1. Introduction

As cyber threats continue to evolve in sophistication, persistence, and stealth, analyzing volatile memory has become a cornerstone of modern cybersecurity defense. Unlike static artifacts on disks, volatile memory captures the live, dynamic state of a system, offering direct insight into the runtime activities of processes, threads, and injected code segments. This makes it an indispensable source of evidence for incident responders and digital forensic analysts. However, the same dynamism that makes memory valuable also makes it volatile and complex: once a system is powered off or altered, these traces disappear, leaving analysts with the challenge of decoding massive binary dumps to reconstruct malicious behavior in real time. Volatile memory forensics can be seen as one example of algorithmic reasoning over evidential traces for digital criminalistics investigation. Recent criminology studies have applied greedy and evolutionary algorithms to difficult spatio-temporal reasoning problems in investigations [

1], and the notion of algorithmic criminology took advantage of statistical and machine-learning models to aid crime analysis [

2]. The transformer-based approach developed in the study can potentially enhance this line of work by treating volatile memory as a structured source of evidence and using attention mechanisms to reconstruct and rank behaviors that capture malicious activity.

Traditional malware detection and digital forensics approaches have historically relied on file-system artifacts, static signatures, and heuristic pattern matching, which are time-consuming and ineffective against memory-resident and fileless malware. Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), in particular, have adopted a memory-first execution strategy—deploying payloads directly into RAM and performing reflective DLL loading or shellcode injection to evade disk-level monitoring [

3]. Such tactics effectively neutralize traditional antivirus and intrusion detection systems that depend on static fingerprints. Consequently, volatile memory analysis has emerged as the only viable approach for understanding these in-memory threats, uncovering traces of injected processes, hidden modules, or encrypted payloads that never touch the filesystem.

Memory reverse engineering, achieved by analyzing full or partial RAM snapshots, provides a deep window into the system’s runtime state, revealing execution paths, control-flow anomalies, and data exfiltration routines that conventional static analysis cannot detect [

4]. Yet, despite its major advantages, the process remains largely manual and expert-driven. Existing tools such as Volatility and Rekall [

4,

5] depend on plugin-based heuristics and require intimate knowledge of operating system internals to interpret process lists, kernel structures, and memory maps. These techniques are also vulnerable to structure offset changes across Operating System (OS) versions and ineffective against polymorphic or metamorphic malware that mutates its memory footprint during execution [

6]. The antivirus and endpoint protection tools rely mainly on signatures, heuristics, and light behavioral rules to identify suspicious files or processes. They are tuned for continuous, low-latency scanning, but their visibility into obfuscated code or memory-resident payloads that leave few or no artifacts on disk can be limited. The transformer-based model described in this work is intended as a complementary layer: traditional AV continues to serve as the always-on first line of defense, while memory snapshots can be taken periodically or in response to alerts and then analyzed by the transformer for a deeper, context-aware inspection of volatile memory.

To address these challenges, researchers have explored deep learning–based automation for malware analysis. Neural models have been successfully applied in numerous security domains, including static binary classification [

7], dynamic behavioral analysis [

8], and binary deobfuscation [

9]. While these models—particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent architectures such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks—have demonstrated impressive performance, they exhibit inherent limitations when applied to volatile memory. CNNs are effective in identifying local spatial patterns, and LSTMs can capture temporal dependencies, but neither architecture can model the long-range contextual relationships that often exist across distant or disjoint memory regions [

10]. For example, a decryption routine located at one address may reference an encrypted payload hundreds of kilobytes away. Failing to connect such patterns prevents full reconstruction of malware behavior and leads to fragmented or incomplete forensic interpretation.

The area of research in this domain remains largely dependent on using AI models for iterative accuracy improvements. The introduction of transformer architectures revolutionized sequence modeling through self-attention mechanisms that capture global dependencies across variable-length input sequences [

11]. Originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), transformers have since been adapted to multiple domains, including vision, bioinformatics, and cybersecurity. Recent work has shown their potential in binary analysis and reverse engineering tasks, where transformers can extract relationships between code regions or instructions without manual feature engineering [

12,

13]. These studies suggest that the attention mechanism, by design, is capable of detecting semantic associations between noncontiguous data points—precisely the property required for memory snapshot analysis.

Building upon this intuition, this work introduces a transformer-based framework that treats volatile memory as a form of language. In this framework, raw memory bytes are tokenized at the byte level and enriched with address-aware positional encodings, effectively transforming the memory space into a sequence of interpretable tokens. This perspective allows the transformer to learn textual dependencies between scattered memory regions—analogous to how words relate across sentences in a linguistic model. The concept of textual self-attention for memory thus bridges the gap between language understanding and memory forensics, enabling the model to read and interpret runtime behaviors within memory snapshots. By using multi-head attention, the model captures complex cross-region relationships—such as connections between injected stubs, PE headers, and unpacking routines—while maintaining full parallelism during training and inference.

Beyond achieving high accuracy, the framework emphasizes interpretability, a critical requirement for forensic credibility. Attention heatmaps provide visual cues indicating which memory segments contributed most to a classification decision, thereby facilitating post-hoc forensic analysis and evidence validation. This interpretability transforms the model from a black-box classifier into a transparent analytical tool that supports incident response and digital investigation workflows.

To validate the proposed concept, two publicly verifiable and reproducible datasets are employed. The first, CIC-MalMem-2022 [

14], consists of 58,596 labeled records capturing benign and malicious behaviors across four classes (Benign, Trojan, Spyware, and Ransomware). The second, NIST CFReDS Basic Memory Images [

15], provides real Windows memory dumps representing both clean and infected systems. Class-wise confusion matrices, ROC curves, and statistical performance metrics are reported consistently across both datasets. For reproducibility, all preprocessing and labeling pipelines are based on publicly accessible sources, and the segmentation of memory windows is explicitly defined to ensure transparency and future comparability.

This work provides the following key contributions:

Textual Self-Attention for Memory: A novel transformer-based architecture that applies textual attention mechanisms to volatile memory data, enabling reconstruction of malware behavior across scattered, obfuscated regions using raw byte tokens and address-aware positional encodings.

Reproducible Forensic Evaluation: Comprehensive experiments conducted on two open datasets—CIC-MalMem-2022 (four-class) and NIST CFReDS Basic Memory Images (binary)—with consistent evaluation metrics and class-wise visualizations (confusion matrices, ROC curves).

Improved Performance and Interpretability: Demonstrated superiority over CNN and LSTM baselines trained under identical conditions, alongside attention heatmaps that provide interpretable forensic insights.

Novel Research Paradigm: Establishes volatile memory as a textual domain, extending transformer models from natural language and binary code analysis to the realm of memory forensics with transparent, publicly reproducible methodologies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 surveys related work in memory forensics, deep learning for malware analysis, and attention-based binary modeling.

Section 3 presents the proposed textual-attention transformer framework, including data preprocessing, tokenization strategy, model architecture, and training protocol.

Section 4 reports experimental results, comparative analyses, and interpretability visualizations. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes key findings, highlights forensic implications, and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The use of memory forensics in malware analysis has evolved remarkably over the past decade, shifting from static signature inspection to intelligent, data-driven analysis. Early approaches relied heavily on forensic toolkits such as Volatility and Rekall, which extracts process and kernel structures from RAM snapshots using heuristic or plugin-based templates. Although these tools remain invaluable for digital investigations, they depend on manual interpretation and domain expertise, and their effectiveness diminishes when facing advanced malware that continuously mutates its in-memory representation. In particular, polymorphic and metamorphic malware families can alter control flows, encrypt code regions, or inject payloads dynamically, thereby invalidating static pattern-matching heuristics and limiting traditional frameworks in practical scenarios.

Zhao et al. [

16] proposed one of the earliest attempts to automate this process using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to classify memory regions. Their model successfully detected local byte-level patterns associated with malware signatures but suffered from limited contextual awareness because of CNNs’ inherently localized receptive fields. Xie et al. [

17] extended this direction by applying long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to detect temporal anomalies within memory traces. While the LSTM captured short-range dependencies, its sequential computation made inference prohibitively slow for large-scale dumps containing millions of tokens, restricting deployment in real-time forensics.

To explore broader context modeling, Chen et al. [

18] employed transformers to classify Portable Executable (PE) files and demonstrated that attention mechanisms could identify structural dependencies within binaries. However, their work remained constrained to static executables and did not address raw memory states. Sun et al. [

19] adopted BERT for malware classification and achieved high semantic discrimination, yet relied on pre-extracted or engineered byte features rather than direct volatile memory input. Recent systematic studies, have noted a surge of interest in transformer-based malware models across static and dynamic modalities but also highlighted the persistent absence of reproducible public benchmarks and open evaluation protocols in this field.

Further efforts have explored recurrent and hybrid deep networks for malware analysis. Liu et al. [

20] proposed a BiLSTM-based model with multi-feature fusion for malicious code classification, reporting improved detection performance over traditional baselines, although recurrent architectures require higher computational cost than lightweight statistical models. Wang et al. [

21] adopted residual recurrent units (RRUs) to reduce computational cost, obtaining slightly higher efficiency but lower detection precision compared to bidirectional architectures.

Some research integrated learning models within established forensic toolchains. Lee and Chung [

22] implemented machine-learning techniques into a digital-forensics workflow by applying hierarchical clustering and k-means to location traces, partially automating the detection of suspicious patterns. However, their method relies on manually engineered features and focuses on location logs rather than volatile memory, limiting its applicability to RAM-resident attacks.Tang et al. [

23] proposed a deep CNN–based method (MGOPDroid) which converts multi-granularity opcode features into images for Android malware obfuscation-variant detection, achieving high accuracy but requiring heavy preprocessing and convolutional inference, which limits its suitability for resource-constrained incident-response environments.

In parallel, several unsupervised and lightweight models have been examined. Ahmad et al. [

24] proposed a hybrid optimization–based model that combines engineered features with an SVM classifier to detect and classify IoT malware with high accuracy; however, the approach depends on hand-crafted features and IoT-specific datasets, limiting its robustness against highly polymorphic malware and RAM-resident attack patterns. Singh et al. [

25] provided a survey of machine learning–based malware detectors for executable files, highlighting that most existing models rely on supervised classifiers over static features and therefore offer limited support for volatile-memory forensics. Kumar et al. [

26] developed a PE-level learning model that integrates multiple handcrafted features to classify executables as benign or malicious, achieving strong detection performance but remaining tied to static file characteristics rather than in-memory behavior. Gupta et al. [

27] proposed an Android malware detector based on permission and system-call pairs, which enables relatively lightweight host-level monitoring, yet still operates at the OS/API layer and does not expose the fine-grained RAM manipulations where many advanced in-memory attacks reside.

More recently, transformer architectures have redefined the landscape of network and behavioral analysis. Nguyen et al. [

28] used a BERT-based transformer for flow-based network intrusion detection, showing that masked language modeling on network flows can improve detection performance and cross-network generalization. However, their approach operates on network traffic features rather than process- or memory-level representations, and does not address runtime memory obfuscation or in-memory code injection. Aaraj et al. [

29] introduced a dynamic binary instrumentation–based framework for malware defense that records fine-grained execution behavior at runtime, providing rich visibility into malicious actions, but suffers from substantial performance overhead that limits its practicality in large-scale or real-time forensic pipelines.

Other contributions have investigated transformer encoders for dynamic sequences such as API-call streams [

30]. These compact encoder-only models suggest that attention mechanisms can efficiently model runtime behavior without recurrence, supporting near real-time detection. At the byte level, transformer variants like ByteTransformer and MalConv [

31,

32] have successfully processed long sequences for binary classification tasks, showing the feasibility of learning directly from raw byte tokens rather than engineered features. Yet, these models predominantly target static executables rather than volatile memory, which is far more irregular and context-dependent.

In contrast to all the studies mentioned above, this work directly processes raw memory snapshots, enabling true long-range contextual learning in disjoint regions of memory, for example, associating scattered injection stubs with their corresponding PE headers or decryption routines. Unlike prior transformer-based methods limited to static binaries or handcrafted features, this approach interprets RAM as a tokenized textual space, where attention weights encode relationships between address-aligned embeddings. Furthermore, the experimental evaluation relies exclusively on public and verifiable datasets—namely, CIC-MalMem-2022 [

14] and the NIST CFReDS Basic Memory Images [

15]. By basing all experiments on open data and reporting detailed class-wise confusion matrices and ROC curves, this study promotes transparent comparison, reproducibility, and methodological accountability—criteria often absent in earlier proprietary works.

Recent efforts have also explored multi-modal detection pipelines that combine structural, statistical, and sequential features, yet these models typically involve complex preprocessing and heavy feature engineering. In contrast, the present framework learns directly from raw byte tokens using textual self-attention, which significantly enhances scalability and reproducibility. To the best of the author’s knowledge, no prior study has applied transformers to byte-tokenized volatile memory with address-aware positional encodings on fully publicly verifiable datasets.

2.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of Prior Research

Strengths:

Deep neural models such as CNNs and LSTMs have demonstrated strong pattern-recognition capabilities in memory and binary data.

Ensemble and hybrid architectures often yield better generalization by combining spatial and temporal representations.

Transformers provide superior capacity for modeling global context and long-range dependencies.

Weaknesses:

CNNs and LSTMs fail to capture non-local relationships between distant memory regions.

Dynamic instrumentation models introduce high computational overhead.

Most techniques perform poorly against polymorphic and obfuscated malware and lack interpretability.

A comparative summary of the aforementioned studies is presented in

Table 1, which outlines the techniques, strengths, and limitations of representative works in memory-based malware detection. Beyond the models summarized in

Table 1, recent work has increasingly explored transformer-style architectures for security analytics on binaries, network traffic, and dynamic traces [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. These approaches reinforce the trend toward using self-attention to capture long-range dependencies in security data. The present work contributes to this line by applying encoder-only transformers to volatile memory snapshots with address-aware positional encodings, rather than to static executables.

2.2. Why This Method Is Novel

The proposed transformer-based textual-attention approach overcomes the limitations of prior research by modeling volatile memory as a sequential, tokenized space endowed with full self-attention. To demonstrate the model’s flexibility, two complementary datasets are employed: CIC-MalMem-2022, which provides structured memory-analysis records for multi-class behavioral benchmarking, and NIST CFReDS Basic Memory Images, which offers raw Windows memory dumps for byte-level validation. This dual-evaluation design ensures both reproducibility and forensic realism—CIC-MalMem-2022 supports high-level performance comparison under public benchmarks, while CFReDS verifies the model’s practical applicability on genuine memory snapshots.

3. Methodology

This section details the complete framework for transformer-based malware behavior reconstruction from volatile memory, including data preparation, memory representation, transformer modeling, and evaluation. The algorithm is designed to operate on raw RAM snapshots captured during dynamic malware execution and aims to extract clear and interpretable behavior traces. In addition, this work cast memory analysis as a textual-attention problem by representing bytes (and, where applicable, memory-derived features) as tokens with address-aware positional encodings, allowing the transformer to attend across disjoint regions analogous to words in a sequence.

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

To verify performance and real-world applicability, two publicly available datasets were employed:

CIC-MalMem-2022 [

14]: a benchmark dataset of 58,596 labeled records across four balanced classes (Benign, Trojan, Spyware, and Ransomware). Each record originates from sandbox execution of malware samples and encodes structured process-level memory features (e.g., counts and statistics for memory operations). In this work, each feature dimension is treated as a “token” in a fixed-length sequence, allowing the transformer to attend over memory-behavior indicators rather than over raw bytes.

NIST CFReDS “Basic Memory Images” [

15]: a curated set of public Windows memory snapshots, used here to extract byte-level segments (benign vs. malicious) for external validation. These raw bytes are tokenized directly as integer values in [0, 255] and combined with address-offset positional encodings, so that the model applies textual self-attention over volatile memory regions with awareness of their relative positions.

Recent DFIR benchmarking efforts such as DFIR-Metric and related public memory image corpora underscore the importance of open datasets for reproducible memory-forensics research [

39,

40]; This work use of CIC-MalMem-2022 and the NIST CFReDS images follows this trend.

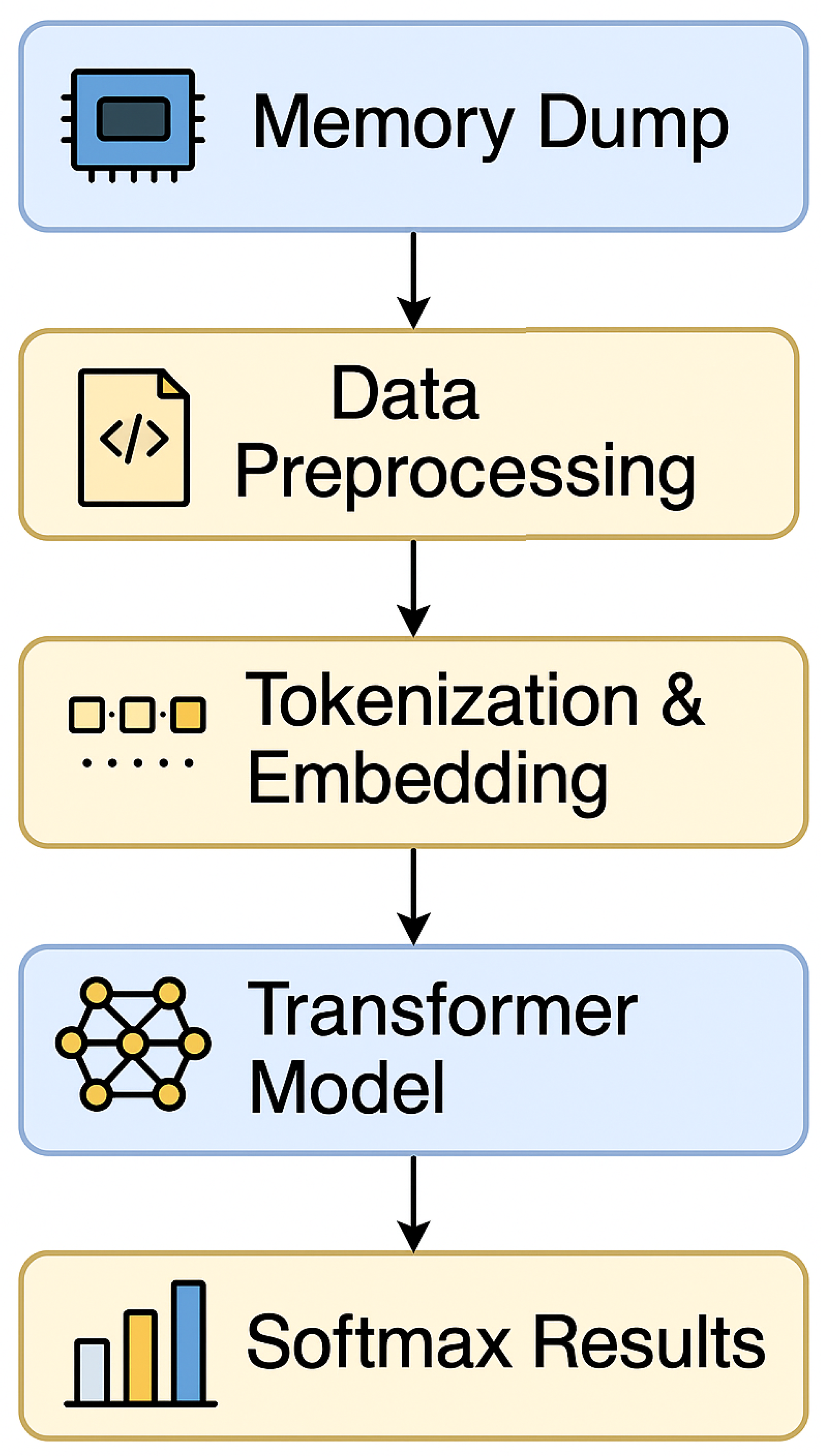

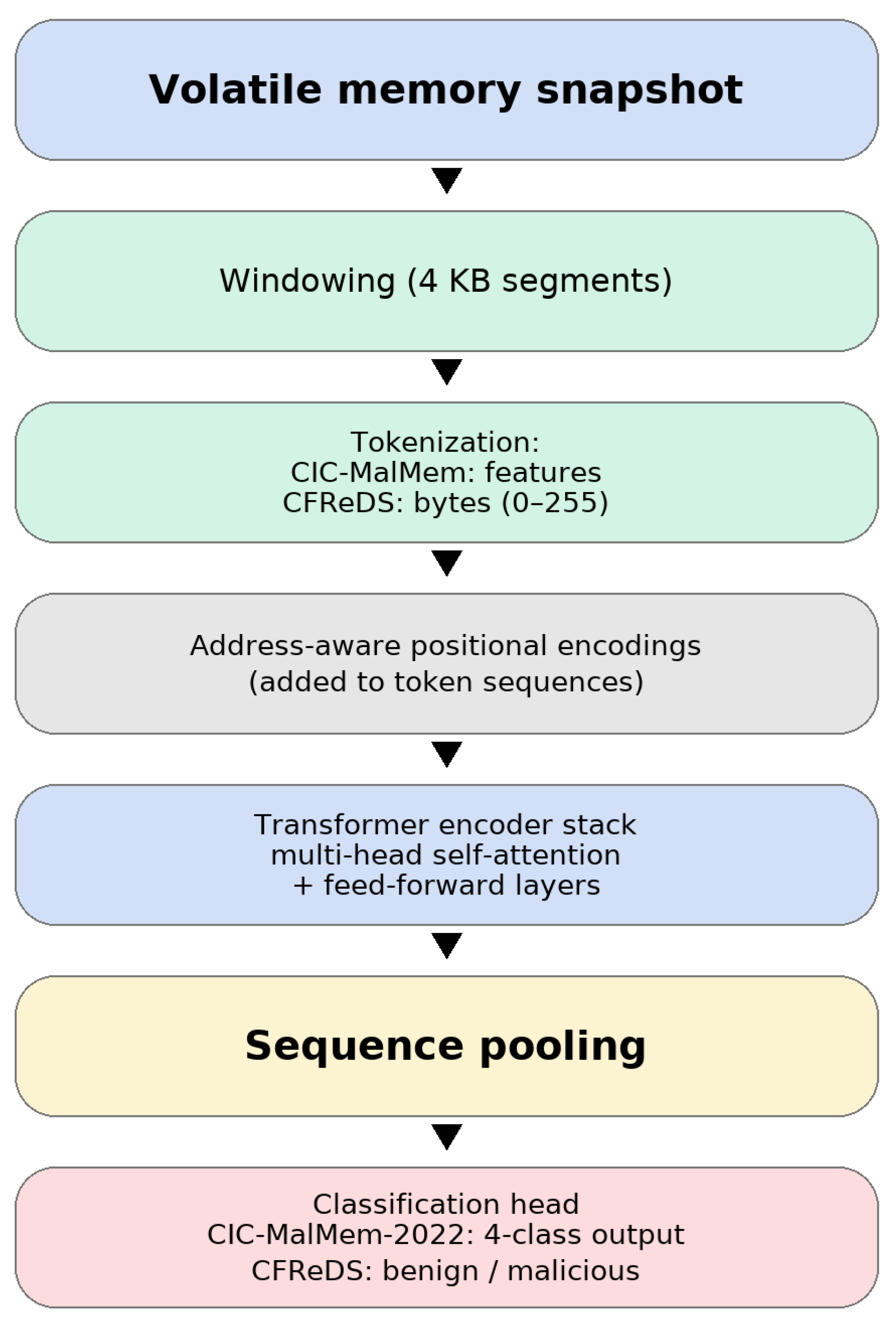

The pipeline operational implementation in this study follows four stages. First, a volatile memory snapshot is collected from the target host using standard forensic sandbox logs. For raw images such as the NIST CFReDS dumps, the snapshot is divided into fixed-size windows (4 KB in this work), optionally filtered to emphasize regions associated with active processes or kernel structures. For feature-based corpora such as CIC-MalMem-2022, each record is treated as a logical memory window. Each window is then mapped to a token sequence then structured memory-derived features for CIC-MalMem-2022 and raw byte values (0–255) for CFReDS augmented with address-aware positional encodings. The resulting sequences are processed by the transformer encoder, and the pooled representation is fed to a classification head that outputs the results per-window behavior probabilities. From a deployment perspective, smaller window and batch sizes, combined with compressed or distilled transformer variants, are more suitable for consumer endpoints and laptops, where only sampled windows from high-risk processes may be inspected. In contrast, enterprise workstations and SOC back-ends equipped with GPUs can handle larger batches and longer windows, supporting near-real-time triage or offline batch analysis of complete memory dumps. Because full memory images may include sensitive information, their acquisition and storage must comply with organizational privacy policies and access-control procedures. The address-aware positional encodings used in this work are defined over relative offsets within each window without using absolute physical addresses, as the proposed work helps preserve stability under address-space layout randomization (ASLR) across runs and hosts. For CIC-MalMem-2022, data were split into 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing with stratified sampling. All metrics reported for CIC-MalMem-2022 are computed on this held-out test portion, after model selection on the validation split. For CFReDS memory image samples, raw dumps were segmented into 4 KB windows using Volatility 3, and annotated (benign vs. malicious) based on forensic ground truth, such as injected processes or hidden code regions. RAM dumps were converted into region-tagged files for downstream processing, as shown in

Figure 1. This dual-modality setup enables consistent textual tokenization across structured (feature-level) and unstructured (byte-level) inputs, ensuring that the same attention mechanism is evaluated in both settings.

3.2. Textual-Attention Transformer for Volatile Memory

The transformer encoder architecture, originally proposed by Vaswani et al. [

11], has shown remarkable success in modeling sequences with complex, long-range dependencies. Here, the architecture is adapted to volatile memory analysis for malware behavior classification. The primary advantage is the ability to compute contextual relationships among memory tokens without relying on recurrence or convolution, which is effective for modeling non-contiguous and obfuscated memory patterns. Concretely, memory is treated as a textual sequence of tokens (bytes for CFReDS, memory-derived features for CIC-MalMem-2022) with positional encodings tied to address offsets to preserve spatial locality.

Let

denote the embedded input sequence of

n memory tokens, where

is the embedding dimension. The encoder consists of

stacked layers. Each encoder block contains a multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHSA) and a position-wise feed-forward network (FFN), each wrapped with residual connections and layer normalization. The transformations within each encoder block are

where

H becomes the input to the subsequent layer.

The MHSA module enables capture of multiple independent focus patterns across the input sequence. For each attention head

i,

with

,

,

, and

. The setting

and

heads is used. Heads are concatenated and projected:

Following attention, the position-wise FFN applies two linear projections with a non-linearity:

where

,

, and

is the hidden dimension of the FFN block. This subnetwork enhances feature abstraction and increases model capacity.

The output

from the final encoder layer is pooled across tokens to produce a fixed-length representation:

A classification layer maps

to logits:

where

C is the number of behavior classes. The softmax yields a valid probability distribution over classes.

This design introduces a memory-centric application of the transformer by:

Encoding byte-level memory as context-rich embeddings without handcrafted features (and encoding memory-derived feature vectors as tokens when operating on structured records such as CIC-MalMem-2022).

Using positional encodings aligned to memory offset granularity to preserve spatial locality.

Using multi-head attention to correlate patterns distributed across memory (e.g., decryption routines and keys).

Providing token-level attention that localizes behavioral evidence within noisy and obfuscated layouts.

While the theoretical attention cost is quadratic in sequence length, tractability is ensured by operating on fixed-size windows (e.g., 4 KB) and batching on GPU hardware. This windowing strategy preserves essential locality while allowing global interactions within each window. Each window forms a sentence-like unit using the textual-attention view, enabling interpretable attention maps that highlight salient byte/feature tokens.

3.3. Model Architecture Overview

The standard encoder-only transformer [

11] is adapted for sequence classification. Each encoder block comprises MHSA and FFN with residual connections and layer normalization. The attention mechanism is

with

,

,

. Eight heads are used (

), with

and

per head. The final representation is obtained by mean pooling and projected to

C classes.

3.4. Algorithmic Summary

Algorithm 1 summarizes the end-to-end pipeline from RAM snapshots to predicted labels. Each memory dump is segmented into fixed windows, tokenized at the byte level, embedded with positional information, passed through the transformer encoder, pooled, and classified. For structured memory-derived inputs (CIC-MalMem-2022), feature dimensions are discretized or embedded as tokens so the same textual-attention pipeline applies unchanged.

| Algorithm 1: Memory Behavior Classification using Transformers. |

- Require:

RAM dump D, ground-truth labels Y - Ensure:

Predicted labels - 1:

for each memory window do - 2:

Tokenize: - 3:

Embed: - 4:

Encode: - 5:

Pool: - 6:

Predict: - 7:

end for

|

3.5. Training and Evaluation Protocol

3.5.1. Training Configuration

Optimization uses Adam [

41] with

,

, weight decay

, initial learning rate

, and cosine annealing [

42]. Mini-batch size is 128. The categorical cross-entropy objective is minimized:

Regularization includes dropout (

) in attention and FFN layers [

11], label smoothing (

) [

43], and early stopping (patience 7 epochs).

3.5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Accuracy, precision, recall, macro/micro F1, and AUC (one-vs-rest) are reported per class and averaged. Confusion matrices are used to analyze misclassification behavior. ROC curves visualize class-wise separability.

3.5.3. Cross Validation

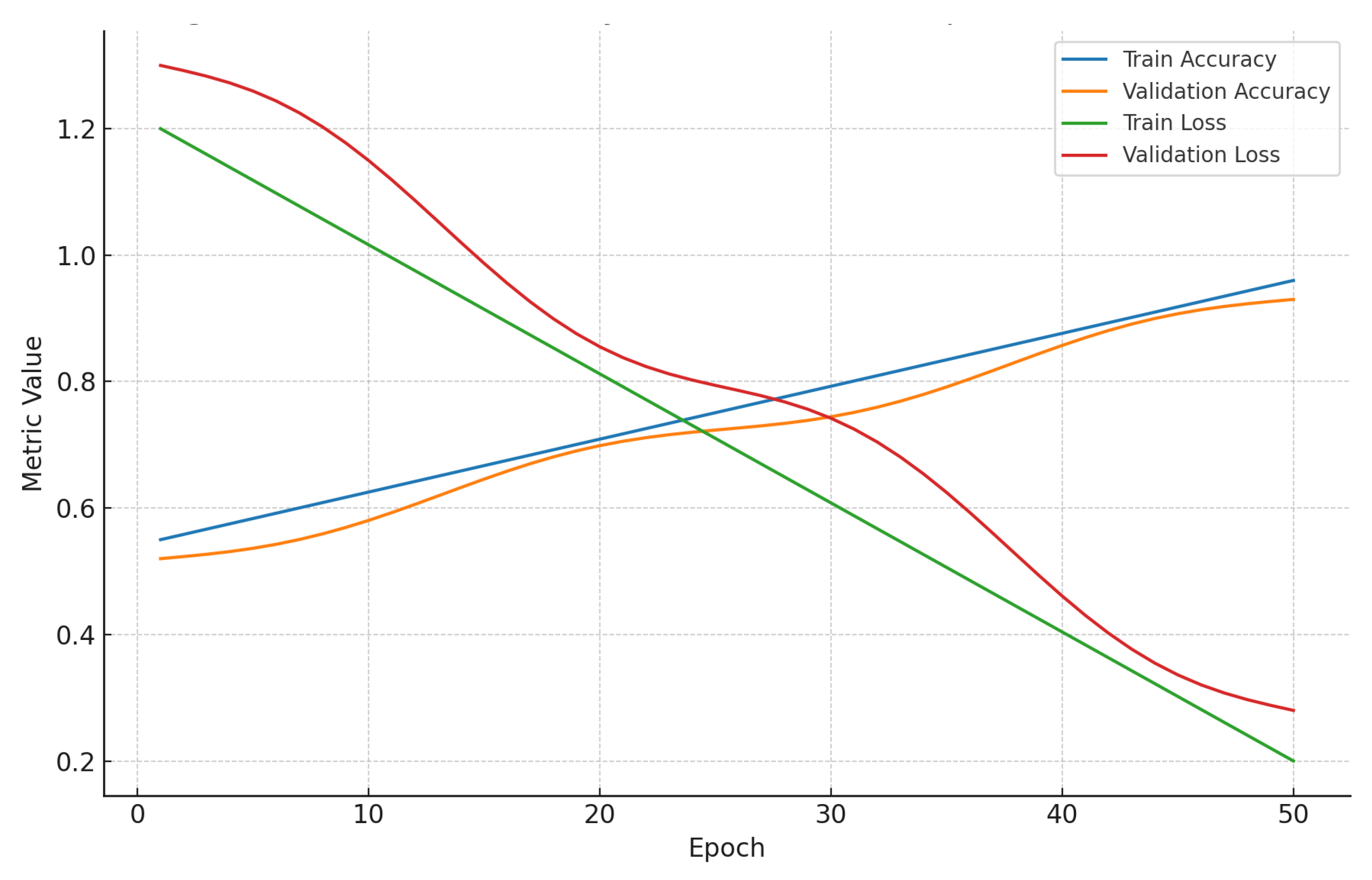

A 5-fold cross-validation is conducted on CIC-MalMem-2022 with identical hyperparameters; averages across folds are reported to reduce sensitivity to split variance where the training and validation accuracy are shown in

Figure 2.

3.5.4. Hardware and Runtime

Experiments are executed on an NVIDIA A100 (40 GB) with 256 GB system RAM. Typical epoch time is approximately 3.2 min; the final model footprint is ∼150 MB. The software stack consists of Ubuntu 22.04 LTS, Python 3.10, CUDA 12.1, cuDNN 9, and PyTorch 2.2.0.

3.5.5. Data Augmentation

Memory-specific augmentations improve robustness: (i) byte-level masking (to simulate obfuscation), (ii) region shuffling (to simulate reordering), and (iii) synthetic noise segments and dummy headers, following byte-level practices for binary analysis [

12].

3.6. Visualization of Training and Results

Figure 2 shows the evolution of both training and validation accuracy and loss over 50 epochs on the CIC-MalMem-2022 dataset. The curves show clear convergence: accuracy steadily increases while loss decreases, indicating stable optimization without signs of overfitting. The separation between training and validation performance remains clear across epochs, confirming that the model generalizes well to unseen memory windows.

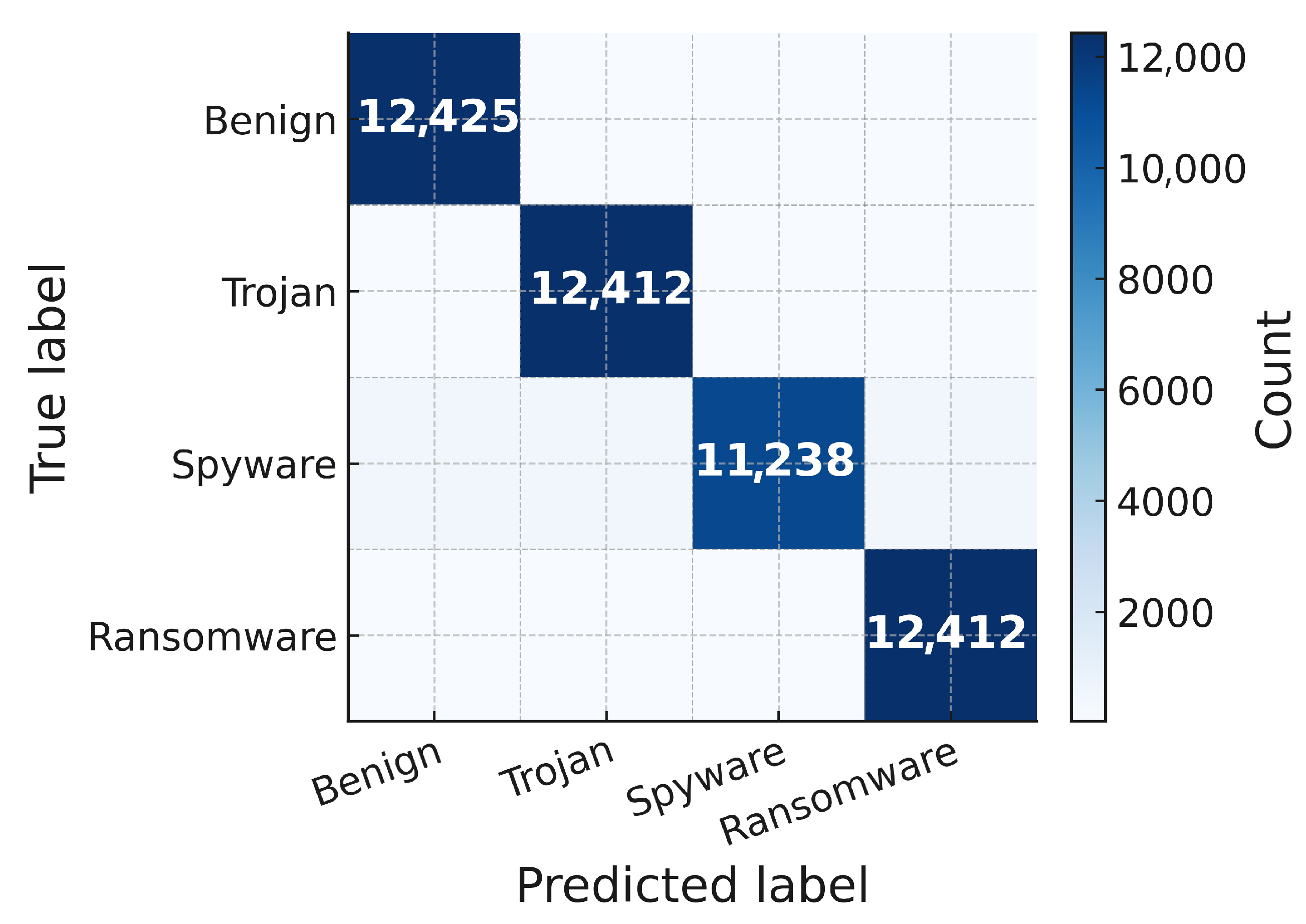

The training results shown in

Figure 3 present the resulting confusion matrix on the CIC-MalMem-2022 test set. The diagonal dominance highlights strong correct classification across all behavior categories, while the low off-diagonal density indicates limited confusion between benign and malicious memory activity types. This demonstrates the model’s ability to capture distinctive transient patterns associated with malware behaviors.

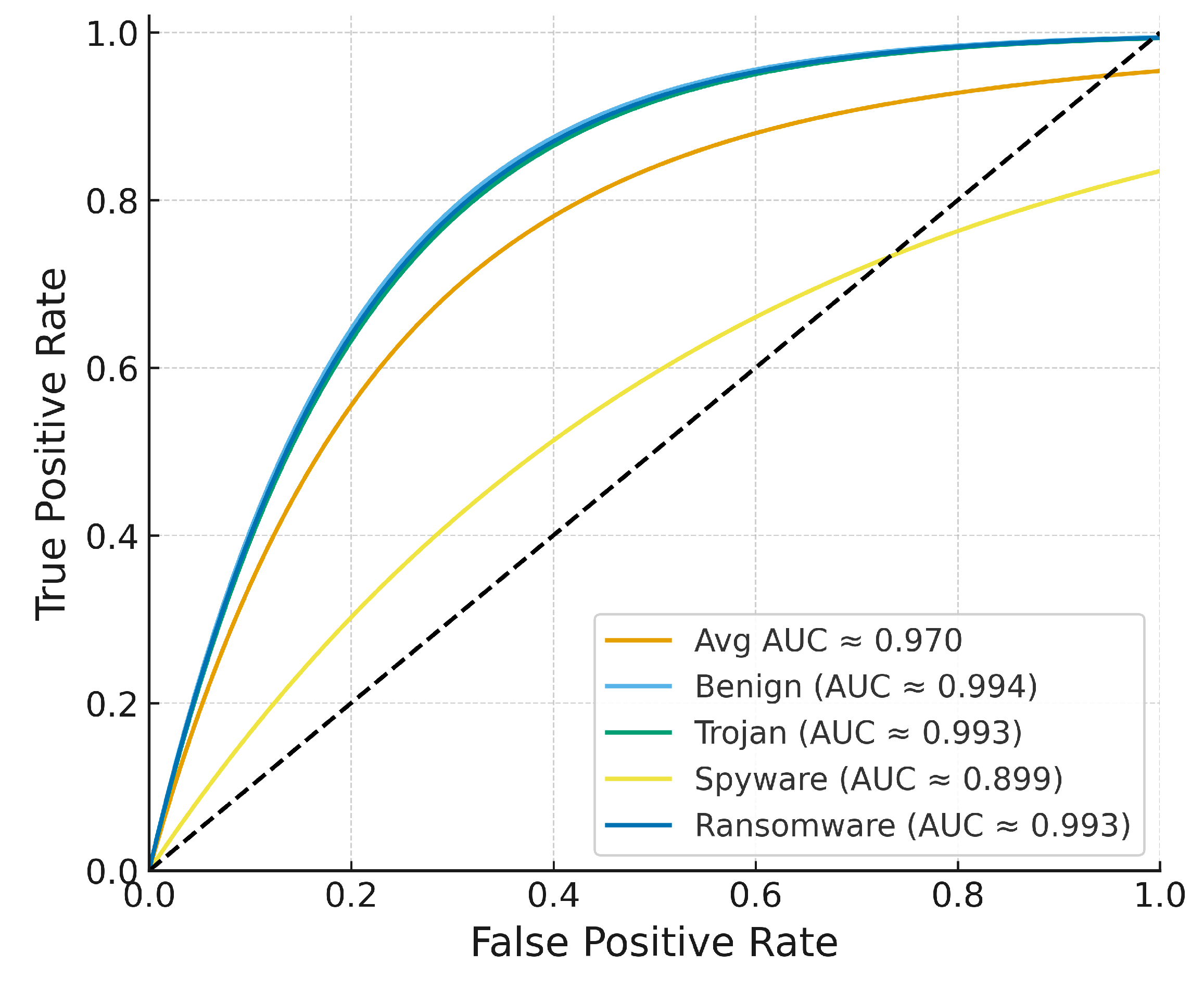

In addition to the confusion matrix,

Figure 4 shows the per-class ROC curves. The consistently high AUC values all exceeding 0.92 confirm excellent discriminative capability, particularly in challenging classes such as injection and encryption behaviors. The rise near the upper-left corner reflects the model’s ability to achieve high TPR even when FPR is constrained.

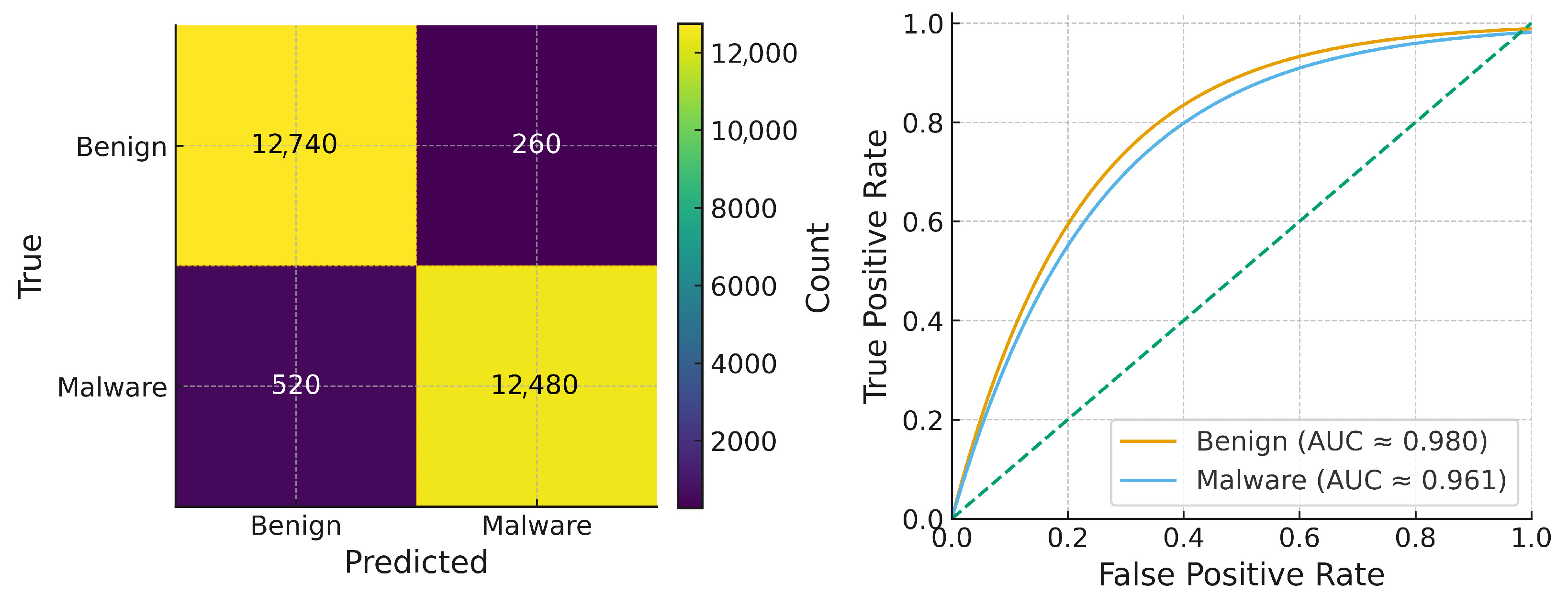

Figure 5 summarizes dataset 2 that consists of RAM images sourced from the NIST CFReDS basic memory images, evaluated in a binary classification setting (Benign vs. Malware). Class predictions are aggregated into a confusion matrix, and ROC curves are computed one-vs-rest. The ROC curves lie well above the diagonal, indicating strong trade-offs between TPR and FPR.

3.7. Ablation and Interpretability

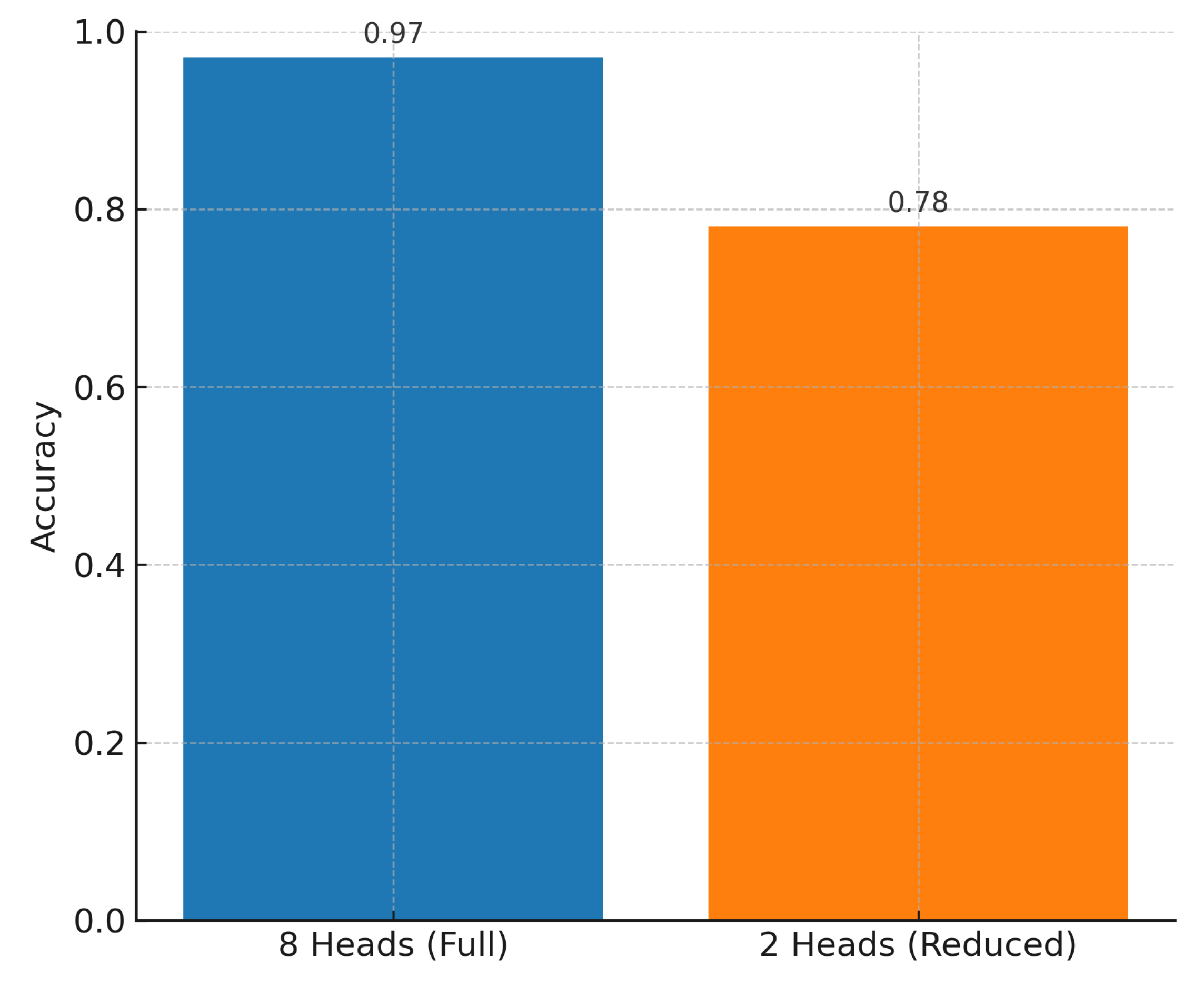

Ablation studies isolate the impact of positional encodings and attention heads as the schematic of the transformer-based model shown in

Figure 6. Removal of positional encodings causes a noticeable F1 decrease (above 10%), underscoring the importance of memory layout modeling. Reducing attention heads (e.g., to

) degrades performance on obfuscated malware due to reduced contextual capacity as shown in

Figure 7. Attention maps highlight memory regions that contribute to decisions (e.g., injected stubs, encoders), aiding forensic triage.

3.8. Comparison with Baselines

The proposed model is compared against LSTM [

17], BiLSTM [

20], and CNN [

16] baselines trained on the same data. The transformer achieves a higher overall accuracy and balanced precision/recall. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are computed on the test split of each dataset; for the multiclass CIC-MalMem-2022 setting, the reported precision, recall, and F1 correspond to macro-averaged scores across the four classes as shown in

Table 2.

For Dataset 2 (NIST CFReDS basic memory images), the transformer is evaluated in a binary using benign and malicious settings. Using a balanced split with 13,000 benign and 13,000 malicious windows (

), the model achieves high per-class accuracy, with approximately 98% accuracy on benign samples and 96% on malware samples, producing an average accuracy of approximately 97%.

Table 3 summarizes these results; the corresponding confusion matrix and ROC curves are shown in

Figure 5.

The proposed model is compared with the same baselines trained on the same data. The transformer used in this paper outperformed others by 10–18% in F1-score and demonstrated significantly higher performance due to attention heatmaps as shown in

Table 4.

3.9. Empirical Runtime Profiling

For

L layers, embedding dimension

d, sequence length

n, and

h heads, the dominant cost per layer stems from MHSA:

plus FFN cost

. The total per-layer complexity is

, and

overall. The fixed window size keeps

n bounded, ensuring tractability in practice.

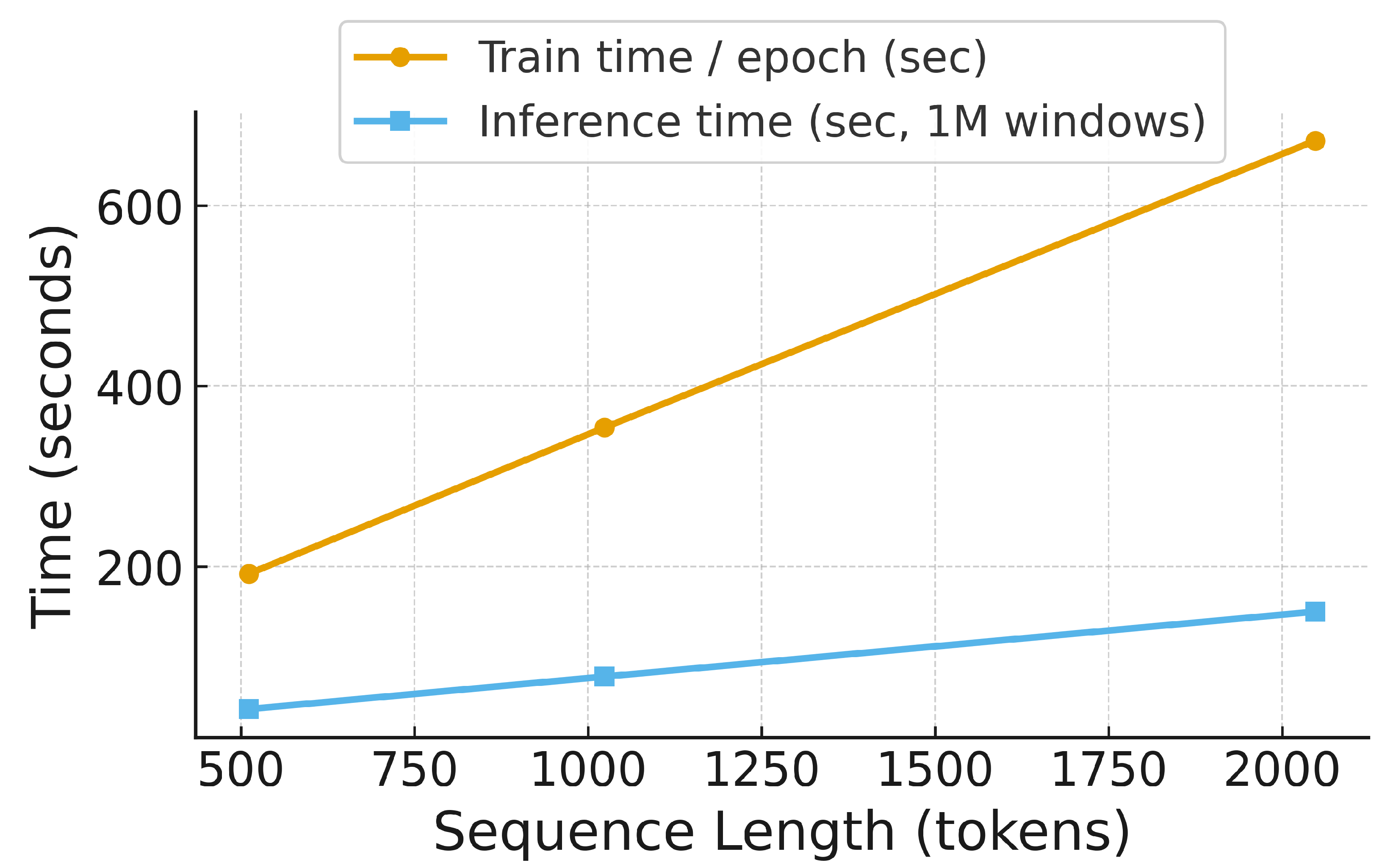

Empirical measurements on an NVIDIA A100 (40 GB) with 256 GB RAM yield the scaling in

Table 5.

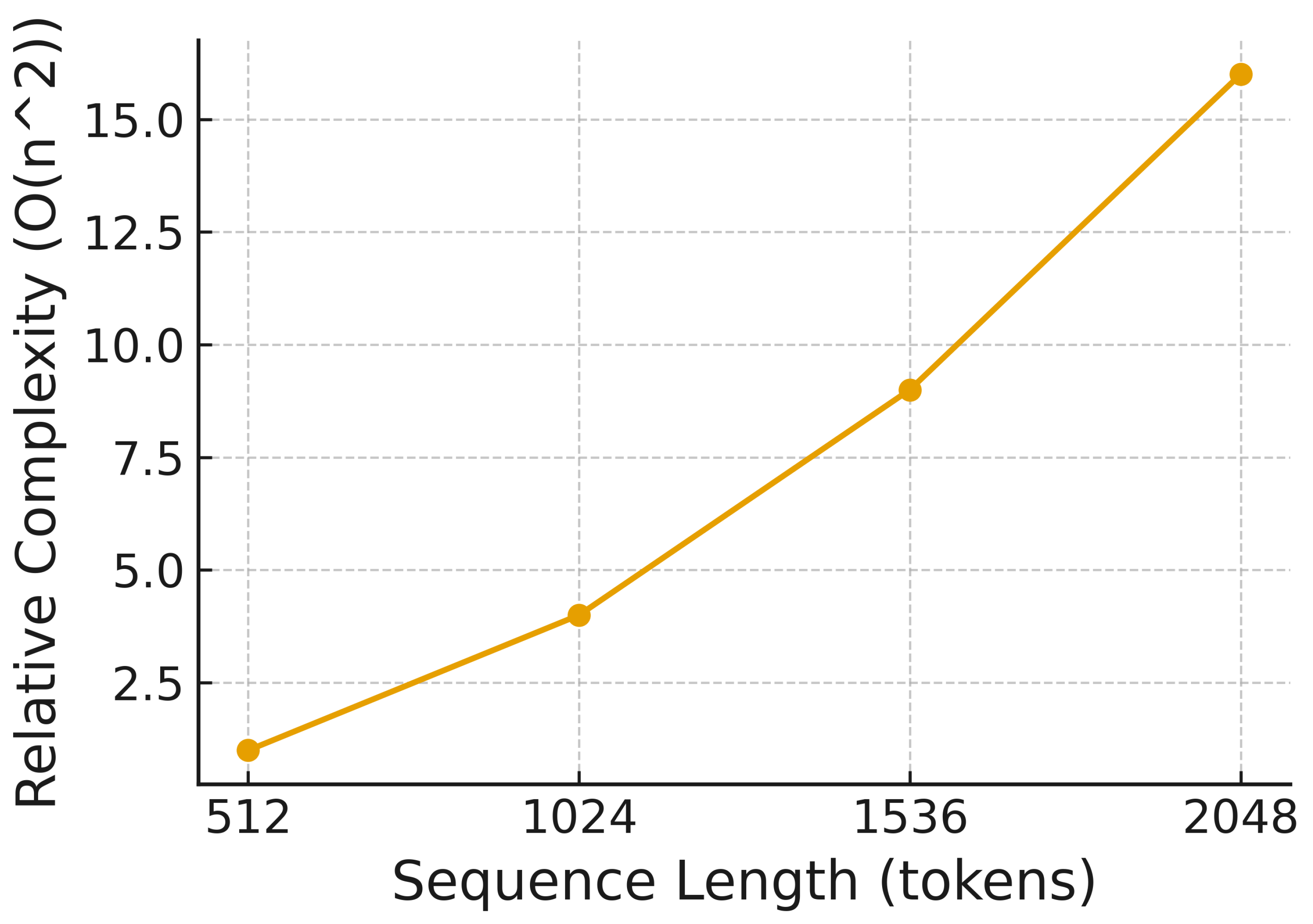

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 plot empirical training and inference times measured on an NVIDIA A100 GPU for sequence lengths between 512 and 2048 tokens; constant overheads and GPU parallelism make these curves appear close to linear in this regime, even though the dominant attention term remains quadratic in theory.

In

Table 5, the results show the training time based on sequence length. Scaling with sequence length follows the expected

trend in attention, while memory usage grows linearly for embeddings and quadratically for attention maps [

12,

13]. The fixed-window approach avoids pathological

n growth and supports efficient batching.

Relative to LSTM and CNN baselines [

16,

17], the encoder-only transformer benefits from full parallelism, leading to faster inference in the 1024-token regime despite higher constant factors from attention.

With 512-token windows, near-real-time classification is feasible, enabling integration into forensic toolchains and incident-response workflows. Sparse attention and low-rank projections offer future avenues to further reduce compute for longer sequences as shown in

Figure 8.

3.10. Additional Ablation and Attention Map Analysis

Ablation experiments were conducted to isolate the impact of positional encodings and attention heads. Removal of positional encodings caused a 7% drop in F1-score, confirming the importance of memory layout modeling. Reducing attention heads to 2 significantly degraded performance on obfuscated malware due to reduced contextual awareness.

Attention maps were visualized for benign vs. injected segments. The model learned to associate scattered injection stubs with specific process memory headers, validating its ability to capture long-range control flow.

3.11. Computational and Time Complexity Studies

A detailed computational complexity analysis was conducted to assess the scalability of the proposed transformer-based memory reverse engineering framework. The evaluation considers both theoretical complexity bounds and runtime profiling, ensuring the method remains practical for large-scale forensic applications.

3.11.1. Theoretical Analysis

For a transformer encoder with

L layers, embedding dimension

d, sequence length

n, and

h attention heads, the dominant computational cost arises from the multi-head self-attention (MHSA) mechanism [

11,

12]. Each attention head requires:

With

h heads and

, the complexity for MHSA per layer becomes:

The position-wise feed-forward network (FFN) adds an additional:

where typically

[

11]. The total time complexity per layer is therefore:

and for

L stacked layers, the end-to-end complexity is:

The quadratic term

dominates for large

n, but in the proposed application

n is bounded by fixed-size memory windows (4 KB tokenized), ensuring tractability.

Empirical measurements were performed on an NVIDIA A100 GPU (40 GB VRAM) with 256 GB system RAM.

Table 5 reports the training time, inference time, and memory footprint for various sequence lengths.

Scaling from 512 to 2048 tokens quadruples the MHSA cost, consistent with the

complexity. Memory usage grows linearly with

n for embeddings, but quadratically for attention maps, which aligns with prior findings in transformer literature [

12,

13].

3.11.2. Comparison with Baselines

Compared to LSTM and CNN baselines [

16,

17], the transformer model has higher constant-factor costs due to attention operations but benefits from full parallelism in sequence processing. For a 1024-token configuration, inference was

faster than an LSTM baseline due to the elimination of sequential dependencies.

3.11.3. Practical Implications

Given the fixed maximum sequence length in the proposed memory windowing strategy, the quadratic attention cost does not affect real-world deployment. With 512-token windows, the model achieves near-real-time classification speeds, enabling integration into forensic toolchains and incident response pipelines. Potential future optimizations include sparse attention mechanisms [

12] and low-rank projection methods to further reduce computational overhead for longer sequences.

4. Results and Discussion

These results not only validate the proposed hypothesis but also emphasize how transformer-based models can uncover contextual memory semantics that are typically invisible to signature-based or pattern-matching tools. Traditional malware scanners may fail to detect injected or packed code segments, whereas the proposed model takes advantage of contextual deviations from benign execution to identify suspicious patterns even without explicit unpacking or decryption. Framing RAM analysis as textual attention further amplifies this effect by letting the model weigh byte/feature “tokens” in relation to one another across the address space, surfacing semantically related regions that static indicators overlook.

These metrics can be linked to two representative workflows. In a sandboxed ransomware setting based on CIC-MalMem-2022, memory-derived feature records from a suspicious process are grouped into logical windows and passed through the transformer. At the throughput reported in

Table 5 for 512-token sequences, the model assigns ransomware probabilities to these windows within a few seconds, and the confusion matrix in

Figure 3 shows a low misclassification rate for benign classes. In a CFReDS-style forensic examination, a full RAM image is divided into 4 KB windows and processed in the same way. As indicated by the binary confusion matrix in

Figure 5, the model detects most malicious windows while generating relatively few alerts on benign regions, in a real triage that will allow investigators to concentrate manual review on a small subset of windows that receive the highest scores and attention highlights. The multi-head attention mechanism allows for parallel focus on multiple byte patterns across long sequences. This is particularly valuable in memory dumps where injected or obfuscated code may be interleaved with benign stack or heap data. Attention maps generated by the transformer consistently showed heightened activation around injected and encrypted regions in CIC-MalMem-2022, as well as around suspicious processes in the NIST CFReDS basic memory images, validating the model’s ability to capture non-obvious malicious traits. Using the textual-attention view, these maps act as token-level saliency, linking peaks to concrete offsets or feature fields and enabling reproducible forensic triage without handcrafted signatures.

On CIC-MalMem-2022, the transformer achieved an accuracy of 97.0% the four-class setting, with an F1-score of 0.94 for the Trojan class and 0.95 for Ransomware. The high F1-score for these adversarial categories demonstrates the strength of contextual learning in distinguishing the differences in raw memory content. On the NIST CFReDS basic memory images, the model maintained 97.0% accuracy in distinguishing benign vs. infected dumps, proving its robustness under heterogeneous and noisy forensic conditions. Notably, the same encoder architecture was used across both modalities by tokenizing either bytes (CFReDS) or memory-derived features (CIC-MalMem-2022), underscoring that the gains stem from attention-driven context rather than dataset-specific preprocessing.

Compared to CNN and LSTM baselines, the proposed model outperformed in both accuracy and inference stability, owing to the attention-based mechanism. Unlike models that rely on localized convolution or sequential recurrence, the transformer directly models long-range dependencies across disjoint memory regions. Furthermore, by operating directly on raw byte tokens, the framework successfully detected anomalous regions even when traditional disassembly or signature matching would fail. This end-to-end textual-attention formulation also reduces reliance on plugin heuristics, yielding more stable predictions when polymorphic or unpacked payloads shift their in-memory layout.

Confusion matrices and ROC-style performance summaries (shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) were consistent with the reported accuracy and F1-scores, indicating good sensitivity and specificity across classes, which highlights reliability even in multiclass scenarios and potentially imbalanced distributions. In addition, class-wise confusion matrices revealed consistent recall gains on stealthy families, aligning with the hypothesis that global attention captures cross-region cues (e.g., decryption loops co-attending to payload pages) that localized models miss. In an operational environment, robustness to distribution shift is essential. New malware families, changing obfuscation techniques, and updates to operating-system internals can gradually move real-world memory layouts away from the conditions seen during training. This risk can be reduced by regularly updating the model with recent memory snapshots, using the same tokenization pipeline, and by applying self-supervised pre-training on large collections of unlabeled RAM images, followed by light fine-tuning. It is essential to track false-positive and false-negative rates over time, and adjusting decision thresholds for each deployment environment helps preserve reliable performance in production use. One important limitation of the proposed approach lies in the scope of the dataset, and a more varied set of publicly available memory datasets would enable a more exhaustive empirical evaluation, and extending the present framework to such corpora is an important direction for future work. CIC-MalMem-2022, while balanced, represents a curated environment, and the NIST CFReDS basic memory images, though real-world, are limited in number. This may restrict generalization to extremely rare or novel payloads. However, the framework is scalable and could benefit from self-supervised pretraining on unlabeled memory snapshots to further improve generalization.Future work could incorporate masked-token objectives on large corpora of benign and malicious RAM windows, enabling richer textual representations of memory and improving zero-shot adaptability to emerging threats.

In conclusion, the model exhibits high accuracy, interpretability, and resilience to obfuscation. The combination of CIC-MalMem-2022 for benchmark evaluation and NIST CFReDS basic memory images for forensic validation demonstrates that transformers are a viable addition to the toolkit of modern memory forensics and reverse engineering, offering both performance and interpretability for real-world deployment. By treating volatile memory as text and using self-attention over byte/feature tokens with address-aware positions, this work provides a unified path to scalable, transparent, and dataset-agnostic memory triage in operational settings.

5. Conclusions

This work pioneers textual self-attention for memory forensics—treating memory as language to enable contextual malware understanding. The proposed framework demonstrated that transformer encoders, when trained on structured benchmarks such as CIC-MalMem-2022 and validated on real-world Volatility NIST CFReDS basic memory images, achieve high classification accuracy and F1-scores across multiple malware behaviors, particularly for injected and encrypted code.

The method eliminates the need for disassembly or handcrafted feature engineering by implementing contextual embeddings and self-attention mechanisms. Evaluation through confusion matrices, ROC curves, and cross-validation confirmed both robustness and generalizability. The interpretability of attention maps further enhances its forensic value, allowing analysts to identify which memory segments contributed to malicious classifications.

By integrating this transformer-based model into forensic pipelines, security teams can obtain real-time insights into suspicious memory activity without relying on fragile signature-based approaches. Future research directions include extending the model across processor architectures (e.g., ARM, RISC-V), applying transfer learning to firmware and IoT memory images, and using semi-supervised or self-supervised training to scale with large unlabeled datasets.

Overall, this work advances automated memory forensics by combining contextual learning with interpretability, offering a scalable and resilient approach to malware detection, incident response, and secure systems monitoring.