ConWave-LoRA: Concept Fusion in Customized Diffusion Models with Contrastive Learning and Wavelet Filtering

Abstract

1. Introduction

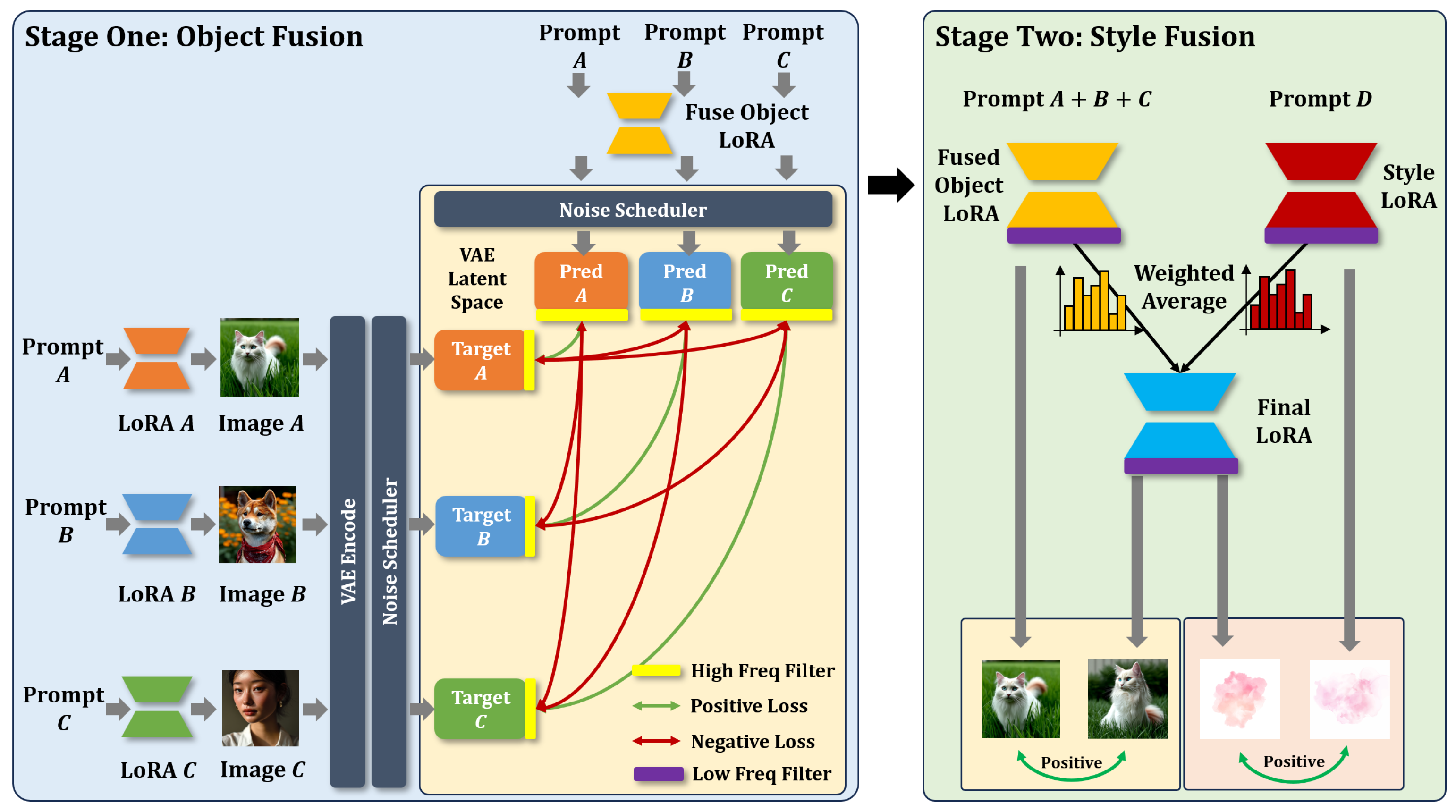

- We formally characterize the parameter pollution problem in multi-LoRA concept fusion as a conflict between optimization directions in shared parameter spaces, and analyze its degradation effects on image generation quality.

- We introduce ConWave-LoRA, a frequency-aware two-stage framework. Unlike prior works treating all parameters uniformly, we propose a DWT-based orthogonal filtering strategy to isolate high-frequency object details from low-frequency style attributes, effectively creating non-conflicting optimization subspaces for different concepts.

- We provide empirical validation of the frequency distribution assumption within the latent space (Section 4.2), visually and statistically confirming the mapping between frequency bands and semantic concepts.

- We conduct extensive experiments and expanded ablation studies (including LoRA Rank sensitivity and Style Consistency metrics). The results demonstrate that ConWave-LoRA achieves state-of-the-art performance in preserving both object fidelity and stylistic coherence compared to existing strong baselines.

2. Related Work

2.1. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

2.2. Concept Fusion with LoRA

2.3. Contrastive Learning

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Learning Paradigm of LoRA and Problem Formulation

3.2. Overview

3.3. Object Fusion

3.4. Style Fusion

3.5. Computational Cost and Novelty of the Proposed Method

- 1.

- Orthogonal Optimization Subspaces: Existing methods optimize a unified objective where gradients from object identity and artistic style are mixed, often leading to destructive interference (e.g., style textures overriding object edges). In contrast, ConWave-LoRA introduces a frequency-aware filtering strategy. By applying DWT, we theoretically project the optimization targets into orthogonal subspaces: high-frequency bands for structural identity and low-frequency bands for global style. This ensures that the gradient updates for style adaptation do not pollute the structural integrity of the object, a mechanism validated by our analysis in Section 4.2.

- 2.

- Hierarchical Concept Disentanglement: Unlike prior “joint training” paradigms that treat all concepts uniformly, we propose a ”Structure-First, Style-Second” hierarchical framework. This design is motivated by the inherent semantic hierarchy of image generation—geometric structure (Object) forms the foundation upon which textural attributes (Style) are rendered. Our method respects this hierarchy, effectively decoupling the learning process to avoid the image pollution observed in naive fusion.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experiment Settings

4.1.1. Implementation Details

4.1.2. Baselines

4.1.3. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

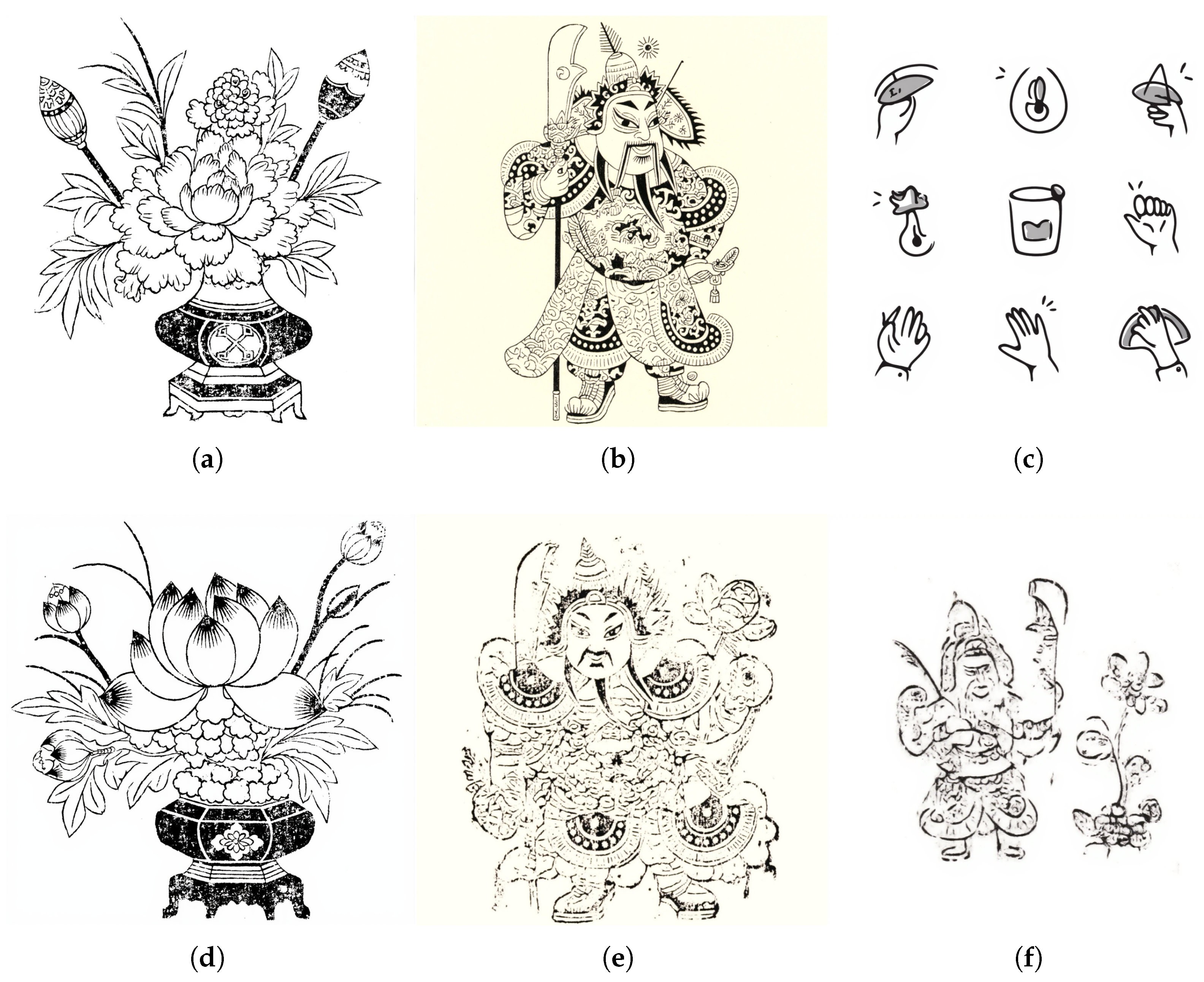

4.2. Frequency Analysis on Images in Latent Space

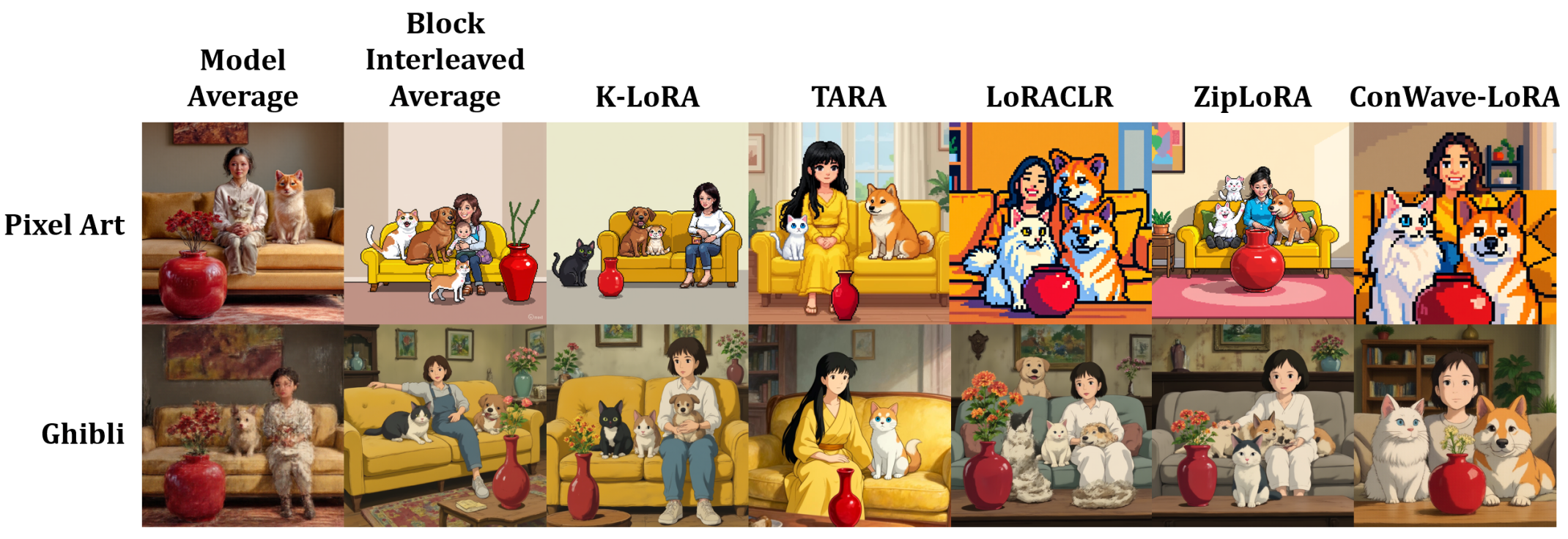

4.3. Image Generation Performance Comparison

4.4. Ablation Study

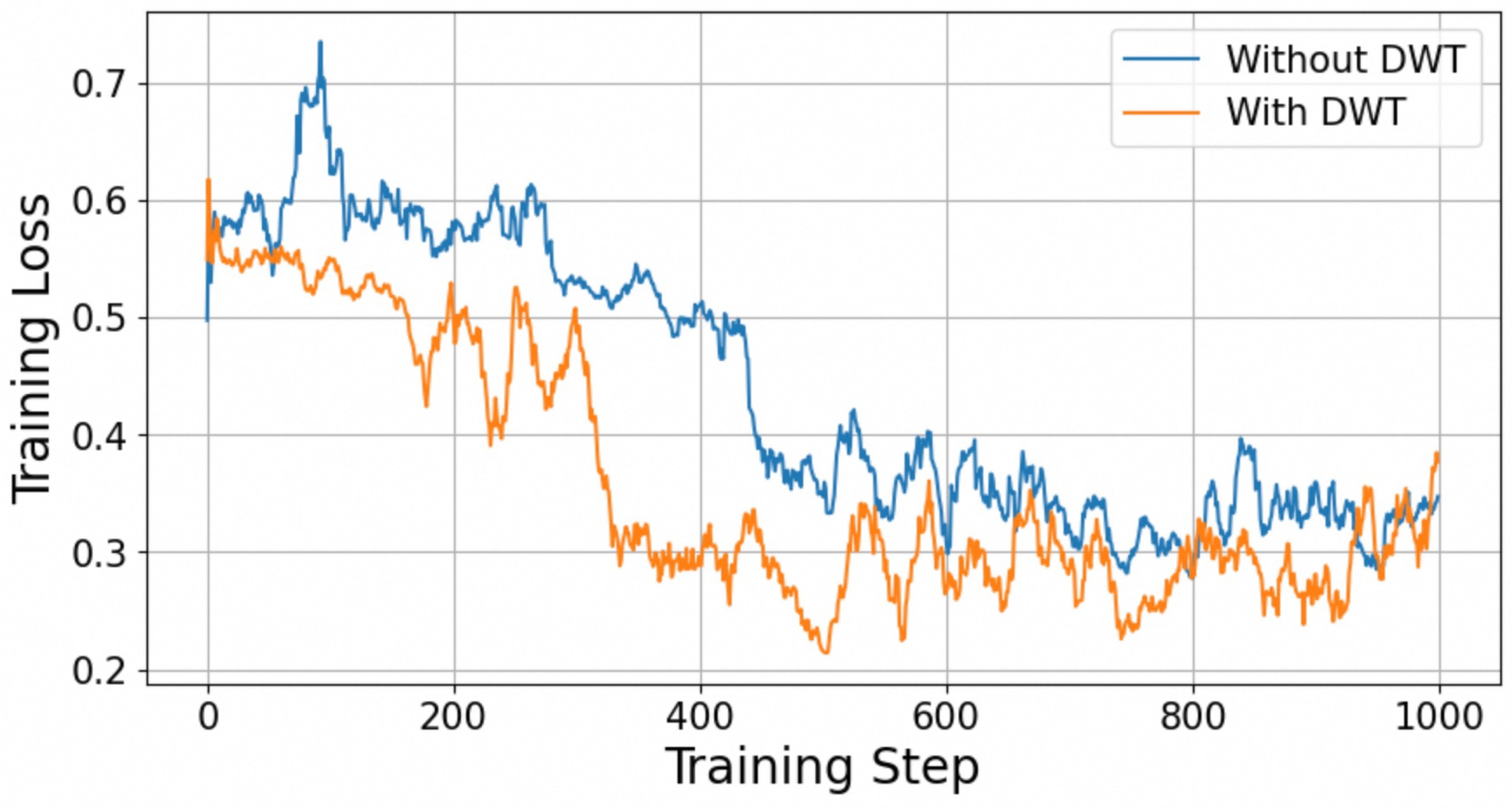

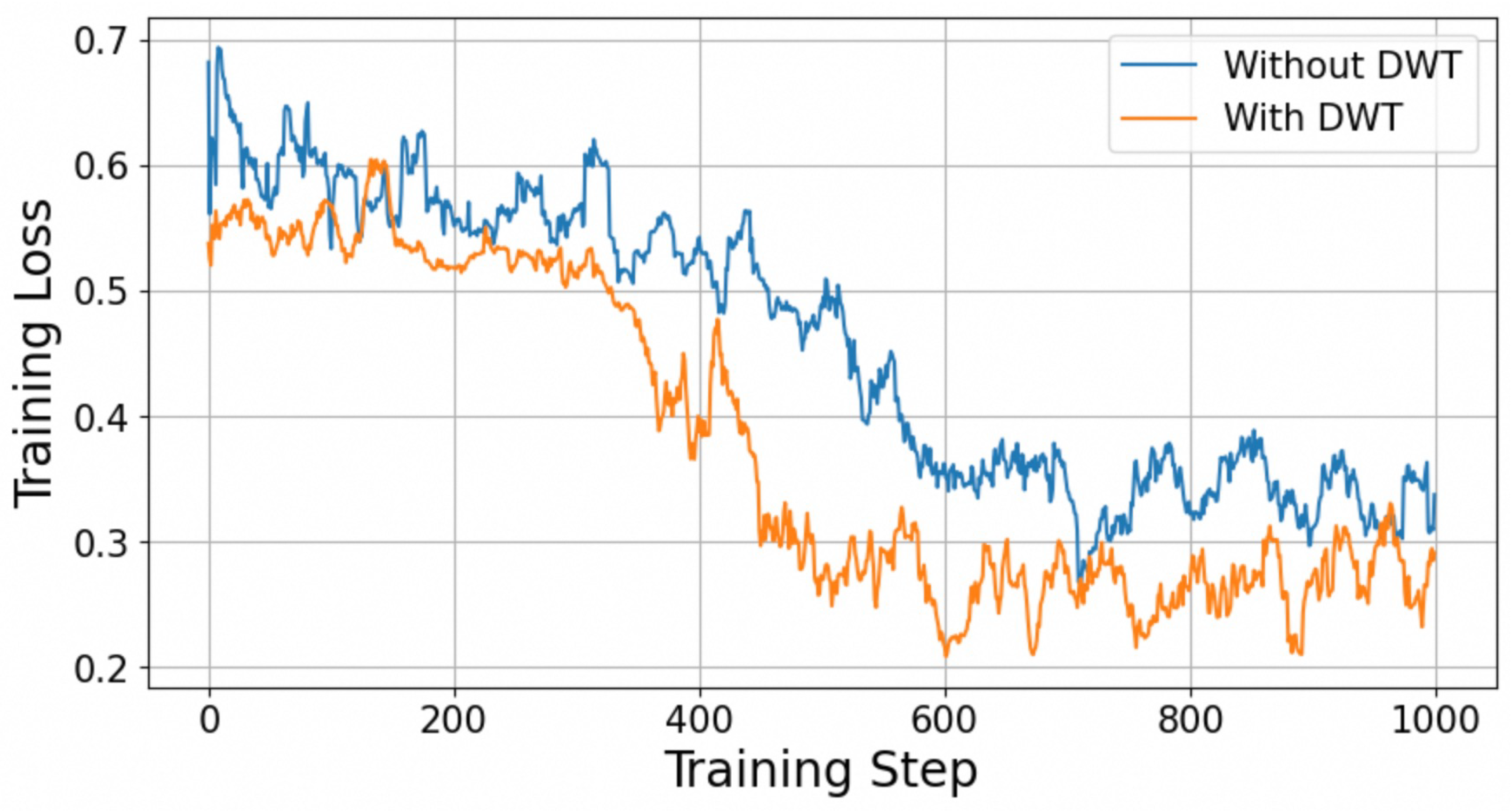

4.4.1. Necessity of Discrete Wavelet Transform

4.4.2. Effects of Different LoRA Ranks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Kingma, D.P.; Kumar, A.; Ermon, S.; Poole, B. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.13456. [Google Scholar]

- Lipman, Y.; Chen, R.T.; Ben-Hamu, H.; Nickel, M.; Le, M. Flow matching for generative modeling. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.02747. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, P.; Kulal, S.; Blattmann, A.; Entezari, R.; Müller, J.; Saini, H.; Levi, Y.; Lorenz, D.; Sauer, A.; Boesel, F.; et al. Scaling rectified flow transformers for high-resolution image synthesis. In Proceedings of the Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Lin, J.; Gao, K.; Yan, K.; Yin, S.; Bai, S.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Qwen-Image Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.02324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharif, W.; Alzubaidi, M.; She, J.; Agus, M. Visualizing Ambiguity: Analyzing Linguistic Ambiguity Resolution in Text-to-Image Models. Computers 2025, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, L.; Iacono, S.; Zolezzi, D.; Vercelli, G.V. Advancing Persistent Character Generation: Comparative Analysis of Fine-Tuning Techniques for Diffusion Models. AI 2024, 5, 1779–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V.; Pritch, Y.; Rubinstein, M.; Aberman, K. Dreambooth: Fine tuning text-to-image diffusion models for subject-driven generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 22500–22510. [Google Scholar]

- Civitai. Available online: https://civitai.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- HuggingFace. Available online: https://huggingface.co/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Low-Rank Adaptation for Fast Text-to-Image Diffusion Fine-Tuning. Available online: https://github.com/cloneofsimo/lora (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Antona, H.; Otero, B.; Tous, R. Low-Cost Training of Image-to-Image Diffusion Models with Incremental Learning and Task/Domain Adaptation. Electronics 2024, 13, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wallis, P.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Meng, L. Model Compression for Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. Computers 2023, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, M.; Ben Ayed, I. Low-rank few-shot adaptation of vision-language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 1593–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Tewel, Y.; Kaduri, O.; Gal, R.; Kasten, Y.; Wolf, L.; Chechik, G.; Atzmon, Y. Training-free consistent text-to-image generation. ACM Trans. Graph. TOG 2024, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Li, Z.; Hou, Q. K-lora: Unlocking training-free fusion of any subject and style loras. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18461. [Google Scholar]

- Simsar, E.; Hofmann, T.; Tombari, F.; Yanardag, P. LoRACLR: Contrastive Adaptation for Customization of Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 10 June 2025; pp. 13189–13198. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, V.; Ruiz, N.; Cole, F.; Lu, E.; Lazebnik, S.; Li, Y.; Jampani, V. Ziplora: Any subject in any style by effectively merging loras. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 422–438. [Google Scholar]

- Meral, T.H.S.; Simsar, E.; Tombari, F.; Yanardag, P. Conform: Contrast is all you need for high-fidelity text-to-image diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9005–9014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kwon, T.; Ye, J.C. Diffusionclip: Text-guided diffusion models for robust image manipulation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2426–2435. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y. Contrastive learning with synthetic positives. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 430–447. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, S.; Abstreiter, K.; Bauer, S.; Schölkopf, B.; Mehrjou, A. Diffusion based representation learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 24963–24982. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, H.; Kwon, G.; Park, G.Y.; Ye, J.C. Contrastive denoising score for text-guided latent diffusion image editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9192–9201. [Google Scholar]

- Dalva, Y.; Yanardag, P. Noiseclr: A contrastive learning approach for unsupervised discovery of interpretable directions in diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 24209–24218. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Gong, C.; Liu, Q. Flow straight and fast: Learning to generate and transfer data with rectified flow. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yan, M.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. TARA: Token-Aware LoRA for Composable Personalization in Diffusion Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.08812. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Sun, K.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, R.; Li, H. Human preference score: Better aligning text-to-image models with human preference. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2023; pp. 2096–2105. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiurău, D.; Popescu, D.E. Distinguishing Reality from AI: Approaches for Detecting Synthetic Content. Computers 2025, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatys, L.A.; Ecker, A.S.; Bethge, M. A neural algorithm of artistic style. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1508.06576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Dog | Cat | Vase | Woman | Sofa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Average | 0.245 ± 0.006 | 0.261 ± 0.004 | 0.273 ± 0.005 | 0.209 ± 0.009 | 0.257 ± 0.009 |

| Block Interleaved Average | 0.239 ± 0.006 | 0.260 ± 0.005 | 0.270 ± 0.009 | 0.201 ± 0.007 | 0.258 ± 0.005 |

| K-LoRA | 0.221 ± 0.003 | 0.243 ± 0.002 | 0.261 ± 0.003 | 0.213 ± 0.005 | 0.243 ± 0.004 |

| TARA | 0.264 ± 0.007 | 0.263 ± 0.004 | 0.268 ± 0.007 | 0.227 ± 0.002 | 0.273 ± 0.005 |

| LoRACLR | 0.270 ± 0.005 | 0.265 ± 0.003 | 0.283 ± 0.005 | 0.235 ± 0.008 | 0.280 ± 0.007 |

| ZipLoRA | 0.262 ± 0.010 | 0.249 ± 0.008 | 0.271 ± 0.010 | 0.230 ± 0.009 | 0.267 ± 0.009 |

| ConWave-LoRA | 0.271 ± 0.004 | 0.272 ± 0.002 | 0.292 ± 0.007 | 0.234 ± 0.010 | 0.287 ± 0.005 |

| Method | Dog | Cat | Vase | Woman | Sofa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Average | 0.584 ± 0.013 | 0.602 ± 0.011 | 0.632 ± 0.015 | 0.613 ± 0.020 | 0.627 ± 0.010 |

| Block Interleaved Average | 0.592 ± 0.023 | 0.594 ± 0.018 | 0.633 ± 0.023 | 0.607 ± 0.028 | 0.601 ± 0.021 |

| K-LoRA | 0.597 ± 0.007 | 0.583 ± 0.010 | 0.594 ± 0.007 | 0.580 ± 0.014 | 0.574 ± 0.005 |

| TARA | 0.832 ± 0.024 | 0.899 ± 0.017 | 0.873 ± 0.012 | 0.840 ± 0.032 | 0.892 ± 0.014 |

| LoRACLR | 0.893 ± 0.035 | 0.927 ± 0.018 | 0.913 ± 0.024 | 0.869 ± 0.049 | 0.938 ± 0.020 |

| ZipLoRA | 0.854 ± 0.027 | 0.901 ± 0.015 | 0.894 ± 0.018 | 0.862 ± 0.037 | 0.910 ± 0.015 |

| ConWave-LoRA | 0.912 ± 0.031 | 0.948 ± 0.020 | 0.928 ± 0.022 | 0.874 ± 0.051 | 0.956 ± 0.013 |

| Method | Dog | Cat | Vase | Woman | Sofa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Average | 0.238 ± 0.004 | 0.232 ± 0.001 | 0.247 ± 0.002 | 0.241 ± 0.005 | 0.243 ± 0.002 |

| Block Interleaved Average | 0.240 ± 0.007 | 0.228 ± 0.003 | 0.257 ± 0.001 | 0.253 ± 0.009 | 0.250 ± 0.004 |

| K-LoRA | 0.251 ± 0.006 | 0.262 ± 0.004 | 0.270 ± 0.002 | 0.267 ± 0.003 | 0.257 ± 0.002 |

| TARA | 0.270 ± 0.008 | 0.281 ± 0.006 | 0.284 ± 0.008 | 0.273 ± 0.004 | 0.275 ± 0.007 |

| LoRACLR | 0.264 ± 0.010 | 0.265 ± 0.007 | 0.283 ± 0.004 | 0.271 ± 0.005 | 0.270 ± 0.009 |

| ZipLoRA | 0.280 ± 0.005 | 0.276 ± 0.005 | 0.284 ± 0.007 | 0.279 ± 0.007 | 0.273 ± 0.010 |

| ConWave-LoRA | 0.286 ± 0.008 | 0.305 ± 0.002 | 0.302 ± 0.002 | 0.286 ± 0.011 | 0.286 ± 0.004 |

| Method | Text Alignment | Aesthetic Score |

|---|---|---|

| Model Average | 0.257 ± 0.022 | 0.308 ± 0.009 |

| Block Interleaved Average | 0.252 ± 0.024 | 0.307 ± 0.012 |

| K-LoRA | 0.243 ± 0.011 | 0.331 ± 0.004 |

| TARA | 0.284 ± 0.015 | 0.341 ± 0.010 |

| LoRACLR | 0.289 ± 0.020 | 0.340 ± 0.007 |

| ZipLoRA | 0.290 ± 0.026 | 0.346 ± 0.008 |

| ConWave-LoRA | 0.301 ± 0.013 | 0.358 ± 0.006 |

| Method | Pixel Art Style | Ghibli Style |

|---|---|---|

| Model Average | 0.068 ± 0.007 | 0.073 ± 0.011 |

| Block Interleaved Average | 0.044 ± 0.008 | 0.050 ± 0.005 |

| K-LoRA | 0.041 ± 0.009 | 0.051 ± 0.004 |

| TARA | 0.034 ± 0.012 | 0.040 ± 0.008 |

| LoRACLR | 0.029 ± 0.014 | 0.032 ± 0.009 |

| ZipLoRA | 0.030 ± 0.007 | 0.028 ± 0.006 |

| ConWave-LoRA | 0.024 ± 0.008 | 0.025 ± 0.007 |

| LoRA Rank | Text Alignment | Aesthetic Score |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.254 ± 0.007 | 0.338 ± 0.003 |

| 8 | 0.262 ± 0.012 | 0.355 ± 0.007 |

| 16 | 0.301 ± 0.013 | 0.358 ± 0.006 |

| 32 | 0.309 ± 0.015 | 0.356 ± 0.009 |

| 64 | 0.299 ± 0.019 | 0.353 ± 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Huo, X.; Yang, Z. ConWave-LoRA: Concept Fusion in Customized Diffusion Models with Contrastive Learning and Wavelet Filtering. Computers 2026, 15, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010005

Liu X, Huo X, Yang Z. ConWave-LoRA: Concept Fusion in Customized Diffusion Models with Contrastive Learning and Wavelet Filtering. Computers. 2026; 15(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinying, Xiaogang Huo, and Zhihui Yang. 2026. "ConWave-LoRA: Concept Fusion in Customized Diffusion Models with Contrastive Learning and Wavelet Filtering" Computers 15, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010005

APA StyleLiu, X., Huo, X., & Yang, Z. (2026). ConWave-LoRA: Concept Fusion in Customized Diffusion Models with Contrastive Learning and Wavelet Filtering. Computers, 15(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010005