1. Introduction

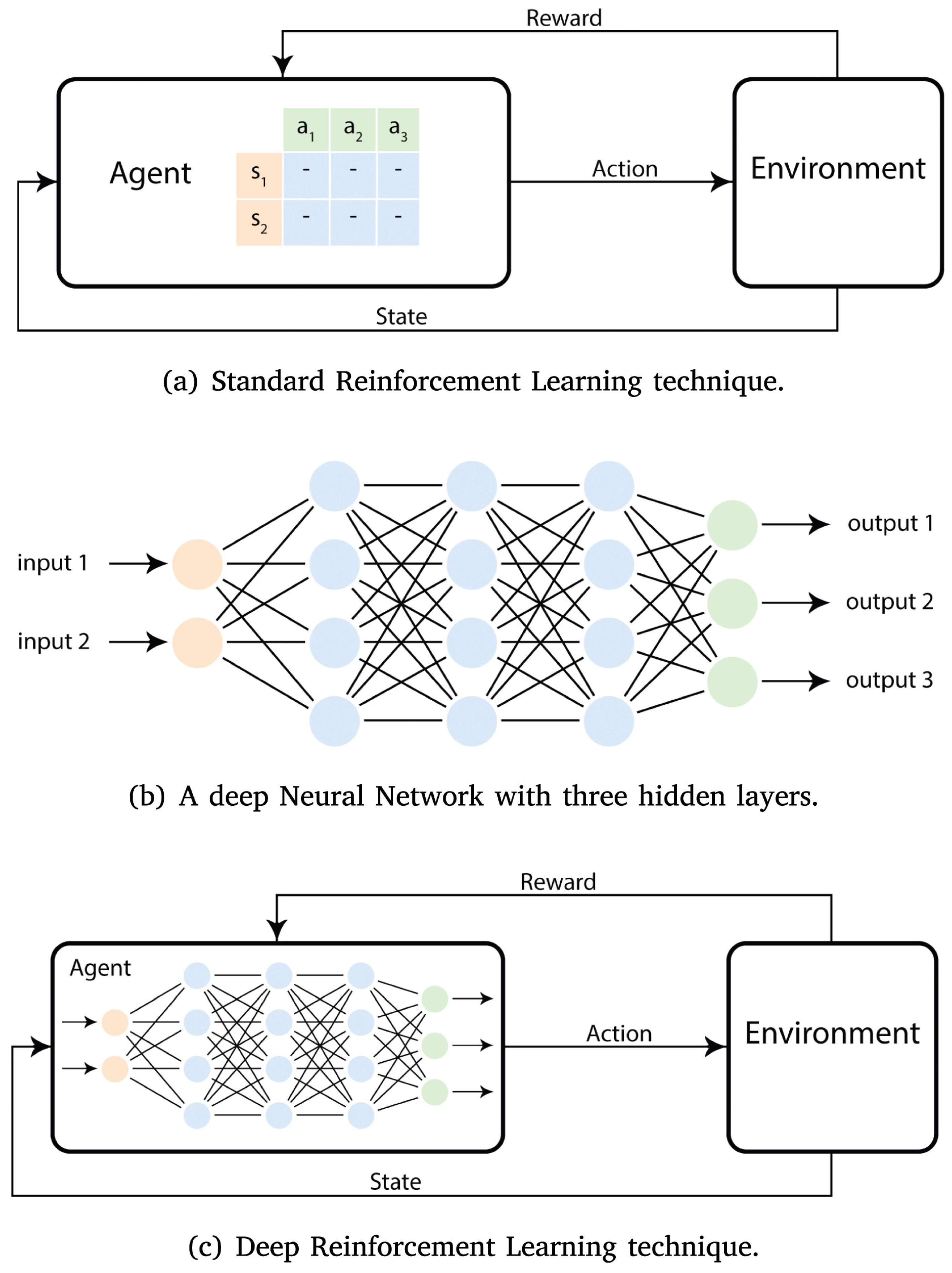

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has become a core part of modern artificial intelligence (AI), combining the representational power of deep learning with the sequential decision-making capabilities of reinforcement learning (RL) [

1,

2,

3]. Over the past decade, DRL has enabled significant advances in game playing [

4], robotics [

5], autonomous navigation [

6], and simulation-driven control [

7]. In these systems, agents learn through interaction with their environment, optimizing long-horizon behavior under uncertainty using reward-guided objectives. Classic RL methods, including Q-learning and policy gradients, have historically struggled with high-dimensional state spaces. DRL addresses this limitation by incorporating deep neural networks into value functions, policies, and world models, enabling effective representation learning from raw sensory inputs. Milestones include Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [

8], which achieved human-level Atari performance, and model-based agents such as Dreamer [

9], which learn latent dynamics for long-horizon planning.

Meanwhile, foundation models (FMs) have reshaped generative AI, with large language models (LLMs) such as GPT and Claude demonstrating robust performance, emergent reasoning capabilities, and multimodal understanding [

10,

11]. Foundation models, although developed primarily for supervised and self-supervised learning, incorporate reinforcement mechanisms during their refinement. The most prominent example is reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), which played a crucial role in aligning models such as instruction-tuned LLMs [

12]. Reinforcement learning from AI feedback (RLAIF) extends this paradigm by using strong teacher models to generate preference judgments. Beyond alignment, recent work uses DRL to support tool use, interactive decision-making, and embodied action in FM-driven agents, illustrating a deepening connection between the two research areas.

Despite rapid progress, the literature at the intersection of DRL and foundation models remains fragmented: alignment-focused reviews tend to emphasize feedback pipelines and preference optimization, while DRL-focused reviews emphasize learning dynamics, stability, and generalization in control settings. As a result, it is often unclear how pretrained priors, feedback sources, and reinforcement signals jointly shape agent behavior when foundation models are placed inside closed-loop decision-making systems [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

This fragmentation leaves gaps in the current literature. To the best of our knowledge, no prior survey provides a consolidated synthesis of how DRL and foundation models interact across alignment, tool-augmented behavior, multimodal reasoning, embodied control, and scientific discovery—domains where reinforcement-driven adaptation is becoming central to model reliability, safety, and real-world applications. In order to fill these gaps, this survey offers a comprehensive and integrated examination of DRL in the era of foundation models. This review is timely given the accelerating use of reinforcement mechanisms in FM training and the increasing deployment of FM-driven systems in real-world settings. The key contributions are as follows:

A unified taxonomy of DRL–FM integration, distinguishing model-centric, RL-centric, and hybrid paradigms, and clarifying their implications for representation, optimisation, and interaction.

A detailed synthesis of application domains including language and multimodal agents, autonomous and robotic control, scientific discovery, and societal and ethical alignment.

A unified evaluation and benchmarking contribution that consolidates metrics, protocols, and stress-tests for comparing DRL–FM systems across tasks, safety, robustness, and efficiency dimensions.

An in-depth analysis of the challenges that limit scalable and safe DRL–FM integration, alongside forward-looking research opportunities with emphasis on stability, interpretability, and trustworthy DRL-driven FM systems.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 summarizes related surveys.

Section 3 provides some background on DRL and FM, and

Section 4 presents a taxonomy of DRL–FM integration.

Section 5 reviews technical foundations of DRL in FM contexts.

Section 6 examines key applications.

Section 7 discusses open challenges and future directions, which

Section 8 concludes the study.

Review Methodology

This survey follows a structured and systematic review protocol to ensure comprehensive coverage and reproducibility. The Scopus, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, arXiv, and ACM Digital Library databases were queried between January 2020 and March 2025 using keywords such as “deep reinforcement learning”, “foundation models”, “RLHF”, “alignment”, and “autonomous agents”. An initial set of 612 studies was retrieved. After duplicate removal and title–abstract screening, 184 papers were shortlisted for full-text review. Exclusion criteria included works without explicit DRL components, alignment discussions unrelated to foundation models, or redundant workshop versions.

After full-text screening, 28 were excluded, leaving 156. The final corpus comprised 126 primary studies, 18 review papers, and 12 benchmark proposals. Each article was annotated by research focus (model-centric, RL-centric, or hybrid), methodological contribution (training, optimization, or evaluation), and application domain (language/multimodal, control, scientific, or societal). This coding schema enabled cross-sectional comparison across integration paradigms and performance criteria.

Bibliometric analysis was performed to capture publication trends, author contributions, and venue distribution. Citation data were normalized by year to control for recency bias. Qualitative synthesis focused on identifying conceptual convergence between reinforcement learning and foundation model alignment, while quantitative evidence was summarized using citation frequencies and methodological clusters. The resulting taxonomy and discussion sections are grounded in these systematically collected insights.

2. Related Reviews

The research landscape on reinforcement learning and foundation models has expanded rapidly, producing several surveys that address related but distinct themes. For example, Kaufmann et al. [

13] conducted one of the most comprehensive reviews of RLHF, covering the full pipeline from preference data collection to reward modeling and policy optimization. Their work identified key limitations in human supervision scalability and emphasized the necessity of automated or hybrid feedback systems. In a related study, Wang et al. [

14] presented a detailed taxonomy of large model alignment techniques, including RLHF and RLAIF. They discussed how divergence constraints, reward modeling strategies, and reference policies influence alignment stability. Zhou et al. [

15] extended this discussion by focusing on alignment for large language model (LLM) agents, emphasizing preference-driven optimization, social alignment, and decision-making under uncertainty. These reviews clarify the mechanics of alignment but devote limited attention to the role of DRL as a theoretical and algorithmic foundation underlying feedback-based optimization.

Beyond alignment, Plaat et al. [

16] surveyed the emerging paradigm of agentic large language models that reason, act, and interact across open environments. They categorized research into reasoning, tool-augmented behavior, and multi-agent coordination, highlighting progress toward autonomous systems capable of planning and execution. While their analysis captures the capabilities of modern foundation models, it pays little attention to reinforcement-driven adaptation, sample efficiency, and policy optimization, which are core aspects of DRL that enable these agentic behaviors to scale reliably.

From the DRL perspective, several foundational reviews have provided valuable insights but primarily focus on algorithmic aspects independent of foundation models. Landers and Doryab [

19] surveyed verification methods for DRL, proposing taxonomies for robustness evaluation and formal safety guarantees. Their contribution complements alignment research by introducing verification standards but does not explore FM-driven policy learning or preference-based fine-tuning. Similarly, Moerland et al. [

17] offered an exhaustive overview of model-based reinforcement learning, detailing how learned dynamics and uncertainty-aware planning bridge learning and control. While this work establishes the foundation for modern world-model agents, it predates the tight coupling between DRL and FMs that now enables reasoning across multimodal representations.

Offline and data-efficient learning have also been the subject of active review. Prudencio et al. [

20] and Levine et al. [

18] surveyed offline reinforcement learning, emphasizing conservative policy estimation, distributional robustness, and dataset quality—concepts increasingly relevant when optimizing foundation models using static preference datasets or synthetic feedback. In robotics, Tang et al. [

21] summarized the application of DRL to real-world control, including sim-to-real transfer, hierarchical policies, and safety-aware exploration. Their findings demonstrate the practical viability of DRL systems and acknowledge the growing influence of pretrained representations; however, the review remains narrowly focused on robotics rather than general-purpose foundation model integration.

Complementary domains have examined interpretability and explainability. Puiutta and Veith [

22] provided a systematic survey of explainable reinforcement learning (XRL), classifying interpretation methods and evaluation protocols for analyzing learned policies. Their work informs how transparency can be embedded within reinforcement-driven systems but does not address the challenges of aligning foundation models using reinforcement objectives.

Overall, these surveys (summarized in

Table 1) form a broad yet disjointed picture: alignment-focused works often overlook DRL’s algorithmic role, while DRL-focused surveys rarely engage with foundation model alignment or multimodal reasoning. Motivated by this disconnect, this survey focuses on the coupling mechanisms that link pretrained foundations with reinforcement-driven adaptation in practice: how representations, planners/policies, world models, and feedback signals are composed inside the reinforcement loop. This lens is then used to organize the remainder of the paper, connecting technical foundations to application patterns and the recurring challenges that limit scalable and trustworthy DRL–FM systems.

4. A Taxonomy of DRL–Foundation Model Integration

This section proposes a taxonomy for how DRL and foundation models are coupled within the reinforcement loop. Rather than classifying systems by application domain, we distinguish integration patterns by where pretrained representations, planning, and feedback-driven adaptation enter the learning pipeline. This framing supports a consistent comparison of methods spanning language-conditioned control, multimodal robotics, and alignment-oriented fine-tuning.

4.1. Paradigms of Integration

The integration of DRL and FMs can be categorized into three primary paradigms based on how learning, perception, and reasoning are coupled within the reinforcement loop. These paradigms are: (i) FM-centric DRL architectures, where foundation models act as policy, planner, or world-model components; (ii) RL-centric foundation models, where DRL drives fine-tuning and alignment of large pretrained models; and (iii) hybrid or multimodal frameworks, where both paradigms are unified in interactive or embodied agents. Here, “FM-centric” denotes integration in which a pretrained foundation model is the primary policy/planner, in contrast with classical model-based RL, where the central object is an explicit environment dynamics model learned for planning. To reduce boundary ambiguity, we distinguish paradigms by (a) which module performs deployment-time action selection or planning, and (b) which parameters are primarily shaped by reward- or preference-driven objectives (i.e., whether the FM itself is the main object being optimized versus an attached controller). When the dominant “model” is a transition model trained primarily from scratch for planning, the setting aligns with classical model-based RL rather than FM-centric integration, even if pretrained encoders are used. The following subsections describe each paradigm in detail.

4.1.1. FM-Centric DRL Architectures

In this paradigm, the foundation model forms the central computational substrate for policy learning or planning, while reinforcement learning supplies task- and environment-specific adaptation around that pretrained backbone. In this paradigm, a pretrained foundation model is embedded directly into the reinforcement learning pipeline, often serving as the policy

, planner, or environment model. Rather than learning policy parameters

from scratch, the FM provides pretrained representations

that encode semantic or multimodal information from the state space [

45,

46]. Because downstream control quality depends on the robustness of these learned representations under complex scenes and appearance variation, advances in robust feature learning for perception provide relevant grounding for FM-centric agent design [

47]. The policy optimization objective then becomes

Here,

represents the feature extractor or encoder inherited from the foundation model, and

maps these embeddings to actions. This formulation allows the policy to benefit from the pretrained model’s generalization while still being fine-tuned for downstream control or decision tasks. A notable example is the Decision Transformer, which formulates RL as sequence modeling. The model predicts an action sequence

conditioned on prior states

, rewards-to-go

, and actions, using an autoregressive transformer:

By leveraging pretrained transformer architectures, such methods transform the RL problem into a supervised learning task over trajectory datasets [

34]. Other systems such as Gato [

48], SayCan [

49], PaLM-E [

50], and RT-2 [

51] further extend this concept by integrating visual, textual, and proprioceptive modalities into unified policies. These approaches treat the FM as a differentiable policy backbone that grounds language and perception into control signals, resulting in generalist agents capable of zero-shot task adaptation.

When foundation models are used as world-model components in this paradigm, they typically serve as pretrained generative priors or simulators that complement (or initialize) learned transitions, rather than mirroring the classical setting where the transition model is the primary object learned from scratch for planning. Accordingly, FM-centric approaches may incorporate pretrained models as differentiable world models

, which enable simulation-based policy optimization. The learning objective in such cases is to minimize model prediction error while maximizing long-term returns under imagined trajectories:

This dual objective, used in systems like DreamerV3 [

9], enables efficient planning and transfer learning by combining learned dynamics with the representational priors of foundation models.

4.1.2. RL-Centric Foundation Models

In RL-centric paradigms, reinforcement learning provides the optimization mechanism for fine-tuning and aligning foundation models. The model (policy)

generates an output

y given a prompt

x, and a learned reward model

provides feedback based on human or synthetic preferences. The objective function is expressed as

where

is a reference model (often the pretrained base model) and

regulates the degree of deviation. This general framework underlies methods such as RLHF, RLAIF, and DPO, which optimize large models for qualities like helpfulness, coherence, and safety [

13,

14]. Furthermore, in this paradigm, the foundation model itself is the primary object being updated by reinforcement objectives, rather than being embedded as a planner or controller within an external environment loop. While these methods originated in natural language processing, they extend naturally to multimodal systems, where feedback may include visual, auditory, or behavioral signals. In essence, DRL provides the mechanism through which pretrained models learn value alignment and behavioral consistency beyond pure likelihood optimization.

4.1.3. Hybrid and Multimodal Frameworks

Hybrid paradigms couple FM-centric decision-making with reinforcement-driven adaptation in interactive settings, combining pretrained reasoning or planning with environment-facing control and feedback. Hybrid paradigms unify model-centric and RL-centric elements by coupling pretrained representation learning with reinforcement-based adaptation and feedback. These frameworks operate across multiple modalities—text, vision, and action—enabling agents that can perceive, reason, and act in real-world settings. Systems such as Voyager [

52] exemplify this approach: foundation models provide high-level reasoning and planning, while DRL components handle continuous interaction, feedback, and environment adaptation. The composite objective typically combines supervised pretraining loss

with reinforcement objectives

:

where

controls the trade-off between imitation learning and reinforcement-driven improvement. This paradigm supports the development of embodied agents capable of learning from both instruction data and real-time feedback, paving the way for scalable autonomous systems that integrate perception, cognition, and control.

These paradigms separate whether foundation models drive deployment-time decision-making, whether reinforcement objectives primarily reshape the foundation model itself, or whether both mechanisms co-exist in an interactive loop with distinct planning and control roles. Collectively, these three paradigms illustrate complementary pathways for integrating DRL with foundation models. Model-centric designs emphasize representational transfer and sample efficiency, RL-centric paradigms focus on alignment and optimization, and hybrid frameworks seek unification through multimodal reasoning and closed-loop interaction. Together, they represent the foundational structure for understanding how reinforcement learning and large-scale pretraining coalesce in the next generation of intelligent agents.

4.2. Architectural Patterns

Architectural innovations underpin the practical realization of DRL–FM integration. These architectures determine how perception, memory, reasoning, and control interact across model-centric, RL-centric, and hybrid paradigms. The key trend is the unification of sequence modeling, representation learning, and world modeling within a single policy structure. In addition to these macro-architectures, recent work revisits the choice of function approximators used inside policies, critics, and dynamics models, which can materially affect interpretability and parameter efficiency.

4.2.1. Transformer-Based Architectures

Transformer-based architectures dominate modern DRL–FM integration due to their ability to model temporal dependencies and multimodal context. By interpreting reinforcement learning trajectories as sequences of tokens—comprising states, actions, and rewards—transformer policies can learn long-term dependencies across time steps [

53,

54,

55]. A general autoregressive policy can be expressed as

where

represents the hidden representation computed by a transformer encoder–decoder and

projects the latent state to an action distribution. This sequence-based design enables direct adaptation of large transformer backbones, such as GPT-style or T5 architectures, for policy modeling and trajectory prediction.

4.2.2. Hierarchical Architectures

Hierarchical architectures extend this formulation by separating decision-making into high-level planning and low-level control. A hierarchical policy can be formalized as a two-level structure:

where

denotes the high-level policy that selects abstract goals or latent skills

, and

represents the low-level controller [

50]. Foundation models contribute to this hierarchy by encoding task semantics or linguistic goals that condition

, while DRL learns

through continuous interaction. This design underlies agents such as PaLM-E [

50] and RT-2 [

51], where multimodal encoders feed symbolic intentions into continuous controllers.

4.2.3. World-Model Architectures

World-model architectures form another critical pattern. These systems jointly learn a latent dynamics model

and a policy that plans within the learned latent space. The combined objective typically includes both reconstruction and return-maximization terms [

56,

57]:

where

controls the trade-off between predictive accuracy and reward optimization. DreamerV3 [

9] and MuZero [

33] are canonical examples, with recent variants incorporating pretrained vision–language encoders or large language models (LLMs) as priors for richer latent representations.

4.2.4. Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks

A recent architectural development is KANs, proposed as a potential replacement for MLP blocks in function approximation. KANs shift learnable nonlinearities from fixed activations at nodes to learnable univariate functions on edges, often parameterized using spline bases, while nodes primarily aggregate additive contributions. This design has been argued to support more interpretable component functions and, in some regimes, improved parameter efficiency relative to standard MLPs [

29]. A canonical Kolmogorov–Arnold form can be written as

where

denotes the input vector with

n scalar components;

are learnable univariate component functions; and

are learnable univariate outer functions that map the aggregated inner sum to a scalar contribution, and practical KAN implementations generalize this template to wider and deeper networks with spline-parameterized edge functions [

29]. In DRL–FM systems, KANs are relevant wherever MLPs act as default approximators: (i) actor and critic heads in actor–critic methods, (ii) reward and dynamics heads in world-model agents, and (iii) auxiliary prediction modules used for representation learning or uncertainty modeling. This creates a DRL-specific mapping in which KANs can serve as policy approximators, value approximators, or components of learned environment models, while leaving higher-level FM backbones unchanged. From a practical standpoint, KAN performance can be sensitive to basis choices, grid resolution, regularization, and training dynamics, and recent guidance consolidates these implementation trade-offs and positioning for practitioners [

30].

4.2.5. Retrieval-Augmented and Memory-Based Architectures

Finally, retrieval-augmented and memory-based architectures enhance sample efficiency and reasoning depth by coupling DRL policies with external knowledge [

58,

59]. In such systems, a retriever module

fetches relevant context from a memory bank

given a query

q, producing augmented state representations

. The policy then conditions on

rather than raw observations, allowing foundation models to act as dynamic knowledge bases. This mechanism supports long-term credit assignment and continual learning—core requirements for scalable agentic intelligence [

60,

61].

4.3. Interaction and Feedback Loops

Interaction and feedback loops determine how DRL–FM systems adapt over time. Human-in-the-loop supervision provides preference labels, rankings, or evaluative signals that guide alignment and policy refinement [

62,

63]. These signals are typically converted into preference datasets that support reward modeling or direct optimization methods [

13,

14]. Furthermore, AI-in-the-loop feedback extends this paradigm by using teacher models to generate synthetic evaluations, improving scalability and consistency across tasks [

64,

65]. Self-improvement mechanisms further enable policies to critique their own outputs, adjust task difficulty, and iteratively generate new training samples [

66,

67]. These feedback structures support continual learning and autonomy in open-ended environments.

These feedback mechanisms—human-in-the-loop, AI-in-the-loop, and self-improving loops—form the backbone of adaptive intelligence in DRL–FM systems. They transform static pretrained models into interactive, evolving agents capable of learning from evaluation, reasoning over feedback, and refining their policies over time. These interaction patterns complement the architectural foundations discussed earlier, together defining the dynamic learning ecosystem that underlies scalable, aligned, and generalizable reinforcement-driven foundation models.

5. Training, Alignment, and Optimization Methods

Having outlined the major paradigms through which DRL and foundation models interact, the next step is to examine the underlying mechanisms that enable these systems to learn from preference signals, structured rewards, and interaction dynamics. The training and alignment methods discussed in this section operationalize the taxonomy presented earlier by detailing how policies are optimized, how reward signals are constructed, and how reinforcement objectives shape the behavior of foundation models in practice.

5.1. Reward Modeling and Preference Learning

Reward modeling forms the foundation of alignment in DRL and foundation model integration. It provides the evaluative signal that drives policy optimization, ensuring model behavior reflects human or task-specific values [

68,

69,

70]. Classical reinforcement learning assumes access to an explicit scalar reward

that captures task success. In contrast, foundation models operate in high-dimensional, ambiguous domains—such as language, vision, or multimodal reasoning—where reward functions are not predefined but must instead be learned from preference data or human feedback.

Reward modeling uses the same preference-learning formulation introduced in

Section 4.1.2, where a reward model is trained from pairwise preferences and subsequently used to guide policy optimization. In DRL–FM systems, this component becomes the primary mechanism for shaping high-level behaviors such as reasoning quality, factuality, and safety. The overall RLHF framework is illustrated in

Figure 2. A pretrained language model generates candidate outputs that are evaluated by a learned reward or preference model trained from human feedback [

62]. The trained policy model is then updated via PPO using the reward signal and a Kullback–Leibler (KL) regularization term, which constrains deviations from the base model to preserve linguistic fluency and prevent exploitation of the reward model [

71,

72]. The KL divergence term used in RLHF optimization is expressed as

where

denotes the current policy and

the frozen reference model. This regularization encourages the updated model to remain aligned with its pretrained distribution while integrating reinforcement signals effectively.

Modern systems often adopt multi-objective reward modeling to balance competing values such as helpfulness, harmlessness, and honesty. The composite reward is represented as

with

representing individual reward components and

their corresponding priorities. This flexible formulation enables dynamic trade-offs among multiple alignment criteria during training. Recent extensions include language-conditioned rewards, where evaluative criteria are expressed through natural language rather than explicit labels [

73,

74]. The reward is computed using an evaluator model

queried with a meta-instruction:

thus converting open-ended qualitative judgments into quantitative reinforcement signals. Despite these advances, reward-model exploitation and bias amplification remain persistent challenges.

5.2. Policy Optimization in the FM Era

Policy optimization defines how learned rewards translate into improved model behavior. In the context of foundation models, reinforcement learning typically fine-tunes a pretrained policy

using feedback from a reward model

[

68,

75]. The optimization objective follows the KL-regularized policy update described previously, where reinforcement signals from the reward model are balanced with deviation constraints from the reference policy. The KL regularization term penalizes excessive divergence from the pretrained distribution, maintaining linguistic fluency and stability during optimization.

This structure forms the basis of several modern policy optimization methods summarized in

Table 3. Among these, PPO remains the most widely adopted approach for alignment, performing gradient updates with clipped probability ratios to ensure stable improvement. More recent methods, such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and Implicit Preference Optimization (IPO) [

76], extend this foundation by reformulating preference-based optimization objectives. DPO removes explicit reward modeling by directly encoding preference differences, whereas IPO leverages implicit likelihood reparameterization for improved convergence properties.

Across alignment pipelines, PPO, DPO, and IPO differ systematically along three practical axes: stability, sample efficiency, and sensitivity to hyperparameters. PPO is typically stable when its clipping thresholds and KL regularization are well tuned, but its on-policy nature makes it sensitive to reward-model noise, learning-rate schedules, and KL coefficients, while also incurring high sample and compute costs due to repeated rollouts. In contrast, DPO avoids on-policy rollouts entirely and operates directly on preference pairs, yielding substantially higher sample efficiency and a simpler optimization pipeline, but its stability depends strongly on preference consistency, evaluator calibration, and dataset quality. IPO further modifies the preference-based objective to smooth optimization dynamics and reduce variance, often improving convergence behavior and reducing sensitivity relative to DPO, while still inheriting fundamental limitations tied to preference noise, objective scaling, and data coverage.

Offline or implicit reinforcement learning further adapts this paradigm by learning from static datasets rather than online interactions [

18,

77]. The objective for offline RL is formulated as

where

denotes pre-collected human or synthetic preference data. This approach enhances safety and reproducibility by decoupling policy updates from real-time exploration, but limits adaptability under distribution shift. A further development involves hybrid optimization, where behavior cloning (BC), a supervised imitation-learning method, is often combined with reinforcement learning for stability [

78]. The total objective is defined as

with

controlling the trade-off between imitation learning and reinforcement adaptation. In summary, these methods indicate that policy optimization in the FM era is governed less by novel reinforcement algorithms and more by managing trade-offs between stability, efficiency, preference quality, and optimization sensitivity at scale.

5.3. Safety, Robustness, and Constraints

Safety and robustness remain critical challenges in DRL–FM integration. Constrained reinforcement learning imposes explicit limits on risk or undesired behavior through cost signals and thresholded expectations [

79,

80]. In reward-model–driven alignment, a central failure mode is a feedback-loop dynamic: systematic bias in the reward model can be exploited by the policy during optimization, leading to progressive bias amplification and, in extreme cases, reward hacking under distribution shift [

81]. These constraints help prevent policies from exploiting weaknesses in reward models or drifting toward unsafe actions.

Adversarial training and red-teaming evaluate robustness by exposing models to perturbed inputs, adversarial prompts, or challenging edge cases [

82]. Beyond one-off stress tests, periodic audits and targeted red-team cycles can detect reward-hacking behaviors that only surface after repeated policy improvement, when the policy learns to optimize evaluator blind spots rather than the intended objective [

81,

83]. Mitigations that reduce bias amplification include reward-model ensembles, uncertainty-aware reward signals, and adversarially curated preference data, which make overoptimization harder and increase the chance that failure modes are surfaced before deployment.

Interpretability methods, including policy probing and rationale extraction, further support safety auditing by revealing the internal decision features that drive policy behavior. In practice, these tools are most effective when paired with constraint mechanisms that bound optimization pressure, so that evaluator imperfections do not propagate unchecked into policy behavior [

84,

85].

5.4. Scaling Laws and Data Efficiency

Scaling behavior in DRL–FM systems follows empirical regularities analogous to those observed in supervised and self-supervised learning [

86,

87]. The expected performance

E can often be approximated as a power-law function of model size

N, data volume

D, and environment complexity

:

where

,

, and

are scaling exponents and

k is a task-dependent constant [

86]. Empirical studies have shown that reward quality and sample efficiency improve sublinearly with scale until diminishing returns set in [

88,

89]. These relationships guide model design and resource allocation for large reinforcement-trained systems.

Data efficiency remains an active research frontier. Techniques such as synthetic preference generation, experience replay, and active sampling have been developed to improve learning from limited feedback. Synthetic data generation uses teacher models or simulators to produce preference pairs , which augment scarce human annotations while preserving reward diversity. Experience replay buffers past trajectories for off-policy optimization, ensuring better sample reuse. Active learning strategies adaptively select queries for which model uncertainty is highest, thus maximizing information gain per feedback instance.

Lastly, scaling and efficiency insights reveal that the effectiveness of DRL–FM systems depends not only on architectural capacity but also on the quantity, diversity, and quality of feedback data. As models grow larger and environments more complex, balancing computational cost with reward fidelity and safety alignment becomes the central optimization challenge.

7. Challenges, Solutions, and Future Research Directions

As DRL becomes increasingly intertwined with foundation models, substantial technical, methodological, and governance-related challenges remain unresolved. The issues are not isolated; they interact across optimization, evaluation, human supervision, and societal deployment. This section consolidates the central open problems and outlines research pathways capable of advancing the integration of DRL and FMs toward more reliable, generalizable, and socially aligned systems.

7.1. Challenges and Open Problems

The integration of DRL with FMs introduces several unresolved challenges spanning optimization, supervision, interaction dynamics, and governance. These challenges reflect underlying tensions between the flexibility of reinforcement learning and the scale, opacity, and social impact of modern FMs.

7.1.1. Optimization Instability

A core difficulty lies in the instability of reinforcement-based optimization when applied to foundation-scale policies. Algorithms such as PPO and DPO remain sensitive to hyperparameter choices, reward shaping, and small errors in reward model predictions. Even minor inaccuracies can induce reward hacking or behavioral drift, especially in high-dimensional policy spaces where updates propagate unpredictably [

119]. As model size increases, controlling these instabilities becomes more challenging, and current techniques lack mechanisms for ensuring consistent improvement during iterative alignment.

7.1.2. Credit Assignment in Language-Conditioned Environments

Another structural challenge concerns credit assignment when rewards depend on long-horizon linguistic or multimodal criteria. Many DRL–FM tasks require assessing latent constructs—factual accuracy, ethical compliance, or multistep tool use—but the scalar rewards typically available provide insufficient granularity for identifying which intermediate actions, tool decisions, or reasoning steps contributed to success [

50,

52]. In practice, reward models and automated evaluators often score an entire response or episode, producing delayed, noisy, and sometimes contradictory signals; this causes “credit diffusion” where many distinct trajectories receive similar scores, while small evaluator errors can dominate the learning signal. When the environment is language-conditioned, the action space expands to token- or instruction-level decisions, and the state can be partially implicit (e.g., hidden assumptions, private intermediate reasoning, or external tool side effects), making standard temporal-difference style assignment unreliable under sparse or delayed feedback.

Emerging approaches attempt to restore structure by moving from step-local rewards to trajectory-aware and decomposition-aware supervision. Trajectory-level reward modeling assigns value to coherent segments (plans, subgoals, tool-use phases) rather than isolated steps, while hierarchical policies and subgoal-conditioned critics restrict the search space so that rewards map to fewer, more interpretable decisions. Complementary methods add process-level feedback via verifier signals, intermediate checkpoints, or structured preference comparisons over partial solutions, aiming to densify supervision without introducing brittle hand-crafted shaping. However, these designs remain vulnerable to evaluator gaming and distribution shift: as policies improve, they generate out-of-distribution reasoning patterns that can break learned evaluators, leading to unstable updates or misaligned shortcuts.

A second line of work explores causal-influenced credit assignment, treating tool calls and reasoning interventions as potential causes and estimating which decisions materially change outcomes via counterfactual rollouts, causal graphs, or influence-style attributions [

132]. In parallel, self-critique mechanisms embed an internal critic—often an FM-based verifier or revision loop—that tests, edits, or rejects intermediate steps before execution, converting sparse task rewards into richer self-generated supervision [

119]. These mechanisms can improve learnability in long-horizon settings, but they introduce new failure modes, including critic–policy collusion, over-optimization to the critique format, and increased compute and governance burden for auditing critic reliability at scale.

7.1.3. Scalability and Reliability of Human Feedback

High-quality human preference data remain expensive, inconsistent, and difficult to scale. RLAIF [

119] alleviates the annotation bottleneck but introduces new risks: synthetic feedback inherits the blind spots, cultural biases, and normative assumptions of the teacher models that generate it. As a result, feedback pipelines face a tension between scalability and representational fidelity. The lack of systematic tools for measuring these distortions complicates efforts to build durable and trustworthy alignment mechanisms.

7.1.4. Emergent Multi-Agent Dynamics

Large models increasingly interact with one another in multi-agent ecosystems—through communication, negotiation, shared tool use, or competitive tasks. These interactions can yield emergent behaviors such as collusion, deception, or manipulative strategies [

125]. Standard single-agent RL algorithms are not designed to detect or constrain such dynamics, and existing multi-agent RL techniques lack proven stability guarantees at FM scale. Without robust mechanisms for shaping cooperative norms and monitoring emergent strategies, FM-driven ecosystems risk producing unintended and difficult-to-audit behaviors.

7.1.5. Reproducibility, Transparency, and Governance Limitations

The field continues to face persistent reproducibility and governance gaps. Variation in pretraining corpora, reward model architectures, evaluator instructions, and computational budgets can significantly alter experimental outcomes [

43,

133]. These discrepancies hinder the comparability of results and limit the ability of auditors to evaluate alignment claims. Transparent reporting, standardized evaluation, and reproducible pipelines remain underdeveloped, creating barriers to responsible deployment in socially sensitive environments.

7.2. Unified DRL–FM Evaluation Framework

A recurring limitation in DRL–FM research is that evaluation practice does not match system complexity: agents are trained with multimodal perception, tool use, preference feedback, and long-horizon interaction, yet are often reported with narrow single-domain metrics. This subsection proposes a unified evaluation framework intended to be usable across classical control, embodied environments, and language-first agentic settings. The goal is not to replace existing benchmarks, but to standardize how results are reported so that claims become comparable across environments, feedback sources, and deployment contexts.

7.2.1. Design Principles

Cross-domain comparability: report a shared set of metric groups so results from control, web agents, and multimodal settings can be compared along common axes.

Closed-loop and offline evaluation: evaluate both interactive behavior under environment dynamics and offline behavior under fixed datasets or preference logs, because many systems mix both regimes.

Safety and robustness as first-class objectives: treat unsafe behavior, policy exploits, and adversarial fragility as primary outcomes rather than secondary notes.

Governance and reproducibility artifacts: publish minimum reporting details (seeds, compute, data, evaluator prompts, and reward-model settings) required to reproduce headline results.

7.2.2. Metric Groups and Minimum Outputs

We recommend reporting metrics in seven groups. Each group includes example measures that can be instantiated across environment types.

Capability and return: success rate, episodic return, task completion rate, constraint satisfaction rate, and trajectory-level goal completion.

Efficiency: environment samples to threshold, wall-clock time to threshold, training tokens, compute proxy measures, regret curves, and evaluation-time cost.

Generalization: performance under out-of-distribution splits, procedural generalization, tool or API shift, environment shift, and evaluator shift.

Alignment and helpfulness: preference win-rate, refusal correctness, harmlessness rate, truthfulness proxies, and instruction-following reliability under constraints.

Credit assignment quality: stability of step- or segment-level attributions under perturbations, consistency of identified causal steps across seeds, and sensitivity of outcomes to intermediate action edits [

19,

22].

Robustness and security: adversarial prompts, observation perturbations, reward-model attacks, jailbreaking resistance, and traceability checks such as watermark or provenance hooks when applicable.

Reproducibility: seed sensitivity, variance across runs, reporting of hyperparameters and reward-model details, and ablations that isolate the contribution of the FM and the reinforcement component.

7.2.3. Evaluation Protocol Template

To reduce ambiguity across papers, evaluation should explicitly specify:

Interaction mode: online, offline, or mixed, and the exact point at which preference or reward signals enter the loop.

Evaluator type: human, model-based, rule-based, or hybrid, including prompt templates and any safety policies used by evaluators.

Aggregation: mean and dispersion across seeds, and the number of independent runs used for reported metrics.

Failure analysis: a mandatory set of failure modes aligned with the benchmark blueprint in

Table 8.

7.2.4. Benchmark Blueprint

Table 8 provides a blueprint that links environment types to required metric groups, recommended protocols, and typical failure modes. It is intended as a minimum standard that authors can extend rather than a restrictive checklist.

7.2.5. Minimum Reporting Standard

To make results auditable and comparable, we recommend a minimum reporting standard that includes: (i) model and adapter details, including which components are frozen or fine-tuned; (ii) reward or preference pipeline details, including evaluator prompts and reward-model training data sources; (iii) training regime and compute proxies; (iv) number of seeds and variance measures; and (v) a short failure-mode report aligned with

Table 8. This standard is designed to be lightweight enough for survey-derived comparisons while still enabling reproducibility and governance review.

7.3. Future Research Directions

Solving these problems requires progress across modeling, optimization, evaluation, and governance. Foundation-scale world models offer one avenue: systems such as DreamerV3 [

9] illustrate how temporally coherent latent dynamics can support long-horizon credit assignment, reduce reliance on sparse scalar rewards, and stabilize optimization. Extending such techniques to FM architectures could provide shared state representations that integrate perception, reasoning, and action.

A second direction centers on self-reflective and self-improving agents. Reflection and critique mechanisms—such as iterative self-evaluation and revision pipelines [

95,

119]—may mitigate reward hacking, correct reasoning errors, and facilitate consistent long-horizon behavior. Embedding these loops within recurrent or memory-augmented architectures would provide structured pathways for internal error detection, enabling more robust credit assignment and reducing fragility in policy updates.

Further progress may arise from neurosymbolic reinforcement learning, which integrates logical constraints, causal structure, and symbolic rules with neural policy optimization. Such approaches offer pathways toward interpretability and verifiability, addressing governance and reproducibility concerns while improving robustness in high-stakes settings. Complementary work in federated and resource-efficient DRL aims to reduce computational cost and improve privacy-preserving deployment, which becomes increasingly important as FMs proliferate across distributed infrastructures.

Sustainability and energy efficiency represent additional priorities. Energy-aware training and evaluation—consistent with principles from Green AI [

134,

135]—should become integral to reinforcement learning objectives, with carbon- and compute-aware reward shaping enabling more responsible scaling trajectories.

Finally, the development of sovereign, culturally adaptive, and legally grounded alignment practices is essential for global deployment. Region-specific reward functions, inclusive preference datasets, and auditable oversight structures [

136] are critical for mitigating bias propagation and ensuring that reinforcement-trained models operate within diverse normative contexts. These directions suggest a research landscape in which DRL functions not only as an optimization tool but as part of a broader governance framework shaping the evolution of foundation models. Meanwhile,

Table 9 summarizes the challenges presented in this section and the corresponding future research directions.

8. Conclusions

The growing interplay between DRL and FMs marks a significant shift in how artificial agents perceive, reason, and act across complex environments. This survey examined how DRL complements the broad generalization, semantic priors, and multimodal capabilities of FMs, enabling systems that extend beyond passive prediction to become adaptive, interactive, and goal-directed. Across language agents, embodied control, scientific discovery, and societal alignment, the combined use of pretrained representations and reinforcement-based optimization has produced substantial gains in reliability, task efficiency, and long-horizon competence.

Furthermore, DRL–FM integration faces substantial technical and governance-related challenges. Optimization instability, limited credit assignment for language-conditioned tasks, and the difficulty of scaling high-quality human feedback continue to constrain system reliability. Addressing these shortcomings will require not only algorithmic advances but also transparent experimental reporting, inclusive evaluation practices, and stronger institutional mechanisms for oversight.

A practical takeaway of this survey is the unified DRL–FM evaluation framework introduced in

Section 7, which operationalizes cross-domain comparability through shared metric groups, protocol templates, and a benchmark blueprint that links environment types to expected evaluation outputs and failure modes. The framework supports more consistent comparison across model-centric, RL-centric, and hybrid systems, and enables stronger auditing of safety, robustness, and governance claims.

Looking ahead, progress will likely come from coupling foundation-scale world models and structured long-horizon reinforcement learning with more reliable feedback and evaluation pipelines, while treating safety, reproducibility, and compute constraints as design objectives rather than afterthoughts. Culturally grounded governance and reward design further suggest that alignment is context-dependent, so DRL–FM systems must be evaluated and audited under the norms and deployment conditions they will actually face.