1. Introduction

This work aims to create a learner’s dictionary by automatically identifying the most appropriate combinations of words that are commonly used in spoken language and whose meanings are not literal. These word combinations, called collocations, are of fundamental importance in learning a language and often represent a significant barrier for learners to overcome. A collocation consists of two or more words within a sentence that have a semantic meaning different from the literal interpretation of the two terms and are used, often unconsciously, in both written and spoken language [

1,

2,

3].

The Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) communities have extensively studied collocations, particularly in English, due to their significance in language learning and communication [

4,

5,

6]. Multi-word expressions (MWEs), encompassing constructs such as collocations, idioms, and lexical bundles, are lexical units formed by two or more words [

7].

Significant progress has been made in developing resources, such as collocation dictionaries tailored for second-language (L2) learners, primarily for English [

5,

6]. At the same time, general collocation dictionaries, which are not explicitly aimed at L2 learners, exist for several languages, including English [

4] and Italian [

8,

9,

10]. The application of language corpora has greatly advanced the investigation of phrases and their lexicographical use. In particular, corpora have been used in identifying recurring word combinations. Such corpora leverage NLP and statistical methods to uncover patterns in vast text datasets [

11].

Extracting MWEs from corpora involves two key tasks [

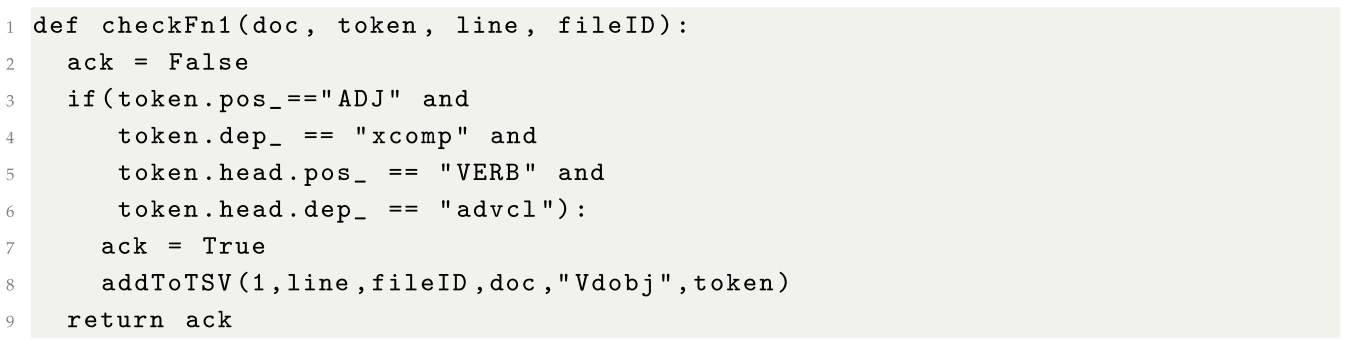

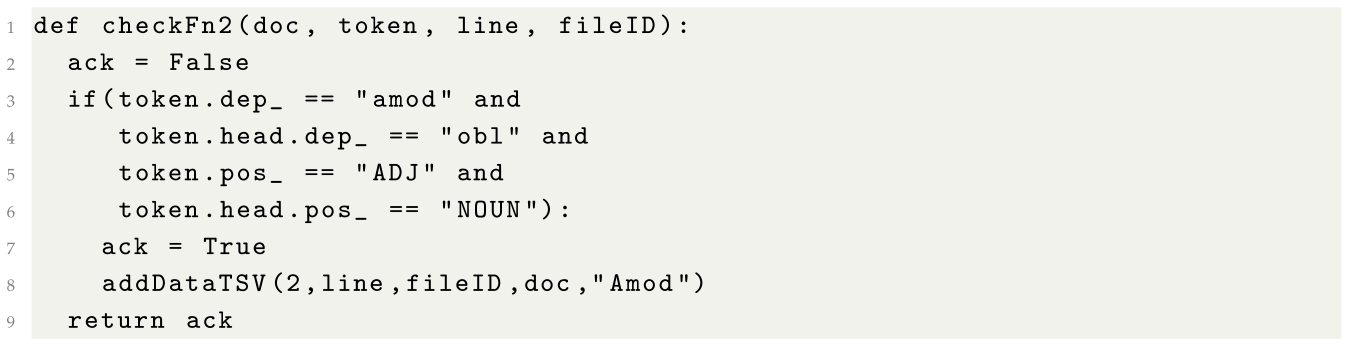

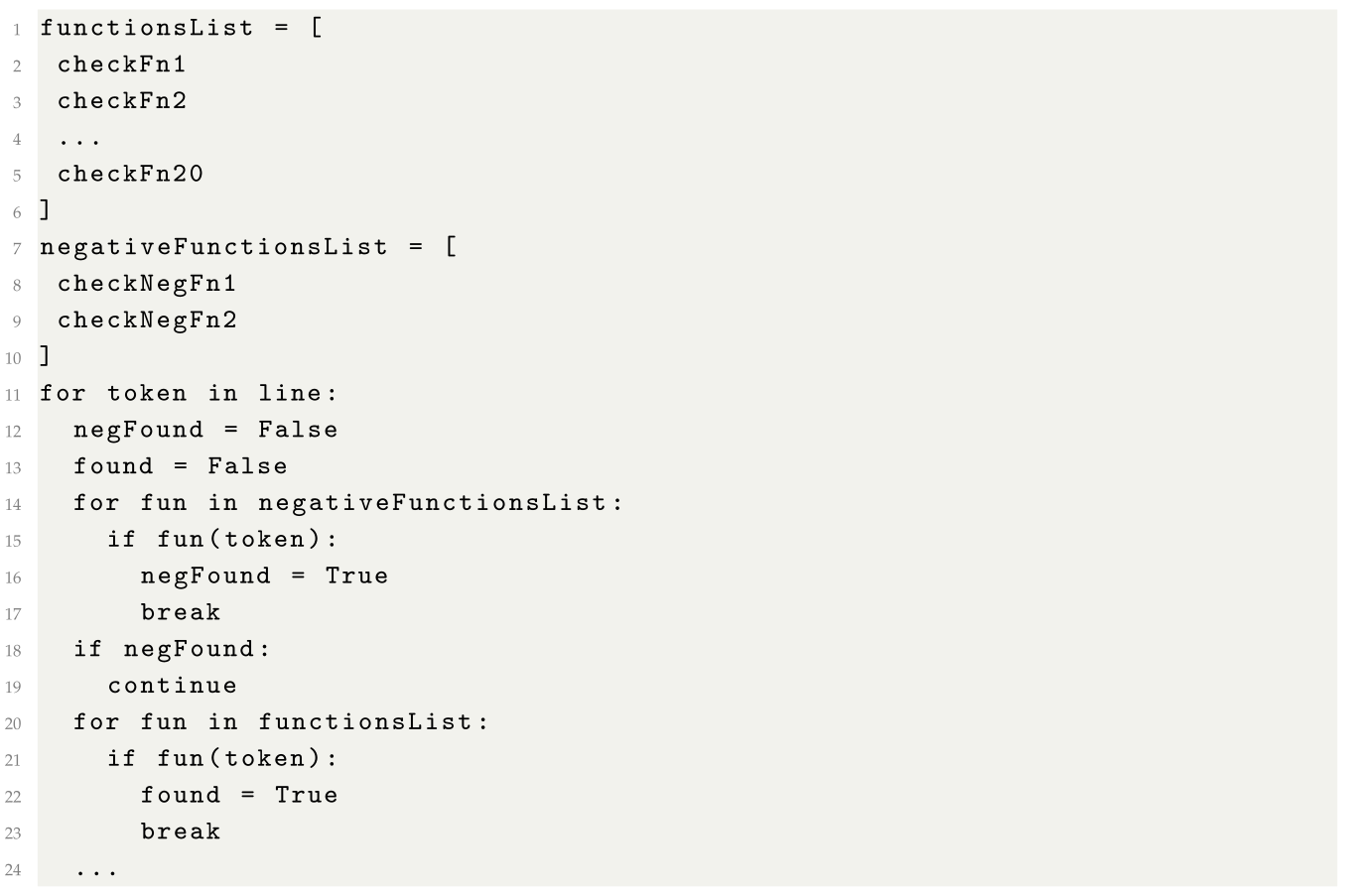

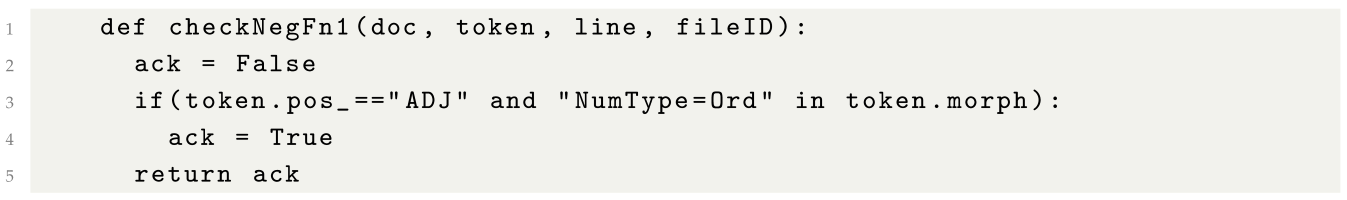

12]. The first is the automated identification of candidates based on predetermined grammatical or syntactic criteria. The second step is to filter these candidates to detect phraseologically significant combinations, such as collocations, using measures like frequency and statistical association. This study focuses on identifying potential collocations in Italian corpora, a crucial step in creating a learner-oriented dictionary of collocations. To do this, several syntactic rules have been defined, which, starting from the logical-grammatical analysis obtained from pre-trained models on Italian, such as the libraries

spaCy [

13] and UDpipe [

14], make it possible to identify word combinations that comply with the defined rules and classify them by type.

We posit that the success of subsequent steps in creating learner-centric collocation dictionaries heavily relies on the accuracy of candidate identification. Enhanced precision in identifying potential collocations leads to more reliable frequency data, which improves the association measures used to discard irrelevant combinations. Consequently, the overall process becomes more accurate.

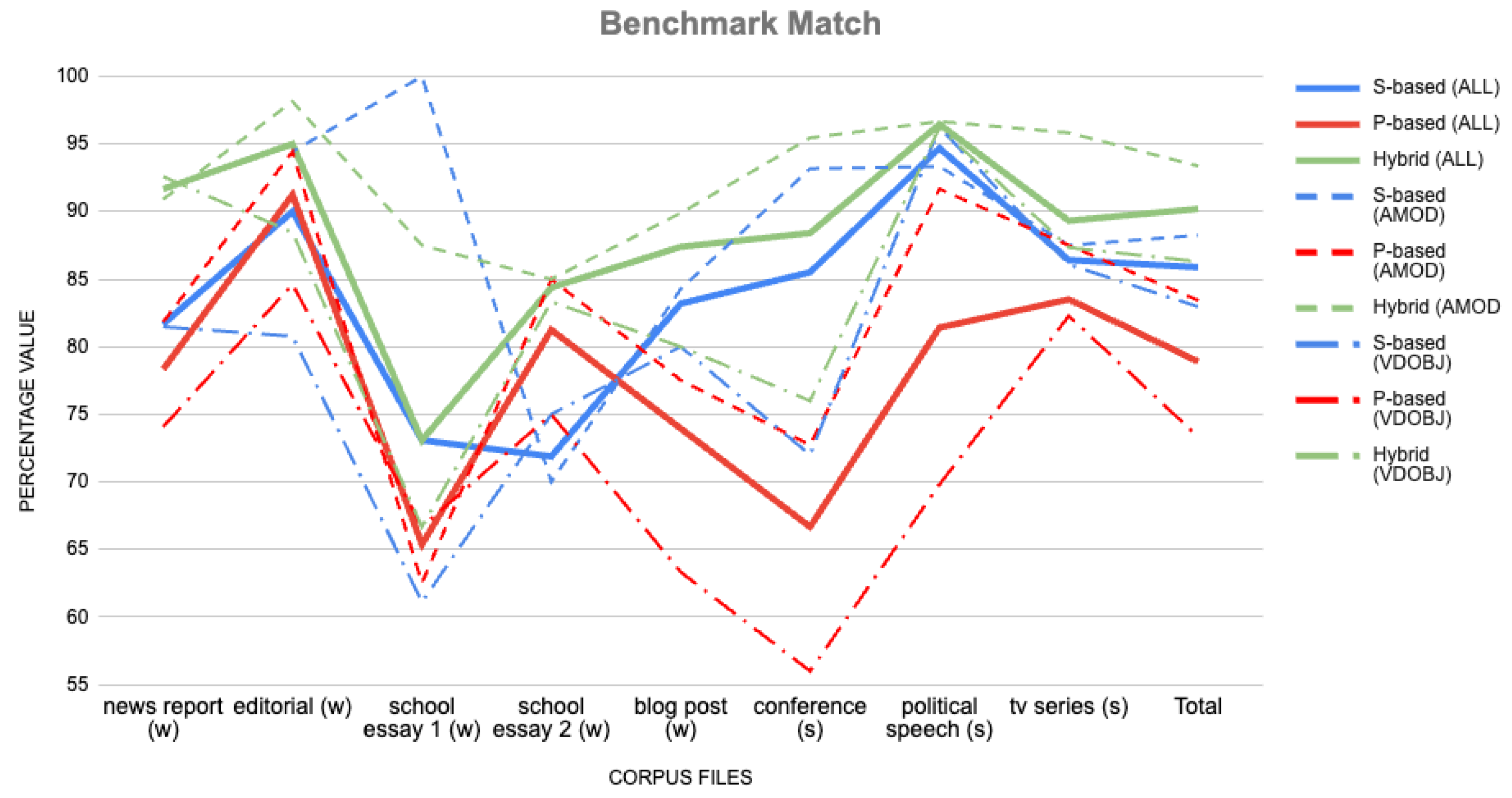

This research presents an experiment to assess a Hybrid approach for detecting collocation candidates. We compare the two predominant methods and their combination, evaluating their effectiveness in identifying collocations in Italian corpora. The first one is the Part-Of-Speech-based (P-based) method, while the second is the syntactic dependency-based (S-based) method [

15]. We have developed an integrated technique, blending these methods, which is termed the Hybrid approach.

Linguistic pre-processing steps, such as Part-Of-Speech (POS) tagging and dependency parsing, are utilised in collocation extraction to refine candidate identification. Although the P-based approach, rooted in robust NLP tasks such as POS tagging, effectively identifies positional patterns, it has its shortcomings. It cannot capture syntactic relationships or handle non-standard sentence structures. For instance, it might miss the verb-object relationship between ‘play’ and ‘role’ in a sentence like Example 1. Similar examples are reported in [

12].

Example 1. People need to observe and understand the reality around them, the social media plays, as numerous studies have shown, a significant role in shaping public opinion.

Conversely, an S-based approach, which relies on parsed data, is better equipped to detect the verb-direct object relationship, making it particularly effective in identifying candidate collocations with syntactic dependencies. Unlike the P-approach, the S-approach is not constrained by the distance between words, offering greater flexibility in recognising combinations spread across a sentence. However, it suffers from parsing errors, which have been reported to account for 7.85% to 9.7% of the extracted candidate collocations [

16,

17]. Despite advancements in parsing accuracy [

18,

19], limitations persist. The S-approach provides minimal insight into how words interact and struggles to distinguish between frequent combinations and idiomatic expressions that share identical syntactic structures [

15].

Our Hybrid method has been developed to identify collocation candidates from corpora, with a focus on Italian rather than English. This integrated approach will likely outperform existing methods in candidate detection. Additionally, we aim to explore scenarios where the Hybrid approach proves superior and identify potential areas for further refinement.

The article is composed as follows:

Section 2 analyses the current literature and provides the background needed to understand the contents of the manuscript,

Section 3 describes how the texts were analysed and how the preliminary dataset of collocations was constructed,

Section 4 describes the statistics that were calculated for each collocation and explains how the dictionary was made,

Section 6 gives the final considerations regarding the work done and describes possible future developments.

2. Related Work

This section provides a brief review of key methods and NLP techniques employed in detecting or uncovering collocation candidates from corpora [

20], while setting aside the measures used to validate phraseological significance, a subsequent step in assembling entries for lexicographic applications.

Early work in NLP focused on identifying collocation candidates, primarily through frequent word sequences, utilising n-gram models to extract these patterns from corpora [

21,

22]. N-gram models are statistical language models that predict the next word in a sequence based on the previous n-1 words. However, these methods often struggled with the complexity of natural language, particularly in capturing syntactic relationships and semantic nuances. This search, referred to as “looking for needles in a haystack” [

22], has increasingly leveraged linguistically pre-processed data, including lemmatised and POS-tagged corpora. This shift has been especially beneficial for languages with rich morphological systems and less rigid word orders [

23].

The P-approach, which emerged early due to the widespread availability of POS-tagged corpora, became foundational. Many extraction systems based on this approach rely on predefined combinations of POS tags (e.g., verb-noun, adjective-noun). Early studies demonstrated significant improvements in detection accuracy when POS filtering was applied [

24,

25,

26,

27]. These advances primarily benefited fixed and adjacent word pairs, where fundamental linguistic analysis suffices to capture elementary grammatical patterns.

In recent years, researchers have advocated for incorporating more refined linguistic analyses to enhance the detection of candidate collocations. Seretan’s work highlighted the potential of syntactic dependencies, emphasising their capacity to identify non-contiguous and syntactically flexible collocations based on word relationships, thereby improving the overall accuracy of results [

12]. Despite these advances, systems leveraging the S-approach for multi-word expression (MWE) detection have encountered significant challenges due to high parsing error rates. Parsing, although beneficial for initial syntactic analysis [

20], has been documented as a persistent source of errors that impact detection quality. Some studies have quantified this problem by reporting an error rate that in some cases exceeds 7% [

28], while identifying relative constructions as the cause of nearly half the missed candidate collocations [

29].

These limitations underline that while S-based methods show promise, they remain hampered by parsing inaccuracies. To address these issues, researchers have increasingly advocated for Hybrid approaches. These approaches aim to mitigate their shortcomings by integrating the strengths of P- and S-based methods. This perspective is summarised by the observation that

“the two methods seem to be highly complementary rather than competing with one another" [

15].

Recent studies have attempted to operationalise this integration, developing a system combining POS-tagging with dependency parsing to identify single-token and multi-token verbal MWEs [

30]. Their systems achieved the best results with verb-particle constructions, accurately identifying approximately 60% of such cases, although success rates for other MWE types remained around 40%. Similarly, Shi and Lee [

31] introduced a joint approach that combines scores from POS tagging and dependency parsing to extract headless MWEs. Their findings indicated that tagging surpasses parsing in accuracy for flat-structure MWEs. However, the joint method delivered higher overall precision, primarily due to the combined contributions of the two techniques [

32]. Artificial intelligence can also help to analyse language effectively with the help of software such as

spacy [

13] or UDPipe [

33] libraries, which can also take advantage of modern graphics accelerators (GPUs) and their computational power [

34]. These approaches could be further improved by the possibility of enriching the information in the input datasets, also through the production of synthetic data designed ad hoc or possibly generated by modern Large Language Models (LLMs). These techniques have yielded significant results in various fields, ranging from telerehabilitation to automatic object recognition within images [

35,

36].

4. The Dictionary

The combinations obtained through the Hybrid approach were subsequently processed to be integrated within a MySQL database. Using a database enables the effective manipulation of data and the adoption of additional technologies [

44], such as those necessary to display this content to users. Additional metrics have also been calculated that can be used to filter the dictionary according to predetermined thresholds. The threshold values are based on established practices in the field of collocation extraction as documented in the literature [

45,

46,

47].

The metrics that are summarised below (

,

,

,

,

D,

,

,

U) were calculated for each combination of the dictionary. The formulas used to calculate

,

,

and

D are described in [

45,

48]. The formula of

is described in [

49]. The formula of

U is described in [

50]. Finally, the formulas of

and

are described in [

51].

The formulas that are now described require the frequency associated with the combinations to be known and all the used formulas are summarised in

Table 10.

The frequency of a combination was calculated, taking into account the context in which it was detected. This approach was adopted for the combination, understood as a combination of lemmas, as well as for the individual lemmas that comprise it. A combination of two lemmas will have a frequency calculated for both the first and the second lemma, and the value of the frequency of the two lemmas may differ.

The first time a combination is detected, its frequency will be 0. Subsequently, each time a previously analysed combination is re-encountered, the context of the sentence is analysed. If the sentences have the same context, the frequency is not increased; however, if the contexts of the sentences are different, the frequency of the combination increases by 1. This analysis produces a triple of values for each combination: the total frequency of the combination, the frequency of the first lemma, and the frequency of the second lemma. The analysis of whether a combination belongs to a context already encountered is based on the similarity between the sentences using the Bag-of-Words technique [

52]. For each sentence, a list without repetitions of the words that compose the phrase is created and stored in memory. Each time a new combination is encountered, the sentence’s word list is calculated and compared with the lists of previously analysed sentences in which the analysed combination was present. The similarity percentage between two sentences is calculated by dividing the number of common words, obtained from the intersection of the two lists, by the number of words in the shorter list, as described in [

53,

54].

If the similarity percentage exceeds a predetermined threshold, the combination is considered to belong to the same context. A similarity threshold of 0.5 was selected based on empirical tuning. Qualitative assessment by domain experts indicated that stricter thresholds led to data sparsity, negatively affecting the stability of association measures, while 0.5 effectively balanced context retention and noise filtering.

Figure 2 shows the graphs calculated by analysing the database of combinations extracted from the Corpus.

Mutual Information (

) is used to identify the strength of association between two words. Given a co-occurrence

,

A and

B constituents of the combination,

N number of words contained in the Corpus from which it was extracted and

f absolute frequency value in that Corpus, the expression of

is shown in Equation (2). The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2a.

The majority of the analysed word pairs have a positive score. The graph illustrates this by the histogram’s asymmetrical distribution, characterised by a pronounced right tail (right-skewed). The peak of the distribution (the mode) is located at an value of approximately 5. This is a highly favourable result, as it indicates that the extraction method has successfully identified word combinations that co-occur much more frequently than they would if selected by a random algorithm based on pure chance. The centring of the distribution in the positive range indicates that the dataset is rich in candidates with a significant associative link. Generally, an is considered a good threshold for identifying significant collocations, though higher values are preferred for learner dictionaries.

The Cubic Association Ratio (

) aims to amplify terms involving less frequent associations to determine whether rare associations may be significant. The formula is shown in Equation (3). The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2b.

The distribution of values maintains the general shape observed for . The most notable difference is the extension of the value scale on the x-axis, which now reaches and exceeds 40. Cubing the joint frequency acts as a magnifying glass, “stretching” the distribution to the right. The pairs that already exhibited a strong connection with the standard show an exponential increase in their score, distancing themselves from weaker associations. The primary purpose of this metric is to identify word pairs that, although rare, constitute very strong and fundamental collocations to study for language acquisition. For lexicographic purposes, a threshold of is suggested to prioritize frequent and strongly associated pairs over rare combinations.

, a statistical metric, was calculated to indicate the typicality of the combination using the formula shown in Equation (4).

The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2c.

focuses on the degree of internal cohesion of a word combination. If the calculated value is high, the presence of one word in the pair strongly indicates the other’s presence within the sentence or discourse. Combinations with values above 10 are considered highly cohesive, and students can greatly benefit from studying them to learn the Italian language. The combination with the highest detected value is capro espiatorio (scapegoat) with a value of 13.742, followed by anidride carbonica (carbon dioxide) with a value of 13.712, and procreazione assistita (assisted reproduction) with a value of 13.515. For practical lexicographic filtering, we suggest prioritizing candidates with a , as this threshold typically indicates high cohesion and idiomaticity.

(

) was calculated to determine the likelihood of a combination, i.e., how likely it is that two words recur together.

compares a combination’s observed frequency with the expected frequency if the two words were independent. The formula used is shown in Equation (5). The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2d. A critical feature of this graph is that the y-axis (Occurrences) is plotted on a logarithmic scale. A logarithmic y-axis is necessary to visualise the data, indicating a vast difference in the number of occurrences across the range of

values. The distribution is skewed to the right, with most candidate pairs having low

scores.

Where is the observed frequency of the combination, is the frequency of word B from which the value of the frequency of combination is subtracted, is the observed frequency of word A from which the value of the frequency of combination is subtracted, is the total words minus the observed frequencies of the combinations. , , , are the expected frequencies.

’s primary function is to measure confidence or statistical significance. values can be used to filter the data in the dataset. A combination with a very low value, close to 0, is highly likely to be of little use and could be classified as noise. Discarding these combinations can enhance the quality of the dictionary by focusing on those that are more likely to be beneficial for students and removing those that are likely to be false positives or noise. The filter can be applied by setting a minimum threshold for the value, which semantically describes the desired confidence level. We suggest filtering for .

We also calculated Juilland’s dispersion index

D, which refers to how widely a word or combination is distributed in a Corpus. Let us imagine the Corpus structured in several sub-corpora: a word/combination is dispersed within the Corpus if it occurs with equal or similar frequency in all parts of the Corpus; conversely, a word or combination is poorly dispersed if it only happens in one or a few parts of the Corpus. Dispersion applies equally to single words and word combinations. A word combination can be seen as a single word.

D is calculated as shown in Equation (6), where

V is the coefficient of variation and

C is the number of parts of the Corpus, which in our case is 10. The graph of the distribution of

D is shown in

Figure 2e.

Unlike the previous metrics, the distribution of the D index is not unimodal. It presents a complex, bimodal (or even multimodal) shape, which provides significant insights into the nature of the collocations found in the Corpus. The most prominent feature is the presence of at least two distinct peaks. This suggests that the extracted collocations fall into different categories based on usage patterns across the Corpus. While fewer in number, the collocations with high dispersion scores () are of the highest value for this project. These are word combinations whose meaning is consistent regardless of the topic of discussion. Examples of combinations with a D value greater than 0.7 are prendere decisione (make a decision), avere potere (have power), mostrare interesse (show interest), and fare parte (be part of). We suggest filtering for .

Gries’ Deviation of Proportions (

) coefficient was calculated to indicate how widely a word combination is distributed in a Corpus. The formula used is shown in Equation (7), where

is the proportion of occurrences of the element in the i-th part of the Corpus and

C is the total number of parts of the Corpus. The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2f on a logarithmic scale.

A score near 1 indicates maximum clustering, while a score near 0 indicates maximum dispersion. These are highly domain-specific collocations, found in only one or a few parts of the Corpus. Several distinct and sharp peaks (e.g., around 0.75, 0.85, 0.95) suggest specific, recurring clustering patterns. This could be related to the size and content of the 10 sub-corpora, indicating that large amounts of topic-specific vocabulary dominate certain sections of the source material. When filtering the combinations, it is recommended to select those with values below a threshold (e.g., 0.5). The collocations with the lowest values are the most fundamental for a learner. For example, among those with the smallest values are valere pena (be worth), spiegare meglio (explain better), and avere senso (make sense).

The normalised Deviation of Proportions coefficient (

) was calculated to indicate how widely a word combination is distributed in a Corpus. The formula used is shown in Equation (8). The graph of the distribution of

is shown in

Figure 2g.

is a scaled version of , making it easier to interpret and compare across different datasets. The purpose of this normalisation is to adjust the metric’s range so that it measures the same concept as the un-normalised . The data shown in the figure presents results similar to those of . Similar to DP, a threshold of is recommended.

Finally, the Usage Coefficient index (

U) [

50] was calculated according to the formula shown in Equation (9). The graph of the distribution of

U is shown in

Figure 2h on a logarithmic scale.

U is a composite metric that combines the dispersion index D that describes how widely and evenly a collocation is used across the different parts of the Corpus, with the total frequency of the collocation , which indicates how often the collocation appears in the Corpus. A high U score can only be achieved by a frequent and widely distributed collocation in the Corpus. This distribution shape proves that the overwhelming majority of candidate collocations have a very low Usage Coefficient. This is an expected result because the previous analysis of dispersion metrics D showed that many items were poorly dispersed, which would inherently lead to a low U score. The most important information is in the sparse tail to the right of the distribution. The collocations that achieve a high U score are the best candidates for the dictionary, as they are frequently used and appear in various contexts. To ensure candidates are both frequent and widely used, we recommend setting a minimum threshold of .

The graphs illustrate the relative distribution of calculated values. The X-axis represents the values of the variable, while the Y-axis represents the frequency for each corresponding X-axis value. The graphs provide a visual representation of the distribution of the calculated metrics, offering insights into the characteristics of the dictionary entries.

The analysed metrics, for which values have been calculated, are fundamental for identifying the collocations representing high-yield learning for the student.

These metrics are utilized during the filtering phase and are combined to select statistically relevant collocations. The filtering process was implemented by establishing thresholds derived from a rigorous analysis of prior studies on the English language, which guided the application of these filters to Italian collocations.

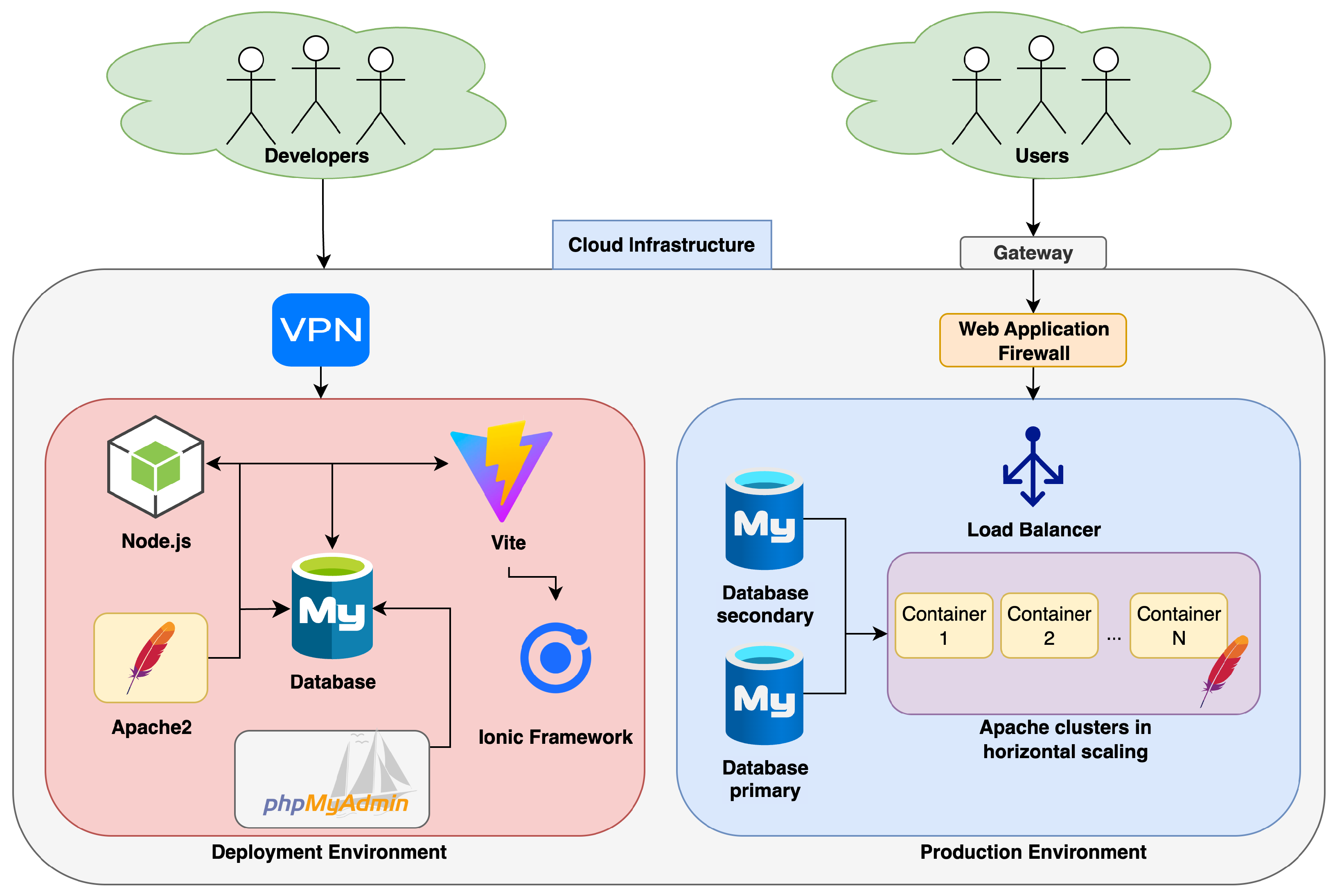

5. The System Architecture

The dictionary’s system architecture is built on a cloud infrastructure, adopting a pay-per-use model. This approach eliminates the need for physical servers by utilising the provider’s virtual servers, with costs determined by actual service consumption. It does not require physical hardware maintenance, resulting in consequent advantages in terms of service reliability for our use case. The infrastructure is structured into two distinct subnets: the first one is for development and testing, while the second one is dedicated to the production environment that serves end-users.

Figure 3 shows the overall architecture of the system.

The dictionary development environment is now analysed. The purpose of this area of the cloud infrastructure is to enable developers to manage content used by users without slowing down or causing issues for the public during testing and implementation of new code functions. Access to this portion of the infrastructure is via a VPN connection, ensuring that only developers can connect to the machines and services in this area. Various Docker containers have been configured within it. The decision to use Docker was made due to software maintenance, system package updates, and the intrinsic security of the containers themselves, which, for example, are only able to communicate with the outside world if the developers decide to do so and only to the ports and IP addresses agreed during the development phase. A first container contains a Node.js server that establishes communication with a Vite service, within which the Ionic framework has been set up. This setup is necessary to create the dictionary using the Hybrid App technique. The Vite server is capable of serving HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code. It automatically updates the content displayed on developers’ test devices as soon as the source code is changed, in a fully automated manner.

Development takes place using the Ionic framework, which allows the creation of a web page that can then be exported for an Android or iOS project, drastically reducing the development and programming time for mobile operating systems, as two separate projects are automatically generated from a single code base, which can be immediately compiled and sent to the official stores (Google Play Store and App Store), ensuring that the graphical interface also maintains the styles of the respective operating systems to which they belong. This framework and the Vite server are supported by Node.js, which enables JavaScript code to be executed on the server side and allows packages and libraries to be managed via npm.

A second container contains a MySQL server that hosts the dictionary database. This database is used only for the development and testing phase. However, it can be synchronised with the environment actually used by users. The database can also be managed via a graphical interface using a second container containing phpMyAdmin. Queries to the dictionary are handled using PHP hosted within an Apache2 container.

The production environment, on the other hand, is used solely by end users. The access point is the public Gateway, which corresponds to the dictionary’s domain name.

Immediately after contacting the Gateway, requests pass through a WAF, i.e., a Web Application Firewall designed to filter out cyberattacks, such as SQL injection, Cross-site scripting (XSS), and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

If the request is deemed legitimate, it is redirected to the load balancer of the Apache2 node cluster. The load balancer sorts user requests using the Round-Robin algorithm, evenly distributing the number of requests across the various nodes. Apache2 containers are used to manage queries to the database. Each container exposes APIs written in PHP that query the database and return the results to the client.

The container cluster was designed to ensure that if one of these containers malfunctions, the others can still execute requests. They also enable the distribution of computational load, making the system more responsive. Metrics have also been implemented to analyse the number of requests made by users in real time. Based on the calculated value, nodes are added or removed to ensure the best possible experience. This technique is also called auto-scaling and is one of the key features of cloud computing.

For example, suppose there is a spike in users using the dictionary. In that case, the system can react automatically and create new Apache2 containers to handle the additional workload, releasing these resources as soon as the number of requests decreases. This ensures that the system is always responsive and that there are no slowdowns or service interruptions, paying only for the resources actually used.

The database is also built using High Availability techniques. There are two databases: a primary database, which can both read and write data, and a secondary database, which has read-only permissions. The secondary database is used to distribute the workload and improve system performance. This ensures that even if the primary database fails, the system can continue to function using the secondary database.

The infrastructure is based on a production database cluster accessed by end-users, and a second database dedicated to application development and maintenance. These databases can be synchronized to propagate changes from the development environment to the production one. The primary advantage of this approach is the ability to test and implement updates and modifications within an isolated and secure testing environment. This prevents any potential disruption to the users accessing the service. Once modifications have been tested and deemed reliable, they can be made available to the public.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This work aims to create a dictionary for international students learning Italian. Unlike conventional dictionaries, the one we aim to create will feature word combinations, also called collocations. The primary characteristic of these collocations is that their semantic meaning differs from the syntactic meaning derived from analysing the individual words composing them. This characteristic represents one of the significant obstacles for language learners, as a proper grasp of collocations requires a deep understanding of the ongoing discourse and the idiomatic expressions of the target language. Consequently, having suitable tools to enhance study and improve the quality of learning is crucial. In this work, we analysed a Corpus, a collection of texts, comprising 41.7 million words, using three distinct methodologies.

The project’s initial phase involved testing our approach on a small sample of the Corpus to validate our working methodology. The results indicate that the Hybrid method outperforms the other two in metrics such as benchmark match and recall, supporting our initial assumptions. Nevertheless, the P-based approach outperforms in precision, accuracy, and F1 score, highlighting areas where the Hybrid method requires further refinement. Following encouraging results, we proceeded with the study by implementing and refining grammatical analysis rules. These rules, based on the output from the spaCy NLP library, enabled the creation of Python scripts for automated Corpus analysis, producing a dataset of collocations. Enhancing the model’s precision could involve developing additional Python rules, such as negative rules, to systematically eliminate false positives. While post-tagging provides a degree of robustness that compensates for the relative imprecision of syntactic parsing, the detection rules used after parsing require additional refinement to mitigate errors stemming from false positives. The findings underscore the value of a Hybrid approach, demonstrating that it leads to improved performance and higher-quality results.

At the end of the Corpus analysis and combination extraction phase, we obtained a total of 2,097,595 combinations, of which 40.05% were identified using the S-based method, 17.60% with the P-based method and 42.35% with the Hybrid method. After developing the dataset, we conducted a detailed analysis to gather statistical metrics, as outlined in

Section 4. This analysis aimed to filter collocations in the dictionary, eliminate potential false positives. Additionally, we sought to identify the collocations that are most frequently used in the Italian language. The labeling of collocations according to CEFR levels (A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2) is currently in progress and will be the subject of future work. In the future, we will utilise the adopted metrics to enhance the quality of the dictionary, which will be accessed through a web interface. This will allow students to select their current proficiency level and the target level they wish to achieve, based on frameworks such as the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. The collocations can also be ordered by combining frequency with the measure of dispersion through the different textual genres represented in the Corpus. Thanks to these features, our goal is to enable students and teachers to use this dictionary with the ultimate aim of improving the quality of Italian language study and learning.