1. Introduction

Wildfires have profound impacts on ecosystems, the environment, and human communities; they lead to the destruction of forests and natural resources and pose considerable public health risks due to elevated air pollution, particularly from fine particulate matter such as PM2.5. The severity of wildfire incidents is often amplified in regions that are critical for forest conservation and within community forests, both of which are essential for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem stability [

1]. Ubon Ratchathani Province is a pertinent example, having experienced recurrent wildfires in recent years. The consequences extend beyond environmental degradation to include substantial social and economic repercussions for local populations. As such, enhancing the effectiveness of wildfire detection and early warning systems, particularly in remote areas, is of paramount importance.

Recent advancements in the Internet of Things (IoT) and long-range (LoRa) technology present new opportunities for the development of wildfire early warning systems. The IoT facilitates the deployment of interconnected sensors that are capable of monitoring environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, and smoke levels. LoRa technology, in turn, enables reliable long-distance data transmission without dependence on conventional internet connectivity, a crucial advantage in remote or hard-to-reach locations where the communication infrastructure is limited [

2].

Sok Chan Forest, located in Phon Mueang Subdistrict, Lao Suea Kok District, Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand, exemplifies the challenges associated with wildfire management in remote areas. According to records from 2020 to 2022, the number of wildfire suppression incidents increased from 10 in 2020 to 12 in 2021 and further to 15 in 2022, indicating a rising trend in wildfire occurrence and severity. These incidents have resulted in significant damage not only to the environment and local ecosystems but also to the well-being and livelihoods of the surrounding communities [

3]. The region’s challenging terrain and limited communication infrastructure hinder timely wildfire detection, with traditional methods, such as human surveillance or systems that are reliant on internet connectivity, proving insufficient and often resulting in delayed responses and increased damage.

To address these limitations, we designed and developed a wildfire early warning system that leverages LoRa technology. The system architecture involves the installation of sensor nodes throughout the forest area to monitor the air quality and provide geolocated data using GPS. These sensor nodes communicate via a peer-to-peer LoRa network, relaying information to a central node, which then transmits the aggregated data to a remote server over the internet. Additionally, a dedicated smartphone application is developed to display real-time air quality metrics and sensor locations and issue automatic alerts when environmental conditions indicating wildfire risk are detected. Through this approach, we aim to enable rapid responses by authorities and prevent the escalation of wildfire incidents. Following system development, field testing was conducted in Sok Chan Forest area to assess both the system effectiveness and user satisfaction.

Although LoRa-enabled IoT sensing has been widely studied for wildfire monitoring, many prototypes either rely on star or LoRaWAN topologies with a dedicated gateway or provide limited evidence on end-to-end alarm timeliness and operational usability in real deployments. In parallel, vision-based deep learning methods (e.g., YOLO variants) and multimodal fusion have become increasingly popular for smoke/fire recognition; however, camera-based approaches can be constrained by power budgets, line of sight, illumination, and the need for broadband backhaul in remote forests. Consequently, a practical gap remains for low-cost, long-range, field-deployable systems that combine multi-parameter sensing with peer-to-peer LoRa relaying and that are evaluated not only by radio performance but also by alert accuracy and user-centered effectiveness.

This paper addresses the above gap with the following contributions: (1) a solar-powered sensor node integrating temperature, humidity, smoke, and PM2.5 sensing with GPS geotagging; (2) a peer-to-peer (multi-hop capable) LoRa network using the SX1262 transceiver to extend coverage without fixed infrastructure; (3) a full-stack early warning workflow, including a web backend and a firefighter-oriented mobile application for real-time visualization and alerts; and (4) a comprehensive evaluation covering long-range communication (RSSI, SNR, and packet delivery), end-to-end detection latency, controlled alarm-classification performance (precision, recall, and F1), and a user study with firefighters and software experts.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 1 presents the introduction.

Section 2 reviews the related work concerning the application of IoT and LoRa technologies in forest fire detection systems.

Section 3 details the proposed methodology.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results and provides an analysis of the system’s performance. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this study and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Recent advances in Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have enabled the development of automated wildfire monitoring and early warning systems through the deployment of distributed environmental sensors. Among the available wireless communication technologies, LoRa (long range) and LoRaWAN have attracted considerable attention due to their capability to support long-range, low-power data transmission, which is particularly suitable for remote and infrastructure-limited forest environments [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Recent practical deployments and industry-oriented studies further emphasize that low-power wide-area network (LPWAN) technologies, such as LoRaWAN, are well suited for large-scale wildfire monitoring due to their always-on connectivity, multi-kilometer coverage, and long battery lifetime, enabling sensor nodes to operate for several years with minimal maintenance [

8]. These characteristics are critical for early wildfire detection in forests where conventional communication infrastructure is unavailable or unreliable.

A large body of prior work has explored LoRa-based wildfire detection systems that monitor environmental parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, smoke or gas concentration, wind conditions, and particulate matter. Vega-Rodríguez et al. [

4] and Sendra et al. [

6] demonstrated that LoRa-enabled sensor networks can reliably provide kilometer-scale coverage while maintaining low energy consumption, allowing sensor nodes to operate autonomously for extended periods. Similarly, Găițan and Hojbotă [

5] and Saida et al. [

7] proposed LoRa or LoRaWAN-based architectures integrating multiple environmental sensors and cloud platforms to support real-time monitoring and alert dissemination.

Several studies further enhanced situational awareness by incorporating GPS modules and web- or mobile-based visualization interfaces, enabling authorities and local communities to access real-time sensor data and node locations [

7,

8,

9,

10]. For example, Sulaiman et al. [

11] developed a LoRa-based forest fire detection system integrating temperature, humidity, and smoke sensors with a web-based real-time monitoring platform, demonstrating reliable communication over distances of up to 1 km without reliance on internet connectivity at the sensing layer. Their experimental results confirm that LoRa-based environmental sensing can provide timely and reliable fire status information in remote forest areas. Experimental evaluations in forest and rural environments consistently report acceptable received signal strength indicator (RSSI), signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and packet delivery ratios over distances ranging from hundreds of meters to several kilometers, depending on terrain, antenna configuration, and spreading factor settings [

10,

12]. These results confirm the suitability of LoRa technology for low-cost, wide-area wildfire monitoring.

Despite these advantages, LoRa-based wildfire detection systems also present inherent limitations. Due to the low data rate of LoRa, most existing systems are restricted to scalar environmental sensing and are not well suited for high-bandwidth modalities such as continuous image or video transmission [

6,

9]. Communication performance may degrade in dense vegetation, uneven terrain, or adverse weather conditions, requiring careful node placement, antenna optimization, or the use of multi-hop relaying strategies to maintain link reliability [

10,

12]. In addition, many prior studies rely on star or LoRaWAN topologies with fixed gateways, which can introduce infrastructure dependency and limit deployment flexibility in highly remote or inaccessible forest areas [

5,

6,

12].

In parallel, vision-based and deep learning approaches using ground cameras or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been increasingly investigated for wildfire and smoke detection [

13,

14,

15]. These methods can achieve high detection accuracy and provide early visual recognition of smoke plumes; however, they typically require higher power budgets, stable broadband backhaul connectivity, and favorable lighting and visibility conditions. Consequently, their large-scale and long-term deployment in remote forests remains challenging when compared with low-power LoRa-based sensing solutions.

Overall, existing studies highlight a practical gap for wildfire early warning systems that combine multi-parameter environmental sensing with infrastructure-independent, flexible communication architectures. In particular, there remains a need for systems that leverage peer-to-peer or multi-hop LoRa communication to extend coverage without fixed gateways, while being evaluated not only regarding the radio performance but also alarm accuracy, detection latency, and operational usability in real deployments. The present study addresses this gap by proposing and validating a LoRa-based, multi-hop wildfire early warning system with comprehensive field experiments and user-centered evaluation.

3. Materials and Methods

The figure below illustrates the architecture we used to develop a wildfire early warning system using LoRa technology.

Figure 1 presents the architecture of the proposed wildfire alert system comprises two main components: the central node and the sensor nodes. The sensor nodes are strategically deployed throughout the monitored area to detect wildfire indicators. Each sensor node collects environmental data, including the temperature, relative humidity, smoke, and PM2.5 concentration, and transmits these readings iteratively via a peer-to-peer LoRa communication network to the neighboring sensor nodes until they reach the central node. Upon receiving the aggregated data, the central node forwards the information to a remote server over the internet. Sensor data are then visualized in real time through both a smartphone application and a web interface. Furthermore, the system is equipped to automatically issue alerts through the dedicated smartphone application whenever any sensor measurements exceed predefined thresholds. This early warning capability supports timely intervention by enabling personnel to implement damage mitigation and wildfire prevention strategies.

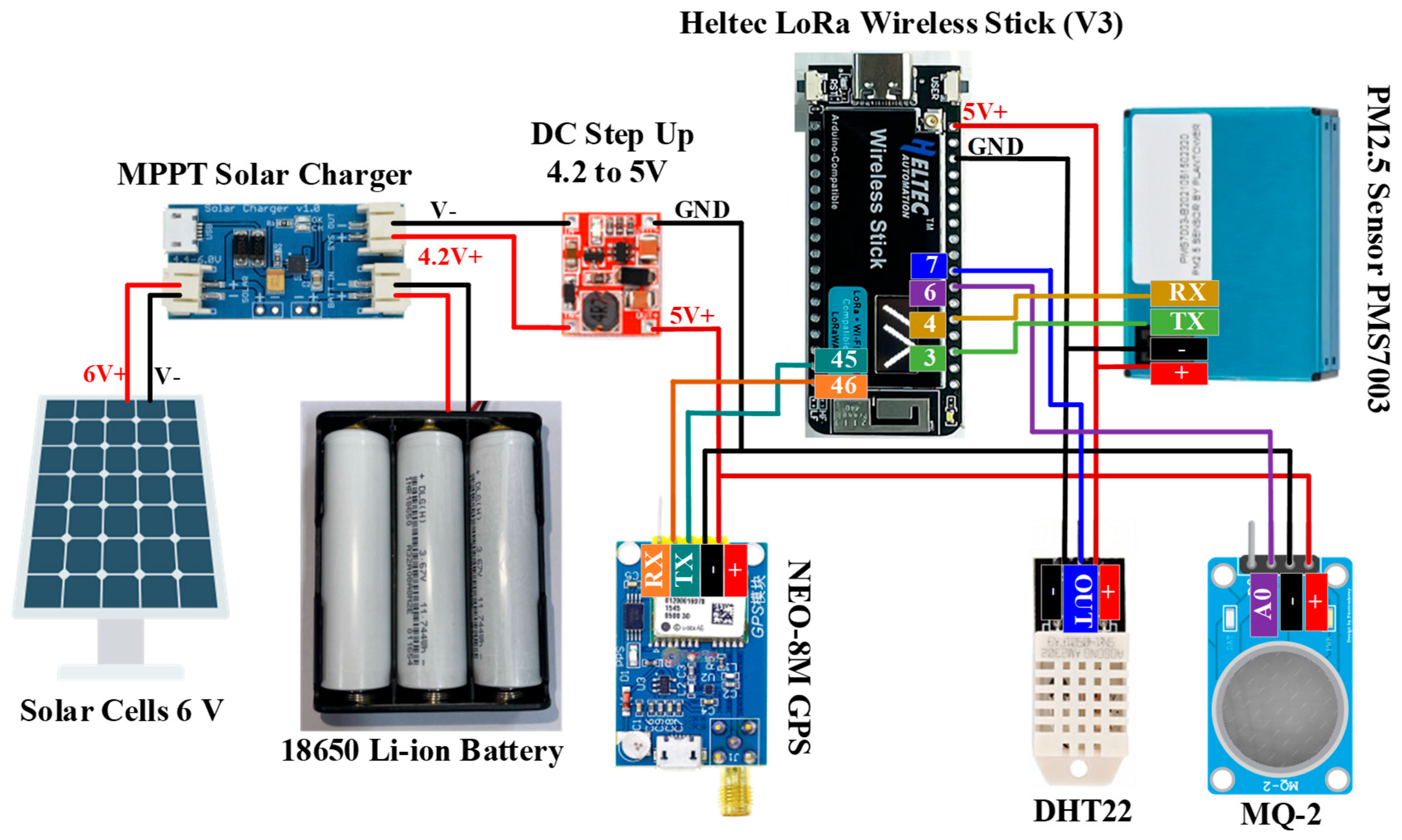

3.1. System Circuit Design

Microcontroller and operating modes: both the sensor and central nodes employ the Heltec Wireless Stick V3 (Heltec Automation, Chengdu, China) development board, which integrates an ESP32-S3 MCU (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China) and an SX1262 LoRa transceiver (Semtech Corporation, Camarillo, CA, USA). The MCU coordinates the sensing cycle, packet formation, LoRa transmission/reception, and local timestamping. For the central node, it also manages Wi-Fi backhaul to the remote server. To support long-term solar-powered operation, the firmware can duty-cycle sensing and communication and use low-power sleep modes between measurement intervals, thereby reducing average current consumption. The SX1262 is controlled by the ESP32-S3 via an SPI bus and several control/status pins.

Table 1 summarizes the logical interface signals used by the firmware (pin labels follow the SX126x convention) [

16].

Figure 2 presents the circuit diagram of the sensor node, illustrating the integration of the various components. These include an ESP32 LoRa microcontroller board (Heltec Wireless Stick V3), a DHT22 sensor for air temperature and humidity measurements (Aosong Electronics, Guangzhou, China), an MQ-2 sensor (Winsen Electronics Technology, Zhengzhou, China) for smoke detection, a PMS7003 sensor (Plantower, Nanchang, China) for PM2.5 concentration measurements, and a NEO-8M GPS module (u-blox AG, Thalwil, Switzerland) to record the geographic location of each sensor node. A solar panel is employed to harvest energy from sunlight, which is stored in an 18650 Li-ion battery. An MPPT solar charger regulates the transfer of energy from the solar panel to the battery and supplies power to the microcontroller. When predefined conditions are met, the system transmits the collected sensor data to adjacent sensor nodes via the LoRa network.

Figure 3 illustrates the circuit of the central node device, which is responsible for receiving data from the sensor nodes and transmitting it to a remote server via the internet through a Wi-Fi router for database storage. Furthermore, the system includes both a smartphone application and a website, enabling users to access and visualize wildfire detection data from each node in real time for all monitored locations.

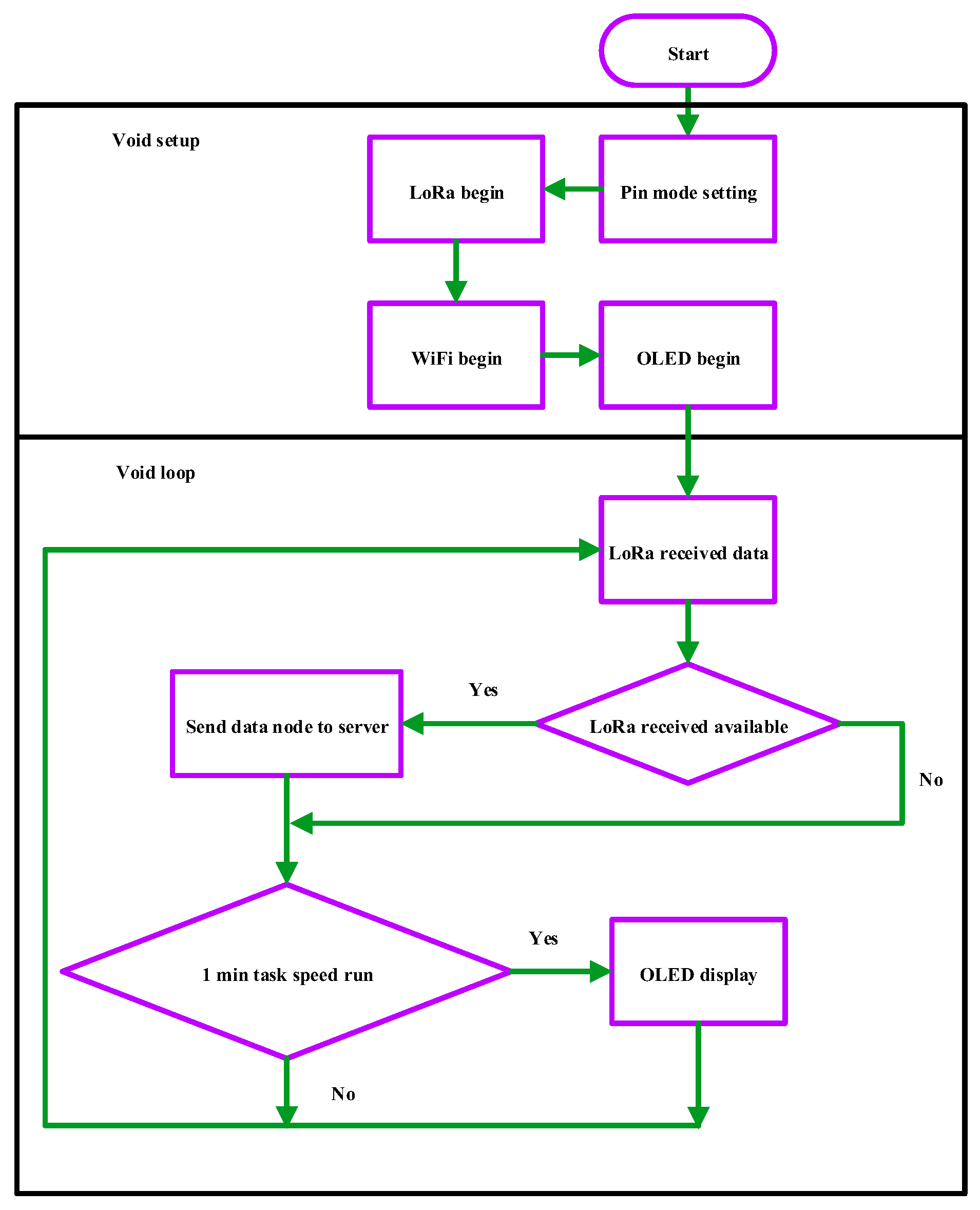

3.2. Flowchart of System Design

Programs written in C for the Arduino platform follow a basic structure comprising two mandatory functions: setup() for initial configurations and loop() for continuous operation.

Figure 4 depicts the operational workflow of the sensor node device. During the initialization phase, the ESP32 LoRa board activates its GPIOs to establish connections with the LoRa transceiver and the various sensors, including the DHT22 (temperature and humidity), MQ-2 (smoke detection), PMS7003 (PM2.5 measurement), and NEO-8M (GPS) modules. Within the main loop, the node continuously monitors for incoming LoRa transmissions from neighboring sensor nodes. Upon detection, it verifies whether the received data originated from itself; if not, the data are forwarded to the next adjacent node. Every five minutes, as specified by the system cycle, the device collects new measurements from its connected sensors: temperature and humidity measurements from the DHT22, smoke levels from the MQ-2, PM2.5 concentrations from the PMS7003, and positional coordinates from the NEO-8M module. Subsequently, the node packages all sensor data into a comma-separated string containing the node identifier, smoke value, temperature, humidity, PM2.5 reading, latitude, and longitude and transmits this package to adjacent nodes via the LoRa network.

Figure 5 presents the workflow of the central node program. The process begins with an initialization phase, during which the system establishes connections to the LoRa network, Wi-Fi network, and onboard OLED display module. During the main loop, the central node continuously monitors for incoming LoRa transmissions from nearby sensor nodes. Upon receiving data, the system transmits the information to the server for database storage. Additionally, at one-minute intervals, the most recently received sensor data are displayed on the OLED module.

Figure 6 illustrates the workflow of the web backend, which was developed in PHP to receive and process data from the central node. Upon receiving POST data, the system verifies the presence of input; if no data are received, it returns an error message. When data are detected, the backend decodes the JSON payload to extract relevant parameters, including the sensor node ID, air temperature, humidity, smoke value, PM2.5 concentration, and the node’s geographic coordinates. The system then classifies the wildfire risk status into three alert categories according to the following criteria [

17,

18,

19]:

Fire: temperature > 45 °C, smoke value > 1984, or PM2.5 > 150 µg/m3.

Surveillance: 35 °C < temperature ≤ 45 °C, 1190 < smoke value ≤ 1984, or 50 µg/m3 < PM2.5 ≤ 150 µg/m3.

Normal: temperature ≤ 35 °C and humidity ≥ 50%, smoke value ≤ 1190, and PM2.5 ≤ 50 µg/m3.

Subsequently, the processed data, along with the status classification, are saved and logged in the MySQL database. Finally, the system responds with a success message to confirm completion of the procedure.

3.3. System Performance Analysis

The effectiveness of our LoRa-based wildfire early warning system was evaluated by a panel comprising five software development experts and fifteen firefighters. Descriptive statistical methods (specifically, the calculation of the mean and standard deviation (S.D.)) were employed to analyze participant responses, which were collected via a Likert scale rating [

20]. The interpretation of the mean scores was categorized as follows: highest, 4.50–5.00; high, 3.50–4.49; moderate, 2.50–3.49; low, 1.50–2.49; and lowest, 1.00–1.49. The participants consisted of operational end users and technical experts, as summarized in

Appendix A, ensuring that the evaluation reflects both practical firefighting requirements and system-level usability.

Inferential data analysis was employed to evaluate whether implementing the LoRa-based wildfire early warning system led to a statistically significant improvement in operational efficiency. A paired-samples

t-test was conducted to compare the efficiency scores obtained from the panel of twenty participants (five domain experts and fifteen firefighters) before and after the system’s deployment through a Likert-scale questionnaire. The pre-implementation scores reflected baseline performance using traditional wildfire detection methods, while the post-implementation scores measured perceived efficiency and responsiveness with the new system in operation. The

t-test was used to examine the mean difference between these two conditions under the assumption of normally distributed difference scores [

21].

3.4. Experimental Performance of the Data Processing and Recording System

In this experiment, the key environmental variables of air temperature, relative humidity, smoke concentration, and PM2.5 levels were continuously monitored at five sensor nodes located within Sok Chan Forest, Lao Suea Kok District, Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand. Measurements were obtained at three-hour intervals over a one-week period, yielding a total of 58 samples per sensor node. The collected dataset was systematically processed and analyzed to facilitate the detection and early warning of potential wildfire occurrences.

3.5. Remote Communication Performance Analysis

Long-range communication performance was analyzed using both the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

The RSSI represents the power level of the received signal, expressed in dBm; higher (less negative) values indicate stronger signals, with values close to −30 dBm reflecting very strong signals and those near −120 dBm indicating weak signals [

22]. Theoretically, the RSSI can be calculated as follows:

where RSSI denotes the received signal strength indicator, expressed in dBm, and P

rw represents the received power at the receiver, also expressed in dBm.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), measured in decibels (dB), quantifies the ratio between the power of the received signal and that of the background noise. Higher SNR values correspond to improved signal quality, as the signal is further above the noise floor [

23]. The SNR can be calculated by summing the received signal power and the noise floor, as shown in Equation (2).

In a standard LoRa module, specific commands or functions are provided to directly read the RSSI and SNR values, which are stored in dedicated registers that retain these measured parameters.

In this experimental design, six cabinet nodes were deployed to evaluate the performance of single-hop, long-range wireless communication. One central node acted as the receiver, while the remaining five operated as sensor transmitters. The sensor nodes were positioned at distances of 300, 600, 900, 1200, and 1500 m from the central receiver node to systematically assess transmission performance over varying ranges. At multiple locations across Sok Chan Forest, each sensor node transmitted 10 data packets containing measurement parameters at five-minute intervals. All sensor nodes were mounted on trees at an approximate height of 5 m above ground level, whereas the central receiving node was placed outside the forest. The collected data were subsequently analyzed to evaluate the average signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), received signal strength indicator (RSSI), and packet reception integrity for each transmission distance.

The field experiments were conducted under typical dry-season conditions. Nevertheless, real deployments may face harsh weather such as cloudy days, rain, and fog, which can introduce additional attenuation, moisture-related antenna detuning, and greater channel variability in forested environments. To maintain operational robustness, the system is designed with link margin (RSSI above sensitivity and positive SNR in the tested ranges) and supports relay-based forwarding. Future work will systematically repeat the range and reliability tests under rainy and foggy conditions to quantify weather-dependent degradation and refine deployment guidelines (e.g., spacing and antenna height).

3.6. Detection Latency Analysis

A detection latency experiment was used to quantify the delay between the occurrence of an event at a sensor node and the reception of the corresponding message at the central node. This metric characterizes system responsiveness and is essential for evaluating the feasibility of the proposed wildfire early warning network. Two communication configurations were examined: single-hop and two-hop transmissions.

The single-hop test assessed the end-to-end latency of direct communication between a sensor node and the central station. The procedure was as follows:

- A.

The sensor node simulated a trigger event.

- B.

Upon activation, the node immediately transmitted an alert packet to the central node.

- C.

Transmission and reception times (Ttx) and (Trx) were recorded.

- D.

Detection latency was computed using

- E.

Each distance (300 and 900 m) was tested 10 times, and the mean latency and standard deviation were calculated.

All transmissions were logged locally and later analyzed to yield latency values (in milliseconds) representing the average single-hop response time of the network.

The two-hop configuration evaluated the impact of message relaying on overall system latency. In this setup, the sensor node’s alert was forwarded through an intermediate relay before reaching the central node. Two total transmission distances were tested 600 and 1200 m with the nodes positioned equidistantly. The procedure was as follows:

- A.

The sensor node generated a trigger event identical to the single-hop test.

- B.

The relay node recorded message reception (Trelay−rx), retransmitted it immediately, and logged the retransmission time (Trelay−sent).

- C.

The central node recorded the final reception timestamp (Trx).

- D.

The total latency was determined using

- E.

Each distance configuration was tested 10 times, and the mean and standard deviation were computed.

This methodology enabled the quantification of both per-hop transmission delay and the additional processing latency introduced by the relay node.

3.7. Alarm Accuracy Evaluation

To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy of the wildfire alarm function, an experiment was conducted to compare the system’s automatic alert classifications (Normal, Surveillance, Fire) against ground-truth conditions observed in the field, focusing on the FireLo backend classification rules described in

Section 3.2.

The alarm accuracy experiment was conducted under controlled conditions to evaluate system performance for each alarm category. Controlled smoke and heat sources were used to recreate representative environmental conditions. A single sensor node was deployed in Sok Chan Forest at a height of approximately 5 m, using the same hardware and LoRa configuration as in previous experiments.

Normal condition: The sensor was operated under ambient forest conditions without artificial smoke or heat sources. At least 20 independent measurement cycles (at 1 min intervals) were recorded.

Surveillance condition: A small, smoldering biomass source (damp leaves and branches) was ignited 3–5 m from the sensor. The source was regulated to produce elevated smoke and PM2.5 levels while maintaining temperatures below the Fire threshold. At least 20 measurement cycles were collected.

Fire condition: A controlled open flame using dry biomass was established at a similar distance and monitored by firefighters to ensure safety. The setup was adjusted so that at least one key parameter (temperature, smoke value, or PM2.5) exceeded the Fire threshold. A further 20 measurement cycles were recorded.

For each measurement cycle, the following data were logged:

Raw sensor readings: Temperature, humidity, smoke (ADC units), and PM2.5 (µg/m3).

System-generated status: Normal, Surveillance, or Fire.

Ground-truth label: Normal, Surveillance, or Fire, assigned by expert observers based on the experimental setup and visual inspection of fire and smoke conditions.

A confusion matrix was constructed by comparing the system-generated status with the ground-truth labels across all trials. From this matrix, the overall accuracy and class-wise precision, recall, and F1-score for the Normal, Surveillance, and Fire classes were computed.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of Developing a Wildfire Early Warning System Using LoRa Technology

Figure 7 depicts the prototype of an early warning device cabinet for wildfires that employs LoRa technology for long-distance data transmission. The system consists of a central node cabinet and two sensor node devices, all primarily powered by a 6 V 10 W solar panel that also charges three 4.2 V 18650 lithium batteries to ensure uninterrupted operation. The Heltec LoRa Wireless Stick (V3) module, featuring an SX1262 LoRa chip, enables reliable wireless communication within the 863–928 MHz frequency band for both data transmission and reception.

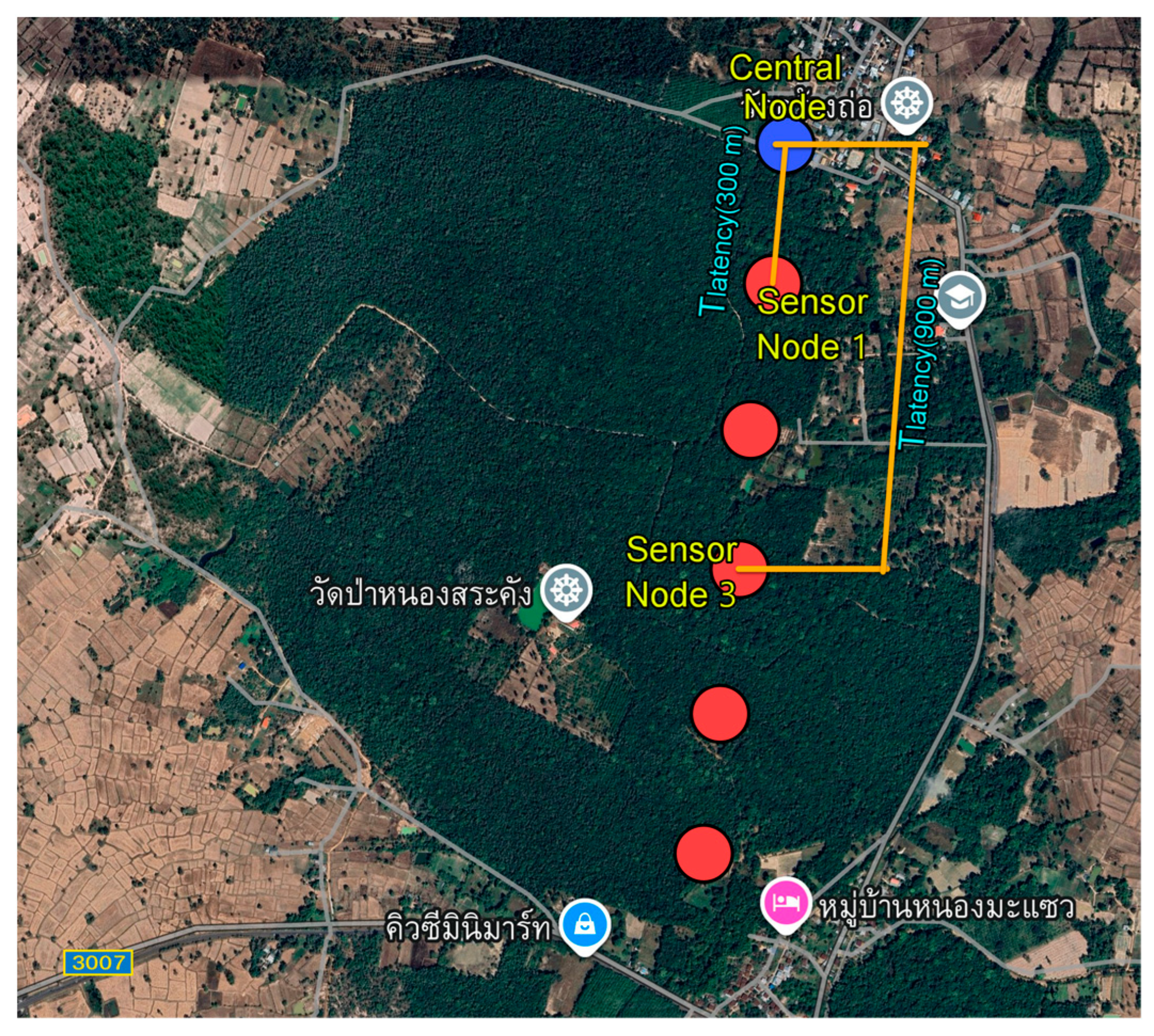

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the early warning system was deployed in Sok Chan Forest, located in Phon Mueang Subdistrict, Lao Suea Kok District, Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand. Two sensor nodes were installed on trees at a height of approximately 5 m above ground level, while the central node was positioned outside the forest to facilitate signal reception. The central node was connected to a Wi-Fi router utilizing a 4G SIM card for internet connectivity. The operational efficiency of the system was subsequently evaluated under these deployment conditions.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 showcase the user interfaces of the newly developed FireLo application and its associated website, both designed to facilitate real-time forest fire monitoring and alerts. The FireLo application, accessible to firefighters at

http://www.fa.ponglert.cs.ubru.ac.th/loadapp.php (accessed on 15 May 2025), provides a comprehensive list of sensor nodes, each offering detailed real-time data for temperature, humidity, smoke concentration, and PM2.5 levels. The application also features notification alerts and audible alarms that activate when sensor readings reach thresholds indicating Surveillance or Fire status. Complementing this, the website interface that is available to community members at

http://www.fa.ponglert.cs.ubru.ac.th/gmap.php (accessed on 15 May 2025) displays an interactive map showing the geographical locations of individual sensor nodes. Each marker on the map displays the node identifier and current environmental readings, with the sensor status being visually represented by color-coded markers: green for Normal conditions, orange for surveillance, and red for Fire detection.

4.2. Performance Test Results for the Processing and Recording of the Early Warning System for Wildfires

Air temperature, relative humidity, smoke concentration, and PM2.5 levels were monitored at a single observation site located in Sok Chan Forest, Lao Suea Kok District, Ubon Ratchathani Province, Thailand. Measurements were recorded at three-hour intervals, yielding a total of 58 samples per parameter, over the one-week period from 29 April to 6 May 2025. The collected data were systematically archived for subsequent analysis to detect potential forest fire occurrences. The measurement results for each parameter are presented below.

The time-series data presented in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, spanning one week of continuous monitoring in Sok Chan Forest, provide a comprehensive depiction of key environmental variables relevant to wildfire risk detection. The statistical analysis reveals that the mean air temperature during the observation period was 30.71 °C (SD = 4.03), while relative humidity averaged 67.90% (SD = 15.65). These values are indicative of the regional climatic context during the late dry season, as expected for a wildfire-prone location in Ubon Ratchathani Province. The moderate standard deviations for both parameters demonstrate environmental variability, further underlining the importance of multi-parameter surveillance in wildfire risk assessment. For smoke concentration, measured in analog-to-digital converter (ADC) units, the mean was 744.48 (SD = 636.61), and PM2.5 concentrations averaged 49.66 µg/m

3 (SD = 58.84). Notably, both smoke and PM2.5 exhibited high variability, reflecting the sporadic onset of combustion events and particulate matter fluctuations characteristic of forest environments subject to episodic burning or atmospheric perturbations. The magnitude of these fluctuations strengthens the case for real-time alerting, as provided by the deployed system, since elevation in either metric can signify the onset of combustion and associated fire risk with greater immediacy than temperature or humidity alone.

4.3. Testing the System’s Remote Communication Efficiency

The experiment involved the installation of equipment cabinets at predetermined intervals to assess the performance of the system’s single-hop, long-distance wireless communication. The distance between the sensor node and central control cabinet was systematically varied across five intervals (300, 600, 900, 1200, and 1500 m) at different sites within Sok Chan Forest, as illustrated in

Figure 13. The resulting data were used to calculate the average signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and received signal strength indicator (RSSI) and to evaluate the completeness of data reception for each series of transmissions.

Table 2 presents the general parameter settings for the LoRa modules that were used in the point-to-point communication, as well as the selected frequency bands for the data transmission experiments. In this study, we used SF = 10 and BW = 125 kHz as a conservative setting to ensure positive SNR margins in a forested environment. Increasing the spreading factor generally improves receiver sensitivity and range (higher processing gain), but it increases time on air and can therefore increase latency and reduce network capacity. Conversely, lower spreading factors increase data rate but reduce robustness. Our measured sub-second end-to-end latency under SF = 10 indicates that the selected configuration provides an effective balance for sparse, safety-critical alarm traffic. A systematic analysis across SF7–SF12 will be included in future work to quantify the range–latency trade-off for different node densities and payload sizes.

Table 3 presents the single-hop communication performance of the proposed LoRa-based wildfire early warning system over distances from 300 to 1500 m regarding the SNR, RSSI, and packet delivery ratio. The average SNR decreases monotonically from 10.8 dB at 300 m to 3.6 dB at 1500 m, consistent with expected path-loss behavior in forested environments. Notably, the SNR remains positive at 1500 m, indicating that the received signal is still clearly above the noise floor and within the demodulation capability of the selected LoRa configuration. The RSSI similarly degrades approximately linearly with distance, from −72.4 dBm at 300 m to −100.2 dBm at 1500 m, yet remains well above the typical sensitivity limit of the SX1262 transceiver under the chosen parameters, ensuring a substantial link margin. This margin suggests that reliable communication could be sustained over longer distances or with reduced transmit power, enabling energy optimization and network scaling. Despite the gradual decline in SNR and RSSI, the packet delivery ratio remained 100% (10/10 packets) at all tested distances, demonstrating that the physical layer configuration is robust against attenuation and environmental effects in Sok Chan Forest. These results indicate that the system provides highly reliable, kilometer-scale links, essential for safety-critical wildfire alarms where missed messages may have severe consequences. Overall,

Table 2 confirms that the proposed LoRa-based system achieves stable and robust single-hop communication for up to at least 1.5 km in a forest environment, with adequate performance margins to accommodate environmental variability and deployment or configuration adaptations.

Public specifications for SX1262-class devices indicate very high link budgets with appropriate parameterization. In our measurements, the RSSI at 1500 m (−100.2 dBm) remained well above typical receiver sensitivity for the selected configuration, implying a substantial link margin. While this suggests that distances beyond 3 km may be feasible in open or less obstructed terrain, we did not conduct a controlled >3 km range campaign in this study because of site constraints (terrain, access, and safety regulations). Extending the range evaluation to 3–5 km under different vegetation density and weather conditions is therefore an important item for future work.

4.4. Detection Latency Performance Test Results

The single-hop experiments employ a sensor node and a central node positioned 300 m and 900 m apart, respectively, in Sok Chan Forest, as illustrated in

Figure 14. For the two-hop communication scenario, three nodes were deployed: sensor node A (source), sensor node B (relay), and the central node (central). Two transmission distances, 600 and 1200 m, were considered, with the intermediate node placed equidistantly between the source and the central node, as depicted in

Figure 15. For each configuration, 10 trials were conducted, and the LoRa module was configured using the parameters listed in

Table 2. The resulting measurements were used to compute the average latency and the standard deviation.

The experimental results in

Table 4 evaluate the end-to-end detection latency of the proposed wildfire early warning system under different link distances and hop counts. Overall, the system consistently achieved sub-second response times, confirming its suitability for real-time wildfire monitoring. In the single-hop configuration, the average latency increased moderately from approximately 246 ms at 300 m to 312 ms at 900 m, with low standard deviations (below 25 ms). This modest growth when distance is tripled indicates that protocol and processing delays dominate over propagation time and that the communication performance remains stable and predictable across the tested ranges. In the two-hop configuration, the use of a relay node increases the average latency to about 428 ms at 600 m (two 300 m hops) and 536 ms at 1200 m (two 600 m hops). These increments of roughly 150–200 ms relative to comparable single-hop distances primarily reflect additional processing and retransmission at the relay. Although the standard deviations are slightly higher (around 30–40 ms), the variability remains limited, suggesting that multi-hop forwarding does not introduce significant jitter.

4.5. Alarm Accuracy Evaluation Results

The results of the controlled alarm accuracy experiment, in which 60 labeled measurement cycles (20 per class) were collected under the Normal, Surveillance, and Fire conditions. The confusion matrix compares the system’s automatic classification with the ground-truth labels established by expert observers.

The controlled alarm accuracy experiment shows that the proposed wildfire early warning system demonstrated high classification performance across all three alarm states (Normal, Surveillance, and Fire). As summarized in

Table 5, the system correctly classified 55 of 60 measurement cycles, corresponding to an overall accuracy of 91.7% (

Table 6). Misclassifications occurred only between the Normal and Surveillance states; no Fire samples were labeled as Normal, indicating that the system did not miss any true fire events under the tested conditions.

Class-wise metrics further underscore the robustness of the alarm logic. For the Fire class, the system achieved perfect precision (1.000), reflecting the absence of false positive fire alarms. This property is critical for field deployment, as frequent false alarms can erode operator trust and contribute to alarm fatigue among firefighters and local stakeholders. Fire class recall was also high (0.952), with only one Fire instance downgraded to Surveillance. Although such an underestimation is acceptable in a controlled experiment, it suggests that under marginal conditions near decision thresholds, a developing fire may initially be classified as a lower-severity event. However, the resulting Surveillance status still triggers heightened attention and monitoring, mitigating the operational impact of this error.

The Normal and Surveillance states exhibit balanced performance, with precision and recall values of 0.900 and 0.895, respectively, and nearly identical F1-scores (0.900 and 0.895). The symmetric error pattern (two Normal samples classified as Surveillance and two Surveillance samples classified as Normal) indicates that most misclassifications arise near the boundary between non-critical and pre-alert conditions. This is consistent with threshold-based decision rules that combine temperature, smoke, and PM2.5 measurements, where natural variability and transient fluctuations can yield borderline readings. From a safety perspective, this behavior is conservative: occasional escalation from Normal to Surveillance increases sensitivity to emerging risks, while the rare downgrade from Surveillance to Normal may modestly reduce lead time without obscuring clearly hazardous events.

Overall, the metrics in

Table 6 indicate that the FireLo backend classification rules, in combination with the deployed sensing hardware, provide reliable multi-class discrimination suitable for operational wildfire monitoring. The system prioritizes accurate fire detection while maintaining a relatively low false alarm rate and preserving meaningful differentiation between the Normal and Surveillance states. Together with the communication reliability and low-latency performance reported elsewhere in this study, these results support the feasibility of the proposed LoRa-based system as a field-deployable solution for real-time wildfire risk detection in remote forest environments.

4.6. Efficiency of the LoRa-Based Wildfire Early Warning System

The evaluation metrics reported in

Table 7 are designed to assess operational efficiency rather than algorithmic novelty. The benchmark for comparison is the baseline operational workflow previously used in the study area, which relied on manual observation, radio communication, and delayed reporting. Accordingly, pre-implementation scores represent participant perceptions of efficiency under these conventional practices, while post-implementation scores reflect perceived efficiency after the deployment of the proposed LoRa-based system. This before–after (paired) design allows a direct, context-specific comparison of practical effectiveness under real operating conditions.

The combined descriptive and inferential analyses demonstrate that the proposed LoRa-based early warning system substantially enhances operational efficiency in wildfire detection and response in Sok Chan Forest. Post-implementation ratings across all evaluation items were in the “High” range, with an overall mean () of 3.84 (S.D. = 0.40), indicating consistently positive perceptions among both domain experts and firefighters.

From a descriptive standpoint, participants reported notable improvements in the system’s core technical functions. The highest post-implementation mean was observed for “improvement in response time to potential wildfire incidents” ( = 4.12, S.D. = 0.32), underscoring the system’s capacity to shorten detection-to-notification intervals. This finding is consistent with the measured detection latency, which remained well below one second even under two-hop communication, and supports the feasibility of using the system in time-critical emergency operations. Likewise, the stability of long-range communication ( = 4.01, SD = 0.50) aligns with the communication tests, which yielded a 100% packet reception rate up to 1.5 km under forest conditions, with positive SNR margins and RSSI values safely above the receiver sensitivity threshold.

The inferential analysis further corroborates these improvements. For all items, post-implementation scores were significantly higher than pre-implementation baselines (all p < 0.001), indicating that the observed gains are unlikely to be due to chance. The largest mean differences were found for wireless communication reliability (d = 1.41) and response time enhancement (d = 1.57), suggesting that the integration of LoRa communication and automated alerting directly addresses the limitations of traditional fire detection methods in remote forests, such as delayed reporting and fragmented situational awareness. The statistically significant overall increase in efficiency (from = 2.81 to = 3.84, t = 9.86 p < 0.001) reflects a broad-based improvement that spans sensing, communication, power reliability, and user interfaces.

Taken together, the efficiency metrics in

Table 7 should be interpreted as evidence of practical performance gains over existing wildfire surveillance practices in the study area, rather than as a comparison against alternative algorithmic approaches reported in the literature.

5. Conclusions

This study presented the development and field validation of a LoRa-based wildfire early warning prototype deployed in Sok Chan Forest, Thailand, integrating solar-powered sensor nodes that measure temperature, humidity, smoke, PM2.5, and GPS coordinates and employ LoRa peer-to-peer communication to deliver measurements to a central node for forwarding to a remote server that supports visualization and alerting via mobile and web platforms. Field experiments demonstrated reliable long-range performance, achieving a 100% packet delivery ratio up to 1500 m, with positive SNR and RSSI above receiver sensitivity under the selected LoRa configuration, while maintaining sub-second end-to-end detection latency in both single-hop and two-hop relayed transmissions to enable timely warnings. Controlled trials further indicated strong three-class alarm performance (Normal/Surveillance/Fire), yielding an overall accuracy of 91.7% and perfect precision for the Fire class, thereby reducing false fire alarms while preserving high sensitivity. In addition, user evaluation involving software experts and firefighters suggested improved perceived efficiency in detection, communication reliability, and response time relative to traditional surveillance practices. Nonetheless, the evaluation was limited to a single forest with a modest number of nodes and did not systematically assess performance under rain or fog, and the practical maximum range beyond 1.5 km remains to be established; moreover, the current detection strategy is threshold-based. Future work will therefore extend testing across seasons and harsher weather; optimize communication parameters (e.g., spreading factor and transmit power) to balance reliability, latency, and energy consumption; and investigate hybrid vision-based and multimodal approaches, including YOLO-based smoke/flame detection combined with environmental sensing, to improve discrimination near decision thresholds and reduce borderline misclassifications.