1. Introduction

Public transport (PT) systems are central to urban mobility and play a critical role in promoting social inclusion, reducing car dependency, and supporting sustainable city development. Beyond providing mobility, PT systems shape access to employment, education, healthcare, and other essential services, making them a key concern in debates on transport equity and justice [

1]. Evaluating these outcomes requires more than knowledge of where services exist or how frequently they operate. It requires trip-level evidence capturing travel time, transfers, walking distance, and service availability across different times of day [

2,

3,

4]. Such measures are fundamental to understanding whether transport systems serve diverse population groups equitably and support broader sustainability and climate resilience goals, as articulated in established accessibility and transport justice frameworks. In accessibility research, these concerns are commonly conceptualised through multi-dimensional frameworks that consider transport supply, land use context, temporal constraints, and individual characteristics [

1,

2].

The General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) has become a foundational dataset for public transport research by providing a standardised representation of routes, schedules, and service calendars [

5,

6]. GTFS enables large-scale comparisons of service provision, but its static nature has led many studies to rely on simplified indicators such as route density or service frequency [

7,

8]. Recent research has demonstrated that simulating complete passenger journeys yields richer insights into accessibility, particularly when accounting for transfers, walking links, and temporal variation [

9,

10,

11]. However, these approaches depend on routing platforms that are not only accurate, but also scalable, open, and suitable for automated analysis, in order to support consistent accessibility assessment across multiple spatial and temporal dimensions.

Commercial journey planning services such as Google Maps or Apple Maps provide highly accurate routing for individual users. Despite this, they are poorly suited to large-scale accessibility research or policy evaluation. Licensing restrictions, rate limits, and prohibitions on bulk access prevent their systematic use for city-wide or multi-city analysis [

12]. This limits transparency and reproducibility, particularly for public interest studies that require consistent, repeatable extraction of routing outcomes.

OpenTripPlanner (OTP) offers an open-source alternative designed for multimodal journey planning using GTFS and OpenStreetMap (OSM) data [

13,

14]. Unlike proprietary platforms, OTP exposes both a web-based interface and a programmatic API, enabling large-scale simulation of origin–destination (O–D) trips. Compared with tools such as R5 (

https://github.com/conveyal/r5.git (accessed on 15 December 2025)), which are primarily oriented toward local or offline analysis, OTP supports public-facing access and integration into shared research infrastructure. This makes it particularly relevant for researchers, public agencies, and interdisciplinary teams seeking to analyse transport accessibility without developing routing systems from scratch.

Despite these advantages, deploying OTP as a publicly accessible, multi-city service introduces practical challenges. Running a routing platform across multiple urban regions requires careful consideration of computing resources, system stability, and user concurrency. These challenges are especially pronounced in federated data environments, where transport feeds are managed independently across jurisdictions. For many organisations, including those in public health, education, or urban policy, the technical burden of hosting and maintaining such systems remains a significant barrier.

This study addresses these challenges through a feasibility assessment of a public, multi-city OTP deployment, motivated by the need for transparent and reproducible accessibility evidence that can support equity-oriented transport analysis. Using Australia as a case study, where GTFS data is released separately by state agencies, we evaluate the viability of a multi-router architecture that enables consistent routing across multiple metropolitan regions within a single platform. The study focuses on questions of scalability, geographic coverage, and performance under concurrent public access, contributing a reusable research platform for accessibility and equity oriented transport studies. The contributions of this paper are threefold:

We present a generalisable, open-source routing platform based on OpenTripPlanner that supports multi-city operation in federated GTFS environments.

We demonstrate an approach for automated extraction of O–D itineraries using a publicly accessible, API-driven platform suitable for large-scale accessibility analysis.

We evaluate system performance under concurrent load to assess the feasibility of deploying open-source routing infrastructure for public and institutional use in accessibility and equity-oriented transport studies.

While demonstrated using Australian metropolitan areas, the proposed approach is applicable to other regions characterised by fragmented transport data governance.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related works on public transport accessibility studies and data collection techniques.

Section 3 presents the OTP multi-router architecture and its design for supporting Australian metropolitan networks.

Section 4 outlines the data preparation and deployment strategy used to build and operate the platform.

Section 5 presents the results of route validation, coverage analysis, and server performance.

Section 6 discusses the methodological implications, limitations, and practical considerations.

Section 7 concludes the paper and highlights directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Public transport accessibility has traditionally been examined using static datasets, with the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) becoming a widely adopted global standard. Many studies have employed GTFS to assess service frequency, stop coverage, and timetable availability, particularly in dense urban environments [

2,

5,

15]. While these indicators provide an important baseline, they often abstract away the passenger’s full journey experience, especially for trips involving transfers, walking links, or multiple modes. As a result, such approaches have limited capacity to capture user burden and equity-relevant dimensions of accessibility [

1,

10].

To address these limitations, a growing body of research has integrated transport data with demographic and socio-economic variables to examine equity-oriented outcomes. These studies aim to identify communities underserved by public transport and to reveal disparities across income, age, or geographic location [

6,

16,

17]. However, many equity-focused analyses still rely on simplified spatial proximity or service frequency measures, rather than simulating complete passenger journeys. Moreover, few provide transparent and reproducible workflows that support systematic comparison across cities or jurisdictions, limiting their ability to operationalise established accessibility and transport justice frameworks in large-scale empirical settings.

Another strand of work has attempted to overcome data fragmentation by extracting routing information from commercial or third-party platforms such as Google Maps or OpenStreetMap-based services [

18,

19]. Although these platforms offer accurate and user-friendly trip planning, their use in large-scale research is constrained by licensing conditions, rate limits, and restrictions on bulk data extraction [

12]. The proprietary nature of their routing algorithms further limits transparency and reproducibility, reducing their suitability for policy evaluation or public accountability.

In response to these constraints, data scraping has been used as a workaround to collect itinerary-level transport data [

20,

21]. When applied cautiously, scraping has supported empirical studies of travel behaviour and service accessibility [

22]. However, this approach raises significant ethical, legal, and methodological concerns, including uncertain reproducibility, potential licensing violations, and dependence on unstable platform interfaces. These challenges highlight the need for open, auditable, and scalable routing infrastructures that can support research and policy analysis without reliance on opaque or restricted services.

Open-source routing engines such as R5 and OpenTripPlanner (OTP) have been developed to meet this need. R5 is optimised for high-speed batch processing and offline accessibility analysis [

11], but does not support remote APIs or public-facing interfaces. OTP, by contrast, integrates GTFS and OpenStreetMap data through an API-driven architecture, enabling both interactive and programmatic access. Previous studies have used OTP for city-level accessibility analysis [

14,

23,

24], yet there has been limited investigation into its scalability and deployment for national or federated transport systems.

Moreover, few studies provide transparent and reproducible workflows that support systematic comparison across cities or jurisdictions, limiting their ability to operationalise accessibility and transport justice frameworks at scale. From an accessibility perspective, many existing approaches emphasise land use proximity or service frequency, while simplifying transport performance and temporal variation. Less attention has been given to how routing infrastructure itself enables consistent and repeatable analysis across transport and temporal dimensions of accessibility, particularly in federated data environments. This study addresses this gap by examining the feasibility of a reproducible, open-source routing platform based on OTP’s multi router capability.

OTP version 1.5 supports concurrent routing across multiple independent GTFS and OSM datasets within a single deployment, making it well suited to federated transport environments such as Australia, where no unified national GTFS feed exists [

25]. Although later OTP versions promote microservices-based architectures, these approaches introduce additional complexity through container orchestration, reverse proxying, and infrastructure management, which may present barriers for non-technical users and smaller institutions. By adapting a multi-router OTP architecture, this work aims to support transparent and repeatable accessibility analysis across multiple jurisdictions while maintaining manageable deployment complexity. This approach provides a practical foundation for integrating accessibility and transport equity frameworks into large-scale empirical studies.

3. OTP Multi-Route Architecture

This study used OpenTripPlanner (OTP), a free and open-source routing tool developed to generate realistic public transport journeys that can include buses, trains, walking, and cycling [

13,

14]. OTP was selected because it offers full control over routing behaviour, does not rely on commercial licences, and can be accessed programmatically through a public API. These features are important for supporting open, repeatable transport research. From a research design perspective, OTP enables systematic and auditable journey simulation across multiple cities, which is essential for comparative accessibility and equity analysis.

3.1. Why Multi-Router Architecture

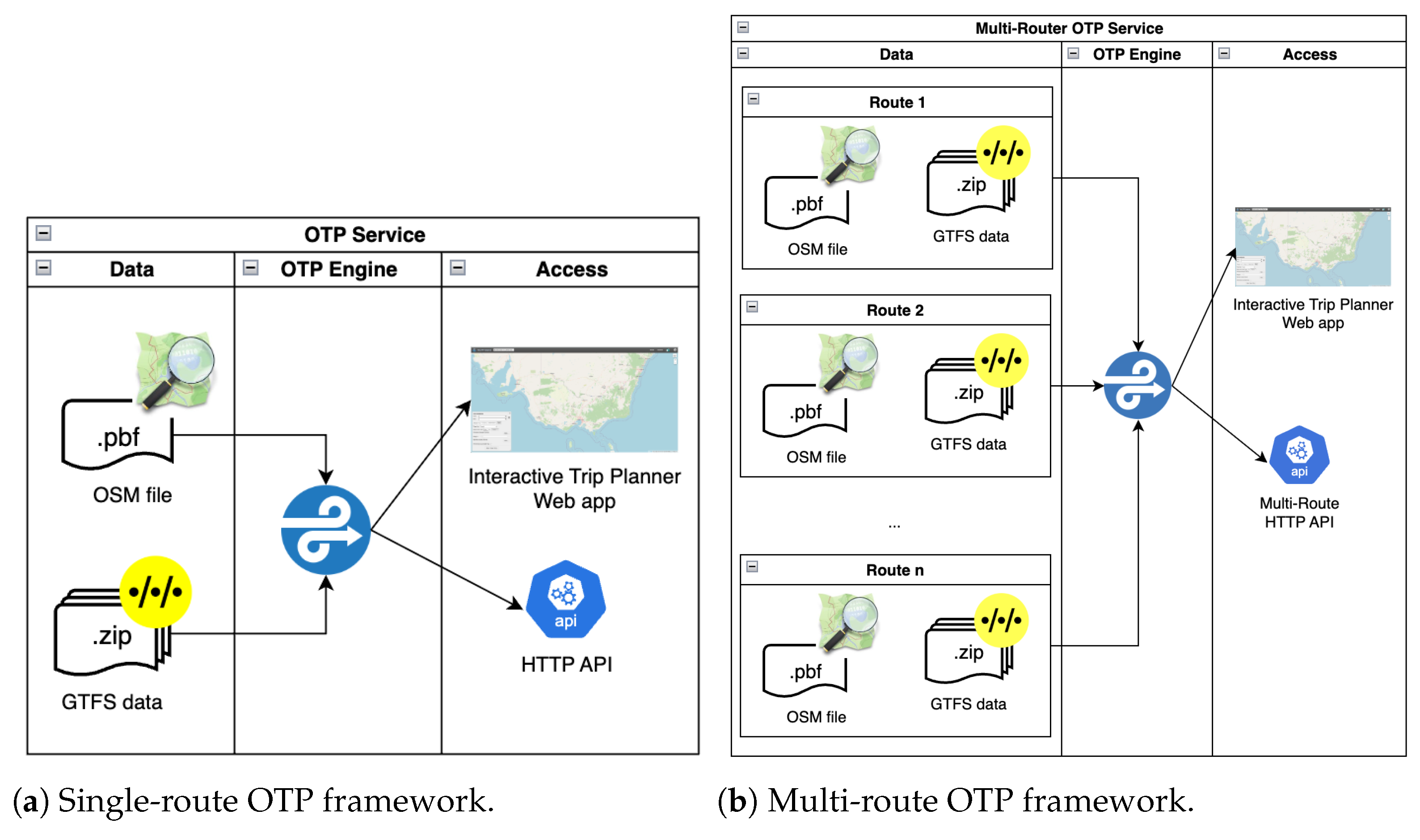

In most default setups, OTP is used in what is called a single-router mode. In this case, the system builds a routing graph from a single General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) and OpenStreetMap (OSM) dataset, which typically represents one city or region. This setup works well when the data comes from a single source, but it becomes limiting in countries like Australia where each state or territory publishes its own GTFS feed.

To address this, the platform adopted a multi-router setup, which allows several cities to be processed and queried independently. OTP version 1.5 was selected because it supports this architecture. In newer versions, the feature is no longer maintained. The chosen version allows the platform to host each city under its own routing configuration while still running on a shared server. This design choice was driven by the need to support cross-city comparison in a federated data environment, where GTFS feeds are published independently by regional authorities.

Figure 1 shows the difference between single-router and multi-router systems. Each version uses the same components: transit data, map data, a routing engine, and a user access point. In multi-router mode, the routing engine builds separate graphs for each city, and these are accessed through different API endpoints. Although the map interface is limited to one city view at a time, the API can be used for all configured cities.

3.2. Data and Routing Setup

OTP depends on two open datasets. The first is GTFS, which provides details about transport schedules, stop locations, and route patterns. The second is OSM, which contains the road network and pedestrian paths needed to connect these stops. Each city’s GTFS feed was combined with a matching OSM extract. The platform prepared specific configuration files for each router to define how these datasets were handled, including rules for transfers and trip planning options.

After all data and settings were ready, the routing graphs were built separately for each city. The server was then launched with the full set of routing graphs available for public access.

3.3. Public Access and Use Modes

The deployed server can be accessed in three ways. First, users can plan a trip using a built-in map through a web browser. Second, researchers can use the HTTP API to submit automated requests, such as testing multiple origin–destination (O–D) combinations. Third, for high-volume scraping tasks, the platform can read a file of O–D pairs and return results in structured files such as JSON. The same platform was used to test all three scenarios.

The public server is hosted at

https://ptplanner.latrobe.edu.au (accessed on 1 August 2025) and supports route planning for eight metropolitan areas in Australia. Each region has its own API path, such as

/otp/routers/vic/plan for Victoria or

/otp/routers/nsw/plan for New South Wales. No login is required, and users are not expected to install OTP or set up datasets themselves. This design allows both technical and non-technical users to explore routing options and simulate transport patterns across the country.

4. Data Preparation and Deployment Strategy

Reliable and comparable routing analysis depends not only on routing algorithms, but also on how spatial and timetable data are prepared and aligned across regions. In this study, data preparation was guided by three methodological objectives. First, routing results must remain reproducible across all metropolitan areas despite differences in data providers and network scale. Second, the system must operate within realistic computational constraints so that it can be deployed on modest institutional infrastructure. Third, preparation choices must support fair cross city comparison by ensuring that observed differences reflect transport network structure rather than artefacts of data extent or validity.

Rather than documenting implementation procedures, this section explains the design logic behind the preparation of spatial and timetable data used to build the routing graphs. Detailed configuration files and deployment artefacts are provided in the

Supplementary Materials to support reproducibility.

4.1. Spatial Data Preparation

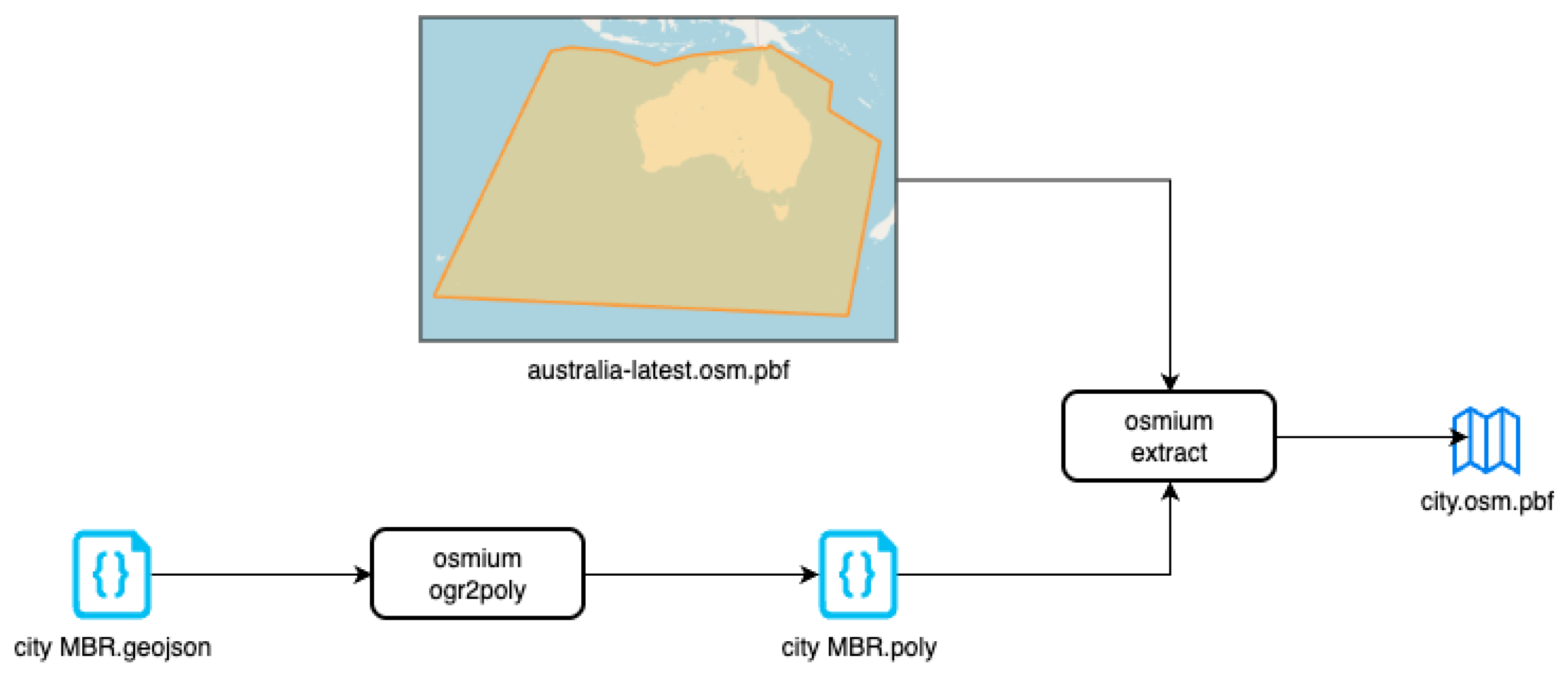

OpenStreetMap (OSM) was selected as the base spatial dataset because it is openly available, continuously updated, and widely used in accessibility and transport research. OSM provides the pedestrian and street level connectivity required to model walking access to public transport stops and transfers between services.

To ensure consistent modelling across cities, spatial data were trimmed to metropolitan boundaries prior to graph construction. This decision serves both computational and analytical purposes. From a computational perspective, trimming reduces graph size, build time, and memory requirements, enabling multi city deployment on shared infrastructure. From an analytical perspective, consistent spatial extents prevent routing artefacts that can arise when long distance or irrelevant road segments influence pathfinding outcomes.

All cities were processed using the same trimming workflow so that differences in routing coverage reflect underlying transport network characteristics rather than variations in map extent. This approach also supports equity oriented analysis by keeping the modelling focus on areas where residents can reasonably access public transport on foot.

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial trimming workflow applied uniformly across all metropolitan areas.

4.2. Timetable Data Preparation

Public transport services were modelled using General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) data. All GTFS feeds were obtained from the Mobility Database [

26], which provides a transparent and reproducible source of transit data.

A key methodological challenge arises from the federated nature of public transport governance in Australia. Each state or territory publishes GTFS data independently, with differing update cycles and validity periods. Without harmonisation, a routing request that is valid in one city may fail in another, undermining reproducibility and comparability.

To address this issue, all GTFS feeds were aligned to a shared validity window spanning January 2025 to June 2026. This harmonisation does not attempt to represent real-time operations. Instead, it establishes a consistent temporal baseline that allows routing behaviour to be compared systematically across cities using the same assumptions. The selected window balances practical maintenance considerations with the need to reflect contemporary service patterns. The platform is designed so that GTFS feeds can be updated on a regular basis, for example annually, to support ongoing research use.

This approach has known limitations. A unified calendar may not capture temporary service disruptions, seasonal variations, or special event services. Some GTFS feeds may also omit specific modes or feeder services. These limitations do not invalidate the multi router approach, but they clarify that the platform represents scheduled service availability rather than operational performance.

Table 1 summarises the GTFS providers and validity periods used for each metropolitan area.

4.3. Routing Graph Characteristics

After spatial and timetable data were prepared, routing graphs were built independently for each metropolitan area. Graph size and build time vary substantially across cities due to differences in geographic extent, population density, and transport network complexity.

Table 2 reports the size of the prepared input datasets, graph build time, and structural characteristics of each routing graph. These metrics provide insight into the computational effort required to maintain a multi city platform and also help explain differences observed in routing coverage and performance results.

Larger graphs such as those for New South Wales and Victoria reflect dense, multimodal networks, while smaller graphs correspond to cities with more limited public transport provision. These structural differences influence both routing coverage and system performance, as discussed in

Section 5. The observed build times also reinforce the importance of spatial trimming, since unbounded OSM inputs would substantially increase memory usage and processing time.

4.4. Deployment Considerations

The routing platform was deployed on an institutional virtual machine with 8 CPU cores and 24 GB of RAM. This configuration was selected to reflect realistic hosting conditions available to universities and public sector organisations, rather than optimised commercial infrastructure.

Despite these modest resources, the platform was able to support eight concurrent routing graphs and sustained public access. This demonstrates that reproducible, multi city routing analysis can be achieved without specialised hardware, provided that data preparation and graph management are carefully designed. From an equity and policy perspective, shared institutional hosting can reduce barriers for research groups and agencies that lack dedicated technical infrastructure, supporting wider uptake of transparent and reproducible transport analysis.

Detailed deployment artefacts, API specifications, and user interfaces are documented in the

Supplementary Materials. Their separation from the main text ensures that methodological reasoning remains the focus of this section while preserving full reproducibility.

5. Feasibility Results

This section presents three sets of results that demonstrate platform feasibility for reproducible routing analysis. These include the route correctness outputs from OTP compared to Google Maps, area coverage analysis across eight Australian metropolitan areas, and system performance benchmarks under different levels of concurrent access.

5.1. Route Validity Assessment

A series of commuter trips were simulated to evaluate the validity of routing outputs produced by the OTP platform. Each trip represents a typical journey from the central business district (CBD) of a capital city to a major university, scheduled for 8:00 AM on Wednesday, 24 September 2025.

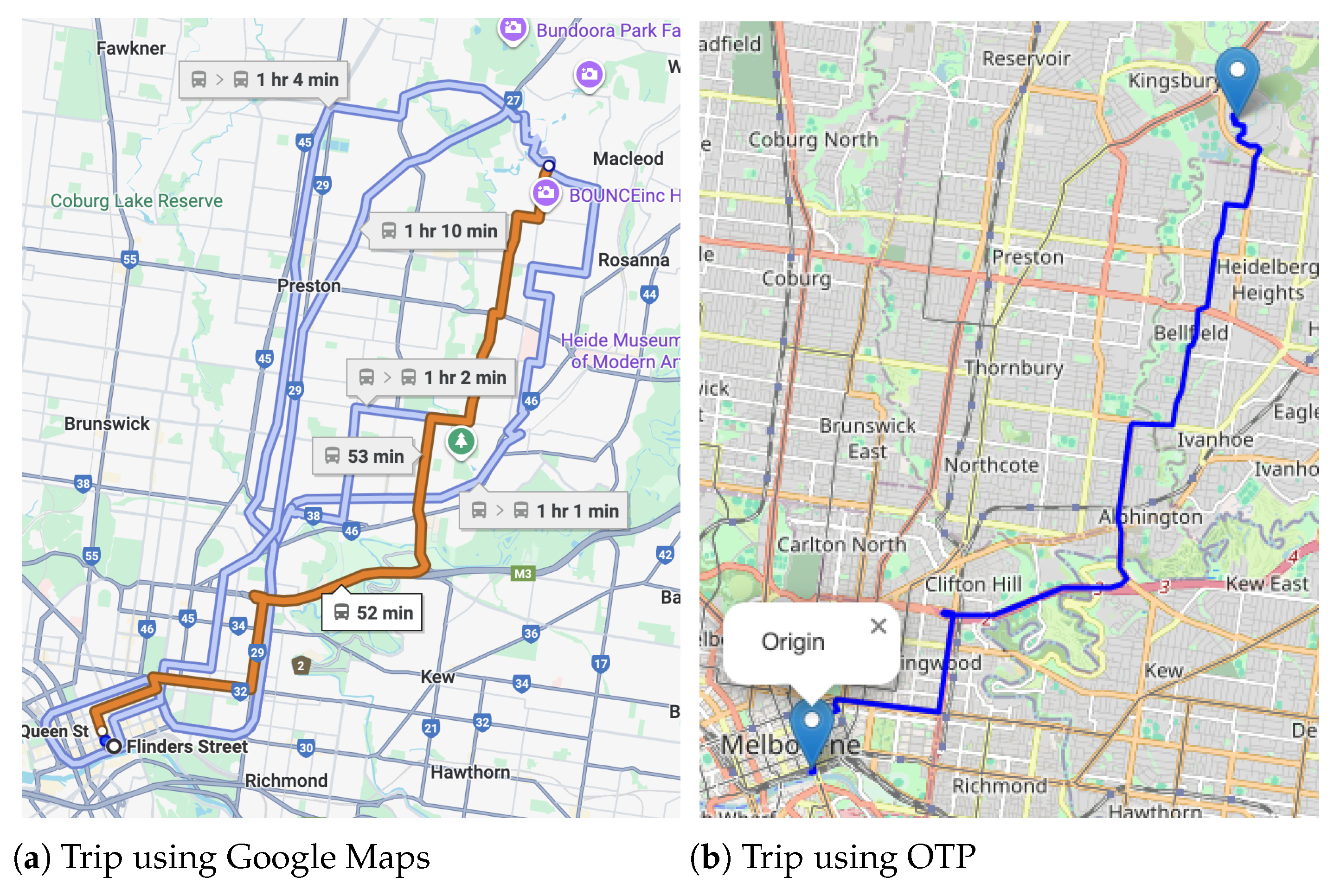

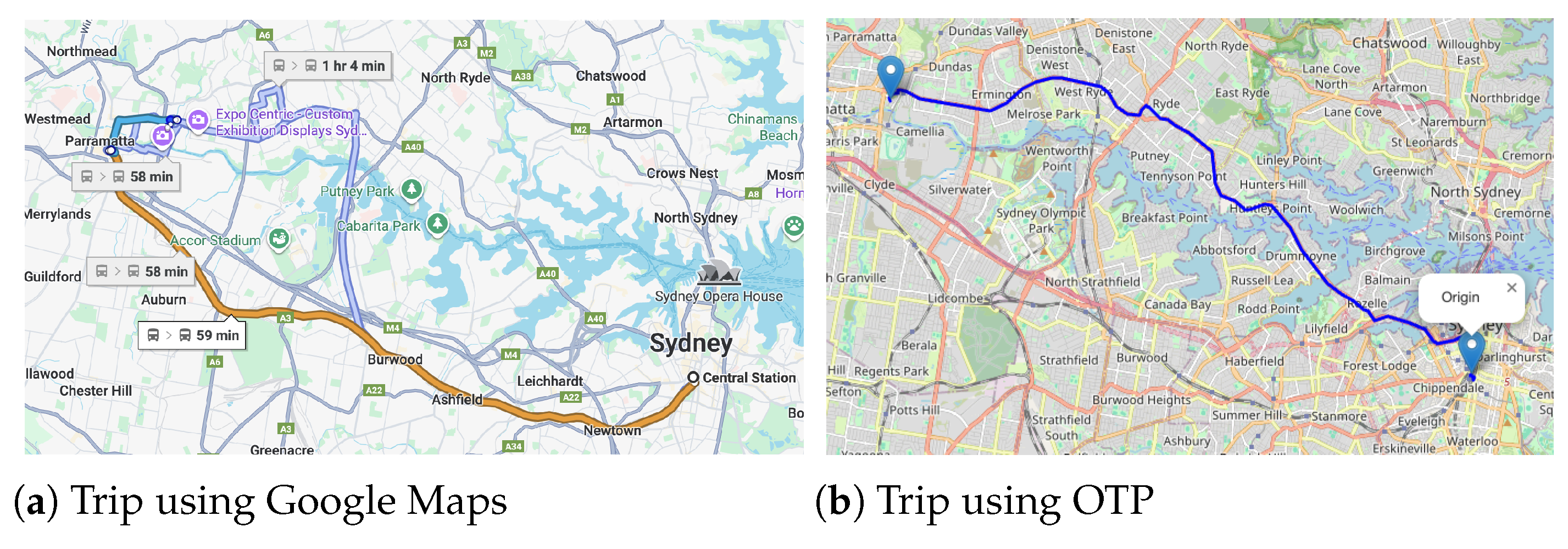

The same origin and destination coordinates were used to query both the OTP server (ptplanner.latrobe.edu.au) and Google Maps. While Google Maps typically provides multiple route alternatives based on live and historical traffic data, OTP generates only a single route derived from static GTFS and OSM inputs.

Table 3 provides an overview of the eight test trips. The routing results obtained from OTP and Google Maps are shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5, respectively. These include the trip distance (where available), travel time, and the transport modes used. Please note that if the data is not available, it is marked as N/A (Not Available).

Although both platforms returned usable routes for all test cases, observable differences in travel times and selected transport modes were found. From a research and policy perspective, these differences are not treated as accuracy errors, because the two systems serve different purposes. Google Maps is designed to optimise the user experience using proprietary data and heuristics, while OTP provides a transparent model that can be repeated across cities using the same inputs and assumptions. This transparency matters when evaluating accessibility and equity, because it enables consistent comparisons across neighbourhoods and time periods, and it allows public and research users to explain how routing results were produced. In several cities, OTP returned longer trip durations and fewer intermodal options compared to Google Maps. This reflects the limitations of static data routing, where real-time service changes or optimisation layers are not included.

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 visualise the route paths for Melbourne and Sydney. These differences reflect the underlying design of each platform. While Google Maps offers adaptive routing based on real-time conditions, its proprietary nature limits transparency and reproducibility. In contrast, OTP prioritises methodological consistency and auditability, which are important for comparative accessibility analysis across multiple jurisdictions. As a validation method, this evaluation shows that OTP provides structurally correct and reproducible routing outcomes, suitable for static-schedule modelling and batch analysis. Further reflections on implications and limitations are discussed in

Section 6.

5.2. Area Coverage Results

To assess geographic coverage, a large-scale routing test was conducted using meshblock-level residential centroids. For each city, one-way trip plans were generated from every residential meshblock to the CBD centroid using the WALK,TRANSIT travel mode. All trips were scheduled for 8:00 AM on Monday, 15 September 2025.

In total, 158,779 trip plans were submitted across eight capital cities.

Table 6 summarises the number of successful and failed route responses per city. A failure refers to cases where no valid itinerary could be generated by OTP under the specified constraints, typically due to missing service coverage, disconnected network components, or schedule limitations in the GTFS feed. Most cities achieved high success rates above 90%, with Canberra and Sydney exceeding 99%. Lower coverage was observed in Darwin and Brisbane, suggesting possible gaps in GTFS availability or street network connectivity in those regions.

This coverage test provides a useful indication of the practical usability of the OTP platform for regional scale accessibility analysis. It also highlights an equity relevant issue: when routing fails systematically in particular areas, those places become difficult to represent in journey based evaluations, which can mask transport disadvantage in peripheral or low service neighbourhoods. In this sense, coverage is not only a technical metric, but also a prerequisite for fair and transparent accessibility assessment.

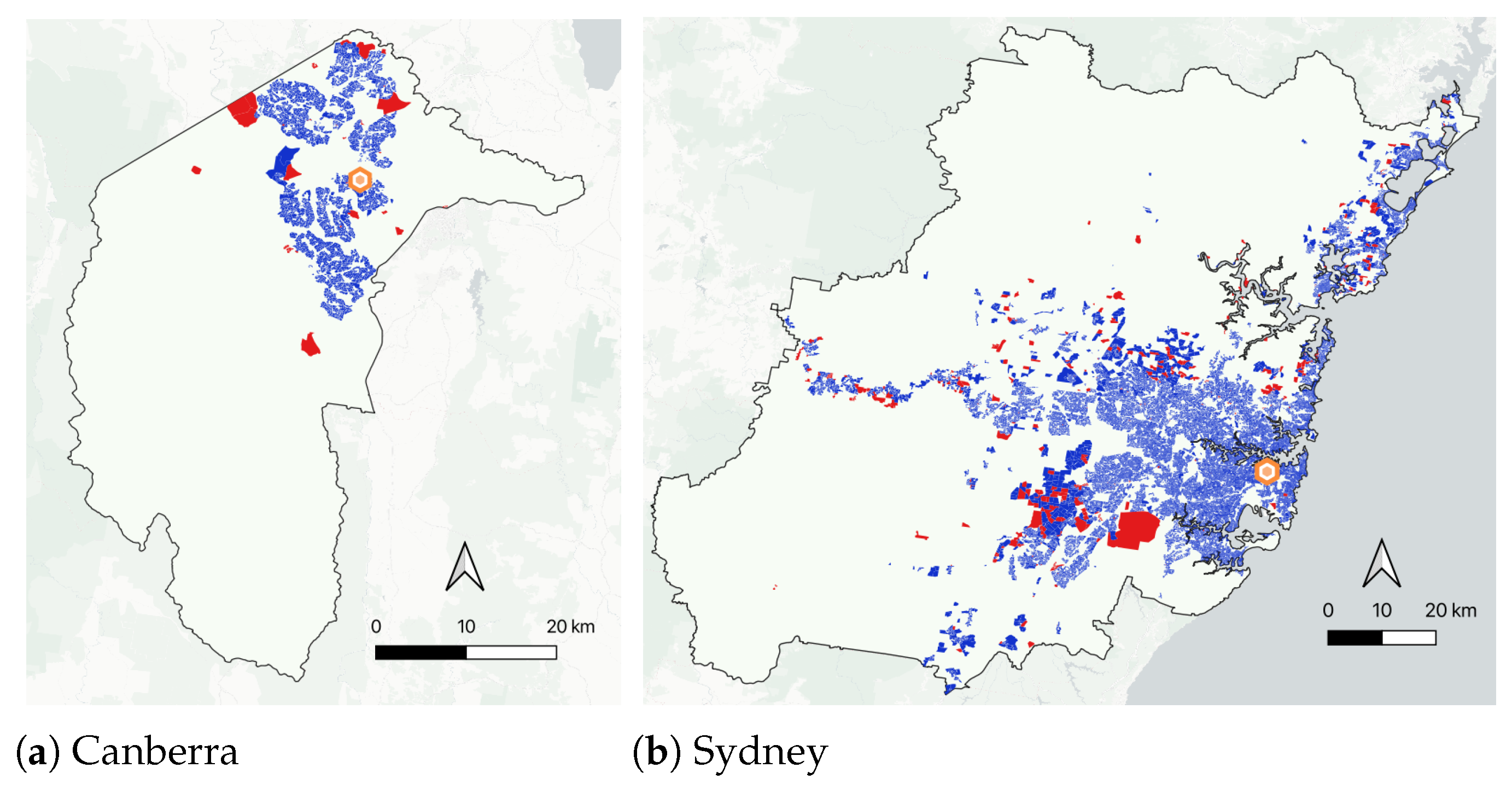

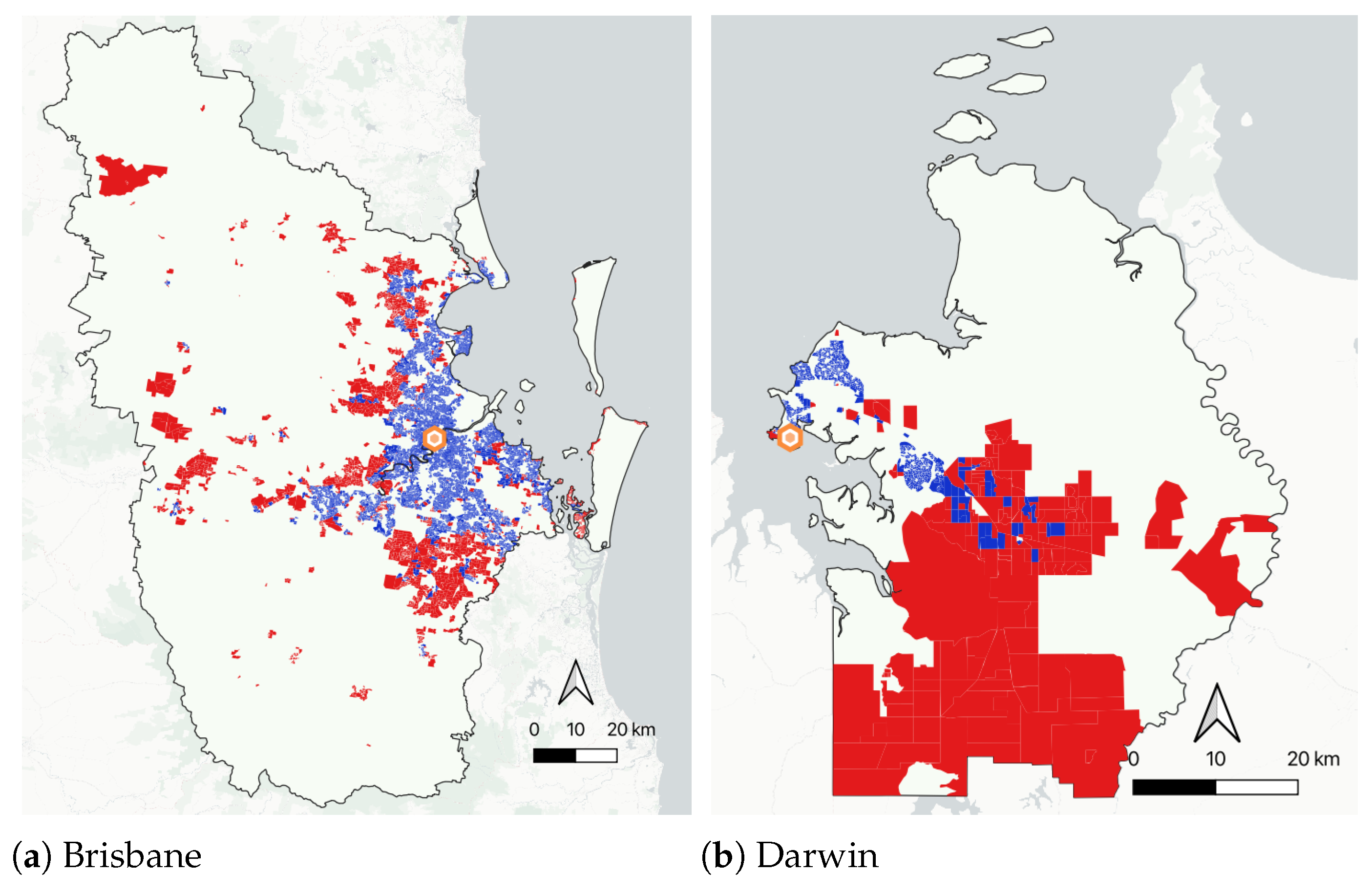

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the spatial distribution of successful (indicated by blue area) and failed (indicated by red area) routes to CBD (indicated by target icon)in selected cities. Canberra and Sydney show comprehensive coverage, while Brisbane and Darwin exhibit significant gaps, particularly in outer suburban areas. These patterns likely reflect differences in PT network density, service frequency, population distribution, and geographic constraints. From an equity perspective, these gaps suggest that residents in the affected areas may face weaker public transport access to employment, education, and essential services, at least under the scheduled services represented in the available GTFS feeds.

5.3. System Performance Results

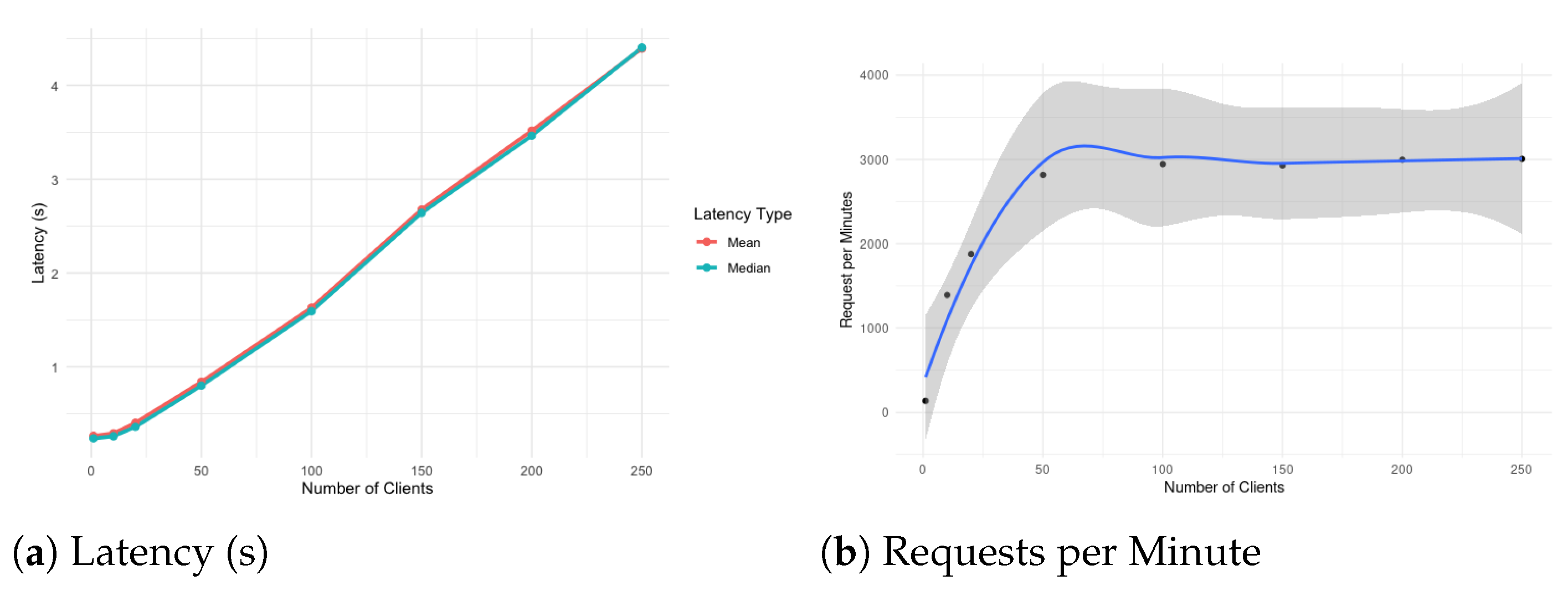

To evaluate server responsiveness under load, a series of automated stress tests were performed using Python 3.12.4 clients simulating multiple users. Each test ran for two minutes, during which each client submitted routing requests at defined intervals. The number of concurrent clients varied from 1 to 250. The server was hosted on an 8-core VM with 24 GB RAM and OTP allocated 16 GB.

Key metrics collected include:

Table 7 reports average server performance across multiple runs under varying concurrency levels. As expected, throughput increased with the number of clients and gradually plateaued at around 3000 requests per minute, indicating saturation of server-side processing capacity. Response latency rose correspondingly under higher load, increasing from well below one second at low concurrency to over four seconds at the highest tested level. In addition to mean and median latency, standard deviation is reported to characterise response time variability. While variability increased with higher concurrency, median values remained close to the mean across all test cases, suggesting a largely symmetrical latency distribution without dominant outliers. Overall, the results indicate stable system behaviour under stress, with variability consistent with normal fluctuations expected for a publicly accessible API operating over external network conditions.

These performance metrics matter because large-scale accessibility studies often require millions of routing queries, for example when evaluating many origin–destination pairs across neighbourhoods and times of day. Throughput affects how long such studies take to complete, while latency affects whether interactive public tools remain usable during peak demand. From an institutional perspective, predictable performance supports use by universities, agencies, and NGOs for repeatable analysis workflows and transparent reporting.

A small failure rate of 0.05% was observed at 20 concurrent clients, corresponding to occasional request timeouts under peak load rather than persistent routing or server errors.

A benchmark was also conducted on a MacBook Air M2 with 12 GB RAM to evaluate local deployment performance.

Table 8 shows reliable operation up to 20 concurrent clients, where median latency remains low and variability is moderate. Beyond this threshold, both latency and its standard deviation increase sharply, and failure rates rise significantly at 50 concurrent clients and above.

These results indicate that local performance is strongly influenced by available CPU resources and background system activity. While the platform is suitable for lightweight local use and development testing, concurrent workloads quickly compete with other processes on a personal device. As a result, high-volume or sustained workloads require dedicated server environments and appropriate scaling strategies to ensure stable performance. This also suggests that shared institutional hosting can lower barriers for research groups who lack dedicated hardware, supporting wider access to reproducible routing data.

6. Discussion

This discussion interprets the findings of the feasibility study through an accessibility perspective, in addition to technical performance considerations. Beyond demonstrating that the platform can generate valid routes and operate reliably under load, we examine how the system can support accessibility analysis using established conceptual frameworks. In particular, we reflect on the results using Geurs and van Wee’s accessibility framework, which distinguishes transport, land use, temporal, and individual components. This perspective allows us to clarify which dimensions of accessibility are supported directly by the platform, which are partially represented, and can be incorporated through integration with external datasets, such as socio-economic indicators, land use information, or demographic data. By situating the technical results within this framework, the discussion highlights how an open, reproducible routing platform can contribute to equity oriented transport research and evidence-based planning.

6.1. Route Validity and Coverage Analysis

The OTP-based trip planner returned valid and reasonable routes for all eight metropolitan scenarios tested, simulating typical commuter trips from city centres to universities. The outputs aligned well with public transport expectations in each area, confirming that OTP performs reliably when supported by accurate GTFS and OSM data.

A comparison with Google Maps was conducted to offer an external point of reference. While both platforms produced usable routes, minor differences were observed in route composition and travel time. Google Maps often suggested slightly faster or more integrated options, particularly for cases that involved a combination of rail and bus. These variations stem from Google’s ability to incorporate live traffic data and historical travel patterns—features that are beyond the scope of an offline platform such as OTP.

It is important to note that OTP was not designed to replicate real-time routing behaviour. Instead, it offers a consistent, reproducible, and transparent routing environment based solely on static datasets. This design choice makes OTP especially suitable for research and large-scale evaluations, where repeatability and control over variables are critical.

In terms of coverage, the spatial distribution of successful (blue) and failed (red) routing outcomes across selected cities revealed important insights. Canberra and Sydney achieved high coverage, with most origin points successfully reaching the CBD. In contrast, Brisbane and Darwin exhibited noticeable gaps, especially in outer suburban areas where failures were more frequent. The absence of valid routes may indicate areas with limited or fragmented public transport options under the available schedules. This highlights one of the strengths of the OTP-based system: it can help identify regions underserved by transit networks, offering valuable insights for transport planners and policy makers seeking to improve service equity.

Overall, OTP produced reliable and comparable routing results across different contexts. While it does not offer real-time enhancements, its performance demonstrates that high-quality offline routing remains a viable and valuable tool for transport planning and accessibility analysis.

6.2. System Performance and Scalability

To understand which factors most influenced system performance, we examined the relationship between key variables from the stress test. These variables include the number of concurrent clients, successful and failed requests, throughput (RPM), and both mean and median latency. A Spearman correlation analysis was used, as some variables did not follow a normal distribution.

Figure 7 shows the resulting correlation matrix.

The most influential factor affecting performance was the number of concurrent clients. Both mean and median latency demonstrated a strong positive correlation with client load (

), indicating that response time increased almost linearly as the number of clients grew. This trend is clearly visible in

Figure 8a, where latency rises predictably with each increment in concurrent users. Latency remained below 1 s for up to 50 concurrent clients, suggesting an acceptable response time for most public-facing applications. Beyond this point, latency increased rapidly, reaching 4.4 s at 250 clients. This behaviour highlights the trade-off between concurrent load and responsiveness.

In contrast, throughput (measured in RPM) scaled efficiently with load. RPM improved from 134 (with 1 client) to approximately 3000 at 250 clients, with no significant failures observed. As shown in

Figure 8b, the throughput curve flattens beyond 100 clients, suggesting that the server had reached a resource saturation point. Despite this, it consistently maintained high RPM levels even at the maximum tested load, demonstrating robust handling capacity. In this figure the grey shading represents the confidence interval around the smoothed trend, the black dots represent the average requests per minute at each concurrency level, and the blue line shows the overall trend of average requests per minute as the number of concurrent clients increases.

Interestingly, the number of failed requests remained minimal across all test cases, and showed no strong correlation with other variables. This highlights the stability of the deployment under load, although performance (in terms of speed) did degrade predictably with scale.

We note that successful and failed request counts are complementary by definition and are therefore not interpreted in relation to each other. Instead, the correlation analysis is used to highlight the dominant role of latency and throughput in shaping system performance under stress. The observed weak correlation reflects the fact that failures were rare and occurred only when the system approached saturation, rather than increasing proportionally with successful requests. As a result, no mechanically strong negative association emerges.

Overall, these results show that the system can support a high volume of concurrent requests with reliable throughput, while latency should be considered when determining the appropriate deployment scale. This analysis also offers a practical baseline for infrastructure planning in similar public deployments. For institutions planning to offer similar public-facing services, these results provide practical guidance on server capacity planning and highlight the importance of resource provisioning in supporting concurrent routing requests. From an accessibility research perspective, this scalability is essential for analysing large numbers of origin–destination pairs across cities, neighbourhoods, and time periods in a consistent manner.

6.3. Accessibility Impact Through the Four Components Framework

To interpret the practical value of the platform beyond technical performance, the results are examined through the four-component accessibility framework proposed by Geurs and van Wee [

2]. This framework defines accessibility as the combined effect of transport systems, land use patterns, temporal conditions, and individual characteristics. Rather than attempting to operationalise all measurement dimensions within the routing engine itself, this study adopts the component-based perspective to clarify how the platform supports accessibility analysis and where extensions are required.

The transport component is fully supported by the platform. Using GTFS and OpenStreetMap data, OTP explicitly models public transport services, walking connections, transfers, and travel times. The route validity and coverage results demonstrate that the system can reliably represent transport supply across multiple metropolitan regions. Observed coverage gaps in cities such as Brisbane and Darwin highlight areas where transport services are limited or fragmented, making the platform useful for identifying underserved regions.

The land use component is partially supported through the explicit definition of origins and destinations. In this study, residential meshblocks and CBD centroids were used to represent access to urban opportunities. While the platform does not internally model the attractiveness or capacity of destinations, it can easily be extended to include hospitals, schools, employment centres, or other points of interest from crowdsourced dataset such as OpenStreetMap, or authoritative spatial datasets. This flexibility enables comparative accessibility analysis across different types of services and regions.

The temporal component of accessibility is partially supported by the platform. OpenTripPlanner models the temporal availability of public transport services through GTFS schedules, allowing routing queries to be evaluated at specific dates and times, such as peak commuting hours. This enables consistent analysis of when transport services are available and how travel time varies across time periods.

However, the platform does not model the opening hours or activity schedules of destinations, such as office working hours, school times, or service availability at hospitals and shops. These temporal characteristics relate to land use activities rather than transport supply and are not included in GTFS data. Such information can be obtained from external sources, including crowdsourced platforms or authorised data providers, and linked to routing outputs during post-processing.

As a result, the platform supports the transport-related temporal dimension out of the box, while activity-based temporal constraints can be incorporated through external datasets when required. This separation allows researchers to control time-specific transport conditions while flexibly extending analysis to activity-based accessibility questions.

The individual component of accessibility is not directly represented in the current platform. Attributes such as income, gender, educational level, age, disability status, or vehicle ownership describe personal circumstances that influence how individuals experience transport systems. These characteristics are not contained in GTFS or OpenStreetMap data and therefore cannot be modelled directly by the routing engine.

Nevertheless, the platform is designed to support individual-level analysis through linkage with demographic and socio-economic datasets. For example, demographic attributes from census data or household surveys can be linked to origin locations during post-processing, allowing routing results to be analysed by population group. In this way, the platform provides the transport-side inputs required for individual accessibility studies, while personal characteristics are incorporated analytically rather than operationally.

This separation reflects a deliberate design choice, ensuring that routing remains transparent and reproducible, while enabling researchers to apply individual-level equity analysis using authoritative demographic sources.

6.4. Implementation Challenges and Future Work

Throughout the development and deployment of the multi-router OTP platform, several technical and practical challenges were encountered. One key issue was the size of the road network data, especially in large cities like Sydney and Melbourne. Due to memory constraints and routing stability concerns, the OpenStreetMap (OSM) extracts were trimmed locally to city boundaries. While this approach improved performance and enabled smoother server operation, it also introduced a known limitation—trips crossing city or state borders could not be processed. For example, routes from Melbourne to Sydney were not routable, since each router was built from independently trimmed maps.

Another practical constraint was the manual preparation of GTFS data. Each feed had to be processed separately to match OTP requirements, particularly around calendar validity and service dates. This task was time-consuming and error-prone, especially when updates to GTFS versions became available. At present, no automated module is in place to rebuild GTFS bundles and regenerate graph objects. This manual process limits the frequency of updates and scalability of the platform, especially for nationwide use.

Despite these constraints, the platform remained stable in a shared institutional server with 24 GB of RAM and 8 vCPUs, where 16 GB was allocated to OTP. This configuration was found to be sufficient for running eight concurrent routers, each handling its own state-level transport network. In contrast, a local test environment with lower memory showed degraded performance, supporting fewer than 50 concurrent clients and exhibiting a significantly lower throughput. This contrast highlights the importance of appropriate resource provisioning when deploying large-scale multi-router OTP platforms.

The development of this multi-router platform opens up several directions for future work, extending both its technical capabilities and its value as a tool for transport planning and research:

Advancing real-time routing capabilities by integrating GTFS-realtime feeds to reflect live service changes and delays, improving the system’s ability to simulate operational conditions and compete with commercial routing platforms;

Platform modernisation and transition to OTP 2.x, which promotes a microservices-based architecture and encourages containerised deployment using orchestration tools such as Kubernetes, with a feasibility study planned to assess scalability, infrastructure requirements, and accessibility for institutions with limited technical capacity;

Applying the platform for equity-focused accessibility research by integrating socio-economic and demographic datasets to identify underserved communities, examine spatial transport disparities, and inform evidence-based, inclusive transport and land use policies.

These future directions aim not only to improve the technical performance of the system, but also to extend its relevance for academic and policy-driven research. By combining scalable infrastructure with open-access data and equitable transport principles, the platform can evolve into a reproducible tool for accessibility analysis, supporting a wide range of urban mobility and planning objectives.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility of deploying OpenTripPlanner (OTP) as an open and reproducible platform for analysing public transport accessibility across multiple Australian cities. Beyond technical validation, the work shows how shared routing infrastructure can support transparent, repeatable, and comparable accessibility analysis in federated transport systems.

The results indicate that OTP can consistently generate structurally valid journeys and achieve high spatial coverage across most metropolitan regions when using standardised GTFS and OpenStreetMap data. Although the platform does not incorporate real-time service conditions, this reliance on static and openly defined inputs is a methodological strength for accessibility research. It enables controlled comparison across cities, neighbourhoods, and time periods, which is essential for evaluating transport equity and long-term planning outcomes.

From a societal and planning perspective, the platform provides practical support for equitable transport analysis. By enabling large-scale, automated journey simulation, it allows researchers and public-sector organisations to identify service gaps, underserved areas, and spatial inequalities in public transport provision. These capabilities are directly relevant to transport justice, where fair access to employment, education, healthcare, and other essential services depends on transparent and explainable evidence.

The open design of the platform lowers barriers for universities, public agencies, and non-government organisations that may lack access to proprietary routing services or advanced technical infrastructure. By making routing assumptions, data inputs, and workflows explicit, the platform supports accountable decision-making and reproducible policy analysis. In this way, the contribution extends beyond technical feasibility and supports sustainable urban mobility strategies grounded in openness, comparability, and public interest research.

Future work integrating socio-economic, land use, and demographic datasets can further strengthen the platform’s role in supporting inclusive and equitable transport planning across diverse urban contexts.