakash, E.; Hewage, C. Perspective of small and medium enterprise (SME’s) and their relationship with government in overcoming cybersecurity challenges and barriers in Wales. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Raza, K. Blockchain technology in healthcare: Making digital healthcare reliable, more accurate, and revolutionary. In Translational Bioinformatics in Healthcare and Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, F.; Jung, H.; Welch, E. Technological vulnerability and knowledge of cyber-incidents: Threats to innovativeness in local governments? Public Manag. Rev. 2025, 27, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Dorado, M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, F.J.; Carmona-Murillo, J.; Cortés-Polo, D.; Calle-Cancho, J. Boosting holistic cybersecurity awareness with outsourced wide-scope CyberSOC: A generalization from a spanish public organization study. Information 2023, 14, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewoh, P.; Vartiainen, T. Vulnerability to cyberattacks and sociotechnical solutions for health care systems: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e46904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizich, M. The Cybersecurity Workforce of Tomorrow; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, T.; Jadav, N.K.; Tanwar, S.; Alabdulatif, A.; Garg, D.; Singh, A. A comprehensive survey on social engineering attacks, countermeasures, case study, and research challenges. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, I.A.; Hasan, H.R.; Jayaraman, R.; Salah, K.; Omar, M. Using blockchain technology to achieve sustainability in the hospitality industry by reducing food waste. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 197, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Sakamoto, H.; Miyazaki, T.; Kai, M. The Life Management Platform Achieves Data Protection and Safe Sharing. In Smart Sensors Networks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 339–359. [Google Scholar]

- Cailleux, L. The engagement of environmental organizations on land policies: A case study of Pro Natura, Switzerland. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.R.G.; de Azevedo Correia, A.I.; da Silva Braga, A.M. Motivations for and barriers to innovation in non-profit organizations: The case of nursing homes in Northern Portugal. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2024, 8, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.P.; Lashkari, A.H.; Parizadeh, M. Understanding cybersecurity management in healthcare. Prog. IS 2024. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-68034-2 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Johnson, D. Leadership Fundamentals for Cybersecurity in Public Policy and Administration: Lessons for the Global South; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, R.; Chutimaskul, W.; Roy, R.; Hautamäki, J.; Funilkul, S.; Pal, D. Developing a scale for measuring the information security awareness of stakeholders in higher education institutions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 13713–13777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, B.; Chaundy, B.G. Cybersecurity Leadership for Healthcare Organizations and Institutions of Higher Education; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, C.; Eulerich, M.; Holt, M. Characteristics of cybersecurity and IT involvement by the IA activity. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2025, 56, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.K.; Shiwakoti, N.; Stasinopoulos, P.; Chen, Y.; Warren, M. Cybersecurity framework for connected and automated vehicles: A modelling perspective. Transp. Policy 2025, 162, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoong, Y.; Rezania, D. Balancing talent and technology: Navigating cybersecurity and privacy in SMEs. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 15, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totty, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Janz, B. Information Security Research in the Information Systems Discipline: A Thematic Review and Future Research Directions. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2024, 55, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lariviere, B.; Schetgen, L.; Bogaert, M.; Van den Poel, D. Customer experiences and coping behaviors during crisis situations: The role of service adaptation and service transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 188, 115089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, K.; Hassan, M.A.; Alarifi, S.; Almagwashi, H. An intuitive approach to cybersecurity risk assessment for non-governmental organizations. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2025, 19, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallang, M.; Shariffuddin, M.D.K.; Mokhtar, M. Cyber security in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): What’s good or bad? J. Gov. Dev. (JGD) 2022, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermicioi, N.; Liu, X.M. An interdisciplinary study of cybersecurity investment in the nonprofit sector. Am. J. Manag. 2021, 21, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikos, L.F. Cybersecurity knowledge graphs. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2023, 65, 3511–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandayam, R. Cybersecurity strategies for non-profit organizations. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Multidiscip. Phys. Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermicioi, N.; Liu, M.X. Cybersecurity in nonprofits: Factors affecting security readiness during COVID-19. In Proceedings of the SAIS, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–14 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.W.; Huang, C.M.; Kuo, Y.C. Design of employee training in Taiwanese nonprofits. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Pearlson, K. Building a Model of Organizational Cybersecurity Culture. MIT CAMS—Organ. Cybersecur. Cult. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Larkey, S.N. Exploring the strategies cybersecurity specialist need to minimize security risks in non-profit organizations. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado Technical University, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, N. Implementing a Security Awareness Program. 2008. Available online: https://cs.lewisu.edu/mathcs/msis/projects/msis595_NancyKolb.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, O.; Hao, S.; He, J.; Lan, X.; Yang, J.; Ye, Y. Improved self-training-based distant label denoising method for cybersecurity entity extractions. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Liu, X. Level of Cybersecurity Readiness of Small and Medium Nonprofit Organizations (NPOs) During COVID-19. J. Strateg. Innov. Sustain. 2023, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mierzwa, S.; Jeong, B.G.; Yun, C. Proposal for the development and addition of a cybersecurity assessment section into technology involving global public health. Int. J. Cybersecur. Intell. Cybercrime 2020, 3, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, I.; Tsado, L.; Gibson, C. Towards Cyber Readiness Assessment in Rural Areas. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing Research, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–10 May 2023; pp. 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, A.; Insfran, E.; Abrahão, S. Usability evaluation methods for the web: A systematic mapping study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2011, 53, 789–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roshanaei, M.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Sinha, A.; Gokhale, V.; Raza, F.M.; Ramljak, D. Enhancing Cybersecurity Readiness in Non-Profit Organizations Through Collaborative Research and Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review. Computers 2025, 14, 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120539

Roshanaei M, Krishnamurthy P, Sinha A, Gokhale V, Raza FM, Ramljak D. Enhancing Cybersecurity Readiness in Non-Profit Organizations Through Collaborative Research and Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review. Computers. 2025; 14(12):539. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120539

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoshanaei, Maryam, Premkumar Krishnamurthy, Anivesh Sinha, Vikrant Gokhale, Faizan Muhammad Raza, and Dušan Ramljak. 2025. "Enhancing Cybersecurity Readiness in Non-Profit Organizations Through Collaborative Research and Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review" Computers 14, no. 12: 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120539

APA StyleRoshanaei, M., Krishnamurthy, P., Sinha, A., Gokhale, V., Raza, F. M., & Ramljak, D. (2025). Enhancing Cybersecurity Readiness in Non-Profit Organizations Through Collaborative Research and Innovation—A Systematic Literature Review. Computers, 14(12), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120539