Abstract

The increasing demand for customized products has raised the significant challenges of increasing performance and reducing costs in the industry. Facing that demand requires operators to enhance their capabilities to cope with complexity, demanding skills, and higher cognitive levels, performance, and errors. To overcome this scenario, a virtual instructor framework is proposed to instruct operators and support procedural quality, enabled by the use of You Only Look Once (YOLO) models and by equipping the operators with Magic Leap 2 as a Head-Mounted Display (HMD). The framework relies on key modules, such as Instructor, Management, Core, Object Detection, 3D Modeling, and Storage. A use case in the automotive industry helped validate the Proof-of-concept (PoC) of the proposed framework. This framework can contribute to guiding the development of new tools supporting assembly operations in the industry.

1. Introduction

The increasing demand for customized products has transformed mass production. Hashemi-Petroodi et al. [1] describe mass production as assembly lines that repetitively produce the same item in large batches, prioritizing the production of smaller quantities of different items.

Assembling processes are key in the industry for combining components into an end product. However, assembly goes beyond a simple sequence of operations. According to Miqueo et al. [2], operators are responsible for processing information, solving problems, managing social interactions, prioritizing operations, and continuously learning in their work environment. Coordinating such a scenario is cognitively demanding and increases the failure rate. As emphasized in [3], this becomes even more relevant when new operations are introduced to assembly lines.

This scenario led to a significant increase in manual assembly complexity to face the demand for new skills in a continuous learning workflow, which is essential to maintain operation performance and reduce the complexity of operations requiring manual assembly.

The demand for reducing the learning curve for operators acquiring new skills has led, as observed by Chiang et al. [4], to the adoption of other approaches such as educational programs designed to provide knowledge and skills in particular activities. Key benefits include reducing training time, error rates, and cognitive load; providing immediate feedback; improving performance, the motivation to learn, and assembly skills; positively impacting long-term memory; and streamlining complex operations.

In [5], the authors define Industry 4.0 as an intelligent digital network composed of people, equipment, and objects, designed to manage business processes and value creation networks. Industry 4.0 has leveraged the use of sensors for monitoring ongoing physical operations and operators. Another approach discussed in [6] is Augmented Reality (AR), which provides an interface between the virtual and real worlds, enabling rapid training and the sustainable improvement of operator performance. While adopting machines in automation processes improves the production process, it does not provide the flexibility that human operators have in manual assembly processes. Moreover, such an approach lacks creativity in operating different tools and equipment, unlike humans [1]. This situation keeps manual assembly operations relevant and takes a more prominent role in the current context. Furthermore, Adel [7] stated that in the fifth industrial revolution, humans are expected to take a central role in industrial operations as they are expected to promote and increase collaboration between humans and machines.

As explained in [8], AR enhances the user’s visual field by overlaying information relevant to the task at hand by combining virtual objects with the physical environment, which according to Peikos and Sofianidis [9] creates the impression that both coexist in the same space. Immersion in a three-dimensional context not only facilitates the understanding of complex actions but also reinforces the memorization of technical information. As pointed out in [10], this happens because direct experience tends to have a more profound impact than passive teaching approaches (e.g., paper notes).

AR adoption in manufacturing has grown significantly, offering an effective means of conveying task-related content directly within real-world settings in an immersive format. As reported in [11], AR enables intuitive access to information that would otherwise be inaccessible, supporting operators with clear guidance while helping to minimize human errors and reduce cognitive strain.

The Mixed Reality (MR) concept extends the capabilities of AR, blending user interactions in real time between virtual and physical world elements. For example, MR can help remotely support assistance to operations. Experts can collaborate remotely in a virtual environment with operators as if they were in the same physical space [12]. MR not only enriches the experience with digital information but also integrates it interactively and immersively into the real environment, improving work accuracy and efficiency.

Azuma [13] defines HMDs as wearable display devices that are mounted on the user’s head and position a small display in front of one (monocular) or both (binocular) eyes. These devices overlay a virtual scene onto the real-world environment and present it within the user’s field of vision. The augmented information, which appears on top of the real surroundings, can either add to or obscure the view, depending on whether it consists of symbolic data or visual imagery. As noted by John et al. [14], they are commonly used in Virtual Reality (VR), AR, and other immersive environments to deliver visual content directly to the user’s field of view, enabling interactive and immersive experiences. An HMD can be used to have an interactive environment that fosters the adaptation and creativity of operators in educational contexts.

Palmarini et al. [6] highlight the importance of improving AR procedures with intelligent elements powered by Machine Learning (ML). These components leverage computers to learn from the data and make informed decisions. In this context, Deep Learning (DL) uses artificial neural networks to process complex data. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a specific type of model DL, is particularly effective in automatically extracting high-level features from raw input data, such as in image processing [15]. By integrating DL with MR, this PoC aims to further enhance the potential of MR through intelligent Computer Vision (CV) techniques, improving the production quality.

After introducing the topic and motivation and explaining the background, this study proposes a virtual instructor framework to improve operator performance and well-being. This framework gathers the features to assess ongoing operations performance. Our contributions are multi-fold:

- A framework for instructing operators along running operations.

- An HMD application to assess the quality of assembly operations.

- DL models to assess the execution of assembly operations.

- Three-dimensional animations to support operators.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature with the related work. The proposed framework is presented in Section 3. Section 4 describes the validation work in a use case with a PoC. Section 5 discusses the achieved results. Finally, Section 6 concludes this paper and suggests directions for future work.

2. State of the Art

This section reviews the literature on the use of virtual and physical training environments to reduce the reliance on specialized human instructors in operating specific machines.

Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly in the form of computer vision, has become a cornerstone of modern quality control in manufacturing. Traditional visual inspection methods are increasingly being replaced or enhanced by AI-driven systems due to their high speed, consistency, and ability to detect subtle or complex defects [16,17].

Deep Learning, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in various inspection tasks. These models can detect surface anomalies such as cracks, scratches, or deformations on metal, glass, or composite surfaces with high accuracy [18]. Additionally, Object Detection frameworks like YOLO or Faster R-CNN are widely used for identifying missing components or verifying assembly correctness [19].

In situations where labeled defect data is scarce, unsupervised methods using autoencoders or generative adversarial networks (GANs) have shown strong performance in anomaly detection by learning representations of “normal” data and flagging outliers [20].

One important advancement is the deployment of AI models directly on edge devices, enabling real-time inline defect detection during manufacturing processes. These systems reduce latency and minimize the reliance on AI cloud infrastructure [21]. The combination of high-speed industrial cameras and lightweight AI inference engines allows for a immediate rejection of defective parts, increasing throughput and reducing waste.

Despite significant progress, AI-powered visual inspection systems face challenges. Data imbalance remains a key issue—defects are typically rare, leading to limited training examples [17]. Moreover, AI models often suffer from poor generalization when applied to new products, materials, or lighting conditions. The black-box nature of Deep Learning also introduces issues with explainability, particularly in safety-critical or regulated industries [16].

Several leading manufacturers have already adopted AI-based visual inspection systems. For instance, BMW uses AI at its Regensburg plant to inspect car body surfaces for defects, significantly improving both precision and inspection time [22]. Similar applications can be found in the electronics, steel, and pharmaceutical industries, where high-throughput and precision are essential.

Current research focuses on improving model robustness, leveraging synthetic data and data augmentation, and developing explainable AI techniques for transparent inspection decisions [17]. Federated learning and transfer learning are also being explored to enable cross-factory AI deployment without compromising data privacy.

Next, we present some related work.

In the automotive sector, [23] explored real-time quality inspection on assembly processes, using MR and CV by integrating an HMD Hololens video integrated with an Image Recognition (IR) server for detecting defects. Instant feedback with holograms facilitates timely correction in case of deviations. Ford Motor Company adopted Microsoft’s HoloLens in vehicle design. In this way, professionals are instructed in real time, accelerating decision-making [24]. Nogueira [25] highlighted the applicability of the YOLO model to industrial environments, particularly to automate quality control, detect defects and faults, locate missing parts during real-time product inspection, and ensure compliance with quality standards [26], which Unreal [27] uses in future deployments. Porsche applied the MR concept to assist and train service technicians. Using an HMD, technicians receive immediate visual assistance, making complex operations easier to perform and reducing the dependency on conventional manuals [28]. Enabling a safe learning environment is another advantage of this technology. Audi simulated assembly processes, allowing operators to practice specific operations in a secure context before performing them on the assembly line [29].

Beyond the automotive and aviation sectors, other industries have explored the benefits of MR and CV integration in reducing training overhead, improving safety, and enhancing quality control across diverse sectors.

In the aviation sector, Boeing adopted MR for training mechanics and technicians. Through step-by-step visual instructions, they could take advantage of several benefits, such as improving maintenance, reducing training time, and reducing the number of errors made [30].

In the construction sector, companies such as Trimble have implemented AR-based guidance systems for building assembly and structural verification, reducing rework and increasing on-site productivity [31].

In the healthcare sector, surgeons have used MR for preoperative planning and intraoperative guidance. Yang et al. [32] reported improved spatial awareness and accuracy in maxillofacial surgeries using MR navigation.

In the maintenance sector, Palmarini et al. [6] proposed the adoption of maintenance procedures for non-specialist technicians. They used tools such as Vuforia and Unity 3D. Such an approach allowed virtual objects to be overlaid over real ones by signaling the correct position and orientation.

In the energy sector, Siemens Energy adopted MR to support the remote maintenance of power systems. Technicians use HoloLens to receive real-time support from off-site experts, improving fault resolution time [33]. Several studies have explored training operators for emergencies and strengthening their response capacity without exposing them to real dangers. Honeywell also explored MR in high-risk scenarios, simulating controlled environments of chemical plants and refineries to train its employees [34].

Table 1 summarizes the related work for different sectors. In comparison to the related work, this paper combines Artificial Intelligence (AI) and AR for real-time training and error detection in the automotive industry by leveraging our previous work [23,25].

Table 1.

Related work summary.

3. The Virtual Instructor Framework

This study proposes a virtual instructor framework to support building new tools to instruct operators in the automotive industry. It includes monitoring capabilities by tracking operator performance by measuring training and production performance.

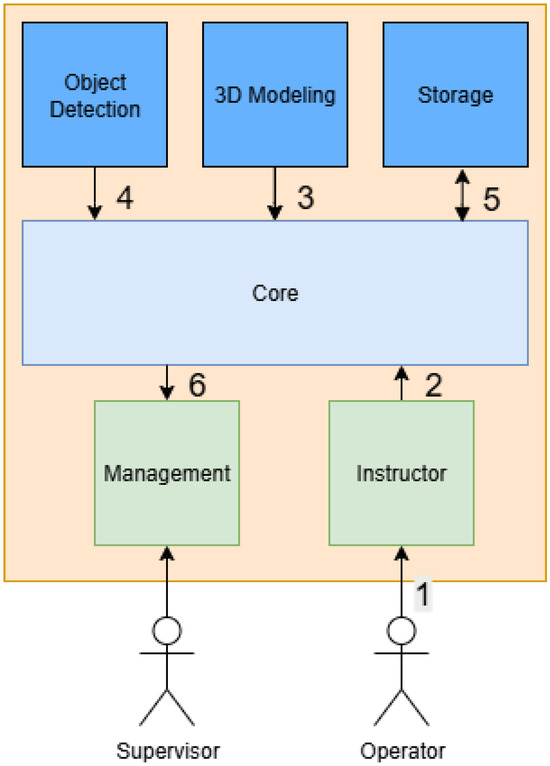

Figure 1 depicts the reference architecture of the proposed framework. It includes the building blocks and the underlying communication flows (1 to 6). The following building blocks are included: Management, Core, Object Detection, 3D Modelling, Storage, and Instructor.

Figure 1.

Reference architecture.

Two different profiles exist: supervisors manage training, and operators receive training. Supervisors customize the operators’ training operations using the Management module. They can define the operators, training, projects, and operations. Projects encompass the features to support the implementation of different use cases, such as vocational and workplace training. The last project involves processing DL models defined in the Management module and made available by the Core module. Operators receive the instructions defined by supervisors, helped by the 3D Modeling module, and their operations are assessed by the Object Detection module via the Core module.

Regarding the data flows, the Instructor module leverages the use of MR (1) to instruct the equipped operators with an HMD as the Instructor module (1). The Core module provides the following key features: step-by-step instructions presented as three-dimensional and visual animations retrieved from the 3D Modeling module (3) and assessing the operations running supported by the Object Detection module (4). All the collected and tracked performance data, such as execution time and error detection, persisted in the Storage module (5). Later, that data are made available to supervisors (7). Moreover, it also integrates key features such as authentication, project selection, and operation execution retrieved from the Core and Storage modules. The data in those flows are kept secure and private by encrypting the underlying communications.

The Object Detection module leverages the use of DL models based on Object Detection (OD), aiming to automate operation validation during training. Object Detection involves identifying the class to which an object belongs and determining its exact position in the image. Two models were used to achieve distinct objectives regarding on-the-job procedures. The first identifies the parts from the objects needed to assemble a given product to automate the preparation phase, ensuring that the materials required to execute the operations are available. The second model asses the correct step if the ongoing operation is effectively finished, preventing moving forward to the next step.

The Object Detection module performs procedural quality by classifying the images from the ongoing running operations. Images are retrieved from the Instructor module via the Core module. The Application Programming Interface (API), implemented as part of the Core module, queries the database to identify which DL model to use in the ongoing operation to determine the involved objects. The model identifies the objects by running the model against the provided image. All the identified objects are returned to the Instructor module in real time, helping to assess if the operator completed the ongoing operation.

The Core module API plays a central role in supporting the integration of different modules, such as interfacing the communication between the Instructor and Management modules. This is especially important due to the limited HMD hardware while supporting the application interface with 3D elements; it would also have to handle the process management and the model inference, leading to its overload.

4. A Proof-of-Concept Case

This section describes a PoC demonstrating the capabilities of the proposed framework. We start by presenting the use case and then dive into the details of the implementation of the PoC of the proposed framework, namely the details about each one of the modules.

A PoC of the proposed framework aims to demonstrate its applicability in instructing operators in the context of supporting procedural quality as part of the GreenAuto agenda [35] (Green Innovation for the Automotive Industry), specifically within the scope of its PPS 15 and Work Package 9.

The proposed framework adopts MR for instructing operators by using an HMD when manually assembling products. In this scenario, the MR system combines the real world with virtual elements, instructing operators on the correct assembling procedure, using 3D diagrams of the product parts and even animations showing how to disassemble and reassemble the components. The virtual instructions are overlaid in the real world, allowing the technician to see clearly where to act while interacting with the physical object. At the same time, the system can provide information about the machine’s status and alert the operator to errors or incomplete steps.

The underlying communications among different modules are kept secure and private by encrypting data flows. In this regard, the Core module was enabled with an HTTPS service relying on an issued SSL certificate.

4.1. The Pneumatic Cylinder Assembly Use Case

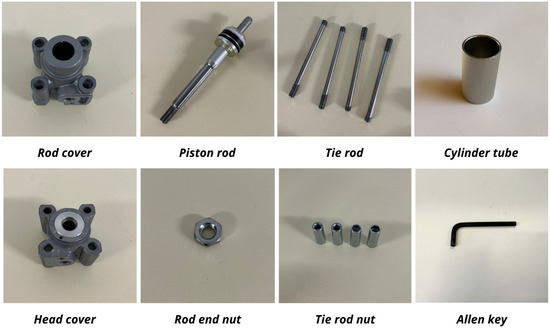

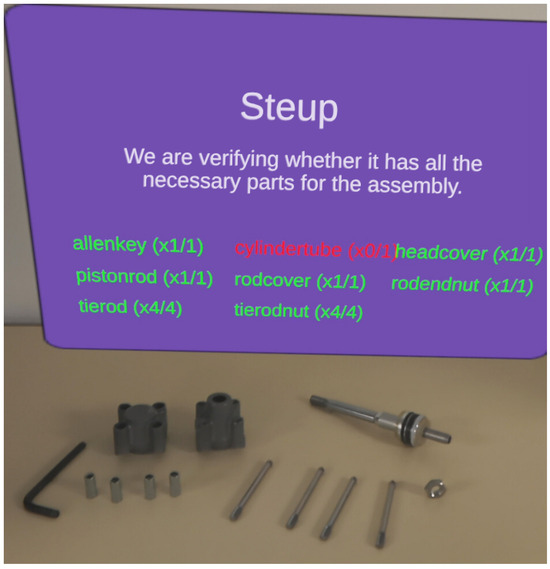

A training use case helps to demonstrate the capabilities of the virtual instructor framework. For that purpose, a Pneumatic Cylinder (PC) assembly operation was selected to demonstrate the PoC due to its common use in industry and easy availability for testing. This device aims to convert the compressed air into mechanical movement [36]. This is possible by moving a piston inside a PC, where the introduced air causes pressure, moving it in a linear direction. It is essential in industrial systems where precise movements are required. Figure 2 illustrates seven PC distinct parts. In addition to the two already mentioned, these include a rod cover, head cover, tie rod, rod end nut, and tie rod nut. In addition, the image consists of the Allen key required to tighten the tie rod nuts.

Figure 2.

Pneumatic Cylinder assembly parts.

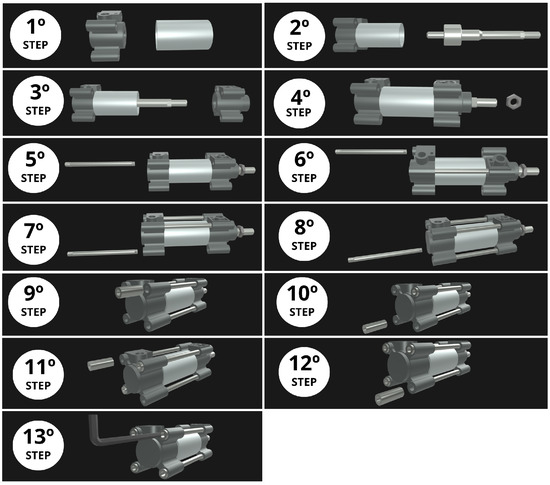

4.2. The 3D Modeling Module

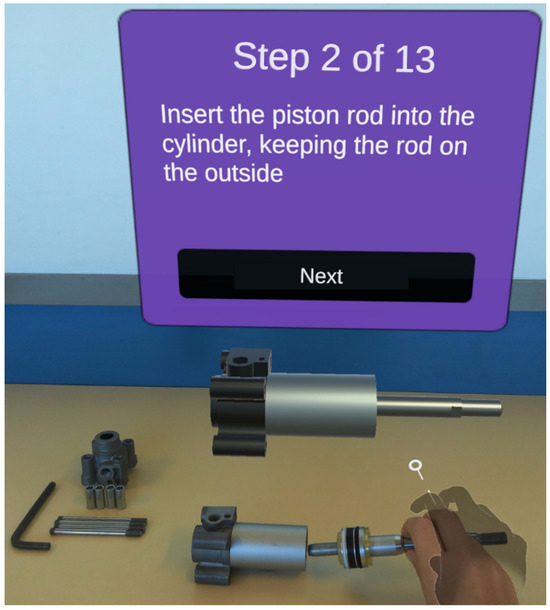

The design of 3D animations aimed to facilitate the operators’ training with animations of the framework 3D Modeling module. In validating the PoC, a 3D animation was assigned for one step along the PC assembly use case. The aim of the animations was to instruct operators to mimic movements for proper assembly. Blender was used to develop animations integrating the different PC components according to the correct assembly sequence. In total, 13 animations were built corresponding to each step of the assembly operation, as represented in Figure 3. This way, users can follow the suggested physical movements when running their operations.

Figure 3.

Pneumatic Cylinder assembly: 3D animations.

4.3. The Management Module

This section describes the results from implementing the Management module tools used to demonstrate a PoC.

Supervisors are the actors able to manage the application. They can manage operators with their names, priority level (urgent, high, normal, or low), a brief description, and the user responsible in case additional support is required during operation execution. The supervisor can also define new projects and operations for training by including detailed instructions, supported by an animation, and assigning them to operators.

This module provides monitoring capabilities by tracking operators’ performance by recording the running time, which will later be reported. Log errors are recorded based on project type. In the case of workplace training, errors are recorded when operators attempt to proceed before completing previous operations, and in quality control, errors are logged upon detecting specific failures. Django [37] supported the implementation of the framework Management module and streamlined its development by requiring less code and reducing the time taken.

4.4. The Instructor Module

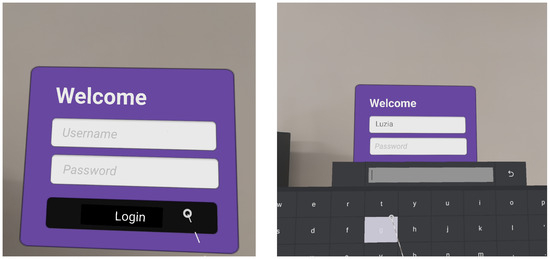

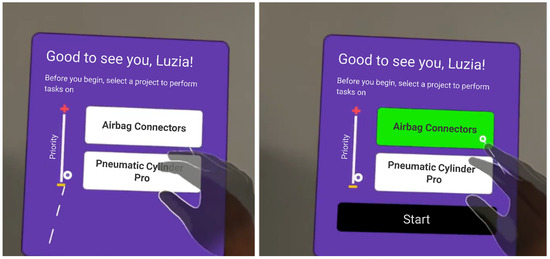

This section presents the result of implementing the Instructor module, including the resulting User Interface (UI), and describes the adopted MR technology. Figure 4 depicts how the operator has authentication for the Instructor UI. Then, the operator selects a project, as presented in Figure 5. The operations that have not been completed are listed according to their priority.

Figure 4.

Operator authentication UI.

Figure 5.

Project selection UI.

Upon project selection, the system verifies that all required parts are available in the necessary quantities, as shown in Figure 6, helping to maintain smooth operation on the assembly line. Since all objects are detected, the operations to be completed are returned. The operator can check the provided instructions in the training animations from the 3D Modeling module, which contains instructions that overlap with the physical work environment. Therefore, Figure 7 represents the operation and the corresponding 3D animation guiding one of the steps of the PC assembly operation. After that, the operator can proceed and complete the assigned operation. Its performance is tracked during the operation by recording all the actions and execution times.

Figure 6.

YOLO-based model automatically validating the assembly setup to ensure procedural quality.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional animations assisting the Pneumatic Cylinder assembly operation.

Unity [26] was selected to implement the Instructor module, guiding the operation execution. The decision to adopt Unity was made exclusively on the grounds of technical suitability without any commercial considerations. This development environment supports the creation and manipulation of interactive elements and enables deployment across various HMDs. Its flexibility has made it widely used in areas such as entertainment, cinema, automotive, education, and manufacturing, allowing for the development of dynamic solutions for different platforms. Such versatility is supported by a range of modules, including Android Build Support, which enables exporting applications to Magic Leap devices, and the Mixed-Reality Toolkit (MRTK), which facilitates the integration of MR interactions and UI components.

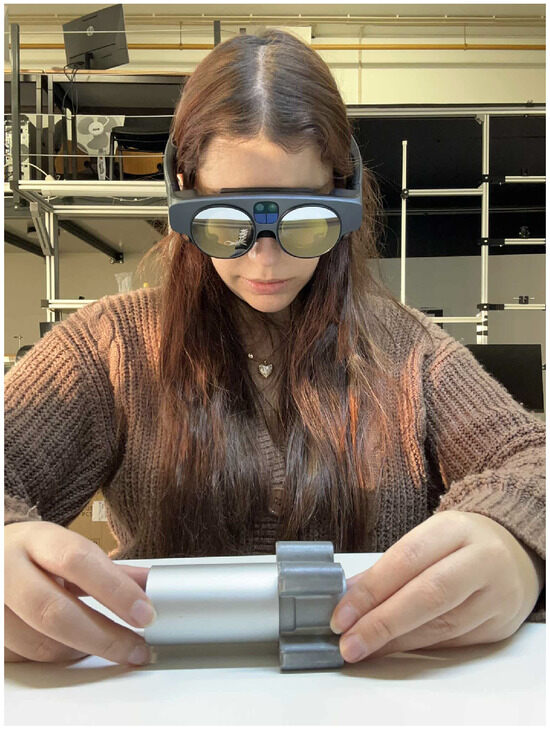

Regarding the Instructor module’s implementation, Magic Leap 2 was adopted [38]. Magic Leap 2 is an HMD leveraging the use of MR, allowing for the integration of digital content into the operator’s physical space. Its ergonomic and lightweight design contributes to it being used for extended periods. Magic Leap 2 includes a headset, as illustrated in Figure 8, a computer pack, and a controller. It has a field of view of up to 70 grades and a 1440 × 1760 resolution per eye. Its computing unit includes a quad-core AMD processor with Zen 2 architecture, 16 GB of RAM, and 256 GB of internal storage. The controller facilitates use through optical tracking and inertial sensors.

Figure 8.

Magic Leap 2 Instructor module.

4.5. The Object Detection Module

The implementation of the Object Detection module was supported by the use of YOLO and Ultralytics. YOLO is a family of algorithms supported by CNNs capable of identifying multiple objects in an image with a single pass [39]. It also allows for implementing custom models for different purposes, such as classification, OD, and segmentation [40]. In implementing the Object Detection, it was also considered that Ultralytics could train YOLO models with custom datasets and, later, for IR. Ultralytics represents a specialized solution in CV, allowing for the transformation of images into valuable data [41] and enabling the implementation of the continuous development of the YOLO model [42]. Ultralytics allows us to run YOLO models and offers advanced tools to classify new visual data through its simple integration into existing systems [43].

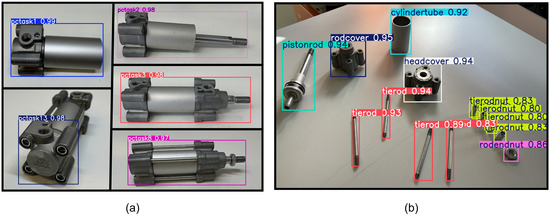

Two fine-tuned YOLOv8 models were implemented for the PC use case. The first model operates during the setup phase, detecting and counting the parts required for assembly. The second model runs during assembly execution, validating whether each step has been completed correctly. The system continuously monitors operator actions and provides alerts if a step is skipped or executed incorrectly. Once a task is completed and validated by the YOLOv8 model, the operator may proceed. All errors are recorded for subsequent performance analysis. The models were trained on task-specific annotated datasets, consisting of 1200 annotations for the setup model and 1949 annotations for the assembly validation model. Figure 9 illustrates their performance, showing task validation in panel (a) and part detection in panel (b).

Figure 9.

Performance of customized YOLOv8 models. (a) Detecting parts; (b) monitoring assembly.

The present module is designed to support step-by-step procedural guidance and operator performance monitoring.

4.6. The 3D Modelling Module

Regarding the implementation of the 3D Modeling module, Blender [44] helped to build 3D animations for instructing operators. It also enables high-quality animations for short films, advertisements, and other multimedia works. This module plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between engineering Computer-Aided Design (CAD) models and their applicability in MR environments. Although automotive components were originally designed as precise CAD models containing detailed dimensions, tolerances, and manufacturing data, these raw files are not directly suitable for interactive training scenarios. To overcome this limitation, the CAD geometries were prepared for MR integration. The original CAD files from Nogueira [25] were exported from Autodesk Inventor to the OBJ format. This format was chosen because, unlike Standard Triangle Language (STL), it preserves color and material information. The exported models were then imported into Blender, where they were refined, assigned materials, and animated. The resulting sequential animations visually guide operators during assembly, thereby supporting procedural learning.

For exporting animated scenes, the GLB file type was selected instead of other options, such as FBX, because of the specific demands of the Unity environment. GLB is the binary version of the glTF (GL Transmission Format), an open standard for efficient 3D model transmission, as detailed by Khronos Group [45]. This optimized binary standard combines the model, animation, and textures into a single file, ensuring efficient real-time data transfer. The choice ensures compatibility with the GLTFUtility repository [46], which interprets these files and presents them in the application without additional conversions. The Json.NET package [47] simplifies the integration of the resources received by the API and supporting project requirements.

4.7. The Core and Storage Modules

The Core module comprises an API offering support for Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD) operations of the entities to be managed in the Storage module. This API follows the Representational State Transfer (REST) [48] architectural style using HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) methods, such as GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE. Django [49] was used to implement the Core module. The implementation of the Storage module relied on a MySQL Relational Database [50] to organize, store, and manage all data.

The proposed framework is based on two main processes, namely on-the-job training and vocational training. On-the-job training combines task guidance with image analysis to detect whether each assembly step on the assembly lines has been completed correctly, ensuring the proper execution of tasks. Vocational training focuses exclusively on skill acquisition through interactive content. Each process is supported by specific API endpoints. The endpoints process_task and setup_process handle model inference for task validation and component presence check, respectively. The setup_process endpoint serves as a preparatory phase within on-the-job training, verifying that the required components are available to prevent production delays. The piece_classes endpoint provides the list of component classes relevant to each task, enabling targeted detection and the counting of parts. Other general endpoints, such as tasks_of_project, performance, and animations, manage task retrieval, user performance metrics (task completion, timestamps, and errors), and 3D instructional content. The login endpoint handles user authentication, and user_projects lists projects with pending tasks assigned to the user.

To evaluate the performance, latency for endpoint processes was evaluated according to Table 2. Two complementary metrics were considered, namely end-to-end latency, representing the total time from the Instructor module sending a request to the Core module and receiving a response, and server response time, which corresponds to the time required by the Core module to process the request and generate the response.

Table 2.

API latency (ms).

5. Discussion

This study proposed a virtual instructor framework enabling the building of new training tools to assist operators in complex operations while facilitating detailed inspections. This way, operators receive guidance, enhancing their well-being.

The implementation of a PoC of the proposed framework helped to validate the proposed framework, demonstrated by a use case to instruct operators equipped with an HMD on PC assembly operations by leveraging the use of MR and CV. AI capacities were supported by DL models in detecting assembly errors.

The latency results from Table 2 suggest that the system has the potential to meet the timing requirements of industrial real-time applications. The primary focus was on validating the overall performance of the system, the integration of modules, and the instructional delivery capabilities. However, to fully assess the instructional effectiveness and user acceptance, future work will include a comprehensive evaluation of the quality of experience (QoE) in real workplace training scenarios. This will involve collecting user feedback regarding usability, cognitive load, perceived usefulness, and overall satisfaction, enabling iterative improvements to enhance the system’s impact on operator training and performance. This evaluation will cover other use cases and provide a more detailed assessment of system performance.

Regarding the adoption of Magic Leap 2, it is acknowledged that its cost may pose a limitation for adoption in industrial environments with more restricted resources. However, it is important to highlight that, for the specific objectives of the proposed system, viable market alternatives with comparable functionalities are scarce. The Microsoft HoloLens 2 stands out as the main alternative, being widely used in industrial contexts and offering a similar Mixed Reality experience, albeit at a comparable cost. Thus, although more affordable Augmented Reality devices exist, they do not offer the necessary MR capabilities to ensure precise spatial integration, robust hand tracking, and reliable overlay of instructions in the physical environment, features that are essential to the effectiveness of the developed framework. The choice of the Magic Leap 2 therefore represents a compromise between technical requirements and commercial availability, being one of the few solutions on the market that balances performance, ergonomics, and support for custom MR development. Moreover, Magic Leap 2 operation battery is limited up to 3.5 h. Finally the use of extended periods causes fatigue for the operators.

Incorporating new practical cases in training and quality control is essential to extend its applicability further. The specific requirements for applying the system to new tasks depend on the intended use case, reflecting the modular and customization nature of the solution. Vocational training projects can be created solely with visual instructions such as text or animations, enabling faster deployment without the need for vision models. More advanced scenarios, such as on-the-job training, can optionally incorporate vision-based models to enhance functionality. For example, task validation models verify correct task execution, while component verification models support setup or picking by visually identifying parts. Each model operates independently and is optional, meaning the system functions properly even if only one model is implemented. Developing these models requires suitable datasets, which can be sourced from existing community repositories or created, which demands extensive annotation. Although advances in meta-learning and few-shot learning offer potential solutions to reduce this effort, their implementation introduces additional challenges. All models were fine-tuned using YOLOv8m, with durations between 16 min and 1 h and 22 min, depending on training parameters, including dataset size and epoch count. Moreover, cloud platforms like Roboflow provide free datasets and credits for cloud training, easing hardware requirements and enabling broad accessibility.

The results demonstrate the suitability of the proposed framework to improve operators’ continuous learning in vocational contexts or on the factory floor.

6. Conclusions

This study bridges the gap in the literature on training solutions for training and monitoring procedural quality by integrating AI and AR. A virtual instructor framework is proposed to improve operators’ performance while reducing errors.

A PoC of the proposed framework helped to demonstrate a use case empowering supervisors to define the assembly steps to be assigned to operations. The built tools as part of the PoC included an HMD for instructing operators to execute the assigned operations. The build tools addressed two aspects of training. The first was vocational training, designed for classroom environments or training centers, facilitating training by interacting with the system. The second one was on-the-job training that incorporates visual validation of each operation. Each step must be completed correctly before moving on to the next. Quality control raises alerts whenever an error occurs, so it can be quickly fixed while avoiding any impact.

In the future, we aim to evaluate the framework’s performance under real training workplace assembly scenarios to assess the quality of experience (QoE) from the users’ standpoint. The proposed framework can also be explored by integrating physiological signals and assessing the level of attention and environmental conditions, such as temperature and light. Furthermore, we intend to extend the system to support real-time quality control, including defect detection and automated inspection.

To overcome the limitations of Magic Leap 2, we expect to evaluate other alternatives in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.S., S.M.O., and J.H.; methodology, J.H.; software, L.S.; validation, J.S. and J.H.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, L.S.; resources, S.M.O.; data curation, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.S.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and A.B.; visualization, L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project GreenAuto: Green Innovation for the Automotive Industry, grant number 02/C05-i01.02/2022.PC644867037-00000013, from the Incentive System to Mobilizing Agendas for Business Innovation, funded by the PRR-Recovery and Resilience Plan from the Portuguese Republic. Furthermore, we thank the Research Centre in Digital Services (CISeD) and the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu for their support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author André Barbosa is employed by the company Inklusion Entertainment. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hashemi-Petroodi, S.E.; Dolgui, A.; Kovalev, S.; Kovalyov, M.Y.; Thevenin, S. Workforce reconfiguration strategies in manufacturing systems: A state of the art. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 6721–6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miqueo, A.; Torralba, M.; Yagüe-Fabra, J.A. Lean Manual Assembly 4.0: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollter Bergman, M.; Berlin, C.; Babapour Chafi, M.; Falck, A.C.; Örtengren, R. Cognitive Ergonomics of Assembly Work from a Job Demands–Resources Perspective: Three Qualitative Case Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, F.K.; Shang, X.; Qiao, L. Augmented reality in vocational training: A systematic review of research and applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, U.; Richter, T.; Krenkel, P. Interdependencies of Industrie 4.0 & lean production systems: A use cases analysis. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmarini, R.; Del Amo, I.F.; Ariansyah, D.; Khan, S.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Roy, R. Fast Augmented Reality Authoring: Fast Creation of AR Step-by-Step Procedures for Maintenance Operations. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 8407–8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. Future of industry 5.0 in society: Human-centric solutions, challenges and prospective research areas. J. Cloud Comput. 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, G.; Karvouniari, A.; Dimitropoulos, N.; Togias, T.; Makris, S. Workplace analysis and design using virtual reality techniques. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikos, G.; Sofianidis, A. What Is the Future of Augmented Reality in Science Teaching and Learning? An Exploratory Study on Primary and Pre-School Teacher Students’ Views. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.M.; Au, K.M.; Lau, H.C.; Ho, G.T.; Wu, C.H. Evaluating the effectiveness of learning design with mixed reality (MR) in higher education. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eswaran, M.; Bahubalendruni, M.V.A.R. Challenges and opportunities on AR/VR technologies for manufacturing systems in the context of industry 4.0: A state of the art review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebol, M.; Hood, C.; Ranniger, C.; Rutenberg, A.; Sikka, N.; Horan, E.M.; Gütl, C.; Pietroszek, K. Remote Assistance with Mixed Reality for Procedural Tasks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Lisbon, Portugal, 27 March–1 April 2021; pp. 653–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.T. A survey of augmented reality. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1997, 6, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, B.; Kurian, J.; Fitzgerald, R.; Goh, D. Students’ Learning Experience in a Mixed Reality Environment: Drivers and Barriers. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2022, 50, 510–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, M.; Wolff, S.J. Convolutional Neural Network applications in additive manufacturing: A review. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2022, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Lee, K.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Shin, Y.-S. Deep learning-based visual inspection system for surface defect detection in manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Zamil, M.; Rayed, M.; Kabir, M.; Mridha, M.; Nishimura, S.; Shin, J. A Survey of Computer Vision Algorithms for Manufacturing Quality Control. IEEE Access 2024, 9, 121449–121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, R.; Hsu, C.; Band, S. A systematic review of deep learning approaches for surface defect detection in industrial applications. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, M.; Teixeira, M.; Rodrigues, É.; Casanova, D. Deep Learning Models for Visual Inspection on Automotive Assembling Line. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020, 3, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, P.; Fauser, M.; Sattlegger, D.; Steger, C. MVTec AD–A Comprehensive Real-World Dataset for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9592–9600. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, W.; Peng, Z.; Wang, H. A Survey of Vision-Based Methods for Surface Defects’ Detection and Classification in Steel Products. Informatics 2024, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMW Group. Artificial Intelligence Improves Quality Assurance at BMW Group Plants. 2020. Available online: https://www.press.bmwgroup.com/global/article/detail/T0449729EN/artificial-intelligence-as-a-quality-booster (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Silva, J.; Coelho, P.; Saraiva, L.; Vaz, P.; Martins, P.; López-Rivero, A. Validating the Use of Smart Glasses in Industrial Quality Control: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog, M.D.; Bardeen, L. Ford Brings Microsoft HoloLens to Design Studio; Drives Speed, Creativity and Collaboration. 2017. Available online: https://blogs.windows.com/devices/2017/09/20/ford-brings-microsoft-hololens-to-design-studio-drives-speed-creativity-and-collaboration/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Nogueira, P.A.L. Aplicação da Realidade Mista na Aprendizagem em Unidades Industriais-Learning Factory. Master’s Thesis, Polytechnic Institute of Viseu, Viseu, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Unity Technologies. Plataforma de Desenvolvimento em Tempo Real do Unity | Engine para 3D, 2D, VR e AR. 2024. Available online: https://unity.com (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Epic Games, Inc. Unreal Engine | A Mais Poderosa Ferramenta de 3D em Tempo Real. 2023. Available online: https://www.unrealengine.com/pt-BR (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Porsche. Designed by Innovation. 2019. Available online: https://newsroom.porsche.com/en/2019/digital/porsche-design-mixed-reality-technology-meyle-mueller-medialesson-hololens-interview-18189.html (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Team Viewer. TeamViewer Customer Success Story: Audi. 2022. Available online: https://www.teamviewer.com/en/success-stories/audi/ (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Chivukula, K. RAAF Uses HoloLens Mixed-Reality Device for C-17A Maintenance. 2020. Available online: https://www.airforce-technology.com/news/raaf-uses-hololens-mixed-reality-device-for-c-17a-maintenance/ (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- Trimble Inc. Laing O’Rourke - Connect AR - Customer Study. Trimble Case Study. 2023. Available online: https://fieldtech.trimble.com/resources/mixed-reality/laing-orourke-connect-ar-customer-study (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Yang, R.; Li, C.; Tu, P.; Ahmed, A.; Ji, T.; Chen, X. Development and Application of Digital Maxillofacial Surgery System Based on Mixed Reality Technology. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 719985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy, S. Siemens Uses Microsoft Teams and HoloLens for Energy Solutions. 2023. Available online: https://www.uctoday.com/unified-communications/siemens-uses-microsoft-teams-and-hololens-for-energy-solutions/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Honeywell. Honeywell Introduces Virtual Reality-Based Simulator To Optimize Training For Industrial Workers. 2020. Available online: https://www.honeywell.com/us/en/press/2020/10/honeywell-introduces-virtual-reality-based-simulator-to-optimize-training-for-industrial-workers (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Agenda Green Auto. Agenda Green Auto-Inovação Verde para a Indústria Automóvel. Available online: https://www.agendagreenauto.pt/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Saravanakumar, D.; Mohan, B.; Muthuramalingam, T. A review on recent research trends in servo pneumatic positioning systems. Precis. Eng. 2017, 49, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Django. Django. 2024. Available online: https://www.djangoproject.com/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Magic Leap. Product Specifications. 2024. Available online: https://www.magicleap.care/hc/en-us/articles/7813913215373-Product-Specifications (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov8 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Ultralytics. Ultralytics | Revolucionando o Mundo da IA de Visão, 2025. Available online: https://www.ultralytics.com/pt (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ultralytics. YOLOv3. 2023. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov3 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ultralytics. Predict. 2024. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/predict (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Blender, F. blender.org-Home of the Blender Project-Free and Open 3D Creation Software. 2024. Available online: https://www.blender.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Khronos Group. glTF-Runtime 3D Asset Delivery. 2020. Available online: https://www.khronos.org/gltf/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Brigsted, T. Siccity/GLTFUtility. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/Siccity/GLTFUtility (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Newtonsoft. Json.NET-Newtonsoft. 2024. Available online: https://www.newtonsoft.com/json (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- A, A.H.M. Create REST API Using Django REST Framework | Django REST Framework Tutorial. 2023. Available online: https://medium.com/@ahmalopers703/getting-started-with-django-rest-api-for-beginners-9c121a2ce0d3 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Christie, T. Home-Django REST Framework. 2024. Available online: https://www.django-rest-framework.org/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Kinsta. O Que é MySQL? Uma Explicação Simples para Quem Está Começando. 2022. Available online: https://kinsta.com/pt/base-de-conhecimento/o-que-e-mysql/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).