Transformer Tokenization Strategies for Network Intrusion Detection: Addressing Class Imbalance Through Architecture Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present a controlled comparison of Transformer tokenization strategies for tabular IDS data, demonstrating that tokenization choice has a substantial impact on optimization behavior and detection performance.

- We analyze how architectural stabilization mechanisms, including Batch Normalization and constrained class weighting, influence training stability and minority-class detection under extreme class imbalance.

- We show that appropriate architectural design enables reliable learning in highly imbalanced IDS settings, improving minority-class behavior without reliance on synthetic data generation or large-scale data expansion.

- We derive practical design guidelines indicating that suitable tokenization and architecture choices can yield strong performance for imbalanced intrusion detection tasks using moderate-sized datasets.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transformers in IDS

2.2. Deep Learning for Intrusion Detection

2.3. Architecture Optimization vs. Data Collection

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

Data Sampling and Preparation

- Error Elimination and Gap Filling: The selected dataset undergoes preprocessing to eliminate errors, fill gaps, remove outliers, and discard irrelevant data types. We used linear interpolation to impute missing values.

- Scaling: The dataset was scaled using the StandardScaler class in scikit-learn, which normalizes features to zero mean and unit variance. This ensures that all features contribute equally to model training.

3.2. Tokenization Strategies

3.3. Mathematical Formulation

3.4. Optimization Stability: Addressing Class Imbalance

3.5. Experimental Setup

- Optimizer: Adam [24] (α = 0.001, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999).

- Loss Function: Categorical cross-entropy with class weights.

- Batch Size: 256.

- Training Epochs: Maximum 50 with early stopping (patience = 10, monitoring validation accuracy).

- Learning Rate Schedule: ReduceLROnPlateau (patience = 5, factor = 0.5, ).

- Random Seed: 42 (for reproducibility).

3.6. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results

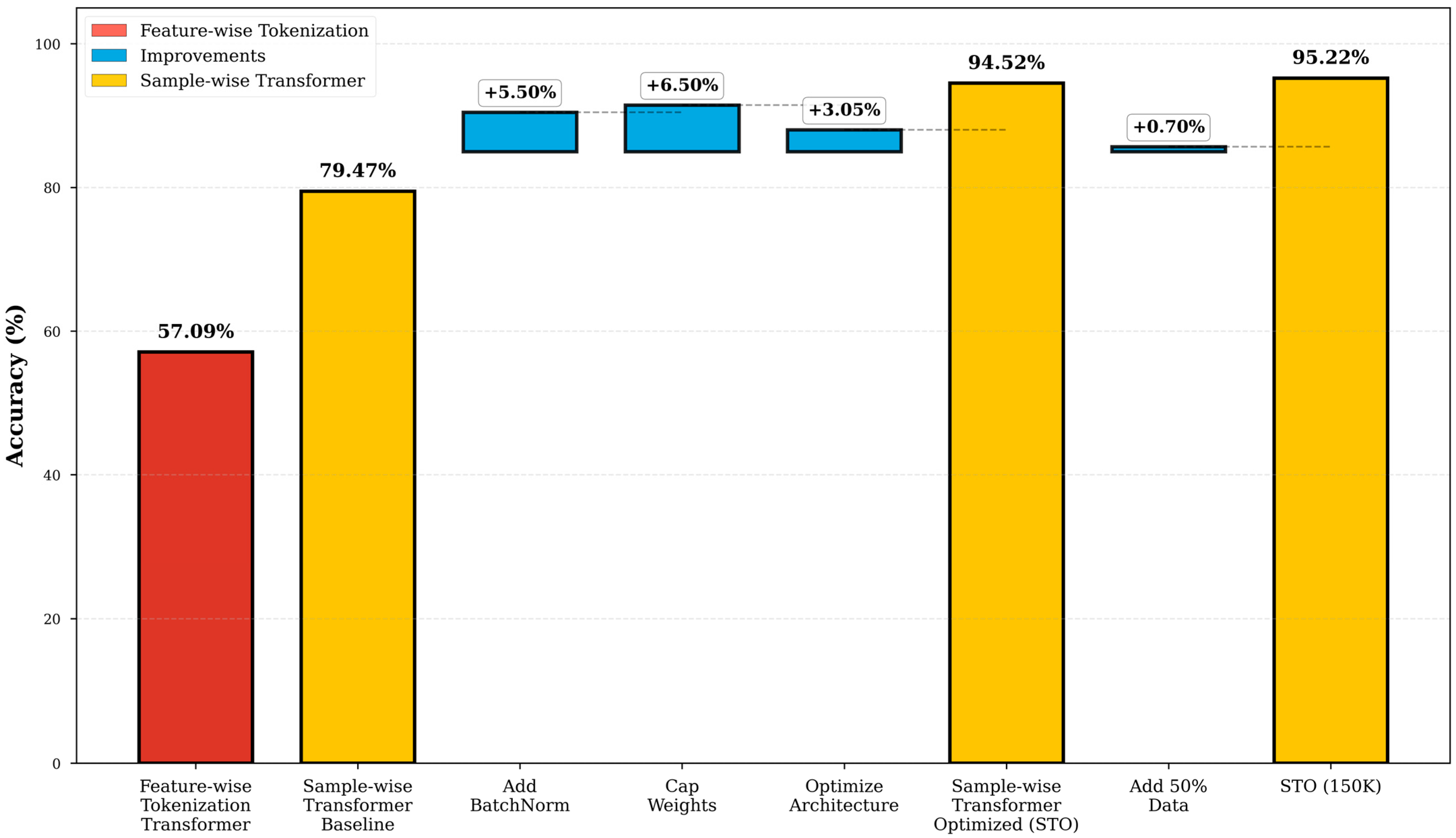

4.1. Overview of Improvement Process

- Tokenization emerges as the primary contributor of performance gains: the transition from per-feature to sample-wise tokenization accounts for 59.8% of the overall improvement, establishing it as the dominant factor. This finding indicates that representation design plays a fundamental role in determining model performance when applied to tabular IDS data.

- Architecture can be served as a secondary contributor to the overall performance gain, accounting for 38% of the total improvement. Specifically, Batch Normalization (+5.50%), capped class weighting (+6.50%), and architectural refinements (+3.05%) collectively contribute to this enhancement. These modifications primarily target optimization stability under conditions of severe class imbalance.

- The impact of additional data is marginal: expanding the dataset from 100 K to 150 K samples results in only a 0.70% performance improvement, indicating diminishing returns. This observation suggests that data volume alone may not constitute the primary driver of performance gains in this setting.

4.2. Optimization Stability and Overfitting Analysis

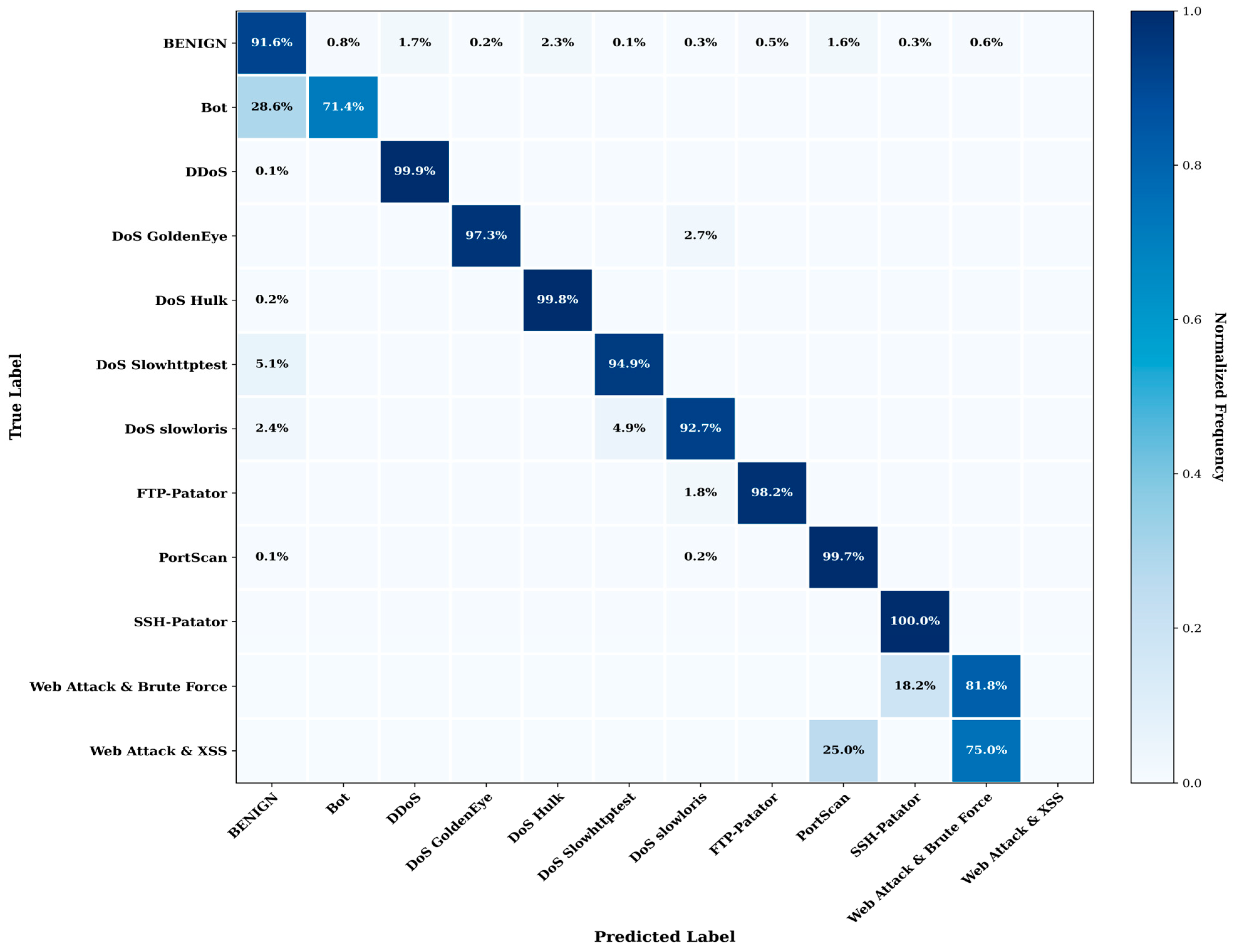

4.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

- A substantial portion of Bot traffic is misclassified as benign. This class accounts for only 14 training samples (0.01% of total data), which severely constrains the model’s ability to learn reliable decision boundaries. The observed confusion reflects inherent limitations of supervised learning under conditions of extreme data sparsity.

- In total, 25% of Web Attack & XSS samples are misclassified as PortScan, and the remaining 75% of Web Attack & XSS is misclassified as Web Attack & Brute Force, as well. This class is represented by only four training samples (0.002% of the dataset), providing an insufficient gradient signal for the model to reliably differentiate its behavior from similar reconnaissance-related patterns. Importantly, this limitation is not specific to the proposed model but rather reflects the intrinsic challenges of learning from extremely imbalanced data distributions.

4.4. Minority-Class Performance Analysis

- Capped class weights: Capped class weights () prevent gradient explosion and improve inter-class balance during training. This modification keeps the Hessian spectrum bounded and maintains a favorable optimization landscape.

- Batch Normalization: Reduces internal covariate shift and smooths feature distributions across classes. This technique produces a visibly flatter loss surface and reduces gradient variance, which is particularly beneficial for minority classes that exhibit narrow feature distributions.

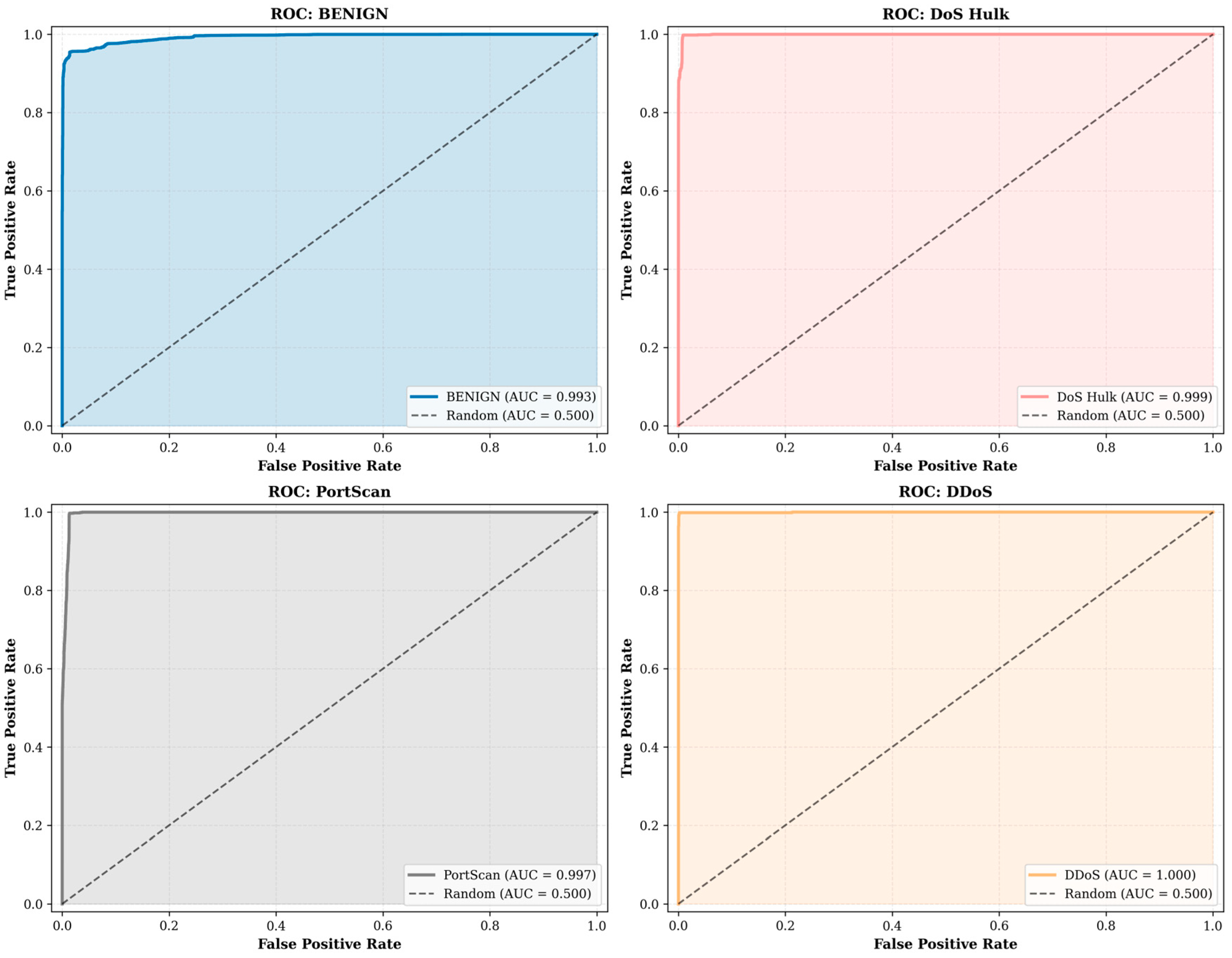

4.5. ROC Curve Analysis

- The per-class ROC curves for DDoS (AUC = 1.000), DoS Hulk (AUC = 0.999), PortScan (AUC = 0.996), and BENIGN traffic (AUC = 0.994) demonstrate near-perfect class separability. These results confirm that the optimized architecture effectively captures the distinctive patterns characteristic of high-frequency attack categories.

- The micro and macro average AUC values further verify the model’s discriminative capability, with a micro-average AUC of 0.998 and a macro-average AUC of 0.980. The small discrepancy between these metrics (0.0022) suggests that the proposed architectural stabilization techniques effectively mitigate the impact of class imbalance.

- Rare-class performance remains strong, as Web Attack XSS attains an AUC of 0.9811, which is notable given its extremely limited training representation (3 samples). This finding suggests that the incorporation of capped class weighting and batch normalization facilitates effective learning even under severe data scarcity.

4.6. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4.7. Hierarchical Impact Analysis

4.8. Ablation Study

- STB: 79.47% accuracy with sample-wise tokenization but no normalization or weight capping. This establishes the performance floor for per-sample approaches.

- Batch Normalization: 84.97% accuracy (+5.50 points). BatchNorm produces a flatter loss surface and reduces gradient variance, which is particularly beneficial for minority classes.

- Capped Class Weights: 91.47% accuracy (+6.50 points). Limiting the maximum weight to 10.0 prevents gradient explosion and maintains the stability of the optimization.

- Additional Transformer Block: 92.97% accuracy (+1.50 points). Increasing depth from 2 to 3 blocks provides additional representational capacity.

- Enhanced Feed-Forward: 93.97% accuracy (+1.00 point). Dense layers (256→128) outperform Conv1D layers for tabular data.

- Final Optimizations: 94.52% accuracy (+1.55 points). Including dropout regularization, increased attention heads (8 vs. 4), and deeper initial embedding (Dense 128).

4.9. Discussion

4.9.1. Impact of Tokenization Strategy

4.9.2. Effect of Architectural Refinements

4.9.3. Addressing Extreme Class Imbalance

4.9.4. Architecture Optimization Versus Data Collection

4.9.5. Discussion of State-of-the-Art Comparisons

4.9.6. Limitations and Constraints

4.9.7. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT 2019), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.M.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Survey on Deep Learning with Class Imbalance. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elreedy, D.; Atiya, A.F. A Comprehensive Analysis of Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) for Handling Class Imbalance. Inf. Sci. 2019, 505, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari, S.; Mithal, V.; Polatkan, G.; Ramanath, R. An Attentive Survey of Attention Models. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2021, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Khetan, A.; Cvitkovic, M.; Karnin, Z. TabTransformer: Tabular Data Modeling Using Contextual Embeddings. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.06678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arik, S.Ö.; Pfister, T. TabNet: Attentive Interpretable Tabular Learning. In Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 6679–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somepalli, G.; Goldblum, M.; Schwarzschild, A.; Bruss, C.B.; Goldstein, T. SAINT: Improved Neural Networks for Tabular Data via Row Attention and Contrastive Pre-Training. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.01342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorishniy, Y.; Rubachev, I.; Khrulkov, V.; Babenko, A. Revisiting Deep Learning Models for Tabular Data. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021), Virtual Event, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 18932–18943. [Google Scholar]

- Vinayakumar, R.; Alazab, M.; Soman, K.P.; Poornachandran, P.; Al-Nemrat, A.; Venkatraman, S. Deep Learning Approach for Intelligent Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 41525–41550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, A.; Wu, H. Network Intrusion Detection Combined Hybrid Sampling with Deep Hierarchical Network. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 32464–32476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shen, J.; Du, X.; Zhang, F. An Intrusion Detection System Using a Deep Neural Network with Gated Recurrent Units. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 48697–48707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Sun, Z. RTIDS: A Robust Transformer-Based Approach for Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64375–64387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueriani, A.; Kheddar, H.; Mazari, A.C. Adaptive Cyber-Attack Detection in IIoT Using Attention-Based LSTM-CNN Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14806. [Google Scholar]

- Hestness, J.; Narang, S.; Ardalani, N.; Diamos, G.; Jun, H.; Kianinejad, H.; Patwary, M.M.A.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Deep Learning Scaling is Predictable, Empirically. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.00409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Shrivastava, A.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A. Revisiting Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data in Deep Learning Era. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV 2017), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Hutter, F. Neural Architecture Search: A Survey. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 1997–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward Generating a New Intrusion Detection Dataset and Intrusion Traffic Characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2018), Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper-Gil, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of Encrypted and VPN Traffic Using Time-Related Features. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2016), Rome, Italy, 19–21 February 2016; pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2015), Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2015), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam, V.; Razavi-Far, R.; Hallaji, E. Addressing Class Imbalance in Intrusion Detection: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Machine Learning Approaches. Electronics 2025, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okey, O.D.; Maidin, S.S.; Adasme, P.; Rosa, R.L.; Saadi, M.; Carrillo Melgarejo, D.; Zegarra Rodríguez, D. BoostedEnML: Efficient Technique for Detecting Cyberattacks in IoT Systems Using Boosted Ensemble Machine Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 7409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.; Park, M.; Lee, D.H. AI-IDS: Application of Deep Learning to Real-Time Web Intrusion Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 70245–70261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, M.A.; Pak, W. Tier-Based Optimization for Synthesized Network Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 108530–108544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.M.K.; Yow, K.-C.; Zhu, Z.; Aravamuthan, S. Network Intrusion Detection via Flow-to-Image Conversion and Vision Transformer Classification. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 97780–97793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra Rodriguez, D.; Daniel Okey, O.; Maidin, S.S.; Umoren Udo, E.; Kleinschmidt, J.H. Attentive transformer deep learning algorithm for intrusion detection on IoT systems using automatic Xplainable feature selection. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Z.; Tiberti, W.; Marotta, A.; Cassioli, D. Empowering Network Security: BERT Transformer Learning Approach and MLP for Intrusion Detection in Imbalanced Network Traffic. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 137618–137633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Feature-Wise Tokenization Transformer (FTT) | Sample-Wise Transformer-Baseline (STB) | Sample-Wise Transformer-Optimized (STO) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tokenization Configuration | |||

| Token count sample-wise Token dimension Positional encoding Initial embedding | 78 (78, 1) 32 Learnable Linear(1, 32) | 1 (1, 78) None Identity | 1 (1, 78) None Dense(128) + ReLU |

| Transformer Architecture | |||

| Number of blocks Attention heads Attention matrix size Feed-forward type Feed-forward dimensions Batch Normalization Dropout rate | 2 4 78 × 78 (6084) Dense 128 64 No 0.1 | 2 4 1 × 1 (1) Conv1D 128 64 No 0.1 | 3 8 1 × 1 (1) Dense 256 128 Yes (after embed + head) 0.3 |

| Training Configuration | |||

| Class weighting Max class weight Learning rate (initial) LR schedule Batch size Early stopping patience | Balanced 150.0+ 0.001 ReduceLROnPlateau 256 10 | Balanced (uncapped) 150.0+ 0.001 ReduceLROnPlateau 256 10 | Balanced (max = 10.0) 10.0 (capped) 0.001 ReduceLROnPlateau 256 10 |

| Model | Year | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest [26] | 2022 | 99.49 | 99.48 | 99.47 | 99.47 | 9 (aggregated) |

| Deep Learning Approaches | ||||||

| DNN [12] | 2019 | 96.0 | 96.9 | 96.0 | 96.2 | 8 (aggregated) |

| CNN-LSTM [27] | 2020 | 93.0 | 96.47 | 76.83 | 81.36 | Binary |

| CNN [28] | 2022 | 98.79 | 98.80 | 98.77 | 98.77 | 9 (aggregated) |

| Transformer-Based and Hybrid Architectures | ||||||

| Vision Transformer [29] | 2022 | 96.4 | 8 (aggregated) | |||

| TabNet-IDS [30] | 2023 | >98% (reported, 9-class setting) | 9 (aggregated) | |||

| BERT-MLP [31] | 2024 | 99.39 | 99.39 | 99.39 | 99.99 | 7 (aggregated) |

| Our Transformer Approaches | ||||||

| Feature-wise Tokenization Transformer | 57.09 | 52.34 | 48.92 | 50.56 | 11 | |

| Sample-wise Transformer-Baseline | 79.47 | 76.82 | 75.19 | 75.99 | 11 | |

| Sample-wise Transformer-Optimized | 94.52 | 93.87 | 93.21 | 93.54 | 11 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Aksholak, G.; Bedelbayev, A.; Magazov, R.; Kaplan, K. Transformer Tokenization Strategies for Network Intrusion Detection: Addressing Class Imbalance Through Architecture Optimization. Computers 2026, 15, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020075

Aksholak G, Bedelbayev A, Magazov R, Kaplan K. Transformer Tokenization Strategies for Network Intrusion Detection: Addressing Class Imbalance Through Architecture Optimization. Computers. 2026; 15(2):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020075

Chicago/Turabian StyleAksholak, Gulnur, Agyn Bedelbayev, Raiymbek Magazov, and Kaplan Kaplan. 2026. "Transformer Tokenization Strategies for Network Intrusion Detection: Addressing Class Imbalance Through Architecture Optimization" Computers 15, no. 2: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020075

APA StyleAksholak, G., Bedelbayev, A., Magazov, R., & Kaplan, K. (2026). Transformer Tokenization Strategies for Network Intrusion Detection: Addressing Class Imbalance Through Architecture Optimization. Computers, 15(2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15020075