1. Introduction

Zero-inflated (ZI) count data arise when the observed number of zeros is substantially larger than what standard count distributions would predict [

1,

2,

3]. This phenomenon has been widely reported in diverse application domains and is particularly common in high-dimensional sparse settings such as document–keyword matrices [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In such data, zeros may occur not only because the expected count is small, based on sampling zeros, but also because a separate mechanism generates structural zeros [

8,

9,

10]. This characteristic is frequently observed in practice. For example, in a document–keyword matrix, each entry represents the frequency of a keyword in a document, and most entries are zero because each document contains only a small subset of the overall terms [

2,

6,

7,

11]. Similar ZI patterns are also common in scientific text mining, biomedical measurements, and other sparse event-count environments [

1,

4,

5,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

A large body of statistical literature has developed explicit probabilistic models for ZI counts. The representative approaches include the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) and zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models, which combine a Bernoulli component for structural zeros with a Poisson or negative binomial component for positive counts [

1,

8,

14,

18]. These models improve interpretability by separating the inflation process from the count process, and ZINB further accommodates overdispersion through the variance structure of the negative binomial distribution.

However, classical ZI regression is often challenged by modern data settings [

8,

9,

19,

20,

21,

22]. First, the covariates, such as keyword frequency of document–keyword matrix, can be high-dimensional and sparse. Second, the inflation and count parts may suffer from identifiability and optimization instability under strong sparsity. Third, most ZI models treat observations as independent, thus ignoring potentially useful relationships among samples.

In parallel, machine learning has explored flexible predictive models for sparse counts [

23,

24,

25]. Two parts of the learning strategies, which are classification for zero or non-zero, and regression for positive values, generalize the hurdle perspective, while likelihood-based deep models estimate distributional parameters using neural networks. Although these methods can handle nonlinearity and large feature spaces, they still typically rely on the independent and identically distributed assumption at the sample level. In many applications, however, samples are not isolated. Text documents, for instance, form natural similarity structures such as shared terminology, overlapping technical domains, and co-occurrence patterns. Exploiting such relational structure can act as a form of information sharing, which is particularly beneficial under severe sparsity and noise.

Graph neural networks (GNNs) provide a general mechanism for representation learning on graphs by aggregating and transforming neighborhood information [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Among them, the graph convolutional network (GCN) is a widely used architecture that performs feature mixing via normalized adjacency-based propagation [

30,

31,

32,

33]. However, deep GCN stacks can introduce redundant computation and may require careful tuning to avoid over-smoothing. Simple graph convolution (SGC) simplifies GCN by collapsing multiple propagation steps into a linear graph filter followed by a simple predictor, yielding substantial computational benefits while retaining competitive performance in many tasks [

30].

The motivations for studying the proposed method in this paper are as follows:

- -

The ZI count data with high-dimensional sparsity often lead to unstable estimation and degraded prediction accuracy in conventional ZI regression.

- -

Most classical ZIP and ZINB formulations assume independent observations and ignore potentially informative relational structure among samples, such as document similarity.

- -

The graph-based convolution can enable information sharing across similar samples, but practical ZI modeling benefits from lightweight and interpretable convolution, such as SGC.

We represent the research questions (RQs) of our paper as follows:

- -

RQ1: Can incorporating graph convolution via SGC improve the predictive performance of classical zero-inflated models such as ZIP and ZINB for sparse zero-inflated count data?

- -

RQ2: Are the performance gains of graph-enhanced models (ZIP+SGC, ZINB+SGC) stable under different zero-inflated ratios and repeated runs, as measured by MAE and RMSE?

In addition, we build the working hypotheses of our research as follows.

- -

Hypothesis1: ZIP+SGC achieves lower MAE and RMSE than the baseline ZIP under the same experimental setting.

- -

Hypothesis2: ZINB+SGC achieves lower MAE and RMSE than the baseline ZINB under the same experimental setting.

Furthermore, the contributions of this paper can be summarized in three points as follows:

- -

We propose a unified framework that couples SGC-based graph propagation with ZIP and ZINB heads for zero-inflated count prediction based on ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC.

- -

The proposed method is lightweight and interpretable; graph convolution is implemented via a fixed propagation operator, while the ZI heads are trained by standard maximum likelihood estimation (MLE).

- -

Through controlled simulation experiments under varying zero ratios, we demonstrate consistent reductions in mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) compared with the corresponding non-graph baselines.

To provide a clear roadmap of the proposed approach, we summarize the methodology as follows:

Step1. Data preparation: Represent the observations as a feature matrix X with a zero-inflated target count y.

Step2. Graph construction: Build an observation graph by connecting each sample to its k-nearest neighbors using a similarity measure, forming an adjacency matrix A.

Step3. Normalization and self-loops: Add self-loops and compute a normalized propagation operator to stabilize message passing and prevent numerical scaling issues.

Step4. SGC propagation: Apply SGC propagation for K steps to obtain graph-smoothed features, capturing relational information among observations.

Step5. Zero-inflated modeling: Fit probabilistic ZIP and ZINB regression heads using the propagated features, yielding ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC, and estimate parameters via maximum-likelihood.

Step6. Evaluation and comparison: Evaluate predictive performance using MAE and RMSE, and compare against baseline ZIP and ZINB without graph propagation.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews statistical and machine learning approaches to zero-inflated modeling.

Section 3 presents the proposed ZI-SGC methodology.

Section 4 reports experimental results, and

Section 5 concludes with a discussion and future directions.

3. Zero-Inflated Data Analysis Using GNNs with Convolution

In this section, we present an efficient method for zero-inflated data analysis with GNNs and convolution. GNNs are neural network models that perform representation learning on graph-structured data consisting of nodes and edges. To improve clarity and ensure that each variable appearing in the equations used in this paper, we summarize the descriptions and ranges of all symbols used throughout this section in

Table 1.

To construct our GNN model, we consider a graph

, where

and

represent a node (vertex) and an edge (connection), respectively [

26,

36,

37]. GNNs are defined as a family of neural network models that learn graph data [

29]. Among the models of GNNs, we consider a graph convolutional network (GCN) in this paper. GCN is one of the representative GNN architectures that use graph convolution, a method of normalizing and merging neighboring features [

30]. Combining zero-inflated (ZI) and simple graph convolution (SGC), we propose a ZI-SGC framework that performs feature propagation and graph convolution based on SGC to simultaneously reflect excess zeros and relational structure between observations in zero-inflated count data and applies this to ZIP or ZINB models. The core idea is that by transforming

to

through graph convolution, the existing zero-inflated regression model can estimate parameters more stably. Denoising and smoothing are used in this process. The SGC in this paper is a simplified form of K-step propagation that removes the layer-wise nonlinearity of GCN. For

n observations (

),

and

are target and feature, respectively. We define the data

as follows [

30]:

In Equation (2),

p is number of features. Using the data defined in this way, we build a model that predicts the target using features and obtain

that is the predicted value of

and the probability of zero

. To analyze zero-inflated data using the ZI+SGC model, we construct a graph

with each observation as a node. The edges of the graph are based on similarities between observations, such as cosine similarity. For sample

, the top k neighbor set

is constructed and adjacency

A is defined as follows [

30]:

In Equation (3),

represents the edge weight connecting nodes

i and

j. A larger

value indicates that nodes

i and

j are more similar and more strongly connected. The

value of 0 indicates that the two nodes are not connected. In addition,

is a function representing the similarity between two feature vectors

and

. Commonly used similarity functions include cosine similarity, Gaussian similarity. In this paper, we use cosine similarity and construct k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph accordingly. Using the adjacency

, we build GNNs model with convolution via SGC. The SGC propagation is defined based on normalized adjacency with a self-loop. First, adjacency-including self-loop is defined as follows [

30,

32]:

In Equation (4), where

I is the identity matrix, which adds a self-loop to each node, we define

as degree matrix of

. In addition, a propagation operator

is constructed by normalizing

as shown in Equation (5) [

30,

32].

In general, we choose symmetric normalization for

. We compute the degree matrix

as

. SGC performs smoothing of the features through K-step propagation and then computes

and apply a linear predictor [

30,

32]. As

K increases, it reflects a wider range of K-hop neighborhood information. This simplification of SGC reduces the computational load while maintaining the performance of GCN.

has low pass filtering properties in the graph spectral domain, resulting in smoothness that promotes feature similarity between adjacent nodes. Therefore, even in sparse, noisy, zero-inflated data, denoising effects utilizing neighborhood information can be expected. We fit the following zero-inflated count regression using

obtained by SGC as a covariate.

In Equation (6),

and

are the mean and zero-inflation probability of the count component. Also,

and

are the sigmoid function and covariate of inflation part. The likelihood of the traditional zero-inflated model is represented as follows:

In Equation (7),

is a probability distribution for count data, such as Poisson and negative binomial distributions. Since we estimate the parameter

using MLE, we use the following objective function:

The advantage of SGC is that the

is calculated first, and subsequent learning becomes an optimization problem of zero-inflated regression heads such as ZIP and ZINB, so Equation (8) can be used. Finally, we predict the output using the following expectation and probability in Equation (9):

To evaluate the performance between the proposed model and existing models, we use the following MAE and RMSE [

25,

34]:

In Equation (10), and are actual and predicted values, respectively. We describe our proposed model for zero-inflated data analysis, called ZI-SGC, in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Zero-Inflated Simple Graph Convolution (ZI-SGC) Model |

Input:

: number of features)

k: k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) parameter

K: number of propagation steps

Symmetric or random walk: normalization types

Count regression head: ZIP or ZINB

Output:

: fitted parameters

: predictions

: probability of zero occurring

MAE: mean absolute error

RMSE: root mean squared error

Procedure:

1. Preprocessing

(1-1) Applying standardization to X depending on data scale

2. Graph Construction

(2-1) Building k-NN graph

(2-2) Obtaining adjacency matrix A

3. Self-Loop

(3-1) Computing

4. Normalization

(4-1) Computing

5. Convolution of SGC

(5-1) Computing

6. Fitting Zero-Inflated Head

(6-1) Modeling ZIP and ZINB by maximizing log-likelihood

(6-2) Minimizing objective function on parameter

7. Inference and Evaluation

(7-1) Estimating

(7-2) Computing MAE and RMSE |

Through the procedure of Algorithm 1, we explain the entire process of zero-inflated data analysis, from the preprocessing of original data to the final parameter inference and performance evaluation. Next, the proposed method of this paper is presented in a procedure as shown in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 summarizes the zero-inflated data analysis procedure proposed in this paper. First, the input is zero-inflated count data with excessive zeros, consisting of a feature matrix

X for each observation and a target count

y. Next, a graph is constructed using similarity relationships between observations and expressed as an adjacency matrix

A. Self-loops and normalization are then added to ensure stable graph propagation. SGC is applied to the prepared graph, transforming the features of each observation into a propagated representation that reflects neighborhood information. Finally, a zero-inflated regression head is trained using the transformed features as input. In this study, ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC are used as representative models. Model performance is evaluated using MAE and RMSE to determine whether combining SGC-based graph convolution improves prediction performance compared to the baseline ZI model.

4. Experiments and Results

To show the improved performance of our proposed models, we use simulation and real datasets. The simulation data used in this experiment was generated to evaluate the performance of SGC-based graph propagation in environment of graph-structured zero-inflated count regression. The target variable is generated by the latent signal smoothed through the graph neighborhood, and the features are generated by mixing the signal with noise. We describe the process of generating the simulation data used in this experiment in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Simulation Data Generation for Zero-Inflated Data Analysis |

Input:

: number of nodes

: number of features

: number of communities

: within edge probability

: between edge probability

: propagation steps

: zero ratio

: noise scale

: clipping constant

Output:

: propagation operator

Procedure:

1. Stochastic Block Model

(1-1)

(1-2)

2. Normalization

(2-1) )

(2-2)

3. Latent Signal

(3-1)

(3-2) : number of propagation steps)

(3-3) to zero mean and unit variance

4. Feature Construction

If j ≤ 3 (for j = 1, 2, …, p)

5. Count Mean

6. Zero-Inflated Sampling

(6-1)

(6-2)

(6-3)

7. Zero-Inflated Calibration

(7-1)

(7-2)

8. Injection of structural zeros

|

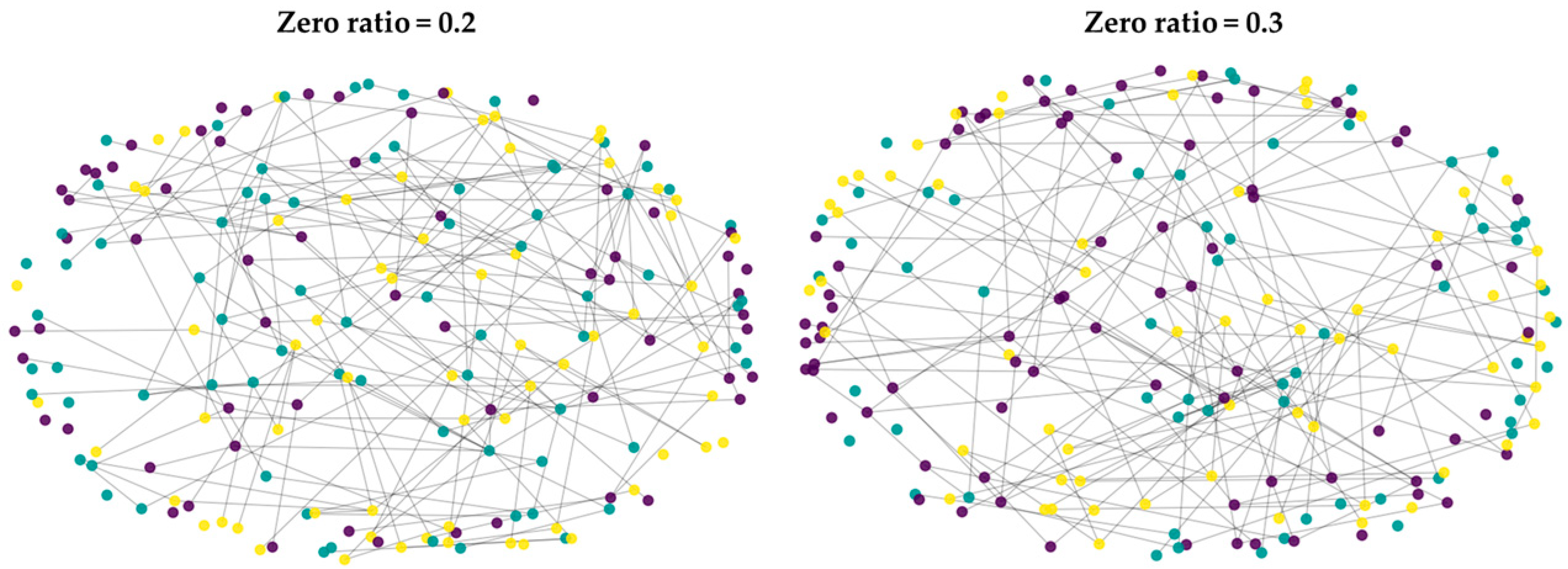

Based on Algorithm 2, we divided the zero ratio into 0.2 (20%) and 0.3 (30%) and generated experimental data, respectively. To verify the quality of the generated simulation data, we performed graph visualization on each data set.

Figure 2 shows the results of the graph visualization according to the zero ratio.

In

Figure 2, we show the results of visualizing simulation data generated by setting the zero ratio of the target variable to 0.2 and 0.3, respectively, in the graph based on the same Stochastic Block Model (SBM).

Figure 2 intentionally visualizes the same graph topology for zero ratios 0.2 and 0.3 because the graph is constructed from the covariates

X (sample similarity) and is treated as an underlying relational structure that does not change across the two conditions. The experimental factor is the zero-inflation level of the target count

Y, the probability of structural zeros in the zero-generation mechanism. Holding the graph fixed while varying only the target’s zero-inflation level provides a controlled comparison: it isolates the effect of increasing zero inflation without conflating it with changes in graph connectivity. Therefore, the role of

Figure 2 is not to show topology differences across conditions, but to confirm that the same relational structure is used and to contextualize performance comparisons under different zero-inflation regimes. In this visualization, node color represents community label, and the spring layout is used to ensure that the graph’s connectivity and community structure are maintained. In both settings where the zero ratio is 0.2 and 0.3, a pattern of communities being mixed but internally more densely connected is observed, which means that a graph structure reflecting zero inflation as designed during the data generation process was stably formed. This graph provides a structure that enables information diffusion through neighborhoods, which serves as the basis for meaningful SGC propagation. Therefore, we carried out a performance evaluation between the comparative models using the generated simulation data. Next, we represent the degree distribution according to the zero ratio in

Figure 3.

This figure presents the degree distributions of the simulation graphs generated when the zero ratio of the target variable is set to 0.2 and 0.3, respectively. In this experiment, the zero ratio is achieved by adjusting the structural zero probability

of the response variable

, and is not a parameter that changes the graph topology itself. Therefore, as observed in

Figure 3, the sparse network characteristics, in which the degree is mainly concentrated in the range between 0 and 3, and relatively large degrees appear only in some nodes, are consistently maintained in both settings. This demonstrates that the connection method based on SBM in the data generation process operates stably, and the graph structure, such as connection density and neighborhood size, does not significantly change even when the zero ratio changes. In particular, the similarity of the degree distributions suggests that the observed differences in subsequent performance comparisons are not simply due to the denser graph favoring propagation, but rather to the model being placed in more challenging prediction situations as the level of zero inflation itself increases. In other words, the experiments with zero ratios of 0.2 and 0.3 systematically varied zero inflation while keeping the graph structure nearly fixed. This design allows for a clearer isolation and evaluation of the performance differences between the proposed model and existing models, attributing them to SGC propagation.

Furthermore, the fact that the average degree of nodes in the sparse graph is not large suggests that the propagation of SGC

operates by gradually spreading information within a limited neighborhood, rather than shuffling a large number of neighbors at once. This aligns with the design of our simulation, which generates latent signals in a smoothed form through neighborhoods while reducing the risk of over-smoothing due to excessive propagation. Consequently, the degree distribution in

Figure 3 serves as a structural diagnostic, confirming that the experimental graph is sparse and that changes in the zero ratio do not disrupt the graph topology. Since the results in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 confirmed that the simulation data were appropriately generated for the experiments in this paper, we conducted experiments comparing our proposed ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC models against the existing representative zero-inflated models, ZIP and ZINB.

Table 2 shows the results comparing MAE and RMSE when the zero ratio is 0.2.

Table 2 presents the results comparing the prediction performance of ZIP, ZINB, and our proposed models, ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC, under the condition of zero ratio = 0.2. The SGC provides a representation that reflects neighborhood information by transforming features into the form

, using the propagation operator

defined in the graph between observations. This graph smoothing can contribute to recovering meaningful signals from noisy features in zero-inflated sparse count data. Our experimental results show that ZIP+SGC improves performance compared to the original ZIP. Specifically, as shown in

Table 2, while the MAE of ZIP was 30.65, ZIP+SGC’s decreased to 27.85, and its RMSE also decreased from 106.34 to 102.97. This suggests that features generated through graph propagation based on SGC can significantly reduce prediction errors compared to the traditional ZIP model.

The same trend is observed in the models based on the negative binomial distribution. While the MAE of the conventional ZINB was 34.09, the proposed model, ZINB+SGC, reduced it to 29.75, and the RMSE also improved from 120.01 to 115.77. In other words, the graph-based representation in this study consistently improved performance not only in the ZIP model but also in ZINB, which considers overdispersion. This demonstrates that even in situations where zero-inflation and overdispersion are simultaneously included, the neighborhood signal derived from the graph structure substantially contributes to improved prediction accuracy. Meanwhile, the standard deviation (SD) reflects variability across repeated runs. In

Table 2, while the SDs of models incorporating SGC are similar to or slightly larger than the baseline, the consistent decrease in mean error supports the notion that graph propagation provides a more advantageous representation on average. In summary, under the zero ratio of 0.2, ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC simultaneously improved both MAE and RMSE compared to their respective baselines, confirming that the SGC-based expansion method proposed in this study is an effective approach to improving the performance of zero-inflated count models. Next,

Table 3 shows the performance comparison results when the zero ratio is 0.3.

Table 3 presents the results of a comparison of the prediction performance of existing zero-inflated models and the proposed models in this study under the zero ratio = 0.3 condition, similar to

Table 2. Consistent with the trend observed under the zero ratio = 0.2 condition in

Table 1, these results show that models incorporating SGC-based propagation achieve lower prediction errors compared to their respective baselines of ZIP and ZINB. Specifically, ZIP+SGC reduced the MAE from 28.80 to 27.43 and improved the RMSE from 107.70 to 105.83 compared to the baseline ZIP. This suggests that even when using the same ZIP, feature representation that reflects neighborhood information through graph propagation can contribute to improved prediction accuracy. Furthermore, in a negative binomial-based comparison, the proposed model ZINB+SGC outperformed the baseline ZINB with an MAE of 29.74 and an RMSE of 112.29, and with an MAE of 27.41 and an RMSE of 107.17. In particular, the improvement in RMSE of ZINB+SGC was relatively large, indicating that SGC also worked advantageously in mitigating large errors in count data.

The SD represents variability across replicated experiments, and

Table 3 shows that models combining SGC exhibit similar or slightly reduced SD compared to the baseline. For example, the MAE SD of ZIP is 7.70, while that of ZIP+SGC is 7.41. This indicates that the performance improvement is not limited to a specific replicate but rather remains relatively stable across replicated experiments. In summary, even when the zero ratio increased to 0.3, ZIP+SGC outperformed ZIP, and the same was true for ZINB+SGC and ZINB. This confirms that the graph-enhanced representation proposed in this study provides consistent performance improvements in a zero-inflated count regression environment. In addition, the fact that the models based on SGC maintain superior performance compared to the baseline even when the zero ratio increases from 0.2 to 0.3, which increases prediction difficulty, suggests the robust applicability of the proposed method. Next, we present the MAE plot in

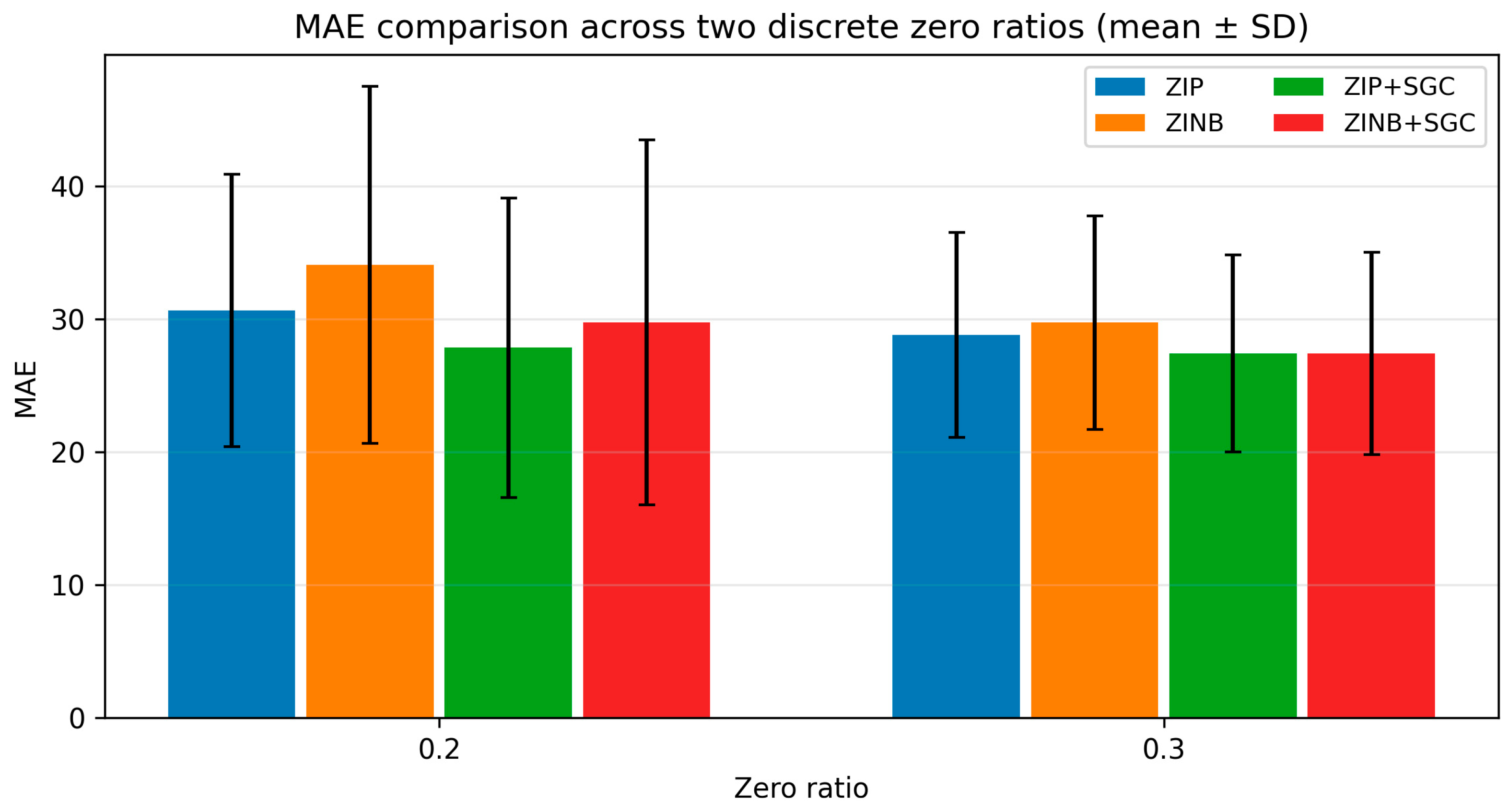

Figure 4 to check the performance difference between the compared models according to the zero ratio.

Figure 4 compares the MAE of four models (ZIP, ZINB, ZIP+SGC, and ZINB+SGC) in the form of mean ± SD when the zero-inflated ratio is varied from 0.2 to 0.3. Overall, models incorporating SGC achieve lower MAE values than their respective baselines under all conditions, suggesting that representation via graph propagation consistently improves performance in zero-inflated count prediction. First, at zero ratio = 0.2, ZINB among the baseline models exhibits a lower MAE than ZIP. However, variants incorporating SGC (ZIP+SGC, ZINB+SGC) achieve additional error reduction for both baselines. Notably, ZINB+SGC exhibits the lowest MAE among the four models, demonstrating that performance can be maximized when the ZINB head, which accounts for overdispersion, is combined with graph-based smoothing. This is consistent with the quantitative comparison results in

Table 2.

Even when the zero ratio is increased to 0.3, the performance rankings are generally maintained, and the superiority of the model based on SGC persists. Specifically, ZIP+SGC exhibits lower MAE than ZIP, and ZINB+SGC exhibits lower MAE than ZINB, confirming the robustness of the graph-enhanced representation even when zero inflation increases prediction difficulty. Furthermore, the error bars of SD in

Figure 4 show that the SGC-based model tends to lower the average error while maintaining a similar level of variability to the baseline. This supports the notion that the performance improvement is not limited to a specific iteration but is relatively stable across repeated runs. In summary,

Figure 4 visually demonstrates that the proposed models incorporating SGC consistently achieve lower MAE than the baseline even when the zero ratio increases from 0.2 to 0.3. This experimentally supports the core assertion of this study that feature representations incorporating neighborhood information through graph propagation can improve prediction accuracy on sparse and zero-inflated count data. Also, we show the RMSE plot in

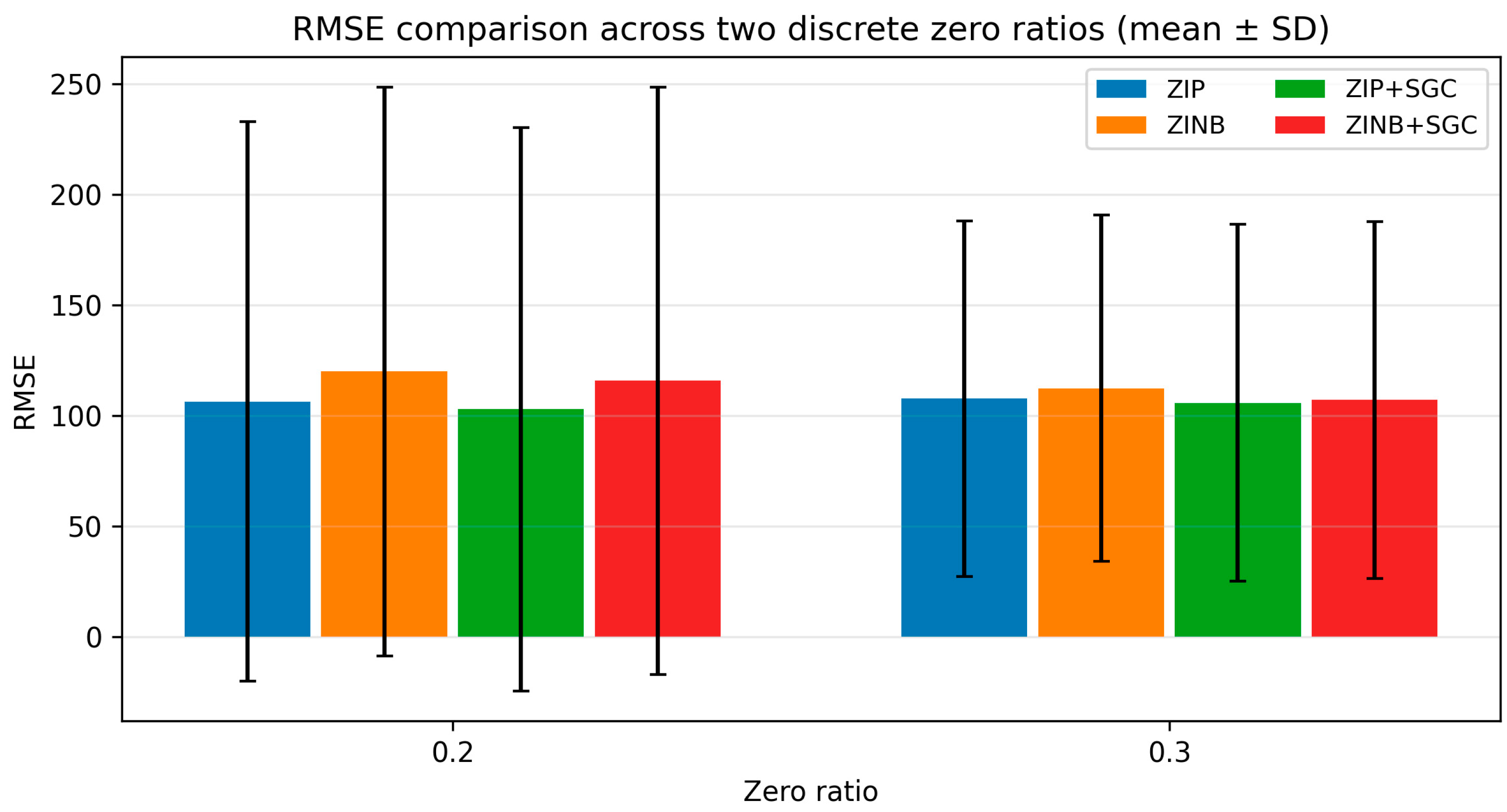

Figure 5 to compare the performance between existing zero-inflated models and our proposed models according to the zero ratio.

Similar to the results in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 also compares the RMSE between the comparison models in the form of mean ± SD when the zero ratio is set to 0.2 and 0.3. The overall pattern is similar to the MAE results in

Figure 4, and it is visually confirmed that the proposed models incorporating SGC achieve lower RMSE values than the respective baseline models. At zero ratio = 0.2, among the baseline models, ZIP and ZINB exhibit relatively large RMSEs, while ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC show reduced RMSEs, demonstrating superior prediction performance. This suggests that feature representations that incorporate neighborhood information through graph propagation contribute to reducing prediction errors. In particular, ZINB+SGC tends to exhibit the lowest RMSE across both zero ratio settings, suggesting that combining the ZINB head, which accounts for overdispersion, with SGC-based smoothing can effectively mitigate large errors.

Increasing the zero ratio to 0.3 strengthens zero inflation, making the prediction problem more difficult. However, the SGC-based model maintains superior RMSE compared to the baseline models of ZIP and ZINB. This demonstrates that the proposed method is relatively robust to changes in zero inflation levels. Furthermore, the error bars (SD) in

Figure 5 represent variability across repeated runs. The SGC-coupled model exhibits a tendency to lower the average RMSE while maintaining variability similar to the baseline. This supports the idea that the performance improvement is not limited to a specific iteration but is reproducible on average. Consistent with the MAE results in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 demonstrates that the graph-enhanced representation improves performance in zero-inflated count regression not only in terms of average error but also in terms of RMSE, which is sensitive to large errors. This experimentally supports the notion that our proposed method can simultaneously improve prediction stability and accuracy in sparse and zero-inflated data.

To address the concern that simulation alone may raise concerns about generalizability, we conducted an experiment using real data rather than simulation data. The dataset is a document–keyword matrix constructed from patent documents in the domain of synthetic data technology. The proposed framework is designed to solve a practical prediction problem that frequently occurs in text mining and patent analytics, modeling and predicting sparse zero-inflated keyword frequencies. In the matrix, each entry is the frequency of a keyword in a document, and the matrix is typically dominated by zeros because each document contains only a small subset of the vocabulary. This produces a challenging zero-inflated count prediction task, where the goal is to predict a target keyword’s count from other sparse keyword signals while exploiting relational structure among documents. We added a real-data experiment based on a patent document–keyword matrix with 2929 documents and 14 keyword variables. The target keyword (Y) is synthetic, and the remaining keywords are used as predictors (X) as follows: algorithm, analysis, computing, data, deep, distribution, generating, intelligent, learn, machine, network, neural, and statistics. This real dataset exhibits strong sparsity; the overall proportion of zeros in X is approximately 72.4%, and the zero ratio of the target Y is approximately 39.6%. We show the results of performance comparison between comparative models with real data in

Table 4.

Although the performance improvement on the real dataset is smaller than in the simulation study, which is expected because real-world relational structure and noise are more complex, the proposed models still show consistent gains. In our experiments, the proposed models achieve the best average MAE among all compared methods. Similarly, RMSE is improved compared to the corresponding baselines. These results support that incorporating lightweight graph convolution SGC can provide measurable benefits for real-world sparse zero-inflated count prediction, even when the improvement magnitude is modest.

5. Discussion

The proposed framework targets a common real-world setting of zero-inflated count data, in which zeros dominate because events or terms occur in only a small fraction of observations. This phenomenon is prevalent across many practical domains, including text analytics, business intelligence, and related applications. In such scenarios, a key implication is that prediction robustness can be improved by exploiting relational structure via lightweight graph propagation. As a result, the framework can support downstream decision-making tasks such as identifying influential features, prioritizing items for review, and detecting rare yet important patterns.

Our results indicate that combining SGC with probabilistic zero-inflated heads can yield measurable performance gains while preserving interpretable model components. Compared with purely neural approaches, ZIP and ZINB explicitly separate the zero-generation mechanism from the count-generation mechanism, which facilitates interpreting why zeros occur and how counts vary conditional on being non-zero. Meanwhile, SGC-based convolution provides a computationally efficient way to share information across related observations, which is particularly beneficial when individual samples contain limited signal due to sparsity. Importantly, SGC avoids the complexity of deeper GCN architectures by using a simplified propagation operator, which can be advantageous for stable training and reproducible implementation.

While simulation experiments often demonstrate clearer gains under controlled data-generating mechanisms, real-world datasets typically introduce additional challenges, including heterogeneous noise sources, imperfect similarity measures, and complex dependencies that may not be fully captured by a simple k-NN graph. Consequently, performance improvements in real applications may be smaller yet still meaningful, especially when the gains are consistent across repeated train–test splits. This observation is consistent with broader findings in graph-based learning, where the effectiveness of convolution depends strongly on the quality of graph construction and its alignment with the prediction task.

This study has several limitations. First, an inaccurately constructed graph can propagate noise and degrade performance. Second, over-smoothing may occur when the propagation depth (K) is too large, leading to less discriminative representations. Third, likelihood-based estimation for ZIP/ZINB can encounter convergence issues in extremely sparse or high-dimensional settings, which may require careful regularization or simplified inflation components. Finally, although the proposed framework is computationally lightweight relative to deeper GNNs, scaling to very large graphs may still require approximate nearest-neighbor search and optimized sparse linear algebra routines.

Overall, our findings complement established work on zero-inflated modeling and recent advances in graph representation learning. Classical ZIP and ZINB provide principled probabilistic tools for handling excess zeros, whereas modern graph methods show that neighborhood aggregation can improve predictive performance when relational information is informative. By integrating these directions, the proposed ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC frameworks offer a practical compromise between interpretability and graph-based learning capability. The results support the broader view that lightweight graph propagation can improve prediction in sparse count settings when the constructed graph reflects meaningful similarity, and they motivate further exploration of adaptive graph construction and more expressive graph neural architectures for zero-inflated data.

To further contextualize our findings within the related literature, prior studies on zero-inflated modeling have shown that accounting for excess zeros and over-dispersion is crucial for stable inference and prediction in sparse count settings such as ZIP and ZINB formulations and their extensions. These findings collectively suggest that robust modeling of zero inflation benefits from both distributional assumptions and structure-aware information sharing, which motivates our ZI-SGC design. In addition, several recent works have emphasized that improving prediction under severe sparsity often requires either enhanced learning strategies for imbalanced or zero-inflated data in boosting-based improvements to zero-inflated models or incorporating additional structural information to share signal across related observations. For example, boosting-enhanced zero-inflated modeling has been reported as an effective strategy for imbalanced settings, while graph-based approaches have been increasingly explored for spatiotemporal or relational count prediction problems. Our results are consistent with these general findings, incorporating lightweight graph propagation, SGC provides a practical way to leverage relational structure without sacrificing the interpretability of probabilistic ZIP and ZINB heads. At the same time, the modest improvement observed on the real-world document–keyword matrix is also aligned with the broader evidence that performance gains from graph convolution depend strongly on graph construction quality and the alignment between the graph and the prediction task.

Future work may include exploring alternative similarity measures, jointly learning the graph with the prediction model via graph structure learning, extending the framework to spatiotemporal graphs for event-count modeling, and incorporating uncertainty quantification to support decision-making in high-stakes domains.

6. Conclusions

This paper investigated ZI count prediction problems in which excessive zeros and severe sparsity make conventional count regression unstable and less accurate, especially when covariates are high-dimensional. To address these problems, we proposed a graph-based ZI learning framework, called ZI-SGC, which integrates SGC with probabilistic zero-inflated regression heads such as ZIP and ZINB. The proposed approach constructs an observation graph among samples, applies lightweight graph convolution through SGC propagation to obtain neighborhood-aware covariates, and then fits ZIP or ZINB heads via maximum likelihood learning. This design preserves the probabilistic interpretability of ZI models while exploiting relational structure for denoising and signal recovery.

Through controlled simulation experiments with varying zero ratios between 0.2 and 0.3, we consistently observed that incorporating SGC improves predictive accuracy. In particular, both ZIP+SGC and ZINB+SGC achieved lower prediction errors than their corresponding baselines of ZIP and ZINB by MAE and RMSE, and these gains remained stable across repeated runs. These results suggest that graph-enhanced representations can be beneficial in ZI count regression settings, even when the underlying ZI heads remain unchanged.

Despite these promising findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the performance of ZI-SGC depends on graph construction choices such as similarity measure, k-NN parameter, and normalization, as well as the propagation depth K, which may introduce sensitivity and require systematic tuning. Second, SGC employs a fixed linear propagation operator, which yields efficiency and stability. However, more expressive GNN architectures may capture richer relational patterns may capture more complex relational patterns at the cost of additional complexity. Future work will extend ZI-SGC in several directions. We will explore principled strategies for graph construction and hyperparameter selection, such as robust similarity metrics, adaptive neighborhood size, and validation-based K selection, and investigate more expressive graph neural variants and hybrid heads for improved modeling flexibility. In addition, scalability to large graphs and inductive settings of generalizing to unseen nodes will be considered to enhance practical utility in large-scale, sparse-count prediction problems.