1. Introduction

The “Stendhal Syndrome” mentioned in the title is the medical name given to a psychosomatic condition affecting some individuals when they visit locations of exceptional beauty or great historic importance. It is the same deep emotion that most educated people feel, but at a lesser degree, when visiting heritage masterpieces or historic places. The name derives from a report by Stendhal, pseudonym of the 19th century French writer Marie-Henri Beyle, the author, among others, of the famous novels

Le Rouge et le Noir (1830) and

La Chartreuse de Parme (1839). Reporting about a travel in Italy made in 1817 in his book

Rome, Naples et Florence (1826) [

1], he states that when visiting the Church of Santa Croce in Florence, he was deeply touched by the funerary monuments of so many great men, such as the artist Michelangelo, the astronomer Galileo Galilei, the opera composer Gioacchino Rossini, and many other famous Italians. Several of these tombs are not exceptional artworks, but the buried persons give them a special value: so, in this case it is history that makes heritage. Stendhal reports that he was not only impressed by such historical presence: “

I was in a sort of ecstasy, from the idea of being in Florence, close to the great men whose tombs I had seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of sublime beauty… I reached the point where one encounters celestial sensations…Everything spoke so vividly to my soul… I had palpitations of the heart… Life was drained from me. I walked with the fear of falling”. The impression gave him physical symptoms, which are nowadays called Stendhal syndrome. Stendhal quotes a contemporary poem by the Italian poet Ugo Foscolo who noted the exceptional value of the presence of the memory of so many notable persons in the Santa Croce church.

The poetic perception of the importance of the intangible background of monuments and sites, as described above, was not immediately recognised as important by heritage professionals, especially in Europe. Their attention focused on the tangible aspects, which were analysed and classified according to styles and artistic or architectural movements. Thus, the tombs mentioned by Stendhal were studied according to their shape and appearance, and not to the person who was buried there. Stendhal’s reaction was considered as a syndrome, something between a medical/psychological condition and the extreme sensibility of a poet. Thus, the style classification of heritage assets became a scholar’s approach to study tangible objects. This statement does not mean that this approach was negative: it was just partial and revealed as insufficient especially when applied to heritage outside Europe. Nevertheless, it led to important achievements as the

Athens Charter (1931) and the

Venice Charter (1964) [

2], produced by ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), which dictated important principles for the conservation and restoration of heritage property. However, the consideration that heritage assets, whatever their nature, consist of the inseparable combination of tangible aspects with intangible ones emerged soon. It is well described in a keynote lecture significantly titled “

The interdependency of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage” given by Mounir Bouchenaki, former Director General of ICCROM and Director of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, at the ICOMOS 14th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium held in Zimbabwe in October 2023 [

3]. The lecture may be summarised in its final statement: “

Both the tangible and the intangible heritage rely on each other when it comes to understanding the meaning and importance of each”. The

Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter [

4], first adopted in 1979 and revised in 2013, had already addressed similar issues, extending the

Venice Charter by providing standard guidelines for heritage conservation practice of places, which may have tangible and intangible dimensions. Conservation of places involves their cultural significance, i.e., the aesthetic, historic, scientific, social, or spiritual values for past, present, or future generations. Finally, the report

Innovation in Cultural Heritage Research [

5], published by the EU DG Research and Innovation in 2018 and illustrating the foundations of the 2018 European Year of Cultural Heritage, expressed in detail the same concept, applying them to the digitisation policy of the European Union.

The above-mentioned Burra Charter [

4] starts with a definition of places as follows: “Place means a geographically defined area. It may include elements, objects, spaces and views. Place may have tangible and intangible dimensions”. Places have cultural significance, i.e., “aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations”, which is “embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects”. This statement redefines Stendhal’s sentiment as the instinctive recognition of the cultural significance of the Santa Croce tombs rather than a psychological disease (a syndrome): in sum, it is the perception of the inseparable relationship between the tangible and intangible dimensions of heritage assets. It is not surprising that the Australia ICOMOS Charter proposed this extension of the previous concept of heritage asset to places: the mountain Uluru, a UNESCO World Heritage site also known with its English name Ayers Rock, is a sacred place for the Pitjantjatjara, the aboriginal people of the area, but it shows no features of what a perspective limited to tangible aspects would recognise as a heritage asset.

In the following sections, we will show how the above considerations substantially impact the digitalisation of cultural heritage, i.e., the documentation of cultural heritage by digital means aimed at its study and research, conservation, restoration, and valorisation towards a wide public. While this consideration is acknowledged—at least instinctively—by heritage scholars and professionals, it is less common in communicating heritage. Ignoring it may lead to unrespectful tourism practices and ultimately to overtourism, refusal of visitors by the indigenous population, and damages to heritage unconsciously caused by unaware tourists, who sometimes confuse heritage places with theme parks. Also heritage data collections often disregard this intangible dimension.

In the present paper we will show how this perspective can be captured by a Digital Twin approach in the framework of digitalised cultural heritage and stored into its data. This is not only an improvement in the semantic precision of data characterisation, but also the answer to a precise need as manifested in the above-mentioned documents: without it, the Digital Twin would lack an important component of its structure.

2. Digital Twins Today

Digital Twins (DT) made their appearance several years ago as a “living model” for NASA. Since then, they have come a long way, becoming nowadays a popular simulation model in many industrial sectors: Google Scholar mentions 23,000 related papers published since 2024, more than a thousand of which have appeared in January 2025. A recent book [

6] synthetically describes different DT applications, while a recent survey paper [

7] surveys and summarises industrial applications contributions. It defines a DT as “

comprised of three components:- (i)

Physical twin: A real-world entity (living/non-living) such as part/product, machine, process, organisation, or human, etc.

- (ii)

Digital twin: The digital representation of the physical twin with the capability to mimic/mirror its physical counterpart in real time.

- (iii)

Linking mechanism: The bidirectional flow of data between the two which operates automatically in real-time”.

With this definition, DTs continuously interact with the real-world, receiving inputs about the current status of the physical twin, and returning outputs about actions to be undertaken in the real-world or expected status of the physical twin. Thus, the focus is on simulation and action: the Digital Twin is designed to reproduce as faithfully as possible the relevant aspects of the physical twin, the real-world object it simulates. Information about other aspects may be disregarded: for example, the Digital Twin of a car to be used for autonomous/driverless driving may ignore aspects of the physical twin, which are irrelevant for the intended purpose, such as the fabric of the seats, the car colour, the owner’s gender and first name, and so on: the intended simulation guides the choice of the details to be incorporated in the Digital Twin and consequently its data structure.

On the other hand, DTs currently used for cultural heritage almost always refer to the physical component of the heritage asset. Three-dimensional models are the basis for such DTs, and in quite a few cases, they are considered the DT, with additional annotations attached to it [

8]. In this approach, the DTs are built on point-cloud models produced by 3D scans. Another research thread avails of HBIM, the heritage extension of BIM (Build Information Modelling) [

9], a documentation system created to assist the design of new buildings and the planning of related works. HBIM is based on a CAD procedure to reproduce the object shape and on a database containing the related information such as materials, services, and so on. An extensive and thorough analysis of the use of Digital Twins for built cultural heritage conservation is contained in [

10].

In the authors’ opinion, both such approaches have shortcomings. In the “augmented objects” approach, information is attached to specific points or regions of the 3D model. While there is no restriction on the attachments, and thus they might incorporate any kind of information including immaterial aspects (although in practice this never happens), there are two major issues: the connection between the “attachments” and the 3D model is unstable, as it may change when transforming the model, for example, by reducing its size via decimation or creating a different mesh via point interpolation. The second issue is that cross-referencing the information across different assets is (almost) impossible: for example, an attachment stating “this part of the object is made in wood” would refer only to a specific object, the one modelled. Searching for all objects with a part made in wood is impossible or at least is not envisaged as relevant because the focus of the investigation is on a single heritage object, the one modelled in 3D. Regarding HBIM models, extending to heritage-related data the original BIM database, designed to assist in the construction of new buildings is cumbersome and, in most cases, impossible. Thus, the related information is severely limited and, so far, never includes, even tentatively, any reference to the intangible component of the asset. Moreover, it works properly only for buildings, and its applicability to movable objects, e.g., statues, or to spaces as intended in the Burra Charter, is questionable and actually never attempted.

It is to overcome these critical aspects that we introduced in previous papers [

11,

12] what we called the Heritage Digital Twin (HDT) as the holistic assemblage of all the information pertaining to a heritage asset, intangible elements included. For the sake of completeness, the next section includes a short summary of the main features of the HDT ontology. The HDT is a compatible extension of the CRM (Conceptual Reference Model) ISO 2117:2023 standard [

13] used for the documentation of cultural heritage, maintaining semantic interoperability with the heritage documentation systems that adhere to that standard—in practice all the good ones.

If data should flow bidirectionally between the Digital Twin and the physical one, the HDT has been extended [

14] to the Reactive Heritage Digital Twin (RHDT), which incorporates in its schema

sensors, receiving inputs from the real-world in real time, and

activators, which push actions in the real-world. A very simple example consists of sensors receiving input from IoT devices, for example, a temperature measurer, which activates a fire extinguisher according to predefined rules. The activation is triggered by a dedicated

decider, a DT component that compares the measured temperature as transmitted to it by the sensor with pre-determined thresholds and orders the fire extinguisher to start action if the temperature is beyond a specific value. The

decider may also avail of AI-based procedures to take complex decisions [

15].

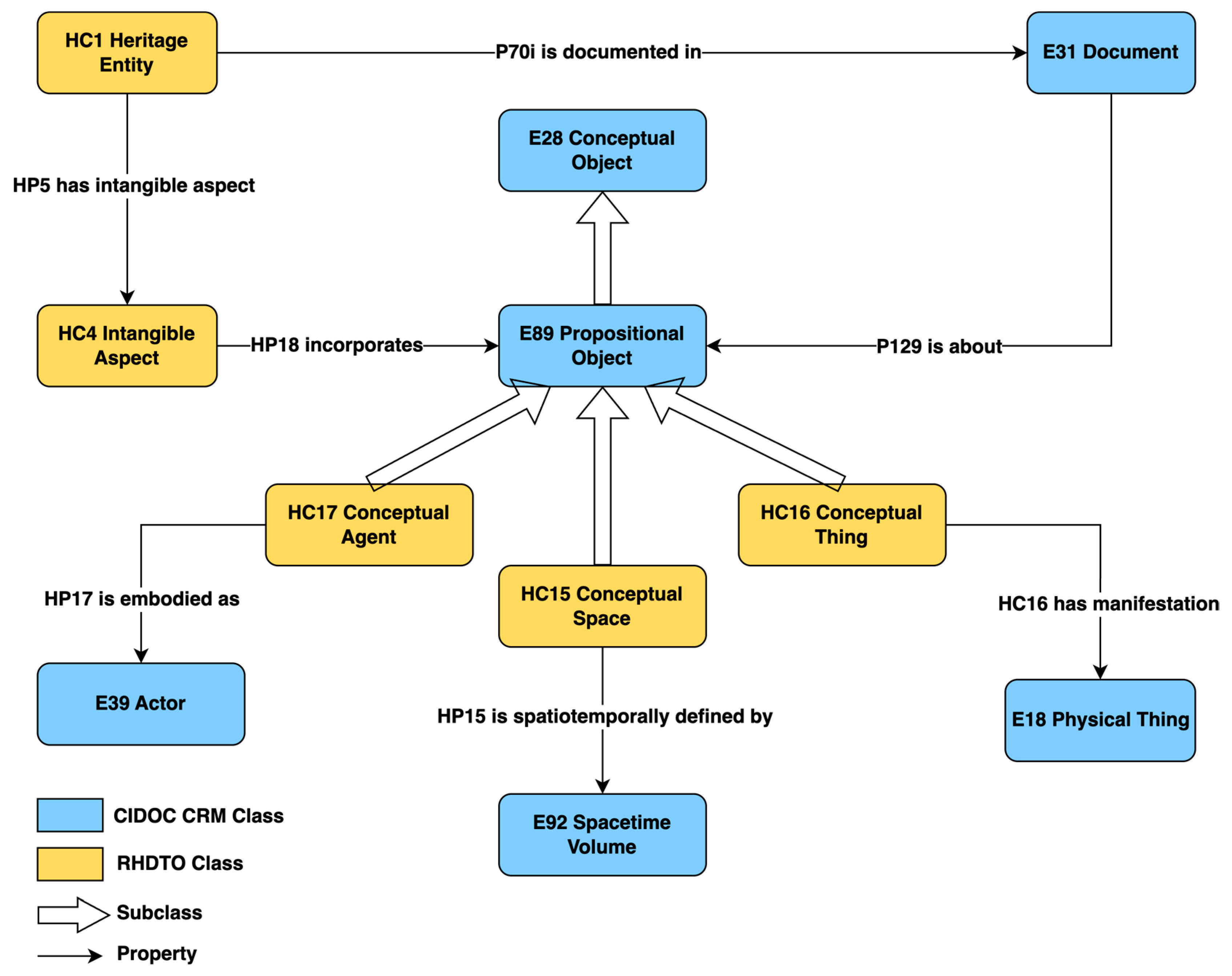

3. An Overview of the Heritage Digital Twin (HDT) Ontology and of Its Extension to Reactive HDT

The Heritage Digital Twin (HDT) ontology is designed to address the critical aspects outlined above. As a compatible extension of the CRM, the model is intended to represent a complete solution for managing and interconnecting the broad spectrum of data that forms the informational core of a Heritage Digital Twin. The ontology provides a high degree of interoperability in cultural heritage documentation and analysis, allowing for alignment with other research domains such as archaeology, art history, and architecture. It introduces a series of entities designed to express all available cultural and scientific documentation in a standardised format. Furthermore, it captures the dual nature of cultural heritage, encompassing both tangible and intangible aspects, and provides a mechanism for dynamically documenting and analysing their relationships. The HDT ontology is fully described in [

11,

12]. In the following, as is usual for ontologies, classes are identified by one or more capital letters followed by a number and a name; a similar approach is used for properties, identified by one or more capital letters followed by a number. The HDT and its extensions use the letters HC for the classes and HP for the properties.

Key classes in the model include HC1 Heritage Entity and HC3 Tangible Aspect, used to describe real-world entities, and an HC2 Heritage Digital Twin class meant to represent cultural Digital Twins as informative digital replicas. Other classes, such as HC4 Intangible Aspect, HC5 Digital Representation, and HC9 Heritage Activity, are employed to semantically model the intangible side of cultural entities and their documentation, along with specifically designed properties to articulate complex relationships with the places, people, objects, and events that constitute their historical and cultural significance. The HDT ontology also includes classes for modelling digital iconographic and multimedia representations, digital documentation elements, and activities related to the study and digital reproduction of cultural entities. It also provides features to represent the information relating to stories and narrations derived from documentation or oral tradition.

The HDT model was subsequently extended to also deal with the reactive part of the Digital Twins, consisting of the network of sensors, deciders, actuators, and other IoCT devices that ensure complex interactions with the real-world. Key classes introduced in the resulting R(eactive)HDT ontology model [

14] include

HC9 Sensor,

HC10 Decider, and

HC11 Activator, designed to model the IoCT capabilities of recording conditions, analysing input from various sources, and generating output instructions to trigger informed actions. In addition, the RHDT ontology provides specific classes to model aspects such as the placement of sensors, the software operating them, the measurements they perform, the signals generated, and the people responsible for ensuring the safety of cultural assets. Finally, a further extension to model AI components was analysed in [

15].

Within the framework of the RHDT ontology, the representation of intangible heritage represents an innovative aspect that allows the model to move beyond the mere cataloguing of physical attributes to embrace the sphere of cultural practices, historical events, and traditions. To this end, the HC4 Intangible Aspect class serves as a cornerstone, a semantic space designed to capture the very essence of intangible heritage, allowing it to reside within the Digital Twin as a fundamental and interwoven component of a comprehensive representation. The class is conceived as a template for the documentation of traditions and events, a generic representation that embodies the essence of cultural manifestations, since it acknowledges the continuity and adaptability of intangible heritage and its capacity to evolve while retaining its core identity. The connection between the tangible and intangible is then thoughtfully articulated through the HP5 has intangible aspect property, a bridge that semantically links the physical dimension of a heritage asset to the intangible values it embodies. This property is crucial for understanding the full cultural context of a tangible object, informing the Digital Twin that its relevance is not solely determined by its physical properties, but also by the traditions, stories, and practices it represents.

Further elaborating on this connection, the

HP7 is manifestation of property identifies a reciprocal link to denote the instances in which an intangible aspect is made manifest. This interplay between specific events and their more abstract counterparts is further refined by the introduction of the property

HP6 has manifestation event property, which allows for a more direct connection between the abstract representation of an intangible aspect and its concrete expressions in time and space. The ontology also expands to the realm of narratives through the use of the Narrative Ontology (NOnt) introduced in [

16], whose classes are employed to represent stories as components of intangible heritage. These are not just records of past events but are understood as dynamic constructions contributing to the social and cultural significance of a heritage entity. This approach makes the RHDTO capable of highlighting the ways in which these narratives are expressed and transmitted, recognising the importance of different modes of communication in preserving and conveying cultural knowledge. It ensures that intangible aspects are not treated as mere addenda but are semantically interwoven with the tangible dimensions of cultural heritage, allowing for a more comprehensive and interconnected representation of the cultural assets within the Digital Twin.

4. The Concepts of Place and Space in the CRM Ontology

As previously noted, the concept of place as defined in the Burra Charter is of fundamental importance for cultural heritage information. At first sight, “place” seems a very simple concept and is considered as such in the CRM [

13] standard. The CRM uses the letter E for the classes and P for the properties. All the CRM definitions and concepts are documented in dedicated sections of the CRM web site [

13], which can be searched for the item concerned.

The CRM defines the class E53 Place as “extents in space, in particular on the surface of the Earth, in the pure sense of physics: independent from temporal phenomena and matter”. It works well in statements such as “The Leaning Tower is located in Pisa”, where Pisa is the place. There are however limitations to a fair use, as shown by the following—somehow humorous—example. The famous Windsor Castle, a royal residence, is located at Windsor, in the English county of Berkshire. Its construction dates back to the 11th century. So, its place is “County of Berkshire”. The Heathrow airport is located in the London Borough of Hillingdon, a borough of the Greater London. It started operations in 1929 as a small airfield. Its place is therefore “Borough of Hillingdon”. The two locations have a common border, and the distance between the castle and the airport is actually about 9 miles (15 km) by road, and 6.7 miles (10.7 km) if measured as the crow flies. An ignorant (or perhaps just humorous) tourist asked on the web “why they built the Windsor Castle so close to the Heathrow airport”. The question was not unfounded, because the concept of place does not bring the notion of time and the two places, the Windsor Castle one and the Heathrow Airport one, are very close to each other. To resolve this issue (and perhaps also more serious ones) is why the CRM introduced the more precise class E92 Spacetime Volume, which comprises four-dimensional point sets (volumes) in physical spacetime, i.e., the extent of a material phenomenon in space and time. If the location of the above two spaces (Windsor Castle and Heathrow airport) is considered as a spacetime volume, the Windsor one extends in the space occupied by the castle and in the timeframe from circa 1200 AD onwards, while the Heathrow one extends in the space occupied by the airport and in the period from 1929 AD onwards. In both cases, the spaces occupied vary in time, for example, as concerns Heathrow, where the growth of the airport increased the space occupied by it at precise dates; however, the two locations remained close to each other only since the beginning of existence of the Heathrow airport in 1929. Thus, the concept of spacetime volume greatly improves the precision of the information and avoids misconceptions as the one mentioned in the above joke, or in other more serious ones, for example, when referring to “Rome” without specifying if it is intended the Roman age Rome, the medieval one, or the present time capital of Italy: the spacetime volume resolves this ambiguity.

One might ask if such spacetime volume concept may also describe the concept of place as defined in the Burra Charter. As already mentioned, the Burra Place is defined as a geographically defined area, with tangible and intangible dimensions, having cultural significance, i.e., aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value: none of these elements is referred in the CRM concept of spacetime volume, which incorporates only measurable aspects such as space and time, both somehow material as they belong to physics. A solution is proposed in the next section.

5. Heritage Place as a Conceptual Object

Besides being insufficient to manage the Burra Charter concept of (heritage) place, the CRM approach to places also differs from the one adopted in gazetteers, notably in the

Pleiades gazetteer.

Pleiades [

17,

18] is probably the most extensive and complete gazetteer of ancient places, mainly conceived for historians and archaeologists. It has extensive coverage for the Greek and Roman world, the Ancient Near Eastern, Byzantine, Celtic, and Early Medieval geography. Pleiades distinguishes between

places, which are constructed by human experience, and

locations, i.e., concrete, objective spatial entities, i.e., a portion of space on the Earth. This differs from the CRM definition of

E53 Place, i.e., “an extent in space, in particular on the surface of the Earth, in the pure sense of physics” (which rather corresponds to the Pleiades location), as well as from the already mentioned CRM definition of

E92 Spacetime Volume. E53 also does not fit with the Burra definition of place as mentioned above. Thus, a new class should be introduced to capture the cultural and historical significance of places.

This distinction reflects the dualism between two foundational categories of spatial objects, defined as follows. Smith [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] introduced the distinction of two foundational types of boundaries of physical entities, on which a top-level distinction between spatial entities is based on

bona fide boundaries, i.e., natural or mind-independent boundaries, which are physical boundaries in the objects themselves that exist independently from human perception, and correspond to the CRM approach; and

fiat boundaries, i.e., artificial or mind-dependent boundaries, which are non-physical boundaries, that depend on human decision or considerations and are the products of mental activities, i.e., the approach of gazetteers and heritage-related space definitions such as the Burra Charter.

However, the CRM has a class which in our opinion may be suitable to address the semantic issues contained in the Burra definition of place: the class E28 Conceptual Object, which comprises “non-material products of our minds and other human produced data that have become objects of a discourse about their identity, circumstances of creation or historical implication (…) They exist as long as they can be found on at least one carrier or in at least one human memory. Their existence ends when the last carrier and the last memory are lost”. Moreover, this E28 has a subclass, the E89 Propositional Object, a refinement of it, defined as comprising “immaterial items, including but not limited to stories, plots, procedural prescriptions, algorithms, laws of physics or images that are, or represent in some sense, sets of propositions about real or imaginary things and that are documented as single units or serve as topic of discourse”. Such refined class improves the precision of the classification as it excludes other concepts such as Type and Appellation that also belong to E28. Availing of this E89, we define a new subclass of E89, called HC15 Conceptual Space, as “the complex of information referring to an extent of space and the related aesthetic, historic, scientific, social or spiritual value for past, present or future generations embodied in the place itself, its fabric, setting, use, associations, meanings, records, related places and related objects”. It may be noted that this definition copies almost verbatim the Burra Charter definition of cultural significance and of place. It is unfortunate that the term “place” has a meaning in the CRM as in the definition of the class E53 Place, which concerns “extents in space, in particular on the surface of the Earth, in the pure sense of physics”, while elsewhere “place” refers to a much wider concept as in the Burra Chapter. Thus, to avoid misunderstandings when operating within the CRM semantic framework, we prefer to use the term “space” in the new class name.

This newly defined class better represents the Burra Chapter definition of places and the Pleiades concept of place. It may refer to an ample variety of cases: imaginary “places” such as Atlantis or Peter Pan’s Neverland, as well as places set up by human feelings but linked to a physical space. The latter is the case of Uluru/Ayers Rock, where a whole community refers to it as a sacred space, and it applies to many other circumstances, as shown in the examples described below. A conceptual space may also have a location, a spacetime volume linked to the conceptual place, for example, in the Uluru/Ayers Rock case, the geographical region comprising the mountain and the time span extending from the beginning of the cults related to the place until today. The (bona fide) borders of the location may be fuzzy, which is perfectly acceptable according to the CRM scope note (i.e., the definition) of spacetime volume.

In sum, to fit with the needs of cultural heritage documentation, we think that it is necessary to introduce a new spatial concept, the conceptual space defined above. It has fiat borders, i.e., borders defined by human decisions or considerations and are the products of mental activities. Accordingly, this new conceptual space is a specialisation (a subclass) of the CRM E89 Propositional Object.

Examples show that conceptual spaces belong also to the cultural heritage of regions like Europe, where the tangible component has had an overwhelming importance until recently.

The conceptual space models the cause of Stendhal syndrome. This feeling derives by regarding the Santa Croce church as the complex of the considerations about the great humans buried in it, rather than the physical building, which is instead the location of such conceptual space. This approach further explains the title of the present paper.

Another clear example is provided by the

Heritage Routes promoted by the Council of Europe [

23,

24], which show a “journey through space and time” demonstrating “a shared and living cultural heritage” among different countries and cultures of Europe. The subjects of such routes range from music (the

Mozart Ways) to agriculture (the Route of

the Olive Tree and the

Iter vitis), arts and crafts (

Ceramics,

Art Noveau,

Impressionisms), artists and scientists (

Leonardo da Vinci,

Le Corbusier,

Alvar Aalto), and more.

We consider one of the most famous of these routes, the pilgrimage itinerary of the “

Camino de Santiago”, the

Santiago de Compostela Pilgrim Routes [

24], also known as Saint James Way, as it well expresses the above-mentioned mixture of tangible and intangible aspects. It concerns the Christian pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint James in Santiago de Compostela (Spain), which started in the Middles Ages and is still alive today. The Spanish and French parts of the

Camino are also included on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Completing the pilgrimage guarantees a plenary indulgence to pilgrims. As a result of this pilgrimage, a rich heritage was formed in time. Tangible heritage such as places of worship, hospitals, accommodation facilities, bridges, as well as non-tangible heritage in the form of myths, legends, and songs are present along the Santiago Routes. The religious aspect is also part of this intangible component. The

Camino location is rather fuzzy as there is no specific and detailed indication on a precise route to reach Santiago: the pilgrimage’s route is rather a category of the spirit rather than a place in the CRM sense. Of course, the general definition of the pilgrimage must abstract from individual choices and feelings, and document opportunities or typical activities along way. If such activities may be carried out at specific locations or buildings (a church or chapel, for example), these should be defined individually as heritage assets, possibly worth owning their own Digital Twin. In conclusion, the

Camino comprises the pilgrimage itinerary description, the physical route, the pilgrims’ religious beliefs, how they carry out the pilgrimage, and what they do during it. The Camino develops mostly in Western Europe through the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Spain, with a Portuguese extension, although there are also places in Europe, e.g., in Poland, Latvia, and Italy, which refer to the devotion to the saint. It is worth mentioning that a single, official version of the Camino’s route does not exist. The paths have changed over centuries, and the precise itinerary depends on historical sources, regional interpretations, and even personal choices made by pilgrims. Various organisations, including UNESCO, the already mentioned Council of Europe, and local associations such as the European Federation of Saint James Way [

25], provide descriptions and maps of the routes, each with its own perspective and level of detail. For example, UNESCO highlights the French and Spanish routes recognised as World Heritage Sites, while other institutions like the Council of Europe and the European Federation of Saint James Way, emphasise the

Camino’s cultural and historical significance as a European Cultural Route or focus on providing detailed guides and practical resources for pilgrims.

Figure 1 aims at providing a general overview of such routes.

This example shows some relevant aspects of the analysis of the “place” general concept. They show that there are places which are not simply “a geographic concept”, as they take their heritage value from beliefs shared by a community. The granularity of this background community, and its importance, are largely discretional.

As already mentioned, a conceptual space may refer to some extent in space on the Earth defined with a more or less precise definition, its location. The Camino de Santiago concerns a broadly defined part of Europe which has fuzzy borders and came to existence in the Middle Ages. Similarly, Uluru/Ayers Rock is a mountain with relatively indetermined borders in Australia and became a sacred place when humans started inhabiting Australia. So, both refer to a spacetime volume. We will represent this aspect with the property HP15 is spatiotemporally defined, with HC15 Conceptual Space as domain and E92 Spacetime Volume as range.

The intangible component of a heritage asset may include other aspects rather than a specific spatial location. While there is always a conceptual element behind it, its reification may concern an object, for example, a religious icon, the relics of a saint, a national flag, a set of memorabilia (“objects that are collected because they are connected with a person or event that is thought to be very interesting” according to the Cambridge Dictionary definition), and so on. In such cases, the object is not relevant per se, but for what it symbolically represents. We will use for this kind of objects the class HC16 Conceptual Thing to include both the tangible and intangible component. A conceptual thing is linked to the object it refers to by the property HP16 has manifestation, with domain HC16 Conceptual Thing and range E18 Physical Thing.

In other cases, what embodies the cultural value is a living being or a group thereof. It may be a person who lived in the past or one who is still alive, or a group. This case will be modelled with the class

HC17 Conceptual Agent. This concept was introduced in the UNESCO definition of intangible heritage [

26]. The property which represents this relationship is defined as

HP17 is embodied in, with the class

E39 Actor as the range: Actor, in the CRM context may represent a person or a group (respectively,

E21 Person and

E74 Group). Note that the three cases illustrated above, i.e., conceptual space, conceptual thing, and conceptual agent, may refer to the same conceptual object. For example, the

Camino de Santiago can be regarded as a conceptual space (the itinerary), a conceptual thing (the complex of the heritage physical assets along the way and at destination, for example, the Saint’s relics), and a conceptual agent, the saint himself.

6. The Extended HDT Model

In the HDT vision, a Heritage Digital Twin is mainly composed of all the available information about the real-world cultural entity it aims to reproduce. In this perspective, documentation is the main source through which the intangible aspect of the replicated cultural entity is witnessed within the HDT. Documentation, thus, needs to be properly addressed to capture the complexity and deep significance of its intangible sphere. To this aim, in the ontology, we managed to improve the features provided by the existing HC4 Intangible Aspect class to capture detail about intangible spaces, objects, and people that hold significant cultural and symbolic value in an improved semantic form. In turn, we defined new ways for linking these intangible aspects to their real-world counterparts.

6.1. Conceptual Spaces

As already outlined, conceptual spaces exist within documentation as objects of discourse living in a non-spatial and atemporal dimension, while obviously retaining the potential to refer to real places having actual manifestation in space and time. From an ontological point of view, conceptual spaces can be better approximated as propositional objects in the sense of the CRM, i.e., as immaterial sets of propositions about real or imaginary things that, similarly to the CRM conceptual objects, are documented or communicated between persons, and continue to exist on multiple carriers simultaneously as long as they can be found on at least one carrier, or in at least one human memory. We therefore propose a new class for modelling conceptual spaces, tentatively defined as follows:

HC15 Conceptual Space

Subclass of: E89 Propositional Object

This class comprises non-material, intangible entities that represent places or locations as they exist within the realm of discourse, memory, and cultural practices. They are created by individuals or communities and become objects of discourse about their identity, function, and historical implications. Unlike physical spaces, which have a tangible and geographically defined presence, conceptual spaces have their roots in the HDT documentation, which may include written documents, oral traditions, artistic representations, and collective memories. They typically hold significant cultural and symbolic value, contributing to the collective identity and heritage of a community.

As an example of conceptual space, we can think to the already mentioned sacred space of Ayers Rock, designated out of reverence by the indigenous community and existing within the realm of collective memories and oral traditions (as witnessed, for example, in stories and audiovisual or media documentation) rather than solely in its physical form. The sacredness of this conceptual place is maintained through cultural practices and ceases to hold symbolic significance if these memories fade, even if the actual place to which this intangible value refers, continues to exist in space and time, together with the physical object (the rock) located there. The Uluru/Ayers Rock and the Heritage Routes examples offer a different set of examples for the conceptual space class.

To describe the relations that may exist between a conceptual space and its actual corresponding spatial manifestation in the real-world, we also introduced a new HC15 property, defined as follows:

HP15 is spatiotemporally defined by

Domain: HC15 Conceptual Space

Range: E92 Spacetime Volume

This property establishes a relationship between a conceptual space (HC15) and the real-world spatiotemporal volume (E92 Spacetime Volume) to which it is directly related. In particular, it specifies that a conceptual space, while existing in an intangible, conceptual dimension within the realm of discourse and memory, could have a corresponding manifestation as physical place and timeframe that can be defined in terms of a spacetime volume. This property emphasises the dual nature of spaces, which can exist both as non-material products of the mind and as physical places that can be geographically and historically contextualised.

As an example, Uluru/Ayers Rock

HP15 is spatiotemporally defined by a portion of space represented in

Figure 2. For this example, defining a temporal range may be more difficult as it refers to oral sources. Most studies date back the aboriginal religious beliefs to 10,000 BCE. Properties such as

P70 is documented in and

P129 is subject of can be used to establish relationships between a conceptual space (

HC15) and the documentation (

E31 Document) in which it is described, mentioned, or otherwise reported within a specific textual, visual, or multimedia source, thus highlighting the role of documentation in sustaining and transmitting its cultural and historical value.

Documentation about Uluru/Ayers Rock is more difficult to exemplify, as it resides in the minds and beliefs of the local native population. Instead, the Heritage Routes may rely on a large set of documents, from religious to heritage related ones, the latter being connections to other related heritage assets.

6.2. Conceptual Objects and People

As previously noted, cultural objects and people can also show an intangible dimension, going beyond their physical nature. As in the case of conceptual spaces, these conceptual entities exist primarily within the realm of discourse and are sustained through various forms of documentation. Therefore, they need to be defined with new specific classes and properties to describe and associate them with the corresponding real-world entities they refer to. For instance, physical objects that are the focus of specific cults or historical relevance (e.g., orthodox icons, relics of saints, objects belonging to relevant historical figures) possess a conceptual side deriving from mentions or descriptions of them in written or oral documentation. Similarly, historical figures celebrated or remembered through documents, narratives, and artistic representations should be distinguished from the related real historical persons who lived and actively participated in historical events. In this perspective, the E18 Physical Thing and E39 Actor classes of the CRM seem inadequate to model entities of this kind, since they refer exclusively to real objects and people rather than conceptual or symbolic representations. Also in this case, we propose to model these intangible entities by means of subclasses of E89 Propositional Object, as we did for the conceptual spaces defined above. In particular, we propose the following two new classes:

HC16 Conceptual Thing

Subclass of: E89 Propositional Object

This class encompasses entities that acquire cultural, symbolic, or intellectual significance independently of their material form. These include conceptual representations of real-world objects or legendary artefacts expressed through documentation. Unlike physical objects, their identity is shaped by discourse, representation, and transmission across different media and traditions, and are instantiated through written accounts, oral traditions, iconographic depictions, or digital representations, ensuring their persistence within cultural memory. Their identity remains intact even if their material manifestations are lost or altered, provided they continue to be referenced, interpreted, or reconstructed within the cultural discourse.

An example of this class is the complex of funerary monuments in the Santa Croce church in Florence, not considered only as artistic artefacts, but as the subject of a discourse about notable Italians.

HC17 Conceptual Agent

Subclass of: E89 Propositional Object

This class refers to historical, legendary, or fictional individuals whose identity and significance transcend their physical existence. These figures are constituted through collective memory, literary narratives, artistic representation, and ideological constructs rather than direct biological lineage or material evidence. Conceptual persons may include deified heroes, mythical founders, or fictional protagonists, as well as documented representations of historical individuals when expressed within specific narratives or symbolic frameworks. Their continuity relies on being referenced within traditions, texts, or artistic expressions, allowing their legacy to persist even in the absence of tangible proof of their existence.

The figure of Stendhal exemplifies very well the nature of what a conceptual agent could be, existing simultaneously as a historical figure and a literary construct. While the man Stendhal lived and wrote, the conceptual Stendhal persists through the centuries, shaped by literary tradition, cultural memory, ideological reinterpretation, and the famous Syndrome named after him.

To articulate the relationships of conceptual things and conceptual agents with their real-world counterparts, the new, extended version of the RHDT ontology includes a set of new properties. Their scope notes are described below.

HP16 has manifestation

Domain: HC16 Conceptual Thing

Range: E18 Physical Thing

This property establishes a relationship between a conceptual thing (HC16) and the physical thing (E18) that serves as its tangible manifestation. It can be used to associate conceptual entities, such as legendary artefacts, symbolic objects, or documented representations of physical things, with their corresponding material instances. This linkage enables a structured understanding of how conceptual entities interact with the physical world, indicating that while conceptual things exist primarily in discourse and documentation, it may have one or more physical embodiments that materialise its symbolic, cultural, or intellectual significance.

HP17 is embodied as

Domain: HC17 Conceptual Agent

Range: E39 Actor

This property establishes a relationship between a conceptual agent (HC17) and an Actor (E39) who is recognised as its real-world counterpart. The property enables the documentation of relationships between conceptual agents and historical figures, such as cases where legendary characters are linked to real individuals or where cultural traditions associate a symbolic identity with a known person, thus facilitating the study of historical reinterpretations, attributions, and the evolution of conceptual agents in collective memory.

6.3. Empowering the HC4 Intangible Aspect Class

As we stated at the beginning of this section, the HC4 Intangible Aspect class is a key component of the RHDT ontology and plays a central role in capturing the non-material dimension of cultural heritage, incorporating it in its digital representations. In this regard, HC4 functions as an overarching category that incorporates specific types of conceptual entities, such as spaces, objects, and people, that exist within documentation and collective memory, ensuring that they are adequately represented as living elements of discourse. To express this ontological relationship, we introduce the HP18 incorporates property, defined as follows:

HP18 incorporates

Domain: HC4 Intangible Aspect

Range: E89 Propositional Object (includes HC15, HC16, HC17 as a superclass of such classes)

This property establishes a relationship between an intangible aspect (HC4) and one or more propositional objects (E89) that contribute to its conceptual structure. In particular, it provides a semantic way to describe how cultural narratives, symbolic representations, and conceptualised historical entities contribute to the formation of intangible aspects of cultural heritage. This property indicates that an intangible aspect, as represented in documentation and cultural memory, can subsume or encompass specific conceptual entities such as conceptual spaces, conceptual things, and conceptual agents, effectively linking them to broader intangible heritage dimensions.

The new classes and properties described in this section are represented in the diagram in

Figure 3.

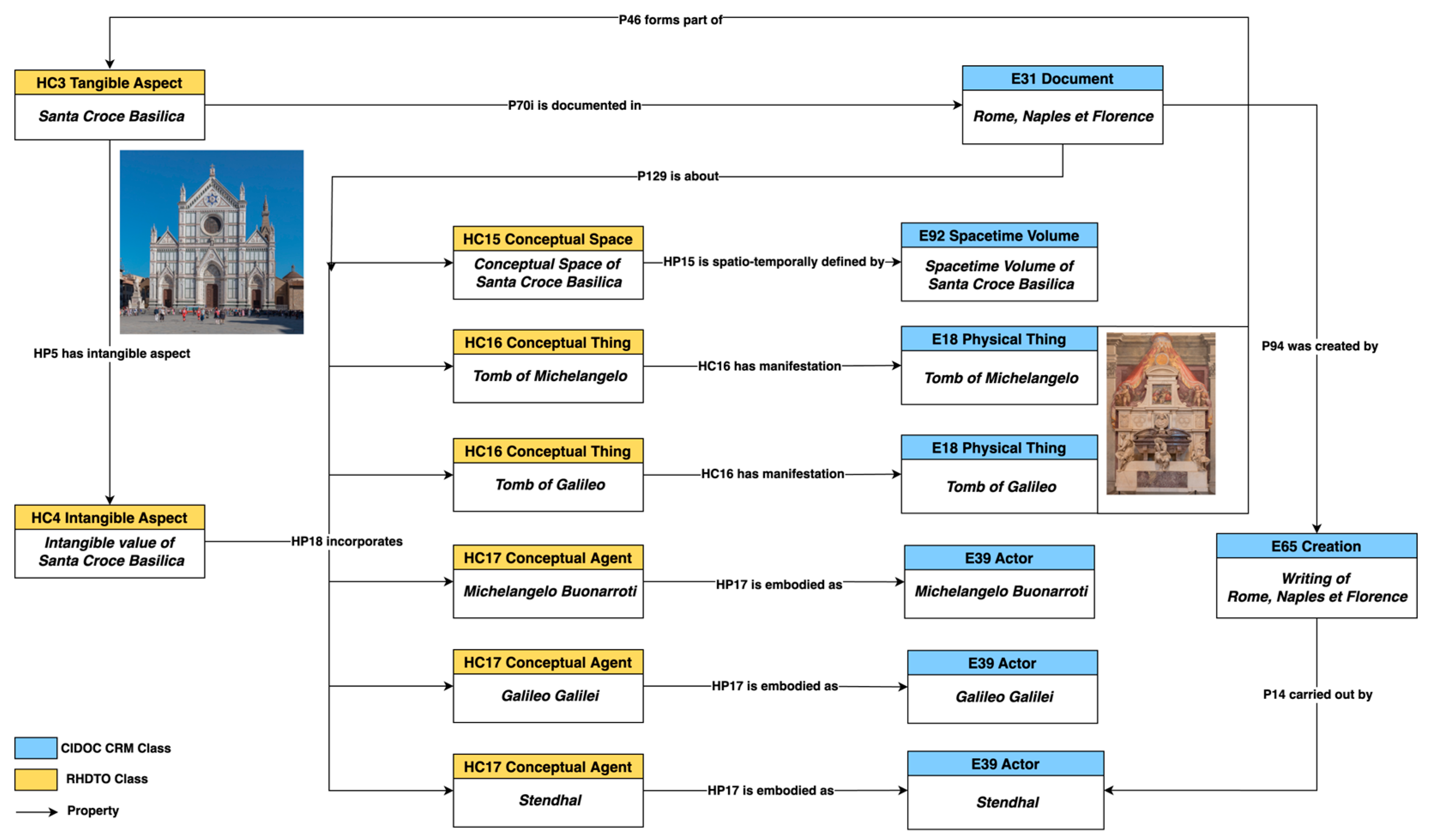

6.4. An Example: Stendhal in Santa Croce

In this section, we will develop the semantic representation of the example of the Santa Croce church and Stendhal syndrome mentioned above. The visit of Stendhal to the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence, which we cited in the opening of this paper, provides a vivid illustration of the interplay between physical heritage and its conceptual extensions in narrative and cultural memory. The story, reported in his book

Rome, Naples et Florence, has in fact the power to transform this historical monument into a conceptual space (

HC15), existing independently of its tangible architectural structure (

HC3 Tangible Aspect). Santa Croce thus becomes an object of discourse shaped by the literature (

E31 Document), which serves as carriers of its intangible significance. If we consider that in addition to Stendhal’s work, there are obviously many other literary, historical, and artistic documents in which it is possible to recognise the same conceptual space of Santa Croce, it is easy to realise how this conceptual element becomes a central node of its intangible aspect, representing an aggregating node within the documentation of the Digital Twin (the HDT) of this famous monument. We mention also the fact that Stendhal’s feelings of reverence were mentioned in the previous literary work

I Sepolcri (

Sepulchres) by the Italian poet Ugo Foscolo [

27], some verses of which are also verbatim quoted in Stendhal’s text.

Ontologically, the relationship between the conceptual and the spatiotemporal manifestation of the church can be formalised through the property

HP15 is spatiotemporally defined by, linking the conceptual space of Santa Croce to its real-world spacetime volume (E92), i.e., its physical presence in Florence, existing over a defined period of time (see

Figure 4).

Within this space, Stendhal saw and described the tombs of Michelangelo (see

Figure 5), Galileo, and other celebrated individuals. These tombs are obviously physical entities (

E18), made of marble and still visible today. But in the act of literary representation, they assume a second identity, becoming conceptual things (

HC16) linked to the material monuments, but persisting beyond their physical form. The property

HP16 has manifestation captures this duality, linking the conceptual thing (

HC16) of Michelangelo’s and Galileo’s funerary monuments to the actual physical objects (

E18) located in Santa Croce. This illustrates how material objects can be reinterpreted, documented, and reimagined across different media, to reinforce their conceptual dimension.

The figures commemorated within these tombs undergo a similar transformation. Michelangelo and Galileo were historical persons (E39 Actor) who lived, acted, and influenced their world. However, as they are reintroduced in Stendhal’s account, they take on a different ontological status, i.e., the intangible value of the memory, an aspect that can be modelled by means of the HC17 Conceptual Agent class. Indeed, this is precisely the memory of the great men of the past that triggered in Stendhal his famous syndrome. The property HP17 is embodied as allows to link the conceptual representations of Michelangelo and Galileo to their historical counterparts.

As already mentioned, another important aspect of this ontological modelling is represented by Stendhal himself. As a real historical person (E39 Actor), he physically visited Santa Croce and recorded his impressions. However, within his own narrative, he also created an intangible version of himself, a conceptual agent (HC17) who narratively experienced and interpreted Santa Croce, filtering reality through subjective reflection. The distinction between author and narrator highlights the role of documentation in shaping how places, people, and objects are understood, generating the intangible value of sites and monuments, as in this case occurs to Santa Croce.

Finally, the church, the tombs, and the historical figures all exist as intangible aspects (HC4) of the cultural heritage entity (HC3), relating the physical world to its conceptual representations. The property HP18 incorporates expresses this connection, showing how the intangible aspect (HC4) of Santa Croce encompasses its conceptual spaces, things, and agents, preserving its significance in the context of the documentation of the Digital Twin of the church, in which it is described not only as a merely physical structure but, highlighting its immaterial aspects, as a conceptual entity that functions as a repository of historical values, artistic memory, and cultural significance.

The diagram in

Figure 6 illustrates with a graph the ontological representation of the concepts expressed above by means of the classes and properties of the RHDT ontology model. To keep the diagram readable by a human, only some of the relationships and classes are shown as examples of a more complex structure: this problem does not exist, of course, when the semantic graph is loaded into a computer using, for example, RDF encoding.

7. Discussion and Further Work

In this paper, we have analysed several examples of places that must actually be considered as conceptual objects, such as Uluru and the Santiago Routes. Further work will analyse more examples of HC15 Conceptual Space with reference to relevant concepts used in cultural heritage practice. One significant example could be the concept of landscape as defined in the Landscape Convention [

28], which combines physical, cultural, living, and human elements reflecting a common identity.

Regarding the above-mentioned Santa Croce church, there is a clear tangible component which can be modelled as such using the RHDT ontology. Historical elements such as its Gothic character may also be included as additional knowledge about its architectural features. Its Digital Twin could include information to monitor the church elements such as columns, capitals, paintings, and so on, availing of the RHDT (Reactive HDT) ontology [

14,

15].

On the other hand, Santa Croce owns also an intangible dimension with many components. One is of course the religious component, being a Catholic church. Its relationship with the Franciscan order is related to this aspect. The causes of Stendhal syndrome add a further dimension to its intangible component. All these intangible aspects may be properly documented in the RHDT model using the HC15 Conceptual Space class and the other related classes. The visitor’s awareness level is of course subjective: visitors must understand what a church is in the Catholic religion, and probably also the importance of Saint Francis and his reforms. To a deeper understanding of the cultural values related to Santa Croce, which caused Stendhal sentiments, knowledge about the famous people buried in the church sepulchres is moreover required. Properly documenting them in the knowledge base built on RHDT (and its extensions) is a step in this direction.

RHDT also supports historical research and the conservation of the monument by connecting this church (as well as other monuments and artefacts, of course) to the knowledge of conservation activities carried out on other artefacts somewhere else. This topic is the subject of the EU-funded research project ARTEMIS [

29], just started on 1st January 2025, which relies on a knowledge base driven by the RHDT ontology and aims at exploring the feasibility of “virtual” artwork and monument restoration founded on the data stored in its knowledge base. In ARTEMIS, the authors of the present paper are in charge of setting up such semantic infrastructure, implementing the RHDT concepts in practice.

Finally, the information contained in RHDT may also support valorisation, being the starting point to develop stories for visitors and providing access to material to compose visual explanations, with the additional advantage that the communication content would be compliant with principles such as the

London Charter [

30,

31,

32], which requires that every computer visualisation of cultural heritage be based on scientific bases. We have not explored this opportunity so far, and plan to do so in future research.

The above considerations suggest future work to improve the fit of the semantic description to the needs of heritage documentation. It will be necessary to improve the instruments required to organise space-based information, starting in the present paper with the notion of conceptual space. Since most of the immaterial concepts are based on narration and beliefs, these two areas are a clear target for a further expansion of the RHDT ontology. The CRM framework and its extensions provide the context in which such expansion may be designed in a compatible and interoperable way, demonstrating the power of digitalisation for the comprehension, documentation, study, conservation, and valorisation of cultural heritage. We do hope that the Heritage Digital Twin approach will support these achievements.