Hybrid LLM-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Framework for 5G/6G Networks Using Real-World Logs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Hybrid Fault Diagnosis Framework: We design the multi-stage Hy-LIFT pipeline that integrates an interpretable rule-based engine (IRBE) for known fault detection, a semi-supervised classifier (SSC) that learns from both labeled and unlabeled logs, and an LLM Augmentation Engine (LAE) that provides explanatory and zero-shot diagnostic capabilities. To our knowledge, this is the first framework to tightly couple rule-based reasoning, semi-supervised learning, and LLM-based analysis for network fault management.

- Interpretability and Explainability: The IRBE module encodes expert domain knowledge as human-readable rules, ensuring that detections of known faults are immediately explainable by design (each triggered rule corresponds to a condition in the network). The LAE module leverages a large language model to generate natural language explanations for both known and novel faults, translating low-level log patterns into high-level insights. We demonstrate that the combined system produces rich explanations that are understandable to engineers, addressing the trust gap in ML-driven O&M [1].

- Robust Semi-Supervised Learning: We develop a semi-supervised fault classifier that uses pseudo-labeling to make use of real-world log data where labels are scarce. The SSC is initially seeded with high-precision labels from IRBE and iteratively improves its coverage by labeling new samples with a confidence-based mechanism [5]. This approach exploits large unlabeled log corpora to enhance the detection of subtle or latent fault patterns that rules alone might miss. We show that our SSC achieves higher recall and F1 than a purely supervised classifier trained on the limited available labels, consistent with other log analysis works that saw F1 improvements over 180% via probabilistic label estimation [6].

- Evaluation on Real Network Logs: We evaluate Hy-LIFT on real-world 5G/6G network log datasets (described in Section 4) containing a variety of fault types (e.g., hardware failures, congestion events, handover failures, backhaul outages). The evaluation includes overall and per-class performance metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1) under different conditions, comparison against baseline methods (pure rule-based, pure ML), and analysis of robustness to noise and class imbalance. We also include case studies of novel fault incidents to assess the LLM’s zero-shot diagnostic capability. All results are presented with a focus on reproducibility and statistical significance.

- Open-Source Implementation: To encourage transparency and further research, we provide an outline of our implementation, with all critical components reproducible. (Author’s note: repository and data links omitted for review.) The framework is implemented using open-source libraries and can be integrated into existing network management systems. We adhere to principles of scientific rigor, carefully validating each component, and discuss how the approach can be deployed in practice (including considerations of runtime performance and maintaining the system as networks evolve).

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional and Rule-Based Network Fault Diagnosis

2.2. Semi-Supervised and Data-Driven Log Anomaly Detection

2.3. LLMs and AI for Network Operations

3. Methods

3.1. Overview of the Hy-LIFT Pipeline

- IRBE (Stage 1, Rule-Based Detection): When a new batch of network logs arrives (e.g., runtime logs, performance counters, alarm messages from base stations, etc.), the IRBE scans them for any patterns or signatures that match known fault conditions. These rules are made based on what people know about the domain. For instance, if eNodeB does not send any heartbeats for more than 5 min, a rule might find a “Cell Outage” fault, or a “S1 Link Failure”, if transport layer errors exceed a threshold. The IRBE immediately flags logs that satisfy rule conditions as fault occurrences of the corresponding type. Because the rules are explicit, their decisions are inherently interpretable: each triggered rule comes with a predefined explanation (e.g., “Rule R1 triggered: No heartbeat from site 123 for 300 s, indicating possible outage”). IRBE outputs a set of high-precision labeled logs (with fault labels and rationale) and may ignore logs that do not match any rule (these remain unlabeled for now).

- SSC (Stage 2, Semi-Supervised Learning): The semi-supervised classifier takes two inputs: (a) the labeled samples from IRBE (which act as a seed training set), and (b) the remaining unlabeled log data. The goal of SSC is to learn a fault classification model that can generalize beyond the exact conditions encoded in the rules. We implement SSC as a machine learning model (for example, a deep neural network or an ensemble tree classifier) that can ingest log-derived features and output fault class predictions. Training proceeds in a self-training or pseudo-labeling fashion [5]: first, train an initial model on the IRBE-labeled data; then use this model to predict labels for unlabeled logs; accept the most confident predictions as pseudo-labels and add them to the training set; retrain the model and iterate. Through this process, SSC leverages the abundant unlabeled logs to improve its performance, effectively propagating the influence of IRBE’s knowledge to cover more data. Importantly, SSC is not bound strictly by the IRBE’s specific rules; it might learn to recognize the same fault in scenarios where the rule’s conditions only partially manifest. Formally, the semi-supervised learning process in Hy-LIFT can be expressed as follows.

- Supervised loss: We use a cross-entropy loss on labeled data. For example, for a single labeled instance , . The overall supervised loss is:

- Unsupervised consistency loss: For each unlabeled log , we obtain the model’s current prediction as the pseudo-label (the class with the highest predicted probability), and let be the confidence (maximum probability). We introduce a confidence threshold to select only confident predictions. Define an indicator , which is 1 if the model is confident on and otherwise. We also define as a stochastically augmented version of (e.g., a noised or paraphrased log message) to enforce prediction consistency under input perturbation. The unsupervised loss can then be written as:

- Regularization: denotes a regularization term on the model parameters (e.g., weight decay or other regularizer) to prevent overfitting. We denote by the penalty function (such as and its weight.

- LAE (Stage 3, LLM Augmentation and Explanation): The final stage addresses two functions: generating human-understandable explanations and handling novel faults. The LAE uses a large language model (such as GPT-based models) to process the information from the previous stages in conjunction with the raw log snippet and produce a textual explanation of the fault diagnosis. We design prompt templates for the LLM that include: a brief description of the context (e.g., “You are an expert network assistant”), the relevant log excerpt, and the outputs from IRBE/SSC. For example, if SSC predicts a fault “backhaul link failure” with high confidence, the prompt to the LLM might be “Log excerpt: [<log lines>]. The system has identified a Backhaul Link Failure. Explain the evidence and potential cause.” The LLM then generates an explanation, such as “The log shows repeated ‘NodeB X2 interface down’ and ‘Transport disconnect’ errors around 12:00 UTC. These indicate that the backhaul link to the base station was lost, causing the cell to go offline. This is why the system classified it as a Backhaul Link Failure. The likely cause could be a fiber cut or routing issue in the transport network.” This provides operators with a concise summary, combining log evidence with the likely root cause.

3.2. Interpretable Rule-Based Engine (IRBE)

- Cell Outage Rule: If a site reports a “Heartbeat Loss” or “Ping Timeout” event continuously for > T minutes, and no other activity from that cell is logged, classify it as a cell outage fault (rationale: the base station likely went offline).

- Handover Failure Rule: If within a 5 min window, the number of X2/S1 handover failure messages exceeds N and the success rate falls below Y%, classify as a handover failure fault (rationale: abnormal spike in handover failures indicates a possible mobility issue or interference).

- Backhaul Fault Rule: If log messages show “S1 link down” or transport network errors (e.g., socket timeouts to core network) and recovery does not occur within Z seconds, tag a backhaul link failure (rationale: loss of backhaul connectivity).

- Overload (Congestion) Rule: If a cell’s CPU or buffer usage exceeds a threshold and messages like “RRC reject due to load” or “Packet drop due to congestion” appear, classify it as a network overload fault (rationale: the cell or network is congested beyond capacity).

- Hardware Failure Rule: If there are hardware-related alarms (e.g., “PA temperature critical” or “Power amplifier failure”) followed by a sector shutdown, classify it as hardware failure. (rationale: physical component fault.)

3.3. Semi-Supervised Classifier (SSC)

3.4. LLM Augmentation Engine (LAE)

- System/Context Prompt: This establishes the role of the LLM and provides any needed background. For example, “You are a network fault analysis assistant. You have knowledge of telecom systems and common failure causes. You will be given log data and analysis results, and you will produce an explanation for the fault.” We also load a brief list of known fault types and their descriptions into the prompt (essentially giving the LLM a mini knowledge base to draw correct terms from). This helps align terminology, e.g., ensure it uses “backhaul failure” if that is the class name, rather than a synonymous phrase.

- Input-specific Prompt: This includes the actual data: relevant log lines (we may truncate or summarize logs if very long), and structured info such as the fault label from SSC/IRBE. For instance:

- -

- Fault type: Backhaul Link Failure

- -

- Evidence: multiple ‘S1 link lost’ errors, NodeB reconnect attempts failing.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Setup and Datasets

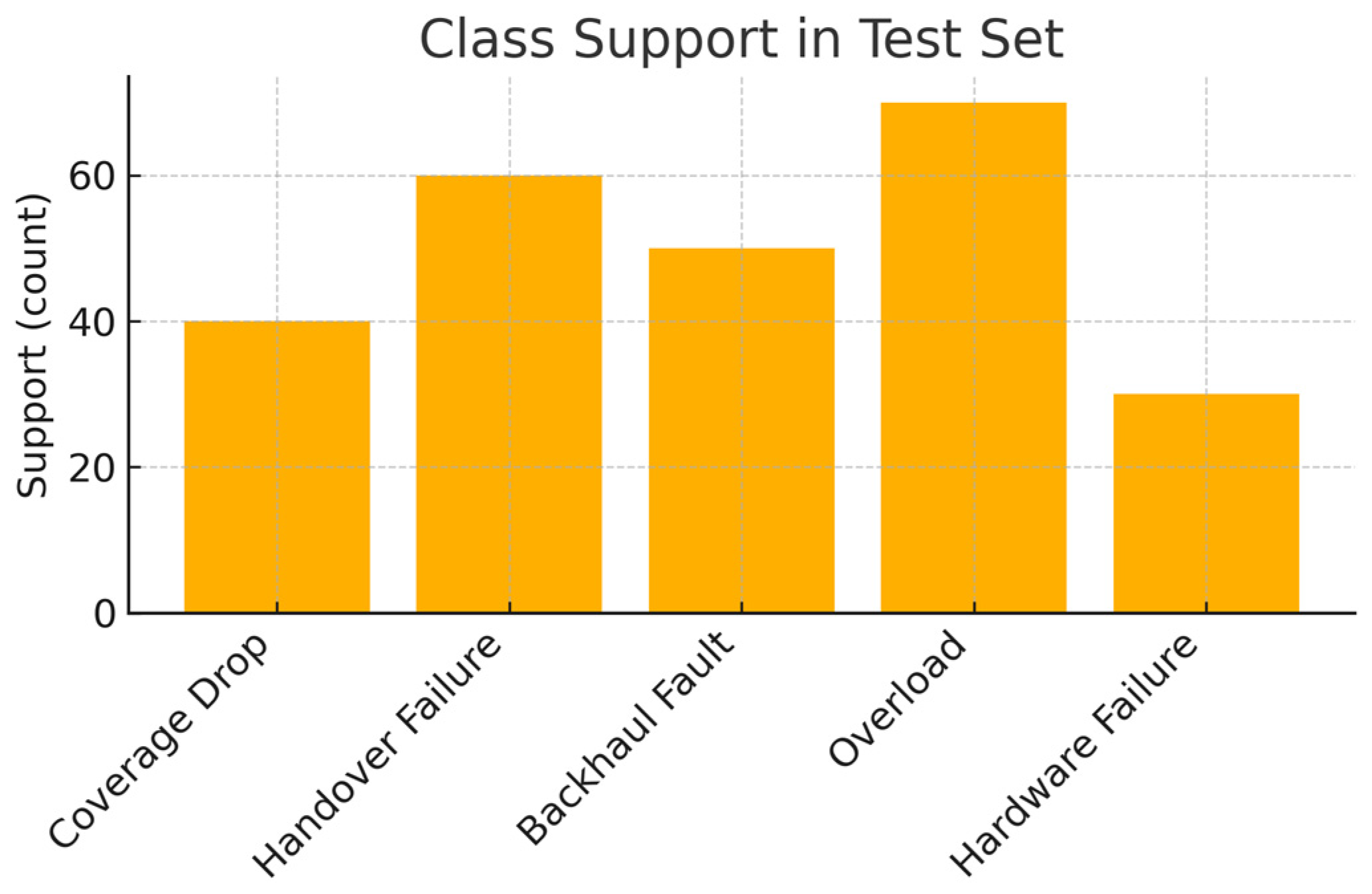

- Dataset-A (5G Operator Logs): This dataset consists of annotated logs from a live 5G network operated by a national carrier. It contains logs collected over 2 months from ~100 base stations (gNodeBs). Domain experts had labeled five known fault types in the data: coverage drop, handover failure, backhaul fault, overload, and hardware failure. These correspond to the kinds of faults described in Section 3.2. There is a total of 8000 log sequences (each sequence aggregates logs around a suspected event, e.g., a 10 min window for an outage event), of which 1200 were labeled as one of the fault types, and the rest had no major fault (normal operation or minor issues). The fault class distribution is imbalanced: “overload” and “handover failure” are the most common (approx. 400 each), while “hardware failure” and “backhaul fault” are rarer (<150 each), reflecting that some faults (e.g., congestion) happen more frequently than others (hardware breakdowns). Additionally, there were a few unlabeled anomalous sequences that experts noted did not fit any of the five categories—we treat those as potential novel faults in evaluation.

- Dataset-B (6G Lab Testbed Logs): To test generality, we also created a semi-synthetic dataset representative of future 6G networks using a lab testbed. This dataset included three known fault types (subset of above, e.g., overload, backhaul fault, software crash) injected in a controlled manner, plus normal logs. We primarily use Dataset-B to evaluate robustness to noise and minor concept drift (since the environment differs). For brevity, we focus on Dataset-A results in this paper and note that trends on Dataset-B were similar.

- Datasets and Representativeness: We assembled two complementary datasets to cover a wide range of fault scenarios. Dataset-A comprises real 5G network logs provided by a national telecom operator, spanning five known fault types labeled by experts, ensuring the data reflects genuine operational issues. Dataset-B is a semi-synthetic 6G testbed log set where known fault patterns (e.g., simulated backhaul failures, overload conditions, and protocol-level anomalies) were intentionally injected in a controlled environment. Combining real-world operator data with carefully simulated scenarios allowed us to obtain a robust and representative dataset that covers both frequent and rare fault conditions. In practice, acquiring representative datasets often requires augmenting limited field logs with domain-informed simulations; our approach aligns with established practices such as data augmentation and network-digital-twin-based log synthesis. This clarification has been added to guide practitioners in assembling suitable datasets for similar machine-learning–based fault-diagnosis frameworks.

- IRBE-Only: The rule-based engine alone, which outputs detections when rules fire and no output otherwise. Any faults not covered by the rules are missed. This represents a traditional expert system baseline.

- Supervised ML: A fully supervised classifier trained only on the available labeled data (in this case, the expert-labeled 1200 instances in Dataset-A). We used a Random Forest and an RNN in tests; results reported here use Random Forest as it performed slightly better with limited data. This baseline cannot leverage unlabeled logs.

- Semi-Supervised (SSC-Only): Our semi-supervised classifier’s performance without IRBE rules (except for using the same initial labeled set). This is essentially the result of applying pseudo-label training on the expert-labeled set alone. It indicates the benefit of unlabeled data without IRBE augmentation.

- Hy-LIFT (IRBE + SSC, no LLM): The combined rule + semi-supervised system’s raw classification performance, before LLM explanation. This demonstrates the predictive performance of our multi-stage approach.

- Hy-LIFT (full): The complete system, including LAE. For fairness, the LAE does not change the classification decision (it only explains it), so the classification metrics remain the same as the previous item. However, we will discuss the novel fault detections that only LAE could surface.

4.2. Fault Classification Performance

- The IRBE alone detects faults with high precision (~0.85) but very low recall (~0.60 macro). In fact, IRBE failed to detect any instances of two fault types that lacked explicit rules (coverage drops and one type of sporadic software issue in this dataset), yielding 0% recall for those classes. The rules that did trigger had near-perfect precision, confirming our design choice, but many faults went uncaught. This is reflected in IRBE’s low macro-recall and F1 [27]. It underscores that while rule-based detection is trustworthy for known conditions, it leaves substantial blind spots.

- The supervised ML baseline (trained on 1200 labeled instances) achieved ~82.5% accuracy and 0.83 F1. Its errors were mainly in minority classes where training examples were few, e.g., it often misclassified some “hardware failure” instances as “backhaul fault” or vice versa, due to limited examples to distinguish between those. This baseline also completely missed any novel faults since it can only predict the classes it was trained on. The precision vs. recall was balanced (~0.83 each), indicating it did not have a strong bias.

- The semi-supervised classifier, trained without explicit IRBE labels but using the available unlabeled logs, achieved 86% accuracy and a macro-F1 of 0.86. This highlights the value of exploiting unlabeled data, particularly for minority fault classes. For instance, the F1 score for the “hardware failure” class increased from 0.75 to 0.85 under semi-supervised training (see per-class metrics below). Although the SSC introduced a small number of additional false positives—slightly reducing precision compared with the purely supervised model—the improvement in recall more than compensated for this trade-off. This behaviour is consistent with reports from prior work, such as PLELog, where semi-supervised strategies substantially enhanced anomaly detection performance.

- Hy-LIFT (IRBE + SSC) achieved an accuracy of about 89.2% and a macro-F1 score of 0.89, which was the best overall performance among all the configurations that were tested. Its recall is about the same as the SSC-only model’s, but its precision is a little higher. This means that the high-confidence rule-based detections help get rid of some of the false positives that the ML classifier would have added. In practice, when a rule fires with confidence, its decision takes precedence over the SSC, which stops some misclassifications. The IRBE also helps by finding more correct detections when the SSC is not sure because there are not enough similar training examples. So, the resulting hybrid has a more balanced profile: it does not have the coverage problems of a purely rule-based system and is a little more accurate than the stand-alone ML model. These results back up our design idea that using rules and learning together works better than using either one on its own.

- Coverage drop faults had the lowest precision (77%) among the classes. The confusion matrix (Figure 2) shows that about 15% of actual coverage drops were misclassified as overload, and a small number as Handover issues. This is understandable: a cell coverage drop (e.g., sudden loss of RF coverage) can sometimes look like congestion (if the coverage issues cause many radio link failures like overload) or like mobility failures. Our rules did not specifically cover coverage drop (as it can be hard to detect explicitly), and the ML had to infer it from indirect clues (like many users lost connection simultaneously). Thus, Hy-LIFT sometimes labels coverage drops as overloads, giving a precision <80% for that class. However, recall for coverage drop was decent at 85%, indicating most actual instances were caught, albeit with some label noise. This was the hardest class, and indeed, domain experts themselves find distinguishing coverage vs. capacity issues tricky from logs alone.

- Handover failure and overload classes were well-handled, with F1 around 0.90–0.91. These had a lot of training data and clear patterns. IRBE had a simple rule for overload (based on explicit “queue full” log messages), and SSC learned additional patterns. Most misclassifications for these were within each other or with coverage issues, as mentioned.

- Backhaul fault and hardware failure, though minority classes, achieved the highest precision (~0.95 and 0.87, respectively) and a strong F1. Hy-LIFT caught 90% of these failures and rarely confused them with other classes. This can be attributed to their distinctive signatures: backhaul faults produce specific transport link errors (which IRBE and SSC clearly identify), and hardware failures often coincide with hardware alarm logs. The SSC particularly benefited from IRBE’s few high-quality examples of these after pseudo-labeling; it generalized well. For backhaul, only a couple of instances were missed or mislabeled as hardware faults. For hardware failure, the precision was a bit lower (87%), meaning a few false positives (some logs that were not actual hardware faults got classified as such). Those were cases where the ML was overzealous, but IRBE’s hardware rules typically prevented blatant false alarms.

- After adding synthetic noise to 10% of log lines (random character insertions or irrelevant debug messages), the performance of Hy-LIFT dropped only marginally (accuracy went from 89.2% to 87.6%). The IRBE rules were mostly unaffected (they look for specific substrings that remained intact), and the ML model, having seen many log variants, was resilient to extra lines. This suggests our feature extraction (which focused on counts of key events, presence of keywords, etc.) is fairly noise-tolerant. Minor format perturbations did not derail the analysis, a positive sign for deployment, where logs can contain extraneous info.

- In an ambiguity test, we had a few log sequences that deliberately contained overlapping fault symptoms (e.g., a cell experiencing an overload right before a backhaul link flap). Hy-LIFT tended to pick one fault as primary, often the one with more obvious indicators. In one test case, the actual situation was both overload and a backhaul glitch occurred; Hy-LIFT classified it as overload (the stronger signal in logs). It “missed” labeling the backhaul fault there. This points to a limitation: our system currently outputs a single fault label per sequence. If multiple concurrent faults happen, it will likely identify the dominant one. In future enhancements, we could allow multi-label outputs or sequential detection. Nonetheless, such cases were rare in our data. When we measured performance on these crafted ambiguous cases, Hy-LIFT recognized the primary fault correctly ~80% of the time, but secondary issues were not explicitly flagged. Operators examining the LLM explanation might catch hints of the second issue if mentioned (e.g., LLM might note “some transport errors also observed”), which indeed sometimes occurred.

- For concept drift, since our test set was not chronologically far from training (same 2-month window), we did not explicitly observe time-evolving drift. However, we did simulate a drift by changing the format of certain log messages in a portion of the data (like a firmware update that alters an error text). In that simulation, IRBE rules based on exact text failed (we would need to update rules), whereas SSC still caught many faults as it relied on broader features (e.g., error rates, not exact text). This indicates the learning component can provide some robustness to moderate log format changes, whereas IRBE is brittle to format drift. We discuss in Section 5 strategies to handle such evolution (like periodically retraining SSC and refining rules).

4.3. Qualitative Evaluation of Explanations

5. Discussion

- IRBE maintenance: Rules may need updates if log formats change. This is a known upkeep cost of rule-based systems. However, since IRBE rules are relatively straightforward string matches or simple conditions, updating them is not too onerous if the changes are known (e.g., search-and-replace the keyword). What is more challenging is if entirely new fault types emerge (like a brand-new type of failure). Then, new rules would need to be written, which requires expert identification. In the interim, the ML component or LLM might catch it as an anomaly or novel (zero-shot), as we saw, but for continuous monitoring, eventually adding a rule (or at least adding it as a known class for SSC) would be prudent. Our framework can ingest new rules on the fly, and the SSC can be periodically retrained with new labels, enabling an incremental learning setup.

- SSC retraining: The SSC model can be retrained on a schedule (e.g., weekly or when a drift is detected). It can incorporate newly accumulated data, including any new fault labels (from operator feedback or LAE suggestions). Online/sequential learning techniques could be used for faster adaptation. Additionally, anomaly detection on model inputs could flag drift if the distribution of features shifts significantly, which might trigger retraining. In our design, since IRBE is always looking for known patterns, it acts as a stable reference. If the ML starts flagging many things that IRBE would have, perhaps the rules need expansion. Conversely, if IRBE stops triggering because logs have changed superficially, one will notice a drop and can adjust the rules.

- LLM adaptation: The LLM we used (GPT-4-Class) is a static model with knowledge up to 2021. In a future scenario, if new fault terminology arises (say, 6G-specific jargon), the LLM might not be aware. However, one can fine-tune or prompt-engineer it with updated knowledge. For example, providing it with a glossary of new error codes or feeding in some examples (few-shot) of new fault explanations could keep it up to date. Another approach is using a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), where the LLM has access to a knowledge base (like documentation or a log knowledge graph) [15]. Then, for any unknown term, it could query that. In our current implementation, we did not use retrieval, but it is a promising extension for reliability (ensuring the LLM does not hallucinate and uses up-to-date info). Incorporating an internal knowledge base of network faults that the LLM can reference would make explanations even more precise. In fact, Isaac et al. (2025) used an LLM trained on 5G core documents to suggest fixes, demonstrating that domain-specific tuning yields actionable advice [38]. We could similarly fine-tune our LAE on, say, a corpus of historical incident reports to sharpen its explanations.

- IRBE is very fast and lightweight; it is essentially a set of pattern matches. We implemented it streaming through logs with negligible overhead (on the order of milliseconds per log entry). This can easily scale to thousands of logs per second, which is typical in telecom.

- SSC classification, once trained, is also quick. A Random Forest or small neural net can classify in microseconds per sample. The training of SSC (with pseudo-label iterations) is more expensive, but that can be carried out offline and perhaps on batch data. We did pseudo-labeling on approximately 5000 unlabeled samples in seconds; even for millions, it would be manageable with sufficient compute and maybe sampling.

- LAE is the most computationally heavy and potentially a bottleneck if used on every event. GPT-4-Class via API took ~2 s per explanation. If the system were to generate explanations for hundreds of alarms per minute, doing that sequentially would be an issue. However, in practice, critical fault alarms in a network are not that frequent, maybe a few per hour in normal conditions. It is feasible to handle those with an API call. If one needed to generate explanations for a flood of minor alerts, one could use a smaller LLM (e.g., GPT-3 or an open model), which can be faster or run multiple in parallel. We can also prioritize, perhaps, only use the LLM for significant incidents, whereas minor ones can just use rule text or a template. Since our focus is on major fault diagnosis, the latency of a couple of seconds is acceptable in an operational sense (it is still far quicker than human analysis, which might take minutes or hours). In any case, with model optimization and caching (common patterns explained once), the LAE overhead can be mitigated. Running a local instance of a model (like Llama-2) on a GPU could cut the explanation time to sub-second for shorter outputs based on some experiments we carried out with the smaller model (not reported in detail).

- End-to-End Deep Learning: Approaches where a deep model directly predicts faults from logs (e.g., CNN/RNN on raw log sequences). Such models (like those referenced in surveys [16]) can achieve high accuracy if well-trained, as in some BERT-based log classifiers hitting F1 > 0.95 on benchmarks. However, they typically need large, labeled datasets and are black boxes in nature. Our results (F1 ~0.89) may be slightly lower than the best deep models on simpler tasks, but we trade a bit of accuracy for explainability and low label requirement. In a domain like telecom, that trade-off is often worth it [1]. Moreover, our approach could incorporate such deep models in the SSC stage if the data allows the framework to be agnostic to the classifier type. We used RF for ease and interpretability, but one could plug in a Transformer-based log anomaly detector and keep the IRBE and LAE around it for explainability. In fact, using something like LogBERT [15] as the SSC could potentially raise the accuracy closer to 95% on known classes, and IRBE/LAE would guard and explain it [39]. This hybrid-within-hybrid is an interesting future path: use state-of-the-art deep anomaly detectors for raw power and our rule/LLM to temper and elucidate them.

- Pure Expert Systems vs. Pure LLM Solutions: On one end, older expert systems (rules only) are highly trusted but inflexible [2]. On the other hand, a stand-alone version of “ChatGPT for logs” might give you plausible analyses, but you cannot be sure that they will be consistent or complete. Hy-LIFT finds a balance, rules keep the system in check, and LLM adds flexibility. We do not rely too much on the LLM because we do not use it to make the main fault decision directly (that is, SSC’s job, except for new cases). This was carried out on purpose because current LLMs are smart, but they are not specialized or consistent enough to take the place of a trained classifier for known categories. Egersdoerfer et al. observed that ChatGPT occasionally misclassified without guidance [13]. Our approach ensures the LLM works in tandem with a reliable pattern detector and a learned model. This follows recommendations from studies like the log analysis survey [15] which suggest combining parsing, ML, and LLM for best results, rather than using an LLM blindly.

- Similar Frameworks: Tang et al.’s LLM-assisted and IDS-Agent [17] are conceptually similar in layering an analysis model with an explanation model [15]. Tang achieved a high detection accuracy (91%) focusing on heterogeneous network anomalies; IDS-Agent demonstrated improved zero-day detection using GPT. Hy-LIFT’s novelty is particularly in the semi-supervised learning integration and explicit rule-based stage. Neither of those works utilized a rule engine; Tang’s used attention-based semantic rules inside a model (less interpretable to humans, more like features), and IDS-Agent used multiple ML models, but still a black-box ensemble. We believe Hy-LIFT’s explicit, interpretable first stage is a distinguishing factor for real-world deployment, where existing rule systems are already in place (we effectively can augment an existing alarm system with learning and LLM layers, rather than replacing it). The strong performance of Hy-LIFT suggests that even if one has a sophisticated anomaly detector, adding a rule knowledge base can enhance it, an idea supported by Zhao et al.’s fusion results [4].

- Scalability and Replicability: Even though Hy-LIFT integrates several modules, it remains straightforward to deploy and operate in practice. The IRBE performs deterministic rule matching in only a few milliseconds per log entry, and the SSC (implemented as a Random Forest classifier) generates predictions in the microsecond range, so both components scale comfortably to high-volume log streams. The LLM-based explanation engine (LAE) is comparatively more expensive computationally, but it is only triggered for ambiguous or high-impact cases and therefore adds limited overhead on the order of roughly two seconds per explanatory query when using the GPT-4 API. We also outline strategies for scaling the LAE when needed, such as using more efficient language models or parallelizing inference during alarm bursts. Importantly, Hy-LIFT is data-efficient: strong performance was achieved with only ~1.2 k labeled logs by leveraging thousands of unlabeled logs through semi-supervised learning. This reduces the operational burden of acquiring large, annotated datasets. Moreover, the modular architecture enables straightforward transfer to new networks or domains; only the rule set and classifier need retraining, while the pipeline itself remains unchanged. These additions clarify that the framework is not only accurate and interpretable but also scalable, replicable, and viable for deployment in real 5G/6G environments [40,41].

- We have added a dedicated discussion on how Hy-LIFT can be applied to other operational contexts such as cloud systems, enterprise IT infrastructures, or IoT networks. The modular architecture of Hy-LIFT inherently supports domain transfer. Specifically, one can update the IRBE rule set to capture domain-specific signatures (e.g., rules for VM provisioning failures or IoT sensor communication faults), retrain the SSC on logs from the new environment using the same semi-supervised approach to handle scarce labeled data, and optionally fine-tune the LLM-based explanation component with domain terminology or knowledge. Importantly, no architectural modifications are required; each module (IRBE, SSC, LAE) can be adapted independently. This modular reconfiguration is significantly easier and more maintainable than redesigning an end-to-end monolithic model. By plugging in domain-relevant rules and data, Hy-LIFT can seamlessly migrate to cloud, enterprise, or IoT scenarios, demonstrating strong extensibility and practical value beyond 5G/6G network settings [42].

- It currently handles only the classification of faults of types it knows, plus a generic handling of unknowns. It does not carry out root cause analysis (RCA) beyond identifying the fault category and immediate cause. True RCA might require correlating multiple events across network elements (e.g., pinpointing that a router failure caused many cell outages). Our framework could potentially assist in RCA by using LLM to connect the dots between multiple fault instances (LLMs are good at reading and summarizing multiple inputs), but we have not explicitly built cross-correlation logic. A next step could be feeding the LLM with combined logs from several cells to say “these 5 cells went down around the same time, possibly due to a common backhaul node failure,” essentially letting it hypothesize higher-level causes. There is ongoing research in telecom RCA using AI (e.g., Bayesian networks, graph analysis); integrating that with our approach could be fruitful.

- The quality of IRBE rules and initial labels heavily influences performance. If we missed an important pattern in rules, and it is also rare in data, SSC might never learn it. The framework is not magically going to detect something where there is zero signal. That said, the LLM might flag something as strange if truly anomalous, even if no class, but it may not label it correctly. Thus, Hy-LIFT is only as good as the knowledge it is given, plus what it can infer from the data. We tried to simulate a realistic scenario, but in a new domain or a very novel fault, human input would still be needed to incorporate that knowledge.

- Another limitation is the dependency on an external LLM (if using a closed API like GPT-4-Class). We were worried about data privacy (we protected it by anonymizing it and could choose on-prem models) and consistency (the LLM might act differently with updates or different prompts). We saw the LLM as a module that could be replaced; you could use an in-house model instead. One thing we did was use prompt engineering to make sure that the output was always in the same format (for example, we told it to start with a summary sentence, etc.). In production, you might want even more structured explanations, like a set template or JSON with fields for cause, effect, and recommendation. Right now, ours are free-form paragraphs. You could understand all of them, but NOC workflows need things to be clear and short (you do not want a page-long summary). We could look into prompt constraints or fine-tuning to make the outputs more consistent.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5GC | 5G Core |

| 6G | Sixth-Generation Mobile Networks |

| gNB | Next-Generation NodeB (5G base station) |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UPF | User Plane Function (5GC) |

| RRC | Radio Resource Control |

| SINR | Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| Hy-LIFT | Hybrid LLM-Integrated Fault Diagnosis Toolkit |

| IRBE | Interpretable Rule-Based Engine |

| SSC | Semi-Supervised Classifier |

| LAE | LLM Augmentation Engine |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Senevirathna, T.; La, V.H.; Marcha, S.; Siniarski, B.; Liyanage, M.; Wang, S. A Survey on XAI for 5G and Beyond Security: Technical Aspects, Challenges and Research Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 941–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Lu, S. Detection of Mobile Network Abnormality Using Deep Learning Models on Massive Network Measurement Data. Comput. Netw. 2021, 201, 108571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuah, E.A.; Wu, M.; Zhu, X. Cellular Network Fault Diagnosis Method Based on a Graph Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2023, 23, 7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; He, C.; Zhu, X. A Fault Diagnosis Method for 5G Cellular Networks Based on Knowledge and Data Fusion. Sensors 2024, 24, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Fung, C.; He, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Luan, Z. Transfer Log-Based Anomaly Detection with Pseudo Labels. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Conference on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Izmir, Turkey, 2–6 November 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, J.; Dong, X.; Zhang, W. PLELog: Semi-Supervised Log-Based Anomaly Detection via Probabilistic Label Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings (ICSE-Companion), Madrid, Spain, 25–28 May 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 230–231. [Google Scholar]

- Sangaiah, A.K.; Rezaei, S.; Javadpour, A.; Miri, F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, D. Automatic Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Cellular Networks and Beyond 5G: Intelligent Network Management. Algorithms 2022, 15, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, E.J.; Barco, R.; Gomez-Andrades, A.; Serrano, I. Diagnosis Based on Genetic Fuzzy Algorithms for LTE Self-Healing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, P.; Novaczki, S. An Automatic Detection and Diagnosis Framework for Mobile Communication Systems. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2012, 9, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uszko, K.; Kasprzyk, M.; Natkaniec, M.; Chołda, P. Rule-Based System with Machine Learning Support for Detecting Anomalies in 5G WLANs. Electronics 2023, 12, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fu, Z.; Li, X. A Graph Deep Learning-Based Fault Detection and Positioning Method for Internet Communication Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102261–102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Li, P.; Piechocki, R.; Inacio, R. Anomaly Detection in Offshore Open Radio Access Network Using Long Short-Term Memory Models on a Novel Artificial Intelligence-Driven Cloud-Native Data Platform. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yuan, S.; Trabelsi, M. LogGPT: Log Anomaly Detection via GPT. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Egersdoerfer, C.; Zhang, D.; Dai, D. Early Exploration of Using ChatGPT for Log-Based Anomaly Detection on Parallel File Systems Logs. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on High-Performance Parallel and Distributed Computing, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–23 June 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 315–316. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Khan, S.; Parkinson, S. LLM-Based Event Log Analysis Techniques: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wang, X.; Yuan, X.; Luo, L.; Zhao, M.; Huang, T.; Kato, N. Large Language Model(LLM) Assisted End-to-End Network Health Management Based on Multi-Scale Semanticization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2406.08305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Kostakos, P. HuntGPT: Integrating Machine Learning-Based Anomaly Detection and Explainable AI with Large Language Models (LLMs). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirjees, S.W.; Alkhalid, F.F.; Hasan, A.M.; Humaidi, A.J. A Secure Password based Authentication with Variable Key Lengths Based on the Image Embedded Method. Mesopotamian J. Cybersecur. 2025, 5, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Bastian, N.D.; Song, D.; Li, B. IDS-Agent: An LLM Agent for Explainable Intrusion Detection in IoT Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, T.; Sandeepa, C.; Siniarski, B.; Nguyen, M.-D.; Marchal, S.; Boerger, M.; Liyanage, M.; Wang, S. Enhancing Accountability, Resilience, and Privacy of Intelligent Networks With XAI. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 8389–8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, S.N.; Güllü, M.; Karhan, D.; Çimen, S.; Osmanca, M.S.; Barışçı, N. Realistic Performance Assessment of Machine Learning Algorithms for 6G Network Slicing: A Dual-Methodology Approach with Explainable AI Integration. Electronics 2025, 14, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.D.; Zeyad, A.T.; Al-karkhi, A.A.S.; Raafat, S.M.; Humaidi, A.J. Hybrid CDN Architecture Integrating Edge Caching, MEC Offloading, and Q-Learning-Based Adaptive Routing. Computers 2025, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ling, S.; Liu, S. Semi-Supervised Medical Image Classification with Pseudo Labels Using Coalition Similarity Training. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Pei, X. Semi-Supervised Learning via DQN for Log Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.03151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, J.; Rodrigues, P.; Almeida, L.; Teixeira, R.; Antunes, M.; Aguiar, R. From Black Box to Transparency: The Hidden Costs of XAI in NGN. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Cape Town, South Africa, 8–12 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, Y. Knowledge-Assisted Few-Shot Fault Diagnosis in Cellular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 1292–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Moulay, M.; Leiva, R.G.; Maroni, P.J.R.; Lazaro, J.; Mancuso, V.; Anta, A.F. A Novel Methodology for the Automated Detection and Classification of Networking Anomalies. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–9 July 2020; pp. 780–786. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Huang, S.; Luan, Z.; Yang, S.; Fung, C.; Yang, H.; Qian, D.; Shang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, Z. LogGPT: Exploring ChatGPT for Log-Based Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on High Performance Computing & Communications, Data Science & Systems, Smart City & Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Melbourne, Australia, 17–21 December 2023; pp. 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Ye, J.; Hu, C.; Yan, L. LLM-LADE: Large Language Model-Based Log Anomaly Detection with Explanation. Knowl. Based Syst. 2025, 326, 114064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, Y.; Fung, C.; He, R.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Luan, Z. Paddy: An Event Log Parsing Approach Using Dynamic Dictionary. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2020—2020 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, T.; Ma, S.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, T.; Tao, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lin, D.; Liu, C.; Cai, Y.; et al. LogEval: A Comprehensive Benchmark Suite for Large Language Models In Log Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.01896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Qureshi, M.A.; Miralles-Pechuán, L.; Huynh-The, T.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Liyanage, M. Explainable AI for 6G Use Cases: Technical Aspects and Research Challenges. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2024, 5, 2490–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, Y.; Porambage, P.; Liyanage, M.; Ylianttila, M. AI and 6G Security: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), Porto, Portugal, 8–11 June 2021; pp. 616–621. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Qureshi, M.A.; Miralles-Pechuán, L.; Huynh-The, T.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Liyanage, M. Applications of Explainable AI for 6G: Technical Aspects, Use Cases, and Research Challenges. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2112.04698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, F.; Moghimifar, F.; Haffari, R.; Li, Y.-F.; Nguyen, V.; Yoo, J. Decompose, Enrich, and Extract! Schema-Aware Event Extraction Using LLMs. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Venice, Italy, 8–11 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W.; Cao, J.; Qian, S.; Gao, J.; Ouyang, C. LogLLM: Log-Based Anomaly Detection Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.08561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porch, J.B.; Heng Foh, C.; Farooq, H.; Imran, A. Machine Learning Approach for Automatic Fault Detection and Diagnosis in Cellular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom), Odessa, Ukraine, 26–29 May 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, J.H.R.; Saradagam, H.; Pardhasaradhi, N. 5G Core Fault Detection and Root Cause Analysis Using Machine Learning and Generative AI. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.09152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, A.; Mo, D.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Wen, Q. LogParser-LLM: Advancing Efficient Log Parsing with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, O.K.; Abdullah, F.; Radzi, N.A.M.; Salman, A.D.; Abdulkadir, S.J. Survey on Clustered Routing Protocols Adaptivity for Fire Incidents: Architecture Challenges, Data Losing, and Recommended Solutions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113518–113552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, O.; Abdullah, F.; Radzi, N.A.M.; Salman, A.D. New Adaptive-Clustered Routing Protocol for Indoor Fire Emergencies Using Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM Model: Development and Validation. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2025, 14, 08–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, A.; Seitz, J. An Approach for QoS-Aware Routing in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems (ISWCS), Brussels, Belgium, 25–28 August 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 626–630. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, L.; Cao, J.; Cai, J. Fault Diagnosis of 5G Networks Based on Digital Twin Model. China Commun. 2023, 20, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, Z.M.; Salman, A.D. Cloud-Based Voice Home Automation System Based on Internet of Things. Iraqi J. Sci. 2022, 63, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.P.V.V.; Juliet, A.H.; Jayadurga, R.; Sethu, S. A Novel Method to Identify and Recover the Fault Nodes over 5G Wireless Sensor Network Environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 Asia Pacific Conference on Innovation in Technology (APCIT), Mysore, India, 26–27 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Lin, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X. A Graph Neural Network Based Fault Diagnosis Strategy for Power Communication Networks. J. Chin. Inst. Eng. 2024, 47, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.A.; Hamza, E.K.; Humaidi, A.J. A Modified CNN-IDS Model for Enhancing the Efficacy of Intrusion Detection System. Meas. Sens. 2024, 35, 101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Accuracy | Macro-Precision | Macro-Recall | Macro-F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRBE (Rules only) | 74.8% | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.70 |

| Supervised ML (RF) | 82.5% | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| Semi-Supervised (SSC only) | 86.1% | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.86 |

| Hy-LIFT (IRBE + SSC) | 89.2% | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Fault Type | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support (#) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage Drop | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 40 |

| Handover Failure | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 60 |

| Backhaul Fault | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 50 |

| Overload (Congestion) | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 70 |

| Hardware Failure | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 30 |

| Macro Avg | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 250 total |

| Overall Accuracy | - | - | 0.892 | 250 total |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salman, A.D.; Zeyad, A.T.; Jumaa, S.S.; Raafat, S.M.; Jasim, F.H.; Humaidi, A.J. Hybrid LLM-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Framework for 5G/6G Networks Using Real-World Logs. Computers 2025, 14, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120551

Salman AD, Zeyad AT, Jumaa SS, Raafat SM, Jasim FH, Humaidi AJ. Hybrid LLM-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Framework for 5G/6G Networks Using Real-World Logs. Computers. 2025; 14(12):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120551

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalman, Aymen D., Akram T. Zeyad, Shereen S. Jumaa, Safanah M. Raafat, Fanan Hikmat Jasim, and Amjad J. Humaidi. 2025. "Hybrid LLM-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Framework for 5G/6G Networks Using Real-World Logs" Computers 14, no. 12: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120551

APA StyleSalman, A. D., Zeyad, A. T., Jumaa, S. S., Raafat, S. M., Jasim, F. H., & Humaidi, A. J. (2025). Hybrid LLM-Assisted Fault Diagnosis Framework for 5G/6G Networks Using Real-World Logs. Computers, 14(12), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14120551