Abstract

Accessible tourism has become relevant, generating significant economic and social impacts. Even though the accessible tourism market is rising and presents an excellent business opportunity, this market is largely ignored, as it is challenging to stimulate the flow of accessibility information. Accessible technologies, such as tourism information systems, can be a potential solution, increasing accessibility through communication. However, these solutions are few and tend to fail the integration of users upon development processes. This research aims to present a technological platform to improve accessibility in the tourism industry. The name of this accessible and adaptable technological solution is access@tour by action, and it was created following a user-centered design methodology. This development involved a requirement engineering process based on three crucial stakeholders in accessible tourism: educational institutions, supply agents, and demand agents. The design phase was achieved with the help of a conceptual model based on a unified modeling language. The initial prototype of the solution, created in Adobe XD, implements a wide range of informational and accessibility requirements. Some access@tour by action interfaces outline the design, content, and primary functionalities. By linking technological development, tourism, and social inclusion components, this study highlights the relevance and interdisciplinarity of processes in developing accessible information systems.

1. Introduction

Technology is changing the tourism industry with the daily emergence of digital trends. However, the adoption of technological solutions presents both advantages and challenges for the tourism sector [1]. A significant challenge emerging is how new technologies can improve the social inclusion of people with special needs (PwSNs), including people with disabilities [2]. Accessible tourism is crucial for developing a more inclusive society, focusing on creating conditions so everyone, including PwSNs, can enjoy tourism experiences [3]. Technology should be at the service of society, so integrating accessibility into diverse technologies is an excellent example. Tourism enriches people in many dimensions. However, it is difficult for visitors with disabilities to travel due to the several constraints that they face [4]. Often, people with physical/cognitive disabilities become unable to travel due to barriers [5] that are not only related to physical space but also to lack of information and defective communication [6]. Moreover, the information about accessibility conditions in tourism offers must reach PwSNs and be in a format that can be consulted by these users [7]. Otherwise, the availability of information holds no practical value. For that reason, this work was built on the basis that accessible tourism must consider two components: physical and digital accessibilities [1,3,8,9,10,11]. Besides this, there are diverse accessible tourism stakeholders [12,13,14] involved in creating accessible tourism conditions. As it can be challenging to address the diverse requirements of PwSNs [15], all elements in the accessible tourism market must develop joint strategies (involving technology) to promote tourism activities accessible to PwSNs [16].

As the accessible tourism market expands and its potential increases, information and communication technology (ICT) can serve as an excellent means to leverage this growth. The effectiveness of technology hinges on how well it meets the needs of its users [17]. Hence, it is imperative to study how information exchange should be treated. This interaction is mainly determined by the inputs and outputs traded between the users and the technology solution [18]. In addition, it is essential to ensure that the system in this area can serve as a technological solution to address accessibility challenges in tourism.

The use of information systems may represent a solution for improving the circulation of access conditions to the practice of tourism, as they facilitate access to different tourism activities [10], thus combating the social exclusion of PwSNs. This technological solution not only enhances tourism experiences for anyone, regardless of their degree of need or disability, but also ensures greater value to the customer, helping their social integration [19,20]. Despite the benefits that come from the use of this type of technology, currently, there is still an evident lack of platforms [21,22] oriented to the promotion of accessible tourism, as demonstrated in the studies by Teixeira et al. [23] and Alves et al. [24]. As such, this paper intends to address this gap by presenting a prototype of a Web-Based Information System (WBIS), designated access@tour by action, capable of mediating information needs in accessible tourism. The developed solution functions as a technological platform, acting as a communication tool between offer/supply and a training tool within accessible tourism. The innovation associated with this work is not only related to applying information technology to a peculiar area (accessible tourism) but also to the incorporation of the contributions of different stakeholders: (i) demand agents (PwSNs, social organizations, and informal caregivers), (ii) supply agents (accommodation units, museums and monuments units, transport and tourism animation enterprises, intermediaries–travel agents and tour operators, and public organizations with responsibility in the sector), and (iii) education institutions (e.g., universities and higher education institutions responsible for training in tourism).

To obtain the access@tour by action, a user-centered design (UCD) methodology was applied based on previous validated methodology works in different research areas [25,26,27]. The development began by retrieving the main requirements from the different stakeholders with the help of different data-gathering methods. Afterward, the requirements were converted into system functionalities. This process was followed by obtaining a conceptual model based on the gathered requirements and using Unified Modeling Language (UML) to understand the user interaction better. Then, a reflection is carried out on obtaining the prototype, particularly addressing testing procedures. Afterward, a prototype is presented in Adobe XD. The prototype combines accessibility features with all the necessary information flows needed to support accessible tourism. With the intention of illustrating some functionalities, the prototype interfaces are shown with screenshots. Then, a discussion is provided on the innovation of access@tour by action, comparing utilities with existing accessible tourism platforms. Finally, the paper ends with the main contributions, discusses some minor limitations, and addresses future work.

2. Background

2.1. Tourism and Accessibility

The concept of accessibility in tourism refers to the various methods, tools, or approaches that make environments, products, services, and information available and usable by all people, including those with disabilities or impairments [3,9]. It ensures that everyone, regardless of eventual specific needs, can access and use the intended resources effectively [1,8,28]. Accessible tourism aims for a more inclusive society [29], improving accessibility conditions in tourism, especially for people who suffer from some type of disability (physical, hearing, intellectual, visual) or have some special needs [30]. Lately, this concept has gained special attention with the rising global tourism market [31] and the last disability world report indicating that 15% of the world’s population lives with a disability [32]. The importance of the accessible tourism market is increasing not only due to social responsibility concerns but also because of increasing business opportunities [33,34,35]. Besides this, it is crucial to understand that accessible tourism with the integration of diverse PwSNs [36] depicts a complex scenario regarding accessibility requirements. Different requirements translate into a wide range of attributes in terms of accessibility conditions [37,38] that need to be ensured [6]. A possible solution to address this inherent complexity is to consider the role of caregivers. These caregivers can be formal, such as social organizations that provide support to PwSNs, or informal (family, friends) [31] and are often responsible for searching for accessible tourism offers for PwSNs [39]. Only by looking at the demand from different perspectives will it be possible to reach truly accessible solutions in tourism.

Establishing accessibility conditions in tourism has been gaining some prominence [7]. However, some barriers to accessibility still exist, preventing the full realization of accessible tourism [5,40,41]. Physical barriers (e.g., architectural and lack of support materials) [42] and communication/informational barriers (e.g., lack of braille signage, absence of audio guides for blind users, unavailability of sign language interpretation, lack of human skills in communication) [43] create “obstacles” that threaten the ability and independence to realize tourism activities [6,44]. While guaranteeing these accessibility conditions is essential, access to the correct type of information remains the primary factor in tourism environments [45,46]. The information about accessibility allows PwSNs to perceive if their requirements can be taken into account during the planning of a tourism trip and during the tourist experiences, as well as if all the conditions for tourism are met without any constraint [47]. On the other hand, the accessibility of information ensures that all information is available to those who need it without any loss of value [48]. It is precisely in the interplay between these two aspects that the role of ICTs becomes relevant, assuming primary importance as tools that promote accessible tourism [49], as it enables exchanging information within the accessible tourism market.

In that sense, if we hope to build integrated solutions that contribute to establishing accessible tourism conditions, it is crucial to be aware of the needs of PwSNs and caregivers and look at the other sides of the spectrum of the accessible tourism market [50]. Firstly, we ought to look at the role of tourism supply agents, such as accommodation units, monuments, and museums [16]. These supply agents are responsible for creating and sharing tourism offers. Therefore, these users are responsible for providing all information regarding accessibility conditions. Despite having this kind of information, it is challenging to reach their intended target audience (PwSNs) [23,51]. Hence, it is essential to create pathways that improve the communication between demand and supply regarding accessible tourism.

On the other hand, one must not forget how to ensure accessibility conditions in tourism services. The negative attitudes of staff towards PwSNs represent another significant obstacle in terms of information provision [52]. To address this negative factor, some authors [53,54] have highlighted the importance of training related to accessible tourism. Tourism staff must receive training to understand the accessibility and information needs of PwSNs and provide them with the best possible tourism experience [28]. Teachers and students of tourism courses should disseminate the training required to ensure accessibility conditions in tourism. For this reason, education institutions and other training institutions play a crucial role in improving specialized teaching programs to address the requirements of the accessible tourism market [14]. If tourism hopes to build accessibility solutions that share information, it is pivotal to integrate entities (students and teachers) of institutions that are responsible for providing training in tourism during the conceptualization and building phases.

2.2. Accessible Tourism Information Systems

It should be noted that ICTs could be very useful in accessibility contexts [55]. For instance, technologies associated with location systems are crucial for creating accessible geographic databases [56]. Furthermore, mobile technology applications can present mechanisms and collaborative features [57]. In summary, ICTs emphasize not only the technological aspects of information dissemination but also the means to facilitate access to the digital world, particularly through assistive and adaptive technologies [58]. The context of accessible tourism is no exception. Some practical instances of utilizing ICTs in accessible tourism are the support in visiting monuments and museums, as demonstrated in the research conducted by Angkananon et al. [59], Haworth and Williams [60], and Ivanov et al. [61].

To increase accessible tourism conditions, the particular requirements [62] of diverse visitors with special needs (e.g., vision, hearing mobility, cognitive/intellectual, allergies, and heart problems) [1] should be taken into consideration by the responsible supply agents [4,28,63,64]. Considering the aim of establishing such a gateway, information technologies can pave the way for success. This is tied to the significance of information in accessible environments [10]. In the case of tourism, trip planning is conducted with significantly greater detail by PwSNs [65] since the more significant the accessibility requirements, the greater the requirements for detailed information [13]. Besides this, the tourism platforms’ interfaces are connected to Human–Computer interaction and have been examined as a key challenge [42]. This is because information should be provided in an accessible way so that PwSNs can understand its content [66,67]. Although digitalization enables access to tourism information, accessibility barriers still exist [68]. To overcome barriers and integrate the views of several stakeholders, information systems can serve as potential solutions, as outlined in a study by Michopoulou and Buhalis [69]. Essentially, information systems serve as technological solutions designed to assist PwSNs [49] by delivering the appropriate information at the right moment and in a suitable format [70].

The creation and design of information systems within specific accessibility environments (tourism) and users (PwSNs) presents a significant challenge [71,72]. It is necessary to have a deep knowledge of the accessibility tourism market to gather the correct user requirements, which can be divided into two types: functional and non-functional. Functional requirements can be described as functional requirements that specify what the system can accomplish, whereas non-functional requirements outline how these functional requirements should be implemented [73]. In the case of developing information systems for PwSNs, non-functional requirements are crucial, mainly because they include accessibility requirements [74].

There have been attempts to introduce accessibility in software development, especially with the creation of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAGs) [75], which consist of a set of validated guidelines that web developers should follow in order to ensure technology is accessible to all [76]. Despite the existence of valid standards, such as WCAGs, accessibility is still a lacking aspect across software development [77]. This was observed in earlier research from various fields, such as education [25], tourism [26], and healthcare [27], where new methodological approaches had to be created to meet specific accessibility needs. The solution to address the specific and diverse requirements was to place the focus on users. This is true in the accessible tourism market, where PwSNs and other stakeholders have distinct and specific requirements [78]. Different authors [79,80,81] indicated that lacking human perspective during development phases can lead to design faults and failed implementation processes [82]. Thus, it is recommended to follow UCD [83] and iterative [84] approaches, making systems more “usable” and accessible by focusing on the specific requirements of users [85]. However, there is a gap in current platforms regarding the users’ integration and placement of accessibility requirements at the heart of system development. This is verified in the few existing accessible tourism platforms (e.g., Tourism for All [86]; Hands to discover [87]; Euans [88]; Travability [89]; Tourismus für Alle Deutschland [90]; Tur4All [91]). Most of them clearly fail this integration, as demonstrated in a study comparing the diverse platforms performed beforehand and reported by Alves et al. [24]. Since technological platforms are ideal for disseminating information, and information is a critical aspect of tourism, there is a clear justification for using them to promote tourism for all since, as in any other field, information is the key to success. However, users must be involved in methodology processes because only then will a solution be truly accessible and cater to their requirements.

3. Materials and Methods

To accomplish more accessible tourism conditions, it is necessary to provide accessibility information and ensure that this information reaches PwSNs in an accessible manner. In fact, the greater the accessibility requirements, the greater the need for detailed information about those requirements [92]. This study aims to solve the problems arising from the abovementioned context, proposing the technological platform access@tour by action, which can mediate the information requirements of demand and supply agents in accessible tourism. The significance of this study is determined by the absence of platforms that specifically address these needs, especially regarding accessibility requirements. More specifically, solutions should allow integration and interaction between the various stakeholders involved in the value chain to promote the accessibility conditions of tourism destinations. The access@tour by action aims to serve as an informative platform that promotes communication sharing among stakeholders in accessible tourism. It is expected that a solution of this nature can help in the development of accessible tourism conditions, as it enables access, in an accessible way, to share information about the accessibility of destinations. This allows PwSNs to find tourism solutions that are adapted to their needs and/or disabilities. In addition, the access@tour by action intends to allow the sharing of several tourism offers (e.g., hotels, museums, and outdoor activities) within an accessibility context. Thus, it represents an excellent opportunity to interact with an up-and-coming market, reaching potential customers through disseminating accessible tourism offers on a dedicated platform for this purpose. Integration of educational institutions is also valuable, as disseminating research and training programs can create awareness for accessible tourism topics in academic communities. Finally, it also should be noted that the objective is for the platform to be self-sufficient, meaning that the users are responsible for inserting and retrieving information.

3.1. Methodology and Conceptualizing Phases

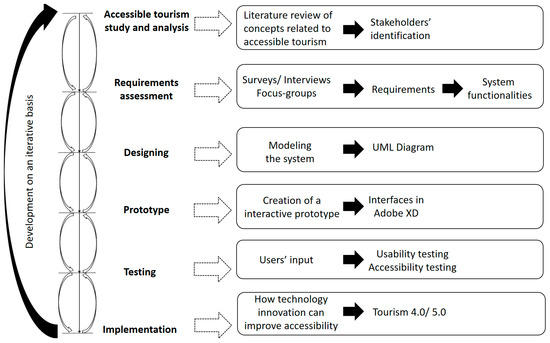

The conceptualization and building process of the access@tour by action follows a defined methodological approach (Figure 1). Earlier methodological studies inspired this development process, which was carried out in various areas of information systems [25,26,27], following a UCD methodology with six development stages.

Figure 1.

The methodology used for conceptualizing the access@tour by action platform.

The first stage aimed to study the environment encompassing the accessible tourism market. The analysis of complex factors in accessible tourism allowed us to understand the main accessibility problems related to the architecture of accessible solutions and what should be considered the main stakeholders. For the reasons found and outlined in the accessible tourism literature [1,16,50,54], an agreement was reached in terms of grouping stakeholders in the mentioned groups: (i) demand agents (users looking for accessible tourism offers: PwSNs, social organizations that provide support to PwSNs, and informal caregivers), (ii) supply agents (users looking to insert offers related to accessible tourism: e.g., hotels, museums, …), and (iii) education institutions (tourism teachers and tourism students wanting to gain knowledge in accessible tourism).

The second stage focuses on retrieving the main requirements for building the platform. Different methods were necessary to gather the needs/requirements of demand agents, supply agents, and education institutions. Essentially, three data-gathering methods were applied: surveys, interviews, and focus groups. It is important to note that the data gathering was obtained from a sample of accessible tourism stakeholders in Portugal. A summary of the work involved and a complete description of the techniques used to obtain user requirements have already been published in diverse academic works [16,54,93]. These studies include the requirement assessment process of demand agents from Teixeira et al. [93], supply agents from Alves et al. [16], and education institutions from Teixeira et al. [54]. A summary of the data-gathering process is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Requirements gathering process.

After applying the data-gathering methods, the obtained requirements were converted into system functionalities. These functionalities are the range of system functions that determine what the system should perform and how to execute them [73]. This includes usability and communication requirements, which primarily relate to accessibility.

The system modeling aimed to organize the collected functionalities logically and coherently. UML notation was chosen to create the models to understand sequences of information, given that it has frequently been considered a language for defining, displaying, and creating information technologies [94]. The system modeling aims to organize the available information in a logical and coherent manner, demonstrating how the flow of information should proceed. Essentially, conceptualizing the solution as a class diagram allows for transmitting a better idea of the capabilities and functionalities of the intended technological platform. The class diagram was developed using the Visual Paradigm software version 16.2. After designing the solution in UML, the elaborated model must be evaluated before being translated into a prototype. Thus, the model was reviewed by experts in the areas of tourism, accessibility, and information systems. A focus group session with nine experts in tourism and accessibility was conducted to present the models and gather some input. During the discussion panel, some functionalities were better explained and corrected. It is essential to point out that, since UML diagrams represent abstract models, their comprehension can sometimes be challenging.

After validating the model, the prototype was developed. The prototype was created using Adobe XD. The software selection is related to the fact that interactive prototypes can be easily shared with the team and potential stakeholders, facilitating the user experience and user interaction. Moreover, the software also grants the integration of accessibility factors to a certain extent.

The final two stages are the testing and the implementation of the platform. The platform needs to be validated before making its way to the market. Therefore, conducting a set of acceptance tests, namely, usability tests with the different types of potential users, is essential. The results of the tests will allow for correcting simple and complex mistakes and analyzing other potential functionalities. Finally, in the implementation phase, the best way to insert the platform into the market must be examined, alongside the integration with other innovative technologies promoting accessibility. The way to implement the access@tour by action should also address the impacts that Tourism 4.0 or even Tourism 5.0 [95] can bring in terms of improving accessibility, not only in terms of technology innovation but also sustainability enhancement. A more detailed description of the methodological process to develop the access@tour by action can be consulted on a previously elaborated study reported by Teixeira et al. [50].

3.2. Conceptual Model of the access@tour by Action

From a functional standpoint, the platform seeks to facilitate the sharing and exchange of information among the relevant stakeholders by enabling user-platform interaction through various outputs (retrieving information from the platform) and inputs (entering information into the platform). These can be considered the main functionalities of access@tour by action and were identified based on the results of the questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups. The list of functional requirements per stakeholder is available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Functional requirements of access@tour by action.

Demand agents plan to utilize the platform to seek tourism offerings that meet their specific needs and contribute to making these offers even more accessible to everyone. Conversely, supply agents aim to use the platform to promote their accessible offerings and connect with individuals experienced in accessible tourism. Lastly, educational institutions can leverage the application for academic research purposes (more oriented to tourism teachers) or to search for job offers in accessible tourism (more oriented to tourism students), consequently obtaining a better understanding of accessible tourism. It is interesting to note that some stakeholders have one requirement as input, but a distinct stakeholder could have the exact requirement as output. A clear example is the accessible tourism offers, which are inserted into the platform by supply agents but are searched by demand agents.

After describing the functionalities, the system can start to materialize. Notwithstanding, to continue to follow a UCD development procedure, it is essential to view the proposed platform as a solution to a real-world issue. Hence, it was necessary to implement a representation method within a real-life context. For this representation, platform models can be created to verify how the previously collected requirements can be transcribed and provide origin to an actual information system. The model should embody the system by allowing the incorporation of new components and staging the development of the intended incremental solution together with the evolutionary design. The main goal is to illustrate sequences of information, enabling potential developers to understand all potential interactions between users and the system.

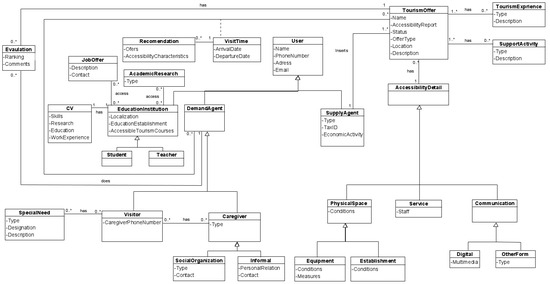

Geared towards describing the different components that make up the system, a class diagram was developed based on the collected functional requirements for each stakeholder. This UML class diagram is represented in Figure 2 and depicts the technological platform in a static-type phase. That is, regardless of the time factor, the diagram always remains the same. The class diagram [96] consists of diverse classes. A class is a description (meta-information) that defines characteristics and behavior shared by a group of objects. An object is an instance (materialization) of the class. There are depicted attributes in each class, which are described as the properties of each class. There are also relationships between the classes, viewed as connections between objects in the various classes. The diagram frequently features aggregation relationships, breaking down more complex classes into simpler ones and establishing a hierarchical structure. For this reason, the class ‘User’ can be divided into three other classes: ‘SupplyAgent’, ‘DemandAgent’, and ‘EducationInstitution’. There are, however, two classes that are associated with more than one user. It is the case of the own class ‘User’ (representing a general user before registering into the platform and becoming a specific stakeholder) and ‘TourismOffer’ (can be interacted with by the classes ‘DemandAgent’ and the ‘SupplyAgent’).

Figure 2.

UML class diagram of the access@tour by action.

The class ‘SupplyAgent’ (e.g., accommodation units, bars, restaurants, tourist entertainment companies, and tourism attractions) will be responsible for placing the ‘TourismOffer’ on the platform. This ‘TourismOffer’ can take various forms (e.g., accommodation and cultural attractions (museums/monuments/theme parks)). For these reasons, it should be indicated if there is some type of ‘TourismExperience’ associated with it. For each ‘TourismOffer’, it is crucial to describe not only the provided ‘SupportService’ but also the accessibility conditions, with ‘AccessibilityDetails’, which can be divided into ‘PhysicalSpace’ (equipment and the establishments themselves), ‘Service’ (conditions of the existing support staff), and ‘Communication’ (forms of communication and the skills of human resources).

The class ‘DemandAgent’ can essentially be a ‘Visitor’ or a ‘Caregiver’. The ‘Visitor’ refers essentially to PwSNs (tourists or excursionists) that look for accessible tourism offers (‘TourismOffer’). The ‘Caregiver’ can also carry out this search procedure. That says, the ‘Caregiver’ can be responsible for searching tourism offers on behalf of PwSNs and can be a ‘SocialOrganization’ or ‘Informal’ (family member or friend). The ‘Visitor’ may have none or more than one ‘Caregiver’ associated with them. The ‘Visitor’ can also have none or more than one type of ‘SpecialNeed’. The information on the type, designation, and description will be essential for interacting with the system. While the ‘Visitor’ is enjoying a ‘TourismOffer’, a ‘VisitTime’ will be created (indicating start date and end date), which will be used for the system to communicate with the ‘Visitor’ and provide recommendations in real-time and based on their location, such as other types of offers that may be of interest, according to accessibility conditions. The class ‘Visitor’ can evaluate the ‘TourismOffer’. This evaluation is important for the responsible ‘SupplyAgent’ to identify potential improvements that could enhance the accessibility of the ‘TourismOffer’.

The interaction of the class ‘EducationInstitution’ with the system is quite simple. Essentially, classes ‘Student’ and ‘Teacher’ can access ‘AcademicResearch’ and ‘JobOffer’, both related to accessible tourism. In addition, this class should insert the curriculum vitae–class ‘CV’, with all the relevant information regarding studying and work components.

3.3. Reflecting on the Process to Obtain Prototype: Testing Procedure

Following up on the UCD methodology, the prototype was submitted to a testing procedure. The testing phase was a crucial step in assessing if the prototype corresponds to users’ expectations, although involving users, particularly PwSNs, in the design process is technically complex. Therefore, it was necessary to apply an innovative mixed-method testing approach that incorporated usability principles, such as predictability, consistency, customizability, responsiveness, and crucially, accessibility. Therefore, the testing process had to be meticulously planned. A two-stage testing procedure proved to be a viable solution, as it facilitated the integration of accessibility by addressing significant design flaws. The main objective was to detect errors and accessibility problems before the prototype reached the stakeholders.

In the first stage, experts (academics) with research in tourism and accessibility participated in think-aloud sessions to evaluate the prototype and check the content (e.g., type of information provided and identification of accessibility errors). This helped identify major faults in terms of content, usability, and accessibility and correct them. Some identified flaws in the platform included mistakes in language, lack of content, and lack of simplicity in information delivery processes. The second stage was dedicated to tests with potential end-users: PwSNs, social organizations, informal caregivers, tourism supply agents, as well as tourism students and teachers. The different types of users needed to interact with the web application to correctly evaluate the prototype. Thus, in this phase, usability and accessibility were assessed by applying empirical methods through task performance and a questionnaire. The focus will be on testing aspects, such as ease of interaction and appearance, but also on understanding if the content/information of the application is relevant. For task performance, we evaluated different metrics, such as time and completion rate. The questionnaire consisted of 33 affirmation items that evaluated usability and accessibility factors on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1—completely disagree to 5—completely agree).

By conducting this series of tests, feedback was obtained regarding the importance of the features and information in the access@tour by action and identifying new features. The testing results were presented in a previously performed study and were fully disclosed in Teixeira et al. [97]. In summary, the obtained results demonstrated that: (i) the prototype has the correct information, (ii) information is delivered in an accessible way, (iii) the prototype was considered accessible and simple to work with, and (iv) users intend to use the solution it in the future, as it was considered it offers significant contributions for accessible tourism. Nevertheless, some feedback was retrieved, and the prototype was improved. According to the users, some processes could be simplified, such as evaluating tourism offers and the registration procedure. Users also considered that the reading sequence was sometimes complex due to the large quantity of information in some interfaces. Thus, it was possible to collect a list of some improvements that were properly added to the solution. The version of the prototype presented in this work already includes the implementation of user feedback, as well as the identified needed corrections.

3.4. Prototyping the Functionalities of the access@tour by Action

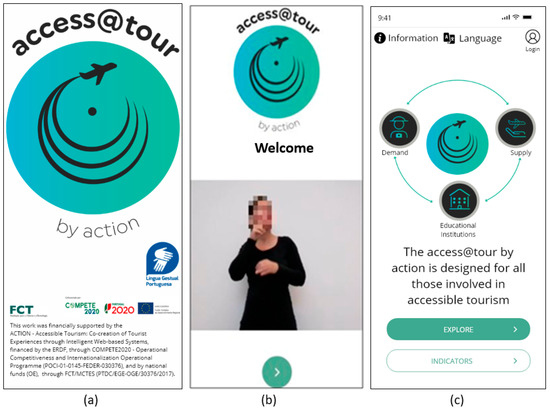

To showcase some functionalities, the following section includes screenshots of the interfaces available in the access@tour by action prototype. The objective is to provide an overview of the developed technological platform by demonstrating the functionalities available to the different users. Due to connectivity factors, the access@tour by action was designed as a mobile technology application. As previously discussed, the platform aims to disseminate information, stimulate communication among all actors involved in co-creating tourism experiences, and help provide and promote personalized tourism products. This system was built to be dynamic and contribute to eliminating travel constraints, improving the workers’ skills, improving the accessibility of the tourism products offered, and providing overall access to accessibility-related information. Besides the explored functionalities available to the users, it was necessary to pay special attention to components related to accessibility assurance, which can be understood as non-functional requirements. Thus, research was conducted to identify accessibility requirements. The starting point was WCAG 2.1 [75], but different sources were used to determine accessibility components. The identification of the accessibility requirements is thoroughly detailed in previously elaborated studies, including systematic literature reviews [23,79], tourism website analysis [98], and concurrent platforms analysis [24]. In summary, there are five main accessibility characteristics of access@tour by action that focus on providing accessibility: (i) the availability of alternatives to content that includes text, videos, and images, (ii) an easy-to-use navigation system, (iii) content displayed in a clear and comprehensible format, (iv) a user-friendly layout, and (v) compatibility with assistive technology.

To truly provide an accessible experience, the platform also has a range of specific capabilities. Once opened, the platform greets the users and explains functionalities with a video containing sign language. In addition, there are options available to change the size and font of the text. The platform also provides input assistance when input from the users is needed, presenting relevant labels and instructions. Finally, access@tour by action was designed to offer simple and intuitive content, which can be navigated through voice controls, ensuring a genuinely accessible solution.

The first interfaces of the platform are shown in Figure 3. Essentially, the platform offers an introduction in video format with sign language support. Afterward, three paths are available based on the type of user: (i) demand agents (users that search for accessible tourism offers), (ii) supply agents (users that add tourism offers/products to the system), and (iii) education institution (users that use the platform to collect accessible tourism information related to training and academic research). After selecting a navigation path, the user will have access to the respective functionalities. In a subsequent phase, the goal will be to establish an identification system that automatically directs the user to a designated starting page.

Figure 3.

Interfaces of the initial screens of access@tour by action. From left to right: (a) the loading interface, (b) the welcoming interface with sign language support, and (c) type of user selection.

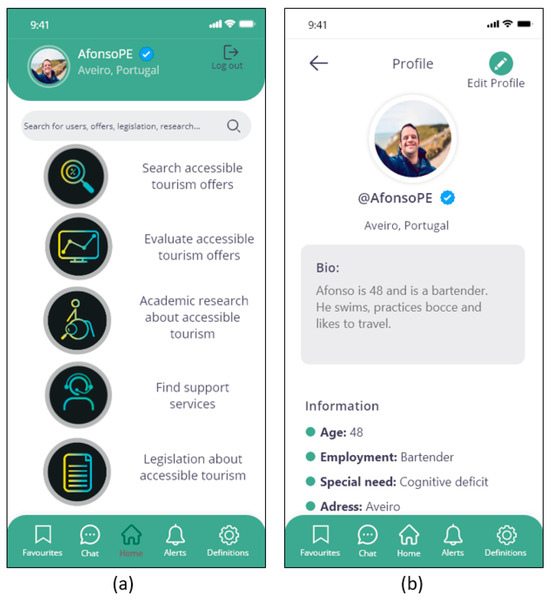

3.4.1. Functionalities for the Demand Agent

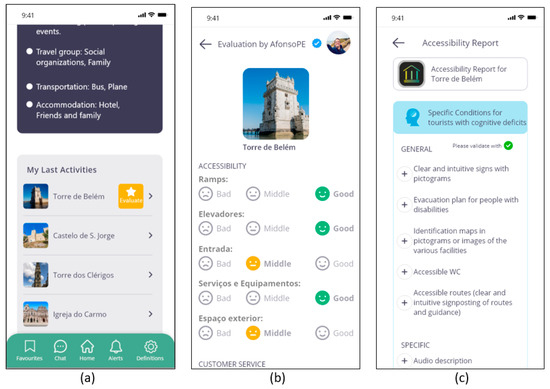

For demand agents (PwSNs, social organizations, and informal caregivers), there are various potential interactions with the platform. Users can utilize the platform to search for accessible tourism products, assess the tourism products/offers they have consumed or obtained, explore studies related to accessible tourism, discover tourism support activities, and research legislation regarding accessible tourism. In addition, a toolbar is available to users to link them with other interfaces on the system. These links include accessing the favorite tourism offers saved page, a chat interface for interacting with other users, a notification alert page, access to essential system definitions, and a Home button that allows users to swiftly return to their homepage. Additionally, at the top of the interface is a search bar for exploring various aspects of the system using keywords. The user can also access the user profile through the definition or simply clicking on the user profile image. The user profile provides an overview of the accessibility needs of the tourists and also their latest tourism experiences. The user previously inserted this information into the system so it could be stored. The interfaces demonstrating the homepage of a demand agent and a user profile are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Interfaces representing the different interactions a demand agent can have with the platform and the user profile. From left to right: (a) the demand agent homepage, and (b) the user profile.

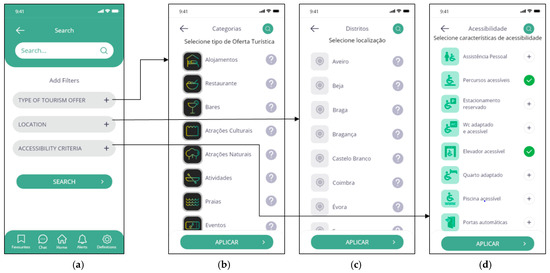

The selection of tourism products is one of the main functionalities. The user can indicate the type of tourism product, location, and accessibility criteria. The objective is for tourists to have the possibility to search for particular types of tourism activities that can fulfill their accessibility criteria. The platform was also built with the aim of being smart and adaptive, so when a tourist inserts personal information into the platform, the system is capable of recognizing those needs and offering already filtered content by automatically assimilating information regarding the users’ profile. The interfaces related to the search for tourism offers are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Interfaces to search for tourism offers. From left to right: (a) search filter, (b) type of offer, (c) location, and (d) accessibility criteria.

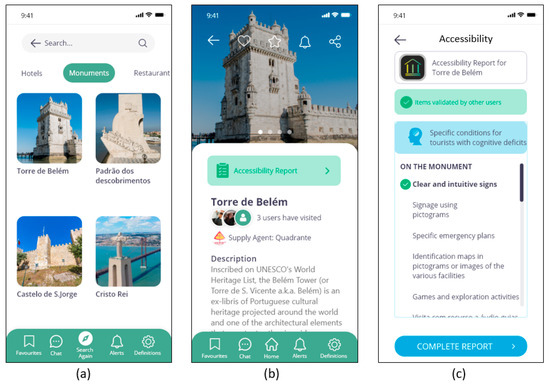

Once the search is completed, the results are presented according to the type of tourism activity. Figure 6 intends to illustrate the simulation of searching for a cultural attraction, namely a monument. After selecting the intended offer, a specific page offering more information is shown. This page includes a detailed description, location, and detailed comments from other users. Since accessibility is the primary concern, an accessibility report is included on every offer page. This accessibility report intends to be an in-depth presentation of all accessibility features available in the tourism offer for different types of PwSNs. Supply agents insert this information by filling out a form that will generate the accessibility requirements. Later, actual users can validate the information available in the report. The validated information is marked differently.

Figure 6.

Interfaces resulting from a search. From left to right: (a) the interfaces of the result of a search, (b) the page of a monument, and (c) the respective accessibility report.

The evaluation of accessible tourism offers was made a simple process for visitors. To start the evaluation process, it is necessary to select which offer it is intended to evaluate. Subsequently, the user must fill out a simple form regarding the evaluation of accessibility standards, service, and communication. Simple comments can also be inserted. Another important aspect is the confirmation of the detailed information available in the accessibility reports. The tourists can confirm every accessibility detail so that a security sensation can be transmitted to other users. Once the process is completed (Figure 7), noteworthy information for supply agents can be retrieved through these evaluation forms, especially regarding accessibility issues.

Figure 7.

Interfaces representing the evaluation procedure. From left to right: (a) select the offer to evaluate, (b) evaluation form, and (c) accessibility report validation.

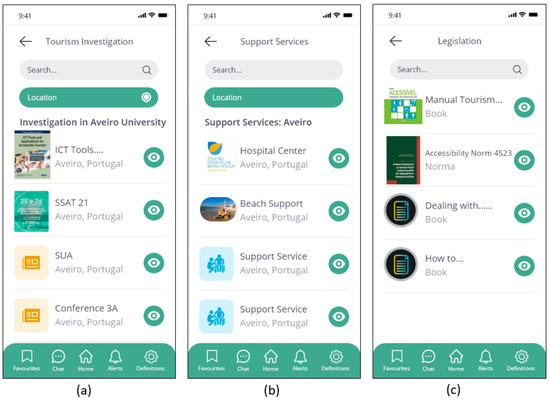

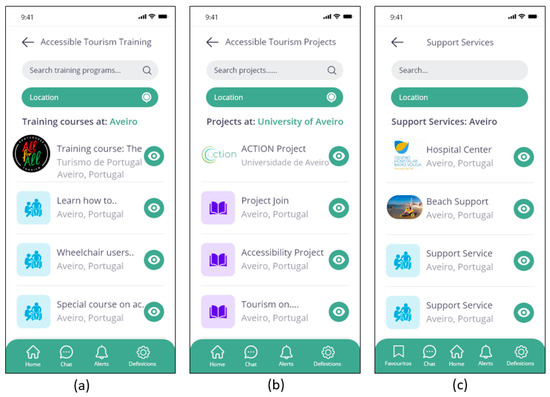

Finally, the system also allows the search for investigation and support activities legislation regarding accessible tourism (Figure 8). Investigation topics are mainly related to books and conferences related to accessible tourism. Support services address the need for specific equipment (e.g., wheelchairs, audio guides) and medical care (clinic in case of emergency). During data gathering procedures, the legislation was pointed out as an important concern for PwSNs, so the platform intends to provide access to the actual legal information regarding accessible tourism. The interfaces related to these functionalities are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Interfaces regarding functionalities for the demand agent. From left to right: (a) accessible tourism investigation, (b) support activities, and (c) legislation regarding accessible tourism.

3.4.2. Functionalities for the Supply Agent

Other integral parts of the access@tour by action are the supply agents (tourism supply agents, tourism operators, and municipalities) who wish to promote their accessible offerings within the platform. Bearing this in mind, these users can access the homepage, where the different functionalities are displayed once registered. Supply agents can manage tourism offers (insert, edit, and delete tourism offers), search for training courses in accessible tourism, discover tourism support activities, look for qualified personnel, post job openings, and seek out accessible tourism projects and financial assistance. Beyond these fundamental interactions, supply agents also have access to a toolbar that enables them to communicate with other users, set specific notifications, access system definitions, and return to their homepage. As noted earlier, supply agents can search within the platform for other users by entering keywords in the search bar at the top of the interface.

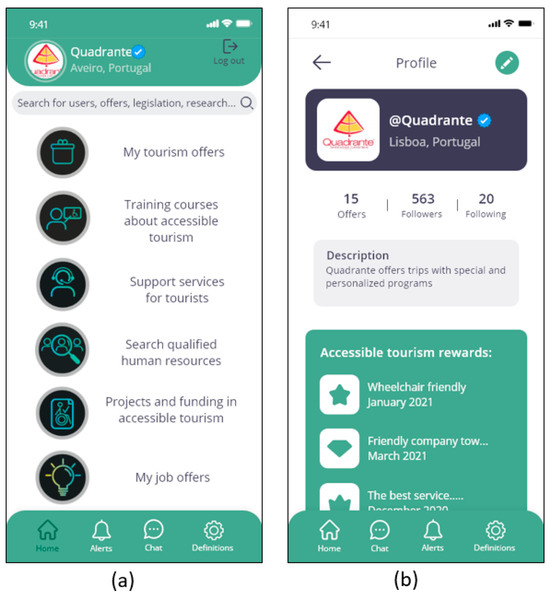

Regarding the user profile interface, the interface contains a description of the supply agent, all tourism offers associated with the user, and job opportunities offered by the user. Besides this, the page also contains accessibility certificates and prizes won within the scope of accessible tourism. The homepage and interfaces related to the user profile are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Interfaces representing the different interactions a supply agent can have with the platform and its user profile. From left to right: (a) the demand agent homepage, and (b) the user profile.

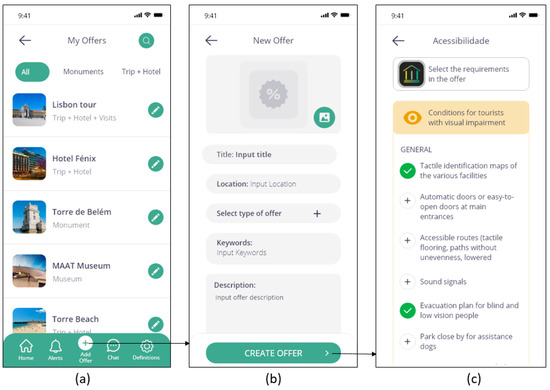

As one of the main objectives is to promote accessible tourism offers, this type of user is responsible for entering their respective offers into the platform and making available all the information related to accessibility. After selecting “Tourism offers” on the homepage, the users will be directed to an interface where they can view all of their offers or edit existing ones. It is also possible to insert new offers by clicking on the new button, “add new offer” (plus button), in the toolbar. Inserting and editing an offer on the platform was made a simple task. The process of creating the offer consists of introducing the primary information, such as a title, location, keywords, and a brief description. After all basic information is completed, it will be necessary to introduce accessibility data. This process is conducted in a particular interface regarding different types of special needs. The information regarding accessibility will generate the accessibility report, which will later need to be validated by eventual visitors. The interfaces related to managing tourism offers are displayed in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Interfaces for managing tourism offers. From left to right: (a) list offers, (b) create a new offer, and (c) insert an accessibility report.

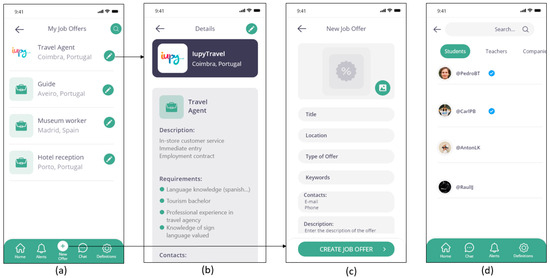

The platform also allows Supply agents to share their employment offers. The intention is to establish communication bridges between the tourism supply and the accessible tourism job market. Supply agents can access a list containing all the inserted job offers. Similar to their tourism offers, job offers can also be edited or eliminated. Some important information to include in the insertion form is related to communication contacts. An example of a job offer and the interfaces to manage the list of job offers and job offer insertion is illustrated in Figure 11. The objective is for potential candidates to use the given contacts to apply for a job position. These job positions must be related to accessible tourism. Since supply agents are able to share job offers, these entities also have the possibility to search for specific human resources, which can be seen as an excellent opportunity to establish communication with other types of users. Essentially, it introduces students to job opportunities within the accessible tourism market.

Figure 11.

Interfaces regarding job offers. From left to right: (a) managing job offers, (b) an example of a job offer, (c) inserting a new job offer, and (d) searching for employees that match hiring criteria.

Other functionalities for supply agents include searching for training courses and projects in accessible tourism, as well as support services (Figure 12). In the hope of making their offers more accessible and reaching PwSNs, it may be necessary for supply agents to look for training opportunities for their employees. Similarly, supply agents may want to be part of projects, so the platform intends to provide information about different projects with several aims in the area of accessible tourism. This can hopefully improve human resource training on the necessary capabilities for engaging with the accessible tourism market. There is also a functionality to search for support services, as to provide more accessibility conditions, it may be necessary to complement offers with support activities for PwSNs.

Figure 12.

Interfaces regarding the remaining functionalities for supply agents. From left to right: (a) search for training courses in accessible tourism, (b) search for accessible tourism projects, and (c) search for support services.

3.4.3. Functionalities for the Tourism Teacher

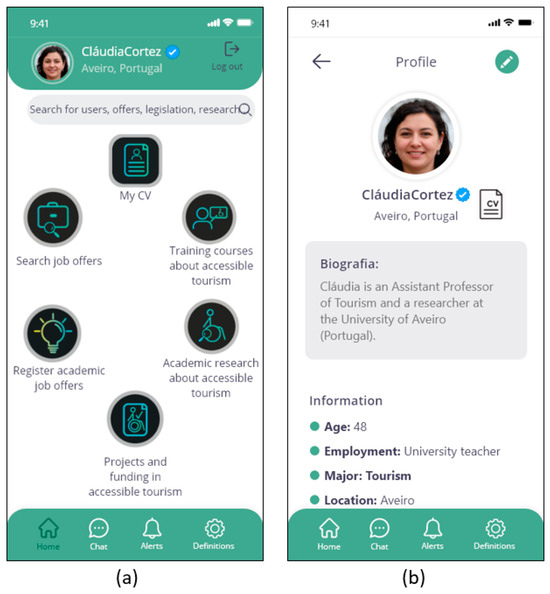

Introducing accessibility topics in tourism study programs is a relevant tool to improve accessible tourism conditions. In this regard, the platform intends to present tourism teachers with the possibility of stimulating knowledge regarding accessibility, as demonstrated in the homepage and user profile interfaces (Figure 13). On the homepage for tourism teachers, it is possible to insert their CV into the platform, search for employment positions (such as university teaching roles) or post-employment opportunities, seek training in the field of accessible tourism, explore academic research studies, and discover projects related to accessible tourism, as well as funding programs. The insertion of the CV is important because it allows the user to share information related to accessibility work. The user profile interface contains information regarding academic research and direct access to the inserted CV by clicking on the respective buttons. Ultimately, incorporating this type of user aims to cultivate an academic interest in the research area of accessible tourism.

Figure 13.

Interfaces representing the different interactions a tourism teacher can have on the platform and its user profile. From left to right: (a) the tourism teacher homepage, and (b) the user profile.

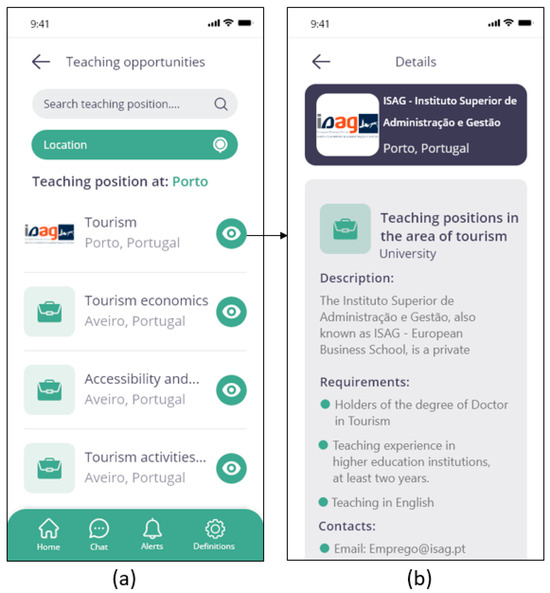

An exciting functionality available for tourism teachers is the search for teaching jobs and the insertion of research employment positions for interested students. This available interaction with the platform intends to illustrate how the platform can be self-sufficient, as the users can insert information inputs and retrieve information outputs. As illustrated in Figure 14, the access@tour by action allows teachers to search for teaching positions in higher education institutions.

Figure 14.

Interfaces for searching and inserting job offers. From left to right: (a) searching for a job offer, and (b) an example of a job offer for a teaching position.

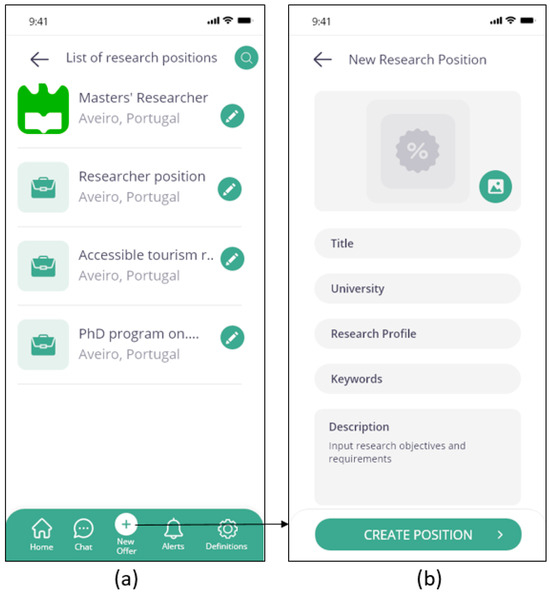

On the other hand, as verified in Figure 15, the tourism teacher can also insert job offers into the system. The main goal is to look for students for investigation projects, thus offering academic research positions in accessible tourism projects. The user can access a list stating all their inserted research positions. On this page, they can edit or delete investigation offers and add new ones into the system.

Figure 15.

Interfaces for inserting research positions. From left to right: (a) list of research positions, and (b) add a new job offer for a research position into the system.

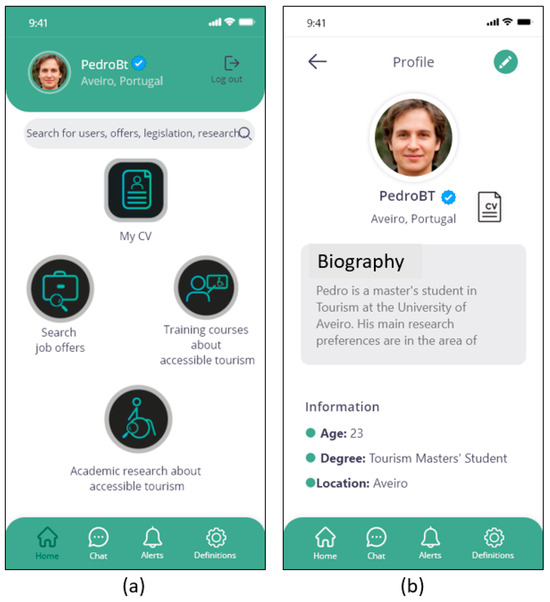

3.4.4. Functionalities for the Tourism Student

Just like tourism teachers, students are vital in ensuring that the tourism industry personnel possess the necessary knowledge and skills to address the requirements of accessible tourism. The access@tour by action provides tourism students with the opportunity to submit their CVs, explore job openings in accessible tourism, seek training and educational resources focused on enhancing accessibility in tourism, and access academic research related to accessible tourism. Including students as a key system component will facilitate the sharing of scientific knowledge related to accessible tourism. Students will be the future workforce in accessible tourism, so it is vital to ensure they have the necessary skills in terms of accessibility. This is demonstrated in the homepage and user profile interfaces (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Interfaces representing the different interactions a tourism student has with the platform and its user profile. From left to right: (a) the tourism student homepage, and (b) the user profile.

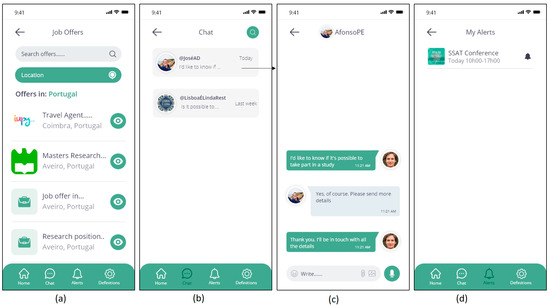

The search for job offers follows a systematic process. It is essential to understand that either supply agents or tourism teachers can insert these offers into the platform. This allows the students to enter the job market or pursue a more academic career. The information available in the profile may provide significant details when researching human resources. Moreover, the students, like the other types of users, can access the chat option that allows communication between the different users supported by the platform and alerts configuration. The interfaces related to job opportunities, communication via chat between two users, and alert configuration are illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Interfaces representing different interactions. From left to right: (a) the job opportunity list, (b) the chat option display, (c) an example of a chat with another user, and (d) alerts configuration.

4. Discussion

With the completion of the development process of access@tour by action, it is crucial to discuss the fact that, according to previous research studies [21,22,23,24], there is a notable gap in accessible tourism related to the lack of technological platforms that focus on promoting accessibility conditions. Some examples of currently available accessible tourism platforms are: Tourism for All [86]; Hands to discover [87]; Euans [88]; Travability [89]; Tourismus für Alle Deutschland [90]; and Tur4All [91]. A more detailed analysis of all identified solutions and their characteristics can be found in a previously performed benchmarking study and disclosed in the study by Alves et al. [24]. The Tourism for All platform provides information related to accessibility for individuals with physical disabilities, detailing accessibility features, available services, airport proximity, and medical centers. Hands to Discover platform is a communication tool for people with hearing impairments, offering information in sign language related to tourism attractions, schedules, and possible places of interest. Euans is a platform dedicated to reviewing, sharing, and discovering accessible places where PwSNs, along with their families, friends, and caregivers can obtain and share information regarding accessibility of various tourism venues. Travability makes tourism destinations accessible by publishing accessible travel information and serve as a full-service travel agency for PwSNs. Tourismus für Alle Deutschland allows the booking tourism packages in Germany, presenting different options in line with personal accessibility requirements. Tur4All offers information on accommodations units, recreational activities, and restaurants supported by a community of users who assess and provide feedback on accessibility matters.

Despite these efforts, current platforms have limitations in fully addressing some accessibility components [99,100], especially regarding functionalities, features, and stakeholder integration. The access@tour by action tries to address these weaknesses. Thus, it is essential to highlight that several features offered by access@tour by action are not currently available on the accessible tourism platforms analyzed (e.g., provision of the legislation on accessible tourism, the insertion of accessibility requirements leading to automatically adapted tourism offers, search for personnel skilled in accessible tourism, insert work experience, find training opportunities, and discover academic research in accessible tourism). Many of these innovative features stem from the co-creation of tourism offers between stakeholders in accessible tourism. Additionally, the access@tour by action incorporates real-time information and location-based functionalities to assist users in traveling in non-familiar environments, further enhancing accessibility in tourism activities. Moreover, thanks to the methodology (UCD development and testing process) adopted, it was possible to specify better PwSNs requirements and correct accessibility faults, such as lack of text alternatives (to audio, image, and video content), easy navigation, and compatibility with assistive technology. Finally, overall, current platforms primarily focus on providing information about the accessibility features of tourism services. As a result, their scope is constrained, involving only demand and supply. This narrow focus restricts their impact, as they overlook the inclusion of educational institutions, which, as highlighted in previous research [101,102,103], plays a crucial role in advancing accessible tourism. For the reasons mentioned above, access@tour by action breaks apart from current solutions in the market, as it caters to different stakeholders of accessible tourism. The innovation in the form of stakeholder integration may offer important research implications. This is the case for education institutions, social organizations, and informal caregivers, as their role in accessible tourism is often overlooked. By integrating these users’ inputs with the appropriate requirement engineering process, the platform offers a view of how these stakeholders can be a crucial part of technology development for accessible tourism, describing all the benefits they bring to the table.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the conceptualization and development of the access@tour by action prototype, a technological platform to enhance accessibility conditions in tourism. The objective of this platform is to improve information flow and automation, enhancing access to content related to accessibility in tourism offers. A UCD methodology was followed to obtain this prototype, which involved gathering users’ requirements and developing a conceptual model of the technological platform using UML. Afterward, diverse platform functionalities were demonstrated through interfaces sourced directly from the access@tour by action prototype, which was created in Adobe XD. The different interfaces display the functionalities of the platform, which are available for the various types of users (stakeholders of the accessible tourism market).

The development of access@tour by action allowed for the establishment of significant practical and theoretical contributions. Regarding practical implications, this work intends to reduce the social exclusion of PwSNs, specifically in terms of access to tourism offers. Unfortunately, PwSNs are often excluded from tourism activities due to a lack of information regarding accessibility conditions. Thus, this study aims to provide a proposal for a technological platform that fosters effective communication/information channels and methods among demand agents (PwSNs, social organizations, and informal caregivers), tourism supply agents, and tourism educational institutions. This can boost accessibility conditions for PwSNs and improve the diffusion of services and educational opportunities related to accessible tourism. On the other hand, in terms of practical research implications, the emphasis should be on the methodology used to create access@tour by action. Hence, the presented fundamentals of the UCD methodology for developing the platform can be applied to other research areas. Since the process of gathering requirements for building the technological platform incorporates validated ways to obtain feedback from PwSNs, it can be utilized, for example, in research projects involving accessibility, for example, in areas such as health and education. This implies some appropriate adjustments (e.g., testing with health or education experts instead of tourism). Nevertheless, the methodological process of access@tour by action can help future developers have a validated basis for creating accessible solutions, especially geared toward PwSNs.

Despite this study’s results and pertinent contributions, limitations must be addressed. It was difficult to translate all gathered requirements into UML due to the limitations of representation in abstract models. To overcome this limitation, the conceptual model was subjected to expert validation, as previously explained. Regarding the developed prototype, some limitations should be pointed out. Only a few system features could be shown because the prototype was developed horizontally and was created in Adobe XD. Several functionalities of the platform were demonstrated through screenshots taken from the prototype, which prevents to illustrate the screens from presenting the information more interactively. This is also reflected in some interfaces, where the implementation of accessibility standards, such as audio description, input assistance, and integration with assistive technology, was not perceivable. Moreover, it is necessary to be aware that implementing all complex accessibility components of the platform (e.g., support in sign language) may be time-consuming and labor-intensive. It is essential to have these small nuances in mind when transforming the prototype into an actual technology. Despite these limitations, this work could demonstrate the capacities of the access@tour by action processes, not only in terms of functionalities but also in its methodology processing and content delivery. As discussed, these factors make access@tour by action a unique and distinguishable solution compared to the utilities of existing platforms.

Regarding future work, we intend to proceed with the implementation of the access@tour by action. Benchmarking and technology installation studies will be conducted to understand how the implementation in the market can be made and what software is most adequate to develop and program the technological platform. It will be necessary to outline goals, establish objectives for integrating the new platform, and involve the key stakeholders in a possible strategy-building process. On the other hand, special attention should be given to accessibility. Despite the complexity of implementing accessibility requirements, there is a need for these requirements to remain a top priority during all the implementation stages. For that reason, it may be necessary to find support from large development teams while raising their awareness of the necessity of accessible practices. Furthermore, it is important to continue applying iterative development and UCD. The access@tour by action must remain adaptable in its architecture and design since, throughout implementation strategies, it may be necessary to modify the platform without completely overhauling it or interfering with its existing and established functionalities. Alas, after attaining a complete and functional version of the access@tour by action, it is also intended to integrate digital transformation concepts within the scope of Tourism 4.0 [104] and even Tourism 5.0 [95]. To conduct this, a thorough literature analysis may be required to comprehend how innovative technological drivers (e.g., augmented reality, virtual reality, chatbots, artificial intelligence) might revamp the accessibility of tourism platforms. This will offer crucial information on how cutting-edge technology can be incorporated into access@tour by action, ensuring that the solution becomes innovative while remaining user-friendly and offering even more accessibility components, further improving accessible tourism conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T., C.E. and L.T.; methodology, P.T.; software, P.T.; validation, C.E. and L.T.; formal analysis, C.E. and L.T.; investigation, P.T.; data curation, P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, C.E. and L.T.; visualization, P.T.; C.E. and L.T.; supervision, C.E. and L.T.; project administration, C.E. and L.T.; funding acquisition, C.E. and L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by national funds through the Institute of Electronics and Informatics Engineering of Aveiro (IEETA) (UIDB/00127/2020), Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policy (GOVCOPP) research unit (UIDB/04058/2020) and FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (2023.00390.BD).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Buhalis, D.; Darcy, S. Accessible Tourism Concepts and Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781845411619. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, M.; Vimarlund, V. Digital Technologies for Social Inclusion of Individuals with Disabilities. Health Technol. 2018, 8, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T. A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 16, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Agarwal, S.; Kim, H.J. Influences of Travel Constraints on the People with Disabilities’ Intention to Travel: An Application of Seligman’s Helplessness Theory. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaganek, K.; Ambroży, T.; Mucha, D.; Jurczak, A.; Bornikowska, A.; Ostrowski, A.; Janiszewska, R.; Mucha, T. Barriers to Participation in Tourism in the Disabled. Pol. J. Sport Tour. 2017, 24, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiel, M. Barriers in Undertaking Tourist Activity by Disabled People. Bibl. Główna Akad. Im. Jana Długosza w Częstochowie. 2016, 15, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rucci, A.C.; Porto, N. Accessibility in Tourist Sites in Spain: Does It Really Matter When Choosing a Destination? Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 31, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; McKercher, B.; Schweinsberg, S. From Tourism and Disability to Accessible Tourism: A Perspective Article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Cameron, B.; Pegg, S. Accessible Tourism and Sustainability: A Discussion and Case Study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, I.; Costa, E.; Sousa Pinto, A.; Abreu, A. Infoaccessibility on the Websites of Inbound Markets of Portugal Destination. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Smart Systems; Rocha, Á., Abreu, A., de Carvalho, J., Liberato, D., González, E., Liberato, P., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 171, pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, C.F.; Sousa, B.M. A Acessibilidade No Etourism: Um Estudo Na Ótica Das Pessoas Portadoras de Necessidades Especiais. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2019, 17, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portales, R.C. Removing “Invisible” Barriers: Opening Paths towards the Future of Accessible Tourism. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Eichhorn, V.; Michopoulou, E.; Miller, G. Accessibility Market and Stakeholder Analysis; University of Surrey: Surrey, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, C.; Alves, J.; Rosa, M.J.; Teixeira, L. Are Higher Education Institutions Preparing Future Tourism Professionals for Tourism for All? An Overview from Portuguese Higher Education Tourism Programmes. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2022, 31, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Pegg, S. Towards Strategic Intent: Perceptions of Disability Service Provision amongst Hotel Accommodation Managers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Teixeira, P.; Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L. The Tourism Supply Agents’ View on the Development of an Accessible Tourism Information System. In Proceedings of the 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021; Rocha, Á., Gonçalves, R., Peñalvo, F., Martins, J., Eds.; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Irestig, M.; Timpka, T. Politics and Technology in Health Information Systems Development: A Discourse Analysis of Conflicts Addressed in a Systems Design Group. J. Biomed. Inform. 2008, 41, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, Y.; Ellis, T.J. A Systems Approach to Conduct an Effective Literature Review in Support of Information Systems Research. Informing Sci. 2006, 9, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangani, A.; Bassi, L. Web Information, Accessibility and Museum Ownership. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2019, 9, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, A.; Altinay, F.; Altinay, Z.; Zhang, Y. Envisioning the Future of Technology Integration for Accessible Hospitality and Tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4460–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J.J.; Peters, M. The Evolution of ICTs in Accessible Tourism: A Stakeholder Collaboration Analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.R.; Silva, A.; Barbosa, F.; Silva, A.P.; Metrôlho, J.C. Mobile Applications for Accessible Tourism: Overview, Challenges and a Proposed Platform. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 19, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L. Diversity of Web Accessibility in Tourism: Evidence Based on a Literature Review. Technol. Disabil. 2021, 33, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, J.; Teixeira, P.; Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L. Benchmarking of Technological Platforms for Accessible Tourism: A Study Resulting in an Innovative Solution—Access@tour. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.; Barroso, J.; Gonçalves, R. Supporting Accessibility in Higher Education Information Systems. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Applications and Services for Quality of Life: 7th International Conference, UAHCI 2013, Held as Part of HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 21–26 July 2013, Proceedings, Part III 7; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8011, pp. 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Sandfreni, S.; Adikara, F. The Implementation of Soft System Methodology (SSM) for Systems Development in Organizations (Study Case: The Development of Tourism Information System in Palembang City). In Proceedings of the First International Conference of Science, Engineering and Technology, ICSET 2019, Jakarta, Indonesia, 23 November 2019; EAI: Gent, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, L.; Saavedra, V.; Santos, B.S.; Ferreira, C. Integrating Human Factors in Information Systems Development: User Centred and Agile Development Approaches. In Digital Human Modeling: Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management: 7th International Conference, DHM 2016, Held as Part of HCI International 2016, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016, Proceedings 7; Duffy, V., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9745, pp. 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, K.; Nyanjom, J.; Slaven, J. Disability, Hospitality and the New Sharing Economy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S.; Diekmann, A. The Rights to Tourism: Reflections on Social Tourism and Human Rights. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S. Developing Sustainable Approaches to Accessible Accommodation Information Provision: A Foundation for Strategic Knowledge Management. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2011, 36, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Global and Regional Tourism Performance. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44575 (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- ENAT-Business Opportunities of Accessible Tourism in Europe. Available online: https://www.accessibletourism.org/resources/enat_jaen-ambrose-final.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2019).

- European Commission. Enhancing What European Tourism Has to Offer-Accessible Tourism. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/offer/accessible_en (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Milicchio, F.; Prosperi, M. Accessible Tourism for the Deaf via Mobile Apps. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments-PETRA ’16, New York, NY, USA, 29 June–1 July 2016; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente-Robles, Y.M.; Muñoz-de-Dios, M.D.; Mudarra-Fernández, A.B.; Ricoy-Cano, A.J. Understanding Stakeholder Attitudes, Needs and Trends in Accessible Tourism: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, S.; Sonderegger, A.; Sauer, J. Implementing Recommendations From Web Accessibility Guidelines: Would They Also Provide Benefits to Nondisabled Users. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2016, 58, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Engel, C.; Loitsch, C.; Stiefelhagen, R.; Weber, G. Traveling More Independently: A Study on the Diverse Needs and Challenges of People with Visual or Mobility Impairments in Unfamiliar Indoor Environments. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2022, 15, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusébio, C.; Alves, J.; Carneiro, M.J.; Teixeira, L. Needs, Motivations, Constraints and Benefits of People with Disabilities Participating in Tourism Activities: The View of Formal Caregivers. Ann. Leis. Res. 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillovic, B.; McIntosh, A. Accessibility and Inclusive Tourism Development: Current State and Future Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühretmair, F. It’s Time to Make ETourism Accessible. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassiot, A.; Prats, L.; Coromina, L. Tourism Constraints for Spanish Tourists with Disabilities: Scale Development and Validation. Doc. D’analisi Geogr. 2018, 64, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.S.; Costa, E.; Borges, I.; Silva, F.; Abreu, A. Virtual Accessibility on Digital Business Websites and Tourist Distribution. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Smart Systems; Rocha, Á., Abreu, A., de Carvalho, J., Liberato, D., González, E., Liberato, P., Eds.; Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 171, pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Stumbo, N.J.; Pegg, S. Travelers and Tourists with Disabilities: A Matter of Priorities and Loyalties. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 8, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Darcy, S. Tourism, Disability and Mobility. In Tourism and Inequality: Problems and Prospects; Cole, S., Morgan, N., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2010; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, G.; Varriale, L.; Ferrara, M. Internet for Supporting and Promoting Accessible Tourism: Evidence from Italy. In ICT for an Inclusive World; Baghdadi, Y., Harfouche, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chikuta, O.; du Plessis, E.; Saayman, M. Accessibility Expectations of Tourists with Disabilities in National Parks. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, S.; Scott II, W.L.; Trewin, S. Accessibility Information Needs in the Enterprise. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2019, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Stankov, U. ICTs and Well-Being: Challenges and Opportunities for Tourism. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2021, 23, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L. How to Develop Information Systems to Improve Accessible Tourism: Proposal of a Roadmap to Support the Development of Accessible Solutions. Computers 2024, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Vila, T.; Alén González, E.; Darcy, S. Accessible Tourism Online Resources: A Northern European Perspective. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I. When Travel Is a Challenge: Travel Medicine and the ‘Dis-Abled’ Traveller. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 22, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou, E.; Darcy, S.; Ambrose, I.; Buhalis, D. Accessible Tourism Futures: The World We Dream to Live in and the Opportunities We Hope to Have. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.; Alves, J.; Eusébio, C.; Teixeira, L. The Role of Higher Education Institutions in the Accessible Tourism Ecosystem: Requirements for the Conceptualization of an Information System. In Trends and Applications in Information Systems and Technologies. WorldCIST 2021, Proceedings of the 9th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (WorldCIST’21), Terceira Island, Azores, Portugal, 30 March–2 April 2021; Rocha, Á., Adeli, H., Dzemyda, G., Moreira, F., Ramalho Correia, A.M., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1367, pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.; Godinho, F.; Gonçalves, P.; Gonçalves, R. Usability and Accessibility Evaluation of the ICT Accessibility Requirements Tool Prototype. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Novel Design Approaches and Technologies. Proceedings of the HCII 2022, Virtual Event, 26 June–1 July 2022; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13308, pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau, S.; Georggi, N.; Winters, P. Global Positioning System Integrated with Personalized Real-Time Transit Information from Automatic Vehicle Location. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2143, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrouzeh, M.P.; Dewar, K.; Fleet, G.; Bourgeois, Y. Implementing ICT for Tourists with Disabilities. In Proceedings of the ICEBT ’17: Proceedings of the 2017 1st International Conference on E-Education, E-Business and E-Technology, Toronto, ON, Canada, 10–12 September 2017; Volume 7, pp. 50–53. [CrossRef]

- Fall, C.L.; Quevillon, F.; Blouin, M.; Latour, S.; Campeau-Lecours, A.; Gosselin, C.; Gosselin, B. A Multimodal Adaptive Wireless Control Interface for People with Upper-Body Disabilities. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2018, 12, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angkananon, K.; Wald, M.; Gilbert, L. Technology Enhanced Interaction Framework and Method for Accessibility in Thai Museums. In Proceedings of the 2015 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Nusa Dua, Bali, Indonesia, 27–29 May 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth, A.; Williams, P. Using QR Codes to Aid Accessibility in a Museum. J. Assist. Technol. 2012, 6, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Webster, C.; Berezina, K. Adoption of Robots and Service Automation by Tourism and Hospitality Companies. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2017, 27, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Michopoulou, E. Information-Enabled Tourism Destination Marketing: Addressing the Accessibility Market. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]