Abstract

Over the past 10 years, the use of augmented reality (AR) applications to assist individuals with special needs such as intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and physical disabilities has become more widespread. The beneficial features of AR for individuals with autism have driven a large amount of research into using this technology in assisting against autism-related impairments. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of AR in rehabilitating and training individuals with ASD through a systematic review using the PRISMA methodology. A comprehensive search of relevant databases was conducted, and 25 articles were selected for further investigation after being filtered based on inclusion criteria. The studies focused on areas such as social interaction, emotion recognition, cooperation, learning, cognitive skills, and living skills. The results showed that AR intervention was most effective in improving individuals’ social skills, followed by learning, behavioral, and living skills. This systematic review provides guidance for future research by highlighting the limitations in current research designs, control groups, sample sizes, and assessment and feedback methods. The findings indicate that augmented reality could be a useful and practical tool for supporting individuals with ASD in daily life activities and promoting their social interactions.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neuro-developmental disorder determined by difficulties with social communication, restricted interests, and compulsive behavior [1]. Early detection of ASD is possible between the ages of 18 and 24 months; at this time, the diagnostic symptoms can be distinguished from regular developmental delays as well as other developmental disorders [2]. Globally, it is estimated that one in 100 children suffers from ASD. Significant advancements in international policy have significantly complemented the developments in autism research. Along with the policy changes brought about by the significant rise in global consciousness and campaigns, autism has been impacted by advancements in related fields including human rights, maternal and child health, and mental well-being [3,4,5,6]. The foundation and impetus for this development came from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which outlines key principles such as respect for dignity, freedom of choice, non-discrimination, full participation and inclusion in society, and accepting people with disabilities as a part of human diversity.

Each child with ASD is unique; it is possible that a technological solution that is beneficial for one child may not be effective for another. Therefore, researchers have begun to integrate a variety of technology for the betterment of children with autism with an aim of determining the best suited technologies for each individual. Technologies such as computer-based tools, virtual/augmented reality, mobile- and tablet-based applications, and robotics are currently viewed as propitious approaches for designing interventions for ASD, addressing a variety of goals including social and learning skills, on-task behavior, and challenging behaviors [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Early intensive behavioral intervention can ameliorate some of the symptoms of autism [7]. Nevertheless, the tools of certain classic media intervention approaches, such as video modeling (VM), are typically overly lengthy and lack an interactive mechanism [8,9,10]. It is difficult for ASD children to dynamically alter their cognitive focus and position. In recent years, information and communication technologies (ICTs) have been deployed extensively in the healthcare industry [11]. In the field of autism rehabilitation, technology-based interventions (TBI) include social robots [12], computer-based interventions [13,14], VR [15,16], tablet computers [17], and serious games [18,19].

As a new form of human–computer interaction (HCI) technology, AR has advanced significantly throughout the last few years to offer rich visual information and diverse interactive experiences by combining real scene information and virtual information [20,21,22]. AR presents fresh ideas for enhancing the learning experience [23]. There is evidence that autistic individuals are eager to analyze visual information and use electronic gadgets [24]. In addition, according to their parents, technology, such as tablets and smartphones, are significantly beneficial in treating these behavior issues [24,25]. Applications of mobile augmented reality (MAR) make the treatment more engaging [26,27] and improve the academic progress of children with autism [28].

In recent years, there has been a great deal of interest in examining the efficacy of technology-based strategies in training and teaching different skills, such as communication and social skills, academic skills, and information processing, to increase independence in children and adolescents with ASD. Marto et al. conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) of 16 primary papers on the use of augmented reality (AR) for the rehabilitation of people with ASD [29]. Only eight studies on MAR were considered. However, the authors of [30] examined ten preliminary studies published between 2012 and 2016 and made recommendations for future research and evaluation. Similarly, the collection contains only six studies on MAR. Adnan et al. [31] articulated AR’s development and research prospects in the treatment of autism; however, the literature study was inadequate. Khowaja et al. [32] presented a systematic literature review of major works published in 2005–2018 on AR intervention in improving a variety of skills in children and adolescents with ASD and presented the research classification of ASD. However, the article did not include MAR and the research timeline must be revised. Berenguer et al. [33] assessed the efficacy of AR technology on ASD.

1.1. Research Question and Objects

Through a systematic review, this study examines how AR methods are used with children who have ASD. This study seeks to answer the following question by conducting a systematic review using the PRISMA methodology:

How effective are augmented reality interventions for the training and rehabilitation of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in terms of social interaction, emotion recognition, cooperation, learning, cognitive skills, and living skills?

Additionally, by systematically evaluating the existing literature, this study seeks to address the following research objectives:

- Systematically review the existing literature on augmented reality interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD);

- Evaluate the effectiveness of augmented reality interventions in rehabilitating and training individuals with ASD across various domains, including social interaction, emotion recognition, cooperation, learning, cognitive skills, and living skills;

- Identify the strengths and limitations of the current research designs, control groups, sample sizes, and assessment and feedback methods used in the reviewed studies.

1.2. Contributions and Organization

This article presents a systematic literature review on the application of AR interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with an aim to investigate the recent trends, potential, and future research in AR technologies for the purpose of autism spectrum disorder intervention. This SLR includes works in the time span from 2010 to 2022. A summary of this work’s essential contributions are the following:

- We conducted a systematic search for studies evaluating the types of intervention on the ASD population and analyze the efficacy of AR intervention on a variety of functions, such as social and communication, emotion management, daily living, and cognitive skills;

- We discussed the limitations and future works of the existing research.

The remaining sections of the paper are structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the linked concepts first. Then, we present the methodology in Section 3 before delving into the detailed results in Section 4. In Section 5, the discussion and limitations are presented. In Section 6, we conclude the paper with suggestions for future research.

2. A Brief Overview of The Related Concepts

2.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as a condition characterized by deficits in two core domains: (1) social communication and social interaction and (2) restricted repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. Since 2013, the DSM-5 has included Asperger’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, Rett’s disorder, and a number of other related diseases such as ASD. Despite this, many researchers continue to interchange Asperger’s syndrome with ASD. According to a study conducted by the National Institute of Health (NIH) of the United States published in June 2018, 2.41 percent of American kids are diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. This represents a 0.94 percent increase from 2010. In Bangladesh, two community studies [34,35] conducted in 2005 and 2009 revealed that the statistics of children with autism were 0.2 and 0.84/1000 children, respectively.

2.2. Augmented Reality

Given the current technical advancements, AR technology is increasingly expanding into a range of fields, including gaming, travel, leisure, business, medicine, and education. Aggarwal and Singhal [36] define AR as the superimposition or augmentation of digital images onto real-world objects using a variety of AR technologies. The authors identified four distinct types of augmented reality: marker based, marker-less, projection based, and superimposition based. Marker-based augmented reality, also referred as image recognition, creates the output using a camera and a visual marker. Markers may consist of a quick response (QR) code, a two-dimensional (2D) code, a paper-based trigger image, or a physical object, provided that the camera can detect it. Marker-less augmented reality, also termed location-based augmented reality, utilizes a global positioning system (GPS) to provide location-based data. AR that relies on projection casts artificial light onto real-world objects. It is employed to project a three-dimensional (3D) interactive hologram. Another form is superimposition-based augmented reality, which replaces the original perspective of an object with an enhanced one, either partially or entirely. AR is contrasted with virtual reality (VR), another prominent immersion-based technology, in that digital information is augmented in the real world. In contrast, VR immerses the individual in an entirely virtual world.

Due to the proliferation of user-friendly and cost-effective mobile applications, augmented reality is also becoming more prevalent in education [37]. AR technology may be utilized to create interactive learning environments for children with ASD and intellectual development disability (IDD), allowing them to visualize complex topics and master a range of complicated activities in a visual environment [33,38]. The camera of a mobile device can be used to explore AR platforms while using AR. One can scan an image or marker, for instance, to display and manipulate digital information in a three-dimensional (3D) mode (e.g., a 3D visual of a cell will appear, which the user can touch or turn) or to display detailed information on an object (e.g., additional reading, video, or audio components will appear) [39]. AR technology has been determined to be an excellent instructional technology platform for assisting children with a wide range of impairments to acquire a variety of skills [40].

3. Methodology

3.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

To perform this literature review, we sifted through seven scientific article databases: IEEE Xplore Digital Library, ACM Digital Library, Science Direct, Scopus, PubMed, Sage, and Web of Science. While analyzing these resources, we only considered documents relevant to computer-related categories, such as technology, engineering, and computer science, disallowing medical and chemical disciplines. In addition, we chose articles that were published between January 2010 and November 2022, spanning thirteen years.

3.2. Search Strings

We devised the search strings based on the topics pertinent to our systematic literature review. We selected a list of specific keywords, including “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, “Augmented Reality”, “Inclusive Digital Technologies”, and “Smartphone” that would be relevant in answering our study questions. These strings focused on finding studies that studied or experimented with AR with ASD patients, taking into account user experience, accessibility, and region of experimentation. In Table 1, we list the search strings employed by the selected databases.

Table 1.

Keywords.

The search was conducted in order to match the following logical expression: Title/Keywords/Abstract contains (“Autism” OR “Autism Spectrum Disorder” OR “ASD” OR “Autistic” OR “Autistic Children”) AND (“Augmented Reality” OR “AR” OR “Mobile Augmented Reality” OR “Augmented” OR “Inclusive Digital Technologies”) AND (“Mobile” OR “Tablet” OR “Smartphone” OR “Toolkit” OR “Smartglass”).

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We incorporated the requirements illustrated in Table 2 in order to address the research queries based on the selected publications and gain a comprehensive understanding of the designs we are dealing with.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

3.4. Data Extraction

Using a systematic approach for data extraction, the whole text of each selected article was thoroughly evaluated in order to extract key information. The data extraction included the following domains: study design, study characteristics, method/algorithm employed, significant findings, region of experimentation, and assessment methodology. Table 3 illustrates the domains of each paper.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

4. Results

4.1. Data Selection

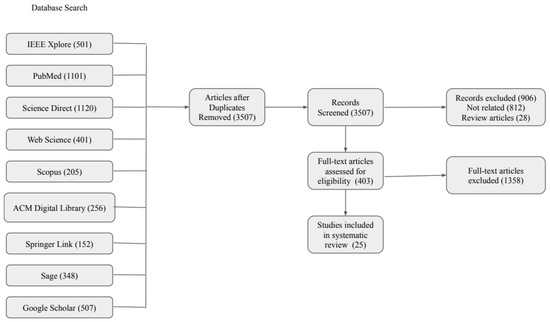

A summary of the selected articles is presented in Figure 1. It illustrates a PRISMA diagram and eventually selected articles for the review after the primary selection. We identified 4591 articles, out of which 501 were from IEEE Xplore, 1101 were from PubMed, 1120 were from Science Direct, 401 were from Web Science, 205 were from Scopus, 256 were from ACM library, 152 were from SpringerLink, 348 were from Sage, and 507 were from Google Scholar.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection procedure.

A total of 1084 duplicate papers were eliminated from the searches. The identified articles underwent a manual screening process based on their title and abstract. Subsequently, the articles were further screened based on their relevance in addressing the research questions. Following this rigorous screening process, out of the initial 3507 articles, only 25 articles met the inclusion criteria and were deemed suitable for further analysis in this systematic review. The study examined and collated the essential data from eligible studies, including the identity of the lead author, year of publication, characteristics of the participants, study design, and region of the experiment.

4.2. Descriptive Characteristics of The Selected Studies

4.2.1. System Protocol Design

From the 25 studies reviewed, two studies [52,56] implemented empowered brain integration Google Glass and Face2Face module and four studies [41,54,57,63] developed their own android applications. The study [44] used a calculator app, HP Reveal, and AR markers using HP reveal. A recent study [51] implemented augmented reality animation, and some other studies [42,44,45,53,60] used different AR development applications such as HP Reveal, Unity Vuforia, Kinect, AR Kit, MAKAR, and Aurasma. In [48], the authors introduced a computer game named “MoviLetrando”. The authors in [55] proposed and implemented deep learning models and simple, lightweight applications. Most of the studies reviewed [44,51,57,60,64] used the camera of tablets and smartphones. Two of the reviewed studies [52,56] used Google Glasses, whereas two other studies [45,54] used a computer monitor as the AR setup. Some other studies [41,44,45,54] used flashcards, worksheets, picture cards, and Tangram puzzles in the learning process.

4.2.2. Target Skills

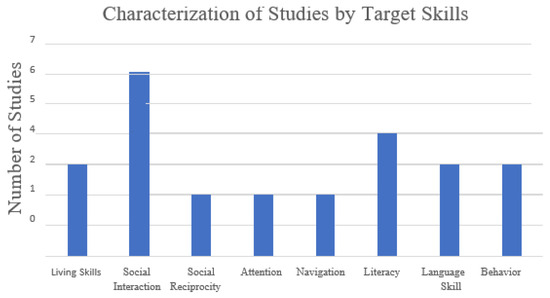

A plurality of the studies (8 out of the 25) focused on improving social skills, particularly social interaction and reciprocity. Meanwhile, three studies aimed to enhance daily living skills such as teeth brushing, and two others centered on improving focus and attention; illustrated in Figure 2. Three additional studies specifically addressed behavior modification. Finally, a total of seven studies aimed to improve literacy and language skills, specifically by increasing vocabulary.

Figure 2.

Characterization of studies by target skills.

4.2.3. Participant Characteristics

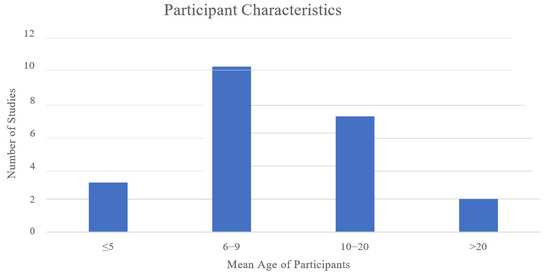

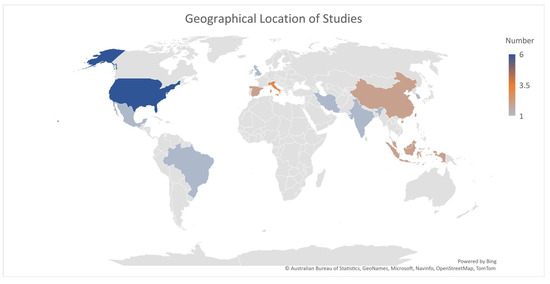

From the observation of Figure 3, Most of the studies included in this analysis involved participants whose ages ranged from 6 to 20 years old. Among all studies, 10 studies had a mean age between 6 and 9 years, and seven studies had a mean age between 10 and 20 years. Only three studies had a mean age below 5 years, and two studies had a mean age above 20 years old. Geographical location of the studies were also taken in account to illustrate the regions where the studies took place, it can been in Figure 4. Table 4 represents the assessment in which the characteristics of the studies were performed. This focuses on the inclusion criteria and the possible covariates of the selected studies.

Figure 3.

Participants Characteristics.

Figure 4.

Region of Experimentation.

Table 4.

Assessment Characteristics of Included Studies.

4.2.4. Region of Experimentation

A plurality of the studies included were performed in the United States (n = 6). Other studies were conducted in the UK, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, and India.

4.2.5. Quality Assessment of the Articles

The quality assessment of the included 25 papers was performed using Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) [65]. The CASP checklist has 10 questions divided in three sections: Section A, B, and C. Table 5 and Table 6 illustrates the CASP. Furthermore, Table 7 cumulatively illustrates the key features of the included studies. It shows the software and hardware that are used also the assessment method followed by the authors. The following questions of the sections have assisted in assessing the quality of the papers

Table 5.

Quality Assessment Using CASP-Section A.

Table 6.

Quality Assessment Using CASP-Section A and B.

Table 7.

System Protocol Design.

5. Discussion

This systematic literature review explores the potential of establishing a standard protocol in the field of technology to benefit children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The review analyzed twenty-five articles, published between 2010 and 2022, retrieved from various reputable databases. Participants’ ages ranged from 6 to 20 years old. However, three studies [51,57,58] did not mention the age of the participants. The findings emphasized the importance of having a standard protocol for data collection and the development of augmented reality (AR) technology tailored for children with ASD. Currently, AR researchers are creating impressive prototypes [18,21,28,48,51], but their implementation is hindered by a lack of communication between caregivers and developers. A crucial step towards progress involves fostering effective two-way communication between the researchers and the caregivers. Furthermore, government policy makers should actively engage in this field to support and empower children with ASD and their parents. The widespread adoption of this technology will heavily rely on the intervention and support of the government. Another objective of this review was to evaluate and summarize research that dealt with the efficacy of using AR programs in treating children and adolescents with ASD. Social skills, emotion recognition, daily living skills (brushing, finance, etc.), verbal and non-verbal communication, and learning can be distinguished as distinct areas of intervention when considering the capabilities of augmented reality technologies.

Social skills, the most obvious deficiency in children with ASD, were given the most attention in the examined AR study. Using a blend of real-world and virtual elements to replicate social environments allows for the training to occur in a safe, regulated, and customizable environment. For ASD treatment, the characteristics of this kind of intervention are particularly intriguing. In these articles, improvements in social–emotional reciprocity and emotional intelligence [28,47,50,53,59] were significantly observed. It is important to highlight that among the 25 selected papers, 18 of them documented notable enhancements in social-emotional reciprocity and emotional intelligence. In Table 3, we have illustrated the study purpose of each study and its outcome. Additionally, these approaches assist in the development of important social abilities such as initiation of play, social response, and facial expression perception. The studies [26,28] found that AR systems can positively improve understanding of social greeting behavior and learning appropriate responses to greetings. A few other studies [22,42] evaluated the feasibility of game content to assist autistic children with their social and emotional development. Other studies have been based on areas related to training in activities of daily living skills, teaching language, education and improving attention to individuals with ASD. Studies [41,48,51,55,62,63], demonstrate that using augmented reality can offer adjustable learning environments including videos, 3D images, and animation where people with special needs can engage in more fulfilling interaction activities. Children and adolescents with ASD could learn basic human skills such as tooth brushing and financial skills through AR intervention [44,47].

The majority of the included research suggests that children with ASD benefit from exposure to AR-based interventions. However, the majority of research utilized small sample sizes. Two studies [46,52] only comprised a single subject. Fourteen of the twenty-five studies had individuals under the age of ten. One study cited as [58] missed the number of participants. There was rarely any kind of comparison to either a group of healthy volunteers or patients who were receiving conventional therapies. If the control group does not exhibit the similar features or the same questionnaires are provided at distinct points in the intervention procedure, comparing the changes produced by an AR intervention could be challenging. Considering this, some of the findings from the research included in this study might be regarded as preliminary and having limited practical utility. Due to the limited sample size and lack of a control group, extending the results to the entire population impacted by this disorder is challenging. Another factor that makes it difficult to generalize the results is the sample’s gender ratio. It is established that ASD affects boys more frequently than girls (the most recent research indicates a 4:1 ratio [2]); however, certain studies [46,52,60] are conducted exclusively with affected boys, which may limit the validity of the conclusions. Lastly, it should be mentioned that some research was conducted on children labeled with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome. Consequently, only results from this sub-sample should be evaluated, as they cannot be generalized to the remaining children with ASD.

One of the primary benefits of augmented reality is that it enables the simulation of real-world circumstances so that training may be undertaken in a safe, therapist-controlled environment. This issue is particularly intriguing when treatment should concentrate on the training and enhancement of social skills, social interaction, communication, emotional reaction, and executive functions. In addition, this intervention style can be further extended to acquire various subject performance measures. This enables therapists to monitor and analyze the patient’s progress and to apply feedback or possible task repetitions. Consequently, an intervention based on technology may incorporate multi-user apps in playful environments or everyday scenarios, which could be regulated and customized based on the intervention’s goals. Despite the numerous potential benefits of augmented reality, it is recommended that practitioners do cost–benefit analyses to see whether there is a benefit to facilitating the specific interventions or intervention components under consideration with augmented reality. Notably, the majority of the research included in this evaluation still relied on the therapist to prompt or correct errors. This prompts the question of whether the integration of AR would lead to more effective and efficient therapies. It is also likely that there exist low-tech alternatives that achieve the same effects as augmented reality. Therefore, it would be useful to identify the qualities of the individuals for which AR technologies are most beneficial (e.g., cognitive ability, physical ability, etc.).

In accordance with the WHO Ethics Review Committee (ERC), when proposing research with human participants, an Informed Consent Form (ICF) must be included with each proposal to establish that the study participant has chosen to participate in the research voluntarily. If the research involves more than one group of participants, such as healthcare users and healthcare professionals, a separate, individualized informed consent form must be supplied for each group. This guarantees that each participant group receives the necessary information to make an informed decision. Each new intervention requires a different informed consent form for the same reason. Twelve of the research explicitly state that written agreement was obtained from the participants. However, in the other thirteen investigations, there was no statement of a signed consent form. In research initiatives, evaluation methods are also a major concern. Both survey research and qualitative research rely on human participation and require well-trained observers to ensure accurate and reliable results. Without proper training, the error rate can increase, and the usefulness and reliability of the measurement can decrease. To avoid the introduction of human errors, researchers should implement a comprehensive training program for observers prior to the intervention. This training should cover all aspects of the research process, including data collection and analysis, to ensure that observers are equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to carry out their tasks accurately. Additionally, researchers can minimize the risk of human errors by conducting numerous calculations of the data or by using computer-assisted data gathering techniques. These methods can help to streamline the data collection process and reduce the potential for human error. In addition, the majority of research did not employ a particular method for evaluating the efficacy of AR interventions. Several studies [22,26,28,41,42,43,45,48,56,61,64] used a variety of established methods, including the Mann–Whitney U Test, Wilcoxon signed-rank Test, Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), ABC-H, CARS2, BPVS3, LSA, and ANOVA. Some research gathered input from participants, parents, or teachers through survey questionnaires, whereas others employed verbal feedback. A few other studies did not mention any such feedback method. Only four studies disclosed their questionnaire form in the papers.

Based on the reviews of selected articles, it is evident that future research in the field of AR for individuals with ASD should pay closer attention to comparing the various AR technologies employed because AR encompasses a wide range of technologies, some of which may potentially have compatibility issues, particularly concerning user immersion. Therefore, it is advisable that the researchers should shed light on AR technologies on their relative effectiveness, usability, and potential limitations.

Most of the studies included in this review were conducted in developed countries (United Nations Development Programme). Out of 25 studies, a total of 15 studies were conducted in the developed countries. Augmented reality (AR) technology has the potential to bring many benefits to both developed and developing countries; however, there are some limitations to consider [66]. In many developing countries, access to technology, including smartphones and tablets, is limited. This can make it difficult for people to access and use AR applications. Internet connectivity in many developing countries is also limited, which can make it difficult for people to access and use AR applications that require a stable internet connection. Apart from that, in some areas, electricity is not available or is not reliable, which can make it difficult to use devices that require electricity, such as smartphones and tablets. Another limitation is that many AR applications are developed primarily in English, which can make them difficult to use for people in developing countries who speak other languages. Additionally, developing countries often have limited financial resources, which can make it difficult for people to afford to purchase technology such as smartphones and tablets, or to pay for internet connectivity. Finally, many developing countries may not have the necessary infrastructure or regulations to ensure the privacy and security of data collected or stored by AR applications. It is important to note that although there are limitations, researchers and practitioners are working to overcome these challenges and make AR technology more accessible and effective in developing countries.

Although this review has summarized and evaluated various studies, it is crucial to acknowledge that the effectiveness of interventions can vary widely from person to person. This individual variation presents a significant challenge when attempting to extrapolate data from individual studies to the entire ASD population. Therefore, it is important to provide emphasize the need for personalized, client-centered approaches in the treatment and support of individuals with ASD. This approach may lead to a better understanding of ASD as a spectrum and promote interventions aimed at enhancing the well-being and development of individuals with ASD.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

ASD, from its identification to its treatment, is a complicated condition; it does not appear in the same way in all children; its severity can be low, moderate, or severe; and according to many authors, it is a disorder with no cure and a lifetime duration. Because ASD manifests itself in children in a variety of ways and degrees, making them receptive to various stimuli, it seeks alternatives to the same behavior or reaction to the same stimulus. As a result, other particular areas must be targeted to strengthen their relationship with their environment. This study shows how effective AR intervention is at minimizing ASD-related deficiencies. The substantial effectiveness observed for activities of daily living could justify the use of AR therapies in clinical practice. For future research, the selection of participants, the type and duration of the intervention, and the choice of a measurement tool should incorporate more controlled features, and more effort should be devoted to follow-up assessments conducted weeks or months after the termination of the intervention to ensure that the effects of training are maintained. In our search, only peer-reviewed articles were included to eliminate a number of possibly relevant gray literature articles and conference papers. However, as our goal is to provide researchers and practitioners with constructive advice, it is essential to examine the quality of the studies. Future studies should aim to use the relevant study designs and procedures to close the gaps in the quality criteria. Heterogeneity of symptoms, individualized demands, and contextual circumstances are some critical features that are likely to be defined in future studies on autism. Furthermore, discussed as crucial AR features are multi-sensory integration, customization and flexibility, social interaction facilitation, generalization and transferability, and immersive and interactive experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.M.S.U.D. and M.R.; methodology, A.B.M.S.U.D.; software, F.A.A.; validation, F.S., N.R., M.A.U. and K.A.M.; formal analysis, A.B.M.S.U.D. and F.A.A.; investigation, A.B.M.S.U.D. and M.R.; resources, A.B.M.S.U.D.; data curation, A.B.M.S.U.D. and F.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.M.S.U.D.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A.; visualization, F.A.A.; supervision, A.B.M.S.U.D. and M.R.; project administration, N.R., M.A.U. and K.A.M.; funding acquisition, F.S., N.R., M.A.U. and K.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Institute for Advanced Research (IAR) of United International University (UIU) in collaboration with Office of Faculty Research, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB) under Grant UIU-IAR-01-2022-SE-34.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HCI | Human-Computer Interaction |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MAR | Mobile Augmented Reality |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| PHR | Personal Health Record |

| TBI | Technology-based Intervention |

| VM | Video Modeling |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Sharma, N.; Mishra, R.; Mishra, D. The fifth edition of diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (dsm-5): What is new for the pediatrician. Indian Pediatr. 2015, 52, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Meeting Report: Autism Spectrum Disorders and Other Developmental Disorders: From Raising Awareness to Building Capacity: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland 16–18 September 2013; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- WHO. Book Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- World Health Organization. Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: A Framework for Helping Children Survive and Thrive to Transform Health and Human Potential; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Eldevik, S.; Hastings, R.P.; Hughes, J.C.; Jahr, E.; Eikeseth, S.; Cross, S. Meta-analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, S.R. Interventions to facilitate social interaction for young children with autism: Review of available research and recommendations for educational intervention and future research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2002, 32, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axe, J.B.; Evans, C.J. Using video modeling to teach children with pdd-nos to respond to facial expressions. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, S.; Akullian, J. A meta-analysis of video modeling and video self-modeling interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Except. Child. 2007, 73, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowaja, K.; Salim, S.S. A systematic review of strategies and computer-based intervention (cbi) for reading comprehension of children with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2013, 7, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, P.; Tonacci, A.; Tartarisco, G.; Billeci, L.; Ruta, L.; Gangemi, S.; Pioggia, G. Autism and social robotics: A systematic review. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdoss, S.; Mulloy, A.; Lang, R.; O’Reilly, M.; Sigafoos, J.; Lancioni, G.; Didden, R.; Zein, F.E. Use of computer-based interventions to improve literacy skills in students with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 1306–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher-Watson, S. A targeted review of computer-assisted learning for people with autism spectrum disorder: Towards a consistent methodology. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 1, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, G.; Lledó, A.; Arráez-Vera, G.; Lorenzo-Lledó, A. The application of immersive virtual reality for students with asd: A review between 1990–2017. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Gresa, P.; Gil-Gómez, H.; Lozano-Quilis, J.-A.; Gil-Gómez, J.-A. Effectiveness of virtual reality for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: An evidence-based systematic review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagohara, D.M.; Meer, L.v.; Ramdoss, S.; O’Reilly, M.F.; Lancioni, G.E.; Davis, T.N.; Rispoli, M.; Lang, R.; Marschik, P.B.; Sutherland, D.; et al. Using ipods® and ipads® in teaching programs for individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, H.A.M.; Shahbodin, F.; Pee, N.C. Serious game for autism children: Review of literature. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2012, 6, 554–559. [Google Scholar]

- Zakari, H.M.; Ma, M.; Simmons, D. A review of serious games for children with autism spectrum disorders (asd). In International Conference on Serious Games Development and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Krevelen, D.V.; Poelman, R. A survey of augmented reality technologies, applications and limitations. Int. J. Virtual Real. 2010, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.S.; Sunar, M.S.; Ismail, A.W.; Andias, R. An inertial device-based user interaction with occlusion-free object handling in a handheld augmented reality. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Blackwell, A.F.; Coulouris, G. Using augmented reality to elicit pretend play for children with autism. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2014, 21, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.S.; Sunar, M.S.; Ismail, A.W. 3d object manipulation techniques in handheld mobile augmented reality interface: A review. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 40581–40601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Nions, E.; Happé, F.; Evers, K.; Boonen, H.; Noens, I. How do parents manage irritability, challenging behaviour, non-compliance and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders? A meta-synthesis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1272–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagatell, N. The routines and occupations of families with adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2016, 31, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Herrejon, R.E.; Poddar, O.; Herrera, G.; Sevilla, J. Customization support in computer-based technologies for autism: A systematic mapping study. Int. J. Human–Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 1273–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Leon, N.D.; Al-Jumaily, A. Augmented reality game therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Smart Sens. Intell. Syst. 2017, 7, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-J. Kinect-for-windows with augmented reality in an interactive roleplay system for children with an autism spectrum disorder. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, A.; Almeida, H.A.; Gonçalves, A. Using augmented reality in patients with autism: A systematic review. In ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Vision and Medical Image Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 454–463. [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannidis, C. The application of augmented reality for intervention to people with autism spectrum disorders. IOSR J. Mob. Comput. Appl. (IOSR-JMCA) 2017, 4, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, N.H.; Ahmad, I.; Abdullasim, N. Systematic review on augmented reality application for autism children. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst 2018, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja, K.; Banire, B.; Al-Thani, D.; Sqalli, M.T.; Aqle, A.; Shah, A.; Salim, S.S. Augmented reality for learning of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (asd): A systematic review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78779–78807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, C.; Baixauli, I.; Gómez, S.; Andrés, M.d.E.P.; Stasio, S.D. Exploring the impact of augmented reality in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullick, M.S.I.; Goodman, R. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among 5–10 year olds in rural, urban and slum areas in bangladesh: An exploratory study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005, 40, 633–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.; Rahman, A.; Choudhury, S.; Chowdhury, K.; Wahab, M.; Rahman, F. Prevalence of mental disorders, mental retardation, epilepsy and substance abuse in children. Bang. J. Psychiatry 2009, 23, 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.; Singhal, A. Augmented reality and its effect on our life. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence), Uttar Pradesh, India, 10–11 January 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 510–515. [Google Scholar]

- Akçayır, M.; Akçayır, G. Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellems, R.O.; Yakubova, G.; Morris, J.R.; Wheatley, A.; Chen, B.B. Using augmented and virtual reality to improve social, vocational, and academic outcomes of students with autism and other developmental disabilities. In Research Anthology on Inclusive Practices for Educators and Administrators in Special Education; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 737–756. [Google Scholar]

- Cakir, R.; Korkmaz, O. The effectiveness of augmented reality environments on individuals with special education needs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 1631–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baragash, R.S.; Al-Samarraie, H.; Moody, L.; Zaqout, F. Augmented reality and functional skills acquisition among individuals with special needs: A meta-analysis of group design studies. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2022, 37, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.U.; Yunus, M.M.; Norman, H. ’Areal-vocab’: An augmented reality English vocabulary mobile application to cater to mild autism children in response towards sustainable education for children with disabilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekar, D.M.; Kang, H.; Alao, H.; Yu, J. Feasibility of using multiplayer game-based dual-task training with augmented reality and personal health record on social skills and cognitive function in children with autism. Children 2022, 9, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuster, P.; Herrera, G.; Kossyvaki, L.; Ferrer, A. Enhancing joint attention skills in children on the autism spectrum through an augmented reality technology-mediated intervention. Children 2022, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, J.R.; Cox, S.K.; Davis, K.; Gonzales, S. Using augmented reality and modified schema-based instruction to teach problem solving to students with autism. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2022, 43, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-P.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-L. Requesting help module interface design on key partial video with action and augmented reality for children with autism spectrum disorder. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, R.D.; Leonardi, S.; Portaro, S.; Cause, M.L.; Domenico, C.D.; Colucci, P.V.; Pranio, F.; Bramanti, P.; Calabrò, R.S. Innovative use of virtual reality in autism spectrum disorder: A case-study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2021, 10, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.K.; Sarkar, N.; Swanson, A.; Weitlauf, A.; Warren, Z.; Sarkar, N. Cheerbrush: A novel interactive augmented reality coaching system for tooth-brushing skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. (TACCESS) 2021, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antão, J.Y.F.d.L.; Abreu, L.C.d.; Barbosa, R.T.d.A.; Crocetta, T.B.; Guarnieri, R.; Massetti, T.; Antunes, T.P.C.; Tonks, J.; Monteiro, C.B.d.M. Use of augmented reality with a motion-controlled game utilizing alphabet letters and numbers to improve performance and reaction time skills for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020, 23, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaia, P.; Bravaccio, C.; Corrado, G.; Duraccio, L.; Moccaldi, N.; Rossi, S. Robotic autism rehabilitation by wearable brain-computer interface and augmented reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Bari, Italy, 1 June–1 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- López-Faican, L.; Jaen, J. Emofindar: Evaluation of a mobile multi-player augmented reality game for primary school children. Comput. Educ. 2020, 149, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung-Teck, W.; Hanafi, H.F.; Abdullah, N.; Noh, N.M.; Hamzah, M. A prototype of augmented reality animation (ara) ecourseware: An assistive technology to assist autism spectrum disorders (asd) students master in basic living skills. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. (IJITEE) 2019, 9, 3487–3492. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, N.T.; Abdus-Sabur, R.; Keshav, N.U.; Liu, R.; Salisbury, J.P.; Vahabzadeh, A. Case study of a digital augmented reality intervention for autism in school classrooms: Associated with improved social communication, cognition, and motivation via educator and parent assessment. Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, M.; Curzio, O.; Carboni, A.; Moroni, D.; Salvetti, O.; Melani, A. Augmented interaction systems for supporting autistic children. evolution of a multichannel expressive tool: The semi project feasibility study. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Shrivastava, A.; Achary, K.; Dey, A.; Sharma, O. Augmented reality-based procedural task training application for less privileged children and autistic individuals. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Virtual-Reality Continuum and its Applications in Industry, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 14–16 November 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.Y.; Xu, J.; Winoto, P. An augmented reality-based word-learning mobile application for children with autism to support learning anywhere and anytime: Object recognition based on deep learning. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 182–192. [Google Scholar]

- Vahabzadeh, A.; Keshav, N.U.; Salisbury, J.P.; Sahin, N.T. Improvement of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in school-aged children, adolescents, and young adults with autism via a digital smartglasses-based socioemotional coaching aid: Short-term, uncontrolled pilot study. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e9631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taryadi; Kurniawan, I. The improvement of autism spectrum disorders on children communication ability with pecs method multimedia augmented reality-based. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 947, 012009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, M.F.; Sari, P.P.; Arisandi, D.; Abdullah, D.; Napitupulu, D.; Setiawan, M.I.; Albra, W.; Asnawi; Andayani, U. Implementation of augmented reality to train focus on children with s pecial needs. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 978, 012109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Lee, I.-J.; Lin, L.-Y. Augmented reality-based video- modeling storybook of nonverbal facial cues for children with autism spectrum disorder to improve their perceptions and judgments of facial expressions and emotions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihak, D.F.; Moore, E.J.; Wright, R.E.; McMahon, D.D.; Gibbons, M.M.; Smith, C. Evaluating augmented reality to complete a chain task for elementary students with autism. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2016, 31, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.; Foutohi-Ghazvini, F. Play therapy in augmented reality children with autism. J. Mod. Rehabil. 2016, 10, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, D.D.; Cihak, D.F.; Wright, R.E.; Bell, S.M. Augmented reality for teaching science vocabulary to postsecondary education stu- dents with intellectual disabilities and autism. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2016, 48, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, L.; Tentori, M. Mobile augmented reality to support teachers of children with autism. In International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Ambient Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, L.; Nguyen, D.H.; Boyd, L.; Hirano, S.; Rangel, A.; Rosas, D.G.; Tentori, M.; Hayes, G. Mosoco: A mobile assistive tool to support children with autism practicing social skills in real-life situations. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 2589–2598. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. “CASP Checklists”, CASP–Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2022. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Oke, A.E.; Arowoiya, V.A. Critical barriers to augmented reality technology adoption in developing countries: A case study of Nigeria. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 20, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).