1. Introduction

Digitalization, accompanied by rapid technological advances, has significantly contributed in the education field, fostering the widespread adoption of e-learning systems across various educational levels [

1]. In Early Childhood Education (ECE), digital learning tools have gained traction due to their ability to enhance engagement, facilitate interactive learning, and support cognitive development [

2,

3]. As young learners often rely on visual and non-verbal communication to understand and express emotions, integrating visual elements into digital learning materials has become an area of increasing research interest [

4,

5,

6]. Despite their widespread use in digital communication, a systematic framework for incorporating emojis into ECE materials in a pedagogically meaningful way remains underexplored. Current research in digital learning has largely focused on cognitive engagement strategies such as gamification, adaptive learning, microlearning, and interactive multimedia elements [

7]. These approaches aim to enhance motivation, personalize content, and improve retention through data-driven insights. Gamification techniques, including reward-based systems and progress tracking, have been shown to increase learner motivation, while adaptive learning systems leverage artificial intelligence (AI) to customize educational experiences based on individual performance [

8,

9,

10]. Additionally, the integration of interactive components such as quizzes and animations has contributed to higher engagement levels among learners. However, these methods primarily address cognitive and behavioral aspects of learning, often overlooking the role of emotional and visual stimuli in shaping early learning experiences. Recent studies suggest that integrating sentiment analysis tools into Early Learning Curriculum (ELC) can help estimate the affective tone of instructional text, allowing for support emotion-aware augmentation decisions to improve engagement and motivation [

11,

12]. Yet, research on using visual emotional cues, particularly emojis, within structured educational content remains in its early stages.

Related works have demonstrated that emojis improve not only emotional expressions but also clarify meaning, and create more engaging communications [

13,

14]. In educational contexts, emojis have been explored in areas such as student feedback, peer discussions, and course materials. Research indicates that emojis can improve clarity in feedback by reinforcing positive reinforcement and reducing the ambiguity of text-based communication. Additionally, their use in learning materials has been shown to reduce cognitive load by providing visually appealing representations of concepts, thereby supporting information retention [

15]. In online learning environments, the presence of emojis has been linked to increased social presence, fostering a sense of community and collaboration among learners [

16]. Despite these findings, existing approaches to emoji integration in education lack a structured methodology for determining appropriate placements, emotional alignment, and pedagogical relevance, particularly in early childhood education settings where visual stimuli play a critical role in cognitive and emotional development [

17].

This study is grounded in a multimodal learning perspective in early childhood education. Specifically, we draw on (i) dual coding and multimedia learning principles, which posit that children learn more effectively when verbal information is paired with meaningful visual cues, and (ii) socio-constructivist developmental views emphasizing the role of semiotic tools and scaffolding in supporting emerging language and emotional understanding. In our context, emojis are treated as lightweight visual symbols that can (a) reduce ambiguity in short instructions, (b) signal affective tone and feedback, and (c) provide scaffolds for attention and recall when appropriately aligned with the learning objective and the child’s developmental stage. Importantly, the proposed model operationalizes these principles by recommending emojis only when they serve a pedagogical function (reinforcement, prompting reflection, or emotional support) rather than as decorative elements.

Despite the growing adoption of digital tools in Early Childhood Education (ECE), their use also raises important concerns. Excessive screen exposure may reduce opportunities for hands-on, social, and play-based learning, and poorly designed interfaces can distract children or increase cognitive overload rather than support understanding. In addition, visual symbols—including emojis—may be interpreted differently across cultures and languages, which can introduce ambiguity if not carefully selected and age-appropriately applied. Within this context, our goal is not to claim superiority over educators’ expertise, but to provide an AI-assisted mechanism that supports standardized, scalable, and context-aware emoji placement aligned with expert annotations, enabling consistent content preparation at scale and reducing teacher workload when large volumes of digital learning materials must be produced and updated.

This study proposes a novel AI-driven framework for standardized, expert-aligned emoji placement within ECE materials. The approach employs advanced deep learning techniques, integrating BERT for contextual embedding extraction, GRU for sequential pattern recognition, DNN for classification and emoji recommendation, and a DECOC decoding layer. By leveraging contextual embeddings and an auxiliary sentiment-based mapping layer, the proposed system is aimed to enhance comprehension and engagement rather than serving as a mere visual addition. Unlike traditional heuristic-based approaches, this framework is context-aware of content nuances, aligning emoji recommendations with both learning objectives and the instructional tone/affective intent expressed in the text.

The originality of this research lies in its systematic approach to emoji recommendation, supported by the development of an annotated dataset specific to early childhood education. This dataset serves as a foundational resource for training and validating the AI model, enabling a more precise and pedagogically informed application of emojis in digital learning materials.

In this work, we do not aim to re-establish the pedagogical efficacy of emojis as an educational intervention. Instead, building on prior literature that reports the benefits of lightweight visual cues in learning communication, we frame emoji placement as a computer science task: learning educator-consistent, context-aware emoji recommendations under an explicit guideline. The educator-facing study is therefore included as a feasibility/usability check and requirement grounding, not as a controlled pedagogical validation of learning gains.

To guide the study and ensure that the reported results directly address the stated aims, we formulate three research questions. RQ1 investigates how early childhood educational texts can be systematically annotated with pedagogically meaningful emoji placements (EduEmoji-ECE) while maintaining annotation reliability. RQ2 examines the extent to which the proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model improves emoji-placement prediction compared with baseline approaches. RQ3 assesses feasibility and observed associations of emoji-enhanced vs. text-only versions (engagement/comprehension/retention proxies) in an exploratory educator feasibility check.

This paper investigates emoji placement in ECE materials from a computer science perspective: learning expert-consistent, context-aware emoji recommendations under an explicit annotation guideline. In addition, we report an exploratory educator feasibility check to examine whether emoji-enhanced presentations are associated with favorable engagement/comprehension indicators in our study setting. We do not claim causal educational effects, and we scope pedagogical interpretations accordingly.

While educators can place emojis manually, carrying this out consistently across large collections of digital learning materials is time-consuming and may vary across individuals and settings. This motivates an AI-assisted workflow that can generate consistent, pedagogically aligned emoji suggestions at scale, reducing repetitive authoring effort and supporting rapid updates. This motivation is compatible with evidence that teachers spend meaningful time on lesson preparation and that ECEC staff allocate working time to planning/preparation and documentation tasks.

This work contributes (i) a computational framework that learns expert-aligned emoji placement rules from pedagogically annotated ECE materials, and (ii) an empirical ECE evaluation reporting exploratory associations/feasibility indicators observed with emoji-enhanced versus text-only presentations in our study setting, without causal claims. The evaluation focuses on emoji-enhanced content produced using hybrid placements (model suggestions and rule-based/educator-constrained mapping), and we report claims accordingly.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on emoji recommendation in educational content and AI applications in sentiment and contextual analysis.

Section 3 presents the proposed framework, detailing its AI architecture and alignment with pedagogical principles.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and measurement protocol.

Section 5 presents the model results and the educator feasibility findings.

Section 6 provides a detailed discussion. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study, highlighting contributions and future directions for AI-enhanced ECE content.

2. Related Works

Although this work is situated in Early Childhood Education (ECE), the proposed contribution is an AI framework for context-aware emoji recommendation.

2.1. Macro-Level AI-in-Education Context

Multiple surveys synthesize AI applications in education—especially in higher education, professional training, and medical learning—and highlight recurring deployment challenges (data governance, bias, transparency, teacher adoption, and implementation constraints) [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Although these surveys are not specific to preschool learners or emoji-based scaffolding, they provide a macro-level context for the practical and ethical considerations relevant to deploying AI-assisted authoring tools in real classrooms [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

2.2. Emojis and Visual/Emoji-Based Scaffolding in Learning

Mokhamed et al. [

27] compared different studies to evaluate deep learning and machine learning algorithms for emoji recommendation in Arabic text. Although their research did not specifically focus on e-learning, their findings provide models that can improve communication within learning platforms. Authors demonstrated that advanced algorithms can accurately predict emojis based on textual context, indicating their potential for intelligent authoring-support tools that align emoji recommendations with instructional tone and textual context.

Zarkadoulas et al. [

28] carried out an empirical study on how emojis are used to express emotions in online mathematics classes. They asked 100 students to complete a questionnaire about which emojis they chose to show how they felt about different math problems. The results showed that emojis can clearly reflect students’ emotional states and give teachers useful feedback to adjust their teaching. This highlights the value of emojis as tools for emotional expression and feedback in digital learning.

Bai et al. [

29] conducted a systematic review on how emojis are developed, used, and applied in computer-mediated communication, including education. Their review showed that emojis can support emotional expression and increase engagement in e-learning contexts. They also pointed out that more research is needed on how emojis can be used specifically to improve student engagement and learning outcomes.

Unlike studies that treat emoji prediction as a generic social-media task, our setting constrains emoji labels to pedagogical functions and uses sentiment as an auxiliary signal rather than the sole driver of recommendations.

2.3. Child-Centered Intelligent Systems

Huijnen et al. [

30] reviewed AI-driven robotic interventions for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), highlighting their role in therapy and education.

Yilin et al. [

31] introduced EmoEden, an AI-based tool designed to help children with high-functioning autism improve how they recognize and express emotions. The tool combines large language models with text-to-image models to provide emotional learning experiences that are personalized and context aware.

Sajja et al. [

32] proposed a framework that uses AI and Natural Language Processing to build an interactive learning platform aimed at reducing cognitive load and offering personalized support to learners. Bewersdorff et al. [

33] examined how multimodal large language models such as GPT-4V can be used in science education, showing their potential for creating personalized and interactive learning experiences. Kamalov et al. [

34] discussed the broader impact of AI on education, focusing on systems such as intelligent tutoring and personalized learning, and also raised important challenges and ethical issues that need to be addressed.

Denny et al. [

35] provide an overview of the potential of generative AI to enhance education, discussing advances, opportunities, and challenges in the field.

Table 1 provides a summary of these reviewed studies, outlining their methodologies, findings, and identified limitations. Low-relevance studies are retained only as macro-level anchors to contextualize the proposed framework within established AI-in-education research, particularly regarding deployment constraints, ethical risks, and adoption barriers that remain applicable when systems are introduced in real classrooms. Although these works do not target preschool learners directly, they provide transferable insights on methodological trends and governance considerations (e.g., transparency, bias, privacy, and implementation feasibility) that help motivate our design choices and strengthen the interpretation of our results in an ECE-sensitive setting.

However, these studies do not provide an ECE-oriented dataset with systematic pedagogical emoji annotations, nor a unified AI framework validated for educational emoji recommendation, motivating the proposed EduEmoji-ECE and hybrid model.

3. Proposed AI-Driven Model

To support pedagogically aligned emoji recommendation and to explore whether emoji-enhanced presentations are associated with favorable engagement/comprehension indicators, this study proposes a structured AI-driven approach for the strategic integration of emojis into learning content. The proposed model leverages advanced artificial intelligence techniques to align emoji recommendation with pedagogical objectives, ensuring that visual elements support cognitive and emotional development rather than serving as mere decorative features. The model is composed of the following steps: data collection, preprocessing, Sentiment and Context Analysis, Model Development.

3.1. Data Collection

The educational materials were collected by the author in collaboration with early childhood educators. The early childhood educators were recruited using purposive sampling from participating preschool/early-grade settings. Eligibility criteria included (i) formal training in early childhood education (or equivalent certification), (ii) at least five years of classroom experience with children in the target age range, and (iii) regular involvement in curriculum-aligned lesson planning. Educators were invited through institutional/professional networks; no names or identifying details are disclosed to preserve anonymity. In this study, ‘ECE learning objectives’ refer to the domains and indicators defined in the Saudi Ministry of Education early childhood curriculum framework and early learning/development standards (Birth–8 years; Kindergarten 3–8 years). These standards specify the core developmental and learning domains used to guide the selection of age-appropriate instructional materials. Inclusion criteria were: (i) alignment with common early learning domains (language/literacy, numeracy, social-emotional learning, basic science), (ii) short, self-contained textual segments suitable for classroom delivery, and (iii) suitability for digital presentation (clear instructions/story segments). Exclusion criteria were: (i) content not appropriate for preschool developmental level, (ii) materials containing any personally identifiable child information, and (iii) segments with insufficient textual context for meaningful emoji recommendation.

Materials were drawn from a mixed pool consisting of (i) published early-childhood teaching resources (e.g., storybooks/worksheets/lesson scripts) and (ii) educator-authored classroom prompts used in routine instruction. The initial pool included some borderline or higher-grade items collected during broad sampling; these were removed during screening. Developmental appropriateness was determined by the recruited ECE educators using the same curriculum framework and age-level expectations.

The dataset is carefully annotated by childhood educators to identify sections where emoji recommendation can enhance comprehension, engagement, or emotional support. The goal is to systematically determine how and where emojis can facilitate concept retention, foster interaction, and improve overall learning experiences for young children.

The dataset therefore contains educational text only, and does not include any learner identifiers, recordings, or personal profiles.

Annotation was performed by two early-childhood educator annotators recruited using the eligibility criteria above. A stratified subset of 220 sections was independently double-annotated to estimate agreement; the remaining sections were single-annotated under the same guideline. Disagreements in the double-annotated subset were resolved via adjudication by a senior educator. All annotators completed a calibration session and jointly annotated a pilot subset to harmonize interpretations. Inter-rater reliability on the double-annotated subset was κ = 0.77 (Cohen’s kappa), indicating substantial agreement; during the pilot calibration only, with three educators, Fleiss’ κ = 0.71. The corresponding author did not assign pedagogical labels and was responsible only for dataset curation and model training/evaluation.

A structured dataset, referred to as EduEmoji-ECE, is developed to support this research. It is organized as follows:

Document ID: A unique identifier for each educational resource.

Document Type: Classification of materials (e.g., storybook, worksheet, video transcript).

Educational Context: Includes age group, subject area, and learning objectives.

Content: The full text of the document, including references to multimedia elements (e.g., images, audio).

Annotations: Sections annotated with potential emoji placements, detailing their intended function (e.g., reinforcement of a learning concept, emotional support, question prompt).

Complexity Level: Categorization of text difficulty (low, medium, high), ensuring that emojis are appropriately tailored to learners’ cognitive development stages.

Suggested Emojis: The recommended emojis for each annotated section, along with justifications for their selection.

Metadata: Information about the source, authorship, and annotation details.

Contextual Information: Prerequisite knowledge required, learning goals, and additional references for educators.

This structured approach ensures that emoji recommendation is systematically documented and optimized for pedagogical effectiveness in ECE.

A subset of commonly used emojis is selected for evaluation, as described in

Table 2.

The resulting EduEmoji-ECE dataset contains 1100 annotated text sections extracted from early childhood educational materials. Each section is treated as a unit for emoji placement annotation and, where applicable, sentiment labeling. All distributions and descriptive analyses (

Table 3 and

Table 4) are computed from the human-produced EduEmoji-ECE annotations. Sentiment labeling and its distribution are reported in

Section 3.3.

Table 3 presents the distribution of annotation categories within the dataset.

The dataset composed of six mainly used emojis, with 😊 (smiling face) and 🤔 (thinking face) being the most frequently applied. These emojis were used for positive reinforcement and critical thinking, respectively.

Table 4 reports the exact distribution of the primary emoji label assigned during annotation (n = 1100 sections). These values are descriptive and are not interpreted as statistically significant differences between emojis.

These distributions are reported solely to describe corpus composition prior to modeling; therefore, we do not draw conclusions from small differences between emoji frequencies. Taken together,

Table 3 and

Table 4 characterize EduEmoji-ECE as a curated, pedagogically oriented corpus with explicit annotation categories and emoji-function labels, providing the descriptive basis required for training and validating the proposed emoji placement model. The sentiment labeling procedure and the corresponding distribution are reported separately in

Section 3.3.

3.2. Text Preprocessing

The preprocessing steps serve two distinct purposes: (i) light text cleaning to remove noise that can harm tokenization (e.g., duplicated symbols, malformed characters), and (ii) optional normalization (e.g., lemmatization) used only for corpus-level statistics and auxiliary analyses. Importantly, the contextual encoder (BERT) and the emoji recommendation model operate on the original (non-lemmatized) text, preserving negation, word order, and pragmatic cues required for sentiment interpretation. Lemmatized text is therefore not used as the primary input for sentiment or emoji prediction, but only for descriptive analysis and feature consistency where applicable.

The following key steps are implemented:

Light cleaning: remove duplicated symbols, malformed characters, and formatting noise that can harm tokenization.

Tokenization: BERT WordPiece tokenization (bert-base-uncased), preserving word order and negation.

Length handling: truncate/pad to the maximum sequence length (128).

Auxiliary normalization (statistics only): optional lemmatization used only for corpus-level descriptive analyses; it is not used as input to BERT or the emoji classifier.

These preprocessing steps ensure that the text data is standardized, free from noise, and ready for efficient AI-driven analysis in subsequent phases.

3.3. Sentiment Labeling and Analysis

Sentiment analysis plays a supporting role in determining how emojis should be integrated into ECE materials. By analyzing the emotional tone of text segments, this phase identifies areas where emojis can enhance engagement, provide emotional support, or reinforce key learning concepts.

Before training the sentiment model, each EduEmoji-ECE text section was assigned a sentiment label by 2 early childhood education educators using written guidelines. Labels follow a three-class scheme (positive/neutral/negative) aligned with instructional tone. Disagreements were resolved through adjudication by a senior educator, and the resulting labels were used as supervision for training and evaluating the sentiment model. This sentiment-labeled data corresponds to the same EduEmoji-ECE corpus described in

Section 3.1 (n = 1100 sections). The sentiment labelers were the same two educator annotators described in

Section 3.1 (pilot calibration involved three educators only), and sentiment disagreements were resolved using the same adjudication procedure.

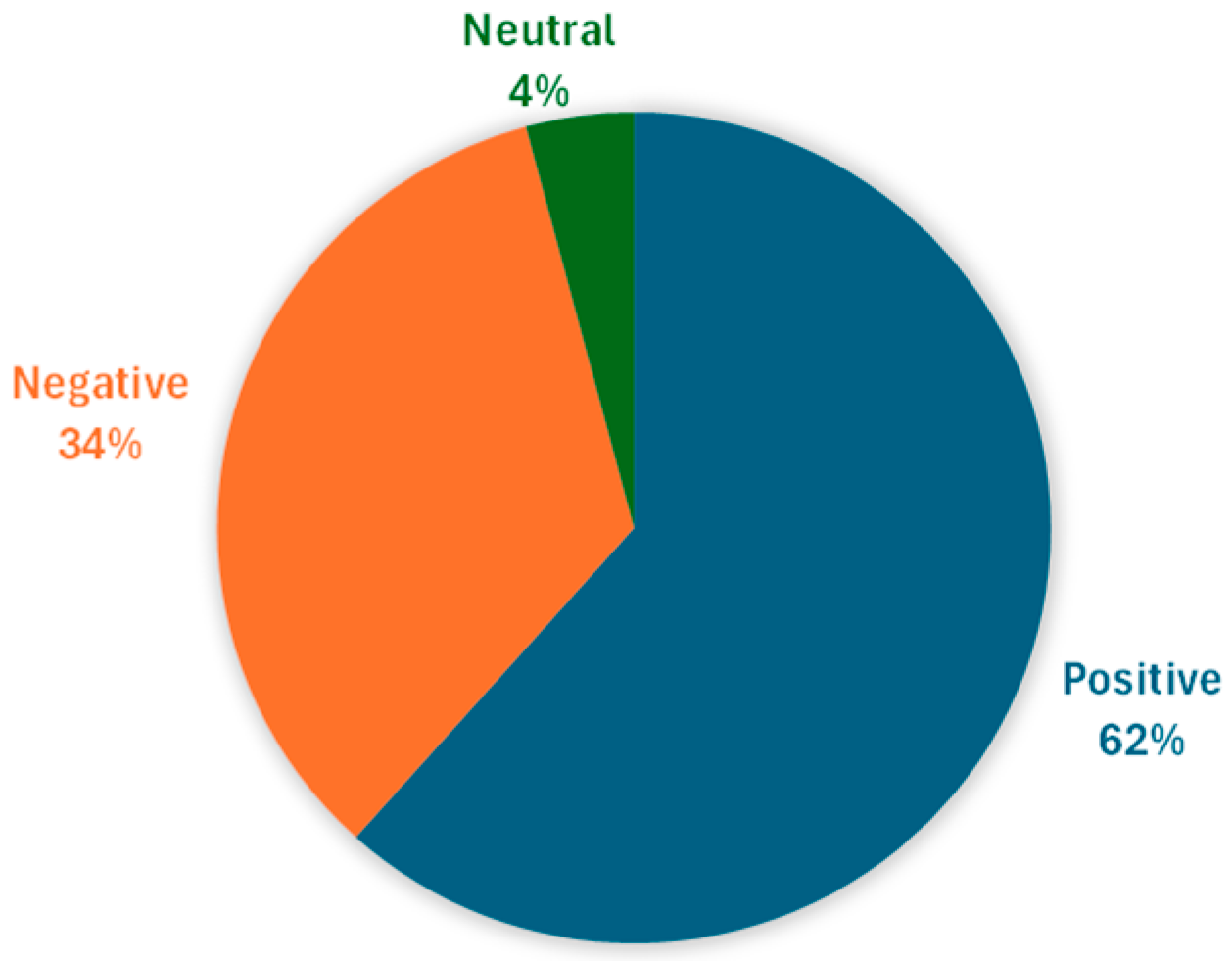

Figure 1 presents the distribution of sentiment categories in the dataset.

Figure 1 visualizes the distribution of sentiment labels in the human-annotated EduEmoji-ECE dataset. The positive sentiment (62%) aligns with the objective of creating an encouraging and fast learning environment. However, the negative (34%) and neutral (4%) sentiments shows that the dataset represents a balanced emotional landscape, allowing for a more natural and diverse emoji application.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, including Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), are employed to generate contextual embeddings that capture the nuanced meanings of text. This approach ensures that emoji placement aligns with both content context and student emotions.

Sentiment analysis categorizes text segments into three primary classifications:

Positive Sentiment: Reinforced with encouraging emojis (e.g., 😊, 🎉).

Negative Sentiment (Frustration or Difficulty): Complemented with supportive emojis (e.g., 😢, 🤔).

Neutral or Informational Content: May include guidance emojis (e.g., 💤 for optional content).

To ensure that emoji recommendations align with the emotional tone and pedagogical intent of the content, the study integrates a BERT-based sentiment analysis model. The sentiment classification process categorizes textual content into positive, neutral, or negative sentiment to determine appropriate emoji placement. Each text segment is assigned a sentiment score ranging from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates a stronger sentiment in a specific category. Here, the score denotes the model’s predicted probability (confidence) for the assigned sentiment class, obtained from the softmax output. A threshold-based approach was implemented to refine emoji-function mapping based on sentiment confidence. If sentiment confidence exceeds 0.7, the sentiment-based mapping is applied with high confidence; if it falls between 0.4 and 0.7, an additional context-checking mechanism is used before applying sentiment-based refinement.

Table 5 presents sample sentiment-based emoji assignments.

For mixed-sentiment cases, where a sentence contains both positive and negative tones, the model utilizes context-aware weighting to assign multiple emojis or prioritize the dominant sentiment. For example, in the sentence “Learning shapes can be tricky, but with practice, you will succeed!”, the model identifies 60% positive sentiment and 40% challenge-related sentiment. In such cases, the system assigns 😊 (Encouragement) and 🤔 (Critical Thinking) to balance motivation and complexity. Similarly, for a sentence with ambiguous emotional tones, such as “This exercise is optional, but it may help you understand better.”, the model assigns 💤 (Optional Content) and 🤔 (Thinking Face) to signal supplementary learning.

By handling mixed-tone sentences through confidence thresholds and optional multi-emoji assignment, the sentiment component enables contextual flexibility, ensuring that emojis serve an educational signaling purpose rather than acting as decorations. The sentiment model was trained using the expert-labeled sentiment annotations described above, and the sentiment–emoji mapping rules were validated by the same experts to ensure that recommendations remain pedagogically appropriate and emotionally consistent with the text. This approach helps keep emoji placement contextually relevant and reduces misleading sentiment assignments.

By integrating sentiment analysis with contextual embeddings, this methodology enhances the effectiveness of emoji placement in ECE materials, fostering an interactive and emotionally supportive learning experience.

Sentiment predictions are used as an auxiliary signal to guide emoji-function selection and to handle mixed instructional tone, while the final emoji placement prediction is performed by the proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC framework.

3.4. Proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC Emoji Placement Model

The sentiment analysis module is used only to map predicted emoji functions (e.g., encouragement/support/optional) and to handle mixed-tone text segments; it does not feed features into the BERT–RU–DNN–DECOC classifier. The BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model predicts emoji placements directly from text, and sentiment analysis is applied as a post-processing layer to validate or refine emoji-function selection. In this paper, emoji placement refers to emoji class recommendation (what emoji to suggest for a segment); the insertion position (where to insert it) is handled by the annotation guideline.

The BERT-GRU-DNN-DECOC architecture was selected for its ability to capture contextual semantic variations, preserve sequential dependencies, and enhance classification performance. Each component of the model plays a crucial role in optimizing emoji placement within early childhood educational content. Traditional BERT-LSTM models are commonly used for sequence modeling, but GRUs provide similar performance while being computationally more efficient, making them more suitable for real-time emoji recommendations [

36]. Transformer-based models, while offering superior contextual embeddings, have higher computational demands, making them less practical for lightweight real-time applications in early learning environments. Additionally, Reinforcement Learning (RL) approaches could optimize emoji placement dynamically; however, their reliance on extensive training data and iterative feedback mechanisms makes them less suitable for structured educational content, where predefined rules and sentiment-based placements are preferred.

Emoji recommendation in educational text can be posed as a multi-label problem because a segment may warrant more than one emoji (e.g., reinforcement plus a reflective prompt). However, the prediction pipeline can be decomposed into two stages: (1) a decision on whether an emoji is pedagogically warranted (and optionally the number of emojis), and (2) classification among a predefined set of emoji functions/classes aligned with pedagogical intent. This decomposition supports stable learning under class imbalance and label ambiguity while preserving the ability to output multiple emojis through top-k selection and thresholding. For transparency, we report which stages are learned and which are rule-constrained, and we evaluate alternatives that treat the output as direct multi-label prediction.

In EduEmoji-ECE, each segment is annotated with a single primary emoji label for training and evaluation; multi-emoji suggestions are supported only at inference via top-k/thresholding, but reported metrics are computed against the primary label.

We include DECOC (a data-driven error-correcting output-code design within the ECOC family) because the emoji-function decision in ECE text exhibits (i) subtle inter-class boundaries (e.g., “encouragement” vs. “support”), (ii) imbalance across emoji functions, and (iii) occasional annotation noise due to inherently context-dependent emoji semantics. ECOC decomposes a multi-class decision into an ensemble of binary learners, and decoding provides an error-correcting mechanism that can improve robustness when individual binary decisions are imperfect. DECOC further optimizes the code design using data-driven criteria, making it suitable when some classes are close in representation space and separability is uneven across labels.

We also clarify how DECOC compares with canonical multi-label strategies. Binary Relevance (sigmoid one-vs-rest) is simple and scalable but can ignore label correlations and may produce inconsistent label combinations. Classifier Chains can model correlations but may amplify early-chain errors and increase training/inference complexity. In our setting, DECOC is used to strengthen the core discrimination among emoji function classes, while multi-label outputs are produced via calibrated top-k/thresholding.

To improve the reliability of multi-class classification, DECOC is incorporated into the architecture. Unlike softmax-based classifiers, which often struggle with overlapping sentiment categories, DECOC decomposes complex classification tasks into multiple binary subtasks, introducing redundancy that enhances classification stability [

37,

38]. This approach is particularly beneficial when dealing with mixed-sentiment cases, where multiple emojis could be assigned to a single text segment. The error-correcting mechanism of DECOC ensures that emoji predictions remain consistent and interpretable, ultimately improving classification robustness.

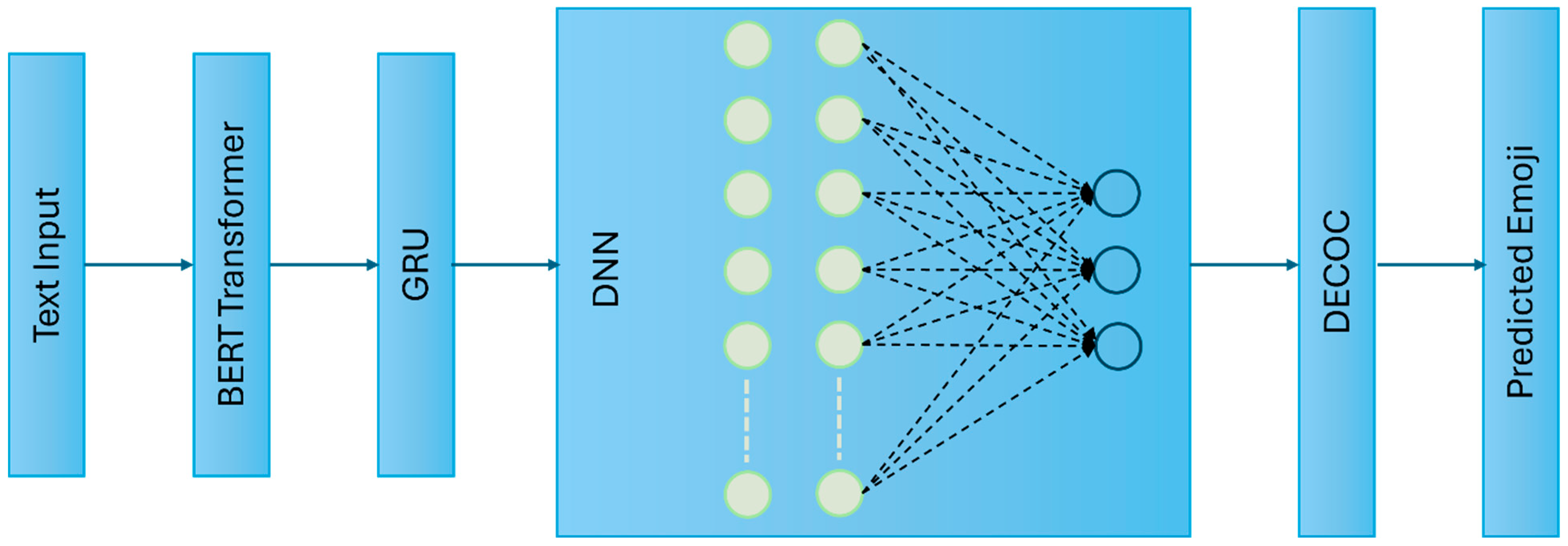

To develop an intelligent system capable of accurately recommending contextually relevant emojis, the study integrates a hybrid deep learning model, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This model consists of:

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT): Extracts contextual embeddings to capture semantic meaning and emotional tone from textual content.

Gated Recurrent Units (GRU): Preserves sequential dependencies in text, ensuring that emoji recommendations align with natural language flow and learning context.

Deep Neural Networks (DNN): Identifies complex linguistic and contextual relationships, refining emoji selection for enhanced comprehension and engagement.

DECOC: Optimizes multi-class classification by reducing prediction errors, stabilizing emoji assignments, and improving model interpretability.

We fine-tuned bert-base-uncased with maximum sequence length 128 and batch size 16. The dataset was split into 80/10/10 (train/validation/test), and the model was trained using cross-entropy loss with the AdamW optimizer (learning rate 2 × 10−5) for up to 12 epochs, using early stopping on validation performance. DECOC was used to improve robustness to class imbalance and to reduce confusion among semantically close emoji categories.

Each of these components contributes to a robust AI architecture capable of dynamically adapting to educational content nuances. The system processes text data at multiple levels—analyzing context, sentiment, and difficulty—to determine the most suitable emoji placements for enhancing comprehension and engagement.

Given an input text segment, we tokenize the sequence and compute contextual embeddings using BERT. The resulting representations are then passed to a GRU to capture sequential dependencies, and the GRU output is fed into a DNN classifier to produce class scores, which are decoded using the DECOC scheme to obtain the final emoji class prediction. Sentiment analysis is subsequently applied as a post-processing step to validate or refine the emoji-function label in mixed-tone segments, as described above.

The EduEmoji-ECE dataset serves as the training set for this model. Text segments are labeled with corresponding emojis, enabling the model to learn relationships between content, sentiment, and visual augmentation. The training process optimizes the model’s parameters to minimize classification errors, ensuring accurate emoji predictions tailored to ECE settings.

This structured AI-driven approach provides a scalable solution for systematically integrating emojis into early childhood educational materials. By aligning emoji recommendations with pedagogical principles, the model enhances digital learning experiences, making content more engaging, comprehensible, and emotionally supportive for young learners.

4. Educator Feasibility Evaluation

This educator’s feasibility evaluation examined whether emoji-enhanced (AI-assisted) materials were associated with differences in engagement, comprehension, and retention indicators, and collected qualitative feedback on the learning experience. Conducted by five experienced early childhood educators, the study involved a sample of 100 children, ensuring a diverse representation of young learners. These five educators were recruited using the same eligibility criteria described in

Section 3.1 (ECE qualification and minimum teaching experience). These teachers were distinct from the two educator annotators who labeled EduEmoji-ECE in

Section 3.1/

Section 3.3. To minimize bias, they were not involved in dataset annotation; their role in this phase was limited to administering classroom activities and recording observational measures. To systematically address these objectives, the evaluation was structured into distinct sections, beginning with demographic information, which collected details on participants’ age, gender, and learning context (preschool setting for the sessions; home observations were captured only via the optional caregiver checklist when available).

The classroom activities were implemented as part of routine instruction in an established educational setting and did not introduce procedures outside standard learning practice. No personally identifiable information was collected; all analyses used anonymized and aggregated outcomes, and no audio/video recordings were made.

The subsequent sections assessed four key dimensions: engagement (attention/participation), comprehension, retention, and overall experience. Comprehension was evaluated based on whether emojis were associated with clearer understanding of educational content. Retention was assessed by examining whether emoji-enhanced materials were associated with higher knowledge recall over time. Additionally, qualitative feedback was collected to determine learners’ overall enjoyment and their perceived usefulness of emojis in learning. A combination of Likert scale responses, multiple-choice questions, and open-ended observational reports was used to capture both quantitative and qualitative data. Educators completed 5-point Likert items (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) immediately after each activity; children were not asked to self-rate. Caregiver feedback was collected using a short weekly checklist (when available) summarizing observed reactions at home. To refine the survey instrument (separate from the annotation calibration in

Section 3), a pilot was conducted with a smaller group of ten children under the supervision of educators. This phase refined the survey questions to enhance clarity in interpretation and alignment with developmental appropriateness. The survey was administered following an exposure period to emoji-integrated learning materials, ensuring that responses were based on meaningful interaction with the educational content.

Study design and counterbalancing. To reduce content-related confounds, each child was exposed to the same educational content in two presentation versions: (i) an emoji-enhanced version (AI-assisted, produced via hybrid placement: model suggestions followed by educator-constrained/rule-based mapping) and (ii) a text-only version without emojis. The “non-emoji presentation” refers to this text-only condition delivered within the same study (not an external control group). A within-subject, counterbalanced design was used: approximately half of the children received the emoji-enhanced version first and the text-only version second, and the remaining half received the reverse order. To reduce immediate carryover, the two versions were separated by a brief distractor activity (5–10 min). The same comprehension prompts were used for both versions, with parallel/reordered items when applicable to reduce repetition effects.

A structured knowledge assessment was used to evaluate comprehension and short-term learning progress. A baseline pre-test was administered before the two-version exposure began to measure initial understanding of the targeted concepts. After completion of the scheduled activities (during which both emoji and no-emoji versions were presented in counterbalanced order), an end-of-period post-test was administered. Pre/post score differences were used as an overall learning-progress indicator, while within-session measures (immediate checks and reaction time) supported version-level comparisons.

In addition to knowledge assessments, behavioral interaction data were collected during learning sessions to check engagement levels. Educators recorded observations related to the frequency of emoji engagement, the time children spent interacting with emoji-enhanced materials compared to standard text-based content, and their verbal and non-verbal reactions to emoji-assisted explanations. Enthusiasm, curiosity, or confusion were observed to assess the emotional and cognitive impact of emojis in educational settings. These observations allowed for a qualitative interpretation of engagement, complementing the quantitative measures.

For reaction time, children answered equivalent comprehension prompts after each version (emoji-enhanced vs. text-only), and response time for correct answers was recorded. Counterbalancing was implemented at the child level using an A/B order assignment.

Because preschool learners cannot reliably self-report, outcomes were operationalized using a multi-source, age-appropriate protocol emphasizing observable behavioral engagement and short performance checks. Engagement was defined and measured primarily as behavioral engagement (on-task attention, participation, and persistence), consistent with common engagement frameworks in educational research.

Engagement was captured using (i) time-on-task (minutes spent actively participating in the activity) and (ii) a brief educator observation rubric with predefined indicators (sustained visual attention, spontaneous participation/initiations, positive affect, and task persistence). The rubric was developed for this study in collaboration with the participating ECE educators and refined during a rubric calibration pilot; educators applied the rubric immediately after each activity. To support scoring reliability, approximately 20% of sessions were double-coded to estimate agreement.

Comprehension was assessed using a short curriculum-aligned post-activity check administered immediately after exposure (picture-based recognition), scored as the proportion of correct responses. Items were educator-developed based on the learning objectives of the corresponding materials and reviewed for content coverage. Where applicable, internal consistency is reported.

Retention was assessed using a delayed recall/recognition probe administered after a delay (next session/day), targeting the same key concepts as the immediate check but using reordered/parallel items to reduce immediate repetition effects. The delayed probe targeted the same constructs as the immediate post-activity check, but used parallel/reordered items to reduce simple recall of the prior answers.

Overall experience was summarized through educator-rated Likert items (perceived ease of delivery, enjoyment/child comfort, and smoothness of interaction) completed after each activity, complemented by brief structured caregiver feedback (short checklist-style items describing child reactions outside the session when available).

We emphasize that these instruments are brief, pragmatic measures intended for exploratory application validation, rather than standardized psychometric scales; therefore, findings from this study are interpreted as supportive evidence of feasibility and alignment with prior literature, not as definitive educational effect estimates.

By integrating these quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods, the study provided a comprehensive assessment of emoji-enhanced learning materials in early childhood education. Together, these measures provide a practical, multi-source characterization of learner responses under routine classroom conditions; however, results should be interpreted as exploratory.

5. Results

This section reports (i) predictive performance of the proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model on EduEmoji-ECE and (ii) an educator feasibility evaluation examining whether emoji-enhanced (AI-assisted, hybrid) materials are associated with differences in engagement, comprehension, and retention indicators. These findings are interpreted as exploratory and do not establish causal educational effects.

5.1. Model Verification and Performance Analysis

The proposed AI model (BERT-GRU-DNN-DECOC) was evaluated to determine its effectiveness in predicting the appropriate emoji class (recommendation) for each ECE text segment, consistent with the placement definition in

Section 3.4. The model’s performance was assessed using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The dataset was split into 80%/10%/10% for train/validation/test, respectively, ensuring a well-balanced evaluation. Each text segment underwent light cleaning and BERT WordPiece tokenization (max length 128); BERT was then used to generate contextual embeddings for the classifier. The BERT-GRU-DNN-DECOC model achieved high performance, as shown in

Table 6.

Table 6 reports performance of the baselines trained/evaluated on EduEmoji-ECE (MLR, LSTM) and the proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model. In addition, we list reported values from Bai et al. (2019) [

29] and Zarkadoulas et al. (2024) [

28] only to contextualize typical metric ranges in related work; these figures are not directly comparable because they were obtained under different datasets and experimental protocols. On EduEmoji-ECE, the proposed BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC achieves 95.3% accuracy, 93.0% precision, 91.8% recall, and 92.3% F1, indicating strong discrimination among the six emoji classes.

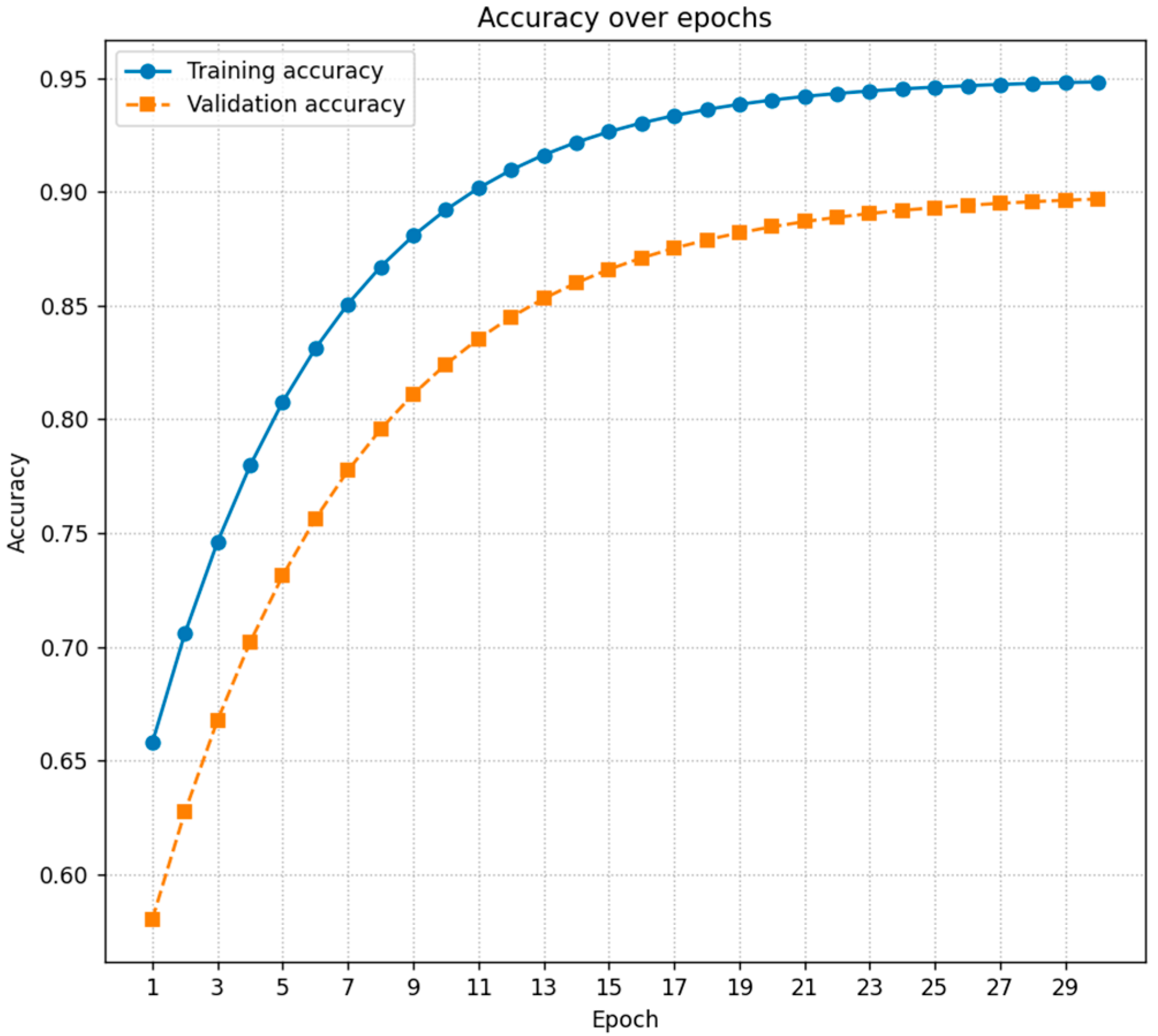

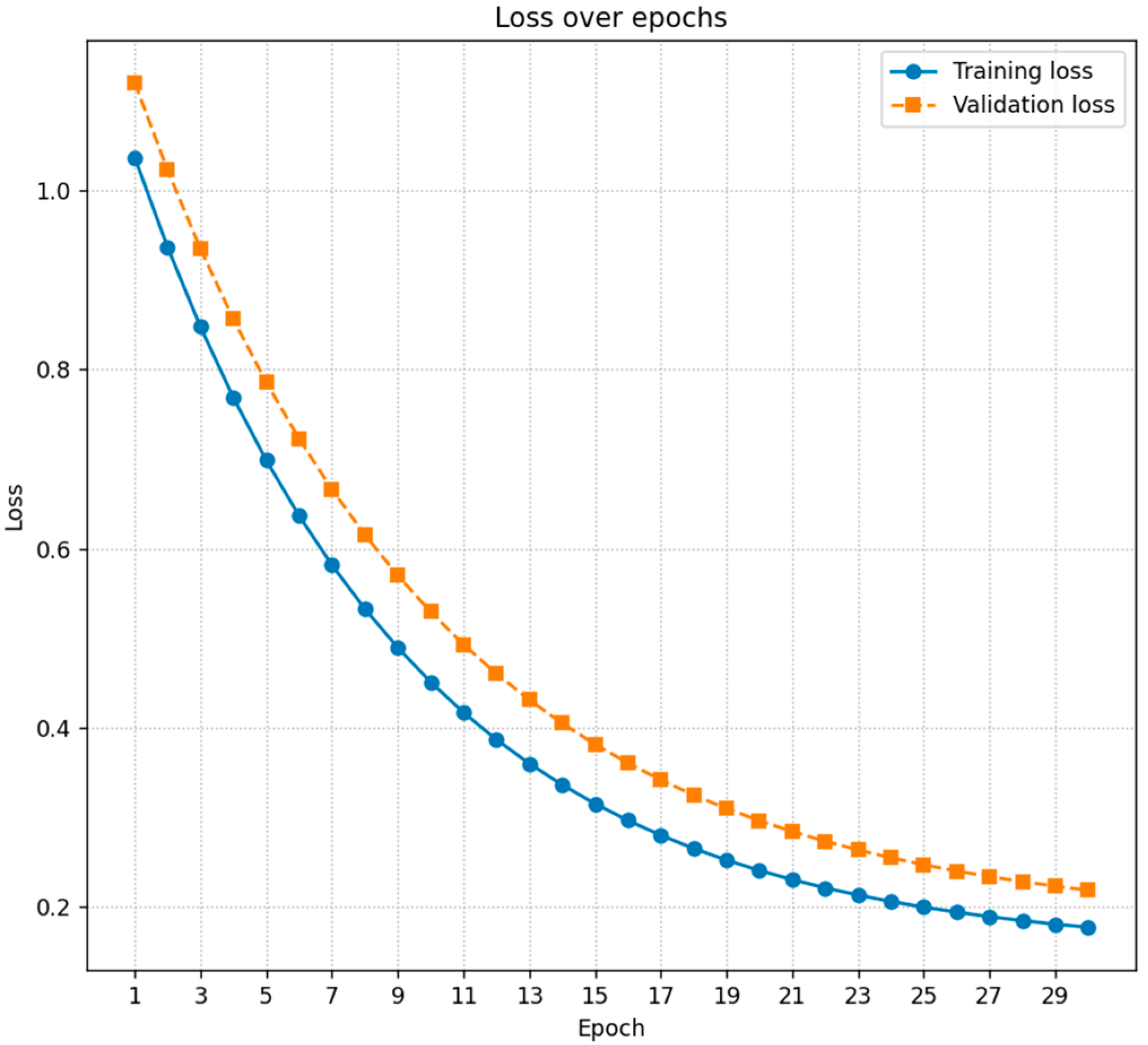

To better understand the learning behavior of the proposed architecture, we recorded the training and validation accuracy and loss at each epoch. As shown in

Figure 3, the validation accuracy follows the training accuracy closely and saturates after approximately 12 epochs, which suggests that the model converges without severe overfitting. In parallel,

Figure 4 shows a smooth decrease in both training and validation loss, with the two curves converging to similar values. This pattern indicates that the BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model learns a stable decision boundary and generalizes well to unseen examples of educational text.

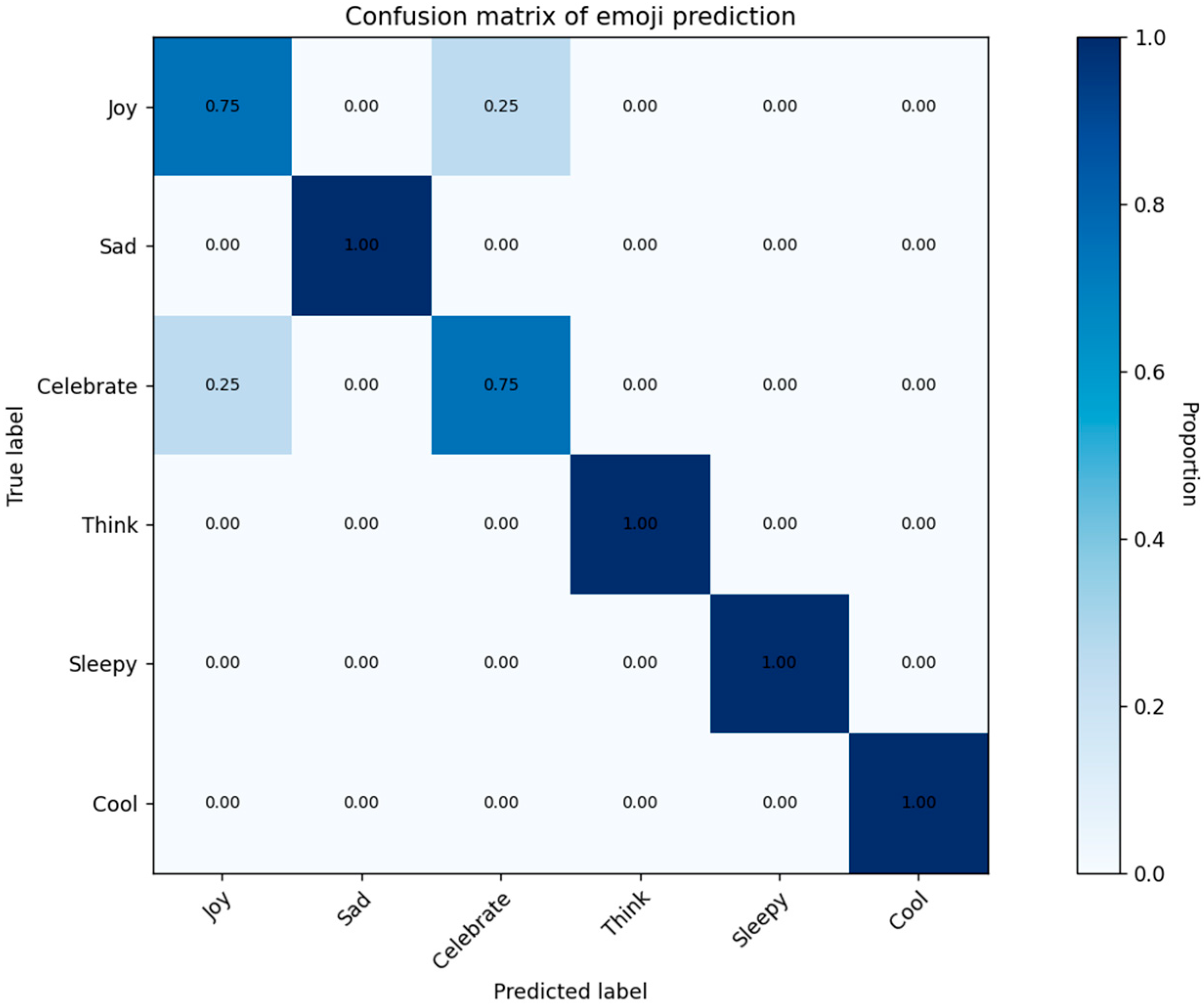

Beyond the overall scores, we also looked at how the model behaves for each emoji class separately by plotting a confusion matrix.

Figure 5 reports the predictions of the BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model for the six emoji labels in the EduEmoji-ECE test set. Most of the mass is concentrated on the diagonal, which means that the classifier correctly recognizes the majority of emoji assignments, especially for the most frequent affective categories. The errors that do appear are largely between emojis that are close in meaning. For instance, most errors occur between semantically close emoji categories. For example, some segments labeled 😊 (positive reinforcement) are predicted as 🎉 (celebration), and a subset of 🤔 (reflection/prompting) cases are misclassified as 😢 (support for difficulty) when the instructional tone is ambiguous. Overall, this analysis indicates that the model attains strong recognition performance across all emojis while keeping the level of cross-emoji confusion relatively low.

To test whether improvements are robust to randomness, we repeated training/evaluation for N = 20 runs. In each run, all models were evaluated on the same train/validation/test split (the split varied by run via the random seed). We then performed paired t-tests on per-run accuracies comparing BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC against each baseline. All comparisons were significant after Holm–Bonferroni correction (paired, df = 19; adjusted p < 0.001). We also report a 95% confidence interval for mean accuracy across runs (94.8–95.7%).

To assess feasibility for practical deployment, we report computational efficiency in terms of training time and inference latency. Training was conducted on Intel Xeon (2.2–3.0 GHz), NVIDIA Tesla T4 16 GB, 32 GB RAM using sequence length 128, batch size 16, and up to 12 epochs with early stopping (converged after approximately 10–12 epochs depending on the run). We report (i) average training time per epoch, (ii) total training time until convergence, and (iii) peak GPU/CPU memory consumption. For inference, latency is measured as the average wall-clock time to process a single text segment under batch size 1 (real-time setting) and batch size 32 (throughput setting), averaged over 1000 randomly selected segments. We report mean ± standard deviation latency (ms/segment) and throughput (segments/s). These measurements indicate whether the model can support interactive or near real-time classroom scenarios under typical deployment constraints.

The proposed BERT-GRU-DNN-DECOC architecture demonstrates a clear improvement over baseline approaches on EduEmoji-ECE, with statistically significant gains and stable training dynamics, supporting its suitability for context-aware emoji class recommendation in educational text.

5.2. Educator Feasibility Check

In the within-subject, counterbalanced comparison between the emoji-enhanced (AI-assisted, hybrid placement) and text-only versions, children showed higher time-on-task and faster response times in the emoji-enhanced condition (emoji present vs. no emoji) in our study setting. These comparisons are interpreted as exploratory and do not isolate the causal contribution of the AI placement mechanism.

Outcome definitions and measurement procedures (time-on-task, rubric-based engagement, immediate comprehension check, delayed retention probe, and educator/caregiver ratings) follow the protocol described in

Section 4.

A total of 100 early childhood learners participated in the classroom evaluation, with outcome ratings recorded through structured observations by five teachers and brief educator/caregiver questionnaires.

Survey findings revealed notable trends in emoji-enhanced learning engagement across different age groups.

Table 7 summarizes outcome levels (%) by age group in the emoji-enhanced condition.

In this sample, the 5–6 group showed the highest engagement and comprehension levels under the emoji-enhanced condition; given the exploratory design, this pattern should be interpreted descriptively rather than as evidence of differential effects by age.

We report descriptive learning progress over the four-week instructional period during which children were exposed to both emoji-enhanced and text-only versions (counterbalanced). Average scores increased from 58.2% (SD = 6.4) at baseline to 79.6% (SD = 5.8) at the end of the period. Because the study was not designed as a randomized controlled intervention isolating the effect of emojis (or the AI placement component), these pre/post changes should be interpreted as overall progress during the study period rather than as a causal effect of emojis.

Teacher observations indicated that children exhibited higher engagement levels when interacting with emoji-supported content. Time-on-task was recorded by educators using a simple timer from activity start to completion, excluding interruptions. For each child, time was logged separately for the emoji-enhanced and text-only versions and averaged across activities. On average, students spent 32% more time engaging with emoji-embedded materials compared to non-emoji text, suggesting that the visual enhancements captured and sustained their attention more effectively. These observations indicate that emoji-enhanced materials were associated with higher engagement in our study setting.

The reaction time assessment provided further insights into the cognitive impact of emoji-enhanced materials on learning efficiency. Reaction time was measured as the elapsed time from the educator finishing the comprehension prompt to the child’s correct response, recorded with a stopwatch. Times were collected after each version (emoji-enhanced vs. text-only) using equivalent prompts and averaged per child. Children who engaged with emoji-supported content responded to comprehension questions 19.4% faster (M = 4.3 s, SD = 0.8) than those who were exposed to text-only materials (M = 5.4 s, SD = 1.1). The reduction in response time suggests that emojis may support quicker interpretation of prompts in this setting.

The presence of visual cues may support faster interpretation of prompts in this setting; however, this feasibility evaluation does not establish causal effects. Across observation, time-on-task, and reaction-time measures, emoji-enhanced materials were associated with higher engagement and faster responding than the text-only version in our counterbalanced within-subject design. However, the study was not designed to isolate the causal contribution of the AI placement mechanism, and the measures are brief/pragmatic rather than standardized psychometric instruments; therefore, findings should be interpreted as exploratory.

6. Discussion

In this section, a discussion of the results through the theoretical lens is presented. The observed trends are consistent with prior work suggesting that emojis and other lightweight visual cues can support emotional expression, increase perceived social presence, and reduce ambiguity in text-based communication in learning settings. In particular, empirical findings on emoji use in online learning contexts indicate that emojis can act as affective signals that help learners communicate emotions and help instructors interpret learner state more efficiently, which aligns with our educators’ qualitative observations and the reported engagement-related indicators in our study setting [

29]. In addition, broader reviews of emoji usage in computer-mediated communication—including educational use cases—have reported that emojis may increase engagement and provide supportive contextual cues, while also highlighting the need for systematic and pedagogically grounded integration rather than decorative usage [

30]. From a system perspective, our contribution complements prior AI-in-education surveys emphasizing adoption constraints, ethical considerations, and practical deployment issues (e.g., transparency and feasibility) by providing a domain-specific dataset and a reproducible modeling pipeline for context-aware emoji recommendation [

19,

20,

21]. Finally, child-centered intelligent systems designed for socio-emotional learning (e.g., autism-related emotion recognition tools) further motivate the importance of carefully aligning visual cues with developmental constraints and educational intent, which is reflected in our annotation guideline and emoji-function mapping strategy [

18,

31]. Importantly, because the classroom evaluation in this work is exploratory and not designed as a controlled intervention study, these results should be interpreted as supportive evidence of feasibility and alignment with prior literature, rather than definitive causal proof of learning gains attributable specifically to the AI-driven placement mechanism. Specifically, although we included a within-subject text-only condition (same materials without emojis), the study was not a randomized controlled trial and did not include a human-placed emoji baseline. Therefore, observed differences between emoji-enhanced and text-only versions should be interpreted as exploratory associations and do not establish causal effects, nor do they isolate the contribution of the AI placement mechanism versus the presence of emojis in general. Instead, we position the model as a scalable, consistency-oriented tool that aims to approximate expert-defined placement rules and reduce manual authoring workload. Future work will include a three-condition comparison (text-only vs. human-placed vs. AI-placed) to evaluate any incremental benefit attributable to automation.

6.1. Exploratory Pedagogical Evidence

The observed associations (higher engagement indicators, higher comprehension checks, and faster response times in the emoji-enhanced condition) are consistent with multimedia learning and dual-coding principles: pairing short verbal segments with meaningful visual cues can help children select relevant information, reduce ambiguity in brief instructions, and create retrieval cues that support recall. In our setting, emojis operate as lightweight semiotic signals that support attention and interpretation when they are aligned with the instructional intent (reinforcement after success, prompting reflection in a question) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

30].

6.2. Computer Science Evidence

The strong predictive performance of the proposed model suggests that combining contextual embeddings with sequence modeling is effective for capturing pedagogically relevant cues beyond surface sentiment alone. This provides a practical alternative to ad hoc or purely heuristic emoji insertion, and supports the use of AI to maintain consistency in emoji use across large collections of learning materials.

In relation to prior work, our findings are consistent with reports that emojis can convey affect and improve engagement in online learning interactions, and they respond to calls in the literature for more structured, theory-informed uses of emojis in education. Compared with studies that analyze emoji usage patterns in general communication or in older learner groups, this work contributes a dedicated ECE dataset and explicitly models pedagogical intent, which is a key requirement when designing learning supports for young children.

Threats to validity include the limited emoji inventory, potential cultural differences in emoji interpretation, and the fact that outcomes for very young learners rely on teacher observation and proxy measures rather than self-report.

The integration of AI-assisted learning tools in early childhood education raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding data privacy, potential algorithmic bias, and the impact of AI-driven decisions on cognitive and emotional development. Ensuring fair representation across diverse cultural contexts is essential, as sentiment analysis models may exhibit biases in emoji recommendations, influencing children’s perception of emotions. Future work should explore privacy-preserving AI techniques and cross-cultural validation to enhance the fairness and adaptability of AI-driven learning systems. In this study, the dataset contains educational text only and the classroom outcomes were recorded in anonymized, aggregated form without audio/video recordings; nevertheless, future deployments should continue to prioritize privacy-by-design and bias auditing.

A key limitation is that emoji semantics and pedagogical appropriateness may vary across languages and socio-cultural contexts; consequently, performance may degrade under domain shift (different curriculum style, different language structure, or different emoji conventions). The model may require re-annotation and calibration when deployed in new cultural settings, including updates to the emoji inventory and label definitions. Future work will evaluate multilingual training (e.g., multilingual encoders), cross-site annotation, and transfer learning with locally sourced ECE materials to quantify and improve generalizability.

Future work will expand the emoji set, include multilingual and cross-cultural validation, and assess long-term learning effects through longitudinal designs and controlled classroom trials.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes an AI framework for expert-aligned, scalable emoji label prediction for early-childhood educational text and validates it on the EduEmoji-ECE corpus. The computer science evaluation shows that the BERT–GRU–DNN–DECOC model can accurately reproduce expert annotations and outperform baseline models on emoji prediction. In addition, an exploratory classroom-oriented evaluation suggests that emoji-enhanced materials were associated with positive engagement and comprehension indicators; however, because the evaluation was not a randomized controlled trial and did not include a human-placed emoji baseline, these observations do not support causal claims and do not isolate the incremental effect of the AI placement mechanism versus emojis in general. Importantly, the classroom evaluation assesses the effect of emoji recommendation in the learning materials; it does not claim that the predictive model itself caused learning gains beyond expert-designed content.

Across the reported measures, emoji-enhanced materials were generally perceived as supportive for attention and emotional tone, and descriptive pre-/post-comparisons reflected overall learning progress during the study period, which should not be attributed to emojis or the AI placement mechanism. Age-group differences are reported descriptively and require confirmation with larger samples and controlled designs. The materials used and evaluation conducted were in English within Saudi Arabia, though emoji interpretation may vary across cultures; therefore, generalizability to other linguistic and socio-cultural settings should be considered a key limitation.

The classroom evaluation is exploratory and does not employ a randomized controlled design; thus, observed improvements cannot be attributed uniquely to the AI-driven placement mechanism. The study also uses a limited emoji inventory and is based on a specific linguistic/curricular context, which may affect generalizability under cultural or domain shift. Future work will adopt controlled experimental protocols (e.g., randomized assignment where feasible and three-condition comparisons: text-only vs. expert-placed emojis vs. AI-placed emojis), expand the emoji set, and evaluate cross-cultural and multilingual transfer.

Future work will expand EduEmoji-ECE across additional subjects and contexts, incorporate stronger experimental controls, and evaluate cross-cultural and multilingual robustness, including updating the emoji inventory and annotation guideline when deployed in new settings. We will also further examine efficiency and real-time feasibility through the systematic reporting of training cost and inference latency.